Uterine artery embolization

Uterine artery embolization is a procedure in which an interventional radiologist uses a catheter to deliver small particles that block the blood supply to the uterine body. The procedure is done for the treatment of uterine fibroids and adenomyosis.[1][2] This minimally invasive procedure is commonly used in the treatment of uterine fibroids and is also called uterine fibroid embolization.

| Uterine artery embolization | |

|---|---|

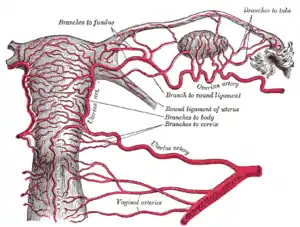

Arteries of the female reproductive tract (posterior view): uterine artery, ovarian artery and vaginal arteries. | |

| Specialty | Interventional radiology |

Medical uses

Uterine artery embolization is used to treat bothersome bulk-related symptoms or abnormal or heavy uterine bleeding due to uterine fibroids or for the treatment of adenomyosis. Fibroid size, number, and location are three potential predictors of a successful outcome.[3][4][5]

Long-term patient satisfaction outcomes are similar to that of surgery.[6] There is tentative evidence that traditional surgery may result in better fertility.[6] Uterine artery embolization also appears to require more repeat procedures than if surgery was done initially.[6]

It has shorter recovery times.[7] Uterine artery embolization is thought to work because uterine fibroids have abnormal vasculature together with aberrant responses to hypoxia (inadequate oxygenation to tissues).[8]

Uterine artery embolization can also be used to control heavy uterine bleeding for reasons other than fibroids, such as postpartum obstetrical hemorrhage.[9] and adenomyosis.

According to the American Journal of Gynecology, uterine artery embolization costs 12% less than hysterectomy and 8% less than myomectomy.[10]

Adverse effects

The rate of serious complications is comparable to that of myomectomy or hysterectomy. The advantage of somewhat faster recovery time is offset by a higher rate of minor complications and an increased likelihood of requiring surgical intervention within two to five years of the initial procedure.[7]

Complications include the following:

- Death from embolism, or sepsis (the presence of pus-forming or other pathogenic organisms, or their toxins, in the blood or tissues) resulting in multiple organ failure[11]

- Infection from tissue death of fibroids, leading to endometritis (infection of the uterus) resulting in lengthy hospitalization for administration of intravenous antibiotics[12]

- Misembolization from microspheres or polyvinyl alcohol particles flowing or drifting into organs or tissues where they were not intended to be, causing damage to other organs or other parts of the body[13] such as ovaries, bladder, rectum, and rarely small bowel, uterus, vagina, and labia.[14]

- Loss of ovarian function, infertility,[15] and loss of orgasm

- Failure – continued fibroid growth, regrowth within four months

- Menopause – iatrogenic, abnormal, cessation of menstruation and follicle stimulating hormones elevated to menopausal levels[16]

- Post-embolization syndrome – characterized by acute and/or chronic pain, fevers, malaise, nausea, vomiting and severe night sweats; foul vaginal odor coming from infected, necrotic tissue which remains inside the uterus; hysterectomy due to infection, pain or failure of embolization[17]

- Severe, persistent pain, resulting in the need for morphine or synthetic narcotics[18]

- Hematoma,[14] blood clot at the incision site; vaginal discharge containing pus and blood, bleeding from incision site, bleeding from vagina, fibroid expulsion (fibroids pushing out through the vagina), unsuccessful fibroid expulsion (fibroids trapped in the cervix causing infection and requiring surgical removal), life-threatening allergic reaction to the contrast material,[14] and uterine adhesions

Procedure

The procedure is performed by an interventional radiologist under conscious sedation.[14] Access is commonly through the radial or femoral artery via the wrist or groin,[14] respectively. After anesthetizing the skin over the artery of choice, the artery is accessed by a needle puncture using Seldinger technique.[14] An access sheath and guidewire are then introduced into the artery. In order to select the uterine vessels for subsequent embolization, a guiding catheter is commonly used and placed into the uterine artery under X-ray fluoroscopy guidance. Once at the level of the uterine artery an angiogram with contrast is performed to confirm placement of the catheter and the embolizing agent (spheres or beads) is released. Blood flow to the fibroid will slow significantly or cease altogether, causing the fibroid to shrink. This process can be repeated for as many arteries as are supplying the fibroid. This is done bilaterally from the initial puncture site as unilateral uterine artery embolizations have a high risk of failure. With both uterine arteries occluded, abundant collateral circulation prevents uterine necrosis, and the fibroids decrease in size and vascularity as they receive the bulk of the embolization material. The procedure can be performed in a hospital, surgical center or office setting and commonly take no longer than an hour to perform. Post-procedurally if access was gained via a femoral artery puncture an occlusion device can be used to hasten healing of the puncture site and the patient is asked to remain with the leg extended for several hours but many patients are discharged the same day with some remaining in the hospital for a single day admission for pain control and observation. If access was gained via the radial artery the patient will be able to get off the table and walk out immediately following the procedure. The procedure is not a surgical intervention, and allows the uterus to be kept in place, avoiding many of the associated surgical complications.

References

- Siskin GP, Tublin ME, Stainken BF, et al. (2001). "Uterine artery embolization for the treatment of adenomyosis: clinical response and evaluation with MR imaging". American Journal of Roentgenology. 177 (2): 297–302. doi:10.2214/ajr.177.2.1770297. PMID 11461849.

- Chen C, Liu P, Lu J, et al. [Uterine arterial embolization in the treatment of adenomyosis]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 2002; 37:77.

- Spies JB, Roth AR, Jha RC, et al. (2002). "Leiomyomata treated with uterine artery embolization: factors associated with successful symptom and imaging outcome". Radiology. 222 (1): 45–52. doi:10.1148/radiol.2221010661. PMID 11756703.

- Pelage JP, Walker WJ, Le Dref O, et al. (2001). "Treatment of uterine fibroids". Lancet. 357 (9267): 1530. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04683-3. PMC 5267678. PMID 11383541.

- Katsumori T, Nakajima K, Mihara T (2003). "Is a large fibroid a high-risk factor for uterine artery embolization?". American Journal of Roentgenology. 181 (5): 1309–1314. doi:10.2214/ajr.181.5.1811309. PMID 14573425.

- Gupta, JK; Sinha, A; Lumsden, MA; Hickey, M (26 December 2014). "Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD005073. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005073.pub4. PMID 25541260.

- Gupta, Janesh K.; Sinha, Anju; Lumsden, M. A.; Hickey, Martha (2014-12-26). "Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD005073. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005073.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 25541260.

- Tal, R.; Segars, J. H. (2013). "The role of angiogenic factors in fibroid pathogenesis: potential implications for future therapy". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (2): 194–216. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt042. ISSN 1355-4786. PMC 3922145. PMID 24077979.

- Management of severe postpartum haemorrhage by uterine artery embolization

- Al-Fozan, Haya; Dufort, Joanne; Kaplow, Marilyn; Valenti, David; Tulandi, Togas (November 2002). "Cost analysis of myomectomy, hysterectomy, and uterine artery embolization". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 187 (5): 1401–1404. doi:10.1067/mob.2002.127374. PMID 12439538.

- Vashisht A, Studd JW, Carey AH (2000). "Fibroid Embolisation: A Technique Not Without Significant Complications". British Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 107 (9): 1166–1170. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11119.x. PMID 11002964. S2CID 12959753.

- de Block S, de Bries C, Prinssen HM (2003). "Fatal Sepss after Uterine Artery Embolization with Microspheres". Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 14 (6): 779–783. doi:10.1097/01.rvi.0000079988.80153.61. PMID 12817046.

- Dietz DM, Stahfeld KR, Bansal SK (2004). "Buttock Necrosis After Uterine Artery Embolization". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 104 (Supplement): 1159–1161. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000141567.25541.26. PMID 15516436. S2CID 39409507.

- Rand, Thomas; Patel, Rafiuddin; Magerle, Wolfgang; Uberoi, Raman (December 2020). "CIRSE standards of practice on gynaecological and obstetric haemorrhage". CVIR Endovascular. 3 (1): 85. doi:10.1186/s42155-020-00174-7. ISSN 2520-8934. PMC 7695782. PMID 33245432.

- Robson S, Wilson K, David M (1999). "Pelvic Sepsis Complicating Embolization of a Uterine Fibroid". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 39 (4): 516–517. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.1999.tb03150.x. PMID 10687781. S2CID 19991414.

- Walker WJ, Pelage JP, Sutton C (2002). "Fibroid Embolization". Clinical Radiology. 57 (5): 325–331. doi:10.1053/crad.2002.0945. PMID 12014926.

- Common AA, Mocarski E, Kolin A (2001). "Leiomyosarcoma". Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 12 (12): 1449–1452. doi:10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61708-4. PMID 11742024.

- Soulen MC, Fairman RM, Baum R (2000). "Embolization of the Internal Iliac Artery: Still More to Learn". Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 11 (5): 543–545. doi:10.1016/S1051-0443(07)61604-2. PMID 10834483.