Gujarati script

The Gujarati script (ગુજરાતી લિપિ, transliterated: Gujǎrātī Lipi) is an abugida for the Gujarati language, Kutchi language, and various other languages. It is a variant of the Devanagari script differentiated by the loss of the characteristic horizontal line running above the letters and by a number of modifications to some characters.[3]

| Gujarati ગુજરાતી લિપિ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | c. 1592–present |

| Direction | left-to-right |

| Languages | Gujarati, Kutchi, Bhili, Dungra Bhil, Gamit, Kukna, Rajput Garasia, Vaghri, Varli, Vasavi, Avestan (Indian Zoroastrians)[1] |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Proto-Sinaitic alphabet[a] |

Sister systems | Devanagari[3] Modi Kaithi Nandinagari |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Gujr (320), Gujarati |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Gujarati |

Unicode range | U+0A80–U+0AFF |

[a] The Semitic origin of the Brahmic scripts is not universally agreed upon. | |

|

| Officially used writing systems in India |

|---|

| Category |

| Brahmi-derived scripts |

| Arabic-derived scripts |

| Alphabets |

|

| Related |

|

Official script Writing systems of India Languages of India |

|

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmic script and its descendants |

Gujarati numerical digits are also different from their Devanagari counterparts.

Origin

The Gujarati script (ગુજરાતી લિપિ) was adapted from the Nagari script to write the Gujarati language. The Gujarati language and script developed in three distinct phases — 10th to 15th century, 15th to 17th century and 17th to 19th century. The first phase is marked by use of Prakrit, Apabramsa and its variants such as Paisaci, Shauraseni, Magadhi and Maharashtri. In second phase, Old Gujarati script was in wide use. The earliest known document in the Old Gujarati script is a handwritten manuscript Adi Parva dating from 1591–92, and the script first appeared in print in a 1797 advertisement. The third phase is the use of script developed for ease and fast writing. The use of shirorekhā (the topline as in Devanagari) was abandoned. Until the 19th century it was used mainly for writing letters and keeping accounts, while the Devanagari script was used for literature and academic writings. It is also known as the śarāphī (banker's), vāṇiāśāī (merchant's) or mahājanī (trader's) script. This script became the basis of the modern script. Later the same script was adopted by writers of manuscripts. Jain community also promoted its use for copying religious texts by hired writers.[3][4]

Overview

The Gujarati writing system is an abugida, in which each base consonantal character possesses an inherent vowel, that vowel being a [ə]. For postconsonantal vowels other than a, the consonant is applied with diacritics, while for non-postconsonantal vowels (initial and post-vocalic positions), there are full-formed characters. With a being the most frequent vowel,[5] this is a convenient system in the sense that it cuts down on the width of writing.

Following out of the aforementioned property, consonants lacking a proceeding vowel may condense into the proceeding consonant, forming compound or conjunct letters. The formation of these conjuncts follows a system of rules depending on the consonants involved.

In accordance with all the other Indic scripts, Gujarati is written from left to right, and is not case-sensitive.

The Gujarati script is basically phonemic, with a few exceptions.[6] First out of these is the written representation of non-pronounced as, which are of three types.

- Word-final as. Thus ઘર "house" is pronounced ghar and not ghara. The as remain unpronounced before postpositions and before other words in compounds: ઘરપર "in the house" is gharpar and not gharapar; ઘરકામ "housework" is gharkām and not gharakām. This non-pronunciation is not always the case with conjunct characters: મિત્ર "friend" is truly mitra.

- Naturally elided as through the combination of morphemes. The root પકડ઼ pakaṛ "hold" when inflected as પકડ઼ે "holds" remains written as pakaṛe even though pronounced as pakṛe. See Gujarati phonology#ə-deletion.

- as whose non-pronunciation follows the above rule, but which are in single words not resultant of any actual combination. Thus વરસાદ "rain", written as varasād but pronounced as varsād.

Secondly and most importantly, being of Sanskrit-based Devanagari, Gujarati's script retains notations for the obsolete (short i, u vs. long ī, ū; r̥, ru; ś, ṣ), and lacks notations for innovations (/e/ vs. /ɛ/; /o/ vs. /ɔ/; clear vs. murmured vowels).[7]

Contemporary Gujarati uses English punctuation, such as the question mark, exclamation mark, comma, and full stop. Apostrophes are used for the rarely written clitic. Quotation marks are not as often used for direct quotes. The full stop replaced the traditional vertical bar, and the colon, mostly obsolete in its Sanskritic capacity (see below), follows the European usage.

Use for Avestan

The Zoroastrians of India, who represent one of the largest surviving Zoroastrian communities worldwide, would transcribe Avestan in Nagri script-based scripts as well as the Avestan alphabet. This is a relatively recent development first seen in the ca. 12th century texts of Neryosang Dhaval and other Parsi Sanskritist theologians of that era, and which are roughly contemporary with the oldest surviving manuscripts in Avestan script. Today, Avestan is most commonly typeset in Gujarati script (Gujarati being the traditional language of the Indian Zoroastrians). Some Avestan letters with no corresponding symbol are synthesized with additional diacritical marks, for example, the /z/ in zaraθuštra is written with /j/ + dot below.

Influence in Southeast Asia

Miller (2010) presented a theory that the indigenous scripts of Sumatra (Indonesia), Sulawesi (Indonesia) and the Philippines are descended from an early form of the Gujarati script. Historical records show that Gujaratis played a major role in the archipelago, where they were manufacturers and played a key role in introducing Islam. Tomé Pires reported a presence of a thousand Gujaratis in Malacca (Malaysia) prior to 1512.[8]

Gujarati letters, diacritics, and digits

Vowels

Vowels (svara), in their conventional order, are historically grouped into "short" (hrasva) and "long" (dīrgha) classes, based on the "light" (laghu) and "heavy" (guru) syllables they create in traditional verse. The historical long vowels ī and ū are no longer distinctively long in pronunciation. Only in verse do syllables containing them assume the values required by meter.[9]

Finally, a practice of using inverted mātras to represent English [æ] and [ɔ]'s has gained ground.[6]

| Independent | Diacritic | Diacritic with ભ | Rom. | IPA | Name of diacritic[10] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| અ | ભ | a | ə | ||

| આ | ા | ભા | ā | ɑ̈ | kāno |

| ઇ | િ | ભિ | i | i | hrasva-ajju |

| ઈ | ી | ભી | ī | dīrgha-ajju | |

| ઉ | ુ | ભુ | u | u | hrasva-varaṛũ |

| ઊ | ૂ | ભૂ | ū | dīrgha-varaṛũ | |

| એ | ે | ભે | e, ɛ | ek mātra | |

| ઐ | ૈ | ભૈ | ai | əj | be mātra |

| ઓ | ો | ભો | o, ɔ | kāno ek mātra | |

| ઔ | ૌ | ભૌ | au | əʋ | kāno be mātra |

| અં | ં | ભં | ṁ | ä | anusvār |

| અ: | ઃ | ભઃ | ḥ | ɨ | visarga |

| ઋ | ૃ | ભૃ | r̥ | ɾu | |

| ઍ | ૅ | ભૅ | â | æ | |

| ઑ | ૉ | ભૉ | ô | ɔ | |

ર r, જ j and હ h form the irregular forms of રૂ rū, જી jī and હૃ hṛ.

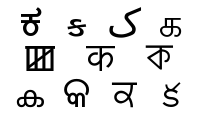

Consonants

Consonants (vyañjana) are grouped in accordance with the traditional, linguistically based Sanskrit scheme of arrangement, which considers the usage and position of the tongue during their pronunciation. In sequence, these categories are: velar, palatal, retroflex, dental, labial, sonorant and fricative. Among the first five groups, which contain the stops, the ordering starts with the unaspirated voiceless, then goes on through aspirated voiceless, unaspirated voiced, and aspirated voiced, ending with the Nasal stops. Most have a Devanagari counterpart.[11]

| Plosive | Nasal | Sonorant | Sibilant | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voiceless | Voiced | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Unaspirated | Aspirated | Unaspirated | Aspirated | ||||||||||||||||||

| Velar | ક | ka | kə | ખ | kha | kʰə | ગ | ga | ɡə | ઘ | gha | ɡʱə | ઙ | ṅa | ŋə | ||||||

| Palatal | ચ | cha | tʃə | છ | chha | tʃʰə | જ | ja | dʒə | ઝ | jha | dʒʱə | ઞ | ña | ɲə | ય | ya | jə | શ | śa | ʃə |

| Retroflex | ટ | Ta | ʈə | ઠ | Tha | ʈʰə | ડ | Da | ɖə | ઢ | Dha | ɖʱə | ણ | ṇa(hna) | ɳə | ર | ra | ɾə | ષ | ṣa | ʂə |

| Dental | ત | ta | t̪ə | થ | tha | t̪ʰə | દ | da | d̪ə | ધ | dha | d̪ʱə | ન | na | nə | લ | la | lə | સ | sa | sə |

| Labial | પ | pa | pə | ફ | pha | pʰə | બ | ba | bə | ભ | bha | bʱə | મ | ma | mə | વ | va | ʋə | |||

| Guttural | હ | ha | ɦə |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retroflex | ળ | ḷa | ɭə |

| ક્ષ | kṣa | kʂə | |

| જ્ઞ | gña | ɡnə |

- Letters can take names by suffixing કાર kār. The letter ર ra is an exception; it is called રેફ reph.[12]

- Starting with ક ka and ending with જ્ઞ jña, the order goes:[13]

- Plosives & Nasals (left to right, top to bottom) → Sonorants & Sibilants (top to bottom, left to right) → Bottom box (top to bottom)

- The final two are compound characters that happen to be traditionally included in the set. They are indiscriminate as to their original constituents, and they are the same size as a single consonant character.

- Written (V)hV sets in speech result in murmured V̤(C) sets (see Gujarati phonology#Murmur). Thus (with ǐ = i or ī, and ǔ = u or ū): ha → [ə̤] from /ɦə/; hā → [a̤] from /ɦa/; ahe → [ɛ̤] from /əɦe/; aho → [ɔ̤] from /əɦo/; ahā → [a̤] from /əɦa/; ahǐ → [ə̤j] from /əɦi/; ahǔ → [ə̤ʋ] from /əɦu/; āhǐ → [a̤j] from /ɑɦi/; āhǔ → [a̤ʋ] from /ɑɦu/; etc.

Non-vowel diacritics

| Diacritic | Name | Function |

|---|---|---|

| ં | anusvāra | Represents vowel nasality or the nasal stop homorganic with the following stop.[13] |

| ઃ | visarga | A silent, rarely used Sanskrit holdover originally representing [h]. Romanized as ḥ. |

| ્ | virāma | Strikes out a consonant's inherent a.[14] |

Digits

| Arabic numeral |

Gujarati numeral |

Name |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | ૦ | mīṇḍu or shunya |

| 1 | ૧ | ekado or ek |

| 2 | ૨ | bagado or bay |

| 3 | ૩ | tragado or tran |

| 4 | ૪ | chogado or chaar |

| 5 | ૫ | pāchado or paanch |

| 6 | ૬ | chagado or chah |

| 7 | ૭ | sātado or sāt |

| 8 | ૮ | āṭhado or āanth |

| 9 | ૯ | navado or nav |

Conjuncts

As mentioned, successive consonants lacking a vowel in between them may physically join together as a 'conjunct'. The government of these clusters ranges from widely to narrowly applicable rules, with special exceptions within. While standardized for the most part, there are certain variations in clustering, of which the Unicode used on this page is just one scheme. The rules:[6]

- 23 out of the 36 consonants contain a vertical right stroke (ખ, ધ, ળ etc.). As first or middle fragments/members of a cluster, they lose that stroke. e.g. ત + વ = ત્વ, ણ + ઢ = ણ્ઢ, થ + થ = થ્થ.

- શ ś(a) appears as a different, simple ribbon-shaped fragment preceding વ va, ન na, ચ ca and ર ra. Thus શ્વ śva, શ્ન śna, શ્ચ śca and શ્ર śra. In the first three cases the second member appears to be squished down to accommodate શ's ribbon fragment. In શ્ચ śca we see ચ's Devanagari equivalent of च as the squished-down second member. See the note on ર to understand the formation of શ્ર śra.

- ર r(a)

- as a first member it takes the form of a curved upward dash above the final character or its kāno. e.g. ર્ભ rbha, ર્ભા rbhā, ર્ગ્મ rgma, ર્ગ્મા rgmā.

- as a final member

- with છ chha, ટ Ta, ઠ Tha, ડ Da, ઢ Dha and દ da, it is two lines below the character, pointed downwards and apart. Thus છ્ર, ટ્ર, ઠ્ર, ડ્ર, ઢ્ર and દ્ર.

- elsewhere it is a diagonal stroke jutting leftwards and down. e.g. ક્ર, ગ્ર, ભ્ર. ત ta is shifted up to make ત્ર tra. And as said before, શ ś(a) is modified to શ્ર śra.

- Vertical combination of geminates ṭṭa, ṭhṭha, ḍḍa and ḍhḍha: ટ્ટ, ઠ્ઠ, ડ્ડ, ઢ્ઢ. Also, ટ્ઠ ṭṭha and ડ્ઢ ḍḍha.

- As first shown with શ્ચ śca, while Gujarati is a separate script with its own novel characters, for compounds it will often use the Devanagari versions.

- દ d(a) as द preceding ગ ga, ઘ gha, ધ dha, બ ba (as ब), ભ bha, વ va, મ ma and ર ra. The first six-second members are shrunken and hang at an angle off the bottom left corner of the preceding દ/द. Thus દ્ગ dga, દ્ઘ dgha, દ્ધ ddha, દ્બ dba, દ્ભ dbha, દ્વ dva, દ્મ dma and દ્ર dra.

- હ h(a) as ह preceding ન na, મ ma, ય ya, ર ra, વ va and ઋ ṛ. Thus હ્ન hna, હ્મ hma, હ્ય hya, હ્ર hra, હ્વ hva and હૃ hṛ.

- when ઙ ṅa and ઞ ña are first members we get second members of ક ka as क, ચ ca as च and જ ja as ज. ઙ forms compounds through vertical combination. ઞ's strokeless fragment connects to the stroke of the second member, jutting upwards while pushing the second member down. Thus ઙ્ક ṅka, ઙ્ગ ṅga, ઙ્ઘ ṅgha, ઙ્ક્ષ ṅkṣa, ઞ્ચ ñca and ઞ્જ ñja.

- The remaining vertical stroke-less characters join by squeezing close together. e.g. ક્ય kya, જ્જ jja.

- Outstanding special forms: ન્ન nna, ત્ત tta, દ્દ dda and દ્ય dya.

The role and nature of Sanskrit must be taken into consideration to understand the occurrence of consonant clusters. The orthography of written Sanskrit was completely phonetic, and had a tradition of not separating words by spaces. Morphologically it was highly synthetic, and it had a great capacity to form large compound words. Thus clustering was highly frequent, and it is Sanskrit loanwords to the Gujarati language that are the grounds of most clusters. Gujarati, on the other hand, is more analytic, has phonetically smaller, simpler words, and has a script whose orthography is slightly imperfect (a-elision) and separates words by spaces. Thus evolved Gujarati words are less a cause for clusters. The same can be said of Gujarati's other longstanding source of words, Persian, which also provides phonetically smaller and simpler words.

An example attesting to this general theme is that of the series of d- clusters. These are essentially Sanskrit clusters, using the original Devanagari forms. There are no cluster forms for formations such as dta, dka, etc. because such formations weren't permitted in Sanskrit phonology anyway. They are permitted under Gujarati phonology, but are written unclustered (પદત padata "position", કૂદકો kūdko "leap"), with patterns such as a-elision at work instead.

| ક | ખ | ગ | ઘ | ઙ | ચ | છ | જ | ઝ | ઞ | ટ | ઠ | ડ | ઢ | ણ | ત | થ | દ | ધ | ન | પ | ફ | બ | ભ | મ | ય | ર | લ | ળ | વ | શ | ષ | સ | હ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ક | ક્ક | ક્ખ | ક્ગ | ક્ઘ | ક્ઙ | ક્ચ | ક્છ | ક્જ | ક્ઝ | ક્ઞ | ક્ટ | ક્ઠ | ક્ડ | ક્ઢ | ક્ણ | ક્ત | ક્થ | ક્દ | ક્ધ | ક્ન | ક્પ | ક્ફ | ક્બ | ક્ભ | ક્મ | ક્ય | ક્ર | ક્લ | ક્ળ | ક્વ | ક્શ | ક્ષ | ક્સ | ક્હ |

| ખ | ખ્ક | ખ્ખ | ખ્ગ | ખ્ઘ | ખ્ઙ | ખ્ચ | ખ્છ | ખ્જ | ખ્ઝ | ખ્ઞ | ખ્ટ | ખ્ઠ | ખ્ડ | ખ્ઢ | ખ્ણ | ખ્ત | ખ્થ | ખ્દ | ખ્ધ | ખ્ન | ખ્પ | ખ્ફ | ખ્બ | ખ્ભ | ખ્મ | ખ્ય | ખ્ર | ખ્લ | ખ્ળ | ખ્વ | ખ્શ | ખ્ષ | ખ્સ | ખ્હ |

| ગ | ગ્ક | ગ્ખ | ગ્ગ | ગ્ઘ | ગ્ઙ | ગ્ચ | ગ્છ | ગ્જ | ગ્ઝ | ગ્ઞ | ગ્ટ | ગ્ઠ | ગ્ડ | ગ્ઢ | ગ્ણ | ગ્ત | ગ્થ | ગ્દ | ગ્ધ | ગ્ન | ગ્પ | ગ્ફ | ગ્બ | ગ્ભ | ગ્મ | ગ્ય | ગ્ર | ગ્લ | ગ્ળ | ગ્વ | ગ્શ | ગ્ષ | ગ્સ | ગ્હ |

| ઘ | ઘ્ક | ઘ્ખ | ઘ્ગ | ઘ્ઘ | ઘ્ઙ | ઘ્ચ | ઘ્છ | ઘ્જ | ઘ્ઝ | ઘ્ઞ | ઘ્ટ | ઘ્ઠ | ઘ્ડ | ઘ્ઢ | ઘ્ણ | ઘ્ત | ઘ્થ | ઘ્દ | ઘ્ધ | ઘ્ન | ઘ્પ | ઘ્ફ | ઘ્બ | ઘ્ભ | ઘ્મ | ઘ્ય | ઘ્ર | ઘ્લ | ઘ્ળ | ઘ્વ | ઘ્શ | ઘ્ષ | ઘ્સ | ઘ્હ |

| ઙ | ઙ્ક | ઙ્ખ | ઙ્ગ | ઙ્ઘ | ઙ્ઙ | ઙ્ચ | ઙ્છ | ઙ્જ | ઙ્ઝ | ઙ્ઞ | ઙ્ટ | ઙ્ઠ | ઙ્ડ | ઙ્ઢ | ઙ્ણ | ઙ્ત | ઙ્થ | ઙ્દ | ઙ્ધ | ઙ્ન | ઙ્પ | ઙ્ફ | ઙ્બ | ઙ્ભ | ઙ્મ | ઙ્ય | ઙ્ર | ઙ્લ | ઙ્ળ | ઙ્વ | ઙ્શ | ઙ્ષ | ઙ્સ | ઙ્હ |

| ચ | ચ્ક | ચ્ખ | ચ્ગ | ચ્ઘ | ચ્ઙ | ચ્ચ | ચ્છ | ચ્જ | ચ્ઝ | ચ્ઞ | ચ્ટ | ચ્ઠ | ચ્ડ | ચ્ઢ | ચ્ણ | ચ્ત | ચ્થ | ચ્દ | ચ્ધ | ચ્ન | ચ્પ | ચ્ફ | ચ્બ | ચ્ભ | ચ્મ | ચ્ય | ચ્ર | ચ્લ | ચ્ળ | ચ્વ | ચ્શ | ચ્ષ | ચ્સ | ચ્હ |

| છ | છ્ક | છ્ખ | છ્ગ | છ્ઘ | છ્ઙ | છ્ચ | છ્છ | છ્જ | છ્ઝ | છ્ઞ | છ્ટ | છ્ઠ | છ્ડ | છ્ઢ | છ્ણ | છ્ત | છ્થ | છ્દ | છ્ધ | છ્ન | છ્પ | છ્ફ | છ્બ | છ્ભ | છ્મ | છ્ય | છ્ર | છ્લ | છ્ળ | છ્વ | છ્શ | છ્ષ | છ્સ | છ્હ |

| જ | જ્ક | જ્ખ | જ્ગ | જ્ઘ | જ્ઙ | જ્ચ | જ્છ | જ્જ | જ્ઝ | જ્ઞ | જ્ટ | જ્ઠ | જ્ડ | જ્ઢ | જ્ણ | જ્ત | જ્થ | જ્દ | જ્ધ | જ્ન | જ્પ | જ્ફ | જ્બ | જ્ભ | જ્મ | જ્ય | જ્ર | જ્લ | જ્ળ | જ્વ | જ્શ | જ્ષ | જ્સ | જ્હ |

| ઝ | ઝ્ક | ઝ્ખ | ઝ્ગ | ઝ્ઘ | ઝ્ઙ | ઝ્ચ | ઝ્છ | ઝ્જ | ઝ્ઝ | ઝ્ઞ | ઝ્ટ | ઝ્ઠ | ઝ્ડ | ઝ્ઢ | ઝ્ણ | ઝ્ત | ઝ્થ | ઝ્દ | ઝ્ધ | ઝ્ન | ઝ્પ | ઝ્ફ | ઝ્બ | ઝ્ભ | ઝ્મ | ઝ્ય | ઝ્ર | ઝ્લ | ઝ્ળ | ઝ્વ | ઝ્શ | ઝ્ષ | ઝ્સ | ઝ્હ |

| ઞ | ઞ્ક | ઞ્ખ | ઞ્ગ | ઞ્ઘ | ઞ્ઙ | ઞ્ચ | ઞ્છ | ઞ્જ | ઞ્ઝ | ઞ્ઞ | ઞ્ટ | ઞ્ઠ | ઞ્ડ | ઞ્ઢ | ઞ્ણ | ઞ્ત | ઞ્થ | ઞ્દ | ઞ્ધ | ઞ્ન | ઞ્પ | ઞ્ફ | ઞ્બ | ઞ્ભ | ઞ્મ | ઞ્ય | ઞ્ર | ઞ્લ | ઞ્ળ | ઞ્વ | ઞ્શ | ઞ્ષ | ઞ્સ | ઞ્હ |

| ટ | ટ્ક | ટ્ખ | ટ્ગ | ટ્ઘ | ટ્ઙ | ટ્ચ | ટ્છ | ટ્જ | ટ્ઝ | ટ્ઞ | ટ્ટ | ટ્ઠ | ટ્ડ | ટ્ઢ | ટ્ણ | ટ્ત | ટ્થ | ટ્દ | ટ્ધ | ટ્ન | ટ્પ | ટ્ફ | ટ્બ | ટ્ભ | ટ્મ | ટ્ય | ટ્ર | ટ્લ | ટ્ળ | ટ્વ | ટ્શ | ટ્ષ | ટ્સ | ટ્હ |

| ઠ | ઠ્ક | ઠ્ખ | ઠ્ગ | ઠ્ઘ | ઠ્ઙ | ઠ્ચ | ઠ્છ | ઠ્જ | ઠ્ઝ | ઠ્ઞ | ઠ્ટ | ઠ્ઠ | ઠ્ડ | ઠ્ઢ | ઠ્ણ | ઠ્ત | ઠ્થ | ઠ્દ | ઠ્ધ | ઠ્ન | ઠ્પ | ઠ્ફ | ઠ્બ | ઠ્ભ | ઠ્મ | ઠ્ય | ઠ્ર | ઠ્લ | ઠ્ળ | ઠ્વ | ઠ્શ | ઠ્ષ | ઠ્સ | ઠ્હ |

| ડ | ડ્ક | ડ્ખ | ડ્ગ | ડ્ઘ | ડ્ઙ | ડ્ચ | ડ્છ | ડ્જ | ડ્ઝ | ડ્ઞ | ડ્ટ | ડ્ઠ | ડ્ડ | ડ્ઢ | ડ્ણ | ડ્ત | ડ્થ | ડ્દ | ડ્ધ | ડ્ન | ડ્પ | ડ્ફ | ડ્બ | ડ્ભ | ડ્મ | ડ્ય | ડ્ર | ડ્લ | ડ્ળ | ડ્વ | ડ્શ | ડ્ષ | ડ્સ | ડ્હ |

| ઢ | ઢ્ક | ઢ્ખ | ઢ્ગ | ઢ્ઘ | ઢ્ઙ | ઢ્ચ | ઢ્છ | ઢ્જ | ઢ્ઝ | ઢ્ઞ | ઢ્ટ | ઢ્ઠ | ઢ્ડ | ઢ્ઢ | ઢ્ણ | ઢ્ત | ઢ્થ | ઢ્દ | ઢ્ધ | ઢ્ન | ઢ્પ | ઢ્ફ | ઢ્બ | ઢ્ભ | ઢ્મ | ઢ્ય | ઢ્ર | ઢ્લ | ઢ્ળ | ઢ્વ | ઢ્શ | ઢ્ષ | ઢ્સ | ઢ્હ |

| ણ | ણ્ક | ણ્ખ | ણ્ગ | ણ્ઘ | ણ્ઙ | ણ્ચ | ણ્છ | ણ્જ | ણ્ઝ | ણ્ઞ | ણ્ટ | ણ્ઠ | ણ્ડ | ણ્ઢ | ણ્ણ | ણ્ત | ણ્થ | ણ્દ | ણ્ધ | ણ્ન | ણ્પ | ણ્ફ | ણ્બ | ણ્ભ | ણ્મ | ણ્ય | ણ્ર | ણ્લ | ણ્ળ | ણ્વ | ણ્શ | ણ્ષ | ણ્સ | ણ્હ |

| ત | ત્ક | ત્ખ | ત્ગ | ત્ઘ | ત્ઙ | ત્ચ | ત્છ | ત્જ | ત્ઝ | ત્ઞ | ત્ટ | ત્ઠ | ત્ડ | ત્ઢ | ત્ણ | ત્ત | ત્થ | ત્દ | ત્ધ | ત્ન | ત્પ | ત્ફ | ત્બ | ત્ભ | ત્મ | ત્ય | ત્ર | ત્લ | ત્ળ | ત્વ | ત્શ | ત્ષ | ત્સ | ત્હ |

| થ | થ્ક | થ્ખ | થ્ગ | થ્ઘ | થ્ઙ | થ્ચ | થ્છ | થ્જ | થ્ઝ | થ્ઞ | થ્ટ | થ્ઠ | થ્ડ | થ્ઢ | થ્ણ | થ્ત | થ્થ | થ્દ | થ્ધ | થ્ન | થ્પ | થ્ફ | થ્બ | થ્ભ | થ્મ | થ્ય | થ્ર | થ્લ | થ્ળ | થ્વ | થ્શ | થ્ષ | થ્સ | થ્હ |

| દ | દ્ક | દ્ખ | દ્ગ | દ્ઘ | દ્ઙ | દ્ચ | દ્છ | દ્જ | દ્ઝ | દ્ઞ | દ્ટ | દ્ઠ | દ્ડ | દ્ઢ | દ્ણ | દ્ત | દ્થ | દ્દ | દ્ધ | દ્ન | દ્પ | દ્ફ | દ્બ | દ્ભ | દ્મ | દ્ય | દ્ર | દ્લ | દ્ળ | દ્વ | દ્શ | દ્ષ | દ્સ | દ્હ |

| ધ | ધ્ક | ધ્ખ | ધ્ગ | ધ્ઘ | ધ્ઙ | ધ્ચ | ધ્છ | ધ્જ | ધ્ઝ | ધ્ઞ | ધ્ટ | ધ્ઠ | ધ્ડ | ધ્ઢ | ધ્ણ | ધ્ત | ધ્થ | ધ્દ | ધ્ધ | ધ્ન | ધ્પ | ધ્ફ | ધ્બ | ધ્ભ | ધ્મ | ધ્ય | ધ્ર | ધ્લ | ધ્ળ | ધ્વ | ધ્શ | ધ્ષ | ધ્સ | ધ્હ |

| ન | ન્ક | ન્ખ | ન્ગ | ન્ઘ | ન્ઙ | ન્ચ | ન્છ | ન્જ | ન્ઝ | ન્ઞ | ન્ટ | ન્ઠ | ન્ડ | ન્ઢ | ન્ણ | ન્ત | ન્થ | ન્દ | ન્ધ | ન્ન | ન્પ | ન્ફ | ન્બ | ન્ભ | ન્મ | ન્ય | ન્ર | ન્લ | ન્ળ | ન્વ | ન્શ | ન્ષ | ન્સ | ન્હ |

| પ | પ્ક | પ્ખ | પ્ગ | પ્ઘ | પ્ઙ | પ્ચ | પ્છ | પ્જ | પ્ઝ | પ્ઞ | પ્ટ | પ્ઠ | પ્ડ | પ્ઢ | પ્ણ | પ્ત | પ્થ | પ્દ | પ્ધ | પ્ન | પ્પ | પ્ફ | પ્બ | પ્ભ | પ્મ | પ્ય | પ્ર | પ્લ | પ્ળ | પ્વ | પ્શ | પ્ષ | પ્સ | પ્હ |

| ફ | ફ્ક | ફ્ખ | ફ્ગ | ફ્ઘ | ફ્ઙ | ફ્ચ | ફ્છ | ફ્જ | ફ્ઝ | ફ્ઞ | ફ્ટ | ફ્ઠ | ફ્ડ | ફ્ઢ | ફ્ણ | ફ્ત | ફ્થ | ફ્દ | ફ્ધ | ફ્ન | ફ્પ | ફ્ફ | ફ્બ | ફ્ભ | ફ્મ | ફ્ય | ફ્ર | ફ્લ | ફ્ળ | ફ્વ | ફ્શ | ફ્ષ | ફ્સ | ફ્હ |

| બ | બ્ક | બ્ખ | બ્ગ | બ્ઘ | બ્ઙ | બ્ચ | બ્છ | બ્જ | બ્ઝ | બ્ઞ | બ્ટ | બ્ઠ | બ્ડ | બ્ઢ | બ્ણ | બ્ત | બ્થ | બ્દ | બ્ધ | બ્ન | બ્પ | બ્ફ | બ્બ | બ્ભ | બ્મ | બ્ય | બ્ર | બ્લ | બ્ળ | બ્વ | બ્શ | બ્ષ | બ્સ | બ્હ |

| ભ | ભ્ક | ભ્ખ | ભ્ગ | ભ્ઘ | ભ્ઙ | ભ્ચ | ભ્છ | ભ્જ | ભ્ઝ | ભ્ઞ | ભ્ટ | ભ્ઠ | ભ્ડ | ભ્ઢ | ભ્ણ | ભ્ત | ભ્થ | ભ્દ | ભ્ધ | ભ્ન | ભ્પ | ભ્ફ | ભ્બ | ભ્ભ | ભ્મ | ભ્ય | ભ્ર | ભ્લ | ભ્ળ | ભ્વ | ભ્શ | ભ્ષ | ભ્સ | ભ્હ |

| મ | મ્ક | મ્ખ | મ્ગ | મ્ઘ | મ્ઙ | મ્ચ | મ્છ | મ્જ | મ્ઝ | મ્ઞ | મ્ટ | મ્ઠ | મ્ડ | મ્ઢ | મ્ણ | મ્ત | મ્થ | મ્દ | મ્ધ | મ્ન | મ્પ | મ્ફ | મ્બ | મ્ભ | મ્મ | મ્ય | મ્ર | મ્લ | મ્ળ | મ્વ | મ્શ | મ્ષ | મ્સ | મ્હ |

| ય | ય્ક | ય્ખ | ય્ગ | ય્ઘ | ય્ઙ | ય્ચ | ય્છ | ય્જ | ય્ઝ | ય્ઞ | ય્ટ | ય્ઠ | ય્ડ | ય્ઢ | ય્ણ | ય્ત | ય્થ | ય્દ | ય્ધ | ય્ન | ય્પ | ય્ફ | ય્બ | ય્ભ | ય્મ | ય્ય | ય્ર | ય્લ | ય્ળ | ય્વ | ય્શ | ય્ષ | ય્સ | ય્હ |

| ર | ર્ક | ર્ખ | ર્ગ | ર્ઘ | ર્ઙ | ર્ચ | ર્છ | ર્જ | ર્ઝ | ર્ઞ | ર્ટ | ર્ઠ | ર્ડ | ર્ઢ | ર્ણ | ર્ત | ર્થ | ર્દ | ર્ધ | ર્ન | ર્પ | ર્ફ | ર્બ | ર્ભ | ર્મ | ર્ય | ર્ર | ર્લ | ર્ળ | ર્વ | ર્શ | ર્ષ | ર્સ | ર્હ |

| લ | લ્ક | લ્ખ | લ્ગ | લ્ઘ | લ્ઙ | લ્ચ | લ્છ | લ્જ | લ્ઝ | લ્ઞ | લ્ટ | લ્ઠ | લ્ડ | લ્ઢ | લ્ણ | લ્ત | લ્થ | લ્દ | લ્ધ | લ્ન | લ્પ | લ્ફ | લ્બ | લ્ભ | લ્મ | લ્ય | લ્ર | લ્લ | લ્ળ | લ્વ | લ્શ | લ્ષ | લ્સ | લ્હ |

| ળ | ળ્ક | ળ્ખ | ળ્ગ | ળ્ઘ | ળ્ઙ | ળ્ચ | ળ્છ | ળ્જ | ળ્ઝ | ળ્ઞ | ળ્ટ | ળ્ઠ | ળ્ડ | ળ્ઢ | ળ્ણ | ળ્ત | ળ્થ | ળ્દ | ળ્ધ | ળ્ન | ળ્પ | ળ્ફ | ળ્બ | ળ્ભ | ળ્મ | ળ્ય | ળ્ર | ળ્લ | ળ્ળ | ળ્વ | ળ્શ | ળ્ષ | ળ્સ | ળ્હ |

| વ | વ્ક | વ્ખ | વ્ગ | વ્ઘ | વ્ઙ | વ્ચ | વ્છ | વ્જ | વ્ઝ | વ્ઞ | વ્ટ | વ્ઠ | વ્ડ | વ્ઢ | વ્ણ | વ્ત | વ્થ | વ્દ | વ્ધ | વ્ન | વ્પ | વ્ફ | વ્બ | વ્ભ | વ્મ | વ્ય | વ્ર | વ્લ | વ્ળ | વ્વ | વ્શ | વ્ષ | વ્સ | વ્હ |

| શ | શ્ક | શ્ખ | શ્ગ | શ્ઘ | શ્ઙ | શ્ચ | શ્છ | શ્જ | શ્ઝ | શ્ઞ | શ્ટ | શ્ઠ | શ્ડ | શ્ઢ | શ્ણ | શ્ત | શ્થ | શ્દ | શ્ધ | શ્ન | શ્પ | શ્ફ | શ્બ | શ્ભ | શ્મ | શ્ય | શ્ર | શ્લ | શ્ળ | શ્વ | શ્શ | શ્ષ | શ્સ | શ્હ |

| ષ | ષ્ક | ષ્ખ | ષ્ગ | ષ્ઘ | ષ્ઙ | ષ્ચ | ષ્છ | ષ્જ | ષ્ઝ | ષ્ઞ | ષ્ટ | ષ્ઠ | ષ્ડ | ષ્ઢ | ષ્ણ | ષ્ત | ષ્થ | ષ્દ | ષ્ધ | ષ્ન | ષ્પ | ષ્ફ | ષ્બ | ષ્ભ | ષ્મ | ષ્ય | ષ્ર | ષ્લ | ષ્ળ | ષ્વ | ષ્શ | ષ્ષ | ષ્સ | ષ્હ |

| સ | સ્ક | સ્ખ | સ્ગ | સ્ઘ | સ્ઙ | સ્ચ | સ્છ | સ્જ | સ્ઝ | સ્ઞ | સ્ટ | સ્ઠ | સ્ડ | સ્ઢ | સ્ણ | સ્ત | સ્થ | સ્દ | સ્ધ | સ્ન | સ્પ | સ્ફ | સ્બ | સ્ભ | સ્મ | સ્ય | સ્ર | સ્લ | સ્ળ | સ્વ | સ્શ | સ્ષ | સ્સ | સ્હ |

| હ | હ્ક | હ્ખ | હ્ગ | હ્ઘ | હ્ઙ | હ્ચ | હ્છ | હ્જ | હ્ઝ | હ્ઞ | હ્ટ | હ્ઠ | હ્ડ | હ્ઢ | હ્ણ | હ્ત | હ્થ | હ્દ | હ્ધ | હ્ન | હ્પ | હ્ફ | હ્બ | હ્ભ | હ્મ | હ્ય | હ્ર | હ્લ | હ્ળ | હ્વ | હ્શ | હ્ષ | હ્સ | હ્હ |

Romanization

Gujarati is romanized throughout Wikipedia in "standard orientalist" transcription as outlined in Masica (1991:xv). Being "primarily a system of transliteration from the Indian scripts, [and] based in turn upon Sanskrit" (cf. IAST), these are its salient features: subscript dots for retroflex consonants; macrons for etymologically, contrastively long vowels; h denoting aspirated stops. Tildes denote nasalized vowels and underlining denotes murmured vowels.

Vowels and consonants are outlined in the tables below. Hovering the mouse cursor over them will reveal the appropriate IPA symbol. Finally, there are three Wikipedia-specific additions: f is used interchangeably with ph, representing the widespread realization of /pʰ/ as [f]; â and ô for novel characters ઍ [æ] and ઑ [ɔ]; ǎ for [ə]'s where elision is uncertain. See Gujarati phonology for further clarification.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Unicode

Gujarati script was added to the Unicode Standard in October, 1991 with the release of version 1.0.

The Unicode block for Gujarati is U+0A80–U+0AFF:

| Gujarati[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+0A8x | ઁ | ં | ઃ | અ | આ | ઇ | ઈ | ઉ | ઊ | ઋ | ઌ | ઍ | એ | |||

| U+0A9x | ઐ | ઑ | ઓ | ઔ | ક | ખ | ગ | ઘ | ઙ | ચ | છ | જ | ઝ | ઞ | ટ | |

| U+0AAx | ઠ | ડ | ઢ | ણ | ત | થ | દ | ધ | ન | પ | ફ | બ | ભ | મ | ય | |

| U+0ABx | ર | લ | ળ | વ | શ | ષ | સ | હ | ઼ | ઽ | ા | િ | ||||

| U+0ACx | ી | ુ | ૂ | ૃ | ૄ | ૅ | ે | ૈ | ૉ | ો | ૌ | ્ | ||||

| U+0ADx | ૐ | |||||||||||||||

| U+0AEx | ૠ | ૡ | ૢ | ૣ | ૦ | ૧ | ૨ | ૩ | ૪ | ૫ | ૬ | ૭ | ૮ | ૯ | ||

| U+0AFx | ૰ | ૱ | ૹ | ૺ | ૻ | ૼ | ૽ | ૾ | ૿ | |||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Further details regarding how to use Unicode for creating Gujarati script can be found on Wikibooks: How to use Unicode in creating Gujarati script.

Gujarati keyboard layouts

ISCII

The Indian Script Code for Information Interchange (ISCII) code-page identifier for Gujarati script is 57010.

See also

- Gujarati Braille

- Wikibooks: How to use Unicode in creating Gujarati script

- Unicode and HTML

- Yudit - open source tool for editing in Gujarati and other Unicode scripts.

- [[b:Gujarati|Gujarati course in Wikibooks]

References

- "ScriptSource - Gujarati". Retrieved 2017-02-13.

- Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy. Oxford University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3.

- Mistry 1996, p. 391.

- Shastri, Parth (2014-02-21). "Mahajans ate away Gujarati's 'top line'". The Times of India. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- Tisdall 1892, p. 19.

- Mistry 1996, p. 393.

- Mistry 2001, p. 274.

- Miller, Christopher (2010). "A Gujarati Origin for Scripts of Sumatra, Sulawesi and the Philippines" (PDF). Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society. 36 (1): 276. doi:10.3765/bls.v36i1.3917. ISSN 2377-1666.

- Mistry 1996, pp. 391–392.

- Tisdall 1892, p. 20.

- "Sanskrit Alphabet". www.user.uni-hannover.de. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Dwyer 1995, p. 18.

- Cardona & Suthar 2003, p. 668.

- Mistry 1996, p. 392.

Bibliography

- Cardona, George; Suthar, Babu (2003), "Gujarati", in Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh (eds.), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5.

- Dwyer, Rachel (1995), Teach Yourself Gujarati, London: Hodder and Stoughton, archived from the original on 2008-01-02.

- Masica, Colin (1991), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

- Mistry, P.J. (2001), "Gujarati", in Garry, Jane; Rubino, Carl (eds.), An encyclopedia of the world's major languages, past and present, New England Publishing Associates.

- Mistry, P.J. (1996), "Gujarati Writing", in Daniels; Bright (eds.), The World's Writing Systems, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195079937.

- Tisdall, W.S. (1892), A Simplified Grammar of the Gujarati Language : together with A short reading book and vocabulary, London : Kegan Paul, Trench, Trúbner.

External links

- TDIL: Ministry of Communication & Information Technology, India

- Gujarati/Sanskrit alphabet with an extensive list of conjuncts

- Gujarati Wiktionary

- Gujarati Editor

- Example of Gujarati literature.

Keyboard and script resources

- The India Linux Project - Gujarati

- MS Windows keyboard layout reference for major world languages

- Sun Microsystems reference: Indic keyboard layouts

- Linux: Indic language support

- Fedora project Gujarati keyboard layout: I18N/Indic/GujaratiKeyboardLayouts - Fedora Project Wiki