2000 Italian Grand Prix

The 2000 Italian Grand Prix (formally the LXXI Gran Premio Campari d'Italia) was a Formula One motor race held on 10 September 2000 at the Autodromo Nazionale di Monza near Monza, Lombardy, Italy before a crowd of between 110,000 to 120,000 spectators. It was the 14th round of the 2000 Formula One World Championship and the final Grand Prix of the season to be held in Europe. Ferrari driver Michael Schumacher won the 53-lap race from pole position. Mika Häkkinen finished second in a McLaren car with Ralf Schumacher third for the Williams team.

| 2000 Italian Grand Prix | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Race 14 of 17 in the 2000 Formula One World Championship

| |||||

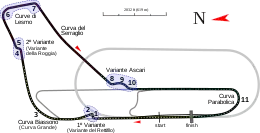

Autodromo Nazionale di Monza (Modified in 2000) | |||||

| Race details[1][2] | |||||

| Date | 10 September 2000 | ||||

| Official name | LXXI Gran Premio Campari d'Italia | ||||

| Location | Autodromo Nazionale di Monza, Monza, Lombardy, Italy | ||||

| Course | Permanent racing facility | ||||

| Course length | 5.793 km (3.600 miles) | ||||

| Distance | 53 laps, 306.764 km (190.614[3] miles) | ||||

| Weather | Sunny with temperatures reaching up to 29 °C (84 °F)[4] | ||||

| Pole position | |||||

| Driver | Ferrari | ||||

| Time | 1:23.770 | ||||

| Fastest lap | |||||

| Driver |

| McLaren-Mercedes | |||

| Time | 1:25.595 on lap 50 | ||||

| Podium | |||||

| First | Ferrari | ||||

| Second | McLaren-Mercedes | ||||

| Third | Williams-BMW | ||||

|

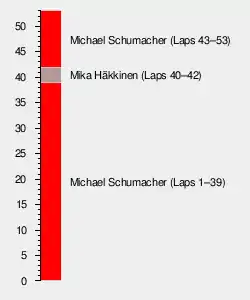

Lap leaders | |||||

Häkkinen was the World Drivers' Championship leader and his team McLaren led the World Constructors' Championship going into the race. Michael Schumacher maintained his start line advantage and withstood Häkkinen's attempts to pass him going into the first corner. Further around the lap, a collision involving four cars prompted the deployment of the safety car and a fire marshal Paolo Gislimberti was struck by a flying wheel from Heinz-Harald Frentzen's car. When the safety car was withdrawn at the conclusion of lap eleven, Michael Schumacher began to immediately pull clear from Häkkinen and kept the lead until his pit stop on the 39th lap. When Häkkinen made his own pit stop three laps later, Michael Schumacher regained the lead which he held to achieve his sixth victory of the 2000 season and the 41st of his career to go level with Ayrton Senna; Häkkinen followed 3.8 seconds later in second.

As a consequence of the final race results, Schumacher reduced Häkkinen's lead in the World Drivers' Championship to two points, with David Coulthard a further 17 points back. Rubens Barrichello who was caught up in the first lap accident was mathematically ruled out of clinching the title. In the World Constructors' Championship, McLaren's eight-point advantage going into the Grand Prix was reduced to four, with three rounds of the season remaining. Gislimberti later died in hospital and his death caused safety measures in Formula One to be reviewed.

Background

The 2000 Italian Grand Prix was the thirteenth of the seventeen rounds of the 2000 Formula One World Championship and took place at the 5.793 km (3.600 mi) clockwise Autodromo Nazionale di Monza close to Monza in Lombardy, Italy on 10 September 2000.[1][2] It was the final Grand Prix of the season to be held in Europe.[5] For the Grand Prix there were a total of eleven teams (each representing a different constructor) each with two drivers participating with no changes from the season entry list.[6] Sole tyre supplier Bridgestone brought the medium and the hard dry compounds to the race,[7] which were the hardest available compounds to teams.[8] Since the Monza Circuit saw high average lap times, each of the eleven teams installed low incidence ailerons on their cars and used the wings observed at the German Grand Prix.[9]

Going into the race, McLaren driver Mika Häkkinen led the World Drivers' Championship with 74 points, ahead of Ferrari's Michael Schumacher on 68 points and Häkkinen's teammate David Coulthard on 61 points. Rubens Barrichello of Ferrari was fourth with 49 points with Williams driver Ralf Schumacher fifth on 20 points.[10] In the World Constructors' Championship McLaren were leading with 125 points, Ferrari and Williams were second and third with 117 and 30 points, respectively, while Benetton were fourth with 18 points and Jordan with 13 points were in fifth position.[10]

At the previous race in Belgium, the gap between Häkkinen (who won three of the preceding four races) and Michael Schumacher had extended to six points.[5] Häkkinen started from pole position and maintained the lead until he lost control of his car at Stavelot corner on the 13th lap. He later managed to lap faster than Michael Schumacher and passed the German while both drivers were lapping BAR driver Ricardo Zonta with four laps remaining and held it to win the race.[11] The overtaking manoeuvre was heralded by the worldwide press and many people involved in Formula One as "the best ever manoeuvre in grand prix racing".[12] Michael Schumacher remained confident about his title chances: "With only six points between Mika and I and four more races to go, I am still optimistic about our chances. One win or a retirement before the end of the season can change the whole picture either way."[13]

Over the month of July, the Autodromo Nazionale di Monza race track's main straight was straightened and the Variante Goodyear and Seconda Variante chicanes were reconfigured by the race organisers to become a series of narrower corners with the exit away from the entry of turn one.[14][15] The run-off areas around the two sections of the circuit were enlargened.[16] These changes were done at the request of the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA; Formula One's governing body).[8] Some of the drivers, however, were unhappy with the modifications, though, as there were fears of a multi-car accident on the first lap.[17] Coulthard claimed that the new corner would make braking more difficult and was concerned over the number of penalties issued to other competitors.[17] However, Michael Schumacher believed his and other teams would be less concerned with suspension damage.[17] Jean Alesi of Prost who was the first driver to test the new circuit, said that it would be easier for drivers to pull off the track in the event of a technical issue.[14]

Following the Belgian Grand Prix on 27 August, the teams conducted a four-day testing session at Monza and concentrated on optimising their car set-ups for low downforce.[18] Arrows' Jos Verstappen set the quickest times on the first day, ahead of Sauber's Pedro Diniz.[19] Coulthard was quickest on the second day. Benetton driver Giancarlo Fisichella crashed at high speed into the Ascari chicane, bringing a brief halt to testing.[20] He visited Rome to undergo a medical examination and was diagnosed with an inflamed tendon in his right ankle, but was cleared to race having been advised to take five days of rest.[21] Jacques Villeneuve set the quickest times on the third day for BAR as rain shortened the team's running. Minardi's Gastón Mazzacane had a high speed accident at the Ascari chicane, forcing testing to be stopped.[22] Ralf Schumacher was fastest on testing's fourth and final day. Michael Schumacher's car developed a malfunction and pulled off the race track, limiting Ferrari's testing time as the car's power unit was changed.[23]

Practice

There were four practice sessions that preceded Sunday's race—two one-hour sessions on Friday, and two 45-minute sessions on Saturday.[24] Drivers piloted their cars on a hot track surface and in dry conditions.[25] Barrichello set the first session's fastest time on Friday morning with a lap of 1 minute and 25.057 seconds that he set with ten minutes of the session remaining on his final timed lap.[26][27] He was three-tenths of a second ahead of Jordan's Jarno Trulli in second position. Michael Schumacher was one-tenth of a second off Trulli's pace in third, while Coulthard set the fourth fastest time. The two Arrows drivers were fifth and sixth fastest; Pedro de la Rosa ahead of Jos Verstappen. Heinz-Harald Frentzen, Fisichella, Villeneuve and Benetton's Alexander Wurz rounded out the top ten fastest drivers of the session.[28] Some drivers ran wide onto the Rettifilo chicane at least once during the session.[27] Häkkinen set no timed lap as a consequence of a slipping clutch and the problem was fixed for the second session.[28]

It was sunny and warm for the second practice session.[29] Barrichello was again fastest despite not improving his time from the first session;[26][30] Michael Schumacher was second-fastest. Trulli set the third fastest lap, with the two McLaren drivers fourth and fifth, Häkkinen ahead of Coulthard. Jaguar's Eddie Irvine, De La Rosa, Diniz, Verstappen and Sauber's Mika Salo completed the top ten drivers.[30] Alesi's Prost was afflicted by a hydraulic leak; this restricted him to three timed laps, and he was slowest overall. Wurz suffered a similar problem that saw him stop his car at the exit to Parabolica turn and set the 18th fastest lap. Mazzacane spun off and took no further part in the session. Coulthard spun off under braking into the second Lesmo right-hand corner and beached his car in the gravel, which broke the McLaren's left-rear suspension arm and ended his running early.[8][29][30]

At the drivers' meeting held on Friday, drivers agreed to adopt a careful approach at the first chicane following a series of crashes at the first corner in recent events. They would not be imposed a ten-second penalty if they did not gain a position or an advantage after concerns were raised about it.[31] The Saturday practice sessions were again held in dry and sunny conditions.[32] Michael Schumacher set the fastest time of the third session, a 1:24.262.[33] The Williams drivers were within the top five positions—Jenson Button with a lap set late in the session to go second and Ralf Schumacher fifth—they were separated by Coulthard and Barrichello in third and fourth.[34] Fisichella recorded the sixth fastest lap time. Villeneuve, Häkkinen, Salo and Johnny Herbert for Jaguar rounded out the top ten.[33] Frentzen went wide onto the edge of some dust and damaged the front-left corner of his car in an accident against the tyre barrier at Parabolica corner.[32][35] Häkkinen ran onto the gravel and had difficulty regaining control of his car.[36]

In the final practice session, Michael Schumacher again set the fastest lap time, a 1:23.904; Barrichello set the third fastest time. They were separated by Häkkinen with teammate Coulthard recording the fourth fastest time.[35] Ralf Schumacher lapped quicker to remain in fifth position, ahead of his teammate Button in sixth after he was unable to replicate third session pace.[37] Fisichella, Zonta, Villeneuve and Irvine (who suffered a rear suspension failure but regained control of his car) completed the top ten ahead of qualifying. Mazzacane again suffered problems with his car when his engine ran out of air pressure and was forced to stop on the track while Wurz did not record any laps because of a fuel pick-up issue.[35] Frentzen set no lap times during the session while his car was being repaired.[37]

Qualifying

.jpg.webp)

Saturday's afternoon one hour qualifying session saw each driver limited to twelve laps, with the starting order decided by their fastest laps. During this session, the 107% rule was in effect, which necessitated each driver set a time within 107 per cent of the quickest lap to qualify for the race.[24] The session was held in dry weather.[38] Michael Schumacher achieved his sixth pole position of the season, and the 29th of his career, with a time of 1:23.770.[39][40] Although he was happy with his car and tyres, he said that he did not make the best of session because of making a mistake at the first chicane during his first run. Michael Schumacher was joined on the front row by Barrichello who recorded a lap time 0.027 seconds slower with ten minutes left and was happy to start alongside his teammate.[41][42] Häkkinen qualified third after having handling difficulties and his McLaren misfiring with a fuel pressure fault which distracted him during his final two timed laps.[5][43] Villeneuve achieved BAR's best qualifying performance at the time in fourth on his final fast lap with 12 minutes remaining,[5][42] nearly half a second behind Michael Schumacher. He said he was happy with his performance despite an minor error on his first run.[39][41] Häkkinen's teammate Coulthard took fifth after encountering traffic during qualifying and vehicle balance problems. He was blocked by Frentzen leaving the Rettifilo chicane on his last run.[41][42][43] Trulli and Frentzen set the sixth and eighth fastest times respectively for Jordan;[44] Trulli reported no problems while Frentzen was impeded by De La Rosa that lost him approximately four-tenths of a second.[41][43] Ralf Schumacher, seventh, expressed disappointment in his performance that saw him abort two runs due to his braking position.[32][43]

De La Rosa's made some adjustments to his vehicle that saw him qualify tenth with a fast lap which he recorded with two minutes remaining.[42][43] His teammate Verstappen qualified eleventh having been required to drive two of his team's cars when they developed hydraulic and engine problems that saw him stop in the gravel at Ascari corner.[40][41] Button qualified twelfth after overheating his tyres and being unable to control his car after reducing its downforce.[45] Wurz, 13th, used the session to familiarise himself with Benetton's spare car after a lack of running in practice.[32][43] He was ahead of Irvine in the faster of the two Jaguar's, who set a best time that was one-tenth of a second faster than his own teammate Johnny Herbert in 18th;[44] both were disadvantaged at the lack of straightline speed.[32] Salo was 15th quickest for the Sauber team,[41] ahead of his own teammate Diniz whose car handled badly under braking for the Rettifilo and della Roggia chicanes.[42] The pair were marginally quicker than Zonta who encountered gear selection problems in his race car that saw him stop on the track, and switched to his team's spare vehicle setup for Villeneuve.[8][32] Alesi and Nick Heidfeld in the Prosts were 18th and 19th after driving with understeer.[43] They qualified in front of the Minardis of Marc Gené and Gastón Mazzacane who were 21st and 22nd respectively;[44] Mazzacane stopped his car at the Lesmo corners with an electrical fault and returned to the pit lane to drive the spare car.[8][40]

Qualifying classification

| Pos | No | Driver | Constructor | Time | Gap | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | Ferrari | 1:23.770 | ||||

| 2 | 4 | Ferrari | 1:23.797 | +0.027 | |||

| 3 | 1 | McLaren-Mercedes | 1:23.967 | +0.197 | |||

| 4 | 22 | BAR-Honda | 1:24.238 | +0.468 | |||

| 5 | 2 | McLaren-Mercedes | 1:24.290 | +0.520 | |||

| 6 | 6 | Jordan-Mugen-Honda | 1:24.477 | +0.707 | |||

| 7 | 9 | Williams-BMW | 1:24.516 | +0.746 | |||

| 8 | 5 | Jordan-Mugen-Honda | 1:24.786 | +1.016 | |||

| 9 | 11 | Benetton-Playlife | 1:24.789 | +1.019 | |||

| 10 | 18 | Arrows-Supertec | 1:24.814 | +1.044 | |||

| 11 | 19 | Arrows-Supertec | 1:24.820 | +1.050 | |||

| 12 | 10 | Williams-BMW | 1:24.907 | +1.137 | |||

| 13 | 12 | Benetton-Playlife | 1:25.150 | +1.380 | |||

| 14 | 7 | Jaguar-Cosworth | 1:25.251 | +1.481 | |||

| 15 | 17 | Sauber-Petronas | 1:25.322 | +1.552 | |||

| 16 | 16 | Sauber-Petronas | 1:25.324 | +1.554 | |||

| 17 | 23 | BAR-Honda | 1:25.337 | +1.567 | |||

| 18 | 8 | Jaguar-Cosworth | 1:25.388 | +1.618 | |||

| 19 | 14 | Prost-Peugeot | 1:25.558 | +1.788 | |||

| 20 | 15 | Prost-Peugeot | 1:25.625 | +1.855 | |||

| 21 | 20 | Minardi-Fondmetal | 1:26.336 | +2.566 | |||

| 22 | 21 | Minardi-Fondmetal | 1:27.360 | +3.590 | |||

| 107% time: 1:29.634 | |||||||

Source:[46] | |||||||

Warm-up

The drivers took to the track at 09:30 Central European Summer Time (UTC +1) for a 30-minute warm-up session.[24] It took place in dry weather conditions following a spell of mist that fell on the circuit.[47] Zonta set the fastest lap time of the session, a 1:26.448,[48][49] which he set with nine minutes left despite encountering a major oversteer at Parabolica corner.[8] He was six hundredths of a second quicker than Häkkinen in second position who reached that place in the final seconds of warm-up.[49] Michael Schumacher had the third fastest lap time, ahead of Coulthard in fourth, Verstappen in fifth and Salo in sixth place.[47] No major incidents occurred during the session.[49] Coulthard lost control of his McLaren in a spin that he had at the exit of the second chicane due to a rear suspension fault but he was able to return to the circuit.[50][51] Irvine spun at the second Lesmo right-hand turn but got his car facing correctly and resumed driving.[48][51]

Race

The race started with around 110,000 to 120,000 people in attendance at 14:00 local time.[5][52] It lasted 53 laps over a distance of 306.764 km (190.614 mi).[3] The conditions for the race were dry with the air temperature 25 °C (77 °F) and the track temperature 34 and 37 °C (93 and 99 °F).[38][53] Every competitor began on the medium compound tyre since it was three-tenths of a second faster than the hard compound tyre. Blistering of the tyres were more of a factor at the Grand Prix since compound wear was being increased by braking hard for the first chicane.[54] Heidfeld's car was being worked on by mechanics who managed to get to the side of the track before the formation lap begun to avoid incurring a penalty.[11] Michael Schumacher maintained his lead going into the first corner withstanding Häkkinen's attempts to pass on the inside by switching lines.[55] Barrichello on the inside line made a slow start and dropped from second to fifth position,[8][56] which saw the fast starting Villeneuve become stuck behind the Ferrari.[57][58] Heading into the first corner, Salo and Irvine made contact and both drivers went into Diniz. Irvine had suspension damage that necessitated his retirement from the Grand Prix while Salo sustained a left-rear puncture and Diniz's front wing was removed.[55][59]

Entering the Variante della Roggia chicane, (the circuit's second chicane) a multi-car accident occurred.[60][61] Barrichello attempted to pass Trulli on the inside and the following Frentzen on a light fuel load struck the left-rear corner of teammate Trulli's vehicle with his right-front corner at nearly 300 km/h (190 mph) after losing control of his car. Frentzen then hit the right-rear corner of Barrichello's Ferrari with his vehicle's left-front corner. All three cars spun and collected Coulthard who was in the process of attempting to turn into the chicane.[11][57] All four cars spun into the gravel trap and created a thick cloud of dust and smoke.[56] The right front wheel from Frentzen's car struck fire marshal Paolo Gislimberti (who had moved from his post and took his fire extinguisher with him) on the upper body exposed through the barrier on the circuit's left-hand side. The following four drivers, Villeneuve, Ralf Schumacher, Button and Wurz, passed through the scene without incident.[5][57] Behind them, Herbert was blinded by the cloud and the unsighted De La Rosa rammed into the rear of Herbert's Jaguar. De La Rosa was launched around 15 feet (4.6 m) into the air, barrel rolling and somersaulting. He went over the top of Coulthard's McLaren and landed upside down across the suspension of Barrichello's car in the gravel.[56][59][60] All involved drivers sustained no serious injuries. The rest of the field was able to pass through the accident scene without incident.[59] Herbert retired in the pit lane with a missing wheel and Zonta sustained a front puncture from being hit by De La Rosa.[55][62]

FIA race director Charlie Whiting did not stop the race and abort the first start to allow those who were involved in the accident to return to the pit lane and get into their spare cars.[11][56] Whiting decided to deploy the safety car at the conclusion of the first lap to enable marshals to remove strands of carbon fibre on the circuit and extricate the cars in the gravel trap.[53][56] Gislimberti suffered from head and chest injuries and was given a heart massage before he was tended to by doctors Sid Watkins and Gary Hartstein.[57][63] Watkins and Harstein had not been made aware of Gislimberti's condition because of inaccurate initial reports and were not told to drive to the accident scene until race control received notice of Gislimberti's injuries.[57] Gislimberti was later transported in cardiocirculatory arrest to San Gerardo Hospital by ambulance since travel by helicopter would have taken longer.[63][64] Salo became the fifth driver to pit on lap eight; his mechanics fitted a new engine cover and sidepods to repair handling problems.[65] The safety car period was extended primarily due to the wait for Harstein and Watkins to return to their position in the medical car at the exit of the pit lane after they had administered aid to Gislimberti and to instruct marshals to not leave the stricken vehicles at the back of the gravel trap but rather move them to a safer area.[57]

During the end of the safety car period on lap 11, Michael Schumacher accelerated hard and then braked more hard to generate heat into his brakes and tyres after bunching the pack up on the back straight between the Ascari chicane and Parabolica turn in preparation for the return to racing speeds.[56][66] The five cars behind Michael Schumacher were caught out by this sudden decrease in speed in the concertina effect.[5][45][58] Button consequently swerved left onto the grass to avoid an accident with Villeneuve, colliding with the guardrail barriers and sustained damage to one of his car's wheels.[45][66] He later went off into the gravel trap at the Parabolica corner after being unable to steer his car and became the race's seventh retirement on lap eleven.[11][55] When the race restarted on lap twelve, Michael Schumacher led, while Häkkinen and Villeneuve were running second and third. Behind them were Ralf Schumacher, Fisichella, and Wurz.[65] Michael Schumacher began to immediately pull away from Häkkinen as he set consecutive fastest laps. Further down the field, Wurz overtook Diniz and Mazzacane for tenth position.[11]

At the start of lap 13, Michael Schumacher led Häkkinen by 1.4 seconds.[65] Further back, Zonta passed Heidfeld to take ninth. On lap 14, Zonta moved into seventh position after passing Gené and Wurz.[11] Meanwhile, Verstappen overtook Fisichella on the inside into the first chicane to take fifth position on the 15th lap.[11][58] Villeneuve became the race's next retirement from third position when he pulled over to the side of the track with an electrical fault that cut out his engine on that lap.[53][62] On the 16th lap, Ralf Schumacher briefly lost control of his car and was overtaken by Verstappen and Zonta.[11][58] Heidfeld retired after his engine failed and spun off at the Variante della Roggia chicane on the same lap,[55][65] where he stalled his car on the track.[11] A second deployment of the safety car was put on standby as marshals had difficulty removing his car from the circuit.[53][59] There were no more retirements after that and attention was focused on the battles at the front and rear of the running order.[59]

Salo passed Mazzacane to move into ninth position on lap 17.[53] At the start of the 19th lap, Zonta tried to pass Verstappen heading into the Variante Goodyear chicane, but Verstappen moved onto an early defensive line to prevent Zonta from moving ahead.[53] Zonta attempted to overtake Verstappen on the inside into the Variante della Rogia chicane to move into third place two laps later, but was unable to complete it because he ran wide and allowed Verstappen to draw alongside on the outside. Verstappen briefly returned to third position before Zonta was able to get ahead of Verstappen after exiting the chicane on the same lap as a result of him driving with a more powerful engine.[11][53][56] Verstappen attempted to repass Zonta for third position but was unable to do so.[58] Michael Schumacher lapped consistently in the 1:26 range, setting the new fastest lap of the race on lap 22, a 1:26.428, to extend his lead over Häkkinen to 5.4 seconds, who in turn was 9.9 seconds in front of Zonta. Verstappen in fourth was a further 2.9 seconds behind, but was drawing ahead of Ralf Schumacher in fifth.[65] On lap 24, Zonta became the first front runner to make a scheduled pit stop for fuel and tyres and emerged in eleventh position.[11][60]

Salo overtook Wurz for sixth on lap 25. During laps 26 and 27, Zonta moved into ninth position after he overtook Mazzacane and Diniz. Salo made a second pit stop on lap 29 and emerged in tenth place.[53] Verstappen made his pit stop four laps later and returned to the circuit in seventh position.[11][53] Zonta made his third and final pit stop of the race for fuel on lap 37 and dropped to eighth position.[11][58] The time it took at Zonta's final pit stop prevented him from finishing in the first three places.[59] Since little fuel was used during the safety car period, the Grand Prix leaders were seeking to make their pit stops after two-thirds race distance.[60] Michael Schumacher took his pit stop on the 40th lap and was stationary for 7.2 seconds.[58][60] He rejoined the circuit 13.6 seconds behind Häkkinen, who moved into the race lead.[65] Michael Schumacher immediately began pushing hard to ensure that Häkkinen would not have a significant advantage following his pit stop.[59] Three laps later, Häkkinen made a pit stop that lasted 6.6 seconds.[58] He rejoined the Grand Prix behind Michael Schumacher with a deficit on twelve seconds.[53][65] Fisichella was the final driver to make a scheduled stop on lap 44.[11][65] His pit stop was problematic: he stalled with a clutch system fault and his mechanics push-started his Benetton and he rejoined in eleventh.[53][55]

At the completion of lap 45, with the scheduled pit stops completed, the race order was Michael Schumacher, Häkkinen, Ralf Schumacher, Verstappen, Wurz, and Zonta.[65] Zonta went straight onto the escape road near the Variante Goodyear chicane but retained sixth.[53] Häkkinen set out to close up to Michael Schumacher while encountering slower cars and being impeded by Mazzacane.[60] He set the race's fastest lap of 1:25.595 on lap 50 and drew to with 6.2 seconds of Michael Schumacher when Schumacher eased off slightly.[56][65] Michael Schumacher was able to maintain his lead and finished first in his sixth victory of 2000 and the 41st of his career to go level with Ayrton Senna in a time of 1'27:31.368, at an average speed of 210.286 km/h (130.666 mph).[56][67] Häkkinen followed 3.8 seconds later in second, ahead of Ralf Schumacher who achieve his second successive podium finish in third. Verstappen took fourth, Wurz finished fifth,[11] and Zonta completed the points scorers in sixth, 1.8 seconds behind Wurz.[60] Salo, Diniz, Gené, Mazzacane and Fisichella completed the next five positions a lap behind the winner, with Alesi the final classified finisher.[67]

Post-race

The top three drivers appeared on the podium to collect their trophies and in the subsequent press conference.[24] Michael Schumacher broke into tears when asked if matching Senna's number of victories meant a lot to him.[5] He later regained his composure and spoke about how important it was to maintain the life of the engine at the circuit.[68] Michael Schumacher revealed that the cause of his emotion was of him thinking about Senna's death at the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix and said that he was surprised at how the media reacted to the moment which said that Schumacher "was human after all".[69] Häkkinen revealed that his team made modifications to his car at his pit stop which contributed to him setting the fastest lap of the race.[68] He also admitted that he was unable to catch Michael Schumacher due to the presence of the two Minardis which cost him time.[68] Ralf Schumacher said he was not worried from being challenged by Verstappen and Zonta during the event because of the Williams's quick pace.[68] He also was confident that Williams had confirmed itself as the third strongest team in Formula One.[70]

Button blamed the accident where he was caught out by race leader Michael Schumacher braking and accelerating to maintain warm brake temperatures on Schumacher, asking: "I thought you weren't allowed to do that?"[71] Villeneuve disagreed, saying: "Michael was only doing what you're meant to do in that situation. The guys behind should calm down."[60] Schumacher said he had expected other drivers to generate heat into their brakes and apologised those competitors behind him if he had created issues for them.[71] Verstappen said he was pleased to finish fourth and commented on his pace: "I was pushing the whole race because I knew that I had to make up time from the bad start."[70] Wurz commented that he was happy to finish fifth after a lack of preparation time, adding: "fifth place made up for all this bad luck so far, and I'm really happy now with it."[72] Zonta praised the speed of his car for allowing him to finish sixth and overtake. He added him qualifying better would have allowed him to challenge for an higher finishing position or a podium result.[62]

Following discussions with the drivers involved in the first lap accidents, the stewards deemed it to be "a racing accident", with no driver in particular to blame.[57] Barrichello placed blame upon Frentzen for starting the lap one accident at the Variante della Roggia corner. He demanded that Frentzen be banned for ten races. Barrichello also added that his helmet was damaged from his collision with De La Rosa.[73] Frentzen reacted by suggesting that Barrichello braked earlier which forced him to make contact with teammate Trulli.[74] Whiting defended his decision not to stop the race saying that the safety car was deployed as all cars involved were in the run-off areas and that he believed stopping the race would be dangerous. However, he admitted to not being aware of Gislimberti's condition when making the decision.[75] Jordan team principal Eddie Jordan believed that Whiting had made the right choice and praised the safety of the modern Formula One car for protecting drivers.[76]

Bernie Ecclestone, the owner of Formula One's commercial rights, called for the removal of chicanes from racing circuits labelling them "silly and unnecessary".[75] FIA president Max Mosley subsequently announced that safety measures would be reviewed and stated a review of the Monza track would take place.[77] Mosley believed that no driver was responsible for causing the accident but stressed to competitors that it was their responsibility for being aware when bunched up at the start of a Grand Prix.[78] Former driver Jacques Laffite advocated an electronic warning system for marshals and believed that a review of chicanes should have taken place.[79]

Gislimberti never regained consciousness and he was pronounced dead at Monza Hospital.[8][63] The Trento-born volunteer firefighter and lead water control engineer in the province, who was vice-president of the CEA Squadra Corse firefighting organisation, predeceased his wife of two years Elena (who was pregnant with his child) and other family members.[80][81] His autopsy released two days later determined his cause of death was head trauma.[82] On 15 September, he was given a funeral at the San Ulderico church, Lavis and attended by several drivers, friends and colleagues.[83] Hours after the race, five cars involved in the accident were impounded by Italian authorities.[84] Magistrate Salvatore Bellomo opened a formal investigation into the crash and interviewed drivers.[85] The investigating body examined all five cars which were released back to the teams on 12 September.[86] The investigation was closed in June 2001 following a technical examination which concluded that Gislimberti was killed instantly.[87] As a result of Gislimberti's death, the strength of the wheel tethers was doubled to stop flying tyres being a danger to the drivers, safety officials and fans. The chassis would be strengthened and enhanced crash resistance would be tested.[88]

With his win, Michael Schumacher reduced Häkkinen's advantage in the World Drivers' Championship to two points. Coulthard remained in third place with 61 points. Barrichello's retirement at the Grand Prix ruled out any chance of him becoming World Champion and Ralf Schumacher's third-place result saw him retain fifth position with 24 points.[10] In the World Constructors' Championship, Ferrari's victory allowed them to reduce McLaren's lead to four points. Williams remained in third position with 34 points. Benetton in fourth place increased the gap over Jordan in fifth position to a seven-point advantage, with three races of the season remaining.[10]

Race classification

Drivers who scored championship points are denoted in bold.

| Pos | No | Driver | Constructor | Laps | Time/Retired | Grid | Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | Ferrari | 53 | 1:27:31.638 | 1 | 10 | |

| 2 | 1 | McLaren-Mercedes | 53 | +3.810 | 3 | 6 | |

| 3 | 9 | Williams-BMW | 53 | +52.432 | 7 | 4 | |

| 4 | 19 | Arrows-Supertec | 53 | +59.938 | 11 | 3 | |

| 5 | 12 | Benetton-Playlife | 53 | +1:07.426 | 13 | 2 | |

| 6 | 23 | BAR-Honda | 53 | +1:09.292 | 17 | 1 | |

| 7 | 17 | Sauber-Petronas | 52 | +1 Lap | 15 | ||

| 8 | 16 | Sauber-Petronas | 52 | +1 Lap | 16 | ||

| 9 | 20 | Minardi-Fondmetal | 52 | +1 Lap | 21 | ||

| 10 | 21 | Minardi-Fondmetal | 52 | +1 Lap | 22 | ||

| 11 | 11 | Benetton-Playlife | 52 | +1 Lap | 9 | ||

| 12 | 14 | Prost-Peugeot | 51 | +2 Laps | 19 | ||

| Ret | 15 | Prost-Peugeot | 15 | Spun off | 20 | ||

| Ret | 22 | BAR-Honda | 14 | Electrical | 4 | ||

| Ret | 10 | Williams-BMW | 10 | Accident | 12 | ||

| Ret | 8 | Jaguar-Cosworth | 1 | Collision damage | 18 | ||

| Ret | 4 | Ferrari | 0 | Collision | 2 | ||

| Ret | 2 | McLaren-Mercedes | 0 | Collision | 5 | ||

| Ret | 6 | Jordan-Mugen-Honda | 0 | Collision | 6 | ||

| Ret | 5 | Jordan-Mugen-Honda | 0 | Collision | 8 | ||

| Ret | 18 | Arrows-Supertec | 0 | Collision | 10 | ||

| Ret | 7 | Jaguar-Cosworth | 0 | Spun off | 14 | ||

Championship standings after the race

- Bold text indicates who still has a theoretical chance of becoming World Champion.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Note: Only the top five positions are included for both sets of standings.

References

- "2000 Italian GP". ChicaneF1. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- "Italian Grand Prix 2000 results". ESPN. Archived from the original on 7 September 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

"2000 Italian Grand Prix". Motor Sport. Archived from the original on 27 March 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022. - Callaghan, Terry; Kelly, Paul (10 September 2000). "Formula One: M. Schumacher closes to within two points of Hakkinen after emotional victory". The Auto Channel. Archived from the original on 27 November 2004. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- "Weather info for the 2000 Italian Grand Prix". Weather Underground. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- Goodman, Louise (2000). "Italian Grand Prix". Beyond the Pit Lane: The Grand Prix Season from the Inside. London, United Kingdom: Headline Publishing Group. pp. 274–275, 282–289. ISBN 0-7472-3541-4. Retrieved 13 April 2022 – via Open Library.

- "Formula One 2000 Italian Grand Prix Information". Motorsport Stats. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- Tytler, Ewan (6 September 2000). "The Italian GP Preview". Atlas F1. Haymarket Publications. Archived from the original on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- Makkaveev, Vladimir (October 2000). "Проклятие Королевского парка" [Queen's Park Curse]. Formula 1 Magazine (in Russian). 10: 30–38. Archived from the original on 25 June 2002. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- Piola, Giorgio (18 September 2000). "Ali ridottissime per la Ferrari" [Reduced wings for Ferrari]. Autosprint (in Italian) (37/2000): 46–69.

- "F1 Drivers' Championship Table 2000". crash.net. Crash Media Group. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Elizalde, Pablo (13 September 2000). "The Italian GP Review". Atlas F1. Haymarket Publications. 6 (37). Archived from the original on 10 April 2001. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- Allsop, Derick (27 August 2000). "Hakkinen acquires greatness in one move". The Independent. Independent Print Limited. Archived from the original on 16 July 2010. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- "Schumacher aims for 'special' victory". GPUpdate. JHED Media BV. 5 September 2000. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- "Drivers wary of Monza modifications". Formula1.com. Formula1.com Limited. 30 August 2000. Archived from the original on 18 April 2001. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- "Monza completes work in record time". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. 19 July 2000. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- "Monza track modified". Formula1.com. Formula1.com Limited. 23 August 2000. Archived from the original on 11 February 2001. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- "Drivers wary of first corner carnage at Monza". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. 2 September 2000. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- "Teams being testing at Monza". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. 29 August 2000. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- "Teams Back to Work at Monza – Day One". Atlas F1. Haymarket Publications. 29 August 2000. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- Righetti, Tom (30 August 2000). "Formula One: Fisichella crashes in Monza testing". The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- "Fisichella inflamed but fit for Italy". GPUpdate. JHED Media BV. 2 September 2000. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- "Rain Shortens Monza Testing – Day Three". Atlas F1. Haymarket Publications. 31 August 2000. Archived from the original on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- "Ralf Schumacher quickest in Friday testing at Monza". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. 1 September 2000. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- Domenjoz, Luc, ed. (2000). "Sporting regulations". Formula 1 Yearbook 2000–2001. Bath, Somerset: Parragon. pp. 220–221. ISBN 0-75254-735-6 – via Internet Archive.

- "Barrichello fastest in Friday First Free". F1Racing.net. 8 September 2000. Archived from the original on 10 January 2005. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- Gardner, John (8 September 2000). "Italian GP: Barrichello Paces Friday Practice". Speedvision. Archived from the original on 2 December 2000. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Free practice 1: Barrichello fastest from Trulli". Autosport. Motorsport Network. 8 September 2000. Archived from the original on 27 March 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Friday First Free Practice – Italian GP". Atlas F1. Haymarket Publications. 8 September 2000. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- "Ferrari sets Friday pace". F1Racing.net. 8 September 2000. Archived from the original on 10 January 2005. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Friday Second Free Practice – Italian GP". Atlas F1. Haymarket Publications. 8 September 2000. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- "New chicanes need more care, drivers agree". Autosport. Motorsport Network. 8 September 2000. Archived from the original on 27 March 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Free Practice + Qualifying". FIA.com. Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile. 9 September 2000. Archived from the original on 4 June 2001. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- "Saturday First Free Practice – Italian GP". Atlas F1. Haymarket Publications. 9 September 2000. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- "Free practice 3: Schumacher on top as Button flies". Autosport. Motorsport Network. 9 September 2000. Archived from the original on 27 March 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Saturday Second Free Practice – Italian GP". Atlas F1. Haymarket Publications. 9 September 2000. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- "Schumacher leads early on Saturday". F1Racing.net. 9 September 2000. Archived from the original on 10 January 2005. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Free practice 4: Schuey fastest...again". Autosport. Motorsport Network. 9 September 2000. Archived from the original on 27 March 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Grand Prix of Italy". Gale Force F1. 10 September 2000. Archived from the original on 18 February 2007. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- Gardner, John (9 September 2000). "Italian GP: Schumacher Leads Ferrari 1–2 in Qualifying". Speedvision. Archived from the original on 2 December 2000. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- "Ferrari paint the front row red". F1Racing.net. 9 September 2000. Archived from the original on 10 January 2005. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- "Schumacher on Pole; Qualifying Results – Italian GP". Atlas F1. Haymarket Publications. 9 September 2000. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- "Schumacher snatches pole from Barrichello". Autosport. Motorsport Network. 9 September 2000. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- "The Italian Grand Prix 2000 – Team and Driver comments – Saturday". Daily F1. 9 September 2000. Archived from the original on 18 October 2000. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- "Schumacher heads grid". BBC Sport. BBC. 9 September 2000. Archived from the original on 17 April 2001. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- Button, Jenson; Tremayne, David (2002). Jenson Button: My Life on the Formula One Rollercoaster. Bungay, Suffolk: Bantam Press. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-0-593-04875-7.

- "Italian GP Saturday qualifying". motorsport.com. Motorsport.com, Inc. 9 September 2000. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- Reuters (10 September 2000). "Sunday Warm-Up – Italian GP". Haymarket Publications. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- "Zonta sets warm-up pace". F1Racing.net. 10 September 2000. Archived from the original on 10 September 2005. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- Gardner, John (10 September 2000). "Italian GP: Zonta Leads Warm-Up". Speedvision. Archived from the original on 3 December 2000. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- "Zonta fastest in Sunday warm-up". Autosport. Motorsport Network. 10 September 2000. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- "Warm-Up". FIA.com. Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile. 10 September 2000. Archived from the original on 18 June 2001. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- D'Alessio, Paolo (October 2000). "Italian GP". Formula 1 2000: World Championship Yearbook: The Complete Record of the Grand Prix Season. Stillwater, Minnesota: Voyageur Press. p. 195. ISBN 0-89658-499-2.

- "2000 – Round 14 – Italy: Monza". Formula1.com. Formula1.com Limited. 10 September 2000. Archived from the original on 3 June 2001. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- "Teams go softer on tyre choices". F1Racing.net. 10 September 2000. Archived from the original on 10 January 2005. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- "Grand Prix Results: Italian GP 2000". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- Gardner, John (10 September 2000). "Italian GP: Schumacher Wins Monza". Speedvision. Archived from the original on 17 October 2000. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- "Italian GP race analysis". Autosport. Motorsport Network. 12 September 2000. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- "Schumacher wins at Monza". F1Racing.net. 10 September 2000. Archived from the original on 10 January 2005. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- "Schumacher tolls championship bell". Crash. 10 September 2000. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- "Italian Grand Prix: race report". Autosport. Motorsport Network. 10 September 2000. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- Nidetz, Stephen (11 September 2000). "Official Killed In Italian Race". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- "Zonta scores stunning point for BAR". F1Racing.net. 10 September 2000. Archived from the original on 10 January 2005. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- "Fire Marshall Dies at Monza". Autosport. Motorsport Network. Reuters. 10 September 2000. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- "Carambola maledetta, muore un volontario" [Carambola cursed, Death of a volunteer]. Corriere Della Sera. 11 September 2000. p. 36. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- "Lap-by-Lap: Grand Prix of Italy". Gale Force F1. 10 September 2000. Archived from the original on 4 January 2005. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- Henry, Alan (2009). Jenson Button: A World Champion's Story. Sparkford, England: Haynes Publishing. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-84425-936-6.

- Knutson, Dan (10 September 2000). "Race Report: Italian Grand Prix: M. Schumacher Closes To Within Two Points Of Hakkinen After Emotional Victory". USGP Indy. Archived from the original on 26 January 2001. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- "Post-Race Press Conference – Italian GP". Atlas F1. Haymarket Publications. 10 September 2000. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- "Schumacher reveals surprise at reaction to his tears at Monza". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. 21 September 2000. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- Gardner, John (10 September 2000). "Italian GP: Post-Race Spin". Speedvision. Daily F1. Archived from the original on 3 December 2000. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- "Button caught out by Schumacher tactics". Autosport. Motorsport Network. 10 September 2000. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- Cooper, Adam (13 September 2000). "Alex Wurz Q&A". Autosport. Motorsport Network. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- "Barrichello claims Frentzen must be banned for 10 races". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. 10 September 2000. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- "Frentzen says Monza Accident Not his Fault". Atlas F1. Haymarket Publishing. 12 September 2000. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- "FIA explain no Red Flag". Gale Force F1. 14 September 2000. Archived from the original on 18 February 2007. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- "Jordan Praises Car Safety After First Lap Shunt". Atlas F1. Haymarket Publications. 10 September 2000. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- "Mosley promises action after Monza tragedy". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. 12 September 2000. Archived from the original on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- "Mosley says nobody is to blame". Formula1.com. Formula1.com Limited. 12 September 2000. Archived from the original on 3 June 2001. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- "Laffite Wants Warning System to Protect Marshalls". Atlas F1. Haymarket Publications. 10 September 2000. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- Ianeri, Paolo (15 September 2000). "L' omaggio della F.1 a Paolo" [The homage of F1 to Paolo]. La Gazzetta dello Sport (in Italian). Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- "La tragedia nella festa Muore addetto alla pista" [The tragedy in the party The track attendant dies]. la Repubblica (in Italian). 10 September 2000. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- "Investigators release GP crash cars". News24. Naspers. 12 September 2000. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- "Formula One says good-bye to Paulo". GPUpdate. 15 September 2000. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- "Italian police impound crashed cars at Monza". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. 10 September 2000. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- Allsop, Derick (11 September 2000). "Tragedy mars Ferrari's homecoming". The Independent. Independent Print Limited. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- "Jordan Cars Released from Monza". Atlas F1. Haymarket Publications. 12 September 2000. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- "Gislimberti: Legal investigation dropped". Formula1.com. Formula1.com Limited. 20 June 2001. Archived from the original on 25 June 2001. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- "FIA to Improve Safety after Monza Death". Atlas F1. Haymarket Publications. 17 September 2000. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- "2000 Italian Grand Prix". Formula1.com. Formula1.com Limited. Archived from the original on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- "Italy 2000 – Championship • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Archived from the original on 30 August 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2019.