Aciclovir

Aciclovir (ACV), also known as acyclovir,[3] is an antiviral medication.[4] It is primarily used for the treatment of herpes simplex virus infections, chickenpox, and shingles.[5] Other uses include prevention of cytomegalovirus infections following transplant and severe complications of Epstein–Barr virus infection.[5][6] It can be taken by mouth, applied as a cream, or injected.[5]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /eɪˈsaɪkloʊvɪər/ |

| Trade names | Zovirax, others[1] |

| Other names | Acycloguanosine, acyclovir (BAN UK), acyclovir (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a681045 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Intravenous, by mouth, topical, eye ointment |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 15–20% (by mouth)[2] |

| Protein binding | 9–33%[2] |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 2–4 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney (62–90% as unchanged drug) |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| PubChem SID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.056.059 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C8H11N5O3 |

| Molar mass | 225.208 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 256.5 °C (493.7 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include nausea and diarrhea.[5] Potentially serious side effects include kidney problems and low platelets.[5] Greater care is recommended in those with poor liver or kidney function.[5] It is generally considered safe for use in pregnancy with no harm having been observed.[5][7] It appears to be safe during breastfeeding.[8][9] Aciclovir is a nucleoside analogue that mimics guanosine.[5] It works by decreasing the production of the virus's DNA.[5]

Aciclovir was patented in 1974, and approved for medical use in 1981.[10] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[11][12] It is available as a generic medication and is marketed under many brand names worldwide.[1] In 2019, it was the 157th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 3 million prescriptions.[13][14]

Medical use

Aciclovir is used for the treatment of herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella zoster virus infections, including:[2][15][16]

- Genital herpes simplex (treatment and prevention)

- Neonatal herpes simplex

- Herpes simplex labialis (cold sores)

- Shingles

- Acute chickenpox in immunocompromised patients

- Herpes simplex encephalitis

- Acute mucocutaneous HSV infections in immunocompromised patients

- Herpes of the eye and herpes simplex blepharitis (a chronic (long-term) form of herpes eye infection)

- Prevention of herpes viruses in immunocompromised people (such as people undergoing cancer chemotherapy)[17]

Its effectiveness in treating Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infections is less clear.[5] It has not been found to be useful for infectious mononucleosis due to EBV.[18] Valaciclovir and acyclovir act by inhibiting viral DNA replication, but as of 2016 there was little evidence that they are effective against Epstein–Barr virus, they are expensive, they risk causing resistance to antiviral agents, and (in 1% to 10% of cases) can cause unpleasant side effects.[19]

Aciclovir taken by mouth does not appear to decrease the risk of pain after shingles.[20] In those with herpes of the eye, aciclovir may be more effective and safer than idoxuridine.[21] It is not clear if aciclovir eye drops are more effective than brivudine eye drops.[21]

Intravenous aciclovir is effective to treat severe medical conditions caused by different species of the herpes virus family, including severe localized infections of herpes virus, severe genital herpes, chickenpox and herpesviral encephalitis. It is also effective in systemic or traumatic herpes infections, eczema herpeticum and herpesviral meningitis. Reviews of research dating from the 1980s show there is some effect in reducing the number and duration of lesions if aciclovir is applied at an early stage of an outbreak.[22] Research shows effectiveness of topical aciclovir in both the early and late stages of the outbreak as well as improving methodologically and in terms of statistical certainty from previous studies.[23] Aciclovir trials show that this agent has no role in preventing HIV transmission, but it can help slow HIV disease progression in people not taking anti-retroviral therapy (ART). This finding emphasizes the importance of testing simple, inexpensive non-ART strategies, such as aciclovir and cotrimoxazole, in people with HIV.[24]

Pregnancy

Classified as a Category B drug,[25] the CDC and others have declared that during severe recurrent or first episodes of genital herpes, aciclovir may be used.[26] For severe HSV infections (especially disseminated HSV), IV aciclovir may also be used.[27] Studies in mice, rabbits and rats (with doses more than 10 times the equivalent of that used in humans) given during organogenesis have failed to demonstrate birth defects.[28] Studies in rats in which they were given the equivalent to 63 times the standard steady-state humans concentrations of the drug[Note 1] on day 10 of gestation showed head and tail anomalies.[28]

Aciclovir is recommended by the CDC for treatment of varicella during pregnancy, especially during the second and third trimesters.[29]

Aciclovir is excreted in the breast milk, therefore it is recommended that caution should be used in breast-feeding women. It has been shown in limited test studies that the nursing infant is exposed to approximately 0.3 mg/kg/day following oral administration of aciclovir to the mother. If nursing mothers have herpetic lesions near or on the breast, breast-feeding should be avoided.[25][30]

Adverse effects

Systemic therapy

Common adverse drug reactions (≥1% of patients) associated with systemic aciclovir therapy (oral or IV) include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, encephalopathy (with IV use only), injection site reactions (with IV use only) and headache. In high doses, hallucinations have been reported. Infrequent adverse effects (0.1–1% of patients) include agitation, vertigo, confusion, dizziness, oedema, arthralgia, sore throat, constipation, abdominal pain, hair loss, rash and weakness. Rare adverse effects (<0.1% of patients) include coma, seizures, neutropenia, leukopenia, crystalluria, anorexia, fatigue, hepatitis, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and anaphylaxis.[15]

Intravenous aciclovir may cause reversible nephrotoxicity in up to 5% to 10% of patients because of precipitation of aciclovir crystals in the kidney. Aciclovir crystalline nephropathy is more common when aciclovir is given as a rapid infusion and in patients with dehydration and preexisting renal impairment. Adequate hydration, a slower rate of infusion, and dosing based on renal function may reduce this risk.[31][32][33]

The aciclovir metabolite 9-Carboxymethoxymethylguanine (9-CMMG) has been shown to play a role in neurological adverse events, particularly in older people and those with reduced renal function.[34][35][36]

Topical therapy

Aciclovir topical cream is commonly associated (≥1% of patients) with: dry or flaking skin or transient stinging/burning sensations. Infrequent adverse effects include erythema or itch.[15] When applied to the eye, aciclovir is commonly associated (≥1% of patients) with transient mild stinging. Infrequently (0.1–1% of patients), ophthalmic aciclovir is associated with superficial punctate keratitis or allergic reactions.[15]

Drug interactions

Ketoconazole: In-vitro replication studies have found a synergistic, dose-dependent antiviral activity against HSV-1 and HSV-2 when given with aciclovir. However, this effect has not been clinically established and more studies need to be done to evaluate the true potential of this synergy.[37]

Probenecid: Reports of increased half life of aciclovir, as well as decreased urinary excretion and renal clearance have been shown in studies where probenecid is given simultaneously with aciclovir.[25]

Interferon: Synergistic effects when administered with aciclovir and caution should be taken when administering aciclovir to patients receiving IV interferon.[38]

Zidovudine: Although administered often with aciclovir in HIV patients, neurotoxicity has been reported in at least one patient who presented with extreme drowsiness and lethargy 30–60 days after receiving IV aciclovir; symptoms resolved when aciclovir was discontinued.[39]

Detection in biological fluids

Aciclovir may be quantitated in plasma or serum to monitor for drug accumulation in patients with renal dysfunction or to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in acute overdose victims.[40]

Mechanism of action

Aciclovir is converted by viral thymidine kinase to aciclovir monophosphate, which is then converted by host cell kinases to aciclovir triphosphate (ACV-TP, also known as aciclo-GTP).[28] ACV-TP is a very potent inhibitor of viral DNA replication. ACV-TP competitively inhibits and inactivates the viral DNA polymerase.[41] Its monophosphate form also incorporates into the viral DNA, resulting in chain termination.[28][42][43]

Resistance

Resistance to aciclovir is rare in people with healthy immune systems, but is more common (up to 10%) in people with immunodeficiencies on chronic antiviral prophylaxis (transplant recipients, people with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome due to HIV infection). Mechanisms of resistance in HSV include deficient viral thymidine kinase; and mutations to viral thymidine kinase or DNA polymerase, altering substrate sensitivity.[44][45]

Microbiology

Aciclovir is active against most species in the herpesvirus family. In descending order of activity:[46][47]

- Herpes simplex virus type I (HSV-1)

- Herpes simplex virus type II (HSV-2)

- Varicella zoster virus (VZV)

- Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)

- Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) – least activity

Pharmacokinetics

Aciclovir is poorly water-soluble and has poor oral bioavailability (15–30%), hence intravenous administration is necessary if high concentrations are required. When orally administered, peak plasma concentration occurs after 1–2 hours. According to the Biopharmaceutical Classification System (BCS), aciclovir falls under the BCS Class III drug i.e. soluble with low intestinal permeability.[48] Aciclovir has a high distribution rate; protein binding is reported to range from 9 to 33%.[49] The elimination half-life (t1/2) of aciclovir depends according to age group; neonates have a t1/2 of 4 hours, children 1–12 years have a t1/2 of 2–3 hours whereas adults have a t1/2 of 3 hours.[2]

Chemistry

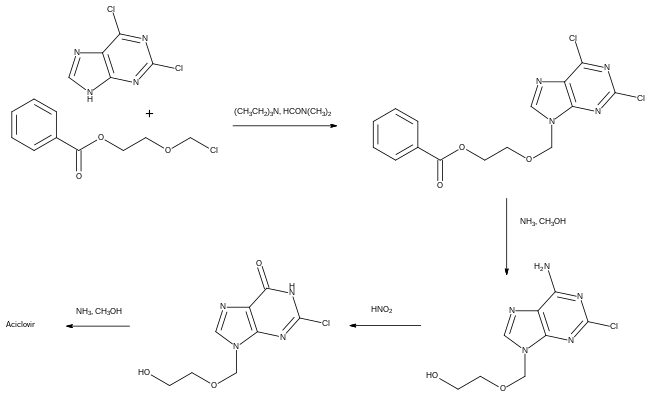

Details of the synthesis of aciclovir were first published by scientists from the University at Buffalo.[50]

In the first step shown, 2,6-dichloropurine was alkylated with 1-benzoyloxy-2-chloromethoxyethane. The chlorine group at the 6-position of the heterocyclic ring is more reactive than the chlorine at the 2-position, hence it can be selectively replaced by an amino group, which was then converted to an amide using nitrous acid. Finally, the remaining chlorine was replaced by the amino group of aciclovir using ammonia in methanol.[51] This synthesis and other methods for preparing the compound have been reviewed.[52]

History

Aciclovir was seen as the start of a new era in antiviral therapy, as it is extremely selective and low in cytotoxicity.[4] Since discovery in mid 1970s, it has been used as an effective drug for the treatment of infections caused by most known species of the herpesvirus family, including herpes simplex and varicella zoster viruses. Nucleosides isolated from a Caribbean sponge, Cryptotethya crypta, were the basis for the synthesis of aciclovir.[53][54][55] It was codiscovered by Howard Schaeffer following his work with Robert Vince, S. Bittner and S. Gurwara on the adenosine analog acycloadenosine which showed promising antiviral activity.[50] Later, Schaeffer joined Burroughs Wellcome and continued the development of aciclovir with pharmacologist Gertrude B. Elion.[56] A U.S. patent on aciclovir listing Schaeffer as inventor was issued in 1979.[57] Vince later invented abacavir, an nRTI drug for HIV patients.[58] Elion was awarded the 1988 Nobel Prize in Medicine, partly for the development of aciclovir.

A related prodrug form, valaciclovir came into medical use in 1995. It is converted to aciclovir in the body after absorption.[59]

In 2009, acyclovir in combination with hydrocortisone cream, marketed as Xerese, was approved in the United States for the early treatment of recurrent herpes labialis (cold sores) to reduce the likelihood of ulcerative cold sores and to shorten the lesion healing time in adults and children (six years of age and older).[60][61]

Society and culture

Names

Aciclovir is the international nonproprietary name (INN) and British Approved Name (BAN) while acyclovir is the United States Adopted Name (USAN) and former British Approved Name.

It was originally marketed as Zovirax; patents expired in the 1990s and since then it is generic and is marketed under many brand names worldwide.[1]

Notes

- Subject to the same conditions as before

References

- "Aciclovir". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "Zovirax (acyclovir) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- Kevin, E. Shelton. "The Aciclovir" (in German). Kevin. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- de Clercq, Erik; Field, Hugh J (5 October 2005). "Antiviral prodrugs – the development of successful prodrug strategies for antiviral chemotherapy". British Journal of Pharmacology. Vol. 147, no. 1. Wiley-Blackwell (published January 2006). pp. 1–11. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706446. PMC 1615839. PMID 16284630.

- "Acyclovir". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2015-01-05. Retrieved Jan 1, 2015.

- Rafailidis PI, Mavros MN, Kapaskelis A, Falagas ME (2010). "Antiviral treatment for severe EBV infections in apparently immunocompetent patients". Journal of Clinical Virology. 49 (3): 151–7. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2010.07.008. PMID 20739216.

- "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 59. ISBN 9781284057560.

- "Acyclovir use while Breastfeeding". Mar 10, 2015. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

Even with the highest maternal dosages, the dosage of acyclovir in milk is only about 1% of a typical infant dosage and would not be expected to cause any adverse effects in breastfed infants

- Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 504. ISBN 9783527607495.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- "The Top 300 of 2019". ClinCalc. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- "Acyclovir - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65 ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- Elad S, Zadik Y, Hewson I, et al. (August 2010). "A systematic review of viral infections associated with oral involvement in cancer patients: a spotlight on Herpesviridea". Support Care Cancer. 18 (8): 993–1006. doi:10.1007/s00520-010-0900-3. PMID 20544224. S2CID 2969472.

- Gershburg, E; Pagano, JS (August 2005). "Epstein-Barr virus infections: prospects for treatment". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 56 (2): 277–81. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.320.6721. doi:10.1093/jac/dki240. PMID 16006448.

- De Paor M, O'Brien K, Smith SM (2016). "Antiviral agents for infectious mononucleosis (glandular fever)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (12): CD011487. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011487.pub2. PMC 6463965. PMID 27933614.

- Chen, N; Li, Q; Yang, J; Zhou, M; Zhou, D; He, L (Feb 6, 2014). "Antiviral treatment for preventing postherpetic neuralgia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (2): CD006866. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006866.pub3. PMID 24500927.

- Wilhelmus, Kirk R. (2015-01-09). "Antiviral treatment and other therapeutic interventions for herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD002898. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002898.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 4443501. PMID 25879115.

- Graham Worrall (6 Jan 1996). "Acyclovir in recurrent herpes labialis". BMJ. 312 (7022): 6. doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7022.6. PMC 2349724. PMID 8555890. Archived from the original on 2007-05-15. – Editorial

- Spruance SL, Nett R, Marbury T, Wolff R, Johnson J, Spaulding T (2002). "Acyclovir cream for treatment of herpes simplex labialis: results of two randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, multicenter clinical trials". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46 (7): 2238–43. doi:10.1128/aac.46.7.2238-2243.2002. PMC 127288. PMID 12069980.

- Mascolinli, M; Kort, R (June 2010). "5th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention: summary of key research and implications for policy and practice - biomedical prevention". Journal of the International AIDS Society. 13 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1): S4. doi:10.1186/1758-2652-13-S1-S4. PMC 2880255. PMID 20519025.

- FDA and GSK. Acyclovir label Archived 2017-09-08 at the Wayback Machine Last revised 2005. Index page here

- "Drugs for non-HIV viral infections". Treatment Guidelines from the Medical Letter. 3 (32): 23–32. 2005. PMID 15767977.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treating opportunistic infections among HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association/Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004; 53(RR-15):1-112. [Fulltext MMWR]

- "PRODUCT INFORMATION NAME OF THE DRUG OZVIR TABLETS" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Ranbaxy Australia Pty Ltd. 26 August 2011. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 9th ed. Public Health Foundation; 2006 Jan:171-92

- Gartner LM, Morton J, Lawrence RA, et al., "Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk," Pediatrics, 2005, 115(2):496-506

- Razonable, RR (October 2011). "Antiviral drugs for viruses other than human immunodeficiency virus". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 86 (10): 1009–26. doi:10.4065/mcp.2011.0309. PMC 3184032. PMID 21964179.

- Brigden D, Rosling AE, Woods NC (July 1982). "Renal function after acyclovir intravenous injection". The American Journal of Medicine. 73 (1A): 182–5. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(82)90087-0. PMID 6285711.

- Sawyer MH, Webb DE, Balow JE, Straus SE (June 1988). "Acyclovir-induced renal failure. Clinical course and histology". The American Journal of Medicine. 84 (6): 1067–71. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(88)90313-0. PMID 3376977.

- Helldén, Anders; Odar-Cederlöf, Ingegerd; Diener, Per; Barkholt, Lisbeth; Medin, Charlotte; Svensson, Jan-Olof; Säwe, Juliette; Ståhle, Lars (2003). "High serum concentrations of the acyclovir main metabolite 9-carboxymethoxymethylguanine in renal failure patients with acyclovir-related neuropsychiatric side effects: an observational study". Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 18 (6): 1135–1141. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfg119. ISSN 0931-0509. PMID 12748346.

- Berry, L.; Venkatesan, P. (December 2014). "Aciclovir-induced neurotoxicity: Utility of CSF and serum CMMG levels in diagnosis". Journal of Clinical Virology. 61 (4): 608–610. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2014.09.001. PMID 25440915.

- Chowdhury, Mohammed Andaleeb; Derar, Nada; Hasan, Syed; Hinch, Bryan; Ratnam, Shoba; Assaly, Ragheb (2016). "Acyclovir-Induced Neurotoxicity: A Case Report and Review of Literature". American Journal of Therapeutics. 23 (3): e941–e943. doi:10.1097/MJT.0000000000000093. ISSN 1075-2765. PMID 24942005. S2CID 32983100.

- Pottage Jr, J. C.; Kessler, H. A.; Goodrich, J. M.; Chase, R; Benson, C. A.; Kapell, K; Levin, S (1986). "In vitro activity of ketoconazole against herpes simplex virus". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 30 (2): 215–9. doi:10.1128/aac.30.2.215. PMC 180521. PMID 3021048.

- GlaxoSmithKline. Zovirax® (acyclovir sodium) for injection prescribing information. Research Triangle Park, NC; 2003 Nov

- Bach, M. C. (1987). "Possible drug interaction during therapy with azidothymidine and acyclovir for AIDS". New England Journal of Medicine. 316 (9): 547–548. doi:10.1056/NEJM198702263160912. PMID 3468354.

- Baselt, RC (2008). Disposition of toxic drugs and chemicals in man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 29–31. ISBN 9780962652370.

- "VALTREX (valacyclovir hydrochloride) Caplets -GSKSource". gsksource.com. Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- "Acyclovir (acyclovir) Capsule Acyclovir (acyclovir) Tablet [Genpharm Inc.]". DailyMed. Genpharm Inc. November 2006. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- "Aciclovir Tablets BP 400mg - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Actavis UK Ltd. 20 August 2012. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- Sweetman, S, ed. (7 August 2013). "Aciclovir". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- Piret J, Boivin G (2011). "Resistance of herpes simplex viruses to nucleoside analogues: mechanisms, prevalence, and management". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55 (2): 459–72. doi:10.1128/AAC.00615-10. PMC 3028810. PMID 21078929.

- O'Brien, JJ; Campoli-Richards, DM (1989). "Acyclovir. An updated review of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy". Drugs. 37 (3): 233–309. doi:10.2165/00003495-198937030-00002. PMID 2653790. S2CID 240858022.

- Wagstaff, AJ; Faulds, D; Goa, KL (January 1994). "Aciclovir. A reappraisal of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy". Drugs. 47 (1): 153–205. doi:10.2165/00003495-199447010-00009. PMID 7510619.

- Karmoker, J. R.; Hasan, I.; Ahmed, N.; Saifuddin, M.; Reza, M. S. (2019). "Development and Optimization of Acyclovir Loaded Mucoadhesive Microspheres by Box -Behnken Design". Dhaka University Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 18 (1): 1–12. doi:10.3329/dujps.v18i1.41421.

- Aciclovir Tablets BP 400mg – Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) – (eMC) Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Schaffer, Howard; Robert Vince; S. Bittner; S. Gurwara (1971). "Novel substrate of adenosine deaminase". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 14 (4): 367–369. doi:10.1021/jm00286a024. PMID 5553754.

- US patent 4199574, Schaeffer, H.J., "Methods and compositions for treating viral infections and guanine acyclic nucleosides", published 1980-04-22, assigned to Burroughs Wellcome

- Vardanyan, Ruben; Hruby, Victor (2016). "34: Antiviral Drugs". Synthesis of Best-Seller Drugs. pp. 706–708. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-411492-0.00034-1. ISBN 9780124114920. S2CID 75449475.

- Garrison, Tom (1999). Oceanography: An Invitation to Marine Science, 3rd ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company. p. 471.

- Sepčić, K. (2000). "Bioactive Alkylpyridinium Compounds from Marine Sponges". Toxin Reviews. 19 (2): 139–160. doi:10.1081/TXR-100100318. S2CID 84041855.

- Laport, M. S.; Santos, O. C.; Muricy, G (2009). "Marine sponges: Potential sources of new antimicrobial drugs". Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. 10 (1): 86–105. doi:10.2174/138920109787048625. PMID 19149592.

- Elion, Gertrude; Furman PA; Fyfe, James A.; De Miranda, Paulo; Beauchamp, Lilia; Schaeffer, Howard J. (1977). "Selectivity of action of an antiherpetic agent, 9-(2-hydroxyethoxymethyl)guanine". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 74 (12): 5716–5720. Bibcode:1977PNAS...74.5716E. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.12.5716. PMC 431864. PMID 202961.

- US 4146715

- Vince R (2008). "A brief history of the development of Ziagen". Chemtracts. 21: 127–134.

- "Valacyclovir Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- "Drug Approval Package: Acyclovir and Hydrocortisone NDA #022436". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 13 December 2019. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Xerese- acyclovir and hydrocortisone cream". DailyMed. 12 December 2019. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

Further reading

- Hazra, S; Konrad, M; Lavie, A (2010). "The sugar ring of the nucleoside is required for productive substrate positioning in the active site of human deoxycytidine kinase (dCK): Implications for the development of dCK-activated acyclic guanine analogues". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 53 (15): 5792–800. doi:10.1021/jm1005379. PMC 2936711. PMID 20684612.

- Harvey Stewart C. in Remington's Pharmaceutical Sciences 18th edition: (ed. Gennard, Alfonso R.) Mack Publishing Company, 1990. ISBN 0-912734-04-3.

- Huovinen P., Valtonen V. in Kliininen Farmakologia (ed. Neuvonen et al.). Kandidaattikustannus Oy, 1994. ISBN 951-8951-09-8.

- Périgaud C.; Gosselin G.; Imbach J.-L. (1992). "Nucleoside analogues as chemotherapeutic agents: a review". Nucleosides and Nucleotides. 11 (2–4): 903–945. doi:10.1080/07328319208021748.

- Rang H.P., Dale M.M., Ritter J.M.: Pharmacology, 3rd edition. Pearson Professional Ltd, 1995. 2003 (5th) edition ISBN 0-443-07145-4; 2001 (4th) edition ISBN 0-443-06574-8; 1990 edition ISBN 0-443-03407-9.

External links

- "Acyclovir". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.