Lion

The lion (Panthera leo) is a large cat of the genus Panthera native to Africa and India. It has a muscular, broad-chested body, short, rounded head, round ears, and a hairy tuft at the end of its tail. It is sexually dimorphic; adult male lions are larger than females and have a prominent mane. It is a social species, forming groups called prides. A lion's pride consists of a few adult males, related females, and cubs. Groups of female lions usually hunt together, preying mostly on large ungulates. The lion is an apex and keystone predator; although some lions scavenge when opportunities occur and have been known to hunt humans, the species typically does not actively seek out and prey on humans.

| Lion Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male lion in Okonjima, Namibia | |

| |

| Female (lioness) in Okonjima | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | P. leo[2] |

| Binomial name | |

| Panthera leo[2] | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

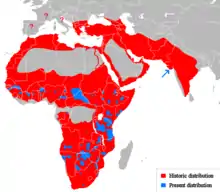

| Historical and present distribution of the lion in Africa, Asia and Europe | |

The lion inhabits grasslands, savannas and shrublands. It is usually more diurnal than other wild cats, but when persecuted, it adapts to being active at night and at twilight. During the Neolithic period, the lion ranged throughout Africa and Eurasia from Southeast Europe to India, but it has been reduced to fragmented populations in sub-Saharan Africa and one population in western India. It has been listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List since 1996 because populations in African countries have declined by about 43% since the early 1990s. Lion populations are untenable outside designated protected areas. Although the cause of the decline is not fully understood, habitat loss and conflicts with humans are the greatest causes for concern.

One of the most widely recognised animal symbols in human culture, the lion has been extensively depicted in sculptures and paintings, on national flags, and in contemporary films and literature. Lions have been kept in menageries since the time of the Roman Empire and have been a key species sought for exhibition in zoological gardens across the world since the late 18th century. Cultural depictions of lions were prominent in Ancient Egypt, and depictions have occurred in virtually all ancient and medieval cultures in the lion's historic and current range.

Etymology

The English word lion is derived via Anglo-Norman liun from Latin leōnem (nominative: leō), which in turn was a borrowing from Ancient Greek λέων léōn. The Hebrew word לָבִיא lavi may also be related.[4] The generic name Panthera is traceable to the classical Latin word 'panthēra' and the ancient Greek word πάνθηρ 'panther'.[5]

Taxonomy

Felis leo was the scientific name used by Carl Linnaeus in 1758, who described the lion in his work Systema Naturae.[3] The genus name Panthera was coined by Lorenz Oken in 1816.[10] Between the mid-18th and mid-20th centuries, 26 lion specimens were described and proposed as subspecies, of which 11 were recognised as valid in 2005.[2] They were distinguished mostly by the size and colour of their manes and skins.[11]

Subspecies

In the 19th and 20th centuries, several lion type specimens were described and proposed as subspecies, with about a dozen recognised as valid taxa until 2017.[2] Between 2008 and 2016, IUCN Red List assessors used only two subspecific names: P. l. leo for African lion populations, and P. l. persica for the Asiatic lion population.[1][12][13] In 2017, the Cat Classification Task Force of the Cat Specialist Group revised lion taxonomy, and recognises two subspecies based on results of several phylogeographic studies on lion evolution, namely:[14]

- P. l. leo (Linnaeus, 1758) − the nominate lion subspecies includes the Asiatic lion, the regionally extinct Barbary lion, and lion populations in West and northern parts of Central Africa.[14] Synonyms include P. l. persica (Meyer, 1826), P. l. senegalensis (Meyer, 1826), P. l. kamptzi (Matschie, 1900), and P. l. azandica (Allen, 1924).[2] Multiple authors referred to it as 'northern lion' and 'northern subspecies'.[15][16]

- P. l. melanochaita (Smith, 1842) − includes the extinct Cape lion and lion populations in East and Southern African regions.[14] Synonyms include P. l. somaliensis (Noack 1891), P. l. massaica (Neumann, 1900), P. l. sabakiensis (Lönnberg, 1910), P. l. bleyenberghi (Lönnberg, 1914), P. l. roosevelti (Heller, 1914), P. l. nyanzae (Heller, 1914), P. l. hollisteri (Allen, 1924), P. l. krugeri (Roberts, 1929), P. l. vernayi (Roberts, 1948), and P. l. webbiensis (Zukowsky, 1964).[2][11] It has been referred to as 'southern subspecies' and 'southern lion'.[16]

However, there seems to be some degree of overlap between both groups in northern Central Africa. DNA analysis from a more recent study indicates, that Central African lions are derived from both northern and southern lions, as they cluster with P. leo leo in mtDNA-based phylogenies whereas their genomic DNA indicates a closer relationship with P. leo melanochaita.[17]

Lion samples from some parts of the Ethiopian Highlands cluster genetically with those from Cameroon and Chad, while lions from other areas of Ethiopia cluster with samples from East Africa. Researchers therefore assume Ethiopia is a contact zone between the two subspecies.[18] Genome-wide data of a wild-born historical lion sample from Sudan showed that it clustered with P. l. leo in mtDNA-based phylogenies, but with a high affinity to P. l. melanochaita. This result suggested that the taxonomic position of lions in Central Africa may require revision.[19]

Fossil records

Other lion subspecies or sister species to the modern lion existed in prehistoric times:[20]

- P. l. sinhaleyus was a fossil carnassial excavated in Sri Lanka, which was attributed to a lion. It is thought to have become extinct around 39,000 years ago.[21]

- P. leo fossilis was larger than the modern lion and lived in the Middle Pleistocene. Bone fragments were excavated in caves in the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy and Czech Republic.[22][23]

- P. spelaea, or the cave lion, lived in Eurasia and Beringia during the Late Pleistocene. It became extinct due to climate warming or human expansion latest by 11,900 years ago.[24] Bone fragments excavated in European, North Asian, Canadian and Alaskan caves indicate that it ranged from Europe across Siberia into western Alaska.[25] It likely derived from P. fossilis,[26] and was genetically isolated and highly distinct from the modern lion in Africa and Eurasia.[27][26] It is depicted in Paleolithic cave paintings, ivory carvings, and clay busts.[28]

- P. atrox, or the American lion, ranged in the Americas from Canada to possibly Patagonia.[29] It arose when a cave lion population in Beringia became isolated south of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet about 370,000 years ago.[30][31] A fossil from Edmonton dates to 11,355 ± 55 years ago.[32]

Evolution

blue Panthera atrox

green Panthera leo

Maximal range of the modern lion

and its prehistoric relatives

in the late Pleistocene

The Panthera lineage is estimated to have genetically diverged from the common ancestor of the Felidae around 9.32 to 4.47 million years ago to 11.75 to 0.97 million years ago,[6][33][34] and the geographic origin of the genus is most likely northern Central Asia.[35] Results of analyses differ in the phylogenetic relationship of the lion; it was thought to form a sister group with the jaguar (P. onca) that diverged 3.46 to 1.22 million years ago,[6] but also with the leopard (P. pardus) that diverged 3.1 to 1.95 million years ago[8][9] to 4.32 to 0.02 million years ago. Hybridisation between lion and snow leopard (P. uncia) ancestors possibly continued until about 2.1 million years ago.[34] The lion-leopard clade was distributed in the Asian and African Palearctic since at least the early Pliocene.[35] The earliest fossils recognisable as lions were found at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania and are estimated to be up to 2 million years old.[33]

Estimates for the divergence time of the modern and cave lion lineages range from 529,000 to 392,000 years ago based on mutation rate per generation time of the modern lion. There is no evidence for gene flow between the two lineages, indicating that they did not share the same geographic area.[19] The Eurasian and American cave lions became extinct at the end of the last glacial period without mitochondrial descendants on other continents.[27][36][37] The modern lion was probably widely distributed in Africa during the Middle Pleistocene and started to diverge in sub-Saharan Africa during the Late Pleistocene. Lion populations in East and Southern Africa became separated from populations in West and North Africa when the equatorial rainforest expanded 183,500 to 81,800 years ago.[38] They shared a common ancestor probably between 98,000 and 52,000 years ago.[19] Due to the expansion of the Sahara between 83,100 and 26,600 years ago, lion populations in West and North Africa became separated. As the rainforest decreased and thus gave rise to more open habitats, lions moved from West to Central Africa. Lions from North Africa dispersed to southern Europe and Asia between 38,800 and 8,300 years ago.[38]

Extinction of lions in southern Europe, North Africa and the Middle East interrupted gene flow between lion populations in Asia and Africa. Genetic evidence revealed numerous mutations in lion samples from East and Southern Africa, which indicates that this group has a longer evolutionary history than genetically less diverse lion samples from Asia and West and Central Africa.[39] A whole genome-wide sequence of lion samples showed that samples from West Africa shared alleles with samples from Southern Africa, and samples from Central Africa shared alleles with samples from Asia. This phenomenon indicates that Central Africa was a melting pot of lion populations after they had become isolated, possibly migrating through corridors in the Nile Basin during the early Holocene.[19]

Hybrids

In zoos, lions have been bred with tigers to create hybrids for the curiosity of visitors or for scientific purpose.[40][41] The liger is bigger than a lion and a tiger, whereas most tigons are relatively small compared to their parents because of reciprocal gene effects.[42][43] The leopon is a hybrid between a lion and leopard.[44]

Description

The lion is a muscular, broad-chested cat with a short, rounded head, a reduced neck and round ears. Its fur varies in colour from light buff to silvery grey, yellowish red and dark brown. The colours of the underparts are generally lighter. A new-born lion has dark spots, which fade as the cub reaches adulthood, although faint spots often may still be seen on the legs and underparts. The lion is the only member of the cat family that displays obvious sexual dimorphism. Males have broader heads and a prominent mane that grows downwards and backwards covering most of the head, neck, shoulders, and chest. The mane is typically brownish and tinged with yellow, rust and black hairs.[45][46]

The tail of all lions ends in a dark, hairy tuft that in some lions conceals an approximately 5 mm (0.20 in)-long, hard "spine" or "spur" that is formed from the final, fused sections of tail bone. The functions of the spur are unknown. The tuft is absent at birth and develops at around 5+1⁄2 months of age. It is readily identifiable by the age of seven months.[47]

Of the living felid species, the lion is rivaled only by the tiger in length, weight, and height at the shoulder.[48] Its skull is very similar to that of the tiger, although the frontal region is usually more depressed and flattened, and has a slightly shorter postorbital region and broader nasal openings than those of the tiger. Due to the amount of skull variation in the two species, usually only the structure of the lower jaw can be used as a reliable indicator of species.[49][50]

Skeletal muscles of the lion make up 58.8% of its body weight and represents the highest percentage of muscles among mammals.[51][52]

Size

The size and weight of adult lions varies across global range and habitats.[53][54][55][56] Accounts of a few individuals that were larger than average exist from Africa and India.[45][57][58][59]

| Average | Female lions | Male lions |

|---|---|---|

| Head-and-body length | 160–184 cm (63–72 in)[60] | 184–208 cm (72–82 in)[60] |

| Tail length | 72–89.5 cm (28.3–35.2 in)[60] | 82.5–93.5 cm (32.5–36.8 in)[60] |

| Weight | 118.37–143.52 kg (261.0–316.4 lb) in Southern Africa,[53] 119.5 kg (263 lb) in East Africa,[53] 110–120 kg (240–260 lb) in India[54] |

186.55–225 kg (411.3–496.0 lb) in Southern Africa,[53] 174.9 kg (386 lb) in East Africa,[53] 160–190 kg (350–420 lb) in India[54] |

Mane

_male_6y.jpg.webp)

The male lion's mane is the most recognisable feature of the species.[11] It may have evolved around 320,000–190,000 years ago.[61] It starts growing when lions are about a year old. Mane colour varies and darkens with age; research shows its colour and size are influenced by environmental factors such as average ambient temperature. Mane length apparently signals fighting success in male–male relationships; darker-maned individuals may have longer reproductive lives and higher offspring survival, although they suffer in the hottest months of the year. The presence, absence, colour and size of the mane are associated with genetic precondition, sexual maturity, climate and testosterone production; the rule of thumb is that a darker, fuller mane indicates a healthier animal. In Serengeti National Park, female lions favour males with dense, dark manes as mates. Cool ambient temperature in European and North American zoos may result in a heavier mane.[62] Asiatic lions usually have sparser manes than average African lions.[63]

Almost all male lions in Pendjari National Park are either maneless or have very short manes.[64] Maneless lions have also been reported in Senegal, in Sudan's Dinder National Park and in Tsavo East National Park, Kenya.[65] The original male white lion from Timbavati in South Africa was also maneless. The hormone testosterone has been linked to mane growth; castrated lions often have little to no mane because the removal of the gonads inhibits testosterone production.[66] Increased testosterone may be the cause of maned lionesses reported in northern Botswana.[67]

Colour variation

The white lion is a rare morph with a genetic condition called leucism which is caused by a double recessive allele. It is not albino; it has normal pigmentation in the eyes and skin. White lions have occasionally been encountered in and around Kruger National Park and the adjacent Timbavati Private Game Reserve in eastern South Africa. They were removed from the wild in the 1970s, thus decreasing the white lion gene pool. Nevertheless, 17 births have been recorded in five prides between 2007 and 2015.[68] White lions are selected for breeding in captivity.[69] They have reportedly been bred in camps in South Africa for use as trophies to be killed during canned hunts.[70]

Distribution and habitat

African lions live in scattered populations across sub-Saharan Africa. The lion prefers grassy plains and savannahs, scrub bordering rivers and open woodlands with bushes. It rarely enters closed forests. On Mount Elgon, the lion has been recorded up to an elevation of 3,600 m (11,800 ft) and close to the snow line on Mount Kenya.[45] Savannahs with an annual rainfall of 300 to 1,500 mm (12 to 59 in) make up the majority of lion habitat in Africa, estimated at 3,390,821 km2 (1,309,203 sq mi) at most, but remnant populations are also present in tropical moist forests in West Africa and montane forests in East Africa.[71] The Asiatic lion now survives only in and around Gir National Park in Gujarat, western India. Its habitat is a mixture of dry savannah forest and very dry, deciduous scrub forest.[12]

Historical range

In Africa, the range of the lion originally spanned most of the central African rainforest zone and the Sahara desert.[72] In the 1960s, it became extinct in North Africa, except in the southern part of Sudan.[73][71][74]

In southern Europe and Asia, the lion once ranged in regions where climatic conditions supported an abundance of prey.[75] In Greece, it was common as reported by Herodotus in 480 BC; it was considered rare by 300 BC and extirpated by AD 100.[45] It was present in the Caucasus until the 10th century.[50] It lived in Palestine until the Middle Ages, and in Southwest Asia until the late 19th century. By the late 19th century, it had been extirpated in most of Turkey.[76] The last live lion in Iran was sighted in 1942 about 65 km (40 mi) northwest of Dezful,[77] although the corpse of a lioness was found on the banks of the Karun river in Khūzestān Province in 1944.[78] It once ranged from Sind and Punjab in Pakistan to Bengal and the Narmada River in central India.[79]

Behaviour and ecology

Lions spend much of their time resting; they are inactive for about twenty hours per day.[80] Although lions can be active at any time, their activity generally peaks after dusk with a period of socialising, grooming and defecating. Intermittent bursts of activity continue until dawn, when hunting most often takes place. They spend an average of two hours a day walking and fifty minutes eating.[81]

Group organisation

_male_and_cub_Etosha.jpg.webp)

The lion is the most social of all wild felid species, living in groups of related individuals with their offspring. Such a group is called a "pride". Groups of male lions are called "coalitions".[82] Females form the stable social unit in a pride and do not tolerate outside females.[83] Membership changes only with the births and deaths of lionesses,[84] although some females leave and become nomadic.[85] The average pride consists of around 15 lions, including several adult females and up to four males and their cubs of both sexes. Large prides, consisting of up to 30 individuals, have been observed.[86] The sole exception to this pattern is the Tsavo lion pride that always has just one adult male.[87] Male cubs are excluded from their maternal pride when they reach maturity at around two or three years of age.[85]

Some lions are "nomads" that range widely and move around sporadically, either in pairs or alone.[82] Pairs are more frequent among related males who have been excluded from their birth pride. A lion may switch lifestyles; nomads can become residents and vice versa.[88] Interactions between prides and nomads tend to be hostile, although pride females in estrus allow nomadic males to approach them.[89] Males spend years in a nomadic phase before gaining residence in a pride.[90] A study undertaken in the Serengeti National Park revealed that nomadic coalitions gain residency at between 3.5 and 7.3 years of age.[91] In Kruger National Park, dispersing male lions move more than 25 km (16 mi) away from their natal pride in search of their own territory. Female lions stay closer to their natal pride. Therefore, female lions in an area are more closely related to each other than male lions in the same area.[92]

The area occupied by a pride is called a "pride area" whereas that occupied by a nomad is a "range".[82] Males associated with a pride tend to stay on the fringes, patrolling their territory. The reasons for the development of sociality in lionesses—the most pronounced in any cat species—are the subject of much debate. Increased hunting success appears to be an obvious reason, but this is uncertain upon examination; coordinated hunting allows for more successful predation but also ensures non-hunting members reduce per capita calorific intake. Some females, however, take a role raising cubs that may be left alone for extended periods. Members of the pride tend to regularly play the same role in hunts and hone their skills. The health of the hunters is the primary need for the survival of the pride; hunters are the first to consume the prey at the site it is taken. Other benefits include possible kin selection, sharing food within the family, protecting the young, maintaining territory, and individual insurance against injury and hunger.[57]

Both males and females defend the pride against intruders, but the male lion is better-suited for this purpose due to its stockier, more powerful build. Some individuals consistently lead the defence against intruders, while others lag behind.[93] Lions tend to assume specific roles in the pride; slower-moving individuals may provide other valuable services to the group.[94] Alternatively, there may be rewards associated with being a leader that fends off intruders; the rank of lionesses in the pride is reflected in these responses.[95] The male or males associated with the pride must defend their relationship with the pride from outside males who may attempt to usurp them.[88]

Asiatic lion prides differ in group composition. Male Asiatic lions are solitary or associate with up to three males, forming a loose pride while females associate with up to 12 other females, forming a stronger pride together with their cubs. Female and male lions associate only when mating.[96] Coalitions of males hold territory for a longer time than single lions. Males in coalitions of three or four individuals exhibit a pronounced hierarchy, in which one male dominates the others and mates more frequently.[97]

Hunting and diet

The lion is a generalist hypercarnivore and is considered to be both an apex and keystone predator due to its wide prey spectrum.[98][99] Its prey consists mainly of ungulates weighing 190–550 kg (420–1,210 lb) with a preferrence for blue wildebeest, plains zebra, African buffalo, gemsbok and giraffe. They also hunt common warthog depending on availability, despite weighing less than the preferred weight range.[100] In India, chital and sambar deer are the most common wild prey,[46][100][101] while livestock contributes significantly to lion kills outside protected areas.[102] They usually avoid fully grown adult elephants, rhinoceroses and hippopotamus and small prey like dik-dik, hyraxes, hares and monkeys.[100][103] Unusual prey include porcupines and small reptiles. Lions kill other predators but seldom consume them.[104]

Young lions first display stalking behaviour at around three months of age, although they do not participate in hunting until they are almost a year old and begin to hunt effectively when nearing the age of two.[105] Single lions are capable of bringing down zebra and wildebeest, while larger prey like buffalo and giraffe are riskier.[88] In Chobe National Park, large prides have been observed hunting African bush elephants up to around 15 years old in exceptional cases, with the victims being calves, juveniles, and even subadults.[106][107] In typical hunts, each lioness has a favoured position in the group, either stalking prey on the "wing", then attacking, or moving a smaller distance in the centre of the group and capturing prey fleeing from other lionesses. Males attached to prides do not usually participate in group hunting.[108] Some evidence suggests, however, that males are just as successful as females; they are typically solo hunters who ambush prey in small bushland.[109]

Lions are not particularly known for their stamina. For instance, a lioness's heart comprises only 0.57% of her body weight and a male's is about 0.45% of his body weight, whereas a hyena's heart comprises almost 1% of its body weight.[110] Thus, lions run quickly only in short bursts at about 48–59 km/h (30–37 mph) and need to be close to their prey before starting the attack.[111] One study in 2018 recorded a lion running at a top speed of 74.1 km/h (46.0 mph).[112] They take advantage of factors that reduce visibility; many kills take place near some form of cover or at night.[113] The lion's attack is short and powerful; they attempt to catch prey with a fast rush and final leap. They usually pull it down by the rump and kill by a strangling bite to the throat. They also kill prey by enclosing its muzzle in their jaws.[114] Male lions usually aim for the backs or hindquarters of rivals, rather than their necks.[115][116]

Lions typically consume prey at the location of the hunt but sometimes drag large prey into cover.[117] They tend to squabble over kills, particularly the males. Cubs suffer most when food is scarce but otherwise all pride members eat their fill, including old and crippled lions, which can live on leftovers.[88] Large kills are shared more widely among pride members.[118] An adult lioness requires an average of about 5 kg (11 lb) of meat per day while males require about 7 kg (15 lb).[119] Lions gorge themselves and eat up to 30 kg (66 lb) in one session.[78] If it is unable to consume all of the kill, it rests for a few hours before continuing to eat. On hot days, the pride retreats to shade with one or two males standing guard.[117] Lions defend their kills from scavengers such as vultures and hyenas.[88]

Lions scavenge on carrion when the opportunity arises, scavenging animals dead from natural causes such as disease or those that were killed by other predators. Scavenging lions keep a constant lookout for circling vultures, which indicate the death or distress of an animal.[120] Most carrion on which both hyenas and lions feed upon are killed by hyenas rather than lions.[56] Carrion is thought to provide a large part of lion diet.[121]

Predatory competition

Lions and spotted hyenas occupy a similar ecological niche and compete for prey and carrion; a review of data across several studies indicates a dietary overlap of 58.6%.[122] Lions typically ignore hyenas unless they are on a kill or are being harassed, while the latter tend to visibly react to the presence of lions with or without the presence of food. In the Ngorongoro crater, lions subsist largely on kills stolen from hyenas, causing them to increase their kill rate.[123] In Botswana's Chobe National Park, the situation is reversed as hyenas there frequently challenge lions and steal their kills, obtaining food from 63% of all lion kills.[124] When confronted on a kill, hyenas may either leave or wait patiently at a distance of 30–100 m (98–328 ft) until the lions have finished.[125] Hyenas feed alongside lions and force them off a kill. The two species attack one another even when there is no food involved for no apparent reason.[126] Lion predation can account for up to 71% of hyena deaths in Etosha National Park. Hyenas have adapted by frequently mobbing lions that enter their home ranges.[127] When the lion population in Kenya's Masai Mara National Reserve declined, the spotted hyena population increased rapidly.[128]

Lions tend to dominate cheetahs and leopards, steal their kills and kill their cubs and even adults when given the chance.[129] Cheetahs often lose their kills to lions or other predators.[130] A study in the Serengeti ecosystem revealed that lions killed at least 17 of 125 cheetah cubs born between 1987 and 1990.[131] Cheetahs avoid their competitors by hunting at different times and habitats.[132] Leopards take refuge in trees, but lionesses occasionally attempt to climb up and retrieve their kills.[133]

Lions similarly dominate African wild dogs, taking their kills and slaying pups or adult dogs. Population densities of wild dogs are low in areas where lions are more abundant.[134] However, there are a few reported cases of old and wounded lion falling prey to wild dogs.[135][136] Nile crocodiles may also kill and eat lions, evidenced by the occasional lion claw found in crocodile stomachs.[137]

Reproduction and life cycle

Most lionesses reproduce by the time they are four years of age.[138] Lions do not mate at a specific time of year and the females are polyestrous.[139] Like those of other cats, the male lion's penis has spines that point backward. During withdrawal of the penis, the spines rake the walls of the female's vagina, which may cause ovulation.[140][141] A lioness may mate with more than one male when she is in heat.[142] Generation length of the lion is about seven years.[143] The average gestation period is around 110 days;[139] the female gives birth to a litter of between one and four cubs in a secluded den, which may be a thicket, a reed-bed, a cave, or some other sheltered area, usually away from the pride. She will often hunt alone while the cubs are still helpless, staying relatively close to the den.[144] Lion cubs are born blind, their eyes opening around seven days after birth. They weigh 1.2–2.1 kg (2.6–4.6 lb) at birth and are almost helpless, beginning to crawl a day or two after birth and walking around three weeks of age.[145] To avoid a buildup of scent attracting the attention of predators, the lioness moves her cubs to a new den site several times a month, carrying them one-by-one by the nape of the neck.[144]

Usually, the mother does not integrate herself and her cubs back into the pride until the cubs are six to eight weeks old.[144] Sometimes the introduction to pride life occurs earlier, particularly if other lionesses have given birth at about the same time.[88][146] When first introduced to the rest of the pride, lion cubs lack confidence when confronted with adults other than their mother. They soon begin to immerse themselves in the pride life, however, playing among themselves or attempting to initiate play with the adults.[146] Lionesses with cubs of their own are more likely to be tolerant of another lioness's cubs than lionesses without cubs. Male tolerance of the cubs varies—one male could patiently let the cubs play with his tail or his mane, while another may snarl and bat the cubs away.[147]

Pride lionesses often synchronise their reproductive cycles and communal rearing and suckling of the young, which suckle indiscriminately from any or all of the nursing females in the pride. The synchronisation of births is advantageous because the cubs grow to being roughly the same size and have an equal chance of survival, and sucklings are not dominated by older cubs.[88][146] Weaning occurs after six or seven months. Male lions reach maturity at about three years of age and at four to five years are capable of challenging and displacing adult males associated with another pride. They begin to age and weaken at between 10 and 15 years of age at the latest.[148]

When one or more new males oust the previous males associated with a pride, the victors often kill any existing young cubs, perhaps because females do not become fertile and receptive until their cubs mature or die. Females often fiercely defend their cubs from a usurping male but are rarely successful unless a group of three or four mothers within a pride join forces against the male.[149] Cubs also die from starvation and abandonment, and predation by leopards, hyenas and wild dogs.[136][88] Up to 80% of lion cubs will die before the age of two.[150] Both male and female lions may be ousted from prides to become nomads, although most females usually remain with their birth pride. When a pride becomes too large, however, the youngest generation of female cubs may be forced to leave to find their own territory. When a new male lion takes over a pride, adolescents both male and female may be evicted.[151] Lions of both sexes may be involved in group homosexual and courtship activities. Males will also head-rub and roll around with each other before simulating sex together.[152][153]

Health and mortality

Although adult lions have no natural predators, evidence suggests most die violently from attacks by humans or other lions.[154] Lions often inflict serious injuries on members of other prides they encounter in territorial disputes or members of the home pride when fighting at a kill.[155] Crippled lions and cubs may fall victim to hyenas and leopards or be trampled by buffalo or elephants. Careless lions may be maimed when hunting prey.[156]

Ticks commonly infest the ears, neck and groin regions of the lions.[157][158] Adult forms of several tapeworm species of the genus Taenia have been isolated from lion intestines, having been ingested as larvae in antelope meat.[159] Lions in the Ngorongoro Crater were afflicted by an outbreak of stable fly (Stomoxys calcitrans) in 1962, resulting in lions becoming emaciated and covered in bloody, bare patches. Lions sought unsuccessfully to evade the biting flies by climbing trees or crawling into hyena burrows; many died or migrated and the local population dropped from 70 to 15 individuals.[160] A more recent outbreak in 2001 killed six lions.[161]

Captive lions have been infected with canine distemper virus (CDV) since at least the mid-1970s.[162] CDV is spread by domestic dogs and other carnivores; a 1994 outbreak in Serengeti National Park resulted in many lions developing neurological symptoms such as seizures. During the outbreak, several lions died from pneumonia and encephalitis.[163] Feline immunodeficiency virus and lentivirus also affect captive lions.[164][165]

Communication

When resting, lion socialisation occurs through a number of behaviours; the animal's expressive movements are highly developed. The most common peaceful, tactile gestures are head rubbing and social licking,[166] which have been compared with the role of allogrooming among primates.[167] Head rubbing—nuzzling the forehead, face and neck against another lion—appears to be a form of greeting[168] and is seen often after an animal has been apart from others or after a fight or confrontation. Males tend to rub other males, while cubs and females rub females.[169] Social licking often occurs in tandem with head rubbing; it is generally mutual and the recipient appears to express pleasure. The head and neck are the most common parts of the body licked; this behaviour may have arisen out of utility because lions cannot lick these areas themselves.[170]

Lions have an array of facial expressions and body postures that serve as visual gestures.[171] A common facial expression is the "grimace face" or flehmen response, which a lion makes when sniffing chemical signals and involves an open mouth with bared teeth, raised muzzle, wrinkled nose closed eyes and relaxed ears.[172] Lions also use chemical and visual marking; males will spray and scrape plots of ground and objects within the territory.[171]

The lion's repertoire of vocalisations is large; variations in intensity and pitch appear to be central to communication. Most lion vocalisations are variations of growling, snarling, meowing and roaring. Other sounds produced include purring, puffing, bleating and humming. Roaring is used to advertise its presence. Lions most often roar at night, a sound that can be heard from a distance of 8 kilometres (5 mi).[173] They tend to roar in a very characteristic manner starting with a few deep, long roars that subside into a series of shorter ones.[174][175]

Conservation

The lion is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. The Indian population is listed on CITES Appendix I and the African population on CITES Appendix II.[1]

In Africa

Several large and well-managed protected areas in Africa host large lion populations. Where an infrastructure for wildlife tourism has been developed, cash revenue for park management and local communities is a strong incentive for lion conservation.[1] Most lions now live in East and Southern Africa; their numbers are rapidly decreasing, and fell by an estimated 30–50% in the late half of the 20th century. Primary causes of the decline include disease and human interference.[1] In 1975, it was estimated that since the 1950s, lion numbers had decreased by half to 200,000 or fewer.[176] Estimates of the African lion population range between 16,500 and 47,000 living in the wild in 2002–2004.[177][73]

In the Republic of the Congo, Odzala-Kokoua National Park was considered a lion stronghold in the 1990s. By 2014, no lions were recorded in the protected area so the population is considered locally extinct.[178] The West African lion population is isolated from the one in Central Africa, with little or no exchange of breeding individuals. In 2015, it was estimated that this population consists of about 400 animals, including fewer than 250 mature individuals. They persist in three protected areas in the region, mostly in one population in the W A P protected area complex, shared by Benin, Burkina Faso and Niger. This population is listed as Critically Endangered.[13] Field surveys in the WAP ecosystem revealed that lion occupancy is lowest in the W National Park, and higher in areas with permanent staff and thus better protection.[179]

A population occurs in Cameroon's Waza National Park, where between approximately 14 and 21 animals persisted as of 2009.[180] In addition, 50 to 150 lions are estimated to be present in Burkina Faso's Arly-Singou ecosystem.[181] In 2015, an adult male lion and a female lion were sighted in Ghana's Mole National Park. These were the first sightings of lions in the country in 39 years.[182] In the same year, a population of up to 200 lions that was previously thought to have been extirpated was filmed in the Alatash National Park, Ethiopia, close to the Sudanese border.[183][184]

In 2005, Lion Conservation Strategies were developed for West and Central Africa, and or East and Southern Africa. The strategies seek to maintain suitable habitat, ensure a sufficient wild prey base for lions, reduce factors that lead to further fragmentation of populations, and make lion–human coexistence sustainable.[185][186] Lion depredation on livestock is significantly reduced in areas where herders keep livestock in improved enclosures. Such measures contribute to mitigating human–lion conflict.[187]

In Asia

The last refuge of the Asiatic lion population is the 1,412 km2 (545 sq mi) Gir National Park and surrounding areas in the region of Saurashtra or Kathiawar Peninsula in Gujarat State, India. The population has risen from approximately 180 lions in 1974 to about 400 in 2010.[188] It is geographically isolated, which can lead to inbreeding and reduced genetic diversity. Since 2008, the Asiatic lion has been listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List.[12] By 2015, the population had grown to 523 individuals inhabiting an area of 7,000 km2 (2,700 sq mi) in Saurashtra.[189][190][191] The Asiatic Lion Census conducted in 2017 recorded about 650 individuals.[192]

The presence of numerous human habitations close to the National Park results in conflict between lions, local people and their livestock.[193][189] Some consider the presence of lions a benefit, as they keep populations of crop damaging herbivores in check.[194] The establishment of a second, independent Asiatic lion population in Kuno Wildlife Sanctuary, located in Madhya Pradesh was planned but in 2017, the Asiatic Lion Reintroduction Project seemed unlikely to be implemented.[195][196]

Captive breeding

Lions imported to Europe before the middle of the 19th century were possibly foremost Barbary lions from North Africa, or Cape lions from Southern Africa.[197] Another 11 animals thought to be Barbary lions kept in Addis Ababa Zoo are descendants of animals owned by Emperor Haile Selassie. WildLink International in collaboration with Oxford University launched an ambitious International Barbary Lion Project with the aim of identifying and breeding Barbary lions in captivity for eventual reintroduction into a national park in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco.[198] However, a genetic analysis showed that the captive lions at Addis Ababa Zoo were not Barbary lions, but rather closely related to wild lions in Chad and Cameroon.[199]

In 1982, the Association of Zoos and Aquariums started a Species Survival Plan for the Asiatic lion to increase its chances of survival. In 1987, it was found that most lions in North American zoos were hybrids between African and Asiatic lions.[200] Breeding programs need to note origins of the participating animals to avoid cross-breeding different subspecies and thus reducing their conservation value.[201] Captive breeding of lions was halted to eliminate individuals of unknown origin and pedigree. Wild-born lions were imported to American zoos from Africa between 1989 and 1995. Breeding was continued in 1998 in the frame of an African lion Species Survival Plan.[202]

About 77% of the captive lions registered in the International Species Information System in 2006 were of unknown origin; these animals might have carried genes that are extinct in the wild and may therefore be important to the maintenance of the overall genetic variability of the lion.[62]

Interactions with humans

In zoos and circuses

.jpg.webp)

Lions are part of a group of exotic animals that have been central to zoo exhibits since the late 18th century. Although many modern zoos are more selective about their exhibits,[203] there are more than 1,000 African and 100 Asiatic lions in zoos and wildlife parks around the world. They are considered an ambassador species and are kept for tourism, education and conservation purposes.[204] Lions can live over twenty years in captivity. One lion in Honolulu Zoo died at the age of 22 in August 2007.[205] His two sisters, born in 1986, also reached the age of 22.[206]

The first European "zoos" spread among noble and royal families in the 13th century, and until the 17th century were called seraglios. At that time, they came to be called menageries, an extension of the cabinet of curiosities. They spread from France and Italy during the Renaissance to the rest of Europe.[207] In England, although the seraglio tradition was less developed, lions were kept at the Tower of London in a seraglio established by King John in the 13th century;[208][209] this was probably stocked with animals from an earlier menagerie started in 1125 by Henry I at his hunting lodge in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, where according to William of Malmesbury lions had been stocked.[210]

Lions were kept in cramped and squalid conditions at London Zoo until a larger lion house with roomier cages was built in the 1870s.[211] Further changes took place in the early 20th century when Carl Hagenbeck designed enclosures with concrete "rocks", more open space and a moat instead of bars, more closely resembling a natural habitat. Hagenbeck designed lion enclosures for both Melbourne Zoo and Sydney's Taronga Zoo; although his designs were popular, the use of bars and caged enclosures prevailed in many zoos until the 1960s.[212] In the late 20th century, larger, more natural enclosures and the use of wire mesh or laminated glass instead of lowered dens allowed visitors to come closer than ever to the animals; some attractions such as the Cat Forest/Lion Overlook of Oklahoma City Zoological Park placed the den on ground level, higher than visitors.[213]

Lion taming has been part of both established circuses and individual acts such as Siegfried & Roy. The practice began in the early 19th century by Frenchman Henri Martin and American Isaac Van Amburgh, who both toured widely and whose techniques were copied by a number of followers.[214] Van Amburgh performed before Queen Victoria in 1838 when he toured Great Britain. Martin composed a pantomime titled Les Lions de Mysore ("the lions of Mysore"), an idea Amburgh quickly borrowed. These acts eclipsed equestrianism acts as the central display of circus shows and entered public consciousness in the early 20th century with cinema. In demonstrating the superiority of human over animal, lion taming served a purpose similar to animal fights of previous centuries.[214] The ultimate proof of a tamer's dominance and control over a lion is demonstrated by the placing of the tamer's head in the lion's mouth. The now-iconic lion tamer's chair was possibly first used by American Clyde Beatty (1903–1965).[215]

Hunting and games

%252C_c._645-635_BC%252C_British_Museum_(16722183731).jpg.webp)

Lion hunting has occurred since ancient times and was often a royal tradition, intended to demonstrate the power of the king over nature. Such hunts took place in a reserved area in front of an audience. The monarch was accompanied by his men and controls were put in place to increase their safety and ease of killing. The earliest surviving record of lion hunting is an ancient Egyptian inscription dated circa 1380 BC that mentions Pharaoh Amenhotep III killing 102 lions in ten years "with his own arrows". The Assyrian emperor Ashurbanipal had one of his lion hunts depicted on a sequence of palace reliefs c. 640 BC, known as the Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal. Lions were also hunted during the Mughal Empire, where Emperor Jahangir is said to have excelled at it.[216] In Ancient Rome, lions were kept by emperors for hunts, gladiator fights and executions.[217]

The Maasai people have traditionally viewed the killing of lions as a rite of passage. Historically, lions were hunted by individuals, however, due to reduced lion populations, elders discourage solo lion hunts.[218] During the European colonisation of Africa in the 19th century, the hunting of lions was encouraged because they were considered pests and lion skins were sold for £1 each.[219] The widely reproduced imagery of the heroic hunter chasing lions would dominate a large part of the century.[220] Trophy hunting of lions in recent years has been met with controversy, notably with the killing of Cecil the lion in mid-2015.[221]

Man-eating

Lions do not usually hunt humans but some (usually males) seem to seek them out. One well-publicised case is the Tsavo maneaters; in 1898, 28 officially recorded railway workers building the Kenya-Uganda Railway were taken by lions over nine months during the construction of a bridge in Kenya.[222] The hunter who killed the lions wrote a book detailing the animals' predatory behaviour; they were larger than normal and lacked manes, and one seemed to suffer from tooth decay. The infirmity theory, including tooth decay, is not favoured by all researchers; an analysis of teeth and jaws of man-eating lions in museum collections suggests that while tooth decay may explain some incidents, prey depletion in human-dominated areas is a more likely cause of lion predation on humans.[223] Sick or injured animals may be more prone to man-eating but the behaviour is not unusual, nor necessarily aberrant.[224]

Lions' proclivity for man-eating has been systematically examined. American and Tanzanian scientists report that man-eating behaviour in rural areas of Tanzania increased greatly from 1990 to 2005. At least 563 villagers were attacked and many eaten over this period. The incidents occurred near Selous National Park in Rufiji District and in Lindi Province near the Mozambican border. While the expansion of villages into bush country is one concern, the authors argue conservation policy must mitigate the danger because in this case, conservation contributes directly to human deaths. Cases in Lindi in which lions seize humans from the centres of substantial villages have been documented.[225] Another study of 1,000 people attacked by lions in southern Tanzania between 1988 and 2009 found that the weeks following the full moon, when there was less moonlight, were a strong indicator of increased night-time attacks on people.[226]

According to Robert R. Frump, Mozambican refugees regularly crossing Kruger National Park, South Africa, at night are attacked and eaten by lions; park officials have said man-eating is a problem there. Frump said thousands may have been killed in the decades after apartheid sealed the park and forced refugees to cross the park at night. For nearly a century before the border was sealed, Mozambicans had regularly crossed the park in daytime with little harm.[227]

Cultural significance

The lion is one of the most widely recognised animal symbols in human culture. It has been extensively depicted in sculptures and paintings, on national flags, and in contemporary films and literature.[45] It appeared as a symbol for strength and nobility in cultures across Europe, Asia and Africa, despite incidents of attacks on people. The lion has been depicted as "king of the jungle" and "king of beasts", and thus became a popular symbol for royalty and stateliness.[228] The lion is also used as a symbol of sporting teams.[229]

Africa

In sub-Saharan Africa, the lion has been a common character in stories, proverbs and dances, but rarely featured in visual arts.[230] In some cultures, the lion symbolises power and royalty.[231] In the Swahili language, the lion is known as simba which also means "aggressive", "king" and "strong".[55] Some rulers had the word "lion" in their nickname. Sundiata Keita of the Mali Empire was called "Lion of Mali".[232] The founder of the Waalo kingdom is said to have been raised by lions and returned to his people part-lion to unite them using the knowledge he learned from the lions.[231]

In parts of West Africa, lions symbolised the top class of their social hierarchies.[231] In more heavily forested areas where lions were rare, the leopard represented the top of the hierarchy.[230] In parts of West and East Africa, the lion is associated with healing and provides the connection between seers and the supernatural. In other East African traditions, the lion represents laziness.[231] In much of African folklore, the lion is portrayed as having low intelligence and is easily tricked by other animals.[232]

The ancient Egyptians portrayed several of their war deities as lionesses, which they revered as fierce hunters. Egyptian deities associated with lions include Sekhmet, Bast, Mafdet, Menhit, Pakhet and Tefnut.[228] These deities were often connected with the sun god Ra and his fierce heat, and their dangerous power was invoked to guard people or sacred places. The sphinx, a figure with a lion's body and the head of a human or other creature, represented a pharaoh or deity who had taken on this protective role.[233]

Eastern world

The lion was a prominent symbol in ancient Mesopotamia from Sumer up to Assyrian and Babylonian times, where it was strongly associated with kingship.[234] Lions were among the major symbols of the goddess Inanna/Ishtar.[235][236] The Lion of Babylon was the foremost symbol of the Babylonian Empire.[237] The Lion of Judah is the biblical emblem of the tribe of Judah and the later Kingdom of Judah.[238] Lions are frequently mentioned in the Bible, notably in the Book of Daniel, in which the eponymous hero refuses to worship King Darius and is forced to sleep in the lions' den where he is miraculously unharmed (Dan 6). In the Book of Judges, Samson kills a lion as he travels to visit a Philistine woman.(Judg 14).[239]

Indo-Persian chroniclers regarded the lion as keeper of order in the realm of animals. The Sanskrit word mrigendra signifies a lion as king of animals in general or deer in particular.[240] Narasimha, the man-lion, is one of ten avatars of the Hindu god Vishnu.[241] Singh is an ancient Indian vedic name meaning "lion", dating back over 2,000 years. It was originally used only by Rajputs, a Hindu Kshatriya or military caste but is used by millions of Hindu Rajputs and more than twenty million Sikhs today.[242] The Lion Capital of Ashoka, erected by Emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century CE, depicts four lions standing back to back. It was made the National Emblem of India in 1950.[243] The lion is also symbolic for the Sinhalese people, the term derived from the Sanskrit Sinhala, meaning "of lions"[244] while a sword-wielding lion is the central figure on the national flag of Sri Lanka.[245]

The lion is a common motif in Chinese art; it was first used in art during the late Spring and Autumn period (fifth or sixth century BC) and became more popular during the Han Dynasty (206 BC – AD 220) when imperial guardian lions started to be placed in front of imperial palaces for protection. Because lions have never been native to China, early depictions were somewhat unrealistic; after the introduction of Buddhist art to China in the Tang Dynasty after the sixth century AD, lions were usually depicted wingless with shorter, thicker bodies and curly manes.[246] The lion dance is a traditional dance in Chinese culture in which performers in lion costumes mimic a lion's movements, often with musical accompaniment from cymbals, drums and gongs. They are performed at Chinese New Year, the August Moon Festival and other celebratory occasions for good luck.[247]

Western world

Lion-headed figures and amulets were excavated in tombs in the Greek islands of Crete, Euboea, Rhodes, Paros and Chios. They are associated with the Egyptian deity Sekhmet and date to the early Iron Age between the 9th and 6th centuries BC.[248] The lion is featured in several of Aesop's fables, notably The Lion and the Mouse.[249] The Nemean lion was symbolic in ancient Greece and Rome, represented as the constellation and zodiac sign Leo, and described in mythology, where it was killed and worn by the hero Heracles,[250] symbolising victory over death.[251] Lancelot and Gawain were also heroes slaying lions in the Middle Ages. In some medieval stories, lions were portrayed as allies and companions.[252] "Lion" was the nickname of several medieval warrior-rulers with a reputation for bravery, such as Richard the Lionheart.[228]

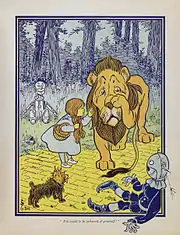

Lions continue to appear in modern literature as characters including the messianic Aslan in the 1950 novel The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and The Chronicles of Narnia series by C. S. Lewis,[253] and the comedic Cowardly Lion in L. Frank Baum's 1900 The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.[254] Lion symbolism was used from the advent of cinema; one of the most iconic and widely recognised lions is Leo, which has been the mascot for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios since the 1920s.[255] The 1966 film Born Free features Elsa the lioness and is based on the 1960 non-fiction book with the same title.[256] The lion's role as king of the beasts has been used in the 1994 Disney animated feature film The Lion King.[257]

Lions are frequently depicted on coats of arms, like on the coat of arms of Finland,[258] either as a device on shields or as supporters, but the lioness is used much less frequently.[259] The heraldic lion is particularly common in British arms. It is traditionally depicted in a great variety of attitudes, although within French heraldry only lions rampant are considered to be lions; feline figures in any other position are instead referred to as leopards.[260]

See also

- List of largest cats

- Mapogo lion coalition

- Roar (1981 film)

- Tiger versus lion

Explanatory notes

- Populations of India are listed in Appendix I.

References

Citations

- Bauer, H.; Packer, C.; Funston, P. F.; Henschel, P. & Nowell, K. (2017) [errata version of 2016 assessment]. "Panthera leo". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T15951A115130419. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T15951A107265605.en. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Species Panthera leo". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 546. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis leo". Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Vol. Tomus I (decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 41. (in Latin)

- "lion". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 20 March 2022. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Liddell, H. G. & Scott, R. (1940). "πάνθηρ". A Greek-English Lexicon (Revised and augmented ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Johnson, W. E.; Eizirik, E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Murphy, W. J.; Antunes, A.; Teeling, E. & O'Brien, S. J. (2006). "The late miocene radiation of modern Felidae: A genetic assessment". Science. 311 (5757): 73–77. Bibcode:2006Sci...311...73J. doi:10.1126/science.1122277. PMID 16400146. S2CID 41672825.

- Werdelin, L.; Yamaguchi, N.; Johnson, W. E. & O'Brien, S. J. (2010). "Phylogeny and evolution of cats (Felidae)". Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids: 59–82.

- Davis, B. W.; Li, G. & Murphy, W. J. (2010). "Supermatrix and species tree methods resolve phylogenetic relationships within the big cats, Panthera (Carnivora: Felidae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 56 (1): 64–76. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.01.036. PMID 20138224.

- Mazák, J. H.; Christiansen, P.; Kitchener, A. C. & Goswami, A. (2011). "Oldest known pantherine skull and evolution of the tiger". PLOS ONE. 6 (10): e25483. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...625483M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025483. PMC 3189913. PMID 22016768.

- Oken, L. (1816). "1. Art, Panthera". Lehrbuch der Zoologie. 2. Abtheilung. Jena: August Schmid & Comp. p. 1052.

- Hemmer, H. (1974). "Untersuchungen zur Stammesgeschichte der Pantherkatzen (Pantherinae) Teil 3. Zur Artgeschichte des Löwen Panthera (Panthera) leo (Linnaeus, 1758)". Veröffentlichungen der Zoologischen Staatssammlung. 17: 167–280.

- Breitenmoser, U.; Mallon, D. P.; Ahmad Khan, J. and; Driscoll, C. (2008). "Panthera leo ssp. persica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T15952A5327221. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T15952A5327221.en.

- Henschel, P.; Bauer, H.; Sogbohoussou, E. & Nowell, K. (2015). "Panthera leo West Africa subpopulation". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T68933833A54067639.en.

- Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O'Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z. & Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News. Special Issue 11: 71–73.

- Wood, J. G. (1865). "Felidæ; or the Cat Tribe". The Illustrated Natural History. Mammalia, Volume 1. London: Routledge. p. 129−148.

- Hunter, L.; Barrett, P. (2018). "Lion Panthera leo". The Field Guide to Carnivores of the World (2 ed.). London, Oxford, New York, New Delhi, Sydney: Bloomsbury. pp. 46−47. ISBN 978-1-4729-5080-2.

- de Manuel, M.; Barnett, R.; Sandoval-Velasco, M.; Yamaguchi, N.; Vieira, F. G.; Mendoza, M. L. Z.; Liu, S.; Martin, M. D.; Sinding, M-S. S.; Mak, S. S. T.; Carøe, C.; Liu, S.; Guo, C.; Zheng, J.; Zazula, G.; Baryshnikov, G.; Eizirik, E.; Koepfli, K-P.; Johnson, W. E.; Antunes, A.; Sicheritz-Ponten, T.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Larson, G.; Yang, H; O’Brien, S. J.; Hansen, A. J.; Zhang, G.; Marques-Bonet, T.; Gilbert, M. T. P. (2020). "The evolutionary history of extinct and living lions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (20): 10927–10934. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11710927D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1919423117. PMC 7245068. PMID 32366643.

- Bertola, L. D.; Jongbloed, H.; Van Der Gaag, K. J.; De Knijff, P.; Yamaguchi, N.; Hooghiemstra, H.; Bauer, H.; Henschel, P.; White, P. A.; Driscoll, C. A.; Tende, T.; Ottosson, U.; Saidu, Y.; Vrieling, K.; de Iongh, H. H. (2016). "Phylogeographic patterns in Africa and High Resolution Delineation of genetic clades in the Lion (Panthera leo)". Scientific Reports. 6: 30807. Bibcode:2016NatSR...630807B. doi:10.1038/srep30807. PMC 4973251. PMID 27488946.

- Manuel, M. d.; Ross, B.; Sandoval-Velasco, M.; Yamaguchi, N.; Vieira, F. G.; Mendoza, M. L. Z.; Liu, S.; Martin, M. D.; Sinding, M.-H. S.; Mak, S. S. T.; Carøe, C.; Liu, S.; Guo, C.; Zheng, J.; Zazula, G.; Baryshnikov, G.; Eizirik, E.; Koepfli, K.-P.; Johnson, W. E.; Antunes, A.; Sicheritz-Ponten, T.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Larson, G.; Yang, H.; O'Brien, S. J.; Hansen, A. J.; Zhang, G.; Marques-Bonet, T. & Gilbert, M. T. P. (2020). "The evolutionary history of extinct and living lions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (20): 10927–10934. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11710927D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1919423117. PMC 7245068. PMID 32366643.

- Christiansen, P. (2008). "Phylogeny of the great cats (Felidae: Pantherinae), and the influence of fossil taxa and missing characters". Cladistics. 24 (6): 977–992. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2008.00226.x. PMID 34892880. S2CID 84497516.

- Manamendra-Arachchi, K.; Pethiyagoda, R.; Dissanayake, R. & Meegaskumbura, M. (2005). "A second extinct big cat from the late Quaternary of Sri Lanka" (PDF). The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology (Supplement 12): 423–434. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2007.

- Marciszak, A. & Stefaniak, K. (2010). "Two forms of cave lion: Middle Pleistocene Panthera spelaea fossilis Reichenau, 1906 and Upper Pleistocene Panthera spelaea spelaea Goldfuss, 1810 from the Bisnik Cave, Poland". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 258 (3): 339–351. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2010/0117.

- Sabol, M. (2014). "Panthera fossilis (Reichenau, 1906) (Felidae, Carnivora) from Za Hájovnou Cave (Moravia, The Czech Republic): A Fossil Record from 1987–2007". Acta Musei Nationalis Pragae, Series B, Historia Naturalis. 70 (1–2): 59–70. doi:10.14446/AMNP.2014.59.

- Stuart, A. J. & Lister, A. M. (2011). "Extinction chronology of the cave lion Panthera spelaea". Quaternary Science Reviews. 30 (17): 2329–40. Bibcode:2011QSRv...30.2329S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.04.023.

- Hemmer, H. (2011). "The story of the cave lion – Panthera Leo Spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810) – A review". Quaternaire. 4: 201–208.

- Barnett, R.; Mendoza, M. L. Z.; Soares, A. E. R.; Ho, S. Y. W.; Zazula, G.; Yamaguchi, N.; Shapiro, B.; Kirillova, I. V.; Larson, G. & Gilbert, M. T. P. (2016). "Mitogenomics of the Extinct Cave Lion, Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810), resolve its position within the Panthera cats". Open Quaternary. 2: 4. doi:10.5334/oq.24.

- Burger, J.; Rosendahl, W.; Loreille, O.; Hemmer, H.; Eriksson, T.; Götherström, A.; Hiller, J.; Collins, M. J.; Wess, T. & Alt, K. W. (2004). "Molecular phylogeny of the extinct cave lion Panthera leo spelaea" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 30 (3): 841–849. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.07.020. PMID 15012963. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 September 2007.

- Packer, C. & Clottes, J. (2000). "When Lions Ruled France" (PDF). Natural History. 109 (9): 52–57.

- Chimento, N. R. & Agnolin, F. L. (2017). "The fossil American lion (Panthera atrox) in South America: Palaeobiogeographical implications". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 16 (8): 850–864. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2017.06.009.

- Harington, C. R. (1969). "Pleistocene remains of the lion-like cat (Panthera atrox) from the Yukon Territory and northern Alaska". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 6 (5): 1277–1288. Bibcode:1969CaJES...6.1277H. doi:10.1139/e69-127.

- Christiansen, P. & Harris, J. M. (2009). "Craniomandibular morphology and phylogenetic affinities of Panthera atrox: implications for the evolution and paleobiology of the lion lineage". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (3): 934–945. doi:10.1671/039.029.0314. S2CID 85975640.

- King, L. M. & Wallace, S. C. (2014). "Phylogenetics of Panthera, including Panthera atrox, based on craniodental characters". Historical Biology. 26 (6): 827–833. doi:10.1080/08912963.2013.861462. S2CID 84229141.

- Werdelin, L.; Yamaguchi, N.; Johnson, W. E. & O'Brien, S. J. (2010). "Phylogeny and evolution of cats (Felidae)". In Macdonald, D. W. & Loveridge, A. J. (eds.). Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 59–82. ISBN 978-0-19-923445-5.

- Li, G.; Davis, B. W.; Eizirik, E. & Murphy, W. J. (2016). "Phylogenomic evidence for ancient hybridization in the genomes of living cats (Felidae)". Genome Research. 26 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1101/gr.186668.114. PMC 4691742. PMID 26518481.

- Tseng, Z. J.; Wang, X.; Slater, G. J.; Takeuchi, G. T.; Li, Q.; Liu, J. & Xie, G. (2014). "Himalayan fossils of the oldest known pantherine establish ancient origin of big cats". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1774): 20132686. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2686. PMC 3843846. PMID 24225466.

- Barnett, R.; Shapiro, B.; Barnes, I.; Ho, S. Y. W.; Burger, J.; Yamaguchi, N.; Higham, T. F. G.; Wheeler, H. T.; Rosendahl, W.; Sher, A. V.; Sotnikova, M.; Kuznetsova, T.; Baryshnikov, G. F.; Martin, L. D.; Harington, C. R.; Burns, J. A. & Cooper, A. (2009). "Phylogeography of lions (Panthera leo ssp.) reveals three distinct taxa and a late Pleistocene reduction in genetic diversity" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 18 (8): 1668–1677. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04134.x. PMID 19302360. S2CID 46716748.

- Argant, A. & Brugal, J.-P. (2017). "The cave lion Panthera (Leo) spelaea and its evolution: Panthera spelaea intermedia nov. subspecies". Acta Zoologica Cracoviensia. 60 (2): 58–103. doi:10.3409/azc.60_2.59.

- Barnett, R.; Yamaguchi, N.; Shapiro, B.; Ho, S. Y.; Barnes, I.; Sabin, R.; Werdelin, L.; Cuisin, J. & Larson, G. (2014). "Revealing the maternal demographic history of Panthera leo using ancient DNA and a spatially explicit genealogical analysis". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 14 (1): 70. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-14-70. PMC 3997813. PMID 24690312.

- Bertola, L. D.; Van Hooft, W. F.; Vrieling, K.; Uit De Weerd, D. R.; York, D. S.; Bauer, H.; Prins, H. H. T.; Funston, P. J.; Udo De Haes, H. A.; Leirs, H.; Van Haeringen, W. A.; Sogbohossou, E.; Tumenta, P. N. & De Iongh, H. H. (2011). "Genetic diversity, evolutionary history and implications for conservation of the lion (Panthera leo) in West and Central Africa". Journal of Biogeography. 38 (7): 1356–1367. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02500.x. S2CID 82728679.

- Pocock, R. I. (1898). "Lion-Tiger Hybrid". Nature. 58 (1496): 200. Bibcode:1898Natur..58Q.200P. doi:10.1038/058200b0. S2CID 4056029.

- Benirschke, K. (1967). "Sterility and fertility of interspecific mammalian hybrids". Comparative aspects of reproductive failure. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 218––234. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-48949-5_12. ISBN 978-3-642-48949-5.

- Shi, W. (2005). "Hybrid dysgenesis effects" (PDF). Growth and Behaviour: Epigenetic and Genetic Factors Involved in Hybrid Dysgenesis (PhD). Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. p. 8–10.

- Rafferty, J. P. (2011). "The Liger". Carnivores: Meat-eating Mammals. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-61530-340-3. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Li, L.; Tao, M.; Zhang, C.; Qin, Q.; Xiao, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S. (2014). "Research advances in animal distant hybridization" (PDF). Science China Life Sciences. 57 (9): 889–902. doi:10.1007/s11427-014-4707-1. PMID 25091377. S2CID 18179301.

- Guggisberg, C. A. W. (1975). "Lion Panthera leo (Linnaeus, 1758)". Wild Cats of the World. New York: Taplinger Publishing. pp. 138–179. ISBN 978-0-8008-8324-9.

- Haas, S. K.; Hayssen, V.; Krausman, P. R. (2005). "Panthera leo" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 762: 1–11. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2005)762[0001:PL]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 198968757. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2017.

- Schaller, pp. 28–30.

- Mitra, S. (2005). Gir Forest and the saga of the Asiatic lion. New Delhi: Indus. ISBN 978-8173871832.

- Pocock, R. I. (1939). "Panthera leo". The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Mammalia. Volume 1. London: Taylor and Francis Ltd. pp. 212–222.

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskii, A. A. (1992) [1972]. "Lion". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union, Volume II, Part 2]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 83–95. ISBN 978-90-04-08876-4.

- Davis, D. D. (1962). "Allometric relationships in Lions vs. Domestic Cats". Evolution. 16 (4): 505–514. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1962.tb03240.x.

- Calder, W. A. (1996). "Skeletal muscle". Size, Function, and Life History. Courier Corporation. pp. 17–21. ISBN 978-0-486-69191-6.

- Smuts, G. L.; Robinson, G. A.; Whyte, I. J. (1980). "Comparative growth of wild male and female lions (Panthera leo)". Journal of Zoology. 190 (3): 365–373. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1980.tb01433.x.

- Chellam, R. and A. J. T. Johnsingh (1993). "Management of Asiatic lions in the Gir Forest, India". In Dunstone, N.; Gorman, M. L. (eds.). Mammals as predators: the proceedings of a symposium held by the Zoological Society of London and the Mammal Society, London. Volume 65 of Symposia of the Zoological Society of London. London: Zoological Society of London. pp. 409–23.

- Brakefield, T. (1993). "Lion: Sociable Simba". Big Cats: Kingdom of Might. London: Voyageur Press. pp. 50–67. ISBN 978-0-89658-329-0.

- Nowak, R. M. (1999). "Panthera leo". Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 832–834. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- Nowell, K.; Jackson, P. (1996). "African lion, Panthera leo (Linnaeus, 1758); Asiatic lion, Panthera leo persica (Meyer, 1826)" (PDF). Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. pp. 17–21, 37–41. ISBN 978-2-8317-0045-8.

- Smuts, G. L. (1982). Lion. Johannesburg, South Africa: MacMillan.

- Sinha, S. P. (1987). Ecology of wildlife with special reference to the lion (Panthera leo persica) in Gir Wildlife Sanctuary, Saurashtra, Gujurat (PhD). Rajkot: Saurashtra University. ISBN 978-3844305456.

- West, P. M.; Packer, C. (2013). "Panthera leo Lion". In Kingdon, J.; Happold, D.; Butynski, T.; Hoffmann, M.; Happold, M.; Kalina, J. (eds.). Mammals of Africa. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 150–159. ISBN 978-1-4081-8996-2.

- Yamaguchi, Nobuyuki; Cooper, A.; Werdelin, L.; MacDonald, David W. (2004). "Evolution of the mane and group-living in the lion (Panthera leo): a review". Journal of Zoology. 263 (4): 329–342. doi:10.1017/S0952836904005242.

- Barnett, R.; Yamaguchi, N.; Barnes, I.; Cooper, A. (2006). "Lost populations and preserving genetic diversity in the lion Panthera leo: Implications for its ex situ conservation" (PDF). Conservation Genetics. 7 (4): 507–514. doi:10.1007/s10592-005-9062-0. S2CID 24190889. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 August 2006.

- Menon, V. (2003). A Field Guide to Indian Mammals. New Delhi: Dorling Kindersley India. ISBN 978-0-14-302998-4.

- Schoe, M.; Sogbohossou, E. A.; Kaandorp, J.; De Iongh, H. (2010). Progress Report—collaring operation Pendjari Lion Project, Benin. The Dutch Zoo Conservation Fund (for funding the project).

- Trivedi, Bijal P. (2005). "Are Maneless Tsavo Lions Prone to Male Pattern Baldness?". National Geographic. Retrieved 7 July 2007.

- Munson, L. (2006). "Contraception in felids". Theriogenology. 66 (1): 126–134. doi:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2006.03.016. PMID 16626799.

- Dell'Amore, C. (2016). "No, Those Aren't Male Lions Mating. One Is Likely a Female". National Geographic. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- Turner, J. A.; Vasicek, C. A.; Somers, M. J. (2015). "Effects of a colour variant on hunting ability: the white lion in South Africa". Open Science Repository Biology: e45011830.

- McBride, C. (1977). The White Lions of Timbavati. Johannesburg: E. Stanton. ISBN 978-0-949997-32-6.

- Tucker, L. (2003). Mystery of the White Lions—Children of the Sun God. Mapumulanga: Npenvu Press. ISBN 978-0-620-31409-1.

- Riggio, J.; Jacobson, A.; Dollar, L.; Bauer, H.; Becker, M.; Dickman, A.; Funston, P.; Groom, R.; Henschel, P.; de Iongh, H.; Lichtenfeld, L.; Pimm, S. (2013). "The size of savannah Africa: a lion's (Panthera leo) view". Biodiversity Conservation. 22 (1): 17–35. doi:10.1007/s10531-012-0381-4.

- Schaller, p. 5.

- Chardonnet, P. (2002). Conservation of African lion (PDF). Paris, France: International Foundation for the Conservation of Wildlife. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2013.

- Black, S. A.; Fellous, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Roberts, D. L. (2013). "Examining the Extinction of the Barbary Lion and Its Implications for Felid Conservation". PLOS ONE. 8 (4): e60174. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...860174B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060174. PMC 3616087. PMID 23573239.

- Schnitzler, A.; Hermann, L. (2019). "Chronological distribution of the tiger Panthera tigris and the Asiatic lion Panthera leo persica in their common range in Asia". Mammal Review. 49 (4): 340–353. doi:10.1111/mam.12166. S2CID 202040786.

- Üstay, A. H. (1990). Hunting in Turkey. Istanbul: BBA.

- Firouz, E. (2005). The complete fauna of Iran. I. B. Tauris. pp. 5–67. ISBN 978-1-85043-946-2.

- Guggisberg, C. A. W. (1961). Simba: the life of the lion. Cape Town: Howard Timmins.

- Kinnear, N. B. (1920). "The past and present distribution of the lion in southeastern Asia". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 27: 34–39.

- Schaller, p. 122.

- Schaller, pp. 120–21.

- Schaller, p. 33.

- Schaller, p. 37.

- Schaller, p. 39.

- Schaller, p. 44.

- Schaller, p. 34–35.

- Milius, S. (2002). "Biology: Maneless lions live one guy per pride". Society for Science & the Public. 161 (16): 253. doi:10.1002/scin.5591611614.

- Estes, R. (1991). "Lion". The behavior guide to African mammals: including hoofed mammals, carnivores, primates. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 369–376. ISBN 978-0-520-08085-0.

- Schaller, pp. 52–54.

- Hanby, J. P. & Bygott, J. D. (1979). "Population changes in lions and other predators". In Sinclair, A. R. E. & Norton-Griffiths, M. (eds.). Serengeti: dynamics of an ecosystem. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 249–262.

- Borrego, N.; Ozgul, A.; Slotow, R. & Packer, C. (2018). "Lion population dynamics: do nomadic males matter?". Behavioral Ecology. 29 (3): 660–666. doi:10.1093/beheco/ary018.

- van Hooft, P.; Keet, D.F.; Brebner, D.K. & Bastos, A.D. (2018). "Genetic insights into dispersal distance and disperser fitness of African lions (Panthera leo) from the latitudinal extremes of the Kruger National Park, South Africa". BMC Genetics. 19 (1): 21. doi:10.1186/s12863-018-0607-x. PMC 5883395. PMID 29614950.

- Heinsohn, R. & C. Packer (1995). "Complex cooperative strategies in group-territorial African lions" (PDF). Science. 269 (5228): 1260–1262. Bibcode:1995Sci...269.1260H. doi:10.1126/science.7652573. PMID 7652573. S2CID 35849910.

- Morell, V. (1995). "Cowardly lions confound cooperation theory". Science. 269 (5228): 1216–1217. Bibcode:1995Sci...269.1216M. doi:10.1126/science.7652566. PMID 7652566. S2CID 44676637.

- Jahn, G. C. (1996). "Lioness Leadership". Science. 271 (5253): 1215. Bibcode:1996Sci...271.1215J. doi:10.1126/science.271.5253.1215a. PMID 17820922. S2CID 5058849.

- Joslin, P. (1973). The Asiatic lion: a study of ecology and behaviour. University of Edinburgh, UK: Department of Forestry and Natural Resources.

- Chakrabarti, S. & Jhala, Y. V. (2017). "Selfish partners: resource partitioning in male coalitions of Asiatic lions". Behavioral Ecology. 28 (6): 1532–1539. doi:10.1093/beheco/arx118. PMC 5873260. PMID 29622932.

- Schaller, pp. 208.

- Frank, L. G. (1998). Living with lions: carnivore conservation and livestock in Laikipia District, Kenya. Mpala Research Centre, Nanyuki: US Agency for International Development, Conservation of Biodiverse Resource Areas Project, 623-0247-C-00-3002-00.

- Hayward, M. W.; Kerley, G. I. H. (2005). "Prey preferences of the lion (Panthera leo)" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 267 (3): 309–322. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.611.8271. doi:10.1017/S0952836905007508.

- Mukherjee, S.; Goyal, S. P.; Chellam, R. (1994). "Refined techniques for the analysis of Asiatic lion Panthera leo persica scats". Acta Theriologica. 39 (4): 425–430. doi:10.4098/AT.arch.94-50.

- Meena, V.; Jhala, Y.V.; Chellam, R. & Pathak, B. (2011). "Implications of diet composition of Asiatic lions for their conservation". Journal of Zoology. 284 (1): 60–67. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00780.x.

- Schaller, p. 195.

- Schaller, pp. 220–221.

- Schaller, p. 153.

- Joubert, D. (2006). "Hunting behaviour of lions (Panthera leo) on elephants (Loxodonta africana) in the Chobe National Park, Botswana". African Journal of Ecology. 44 (2): 279–281. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2006.00626.x.

- Power, R. J.; Compion, R. X. S. (2009). "Lion predation on elephants in the Savuti, Chobe National Park, Botswana". African Zoology. 44 (1): 36–44. doi:10.3377/004.044.0104. S2CID 86371484.

- Stander, P. E. (1992). "Cooperative hunting in lions: the role of the individual" (PDF). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 29 (6): 445–454. doi:10.1007/BF00170175. S2CID 2588727.

- Loarie, S. R.; Tambling, C. J.; Asner, G. P. (2013). "Lion hunting behaviour and vegetation structure in an African savanna" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 85 (5): 899–906. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.01.018. hdl:2263/41825. S2CID 53185309.

- Schaller, p. 248.

- Schaller, pp. 233, 247–248

- Wilson, A.; Hubel, T.; Wilshin, S.; et al. (2018). "Biomechanics of predator–prey arms race in lion, zebra, cheetah and impala" (PDF). Nature. 554 (7691): 183–188. Bibcode:2018Natur.554..183W. doi:10.1038/nature25479. PMID 29364874. S2CID 4405091.

- Schaller, p. 237.

- Schaller, p. 244, 263–267.

- West, P. M.; Packer, C. (2002). "Sexual Selection, Temperature, and the Lion's Mane". Science. 297 (5585): 1339–1943. Bibcode:2002Sci...297.1339W. doi:10.1126/science.1073257. PMID 12193785. S2CID 15893512.

- West, P. M. (2005). "The Lion's Mane: Neither a token of royalty nor a shield for fighting, the mane is a signal of quality to mates and rivals, but one that comes with consequences". American Scientist. 93 (3): 226–235. doi:10.1511/2005.3.226. JSTOR 27858577.

- Schaller, pp. 270–76.

- Schaller, p. 133.

- Schaller, p. 276.

- Schaller, p. 213–216.

- "Behavior and Diet". African Wildlife Foundation website. African Wildlife Foundation. 1996. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- Hayward, M. W. (2006). "Prey preferences of the spotted hyaena (Crocuta crocuta) and degree of dietary overlap with the lion (Panthera leo)" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 270 (4): 606–614. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00183.x.

- Kruuk, H. (2014). The Spotted Hyena: A Study of Predation and Social Behaviour (2nd ed.). Echo Point Books & Media. pp. 128–138. ISBN 978-1626549050.