Biodiesel

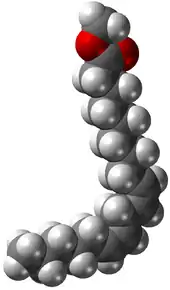

Biodiesel is a form of diesel fuel derived from plants or animals and consisting of long-chain fatty acid esters. It is typically made by chemically reacting lipids such as animal fat (tallow),[1] soybean oil,[2] or some other vegetable oil[3] with an alcohol, producing a methyl, ethyl or propyl ester by the process of transesterification.

.JPG.webp)

Unlike the vegetable and waste oils used to fuel converted diesel engines, biodiesel is a drop-in biofuel, meaning it is compatible with existing diesel engines and distribution infrastructure. However, it is usually blended with petrodiesel (typically to less than 10%) since most engines cannot run on pure Biodiesel without modification.[4][5] Biodiesel blends can also be used as heating oil.

The US National Biodiesel Board defines "biodiesel" as a mono-alkyl ester.[6]

Blends

Blends of biodiesel and conventional hydrocarbon-based diesel are most commonly distributed for use in the retail diesel fuel marketplace. Much of the world uses a system known as the "B" factor to state the amount of biodiesel in any fuel mix:[7]

- 100% biodiesel is referred to as B100

- 20% biodiesel, 80% petrodiesel is labeled B20[4]

- 7% biodiesel, 93% petrodiesel is labeled B7

- 5% biodiesel, 95% petrodiesel is labeled B5

- 2% biodiesel, 98% petrodiesel is labeled B2

Blends of 20% biodiesel and lower can be used in diesel equipment with no, or only minor modifications,[8] although certain manufacturers do not extend warranty coverage if equipment is damaged by these blends. The B6 to B20 blends are covered by the ASTM D7467 specification.[9] Biodiesel can also be used in its pure form (B100), but may require certain engine modifications to avoid maintenance and performance problems.[10] Blending B100 with petroleum diesel may be accomplished by:

- Mixing in tanks at manufacturing point prior to delivery to tanker truck

- Splash mixing in the tanker truck (adding specific percentages of biodiesel and petroleum diesel)

- In-line mixing, two components arrive at tanker truck simultaneously.

- Metered pump mixing, petroleum diesel and biodiesel meters are set to X total volume,

Historical background

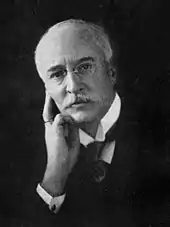

Transesterification of a vegetable oil was conducted as early as 1853 by Patrick Duffy, four decades before the first diesel engine became functional.[11][12] Rudolf Diesel's prime model, a single 10 ft (3.05 m) iron cylinder with a flywheel at its base, ran on its own power for the first time in Augsburg, Germany, on 10 August 1893 running on nothing but peanut oil. In remembrance of this event, 10 August has been declared "International Biodiesel Day".[13]

It is often reported that Diesel designed his engine to run on peanut oil, but this is not the case. Diesel stated in his published papers, "at the Paris Exhibition in 1900 (Exposition Universelle) there was shown by the Otto Company a small Diesel engine, which, at the request of the French government ran on arachide (earth-nut or pea-nut) oil (see biodiesel), and worked so smoothly that only a few people were aware of it. The engine was constructed for using mineral oil, and was then worked on vegetable oil without any alterations being made. The French Government at the time thought of testing the applicability to power production of the Arachide, or earth-nut, which grows in considerable quantities in their African colonies, and can easily be cultivated there." Diesel himself later conducted related tests and appeared supportive of the idea.[14] In a 1912 speech Diesel said, "the use of vegetable oils for engine fuels may seem insignificant today but such oils may become, in the course of time, as important as petroleum and the coal-tar products of the present time."

Despite the widespread use of petroleum-derived diesel fuels, interest in vegetable oils as fuels for internal combustion engines was reported in several countries during the 1920s and 1930s and later during World War II. Belgium, France, Italy, the United Kingdom, Portugal, Germany, Brazil, Argentina, Japan and China were reported to have tested and used vegetable oils as diesel fuels during this time. Some operational problems were reported due to the high viscosity of vegetable oils compared to petroleum diesel fuel, which results in poor atomization of the fuel in the fuel spray and often leads to deposits and coking of the injectors, combustion chamber and valves. Attempts to overcome these problems included heating of the vegetable oil, blending it with petroleum-derived diesel fuel or ethanol, pyrolysis and cracking of the oils.

On 31 August 1937, G. Chavanne of the University of Brussels (Belgium) was granted a patent for a "Procedure for the transformation of vegetable oils for their uses as fuels" (fr. "Procédé de Transformation d’Huiles Végétales en Vue de Leur Utilisation comme Carburants") Belgian Patent 422,877. This patent described the alcoholysis (often referred to as transesterification) of vegetable oils using ethanol (and mentions methanol) in order to separate the fatty acids from the glycerol by replacing the glycerol with short linear alcohols. This appears to be the first account of the production of what is known as "biodiesel" today.[15] This is similar (copy) to the patented methods used in the 18th century to make lamp-oil, and may be inspired by some old historical oil lamps, in some places.

More recently, in 1977, Brazilian scientist Expedito Parente invented and submitted for patent, the first industrial process for the production of biodiesel.[16] This process is classified as biodiesel by international norms, conferring a "standardized identity and quality. No other proposed biofuel has been validated by the motor industry."[17] As of 2010, Parente's company Tecbio is working with Boeing and NASA to certify bioquerosene (bio-kerosene), another product produced and patented by the Brazilian scientist.[18]

Research into the use of transesterified sunflower oil, and refining it to diesel fuel standards, was initiated in South Africa in 1979. By 1983, the process for producing fuel-quality, engine-tested biodiesel was completed and published internationally.[19] An Austrian company, Gaskoks, obtained the technology from the South African Agricultural Engineers; the company erected the first biodiesel pilot plant in November 1987, and the first industrial-scale plant in April 1989 (with a capacity of 30,000 tons of rapeseed per annum).

Throughout the 1990s, plants were opened in many European countries, including the Czech Republic, Germany and Sweden. France launched local production of biodiesel fuel (referred to as diester) from rapeseed oil, which is mixed into regular diesel fuel at a level of 5%, and into the diesel fuel used by some captive fleets (e.g. public transportation) at a level of 30%. Renault, Peugeot and other manufacturers have certified truck engines for use with up to that level of partial biodiesel; experiments with 50% biodiesel are underway. During the same period, nations in other parts of the world also saw local production of biodiesel starting up: by 1998, the Austrian Biofuels Institute had identified 21 countries with commercial biodiesel projects. 100% biodiesel is now available at many normal service stations across Europe.

Properties

The color of biodiesel ranges from golden to dark brown, depending on the production method. It is slightly miscible with water, has a high boiling point and low vapor pressure. The flash point of biodiesel exceeds 130 °C (266 °F),[20] significantly higher than that of petroleum diesel which may be as low as 52 °C (126 °F).[21][22] Biodiesel has a density of ~0.88 g/cm3, higher than petrodiesel (~0.85 g/cm3).[21][22]

The calorific value of biodiesel is about 37.27 MJ/kg.[23] This is 9% lower than regular Number 2 petrodiesel. Variations in biodiesel energy density is more dependent on the feedstock used than the production process. Still, these variations are less than for petrodiesel.[24] It has been claimed biodiesel gives better lubricity and more complete combustion thus increasing the engine energy output and partially compensating for the higher energy density of petrodiesel.[25]

Biodiesel also contains virtually no sulfur[26] and although lacking sulfur compounds in as in petrodiesel that provide much of the lubricity, it has promising lubricating properties and cetane ratings compared to low sulfur diesel fuels and often used as an additive to ultra-low-sulfur diesel (ULSD) fuel to aid with lubrication.[27] Biodiesel Fuels with higher lubricity may increase the usable life of high-pressure fuel injection equipment that relies on the fuel for its lubrication. Depending on the engine, this might include high pressure injection pumps, pump injectors (also called unit injectors) and fuel injectors.

Applications

Biodiesel can be used in pure form (B100) or may be blended with petroleum diesel at any concentration in most injection pump diesel engines. New extreme high-pressure (29,000 psi) common rail engines have strict factory limits of B5 or B20, depending on manufacturer.[28] Biodiesel has different solvent properties from petrodiesel, and will degrade natural rubber gaskets and hoses in vehicles (mostly vehicles manufactured before 1992), although these tend to wear out naturally and most likely will have already been replaced with FKM, which is nonreactive to biodiesel. Biodiesel has been known to break down deposits of residue in the fuel lines where petrodiesel has been used.[29] As a result, fuel filters may become clogged with particulates if a quick transition to pure biodiesel is made. Therefore, it is recommended to change the fuel filters on engines and heaters shortly after first switching to a biodiesel blend.[30]

Distribution

Since the passage of the Energy Policy Act of 2005, biodiesel use has been increasing in the United States.[31] In the UK, the Renewable Transport Fuel Obligation obliges suppliers to include 5% renewable fuel in all transport fuel sold in the UK by 2010. For road diesel, this effectively means 5% biodiesel (B5).

Vehicular use and manufacturer acceptance

In 2005, Chrysler (then part of DaimlerChrysler) released the Jeep Liberty CRD diesels from the factory into the European market with 5% biodiesel blends, indicating at least partial acceptance of biodiesel as an acceptable diesel fuel additive.[32] In 2007, DaimlerChrysler indicated its intention to increase warranty coverage to 20% biodiesel blends if biofuel quality in the United States can be standardized.[33]

The Volkswagen Group has released a statement indicating that several of its vehicles are compatible with B5 and B100 made from rape seed oil and compatible with the EN 14214 standard. The use of the specified biodiesel type in its cars will not void any warranty.[34]

Mercedes Benz does not allow diesel fuels containing greater than 5% biodiesel (B5) due to concerns about "production shortcomings".[35] Any damages caused by the use of such non-approved fuels will not be covered by the Mercedes-Benz Limited Warranty.

Starting in 2004, the city of Halifax, Nova Scotia decided to update its bus system to allow the fleet of city buses to run entirely on a fish-oil based biodiesel. This caused the city some initial mechanical issues, but after several years of refining, the entire fleet had successfully been converted.[36][37][38]

In 2007, McDonald's of UK announced it would start producing biodiesel from the waste oil byproduct of its restaurants. This fuel would be used to run its fleet.[39]

The 2014 Chevy Cruze Clean Turbo Diesel, direct from the factory, will be rated for up to B20 (blend of 20% biodiesel / 80% regular diesel) biodiesel compatibility[40]

Railway usage

British train operating company Virgin Trains West Coast claimed to have run the UK's first "biodiesel train", when a Class 220 was converted to run on 80% petrodiesel and 20% biodiesel.[41][42]

The British Royal Train on 15 September 2007 completed its first ever journey run on 100% biodiesel fuel supplied by Green Fuels Ltd. Prince Charles and Green Fuels managing director James Hygate were the first passengers on a train fueled entirely by biodiesel fuel. Since 2007, the Royal Train has operated successfully on B100 (100% biodiesel).[43] A government white paper also proposed converting large portions of the UK railways to biodiesel but the proposal was subsequently dropped in favour of further electrification.[44]

Similarly, a state-owned short-line railroad in Eastern Washington ran a test of a 25% biodiesel / 75% petrodiesel blend during the summer of 2008, purchasing fuel from a biodiesel producer sited along the railroad tracks.[45] The train will be powered by biodiesel made in part from canola grown in agricultural regions through which the short line runs.

Also in 2007, Disneyland began running the park trains on B98 (98% biodiesel). The program was discontinued in 2008 due to storage issues, but in January 2009, it was announced that the park would then be running all trains on biodiesel manufactured from its own used cooking oils. This is a change from running the trains on soy-based biodiesel.[46]

In 2007, the historic Mt. Washington Cog Railway added the first biodiesel locomotive to its all-steam locomotive fleet. The fleet has climbed up the western slopes of Mount Washington in New Hampshire since 1868 with a peak vertical climb of 37.4 degrees.[47]

On 8 July 2014,[48] the then Indian Railway Minister D.V. Sadananda Gowda announced in Railway Budget that 5% bio-diesel will be used in Indian Railways' Diesel Engines.[49]

Aircraft use

A test flight has been performed by a Czech jet aircraft completely powered on biodiesel.[50] Other recent jet flights using biofuel, however, have been using other types of renewable fuels.

On November 7, 2011 United Airlines flew the world's first commercial aviation flight on a microbially derived biofuel using Solajet™, Solazyme's algae-derived renewable jet fuel. The Eco-skies Boeing 737-800 plane was fueled with 40 percent Solajet and 60 percent petroleum-derived jet fuel. The commercial Eco-skies flight 1403 departed from Houston's IAH airport at 10:30 and landed at Chicago's ORD airport at 13:03.[51]

In September 2016, the Dutch flag carrier KLM contracted AltAir Fuels to supply all KLM flights departing Los Angeles International Airport with biofuel. For the next three years, the Paramount, California-based company will pump biofuel directly to the airport from their nearby refinery.[52]

As a heating oil

Biodiesel can also be used as a heating fuel in domestic and commercial boilers, a mix of heating oil and biofuel which is standardized and taxed slightly differently from diesel fuel used for transportation. Bioheat fuel is a proprietary blend of biodiesel and traditional heating oil. Bioheat is a registered trademark of the National Biodiesel Board [NBB] and the National Oilheat Research Alliance [NORA] in the United States, and Columbia Fuels in Canada.[53] Heating biodiesel is available in various blends. ASTM 396 recognizes blends of up to 5 percent biodiesel as equivalent to pure petroleum heating oil. Blends of higher levels of up to 20% biofuel are used by many consumers. Research is underway to determine whether such blends affect performance.

Older furnaces may contain rubber parts that would be affected by biodiesel's solvent properties, but can otherwise burn biodiesel without any conversion required. Care must be taken, given that varnishes left behind by petrodiesel will be released and can clog pipes—fuel filtering and prompt filter replacement is required. Another approach is to start using biodiesel as a blend, and decreasing the petroleum proportion over time can allow the varnishes to come off more gradually and be less likely to clog. Due to biodiesel's strong solvent properties, the furnace is cleaned out and generally becomes more efficient.[54]

A law passed under Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick requires all home heating diesel in that state to be 2% biofuel by July 1, 2010, and 5% biofuel by 2013.[55] New York City has passed a similar law.

Cleaning oil spills

With 80–90% of oil spill costs invested in shoreline cleanup, there is a search for more efficient and cost-effective methods to extract oil spills from the shorelines.[56] Biodiesel has displayed its capacity to significantly dissolve crude oil, depending on the source of the fatty acids. In a laboratory setting, oiled sediments that simulated polluted shorelines were sprayed with a single coat of biodiesel and exposed to simulated tides.[57] Biodiesel is an effective solvent to oil due to its methyl ester component, which considerably lowers the viscosity of the crude oil. Additionally, it has a higher buoyancy than crude oil, which later aids in its removal. As a result, 80% of oil was removed from cobble and fine sand, 50% in coarse sand, and 30% in gravel. Once the oil is liberated from the shoreline, the oil-biodiesel mixture is manually removed from the water surface with skimmers. Any remaining mixture is easily broken down due to the high biodegradability of biodiesel, and the increased surface area exposure of the mixture.

Biodiesel in generators

In 2001, UC Riverside installed a 6-megawatt backup power system that is entirely fueled by biodiesel. Backup diesel-fueled generators allow companies to avoid damaging blackouts of critical operations at the expense of high pollution and emission rates. By using B100, these generators were able to essentially eliminate the byproducts that result in smog, ozone, and sulfur emissions.[58] The use of these generators in residential areas around schools, hospitals, and the general public result in substantial reductions in poisonous carbon monoxide and particulate matter.[59]

Fuel efficiency

The power output of biodiesel depends on its blend, quality, and load conditions under which the fuel is burnt. The thermal efficiency for example of B100 as compared to B20 will vary due to the differing energy content of the various blends. Thermal efficiency of a fuel is based in part on fuel characteristics such as: viscosity, specific density, and flash point; these characteristics will change as the blends as well as the quality of biodiesel varies. The American Society for Testing and Materials has set standards in order to judge the quality of a given fuel sample.[60]

One study found that the brake thermal efficiency of B40 was superior to traditional petroleum counterpart at higher compression ratios (this higher brake thermal efficiency was recorded at compression ratios of 21:1). It was noted that, as the compression ratios increased, the efficiency of all fuel types – as well as blends being tested – increased; though it was found that a blend of B40 was the most economical at a compression ratio of 21:1 over all other blends. The study implied that this increase in efficiency was due to fuel density, viscosity, and heating values of the fuels.[61]

Combustion

Fuel systems on some modern diesel engines were not designed to accommodate biodiesel, while many heavy duty engines are able to run with biodiesel blends up to B20.[4] Traditional direct injection fuel systems operate at roughly 3,000 psi at the injector tip while the modern common rail fuel system operates upwards of 30,000 PSI at the injector tip. Components are designed to operate at a great temperature range, from below freezing to over 1,000 °F (560 °C). Diesel fuel is expected to burn efficiently and produce as few emissions as possible. As emission standards are being introduced to diesel engines the need to control harmful emissions is being designed into the parameters of diesel engine fuel systems. The traditional inline injection system is more forgiving to poorer quality fuels as opposed to the common rail fuel system. The higher pressures and tighter tolerances of the common rail system allows for greater control over atomization and injection timing. This control of atomization as well as combustion allows for greater efficiency of modern diesel engines as well as greater control over emissions. Components within a diesel fuel system interact with the fuel in a way to ensure efficient operation of the fuel system and so the engine. If an out-of-specification fuel is introduced to a system that has specific parameters of operation, then the integrity of the overall fuel system may be compromised. Some of these parameters such as spray pattern and atomization are directly related to injection timing.[62]

One study found that during atomization, biodiesel and its blends produced droplets greater in diameter than the droplets produced by traditional petrodiesel. The smaller droplets were attributed to the lower viscosity and surface tension of traditional diesel fuel. It was found that droplets at the periphery of the spray pattern were larger in diameter than the droplets at the center. This was attributed to the faster pressure drop at the edge of the spray pattern; there was a proportional relationship between the droplet size and the distance from the injector tip. It was found that B100 had the greatest spray penetration, this was attributed to the greater density of B100.[63] Having a greater droplet size can lead to inefficiencies in the combustion, increased emissions, and decreased horse power. In another study it was found that there is a short injection delay when injecting biodiesel. This injection delay was attributed to the greater viscosity of Biodiesel. It was noted that the higher viscosity and the greater cetane rating of biodiesel over traditional petrodiesel lead to poor atomization, as well as mixture penetration with air during the ignition delay period.[64] Another study noted that this ignition delay may aid in a decrease of NOx emission.[65]

Emissions

Emissions are inherent to the combustion of diesel fuels that are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (E.P.A.). As these emissions are a byproduct of the combustion process, in order to ensure E.P.A. compliance a fuel system must be capable of controlling the combustion of fuels as well as the mitigation of emissions. There are a number of new technologies being phased in to control the production of diesel emissions. The exhaust gas recirculation system, E.G.R., and the diesel particulate filter, D.P.F., are both designed to mitigate the production of harmful emissions.[66]

A study performed by the Chonbuk National University concluded that a B30 biodiesel blend reduced carbon monoxide emissions by approximately 83% and particulate matter emissions by roughly 33%. NOx emissions, however, were found to increase without the application of an E.G.R. system. The study also concluded that, with E.G.R, a B20 biodiesel blend considerably reduced the emissions of the engine.[67] Additionally, analysis by the California Air Resources Board found that biodiesel had the lowest carbon emissions of the fuels tested, those being ultra-low-sulfur diesel, gasoline, corn-based ethanol, compressed natural gas, and five types of biodiesel from varying feedstocks. Their conclusions also showed great variance in carbon emissions of biodiesel based on the feedstock used. Of soy, tallow, canola, corn, and used cooking oil, soy showed the highest carbon emissions, while used cooking oil produced the lowest.[68]

While studying the effect of biodiesel on diesel particulate filters, it was found that though the presence of sodium and potassium carbonates aided in the catalytic conversion of ash, as the diesel particulates are catalyzed, they may congregate inside the D.P.F. and so interfere with the clearances of the filter. This may cause the filter to clog and interfere with the regeneration process.[69] In a study on the impact of E.G.R. rates with blends of jathropa biodiesel it was shown that there was a decrease in fuel efficiency and torque output due to the use of biodiesel on a diesel engine designed with an E.G.R. system. It was found that CO and CO2 emissions increased with an increase in exhaust gas recirculation but NOx levels decreased. The opacity level of the jathropa blends was in an acceptable range, where traditional diesel was out of acceptable standards. It was shown that a decrease in Nox emissions could be obtained with an E.G.R. system. This study showed an advantage over traditional diesel within a certain operating range of the E.G.R. system.[70]

As of 2017, blended biodiesel fuels (especially B5, B8, and B20) are regularly used in many heavy-duty vehicles, especially transit buses in US cities. Characterization of exhaust emissions showed significant emission reductions compared to regular diesel.[4]

Material compatibility

- Plastics: High-density polyethylene (HDPE) is compatible but polyvinyl chloride (PVC) is slowly degraded.[7] Polystyrene is dissolved on contact with biodiesel.

- Metals: Biodiesel (like methanol) has an effect on copper-based materials (e.g. brass), and it also affects zinc, tin, lead, and cast iron.[7] Stainless steels (316 and 304) and aluminum are unaffected.

- Rubber: Biodiesel also affects types of natural rubbers found in some older engine components. Studies have also found that fluorinated elastomers (FKM) cured with peroxide and base-metal oxides can be degraded when biodiesel loses its stability caused by oxidation. Commonly used synthetic rubbers FKM- GBL-S and FKM- GF-S found in modern vehicles were found to handle biodiesel in all conditions.[71]

Technical standards

Biodiesel has a number of standards for its quality including European standard EN 14214, ASTM International D6751, and National Standard of Canada CAN/CGSB-3.524.

ASTM D6751 (American Society for Testing and Materials) details standards and specifications for biodiesels blended with middle distillate fuels. This specification standard specifies various test methods to be used in the determination of certain properties for biodiesel blends. Some of the tests mentioned include flash point and kinematic viscosity.

Low temperature gelling

When biodiesel is cooled below a certain point, some of the molecules aggregate and form crystals. The fuel starts to appear cloudy once the crystals become larger than one quarter of the wavelengths of visible light – this is the cloud point (CP). As the fuel is cooled further these crystals become larger. The lowest temperature at which fuel can pass through a 45 micrometre filter is the cold filter plugging point (CFPP).[72] As biodiesel is cooled further it will gel and then solidify. Within Europe, there are differences in the CFPP requirements between countries. This is reflected in the different national standards of those countries. The temperature at which pure (B100) biodiesel starts to gel varies significantly and depends upon the mix of esters and therefore the feedstock oil used to produce the biodiesel. For example, biodiesel produced from low erucic acid varieties of canola seed (RME) starts to gel at approximately −10 °C (14 °F). Biodiesel produced from beef tallow and palm oil tends to gel at around 16 °C (61 °F) and 13 °C (55 °F) respectively.[73] There are a number of commercially available additives that will significantly lower the pour point and cold filter plugging point of pure biodiesel. Winter operation is also possible by blending biodiesel with other fuel oils including #2 low sulfur diesel fuel and #1 diesel / kerosene.

Another approach to facilitate the use of biodiesel in cold conditions is by employing a second fuel tank for biodiesel in addition to the standard diesel fuel tank. The second fuel tank can be insulated and a heating coil using engine coolant is run through the tank. The fuel tanks can be switched over when the fuel is sufficiently warm. A similar method can be used to operate diesel vehicles using straight vegetable oil.

Contamination by water

Biodiesel may contain small but problematic quantities of water. Although it is only slightly miscible with water it is hygroscopic.[74] One of the reasons biodiesel can absorb water is the persistence of mono and diglycerides left over from an incomplete reaction. These molecules can act as an emulsifier, allowing water to mix with the biodiesel. In addition, there may be water that is residual to processing or resulting from storage tank condensation. The presence of water is a problem because:

- Water reduces the heat of fuel combustion, causing smoke, harder starting, and reduced power.

- Water causes corrosion of fuel system components (pumps, fuel lines, etc.)

- Microbes in water cause the paper-element filters in the system to rot and fail, causing failure of the fuel pump due to ingestion of large particles.

- Water freezes to form ice crystals that provide sites for nucleation, accelerating gelling of the fuel.

- Water causes pitting in pistons.

Previously, the amount of water contaminating biodiesel has been difficult to measure by taking samples, since water and oil separate. However, it is now possible to measure the water content using water-in-oil sensors.[75]

Water contamination is also a potential problem when using certain chemical catalysts involved in the production process, substantially reducing catalytic efficiency of base (high pH) catalysts such as potassium hydroxide. However, the super-critical methanol production methodology, whereby the transesterification process of oil feedstock and methanol is effectuated under high temperature and pressure, has been shown to be largely unaffected by the presence of water contamination during the production phase.

Availability and prices

Global biodiesel production reached 3.8 million tons in 2005. Approximately 85% of biodiesel production came from the European Union.[76]

In 2007, in the United States, average retail (at the pump) prices, including federal and state fuel taxes, of B2/B5 were lower than petroleum diesel by about 12 cents, and B20 blends were the same as petrodiesel.[77] However, as part of a dramatic shift in diesel pricing, by July 2009, the US DOE was reporting average costs of B20 15 cents per gallon higher than petroleum diesel ($2.69/gal vs. $2.54/gal).[78] B99 and B100 generally cost more than petrodiesel except where local governments provide a tax incentive or subsidy. In the month of October 2016, Biodiesel (B20) was 2 cents lower/gallon than petrodiesel.[79]

Production

Biodiesel is commonly produced by the transesterification of the vegetable oil or animal fat feedstock, and other non-edible raw materials such as frying oil, etc. There are several methods for carrying out this transesterification reaction including the common batch process, heterogeneous catalysts,[80] supercritical processes, ultrasonic methods, and even microwave methods.

Chemically, transesterified biodiesel comprises a mix of mono-alkyl esters of long chain fatty acids. The most common form uses methanol (converted to sodium methoxide) to produce methyl esters (commonly referred to as Fatty Acid Methyl Ester – FAME) as it is the cheapest alcohol available, though ethanol can be used to produce an ethyl ester (commonly referred to as Fatty Acid Ethyl Ester – FAEE) biodiesel and higher alcohols such as isopropanol and butanol have also been used. Using alcohols of higher molecular weights improves the cold flow properties of the resulting ester, at the cost of a less efficient transesterification reaction. A lipid transesterification production process is used to convert the base oil to the desired esters. Any free fatty acids (FFAs) in the base oil are either converted to soap and removed from the process, or they are esterified (yielding more biodiesel) using an acidic catalyst. After this processing, unlike straight vegetable oil, biodiesel has combustion properties very similar to those of petroleum diesel, and can replace it in most current uses.

The methanol used in most biodiesel production processes is made using fossil fuel inputs. However, there are sources of renewable methanol made using carbon dioxide or biomass as feedstock, making their production processes free of fossil fuels.[81]

A by-product of the transesterification process is the production of glycerol. For every 1 tonne of biodiesel that is manufactured, 100 kg of glycerol are produced. Originally, there was a valuable market for the glycerol, which assisted the economics of the process as a whole. However, with the increase in global biodiesel production, the market price for this crude glycerol (containing 20% water and catalyst residues) has crashed. Research is being conducted globally to use this glycerol as a chemical building block (see chemical intermediate under Wikipedia article "Glycerol"). One initiative in the UK is The Glycerol Challenge.[82]

Usually this crude glycerol has to be purified, typically by performing vacuum distillation. This is rather energy intensive. The refined glycerol (98%+ purity) can then be utilised directly, or converted into other products. The following announcements were made in 2007: A joint venture of Ashland Inc. and Cargill announced plans to make propylene glycol in Europe from glycerol[83] and Dow Chemical announced similar plans for North America.[84] Dow also plans to build a plant in China to make epichlorhydrin from glycerol.[85] Epichlorhydrin is a raw material for epoxy resins.

Production levels

In 2007, biodiesel production capacity was growing rapidly, with an average annual growth rate from 2002 to 2006 of over 40%.[86] For the year 2006, the latest for which actual production figures could be obtained, total world biodiesel production was about 5–6 million tonnes, with 4.9 million tonnes processed in Europe (of which 2.7 million tonnes was from Germany) and most of the rest from the US. In 2008 production in Europe alone had risen to 7.8 million tonnes.[87] In July 2009, a duty was added to American imported biodiesel in the European Union in order to balance the competition from European, especially German producers.[88][89] The capacity for 2008 in Europe totalled 16 million tonnes. This compares with a total demand for diesel in the US and Europe of approximately 490 million tonnes (147 billion gallons).[90] Total world production of vegetable oil for all purposes in 2005–06 was about 110 million tonnes, with about 34 million tonnes each of palm oil and soybean oil.[91] As of 2018, Indonesia is the world's top supplier of palmoil-based biofuel with annual production of 3.5 million tons,[92][93] and expected to export about 1 million tonnes of biodiesel.[94]

US biodiesel production in 2011 brought the industry to a new milestone. Under the EPA Renewable Fuel Standard, targets have been implemented for the biodiesel production plants in order to monitor and document production levels in comparison to total demand. According to the year-end data released by the EPA, biodiesel production in 2011 reached more than 1 billion gallons. This production number far exceeded the 800 million gallon target set by the EPA. The projected production for 2020 is nearly 12 billion gallons.[95]

Biodiesel feedstocks

| Plant oils |

|---|

|

| Types |

|

| Uses |

|

| Components |

|

A variety of oils can be used to produce biodiesel. These include:

- Virgin oil feedstock – rapeseed and soybean oils are most commonly used, soybean oil [4] accounting for about half of U.S. production.[96] It also can be obtained from Pongamia, field pennycress and jatropha and other crops such as mustard, jojoba, flax, sunflower, palm oil, coconut and hemp (see list of vegetable oils for biofuel for more information);

- Waste vegetable oil (WVO);

- Animal fats including tallow, lard, yellow grease, chicken fat,[97] and the by-products of the production of Omega-3 fatty acids from fish oil.

- Algae, which can be grown using waste materials such as sewage[98] and without displacing land currently used for food production.

- Oil from halophytes such as Salicornia bigelovii, which can be grown using saltwater in coastal areas where conventional crops cannot be grown, with yields equal to the yields of soybeans and other oilseeds grown using freshwater irrigation[99]

- Sewage Sludge – The sewage-to-biofuel field is attracting interest from major companies like Waste Management and startups like InfoSpi, which are betting that renewable sewage biodiesel can become competitive with petroleum diesel on price.[100]

Many advocates suggest that waste vegetable oil is the best source of oil to produce biodiesel, but since the available supply is drastically less than the amount of petroleum-based fuel that is burned for transportation and home heating in the world, this local solution could not scale to the current rate of consumption.

Animal fats are a by-product of meat production and cooking. Although it would not be efficient to raise animals (or catch fish) simply for their fat, use of the by-product adds value to the livestock industry (hogs, cattle, poultry). Today, multi-feedstock biodiesel facilities are producing high quality animal-fat based biodiesel.[2][1] Currently, a 5-million dollar plant is being built in the US, with the intent of producing 11.4 million litres (3 million gallons) biodiesel from some of the estimated 1 billion kg (2.2 billion pounds) of chicken fat[101] produced annually at the local Tyson poultry plant.[97] Similarly, some small-scale biodiesel factories use waste fish oil as feedstock.[102][103] An EU-funded project (ENERFISH) suggests that at a Vietnamese plant to produce biodiesel from catfish (basa, also known as pangasius), an output of 13 tons/day of biodiesel can be produced from 81 tons of fish waste (in turn resulting from 130 tons of fish). This project utilises the biodiesel to fuel a CHP unit in the fish processing plant, mainly to power the fish freezing plant.[104]

Quantity of feedstocks required

Current worldwide production of vegetable oil and animal fat is not sufficient to replace liquid fossil fuel use. Furthermore, some object to the vast amount of farming and the resulting fertilization, pesticide use, and land use conversion that would be needed to produce the additional vegetable oil. The estimated transportation diesel fuel and home heating oil used in the United States is about 160 million tons (350 billion pounds) according to the Energy Information Administration, US Department of Energy.[105] In the United States, estimated production of vegetable oil for all uses is about 11 million tons (24 billion pounds) and estimated production of animal fat is 5.3 million tonnes (12 billion pounds).[106]

If the entire arable land area of the US (470 million acres, or 1.9 million square kilometers) were devoted to biodiesel production from soy, this would just about provide the 160 million tonnes required (assuming an optimistic 98 US gal/acre of biodiesel). This land area could in principle be reduced significantly using algae, if the obstacles can be overcome. The US DOE estimates that if algae fuel replaced all the petroleum fuel in the United States, it would require 15,000 square miles (39,000 square kilometers), which is a few thousand square miles larger than Maryland, or 30% greater than the area of Belgium,[107][108] assuming a yield of 140 tonnes/hectare (15,000 US gal/acre). Given a more realistic yield of 36 tonnes/hectare (3834 US gal/acre) the area required is about 152,000 square kilometers, or roughly equal to that of the state of Georgia or of England and Wales. The advantages of algae are that it can be grown on non-arable land such as deserts or in marine environments, and the potential oil yields are much higher than from plants.

Yield

Feedstock yield efficiency per unit area affects the feasibility of ramping up production to the huge industrial levels required to power a significant percentage of vehicles.

| Crop | Yield | |

|---|---|---|

| L/ha | US gal/acre | |

| Palm oil[n 1] | 4752 | 508 |

| Coconut | 2151 | 230 |

| Cyperus esculentus[n 2] | 1628 | 174 |

| Rapeseed[n 1] | 954 | 102 |

| Soy (Indiana)[109] | 554-922 | 59.2–98.6 |

| Chinese tallow[n 3][n 4] | 907 | 97 |

| Peanut[n 1] | 842 | 90 |

| Sunflower[n 1] | 767 | 82 |

| Hemp | 242 | 26 |

| ||

Algae fuel yields have not yet been accurately determined, but DOE is reported as saying that algae yield 30 times more energy per acre than land crops such as soybeans.[110] Yields of 36 tonnes/hectare are considered practical by Ami Ben-Amotz of the Institute of Oceanography in Haifa, who has been farming Algae commercially for over 20 years.[111]

Jatropha has been cited as a high-yield source of biodiesel but yields are highly dependent on climatic and soil conditions. The estimates at the low end put the yield at about 200 US gal/acre (1.5-2 tonnes per hectare) per crop; in more favorable climates two or more crops per year have been achieved.[112] It is grown in the Philippines, Mali and India, is drought-resistant, and can share space with other cash crops such as coffee, sugar, fruits and vegetables.[113] It is well-suited to semi-arid lands and can contribute to slow down desertification, according to its advocates.[114]

Efficiency and economic arguments

According to a study by Drs. Van Dyne and Raymer for the Tennessee Valley Authority, the average US farm consumes fuel at the rate of 82 litres per hectare (8.75 US gal/acre) of land to produce one crop. However, average crops of rapeseed produce oil at an average rate of 1,029 L/ha (110 US gal/acre), and high-yield rapeseed fields produce about 1,356 L/ha (145 US gal/acre). The ratio of input to output in these cases is roughly 1:12.5 and 1:16.5. Photosynthesis is known to have an efficiency rate of about 3–6% of total solar radiation[115] and if the entire mass of a crop is utilized for energy production, the overall efficiency of this chain is currently about 1%[116] While this may compare unfavorably to solar cells combined with an electric drive train, biodiesel is less costly to deploy (solar cells cost approximately US$250 per square meter) and transport (electric vehicles require batteries which currently have a much lower energy density than liquid fuels). A 2005 study found that biodiesel production using soybeans required 27% more fossil energy than the biodiesel produced and 118% more energy using sunflowers.[117]

However, these statistics by themselves are not enough to show whether such a change makes economic sense. Additional factors must be taken into account, such as: the fuel equivalent of the energy required for processing, the yield of fuel from raw oil, the return on cultivating food, the effect biodiesel will have on food prices and the relative cost of biodiesel versus petrodiesel, water pollution from farm run-off, soil depletion, and the externalized costs of political and military interference in oil-producing countries intended to control the price of petrodiesel.

The debate over the energy balance of biodiesel is ongoing. Transitioning fully to biofuels could require immense tracts of land if traditional food crops are used (although non food crops can be utilized). The problem would be especially severe for nations with large economies, since energy consumption scales with economic output.[118]

If using only traditional food plants, most such nations do not have sufficient arable land to produce biofuel for the nation's vehicles. Nations with smaller economies (hence less energy consumption) and more arable land may be in better situations, although many regions cannot afford to divert land away from food production.

For third world countries, biodiesel sources that use marginal land could make more sense; e.g., pongam oiltree nuts grown along roads or jatropha grown along rail lines.[119]

In tropical regions, such as Malaysia and Indonesia, plants that produce palm oil are being planted at a rapid pace to supply growing biodiesel demand in Europe and other markets. Scientists have shown that the removal of rainforest for palm plantations is not ecologically sound since the expansion of oil palm plantations poses a threat to natural rainforest and biodiversity.[120]

It has been estimated in Germany that palm oil diesel has less than one third of the production costs of rapeseed biodiesel.[121] The direct source of the energy content of biodiesel is solar energy captured by plants during photosynthesis. Regarding the positive energy balance of biodiesel:

- When straw was left in the field, biodiesel production was strongly energy positive, yielding 1 GJ biodiesel for every 0.561 GJ of energy input (a yield/cost ratio of 1.78).

- When straw was burned as fuel and oilseed rapemeal was used as a fertilizer, the yield/cost ratio for biodiesel production was even better (3.71). In other words, for every unit of energy input to produce biodiesel, the output was 3.71 units (the difference of 2.71 units would be from solar energy).

Economic impact

Multiple economic studies have been performed regarding the economic impact of biodiesel production. One study, commissioned by the National Biodiesel Board, reported the production of biodiesel supported more than 64,000 jobs.[95] The growth in biodiesel also helps significantly increase GDP. In 2011, biodiesel created more than $3 billion in GDP. Judging by the continued growth in the Renewable Fuel Standard and the extension of the biodiesel tax incentive, the number of jobs can increase to 50,725, $2.7 billion in income, and reaching $5 billion in GDP by 2012 and 2013.[122]

Energy security

One of the main drivers for adoption of biodiesel is energy security. This means that a nation's dependence on oil is reduced, and substituted with use of locally available sources, such as coal, gas, or renewable sources. Thus a country can benefit from adoption of biofuels, without a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. While the total energy balance is debated, it is clear that the dependence on oil is reduced. One example is the energy used to manufacture fertilizers, which could come from a variety of sources other than petroleum. The US National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) states that energy security is the number one driving force behind the US biofuels programme,[123] and a White House "Energy Security for the 21st Century" paper makes it clear that energy security is a major reason for promoting biodiesel.[124] The former EU commission president, Jose Manuel Barroso, speaking at a recent EU biofuels conference, stressed that properly managed biofuels have the potential to reinforce the EU's security of supply through diversification of energy sources.[125]

Global biofuel policies

Many countries around the world are involved in the growing use and production of biofuels, such as biodiesel, as an alternative energy source to fossil fuels and oil. To foster the biofuel industry, governments have implemented legislations and laws as incentives to reduce oil dependency and to increase the use of renewable energies.[126] Many countries have their own independent policies regarding the taxation and rebate of biodiesel use, import, and production.

Canada

It was required by the Canadian Environmental Protection Act Bill C-33 that by 2010, gasoline contained 5% renewable content and that by 2013, diesel and heating oil contained 2% renewable content.[126] The EcoENERGY for Biofuels Program subsidized the production of biodiesel, among other biofuels, via an incentive rate of CAN$0.20 per liter from 2008 to 2010. A decrease of $0.04 will be applied every year following, until the incentive rate reaches $0.06 in 2016. Individual provinces also have specific legislative measures in regards to biofuel use and production.[127]

United States

The Volumetric Ethanol Excise Tax Credit (VEETC) was the main source of financial support for biofuels, but was scheduled to expire in 2010. Through this act, biodiesel production guaranteed a tax credit of US$1 per gallon produced from virgin oils, and $0.50 per gallon made from recycled oils.[128] Currently soybean oil is being used to produce soybean biodiesel for many commercial purposes such as blending fuel for transportation sectors.[4]

European Union

The European Union is the greatest producer of biodiesel, with France and Germany being the top producers. To increase the use of biodiesel, there are policies requiring the blending of biodiesel into fuels, including penalties if those rates are not reached. In France, the goal was to reach 10% integration but plans for that stopped in 2010.[126] As an incentive for the European Union countries to continue the production of the biofuel, there are tax rebates for specific quotas of biofuel produced. In Germany, the minimum percentage of biodiesel in transport diesel is set at 7% so called "B7".

Malaysia

Malaysia plans to implement its nationwide adoption of the B20 palm oil biofuel programme by the end of 2022. The mandate to manufacture biofuel with a 20% palm oil component - known as B20 - for the transport sector was first rolled out in January 2020 but faced delays due to movement curbs imposed to contain coronavirus outbreaks.[129]

Environmental effects

The surge of interest in biodiesels has highlighted a number of environmental effects associated with its use. These potentially include reductions in greenhouse gas emissions,[130] deforestation, pollution and the rate of biodegradation.

According to the Renewable Fuel Standards Program Regulatory Impact Analysis, released by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) of the United States in February 2010, biodiesel from soy oil results, on average, in a 57% reduction in greenhouse gases compared to petroleum diesel, and biodiesel produced from waste grease results in an 86% reduction. See chapter 2.6 of the EPA report for more detailed information.

However, environmental organizations, for example, Rainforest Rescue[131] and Greenpeace,[132] criticize the cultivation of plants used for biodiesel production, e.g., oil palms, soybeans and sugar cane. The deforestation of rainforests exacerbates climate change and sensitive ecosystems are destroyed to clear land for oil palm, soybean and sugar cane plantations. Moreover, that biofuels contribute to world hunger, since arable land is no longer used for growing foods. The Environmental Protection Agency published data in January 2012, showing that biofuels made from palm oil will not count towards the renewable fuels mandate of the United States as they are not climate-friendly.[133] Environmentalists welcome the conclusion because the growth of oil palm plantations has driven tropical deforestation, for example, in Indonesia and Malaysia.[133][134]

Indonesia produces biodiesel primarily from palm oil. Since agricultural land is limited, in order to plant monocultures of oil palms, land used for other cultivations or the tropical forest need to be cleared. A major environmental threat is then the destruction of rainforests in Indonesia.[135]

Food, land and water vs. fuel

Up to 40% of corn produced in the United States is used to make ethanol,[136] and worldwide 10% of all grain is turned into biofuel.[137] A 50% reduction in grain used for biofuels in the US and Europe would replace all of Ukraine's grain exports.[138]

In some poor countries the rising price of vegetable oil is causing problems.[139][140] Some propose that fuel only be made from non-edible vegetable oils such as camelina, jatropha or seashore mallow[141] which can thrive on marginal agricultural land where many trees and crops will not grow, or would produce only low yields.

Others argue that the problem is more fundamental. Farmers may switch from producing food crops to producing biofuel crops to make more money, even if the new crops are not edible.[142][143] The law of supply and demand predicts that if fewer farmers are producing food the price of food will rise. It may take some time, as farmers can take some time to change which things they are growing, but increasing demand for first generation biofuels is likely to result in price increases for many kinds of food. Some have pointed out that there are poor farmers and poor countries who are making more money because of the higher price of vegetable oil.[144]

Biodiesel from sea algae would not necessarily displace terrestrial land currently used for food production and new algaculture jobs could be created.

By comparison it should be mentioned that the production of biogas utilizes agricultural waste to generate a biofuel known as biogas, and also produces compost, thereby enhancing agriculture, sustainability and food production.

Current research

There is ongoing research into finding more suitable crops and improving oil yield. Other sources are possible including human fecal matter, with Ghana building its first "fecal sludge-fed biodiesel plant."[145] Using the current yields, vast amounts of land and fresh water would be needed to produce enough oil to completely replace fossil fuel usage. It would require twice the land area of the US to be devoted to soybean production, or two-thirds to be devoted to rapeseed production, to meet current US heating and transportation needs.

Specially bred mustard varieties can produce reasonably high oil yields and are very useful in crop rotation with cereals, and have the added benefit that the meal leftover after the oil has been pressed out can act as an effective and biodegradable pesticide.[146]

The NFESC, with Santa Barbara-based Biodiesel Industries is working to develop biodiesel technologies for the US navy and military, one of the largest diesel fuel users in the world.[147]

A group of Spanish developers working for a company called Ecofasa announced a new biofuel made from trash. The fuel is created from general urban waste which is treated by bacteria to produce fatty acids, which can be used to make biodiesel.[148]

Another approach that does not require the use of chemical for the production involves the use of genetically modified microbes.[149][150]

Algal biodiesel

From 1978 to 1996, the U.S. NREL experimented with using algae as a biodiesel source in the "Aquatic Species Program".[123] A self-published article by Michael Briggs, at the UNH Biodiesel Group, offers estimates for the realistic replacement of all vehicular fuel with biodiesel by utilizing algae that have a natural oil content greater than 50%, which Briggs suggests can be grown on algae ponds at wastewater treatment plants.[108] This oil-rich algae can then be extracted from the system and processed into biodiesel, with the dried remainder further reprocessed to create ethanol.

The production of algae to harvest oil for biodiesel has not yet been undertaken on a commercial scale, but feasibility studies have been conducted to arrive at the above yield estimate. In addition to its projected high yield, algaculture — unlike crop-based biofuels — does not entail a decrease in food production, since it requires neither farmland nor fresh water. Many companies are pursuing algae bio-reactors for various purposes, including scaling up biodiesel production to commercial levels.[151][152] Biodiesel lipids could be extracted from wet algae using a simple and economical reaction in ionic liquids.[153]

Pongamia

Millettia pinnata, also known as the Pongam Oiltree or Pongamia, is a leguminous, oilseed-bearing tree that has been identified as a candidate for non-edible vegetable oil production.

Pongamia plantations for biodiesel production have a two-fold environmental benefit. The trees both store carbon and produce fuel oil. Pongamia grows on marginal land not fit for food crops and does not require nitrate fertilizers. The oil producing tree has the highest yield of oil producing plant (approximately 40% by weight of the seed is oil) while growing in malnourished soils with high levels of salt. It is becoming a main focus in a number of biodiesel research organizations.[154] The main advantages of Pongamia are a higher recovery and quality of oil than other crops and no direct competition with food crops. However, growth on marginal land can lead to lower oil yields which could cause competition with food crops for better soil.

Jatropha

Several groups in various sectors are conducting research on Jatropha curcas, a poisonous shrub-like tree that produces seeds considered by many to be a viable source of biodiesel feedstock oil.[155] Much of this research focuses on improving the overall per acre oil yield of Jatropha through advancements in genetics, soil science, and horticultural practices.

SG Biofuels, a San Diego-based Jatropha developer, has used molecular breeding and biotechnology to produce elite hybrid seeds of Jatropha that show significant yield improvements over first generation varieties.[156] SG Biofuels also claims that additional benefits have arisen from such strains, including improved flowering synchronicity, higher resistance to pests and disease, and increased cold weather tolerance.[157]

Plant Research International, a department of the Wageningen University and Research Centre in the Netherlands, maintains an ongoing Jatropha Evaluation Project (JEP) that examines the feasibility of large scale Jatropha cultivation through field and laboratory experiments.[158]

The Center for Sustainable Energy Farming (CfSEF) is a Los Angeles-based non-profit research organization dedicated to Jatropha research in the areas of plant science, agronomy, and horticulture. Successful exploration of these disciplines is projected to increase Jatropha farm production yields by 200–300% in the next ten years.[159]

FOG from sewage

So-called fats, oils and grease (FOG), recovered from sewage can also be turned into biodiesel.[160]

Fungi

A group at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow published a paper in September 2008, stating that they had isolated large amounts of lipids from single-celled fungi and turned it into biodiesel in an economically efficient manner. More research on this fungal species; Cunninghamella japonica, and others, is likely to appear in the near future.[161]

The recent discovery of a variant of the fungus Gliocladium roseum points toward the production of so-called myco-diesel from cellulose. This organism was recently discovered in the rainforests of northern Patagonia and has the unique capability of converting cellulose into medium length hydrocarbons typically found in diesel fuel.[162]

Biodiesel from used coffee grounds

Researchers at the University of Nevada, Reno, have successfully produced biodiesel from oil derived from used coffee grounds. Their analysis of the used grounds showed a 10% to 15% oil content (by weight). Once the oil was extracted, it underwent conventional processing into biodiesel. It is estimated that finished biodiesel could be produced for about one US dollar per gallon. Further, it was reported that "the technique is not difficult" and that "there is so much coffee around that several hundred million gallons of biodiesel could potentially be made annually." However, even if all the coffee grounds in the world were used to make fuel, the amount produced would be less than 1 percent of the diesel used in the United States annually. "It won’t solve the world’s energy problem," Dr. Misra said of his work.[163]

Exotic sources

Recently, alligator fat was identified as a source to produce biodiesel. Every year, about 15 million pounds of alligator fat are disposed of in landfills as a waste byproduct of the alligator meat and skin industry. Studies have shown that biodiesel produced from alligator fat is similar in composition to biodiesel created from soybeans, and is cheaper to refine since it is primarily a waste product.[164]

Biodiesel to hydrogen-cell power

A microreactor has been developed to convert biodiesel into hydrogen steam to power fuel cells.[165]

Steam reforming, also known as fossil fuel reforming is a process which produces hydrogen gas from hydrocarbon fuels, most notably biodiesel due to its efficiency. A **microreactor**, or reformer, is the processing device in which water vapour reacts with the liquid fuel under high temperature and pressure. Under temperatures ranging from 700 – 1100 °C, a nickel-based catalyst enables the production of carbon monoxide and hydrogen:[166]

Hydrocarbon + H

2O ⇌ CO + 3H

2 (Highly endothermic)

Furthermore, a higher yield of hydrogen gas can be harnessed by further oxidizing carbon monoxide to produce more hydrogen and carbon dioxide:

CO + H

2O → CO2 + H

2 (Mildly exothermic)

Hydrogen fuel cells background information

Fuel cells operate similar to a battery in that electricity is harnessed from chemical reactions. The difference in fuel cells when compared to batteries is their ability to be powered by the constant flow of hydrogen found in the atmosphere. Furthermore, they produce only water as a by-product, and are virtually silent. The downside of hydrogen powered fuel cells is the high cost and dangers of storing highly combustible hydrogen under pressure.[167]

One way new processors can overcome the dangers of transporting hydrogen is to produce it as necessary. The microreactors can be joined to create a system that heats the hydrocarbon under high pressure to generate hydrogen gas and carbon dioxide, a process called steam reforming. This produces up to 160 gallons of hydrogen/minute and gives the potential of powering hydrogen refueling stations, or even an on-board hydrogen fuel source for hydrogen cell vehicles.[168] Implementation into cars would allow energy-rich fuels, such as biodiesel, to be transferred to kinetic energy while avoiding combustion and pollutant byproducts. The hand-sized square piece of metal contains microscopic channels with catalytic sites, which continuously convert biodiesel, and even its glycerol byproduct, to hydrogen.[169]

Safflower oil

As of 2020, researchers at Australia's CSIRO have been studying safflower oil from a specially-bred variety as an engine lubricant, and researchers at Montana State University's Advanced Fuel Centre in the US have been studying the oil's performance in a large diesel engine, with results described as a "game-changer".[170]

Concerns

Engine wear

Lubricity of fuel plays an important role in wear that occurs in an engine. A diesel engine relies on its fuel to provide lubricity for the metal components that are constantly in contact with each other.[171] Biodiesel is a much better lubricant compared with fossil petroleum diesel due to the presence of esters. Tests have shown that the addition of a small amount of biodiesel to diesel can significantly increase the lubricity of the fuel in short term.[172] However, over a longer period of time (2–4 years), studies show that biodiesel loses its lubricity.[173] This could be because of enhanced corrosion over time due to oxidation of the unsaturated molecules or increased water content in biodiesel from moisture absorption.[59]

Fuel viscosity

One of the main concerns regarding biodiesel is its viscosity. The viscosity of diesel is 2.5–3.2 cSt at 40 °C and the viscosity of biodiesel made from soybean oil is between 4.2 and 4.6 cSt[174] The viscosity of diesel must be high enough to provide sufficient lubrication for the engine parts but low enough to flow at operational temperature. High viscosity can plug the fuel filter and injection system in engines.[174] Vegetable oil is composed of lipids with long chains of hydrocarbons, to reduce its viscosity the lipids are broken down into smaller molecules of esters. This is done by converting vegetable oil and animal fats into alkyl esters using transesterification to reduce their viscosity[175] Nevertheless, biodiesel viscosity remains higher than that of diesel, and the engine may not be able to use the fuel at low temperatures due to the slow flow through the fuel filter.[176]

Engine performance

Biodiesel has higher brake-specific fuel consumption compared to diesel, which means more biodiesel fuel consumption is required for the same torque. However, B20 biodiesel blend has been found to provide maximum increase in thermal efficiency, lowest brake-specific energy consumption, and lower harmful emissions.[4][59][171] The engine performance depends on the properties of the fuel, as well as on combustion, injector pressure and many other factors.[177] Since there are various blends of biodiesel, that may account for the contradicting reports as regards engine performance.

See also

- Civic amenity site; collection point for WVO

- EcoJet concept car

- Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008

- Fuel (film)

- Gasoline gallon equivalent

- Indirect land use change impacts of biofuels

- MY Ady Gil

- Sustainable biofuel

- Table of biofuel crop yields

- Tonne of oil equivalent

- United States vs. Imperial Petroleum

- Vegetable oil economy

- Vegetable oil fuel

![]() Environment portal

Environment portal

![]() Renewable Energy portal

Renewable Energy portal

References

- "AustraliaBiofuels.pdf (application/pdf Object)" (PDF). bioenergy.org.nz. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- "Monthly_US_Raw_Material_Useage_for_US_Biodiesel_Production_2007_2009.pdf (application/pdf Object)" (PDF). assets.nationalrenderers.org. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2012.

- Costa, Gustavo GL; Cardoso, Kiara C.; Del Bem, Luiz EV; Lima, Aline C.; Cunha, Muciana AS; de Campos-Leite, Luciana; Vicentini, Renato; Papes, Fábio; Moreira, Raquel C.; Yunes, José A.; Campos, Francisco AP (2010-08-06). "Transcriptome analysis of the oil-rich seed of the bioenergy crop Jatropha curcas L". BMC Genomics. 11 (1): 462. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-462. ISSN 1471-2164. PMC 3091658. PMID 20691070.

- Omidvarborna; et al. (December 2014). "Characterization of particulate matter emitted from transit buses fueled with B20 in idle modes". Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering. 2 (4): 2335–2342. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2014.09.020.

- "Nylund.N-O & Koponen.K. 2013. Fuel and Technology Alternatives for Buses. Overall Energy Efficiency and Emission Performance. IEA Bioenergy Task 46" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-02-16. Retrieved 2021-04-18.

- "Biodiesel Basics" (?). National Biodiesel Board. Archived from the original on 2014-08-04. Retrieved 2013-01-29.

- "Biodiesel Basics - Biodiesel.org". biodiesel.org. 2012. Archived from the original on August 4, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- "Biodiesel Handling and Use Guide, Fourth Edition" (PDF). National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-11-10. Retrieved 2011-02-13.

- "American Society for Testing and Materials". ASTM International. Archived from the original on 2019-12-08. Retrieved 2011-02-13.

- "Biodiesel Handling and Use Guide" (PDF). nrel.gov. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 28, 2011. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- Duffy, Patrick (1853). "XXV. On the constitution of stearine". Quarterly Journal of the Chemical Society of London. 5 (4): 303. doi:10.1039/QJ8530500303. Archived from the original on 2020-07-26. Retrieved 2019-07-05.

- Rob (1898). "Über partielle Verseifung von Ölen und Fetten II". Zeitschrift für Angewandte Chemie. 11 (30): 697–702. Bibcode:1898AngCh..11..697H. doi:10.1002/ange.18980113003. Archived from the original on 2020-07-26. Retrieved 2019-07-05.

- "Biodiesel Day". Days Of The Year. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- The Biodiesel Handbook, Chapter 2 – The History of Vegetable Oil Based Diesel Fuels, by Gerhard Knothe, ISBN 978-1-893997-79-0

- Knothe, G. "Historical Perspectives on Vegetable Oil-Based Diesel Fuels" (PDF). INFORM, Vol. 12(11), p. 1103-1107 (2001). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-10-04. Retrieved 2007-07-11.

- "Lipofuels: Biodiesel and Biokerosene" (PDF). www.nist.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-03-18. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- Quote from Tecbio website Archived October 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "O Globo newspaper interview in Portuguese". Defesanet.com.br. Archived from the original on 2010-10-29. Retrieved 2010-03-15.

- SAE Technical Paper series no. 831356. SAE International Off Highway Meeting, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA, 1983

- "Generic biodiesel material safety data sheet (MSDS)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-12-22. Retrieved 2010-03-15.

- "MSDS ID NO.: 0301MAR019" (PDF). Marathon Petroleum. 7 December 2010. pp. 5, 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-12-22. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- "Safety Data Sheet - CITGO No. 2 Diesel Fuel, Low Sulfur, All Grades" (PDF). CITGO. 29 July 2015. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- Carbon and Energy Balances for a Range of Biofuels Options Sheffield Hallam University

- National Biodiesel Board (October 2005). Energy Content (PDF). Jefferson City, USA. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-27. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- UNH Biodiesel Group Archived September 6, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- "E48_MacDonald.pdf (application/pdf Object)" (PDF). astm.org. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 20, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- "Biodiesel" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2017-12-22.

- "OEM Statement Summary Chart Archived 2016-04-07 at the Library of Congress Web Archives." Biodiesel.org. National Biodiesel Board, 1 Dec. 2014. Web. 19 Nov. 2015.

- McCormick, R.L. "2006 Biodiesel Handling and Use Guide Third Edition" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-12-16. Retrieved 2006-12-18.

- "US EPA Biodiesel Factsheet". 2016-03-03. Archived from the original on July 26, 2008.

- "Twenty In Ten: Strengthening America's Energy Security". Whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on 2009-09-06. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- Kemp, William. Biodiesel: Basics and Beyond. Canada: Aztext Press, 2006.

- "National Biodiesel Board, 2007. Chrysler Supports Biodiesel Industry; Encourages Farmers, Refiners, Retailers and Customers to Drive New Diesels Running on Renewable Fuel". Nbb.grassroots.com. 2007-09-24. Archived from the original on 2010-03-06. Retrieved 2010-03-15.

- "Biodiesel statement" (PDF). Volkswagen.co.uk. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-08-04.

- "biodiesel_Brochure5.pdf (application/pdf Object)" (PDF). mbusa.com. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 28, 2012. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- "Halifax City Buses to Run on Biodiesel Again | Biodiesel and Ethanol Investing". Biodieselinvesting.com. 2006-08-31. Archived from the original on 2006-10-18. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

- "Biodiesel". Halifax.ca. Archived from the original on 2010-12-24. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

- "Halifax Transit". Halifax.ca. 2004-10-12. Archived from the original on 2014-08-14. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

- "McDonald's bolsters "green" credentials with recycled biodiesel oil". News.mongabay.com. 2007-07-09. Archived from the original on 2012-07-15. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

- "Cruze Clean Turbo Diesel Delivers Efficient Performance". 2013-02-07. Archived from the original on 2013-08-10. Retrieved 2013-08-05.

- "First UK biodiesel train launched". BBC. 2007-06-07. Archived from the original on 2008-02-13. Retrieved 2007-11-17.

- Virgin launches trials with Britain's first biofuel train Rail issue 568 20 June 2007 page 6

- "EWS Railway – News Room". www.ews-railway.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2020-02-19. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons. Transport Committee (2008). Delivering a sustainable railway : a 30-year strategy for the railways? : tenth report of session 2007-08 : report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence. London: Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-215-52222-1. OCLC 273500097. Archived from the original on 2021-07-31. Retrieved 2021-07-07.

- Vestal, Shawn (2008-06-22). "Biodiesel will drive Eastern Wa. train during summerlong test". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 2009-02-02. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- "Disneyland trains running on biodiesel - UPI.com". www.upi.com. Archived from the original on 2009-01-30. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- Kotrba, Ron (29 May 2013). "'Name that Biodiesel Train' contest". Biodiesel Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- PTI (2014-07-08). "Railway Budget 2014–15: Highlights". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- "Indian Railways to go for Bio-Diesel in a Big Way – Gowda". Archived from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- Archived April 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Solazyme | Solazyme Announces First U.S. Commercial Passenger Flight on Advanced Biofuel Archived 2013-02-06 at the Wayback Machine

- "KLM to operate biofuel flights out of Los Angeles". Archived from the original on 2017-08-04. Retrieved 2017-08-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Environment, consumers win with Bioheat trademark victory". biodieselmagazine.com. 2011. Archived from the original on November 20, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- "The Massachusetts Bioheat Fuel Pilot Program" (PDF). June 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 2012-12-31. Prepared for the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs

- Massachusetts Oil Heat Council (27 February 2008). MA Oilheat Council Endorses BioHeat Mandate Archived May 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- French McCay, D.; Rowe, J. J.; Whittier, N.; Sankaranarayanan, S.; Schmidt Etkin, D. (2004). "Estimation of potential impacts and natural resource damages of oil". J. Hazard. Mater. 107 (1–2): 11–25. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2003.11.013. PMID 15036639.

- Fernández-Ãlvarez, P.; Vila, J.; Garrido, J. M.; Grifoll, M.; Feijoo, G.; Lema, J. M. (2007). "Evaluation of biodiesel as bioremediation agent for the treatment of the shore affected by the heavy oil spill of the Prestige". J. Hazard. Mater. 147 (3): 914–922. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.01.135. PMID 17360115.

- National Biodiesel Board Electrical Generation. http://www.biodiesel.org/using-biodiesel/market-segments/electrical-generation Archived 2013-04-10 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 20 January 2013)

- Monyem, A.; Van Gerpen, J. (2001). "The effect of biodiesel oxidation on engine performance and emissions". Biomass Bioenergy. 20 (4): 317–325. doi:10.1016/s0961-9534(00)00095-7. Archived from the original on 2018-01-09. Retrieved 2018-11-22.

- ASTM Standard D6751-12, 2003, "Standard Specification for Biodiesel Fuel Blend Stock (B100) for Middle Distillate Fuels," ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2003, doi:10.1520/C0033-03, astm.org.

- Muralidharan, K. K.; Vasudevan, D. D. (2011). "Performance, emission and combustion characteristics of a variable compression ratio engine using methyl esters of waste cooking oil and diesel blends". Applied Energy. 88 (11): 3959–3968. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2011.04.014.

- Roy, Murari Mohon (2009). "Effect of Fuel Injection Timing and Injection Pressure on Combustion and Odorous Emissions in DI Diesel Engines". Journal of Energy Resources Technology. 131 (3): 032201. doi:10.1115/1.3185346.

- Chen, P.; Wang, W.; Roberts, W. L.; Fang, T. (2013). "Spray and atomization of diesel fuel and its alternatives from a single-hole injector using a common rail fuel injection system". Fuel. 103: 850–861. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2012.08.013.

- Hwang, J.; Qi, D.; Jung, Y.; Bae, C. (2014). "Effect of injection parameters on the combustion and emission characteristics in a common-rail direct injection diesel engine fueled with waste cooking oil biodiesel". Renewable Energy. 63: 639–17. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2013.08.051.

- McCarthy, P. P.; Rasul, M. G.; Moazzem, S. S. (2011). "Analysis and comparison of performance and emissions of an internal combustion engine fuelled with petroleum diesel and different bio-diesels". Fuel. 90 (6): 2147–2157. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2011.02.010.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2014, April 9). National Clean Diesel Campaign. Retrieved From the Environmental Protection Agency website: http://www.epa.gov/diesel/ Archived 2014-04-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Sam, Yoon Ki, et al. "Effects Of Canola Oil Biodiesel Fuel Blends On Combustion, Performance, And Emissions Reduction In A Common Rail Diesel Engine." Energies (19961073) 7.12 (2014): 8132–8149. Academic Search Complete. Web. 14 Nov. 2015.

- Robinson, Jessica (September 28, 2015). "Nation's strictest regulatory board affirms biodiesel as lowest-carbon fuel". National Biodiesel Board. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017.

- Hansen, B.; Jensen, A.; Jensen, P. (2013). "Performance of diesel particulate filter catalysts in the presence of biodiesel ash species" (PDF). Fuel. 106: 234–240. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2012.11.038.

- Gomaa, M. M.; Alimin, A. J.; Kamarudin, K. A. (2011). "The effect of EGR rates on NOX and smoke emissions of an IDI diesel engine fuelled with Jatropha biodiesel blends". International Journal of Energy & Environment. 2 (3): 477–490.

- Fluoroelastomer Compatibility with Biodiesel Fuels Archived 2014-10-06 at the Wayback Machine Eric W. Thomas, Robert E. Fuller and Kenji Terauchi DuPont Performance Elastomers L.L.C. January 2007

- 袁明豪; 陳奕宏 (2017-01-12). 蔡美瑛 (ed.). "生質柴油的冰與火之歌" (in Chinese). Taiwan: Ministry of Science and Technology. Archived from the original on 2021-03-22. Retrieved 2017-06-22.

- Sanford, S.D., et al., "Feedstock and Biodiesel Characteristics Report," Renewable Energy Group, Inc., www.regfuel.com (2009).

- UFOP – Union zur Förderung von Oel. "Biodiesel FlowerPower: Facts * Arguments * Tips" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-07-14. Retrieved 2007-06-13.

- "Detecting and Controlling Water in Oil". Archived from the original on 2016-10-24. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- Dasmohapatra, Gourkrishna. Engineering Chemistry I (WBUT), 3rd Edition. ISBN 9789325960039. Archived from the original on 2020-04-03. Retrieved 2017-01-13.

- "Clean Cities Alternative Fuel Price Report July 2007" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-09-10. Retrieved 2010-03-15.