Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Baton Rouge (/ˌbætən ˈruːʒ/ BAT-ən ROOZH; from French Bâton-Rouge 'red stick') is the capital of the U.S. state of Louisiana. On the eastern bank of the Mississippi River, it is the parish seat of East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana's most populous parish. Since 2020, it has been the 99th-most-populous city in the United States and the second-largest city in Louisiana, after New Orleans. It is the 18th-most-populous state capital. At the U.S. Census Bureau's 2020 tabulation,[3] it had a population of 227,470; its consolidated population was 456,781 in 2020.[4] It is the center of the Greater Baton Rouge area, Louisiana's second-largest metropolitan area, with a population of 870,569 as of 2020,[5] up from 802,484 in 2010.[6]

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

| |

|---|---|

State capital city and Consolidated city-parish | |

| City of Baton Rouge | |

From top, left to right: Downtown, Memorial Tower at LSU, USS Kidd, Louisiana State Capitol, St. Joseph Cathedral, Horace Wilkinson Bridge, Tiger Stadium (LSU), Old Louisiana State Capitol | |

Flag  Seal  Wordmark | |

| Nicknames: Red Stick, The Capital City, B.R. | |

Interactive map of Baton Rouge | |

| Coordinates: 30°26′51″N 91°10′43″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Louisiana |

| Parish | East Baton Rouge |

| Founded | 1699 |

| Settled | 1721 |

| Incorporated | January 16, 1817 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor-President | Sharon Weston Broome[1] (D) |

| Area | |

| • State capital city and Consolidated city-parish | 88.52 sq mi (229.27 km2) |

| • Land | 86.32 sq mi (223.56 km2) |

| • Water | 2.20 sq mi (5.71 km2) |

| • Total[note 1] | 79.11 sq mi (204.89 km2) |

| Elevation | 56 ft (17 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • State capital city and Consolidated city-parish | 227,470 |

| • Rank | US: 99th |

| • Density | 2,635.32/sq mi (1,017.50/km2) |

| • Urban | 594,309 (US: 68th) |

| • Metro | 870,569 |

| Demonym | Baton Rougean |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 70801–70817, 70819–70823, 70825–70827, 70831, 70833, 70835–70837, 70874, 70879, 70883, 70884, 70892–70896, 70898 |

| Area code | 225 |

| FIPS code | 22-05000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1629914 |

| Interstate highways | |

| U.S. routes | |

| Website | www |

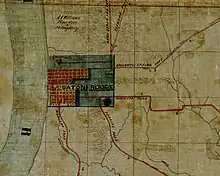

The Baton Rouge area owes its historical importance to its strategic site upon the Istrouma Bluff, the first natural bluff upriver from the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. This allowed development of a business quarter safe from seasonal flooding. In addition, it built a levee system stretching from the bluff southward to protect the riverfront and low-lying agricultural areas.[7] It is a culturally rich center, with settlement by immigrants from numerous European nations and African peoples brought to North America as slaves or indentured servants. It was ruled by seven different governments: French, British, and Spanish in the colonial era; the Republic of West Florida, as a United States territory and state, Confederate, and United States again since the end of the American Civil War.

Baton Rouge is a major industrial, petrochemical, medical, research, motion picture,[8] and growing technology center of the American South.[9] It is the location of Louisiana State University, the LSU system's flagship university and the state's largest institution of higher education.[10] It is also the location of Southern University, the flagship institution of the Southern University System, the nation's only historically black college system. The Port of Greater Baton Rouge is the 10th-largest in the U.S. by tonnage shipped, and is the farthest upstream Mississippi River port capable of handling Panamax ships.[11][12] Major corporations participating in the Baton Rouge metropolitan statistical area's economy include Lamar Advertising Company, BBQGuys, Marucci Sports, Piccadilly Restaurants, Raising Cane's Chicken Fingers, ExxonMobil, Brown & Root, Shell Chemical Company and Dow Chemical Company.

History

Prehistory

Human habitation in the Baton Rouge area has been dated to 12000–6500 BC, based on evidence found along the Mississippi, Comite, and Amite rivers.[13][14] Earthwork mounds were built by hunter-gatherer societies in the Middle Archaic period, from roughly the fourth millennium BC.[15] The speakers of the Proto-Muskogean language divided into its descendant languages by about 1000 BC; and a cultural boundary between either side of Mobile Bay and the Black Warrior River began to appear between about 1200 BC and 500 BC, a period called the Middle "Gulf Formational Stage". The Eastern Muskogean language began to diversify internally in the first half of the first millennium AD.[16]

The early Muskogean societies were the bearers of the Mississippian culture, which formed around 800 AD and extended in a vast network across the Mississippi and Ohio valleys, with numerous chiefdoms in the Southeast, as well. By the time the Spanish made their first forays inland from the shores of the Gulf of Mexico in the early 16th century, by some evidence many political centers of the Mississippians were already in decline, or abandoned. At the time, this region appeared to have been occupied by a collection of moderately sized native chiefdoms, interspersed with autonomous villages and tribal groups.[17] Other evidence indicates these Mississippian settlements were thriving at the time of the first Spanish contact. Later Spanish expeditions encountered the remains of groups who had lost many people and been disrupted in the aftermath of infectious diseases, chronic among Europeans, unknowingly introduced by the first expedition.

Colonial period

French explorer Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville led an exploration party up the Mississippi River in 1698. The explorers saw a red pole marking the boundary between the Houma and Bayagoula tribal hunting grounds. The French name le bâton rouge ("the red stick") is the translation of a native term rendered as Istrouma, possibly a corruption of the Choctaw iti humma ("red pole");[18] André-Joseph Pénicaut, a carpenter traveling with d'Iberville, published the first full-length account of the expedition in 1723. According to Pénicaut:

From there [Manchacq] we went five leagues higher and found very high banks called écorts in that region, and in savage called Istrouma which means red stick [bâton rouge], as at this place there is a post painted red that the savages have sunk there to mark the land line between the two nations, namely: the land of the Bayagoulas which they were leaving and the land of another nation—thirty leagues upstream from the baton rouge—named the Oumas.

The red pole was presumably at Scott's Bluff, on what is now the campus of Southern University.[19] It was reportedly a 30-foot-high (9.1 m) painted pole adorned with fish bones.[20]

European settlement of Baton Rouge began in 1721 when French colonists established a military and trading post. Since then, Baton Rouge has been governed by France, Britain, Spain, Louisiana, the Republic of West Florida, the United States, the Confederate States, and the United States again. In 1755, when French-speaking settlers of Acadia in Canada's Maritime provinces were expelled by British forces, many took up residence in rural Louisiana. Popularly known as Cajuns, the descendants of the Acadians maintained a separate culture. During the first half of the 19th century, Baton Rouge grew steadily as the result of steamboat trade and transportation.

Modern history

Baton Rouge was incorporated in 1817. In 1822, the Pentagon Barracks complex of buildings was completed. The site has been used by the Spanish, French, British, Confederate States Army, and United States Army and was part of the short-lived Republic of West Florida.[21] In 1951, ownership of the barracks was transferred to the state of Louisiana. In 1976, the complex was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[22]

Acquisition of Louisiana by the United States in 1803 was a catalyst for increased Anglo-American settlement, especially in the northern part of the state. In 1846, the state legislature designated Baton Rouge as Louisiana's new capital to replace "sinful" New Orleans. The architect James Dakin was hired to design the old Louisiana State Capitol, with construction beginning in late 1847.[19] Rather than mimic the United States Capitol, as many other states had done, he designed a capitol in Neo-Gothic style, complete with turrets and crenellations, and stained glass; it overlooks the Mississippi. It has been described as the "most distinguished example of Gothic Revival" architecture in the state and has been designated as a National Historic Landmark.[23]

By the outbreak of the American Civil War, the population of Baton Rouge was nearly 5,500. The war nearly halted economic progress, except for businesses associated with supplying the Union Army occupation of the city, which began in the spring of 1862 and lasted for the duration of the war. The Confederates at first consolidated their forces elsewhere, during which time the state government moved to Opelousas and later Shreveport.[19] In the summer of 1862, about 2,600 Confederate troops under generals John C. Breckinridge (the former Vice President of the United States) and Daniel Ruggles attempted to recapture Baton Rouge.

After the war, New Orleans temporarily served as the seat of the Reconstruction era state government. When the Bourbon Democrats regained power in 1882, after considerable intimidation and voter suppression of black Republicans, they returned the state government to Baton Rouge, where it has since remained. In his 1893 guidebook, Karl Baedeker described Baton Rouge as "the Capital of Louisiana, a quaint old place with 10,378 inhabitants, on a bluff above the Mississippi".[24]

In the 1950s and 1960s, the petrochemical industry boomed in Baton Rouge, stimulating the city's expansion beyond its original center. The changing market in the oil business has produced fluctuations in the industry, affecting employment in the city and area.

A building boom began in the city in the 1990s and continued into the 2000s, during which Baton Rouge was one of the fastest-growing cities in the South in terms of technology.[25] Metropolitan Baton Rouge was ranked as one of the fastest-growing metropolitan areas in the U.S. (with a population under 1 million), with 602,894 in 2000 and 802,484 people as of the 2010 U.S. census.[26] After the extensive damage in New Orleans and along the coast from Hurricane Katrina on August 29, 2005, the city took in as many as 200,000 displaced residents.

In 2010, Baton Rouge started a market push to become a test city for Google's new super high speed fiber optic line known as GeauxFiBR.[27]

In 2016, the Greater Baton Rouge metropolitan area was heavily affected by the shooting of police officers in July and flooding in August.

Geography

Baton Rouge is on the banks of the Mississippi River in southeastern Louisiana's Florida Parishes region.[28] The city is about 79 miles (127 km) from New Orleans,[29] 126 miles (203 km) from Alexandria,[30] 56 miles (90 km) from Lafayette and 250 miles (400 km) from Shreveport.[31] It is also 173 miles (278 km) from Jackson, Mississippi and 272 miles (438 km) from Houston, Texas.[32][33] Baton Rouge lies on a low elevation of 56 to a little over 62 feet above sea level.[34]

Baton Rouge is the capital of Louisiana and the parish seat of East Baton Rouge Parish. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 79.15 square miles (205.0 km2), of which 76.95 square miles (199.3 km2) are land and 2.2 square miles (5.7 km2) (2.81%) are covered by water.[35] The city is on the first set of bluffs north of the Mississippi River Delta's coastal plains. Because of its prominent location along the river and on the bluffs, which prevents flooding, the French built a fort in the city in 1719.[36] Baton Rouge is the third-southernmost capital city in the continental United States, after Austin, Texas, and Tallahassee, Florida. It is the cultural and economic center of the Greater Baton Rouge metropolitan area.

Climate

Baton Rouge has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), with mild winters, hot and humid summers, moderate to heavy rainfall, and the possibility of damaging winds and tornadoes yearlong. The area's average precipitation is 61.94 inches (141.1 cm) of rain and 0.1 inches (0.25 cm) of snow annually. With ample precipitation, Baton Rouge is fifth on the list of wettest cities in the United States. Snow in the Baton Rouge area is usually rare, although it snowed in three consecutive years recently: December 11, 2008, December 4, 2009, and February 12, 2010. The yearly average temperature for Baton Rouge is 68.4 °F (20.2 °C) while the average temperature for January is 51.7 °F (10.9 °C) and July is 83.0 °F (28.3 °C).[37] The area is usually free from extremes in temperature, with some cold winter fronts, but those are usually brief.[38]

Baton Rouge's proximity to the Gulf of Mexico exposes the metropolitan region to hurricanes. On September 1, 2008, Hurricane Gustav struck the city and became the worst hurricane ever to hit the Baton Rouge area.[39] Winds topped 100 miles per hour (160 km/h), knocking down trees and powerlines and making roads impassable.[40] The roofs of many buildings suffered tree damage, especially in the Highland Road, Garden District, and Goodwood areas. The city was shut down for five days and a curfew was put in effect. Rooftop shingles were ripped off, signs blew down, and minor structural damage occurred.

| Climate data for Baton Rouge, Louisiana (Metropolitan Airport), 1991–2020 normals,[note 2] extremes 1892–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 85 (29) |

88 (31) |

93 (34) |

96 (36) |

101 (38) |

103 (39) |

103 (39) |

110 (43) |

104 (40) |

98 (37) |

89 (32) |

88 (31) |

110 (43) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 77 (25) |

80 (27) |

84 (29) |

88 (31) |

92 (33) |

96 (36) |

97 (36) |

97 (36) |

95 (35) |

91 (33) |

84 (29) |

80 (27) |

98 (37) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 62.3 (16.8) |

66.6 (19.2) |

73.0 (22.8) |

79.1 (26.2) |

85.8 (29.9) |

90.5 (32.5) |

91.9 (33.3) |

92.2 (33.4) |

88.7 (31.5) |

80.9 (27.2) |

71.0 (21.7) |

64.3 (17.9) |

78.9 (26.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 52.0 (11.1) |

55.9 (13.3) |

62.0 (16.7) |

68.0 (20.0) |

75.5 (24.2) |

81.0 (27.2) |

82.9 (28.3) |

82.8 (28.2) |

78.8 (26.0) |

69.5 (20.8) |

59.4 (15.2) |

53.8 (12.1) |

68.5 (20.3) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 41.6 (5.3) |

45.3 (7.4) |

51.0 (10.6) |

56.9 (13.8) |

65.1 (18.4) |

71.5 (21.9) |

73.8 (23.2) |

73.3 (22.9) |

68.9 (20.5) |

58.1 (14.5) |

47.8 (8.8) |

43.3 (6.3) |

58.0 (14.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 24 (−4) |

29 (−2) |

33 (1) |

40 (4) |

51 (11) |

64 (18) |

69 (21) |

67 (19) |

56 (13) |

41 (5) |

31 (−1) |

27 (−3) |

23 (−5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 9 (−13) |

2 (−17) |

20 (−7) |

31 (−1) |

40 (4) |

53 (12) |

58 (14) |

58 (14) |

43 (6) |

30 (−1) |

21 (−6) |

8 (−13) |

2 (−17) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.36 (162) |

4.42 (112) |

4.46 (113) |

5.08 (129) |

5.23 (133) |

6.45 (164) |

5.09 (129) |

6.37 (162) |

4.42 (112) |

4.84 (123) |

3.90 (99) |

5.32 (135) |

61.94 (1,573) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.2 (0.51) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.9 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 8.0 | 8.2 | 11.6 | 13.2 | 11.8 | 8.6 | 7.3 | 8.0 | 9.7 | 114.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74.1 | 70.9 | 70.0 | 70.6 | 72.3 | 74.4 | 77.2 | 77.7 | 76.9 | 72.8 | 74.6 | 74.7 | 73.8 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity 1961–1990)[37][41][42] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1810 | 469 | — | |

| 1840 | 2,269 | — | |

| 1850 | 3,905 | 72.1% | |

| 1860 | 5,428 | 39.0% | |

| 1870 | 6,498 | 19.7% | |

| 1880 | 7,197 | 10.8% | |

| 1890 | 10,478 | 45.6% | |

| 1900 | 11,269 | 7.5% | |

| 1910 | 14,897 | 32.2% | |

| 1920 | 21,782 | 46.2% | |

| 1930 | 30,729 | 41.1% | |

| 1940 | 34,719 | 13.0% | |

| 1950 | 125,629 | 261.8% | |

| 1960 | 152,419 | 21.3% | |

| 1970 | 165,921 | 8.9% | |

| 1980 | 220,394 | 32.8% | |

| 1990 | 219,531 | −0.4% | |

| 2000 | 227,818 | 3.8% | |

| 2010 | 229,493 | 0.7% | |

| 2020 | 227,470 | −0.9% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[43] 2018 Estimate[44] | |||

With a historically high population of 229,493 at the 2010 U.S. census,[45] the city of Baton Rouge's populace have expanded and contracted since the 1980 census; according to the U.S. Census Bureau in 2020,[3] the city had a population of 227,420 while the 2019 American Community Survey estimated 443,763 people lived in the consolidated area of Baton Rouge (East Baton Rouge Parish).[4] The metropolitan population increased to 3.6% as a result of suburbanization in 2019, to an estimated 854,884.[46] In 2020, the metropolitan population increased to 870,569 residents.[5] Per the 2019 American Community Survey, there were 83,733 households with an average of 2.58 people per household. Baton Rouge had a population density of 2,982.5 people per square mile.[45]

According to the 2019 census estimates, 21.6% of households had children under the age of 18 living in them.[45] The owner-occupied housing rate of Baton Rouge was 49.8% and the median value of an owner-occupied housing unit was $174,000. The median monthly owner-costs with a mortgage were $1,330 and the cost without a mortgage was $382. Baton Rouge had a median gross rent of $879, making it one of the Southern U.S.'s most affordable major cities. In the city, the median household income was $44,470 and the per capita income was $28,491 at the 2019 census estimates. Roughly 24.8% of the city lived at or below the poverty line.[45]

Race and ethnicity

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 77,829 | 34.22% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 121,799 | 53.55% |

| Native American | 382 | 0.17% |

| Asian | 7,294 | 3.21% |

| Pacific Islander | 67 | 0.03% |

| Other/Mixed | 6,581 | 2.89% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 13,518 | 5.94% |

.png.webp)

At the 2010 United States census, the racial and ethnic makeup of Baton Rouge proper was 54.54% Black and African American, 39.37% White American, 0.5% American Indian and Alaska Native, 3.5% Asian, and 1.3% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latino Americans of any race were 3.5% of the population. Non-Hispanic whites were 37.8% of the population,[48] down from 70.5% in 1970.[49] The demographic transition into a majority minority city has contributed to this decline; since the 2010 U.S. census, the non-Hispanic white and African American populations have fluctuated, while Black and African American residents remain the largest group in the area, similar to the trends in New Orleans; since the 2020 U.S. census, its Hispanic or Latino American population has also increased reflecting nationwide demographic shifts.[50]

Religion

Christianity is the predominant religion practiced in the Baton Rouge area, accounting for 66.9% of the population in 2019. There is a large Roman Catholic influence in the city and metro area (22.6%), owing in part to French and Spanish settlement, while Baptists are the second largest denomination (20.0%).[51] The Catholic population are primarily served by the Latin Church's Roman Catholic Diocese of Baton Rouge. Prominent Baptist denominations include the National Baptist Convention (USA), National Baptist Convention of America, the Progressive National Baptist Convention, the American Baptist Churches USA,[52] and Southern Baptist Convention.[53]

Other large Christian bodies in the area include Methodists, Anglicans or Episcopalians, Pentecostals, Presbyterians, Latter-Day Saints, and Lutherans.[51] Christians including Jehovah's Witnesses, the Metropolitan Community Church, Christian Unitarians, and the Eastern Orthodox among others collectively make up 14% of the study's other Christian demographic.[51] Notable Methodist and Anglican/Episcopalian jurisdictions operating throughout the Greater Baton Rouge area have included the United Methodist Church,[54] African Methodist Episcopal Church, the Episcopal Diocese of Louisiana,[55] and the Anglican Church in North America.[56] Baton Rouge's Pentecostals mainly affiliate with the Assemblies of God USA and the Church of God in Christ,[57] and Presbyterians are mainly members of the Presbyterian Church (USA).[58]

The second-largest religion in Baton Rouge and its metropolitan area is Islam (0.4%).[51] There are currently over six mosques in the Baton Rouge area, primarily affiliated with Sunni Islam.[59] The Nation of Islam is also another prominent branch of the religion practiced.[60] The Muslim demographic has grown out of Middle Eastern immigration and African American Muslim missionary work.[61] The first Islamic private school in Baton Rouge was established in 2019.[62] As of 2019, Orthodox Jews make up 0.2% of Baton Rouge's religious population, and 0.6% identify with eastern faiths including Buddhism and Hinduism.[51] New religious movements including contemporary paganism have small communities in the area,[63] and a minority affiliate with Haitian Vodou, Louisiana Voodoo, and Hoodoo. A large minority of Baton Rouge's population (31.9%) identifies as either spiritual but not religious, agnostic, or atheist.

Economy

Baton Rouge enjoys a strong economy that has helped the city be ranked as one of the "Top 10 Places for Young Adults" in 2010 by portfolio.com and one of the top 20 cities in North America for economic strength by the Brookings Institution.[64][65] In 2009, the city was ranked by CNN as the 9th-best place in the country to start a new business.[66] Lamar Advertising Company has its headquarters in Baton Rouge.[67] Other notable companies headquartered in the city include BBQGuys, Marucci Sports, Piccadilly Restaurants,[68] and Raising Cane's Chicken Fingers.[69]

Baton Rouge is the farthest inland port on the Mississippi River that can accommodate ocean-going tankers and cargo carriers. The ships transfer their cargo (grain, oil, cars, containers) at Baton Rouge onto rails and pipelines (to travel east–west) or barges (to travel north). Deep-draft vessels cannot pass the Old Huey Long Bridge because the clearance is insufficient. In addition, the river depth decreases significantly just to the north, near Port Hudson.[70]

Baton Rouge's largest industry is petrochemical production and manufacturing. ExxonMobil's Baton Rouge Refinery complex is the fourth-largest oil refinery in the country; it is the world's 10th largest. Baton Rouge also has rail, highway, pipeline, and deep-water access.[71] Dow Chemical Company has a large plant in Iberville Parish near Plaquemine, 17 miles (27 km) south of Baton Rouge.[72] Shaw Construction, Turner, and Harmony all started with performing construction work at these plants.

In addition to being the state capital and parish seat, the city is the home of Louisiana State University, which employs over 5,000 academic staff.[73] One of the largest single employers in Baton Rouge is the state government, which consolidated all branches of state government downtown at the Capitol Park complex.[74]

The city has a substantial medical research and clinical presence. Research hospitals have included Our Lady of the Lake, Our Lady of the Lake Children's Hospital (affiliated with St. Jude Children's Research Hospital), Mary Bird Perkins Cancer Center, and Earl K. Long (closed 2013).[75] Together with an emerging medical corridor at Essen Lane, Summa Avenue and Bluebonnet Boulevard, Baton Rouge is developing a medical district expected to be similar to the Texas Medical Center. LSU and Tulane University have both announced plans to construct satellite medical campuses in Baton Rouge to partner with Our Lady of the Lake Medical Center and Baton Rouge General Medical Center, respectively.[66]

Southeastern Louisiana University and Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady University both have nursing schools in the medical district off Essen Lane. Louisiana State University's Pennington Biomedical Research Center, which conducts clinical and biological research, also contributes to research-related employment in the area around the Baton Rouge medical district.

The film industry in Louisiana has increased dramatically since the beginning of the 21st century, aided by generous tax incentives adopted by the state in 2002. In September 2013, the Baton Rouge Film Commission reported that the industry had brought more than $90 million into the local economy in 2013.[76] Baton Rouge's largest production facility is the Celtic Media Centre, opened in 2006 by a local group in collaboration with Raleigh Studios of Los Angeles. Raleigh dropped its involvement in 2014.[77]

Culture and arts

Baton Rouge is the middle ground of South Louisiana cultures, having a mix of Cajun and Creole Catholics and Baptists of the Florida Parishes and South Mississippi. Baton Rouge is a "college town" with Baton Rouge Community College, Louisiana State University, Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady University, and Southern University, whose students make up 20% of the city population. In a sizable international population of over 11,300, the largest groups were people of Hispanic and Latino or Vietnamese descent. This contributes to Baton Rouge's unique culture and diversity.[78]

Arts and theater

Baton Rouge has an expanding visual arts scene, which is centered downtown. Professional performing arts organizations include Theatre Baton Rouge, the Baton Rouge Symphony Orchestra, Baton Rouge Ballet Theatre, Opera Louisiane and Playmakers, a professional Children's Theatre. This increasing collection of venues includes the Shaw Center for the Arts.[79] Opened in 2005, the facility houses the Brunner Gallery, LSU Museum of Art, the Manship Theatre, a contemporary art gallery, traveling exhibits, and several eateries. Another prominent facility is the Louisiana Art and Science Museum,[80] which contains the Irene W. Pennington Planetarium, traveling art exhibits, space displays, and an ancient Egyptian section. Several smaller art galleries, including the Baton Rouge Gallery, offering a range of local art, are scattered throughout the city.

The city has several designated arts and cultural districts,[81] the most prominent of which are the Mid-City Cultural District and the Perkins Road Arts District. These districts provide tax incentives, mostly in the form of exempting state tax on purchases, to promote cultural activity in these areas.

A performing arts scene is emerging. LSU's Swine Palace is the foremost theatre company in the city, largely made up of students of LSU's MFA acting program, as well as professional actors and stage managers.[82] A group of physical theatre and circus artists from LSU traveled to Edinburgh, Scotland, in summer 2012 to perform Dante in what has become the world's largest Fringe Festival. The show ran in Baton Rouge before going to Fringe, and featured movement, acrobatics, and aerial silk.[83]

Theatre Baton Rouge offers a diverse selection of live theatre performances. Opera Louisiane is Baton Rouge's only professional opera company. The Baton Rouge Ballet Theatre is Baton Rouge's professional ballet company. The Nutcracker– A Tale from the Bayou sets the familiar holiday classic in 19th-century Louisiana and has become a Baton Rouge holiday tradition. A Tale from the Bayou features professional dancers, a live orchestra, and more than 300 area children.

Baton Rouge is also home to Forward Arts, a youth writing organization. Forward Arts won the international youth poetry slam, Brave New Voices in 2017, and was the first team from the Southern United States to ever win the competition. Forward Arts is the only youth spoken-word organization in the state of Louisiana. It was founded by Dr. Anna West in 2005, and first housed in the Big Buddy Program.[84][85]

Baton Rouge is also home to Of Moving Colors Productions, the premier contemporary dance company in the city. For more than 30 years it has brought in internationally established choreographers to create stunning performances. In addition, they conduct extensive community outreach to children and young adults.

Performing venues include the Baton Rouge River Center, Baton Rouge River Center Theatre for the Performing Arts, which seats about 1,900; the Manship Theatre, which is located in the Shaw Center for the Arts and seats 350; and the Reilly Theater, which is home to Swine Palace, a nonprofit professional theater company associated with the Louisiana State University Department of Theatre.

The Baton Rouge Symphony Orchestra has operated since 1947 and currently performs at the River Center Music Hall downtown.[86] Today, it presents more than 60 concerts annually, directed by Timothy Muffitt and David Torns.[86] The BRSO's educational component, the Louisiana Youth Orchestra, made its debut in 1984. It includes almost 180 musicians under the age of 20.

Miss USA pageants

Baton Rouge was chosen to host the Miss USA 2014 Pageant. It took over downtown Baton Rouge as Nia Sanchez, Miss Nevada USA, took home the crown, with Miss Louisiana USA Brittany Guidry coming in fourth. Veteran pageant host Giuliana Rancic and MSNBC news anchor Thomas Roberts introduced the 51 contestants; there were 20 semifinalists. Cosmo weighed in on the contest, complimenting Guidry.[87] Celebrity judges included actress Rumer Willis, NBA star Karl Malone, singer Lance Bass, and actor Ian Ziering.[88] In the contest's 62-year history, this was the first year that viewers got to vote to keep one of their favorite contestants in the top six by tweeting the hashtag #SaveTheQueen. Baton Rouge hosted Miss USA 2015 again on July 12, 2015, which was won by actress and Miss Oklahoma USA Olivia Jordan. Baton Rouge was also the site of the 2005 Miss Teen USA Pageant.[89]

Tourism and recreation

%252C_January_2013.jpg.webp)

Baton Rouge's many architectural points of interest range from antebellum to modern. The neo-gothic Old Louisiana State Capitol was built in the 1850s as the first statehouse in Baton Rouge. It was later replaced by the 450-ft-tall, art deco New Louisiana State Capitol, the tallest building in the South when it was completed. Several plantation homes in the area, such as Magnolia Mound Plantation House, Myrtles Plantation, and Nottoway Plantation, showcase antebellum-era architecture.

LSU has more than 250 buildings in Italian Renaissance style, one of the nation's largest college stadiums, and many live oaks. The downtown has several examples of modern and contemporary buildings, including the Capitol Park Museum.[90]

A number of structures, including the Baton Rouge River Center, Louisiana State Library, LSU Student Union, Louisiana Naval Museum, Bluebonnet Swamp Interpretive Center, Louisiana Arts and Sciences Center, Louisiana State Archive and Research Library, and the Pennington Biomedical Research Center, were designed by local architect John Desmond.[91] The Pentagon Barracks Museum and Visitors Center is within the barracks complex and the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Railroad Company Depot houses the Louisiana Art and Science Museum.[92]

Museums around town offer a variety of genres. The Capitol Park Museum and the Old Louisiana State Capitol Museum display information on state history and have many interactive exhibits. The Shaw Center for the Arts and the Louisiana Art and Science Museum showcase varied arts. LASM also includes science exhibits and a planetarium. Other museums include the LSU Museum of Natural Science and the USS Kidd. The Odell S. Williams Now And Then African-American Museum chronicles the progression and growth of African-Americans.

Other attractions include the Mall of Louisiana and Perkins Rowe, amusement parks of Dixie Landin'/Blue Bayou, and dining at the Louisiana-cuisine restaurants.

The 2nd Annual Slam'd & Cam'd Car Show, slated for July 10, 2021, was scheduled to begin after the cancellation of the 2020 show due to the pandemic. The 2021 show planned to present than 300 muscle cars and include TV personality Courtney Hansen and MotorTrend Group's, Iron Resurrection stars, Joe and Amanda Martin.[93]

Sports

College sports play a major role in the culture of Baton Rouge. The LSU Tigers and the Southern University Jaguars are NCAA Division I athletic programs with the LSU Tigers football and Southern Jaguars football teams being the local college American football teams. College baseball, basketball, and gymnastics are also popular.[94][95]

Much of the city's sport's attention is focused on the professional teams in Greater New Orleans. Baton Rouge has had multiple minor-league baseball teams (the Baton Rouge Red Sticks), soccer teams (Baton Rouge Bombers), indoor football teams, a basketball team, and a hockey team (Baton Rouge Kingfish). The Baton Rouge Rugby Football Club or Baton Rouge Redfish 7, which began playing in 1977, has won numerous conference championships. Currently, the team competes in the Deep South Rugby Football Union.[96] It also has an Australian rules football team, the Baton Rouge Tigers, which began playing in 2004 and competes in the USAFL. In addition, Baton Rouge is home to Red Stick Roller Derby, a WFTDA Division 3 roller derby league. Baton Rouge is also home to the Baton Rouge Soccer Club in the Gulf Coast Premier League and the Baton Rouge Rougarou, a college summer league baseball team and member of the Texas Collegiate League; in 2022, it was announced USL League Two would establish a team in Baton Rouge named LA Parish AC,[97] following the establishment of other teams in Lafayette and Shreveport.[98][99]

Parks and recreation

Baton Rouge has an extensive park collection run through the Recreation & Park Commission for the Parish of East Baton Rouge (BREC). The largest park is City Park near the Louisiana State University flagship campus. The Baton Rouge Zoo is also run through BREC and includes over 1,800 species.[100]

National protected areas

- Atchafalaya National Heritage Area

- Baton Rouge National Cemetery

- Independence Park Botanic Gardens

- Laurens Henry Cohn, Sr. Memorial Plant Arboretum

- LSU Hilltop Arboretum

- Magnolia Cemetery

- Port Hudson National Cemetery

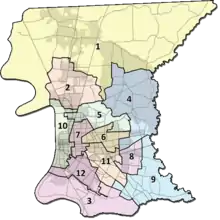

Government

The city of Baton Rouge and the Parish of East Baton Rouge have been run by a consolidated government since 1947. It combined the City of Baton Rouge government with the rural areas of the parish, allowing people outside the limits of the City of Baton Rouge to use city services. Though the city and parish have a consolidated government, this differs slightly from a traditional consolidated city-county[note 3] government. The cities of Zachary, Baker, and Central operate their own city governments within East Baton Rouge Parish. Under this system, Baton Rouge has the uncommon office of "mayor-president", which consolidates the executive offices of "mayor of Baton Rouge" and "president of East Baton Rouge Parish". Though Zachary, Baker, and Central each have their own mayors, citizens living in these municipalities are still a part of the constituency who can vote and run in elections for mayor-president and metro council.[101]

The mayor-president's duties include setting the agenda for the government and managing the government's day-to-day functions. They are also responsible for supervising departments, as well as appointing the department heads. The mayor does not set the city's public policy because that is the Metropolitan Council's role, but the mayor-president does have some influence on the policy through appointments and relationships with Council members.

The current mayor-president of Baton Rouge is Sharon Weston Broome, a former Louisiana State Legislator. A Democrat, Broome succeeded Kip Holden, also a Democrat, on January 2, 2017, after defeating Bodi White in a close runoff on December 10, 2016.[102] She served in the Louisiana House of Representatives from 1992 to 2004, and in the Louisiana State Senate from 2004 to 2016. She was elected by the senate to serve as the Senate President Pro Tempore from 2008 to 2016.[1][101][103]

Metropolitan council

When the city and parish combined government, the city and parish councils consolidated to form the East Baton Rouge Parish Metropolitan Council. The Metro Council is the legislative branch of the Baton Rouge government. Its 12 district council members are elected from single-member districts. They elect from among themselves the mayor-president pro tempore. The Mayor-President Pro Tempore presides over the council's meetings and assumes the role of the Mayor-President if the Mayor-President is unable to serve. The council members serve four-year terms and can hold office for three terms.

In the late 1960s, Joe Delpit, a local African-American businessman who owns the successful and still operating Chicken Shack, was elected as the first black council member in Baton Rouge. As in other cities of Louisiana and the South, African Americans had been largely disenfranchised for decades into the 20th century.[104] The Chicken Shack, with multiple locations, in 2015 was reported as the oldest continually operating business in Baton Rouge.[105]

The Metro Council's main responsibilities are setting the policy for the government, voting on legislation, and approving the city's budget. The Council makes policies for the following: the City and Parish General Funds, all districts created by the council, the Greater Baton Rouge Airport District, the Public Transportation Commission, the East Baton Rouge Parish Sewerage Control Commission and the Greater Baton Rouge Parking Authority.[101]

Education

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Baton Rouge is stimulated by many universities. Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, generally known as Louisiana State University or LSU, is a public, coeducational university that is the flagship campus of the Louisiana State University System. LSU is Louisiana's largest university, with over 30,000 students and 1,300 full-time faculty members. Southern University and A&M College, generally known as Southern University or SU, is the flagship institution of the Southern University System, the nation's only historically black land-grant university system. SU is the largest HBCU and second-oldest public university in Louisiana.

Virginia College opened in October 2010 and offers students training in areas such as cosmetology, business, health, and medical billing. Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady University is an independent Catholic institution also in the Baton Rouge medical district that has programs in nursing, health sciences, humanities, behavioral sciences, and arts and sciences. It has an associated hospital, Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center.[106] Tulane University is also opening a satellite medical school at Baton Rouge General's Mid City Campus in 2011.[107]

Southeastern Louisiana University School of Nursing is located in the medical district on Essen Lane in Baton Rouge. Southeastern offers traditional baccalaureate and master's degree programs, as well as LPN and RN to BSN articulation. Baton Rouge Community College is an open-admission, two-year post-secondary public community college, established on June 28, 1995. The college settled into a permanent location in 1998. The college's enrollment is more than 8,000 students.[108] The Pennington Biomedical Research Center houses 48 laboratories and 19 core research facilities.[109]

Primary and secondary schools

East Baton Rouge Parish Public Schools operates primary and secondary schools serving the city. The city of Baton Rouge is also home to 27 charter schools with a total enrollment of an estimated 11,000 students as of 2020.[110] One of the latest includes the Mentorship Academy in downtown Baton Rouge, which leverages its location downtown to establish internship opportunities with local businesses as well as provide a high-tech classroom environment to focus on a digital animation curriculum.[111]

The East Baton Rouge Parish School System is the second-largest public school system in the state and contains nine U.S. Blue Ribbon schools and a nationally renowned Magnet program. The school system serves more than 42,850 students and with the help of 6,250 teachers and faculty, the district has shown growth and increase in its District Performance Score. The East Baton Rouge Parish Public Schools serve East Baton Rouge Parish and has 90 schools with 56 elementary schools, 16 middle schools, and 18 high schools.[112]

Libraries

.jpg.webp)

The State Library of Louisiana is in Baton Rouge. The Louisiana Legislature created the Louisiana Library Commission in 1920. This later became the State Library of Louisiana. The State Library provides Louisiana residents with millions of items with its collections, electronic resources, and the statewide network for lending.[113]

The East Baton Rouge Parish Library System has 14 local libraries with one main library and 13 community libraries. The main library at Goodwood houses genealogy and local history archives. The library system is an entity of the city-parish government. The system has been in operation since 1939. It is governed by the EBR Parish government and directed by the Library Board of Control. The Baton Rouge Metropolitan Council appoints the seven-member board and then the board appoints a director. According to its website, all branches are open seven days a week to assist the public with reference and information and computer access.[114]

The Louisiana State Archives' Main Research Library is located in Baton Rouge, as well. It houses general history books, census indices, immigration schedules, church records, and family histories. The library also has a computerized database of more than two million names that has various information about these people including census, marriage, and social security filing information.[115]

Louisiana State University and the Louisiana State University Law Center have libraries on their respective Baton Rouge campuses.[116] Southern University and A&M College and the Southern University Law Center also have libraries on their respective Baton Rouge campuses.[117]

Media

The major daily newspaper for the Greater Baton Rouge metropolitan area is The Advocate, publishing since 1925. Until 1991, Baton Rouge also had an evening newspaper, The State-Times—at that time, the morning paper was known as The Morning Advocate. Other publications include: Baton Rouge Parents Magazine, Pink & Blue Magazine, The Daily Reveille, The Southern Review, 225 magazine, DIG, Greater Baton Rouge Business Report, inRegister magazine, 10/12 magazine, Country Roads magazine, 225Alive, Healthcare Journal of Baton Rouge, Southern University Digest, and The South Baton Rouge Journal.

Other newspapers in East Baton Rouge Parish include the Central City News and The Zachary Post. The Greater Baton Rouge area is well served by television and radio. The market is the 95th-largest designated market area in the U.S. Major television network affiliates serving the area include:

Baton Rouge also offer local government-access television-only channels on Cox Cable channel 21.

Infrastructure

Health and medicine

Baton Rouge is served by several hospitals and clinics:

- Baton Rouge General Medical Center – Mid-City Campus, 3600 Florida Boulevard

- Baton Rouge General Medical Center – Bluebonnet Campus, 8585 Picardy Avenue

- HealthSouth Rehabilitation Hospital, 8595 United Plaza Boulevard

- Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center, 5000 Hennessy Boulevard

- Ochsner Medical Center, 1700 Medical Center Drive

- Our Lady of the Lake Children's Hospital, 5000 Hennessy Boulevard

- Ochsner Medical Complex – The Grove, 10310 The Grove Boulevard

Communication

Most of the Baton Rouge area's high-speed internet, broadband, and fiber optic communications are provided by Eatel, AT&T Inc., Charter Communications, or Cox Communications.[118] In 2006, Cox Communications linked its Lafayette, Baton Rouge, and New Orleans markets with fiber-optic infrastructure. Other providers soon followed suit, and fiber optics have thus far proven reliable in all hurricanes since they were installed, even when mobile and broadband services are disrupted during storms. In 2001, the Supermike computer at Louisiana State University was ranked as the number-one computer cluster in the world,[119] and remains one of the top 500 computing sites in the world.[120]

Military installations

Baton Rouge is home station to the Louisiana Army National Guard 769th Engineer Battalion,[121] which recently had units deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. The armory near LSU has three company-sized units: 769th HSC (headquarters support company); 769th FSC (forward support company); and the 927th Sapper Company. Other units of the battalion are located at Napoleonville (928th Sapper Company); Baker, Louisiana (926th MAC mobility augmentation company); and Gonzales, Louisiana (922nd Horizontal Construction Company).

The 769th Engineer Battalion is part of the 225th Engineer Brigade, headquartered in Pineville, Louisiana, at Camp Beauregard. Four engineer battalions and an independent bridging company are in the 225th Engineer Brigade, making it the largest engineer group in the US Army Corps of Engineers.

Baton Rouge is also home to 3rd Battalion, 23rd Marine Regiment (3/23),[122] a reserve infantry battalion in the United States Marine Corps located throughout the Midwestern United States consisting of about 800 marines and sailors. The battalion was first formed in 1943 for service in the Pacific Theater of Operations during World War II, taking part in a number of significant battles including those at Saipan and Iwo Jima before being deactivated at the end of the war. In the early 1960s, the unit was reactivated as a reserve battalion. The battalion is headquartered in Saint Louis, Missouri, with outlying units throughout the Midwestern United States. 3/23 falls under the command of the 23rd Marine Regiment and the 4th Marine Division. Recent operations have included tours in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Transportation

Shipping

The Port of Baton Rouge is the 9th-largest in the United States by tonnage shipped, and is the farthest upstream Mississippi River port capable of handling Panamax ships.[11][12]

Highways and roads

.jpg.webp)

Interstates

Baton Rouge has three interstate highways: I-10, I-12 (Republic of West Florida Parkway), and I-110 (Martin Luther King Jr. Expressway).

Interstate 10 enters the city from the Horace Wilkinson Bridge over the Mississippi River, curving at an interchange with Interstate 110 southeast, crossing the LSU lakes and Garden District before reaching an interchange with I-12 (referred to as the 10/12 split). It curves further southeast toward New Orleans as it crosses Essen Lane near the Medical District. It passes Bluebonnet Blvd and the Mall of Louisiana at exit 162, and leaves Baton Rouge after interchanges with Siegen Lane and Highland Road.

Interstate 12 (The Republic of West Florida Parkway) begins in the city at the I-10/I-12 split east of College Drive, and proceeds eastward, crossing Essen Lane, Airline Hwy, Sherwood Forest Blvd, Millerville Road, and O'neal Lane before leaving the city when crossing the Amite River.

Interstate 110 (The Martin Luther King Jr. Expressway) stretches 8 miles in a north–south direction from the east end of the Horace Wilkinson Bridge to Scenic Highway in Scotlandville, Louisiana. It passes through downtown, North Baton Rouge, and Baton Rouge Metro Airport before ending at Scenic Highway.

US highways and major roads

Baton Rouge has two US highways, along with their business counterparts: Airline Highway (US 61) and Florida Boulevard.

US 190 enters the city from the Huey P. Long Bridge, beginning a concurrency with US 61 after an interchange with Scenic Highway, near Scotlandville. Its name is Airline Highway from this interchange to the interchange with Florida Blvd. At this interchange, US 190 turns east to follow Florida Blvd through Northeast Baton Rouge, exiting the city at the Amite River.

US 61 enters Baton Rouge as Scenic Highway until it reaches Airline Highway (US 190). It becomes concurrent with US 190 until Florida Blvd, where it continues south, still called Airline Highway. It passes through Goodwood and Broadmoor before an interchange with I-12. It continues southeast past Bluebonnet Blvd/Coursey Blvd, Jefferson Hwy, and Sherwood Forest Blvd/Siegen Lane before exiting the city at Bayou Manchac.

US 61/190 Business runs west along Florida Boulevard (known as Florida Street from Downtown east to Mid City) from Airline Highway to River Road in downtown. The cosigned routes run from Florida St. north along River Road, passing the Louisiana State Capitol and Capitol Park Complex before intersecting with Choctaw Drive. North of this intersection River Road becomes Chippewa Street and curves to the East. US 61/190 Business leaves Chippewa Street at its intersection with Scenic Highway. The route follows Scenic Highway to Airline Highway, where it ends. North of Airline on Scenic and East of Scenic Highway on Airline is US 61. US 190 is East and West of Scenic on Airline Highway.

These are important surface streets with designated state highway numbers: Greenwell Springs Road (LA 37), Plank Road/22nd Street (LA 67), Burbank Drive/Highland Road (LA 42), Nicholson Drive (LA 30), Jefferson Highway/Government Street (LA 73), Scotlandville/Baker/Zachary Highway (LA 19), Essen Lane (LA 3064), Bluebonnet Blvd/Coursey Blvd (LA 1248), Siegen Lane/Sherwood Forest Blvd (LA 3246), and Perkins Road/Acadian Thruway (LA 427).

Traffic issues and highway upgrades

According to the 2008 INRIX National Traffic Scorecard, which ranks the top 100 congested metropolitan areas in the U.S., Baton Rouge is the 33rd-most congested metro area in the country. At a population rank of 67 out of 100, it has the second-highest ratio of population rank to congestion rank, higher than even the Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana metropolitan area, indicating a remarkably high level of congestion for the comparatively low population. According to the Scorecard, Baton Rouge was the only area out of all 100 to show an increase in congestion from 2007 to 2008 (+ 6%). The city also tied for the highest jump in congestion rank over the same period (14 places).[123]

Interstate 12 used to have a major bottleneck at O'Neal Lane. The interstate was three lanes wide in each direction to the O'Neal Lane exit, where the interstate abruptly became two lanes in each direction and crossed the narrow Amite River Bridge. This stretch of road, called "a deathtrap"[124] by one lawmaker, had become notorious for traffic accidents, many with fatalities. In 2007, ten people died in traffic accidents within a three-month period on this section of road.[125] In 2009, Governor Bobby Jindal and the Baton Rouge legislative delegation allocated state and federal funding to widen I-12 from O'Neal Lane to Range Avenue (Exit 10) in Denham Springs. The construction was completed in 2012 and has significantly improved the flow of traffic.[126] In 2010, The American Reinvestment and Recovery Act provided committed federal funds to widen I-12 from the Range Avenue Exit to Walker, Louisiana. Noticing the significant improvement in commute times, Jindal further funded widening to Satsuma, Louisiana.

Interstate 10 West at Bluebonnet Road also ranked within the top 1000 bottlenecks for 2008, and I-10 East at Essen Lane and Nicholson Drive ranked not far out of the top 1000. A new exit to the Mall of Louisiana was created in 2006, and the interstate was widened between Bluebonnet Blvd and Siegen Lane. But the stretch of I-10 from the I-10/I-12 split to Bluebonnet Blvd was not part of these improvements and remained heavily congested during peak hours. In response, a widening project totaling at least $87 million began in late 2008. Interstate 10 was widened to three lanes over a five-year period between the I-10/I-12 split and Highland Road.[127] In 2010, the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act provided supplemental funding for this project to extend to the Highland Road exit in East Baton Rouge Parish.[128] Commute times have since plummeted for this section of interstate.

Surface streets in Baton Rouge are prone to severe congestion. But roads are beginning to handle the number of vehicles using them after years of stagnation in road upgrades. Baton Rouge Mayor Kip Holden has instituted an extensive upgrade of East Baton Rouge Parish roads known as the Green Light Plan, geared toward improving areas of congestion on the city's surface streets. With its first project completed in 2008, it has seen numerous others reach completion as of 2015, with several more under construction and still others yet to break ground.[129]

A circumferential loop freeway was proposed for the greater Baton Rouge metro area to help alleviate congestion on the existing through-town routes. The proposed loop would pass through the outlying parishes of Livingston (running alongside property owned and marketed as an industrial development by Al Coburn, a member of President Mike Grimmer's staff), Ascension, West Baton Rouge, and Iberville, as well as northern East Baton Rouge Parish. This proposal has been subject to much contention, particularly by residents living in the outer parishes through which the loop would pass.[130] Other suggestions considered by the community are upgrading Airline Highway (US 61) to freeway standards in the region as well as establishing more links between East Baton Rouge Parish and its neighboring communities.

Commuting

The average one-way commute time in Baton Rouge is 26.5 minutes,[131] slightly less than the US average of 27.1 minutes.[132] Interstates 10, 110 and 12, which feed into the city, are highly traveled and connected by highways and four-lane roads that connect the downtown business area to surrounding parishes.[133]

According to the 2016 American Community Survey, 81.9% of working Baton Rouge residents commuted by driving alone, 8.5% carpooled, 3% used public transportation, and 2.4% walked. About 1.2% used all other forms of transportation, including taxi, bicycle, and motorcycle. About 3.1% worked at home.[134] The city of Baton Rouge has a higher than average percentage of households without a car. In 2015, 10.4 percent of Baton Rouge households lacked a car, and increased slightly to 11.4 percent in 2016. The national average is 8.7 percent in 2016. Baton Rouge averaged 1.55 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8.[135]

Airport

Located 10 minutes north of downtown near Baker, the Baton Rouge Metropolitan Airport connects the area with the four major airline hubs serving the southern United States. Commercial carriers include American Eagle, United Airlines, and Delta Air Lines. Nonstop service is available to Atlanta, Dallas-Ft. Worth, Houston, and Charlotte.

Rail

Three major rail lines, Kansas City Southern, Union Pacific, and Canadian National provide railroad freight service to Baton Rouge.[136]

The Yazoo and Mississippi Valley station had passenger service until the mid-1960s. The Kansas City Southern depot hosted the Southern Belle, the final train to serve the city, until 1969.[137][138] Since 2006, Baton Rouge and New Orleans leaders as well as the state government have been pushing to secure funding for a new high-speed rail passenger line between downtown Baton Rouge and downtown New Orleans, with several stops in between.[139]

Buses and other mass transit

Capital Area Transit System (CATS) provides urban transportation throughout Baton Rouge, including service to Southern University, Baton Rouge Community College, and Louisiana State University. Many CATS buses are equipped with bike racks for commuters to easily combine biking with bus transit.

Greyhound Bus Lines, offering passenger and cargo service throughout the United States, has a downtown terminal on Florida Boulevard.

Sister cities

- Cairo, Cairo Governorate, Egypt (since 1951)[140]

- Rouen, Seine-Maritime, France (since 1963)[141]

- Taichung, Taiwan (since 1976)[142]

- Ciudad Obregón, Sonora, Mexico (since 1977)[143]

- Port-au-Prince, Ouest, Haiti (since 1978)[144]

- Liège, Liège Province, Belgium (since 1985)[145]

- Aix-en-Provence, Bouches-du-Rhône, France (since 1987)[146]

- Córdoba, Veracruz, Mexico (since 2002)[147]

- Heze, Shandong, People's Republic of China (since 2008)[148]

- Malatya, Malatya Province, Turkey (since 2009)[149]

- Guiyang, Guizhou, People's Republic of China (since 2010)[150]

See also

- Baton Rouge Police Department

- Cancer Alley

- East Baton Rouge Parish Sheriff's Office

- Louisiana Technology Park

- List of people from Baton Rouge, Louisiana

- List of U.S. cities with large Black populations

- List of U.S. communities with African-American majority populations

Explanatory notes

- Total area for the City of Baton Rouge, not all of East Baton Rouge Parish

- Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- Because the Louisiana uses parishes, the equivalent of a county in other states, in the state this form of government is called a "consolidated city-parish".

References

Citations

- "Office of Mayor President". Baton Rouge Government Website. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- "QuickFacts: Baton Rouge, Louisiana". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "2019 Demographic and Housing Census for East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana". census.gov.

- "2020 Population and Housing State Data". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - U.S. Census Bureau. "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- "LSU Libraries - Special Collections - Andrew David Lytle, photographic artist - Baton Rouge: Levee Construction, Mississippi River". Louisiana State University. Archived from the original on August 29, 2008. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- "Growing Louisiana-Based Businesses Sustains Hollywood South" Archived February 27, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Forbes, June 9, 2014

- "IBM selects BR" Archived May 26, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Advocate – Baton Rouge, LA

- (LSU), Louisiana State University. "About Us". lsu.edu. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- "Top 25 Water Ports by Weight: 2004 (Million short tons)". Freight Facts and Figures 2006. Federal Highway Administration. November 2006. Archived from the original on November 21, 2007. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- "About the Port". portgbr.com. Archived from the original on February 6, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- Comite River Basin, Amite River and Tributaries Flood Protection, Baton Rouge/Livingston Parishes: Environmental Impact Statement, Volume 2. Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development. 1991. pp. B–7–5.

- "Baton Rouge Historical Marker". Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism. Archived from the original on August 2, 2009. Retrieved August 1, 2009.

- Saunders, Rebecca (Winter 1994). "The Case for Archaic Period Mounds in Southeastern Louisiana". Southeastern Archaeology. 13 (2): 118–134. JSTOR 40656501.

- Hopkins, Nicholas A. (2007). "The Native Languages of the Southeastern United States" (PDF). FAMSI. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- About North Georgia (1994–2006). "Moundbuilders, North Georgia's early inhabitants". Golden Ink. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- Rose Meyers, A History of Baton Rouge 1699–1812 (1976), 4 ff.

- Di Maio, Irene Stocksieker, ed. (2006). Gerstäcker's Louisiana: Fiction and Travel Sketches from Antebellum Times Through Reconstruction. Louisiana State University Press. p. 307. ISBN 9780807131466.

- Albrecht, Andrew C. (1945). "The Origin and Early Settlement of Baton Rouge, Louisiana". Louisiana Historical Quarterly. 28 (1): 5–68.

- "Pentagon Barracks". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 15, 2008. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- "Pentagon Barracks". Louisiana Capitol History and Tour. Archived from the original on April 19, 2009. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- "Old Louisiana State Capitol" Archived January 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, National Park Service

- Baedeker, Karl, ed. The United States with an Excursion into Mexico: A Handbook for Travelers, 1893: p. 321 (Reprint by Da Capo Press, New York, 1971)

- "As companies along Airline migrate south, what does it mean for those left behind?". Baton Rouge Business Report. February 10, 2015. Archived from the original on October 2, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- Metropolitan Areas Ranked by Population 1990–2000 United States Census Bureau, Population Division

- "Groups plan to make push for Google Fiber experiment" Archived July 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, WAFB, April 5, 2010.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "Distance between Baton Rouge, LA and New Orleans, LA". www.distance-cities.com. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "Distance between Baton Rouge, LA and Alexandria, LA". www.distance-cities.com. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "Distance between Baton Rouge, LA and Shreveport, LA". www.distance-cities.com. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "Distance between Baton Rouge, LA and Jackson, MS". www.distance-cities.com. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "Distance between Baton Rouge, LA and Houston, TX". www.distance-cities.com. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "Climate Baton Rouge – Louisiana and Weather averages Baton Rouge". usclimatedata.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Baton Rouge city, Louisiana". www.census.gov. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- "Geography of Baton Rouge". How Stuff Works. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- "Baton Rouge: Geography and Climate". Answers. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- Deaton, Diane. "The Fifth Season: Ten year anniversary of Hurricane Gustav". WAFB. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Department of Homeland Security. Federal Emergency Management Agency. Public Affairs Division. 3/1/2003- (September 1, 2008). [Hurricane Gustav] Baton Rouge, LA, September 1, 2008 -- Hurricane Gustav hit the city of Baton Rouge with 100 mph plus winds and took the roof off of the Alpha Kappa Alpha alumni-house in the downtown area. Barry Bahler/FEMA. Series: Photographs Relating to Disasters and Emergency Management Programs, Activities, and Officials, 1956 - 2008.

- "Station: Baton Rouge Ryan AP, LA". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- "WMO Climate Normals for Baton Rouge/WSO AP, LA 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Baton Rouge city, Louisiana 2019 Estimates". www.census.gov. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Baton Rouge population declines since 2010, though metro area up 3.6%". Baton Rouge Business Report. May 23, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- "Baton Rouge (city), Louisiana". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 13, 2005. Retrieved April 21, 2012.

- "Louisiana—Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2012.

- Passel, Jeffrey S.; Lopez, Mark Hugo; Cohn, D'Vera. "U.S. Hispanic population continued its geographic spread in the 2010s". Pew Research Center. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- "Baton Rouge, Louisiana Religion". bestplaces.net. Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- "Find A Church". ABCUSA. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "Southern Baptist Convention > ChurchSearch". www.sbc.net. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "Baton Rouge". www.la-umc.org. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "Church Directory (By City) | The Episcopal Diocese of Louisiana". Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "Find a Congregation". The Anglican Church in North America. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "Find a Church". ag.org. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- Church (U.S.A.), Presbyterian (July 31, 2020). "Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) – Resources". www.pcusa.org. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "mosques in baton rouge – Google Search". google.com. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- Phelps, Earl. "Nation of Islam calls for new boycotts in Baton Rouge". WBRZ. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "INCREASING ISLAM: A Glimpse At Muslim Immigration And Its Massive Expansion Into Louisiana". The Hayride. June 13, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "Crews break ground on new building for Islamic school in Baton Rouge". www.wafb.com. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Parker, Trent. "Local pagans seek religious rights". The Reveille. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "Austin Washington Raleigh And Boston Top 2010 Rank Of Best Cities For Young Americans". Portfolio.com. September 11, 2008. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- "MetroMonitor: Tracking Economic Recession and Recovery in America's 100 Largest Metropolitan Areas" (PDF). June 7, 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 7, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- "Learn". CNN. Archived from the original on March 5, 2010. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- "contact us Archived May 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine." Lamar Advertising Company. Retrieved on February 25, 2011. "5321 Corporate Boulevard Baton Rouge, LA 70808."

- "RAISING CANE'S CHICKEN FINGERS – CORPORATE OFFICE". investors.brac.org.

- "Raising Cane's Chicken Fingers – Corporate Office". investors.brac.org. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "Port of Greater Baton Rouge". Archived from the original on June 14, 2006. Retrieved April 26, 2008.

- "Exxon Mobil Refinery". Archived from the original on December 22, 2007. Retrieved April 26, 2008.

- "DowChemicals". Archived from the original on May 7, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2008.

- "About Us". lsu.edu. Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- "Capitol Park". Archived from the original on May 8, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2008.

- bureau, marsha shuler Capitol news. "Earl K Long Hospital to close in April". The Advocate. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- "Movie makers put Baton Rouge in spotlight" Archived September 4, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press at WBRZ-TV, September 15, 2013.

- Bill Lodge, "Celtic Group becomes sole operator of BR movie studio" Archived September 4, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, The Advocate, February 20, 2014.

- "Races in Baton Rouge on City-Data.com". Archived from the original on April 18, 2008. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- "Shaw Center for the Arts". Archived from the original on April 5, 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- "Louisiana Arts and Science Museum". Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- "Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism". Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved May 4, 2012.

- "The Premier Professional Theatre of Louisiana". Swine Palace. July 18, 2012. Archived from the original on October 29, 2012. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- "LSU Department of Theatre to Present "Dante" March 27 – April 6 in Movement Studio". Lsu.edu. March 9, 2012. Archived from the original on June 4, 2012. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- "Baton Rouge River Center". Archived from the original on April 16, 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- "Baton Rouge Little Theater". Archived from the original on April 9, 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- "Baton Rouge Symphony Orchestra". Brso.org. Archived from the original on May 5, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- Lefferts, Brooke. "Miss Nevada wins Miss USA crown in Baton Rouge". Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- "Miss USA : News". Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- "Miss USA : News". Archived from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- "Louisiana State Museum". Archived from the original on April 13, 2008. Retrieved April 14, 2008.

- "News | Architect Desmond dies—Baton Rouge, LA". 2theadvocate.com. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- "LOUISIANA ART AND SCIENCE MUSEUM". www.lasm.org. Archived from the original on June 5, 2008. Retrieved May 29, 2008.

- Gerron, Jordan (July 9, 2021). "2nd Annual Slam'd & Cam'd Car Show rolls through the Baton Rouge this weekend". brproud.com. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Louisiana State University Sports". Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- "Southern Jaguars". Archived from the original on April 15, 2008. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- "Baton Rouge Rugby.net". Baton Rouge Rugby.net. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- Staff, USLLeagueTwo com (February 20, 2022). "Baton Rouge Club Participating in USL League Two Unveils Name and Crest". USL League Two. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- Staff, USLLeagueTwo com (October 27, 2021). "Louisiana Krewe FC Set to Join USL League Two for the 2022 Season". USL League Two. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- Staff, USLLeagueTwo com (January 13, 2022). "United Soccer League Welcomes Blue Goose Soccer Club to League Two for the 2022 Season". USL League Two. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- "The Recreation and Park Commission for the Parish of East Baton Rouge". Archived from the original on April 9, 2008. Retrieved April 14, 2008.

- "Baton Rouge Government". City of Baton Rouge. Archived from the original on July 28, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- GALLO, ANDREA. "Sharon Weston Broome sworn in as Baton Rouge's mayor-president". The Advocate. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "Metropolitan Council". City of Baton Rouge. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- Thomas A. Johnson, "Louisiana Negroes Seek Power", New York Times, 29 September 1971; accessed 20 March 2019

- Annie Ourso Landry, "The Delpit family's Chicken Shack is still going strong after eight decades" Archived June 22, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Business Report, 22 July 2015

- "LSU reaches agreement with Baton Rouge hospital; will close Earl K. Long". NOLA.com. The Associated Press. January 25, 2010. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- Strecker, Mike (March 3, 2010). "Tulane University, Baton Rouge General Affiliate for Medical School Training Campus". Tulane.edu. Archived from the original on October 8, 2011.

- "Baton Rouge Area Education". Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- Pennington Biomedical Research Center Archived July 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Pbrc.edu. Retrieved on July 29, 2013.

- Lussier, Charles. "Five of six new Baton Rouge charter schools set to open in August delay a year, four more apply". The Advocate. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Old bank to come back as charter school site". July 5, 2010. Archived from the original on July 18, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

- East Baton Rouge Parish School Board Archived June 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Ebrschools.org (July 23, 2012). Retrieved on July 29, 2013.

- "Hours and Location Archived April 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine." State Library of Louisiana. Retrieved on August 20, 2010.

- About the Library Archived June 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. EBRPL.com. Retrieved on July 29, 2013.

- Louisiana State Archives and Libraries Archived December 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Statearchives.us. Retrieved on July 29, 2013.

- "LSU Libraries". www.lib.lsu.edu. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "WELCOME TO JOHN B. CADE LIBRARY | Southern University and A&M College". www.subr.edu. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ":: Baton Rouge Business Report :: Dueling strands of fiber optics". Businessreport.com. Archived from the original on November 20, 2010. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- "LSU CAPITAL's Supercomputer". Phys.lsu.edu. Archived from the original on May 9, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- Seymour Cray. "SuperMike | TOP500 Supercomputing Sites". Top500.org. Archived from the original on September 4, 2008. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- "769th ENGINEER BATTALION – Lineage and Honors Information – U.S. Army Center of Military History". history.army.mil. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- Inc, MarineParents com. "3rd Battalion, 23rd Marines (3/23) on MarineParents.com". MarineParents.com. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "INRIX National Traffic Scorecard". Scorecard.inrix.com. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- "I-12 accidents piling up". 2theadvocate.com. Archived from the original on July 3, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- "More funds sought for I-12 widening project". 2theadvocate.com. Archived from the original on June 8, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- "I-12 work to begin". 2theadvocate.com. Archived from the original on May 4, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- "Project on I-10 to begin". 2theadvocate.com. Archived from the original on July 3, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- "Geaux Wider". Geaux Wider. Archived from the original on March 15, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- "The Green Light Plan". Greenlight.csrsonline.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- "Poll shows public support for loop". 2theadvocate.com. May 12, 2009. Archived from the original on July 3, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- "Average Commute Times for Metro Areas". www.governing.com. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- Ingraham, Christopher (October 7, 2019). "Analysis | Nine days on the road. Average commute time reached a new record last year". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- Alex. "Baton Rouge". AARoads. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- "Means of Transportation to Work by Age". Census Reporter. Archived from the original on May 18, 2018. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- "Car Ownership in U.S. Cities Data and Map". Governing. Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- "BNSF Railway System Map" (PDF). BNSF Corp. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2015. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- Carter, Thad Hills (2009). Kansas City Southern Railway. Images of Rail. (Reprint of an article by Philip Moseley originally published in the May 1986 issue of Arkansas Railroader). Charleston, SC; Chicago, IL; Portsmouth, NH; San Francisco, CA: Arcadia Publishing. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-7385-6001-4.

- "The Southern Belle". Louisiana Political Museum. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- The Associated Press. "Louisiana to seek New Orleans-Baton Rouge passenger rail line from federal stimulus pot that Jindal called wasteful". NOLA.com. Archived from the original on July 2, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- "Educator From Egypt Will Pay Visit to City". Baton Rouge Morning Advocate (sec. B, p. 11). February 10, 1952.

- "French Club Will Observe Bastile Day". Baton Rouge Morning Advocate (sec. D, p. 10). July 2, 1964.

- Bartels, Paul (February 26, 1976). "With Taichung, Taiwan: Sister City Relationship Endorsed by City Council". Baton Rouge Morning Advocate (sec. B, 1).

- "Sister City Fun: Dinner Honors Visitors Here on Mexican Exchange". Baton Rouge Morning Advocate (sec. B, p. 2). June 29, 1977.

- Smiley Anders (July 26, 1978). "Visiting Haitian Mayor Seeking Builders for Housing Projects". Baton Rouge Morning Advocate (sec. A, p. 12).