Battle of Valcour Island

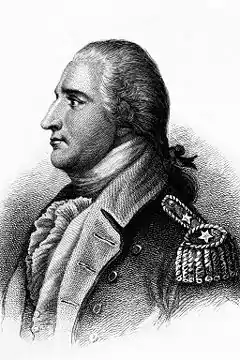

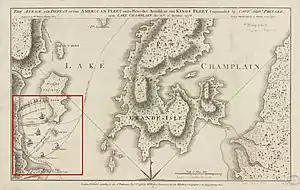

The Battle of Valcour Island, also known as the Battle of Valcour Bay, was a naval engagement that took place on October 11, 1776, on Lake Champlain. The main action took place in Valcour Bay, a narrow strait between the New York mainland and Valcour Island. The battle is generally regarded as one of the first naval battles of the American Revolutionary War, and one of the first fought by the United States Navy. Most of the ships in the American fleet under the command of Benedict Arnold were captured or destroyed by a British force under the overall direction of General Guy Carleton. However, the American defense of Lake Champlain stalled British plans to reach the upper Hudson River valley.

| Battle of Valcour Island | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

Battle of Valcour Island, Unknown artist | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1 sloop 2 schooners 1 radeau 1 gundalow 28 gunboats[3][4][5] |

4 galleys 2 schooners 1 sloop 8 gundalows[6][Note 1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

40 killed or wounded[7] 1 gunboat destroyed 2 gunboats sunk |

80 killed or wounded 120 captured 1 schooner destroyed 1 galley destroyed 2 galleys captured 3 gundalows destroyed 3 gundalows sunk 1 gundalow captured[8] | ||||||

The Continental Army had retreated from Quebec to Fort Ticonderoga and Fort Crown Point in June 1776 after British forces were massively reinforced. They spent the summer of 1776 fortifying those forts and building additional ships to augment the small American fleet already on the lake. General Carleton had a 9,000 man army at Fort Saint-Jean, but needed to build a fleet to carry it on the lake. The Americans, during their retreat, had either taken or destroyed most of the ships on the lake. By early October, the British fleet, which significantly outgunned the American fleet, was ready for launch.

On October 11, Arnold drew the British fleet to a position he had carefully chosen to limit their advantages. In the battle that followed, many of the American ships were damaged or destroyed. That night, Arnold sneaked the American fleet past the British one, beginning a retreat toward Crown Point and Ticonderoga. Unfavorable weather hampered the American retreat, and more of the fleet was either captured or grounded and burned before it could reach Crown Point. Upon reaching Crown Point Arnold had the fort's buildings burned and retreated to Ticonderoga.

The British fleet included four officers who later became admirals in the Royal Navy: Thomas Pringle, James Dacres, Edward Pellew, and John Schank. Valcour Bay, the site of the battle, is now a National Historic Landmark, as is Philadelphia, which sank shortly after the October 11 battle, and was raised in 1935. The underwater site of Spitfire, located in 1997, is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Background

The American Revolutionary War, which began in April 1775 with the Battles of Lexington and Concord, widened in September 1775 when the Continental Army embarked on an invasion of the British Province of Quebec. The province was viewed by the Second Continental Congress as a potential avenue for British forces to attack and divide the rebellious colonies and was at the time lightly defended. The invasion reached a peak on December 31, 1775, when the Battle of Quebec ended in disaster for the Americans. In the spring of 1776, 10,000 British and German troops arrived in Quebec, and General Guy Carleton, the provincial governor, drove the Continental Army out of Quebec and back to Fort Ticonderoga.[9]

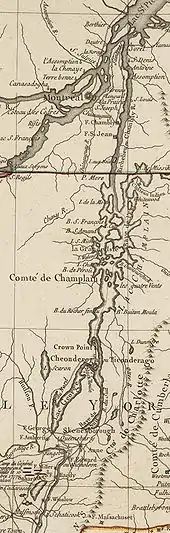

Carleton then launched his own offensive intended to reach the Hudson River, whose navigable length begins south of Lake Champlain and extends down to New York City. Control of the upper Hudson would enable the British to link their forces in Quebec with those in New York, recently captured in the New York campaign by Major General William Howe. This strategy would separate the American colonies of New England from those farther south and potentially quash the rebellion.[10] Lake Champlain, a long and relatively narrow lake formed by the action of glaciers during the last ice age, separates the Green Mountains of Vermont from the Adirondack Mountains of New York. Its 120-mile (190 km) length and 12-mile (19 km) maximum width creates more than 550 miles (890 km) of shoreline, with many bays, inlets, and promontories. More than 70 islands dot the 435-square-mile (1,130 km2) surface, although during periods of low and high water, these numbers can change. The lake is relatively shallow, with an average depth of 64 feet (20 m).[11] Flowing south to north, the lake empties into the Richelieu River, where waterfalls at Saint-Jean in Quebec mark the northernmost point of navigation.[12]

The American-held strongholds of Fort Crown Point and Fort Ticonderoga near the lake's southern end protected access to the uppermost navigable reaches of the Hudson River. Elimination of these defenses required the transportation of troops and supplies from the British-controlled St. Lawrence Valley 90 miles (140 km) to the north. Roads were either difficult or nonexistent, making water transport on the lake the best option.[13] The only ships on the lake after the American retreat from Quebec were a small fleet of lightly armed ships that Benedict Arnold had assembled following the capture of Fort Ticonderoga in May 1775. This fleet, even if it had been in British hands, was too small to transport the large British Army to Fort Ticonderoga.[14]

Prelude

During their retreat from Quebec, the Americans carefully took or destroyed all ships on Lake Champlain that might prove useful to the British. When Arnold and his troops, making up the rear guard of the army, abandoned Fort Saint-Jean, they burned or sank all the boats they could not use, and set fire to the sawmill and the fort. These actions effectively denied the British any hope of immediately moving onto the lake.[15]

The two sides set about building fleets: the British at Saint-Jean and the Americans at the other end of the lake in Skenesborough (present-day Whitehall, New York). While planning Quebec's defenses in 1775, General Carleton had anticipated the problem of transportation on Lake Champlain, and had requested the provisioning of prefabricated ships from Europe. By the time Carleton's army reached Saint-Jean, ten such ships had arrived. These ships and more were assembled by skilled shipwrights on the upper Richelieu River. Also assembled there was the Inflexible, a 180-ton warship they disassembled at Quebec City and transported upriver in pieces.[16][17] In total, the British fleet (25 armed vessels) had more firepower than the Americans' 15 vessels, with more than 80 guns outweighing the 74 smaller American guns.[18][19] Two of Carleton's ships, Inflexible (18 12-pounders) and Thunderer (six 24-pound guns, six 12-pound guns, and two howitzers), by themselves outgunned the combined firepower of the American fleet.[20] In addition to Inflexible and Thunderer, the fleet included the schooners Maria, (14 guns), Carleton (12 guns), and Loyal Convert (6 guns), and 20 single-masted gunboats each armed with two cannons.[16][19]

The American generals leading their shipbuilding effort encountered a variety of challenges. Shipwright was not a common occupation in the relative wilderness of upstate New York, and the Continental Navy had to pay extremely high wages to lure skilled craftsmen away from the coast. The carpenters hired to build boats on Lake Champlain were the best-paid employees of the navy, excepting only the Navy's Commodore, Esek Hopkins.[21] By the end of July there were more than 200 shipwrights at Skenesborough.[22] In addition to skilled help, materials and supplies specific to maritime use needed to be brought to Skenesborough, where the ships were constructed, or Fort Ticonderoga, where they were fitted out for use.[23]

The shipbuilding at Skenesborough was overseen by Hermanus Schuyler (possibly a relation of Major General Philip Schuyler), and the outfitting was managed by military engineer Jeduthan Baldwin. Schuyler began work in April to produce boats larger and more suitable for combat than the small shallow-draft boats known as bateaux that were used for transport on the lake. The process eventually came to involve General Arnold, who was an experienced ship's captain, and David Waterbury, a Connecticut militia leader with maritime experience. Major General Horatio Gates, in charge of the entire shipbuilding effort, eventually asked Arnold to take more responsibility in the effort, because "I am intirely uninform'd as to Marine Affairs."[24]

Arnold took up the task with relish, and Gates rewarded him with command of the fleet, writing that "[Arnold] has a perfect knowledge in maritime affairs, and is, besides, a most gallant and deserving officer."[25] Arnold's appointment was not without trouble; Jacobus Wynkoop, who had been in command of the fleet, refused to accept that Gates had authority over him and had to be arrested.[26] The shipbuilding was significantly slowed in mid-August by an outbreak of disease among the shipwrights. Although the army leadership had been scrupulous about keeping smallpox sufferers segregated from others, the disease that slowed the shipbuilding for several weeks was some kind of fever.[27]

While both sides busied themselves with shipbuilding, the growing American fleet patrolled the waters of Lake Champlain. At one point in August, Arnold sailed part of the fleet to the northernmost end of the lake, within 20 miles (32 km) of Saint-Jean, and formed a battle line. A British outpost, well out of range, fired a few shots at the line without effect. On September 30, expecting the British to sail soon, Arnold retreated to the shelter of Valcour Island.[28] During his patrols of the lake Arnold had commanded the fleet from the schooner Royal Savage, carrying 12 guns and captained by David Hawley. When it came time for the battle, Arnold transferred his flag to Congress, a row galley. Other ships in the fleet included Revenge and Liberty, also two-masted schooners carrying 8 guns, as well as Enterprise, a sloop (12 guns), and 8 gundalows outfitted as gunboats (each with three guns): New Haven, Providence, Boston, Spitfire, Philadelphia, Connecticut, Jersey, New York, the cutter Lee, and the row galleys Trumbull and Washington. Liberty was not present at the battle, having been sent to Ticonderoga for provisions.[29][30][31]

Arnold, whose business activities before the war had included sailing ships to Europe and the West Indies, carefully chose the site where he wanted to meet the British fleet.[32] Reliable intelligence he received on October 1 indicated that the British had a force significantly more powerful than his.[33] Because his force was inferior, he chose the narrow, rocky body of water between the western shore of Lake Champlain and Valcour Island (near modern Plattsburgh, New York), where the British fleet would have difficulty bringing its superior firepower to bear, and where the inferior seamanship of his relatively unskilled sailors would have a minimal negative effect.[34] Some of Arnold's captains wanted to fight in open waters where they might be able to retreat to the shelter of Fort Crown Point, but Arnold argued that the primary purpose of the fleet was not survival but the delay of a British advance on Crown Point and Ticonderoga until the following spring.[35]

Battle

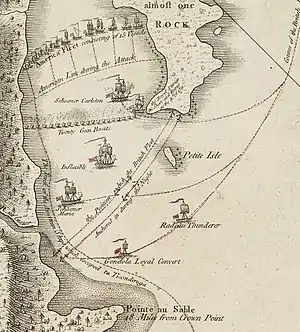

Carleton's fleet, commanded by Captain Thomas Pringle and including 50 unarmed support vessels, sailed onto Lake Champlain on October 9.[36] They cautiously advanced southward, searching for signs of Arnold's fleet. On the night of October 10, the fleet anchored about 15 miles (24 km) to the north of Arnold's position, still unaware of his location.[34] The next day, they continued to sail south, assisted by favorable winds. After they passed the northern tip of Valcour Island, Arnold sent out Congress and Royal Savage to draw the attention of the British. Following an inconsequential exchange of fire with the British, the two ships tried to return to Arnold's crescent-shaped firing line. However, Royal Savage was unable to fight the headwinds, and ran aground on the southern tip of Valcour Island.[37] Some of the British gunboats swarmed toward her, as Captain Hawley and his men hastily abandoned ship. Men from Loyal Convert boarded her, capturing 20 men in the process, but were then forced to abandon her under heavy fire from the Americans.[38] Many of Arnold's papers were lost with the destruction of Royal Savage, which was burned by the British.[37][39]

The British gunboats and Carleton then maneuvered within range of the American line. Thunderer and Maria were unable to make headway against the winds, and did not participate in the battle, while Inflexible eventually came far enough up the strait to participate in the action. Around 12:30 pm, the battle began in earnest, with both sides firing broadsides and cannonades at each other, and continued all afternoon. Revenge was heavily hit; Philadelphia was also heavily damaged and eventually sank around 6:30 pm. Carleton, whose guns wrought havoc against the smaller American gundalows, became a focus of attention. A lucky shot eventually snapped the line holding her broadside in position, and she was seriously damaged before she could be towed out of range of the American line. Her casualties were significant; eight men were killed and another eight wounded.[40] The young Edward Pellew, serving as a midshipman aboard Carleton, distinguished himself by ably commanding the vessel to safety when its senior officers, including its captain, Lieutenant James Dacres, were injured.[41] Another lucky American shot hit a British gunboat's magazine and the vessel exploded.[42]

Toward sunset, Inflexible finally reached the action. Her big guns quickly silenced most of Arnold's fleet. The British also began landing Native allies on both Valcour Island and the lakeshore, in order to deny the Americans the possibility of retreating to land. As darkness fell, the American fleet retreated, and the British called off the attack, in part because some boats had run out of ammunition.[42] Lieutenant James Hadden, commanding one of the British gunboats, noted that "little more than one third of the British Fleet" saw much action that day.[39]

Retreat

When the sun set on October 11, the battle had clearly gone against the Americans. Most of the American ships were damaged or sinking, and the crews reported around 60 casualties.[42] The British reported around 40 casualties on their ships.[7] Aware that he could not defeat the British fleet, Arnold decided to try reaching the cover of Fort Crown Point, about 35 miles (56 km) to the south. Under the cover of a dark and foggy night, the fleet, with muffled oars and minimal illumination, threaded its way through a gap about one mile (1.6 km) wide between the British ships and the western shore, where Indian campfires burned.[43] By morning, they had reached Schuyler Island, about 8 miles (13 km) south. Carleton, upset that the Americans had escaped him, immediately sent his fleet around Valcour Island to find them. Realizing the Americans were not there, he regrouped his fleet and sent scouts to find Arnold.[44]

Adverse winds as well as damaged and leaky boats slowed the American fleet's progress. At Schuyler Island, Providence and Jersey were sunk or burned, and crude repairs were effected to other vessels.[45] The cutter Lee was also abandoned on the western shore and eventually taken by the British.[46] Around 2:00 pm, the fleet sailed again, trying to make headway against biting winds, rain, and sleet. By the following morning, the ships were still more than 20 miles (32 km) from Crown Point, and the British fleet's masts were visible on the horizon. When the wind finally changed, the British had its advantage first. They closed once again, opening fire on Congress and Washington, which were in the rear of the American fleet. Arnold first decided to attempt grounding the slower gunboats at Split Rock, 18 miles (29 km) short of Crown Point. Washington, however, was too badly damaged and too slow to make it, and she was forced to strike her colors and surrender; 110 men were taken prisoner.[45]

Arnold then led many of the remaining smaller craft into a small bay on the Vermont shore now named Arnold's Bay 2 miles south of Buttonmold Bay, where the waters were too shallow for the larger British vessels to follow. These boats were then run aground, stripped, and set on fire, with their flags still flying. Arnold, the last to land, personally torched his flagship Congress.[47] The surviving ships' crews, numbering about 200, then made their way overland to Crown Point, narrowly escaping an Indian ambush. There they found Trumbull, New York, Enterprise, and Revenge, all of which had escaped the British fleet, as well as Liberty, which had just arrived with supplies from Ticonderoga.[48]

Aftermath

Arnold, convinced that Crown Point was no longer viable as a point of defense against the large British force, destroyed and abandoned the fort, moving the forces stationed there to Ticonderoga. General Carleton, rather than shipping his prisoners back to Quebec, returned them to Ticonderoga under a flag of truce. On their arrival, the released men were so effusive in their praise of Carleton that they were sent home to prevent the desertion of other troops.[8]

With control of the lake, the British landed troops and occupied Crown Point the next day.[48] They remained for two weeks, pushing scouting parties to within three miles (4.8 km) of Ticonderoga.[49] The battle-season was getting late as the first snow began to fall on October 20 and his supply line would be difficult to manage in winter, so Carleton decided to withdraw north to winter quarters; Arnold's plan of delay had succeeded. Baron Riedesel, commanding the Hessians in Carleton's army, noted that, "If we could have begun our expedition four weeks earlier, I am satisfied that everything could have ended this year."[50]

The 1777 British campaign, led by General John Burgoyne, was halted by Continental forces, some led with vigor by General Arnold, in the Battles of Saratoga. Burgoyne's subsequent surrender paved the way for the entry of France into the war as an American ally.[51]

The captains of Maria, Inflexible, and Loyal Convert wrote a letter criticizing Captain Pringle for making Arnold's escape possible by failing to properly blockade the channel, and for not being more aggressive in directing the battle. Apparently the letter did not cause any career problems for Pringle or its authors; he and John Schank, captain of Inflexible, became admirals, as did midshipman Pellew and Lieutenant Dacres.[52] Carleton was awarded the Order of the Bath by King George III for his success at Valcour Island.[8] On December 31, 1776, one year after the Battle of Quebec, a mass was held in celebration of the British success, and Carleton threw a grand ball.[49]

The loss of Benedict Arnold's papers aboard Royal Savage was to have important consequences later in his career. For a variety of reasons, Congress ordered an inquiry into his conduct of the Quebec campaign, which included a detailed look at his claims for compensation. The inquiry took place in late 1779, when Arnold was in military command of Philadelphia and recuperating from serious wounds received at Saratoga. Congress found that he owed it money since he could not produce receipts for expenses he claimed to have paid from his own funds.[53] Although Arnold had already been secretly negotiating with the British over a change of allegiance since May 1779, this news contributed to his decision to resign the command of Philadelphia.[54] His next command was West Point, which he sought with the intention of facilitating its surrender to the British.[55] His plot was however exposed in September 1780, at which time he fled to the British in New York City.[56]

Legacy

In the 1930s, Lorenzo Hagglund, a veteran of World War I and a history buff, began searching the strait for remains of the battle. In 1932 he found the remains of Royal Savage's hull, which he successfully raised in 1934.[57][58] Stored for more than fifty years, the remains were sold by his son to the National Civil War Museum.[59][60] As of March 2009, the remains were in a city garage in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The city of Plattsburgh, New York, has claimed ownership of the remains and would like them returned to upstate New York.[60]

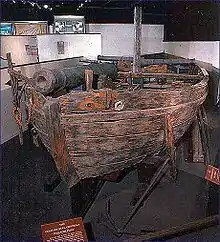

In 1935 Hagglund followed up his discovery of Royal Savage with the discovery of Philadelphia's remains, sitting upright on the lake bottom.[61] He raised her that year; she is now on display at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.,[42] and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is designated a National Historic Landmark.[62][63] The site of the battle, Valcour Bay, was declared a National Historic Landmark on January 1, 1961, and added to the National Register on October 15, 1966. A small stone monument commemorating the battle sits on the mainland along U.S. Route 9 overlooking Valcour Island.[62][64]

In 1997 another pristine underwater wreck was located during a survey by the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum. Two years later it was conclusively identified as the gundalow Spitfire; this site was listed on the National Register in 2008, and it has been named as part of the U.S. government's Save America's Treasures program.[65]

Order of battle

| Ship (type, guns) | Commander | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Enterprise (sloop, 12) | James Smith[66] | Hospital ship, escaped |

| Royal Savage (schooner, 12) | David Hawley[67] | Ran aground and burned October 11 |

| Trumbull (row galley, 10) | Seth Warner (left flag, Edward Wigglesworth)[68] | Escaped Called Schuyler prior to launch Also referred to as Trumble |

| Washington (row galley, 10) | John Thatcher (right flag, David Waterbury)[69] | Damaged October 11 Captured October 13 |

| Revenge (schooner, 8) | Isaac Seamon[70] | Escaped |

| Congress (row galley, 8) | James Arnold (flagship, Benedict Arnold)[71][72] | Ran aground and burned October 13 |

| Lee (row galley, 6) | Captain Daviss[73] | Ran aground October 13 Recovered by British |

| Boston (gundalow, 3) | Captain Sumner[74] | Ran aground and burned October 13 |

| Connecticut (gundalow, 3) | Joshua Grant[74] | Ran aground and burned October 13 |

| Jersey (gundalow, 3) | Captain Grimes[75] | Abandoned October 13 Recovered by British Also referred to as New Jersey |

| New Haven (gundalow, 3) | Samuel Mansfield[74] | Ran aground and burned October 13 |

| New York (gundalow, 3) | Captain Lee[76] | Cannon exploded[77][78] Escaped Called Success prior to launch |

| Philadelphia (gundalow, 3) | Benjamin Rue[79] | Sank October 11 Raised 1935 |

| Providence (gundalow, 3) | Isaiah Simonds[80] | Sank October 13 |

| Spitfire (gundalow, 3) | Philip Ulmer[74] | Sank October 12 near Schuyler Island; wreck located in 1997[65] |

| Ship descriptions and dispositions (but not captains) provided by Silverstone (2006), pp. 15–16, unless otherwise cited. Ship captains are all as cited. | ||

| Ship (type, guns) | Commander | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Inflexible (square-rigged ship, 22) | John Schank | Participated in later stages of battle |

| Thunderer (ketch-radeau, 18)[Note 2] | George Scott | Did not participate in main action |

| Maria (schooner, 14) | John Starke (flagship, Pringle and Carleton) | Did not participate in main action |

| Carleton (schooner, 12) | James Dacres | Heavily damaged October 11 |

| Loyal Convert (gundalow, 7) | Edward Longcroft | Also called Royal Convert or Loyal Consort[Note 3] |

| 28 unnamed gunboats (gunboat, 1) | unknown | One destroyed October 11; many others damaged, two lost after action |

| Ship descriptions and dispositions are from Nelson (2006), p. 33. Note that from the early beginnings of the U.S. Navy there had been no standard method of referring to U.S. Navy ships until 1907, when President Theodore Roosevelt issued Executive Order 549 on 8 January stating that all US Navy ships were to be referred to as "The name of such vessel, preceded by the words, United States Ship, or the letters U.S.S., and by no other words or letters".[81] | ||

See also

- List of American Revolutionary War battles

- American Revolutionary War §Early Engagements. The Battle of Valcour Island placed in sequence and strategic context.

Notes

- Arnold writes in a dispatch (Bratten (2002), p. 53) that he has about 500 "half naked" sailors. An analysis of his fleet (Bratten (2002), p. 57) indicates that ideal strength to fully man it was closer to 800, another figure that is sometimes cited.

- Thunderer was basically a keelless raft rigged as a ketch.

- Malcolmson (2001), on page 27 shows an image of a contemporary British draft document describing the Loyal Convert, where it is clearly readable by that name.

References

- Schroeder (2005), p. 12

- Phillips (1999), p. 152

- Hadden, James Murray (1884). Hadden's Journal and Orderly Books. A Journal Kept in Canada and Upon Burgoyne's Campaign in 1776 and 1777 (Reprinted ed.). Albany, NY: Joel Munsell's Sons. p. 22. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- Bratten (2002), p. 59

- Bratten (2002), p. 58

- Hadden, James Murray (1884). Hadden's Journal and Orderly Books. A Journal Kept in Canada and Upon Burgoyne's Campaign in 1776 and 1777 (Reprinted ed.). Albany, NY: Joel Munsell's Sons. pp. 16, 22. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- Allen (1913), p. 176

- Miller (1974), p. 178

- For detailed treatment of the background, see e.g. Stanley (1973) or Morrissey (2003).

- Hamilton (1964) pp. 17–18

- Lake Champlain Basin Fact Sheet#3

- Ketchum (1997), pp. 29–31

- Hamilton (1964), pp. 7,8,18

- Malcolmson (2001), p. 26

- Stanley (1973), pp. 131–132

- Silverstone (2006), p. 15

- Stanley (1973), pp. 133–136

- Silverstone (2006), pp. 15–16

- Stanley (1973), pp. 137–138

- Miller (1974), p. 170

- Nelson (2006), p. 231

- Nelson (2006), p. 241

- Nelson (2006), p. 239

- Nelson (2006), p. 243

- Nelson (2006), p. 245

- Nelson (2006), p. 261

- Nelson (2006), pp. 252–253

- Miller (1974), p. 171

- Malcolmson (2001), pp. 29–33

- Miller (1974), pp. 169, 172

- Bratten (2002), p. 57

- Miller (1974), pp. 166,171

- Bratten (2002), p. 56

- Stanley (1973), p. 141

- Miller (1974), p. 172

- Stanley (1973), p. 137

- Miller (1974), p. 173

- Bratten (2002), pp. 60–61

- Stanley (1973), p. 142

- Miller (1974), p. 174

- Hamilton (1964), p. 157

- Miller (1974), p. 175

- Nelson (2006), pp. 307–309

- Miller (1974), p. 176

- Miller (1974), p. 177

- Bratten (2002), p. 67

- Bratten (2002), p. 69

- Bratten (2002), p. 70

- Stanley (1973), p. 144

- Miller (1974), p. 179

- See e.g. Ketchum (1997) for a treatment of Burgoyne's campaign.

- Hamilton (1964), p. 160

- Randall (1990), pp. 497–499

- Randall (1990), pp. 456–457,499

- Randall (1990), pp. 508–509

- Martin (1997), pp. 1–4

- Bratten (2002), p. 75

- "Arnold's Flagship Raised On Old Tar Drums" Popular Mechanics, June 1935

- Bratten (2002), p. 76

- "War Ship Remains Piled in City Garage"

- Bratten (2002), p. 77

- National Register Information System

- NHL Description of USS Philadelphia

- NHL Description of Valcour Bay

- Shipwrecks of Lake Champlain: Gunboat Spitfire

- Nelson (2006), p. 70

- Nelson (2006), p. 297

- Nelson (2006), p. 258

- Nelson (2006), p. 284

- Nelson (2006), p. 256

- Bratten (2002), p. 204

- Nelson (2006), p. 295

- Bulletin of the New York State Museum, Issue 313 (1937), p. 135

- Nelson (2006), p. 263

- Nelson (2006), p. 312

- Nelson (2006), p. 279

- Cohn et al. (2007)

- America's Historic Lakes

- Nelson (2006), p. 262

- Nelson (2006), p. 255

- "USN Ship Naming". Naval History & Heritage Command. 29 September 1997. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2009.

Bibliography

- Allen, Gardner W (1913). A Naval History of the American Revolution. Vol. 1. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 2613121.

- Bratten, John R (2002). The Gondola Philadelphia and the Battle of Lake Champlain. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-147-1. OCLC 48003125.

- Cohn, Arthur B.; Kane, Adam I.; Sabick, Christopher R.; Scollon, Edwin R.; Clement, Justin B. (March 2007). "Valcour Bay Research Project: 1999–2004 Results from the Archaeological Investigation of a Revolutionary War Battlefield in Lake Champlain, Clinton County, New York" (PDF). Lake Champlain Maritime Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 16, 2012. Retrieved 2016-04-17.

- Hadden, James Murray (1884). Hadden's Journal and Orderly Books. A Journal Kept in Canada and Upon Burgoyne's Campaign in 1776 and 1777 (Reprinted ed.). Albany, NY: Joel Munsell's Sons. pp. 16, 22. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- Hamilton, Edward (1964). Fort Ticonderoga, Key to a Continent. Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 965281.

- Ketchum, Richard M (1997). Saratoga: Turning Point of America's Revolutionary War. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-6123-9. OCLC 41397623.

- Martin, James Kirby (1997). Benedict Arnold: Revolutionary Hero (An American Warrior Reconsidered). New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-5560-7. (This book is primarily about Arnold's service on the American side in the Revolution, giving overviews of the periods before the war and after he changes sides.)

- Nelson, James L (2006). Benedict Arnold's Navy. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-146806-0. OCLC 255396879.

- Malcolmson, Robert (2001). Warships of the Great Lakes 1754–1834. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-910-7. OCLC 47213837. (This work contains detailed specifications for most of the watercraft used in this action, as well as copies of draft documents for some of them.)

- Miller, Nathan (1974). Sea of Glory: The Continental Navy fights for Independence. New York: David McKay. ISBN 0-679-50392-7. OCLC 844299.

- Morrissey, Brendan (2003). Quebec 1775: The American Invasion of Canada. Hook, Adam [translator]. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-681-2. OCLC 52359702.

- Phillips, Kevin (1999). The Cousins' Wars: Religion, Politics, and the Triumph of Anglo-America. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465013692.

- Randall, Willard Sterne (1990). Benedict Arnold: Patriot and Traitor. William Morrow and Inc. ISBN 1-55710-034-9.

- Schroeder, John H (2015). The Battle of Lake Champlain: A "Brilliant and Extraordinary Victory" Volume 49 of Campaigns and Commanders Series. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806149097.

- Silverstone, Paul H (2006). The Sailing Navy, 1775–1854. New York: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-415-97872-9. OCLC 63178925.

- Smith, Justin H (1907). Our Struggle for the Fourteenth Colony. Vol. 2. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 259236.

- Stanley, George (1973). Canada Invaded 1775–1776. Toronto: Hakkert. ISBN 978-0-88866-578-2. OCLC 4807930.

- Bulletin of the New York State Museum, Issue 313. Albany: New York State Museum. 1937. OCLC 1476727.

- "War Ship Remains Piled in City Garage". WHTM Television. 2009-03-03.

- "Fact Sheet #3" (PDF). Lake Champlain Basin Program. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-09-26. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- "National Historic Landmark summary listing – Philadelphia (gundelo)". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- "National Historic Landmark summary listing – Valcour Bay". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Shipwrecks of Lake Champlain: Gunboat Spitfire". Lake Champlain Maritime Museum. Archived from the original on 2010-07-07. Retrieved 2010-05-13.

- "The Battle of Valcour Island: A Burst Cannon Reflects a Moment in Time" (PDF). America's Historic Lakes. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2016-04-17.

Further reading

- Fowler Jr., William M (1976). Rebels Under Sail: The American Navy During the Revolution. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-0-684-14583-9. OCLC 1863602.

External links

Media related to Battle of Valcour Island at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Valcour Island at Wikimedia Commons