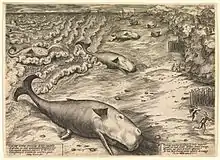

Cetacean stranding

Cetacean stranding, commonly known as beaching, is a phenomenon in which whales and dolphins strand themselves on land, usually on a beach. Beached whales often die due to dehydration, collapsing under their own weight, or drowning when high tide covers the blowhole.[1] Cetacean stranding has occurred since before recorded history.[2]

Several explanations for why cetaceans strand themselves have been proposed, including changes in water temperatures,[3] peculiarities of whales' echolocation in certain surroundings,[4] and geomagnetic disturbances,[5] but none have so far been universally accepted as a definitive reason for the behavior. However, a link between the mass beaching of beaked whales and use of mid-frequency active sonar has been found.[6]

Subsequently, whales that die due to stranding can decay and bloat to the point where they can easily explode, causing gas and their internal organs to fly out.

Species

.JPG.webp)

Every year, up to 2,000 animals beach themselves.[7] Although the majority of strandings result in death, they pose no threat to any species as a whole. Only about ten cetacean species frequently display mass beachings, with ten more rarely doing so.

All frequently involved species are toothed whales (Odontoceti), rather than baleen whales (Mysticeti). These species share some characteristics which may explain why they beach.

Body size does not normally affect the frequency, but both the animals' normal habitat and social organization do appear to influence their chances of coming ashore in large numbers. Odontocetes that normally inhabit deep waters and live in large, tightly knit groups are the most susceptible. This includes the sperm whale, oceanic dolphins, usually pilot and killer whales, and a few beaked whale species. The most common species to strand in the United Kingdom is the harbour porpoise; the common dolphin (Delphinus delphis) is second-most common, and after that long-finned pilot whales (Globicephala melas).[8]

Solitary species naturally do not strand en masse. Cetaceans that spend most of their time in shallow, coastal waters almost never mass strand.

Causes

Strandings can be grouped into several types. The most obvious distinction is between single and multiple strandings. Many theories, some of them controversial, have been proposed to explain beaching, but the question remains unresolved.

- Natural deaths at sea

- The carcasses of deceased cetaceans are likely to float to the surface at some point; during this time, currents or winds may carry them to a coastline. Since thousands of cetaceans die every year, many become stranded posthumously. Most carcasses never reach the coast, and are scavenged, or decompose enough to sink to the ocean bottom, where the carcass forms the basis of a unique local ecosystem called a whale fall.

- Individual strandings

- Single live strandings are often the result of individual illness or injury; in the absence of human intervention these almost always inevitably end in death.

- Multiple strandings

- Multiple strandings in one place are rare, and often attract media coverage as well as rescue efforts. The strong social cohesion of toothed whale pods appears to be a key factor in many cases of multiple stranding: If one gets into trouble, its distress calls may prompt the rest of the pod to follow and beach themselves alongside.[9]

Even multiple offshore deaths are unlikely to lead to multiple strandings, since winds and currents are variable, and will scatter a group of corpses.

Environmental

Whales have beached throughout human history, with evidence of humans salvaging from stranded sperm whales in southern Spain during the Upper Magdalenian era some 14,000 years before the present.[2] Some strandings can be attributed to natural and environmental factors, such as rough weather, weakness due to old age or infection, difficulty giving birth,[9] hunting too close to shore, or navigation errors.

In 2004, scientists at the University of Tasmania linked whale strandings and weather, hypothesizing that when cool Antarctic waters rich in squid and fish flow north, whales follow their prey closer towards land.[3] In some cases predators (such as killer whales) have been known to panic other whales, herding them towards the shoreline.[3]

Their echolocation system can have difficulty picking up very gently-sloping coastlines.[10] This theory accounts for mass beaching hot spots such as Ocean Beach, Tasmania and Geographe Bay, Western Australia where the slope is about half a degree (approximately 8 m [26 ft] deep one km [0.62 mi] out to sea). The University of Western Australia Bioacoustics group proposes that repeated reflections between the surface and ocean bottom in gently sloping shallow water may attenuate sound so much that the echo is inaudible to the whales.[4] Stirred up sand as well as long-lived microbubbles formed by rain may further exacerbate the effect.

A 2017 study by scientists from Germany's University of Kiel suggests that large geomagnetic disruptions of the Earth's magnetic field, brought on through solar storms, could be another cause for whale beachings.[5] The authors hypothesize that whales navigate using the Earth's magnetic field by detecting differences in the field's strength to find their way. The solar storms cause anomalies in the field, which may disturb the whales' ability to navigate, sending them into shallow waters where they get trapped.[5] The study is based on the mass beachings of 29 sperm whales along the coasts of Germany, the Netherlands, the UK and France in 2016.[5]

"Follow-me" strandings

.jpg.webp)

Some strandings may be caused by larger cetaceans following dolphins and porpoises into shallow coastal waters. The larger animals may habituate to following faster-moving dolphins. If they encounter an adverse combination of tidal flow and seabed topography, the larger species may become trapped.

Sometimes following a dolphin can help lead a whale out of danger: In 2008, a local dolphin was followed out to open water by two pygmy sperm whales that had become lost behind a sandbar at Mahia Beach, New Zealand.[11] It may be possible to train dolphins to lead trapped whales out to sea.

Orcas' intentional, temporary strandings

Pods of killer whales – predators of dolphins and porpoises – very rarely strand. It might be that killer whales have learned to stay away from shallow waters, and that heading to the shallows offers the smaller animals some protection from predators. However, killer whales in Península Valdés, Argentina, and the Crozet Islands in the Indian Ocean have learned how to operate in shallow waters, particularly in their pursuit of seals. The killer whales regularly demonstrate their competence by chasing seals up shelving gravel beaches, up to the edge of the water. The pursuing whales are occasionally partially thrust out of the sea by a combination of their own impetus and retreating water, and have to wait for the next wave to re-float them and carry them back to sea.[12]

In Argentina, killer whales are known to hunt on the shore by intentionally beaching themselves and then lunging at nearby seals before riding the next wave safely back into deeper waters. This was first observed in the early 1970s, then hundreds times more since within this pod. This behavior seems to be taught from one generation to the next, evidenced by older individuals nudging juveniles towards the shore, and can sometimes also be a play activity.[12][13][14]

Sonar

There is evidence that active sonar leads to beaching. On some occasions cetaceans have stranded shortly after military sonar was active in the area, suggesting a link.[6] Theories describing how sonar may cause whale deaths have also been advanced after necropsies found internal injuries in stranded cetaceans. In contrast, some who strand themselves due to seemingly natural causes are usually healthy prior to beaching:

The low frequency active sonar (LFA sonar) used by the military to detect submarines is the loudest sound ever put into the seas. Yet the U.S. Navy is planning to deploy LFA sonar across 80 percent of the world ocean. At an amplitude of two hundred forty decibels, it is loud enough to kill whales and dolphins and has already caused mass strandings and deaths in areas where U.S. and/or NATO forces have conducted exercises.

Direct injury

The large and rapid pressure changes made by loud sonar can cause hemorrhaging. Evidence emerged after 17 cetaceans were hauled out in the Bahamas in March 2000 following a United States Navy sonar exercise. The Navy accepted blame agreeing that the dead whales experienced acoustically induced hemorrhages around the ears.[6] The resulting disorientation probably led to the stranding. Ken Balcomb, a cetologist, specializes in the killer whale populations that inhabit the Strait of Juan de Fuca between Washington and Vancouver Island.[15] He investigated these beachings and argues that the powerful sonar pulses resonated with airspaces in the dolphins, tearing tissue around the ears and brain.[16] Apparently not all species are affected by sonar.[17]

Injury at a vulnerable moment

Another means by which sonar could be hurting cetaceans is a form of decompression sickness. This was first raised by necrological examinations of 14 beaked whales stranded in the Canary Islands. The stranding happened on 24 September 2002, close to the operating area of Neo Tapon (an international naval exercise) about four hours after the activation of mid-frequency sonar.[18] The team of scientists found acute tissue damage from gas-bubble lesions, which are indicative of decompression sickness.[18] The precise mechanism of how sonar causes bubble formation is not known. It could be due to cetaceans panicking and surfacing too rapidly in an attempt to escape the sonar pulses. There is also a theoretical basis by which sonar vibrations can cause supersaturated gas to nucleate, forming bubbles, which are responsible for decompression sickness.[19]

Diving patterns of Cuvier's beaked whales

The overwhelming majority of the cetaceans involved in sonar-associated beachings are Cuvier's beaked whales (Ziphius cavirostrus). Individuals of this species strand frequently, but mass strandings are rare.

Cuvier's beaked whales (Ziphius cavirostrus) are an open-ocean species that rarely approach the shore, making them difficult to study in the wild. Prior to the interest raised by the sonar controversy, most of the information about them came from stranded animals. The first to publish research linking beachings with naval activity were Simmonds and Lopez-Jurado in 1991. They noted that over the past decade there had been a number of mass strandings of beaked whales in the Canary Islands, and each time the Spanish Navy was conducting exercises. Conversely, there were no mass strandings at other times. They did not propose a theory for the strandings. Fernández et al. in a 2013 letter to Nature, reported that there had been no further mass strandings in that area, following a 2004 ban by the Spanish government on military exercises in that region.[20]

In May 1996, there was another mass stranding in West Peloponnese, Greece. At the time, it was noted as "atypical" both because mass strandings of beaked whales are rare, and also because the stranded whales were spread over such a long stretch of coast, with each individual whale spatially separated from the next stranding. At the time of the incident, there was no connection made with active sonar; A. Frantzis, the marine biologist investigating the incident, made the connection to sonar because he discovered a notice to mariners concerning the test. His report was published in March 1998.[21]

Peter Tyack, of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, has been researching noise's effects on marine mammals since the 1970s. He has led much of the recent research on beaked whales (Cuvier's beaked whales in particular). Data tags have shown that Cuvier's dive considerably deeper than previously thought, and are in fact the deepest-diving species of marine mammal yet known.

At shallow depths Cuvier's stop vocalizing, either because of fear of predators, or because they don't need vocalization to track each other at shallow depths, where they have light adequate to see each other.

Their surfacing behavior is highly unusual, because they exert considerable physical effort to surface by a controlled ascent, rather than passively floating to the surface as sperm whales do. Every deep dive is followed by three or four shallow dives. The elaborate dive patterns are assumed to be necessary to control the diffusion of gases in the bloodstream. No data show a beaked whale making an uncontrolled ascent, or failing to do successive shallow dives. This behavior suggests that the Cuvier's are in a vulnerable state after a deep dive – presumably on the verge of decompression sickness – and require time and perhaps the shallower dives to recover.

Summary review

De Quirós et al. (2019)[22] published a review of evidence on the mass strandings of beaked whale linked to naval exercises where sonar was used. It concluded that the effects of mid-frequency active sonar are strongest on Cuvier's beaked whales but vary among individuals or populations. The review suggested the strength of response of individual animals may depend on whether they had prior exposure to sonar, and that symptoms of decompression sickness have been found in stranded whales that may be a result of such response to sonar. It noted that no more mass strandings had occurred in the Canary Islands once naval exercises where sonar was used were banned, and recommended that the ban be extended to other areas where mass strandings continue to occur.[22][23]

Disposal

If a whale is beached near an inhabited locality, the rotting carcass can pose a nuisance as well as a health risk. Such very large carcasses are difficult to move. The whales are often towed back out to sea away from shipping lanes, allowing them to decompose naturally, or they are towed out to sea and blown up with explosives. Government-sanctioned explosions have occurred in South Africa, Iceland, Australia and United States.[24][25][26] If the carcass is older, it is buried.

In New Zealand, which is the site of many whale strandings, treaties with the indigenous Māori people allow the tribal gathering and customary (that is, traditional) use of whalebone from any animal which has died as a result of stranding. Whales are regarded as taonga (spiritual treasure), descendants of the ocean god, Tangaroa, and are as such held in very high respect. Sites of whale strandings and any whale carcasses from strandings are treated as tapu sites, that is, they are regarded as sacred ground.[27]

Health risks

A beached whale carcass should not be consumed. In 2002, fourteen Alaskans ate muktuk (whale blubber) from a beached whale, resulting in eight of them developing botulism, with two of the affected requiring mechanical ventilation.[28] This is a possibility for any meat taken from an unpreserved carcass.

Large strandings

This is a list of large cetacean strandings (200 or more).

| Total | Deaths | Survived | Date | Incident | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | 1,000 | 0 | 1918 | Largest pilot whale stranding ever recorded.[29] | |

| 656 | 335 | 321 | 2017 | About 650 pilot whales beached themselves at the top of South Island, killing 335 of them. The others were able to swim away at high tide or were refloated by volunteers.[30][31][32] | |

| 500+ | 500+ | 0 | 1897 | More than 500 pilot whales died at Teal Inlet.[33] | |

| 470 | 362 | 108 | 2020 | About 270 pilot whales were found at Macquarie Heads on September 21, followed by the discovery of 200 dead whales two days later about 10 kilometers south, raising the total to 470. Only 108 were rescued.[34][35] | |

| ±300 | ±75 | ±225 | 1985 | Nearly 300 pilot whales ran aground on Great Barrier Island, killing about one-quarter of them. Local residents, who had received rescue lectures after a similar incident the previous year, helped rescue more than 200 whales at high tide.[36] | |

| 294 | 245 | 49+ | 1935 | Around 300 pilot whales were stranded at Stanley, Tasmania.[37][38][39] The exact number of deaths or whales involved is unclear, with one newspaper reporting at least 245 confirmed deaths,[40] while another newspaper reported in 1936 that 70 whales escaped during high tide the day after the stranding.[41] | |

| 253 | 253 | 0 | 1978 | More than 250 false killer whales stranded and died near Pukekohe.[42] | |

| 240 | 240 | 0 | 2022 | About 240 pilot whales beached themselves at Walhere Bay on Pitt Island, just 3 days after 240 pilot whales beached themselves at nearby Chatham Island.[43] | |

| 240 | 240 | 0 | 2022 | About 240 pilot whales beached themselves in the northwest of Chatham Island, just 3 days before 240 whales beached themselves at nearby Pitt Island.[43] | |

| 230 | 195 | 35 | 2022 | About 230 pilot whales beached themselves on the west coast of Tasmania, exactly two years to the day of another mass stranding in the same area.[44] | |

Others

On June 23, 2015, 337 dead whales were discovered in a remote fjord in Patagonia, southern Chile, the largest stranding of baleen whales to date.[45] Three hundred and five bodies and 32 skeletons were identified by aerial and satellite photography between the Gulf of Penas and Puerto Natales, near the southern tip of South America. They may have been sei whales.[46] This is one of only two or three such baleen mass stranding events in the last hundred years. It is highly unusual for baleens to strand other than singly, and the Patagonia baleen strandings are tentatively attributed to an unusual cause such as ingestion of poisonous algae.

In November 2018, over 140 whales were witnessed stranded on a remote beach in New Zealand and had to be euthanised because of their declining health condition.[47] In July 2019, nearly 50 long-finned pilot whales were found stranded on Snaefellsnes Peninsula in Iceland. However, they were already dead when spotted.[48]

On the evening of November 2, 2020, over 100 short-finned pilot whales were stranded on the Panadura Beach in western coast of Sri Lanka.[49] Although four deaths were reported, all other whales were rescued.[50]

See also

- Cetacean strandings in Ghana

- Cetacean strandings in Tasmania

- Dolphin drive hunting, a technique which herds small cetaceans towards the shore for slaughter

- Drift whale

- Marine Mammal Stranding Center – New Jersey, United States

- Saint-Clément-des-Baleines – A coastal area on French island Île de Ré named after mass strandings of whales

- Golden Bay, New Zealand – A renowned area for pilot whale mass strandings on Farewell Spit in Cook Strait

- Whaling

References

- Blood, Matt D. (2012). Beached Whales: A Personal Encounter. Sydney.

- Álvarez-Fernández, Esteban; Carriol, René-Pierre; Jordá, Jesús F.; Aura, J. Emili; Avezuela, Bárbara; Badal, Ernestina; Carrión, Yolanda; García-Guinea, Javier; Maestro, Adolfo; Morales, Juan V.; Perez, Guillém; Perez-Ripoll, Manuel; Rodrigo, María J.; Scarff, James E.; Villalba, M. Paz; Wood, Rachel (2014). "Occurrence of whale barnacles in Nerja Cave (Málaga, southern Spain): Indirect evidence of whale consumption by humans in the Upper Magdalenian". Quaternary International. 337: 163–169. Bibcode:2014QuInt.337..163A. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.01.014. hdl:10550/36217. ISSN 1040-6182.

- R. Gales; K. Evans; M. Hindell (2004-11-30). "Whale strandings no surprise to climatologists". 7:30 report. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original (TV transcript) on 2007-12-15. Retrieved 2006-12-02.

- Chambers, S.; James, R.N. (9 November 2005). "Sonar termination as a cause of mass cetacean strandings in Geographe Bay, south-western Australia" (PDF). Acoustics 2005, Acoustics in a Changing Environment. Annual Conference of the Australian Acoustical Society. Busselton, Western Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2006. Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- McGrath, Matt (2017-09-05). "Northern lights linked to North Sea whale strandings". BBC News. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

- Bahamas Marine Mammal Stranding Event of 15–16 March 2000 (PDF) (Report). Joint Interim Report. December 2001. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- Martin, Anthony R. (1991). Whales and Dolphins. London: Salamander Books Ltd. ISBN 0-8160-3922-4.

- Coombs, Ellen J.; Deaville, Rob; Sabin, Richard C.; Allan, Louise; O'Connell, Mick; Berrow, Simon; Smith, Brian; Brownlow, Andrew; Doeschate, Mariel Ten; Penrose, Rod; Williams, Ruth (2019). "What can cetacean stranding records tell us? A study of UK and Irish cetacean diversity over the past 100 years". Marine Mammal Science. 35 (4): 1527–1555. doi:10.1111/mms.12610. hdl:10141/622700. ISSN 0824-0469. S2CID 198236986.

- van Helden, Anton (2003-11-26). Mass whale beaching mystery solved (radio transcript). The Word Today. Australian Broadcast Corporation. Retrieved 2006-12-01.

- Montgomery, B. (1998-05-02). "The fatal shore". The Weekend Australian Magazine. Archived from the original on 2006-10-04. Retrieved 2006-12-03 – via University of Western Australia, Biophysics Dept.

- "Dolphin rescues stranded whales". CNN. The Associated Press. 2008-03-12. Archived from the original on 2008-03-13. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- Baird, Robin W. (2002). Killer Whales of the World. Stillwater, MN: Voyageur Press. p. 24.

- Guinet, C. (1991). "Intentional stranding apprenticeship and social play in killer whales (Orcinus orca)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 69 (1): 2712–2716. doi:10.1139/z91-383.

- Kaplan, Matt (2007). "Unique orca hunting-technique documented". Nature. News. doi:10.1038/news.2007.380.

- Balcomb, Ken (2003-05-12). "U.S. Navy sonar blasts Pacific Northwest killer whales". San Juan Islander. Archived from the original on 23 May 2006. Retrieved 2006-04-30.

- Balcomb, Ken (2001-02-23). "Letter". Ocean Mammal Institute. Archived from the original on 25 May 2006. Retrieved 2006-04-30.

- Borrell, Brendan (1 June 2009). "Why do whales beach themselves?". Scientific American. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- Jepson, P.D.; Arbelo, M.; Deaville, R.; Patterson, I.A.P.; Castro, P.; Baker, J.R.; et al. (9 October 2003). "Gas-bubble lesions in stranded cetaceans". Nature. 425 (6958): 575–576. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..575J. doi:10.1038/425575a. PMID 14534575. S2CID 26717950.

- Houser, D.S.; Howards, R.; Ridgway, S. (21 November 2001). "Can diving-induced tissue nitrogen supersaturation increase the chance of acoustically driven bubble growth in marine mammals?". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 213 (2): 183–195. Bibcode:2001JThBi.213..183H. doi:10.1006/jtbi.2001.2415. PMID 11894990.

- Fernández, A.; Arbelo, M.; Martín, V. (2013). "Whales: No mass strandings since sonar ban". Nature. 497 (7449): 317. Bibcode:2013Natur.497..317F. doi:10.1038/497317d. PMID 23676745.

- Frantzis, A. (1988-03-05). "Does acoustic testing strand whales?". Nature. 392 (6671): 29. doi:10.1038/32068. PMID 9510243. S2CID 205001662.

- Bernaldo de Quirós, Y.; Fernandez, A.; Baird, R.W.; Brownell, Jr., R.L.; Aguilar de Soto, N.; Allen, D.; Arbelo, M.; Arregui, M.; Costidis, A.; Fahlman, A.; Frantzis, A.; Gulland, F.M.D.; Iñíguez, M.; Johnson, M.; Komnenou, A.; Koopman, H.; Pabst, D.A.; Roe, W.D.; Sierra, E.; Tejedor, M.; Schorr, G. (30 January 2019). "Advances in research on the impacts of anti-submarine sonar on beaked whales". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 286 (1895): 20182533. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.2533. PMC 6364578. PMID 30963955.

- Batchelor, Tom (30 January 2019). "Scientists demand military sonar ban to end mass whale strandings". The Independent.

- "Exploding Whale - Whale Of A Tale". 29 April 2011. Archived from the original on 2021-11-18 – via YouTube.

- "Hvalhræ dregið út á haf og síðan aftur upp í fjöru" [Whale pulled out to sea and then back up the beach]. mbl.is (in Icelandic). June 5, 2005. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- "Explosive end for sick whale". ABC News. September 2, 2010. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- Te Karaka, "The science of strandings', Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, 21 December 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- Middaugh, J; Funk, B; Jilly, B; Maslanka, S; McLaughlin J (2003-01-17). "Outbreak of Botulism Type E Associated with Eating a Beached Whale --- Western Alaska, July 2002". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 52 (2): 24–26. PMID 12608715.

- More than 200 pilot whales euthanised after stranding on Chatham Islands

- Dwyer, Colin (11 February 2017). "As 200 More Whales Are Stranded In New Zealand, Heroics Turn To Heartbreak". NPR.

- Davey, Melissa (12 February 2017). "Hope for end to New Zealand whale strandings after 350 die" – via The Guardian.

- "New Zealand whales: Hundreds refloat on high tide at Farewell Spit". BBC News. 12 February 2017.

- Stranding of whales at the Falkland Islands

- Hope saved pilot whales in Tasmania can reunite at sea

- Update on the tragic pilot whale stranding in Tasmania

- Stranded Whales Driven Back Into Sea

- "Beach at Stanley Strewn With Whales". The Examiner (Tasmania). Vol. XCIV, no. 184. 15 October 1935. p. 7 (DAILY). Retrieved 23 September 2020 – via National Library of Australia.

- "300 Whales Stranded". The Mercury. Vol. CXLIII, no. 20, 272. 15 October 1935. p. 7. Retrieved 23 September 2020 – via National Library of Australia.

- "The Whales at Stanley will be buried". The Examiner (Tasmania). Vol. XCIV, no. 187. 16 October 1935. p. 7 (DAILY). Retrieved 23 September 2020 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Burying Whales". The Mercury. Vol. CXLIII, no. 20, 277. 21 October 1935. p. 11. Retrieved 23 September 2020 – via National Library of Australia.

- A Whale of a Query

- Theory on dead whales

- "Nearly 500 pilot whales die in New Zealand beachings". BNO News. October 10, 2022. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- Desperate rescue mission to save stranded Tasmanian pod ends with 35 successfully returned to the ocean

- "Apocalypse video: more than 300 whales found dead in Patagonia! Politicians must take Now strict measures to protect more our Oceans!". Arctic05. Retrieved 2021-10-11.

- Howard, Brian Clark; National Geographic (20 November 2015). "337 Whales Beached in Largest Stranding Ever". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2015-11-21.

- "More than 140 whales die after mass stranding on remote New Zealand beach". ABC News (Australia). 26 November 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- "Dozens of pilot whales found dead after mass stranding on remote Iceland beach". ABC News. 20 July 2019.

- "Largest whale stranding in Sri Lanka draws epic volunteer rescue effort". News First. 3 November 2020. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- Karunatilake, Waruna (3 November 2020). "Sri Lankan navy, villagers rescue more than 100 stranded whales". Reuters. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- Whitty, Julia (2007). The Fragile Edge: Diving and other adventures in the South Pacific. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ASIN B002V1GZN2.

External links

- Protect Marine Mammals from Ocean Noise (Natural Resources Defense Council)