Sei whale

The sei whale (/seɪ/ SAY,[4] Norwegian: [sæɪ]; Balaenoptera borealis) is a baleen whale, the third-largest rorqual after the blue whale and the fin whale.[5] It inhabits most oceans and adjoining seas, and prefers deep offshore waters.[6] It avoids polar and tropical waters and semi-enclosed bodies of water. The sei whale migrates annually from cool, subpolar waters in summer to temperate, subtropical waters in winter with a lifespan of 70 years.[7]

| Sei whale[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sei whale mother and calf | |

| |

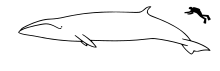

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Balaenopteridae |

| Genus: | Balaenoptera |

| Species: | B. borealis |

| Binomial name | |

| Balaenoptera borealis Lesson, 1828 | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

| Sei whale range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Reaching 19.5 m (64 ft) in length and weighing as much as 28 t (28 long tons; 31 short tons),[7] the sei whale consumes an average of 900 kg (2,000 lb) of food every day; its diet consists primarily of copepods, krill, and other zooplankton.[8] It is among the fastest of all cetaceans, and can reach speeds of up to 50 km/h (31 mph) (27 knots) over short distances.[8] The whale's name comes from the Norwegian word for pollock, a fish that appears off the coast of Norway at the same time of the year as the sei whale.[9]

Following large-scale commercial whaling during the late 19th and 20th centuries, when over 255,000 whales were killed,[10][11] the sei whale is now internationally protected.[2] As of 2008, its worldwide population was about 80,000, less than a third of its prewhaling population.[12][13]

Etymology

Sei is the Norwegian word for pollock, also referred to as coalfish, a close relative of codfish. Sei whales appeared off the coast of Norway at the same time as the pollock, both coming to feed on the abundant plankton.[9] The specific name is the Latin word borealis, meaning northern. In the Pacific, the whale has been called the Japan finner; "finner" was a common term used to refer to rorquals. In Japanese, the whale was called iwashi kujira, or sardine whale, a name originally applied to Bryde's whales by early Japanese whalers. Later, as modern whaling shifted to Sanriku—where both species occur—it was confused for the sei whale. Now the term only applies to the latter species.[14][15] It has also been referred to as the lesser fin whale because it somewhat resembles the fin whale.[16] The American naturalist Roy Chapman Andrews compared the sei whale to the cheetah, because it can swim at great speeds "for a few hundred yards", but it "soon tires if the chase is long" and "does not have the strength and staying power of its larger relatives".[17]

Taxonomy

On 21 February 1819, a 32-ft whale stranded near Grömitz, in Schleswig-Holstein. The Swedish-born German naturalist Karl Rudolphi initially identified it as Balaena rostrata (=Balaenoptera acutorostrata). In 1823, the French naturalist Georges Cuvier described and figured Rudolphi's specimen under the name "rorqual du Nord". In 1828, Rene Lesson translated this term into Balaenoptera borealis, basing his designation partly on Cuvier's description of Rudolphi's specimen and partly on a 54-ft female that had stranded on the coast of France the previous year (this was later identified as a juvenile fin whale, Balaenoptera physalus). In 1846, the English zoologist John Edward Gray, ignoring Lesson's designation, named Rudolphi's specimen Balaenoptera laticeps, which others followed.[18] In 1865, the British zoologist William Henry Flower named a 45-ft specimen that had been obtained from Pekalongan, on the north coast of Java, Sibbaldius (=Balaenoptera) schlegelii—in 1946 the Russian scientist A.G. Tomilin synonymized S. schlegelii and B. borealis, creating the subspecies B. b. schlegelii and B. b. borealis.[19][20] In 1884–85, the Norwegian scientist G. A. Guldberg first identified the "sejhval" of Finnmark with B. borealis.[21]

Sei whales are rorquals (family Balaenopteridae), baleen whales that include the humpback whale, the blue whale, Bryde's whale, the fin whale, and the minke whale. Rorquals take their name from the Norwegian word røyrkval, meaning "furrow whale",[22] because family members have a series of longitudinal pleats or grooves on the anterior half of their ventral surface. Balaenopterids diverged from the other families of suborder Mysticeti, also called the whalebone whales, as long ago as the middle Miocene.[23] Little is known about when members of the various families in the Mysticeti, including the Balaenopteridae, diverged from each other.

Two subspecies have been identified—the northern sei whale (B. b. borealis) and southern sei whale (B. b. schlegelii).[24]

Description

The sei whale is the third-largest balaenopterid, after the blue whale (up to 180 tonnes, 200 tons) and the fin whale (up to 70 tonnes, 77 tons) but close to the humpback whale.[5] In the North Pacific, adult males average 13.7 m (45 ft) and adult females average 15 m (49 ft), weighing 15 and 18.5 tonnes (16.5 and 20.5 tons),[25] while in the North Atlantic adult males average 14 m (46 ft) and adult females 14.5 m (48 ft), weighing 15.5 and 17 tonnes (17 and 18.5 tons)[25] In the Southern Hemisphere, they average 14.5 (47.5 ft) and 15 m (49 ft), respectively, weighing 17 and 18.5 tonnes (18.5 and 20.5 tons).[25] ([26] In the Northern Hemisphere, males reach up to 17.1 m (56 ft) and females up to 18.6 m (61 ft),[27] while in the Southern Hemisphere males reach 18.6 m (61 ft) and females 19.5 m (64 ft)—the authenticity of an alleged 22 m (72 ft) female caught 50 miles northwest of St. Kilda in July 1911 is doubted.[28][29][30] The largest specimens taken off Iceland were a 16.15 m (53.0 ft) female and a 14.6 m (48 ft) male, while the longest off Nova Scotia were two 15.8 m (52 ft) females and a 15.2 m (50 ft) male.[30][31] The longest measured during JARPN II cruises in the North Pacific were a 16.32 m (53.5 ft) female and a 15 m (49 ft) male.[32][33] The longest measured by Discovery Committee staff were an adult male of 16.15 m (53.0 ft) and an adult female of 17.1 m (56 ft), both caught off South Georgia.[34] Adults usually weigh between 15 and 20 metric tons—a 16.4 m (54 ft) pregnant female caught off Natal in 1966 weighed 37.75 tonnes (41.6 tons), not including 6% for loss of fluids during flensing.[25] Females are considerably larger than males.[7] At birth, a calf typically measures 4.4–4.5 m (14–15 ft) in length.

Anatomy

The whale's body is typically a dark steel grey with irregular light grey to white markings on the ventral surface, or towards the front of the lower body. The whale has a relatively short series of 32–60 pleats or grooves along its ventral surface that extend halfway between the pectoral fins and umbilicus (in other species it usually extends to or past the umbilicus), restricting the expansion of the buccal cavity during feeding compared to other species.[35] The rostrum is pointed and the pectoral fins are relatively short, only 9%–10% of body length, and pointed at the tips.[9] It has a single ridge extending from the tip of the rostrum to the paired blowholes that are a distinctive characteristic of baleen whales.

The whale's skin is often marked by pits or wounds, which after healing become white scars. These are now known to be caused by "cookie-cutter" sharks (Isistius brasiliensis).[36] It has a tall, sickle-shaped dorsal fin that ranges in height from 38–90 cm (15–35 in) and averages 53–56 cm (21–22 in), about two-thirds of the way back from the tip of the rostrum.[37] Dorsal fin shape, pigmentation pattern, and scarring have been used to a limited extent in photo-identification studies.[38] The tail is thick and the fluke, or lobe, is relatively small in relation to the size of the whale's body.[9]

Adults have 300–380 ashy-black baleen plates on each side of the mouth, up to 80 cm (31 in) long. Each plate is made of fingernail-like keratin, which is bordered by a fringe of very fine, short, curly, wool-like white bristles.[8] The sei's very fine baleen bristles, about 0.1 mm (0.004 in) are the most reliable characteristic that distinguishes it from other rorquals.[39]

The sei whale looks very similar to other large rorquals, especially its smaller relative the Bryde's whale. The best way to distinguish between it and Bryde's whale, apart from differences in baleen plates, is by the presence of lateral ridges on the dorsal surface of the Bryde's whale's rostrum. Large individuals can be confused with fin whales, unless the fin whale's asymmetrical head coloration is clearly seen. The fin whale's lower jaw's right side is white, and the left side is grey. When viewed from the side, the rostrum appears slightly arched (accentuated at the tip), while fin and Bryde's whales have relatively flat rostrums.[7]

Life history

Surface behaviors

Sei whales usually travel alone[40] or in pods of up to six individuals.[38] Larger groups may assemble at particularly abundant feeding grounds. Very little is known about their social structure. During the southern Gulf of Maine influx in mid-1986, groups of at least three sei whales were observed "milling" on four occasions – i.e. moving in random directions, rolling, and remaining at the surface for over 10 minutes. One whale would always leave the group during or immediately after such socializing bouts.[38] The sei whale is among the fastest cetaceans. It can reach speeds of up to 50 km/h (27 kn) over short distances.[8] However, it is not a remarkable diver, reaching relatively shallow depths for 5 to 15 minutes. Between dives, the whale surfaces for a few minutes, remaining visible in clear, calm waters, with blows occurring at intervals of about 60 seconds (range: 45–90 sec.). Unlike the fin whale, the sei whale tends not to rise high out of the water as it dives, usually just sinking below the surface. The blowholes and dorsal fin are often exposed above the water surface almost simultaneously. The whale almost never lifts its flukes above the surface, and are generally less active on water surfaces than closely related Bryde's whales; it rarely breaches.[7]

Feeding

This rorqual is a filter feeder, using its baleen plates to obtain its food by opening its mouth, engulfing or skimming large amounts of the water containing the food, then straining the water out through the baleen, trapping any food items inside its mouth.

The sei whale feeds near the surface of the ocean, swimming on its side through swarms of prey to obtain its average of about 900 kg (2,000 lb) of food each day.[8] For an animal of its size, for the most part, its preferred foods lie unusually relatively low in the food chain, including zooplankton and small fish. The whale's diet preferences has been determined from stomach analyses, direct observation of feeding behavior,[41][42] and analyzing fecal matter collected near them, which appears as a dilute brown cloud. The feces are collected in nets and DNA is separated, individually identified, and matched with known species.[43] The whale competes for food against clupeid fish (herring and its relatives), basking sharks, and right whales.

In the North Atlantic, it feeds primarily on calanoid copepods, specifically Calanus finmarchicus, with a secondary preference for euphausiids, in particular Meganyctiphanes norvegica and Thysanoessa inermis.[44][45] In the North Pacific, it feeds on similar zooplankton, including the copepod species Neocalanus cristatus, N. plumchrus, and Calanus pacificus, and euphausiid species Euphausia pacifica, E. similis, Thysanoessa inermis, T. longipes, T. gregaria and T. spinifera. In addition, it eats larger organisms, such as the Japanese flying squid, Todarodes pacificus pacificus,[46] and small fish, including anchovies (Engraulis japonicus and E. mordax), sardines (Sardinops sagax), Pacific saury (Cololabis saira), mackerel (Scomber japonicus and S. australasicus), jack mackerel (Trachurus symmetricus) and juvenile rockfish (Sebastes jordani).[44][47] Some of these fish are commercially important. Off central California, they mainly feed on anchovies between June and August, and on krill (Euphausia pacifica) during September and October.[48] In the Southern Hemisphere, prey species include the copepods Neocalanus tonsus, Calanus simillimus, and Drepanopus pectinatus, as well as the euphausiids Euphausia superba and Euphausia vallentini[44] and the pelagic amphipod Themisto gaudichaudii.

Parasites and epibiotics

Ectoparasites and epibiotics are rare on sei whales. Species of the parasitic copepod Pennella were only found on 8% of sei whales caught off California and 4% of those taken off South Georgia and South Africa. The pseudo-stalked barnacle Xenobalanus globicipitis was found on 9% of individuals caught off California; it was also found on a sei whale taken off South Africa. The acorn barnacle Coronula reginae and the stalked barnacle Conchoderma virgatum were each only found on 0.4% of whales caught off California. Remora australis were rarely found on sei whales off California (only 0.8%). They often bear scars from the bites of cookiecutter sharks, with 100% of individuals sampled off California, South Africa, and South Georgia having them; these scars have also been found on sei whales captured off Finnmark. Diatom (Cocconeis ceticola) films on sei whales are rare, having been found on sei whales taken off California and South Georgia.[37][48][49]

Due to their diverse diet, endoparasites are frequent and abundant in sei whales. The harpacticoid copepod Balaenophilus unisetus infests the baleen of sei whales caught off California, South Georgia, South Africa, and Finnmark. The ciliate protozoan Haematophagus was commonly found in the baleen of sei whales taken off South Georgia (nearly 85%). They often carry heavy infestations of acanthocephalans (e.g. Bolbosoma turbinella, which was found in 40% of sei whales sampled off California; it was also found in individuals off South Georgia and Finnmark) and cestodes (e.g. Tetrabothrius affinis, found in sei whales off California and South Georgia) in the intestine, nematodes in the kidneys (Crassicauda sp., California) and stomach (Anisakis simplex, nearly 60% of whales taken off California), and flukes (Lecithodesmus spinosus, found in 38% of individuals caught off California) in the liver.[37][48][49]

Reproduction

Mating occurs in temperate, subtropical seas during the winter. Gestation is estimated to vary around 103⁄4 months,[50] 111⁄4 months,[51] or one year,[52] depending which model of foetal growth is used. The different estimates result from scientists' inability to observe an entire pregnancy; most reproductive data for baleen whales were obtained from animals caught by commercial whalers, which offer only single snapshots of fetal growth. Researchers attempt to extrapolate conception dates by comparing fetus size and characteristics with newborns.

A newborn is weaned from its mother at 6–9 months of age, when it is 8–9 m (26–30 ft) long,[27] so weaning takes place at the summer or autumn feeding grounds. Females reproduce every 2–3 years,[50] usually to a single calf.[8] In the Northern Hemisphere, males are usually 12.8–12.9 m (42–42 ft) and females 13.3–13.5 m (44–44 ft) at sexual maturity, while in the Southern Hemisphere, males average 13.6 m (45 ft) and females 14 m (46 ft).[26] The average age of sexual maturity of both sexes is 8–10 years.[50] The whales can reach ages up to 65 years.[53]

Vocalizations

The sei whale makes long, loud, low-frequency sounds. Relatively little is known about specific calls, but in 2003, observers noted sei whale calls in addition to sounds that could be described as "growls" or "whooshes" off the coast of the Antarctic Peninsula.[54] Many calls consisted of multiple parts at different frequencies. This combination distinguishes their calls from those of other whales. Most calls lasted about a half second, and occurred in the 240–625 hertz range, well within the range of human hearing. The maximum volume of the vocal sequences is reported as 156 decibels relative to 1 micropascal (μPa) at a reference distance of one metre.[54] An observer situated one metre from a vocalizing whale would perceive a volume roughly equivalent to the volume of a jackhammer operating two metres away.[55]

In November 2002, scientists recorded calls in the presence of sei whales off Maui. All the calls were downswept tonal calls, all but two ranging from a mean high frequency of 39.1 Hz down to 21 Hz of 1.3 second duration – the two higher frequency downswept calls ranged from an average of 100.3 Hz to 44.6 Hz over 1 second of duration. These calls closely resembled and coincided with a peak in "20- to 35-Hz irregular repetition interval" downswept pulses described from seafloor recordings off Oahu, which had previously been attributed to fin whales.[56] Between 2005 and 2007, low frequency downswept vocalizations were recorded in the Great South Channel, east of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, which were only significantly associated with the presence of sei whales. These calls averaged 82.3 Hz down to 34 Hz over about 1.4 seconds in duration. This call has also been reported from recordings in the Gulf of Maine, New England shelf waters, the mid-Atlantic Bight, and in Davis Strait. It likely functions as a contact call.[57]

BBC News quoted Roddy Morrison, a former whaler active in South Georgia, as saying, "When we killed the sei whales, they used to make a noise, like a crying noise. They seemed so friendly, and they'd come round and they'd make a noise, and when you hit them, they cried really. I didn't think it was really nice to do that. Everybody talked about it at the time I suppose, but it was money. At the end of the day that's what counted at the time. That's what we were there for."[58]

Range and migration

.jpg.webp)

Sei whales live in all oceans, although rarely in polar or tropical waters.[7] The difficulty of distinguishing them at sea from their close relatives, Bryde's whales and in some cases from fin whales, creates confusion about their range and population, especially in warmer waters where Bryde's whales are most common.

In the North Atlantic, its range extends from southern Europe or northwestern Africa to Norway, and from the southern United States to Greenland.[6] The southernmost confirmed records are strandings along the northern Gulf of Mexico and in the Greater Antilles.[39] Throughout its range, the whale tends not to frequent semienclosed bodies of water, such as the Gulf of Mexico, the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, Hudson Bay, the North Sea, and the Mediterranean Sea.[7] It occurs predominantly in deep water, occurring most commonly over the continental slope,[59] in basins situated between banks,[60] or submarine canyon areas.[61]

In the North Pacific, it ranges from 20°N to 23°N latitude in the winter, and from 35°N to 50°N latitude in the summer.[62] Approximately 75% of the North Pacific population lives east of the International Date Line,[10] but there is little information regarding the North Pacific distribution. As of February 2017, the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service estimated that the eastern North Pacific population stood at 374 whales.[63] Two whales tagged in deep waters off California were later recaptured off Washington and British Columbia, revealing a possible link between these areas,[64] but the lack of other tag recovery data makes these two cases inconclusive. Occurrences within the Gulf of California have been fewer.[65] In Sea of Japan and Sea of Okhotsk, whales are not common, although whales were more commonly seen than today in southern part of Sea of Japan from Korean Peninsula to the southern Primorsky Krai in the past, and there had been a sighting in Golden Horn Bay,[66] and whales were much more abundant in the triangle area around Kunashir Island in whaling days, making the area well known as sei – ground,[67] and there had been a sighting of a cow calf pair off the Sea of Japan coast of mid-Honshu during cetacean survey.

Sei whales have been recorded from northern Indian Ocean as well such as around Sri Lanka and Indian coasts.[68]

In the Southern Hemisphere, summer distribution based upon historic catch data is between 40°S and 50°S latitude in the South Atlantic and southern Indian Oceans and 45°S and 60°S in the South Pacific, while winter distribution is poorly known, with former winter whaling grounds being located off northeastern Brazil (7°S) and Peru (6°S).[2] The majority of the "sei" whales caught off Angola and Congo, as well as other nearby areas in equatorial West Africa, are thought to have been predominantly misidentified Bryde's whales. For example, Ruud (1952) found that 42 of the "sei whale" catch off Gabon in 1952 were actually Bryde's whales, based on examination of their baleen plates. The only confirmed historical record is the capture of a 14 m (46 ft) female, which was brought to the Cap Lopez whaling station in Gabon in September 1950. During cetacean sighting surveys off Angola between 2003 and 2006, only a single confirmed sighting of two individuals was made in August 2004, compared to 19 sightings of Bryde's whales.[69] Sei whales are commonly distributed along west to southern Latin America including along entire Chilean coasts, within Beagle Channel[70] and possibly feed in the Aysen region.[71] The Falkland Islands appears to be a regionally important area for the Sei Whale, as a small population exists in coastal waters off the eastern Falkland archipelago. For reasons unknown, the whales prefer to stay inland here, even venturing into large bays. This provides scientists with a rare opportunity to study this normally pelagic species without having to travel far out into the ocean.

Migration

In general, the sei whale migrates annually from cool and subpolar waters in summer to temperate and subtropical waters for winter, where food is more abundant.[7] In the northwest Atlantic, sightings and catch records suggest the whales move north along the shelf edge to arrive in the areas of Georges Bank, Northeast Channel, and Browns Bank by mid- to late June. They are present off the south coast of Newfoundland in August and September, and a southbound migration begins moving west and south along the Nova Scotian shelf from mid-September to mid-November. Whales in the Labrador Sea as early as the first week of June may move farther northward to waters southwest of Greenland later in the summer.[72] In the northeast Atlantic, the sei whale winters as far south as West Africa such as off Bay of Arguin, off coastal Western Sahara and follows the continental slope northward in spring. Large females lead the northward migration and reach the Denmark Strait earlier and more reliably than other sexes and classes, arriving in mid-July and remaining through mid-September. In some years, males and younger females remain at lower latitudes during the summer.[30]

Despite knowing some general migration patterns, exact routes are incompletely known[30] and scientists cannot readily predict exactly where groups will appear from one year to the next.[73] F.O. Kapel noted a correlation between appearances west of Greenland and the incursion of relatively warm waters from the Irminger Current into that area.[74] Some evidence from tagging data indicates individuals return off the coast of Iceland on an annual basis.[75] An individual satellite-tagged off Faial, in the Azores, traveled more than 4,000 km (2,500 mi) to the Labrador Sea via the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone (CGFZ) between April and June 2005. It appeared to "hitch a ride" on prevailing currents, with erratic movements indicative of feeding behavior in five areas, in particular the CGFZ, an area of known high sei whale abundance as well as high copepod concentrations.[76] Seven whales tagged off Faial and Pico from May to June in 2008 and 2009 made their way to the Labrador Sea, while an eighth individual tagged in September 2009 headed southeast – its signal was lost between Madeira and the Canary Islands.[77]

Whaling

The development of explosive harpoons and steam-powered whaling ships in the late nineteenth century brought previously unobtainable large whales within reach of commercial whalers. Initially their speed and elusiveness,[78] and later the comparatively small yield of oil and meat partially protected them. Once stocks of more profitable right whales, blue whales, fin whales, and humpback whales became depleted, sei whales were hunted in earnest, particularly from 1950 to 1980.[5]

North Atlantic

_(20165115029).jpg.webp)

In the North Atlantic between 1885 and 1984, 14,295 sei whales were taken.[10] They were hunted in large numbers off the coasts of Norway and Scotland beginning in the late 19th and early 20th centuries,[73] and in 1885 alone, more than 700 were caught off Finnmark.[79] Their meat was a popular Norwegian food. The meat's value made the hunting of this difficult-to-catch species profitable in the early twentieth century.[80]

In Iceland, a total of 2,574 whales were taken from the Hvalfjörður whaling station between 1948 and 1985. Since the late 1960s to early 1970s, the sei whale has been second only to the fin whale as the preferred target of Icelandic whalers, with meat in greater demand than whale oil, the prior target.[78]

Small numbers were taken off the Iberian Peninsula, beginning in the 1920s by Spanish whalers,[81] off the Nova Scotian shelf in the late 1960s and early 1970s by Canadian whalers,[72] and off the coast of West Greenland from the 1920s to the 1950s by Norwegian and Danish whalers.[74]

North Pacific

)_(17974297289).jpg.webp)

In the North Pacific, the total reported catch by commercial whalers was 72,215 between 1910 and 1975;[10] the majority were taken after 1947.[82] Shore stations in Japan and Korea processed 300–600 each year between 1911 and 1955. In 1959, the Japanese catch peaked at 1,340. Heavy exploitation in the North Pacific began in the early 1960s, with catches averaging 3,643 per year from 1963 to 1974 (total 43,719; annual range 1,280–6,053).[83] In 1971, after a decade of high catches, it became scarce in Japanese waters, ending commercial whaling in 1975.[44][84]

Off the coast of North America, sei whales were hunted off British Columbia from the late 1950s to the mid-1960s, when the number of whales captured dropped to around 14 per year.[5] More than 2,000 were caught in British Columbian waters between 1962 and 1967.[85] Between 1957 and 1971, California shore stations processed 386 whales.[48] Commercial Sei whaling ended in the eastern North Pacific in 1971.

Southern Hemisphere

A total of 152,233 were taken in the Southern Hemisphere between 1910 and 1979.[10] Whaling in southern oceans originally targeted humpback whales. By 1913, this species became rare, and the catch of fin and blue whales began to increase. As these species likewise became scarce, sei whale catches increased rapidly in the late 1950s and early 1960s.[44] The catch peaked in 1964–65 at over 20,000 sei whales, but by 1976, this number had dropped to below 2,000 and commercial whaling for the species ended in 1977.[5]

Post-protection whaling

Since the moratorium on commercial whaling, some sei whales have been taken by Icelandic and Japanese whalers under the IWC's scientific research programme. Iceland carried out four years of scientific whaling between 1986 and 1989, killing up to 40 sei whales a year.[86][87] The research is conducted by the Institute of Cetacean Research (ICR) in Tokyo, a privately funded, nonprofit institution. The main focus of the research is to examine what they eat and to assess the competition between whales and fisheries. Dr. Seiji Ohsumi, Director General of the ICR, said,

- "It is estimated that whales consume 3 to 5 times the amount of marine resources as are caught for human consumption, so our whale research is providing valuable information required for improving the management of all our marine resources."[88]

He later added,

- "Sei whales are the second-most abundant species of whale in the western North Pacific, with an estimated population of over 28,000 animals. [It is] clearly not endangered."[89]

Conservation groups, such as the World Wildlife Fund, dispute the value of this research, claiming that sei whales feed primarily on squid and plankton which are not hunted by humans, and only rarely on fish. They say that the program is

- "nothing more than a plan designed to keep the whaling fleet in business, and the need to use whales as the scapegoat for overfishing by humans."[90]

At the 2001 meeting of the IWC Scientific Committee, 32 scientists submitted a document expressing their belief that the Japanese program lacked scientific rigor and would not meet minimum standards of academic review.[91]

In 2010, a Los Angeles restaurant confirmed to be serving sei whale meat was closed by its owners after prosecution by authorities for handling a protected species. [92]

Conservation status

The sei whale did not have meaningful international protection until 1970, when the International Whaling Commission first set catch quotas for the North Pacific for individual species. Before quotas, there were no legal limits.[93] Complete protection from commercial whaling in the North Pacific came in 1976.

Quotas on sei whales in the North Atlantic began in 1977. Southern Hemisphere stocks were protected in 1979. Facing mounting evidence that several whale species were threatened with extinction, the IWC established a complete moratorium on commercial whaling beginning in 1986.[7]

In the late 1970s, some "pirate" whaling took place in the eastern North Atlantic.[94] There is no direct evidence of illegal whaling in the North Pacific, although the acknowledged misreporting of whaling data by the Soviet Union[95] means that catch data are not entirely reliable.

The species remained listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in 2000, categorized as "endangered".[2] Northern Hemisphere populations are listed as CITES Appendix II, indicating they are not immediately threatened with extinction, but may become so if they are not listed. Populations in the Southern Hemisphere are listed as CITES Appendix I, indicating they are threatened with extinction if trade is not halted.[8]

The sei whale is listed on both Appendix I[96] and Appendix II[96] of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). It is listed on Appendix I[96] as this species has been categorized as being in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant proportion of their range and CMS parties strive towards strictly protecting these animals, conserving or restoring the places where they live, mitigating obstacles to migration and controlling other factors that might endanger them and also on Appendix II[96] as it has an unfavourable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organised by tailored agreements.

Sei whale is covered by the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region (Pacific Cetaceans MOU) and the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas (ASCOBAMS).[97]

The species is listed as endangered by the U.S. government National Marine Fisheries Service under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.[5]

Population estimates

The current population is estimated at 80,000, nearly a third of the prewhaling population.[9][12] A 1991 study in the North Atlantic estimated only 4,000.[98][99] Sei whales were said to have been scarce in the 1960s and early 1970s off northern Norway.[100] One possible explanation for this disappearance is that the whales were overexploited.[100] The drastic reduction in northeastern Atlantic copepod stocks during the late 1960s may be another culprit.[101] Surveys in the Denmark Strait found 1,290 whales in 1987, and 1,590 whales in 1989.[101] Nova Scotia's population estimates are between 1,393 and 2,248, with a minimum of 870.[72]

A 1977 study estimated Pacific Ocean totals of 9,110, based upon catch and CPUE data.[83] Japanese interests claim this figure is outdated, and in 2002 claimed the western North Pacific population was over 28,000,[89] a figure not accepted by the scientific community.[90] In western Canadian waters, researchers with Fisheries and Oceans Canada observed five Seis together in the summer of 2017, the first such sighting in over 50 years.[102] In California waters, there was only one confirmed and five possible sightings by 1991 to 1993 aerial and ship surveys,[103][104][105] and there were no confirmed sightings off Oregon coasts such as Maumee Bay and Washington. Prior to commercial whaling, the North Pacific hosted an estimated 42,000.[83] By the end of whaling, the population was down to between 7,260 and 12,620.[83]

In the Southern Hemisphere, population estimates range between 9,800 and 12,000, based upon catch history and CPUE.[98] The IWC estimated 9,718 whales based upon survey data between 1978 and 1988.[106] Prior to commercial whaling, there were an estimated 65,000.[98]

Mass deaths

Mass death events for sei whales have been recorded for many years and evidence suggests endemic poisoning (red tide) causes may have caused mass deaths in prehistoric times. In June 2015, scientists flying over southern Chile counted 337 dead sei whales, in what is regarded as the largest mass beaching ever documented.[107] The cause is not yet known; however, toxic algae blooms caused by unprecedented warming in the Pacific Ocean, known as the Blob, may be implicated.[108]

See also

- List of cetaceans

- Marine biology

- Pacific Islands Cetaceans Memorandum of Understanding

- HMS Daedalus (1826)

References

- Mead, J. G.; Brownell, R. L. Jr. (2005). "Order Cetacea". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 723–743. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Cooke, J.G. 2018. Balaenoptera borealis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T2475A130482064. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T2475A130482064.en. Downloaded on 04 May 2021.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- "sei whale". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- S.L. Perry; D.P. DeMaster; G.K. Silber (1999). "Special Issue: The Great Whales: History and Status of Six Species Listed as Endangered Under the U.S. Endangered Species Act of 1973". Marine Fisheries Review. 61 (1): 52–58. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- Gambell, R. (1985). "Sei Whale Balaenoptera borealis Lesson, 1828". In S.H. Ridgway; R. Harrison (eds.). Handbook of Marine Mammals, Vol. 3. London: Academic Press. pp. 155–170.

- Reeves, R.; G. Silber; M. Payne (July 1998). Draft Recovery Plan for the Fin Whale Balaenoptera physalus and Sei Whale Balaenoptera borealis (PDF). Silver Spring, Maryland: National Marine Fisheries Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2006.

- Shefferly, N. (1999). "Balaenoptera borealis". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 4 November 2006.

- "Sei Whale & Bryde's Whale Balaenoptera borealis & Balaenoptera edeni". American Cetacean Society. March 2004. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006. Retrieved 8 November 2006.

- Horwood, J. (1987). The sei whale: population biology, ecology, and management. Kent, England: Croom Helm Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7099-4786-8.

- Berzin, A. 2008. The Truth About Soviet Whaling (Marine Fisheries Review), pp. 57–8.

- Thomas A. Jefferson; Marc A. Webber & Robert L. Pitman (2008). Marine Mammals of the World: A Comprehensive Guide to their Identification. London: Academic. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- "Sei whale". National Marine Fisheries Service. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- Omura, Hidero. "Review of the Occurrence of the Bryde's Whale in the Northwest Pacific". Rep. Int. Commn. (Special Issue 1), 1977, pp. 88–91.

- Andrews, R.C. (May 1911). "Shore Whaling: A World Industry". National Geographic Magazine. Archived from the original on 4 October 2006.

- Glover Morrill Allen (1916). Whalebone Whales of New England. Vol. 8. p. 234. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- Andrews, Roy Chapman. 1916. Whale hunting with gun and camera; a naturalist's account of the modern shore-whaling industry, of whales and their habits, and of hunting experiences in various parts of the world. New York: D. Appleton and Co., p. 128.

- Gray, J. E. 1846. On the cetaceous animals. pp. 1–53 in The zoology of the voyage of H.M.S. Erebus and Terror. Vol. 1. Mammalia, birds (J. Richardson and J. E. Gray, eds.). E. W. Jansen, London.

- Flower, W. H. (1865). "Notes on the skeletons of whales in the principal museums of Holland and Belgium, with descriptions of two species apparently new to science". Proceedings of the Zoological Society. 1864 (25): 384–420.

- Perrin, William F., James G. Mead, and Robert L. Brownell, Jr. "Review of the evidence used in the description of currently recognized cetacean subspecies". NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS (December 2009), pp. 1–35.

- Guldberg, G.A. (1885). "On the existence of a fourth species of the genus Balaenoptera". J. Anat. Physiol. 19: 293–302.

- "Etymology of mammal names". IberiaNature – Natural history facts and trivia. Retrieved 7 December 2006.

- Gingerich, P. (2004). "Whale Evolution" (PDF). McGraw-Hill Yearbook of Science & Technology. The McGraw Hill Companies.

- "Balaenoptera borealis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 10 November 2006.

- Lockyer, C. (February 1976). "Body weights of some species of large whales". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 36 (3): 259–273. doi:10.1093/icesjms/36.3.259.

- Evans, Peter G. H. (1987). The Natural History of Whales and Dolphins. Facts on File.

- Klinowska, M. (1991). Dolphins, Porpoises and Whales of the World: The IUCN Red Data Book. Cambridge, U.K.: IUCN.

- Skinner, J.D. and Christian T. Chimimba. (2006). The Mammals of the Southern African Sub-region. Cambridge University Press, Third Edition.

- Thompson, D'Arcy Wentworth. "On whales landed at the Scottish whaling stations, especially during the years 1908–1914—Part VII. The sei-whale". The Scottish Naturalist, nos. 85-96 (1919), pp. 37–46.

- Martin, A.R. (1983). "The sei whale off western Iceland. I. Size, distribution and abundance". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 33: 457–463.

- Mitchell, E.D. (1975). "Preliminary report on Nova Scotia fishery for sei whales (Balaenoptera borealis)"". Reports of the International Whaling Commission. 25: 218–225.

- Tamura; et al. (2005). "Cruise report of the second phase of the Japanese Research Program under Special Permit in the Western North Pacific (JAPRN II) in 2005 – Offshore component". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 58: 1–52.

- Tamura; et al. (2006). "Cruise report of the second phase of the Japanese Research Program under Special Permit in the Western North Pacific (JAPRN II) in 2006 (part I) – Offshore component". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 59: 1–26.

- Mackintosh, N. A. (1943). "The southern stocks of whalebone whales". Discovery Reports. XXII (3889): 199–300. Bibcode:1944Natur.153..569F. doi:10.1038/153569a0. S2CID 41590649.

- Brodie, P.; Víkingsson, G. (2009). "On the feeding mechanism of the sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis)"". Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science. 42: 49–54. doi:10.2960/j.v42.m646.

- Shevchenko, V.I. (1977). "Application of white scars to the study of the location and migrations of sei whale populations in Area III of the Antarctic". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. Spec. Iss. 1: 130–134.

- Matthews, L.H. (1938). "The sei whale Balaenoptera borealis"". Discovery Reports. 17: 183–290.

- Schilling, M.R.; I. Seipt; M.T. Weinrich; S.E. Frohock; A.E. Kuhlberg; P.J. Clapham (1992). "Behavior of individually identified sei whales Balaenoptera borealis during an episodic influx into the southern Gulf of Maine in 1986" (PDF). Fish. Bull. 90: 749–755. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2021.

- Mead, J.G. (1977). "Records of sei and Bryde's whales from the Atlantic coast of the United States, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. Spec. Iss. 1: 113–116.

- Edds, P.L.; T.J. MacIntyre; R. Naveen (1984). "Notes on a sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis Lesson) sighted off Maryland". Cetus. 5 (2): 4–5.

- Watkins, W.A.; W.E. Schevill (1979). "Aerial observations of feeding behavior in four baleen whales: Eubalaena glacialis, Balaenoptera borealis, Megaptera novaeangliae, and Balaenoptera physalus". J. Mammal. 60 (1): 155–163. doi:10.2307/1379766. JSTOR 1379766.

- Weinrich, M.T.; C.R. Belt; M.R. Schilling; M. Marcy (1986). "Behavior of sei whales in the southern Gulf of Maine, summer 1986". Whalewatcher. 20 (4): 4–7.

- Darby, A. (6 February 2002). "New Research Method May Ease Whale Killing". National Geographic News. Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- Mizroch, S.A.; D.W. Rice; J.M. Breiwick (1984). "The Sei Whale, Balaenoptera borealis". Mar Fish. Rev. 46 (4): 25–29.

- Christensen, I.; T. Haug; N. Øien (1992). "A review of feeding and reproduction in large baleen whales (Mysticeti) and sperm whales Physeter macrocephalus in Norwegian and adjacent waters". Fauna Norvegica Series A. 13: 39–48.

- Tamura, T. (October 2001). Competition for food in the Ocean: Man and other apical predators (PDF). Reykjavik Conference on Responsible Fisheries in the Marine Ecosystem, Reykjavik, Iceland, 1–4 October 2001. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- Nemoto, T.; A. Kawamura (1977). "Characteristics of food habits and distribution of baleen whales with special reference to the abundance of North Pacific sei and Bryde's whales". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. Spec. Iss. 1: 80–87.

- Rice, D.W. (1977). "Synopsis of biological data on the sei whale and Bryde's whale in the eastern North Pacific". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. Spec. Iss. 1: 92–97.

- Collect, R. (1886). "On the external characters of Rudolphi's rorqual (Balaenoptera borealis)". Proc. Zool. Soc. London, XVIII: 243-265.

- Lockyer, C.; A.R. Martin (1983). "The sei whale off western Iceland. II. Age, growth and reproduction". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 33: 465–476.

- Lockyer, C. (1977). "Some estimates of growth in the sei whale, Balaenoptera borealis". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. Spec. Iss. 1: 58–62.

- Risting, S (1928). "Whales and whale foetuses". Rapp. Cons. Explor. Mer. 50: 1–122.

- WWF (18 June 2007). "Sei whale – Ecology & Habitat". WWF Global Species Programme. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- McDonald, M.; Hildebrand, J.; Wiggins, S.; Thiele, D.; Glasgow, D.; Moore, S. (December 2005). "Sei whale sounds recorded in the Antarctic". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 118 (6): 3941–3945. Bibcode:2005ASAJ..118.3941M. doi:10.1121/1.2130944. PMID 16419837. S2CID 2094987.

- Direct comparisons of sounds in water to sounds in air can be complicated, see this description Archived 25 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine for more information.

- Rankin, S.; Barlow, J. (2007). "Vocalizations of the sei whale Balaenoptera borealis off the Hawaiian Islands". Bioacoustics. 16 (2): 137–145. doi:10.1080/09524622.2007.9753572. S2CID 85413269.

- Baumgartner, M.F.; Van Parijs, S.M.; Wenzel, F.W.; Tremblay, C.J.; Esch, H.C.; Ward, A.A. (2008). "Low frequency vocalizations attributed to sei whales (Balaenoptera borealis)"". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 124 (2): 1339–1349. Bibcode:2008ASAJ..124.1339B. doi:10.1121/1.2945155. hdl:1912/4618. PMID 18681619.

- "South Georgia: The lost whaling station at the end of the world". BBC News. 9 June 2014.

- CETAP (1982). Final Report of the Cetacean and Turtle Assessment Program, University of Rhode Island, to Bureau of Land Management (Report). U.S. Department of the Interior. Ref. No. AA551-CT8–48.

- Sutcliffe, W.H. Jr.; P.F. Brodie (1977). "Whale distributions in Nova Scotia waters". Fisheries & Marine Service Technical Report No. 722.

- Kenney, R.D.; H.E. Winn (1987). "Cetacean biomass densities near submarine canyons compared to adjacent shelf/slope areas". Cont. Shelf Res. 7 (2): 107–114. Bibcode:1987CSR.....7..107K. doi:10.1016/0278-4343(87)90073-2.

- Masaki, Y. (1976). "Biological studies on the North Pacific sei whale". Bull. Far Seas Fish. Res. Lab. 14: 1–104.

- "SEI WHALE (Balaenoptera borealis borealis): Eastern North Pacific Stock". National Marine Fisheries Service Marine Mammal Stock Assessment Reports. 8 February 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- Rice, D.W. (1974). "Whales and whale research in the North Pacific". In Schervill, W.E. (ed.). The Whale Problem: a status report. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 170–195. ISBN 978-0-674-95075-7.

- Gendron D.. Rosales C. S.. 1996. Recent sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis) sightings in the Gulf of California, Mexico. Aquatic Mammals 1996, 22.2, pp.127-130 (pdf). Retrieved on February 24, 2017

- "Сейвал / Balaenoptera borealis". www.zoosite.com.ua.

- Uni Y.,2006 Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises off Shiretoko. Bulletin of the Shiretoko Museum 27: pp.37-46. Retrieved on 16 December 2015

- Sathasivam K.. 2015. A CATALOGUE OF INDIAN MARINE MAMMAL RECORDS (pdf)

- Weir, C.R. (2010). "A review of cetacean occurrence in West African waters from the Gulf of Guinea to Angola". Mammal Review. 40: 2–39. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2009.00153.x.

- Daniel.Bisson – SEI Whale at Beagle canal, Ushuaia, Argentina Archived 13 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- OceanSounds e.V. - Sei whale

- Mitchell, E.; D.G. Chapman (1977). "Preliminary assessment of stocks of northwest Atlantic sei whales (Balaenoptera borealis)". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. Spec. Iss. 1: 117–120.

- Jonsgård, Å.; K. Darling (1977). "On the biology of the eastern North Atlantic sei whale, Balaenoptera borealis Lesson". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. Spec. Iss. 1: 124–129.

- Kapel, F.O. (1985). "On the occurrence of sei whales (Balenoptera borealis) in West Greenland waters". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 35: 349–352.

- Sigurjónsson, J. (1983). "The cruise of the Ljósfari in the Denmark Strait (June–July 1981) and recent marking and sightings off Iceland". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 33: 667–682.

- Olsen, E.; Budgell, P.; Head, E.; Kleivane, L.; Nøttestad, L.; Prieto, R.; et al. (2009). "First satellite-tracked long-distance movement of a sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis) in the North Atlantic". Aquatic Mammals. 35 (3): 313–318. doi:10.1578/am.35.3.2009.313.

- Prieto, Rui, Monica A. Silva, Martine Berube, Per J. Palsbøll (2012). "Migratory destinations and sex composition of sei whales (Balaenoptera borealis) transiting through the Azores". SC/64/RMP6, pp. 1-7.

- Sigurjónsson, J. (1988). "Operational factors of the Icelandic large whale fishery". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 38: 327–333.

- Andrews, R.C. (1916). "The sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis Lesson)". Mem. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. New Series. 1 (6): 291–388.

- Ingebrigtsen, A. (1929). "Whales caught in the North Atlantic and other seas". Rapports et Procès-verbaux des réunions, Cons. Perm. Int. L'Explor. Mer, Vol. LVI. Copenhagen: Høst & Fils.

- Aguilar, A.; S. Lens (1981). "Preliminary report on Spanish whaling operations". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 31: 639–643.

- Barlow, J.; K. A. Forney; P. S. Hill; R. L. Brownell Jr.; J. V. Carretta; D. P. DeMaster; F. Julian; M. S. Lowry; T. Ragen & R. R. Reeves (1997). "U.S. Pacific marine mammal stock assessments: 1996" (PDF). NOAA Tech. Mem. NMFS-SWFSC-248.

- Tillman, M.F. (1977). "Estimates of population size for the North Pacific sei whale". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. Spec. Iss. 1: 98–106.

- Committee for Whaling Statistics (1942). International whaling statistics. Oslo: Committee for Whaling Statistics.

- Pike, G.C; I.B. MacAskie (1969). "Marine mammals of British Columbia". Fish. Res. Bd. Canada Bull. 171.

- "WWF condemns Iceland's announcement to resume whaling" (Press release). WWF-International. 7 August 2003. Retrieved 10 November 2006.

- Sandra Altherr. "Iceland's Whaling Comeback" (PDF). The Humane Society of the United States. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- "Japan not catching endangered whales" (PDF) (Press release). The Institute of Cetacean Research, Tokyo, Japan. 1 March 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2006. Retrieved 10 November 2006.

- "Japan's senior whale scientist responds to New York Times advertisement" (PDF) (Press release). The Institute of Cetacean Research, Tokyo, Japan. 20 May 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2006. Retrieved 10 November 2006.

- "Japanese Scientific Whaling: Irresponsible Science, Irresponsible Whaling" (Press release). WWF-International. 1 June 2005. Archived from the original on 25 August 2006. Retrieved 10 November 2006.

- Clapham, P.; et al. (2002). "Relevance of JARPN II to management, and a note on scientific standards. Report of the IWC Scientific Committee, Annex Q1". Journal of Cetacean Research and Management. 4 (supplement): 395–396.

- "L.A. eatery charged with serving whale meat closes". Reuters. 20 March 2010.

- Allen, K.R. (1980). Conservation and Management of Whales. Seattle, WA: Univ. of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-95706-7.

- Best, P.B. (1992). "Catches of fin whales in the North Atlantic by the M.V. Sierra (and associated vessels)". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 42: 697–700.

- Yablokov, A.V. (1994). "Validity of whaling data". Nature. 367 (6459): 108. Bibcode:1994Natur.367..108Y. doi:10.1038/367108a0. S2CID 4358731.

- "Appendix I and Appendix II Archived 11 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine" of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). As amended by the Conference of the Parties in 1985, 1988, 1991, 1994, 1997, 1999, 2002, 2005 and 2008. Effective: 5 March 2009.

- ASCOBAMS.org

- Braham, H. (1992). Endangered whales: Status update (Report). Alaska Fisheries Science Center, Seattle, WA.

- Blaylock, R. A.; J. W. Haim; L. J. Hansen; D. L. Palka & G. T. Waring (1995). "U.S. Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico stock assessments". NOAA Tech. Memo NMFS-SEFSC-363. U.S. Dept. of Commerce.

- Jonsgård, Å. (1974). "On whale exploitation in the eastern part of the North Atlantic Ocean". In W. E. Schevill (ed.). The whale problem. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 97–107.

- Cattanach, K.L.; J. Sigurjonsson; S.T. Buckland; Th. Gunnlaugsson (1993). "Sei whale abundance in the North Atlantic, estimated from NASS-87 and NASS-89 data". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 43: 315–321.

- Rabson, Mia (26 September 2018). "Scientists stumble across endangered whale not seen in Canada in years". The Canadian Press. CTV News. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- Hill, P. S. & J. Barlow (1992). "Report of a marine mammal survey of the California coast aboard the research vessel "MacArthur" July 28 – 5 November 1991" (PDF). NOAA Technical Memo NMFS-SWFSC-169. U.S. Dept. Commerce.

- Carretta, J. V. & K. A. Forney (1993). "Report of two aerial surveys for marine mammals in California coastal waters utilizing a NOAA DeHavilland Twin Otter aircraft: March 9 – 7 April 1991, and February 8 – 6 April 1992" (PDF). NOAA Technical Memo NMFS-SWFSC-185. U.S. Dept. Commerce.

- Mangels, K. F. & T. Gerrodette (1994). "Report of cetacean sightings during a marine mammal survey in the eastern Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of California aboard the NOAA ships "MacArthur" and "David Starr Jordan" July 28 – 6 November 1993" (PDF). NOAA Technical Memo NMFS-SWFSC-211. U.S. Dept. Commerce.

- IWC (1996). "Report of the sub-committee on Southern Hemisphere baleen whales, Annex E". Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 46: 117–131.

- Howard, Brian Clark (20 November 2015). "337 Whales Beached in Largest Stranding Ever". National Geographic. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- On the Coast (14 September 2015). "Dead whales in Pacific could be fault of the Blob". CBC. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

Further reading

- National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World, Reeves, Stewart, Clapham and Powell, 2002, ISBN 0-375-41141-0

- Eds. C. Michael Hogan and C.J.Cleveland. Sei whale. Encyclopedia of Earth, National Council for Science and Environment; content partner Encyclopedia of Life

- Whales & Dolphins Guide to the Biology and Behaviour of Cetaceans, Maurizio Wurtz and Nadia Repetto. ISBN 1-84037-043-2

- Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, editors Perrin, Wursig and Thewissen, ISBN 0-12-551340-2

- Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises, Carwardine (1995, reprinted 2000), ISBN 978-0-7513-2781-6

- Oudejans, M. G.; Visser, F. (2010). "First confirmed record of a living sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis (Lesson, 1828)) in Irish coastal waters". Ir. Nat. J. 31: 46–48.

External links

- US National Marine Fisheries Service Sei Whale web page

- ARKive – images and movies of the sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis)

- World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) – species profile for the Sei Whale

- Official website of the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Contiguous Atlantic Area

- Voices in the Sea – Sounds of the Sei Whale