Beji Caid Essebsi

Beji Caid Essebsi (or es-Sebsi; Arabic: الباجي قائد السبسي, romanized: Muhammad al-Bājī Qā’id as-Sibsī, ![]() pronunciation ; 29 November 1926[1] – 25 July 2019[2]) was a Tunisian statesman who served as the 6th president of Tunisia from 31 December 2014 until his death on 25 July 2019.[3] Previously, he served as the minister of Foreign Affairs from 1981 to 1986 and as the prime minister from February 2011 to December 2011.[4][5]

pronunciation ; 29 November 1926[1] – 25 July 2019[2]) was a Tunisian statesman who served as the 6th president of Tunisia from 31 December 2014 until his death on 25 July 2019.[3] Previously, he served as the minister of Foreign Affairs from 1981 to 1986 and as the prime minister from February 2011 to December 2011.[4][5]

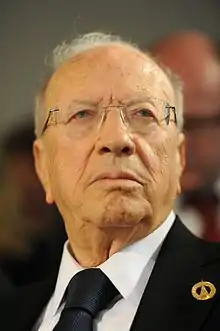

Beji Caid Essebsi الباجي قائد السبسي | |

|---|---|

Essebsi in 2011 | |

| President of Tunisia | |

| In office 31 December 2014 – 25 July 2019 | |

| Prime Minister | Mehdi Jomaa Habib Essid Youssef Chahed |

| Preceded by | Moncef Marzouki |

| Succeeded by | Mohamed Ennaceur |

| Prime Minister of Tunisia | |

| In office 28 February 2011 – 24 December 2011 | |

| President | Fouad Mebazaa (Acting) Moncef Marzouki |

| Preceded by | Mohamed Ghannouchi |

| Succeeded by | Hamadi Jebali |

| Speaker of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 14 March 1990 – 9 October 1991 | |

| President | Zine El Abidine Ben Ali |

| Preceded by | Slaheddine Baly |

| Succeeded by | Habib Boularès |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 15 April 1981 – 15 September 1986 | |

| Prime Minister | Mohammed Mzali Rachid Sfar |

| Preceded by | Hassen Belkhodja |

| Succeeded by | Hédi Mabrouk |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Mohamed Beji Caid Essebsi 29 November 1926 Sidi Bou Said, French Tunisia |

| Died | 25 July 2019 (aged 92) Tunis, Tunisia |

| Resting place | Jellaz Cemetery |

| Political party | Nidaa Tounes (2012–2019) |

| Other political affiliations | Neo Destour/PSD/RCD (1941–2005) Independent (2011–2012) |

| Spouse | Chadlia Farhat Essebsi

(m. 1958) |

| Children | 4 |

| Signature |  |

Essebsi's political career spanned six decades, culminating in his leadership of Tunisia in its transition to democracy.[6] Essebsi was the founder of the Nidaa Tounes political party, which won a plurality in the 2014 parliamentary election. In December 2014, he won the first regular presidential election following the Tunisian Revolution, becoming Tunisia's first democratically elected president.[7]

Early life

Born in 1926, in Sidi Bou Said to an elite family originally from Sardinia (Italy), he was the great-grandson of Ismail Caïd Essebsi, a Sardinian kidnapped by Barbary corsairs in Ottoman Tunisia along the coasts of the island at the beginning of the nineteenth century, who then became a mamluk leader raised with the ruling family after converting to Islam and was later recognized as a free man when he became an important member of the government.[8][9]

Political career

Essebsi's first involvement in politics came in 1941, when he joined the Neo Destour youth organization in Hammam-Lif.[10][11] He went to France in 1950 to study law in Paris.[12] He began his career as a lawyer defending Neo-Destour activists.[12][13] Essebsi later joined Tunisia's leader Habib Bourguiba, as supporter of the separatist movement and later as his adviser following the country's independence from France in 1956.[13]

Essebsi, a protégé of Bourguiba, held various posts under Bourguiba[6] from 1957 to 1971, including chief of the regional administration,[14] general director of the Sûreté nationale,[12] Interior Minister in 1965,[12] Minister-Delegate to the Prime Minister, Defense Minister in 1969,[12] and then Ambassador to Paris.[13]

From October 1971 to January 1972, he advocated greater democracy in Tunisia and resigned his function, then returned to Tunis.[15]

In April 1981, he came back to the government under Mohamed Mzali as Minister of Foreign Affairs, serving until September 1986.[9][10] In 1987, he switched allegiance following Ben Ali's removal of Bourguiba from power. He was appointed as Ambassador to West Germany. From 1990 to 1991, he was the Speaker of the Chamber of Deputies.[10]

Interim Prime Minister in 2011

On 27 February 2011, in the aftermath of the Tunisian Revolution, Tunisian Prime Minister Mohamed Ghannouchi resigned following a day of clashes in Tunis with five protesters being killed. On the same day, acting President Fouad Mebazaa appointed Caïd Essebsi as the new Prime Minister, describing him as "a person with an impeccable political and private life, known for his profound patriotism, his loyalty and his self-sacrifice in serving his country." The mostly young protesters however continued taking their discontent to the streets, criticizing the unilateral appointment of Caïd Essebsi without further consultation.[16]

On 5 May accusations of the former Interior Minister Farhat Rajhi that a coup d'etat was being prepared against the possibility of the Islamist Ennahda Party winning the Constituent Assembly election in October. This, again, led to several days of fierce anti-Government protests and clashes on the streets.[17] In the interview disseminated on Facebook, Rajhi called Caïd Essebsi a "liar", whose government had been manipulated by the old Ben Ali circles.[18] Caïd Essebsi strongly rejected Rajhi's accusations as "dangerous and irresponsible lies, [aimed at spreading] chaos in the country" and also dismissed him from his post as director of the High Commission for Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, which he had retained after being dismissed from the office as Interior Minister already on 8 March. Nevertheless, Ennahda's president Rached Ghannouchi further fueled the suspicions, stating that "Tunisians doubt the credibility of the Transitional Government."[17]

After the elections in October, Caïd Essebsi left office on 24 December 2011 when the new Interim President Moncef Marzouki appointed Hamadi Jebali of the Islamist Ennahda, which had become the largest parliamentary group.[19]

2014 elections

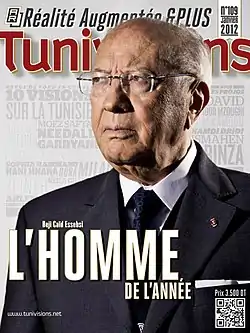

Following his departure from office, Caïd Essebsi founded the secular Nidaa Tounes party, which won a plurality of the seats in the October 2014 parliamentary election.[20] He was also the party's candidate in the country's first free presidential elections, in November 2014.[21]

On 22 December 2014, official election results showed that Essebsi had defeated incumbent President Moncef Marzouki in the second round of voting, receiving 55.68% of the vote.[22] After the polls closed the previous day, Essebsi said on local television that he dedicated his victory to "the martyrs of Tunisia".[23]

President of Tunisia

.jpg.webp)

Essebsi was sworn in as President on 31 December 2014 at the age of 88, he was the first freely elected president of modern Tunisia. He played a vital role in helping ensure that, more than any other Arab state, the North African country preserved many of the essential gains of the Arab spring movement.[24] He vowed on that occasion to "be president of all Tunisian men and women without exclusion" and stressed the importance of "consensus among all parties and social movements".[25]

On 3 August 2016, Essebsi appointed Youssef Chahed as a prime minister as the parliament withdrew confidence from Habib Essid's government.[26]

In 2017 he called for legal amendments to the inheritance law to ensure equal rights for men and women, and he called for Tunisian women to be able to marry non-Muslims, which he believed is not in direct conflict with Sharia or the Tunisian constitution.[27]

In 2018 he proposed a revision of Tunisian electoral law, which he felt contained many shortcomings going against the principles of the revolution.[28]

On 13 August 2018, he promised also to submit a bill to parliament soon which would aim to give women equal inheritance rights with men, as debate over the topic of inheritance reverberated throughout the Muslim world.[29]

Concerning the economic crisis of Tunisia, he declared that the year 2018 would be difficult but that the hope of economic revival was still possible.[30]

In April 2019, Essebsi announced he would not seek a second term in that year's presidential election, saying it was time to "open the door to the youth."[31]

Beji Caid Essebsi was recognized for his role in reinforcing democratic advances in the face of economic hardship and terrorism.[24]

Illness and death

On 27 June 2019, Essebsi was hospitalized at a military hospital in Tunis due to a serious illness.[32] The following day his condition stabilized.[33]

He was re-admitted to hospital on 24 July 2019, and died the following day, 25 July 2019 (which coincided with the 62nd anniversary of the abolition of the Tunisian monarchy), five months before his term was due to end.[34][35] In addition to Tunisia, which declared mourning 7 days, eight other countries announced mourning 3 days after the death of Essebsi, namely Libya, Algeria, Mauritania, Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon, Egypt and Cuba. Likewise, the United Nations stood for a minute of silence, and flew flags for a day, after Essebsi’s death. The electoral commission subsequently announced that Essebsi's successor would be elected sooner than the original date of 17 November,[2] due to the constitutional provision that in the event of the president's death, a permanent successor must be in office within 90 days.[7] The president of the Assembly of Representatives of the People, Mohamed Ennaceur, served as acting president in the meantime.[36] Ultimately, the election was pushed up to 15 September.[37]

His state funeral took place on 27 July in Carthage in the presence of dignitaries such as :

Mohamed Ennaceur (President of Tunisia)

Mohamed Ennaceur (President of Tunisia) Emmanuel Macron (President of France)

Emmanuel Macron (President of France) Felipe VI (King of Spain)

Felipe VI (King of Spain) Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa (President of Portugal)

Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa (President of Portugal) George Vella (President of Malta)

George Vella (President of Malta) Albert II (Prince of Monaco)

Albert II (Prince of Monaco) Joachim Gauck (Former President of Germany)

Joachim Gauck (Former President of Germany).svg.png.webp) Simonetta Sommaruga (Former President of Switzerland)

Simonetta Sommaruga (Former President of Switzerland) Abdelkader Bensalah (President of Algeria)

Abdelkader Bensalah (President of Algeria) Mahmoud Abbas (President of Palestine)

Mahmoud Abbas (President of Palestine) Fayez al-Sarraj (Chairman of the Presidential Council of Libya)

Fayez al-Sarraj (Chairman of the Presidential Council of Libya) Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani (Emir of Qatar)

Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani (Emir of Qatar) Ghassan Salame (Deputy Secretary General of the United Nations)

Ghassan Salame (Deputy Secretary General of the United Nations) Ahmed Aboul Gheit (Secretary General of the Arab League)

Ahmed Aboul Gheit (Secretary General of the Arab League) Taïeb Baccouche (Secretary General of the Arab Maghreb Union)

Taïeb Baccouche (Secretary General of the Arab Maghreb Union) Moulay Rachid (Prince of Morocco)

Moulay Rachid (Prince of Morocco) Hamad bin Mohammed Al Sharqi (Emir of Fujairah)

Hamad bin Mohammed Al Sharqi (Emir of Fujairah) Fuat Oktay (Vice President of Turkey)

Fuat Oktay (Vice President of Turkey).svg.png.webp) Stephane Dion (Special Envoy of the Prime Minister of Canada)

Stephane Dion (Special Envoy of the Prime Minister of Canada) Ulrich Brechbuhl (Counselor of the United States Department of State).[38]

Ulrich Brechbuhl (Counselor of the United States Department of State).[38]

A procession took place from the Carthage Palace to Jellaz Cemetery where he was buried.

Abdullah II (King of Jordan) also came to Tunisia on 29 July to offer condolences to the President of Tunisia Mohamed Ennaceur and to the family of President Beji Caid Essebsi.

Abdullah II (King of Jordan) also came to Tunisia on 29 July to offer condolences to the President of Tunisia Mohamed Ennaceur and to the family of President Beji Caid Essebsi.

Personal life

Essebsi married Chadlia Saïda Farhat on 8 February 1958.[14] The couple had four children: two daughters, Amel and Salwa, and two sons, Mohamed Hafedh and Khélil.[39]

His wife died on 15 September 2019, aged 83, nearly two months after her husband.[40]

Honours and awards

Tunisian national medals

| Ribbon bar | Honour |

|---|---|

| Grand Master & Grand Collar of the Order of Independence | |

| Grand Master & Grand Collar of the Order of the Republic | |

| Grand Master & Grand Collar of the National Order of Merit of Tunisia |

Foreign honors

.svg.png.webp)

Algeria:

Algeria:

Medal of Honor of the Republic of Algeria (3 January 2013)[41]

Medal of Honor of the Republic of Algeria (3 January 2013)[41]

Bahrain:

Bahrain:

Collar of the Order of Sheikh Isa bin Salman Al Khalifa (27 January 2016)[42]

Collar of the Order of Sheikh Isa bin Salman Al Khalifa (27 January 2016)[42]

Jordan:

Jordan:

Grand Cordon of the Supreme Order of the Renaissance (20 October 2015)[43]

Grand Cordon of the Supreme Order of the Renaissance (20 October 2015)[43]

KSA:

KSA:

Collar of the Order of Abdulaziz Al Saud (29 March 2019)[44]

Collar of the Order of Abdulaziz Al Saud (29 March 2019)[44]

Italy:

Italy:

Knight Grand Cross with Collar of Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (8 January 2017)[45]

Knight Grand Cross with Collar of Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (8 January 2017)[45]

Malta:

Malta:

Honorary Companions of Honour with Collar of the National Order of Merit (5 February 2019)[46]

Honorary Companions of Honour with Collar of the National Order of Merit (5 February 2019)[46]

Palestine:

Palestine:

Grand Collar of the State of Palestine (6 July 2017)[47]

Grand Collar of the State of Palestine (6 July 2017)[47]

Serbia:

Serbia:

Second Class of the Order of the Republic of Serbia (2016)[48]

Second Class of the Order of the Republic of Serbia (2016)[48]

Spain:

Spain:

_GC.svg.png.webp) Grand Cross of the Order of Civil Merit (28 October 1969)[49]

Grand Cross of the Order of Civil Merit (28 October 1969)[49]

Sweden:

Sweden:

Knight of the Order of the Seraphim (4 November 2015)[50]

Knight of the Order of the Seraphim (4 November 2015)[50]

Turkey:

Turkey:

Collar of the Order of the State of Republic of Turkey (27 December 2017)[51]

Collar of the Order of the State of Republic of Turkey (27 December 2017)[51]

Publications

- Bourguiba : le bon grain et l'ivraie, éd. Sud Éditions, Tunis, 2009, ISBN 978- 9973844996

- La Tunisie : la démocratie en terre d'islam (with Arlette Chabot), éd. Plon, Paris, 2016

Gallery

Essebsi giving a speech at the political office of the Socialist Destourian Party.

Essebsi giving a speech at the political office of the Socialist Destourian Party. Essebsi in Stade Chedly Zouiten in 1960.

Essebsi in Stade Chedly Zouiten in 1960. Essebsi decorated by Habib Bourguiba in 1966.

Essebsi decorated by Habib Bourguiba in 1966. Essebsi as Minister of Defense.

Essebsi as Minister of Defense. Essebsi with president Bourguiba

Essebsi with president Bourguiba Beji Caid Essebsi at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1981.

Beji Caid Essebsi at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1981. Essebsi and Ahmed Taleb Ibrahimi signing a treaty between Tunisia and Algeria in 1983.

Essebsi and Ahmed Taleb Ibrahimi signing a treaty between Tunisia and Algeria in 1983. Beji Caid Essebsi and Hillary Clinton in Washington in 2011.

Beji Caid Essebsi and Hillary Clinton in Washington in 2011..jpg.webp) Essebsi at a press conference with Italian Prime Minister Berlusconi in 2011.

Essebsi at a press conference with Italian Prime Minister Berlusconi in 2011.

.jpg.webp) Essebsi during meeting with John Kerry in May 2015.

Essebsi during meeting with John Kerry in May 2015. Essebsi receiving a delegation in the presidential palace.

Essebsi receiving a delegation in the presidential palace..jpg.webp) Essebsi oversees a MOU between his adviser Mohsen Marzouk and John Kerry in 2015.

Essebsi oversees a MOU between his adviser Mohsen Marzouk and John Kerry in 2015. President Essebsi with the Vice President of India, Hamid Ansari, in June 2016.

President Essebsi with the Vice President of India, Hamid Ansari, in June 2016. Essebsi with Secretary-General of the ITU Houlin Zhao.

Essebsi with Secretary-General of the ITU Houlin Zhao. Beji Caid Essebsi at the Carthage Presidential Palace.

Beji Caid Essebsi at the Carthage Presidential Palace..jpg.webp)

_by_Karim2k.jpg.webp) Funeral of Beji Caid Essebsi in 2019.

Funeral of Beji Caid Essebsi in 2019..jpg.webp) The funeral procession of President Beji Caid Essebsi.

The funeral procession of President Beji Caid Essebsi..jpg.webp) The car transporting Essebsi during his funeral.

The car transporting Essebsi during his funeral..jpg.webp) The body of the late Tunisian President Beji Caid Essebsi

The body of the late Tunisian President Beji Caid Essebsi

References

- Sayed Mohamed Mahdi al Tajir, The International Who's Who of the Arab World (1978), page 137.

- "Tunisia's first freely elected president dies". BBC. 25 July 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- "Tunisian President Beji Caid Essebsi dies aged 92". France 24. 25 July 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Tunisian PM Mohammed Ghannouchi resigns over protests", BBC News, 27 February 2011.

- "Tunisian prime minister resigns amid protests". Reuters. 27 February 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Carlotta Gall & Lilia Blaise, Béji Caïd Essebsi, President Who Guided Tunisia to Democracy, Dies at 92, New York Times (25 July 2019).

- Parker, Claire; Fahim, Kareem (25 July 2019). "Tunisian President Beji Caid Essebsi dies at 92". Washington Post. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Mohamed El Aziz Ben Achour, Catégories de la société tunisoise dans la deuxième moitié du XIXe siècle, éd. Institut national d'archéologie et d'art, Tunis, 1989 (in French)

- Kéfi, Ridha (15 March 2005). "Béji Caïd Essebsi". Jeune Afrique (in French). Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- "President Essebsi, a lifetime in Tunisia politics". Euronews. 22 December 2014. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- "Essebsi retrouve ses racines à Hammam-Lif!" (in French). Espace Manager. 20 October 2014. Archived from the original on 24 December 2014. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- Bobin, Frederic (25 July 2019). "Tunisie : le président Essebsi, symbole des ambivalences de la révolution, est mort". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- Legg, Paul (25 July 2019). "Beji Caid Essebsi obituary". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- "Annuaire des Personnalités: Béji Caïd Essebsi". Leaders (in French). 19 September 2015. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "Avec la mort de Béji Caïd Essebsi, la Tunisie perd un fondateur". La Croix (in French). 25 July 2019. ISSN 0242-6056. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- Guidi, Francesco (1 March 2011). "Tunisian Prime Minister Mohammed Gannouchi resigns". About Oil. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- Guidi, Francesco (9 May 2011). "Tension returns to Tunisia with protests against the Transitional Government". About Oil. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- "Farhat Rajhi fonce, tête baissée, pour l'élection présidentielle". Business News (in French). 6 May 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Mzioudet, Houda (14 December 2011), "Ennahda's Jebali Appointed as Tunisian Prime Minister", Tunisia, archived from the original on 17 January 2012, retrieved 21 December 2011

- "Tunisia's Essebsi: The 88-year-old comeback kid". BBC. 31 December 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Marks, Monica (29 October 2014). "The Tunisian election result isn't simply a victory for secularism over Islamism". Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- Patrick Markey; Tarek Amara (22 December 2014). "Essebsi elected Tunisian president with 55.68 percent". Reuters. Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- "Tunisia election: Essebsi claims historic victory". BBC News. 22 December 2014. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- "President of Tunisia who sought to reinforce democratic advances in the face of economic hardship and terrorism".

- "Tunisian secular leader Essebsi sworn in as new president". Reuters. 31 December 2014. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Nadhif, Ahmed (18 August 2018). "How the new government plans to save Tunisia". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- Simon Speakman Cordall; Mona Mahmood (28 November 2011). "We are an example to the Arab world': Tunisia's radical marriage proposals". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- Dahmani, Frida (23 March 2018). "Pourquoi Béji Caid Essebsi veut faire amender la loi électorale". Jeune Afrique (in French). Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- "Tunisian president backs inheritance equality for women despite opposition". Middle East Eye. 3 August 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- "Viewpoint: President Beji Caid Essebsi, President of Tunisia". Oxford Business Group. 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- "Tunisia's 92-year-old president will not seek re-election". BBC. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- Tarek Amara; Ulf Laessing (28 June 2019). "Tunisian president hospitalised 'in severe health crisis': presidency". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- "Health of Tunisian president improves significantly, he calls defense minister". Reuters. 28 June 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Anabel, Ynug (25 July 2019). "Tunisia: President Beji Caid Essebsi dies at age 92 on Republic Day". Afrika News. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- "Tunisia's President Essebsi dies aged 92 after severe illness". DailySabah. 25 July 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- Amara, Tarek (26 July 2019). "Mourning leader, Tunisians look forward to smooth transition". Reuters. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- "Tunisie: l'élection présidentielle reprogrammée au 15 septembre". Le Figaro (in French). 25 July 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- Amara, Tarek (27 July 2019). "Tunisia bids farewell to president Essebsi at state funeral". Reuters. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Mariem (8 January 2015). "Les premières déclarations de la Première Dame de Tunisie, Chadlia Saïda Caïd Essebsi" (in French). Baya. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- Former Tunisian president's widow dies

- "Le double hommage de Bouteflika à 11 personnalités tunisiennes". Leaders (in French). 3 January 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- علي رجب (27 January 2016). "بالصور.. العاهل البحريني يمنح الرئيس التونسي وسام الشيخ عيسى". بوابة فيتو (in Arabic). Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- "الملك للسبسي: الأردن مستعد لدعم تونس على جميع المستويات". Alghad (in Arabic). 20 October 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- "King Salman, Tunisian president hold talks, oversee signing of two deals & confer medals". Saudigazette. 29 March 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- "Conferimento di onorifi cenze dell'Ordine Al merito della Repubblica italiana". Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana (in Italian). 107: 130. 10 May 2017.

- "Government Notices published in Govt. Gazette No. 20,137 of 15th February 2019". Government services and information of Malta. 15 February 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- "الرئيس يقلد نظيره التونسي القلادة الكبرى لدولة فلسطين". Wafa (in Arabic). 6 July 2017. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- "Ukazi o odlikovanjima".

- "Decreto 2463/1969, de 1 de octubre, por el que se concede la Gran Cruz de la Orden del Mérito Civil al señor Beji Caid Es-Sebsi" (in Swedish). Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- "Statsbesök från Tunisien – dag 1 - Sveriges Kungahus". Kungahuset (in Swedish). November 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- Chennoufi, Anouar (28 December 2017). "Fin de la visite d'Etat du président turc Recep Tayyip Erdogan en Tunisie". Tunivisions (in French). Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- "Béji Caïd Essebsi reçoit les insignes de Docteur Honoris Causa à l'université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne". Business Newss (in French). 7 April 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Chahla, Marwan (26 October 2015). "Le Prix du Fondateur du Crisis Group à Caïd Essebsi et Ghannouchi". Kapitalis (in French). Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- "Tunisie : la clé d'or d'Amman remise à Caïd Essebsi". Turess (in French). 21 October 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- "BCE passe en revue les accords signés dans le secteur touristique avec Soltane Ben Salmane Ben Abdelaziz". Business News (in French). 20 October 2017. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Chennoufi, Anouar (29 December 2017). "Tunivisions choisit Béji Caïd Essebsi comme 'Meilleure Personnalité Politique' en 2017". Tunivisions (in French). Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- "Béji Caid Essebsi reçoit le prix du Leadership par la fondation Global Hope Coalition". Al HuffPost Maghreb (in French). 28 September 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2019.