Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty (English: /ˈtʃɪŋ/ CHING), officially the Great Qing,[lower-alpha 5][lower-alpha 6] was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history.[lower-alpha 7] It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speaking ethnic group who unified other Jurchen tribes to form a new "Manchu" ethnic identity. The dynasty was officially proclaimed in 1636 in Manchuria (modern-day Northeast China and Outer Manchuria). It seized control of Beijing in 1644, then later expanded its rule over the whole of China proper and Taiwan, and finally expanded into Inner Asia. The dynasty lasted until 1912 when it was overthrown in the Xinhai Revolution. In orthodox Chinese historiography, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the Ming dynasty and succeeded by the Republic of China. The multiethnic Qing empire lasted for almost three centuries and assembled the territorial base for modern China. It was the largest imperial dynasty in the history of China and in 1790 the fourth-largest empire in world history in terms of territorial size. With 419,264,000 citizens in 1907, it was the world's most populous country at the time.

Great Qing | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1636–1912 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png.webp) Flag

(1889–1912)  Imperial seal[lower-alpha 2]

(1909–1912) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: 鞏金甌 Gǒng Jīn'ōu "Cup of Solid Gold" (1911–1912) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

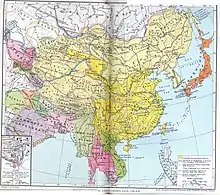

The Qing dynasty at its greatest extent in 1760. Territory under its control shown in dark green; territory claimed but uncontrolled shown in light green. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Mukden (Shenyang) (1636–1644)[lower-alpha 3] Beijing (Peking) (1644–1912)[lower-alpha 4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Largest city | Peking | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Manchu,[1] Mandarin Chinese[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ethnic groups | Han, Manchus, Mongols, Tibetans, Uyghurs, and others | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | State religion: Confucianism[3] Majority: Chinese folk religion, Chinese Buddhism, and Taoism Minority: Tibetan Buddhism, Heaven worship, Islam, Shamanism, Christianity, and others | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Chinese | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy (1636–1911) Constitutional monarchy (1911–1912) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1636–1643 (founder) | Taizong Emperor | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1643–1661 (first in Beijing) | Shunzhi Emperor | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1908–1912 (last) | Xuantong Emperor | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regent | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1643–1650 | Dorgon, Prince Rui | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1908–1911 | Zaifeng, Prince Chun | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1911 | Yikuang, Prince Qing | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1911–1912 | Yuan Shikai | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Deliberative Council (1636–1733) None (rule by decree) (1733–1910) Advisory Council (1910–1912) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Late modern | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Foundation | 1636 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Conquest of China | 1644–1662 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Conquest of Tibet, Mongolia, Xinjiang | 1687–1757 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Ten Great Campaigns | 1755–1792 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1st Opium War | 1839–1842 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Taiping Rebellion | 1850–1864 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 2nd Opium War | 1856–1860 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Self-Strengthening Movement | 1861–1895 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1894–1895 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1898 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1900–1901 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• Late Qing reforms | 1901–1911 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1911–1912 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• End of monarchy | 12 February 1912 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1700[4] | 8,800,000 km2 (3,400,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1790[4] | 14,700,000 km2 (5,700,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1860[4] | 13,400,000 km2 (5,200,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Cash (wén) Tael (liǎng) Paper money | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Qing dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 清朝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynastic name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 大清 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Дайчин Улс | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian script | ᠳᠠᠢᠢᠴᠢᠩ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu script | ᡩᠠᡳ᠌ᠴᡳᠩ ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Abkai | Daiqing gurun | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Möllendorff | Daicing gurun | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

ANCIENT | |||

IMPERIAL | |||

MODERN | |||

Related articles

| |||

In the late sixteenth century, Nurhaci, leader of the House of Aisin-Gioro, began organizing "Banners", which were military-social units that included Manchu, Han, and Mongol elements. Nurhaci united clans to create a Manchu ethnic identity and officially founded the Later Jin dynasty in 1616. His son Hong Taiji renamed the dynasty "Great Qing" and elevated the realm to an empire in 1636. As Ming control disintegrated, peasant rebels conquered Beijing in 1644, but the Ming general Wu Sangui opened the Shanhai Pass to the armies of the regent Prince Dorgon, who defeated the rebels, seized the capital, and took over the government. Resistance from Ming loyalists in the south and the Revolt of the Three Feudatories delayed the complete conquest until 1683. The Kangxi Emperor (1661–1722) consolidated control, maintained the Manchu identity, patronized Tibetan Buddhism, and relished the role of a Confucian ruler. Han officials worked under or in parallel with Manchu officials. The dynasty also adapted the ideals of the tributary system in asserting superiority over peripheral countries such as Korea and Vietnam, while extending control over Tibet, Mongolia, and Xinjiang.

The height of Qing glory and power was reached in the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (1735–1796). He led Ten Great Campaigns that extended Qing control into Inner Asia and personally supervised Confucian cultural projects. After his death, the dynasty faced changes in the world system, foreign intrusion, internal revolts, population growth, economic disruption, official corruption, and the reluctance of Confucian elites to change their mindsets. With peace and prosperity, the population rose to some 400 million, but taxes and government revenues were fixed at a low rate, soon leading to fiscal crisis. Following China's defeat in the Opium Wars, Western colonial powers forced the Qing government to sign "unequal treaties", granting them trading privileges, extraterritoriality and treaty ports under their control. The Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864) and the Dungan Revolt (1862–1877) in Central Asia led to the deaths of over 20 million people, from famine, disease, and war. The Tongzhi Restoration of the 1860s brought vigorous reforms and the introduction of foreign military technology in the Self-Strengthening Movement. Defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War of 1895 led to loss of suzerainty over Korea and cession of Taiwan to Japan. The ambitious Hundred Days' Reform of 1898 proposed fundamental change, but the Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908), who had been the dominant voice in the national government for more than three decades, turned it back in a coup.

In 1900 anti-foreign "Boxers" killed many Chinese Christians and foreign missionaries; in retaliation, the foreign powers invaded China and imposed a punitive Boxer Indemnity. In response, the government initiated unprecedented fiscal and administrative reforms, including elections, a new legal code, and abolition of the examination system. Sun Yat-sen and revolutionaries debated reform officials and constitutional monarchists such as Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao over how to transform the Manchu-ruled empire into a modern Han nation. After the deaths of the Guangxu Emperor and Cixi in 1908, Manchu conservatives at court blocked reforms and alienated reformers and local elites alike. The Wuchang Uprising on 10 October 1911 led to the Xinhai Revolution. The abdication of Puyi, the last emperor, on 12 February 1912, brought the dynasty to an end. In 1917, it was briefly restored in an episode known as the Manchu Restoration, but this was neither recognized by the Beiyang government of the Republic of China nor the international community.

Names

Hong Taiji named the Great Qing dynasty in 1636.[5] There are competing explanations on the meaning of Qīng (lit. "clear" or "pure"). The name may have been selected in reaction to the name of the Ming dynasty (明), which consists of the Chinese characters for "sun" (日) and "moon" (月), both associated with the fire element of the Chinese zodiacal system. The character Qīng (清) is composed of "water" (氵) and "azure" (青), both associated with the water element. This association would justify the Qing conquest as defeat of fire by water. The water imagery of the new name may also have had Buddhist overtones of perspicacity and enlightenment and connections with the Bodhisattva Manjusri.[6] The Manchu name daicing, which sounds like a phonetic rendering of Dà Qīng or Dai Ching, may in fact have been derived from a Mongolian word "ᠳᠠᠢᠢᠴᠢᠨ, дайчин" that means "warrior". Daicing gurun may therefore have meant "warrior state", a pun that was intelligible only to Manchu and Mongol peoples. In the later part of the dynasty, however, even the Manchus themselves had forgotten this possible meaning.[7]

Early European writers used the term "Tartar" indiscriminately for all the peoples of Northern Eurasia but in the 17th century Catholic missionary writings established "Tartar" to refer only to the Manchus and "Tartary" for the lands they ruled.[8]

After conquering "China proper", the Manchus identified their state as "China" (中國, Zhōngguó; "Middle Kingdom"), and referred to it as Dulimbai Gurun in Manchu (Dulimbai means "central" or "middle," gurun means "nation" or "state"). The emperors equated the lands of the Qing state (including present-day Northeast China, Xinjiang, Mongolia, Tibet and other areas) as "China" in both the Chinese and Manchu languages, defining China as a multi-ethnic state, and rejecting the idea that "China" only meant Han areas. They used both "China" and "Qing" to refer to their state in official documents.[9] In the Chinese-language versions of its treaties and its maps of the world, the Qing government used "Qing" and "China" interchangeably.[10]

In English, the Qing dynasty is sometimes known as the "Manchu dynasty".[11] It is rendered as "Ch'ing dynasty" using the Wade–Giles romanization system.

History

Formation

The Qing dynasty was founded not by the Han people, who constitute the majority of the Chinese population, but by the Manchus, descendants of a sedentary farming people known as the Jurchens, a Tungusic people who lived around the region now comprising the Chinese provinces of Jilin and Heilongjiang.[12] The Manchus are sometimes mistaken for a nomadic people,[13] which they were not.[14][15]

Nurhaci

What was to become the Manchu state was founded by Nurhaci, the chieftain of a minor Jurchen tribe – the Aisin-Gioro – in Jianzhou in the early 17th century. Nurhaci may have spent time in a Han household in his youth, and became fluent in Chinese and Mongolian languages, and read the Chinese novels Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Water Margin.[16][17] Originally a vassal of the Ming emperors, Nurhaci embarked on an intertribal feud in 1582 that escalated into a campaign to unify the nearby tribes. By 1616, he had sufficiently consolidated Jianzhou so as to be able to proclaim himself Khan of the Great Jin in reference to the previous Jurchen-ruled dynasty.[18]

Two years later, Nurhaci announced the "Seven Grievances" and openly renounced the sovereignty of Ming overlordship in order to complete the unification of those Jurchen tribes still allied with the Ming emperor. After a series of successful battles, he relocated his capital from Hetu Ala to successively bigger captured Ming cities in Liaodong: first Liaoyang in 1621, then Shenyang (Manchu: Mukden) in 1625.[18]

Furthermore, the Khorchin proved a useful ally in the war, lending the Jurchens their expertise as cavalry archers. To guarantee this new alliance, Nurhaci initiated a policy of inter-marriages between the Jurchen and Khorchin nobilities, while those who resisted were met with military action. This is a typical example of Nurhaci's initiatives that eventually became official Qing government policy. During most of the Qing period, the Mongols gave military assistance to the Manchus.[19]

Hong Taiji

Nurhaci died in 1626, and was succeeded by his eighth son, Hong Taiji. Although Hong Taiji was an experienced leader and the commander of two Banners, the Jurchens suffered defeat in 1627, in part due to the Ming's newly acquired Portuguese cannons. To redress the technological and numerical disparity, Hong Taiji in 1634 created his own artillery corps from his existing Han troops, who cast their own cannons in the European design with the help of defector Chinese metallurgists. One of the defining events of Hong Taiji's reign was the official adoption of the name "Manchu" for the united Jurchen people in November 1635. In 1635, the Manchus' Mongol allies were fully incorporated into a separate Banner hierarchy under direct Manchu command. In April 1636, Mongol nobility of Inner Mongolia, Manchu nobility and the Han mandarin recommended that Hong as the khan of Later Jin should be the emperor of the Great Qing empire.[20][21] When he was presented with the imperial seal of the Yuan dynasty after the defeat of the last Khagan of the Mongols, Hong Taiji renamed his state from "Great Jin" to "Great Qing" and elevated his position from Khan to Emperor, suggesting imperial ambitions beyond unifying the Manchu territories. Hong Taiji then proceeded to invade Korea again in 1636.

Meanwhile, Hong Taiji set up a rudimentary bureaucratic system based on the Ming model. He established six boards or executive level ministries in 1631 to oversee finance, personnel, rites, military, punishments, and public works. However, these administrative organs had very little role initially, and it was not until the eve of completing the conquest ten years later that they fulfilled their government roles.[22]

Hong Taiji staffed his bureaucracy with many Han Chinese, including newly surrendered Ming officials, but ensured Manchu dominance by an ethnic quota for top appointments. Hong Taiji's reign also saw a fundamental change of policy towards his Han Chinese subjects. Nurhaci had treated Han in Liaodong according to how much grain they had: those with less than 5 to 7 sin were treated badly, while those with more were rewarded with property. Due to a Han revolt in 1623, Nurhaci turned against them and ordered that they no longer be trusted and enacted discriminatory policies and killings against them. He ordered that Han who assimilated to the Jurchen (in Jilin) before 1619 be treated equally with Jurchens, not like the conquered Han in Liaodong. Hong Taiji recognized the need to attract Han Chinese, explaining to reluctant Manchus why he needed to treat the Ming defector General Hong Chengchou leniently.[23] Hong Taiji incorporated Han into the Jurchen "nation" as full (if not first-class) citizens, obligated to provide military service. By 1648, less than one-sixth of the bannermen were of Manchu ancestry.[24]

Claiming the Mandate of Heaven

.jpg.webp)

Hong Taiji died suddenly in September 1643. As the Jurchens had traditionally "elected" their leader through a council of nobles, the Qing state did not have a clear succession system. The leading contenders for power were Hong Taiji's oldest son Hooge and Hong Taiji's half brother Dorgon. A compromise installed Hong Taiji's five-year-old son, Fulin, as the Shunzhi Emperor, with Dorgon as regent and de facto leader of the Manchu nation.

Meanwhile, Ming government officials fought against each other, against fiscal collapse, and against a series of peasant rebellions. They were unable to capitalise on the Manchu succession dispute and the presence of a minor as emperor. In April 1644, the capital, Beijing, was sacked by a coalition of rebel forces led by Li Zicheng, a former minor Ming official, who established a short-lived Shun dynasty. The last Ming ruler, the Chongzhen Emperor, committed suicide when the city fell to the rebels, marking the official end of the dynasty.

Li Zicheng then led rebel forces numbering some 200,000[25] to confront Wu Sangui, at Shanhai Pass, a key pass of the Great Wall, which defended the capital. Wu Sangui, caught between a Chinese rebel army twice his size and a foreign enemy he had fought for years, cast his lot with the familiar Manchus. Wu Sangui may have been influenced by Li Zicheng's mistreatment of wealthy and cultured officials, including Li's own family; it was said that Li took Wu's concubine Chen Yuanyuan for himself. Wu and Dorgon allied in the name of avenging the death of the Chongzhen Emperor. Together, the two former enemies met and defeated Li Zicheng's rebel forces in battle on May 27, 1644.[26]

The newly allied armies captured Beijing on 6 June. The Shunzhi Emperor was invested as the "Son of Heaven" on 30 October. The Manchus, who had positioned themselves as political heirs to the Ming emperor by defeating Li Zicheng, completed the symbolic transition by holding a formal funeral for the Chongzhen Emperor. However, conquering the rest of China Proper took another seventeen years of battling Ming loyalists, pretenders and rebels. The last Ming pretender, Prince Gui, sought refuge with the King of Burma, Pindale Min, but was turned over to a Qing expeditionary army commanded by Wu Sangui, who had him brought back to Yunnan province and executed in early 1662.

The Qing had taken shrewd advantage of Ming civilian government discrimination against the military and encouraged the Ming military to defect by spreading the message that the Manchus valued their skills.[27] Banners made up of Han Chinese who defected before 1644 were classed among the Eight Banners, giving them social and legal privileges. Han defectors swelled the ranks of the Eight Banners so greatly that ethnic Manchus became a minority—only 16% in 1648, with Han Bannermen dominating at 75% and Mongol Bannermen making up the rest.[28] Gunpowder weapons like muskets and artillery were wielded by the Chinese Banners.[29] Normally, Han Chinese defector troops were deployed as the vanguard, while Manchu Bannermen acted as reserve forces or in the rear and were used predominantly for quick strikes with maximum impact, so as to minimize ethnic Manchu losses.[30]

This multi-ethnic force conquered China for the Qing,[31] The three Liaodong Han Bannermen officers who played key roles in the conquest of southern China were Shang Kexi, Geng Zhongming, and Kong Youde, who governed southern China autonomously as viceroys for the Qing after the conquest.[32] Han Chinese Bannermen made up the majority of governors in the early Qing, stabilizing Qing rule.[33] To promote ethnic harmony, a 1648 decree allowed Han Chinese civilian men to marry Manchu women from the Banners with the permission of the Board of Revenue if they were registered daughters of officials or commoners, or with the permission of their banner company captain if they were unregistered commoners. Later in the dynasty the policies allowing intermarriage were done away with.[34]

The first seven years of the young Shunzhi Emperor's reign were dominated by Dorgon's regency. Because of his own political insecurity, Dorgon followed Hong Taiji's example by ruling in the name of the emperor at the expense of rival Manchu princes, many of whom he demoted or imprisoned under one pretext or another. Dorgon's precedents and example cast a long shadow. First, the Manchus had entered "South of the Wall" because Dorgon had responded decisively to Wu Sangui's appeal, then, instead of sacking Beijing as the rebels had done, Dorgon insisted, over the protests of other Manchu princes, on making it the dynastic capital and reappointing most Ming officials. No major Chinese dynasty had directly taken over its immediate predecessor's capital, but keeping the Ming capital and bureaucracy intact helped quickly stabilize the regime and sped up the conquest of the rest of the country. Dorgon then drastically reduced the influence of the eunuchs, a major force in the Ming bureaucracy, and directed Manchu women not to bind their feet in the Chinese style.[35]

However, not all of Dorgon's policies were equally popular or as easy to implement. The controversial July 1645 edict (the "haircutting order") forced adult Han Chinese men to shave the front of their heads and comb the remaining hair into the queue hairstyle which was worn by Manchu men, on pain of death.[36] The popular description of the order was: "To keep the hair, you lose the head; To keep your head, you cut the hair."[35] To the Manchus, this policy was a test of loyalty and an aid in distinguishing friend from foe. For the Han Chinese, however, it was a humiliating reminder of Qing authority that challenged traditional Confucian values.[37] The order triggered strong resistance in Jiangnan.[38] In the ensuing unrest, some 100,000 Han were slaughtered.[39][40][41]

On 31 December 1650, Dorgon suddenly died during a hunting expedition, marking the start of the Shunzhi Emperor's personal rule. Because the emperor was only 12 years old at that time, most decisions were made on his behalf by his mother, Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang, who turned out to be a skilled political operator. Although his support had been essential to Shunzhi's ascent, Dorgon had centralised so much power in his hands as to become a direct threat to the throne. So much so that upon his death he was bestowed the extraordinary posthumous title of Emperor Yi (義皇帝), the only instance in Qing history in which a Manchu "prince of the blood" (親王) was so honored. Two months into Shunzhi's personal rule, however, Dorgon was not only stripped of his titles, but his corpse was disinterred and mutilated.[42] Dorgon's fall from grace also led to the purge of his family and associates at court, thus reverting power back to the person of the emperor. Shunzhi's promising start was cut short by his early death in 1661 at the age of 24 from smallpox. He was succeeded by his third son Xuanye, who reigned as the Kangxi Emperor.

The Manchus sent Han Bannermen to fight against Koxinga's Ming loyalists in Fujian.[43] They removed the population from coastal areas in order to deprive Koxinga's Ming loyalists of resources. This led to a misunderstanding that Manchus were "afraid of water". Han Bannermen carried out the fighting and killing, casting doubt on the claim that fear of the water led to the coastal evacuation and ban on maritime activities.[44] Even though a poem refers to the soldiers carrying out massacres in Fujian as "barbarians", both Han Green Standard Army and Han Bannermen were involved and carried out the worst slaughter.[45] 400,000 Green Standard Army soldiers were used against the Three Feudatories in addition to the 200,000 Bannermen.[46]

Kangxi Emperor's reign and consolidation

The sixty-one year reign of the Kangxi Emperor was the longest of any emperor of China and marked the beginning of the "High Qing" era, the zenith of the dynasty's social, economic and military power. The early Manchu rulers established two foundations of legitimacy that help to explain the stability of their dynasty. The first was the bureaucratic institutions and the neo-Confucian culture that they adopted from earlier dynasties.[47] Manchu rulers and Han Chinese scholar-official elites gradually came to terms with each other. The examination system offered a path for ethnic Han to become officials. Imperial patronage of Kangxi Dictionary demonstrated respect for Confucian learning, while the Sacred Edict of 1670 effectively extolled Confucian family values. His attempts to discourage Chinese women from foot binding, however, were unsuccessful.

The second major source of stability was the Central Asian aspect of their Manchu identity, which allowed them to appeal to Mongol, Tibetan and Uighur constituents.[48] The Qing used the title of Emperor (Huangdi) in Chinese, while among Mongols the Qing monarch was referred to as Bogda khan (wise Khan), and referred to as Gong Ma in Tibet.[49] The Qianlong Emperor propagated the image of himself as a Buddhist sage ruler, a patron of Tibetan Buddhism.[50] The Kangxi Emperor also welcomed to his court Jesuit missionaries, who had first come to China under the Ming.

Kangxi's reign started when he was eight years old. To prevent a repeat of Dorgon's monopolizing of power, on his deathbed his father hastily appointed four regents who were not closely related to the imperial family and had no claim to the throne. However, through chance and machination, Oboi, the most junior of the four, gradually achieved such dominance as to be a potential threat. Even though Oboi's loyalty was never an issue, his arrogance and conservatism led him into an escalating conflict with the young emperor. In 1669 Kangxi, through trickery, disarmed and imprisoned Oboi – a significant victory for a fifteen-year-old emperor.

The young emperor faced challenges in maintaining control of his kingdom, as well. Three Ming generals singled out for their contributions to the establishment of the dynasty had been granted governorships in Southern China. They became increasingly autonomous, leading to the Revolt of the Three Feudatories, which lasted for eight years. Kangxi was able to unify his forces for a counterattack led by a new generation of Manchu generals. By 1681, the Qing government had established control over a ravaged southern China, which took several decades to recover.[51]

To extend and consolidate the dynasty's control in Central Asia, the Kangxi Emperor personally led a series of military campaigns against the Dzungars in Outer Mongolia. The Kangxi Emperor expelled Galdan's invading forces from these regions, which were then incorporated into the empire. Galdan was eventually killed in the Dzungar–Qing War.[52] In 1683, Qing forces received the surrender of Formosa (Taiwan) from Zheng Keshuang, grandson of Koxinga, who had conquered Taiwan from the Dutch colonists as a base against the Qing. Winning Taiwan freed Kangxi's forces for series of battles over Albazin, the far eastern outpost of the Tsardom of Russia. The 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk was China's first formal treaty with a European power and kept the border peaceful for the better part of two centuries. After Galdan's death, his followers, as adherents to Tibetan Buddhism, attempted to control the choice of the next Dalai Lama. Kangxi dispatched two armies to Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, and installed a Dalai Lama sympathetic to the Qing.[53]

Reigns of the Yongzheng and Qianlong emperors

The reigns of the Yongzheng Emperor (r. 1723–1735) and his son, the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–1796), marked the height of Qing power. Yet, as the historian Jonathan Spence puts it, the empire by the end of the Qianlong reign was "like the sun at midday". In the midst of "many glories", he writes, "signs of decay and even collapse were becoming apparent".[54]

After the death of the Kangxi Emperor in the winter of 1722, his fourth son, Prince Yong (雍親王), became the Yongzheng Emperor. In the later years of Kangxi's reign, Yongzheng and his brothers had fought, and there were unsubstantiated rumours that he had usurped the throne by tampering with the Kangxi's testament on the night when Kangxi died. In fact, his father had trusted him with delicate political issues and discussed state policy with him. When Yongzheng came to power at the age of 45, he felt a sense of urgency about the problems that had accumulated in his father's later years, and he did not need instruction on how to exercise power.[55] In the words of one recent historian, he was "severe, suspicious, and jealous, but extremely capable and resourceful",[56] and in the words of another, he turned out to be an "early modern state-maker of the first order".[57]

Yongzheng moved rapidly. First, he promoted Confucian orthodoxy and reversed what he saw as his father's laxness by cracking down on unorthodox sects and by decapitating an anti-Manchu writer his father had pardoned. In 1723 he outlawed Christianity and expelled Christian missionaries, though some were allowed to remain in the capital.[58] Next, he moved to control the government. He expanded his father's system of Palace Memorials, which brought frank and detailed reports on local conditions directly to the throne without being intercepted by the bureaucracy, and he created a small Grand Council of personal advisors, which eventually grew into the emperor's de facto cabinet for the rest of the dynasty. He shrewdly filled key positions with Manchu and Han Chinese officials who depended on his patronage. When he began to realize that the financial crisis was even greater than he had thought, Yongzheng rejected his father's lenient approach to local landowning elites and mounted a campaign to enforce collection of the land tax. The increased revenues were to be used for "money to nourish honesty" among local officials and for local irrigation, schools, roads, and charity. Although these reforms were effective in the north, in the south and lower Yangzi valley, where Kangxi had wooed the elites, there were long established networks of officials and landowners. Yongzheng dispatched experienced Manchu commissioners to penetrate the thickets of falsified land registers and coded account books, but they were met with tricks, passivity, and even violence. The fiscal crisis persisted.[59]

Yongzheng also inherited diplomatic and strategic problems. A team made up entirely of Manchus drew up the Treaty of Kyakhta (1727) to solidify the diplomatic understanding with Russia. In exchange for territory and trading rights, the Qing would have a free hand dealing with the situation in Mongolia. Yongzheng then turned to that situation, where the Zunghars threatened to re-emerge, and to the southwest, where local Miao chieftains resisted Qing expansion. These campaigns drained the treasury but established the emperor's control of the military and military finance.[60]

When Yongzheng Emperor died in 1735 his 24-year-old son, Prince Bao (寶親王), became the Qianlong Emperor. Qianlong personally led the Ten Great Campaigns to expand military control into present-day Xinjiang and Mongolia, putting down revolts and uprisings in Sichuan and parts of southern China while expanding control over Tibet.

The Qianlong Emperor launched several ambitious cultural projects, including the compilation of the Siku Quanshu, or Complete Repository of the Four Branches of Literature, the largest collection of books in Chinese history. Nevertheless, Qianlong used Literary Inquisition to silence opposition.[61] Beneath outward prosperity and imperial confidence, the later years of Qianlong's reign were marked by rampant corruption and neglect. Heshen, the emperor's handsome young favorite, took advantage of the emperor's indulgence to become one of the most corrupt officials in the history of the dynasty.[62] Qianlong's son, the Jiaqing Emperor (r. 1796–1820), eventually forced Heshen to commit suicide.

Population was stagnant for the first half of the 17th century due to civil wars and epidemics, but prosperity and internal stability gradually reversed this trend. The Qianlong Emperor bemoaned the situation by remarking, "The population continues to grow, but the land does not." The introduction of new crops from the Americas such as the potato and peanut allowed an improved food supply as well, so that the total population of China during the 18th century ballooned from 100 million to 300 million people. Soon farmers were forced to work ever-smaller holdings more intensely. The only remaining part of the empire that had arable farmland was Manchuria, where the provinces of Jilin and Heilongjiang had been walled off as a Manchu homeland. Despite prohibitions, by the 18th century Han Chinese streamed into Manchuria, both illegally and legally, over the Great Wall and Willow Palisade.

In 1796, open rebellion broke out among followers of the White Lotus Society, who blamed Qing officials, saying "the officials have forced the people to rebel." Officials in other parts of the country were also blamed for corruption, failing to keep the famine relief granaries full, poor maintenance of roads and waterworks, and bureaucratic factionalism. There soon followed uprisings of "new sect" Muslims against local Muslim officials, and Miao tribesmen in southwest China. The White Lotus Rebellion continued for eight years, until 1804, when badly run, corrupt, and brutal campaigns finally ended it.[63]

Rebellion, unrest and external pressure

.jpg.webp)

At the start of the dynasty, the Chinese empire continued to be the hegemonic power in East Asia. Although there was no formal ministry of foreign relations, the Lifan Yuan was responsible for relations with the Mongol and Tibetans in Central Asia, while the tributary system, a loose set of institutions and customs taken over from the Ming, in theory governed relations with East and Southeast Asian countries. The Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689) stabilized relations with Tsarist Russia.

However, during the 18th century European empires gradually expanded across the world, as European states developed economies built on maritime trade, colonial extraction, and advances in technology. The dynasty was confronted with newly developing concepts of the international system and state-to-state relations. European trading posts expanded into territorial control in nearby India and on the islands that are now Indonesia. The Qing response, successful for a time, was to establish the Canton System in 1756, which restricted maritime trade to that city (modern-day Guangzhou) and gave monopoly trading rights to private Chinese merchants. The British East India Company and the Dutch East India Company had long before been granted similar monopoly rights by their governments.

In 1793, the British East India Company, with the support of the British government, sent a diplomatic mission to China led by Lord George Macartney in order to open trade and put relations on a basis of equality. The imperial court viewed trade as of secondary interest, whereas the British saw maritime trade as the key to their economy. The Qianlong Emperor told Macartney "the kings of the myriad nations come by land and sea with all sorts of precious things", and "consequently there is nothing we lack..."[64]

Since China had little demand for European goods, Europe paid in silver for Chinese goods such as silk, tea, and ceramics, an imbalance that worried the mercantilist governments of Britain and France. The growing Chinese demand for opium provided the remedy. The British East India Company greatly expanded its production in Bengal. The Daoguang Emperor, concerned both over the outflow of silver and the damage that opium smoking was causing to his subjects, ordered Lin Zexu to end the opium trade. Lin confiscated the stocks of opium without compensation in 1839, leading Britain to send a military expedition the following year.

The First Opium War revealed the outdated state of the Chinese military. The Qing navy, composed entirely of wooden sailing junks, was severely outclassed by the modern tactics and firepower of the British Royal Navy. British soldiers, using advanced muskets and artillery, easily outmaneuvered and outgunned Qing forces in ground battles. The Qing surrender in 1842 marked a decisive, humiliating blow. The Treaty of Nanjing, the first of the "unequal treaties", demanded war reparations, forced China to open up the Treaty Ports of Canton, Amoy, Fuchow, Ningpo and Shanghai to Western trade and missionaries, and to cede Hong Kong Island to Britain. It revealed weaknesses in the Qing government and provoked rebellions against the regime.

The Taiping Rebellion in the mid-19th century was the first major instance of anti-Manchu sentiment. The rebellion began under the leadership of Hong Xiuquan (1814–64), a disappointed civil service examination candidate who, influenced by Christian teachings, had a series of visions and believed himself to be the son of God, the younger brother of Jesus Christ, sent to reform China. A friend of Hong's, Feng Yunshan, utilized Hong's ideas to organize a new religious group, the God Worshippers’ Society (Bai Shangdi Hui), which he formed among the impoverished peasants of Guangxi province.[65] Amid widespread social unrest and worsening famine, the rebellion not only posed the most serious threat towards Qing rulers, it has also been called the "bloodiest civil war of all time"; during its fourteen-year course from 1850 to 1864 between 20 and 30 million people died.[66] Hong Xiuquan, a failed civil service candidate, in 1851 launched an uprising in Guizhou province, and established the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom with Hong himself as king. Hong announced that he had visions of God and that he was the brother of Jesus Christ. Slavery, concubinage, arranged marriage, opium smoking, footbinding, judicial torture, and the worship of idols were all banned. However, success led to internal feuds, defections and corruption. In addition, British and French troops, equipped with modern weapons, had come to the assistance of the Qing imperial army. It was not until 1864 that Qing armies under Zeng Guofan succeeded in crushing the revolt. After the outbreak of this rebellion, there were also revolts by the Muslims and Miao people of China against the Qing dynasty, most notably in the Miao Rebellion (1854–1873) in Guizhou, the Panthay Rebellion (1856–1873) in Yunnan and the Dungan Revolt (1862–77) in the northwest.

The Western powers, largely unsatisfied with the Treaty of Nanjing, gave grudging support to the Qing government during the Taiping and Nian Rebellions. China's income fell sharply during the wars as vast areas of farmland were destroyed, millions of lives were lost, and countless armies were raised and equipped to fight the rebels. In 1854, Britain tried to re-negotiate the Treaty of Nanjing, inserting clauses allowing British commercial access to Chinese rivers and the creation of a permanent British embassy at Beijing.

In 1856, Qing authorities, in searching for a pirate, boarded a ship, the Arrow, which the British claimed had been flying the British flag, an incident which led to the Second Opium War. In 1858, facing no other options, the Xianfeng Emperor agreed to the Treaty of Tientsin, which contained clauses deeply insulting to the Chinese, such as a demand that all official Chinese documents be written in English and a proviso granting British warships unlimited access to all navigable Chinese rivers.

Ratification of the treaty in the following year led to a resumption of hostilities. In 1860, with Anglo-French forces marching on Beijing, the emperor and his court fled the capital for the imperial hunting lodge at Rehe. Once in Beijing, the Anglo-French forces looted and burned the Old Summer Palace and, in an act of revenge for the arrest, torture, and execution of the English diplomatic mission.[67] Prince Gong, a younger half-brother of the emperor, who had been left as his brother's proxy in the capital, was forced to sign the Convention of Beijing. The humiliated emperor died the following year at Rehe.

Self-strengthening and the frustration of reforms

Yet the dynasty rallied. Chinese generals and officials such as Zuo Zongtang led the suppression of rebellions and stood behind the Manchus. When the Tongzhi Emperor came to the throne at the age of five in 1861, these officials rallied around him in what was called the Tongzhi Restoration. Their aim was to adopt Western military technology in order to preserve Confucian values. Zeng Guofan, in alliance with Prince Gong, sponsored the rise of younger officials such as Li Hongzhang, who put the dynasty back on its feet financially and instituted the Self-Strengthening Movement. The reformers then proceeded with institutional reforms, including China's first unified ministry of foreign affairs, the Zongli Yamen; allowing foreign diplomats to reside in the capital; establishment of the Imperial Maritime Customs Service; the formation of modernized armies, such as the Beiyang Army, as well as a navy; and the purchase from Europeans of armament factories.[68]

The dynasty lost control of peripheral territories bit by bit. In return for promises of support against the British and the French, the Russian Empire took large chunks of territory in the Northeast in 1860. The period of cooperation between the reformers and the European powers ended with the Tientsin Massacre of 1870, which was incited by the murder of French nuns set off by the belligerence of local French diplomats. Starting with the Cochinchina Campaign in 1858, France expanded control of Indochina. By 1883, France was in full control of the region and had reached the Chinese border. The Sino-French War began with a surprise attack by the French on the Chinese southern fleet at Fuzhou. After that the Chinese declared war on the French. A French invasion of Taiwan was halted and the French were defeated on land in Tonkin at the Battle of Bang Bo. However Japan threatened to enter the war against China due to the Gapsin Coup and China chose to end the war with negotiations. The war ended in 1885 with the Treaty of Tientsin (1885) and the Chinese recognition of the French protectorate in Vietnam.[69]

In 1884, pro-Japanese Koreans in Seoul led the Gapsin Coup. Tensions between China and Japan rose after China intervened to suppress the uprising. Japanese Prime Minister Itō Hirobumi and Li Hongzhang signed the Convention of Tientsin, an agreement to withdraw troops simultaneously, but the First Sino-Japanese War of 1895 was a military humiliation. The Treaty of Shimonoseki recognized Korean independence and ceded Taiwan and the Pescadores to Japan. The terms might have been harsher, but when a Japanese citizen attacked and wounded Li Hongzhang, an international outcry shamed the Japanese into revising them. The original agreement stipulated the cession of Liaodong Peninsula to Japan, but Russia, with its own designs on the territory, along with Germany and France, in the Triple Intervention, successfully put pressure on the Japanese to abandon the peninsula.

These years saw an evolution in the participation of Empress Dowager Cixi (Wade–Giles: Tz'u-Hsi) in state affairs. She entered the imperial palace in the 1850s as a concubine to the Xianfeng Emperor (r. 1850–1861) and came to power in 1861 after her five-year-old son, the Tongzhi Emperor ascended the throne. She, the Empress Dowager Ci'an (who had been Xianfeng's empress), and Prince Gong (a son of the Daoguang Emperor), staged a coup that ousted several regents for the boy emperor. Between 1861 and 1873, she and Ci'an served as regents, choosing the reign title "Tongzhi" (ruling together). Following the emperor's death in 1875, Cixi's nephew, the Guangxu Emperor, took the throne, in violation of the dynastic custom that the new emperor be of the next generation, and another regency began. In the spring of 1881, Ci'an suddenly died, aged only forty-three, leaving Cixi as sole regent.[70]

From 1889, when Guangxu began to rule in his own right, to 1898, the Empress Dowager lived in semi-retirement, spending the majority of the year at the Summer Palace. On 1 November 1897, two German Roman Catholic missionaries were murdered in the southern part of Shandong province (the Juye Incident). Germany used the murders as a pretext for a naval occupation of Jiaozhou Bay. The occupation prompted a "scramble for concessions" in 1898, which included the German lease of Jiazhou Bay, the Russian acquisition of Liaodong, and the British lease of the New Territories of Hong Kong.

In the wake of these external defeats, the Guangxu Emperor initiated the Hundred Days' Reform of 1898. Newer, more radical advisers such as Kang Youwei were given positions of influence. The emperor issued a series of edicts and plans were made to reorganize the bureaucracy, restructure the school system, and appoint new officials. Opposition from the bureaucracy was immediate and intense. Although she had been involved in the initial reforms, the Empress Dowager stepped in to call them off, arrested and executed several reformers, and took over day-to-day control of policy. Yet many of the plans stayed in place, and the goals of reform were implanted.[71]

Drought in North China, combined with the imperialist designs of European powers and the instability of the Qing government, created background conditions for the Boxers. In 1900, local groups of Boxers proclaiming support for the Qing dynasty murdered foreign missionaries and large numbers of Chinese Christians, then converged on Beijing to besiege the Foreign Legation Quarter. A coalition of European, Japanese, and Russian armies (the Eight-Nation Alliance) then entered China without diplomatic notice, much less permission. Cixi declared war on all of these nations, only to lose control of Beijing after a short, but hard-fought campaign. She fled to Xi'an. The victorious allies then enforced their demands on the Qing government, including compensation for their expenses in invading China and execution of complicit officials, via the Boxer Protocol.[72]

Reform, revolution, collapse

The defeat by Japan in 1895 created a sense of crisis which the failure of the 1898 reforms and the disasters of 1900 only exacerbated. Cixi in 1901 moved to mollify the foreign community, called for reform proposals, and initiated a set of "New Policies", also known as the "Late Qing Reform". Over the next few years the reforms included the restructuring of the national education, judicial, and fiscal systems, the most dramatic of which was the abolition of the imperial examinations in 1905. [73] The court directed a constitution to be drafted, and provincial elections were held, the first in China's history.[74] Sun Yat-sen and revolutionaries debated reform officials and constitutional monarchists such as Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao over how to transform the Manchu Empire into a modern Han Chinese nation.[75]

The Guangxu Emperor died on 14 November 1908 and Cixi died the following day. Rumors held that she or Yuan Shikai ordered trusted eunuchs to poison the Guangxu Emperor, and an autopsy conducted nearly a century later confirmed lethal levels of arsenic in his corpse.[76] Puyi, the oldest son of Zaifeng, Prince Chun, and nephew to the childless Guangxu Emperor, was appointed successor at the age of two, leaving Zaifeng with the regency. Zaifeng forced Yuan Shikai to resign. In April 1911 Zaifeng created a cabinet known as "The Royal Cabinet" because among the thirteen cabinet members, five were members of the imperial family or Aisin-Gioro relatives.[77]

The Wuchang Uprising of 10 October 1911 set off a series of uprisings. By November, 14 of the 15 provinces had rejected Qing rule. This led to the creation of the Republic of China, in Nanjing on 1 January 1912, with Sun Yat-sen as its provisional head. Seeing a desperate situation, the Qing court brought Yuan Shikai back to power. His Beiyang Army crushed the revolutionaries in Wuhan at the Battle of Yangxia. After taking the position of Prime Minister he created his own cabinet, with the support of Empress Dowager Longyu. However, Yuan Shikai decided to cooperate with Sun Yat-sen's revolutionaries to overthrow the Qing dynasty.

On 12 February 1912, Longyu issued the abdication of the child emperor Puyi leading to the fall of the Qing dynasty under the pressure of Yuan Shikai's Beiyang army despite objections from conservatives and royalist reformers.[78] This brought an end to over 2,000 years of Imperial China and nearly 268 years of ruling China by the Manchu people, and began a period of instability. In July 1917, there was an abortive attempt to restore the Qing dynasty led by Zhang Xun. Puyi was allowed to live in the Forbidden City after his abdication until 1924, when he moved to the Japanese concession in Tianjin. The Empire of Japan invaded Northeast China and founded Manchukuo there in 1932, with Puyi as its emperor. After the invasion of Northeast China to fight Japan by the Soviet Union, Manchukuo fell in 1945.

Government

%252C_Qing_Dynasty_postage_stamp.gif)

The early Qing emperors adopted the bureaucratic structures and institutions from the preceding Ming dynasty but split rule between Han Chinese and Manchus, with some positions also given to Mongols.[79] Like previous dynasties, the Qing recruited officials via the imperial examination system, until the system was abolished in 1905. The Qing divided the positions into civil and military positions, each having nine grades or ranks, each subdivided into a and b categories. Civil appointments ranged from an attendant to the emperor or a Grand Secretary in the Forbidden City (highest) to being a prefectural tax collector, deputy jail warden, deputy police commissioner, or tax examiner. Military appointments ranged from being a field marshal or chamberlain of the imperial bodyguard to a third class sergeant, corporal or a first or second class private.[80]

Central government agencies

The formal structure of the Qing government centered on the Emperor as the absolute ruler, who presided over six Boards (Ministries[lower-alpha 8]), each headed by two presidents[lower-alpha 9] and assisted by four vice presidents.[lower-alpha 10] In contrast to the Ming system, however, Qing ethnic policy dictated that appointments were split between Manchu noblemen and Han officials who had passed the highest levels of the state examinations. The Grand Secretariat,[lower-alpha 11] which had been an important policy-making body under the Ming, lost its importance during the Qing and evolved into an imperial chancery. The institutions which had been inherited from the Ming formed the core of the Qing "Outer Court", which handled routine matters and was located in the southern part of the Forbidden City.

In order not to let the routine administration take over the running of the empire, the Qing emperors made sure that all important matters were decided in the "Inner Court", which was dominated by the imperial family and Manchu nobility and which was located in the northern part of the Forbidden City. The core institution of the inner court was the Grand Council.[lower-alpha 12] It emerged in the 1720s under the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor as a body charged with handling Qing military campaigns against the Mongols, but soon took over other military and administrative duties, centralizing authority under the crown.[81] The Grand Councillors[lower-alpha 13] served as a sort of privy council to the emperor.

From the early Qing, the central government was characterized by a system of dual appointments by which each position in the central government had a Manchu and a Han Chinese assigned to it. The Han Chinese appointee was required to do the substantive work and the Manchu to ensure Han loyalty to Qing rule.[82]

There was also another government institution called Imperial Household Department which was unique to the Qing dynasty. It was established before the fall of the Ming, but it became mature only after 1661, following the death of the Shunzhi Emperor and the accession of his son, the Kangxi Emperor.[83] The department's original purpose was to manage the internal affairs of the imperial family and the activities of the inner palace (in which tasks it largely replaced eunuchs), but it also played an important role in Qing relations with Tibet and Mongolia, engaged in trading activities (jade, ginseng, salt, furs, etc.), managed textile factories in the Jiangnan region, and even published books.[84] Relations with the Salt Superintendents and salt merchants, such as those at Yangzhou, were particularly lucrative, especially since they were direct, and did not go through absorptive layers of bureaucracy. The department was manned by booi,[lower-alpha 14] or "bondservants," from the Upper Three Banners.[85] By the 19th century, it managed the activities of at least 56 subagencies.[83][86]

Administrative divisions

.jpg.webp)

Qing China reached its largest extent during the 18th century, when it ruled China proper (eighteen provinces) as well as the areas of present-day Northeast China, Inner Mongolia, Outer Mongolia, Xinjiang and Tibet, at approximately 13 million km2 in size. There were originally 18 provinces, all of which in China proper, but later this number was increased to 22, with Manchuria and Xinjiang being divided or turned into provinces. Taiwan, originally part of Fujian province, became a province of its own in the 19th century,[87] but was ceded to the Empire of Japan following the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895.[88]

Territorial administration

The Qing organization of provinces was based on the fifteen administrative units set up by the Ming dynasty, later made into eighteen provinces by splitting for example, Huguang into Hubei and Hunan provinces. The provincial bureaucracy continued the Yuan and Ming practice of three parallel lines, civil, military, and censorate, or surveillance. Each province was administered by a governor (巡撫, xunfu) and a provincial military commander (提督, tidu). Below the province were prefectures (府, fu) operating under a prefect (知府, zhīfǔ), followed by subprefectures under a subprefect. The lowest unit was the county, overseen by a county magistrate. The eighteen provinces are also known as "China proper". The position of viceroy or governor-general (總督, zongdu) was the highest rank in the provincial administration. There were eight regional viceroys in China proper, each usually took charge of two or three provinces. The Viceroy of Zhili, who was responsible for the area surrounding the capital Beijing, is usually considered as the most honorable and powerful viceroy among the eight.

By the mid-18th century, the Qing had successfully put outer regions such as Inner and Outer Mongolia, Tibet and Xinjiang under its control. Imperial commissioners and garrisons were sent to Mongolia and Tibet to oversee their affairs. These territories were also under supervision of a central government institution called Lifan Yuan. Qinghai was also put under direct control of the Qing court. Xinjiang, also known as Chinese Turkestan, was subdivided into the regions north and south of the Tian Shan mountains, also known today as Dzungaria and Tarim Basin respectively, but the post of Ili General was established in 1762 to exercise unified military and administrative jurisdiction over both regions. Dzungaria was fully opened to Han migration by the Qianlong Emperor from the beginning. Han migrants were at first forbidden from permanently settling in the Tarim Basin but were the ban was lifted after the invasion by Jahangir Khoja in the 1820s. Likewise, Manchuria was also governed by military generals until its division into provinces, though some areas of Xinjiang and Northeast China were lost to the Russian Empire in the mid-19th century. Manchuria was originally separated from China proper by the Inner Willow Palisade, a ditch and embankment planted with willows intended to restrict the movement of the Han Chinese, as the area was off-limits to civilian Han Chinese until the government started colonizing the area, especially since the 1860s.

With respect to these outer regions, the Qing maintained imperial control, with the emperor acting as Mongol khan, patron of Tibetan Buddhism and protector of Muslims. However, Qing policy changed with the establishment of Xinjiang province in 1884. During The Great Game era, taking advantage of the Dungan revolt in northwest China, Yaqub Beg invaded Xinjiang from Central Asia with support from the British Empire, and made himself the ruler of the kingdom of Kashgaria. The Qing court sent forces to defeat Yaqub Beg and Xinjiang was reconquered, and then the political system of China proper was formally applied onto Xinjiang. The Kumul Khanate, which was incorporated into the Qing empire as a vassal after helping Qing defeat the Zunghars in 1757, maintained its status after Xinjiang turned into a province through the end of the dynasty in the Xinhai Revolution up until 1930.[89] In the early 20th century, Britain sent an expedition force to Tibet and forced Tibetans to sign a treaty. The Qing court responded by asserting Chinese sovereignty over Tibet,[90] resulting in the 1906 Anglo-Chinese Convention signed between Britain and China. The British agreed not to annex Tibetan territory or to interfere in the administration of Tibet, while China engaged not to permit any other foreign state to interfere with the territory or internal administration of Tibet.[91] Furthermore, similar to Xinjiang which was converted into a province earlier, the Qing government also turned Manchuria into three provinces in the early 20th century, officially known as the "Three Northeast Provinces", and established the post of Viceroy of the Three Northeast Provinces to oversee these provinces, making the total number of regional viceroys to nine.

Society

Population growth and mobility

The population grew in numbers, density, and mobility. The population grew from roughly 150 million in 1700, about what it had been a century before, then doubled over the next century, and reached a height of 450 million on the eve of the Taiping Rebellion in 1850.[92] The spread of New World crops, such as maize, peanuts, sweet potatoes, and potatoes decreased the number of deaths from malnutrition. Diseases such as smallpox were brought under control by an increase in inoculations. In addition, infant deaths were decreased due to improvements in birthing techniques performed by doctors and midwives and an increase in medical books available to the public.[93] Government campaigns decreased the incidence of infanticide. In Europe population growth in this period was greatest in the cities, but in China growth in cities and the lower Yangzi was low. The greatest growth was in the borderlands and the highlands, where farmers could clear large tracts of marshlands and forests.[94]

The population was also remarkably mobile, perhaps more so than at any time in Chinese history. Indeed, the Qing government did far more to encourage mobility than to discourage it. Millions of Han Chinese migrated to Yunnan and Guizhou in the 18th century, and also to Taiwan. After the conquests of the 1750s and 1760s, the court organized agricultural colonies in Xinjiang. Migration might be permanent, for resettlement, or the migrants (in theory at least) might regard the move as a temporary sojourn. The latter included an increasingly large and mobile workforce. Local-origin-based merchant groups also moved freely. This mobility also included the organized movement of Qing subjects overseas, largely to Southeastern Asia, to pursue trade and other economic opportunities.[94]

Manchuria, however, was formally closed to Han settlement by the Willow Palisade, with the exception of some bannermen.[95] Nonetheless, by 1780, Han Chinese had become 80% of the population.[96] The relatively low populated territory was vulnerable as the Russian Empire demanded the Amur Annexation annexing Outer Manchuria. In response, the Qing officials such as Tepuqin (特普欽), the Military Governor of Heilongjiang in 1859–1867, made proposals (1860) to open parts of Guandong for Chinese civilian farmer settlers in order to oppose further possible annexations.[97] In the later 19th century, Manchuria was opened up for Han settlers leading to a more extensive migration,[98] which was called Chuang Guandong (simplified Chinese: 闯关东; traditional Chinese: 闖關東) literally "Crashing into Guandong" with Guandong being an older name for Manchuria.[99] At the end of the 19th century and turn of the 20th century, to counteract increasing Russian influence, the Qing Dynasty abolished the existing administrative system in Manchuria (created by the bannermen) and reclassified all immigrants to the region as Han (Chinese) instead of minren (民人, civilians, non-bannermen), while replacing provincial generals with provincial governors. This reform occurred when Inner Manchuria was a battleground between Russia and Japan. From 1902-1911, seventy civil administrations were created due to the increasing population of Manchuria.[100]

Statuses in society

According to statute, Qing society was divided into relatively closed estates, of which in most general terms there were five. Apart from the estates of the officials, the comparatively minuscule aristocracy, and the degree-holding literati, there also existed a major division among ordinary Chinese between commoners and people with inferior status.[101] They were divided into two categories: one of them, the good "commoner" people, the other "mean" people who were seen as debased and servile. The majority of the population belonged to the first category and were described as liangmin, a legal term meaning good people, as opposed to jianmin meaning the mean (or ignoble) people. Qing law explicitly stated that the traditional four occupational groups of scholars, farmers, artisans and merchants were "good", or having a status of commoners. On the other hand, slaves or bondservants, entertainers (including prostitutes and actors), tattooed criminals, and those low-level employees of government officials were the "mean people". Mean people were legally inferior to commoners and suffered unequal treatments, such as being forbidden to take the imperial examination.[102] Furthermore, such people were usually not allowed to marry with free commoners and were even often required to acknowledge their abasement in society through actions such as bowing. However, throughout the Qing dynasty, the emperor and his court, as well as the bureaucracy, worked towards reducing the distinctions between the debased and free but did not completely succeed even at the end of its era in merging the two classifications together.[103]

Qing gentry

Although there had been no powerful hereditary aristocracy since the Song dynasty, the gentry (shenshi), like their British counterparts, enjoyed imperial privileges and managed local affairs. The status of this scholar-official was defined by passing at least the first level of civil service examinations and holding a degree, which qualified him to hold imperial office, although he might not actually do so. The gentry member could legally wear gentry robes and could talk to officials as equals. Officials who had served for one or two terms could retire to enjoy the glory of their status. Informally, the gentry then presided over local society and could use their connections to influence the magistrate, acquire land, and maintain large households. The gentry thus included not only males holding degrees but also their wives, descendants, some of their relatives.[104]

The gentry class was divided into groups. Not all who held office were literati, as merchant families could purchase degrees, and not all who passed the exams found employment as officials, since the number of degree-holders was greater than the number of openings. The gentry class also differed in the source and amount of their income. Literati families drew income from landholding, as well as from lending money. Officials, of course, drew a salary, which, as the years went by, were less and less adequate, leading to widespread reliance on "squeeze," irrgular payments. Those who prepared for but failed the exams, like those who passed but were not appointed to office, could become tutors or teachers, private secretaries to sitting officials, administrators of guilds or temples, or other positions that required literacy. Others turned to fields such as engineering, medicine, or law, which by the nineteenth century demanded specialized learning. By the nineteenth century, it was no longer shameful to become an author or publisher of fiction. [105]

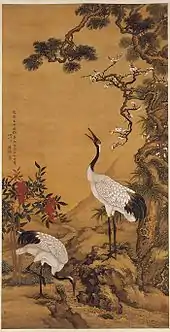

The Qing gentry were marked as much by their aspiration to a cultured lifestyle as by their legal status. They lived more refined and comfortable lives than the commoners and used sedan-chairs to travel any significant distance. They often showed off their learning by collecting objects such as scholars' stones, porcelain or pieces of art for their beauty, which set them off from less cultivated commoners.[106]

Family and kinship

By the Qing, the building block of society was patrilineal kinship, that is, the local family lineage with descent through the male line, often translated as "clan". A shift in marital practices, identity and loyalty had begun during the Song dynasty when the civil service examination began to replace nobility and inheritance as a means for gaining status. Instead of intermarrying within aristocratic elites of the same social status, they tended to form marital alliances with nearby families of the same or higher wealth, and established the local people's interests as first and foremost which helped to form intermarried townships. [107] The Neo-Confucian ideology, especially the Cheng-Zhu thinking favored by Qing social thought, emphasised patrilineal families and genealogy in society.[108]

The emperors and local officials exhorted families to compile genealogies in order to stabilize local society.[109] The genealogy was placed in the ancestral hall, which served as the lineage's headquarters and a place for annual ancestral sacrifice.The genealogy recorded the lineage's history, biographies of respected ancestors, a chart of all the family members of each generation, rules for the members to follow, and often copies of title contracts for collective property as well. A specific Chinese character appeared in the given name of each male of each generation, often well into the future. These lineages claimed to be based on biological descent but when a member of a lineage gained office or became wealthy, he might use considerable creativity in selecting a prestigious figure to be "founding ancestor". [110] Such worship was intended to ensure that the ancestors remain content and benevolent spirits (shen) who would keep watch over and protect the family. Later observers felt that the ancestral cult focused on the family and lineage, rather than on more public matters such as community and nation.[111]

Inner Mongols and Khalkha Mongols in the Qing rarely knew their ancestors beyond four generations and Mongol tribal society was not organized among patrilineal clans, contrary to what was commonly thought, but included unrelated people at the base unit of organization.[112] The Qing tried but failed to promote the Chinese Neo-Confucian ideology of organizing society along patrimonial clans among the Mongols.[113]

Religion

Manchu rulers presided over a multi-ethnic empire and the emperor, who was held responsible for “All Under Heaven” or Tian Xia, patronized and took responsibility for all religions and belief systems. The empire's “spiritual center of gravity" was the "religio-political state." [114] Since the empire was part of the order of the cosmos, which conferred the Mandate of Heaven, the Emperor as “Son of Heaven” was both the head of the political system and the head priest of the State Cult. He united political and spiritual roles that in medieval Europe were separated into the roles of emperor and pope and performed the imperial rites that ensured political order, prosperity, and social morality. The emperor and his officials, who were his personal representatives, took responsibility over all aspects of the empire, especially spiritual life and religious institutions and practices.[115] The county magistrate, as the emperor's political and spiritual representative, made offerings at officially recognized temples, for instance those dedicated to the God of Walls and Moats, (the so-called “City God), and local deified heroes. The magistrate lectured on the Emperor's Sacred Edict to promote civic morality; he kept close watch over religious organizations whose actions might threaten the sovereignty and religious prerogative of the state.[116]

Manchu and imperial religion

The Manchu imperial family were especially attracted by Yellow Sect or Gelug Buddhism that had spread from Tibet into Mongolia. The Fifth Dalai Lama, who had gained power in 1642, just before the Manchus took Beijing, looked to the Qing court for support. The Kangxi and Qianlong emperors practiced this form of Tibetan Buddhism as one of their household religions and built temples that made Beijing one of its centers, and constructed a replica Lhasa's Potala Palace at their summer retreat in Rehe.[117]

Shamanism, the most common religion among Manchus, was a spiritual inheritance from their Tungusic ancestors that set them off from Han Chinese. [118] State shamanism was important to the imperial family both to maintain their Manchu cultural identity and to promote their imperial legitimacy among tribes in the northeast. [119] Imperial obligations included rituals on the first day of Chinese New Year at a shamanic shrine (tangse). [120] Practices in Manchu families included sacrifices to the ancestors, and the use of shamans, often women, who went into a trance to seek healing or exorcism [121]

Popular religion

The belief system most widely practiced among Han Chinese is often called local, popular, or folk religion, and was centered around the patriarchal family, the maintenance of the male family line, and shen, or spirits. Common practices included ancestor veneration, filial piety, local gods and spirits. Rites included mourning, funeral, burial, practices.[122] Since they did not require exclusive allegiance, forms and branches of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism were intertwined, for instance in the syncretic Three teachings.[123] Chinese folk religion combined elements of the three, with local variations [124] County magistrates, who were graded and promoted on their ability to maintain local order, tolerated local sects and even patronized local temples as long as they were orderly, but were suspicious of heterodox sects that defied state authority and rejected imperial doctrines. Some of these sects indeed had long histories of rebellion, such as the Way of Former Heaven, which drew on Daoism, and the White Lotus society, which drew on millennial Buddhism. The White Lotus Rebellion (1796–1804) confirmed official suspicions as did the Taiping Rebellion, which drew on millennial Christianity.

Christianity, Judaism, and Islam

The Abrahamic religions had arrived from Western Asia as early as the Tang dynasty but their insistence that they should be practiced to the exclusion of other religions made them less adaptable than Buddhism, which had quickly been accepted as native. Islam predominated in Central Asian areas of the empire, while Judaism and Christianity were practiced in well-established but self-contained communities.[125]

Several hundred Catholic missionaries arrived from the late Ming period until the proscription of Christianity in 1724. The Jesuits adapted to Chinese expectations, evangelized from the top down, adopted the robes and lifestyles of literati, becoming proficient in the Confucian classics, and did not challenge Chinese moral values, such as ancestor veneration. They proved their value to the early Manchu emperors with their work in gunnery, cartography, and astronomy, but fell out of favor for a time until the Kangxi Emperor's 1692 edict of toleration.[126] In the countryside, the newly arrived Dominican and Franciscan clerics established rural communities that adapted to local folk religious practices by emphasizing healing, festivals, and holy days rather than sacraments and doctrine. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, a spectrum of Christian believers had established communities.[127] In 1724, the Yongzheng Emperor (1678–1735) announced that Christianity was a "heterodox teaching" and hence proscribed.[128] Since the European Catholic missionaries kept control in their own hands and had not allowed the creation of a native clergy, however, the number of Catholics would grow more rapidly after 1724 and local communities could set their own rules and standards. In 1811, Christian religious activities were further criminalized by the Jiaqing Emperor (1760–1820).[129] The imperial ban was lifted by Treaty in 1846.[130]

The first Protestant missionary to China was Robert Morrison (1782–1834) of the London Missionary Society (LMS),[131] who arrived at Canton on September 6, 1807. He completed a translation of the entire Bible in 1819.[132] Liang Afa (1789–1855), a Morrison-trained Chinese convert, branched out the evangelization mission in inner China.[133][134] The two Opium Wars (1839–1860) marked the watershed of Protestant Christian missions.[128] The 1842 Treaty of Nanjing,[135] the American treaty and the French treaty signed in 1844,[136] and the 1858 Treaty of Tianjin,[128] distinguished Christianity from the local religions and granted it protected status.[137] Chinese popular cults, such as the White Lotus and the Eight Trigram, presented themselves as Christian to share this protection.[138]

In the late 1840s Hong Xiuquan read Morrison's Chinese Bible, as well as Liang Afa's evangelistic pamphlet, and announced to his followers that Christianity in fact had been the religion of ancient China before Confucius and his followers drove it out.[139] He formed the Taiping Movement, which emerged in South China as a "collusion of the Chinese tradition of millenarian rebellion and Christian messianism", "apocalyptic revolution, Christianity, and 'communist utopianism'".[140]

After 1860, enforcement of the treaties allowed missionaries to spread their evangelization efforts outside Treaty Ports. Their presence created cultural and political opposition. Historian John K. Fairbank observed that "[t]o the scholar-gentry, Christian missionaries were foreign subversives, whose immoral conduct and teaching were backed by gunboats".[141] In the next decades, there were 800 some conflicts between village Christians and non-Christians (jiao'an) mostly about non-religious issues, such as land rights or local taxes, but religious conflict often behind such cases.[142] In the summer of 1900, as foreign powers contemplated the division of China, village youths, known as Boxers, who practiced Chinese martial arts and spiritual practices, reacted against Western power and churches, attacked and murdered Chinese Christians and foreign missionaries in the Boxer Uprising. The imperialist powers once again invaded and imposed a substantial indemnity. The Beijing government reacted by implementing substantial fiscal and administrative reforms but this defeat convinced many among the educated elites that popular religion was an obstacle to China's development as a modern nation, and some turned to Christianity as a spiritual tool to build one.[143]

By 1900, there were about 1,400 Catholic priests and nuns in China serving nearly 1 million Catholics. Over 3,000 Protestant missionaries were active among the 250,000 Protestant Christians in China.[144] Western medical missionaries established clinics and hospitals, and led medical training in China.[145] Missionaries began establishing nurse training schools in the late 1880s, but nursing of sick men by women was rejected by local tradition, so the number of students was small until the 1930s.[146]

Economy

_1850%E2%80%931861_Qing_Dynasty_cash_coin.png.webp)

By the end of the 17th century, the Chinese economy had recovered from the devastation caused by the wars in which the Ming dynasty were overthrown, and the resulting breakdown of order.[147] In the following century, markets continued to expand as in the late Ming period, but with more trade between regions, a greater dependence on overseas markets and a greatly increased population.[148] By the end of the 18th century the population had risen to 300 million from approximately 150 million during the late Ming dynasty. The dramatic rise in population was due to several reasons, including the long period of peace and stability in the 18th century and the import of new crops China received from the Americas, including peanuts, sweet potatoes and maize. New species of rice from Southeast Asia led to a huge increase in production. Merchant guilds proliferated in all of the growing Chinese cities and often acquired great social and even political influence. Rich merchants with official connections built up huge fortunes and patronized literature, theater and the arts. Textile and handicraft production boomed.[149]

The government broadened land ownership by returning land that had been sold to large landowners in the late Ming period by families unable to pay the land tax.[150] To give people more incentives to participate in the market, they reduced the tax burden in comparison with the late Ming, and replaced the corvée system with a head tax used to hire laborers.[151] The administration of the Grand Canal was made more efficient, and transport opened to private merchants.[152] A system of monitoring grain prices eliminated severe shortages, and enabled the price of rice to rise slowly and smoothly through the 18th century.[153] Wary of the power of wealthy merchants, Qing rulers limited their trading licenses and usually refused them permission to open new mines, except in poor areas.[154] These restrictions on domestic resource exploration, as well as on foreign trade, are held by some scholars as a cause of the Great Divergence, by which the Western world overtook China economically.