Charles I of Hungary

Charles I, also known as Charles Robert (Hungarian: Károly Róbert; Croatian: Karlo Robert; Slovak: Karol Róbert; 1288 – 16 July 1342) was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1308 to his death. He was a member of the Capetian House of Anjou and the only son of Charles Martel, Prince of Salerno. His father was the eldest son of Charles II of Naples and Mary of Hungary. Mary laid claim to Hungary after her brother, Ladislaus IV of Hungary, died in 1290, but the Hungarian prelates and lords elected her cousin, Andrew III, king. Instead of abandoning her claim to Hungary, she transferred it to her son, Charles Martel, and after his death in 1295, to her grandson, Charles. On the other hand, her husband, Charles II of Naples, made their third son, Robert, heir to the Kingdom of Naples, thus disinheriting Charles.

| Charles I | |

|---|---|

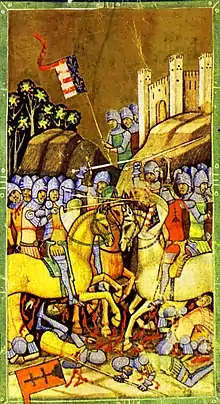

Charles depicted in the Illuminated Chronicle | |

| King of Hungary and Croatia contested by Wenceslaus (1301–05) and by Otto (1305–12) | |

| Reign | 1301/08 – 1342 |

| Coronation | early 1301 15/16 June 1309 27 August 1310 |

| Predecessor | Andrew III or Otto |

| Successor | Louis I |

| Born | 1288 |

| Died | 16 July 1342 (aged 53–54) Visegrád |

| Burial | Székesfehérvár Basilica |

| Spouse | Maria of Galicia (disputed) Mary of Bytom Beatrice of Luxembourg Elisabeth of Poland |

| Issue more... | Catherine, Duchess of Świdnica Louis I, King of Hungary Andrew, Duke of Calabria Stephen, Duke of Slavonia |

| Dynasty | Capetian House of Anjou |

| Father | Charles Martel of Anjou |

| Mother | Clemence of Austria |

| Religion | Catholicism |

Charles came to the Kingdom of Hungary upon the invitation of an influential Croatian lord, Paul Šubić, in August 1300. Andrew III died on 14 January 1301, and within four months Charles was crowned king, but with a provisional crown instead of the Holy Crown of Hungary. Most Hungarian noblemen refused to yield to him and elected Wenceslaus of Bohemia king. Charles withdrew to the southern regions of the kingdom. Pope Boniface VIII acknowledged Charles as the lawful king in 1303, but Charles was unable to strengthen his position against his opponent. Wenceslaus abdicated in favor of Otto of Bavaria in 1305. Because it had no central government, the Kingdom of Hungary had disintegrated into a dozen provinces, each headed by a powerful nobleman, or oligarch. One of those oligarchs, Ladislaus III Kán, captured and imprisoned Otto of Bavaria in 1307. Charles was elected king in Pest on 27 November 1308, but his rule remained nominal in most parts of his kingdom even after he was crowned with the Holy Crown on 27 August 1310.

Charles won his first decisive victory in the Battle of Rozgony (at present-day Rozhanovce in Slovakia) on 15 June 1312. After that, his troops seized most fortresses of the powerful Aba family. During the next decade, Charles restored royal power primarily with the assistance of the prelates and lesser noblemen in most regions of the kingdom. After the death of the most powerful oligarch, Matthew Csák, in 1321, Charles became the undisputed ruler of the whole kingdom, with the exception of Croatia where local noblemen were able to preserve their autonomous status. He was not able to hinder the development of Wallachia into an independent principality after his defeat in the Battle of Posada in 1330. Charles's contemporaries described his defeat in that battle as a punishment from God for his cruel revenge against the family of Felician Záh who had attempted to slaughter the royal family.

Charles rarely made perpetual land grants, instead introduced a system of "office fiefs", whereby his officials enjoyed significant revenues, but only for the time they held a royal office, which ensured their loyalty. In the second half of his reign, Charles did not hold Diets and administered his kingdom with absolute power. He established the Order of Saint George, which was the first secular order of knights. He promoted the opening of new gold mines, which made Hungary the largest producer of gold in Europe. The first Hungarian gold coins were minted during his reign. At the congress of Visegrád in 1335, he mediated a reconciliation between two neighboring monarchs, John of Bohemia and Casimir III of Poland. Treaties signed at the same congress also contributed to the development of new commercial routes linking Hungary with Western Europe. Charles's efforts to reunite Hungary, together with his administrative and economic reforms, established the basis for the achievements of his successor, Louis the Great.

Early years

Childhood (1288–1300)

Charles was the only son of Charles Martel, Prince of Salerno, and his wife, Clemence of Austria.[1][2] He was born in 1288; the place of his birth is unknown.[1][2][3] Charles Martel was the firstborn son of Charles II of Naples and Charles II's wife, Mary, who was a daughter of Stephen V of Hungary.[4][5] After the death of her brother, Ladislaus IV of Hungary, in 1290, Queen Mary announced her claim to Hungary, stating that the House of Árpád (the royal family of Hungary) had become extinct with Ladislaus's death.[6] However, her father's cousin, Andrew also laid claim to the throne, although his father, Stephen the Posthumous, had been regarded a bastard by all other members of the royal family.[7] For all that, the Hungarian lords and prelates preferred Andrew against Mary and he was crowned king of Hungary on 23 July 1290.[6][8] She transferred her claim to Hungary to Charles Martel in January 1292.[9] The Babonići, Frankopans, Šubići and other Croatian and Slavonian noble families seemingly acknowledged Charles Martel's claim, but in fact their loyalty vacillated between Charles Martel and Andrew III.[10][11]

Charles Martel died in autumn 1295, and his seven-year-old son, Charles, inherited his claim to Hungary.[12][3] Charles would have also been the lawful heir to his grandfather, Charles II of Naples, in accordance with the principles of primogeniture.[12][13] However, Charles II, who preferred his third son, Robert, to his grandson, bestowed the rights of a firstborn son upon Robert on 13 February 1296.[14] Pope Boniface VIII confirmed Charles II's decision on 27 February 1296, excluding the child Charles from succeeding his grandfather in the Kingdom of Naples.[14] Dante Alighieri wrote of "the schemes and frauds that would attack"[15] Charles Martel's family in reference to Robert's alleged manoeuvres to acquire the right to inherit Naples.[16] The 14th-century historian Giovanni Villani also noted that his contemporaries were of the opinion that Robert's claim to Naples was weaker than his nephew's.[16] The jurist Baldus de Ubaldis refrained from setting out his position on the legitimacy of Robert's rule.[16]

Struggle for Hungary (1300–1308)

Andrew III of Hungary made his maternal uncle, Albertino Morosini, Duke of Slavonia, in July 1299, stirring up the Slavonian and Croatian noblemen to revolt.[17][18] A powerful Croatian baron, Paul Šubić, sent his brother, George, to Italy in early 1300 to convince Charles II of Naples to send his grandson to Hungary to claim the throne in person.[18] The king of Naples accepted the proposal and borrowed 1,300 ounces of gold from Florentine bankers to finance Charles's journey.[9][19] A Neapolitan knight of French origin, Philip Drugeth, accompanied the twelve-year-old Charles to Hungary.[20] They landed at Split in Dalmatia in August 1300.[9][21] From Split, Paul Šubić escorted him to Zagreb where Ugrin Csák swore loyalty to Charles.[22] Charles's opponent, Andrew III of Hungary, died on 14 January 1301.[23] Charles hurried to Esztergom where the Archbishop-elect, Gregory Bicskei, crowned him with a provisional crown before 13 May.[24][25] However, most Hungarians considered Charles's coronation unlawful because customary law required that it should have been performed with the Holy Crown of Hungary in Székesfehérvár.[24][22]

Charles counted his regnal years from this coronation, but Hungary had actually disintegrated into about a dozen independent provinces, each ruled by a powerful lord, or oligarch.[26][27][28] Among them, Matthew Csák dominated the northwestern parts of Hungary (which now form the western territories of present-day Slovakia), Amadeus Aba controlled the northeastern lands, Ivan Kőszegi ruled Transdanubia, and Ladislaus Kán governed Transylvania.[29] Most of those lords refused to accept Charles's rule and proposed the crown to Wenceslaus II of Bohemia's son and namesake, Wenceslaus, whose bride, Elisabeth, was Andrew III's only daughter.[5][30] Although Wenceslaus was crowned with the Holy Crown in Székesfehérvár, the legitimacy of his coronation was also questionable because John Hont-Pázmány, Archbishop of Kalocsa, put the crown on Wenceslaus's head, although customary law authorized the Archbishop of Esztergom to perform the ceremony.[25]

After Wenceslaus's coronation, Charles withdrew to Ugrin Csák's domains in the southern regions of the kingdom.[31] Pope Boniface sent his legate, Niccolo Boccasini, to Hungary.[31] Boccasini convinced the majority of the Hungarian prelates to accept Charles's reign.[31] However, most Hungarian lords continued to oppose Charles because, according to the Illuminated Chronicle,[32] they feared that "the free men of the kingdom should lose their freedom by accepting a king appointed by the Church".[33] Charles laid siege to Buda, the capital of the kingdom, in September 1302, but Ivan Kőszegi relieved the siege.[25] Charles's charters show that he primarily stayed in the southern parts of the kingdom during the next years although he also visited Amadeus Aba in the fortress of Gönc.[26]

Pope Boniface who regarded Hungary as a fief of the Holy See declared Charles the lawful king of Hungary on 31 May 1303.[34][35] He also threatened Wenceslaus with excommunication if he continued to style himself king of Hungary.[36] Wenceslaus, left Hungary in summer 1304, taking the Holy Crown with him.[31] Charles met his cousin, Rudolph III of Austria, in Pressburg (now Bratislava in Slovakia) on 24 August.[31][37] After signing an alliance, they jointly invaded Bohemia in the autumn.[31][38] Wenceslaus who had succeeded his father in Bohemia renounced his claim to Hungary in favor of Otto III, Duke of Bavaria on 9 October 1305.[39]

Otto was crowned with the Holy Crown in Székesfehérvár on 6 December 1305 by Benedict Rád, Bishop of Veszprém, and Anton, Bishop of Csanád.[39][40][38] He was never able to strengthen his position in Hungary, because only the Kőszegis and the Transylvanian Saxons supported him.[31] Charles seized Esztergom and many fortresses in the northern parts of Hungary (now in Slovakia) in 1306.[41][38] His partisans also occupied Buda in June 1307.[41] Ladislaus Kán, Voivode of Transylvania, seized and imprisoned Otto in Transylvania.[39][42] An assembly of Charles's partisans confirmed Charles's claim to the throne on 10 October, but three powerful lords—Matthew Csák, Ladislaus Kán, and Ivan Kőszegi—were absent from the meeting.[41][38] In 1308, Ladislaus Kán released Otto, who then left Hungary.[42] Otto never ceased styling himself King of Hungary, but he never returned to the country.[41]

Pope Clement V sent a new papal legate, Gentile Portino da Montefiore, to Hungary.[41][43] Montefiore arrived in the summer of 1308.[41] In the next few months, he persuaded the most powerful lords one by one to accept Charles's rule.[41] At the Diet, which was held in the Dominican monastery in Pest, Charles was unanimously proclaimed king on 27 November 1308.[43][44] The delegates sent by Matthew Csák and Ladislaus Kán were also present at the assembly.[44]

Reign

Wars against the oligarchs (1308–1323)

The papal legate convoked the synod of the Hungarian prelates, who declared the monarch inviolable in December 1308.[43][44] They also urged Ladislaus Kán to hand over the Holy Crown to Charles.[44] After Kán refused to do so, the legate consecrated a new crown for Charles.[43] Thomas II, Archbishop of Esztergom crowned Charles king with the new crown in the Church of Our Lady in Buda on 15 or 16 June 1309.[43][45] However, most Hungarians regarded his second coronation invalid.[41] The papal legate excommunicated Ladislaus Kán, who finally agreed to give the Holy Crown to Charles.[43] On 27 August 1310, Archbishop Thomas of Esztergom put the Holy Crown on Charles's head in Székesfehérvár; thus, Charles's third coronation was performed in full accordance with customary law.[41][46][45] However, his rule remained nominal in most parts of his kingdom.[41]

Matthew Csák laid siege Buda in June 1311, and Ladislaus Kán declined to assist the king.[47][46] Charles sent an army to invade Matthew Csák's domains in September, but it achieved nothing.[48] In the same year, Ugrin Csák died, enabling Charles to take possession of the deceased lord's domains, which were situated between Požega in Slavonia and Temesvár (present-day Timișoara in Romania).[49][50] The burghers of Kassa (now Košice in Slovakia) assassinated Amadeus Aba in September 1311.[51] Charles's envoys arbitrated an agreement between Aba's sons and the town, which also prescribed that the Abas withdraw from two counties and allow the noblemen inhabiting their domains to freely join Charles.[51] However, the Abas soon entered into an alliance with Matthew Csák against the king.[49] The united forces of the Abas and Matthew Csák besieged Kassa, but Charles routed them in the Battle of Rozgony (now Rozhanovce in Slovakia) on 15 June 1312.[52][45] Almost half of the noblemen who had served Amadeus Aba fought on Charles's side in the battle.[53] In July, Charles captured the Abas' many fortresses in Abaúj, Torna and Sáros counties, including Füzér, Regéc, and Munkács (now Mukacheve in Ukraine).[54] Thereafter he waged war against Matthew Csák, capturing Nagyszombat (now Trnava in Slovakia) in 1313 and Visegrád in 1315, but was unable to win a decisive victory.[49]

Charles transferred his residence from Buda to Temesvár in early 1315.[55][49] Ladislaus Kán died in 1315, but his sons did not yield to Charles.[56][47] Charles launched a campaign against the Kőszegis in Transdanubia and Slavonia in the first half of 1316.[57][58] Local noblemen joined the royal troops, which contributed to the quick collapse of the Kőszegis' rule in southern parts of their domains.[57] Meanwhile, James Borsa made an alliance against Charles with Ladislaus Kán's sons and other lords, including Mojs Ákos and Peter, son of Petenye.[47] They offered the crown to Andrew of Galicia.[47][57] Charles's troops, which were under the command of a former supporter of the Borsas, Dózsa Debreceni, defeated the rebels' united troops at Debrecen at the end of June.[58][59] In the next two months, many fortresses of Borsa and his allies fell to the royal troops in Bihar, Szolnok, Borsod and Kolozs counties.[58] No primary source has made reference to Charles's bravery or heroic acts, suggesting that he rarely fought in person in the battles and sieges.[55] However, he had excellent strategic skills: it was always Charles who appointed the fortresses to be besieged.[55]

Stefan Dragutin, who controlled the Szerémség, Macsó and other regions along the southern borders of Hungary, died in 1316.[58][60] Charles confirmed the right of Stefan Dragutin's son, Vladislav, to succeed his father and declared Vladislav the lawful ruler of Serbia against Stefan Uroš II Milutin.[58] However, Stefan Uroš II captured Vladislav and invaded the Szerémség.[61][57] Charles launched a counter-campaign across the river Száva and seized the fortress of Macsó.[57] In May 1317, Charles's army suppressed the Abas' revolt, seizing Ungvár and Nevicke Castle (present-day Uzhhorod and Nevytsky Castle in Ukraine) from them.[62] After that, Charles invaded Matthew Csák's domains and captured Komárom (now Komárno in Slovakia) on 3 November 1317.[62] After his uncle, King Robert of Naples, granted the Principality of Salerno and the domain of Monte Sant'Angelo to his brother (Charles's younger uncle), John, Charles protested and laid claim to those domains, previously held by his father.[63][64]

After Charles neglected to reclaim Church property that Matthew Csák had seized by force, the prelates of the realm made an alliance in early 1318 against all who would jeopardize their interests.[65] Upon their demand, Charles held a Diet in summer, but refused to confirm the Golden Bull of 1222.[66][58] Before the end of the year, the prelates made a complaint against Charles because he had taken possession of Church property.[58] In 1319, Charles fell so seriously ill that the pope authorized Charles's confessor to absolve him from his all sins before he died, but Charles recovered.[67] In the same year, Dózsa Debreceni, whom Charles had made voivode of Transylvania, launched successful expeditions against Ladislaus Kán's sons and their allies, and Charles's future Judge royal, Alexander Köcski, seized the Kőszegis' six fortresses.[68] In summer, Charles launched an expedition against Stefan Uroš II Milutin, during which he retook Belgrade and restored the Banate of Macsó.[61] The last Diet during Charles's reign was held in 1320; following that, he failed to convoke the yearly public judicial sessions, contravening the provisions of the Golden Bull.[69]

Matthew Csák died on 18 March 1321.[70] The royal army invaded the deceased lord's province, which soon disintegrated because most of his former castellans yielded without resistance.[71][72] Charles personally led the siege of Csák's former seat, Trencsén (now Trenčín in Slovakia), which fell on 8 August.[71][72] About three months later, Charles's new voivode of Transylvania, Thomas Szécsényi, seized Csicsó (present-day Ciceu-Corabia in Romania), the last fortress of Ladislaus Kán's sons.[71][47]

In January 1322, two Dalmatian towns, Šibenik and Trogir, rebelled against Mladen II Šubić, who was a son of Charles's one-time leading partisan, Paul Šubić.[73] The two towns also accepted the suzerainty of the Republic of Venice although Charles had urged Venice not to intervene in the conflict between his subjects.[71] Many Croatian lords (including his own brother, Paul II Šubić) also turned against Mladen, and their coalition defeated him at Klis.[74] In September, Charles marched to Croatia where all the Croatian lords who were opposed to Mladen Šubić yielded to him in Knin.[74] Mladen Šubić also visited Charles, but the king had the powerful lord imprisoned.[74]

Consolidation and reforms (1323–1330)

.svg.png.webp)

As one of his charters concluded, Charles had taken "full possession" of his kingdom by 1323.[75] In the first half of the year, he moved his capital from Temesvár to Visegrád in the centre of his kingdom.[57][76] In the same year, the Dukes of Austria renounced Pressburg (now Bratislava in Slovakia), which they had controlled for decades, in exchange for the support they had received from Charles against Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor, in 1322.[77]

Royal power was only nominally restored in the lands between the Carpathian Mountains and the Lower Danube, which had been united under a voivode, known as Basarab, by the early 1320s.[78] Although Basarab was willing to accept Charles's suzerainty in a peace treaty signed in 1324, he refrained from renouncing control of the lands he had occupied in the Banate of Severin.[78] Charles also attempted to reinstate royal authority in Croatia and Slavonia.[79] He dismissed the Ban of Slavonia, John Babonić, replacing him with Mikcs Ákos in 1325.[79][80] Ban Mikcs invaded Croatia to subjugate the local lords who had seized the former castles of Mladen Subić without the king's approval, but one of the Croatian lords, Ivan I Nelipac, routed the ban's troops in 1326.[79] Consequently, royal power remained only nominal in Croatia during Charles's reign.[79][81] The Babonići and the Kőszegis rose up in open rebellion in 1327, but Ban Mikcs and Alexander Köcski defeated them.[81] In retaliation, at least eight fortresses of the rebellious lords were confiscated in Slavonia and Transdanubia.[82]

Through his victory over the oligarchs, Charles acquired about 60% of the Hungarian castles, along with the estates belonging to them.[83] In 1323, he set about revising his previous land grants, which enabled him to reclaim former royal estates.[84] During his reign, special commissions were set up to detect royal estates that had been unlawfully acquired by their owners.[85] Charles refrained from making perpetual grants to his partisans.[84] Instead, he applied a system of "office fiefs" (or honors), whereby his officials were entitled to enjoy all revenues accrued from their offices, but only for the time they held those offices.[86][87] That system assured the preponderance of royal power, enabling Charles to rule "with the plenitude of power", as he emphasized in one of his charters of 1335.[86][69] He even ignored customary law: for instance, "promoting a daughter to a son", which entitled her to inherit her father's estates instead of her male cousins.[88] Charles also took control of the administration of the Church in Hungary.[89] He appointed the Hungarian prelates at will, without allowing the cathedral chapters to elect them.[89]

He promoted the spread of chivalrous culture in his realms.[90] He regularly held tournaments and introduced the new ranks of "page of the royal court" and "knight of the royal court".[90][91] Charles was the first monarch to create a secular order of knighthood by establishing the Order of Saint George in 1326.[92][93] He was the first Hungarian king to grant helmet crests to his faithful followers to distinguish them from others "by means of an insignium of their own", as he emphasized in one of his charters.[90][94]

Charles reorganized and improved the administration of royal revenues.[95] During his reign, five new "chambers" (administrative bodies headed by German, Italian or Hungarian merchants) were established for the control and collection of royal revenues from coinage, monopolies and custom duties.[96] In 1327, he partially abolished the royal monopoly of gold mining, giving one third of the royal revenues from the gold extracted from a newly opened mine to the owner of the land where that mine was discovered.[97] In the next few years, new gold mines were opened at Körmöcbánya (now Kremnica in Slovakia), Nagybánya (present-day Baia Mare in Romania) and Aranyosbánya (now Baia de Arieș in Romania).[95][98] Hungarian mines yielded about 1,400 kilograms (3,100 lb) of gold around 1330, which made up more than 30% of the world's total production.[87] The minting of gold coins began under Charles's auspices in the lands north of the Alps in Europe.[97] His florins, which were modelled on the gold coins of Florence, were first issued in 1326.[97][99]

Internal peace and increasing royal revenues strengthened the international position of Hungary in the 1320s.[100][101] On 13 February 1327, Charles and John of Bohemia signed an alliance in Nagyszombat (present-day Trnava in Slovakia) against the Habsburgs, who had occupied Pressburg.[70] In the summer of 1328 Hungarian and Bohemian troops invaded Austria and routed the Austrian army on the banks of the Leitha River.[102] On 21 September 1328, Charles signed a peace treaty with the three dukes of Austria (Frederick the Fair, Albert the Lame, and Otto the Merry), who renounced Pressburg and the Muraköz (now Međimurje in Croatia).[77][103] The following year, Serbian troops laid siege to Belgrade, but Charles relieved the fortress.[81]

Alliance with his father-in-law, Władysław I the Elbow-high, King of Poland, became a permanent element of Charles's foreign policy in the 1320s.[77] After being defeated by the united forces of the Teutonic Knights and John of Bohemia, Władysław I sent his son and heir, Casimir, to Visegrád in late 1329 to seek assistance from Charles.[104] During his stay in Charles's court, the nineteen-year-old Casimir seduced Clara Záh, who was a lady-in-waiting of Charles's wife, Elisabeth of Poland, according to an Italian writer.[105][106][107] On 17 April 1330, the young lady's father, Felician Záh, stormed into the dining room of the royal palace at Visegrád with a sword in his hand and attacked the royal family.[108] Záh wounded both Charles and the queen on their right hand and attempted to kill their two sons, Louis and Andrew, before the royal guards killed him.[109] Charles's revenge was brutal: with the exception of Clara, Felician Záh's children were tortured to death; Clara's lips and all eight fingers were cut before she was dragged by a horse through the streets of many towns; all of Felician's other relatives within the third degree of kinship (including his sons-in-law and sisters) were executed, and those within the seventh degree were condemned to perpetual serfdom.[110][107]

Active foreign policy (1330–1339)

In September 1330, Charles launched a military expedition against Basarab I of Wallachia who had attempted to get rid of his suzerainty.[111][81] After seizing the fortress of Severin (present-day Drobeta-Turnu Severin in Romania), he refused to make peace with Basarab and marched towards Curtea de Argeș, which was Basarab's seat.[111] The Wallachians applied scorched earth tactics, compelling Charles to make a truce with Basarab and withdraw his troops from Wallachia.[111] While the royal troops were marching through a narrow pass across the Southern Carpathians on 9 November, the Wallachians ambushed them.[112] During the next four days, the royal army was decimated; Charles could only escape from the battlefield after changing his clothes with one of his knights, Desiderius Hédervári, who sacrificed his life to enable the king's escape.[112][77] Charles did not attempt a new invasion of Wallachia, which subsequently developed into an independent principality.[112][77]

In September 1331, Charles made an alliance with Otto the Merry, Duke of Austria, against Bohemia.[113] He also sent reinforcements to Poland to fight against the Teutonic Knights and the Bohemians.[114] In 1332 he signed a peace treaty with John of Bohemia and mediated a truce between Bohemia and Poland.[113][115] In 1332 Charles allowed the collection of the papal tithe (the tenth part of the Church revenues) in his realms only after the Holy See agreed to give one third of the money collected to him.[89] After years of negotiations, Charles visited his uncle, Robert, in Naples in July 1333.[116][117] Two months later, Charles's son, Andrew, was betrothed to Robert's granddaughter, Joanna, who had been made her grandfather's heir.[117][118] Charles returned to Hungary in early 1334.[119] In retaliation for a previous Serbian raid, he invaded Serbia and captured the fortress of Galambóc (now Golubac in Serbia).[81]

In summer 1335, the delegates of John of Bohemia and the new King of Poland, Casimir III, entered into negotiations in Trencsén to put an end to the conflicts between the two countries.[120] With Charles's mediation, a compromise was reached on 24 August: John of Bohemia renounced his claim to Poland and Casimir of Poland acknowledged John of Bohemia's suzerainty in Silesia.[120][121] On 3 September, Charles signed an alliance with John of Bohemia in Visegrád, which was primarily formed against the Dukes of Austria.[122] Upon Charles's invitation, John of Bohemia and Casimir of Poland met in Visegrád in November.[121] During the Congress of Visegrád, the two rulers confirmed the compromise that their delegates had worked out in Trencsén.[123] Casimir III also promised to pay 400,000 groschen to John of Bohemia, but a part of this indemnification (120,000 groschen) was finally paid off by Charles instead of his brother-in-law.[123] The three rulers agreed upon a mutual defence union against the Habsburgs, and a new commercial route was set up to enable merchants travelling between Hungary and the Holy Roman Empire to bypass Vienna.[121]

The Babonići and the Kőszegis made an alliance with the Dukes of Austria in January 1336.[101][124] John of Bohemia, who claimed Carinthia from the Habsburgs, invaded Austria in February.[124][125] Casimir III of Poland came to Austria to assist him in late June.[125] Charles soon joined them at Marchegg.[125] The dukes sought reconciliation and signed a peace treaty with John of Bohemia in July.[124] Charles signed a truce with them on 13 December, and launched a new expedition against Austria early the next year.[126] He forced the Babonići and the Kőszegis to yield, and the latter were also compelled to hand over to him their fortresses along the frontier in exchange for faraway castles.[101][127] Charles's peace treaty with Albert and Otto of Austria, which was signed on 11 September 1337, forbade both the dukes and Charles to give shelter to the other party's rebellious subjects.[127]

Charles continued the reform of coinage in the late 1330s.[98] In 1336, he abolished the compulsory exchange of old coins for newly issued coins for villagers, but introduced a new tax, the chamber's profit, to compensate the loss of royal revenues.[128][98] Two years later, Charles ordered the minting of a new silver penny and prohibited payments made in foreign coins or silver bars.[98]

John of Bohemia's heir, Charles, Margrave of Moravia, visited Charles in Visegrád in early 1338.[129] The margrave acknowledged the right of Charles's son, Louis, to inherit Poland if Casimir III died without a son in exchange for Charles's promise to persuade Casimir III not to invade Silesia.[130] Two leading Polish lords, Zbigniew, chancellor of Cracow, and Spycimir Leliwita, also supported this plan and persuaded Casimir III, who lost his first wife on 26 May 1339, to start negotiations with Charles.[130] In July, Casimir came to Hungary and designated his sister (Charles's wife), Elizabeth, and her sons as his heirs.[131][132] On his sons' behalf, Charles promised that they would make every effort to reconquer all lands that Poland had lost and that they would refrain from employing foreigners in Poland.[131][132]

.jpg.webp)

Last years (1339–1342)

Charles obliged the Kőszegis to renounce their last fortresses along the western borders of the kingdom in 1339 or 1340.[84] He divided the large Zólyom County (now in Slovakia), which had been dominated by a powerful local lord, Donch, into three smaller counties in 1340.[80] The following year, Charles also forced Donch to renounce his two fortresses in Zólyom in exchange for one castle in the distant Kraszna County (in present-day Romania).[133] Around the same time, Stephen Uroš IV Dušan of Serbia, invaded Sirmium and captured Belgrade.[81][134]

Charles was ailing during the last years of his life.[135] He died in Visegrád on 16 July 1342.[136] His corpse was first delivered to Buda where a Mass was said for his soul.[136] From Buda, his corpse was taken to Székesfehérvár.[136] He was buried in the Székesfehérvár Basilica a month after his death.[108] His brother-in-law, Casimir III of Poland, and Charles, Margrave of Moravia, were present at his funeral, an indication of Charles's international prestige.[108]

Family

| Ancestors of Charles I of Hungary[137][138][139][140] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Anonymi descriptio Europae orientalis ("An Anonymous' Description of Eastern Europe") wrote, in the first half of 1308, that "the daughter of the strapping Duke of Ruthenia, Leo, has recently married Charles, King of Hungary".[141][142] Charles also stated in a charter of 1326 that he once travelled to "Ruthenia" (or Halych-Lodomeria) in order to bring his first wife back to Hungary.[143][142] A charter issued on 23 June 1326 referred to Charles's wife, Queen Mary.[144] Historian Gyula Kristó says, the three documents show that Charles married a daughter of Leo II of Galicia in late 1305 or early 1306.[145] Historian Enikő Csukovits accepts Kristó's interpretation, but she writes that Mary of Galicia most probably died before the marriage.[146] The Polish scholar, Stanisław Sroka, rejects Kristó's interpretation, stating that Leo I—who was born in 1292, according to him—could hardly have fathered Charles's first wife.[147] In accordance with previous academic consensus, Sroka says that Charles's first wife was Mary of Bytom from the Silesian branch of the Piast dynasty.[148]

The Illuminated Chronicle stated that Charles's "first consort, Maria ... was of the Polish nation" and she was "the daughter of Duke Casimir".[149][141] Sroka proposes that Mary of Bytom married Charles in 1306, but Kristó writes that their marriage probably took place in the first half of 1311.[150][151] The Illuminated Chronicle recorded that she died on 15 December 1317, but a royal charter issued on 12 July 1318 stated that her husband made a land grant with her consent.[152] Charles's next—second or third—wife was Beatrice of Luxembourg, who was a daughter of Henry VII, Holy Roman Emperor, and the sister of John, King of Bohemia.[152] Their marriage took place before the end of February 1319.[153] She died in childbirth in early November in the same year.[153] Charles's last wife, Elisabeth, daughter of Władysław I, King of Poland,[154] was born around 1306.[154] Their marriage took place on 6 July 1320.[154]

Most 14th-century Hungarian chroniclers write that Charles and Elisabeth of Poland had five sons.[155] Their first son, Charles, was born in 1321 and died in the same year according to the Illuminated Chronicle.[156] However, a charter of June 1323 states that the child had died in this month.[157] The second son of Charles and Elisabeth, Ladislaus, was born in 1324.[158] The marriage of Ladislaus and Anne, a daughter of King John of Bohemia, was planned by their parents, but Ladislaus died in 1329.[159] Charles's and Elisabeth's third son, Louis, who was born in 1326, survived his father and succeeded him as King of Hungary.[159] His younger brothers, Andrew and Stephen, who were born in 1327 and 1332, respectively, also survived Charles.[159]

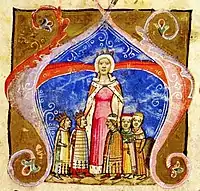

Although no contemporaneous or nearly contemporaneous sources made mention of any further children, Charles may have fathered two daughters, according to historians Zsuzsa Teke and Gyula Kristó.[159][160] Zsuzsa Teke writes that they were born to Mary of Bytom, but the nearly contemporaneous Peter of Zittau wrote that she had died childless.[160][158] Gyula Kristó proposes that a miniature in the Illuminated Chronicle, which depicts Elisabeth of Poland and five children, implies that she gave birth to Charles's two daughters, because Kristó identifies two of the three children standing on her right as daughters.[155] The elder of Charles's two possible daughters, Catherine, who was born in the early 1320s, was the wife of Henry II, Duke of Świdnica.[155] Their only daughter, Anne, grew up in the Hungarian royal court after her parents' death, implying that Charles and Elisabeth of Poland were her grandparents.[161] Historian Kazimierz Jasiński says that Elisabeth, the wife of Boleslaus II of Troppau, was also Charles's daughter.[158] If she was actually Charles's daughter, she must have been born in about 1330, according to Kristó.[158]

Charles also fathered an illegitimate son, Coloman, who was born in early 1317.[150][162] His mother was a daughter of Gurke Csák.[162] Coloman was elected Bishop of Győr in 1336.[163]

The betrothal of Charles to Elisabeth of Poland depicted in Illuminated Chronicle

The betrothal of Charles to Elisabeth of Poland depicted in Illuminated Chronicle Charles's wife, Elisabeth of Poland and her five children depicted in Illuminated Chronicle

Charles's wife, Elisabeth of Poland and her five children depicted in Illuminated Chronicle

Legacy

.jpg.webp)

Charles often declared that his principal aim was the "restoration of the ancient good conditions" of the kingdom.[164] On his coat-of-arms, he united the "Árpád stripes" with the motifs of the coat-of-arms of his paternal family, which emphasized his kinship with the first royal house of Hungary.[164] During his reign, Charles reunited Hungary and introduced administrative and fiscal reforms.[108] He bequeathed to his son, Louis the Great, a "bulging exchequer and an effective system of taxation", according to scholar Bryan Cartledge.[134] Nevertheless, Louis the Great's achievements overshadowed Charles's reputation.[108]

The only contemporaneous record of Charles's deeds were made by a Franciscan friar who was hostile towards the monarch.[108] Instead of emphasizing Charles's achievements in the reunification of the country, the friar described in detail the negative episodes of Charles's reign.[108] In particular, the unusual cruelty that the king showed after Felician Záh's assassination attempt on the royal family contributed to the negative picture of Charles's personality.[108] The Franciscan friar attributed Charles's defeat by Basarab of Wallachia as a punishment from God for the king's revenge.[108]

References

- Kristó 2002, p. 24.

- Csukovits 2012a, p. 112.

- Dümmerth 1982, p. 220.

- Engel 2001, pp. 110, 383.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 33.

- Engel 2001, p. 110.

- Engel 2001, pp. 98, 110.

- Bartl et al. 2002, p. 34.

- Kristó 2002, p. 25.

- Magaš 2007, p. 59.

- Fine 1994, p. 207.

- Kelly 2003, p. 8.

- Dümmerth 1982, p. 222–223.

- Dümmerth 1982, p. 224.

- The Divine Comedy, Dante Alighieri (Paradise, 9.3.), p. 667.

- Kelly 2003, p. 276.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, pp. 188–189.

- Fine 1994, p. 208.

- Dümmerth 1982, p. 228.

- Engel 2001, p. 144.

- Engel 2001, p. 111.

- Kristó 2002, pp. 25–26.

- Dümmerth 1982, p. 229.

- Engel 2001, p. 128.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 188.

- Kristó 2002, p. 26.

- Engel 2001, p. 124.

- Kontler 1999, p. 84.

- Engel 2001, pp. 125–126.

- Engel 2001, pp. 128–129.

- Engel 2001, p. 129.

- Zsoldos 2013, p. 212.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle: (ch. 188.133), p. 143.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 189.

- Dümmerth 1982, pp. 232–234.

- Dümmerth 1982, p. 233.

- Kristó 2002, p. 27.

- Kristó 2002, p. 28.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 190.

- Engel 2001, pp. 129–130.

- Engel 2001, p. 130.

- Pop 2005, p. 251.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 191.

- Kristó 2002, p. 29.

- Bartl et al. 2002, p. 37.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 192.

- Pop 2005, p. 252.

- Kristó 2002, p. 32.

- Engel 2001, p. 131.

- Zsoldos 2013, p. 222.

- Zsoldos 2013, p. 221.

- Zsoldos 2013, p. 229.

- Zsoldos 2013, p. 236.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 193.

- Kristó 2002, p. 35.

- Kontler 1999, p. 88.

- Engel 2001, p. 132.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 194.

- Zsoldos 2013, p. 235.

- Fine 1994, p. 260.

- Fine 1994, p. 261.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 195.

- Kristó 2002, p. 41.

- Dümmerth 1982, p. 353.

- Engel 2001, p. 142.

- Engel 2001, p. 141.

- Kristó 2002, p. 36.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 196.

- Engel 2001, p. 140.

- Bartl et al. 2002, p. 38.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 197.

- Engel 2001, p. 133.

- Fine 1994, pp. 210–211.

- Fine 1994, p. 212.

- Engel 2001, pp. 144, 391.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 198.

- Engel 2001, p. 136.

- Sălăgean 2005, p. 149.

- Fine 1994, p. 213.

- Engel 2001, p. 145.

- Engel 2001, p. 135.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 199.

- Engel 2001, pp. 149–150.

- Engel 2001, p. 150.

- Engel 2001, p. 149.

- Kontler 1999, p. 89.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 34.

- Engel 2001, pp. 140, 178.

- Engel 2001, p. 143.

- Boulton 2000, p. 29.

- Engel 2001, pp. 146–147.

- Boulton 2000, p. 27.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 35.

- Engel 2001, p. 147.

- Kontler 1999, p. 90.

- Engel 2001, p. 154.

- Engel 2001, p. 156.

- Engel 2001, p. 155.

- Kontler 1999, p. 91.

- Kontler 1999, p. 92.

- Engel 2001, p. 134.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 200.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 201.

- Knoll 1972, pp. 51, 54.

- Knoll 1972, p. 54.

- Dümmerth 1982, p. 341.

- Engel 2001, p. 139.

- Engel 2001, p. 138.

- Kristó 2002, p. 40.

- Kristó 2002, pp. 40–41.

- Sălăgean 2005, p. 194.

- Sălăgean 2005, p. 195.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 202.

- Knoll 1972, p. 58.

- Knoll 1972, p. 61.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, pp. 202–203.

- Dümmerth 1982, p. 352.

- Engel 2001, pp. 137–138.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 203.

- Knoll 1972, p. 73.

- Engel 2001, p. 137.

- Knoll 1972, pp. 74–75.

- Knoll 1972, p. 75.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 204.

- Knoll 1972, p. 86.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, pp. 204–205.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 205.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 91–92.

- Knoll 1972, p. 95.

- Knoll 1972, pp. 95–96.

- Knoll 1972, p. 96.

- Solymosi & Körmendi 1981, p. 206.

- Engel 2001, pp. 145, 150.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 36.

- Csukovits 2012a, p. 115.

- Kristó 2002, p. 43.

- Teke 1994, p. 48.

- Dümmerth 1982, pp. 62–63, Appendix.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 271, Appendix 5.

- Franzl 2002, pp. 279–280.

- Kristó 2005, p. 15.

- Sroka 1992, p. 261.

- Kristó 2005, p. 16.

- Kristó 2005, p. 17.

- Kristó 2005, pp. 17–18.

- Csukovits 2012a, p. 114.

- Sroka 1992, p. 262.

- Sroka 1992, p. 263.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle: (ch. 197.139), p. 145.

- Sroka 1992, p. 265.

- Kristó 2005, p. 19.

- Kristó 2005, pp. 19–20.

- Kristó 2005, p. 22.

- Knoll 1972, p. 42.

- Kristó 2005, pp. 25–26.

- Kristó 2005, p. 23.

- Kristó 2005, pp. 23–24.

- Kristó 2005, p. 26.

- Kristó 2005, p. 27.

- Teke 1994, p. 49.

- Kristó 2005, p. 25.

- Szovák 1994, p. 316.

- Szovák 1994, p. 317.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 88–89.

Sources

Primary sources

- The Divine Comedy: The Inferno, the Purgatorio, and the Paradiso – Dante Alighieri (Translated by John Ciardi) (2003). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-451-20863-3.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle: Chronica de Gestis Hungarorum (Edited by Dezső Dercsényi) (1970). Corvina, Taplinger Publishing. ISBN 0-8008-4015-1.

Secondary sources

- Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 922–923.

- Bartl, Július; Čičaj, Viliam; Kohútova, Mária; Letz, Róbert; Segeš, Vladimír; Škvarna, Dušan (2002). Slovak History: Chronology & Lexicon. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Slovenské Pedegogické Nakladatel'stvo. ISBN 0-86516-444-4.

- Boulton, D'A. J. D. (2000). The Knights of the Crown. The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-795-5.

- Cartledge, Bryan (2011). The Will to Survive: A History of Hungary. C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-84904-112-6.

- Csukovits, Enikő (2012a). "I. Károly". In Gujdár, Noémi; Szatmáry, Nóra (eds.). Magyar királyok nagykönyve: Uralkodóink, kormányzóink és az erdélyi fejedelmek életének és tetteinek képes története [Encyclopedia of the Kings of Hungary: An Illustrated History of the Life and Deeds of Our Monarchs, Regents and the Princes of Transylvania] (in Hungarian). Reader's Digest. pp. 112–115. ISBN 978-963-289-214-6.

- Csukovits, Enikő (2012b). Az Anjouk Magyarországon. I. rész. I. Károly és uralkodása (1301‒1342) [The Angevins in Hungary, Vol. 1. Charles I and His Reign (1301‒1342)] (in Hungarian). MTA Bölcsészettudományi Kutatóközpont Történettudományi Intézet. ISBN 978-963-9627-53-6.

- Dümmerth, Dezső (1982). Az Anjou-ház nyomában [On the House of Anjou] (in Hungarian). Panoráma. ISBN 963-243-179-0.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Franzl, Johan (2002). I. Rudolf: Az első Habsburg a német trónon [Rudolph I: The First Habsburg on the German Throne] (in Hungarian). Corvina. ISBN 963-13-5138-6.

- Kelly, Samantha (2003). The New Solomon: Robert of Naples (1309–1343) and Fourteenth-Century Kingship. Brill. ISBN 90-04-12945-6.

- Knoll, Paul W. (1972). The Rise of the Polish Monarchy: Piast Poland in East Central Europe, 1320–1370. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-44826-6.

- Kontler, László (1999). Millennium in Central Europe: A History of Hungary. Atlantisz Publishing House. ISBN 963-9165-37-9.

- Kristó, Gyula; Makk, Ferenc (1996). Az Árpád-ház uralkodói [Rulers of the House of Árpád] (in Hungarian). I.P.C. Könyvek. ISBN 963-7930-97-3.

- Kristó, Gyula (2002). "I. Károly". In Kristó, Gyula (ed.). Magyarország vegyes házi királyai [The Kings of Various Dynasties of Hungary] (in Hungarian). Szukits Könyvkiadó. pp. 23–44. ISBN 963-9441-58-9.

- Kristó, Gyula (2005). "Károly Róbert családja [Charles Robert's family]" (PDF). Aetas (in Hungarian). 20 (4): 14–28. ISSN 0237-7934.

- Magaš, Branka (2007). Croatia Through History. SAQI. ISBN 978-0-86356-775-9.

- Pop, Ioan-Aurel (2005). "Transylvania in the 14th century and the first half of the 15th century (1300–1456)". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Nägler, Thomas (eds.). The History of Transylvania, Vol. I. (Until 1541). Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies). pp. 247–298. ISBN 973-7784-00-6.

- Sălăgean, Tudor (2005). "Romanian Society in the Early Middle Ages (9th–14th Centuries AD)". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Bolovan, Ioan (eds.). History of Romania: Compendium. Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies). pp. 133–207. ISBN 978-973-7784-12-4.

- Solymosi, László; Körmendi, Adrienne (1981). "A középkori magyar állam virágzása és bukása, 1301–1506 [The Heyday and Fall of the Medieval Hungarian State, 1301–1526]". In Solymosi, László (ed.). Magyarország történeti kronológiája, I: a kezdetektől 1526-ig [Historical Chronology of Hungary, Volume I: From the Beginning to 1526] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 188–228. ISBN 963-05-2661-1.

- Sroka, Stanisław (1992). "A Hungarian-Galician Marriage at the Beginning of the Fourteenth Century?". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 16 (3–4): 261–268. JSTOR 41036478.

- Szovák, Kornél (1994). "Kálmán 3. [Coloman 3.]". In Kristó, Gyula; Engel, Pál; Makk, Ferenc (eds.). Korai magyar történeti lexikon (9–14. század) [Encyclopedia of the Early Hungarian History (9th–14th centuries)] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 316–317. ISBN 963-05-6722-9.

- Teke, Zsuzsa (1994). "Anjouk [The Angevins]". In Kristó, Gyula; Engel, Pál; Makk, Ferenc (eds.). Korai magyar történeti lexikon (9–14. század) [Encyclopedia of the Early Hungarian History (9th–14th centuries)] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 46–49. ISBN 963-05-6722-9.

- Zsoldos, Attila (2013). "Kings and Oligarchs in Hungary at the Turn of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries". Hungarian Historical Review. 2 (2): 211–242.

Further reading

- Krstić, Aleksandar R. (2016). "The Rival and the Vassal of Charles Robert of Anjou: King Vladislav II Nemanjić". Banatica. 26 (2): 33–51.

- Lucherini, Vinni (2013). "The Journey of Charles I, King of Hungary, from Visegrád to Naples (1333): Its Political Implications and Artistic Consequences". Hungarian Historical Review. 2 (2): 341–362.

- Michaud, Claude (2000). "The kingdoms of Central Europe in the fourteenth century". In Jones, Michael (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume VI: c. 1300-c. 1415. Cambridge University Press. pp. 735–763. ISBN 0-521-36290-3.

- Rácz, György (2013). "The Congress of Visegrád in 1335: Diplomacy and Representation". Hungarian Historical Review. 2 (2): 261–287.

- Skorka, Renáta (2013). "With a Little Help from the Cousins: Charles I and the Habsburg Dukes of Austria during the Interregnum". Hungarian Historical Review. 2 (2): 243–260.

.svg.png.webp)