Chemical bond

A chemical bond is a lasting attraction between atoms, ions or molecules that enables the formation of molecules. The bond may result from the electrostatic force between oppositely charged ions as in ionic bonds or through the sharing of electrons as in covalent bonds. The strength of chemical bonds varies considerably; there are "strong bonds" or "primary bonds" such as covalent, ionic and metallic bonds, and "weak bonds" or "secondary bonds" such as dipole–dipole interactions, the London dispersion force and hydrogen bonding.

Since opposite charges attract via a simple electromagnetic force, the negatively charged electrons orbiting the nucleus and the positively charged protons in the nucleus attract each other. An electron positioned between two nuclei will be attracted to both of them, and the nuclei will be attracted toward electrons in this position. This attraction constitutes the chemical bond. Due to the matter wave nature of electrons and their smaller mass, they must occupy a much larger amount of volume compared with the nuclei, and this volume occupied by the electrons keeps the atomic nuclei in a bond relatively far apart, as compared with the size of the nuclei themselves.[1]

In general, strong chemical bonding is associated with the sharing or transfer of electrons between the participating atoms. The atoms in molecules, crystals, metals and diatomic gases—indeed most of the physical environment around us—are held together by chemical bonds, which dictate the structure and the bulk properties of matter.

All bonds can be explained by quantum theory, but, in practice, simplification rules allow chemists to predict the strength, directionality, and polarity of bonds. The octet rule and VSEPR theory are two examples. More sophisticated theories are valence bond theory, which includes orbital hybridization[2] and resonance,[3] and molecular orbital theory[4] which includes linear combination of atomic orbitals and ligand field theory. Electrostatics are used to describe bond polarities and the effects they have on chemical substances.

Overview of main types of chemical bonds

A chemical bond is an attraction between atoms. This attraction may be seen as the result of different behaviors of the outermost or valence electrons of atoms. These behaviors merge into each other seamlessly in various circumstances, so that there is no clear line to be drawn between them. However it remains useful and customary to differentiate between different types of bond, which result in different properties of condensed matter.

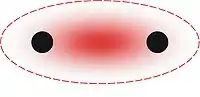

In the simplest view of a covalent bond, one or more electrons (often a pair of electrons) are drawn into the space between the two atomic nuclei. Energy is released by bond formation.[5] This is not as a result of reduction in potential energy, because the attraction of the two electrons to the two protons is offset by the electron-electron and proton-proton repulsions. Instead, the release of energy (and hence stability of the bond) arises from the reduction in kinetic energy due to the electrons being in a more spatially distributed (i.e. longer de Broglie wavelength) orbital compared with each electron being confined closer to its respective nucleus.[6] These bonds exist between two particular identifiable atoms and have a direction in space, allowing them to be shown as single connecting lines between atoms in drawings, or modeled as sticks between spheres in models.

In a polar covalent bond, one or more electrons are unequally shared between two nuclei. Covalent bonds often result in the formation of small collections of better-connected atoms called molecules, which in solids and liquids are bound to other molecules by forces that are often much weaker than the covalent bonds that hold the molecules internally together. Such weak intermolecular bonds give organic molecular substances, such as waxes and oils, their soft bulk character, and their low melting points (in liquids, molecules must cease most structured or oriented contact with each other). When covalent bonds link long chains of atoms in large molecules, however (as in polymers such as nylon), or when covalent bonds extend in networks through solids that are not composed of discrete molecules (such as diamond or quartz or the silicate minerals in many types of rock) then the structures that result may be both strong and tough, at least in the direction oriented correctly with networks of covalent bonds.[7] Also, the melting points of such covalent polymers and networks increase greatly.

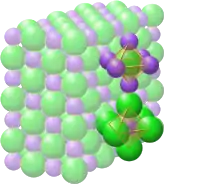

In a simplified view of an ionic bond, the bonding electron is not shared at all, but transferred. In this type of bond, the outer atomic orbital of one atom has a vacancy which allows the addition of one or more electrons. These newly added electrons potentially occupy a lower energy-state (effectively closer to more nuclear charge) than they experience in a different atom. Thus, one nucleus offers a more tightly bound position to an electron than does another nucleus, with the result that one atom may transfer an electron to the other. This transfer causes one atom to assume a net positive charge, and the other to assume a net negative charge. The bond then results from electrostatic attraction between the positive and negatively charged ions. Ionic bonds may be seen as extreme examples of polarization in covalent bonds. Often, such bonds have no particular orientation in space, since they result from equal electrostatic attraction of each ion to all ions around them. Ionic bonds are strong (and thus ionic substances require high temperatures to melt) but also brittle, since the forces between ions are short-range and do not easily bridge cracks and fractures. This type of bond gives rise to the physical characteristics of crystals of classic mineral salts, such as table salt.

A less often mentioned type of bonding is metallic bonding. In this type of bonding, each atom in a metal donates one or more electrons to a "sea" of electrons that reside between many metal atoms. In this sea, each electron is free (by virtue of its wave nature) to be associated with a great many atoms at once. The bond results because the metal atoms become somewhat positively charged due to loss of their electrons while the electrons remain attracted to many atoms, without being part of any given atom. Metallic bonding may be seen as an extreme example of delocalization of electrons over a large system of covalent bonds, in which every atom participates. This type of bonding is often very strong (resulting in the tensile strength of metals). However, metallic bonding is more collective in nature than other types, and so they allow metal crystals to more easily deform, because they are composed of atoms attracted to each other, but not in any particularly-oriented ways. This results in the malleability of metals. The cloud of electrons in metallic bonding causes the characteristically good electrical and thermal conductivity of metals, and also their shiny lustre that reflects most frequencies of white light.

History

Early speculations about the nature of the chemical bond, from as early as the 12th century, supposed that certain types of chemical species were joined by a type of chemical affinity. In 1704, Sir Isaac Newton famously outlined his atomic bonding theory, in "Query 31" of his Opticks, whereby atoms attach to each other by some "force". Specifically, after acknowledging the various popular theories in vogue at the time, of how atoms were reasoned to attach to each other, i.e. "hooked atoms", "glued together by rest", or "stuck together by conspiring motions", Newton states that he would rather infer from their cohesion, that "particles attract one another by some force, which in immediate contact is exceedingly strong, at small distances performs the chemical operations, and reaches not far from the particles with any sensible effect."

In 1819, on the heels of the invention of the voltaic pile, Jöns Jakob Berzelius developed a theory of chemical combination stressing the electronegative and electropositive characters of the combining atoms. By the mid 19th century, Edward Frankland, F.A. Kekulé, A.S. Couper, Alexander Butlerov, and Hermann Kolbe, building on the theory of radicals, developed the theory of valency, originally called "combining power", in which compounds were joined owing to an attraction of positive and negative poles. In 1904, Richard Abegg proposed his rule that the difference between the maximum and minimum valencies of an element is often eight. At this point, valency was still an empirical number based only on chemical properties.

However the nature of the atom became clearer with Ernest Rutherford's 1911 discovery that of an atomic nucleus surrounded by electrons in which he quoted Nagaoka rejected Thomson's model on the grounds that opposite charges are impenetrable. In 1904, Nagaoka proposed an alternative planetary model of the atom in which a positively charged center is surrounded by a number of revolving electrons, in the manner of Saturn and its rings.[8]

Nagaoka's model made two predictions:

- a very massive atomic center (in analogy to a very massive planet)

- electrons revolving around the nucleus, bound by electrostatic forces (in analogy to the rings revolving around Saturn, bound by gravitational forces.)

Rutherford mentions Nagaoka's model in his 1911 paper in which the atomic nucleus is proposed.[9]

At the 1911 Solvay Conference, in the discussion of what could regulate energy differences between atoms, Max Planck simply stated: "The intermediaries could be the electrons."[10] These nuclear models suggested that electrons determine chemical behavior.

Next came Niels Bohr's 1913 model of a nuclear atom with electron orbits. In 1916, chemist Gilbert N. Lewis developed the concept of electron-pair bonds, in which two atoms may share one to six electrons, thus forming the single electron bond, a single bond, a double bond, or a triple bond; in Lewis's own words, "An electron may form a part of the shell of two different atoms and cannot be said to belong to either one exclusively."[11]

Also in 1916, Walther Kossel put forward a theory similar to Lewis' only his model assumed complete transfers of electrons between atoms, and was thus a model of ionic bonding. Both Lewis and Kossel structured their bonding models on that of Abegg's rule (1904).

Niels Bohr also proposed a model of the chemical bond in 1913. According to his model for a diatomic molecule, the electrons of the atoms of the molecule form a rotating ring whose plane is perpendicular to the axis of the molecule and equidistant from the atomic nuclei. The dynamic equilibrium of the molecular system is achieved through the balance of forces between the forces of attraction of nuclei to the plane of the ring of electrons and the forces of mutual repulsion of the nuclei. The Bohr model of the chemical bond took into account the Coulomb repulsion – the electrons in the ring are at the maximum distance from each other.[12][13]

In 1927, the first mathematically complete quantum description of a simple chemical bond, i.e. that produced by one electron in the hydrogen molecular ion, H2+, was derived by the Danish physicist Øyvind Burrau.[14] This work showed that the quantum approach to chemical bonds could be fundamentally and quantitatively correct, but the mathematical methods used could not be extended to molecules containing more than one electron. A more practical, albeit less quantitative, approach was put forward in the same year by Walter Heitler and Fritz London. The Heitler–London method forms the basis of what is now called valence bond theory.[15] In 1929, the linear combination of atomic orbitals molecular orbital method (LCAO) approximation was introduced by Sir John Lennard-Jones, who also suggested methods to derive electronic structures of molecules of F2 (fluorine) and O2 (oxygen) molecules, from basic quantum principles. This molecular orbital theory represented a covalent bond as an orbital formed by combining the quantum mechanical Schrödinger atomic orbitals which had been hypothesized for electrons in single atoms. The equations for bonding electrons in multi-electron atoms could not be solved to mathematical perfection (i.e., analytically), but approximations for them still gave many good qualitative predictions and results. Most quantitative calculations in modern quantum chemistry use either valence bond or molecular orbital theory as a starting point, although a third approach, density functional theory, has become increasingly popular in recent years.

In 1933, H. H. James and A. S. Coolidge carried out a calculation on the dihydrogen molecule that, unlike all previous calculation which used functions only of the distance of the electron from the atomic nucleus, used functions which also explicitly added the distance between the two electrons.[16] With up to 13 adjustable parameters they obtained a result very close to the experimental result for the dissociation energy. Later extensions have used up to 54 parameters and gave excellent agreement with experiments. This calculation convinced the scientific community that quantum theory could give agreement with experiment. However this approach has none of the physical pictures of the valence bond and molecular orbital theories and is difficult to extend to larger molecules.

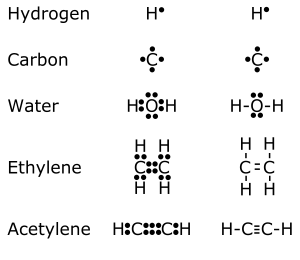

Bonds in chemical formulas

Because atoms and molecules are three-dimensional, it is difficult to use a single method to indicate orbitals and bonds. In molecular formulas the chemical bonds (binding orbitals) between atoms are indicated in different ways depending on the type of discussion. Sometimes, some details are neglected. For example, in organic chemistry one is sometimes concerned only with the functional group of the molecule. Thus, the molecular formula of ethanol may be written in conformational form, three-dimensional form, full two-dimensional form (indicating every bond with no three-dimensional directions), compressed two-dimensional form (CH3–CH2–OH), by separating the functional group from another part of the molecule (C2H5OH), or by its atomic constituents (C2H6O), according to what is discussed. Sometimes, even the non-bonding valence shell electrons (with the two-dimensional approximate directions) are marked, e.g. for elemental carbon .'C'. Some chemists may also mark the respective orbitals, e.g. the hypothetical ethene−4 anion (\/C=C/\ −4) indicating the possibility of bond formation.

Strong chemical bonds

| Typical bond lengths in pm and bond energies in kJ/mol.[17] Bond lengths can be converted to Å by division by 100 (1 Å = 100 pm). | ||

| Bond | Length (pm) |

Energy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| H — Hydrogen | ||

| H–H | 74 | 436 |

| H–O | 96 | 467 |

| H–F | 92 | 568 |

| H–Cl | 127 | 432 |

| C — Carbon | ||

| C–H | 109 | 413 |

| C–C | 154 | 347 |

| C–C= | 151 | |

| =C–C≡ | 147 | |

| =C–C= | 148 | |

| C=C | 134 | 614 |

| C≡C | 120 | 839 |

| C–N | 147 | 308 |

| C–O | 143 | 358 |

| C=O | 745 | |

| C≡O | 1,072 | |

| C–F | 134 | 488 |

| C–Cl | 177 | 330 |

| N — Nitrogen | ||

| N–H | 101 | 391 |

| N–N | 145 | 170 |

| N≡N | 110 | 945 |

| O — Oxygen | ||

| O–O | 148 | 146 |

| O=O | 121 | 495 |

| F, Cl, Br, I — Halogens | ||

| F–F | 142 | 158 |

| Cl–Cl | 199 | 243 |

| Br–H | 141 | 366 |

| Br–Br | 228 | 193 |

| I–H | 161 | 298 |

| I–I | 267 | 151 |

Strong chemical bonds are the intramolecular forces that hold atoms together in molecules. A strong chemical bond is formed from the transfer or sharing of electrons between atomic centers and relies on the electrostatic attraction between the protons in nuclei and the electrons in the orbitals.

The types of strong bond differ due to the difference in electronegativity of the constituent elements. Electronegativity is the tendency for an atom of a given chemical element to attract shared electrons when forming a chemical bond, where the higher the associated electronegativity then the more it attracts electrons. Electronegativity serves as a simple way to quantitatively estimate the bond energy, which characterizes a bond along the continuous scale from covalent to ionic bonding. A large difference in electronegativity leads to more polar (ionic) character in the bond.

Ionic bond

Ionic bonding is a type of electrostatic interaction between atoms that have a large electronegativity difference. There is no precise value that distinguishes ionic from covalent bonding, but an electronegativity difference of over 1.7 is likely to be ionic while a difference of less than 1.7 is likely to be covalent.[18] Ionic bonding leads to separate positive and negative ions. Ionic charges are commonly between −3e to +3e. Ionic bonding commonly occurs in metal salts such as sodium chloride (table salt). A typical feature of ionic bonds is that the species form into ionic crystals, in which no ion is specifically paired with any single other ion in a specific directional bond. Rather, each species of ion is surrounded by ions of the opposite charge, and the spacing between it and each of the oppositely charged ions near it is the same for all surrounding atoms of the same type. It is thus no longer possible to associate an ion with any specific other single ionized atom near it. This is a situation unlike that in covalent crystals, where covalent bonds between specific atoms are still discernible from the shorter distances between them, as measured via such techniques as X-ray diffraction.

Ionic crystals may contain a mixture of covalent and ionic species, as for example salts of complex acids such as sodium cyanide, NaCN. X-ray diffraction shows that in NaCN, for example, the bonds between sodium cations (Na+) and the cyanide anions (CN−) are ionic, with no sodium ion associated with any particular cyanide. However, the bonds between the carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) atoms in cyanide are of the covalent type, so that each carbon is strongly bound to just one nitrogen, to which it is physically much closer than it is to other carbons or nitrogens in a sodium cyanide crystal.

When such crystals are melted into liquids, the ionic bonds are broken first because they are non-directional and allow the charged species to move freely. Similarly, when such salts dissolve into water, the ionic bonds are typically broken by the interaction with water but the covalent bonds continue to hold. For example, in solution, the cyanide ions, still bound together as single CN− ions, move independently through the solution, as do sodium ions, as Na+. In water, charged ions move apart because each of them are more strongly attracted to a number of water molecules than to each other. The attraction between ions and water molecules in such solutions is due to a type of weak dipole-dipole type chemical bond. In melted ionic compounds, the ions continue to be attracted to each other, but not in any ordered or crystalline way.

Covalent bond

Covalent bonding is a common type of bonding in which two or more atoms share valence electrons more or less equally. The simplest and most common type is a single bond in which two atoms share two electrons. Other types include the double bond, the triple bond, one- and three-electron bonds, the three-center two-electron bond and three-center four-electron bond.

In non-polar covalent bonds, the electronegativity difference between the bonded atoms is small, typically 0 to 0.3. Bonds within most organic compounds are described as covalent. The figure shows methane (CH4), in which each hydrogen forms a covalent bond with the carbon. See sigma bonds and pi bonds for LCAO descriptions of such bonding.[19]

Molecules that are formed primarily from non-polar covalent bonds are often immiscible in water or other polar solvents, but much more soluble in non-polar solvents such as hexane.

A polar covalent bond is a covalent bond with a significant ionic character. This means that the two shared electrons are closer to one of the atoms than the other, creating an imbalance of charge. Such bonds occur between two atoms with moderately different electronegativities and give rise to dipole–dipole interactions. The electronegativity difference between the two atoms in these bonds is 0.3 to 1.7.

Single and multiple bonds

A single bond between two atoms corresponds to the sharing of one pair of electrons. The Hydrogen (H) atom has one valence electron. Two Hydrogen atoms can then form a molecule, held together by the shared pair of electrons. Each H atom now has the noble gas electron configuration of helium (He). The pair of shared electrons forms a single covalent bond. The electron density of these two bonding electrons in the region between the two atoms increases from the density of two non-interacting H atoms.

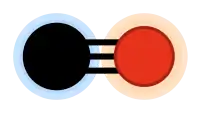

A double bond has two shared pairs of electrons, one in a sigma bond and one in a pi bond with electron density concentrated on two opposite sides of the internuclear axis. A triple bond consists of three shared electron pairs, forming one sigma and two pi bonds. An example is nitrogen. Quadruple and higher bonds are very rare and occur only between certain transition metal atoms.

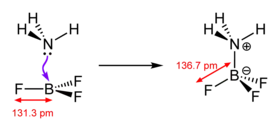

Coordinate covalent bond (dipolar bond)

A coordinate covalent bond is a covalent bond in which the two shared bonding electrons are from the same one of the atoms involved in the bond. For example, boron trifluoride (BF3) and ammonia (NH3) form an adduct or coordination complex F3B←NH3 with a B–N bond in which a lone pair of electrons on N is shared with an empty atomic orbital on B. BF3 with an empty orbital is described as an electron pair acceptor or Lewis acid, while NH3 with a lone pair that can be shared is described as an electron-pair donor or Lewis base. The electrons are shared roughly equally between the atoms in contrast to ionic bonding. Such bonding is shown by an arrow pointing to the Lewis acid.

Transition metal complexes are generally bound by coordinate covalent bonds. For example, the ion Ag+ reacts as a Lewis acid with two molecules of the Lewis base NH3 to form the complex ion Ag(NH3)2+, which has two Ag←N coordinate covalent bonds.

Metallic bonding

In metallic bonding, bonding electrons are delocalized over a lattice of atoms. By contrast, in ionic compounds, the locations of the binding electrons and their charges are static. The free movement or delocalization of bonding electrons leads to classical metallic properties such as luster (surface light reflectivity), electrical and thermal conductivity, ductility, and high tensile strength.

Intermolecular bonding

There are four basic types of bonds that can be formed between two or more (otherwise non-associated) molecules, ions or atoms. Intermolecular forces cause molecules to be attracted or repulsed by each other. Often, these define some of the physical characteristics (such as the melting point) of a substance.

- A large difference in electronegativity between two bonded atoms will cause a permanent charge separation, or dipole, in a molecule or ion. Two or more molecules or ions with permanent dipoles can interact within dipole-dipole interactions. The bonding electrons in a molecule or ion will, on average, be closer to the more electronegative atom more frequently than the less electronegative one, giving rise to partial charges on each atom and causing electrostatic forces between molecules or ions.

- A hydrogen bond is effectively a strong example of an interaction between two permanent dipoles. The large difference in electronegativities between hydrogen and any of fluorine, nitrogen and oxygen, coupled with their lone pairs of electrons, cause strong electrostatic forces between molecules. Hydrogen bonds are responsible for the high boiling points of water and ammonia with respect to their heavier analogues.

- The London dispersion force arises due to instantaneous dipoles in neighbouring atoms. As the negative charge of the electron is not uniform around the whole atom, there is always a charge imbalance. This small charge will induce a corresponding dipole in a nearby molecule, causing an attraction between the two. The electron then moves to another part of the electron cloud and the attraction is broken.

- A cation–pi interaction occurs between a pi bond and a cation.

Theories of chemical bonding

In the (unrealistic) limit of "pure" ionic bonding, electrons are perfectly localized on one of the two atoms in the bond. Such bonds can be understood by classical physics. The forces between the atoms are characterized by isotropic continuum electrostatic potentials. Their magnitude is in simple proportion to the charge difference.

Covalent bonds are better understood by valence bond (VB) theory or molecular orbital (MO) theory. The properties of the atoms involved can be understood using concepts such as oxidation number, formal charge, and electronegativity. The electron density within a bond is not assigned to individual atoms, but is instead delocalized between atoms. In valence bond theory, bonding is conceptualized as being built up from electron pairs that are localized and shared by two atoms via the overlap of atomic orbitals. The concepts of orbital hybridization and resonance augment this basic notion of the electron pair bond. In molecular orbital theory, bonding is viewed as being delocalized and apportioned in orbitals that extend throughout the molecule and are adapted to its symmetry properties, typically by considering linear combinations of atomic orbitals (LCAO). Valence bond theory is more chemically intuitive by being spatially localized, allowing attention to be focused on the parts of the molecule undergoing chemical change. In contrast, molecular orbitals are more "natural" from a quantum mechanical point of view, with orbital energies being physically significant and directly linked to experimental ionization energies from photoelectron spectroscopy. Consequently, valence bond theory and molecular orbital theory are often viewed as competing but complementary frameworks that offer different insights into chemical systems. As approaches for electronic structure theory, both MO and VB methods can give approximations to any desired level of accuracy, at least in principle. However, at lower levels, the approximations differ, and one approach may be better suited for computations involving a particular system or property than the other.

Unlike the spherically symmetrical Coulombic forces in pure ionic bonds, covalent bonds are generally directed and anisotropic. These are often classified based on their symmetry with respect to a molecular plane as sigma bonds and pi bonds. In the general case, atoms form bonds that are intermediate between ionic and covalent, depending on the relative electronegativity of the atoms involved. Bonds of this type are known as polar covalent bonds.

See also

- Bond energy

- Covalent bond

- Halogen bond

- Hydrogen bond

- Ionic bonding

- Metallic bonding

- Pi bond

- Sigma bond

- Three-center four-electron bond

- Three-center two-electron bond

- van der Waals force

References

- Pauling, L. (1931), "The nature of the chemical bond. Application of results obtained from the quantum mechanics and from a theory of paramagnetic susceptibility to the structure of molecules", Journal of the American Chemical Society, 53 (4): 1367–1400, doi:10.1021/ja01355a027

- Jensen, Frank (1999). Introduction to Computational Chemistry. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-98425-2.

- Pauling, Linus (1960). "The Concept of Resonance". The Nature of the Chemical Bond – An Introduction to Modern Structural Chemistry (3rd ed.). Cornell University Press. pp. 10–13. ISBN 978-0801403330.

- Gillespie, R.J. (2004), "Teaching molecular geometry with the VSEPR model", Journal of Chemical Education, 81 (3): 298–304, Bibcode:2004JChEd..81..298G, doi:10.1021/ed081p298

- Housecroft, Catherine E.; Sharpe, Alan G. (2005). Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Pearson Prentice-Hal. p. 100. ISBN 0130-39913-2.

- Rioux, F. (2001). "The Covalent Bond in H2". The Chemical Educator. 6 (5): 288–290. doi:10.1007/s00897010509a. S2CID 97871973.

- Housecroft, Catherine E.; Sharpe, Alan G. (2005). Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Pearson Prentice-Hal. p. 100. ISBN 0130-39913-2.

- B. Bryson (2003). A Short History of Nearly Everything. Broadway Books. ISBN 0-7679-0817-1.

- The Genesis of the Bohr Atom, John L. Heilbron and Thomas S. Kuhn, Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences, Vol. 1 (1969), pp. vi, 211-290 (81 pages), University of California Press.

- Original Proceedings of the 1911 Solvay Conference published 1912. THÉORIE DU RAYONNEMENT ET LES QUANTA. RAPPORTS ET DISCUSSIONS DELA Réunion tenue à Bruxelles, du 30 octobre au 3 novembre 1911, Sous les Auspices dk M. E. SOLVAY. Publiés par MM. P. LANGEVIN et M. de BROGLIE. Translated from the French, p. 127.

- Lewis, Gilbert N. (1916). "The Atom and the Molecule". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 38 (4): 772. doi:10.1021/ja02261a002. S2CID 95865413. a copy

- Pais, Abraham (1986). Inward Bound: Of Matter and Forces in the Physical World. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 228–230. ISBN 978-0-19-851971-3.

- Svidzinsky, Anatoly A.; Marlan O. Scully; Dudley R. Herschbach (2005). "Bohr's 1913 molecular model revisited" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (34): 11985–11988. arXiv:physics/0508161. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10211985S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505778102. PMC 1186029. PMID 16103360.

- Laidler, K. J. (1993). The World of Physical Chemistry. Oxford University Press. p. 346. ISBN 978-0-19-855919-1.

- Heitler, W.; London, F. (1927). "Wechselwirkung neutraler Atome und homoopolare Bindung nach der Quantenmechanik" [Interaction of neutral atoms and homeopolar bonds according to quantum mechanics]. Zeitschrift für Physik. 44 (6–7): 455–472. Bibcode:1927ZPhy...44..455H. doi:10.1007/bf01397394. S2CID 119739102. English translation in Hettema, H. (2000). Quantum Chemistry: Classic Scientific Papers. World Scientific. p. 140. ISBN 978-981-02-2771-5. Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- James, H.H.; Coolidge, A S. (1933). "The Ground State of the Hydrogen Molecule". Journal of Chemical Physics. 1 (12): 825–835. Bibcode:1933JChPh...1..825J. doi:10.1063/1.1749252.

- "Bond Energies". Chemistry Libre Texts. 2 October 2013. Retrieved 2019-02-25.

- Atkins, Peter; Loretta Jones (1997). Chemistry: Molecules, Matter and Change. New York: W.H. Freeman & Co. pp. 294–295. ISBN 978-0-7167-3107-8.

- Streitwieser, Andrew; Heathcock, Clayton H.; Kosower, Edward M. (1992). Introduction to organic chemistry. Heathcock, Clayton H., Kosower, Edward M. (4th ed.). New York: Macmillan. pp. 250. ISBN 978-0024181701. OCLC 24501305.

External links

- W. Locke (1997). Introduction to Molecular Orbital Theory. Retrieved May 18, 2005.

- Carl R. Nave (2005). HyperPhysics. Retrieved May 18, 2005.

- Linus Pauling and the Nature of the Chemical Bond: A Documentary History. Retrieved February 29, 2008.