Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975),[3] also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 to his death in 1975 – until 1949 in mainland China and from then on in Taiwan. After his rule was confined to Taiwan following his defeat by Mao Zedong in the Chinese Civil War, he continued claiming to head the legitimate Chinese government in exile.

Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

蔣中正 蔣介石 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

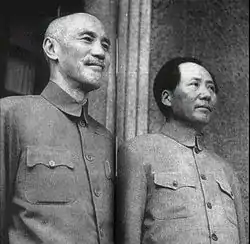

Chiang in 1943 (Allied Victory Souvenir Photo) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the National Government of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 October 1943 – 20 May 1948 Acting: 1 August 1943 – 10 October 1943 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier | T. V. Soong | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice Chairman | Sun Fo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Lin Sen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Position abolished (himself as President of the Republic of China) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 October 1928 – 15 December 1931 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier | Tan Yankai T. V. Soong | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Tan Yankai | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Lin Sen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President of the Republic of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1 March 1950 – 5 April 1975 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier | Yan Xishan Chen Cheng Yu Hung-Chun Yen Chia-kan Chiang Ching-kuo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice President | Li Zongren Chen Cheng Yen Chia-kan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Li Zongren (acting) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Yen Chia-kan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 20 May 1948 – 21 January 1949 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier | Chang Chun Wong Wen-hao Sun Fo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice President | Li Zongren | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Position established (himself as Chairman of the Nationalist government) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Li Zongren (acting) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier of the Republic of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 20 November 1939 – 31 May 1945 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Lin Sen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | H. H. Kung | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | T. V. Soong | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 9 December 1935 – 1 January 1938 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Lin Sen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Wang Jingwei | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | H. H. Kung | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 4 December 1930 – 15 December 1931 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Himself | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | T. V. Soong | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Chen Mingshu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Acting Premier of the Republic of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1 March 1947 – 18 April 1947 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Himself | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | T. V. Soong | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Chang Chun | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Kuomintang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 12 May 1936 – 1 April 1938 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Hu Hanmin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Himself as Director-General of the Kuomintang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 6 July 1926 – 11 March 1927 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Zhang Renjie | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Woo Tsin-hang and Li Yuying | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Director-General of the Kuomintang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1 April 1938 – 5 April 1975 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Wang Jingwei Chen Cheng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Position established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Chiang Ching-kuo (as Chairman of the Kuomintang) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Military Affairs Commission | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 15 December 1931 – 31 May 1946 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Position established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Position abolished | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Chiang Jui-yüan (蔣瑞元) 31 October 1887 Xikou, Zhejiang, Qing Empire | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 5 April 1975 (aged 87) Shilin Residence, Taipei, Republic of China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Cihu Mausoleum, Taoyuan, Taiwan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | Republic of China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Kuomintang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouses | Mao Fumei

(m. 1901; div. 1921)Yao Yecheng

(m. 1913–1927)Chen Jieru

(m. 1921–1927)Soong Mei-ling

(m. 1927) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Baoding Military Academy, Tokyo Shinbu Gakko | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname(s) | "Generalissimo"[1] "Napoleon Bonaparte of China" "Red General"[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allegiance | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1909–1975 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | Generalissimo (特級上將) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 蔣介石 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 蒋介石 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Register name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 蔣周泰 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 蒋周泰 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Milk name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 蔣瑞元 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 蒋瑞元 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| School name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 蔣志清 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 蒋志清 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adopted name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 蔣中正 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 蒋中正 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Born in Chekiang (Zhejiang) Province, Chiang was a member of the Kuomintang (KMT), and a lieutenant of Sun Yat-sen in the revolution to overthrow the Beiyang government and reunify China. With help from the Soviets and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Chiang organized the military for Sun's Canton Nationalist Government and headed the Whampoa Military Academy. Commander-in-chief of the National Revolutionary Army (from which he came to be known as a Generalissimo), he led the Northern Expedition from 1926 to 1928, before defeating a coalition of warlords and nominally reunifying China under a new Nationalist government. Midway through the Northern Expedition, the KMT–CCP alliance broke down and Chiang massacred communists inside the party, triggering a civil war with the CCP (Chinese Communist Party), which he eventually lost in 1949.

As the leader of the Republic of China in the Nanjing decade, Chiang sought to strike a difficult balance between modernizing China, while also devoting resources to defending the nation against the CCP, warlords, and the impending Japanese threat. Trying to avoid a war with Japan while hostilities with the CCP continued, he was kidnapped in the Xi'an Incident, and obliged to form an Anti-Japanese United Front with the CCP. Following the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in 1937, he mobilized China for the Second Sino-Japanese War. For eight years, he led the war of resistance against a vastly superior enemy, mostly from the wartime capital Chongqing. As the leader of a major Allied power, Chiang met with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the Cairo Conference to discuss terms for the Japanese surrender. When the Second World War ended, the Civil War with the communists (by then led by Mao Zedong) resumed. Chiang's nationalists were mostly defeated in a few decisive battles in 1948. In 1949, Chiang's government and army retreated to Taiwan, where Chiang imposed martial law and persecuted critics during the White Terror. Presiding over a period of social reforms and economic prosperity, Chiang won five elections to six-year terms as President of the Republic of China, and was Director-General of the Kuomintang until his death in 1975, three years into his fifth term as president, and one year before Mao's death.

One of the longest-serving non-royal heads of state in the 20th century, Chiang was the longest-serving non-royal ruler of China, having held the post for 46 years. Like Mao, he is regarded as a controversial figure. Supporters credit him with playing a major part in unifying the nation and leading the Chinese resistance against Japan, as well as with countering communist influence and economic development in both Mainland China and Taiwan. Detractors and critics denounce him as a fascist dictator at the front of a corrupt authoritarian regime that suppressed civilians and political dissents,[4] as well as flooding the Yellow River that subsequently caused the Henan Famine during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Other historians such as Jay Taylor argued that despite his many faults, Chiang's ideology notably differs from other authoritarian dictators of the 20th century and does not espouse the ideology of fascism. He argued that Chiang made genuine efforts to improve the economic and social conditions of mainland China and Taiwan such as improving women's rights and land reform.[5] Chiang was also credited with transforming China from a semi-colony of various imperialist powers to an independent country by amending the unequal treaties signed by previous governments,[6] as well as moving various Chinese national treasures and traditional Chinese artworks to the National Palace Museum in Taipei during the 1949 retreat.

Names

Like many other Chinese historical figures, Chiang used several names throughout his life. The name inscribed in the genealogical records of his family is Chiang Chou-t‘ai (Chinese: 蔣周泰; pinyin: Jiǎng Zhōutài; Wade–Giles: Chiang3 Chou1-t‘ai4). This so-called "register name" (譜名) is the one by which his extended relatives knew him, and the one he used in formal occasions, such as when he got married. In deference to tradition, family members did not use the register name in conversation with people outside of the family. The concept of a "real" or original name is/was not as clear-cut in China as it is in the Western world. In honour of tradition, Chinese families waited a number of years before officially naming their children. In the meantime, they used a "milk name" (乳名), given to the infant shortly after his birth and known only to the close family. So the name that Chiang received at birth was Chiang Jui-yüan[7] (Chinese: 蔣瑞元; pinyin: Jiǎng Ruìyuán).

In 1903, the 16-year-old Chiang went to Ningpo to be a student, and he chose a "school name" (學名). This was the formal name of a person, used by older people to address him, and the one he would use the most in the first decades of his life (as the person grew older, younger generations would have to use one of the courtesy names instead). Colloquially, the school name is called "big name" (大名), whereas the "milk name" is known as the "small name" (小名). The school name that Chiang chose for himself was Zhiqing (Chinese: 志清; Wade–Giles: Chi-ch‘ing, which means "purity of aspirations"). For the next fifteen years or so, Chiang was known as Jiang Zhiqing (Wade-Giles: Chiang Chi-ch‘ing). This is the name by which Sun Yat-sen knew him when Chiang joined the republicans in Kwangtung in the 1910s.

In 1912, when Jiang Zhiqing was in Japan, he started to use the name Chiang Kai-shek (Chinese: 蔣介石; pinyin: Jiǎng Jièshí; Wade–Giles: Chiang3 Chieh4-shih2) as a pen name for the articles that he published in a Chinese magazine he founded: Voice of the Army (軍聲). Jieshi is the Pinyin romanization of this name, based on Mandarin, but the most recognized romanized rendering is Kai-shek which is in Cantonese[7] romanization. Because the Republicans were based in Canton (a Cantonese-speaking area, now known as Guangdong), Chiang (who never spoke Cantonese but was a native Wu speaker) became known by Westerners under the Cantonese romanization of his courtesy name, while the family name as known in English seems to be the Mandarin pronunciation of his Chinese family name, transliterated in Wade-Giles.

"Kai-shek"/"Jieshi" soon became Chiang's courtesy name (字). Some think the name was chosen from the classic Chinese book the I Ching; "介于石"; '"[he who is] firm as a rock"', is the beginning of line 2 of Hexagram 16, "豫". Others note that the first character of his courtesy name is also the first character of the courtesy name of his brother and other male relatives on the same generation line, while the second character of his courtesy name shi (石—meaning "stone") suggests the second character of his "register name" tai (泰—the famous Mount Tai). Courtesy names in China often bore a connection with the personal name of the person. As the courtesy name is the name used by people of the same generation to address the person, Chiang soon became known under this new name.

Sometime in 1917 or 1918, as Chiang became close to Sun Yat-sen, he changed his name from Jiang Zhiqing to Jiang Zhongzheng (Chinese: 蔣中正; pinyin: Jiǎng Zhōngzhèng). By adopting the name Chung-cheng ("central uprightness"), he was choosing a name very similar to the name of Sun Yat-sen, who was (and still is) known among Chinese as Zhongshan (中山—meaning "central mountain"), thus establishing a link between the two. The meaning of uprightness, rectitude, or orthodoxy, implied by his name, also positioned him as the legitimate heir of Sun Yat-sen and his ideas. It was readily accepted by members of the Chinese Nationalist Party and is the name under which Chiang Kai-shek is still commonly known in Taiwan. However, the name was often rejected by the Chinese Communists and is not as well known in mainland China. Often the name is shortened to "Chung-cheng" only ("Zhongzheng" in Pinyin). Many public places in Taiwan are named Chungcheng after Chiang. For many years passengers arriving at the Chiang Kai-shek International Airport were greeted by signs in Chinese welcoming them to the "Chung Cheng International Airport". Similarly, the monument erected to Chiang's memory in Taipei, known in English as Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall, was literally named "Chung Cheng Memorial Hall" in Chinese. In Singapore, Chung Cheng High School was named after him.

His name is also written in Taiwan as "The Late President Honorable Chiang" (先總統 蔣公), where the one-character-wide space in front of his name known as Nuo tai shows respect. He is often called Honorable Chiang (蔣公) (without the title or space).

In this context, his surname "Chiang" in this article is spelled using the Wade-Giles system of transliteration for Standard Chinese as opposed to Hanyu Pinyin (which is spelled as "Jiang")[8] though the latter was adopted by the ROC government in 2009 as its official romanization.

Early life

Chiang was born on 31 October 1887, in Xikou (Hsikow, Hsi-k'ou), a town in Fenghua (Fenghwa), Zhejiang (Chekiang), China,[9] about 30 kilometers (19 mi) west of central Ningbo. He was born into a family of Wu Chinese-speaking people with their ancestral home—a concept important in Chinese society—in Heqiao (和橋鎮), a town in Yixing, Jiangsu, about 38 km (24 mi) southwest of central Wuxi and 10 km (6.2 mi) from the shores of Lake Tai. He was the third child and second son of his father Chiang Chao-Tsung (also Chiang Su-an;[10] 1842–1895;[11] 蔣肇聰) and the first child of his father's third[7] wife Wang Tsai-yu (1863–1921;[10] 王采玉) who were members of a prosperous family of salt merchants. Chiang's father died when he was eight, and he wrote of his mother as the "embodiment of Confucian virtues". The young Chiang was inspired throughout his youth by the realisation that the reputation of an honored family rested upon his shoulders. He was a naughty child.[12] At a young age he was interested in war.[13] As he grew older, Chiang became more aware of the issues that surrounded him and in his speech to the Kuomintang in 1945 said:

As you all know I was an orphan boy in a poor family. Deprived of any protection after the death of her husband, my mother was exposed to the most ruthless exploitation by neighbouring ruffians and the local gentry. The efforts she made in fighting against the intrigues of these family intruders certainly endowed her child, brought up in such environment, with an indomitable spirit to fight for justice. I felt throughout my childhood that mother and I were fighting a helpless lone war. We were alone in a desert, no available or possible assistance could we look forward to. But our determination was never shaken, nor hope abandoned.[14]

In early 1906, Chiang cut off his queue, the required hairstyle of men during the Qing dynasty, and had it sent home from school, shocking the people in his hometown.[15]

Education in Japan

Chiang grew up at a time in which military defeats, natural disasters, famines, revolts, unequal treaties and civil wars had left the Manchu-dominated Qing dynasty destabilized and in debt. Successive demands of the Western powers and Japan since the Opium War had left China owing millions of taels of silver. During his first visit to Japan to pursue a military career from April 1906 to later that year, he describes himself having strong nationalistic feelings with a desire among other things to, 'expel the Manchu Qing and to restore China'.[16] In a 1969 speech, Chiang related a story about his boat trip to Japan at nineteen years old. Another passenger on the ship, a Chinese fellow student who was in the habit of spitting on the floor, was chided by a Chinese sailor who said that Japanese people did not spit on the floor, but instead would spit into a handkerchief. Chiang used the story as an example of how the common man in 1969 Taiwan had not developed the spirit of public sanitation that Japan had.[17] Chiang decided to pursue a military career. He began his military training at the Baoding Military Academy in 1906, the same year Japan left its bimetallic currency standard, devaluing its yen. He left for Tokyo Shinbu Gakko, a preparatory school for the Imperial Japanese Army Academy intended for Chinese students, in 1907. There, he came under the influence of compatriots to support the revolutionary movement to overthrow the Manchu-dominated Qing dynasty and to set up a Han-dominated Chinese republic. He befriended Chen Qimei, and in 1908 Chen brought Chiang into the Tongmenghui, an important revolutionary brotherhood of the era. Finishing his military schooling at Tokyo Shinbu Gakko, Chiang served in the Imperial Japanese Army from 1909 to 1911.

Returning to China

After learning of the Wuchang uprising, Chiang returned to China in 1911, intending to fight as an artillery officer. He served in the revolutionary forces, leading a regiment in Shanghai under his friend and mentor Chen Qimei, as one of Chen's chief lieutenants.[18] In early 1912 a dispute arose between Chen and Tao Chen-chang, an influential member of the Revolutionary Alliance who opposed both Sun Yat-sen and Chen. Tao sought to avoid escalating the quarrel by hiding in a hospital, but Chiang discovered him there. Chen dispatched assassins. Chiang may not have taken part in the assassination, but would later assume responsibility to help Chen avoid trouble. Chen valued Chiang despite Chiang's already legendary temper, regarding such bellicosity as useful in a military leader.[19]

Chiang's friendship with Chen Qimei signaled an association with Shanghai's criminal syndicate (the Green Gang headed by Du Yuesheng and Huang Jinrong). During Chiang's time in Shanghai, the Shanghai International Settlement police observed him and eventually charged him with various felonies. These charges never resulted in a trial, and Chiang was never jailed.[20]

Chiang became a founding member of the Nationalist Party (a forerunner of the KMT) after the success (February 1912) of the 1911 Revolution. After the takeover of the Republican government by Yuan Shikai and the failed Second Revolution in 1913, Chiang, like his KMT comrades, divided his time between exile in Japan and the havens of the Shanghai International Settlement. In Shanghai, Chiang cultivated ties with the city's underworld gangs, which were dominated by the notorious Green Gang and its leader Du Yuesheng. On 18 May 1916 agents of Yuan Shikai assassinated Chen Qimei. Chiang then succeeded Chen as leader of the Chinese Revolutionary Party in Shanghai. Sun Yat-sen's political career reached its lowest point during this time – most of his old Revolutionary Alliance comrades refused to join him in the exiled Chinese Revolutionary Party.[21]

Establishing the Kuomintang's position

In 1917, Sun Yat-sen moved his base of operations to Canton (now known as Guangzhou) and Chiang joined him in 1918. At this time Sun remained largely sidelined; without arms or money, he was soon expelled from Guangdong (Canton province) and exiled again to Shanghai. He was restored to Guangdong with mercenary help in 1920. After his return to Guangdong, a rift developed between Sun, who sought to militarily unify China under the KMT, and Guangdong Governor Chen Jiongming, who wanted to implement a federalist system with Guangdong as a model province. On 16 June 1922 Ye Ju, a general of Chen's whom Sun had attempted to exile, led an assault on Guangdong's Presidential Palace.[22] Sun had already fled to the naval yard[23] and boarded the SS Haiqi,[24] but his wife narrowly evaded shelling and rifle-fire as she fled.[25] They met on the SS Yongfeng, where Chiang joined them as swiftly as he could return from Shanghai, where he was ritually mourning his mother's death.[26] For about 50 days,[27] Chiang stayed with Sun, protecting and caring for him and earning his lasting trust. They abandoned their attacks on Chen on 9 August, taking a British ship to Hong Kong[26] and traveling to Shanghai by steamer.[27]

Sun regained control of Guangdong in early 1923, again with the help of mercenaries from Yunnan and of the Comintern. Undertaking a reform of the KMT, he established a revolutionary government aimed at unifying China under the KMT. That same year Sun sent Chiang to spend three months in Moscow studying the Soviet political and military system. During his trip in Russia, Chiang met Leon Trotsky and other Soviet leaders, but quickly came to the conclusion that the Russian model of government was not suitable for China. Chiang later sent his eldest son, Ching-kuo, to study in Russia. After his father's split from the First United Front in 1927, Ching-kuo was forced to stay there, as a hostage, until 1937. Chiang wrote in his diary, "It is not worth it to sacrifice the interest of the country for the sake of my son."[28][29] Chiang even refused to negotiate a prisoner swap for his son in exchange for the Chinese Communist Party leader.[30] His attitude remained consistent, and he continued to maintain, by 1937, that "I would rather have no offspring than sacrifice our nation's interests." Chiang had absolutely no intention of ceasing the war against the Communists.[31]

Chiang Kai-shek returned to Guangdong and in 1924 Sun appointed him Commandant of the Whampoa Military Academy. Chiang resigned from the office after one month in disagreement with Sun's extremely close cooperation with the Comintern, but returned at Sun's demand. The early years at Whampoa allowed Chiang to cultivate a cadre of young officers loyal both to the KMT and to himself.

Throughout his rise to power, Chiang also benefited from membership within the nationalist Tiandihui fraternity, to which Sun Yat-sen also belonged, and which remained a source of support during his leadership of the Kuomintang.[32]

Rising power

Sun Yat-sen died on 12 March 1925,[33] creating a power vacuum in the Kuomintang. A contest ensued among Wang Jingwei, Liao Zhongkai, and Hu Hanmin. In August, Liao was assassinated and Hu arrested for his connections to the murderers. Wang Jingwei, who had succeeded Sun as chairman of the Kwangtung regime, seemed ascendant but was forced into exile by Chiang following the Canton Coup. The SS Yongfeng, renamed the Zhongshan in Sun's honour, had appeared off Changzhou[34]—the location of the Whampoa Academy—on apparently falsified orders[35] and amid a series of unusual phone calls trying to ascertain Chiang's location.[36] He initially considered fleeing Kwangtung and even booked passage on a Japanese steamer, but then decided to use his military connections to declare martial law on 20 March 1926, and crack down on Communist and Soviet influence over the NRA, the military academy, and the party.[35] The right wing of the party supported him and Stalin—anxious to maintain Soviet influence in the area—had his lieutenants agree to Chiang's demands[37] regarding a reduced Communist presence in the KMT leadership in exchange for certain other concessions.[35] The rapid replacement of leadership enabled Chiang to effectively end civilian oversight of the military after 15 May, though his authority was somewhat limited[37] by the army's own regional composition and divided loyalties.

On 5 June 1926, he was named commander-in-chief of the National Revolutionary Army[38] and, on 27 July, he finally launched Sun's long-delayed Northern Expedition, aimed at conquering the northern warlords and bringing China together under the KMT.

The NRA branched into three divisions: to the west was the returned Wang Jingwei, who led a column to take Wuhan; Bai Chongxi's column went east to take Shanghai; Chiang himself led in the middle route, planning to take Nanjing before pressing ahead to capture Beijing. However, in January 1927, Wang Jingwei and his KMT leftist allies took the city of Wuhan amid much popular mobilization and fanfare. Allied with a number of Chinese Communists and advised by Soviet agent Mikhail Borodin, Wang declared the National Government as having moved to Wuhan. Having taken Nanjing in March (and briefly visited Shanghai, now under the control of his close ally Bai Chongxi), Chiang halted his campaign and prepared a violent break with Wang's leftist elements, which he believed threatened his control of the KMT.

In 1927, when he was setting up the Nationalist government in Nanjing, he was preoccupied with "the elevation of our leader Dr. Sun Yat-sen to the rank of 'Father of our Chinese Republic'. Dr. Sun worked for 40 years to lead our people in the Nationalist cause, and we cannot allow any other personality to usurp this honored position". He asked Chen Guofu to purchase a photograph that had been taken in Japan around 1895 or 1898. It showed members of the Revive China Society with Yeung Kui-wan (楊衢雲 or 杨衢云, pinyin Yáng Qúyún) as president, in the place of honor, and Sun, as secretary, on the back row, along with members of the Japanese Chapter of the Revive China Society. When told that it was not for sale, Chiang offered a million dollars to recover the photo and its negative. "The party must have this picture and the negative at any price. They must be destroyed as soon as possible. It would be embarrassing to have our Father of the Chinese Republic shown in a subordinate position".[39] Chiang never obtained either the photo or its negative.

On 12 April 1927, Chiang carried out a purge of thousands of suspected Communists and dissidents in Shanghai, and began large-scale massacres across the country collectively known as the "White Terror". During April, more than 12,000 people were killed in Shanghai. The killings drove most Communists from urban cities and into the rural countryside, where the KMT was less powerful.[40] In the year after April 1927, over 300,000 people died across China in the anti-Communist suppression campaigns, executed by the KMT. One of the most famous quotes from Chiang (during that time) was, that he would rather mistakenly kill 1,000 innocent people, than allow one Communist to escape.[41] Some estimates claim the White Terror in China took millions of lives, most of them in the rural areas. No concrete number can be verified.[42] Chiang allowed Soviet agent and advisor Mikhail Borodin and Soviet general Vasily Blücher (Galens) to "escape" to safety after the purge.[43]

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA) formed by the KMT swept through southern and central China until it was checked in Shandong, where confrontations with the Japanese garrison escalated into armed conflict. The conflicts were collectively known as the Jinan incident of 1928.

Now with an established national government in Nanjing, and supported by conservative allies including Hu Hanmin, Chiang's expulsion of the Communists and their Soviet advisers led to the beginning of the Chinese Civil War. Wang Jingwei's National Government was weak militarily, and was soon ended by Chiang with the support of a local warlord (Li Zongren of Guangxi). Eventually, Wang and his leftist party surrendered to Chiang and joined him in Nanjing. However, the cracks between Chiang and Hu Hanmin’s traditionally Right-Wing KMT faction, the Western Hills Group, began to show soon after the cleansing against the communists, and Chiang later imprisoned Hu.

Though Chiang had consolidated the power of the KMT in Nanking, it was still necessary to capture Beiping (Beijing) to claim the legitimacy needed for international recognition. Beijing was taken in June 1928, from an alliance of the warlords Feng Yuxiang and Yan Xishan. Yan Xishan moved in and captured Beiping on behalf of his new allegiance after the death of Zhang Zuolin in 1928. His successor, Zhang Xueliang, accepted the authority of the KMT leadership, and the Northern Expedition officially concluded, completing Chiang's nominal unification of China and ending the Warlord Era.

After the Northern Expedition ended in 1928, Yan Xishan, Feng Yuxiang, Li Zongren and Zhang Fakui broke off relations with Chiang shortly after a demilitarization conference in 1929, and together they formed an anti-Chiang coalition to openly challenge the legitimacy of the Nanjing government. In the Central Plains War, they were defeated.

Chiang made great efforts to gain recognition as the official successor of Sun Yat-sen. In a pairing of great political significance, Chiang was Sun's brother-in-law: he had married Soong Mei-ling, the younger sister of Soong Ching-ling, Sun's widow, on 1 December 1927. Originally rebuffed in the early 1920s, Chiang managed to ingratiate himself to some degree with Soong Mei-ling's mother by first divorcing his wife and concubines and promising to sincerely study the precepts of Christianity. He read the copy of the Bible that May-ling had given him twice before making up his mind to become a Christian, and three years after his marriage he was baptized in the Soong's Methodist church. Although some observers felt that he adopted Christianity as a political move, studies of his recently opened diaries suggest that his faith was strong and sincere and that he felt that Christianity reinforced Confucian moral teachings.[44]

Upon reaching Beijing, Chiang paid homage to Sun Yat-sen and had his body moved to the new capital of Nanjing to be enshrined in a mausoleum, the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum.

In the West and in the Soviet Union, Chiang Kai-shek was known as the "Red General".[45] Movie theaters in the Soviet Union showed newsreels and clips of Chiang. At Moscow, Sun Yat-sen University portraits of Chiang were hung on the walls; and, in the Soviet May Day Parades that year, Chiang's portrait was to be carried along with the portraits of Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, and other Communist leaders.[46] The United States consulate and other Westerners in Shanghai were concerned about the approach of "Red General" Chiang as his army was seizing control of large areas of the country in the Northern Expedition.[47][48]

Rule

Having gained control of China, Chiang's party remained surrounded by "surrendered" warlords who remained relatively autonomous within their own regions. On 10 October 1928, Chiang was named director of the State Council, the equivalent to President of the country, in addition to his other titles.[49] As with his predecessor Sun Yat-sen, the Western media dubbed him "Generalissimo".[38]

According to Sun Yat-sen's plans, the Kuomintang (KMT) was to rebuild China in three steps: military rule, political tutelage, and constitutional rule. The ultimate goal of the KMT revolution was democracy, which was not considered to be feasible in China's fragmented state. Since the KMT had completed the first step of revolution through seizure of power in 1928, Chiang's rule thus began a period of what his party considered to be "political tutelage" in Sun Yat-sen's name. During this so-called Republican Era, many features of a modern, functional Chinese state emerged and developed.

From 1928 to 1937, a time period known as the Nanjing decade, some aspects of foreign imperialism, concessions and privileges in China were moderated through diplomacy. The government acted to modernize the legal and penal systems, attempted to stabilize prices, amortize debts, reform the banking and currency systems, build railroads and highways, improve public health facilities, legislate against traffic in narcotics, and augment industrial and agricultural production. Efforts were made towards improving education standards, and the national academy of sciences, Academia Sinica, was founded.[50] In an effort to unify Chinese society, the New Life Movement was launched to encourage Confucian moral values and personal discipline. Guoyu ("national language") was promoted as a standard tongue, and the establishment of communications facilities (including radio) were used to encourage a sense of Chinese nationalism in a way that was not possible when the nation lacked an effective central government. Under this context, the Chinese Rural Reconstruction Movement was implemented by some social activists who graduated as professors of the United States with tangible but limited progress in modernizing the tax, infrastructural, economical, cultural, and educational equipment and mechanisms of rural regions. The social activists actively coordinated with the local governments in towns and villages since the early 1930s. However, this policy was subsequently neglected and canceled by Chiang’s government due to rampant wars and the lack of resources following the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Second Chinese Civil War.[51][52]

Despite being a conservative, Chiang supported modernization policies such as scientific advancement, universal education, and women’s rights. The Kuomintang and the Nationalist Government supported women’s suffrage and education and the abolition of polygamy and foot binding. The government of the Republic of China under Chiang’s leadership also enacted a women’s quota in the parliament with reserved seats for women. During the Nanjing Decade, average Chinese citizens received the education they’d never had the chance to get in the dynasties that increased the literacy rate across China. The education also promotes the ideals of Tridemism of democracy, republicanism, science, constitutionalism, and Chinese Nationalism based on the Political Tutelage of the Kuomintang.[53][54][55][56][57]

Any successes that the Nationalists did make, however, were met with constant political and military upheavals. While much of the urban areas were now under the control of the KMT, much of the countryside remained under the influence of weakened yet undefeated warlords and Communists. Chiang often resolved issues of warlord obstinacy through military action, but such action was costly in terms of men and material. The 1930 Central Plains War alone nearly bankrupted the Nationalist government and caused almost 250,000 casualties on both sides. In 1931, Hu Hanmin, Chiang's old supporter, publicly voiced a popular concern that Chiang's position as both premier and president flew in the face of the democratic ideals of the Nationalist government. Chiang had Hu put under house arrest, but he was released after national condemnation, after which he left Nanjing and supported a rival government in Canton. The split resulted in a military conflict between Hu's Kwangtung government and Chiang's Nationalist government. Chiang only won the campaign against Hu after a shift in allegiance by Zhang Xueliang, who had previously supported Hu Hanmin.

Throughout his rule, complete eradication of the Communists remained Chiang's dream. After assembling his forces in Jiangxi, Chiang led his armies against the newly established Chinese Soviet Republic. With help from foreign military advisers such as Max Bauer and Alexander von Falkenhausen, Chiang's Fifth Campaign finally surrounded the Chinese Red Army in 1934.[58] The Communists, tipped off that a Nationalist offensive was imminent, retreated in the Long March, during which Mao Zedong rose from a mere military official to the most influential leader of the Chinese Communist Party.

Chiang, as a nationalist and a Confucianist, was against the iconoclasm of the May Fourth Movement. Motivated by his sense of nationalism, he viewed some Western ideas as foreign, and he believed that the great introduction of Western ideas and literature that the May Fourth Movement promoted was not beneficial to China. He and Dr. Sun criticized the May Fourth intellectuals as corrupting the morals of China's youth.[59]

Some have classified his rule as fascist.[60][61] The New Life Movement which was initiated by Chiang was based upon Confucianism, mixed with Christianity, nationalism and authoritarianism that have some similarities to fascism. Frederic Wakeman suggested that the New Life Movement was "Confucian fascism".[62] Under Chiang's rule, there also existed the Blue Shirts Society, which was largely modelled on those of the Blackshirts in the National Fascist Party and the Sturmabteilung of the Nazi Party.[63] Its ideology was to expel foreign (Japanese and Western) imperialists from China and to crush communism.[64] Close Sino-German ties also promoted cooperation between the Kuomintang and the Weimar German government and later Hitler’s Nazi regime. However, Chiang repeatedly attacked his enemies such as the Empire of Japan as fascistic and ultra-militaristic.[65][66] The Sino-German relationship also rapidly deteriorated as Germany failed to pursue a detente between China and Japan, which led to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. China later declared war on fascist countries, including Germany, Italy, and Japan, as part of Declarations of war during World War II.

Contrary to Communist propaganda that he was pro-capitalism, Chiang antagonized the capitalists of Shanghai, often attacking them and confiscating their capital and assets for the use of the government. Chiang confiscated the wealth of capitalists even while he denounced and fought against communists.[67] Chiang crushed pro-communist worker and peasant organizations and rich Shanghai capitalists at the same time. Chiang continued the anti-capitalist ideology of Sun Yat-sen, directing Kuomintang media to openly attack capitalists and capitalism, while demanding government controlled industry instead.[68] Also, contrary to communist propaganda that Chiang was highly corrupt, he and his family were not involved in corruption. Chiang and his son lived plain lives, and his wife Soong Mei-ling only had 120 thousand USD as the inheritance when she died in the US with no real estate. One of Chiang’s grandsons even struggles to make a living, which surprised a Taiwanese Mayor. Chiang Ching-kuo’s Belarusian wife also struggled to make a living in her late life. She only inherited 1.152 million New Taiwan (USD 38.5 thousand) of her husband's salary. However, Chiang was rather benevolent to people in his inner circles or high-ranking nationalist officials who were corrupt.[69]

Chiang has often been interpreted as being pro-capitalism, but this conclusion is problematic. Shanghai capitalists did briefly support him out of fear of communism in 1927, but this support eroded in 1928 when Chiang turned his tactics of intimidation on them. The relationship between Chiang Kai-shek and Chinese capitalists remained poor throughout the period of his administration.[70] Chiang blocked Chinese capitalists from gaining any political power or voice within his regime. Once Chiang Kai-shek was done with his White Terror on pro-communist laborers, he proceeded to turn on the capitalists. Gangster connections allowed Chiang to attack them in the International Settlement, successfully forcing capitalists to back him up with their assets for his military expeditions.[70]

Chiang viewed all of the foreign great powers with suspicion, writing in a letter that they "all have it in their minds to promote the interests of their own respective countries at the cost of other nations" and seeing it as hypocritical for any of them to condemn each other's foreign policy.[71][72] He used diplomatic persuasion on the United States, Germany, and the Soviet Union to regain lost Chinese territories as he viewed all foreign powers as imperialists who were attempting to curtail and suppress China's power.[73]

Mass deaths under Nationalist rule

Some sources blame Chiang Kai-shek for the millions of deaths in scattered events caused by the Nationalist Government of China. However Rudolph Rummel, puts some of the responsibility on the Nationalist regime as whole rather than all on Chiang Kai-Shek in particular. Rummel writes that from its founding down to its defeat in 1949, the Nationalist government probably killed between roughly 6 and 18.5 million people. The major causes include:[74]

- Thousands of communists and communist sympathizers killed during and in the year after the 1927 Shanghai massacre.

- In 1938, to stop Japanese advance Chiang ordered the Yellow River dikes to be breached. An official postwar commission estimated that the total number of those who perished from malnutrition, famine, disease, or drowning might be as high as 800,000.[75]

- In 1943, 1.75 to 2.5 million Henan civilians starved to death due to grain being confiscated and sold for the profit of Nationalist government officials.

- 4,212,000 Chinese perished during the Second Sino-Japanese War and Civil War starving to death or dying from disease during conscription campaigns.[76]

First phase of the Chinese Civil War

.jpg.webp)

In Nanjing, in April 1931, Chiang Kai-shek attended a national leadership conference with Zhang Xueliang and General Ma Fuxiang, in which Chiang and Zhang dauntlessly upheld that Manchuria was part of China in the face of the Japanese invasion.[77] After the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, Chiang resigned as Chairman of the National Government. He returned shortly afterwards, adopting the slogan "first internal pacification, then external resistance". However, this policy of avoiding a frontal war against the Japanese was widely unpopular. In 1932, while Chiang was seeking first to defeat the Communists, Japan launched an advance on Shanghai and bombarded Nanjing. This disrupted Chiang's offensives against the Communists for a time, although it was the northern factions of Hu Hanmin's Kwangtung government (notably the 19th Route Army) that primarily led the offensive against the Japanese during this skirmish. Brought into the Nationalist army immediately after the battle, the 19th Route Army's career under Chiang would be cut short after it was disbanded for demonstrating socialist tendencies.

In December 1936, Chiang flew to Xi'an to coordinate a major assault on the Red Army and the Communist Republic that had retreated into Yan'an. However, Chiang's allied commander Zhang Xueliang, whose forces were used in his attack and whose homeland of Manchuria had been recently invaded by the Japanese, did not support the attack on the Communists. On 12 December, Zhang and several other Nationalist generals headed by Yang Hucheng of Shaanxi kidnapped Chiang for two weeks in what is known as the Xi'an Incident. They forced Chiang into making a "Second United Front" with the Communists against Japan. After releasing Chiang and returning to Nanjing with him, Zhang was placed under house arrest and the generals who had assisted him were executed. Chiang's commitment to the Second United Front was nominal at best, and it was all but broken up in 1941.

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War broke out in July 1937, and in August of that year Chiang sent 600,000 of his best-trained and equipped soldiers to defend Shanghai. With over 200,000 Chinese casualties, Chiang lost the political cream of his Whampoa-trained officers. Although Chiang lost militarily, the battle dispelled Japanese claims that it could conquer China in three months and demonstrated to the Western powers that the Chinese would continue the fight. By December, the capital city of Nanjing had fallen to the Japanese resulting in the Nanking massacre. Chiang moved the government inland, first to Wuhan and later to Chongqing.

Having lost most of China's economic and industrial centers, Chiang withdrew into the hinterlands, stretching the Japanese supply lines and bogging down Japanese soldiers in the vast Chinese interior. As part of a policy of protracted resistance, Chiang authorized the use of scorched earth tactics, resulting in many civilian deaths. During the Nationalists' retreat from Zhengzhou, the dams around the city were deliberately destroyed by the Nationalist army to delay the Japanese advance, killing 500,000 people in the subsequent 1938 Yellow River flood.

After heavy fighting, the Japanese occupied Wuhan in the fall of 1938 and the Nationalists retreated farther inland, to Chongqing. While en route to Chongqing, the Nationalist army intentionally started the "fire of Changsha", as a part of the scorched earth policy. The fire destroyed much of the city, killed twenty thousand civilians, and left hundreds of thousands of people homeless. Due to an organizational error (it was claimed), the fire was begun without any warning to the residents of the city. The Nationalists eventually blamed three local commanders for the fire and executed them. Newspapers across China blamed the fire on (non-KMT) arsonists, but the blaze contributed to a nationwide loss of support for the KMT.[78]

In 1939 Muslim leaders Isa Yusuf Alptekin and Ma Fuliang were sent by Chiang to several Middle Eastern countries, including Egypt, Turkey, and Syria, to gain support for the Chinese War against Japan, and to express his support for Muslims.[79]

The Japanese, controlling the puppet-state of Manchukuo and much of China's eastern seaboard, appointed Wang Jingwei as a Quisling-ruler of the occupied Chinese territories around Nanjing. Wang named himself President of the Executive Yuan and Chairman of the National Government (not the same 'National Government' as Chiang's), and led a surprisingly large minority of anti-Chiang/anti-Communist Chinese against his old comrades. He died in 1944, within a year of the end of World War II.

The Hui Muslim Xidaotang sect pledged allegiance to the Kuomintang after their rise to power and Hui Muslim General Bai Chongxi acquainted Chiang Kaishek with the Xidaotang jiaozhu Ma Mingren in 1941 in Chongqing.[80]

In 1942 Chiang went on tour in northwestern China in Xinjiang, Gansu, Ningxia, Shaanxi, and Qinghai, where he met both Muslim Generals Ma Buqing and Ma Bufang.[81] He also met the Muslim Generals Ma Hongbin and Ma Hongkui separately.

A border crisis erupted with Tibet in 1942. Under orders from Chiang, Ma Bufang repaired Yushu airport to prevent Tibetan separatists from seeking independence.[82] Chiang also ordered Ma Bufang to put his Muslim soldiers on alert for an invasion of Tibet in 1942.[83] Ma Bufang complied and moved several thousand troops to the border with Tibet.[84] Chiang also threatened the Tibetans with aerial bombardment if they worked with the Japanese. Ma Bufang attacked the Tibetan Buddhist Tsang monastery in 1941.[85] He also constantly attacked the Labrang Monastery.[86]

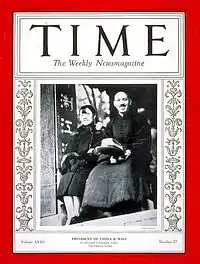

With the attack on Pearl Harbor and the opening of the Pacific War, China became one of the Allied Powers. During and after World War II, Chiang and his American-educated wife Soong Mei-ling, known in the United States as "Madame Chiang", held the support of the China Lobby in the United States, which saw in them the hope of a Christian and democratic China. Chiang was even named the Supreme Commander of Allied forces in the China war zone. He was appointed Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in 1942.[87]

General Joseph Stilwell, an American military adviser to Chiang during World War II, strongly criticized Chiang and his generals for what he saw as their incompetence and corruption.[88] In 1944, the United States Army Air Corps commenced Operation Matterhorn to bomb Japan's steel industry from bases to be constructed in mainland China. This was meant to fulfill President Roosevelt's promise to Chiang Kai-shek to begin bombing operations against Japan by November 1944. However, Chiang Kai-shek's subordinates refused to take airbase construction seriously until enough capital had been delivered to permit embezzlement on a massive scale. Stilwell estimated that at least half of the $100 million spent on construction of airbases was embezzled by Nationalist party officials.[89]

Chiang played the Soviets and Americans against each other during the war. He first told the Americans that they would be welcome in talks between the Soviet Union and China, then secretly told the Soviets that the Americans were unimportant and that their opinions would not be considered. Chiang also used American support and military power in China against the ambitions of the Soviet Union to dominate the talks, stopping the Soviets from taking full advantage of the situation in China with the threat of American military action against the Soviets.[90]

French Indochina

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, through General Stilwell, privately made it clear that they preferred that the French not reacquire French Indochina (modern day Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos) after the war was over. Roosevelt offered Chiang control of all of Indochina. It was said that Chiang replied: "Under no circumstances!"[91]

After the war, 200,000 Chinese troops under General Lu Han were sent by Chiang Kai-shek to northern Indochina (north of the 16th parallel) to accept the surrender of Japanese occupying forces there, and remained in Indochina until 1946, when the French returned.[92][93] The Chinese used the VNQDD, the Vietnamese branch of the Chinese Kuomintang, to increase their influence in Indochina and to put pressure on their opponents.[94] Chiang Kai-shek threatened the French with war in response to maneuvering by the French and Ho Chi Minh's forces against each other, forcing them to come to a peace agreement. In February 1946 he also forced the French to surrender all of their concessions in China and to renounce their extraterritorial privileges in exchange for the Chinese withdrawing from northern Indochina and allowing French troops to reoccupy the region. Following France's agreement to these demands, the withdrawal of Chinese troops began in March 1946.[95][96][97][98]

Ryukyus

During the Cairo Conference in 1943, Chiang said that Roosevelt asked him whether China would like to claim the Ryukyu Islands from Japan in addition to retaking Taiwan, the Pescadores, and Manchuria. Chiang claims that he said he was in favor of an international presence on the islands.[99] However, the U.S. became the occupier of the Ryukyus in 1945 until 1971, when Kishi successfully negotiated with Nixon to sign the Okinawa reversion agreement and return Okinawa to Japan.

Second phase of the Chinese Civil War

Treatment and use of Japanese soldiers

In 1945, when Japan surrendered, Chiang's Chongqing government was ill-equipped and ill-prepared to reassert its authority in formerly Japanese-occupied China, and it asked the Japanese to postpone their surrender until Kuomintang (KMT) authority could arrive to take over. American troops and weapons soon bolstered KMT forces, allowing them to reclaim cities. The countryside, however, remained largely under Communist control. Chiang implemented his war-time phrase "repay evil with good" and made a huge effort to protect elements of the Japanese invading army.[100] A Nationalist Chinese court acquitted the Chief Commander of Japanese forces in China, General Okamura Yasuji in 1949, of alleged war crimes[100] and retained him as an advisor to the Nationalist government.[101] Nationalist China repeatedly intervened to protect Okamura from repeated American requests that he testify at the Tokyo war crimes trial.[100]

For over a year after the Japanese surrender, rumors circulated throughout China that the Japanese had entered into a secret agreement with Chiang, in which the Japanese would assist the Nationalists in fighting the Communists in exchange for the protection of Japanese persons and property there. Many top nationalist generals, including Chiang, had studied and trained in Japan before the Nationalists had returned to the mainland in the 1920s, and maintained close personal friendships with top Japanese officers. The Japanese general in charge of all forces in China, General Yasuji Okamura, had personally trained officers who later became generals in Chiang's staff. Reportedly, General Okamura, before surrendering command of all Japanese military forces in Nanjing, offered Chiang control of all 1.5 million Japanese military and civilian support staff then present in China. Reportedly, Chiang seriously considered accepting this offer, but declined only in the knowledge that the United States would certainly be outraged by the gesture. Even so, armed Japanese troops remained in China well into 1947, with some noncommissioned officers finding their way into the Nationalist officer corps.[102] That the Japanese in China came to regard Chiang as a magnanimous figure, to whom many Japanese owed their lives and livelihoods was a fact attested by both Nationalist and Communist sources.[103]

Conditions during the Chinese Civil War

Westad says the Communists won the Civil War because they made fewer military mistakes than Chiang Kai-Shek, and because in his search for a powerful centralized government, Chiang antagonized too many interest groups in China. Furthermore, his party was weakened in the war against Japan. Meanwhile, the Communists told different groups, such as peasants, exactly what they wanted to hear, and cloaked themselves in the cover of Chinese Nationalism.[104]

Following the war, the United States encouraged peace talks between Chiang and Communist leader Mao Zedong in Chongqing. Due to concerns about widespread and well-documented corruption in Chiang's government throughout his rule, the U.S. government limited aid to Chiang for much of the period of 1946 to 1948, in the midst of fighting against the People's Liberation Army led by Mao Zedong. Alleged infiltration of the U.S. government by Chinese Communist agents may have also played a role in the suspension of American aid.[105]

Chiang's right-hand man, the secret police Chief Dai Li, was both anti-American and anti-Communist.[106] Dai ordered Kuomintang agents to spy on American officers.[107] Earlier, Dai had been involved with the Blue Shirts Society, a fascist-inspired paramilitary group within the Kuomintang, which wanted to expel Western and Japanese imperialists, crush the Communists, and eliminate feudalism.[108] Dai Li died in a plane crash, which while some suspect to be an assassination orchestrated by Chiang,[109] the assassination was also rumoured to have been arranged by the American Office of Strategic Services due to Dai's anti-Americanism, because it happened on an American plane.[110]

Although Chiang had achieved status abroad as a world leader, his government deteriorated as the result of corruption and inflation. In his diary in June 1948, Chiang wrote that the KMT had failed, not because of external enemies but because of rot from within.[111] The war had severely weakened the Nationalists, while the Communists were strengthened by their popular land-reform policies,[112] and by a rural population that supported and trusted them. The Nationalists initially had superiority in arms and men, but their lack of popularity, infiltration by Communist agents, low morale, and disorganization soon allowed the Communists to gain the upper hand in the civil war.

Competition with Li Zongren

A new Constitution was promulgated in 1947, and Chiang was elected by the National Assembly as the first term President of the Republic of China on 20 May 1948. This marked the beginning of what was termed the "democratic constitutional government" period by the KMT political orthodoxy, but the Communists refused to recognize the new Constitution, and its government, as legitimate. Chiang resigned as president on 21 January 1949, as KMT forces suffered terrible losses and defections to the Communists. After Chiang's resignation the vice-president of the ROC, Li Zongren, became China's acting president.[113]

Shortly after Chiang's resignation the Communists halted their advances and attempted to negotiate the virtual surrender of the ROC. Li attempted to negotiate milder terms that would have ended the civil war, but without success. When it became clear that Li was unlikely to accept Mao's terms, the Communists issued an ultimatum in April 1949, warning that they would resume their attacks if Li did not agree within five days. Li refused.[114]

Li's attempts to carry out his policies faced varying degrees of opposition from Chiang's supporters, and were generally unsuccessful. Chiang especially antagonized Li by taking possession of (and moving to Taiwan) US$200 million of gold and US dollars belonging to the central government that Li desperately needed to cover the government's soaring expenses. When the Communists captured the Nationalist capital of Nanjing in April 1949, Li refused to accompany the central government as it fled to Guangdong, instead expressing his dissatisfaction with Chiang by retiring to Guangxi.[115]

The former warlord Yan Xishan, who had fled to Nanjing only one month before, quickly insinuated himself within the Li-Chiang rivalry, attempting to have Li and Chiang reconcile their differences in the effort to resist the Communists. At Chiang's request Yan visited Li to convince Li not to withdraw from public life. Yan broke down in tears while talking of the loss of his home province of Shanxi to the Communists, and warned Li that the Nationalist cause was doomed unless Li went to Guangdong. Li agreed to return under the condition that Chiang surrender most of the gold and US dollars in his possession that belonged to the central government, and that Chiang stop overriding Li's authority. After Yan communicated these demands and Chiang agreed to comply with them, Li departed for Guangdong.[115]

In Guangdong, Li attempted to create a new government composed of both Chiang supporters and those opposed to Chiang. Li's first choice of premier was Chu Cheng, a veteran member of the Kuomintang who had been virtually driven into exile due to his strong opposition to Chiang. After the Legislative Yuan rejected Chu, Li was obliged to choose Yan Xishan instead. By this time Yan was well known for his adaptability and Chiang welcomed his appointment.[115]

Conflict between Chiang and Li persisted. Although he had agreed to do so as a prerequisite of Li's return, Chiang refused to surrender more than a fraction of the wealth that he had sent to Taiwan. Without being backed by gold or foreign currency, the money issued by Li and Yan quickly declined in value until it became virtually worthless.[116] Although he did not hold a formal executive position in the government, Chiang continued to issue orders to the army, and many officers continued to obey Chiang rather than Li. The inability of Li to coordinate KMT military forces led him to put into effect a plan of defense that he had contemplated in 1948. Instead of attempting to defend all of southern China, Li ordered what remained of the Nationalist armies to withdraw to Guangxi and Guangdong, hoping that he could concentrate all available defenses on this smaller, and more easily defensible, area. The object of Li's strategy was to maintain a foothold on the Chinese mainland in the hope that the United States would eventually be compelled to enter the war in China on the Nationalist side.[116]

Final Communist advance

.png.webp)

Chiang opposed Li's plan of defense because it would have placed most of the troops still loyal to Chiang under the control of Li and Chiang's other opponents in the central government. To overcome Chiang's intransigence Li began ousting Chiang's supporters within the central government. Yan Xishan continued in his attempts to work with both sides, creating the impression among Li's supporters that he was a "stooge" of Chiang, while those who supported Chiang began to bitterly resent Yan for his willingness to work with Li. Because of the rivalry between Chiang and Li, Chiang refused to allow Nationalist troops loyal to him to aid in the defense of Kwangsi and Canton, with the result that Communist forces occupied Canton in October 1949.[117]

After Canton fell to the Communists, Chiang relocated the government to Chongqing, while Li effectively surrendered his powers and flew to New York for treatment of his chronic duodenum illness at the Hospital of Columbia University. Li visited the President of the United States, Harry S. Truman, and denounced Chiang as a dictator and an usurper. Li vowed that he would "return to crush" Chiang once he returned to China. Li remained in exile, and did not return to Taiwan.[118]

In the early morning of 10 December 1949, Communist troops laid siege to Chengdu, the last KMT-controlled city in mainland China, where Chiang Kai-shek and his son Chiang Ching-kuo directed the defense at the Chengtu Central Military Academy. Flying out of Chengdu Fenghuangshan Airport, Chiang Kai-shek, father and son, were evacuated to Taiwan via Guangdong on an aircraft called May-ling and arrived the same day. Chiang Kai-shek would never return to the mainland.[119]

Chiang did not re-assume the presidency until 1 March 1950. In January 1952, Chiang commanded the Control Yuan, now in Taiwan, to impeach Li in the "Case of Li Zongren's Failure to carry out Duties due to Illegal Conduct" (李宗仁違法失職案). Chiang relieved Li of the position as vice-president in the National Assembly in March 1954.

On Taiwan

Preparations to retake the mainland

Chiang moved the government to Taipei, Taiwan, where he resumed his duties as President of the Republic of China on 1 March 1950.[120] Chiang was reelected by the National Assembly to be the President of the Republic of China (ROC) on 20 May 1954, and again in 1960, 1966, and 1972. He continued to claim sovereignty over all of China, including the territories held by his government and the People's Republic, as well as territory the latter ceded to foreign governments, such as Tuva and Outer Mongolia. In the context of the Cold War, most of the Western world recognized this position and the ROC represented China in the United Nations and other international organizations until the 1970s.

During his presidency on Taiwan, Chiang continued making preparations to take back mainland China. He developed the ROC army to prepare for an invasion of the mainland, and to defend Taiwan in case of an attack by the Communist forces. He also financed armed groups in mainland China, such as Muslim soldiers of the ROC Army left in Yunnan under Li Mi, who continued to fight. It was not until the 1980s that these troops were finally airlifted to Taiwan.[121] He promoted the Uyghur Yulbars Khan to Governor during the Islamic insurgency on the mainland for resisting the Communists, even though the government had already evacuated to Taiwan.[122] He planned an invasion of the mainland in 1962.[123] In the 1950s Chiang's airplanes dropped supplies to Kuomintang Muslim insurgents in Amdo.[124]

Regime

Despite the democratic constitution, the government under Chiang was a one-party state, consisting almost completely of mainlanders; the "Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion" greatly enhanced executive powers, and the goal of retaking mainland China allowed the KMT to maintain a monopoly on power and the prohibition of opposition parties. The government's official line for these martial law provisions stemmed from the claim that emergency provisions were necessary, since the Communists and KMT were still in a state of war. Seeking to promote Chinese nationalism, Chiang's government actively ignored and suppressed local cultural expression, even forbidding the use of local languages in mass media broadcasts or during class sessions. As a result of Taiwan's anti-government uprising in 1947, known as the February 28 incident, the KMT-led political repression resulted in the death or disappearance of over 30,000 Taiwanese intellectuals, activists, and people suspected of opposition to the KMT.[125]

The first decades after the Nationalists moved the seat of government to the province of Taiwan are associated with the organized effort to resist Communism known as the "White Terror", during which about 140,000 Taiwanese were imprisoned for their real or perceived opposition to the Kuomintang.[126] Most of those prosecuted were labeled by the Kuomintang as "bandit spies" (匪諜), meaning spies for Chinese Communists, and punished as such.

Under Chiang, the government recognized limited civil liberties, economic freedoms, property rights (personal and intellectual) and other liberties. Despite these restrictions, free debate within the confines of the legislature was permitted. Under the pretext that new elections could not be held in Communist-occupied constituencies, the National Assembly, Legislative Yuan, and Control Yuan members held their posts indefinitely. The Temporary Provisions also allowed Chiang to remain as president beyond the two-term limit in the Constitution. He was reelected by the National Assembly as president four times—doing so in 1954, 1960, 1966, and 1972.[127]

Believing that corruption and a lack of morals were key reasons that the KMT lost mainland China to the Communists, Chiang attempted to purge corruption by dismissing members of the KMT accused of graft. Some major figures in the previous mainland Chinese government, such as Chiang's brothers-in-law H. H. Kung and T. V. Soong, exiled themselves to the United States. Although politically authoritarian and, to some extent, dominated by government-owned industries, Chiang's new Taiwanese state also encouraged economic development, especially in the export sector. A popular sweeping Land Reform Act, as well as American foreign aid during the 1950s, laid the foundation for Taiwan's economic success, becoming one of the Four Asian Tigers. After retreating to Taiwan, Chiang learned from his mistakes and failures in the mainland and blamed them for failing to pursue Sun Yat-sen’s ideals of Tridemism and welfarism. Chiang’s land reform more than doubled the land ownership of Taiwanese farmers. It removed the rent burdens on them, with former land owners using the government compensation to become the new capitalist class. He promoted a mixed economy of state and private ownership with economic planning. Chiang also promoted a 9-years free education and the importance of science in Taiwanese education and values. These measures generated great success with consistent and strong growth and the stabilization of inflation.[128]

Chiang personally had the power to review the rulings of all military tribunals which during the martial law period tried civilians as well. In 1950 Lin Pang-chun and two other men were arrested on charges of financial crimes and sentenced to 3–10 years in prison. Chiang reviewed the sentences of all three and ordered them executed instead. In 1954 Changhua monk Kao Chih-te and two others were sentenced to 12 years in prison for providing aid to accused communists, Chiang sentenced them to death after reviewing the case. This control over the decision of military tribunals violated the ROC constitution.[129]

After Chiang's death, the next president, his son, Chiang Ching-kuo, and Chiang Ching-kuo's successor, Lee Teng-hui, a native Taiwanese, would in the 1980s and 1990s increase native Taiwanese representation in the government and loosen the many authoritarian controls of the early era of ROC control in Taiwan.

Relationship with Japan

In 1971, the Australian Opposition Leader Gough Whitlam, who became Prime Minister in 1972 and swiftly relocated the Australian mission from Taipei to Beijing, visited Japan. After meeting with the Japanese Prime Minister, Eisaku Sato, Whitlam observed that the reason Japan at that time was hesitant to withdraw recognition from the Nationalist government was "the presence of a treaty between the Japanese government and that of Chiang Kai-shek". Sato explained that the continued recognition of Japan towards the Nationalist government was due largely to the personal relationship that various members of the Japanese government felt towards Chiang. This relationship was rooted largely in the generous and lenient treatment of Japanese prisoners-of-war by the Nationalist government in the years immediately following the Japanese surrender in 1945, and was felt especially strongly as a bond of personal obligation by the most senior members then in power.[130]

Although Japan recognized the People's Republic in 1972, shortly after Kakuei Tanaka succeeded Sato as Prime Minister of Japan, the memory of this relationship was strong enough to be reported by The New York Times (15 April 1978) as a significant factor inhibiting trade between Japan and the mainland. There is speculation that a clash between Communist forces and a Japanese warship in 1978 was caused by Chinese anger after Prime Minister Takeo Fukuda attended Chiang's funeral. Historically, Japanese attempts to normalize their relationship with the People's Republic were met with accusations of ingratitude in Taiwan.[130]

Relationship with the United States

.jpg.webp)

Chiang was suspicious that covert operatives of the United States plotted a coup against him.

In 1950, Chiang Ching-kuo became director of the secret police (Bureau of Investigation and Statistics), which he remained until 1965. Chiang was also suspicious of politicians who were overly friendly to the United States, and considered them his enemies. In 1953, seven days after surviving an assassination attempt, Wu Kuo-chen lost his position as governor of Taiwan Province to Chiang Ching-kuo. After fleeing to United States the same year, he became a vocal critic of Chiang's family and government.[131]

Chiang Ching-kuo, educated in the Soviet Union, initiated Soviet-style military organization in the Republic of China Military. He reorganized and Sovietized the political officer corps, and propagated Kuomintang ideology throughout the military. Sun Li-jen, who was educated at the American Virginia Military Institute, was opposed to this.[132]

Chiang Ching-kuo orchestrated the controversial court-martial and arrest of General Sun Li-jen in August 1955, for plotting a coup d'état with the American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) against his father Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang. The CIA allegedly wanted to help Sun take control of Taiwan and declare its independence.[131][133]

Death

In 1975, 26 years after Chiang came to Taiwan, he died in Taipei at the age of 87.[134] He had suffered a heart attack and pneumonia in the foregoing months and died from renal failure aggravated with advanced cardiac failure on 5 April. Chiang's funeral was held on 16 April.[135]

A month of mourning was declared. Chinese music composer Hwang Yau-tai wrote the "Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Song". In mainland China, however, Chiang's death was met with little apparent mourning and Communist state-run newspapers gave the brief headline "Chiang Kai-shek Has Died". Chiang's body was put in a copper coffin and temporarily interred at his favorite residence in Cihu, Daxi, Taoyuan. His funeral was attended by dignitaries from many nations, including US Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, South Korean Prime Minister Kim Jong-pil and two former Japanese prime ministers in Nobusuke Kishi and Eisaku Sato. Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Day (蔣公逝世紀念日) was established on 5 April. The memorial day was disestablished in 2007.

When his son Chiang Ching-kuo died in 1988, he was entombed in a separate mausoleum in nearby Touliao (頭寮). The hope was to have both buried at their birthplace in Fenghua if and when it was possible. In 2004, Chiang Fang-liang, the widow of Chiang Ching-kuo, asked that both father and son be buried at Wuzhi Mountain Military Cemetery in Xizhi, Taipei County (now New Taipei City). Chiang's ultimate funeral ceremony became a political battle between the wishes of the state and the wishes of his family.

Chiang was succeeded as president by Vice President Yen Chia-kan and as Kuomintang party ruler by his son Chiang Ching-kuo, who retired Chiang Kai-shek's title of Director-General and instead assumed the position of chairman. Yen's presidency was interim; Chiang Ching-kuo, who was the Premier, became president after Yen's term ended three years later.

Cult of personality

Chiang's portrait hung over Tiananmen Square before Mao's portrait was set up in its place.[136] People also put portraits of Chiang in their homes and in public on the streets.[137][138][139]

After his death, the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Song was written in 1988 to commemorate Chiang Kai-shek.

In Cihu, there are several statues of Chiang Kai-shek.

Chiang was popular among many people and dressed in plain, simple clothes, unlike contemporary Chinese warlords who dressed extravagantly.[140]

Quotes from the Quran and Hadith were used by Muslims in the Kuomintang-controlled Muslim publication, the Yuehua, to justify Chiang Kai-shek's rule over China.[141]

When the Muslim General and Warlord Ma Lin was interviewed, Ma Lin was described as having "high admiration for and unwavering loyalty to Chiang Kai-shek".[142]

In the Philippines, a school was named in his honour in 1939. Today, Chiang Kai-shek College is the largest educational institution for the Chinoy community in the country.

Philosophy

The Kuomintang used traditional Chinese religious ceremonies, and promulgated martyrdom in Chinese culture. Kuomintang ideology subserved and promulgated the view that the souls of Party martyrs who died fighting for the Kuomintang, the revolution, and the party founder Dr. Sun Yat-sen were sent to heaven. Chiang Kai-shek believed that these martyrs witnessed events on Earth from heaven after their deaths.[143][144][145][146]

Unlike Sun’s original Three Principles of the People ideology that was heavily influenced by Western enlightenment theorists such as Henry George, Abraham Lincoln, Russell, and Mill,[147] the traditional Chinese Confucian influence on Chiang’s ideology is much stronger. Chiang rejected the Western progressive ideologies of individualism, liberalism, and the cultural aspects of Marxism. Therefore, Chiangism is generally more culturally and socially conservative than Sun Yat-sen ideologically. Jay Taylor has described Chiang Kai-shek as a revolutionary nationalist and a “left-leaning Confucian-Jacobinist”.

When the Northern Expedition was complete, Kuomintang Generals led by Chiang Kai-shek paid tribute to Dr. Sun's soul in heaven with a sacrificial ceremony at the Xiangshan Temple in Beijing in July 1928. Among the Kuomintang Generals present were the Muslim Generals Bai Chongxi and Ma Fuxiang.[148]

Chiang Kai-shek considered both Han Chinese and all ethnic minorities of China, the Five Races Under One Union, as descendants of the Yellow Emperor, the mythical founder of the Chinese nation, and belonging to the Chinese Nation Zhonghua Minzu and he introduced this into Kuomintang ideology, which was propagated into the educational system of the Republic of China.[149][150][151]

Chiang Kai-shek once said:

If when I die, I am still a dictator, I will certainly go down into the oblivion of all dictators. If, on the other hand, I succeed in establishing a truly stable foundation for a democratic government, I will live forever in every home in China.[152]

Contemporary public perception