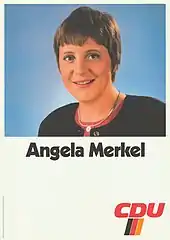

Angela Merkel

Angela Dorothea Merkel (German: [ˈaŋɡela doʁoˈteːa ˈmɛʁkl̩] (![]() listen);[lower-alpha 1] née Kasner; born 17 July 1954) is a German former politician and scientist who served as Chancellor of Germany from 2005 to 2021. A member of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), she previously served as Leader of the Opposition from 2002 to 2005 and as Leader of the Christian Democratic Union from 2000 to 2018.[9] Merkel was the first female chancellor of Germany.[10] During her tenure as Chancellor, Merkel was frequently referred to as the de facto leader of the European Union (EU), the most powerful woman in the world and since 2016 as the leader of the free world.[11][12][13][14][15]

listen);[lower-alpha 1] née Kasner; born 17 July 1954) is a German former politician and scientist who served as Chancellor of Germany from 2005 to 2021. A member of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), she previously served as Leader of the Opposition from 2002 to 2005 and as Leader of the Christian Democratic Union from 2000 to 2018.[9] Merkel was the first female chancellor of Germany.[10] During her tenure as Chancellor, Merkel was frequently referred to as the de facto leader of the European Union (EU), the most powerful woman in the world and since 2016 as the leader of the free world.[11][12][13][14][15]

Angela Merkel | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Merkel in 2019 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor of Germany | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 22 November 2005 – 8 December 2021 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice Chancellor | See list

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Gerhard Schröder | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Olaf Scholz | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Christian Democratic Union | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 April 2000 – 7 December 2018 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General Secretary | See list

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | See list

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Wolfgang Schäuble | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Opposition | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 22 September 2002 – 22 November 2005 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor | Gerhard Schröder | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Friedrich Merz | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Wolfgang Gerhardt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the CDU/CSU in the Bundestag | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 22 September 2002 – 21 November 2005 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First Deputy | Michael Glos | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chief Whip | Volker Kauder Norbert Röttgen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Friedrich Merz | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Volker Kauder | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Member of the Bundestag for Mecklenburg-Vorpommern | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 20 December 1990 – 26 October 2021 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Constituency established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Anna Kassautzki | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Constituency |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Angela Dorothea Kasner 17 July 1954 Hamburg, West Germany | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Christian Democratic Union (1990–present) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other political affiliations |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouses | Ulrich Merkel

(m. 1977; div. 1982)Joachim Sauer (m. 1998) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Residence(s) | Am Kupfergraben, Berlin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Awards | Order of Merit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | Official website | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific career | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thesis | Untersuchung des Mechanismus von Zerfallsreaktionen mit einfachem Bindungsbruch und Berechnung ihrer Geschwindigkeitskonstanten auf der Grundlage quantenchemischer und statistischer Methoden (1986) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Doctoral advisor | Lutz Zülicke | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||

|---|---|---|

Revolution of 1989

Kohl Administration

Leader of the Christian Democratic Union

First Ministry and term

Second Ministry and term

Third Ministry and term

Fourth Ministry and term

|

||

Merkel was born in Hamburg in then-West Germany, moving to East Germany as an infant when her father, a Lutheran clergyman, received a pastorate in Perleberg. She obtained a doctorate in quantum chemistry in 1986 and worked as a research scientist until 1989.[16] Merkel entered politics in the wake of the Revolutions of 1989, briefly serving as deputy spokeswoman for the first democratically elected Government of East Germany led by Lothar de Maizière. Following German reunification in 1990, Merkel was elected to the Bundestag for the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. As the protégée of Chancellor Helmut Kohl, Merkel was appointed as Minister for Women and Youth in 1991, later becoming Minister for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety in 1994. After the CDU lost the 1998 federal election, Merkel was elected CDU General Secretary, before becoming the party's first female leader and the first female Leader of the Opposition two years later, in the aftermath of a donations scandal that toppled Wolfgang Schäuble.

Following the 2005 federal election, Merkel was appointed to succeed Gerhard Schröder as Chancellor of Germany, leading a grand coalition consisting of the CDU, its Bavarian sister party the Christian Social Union (CSU) and the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). Merkel was the first woman to be elected as Chancellor, and the first Chancellor since reunification to have been raised in the former East Germany. At the 2009 federal election, the CDU obtained the largest share of the vote, and Merkel was able to form a coalition government with the Free Democratic Party (FDP).[17] At the 2013 federal election, Merkel's CDU won a landslide victory with 41.5% of the vote and formed a second grand coalition with the SPD, after the FDP lost all of its representation in the Bundestag.[18] At the 2017 federal election, Merkel led the CDU to become the largest party for the fourth time; Merkel formed a third grand coalition with the SPD and was sworn in for a joint-record fourth term as Chancellor on 14 March 2018.[19]

In foreign policy, Merkel has emphasised international cooperation, both in the context of the EU and NATO, and strengthening transatlantic economic relations. In 2008, Merkel served as President of the European Council and played a central role in the negotiation of the Treaty of Lisbon and the Berlin Declaration. Merkel played a crucial role in managing the global financial crisis of 2007–2008 and the European debt crisis. She negotiated the 2008 European Union stimulus plan focusing on infrastructure spending and public investment to counteract the Great Recession. In domestic policy, Merkel's Energiewende program has focused on future energy development, seeking to phase out nuclear power in Germany, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and increase renewable energy sources. Reforms to the Bundeswehr which abolished conscription, health care reform, and her government's response to the 2010s European migrant crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany were major issues during her chancellorship.[20] She served as the senior G7 leader from 2011 to 2012 and again from 2014 to 2021. In 2014, she became the longest-serving incumbent head of government in the EU. In October 2018, Merkel announced that she would stand down as Leader of the CDU at the party convention, and would not seek a fifth term as chancellor in the 2021 federal election.[21] In 2022, Merkel condemned the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Background and early life

Merkel was born Angela Dorothea Kasner in 1954, in Hamburg, West Germany, the daughter of Horst Kasner (1926–2011; né Kaźmierczak),[22][23] a Lutheran pastor and a native of Berlin, and his wife Herlind (1928–2019; née Jentzsch), born in Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland), a teacher of English and Latin. She has two younger siblings, Marcus Kasner, a physicist, and Irene Kasner, an occupational therapist. In her childhood and youth, Merkel was known among her peers by the nickname "Kasi", derived from her last name Kasner.[24]

Merkel is of German and Polish descent. Her paternal grandfather, Ludwik Kasner, was a German policeman of Polish ethnicity, who had taken part in Poland's struggle for independence in the early 20th century.[25] He married Merkel's grandmother Margarethe, a German from Berlin, and relocated to her hometown where he worked in the police. In 1930, they Germanized the Polish name Kaźmierczak to Kasner.[26][27][28][29] Merkel's maternal grandparents were the Danzig politician Willi Jentzsch, and Gertrud Alma (née Drange), a daughter of the city clerk of Elbing (now Elbląg, Poland) Emil Drange. Since the mid-1990s, Merkel has publicly mentioned her Polish heritage on several occasions and described herself as a quarter Polish, but her Polish roots became better known as a result of a 2013 biography.[30]

Religion played a key role in the Kasner family's migration from West Germany to East Germany.[31] Merkel's paternal grandfather was originally Catholic but the entire family converted to Lutheranism during the childhood of her father,[27] who later studied Lutheran theology in Heidelberg and Hamburg. In 1954, when Angela was just three months old, her father received a pastorate at the church in Quitzow (a quarter of Perleberg in Brandenburg), which was then in East Germany. The family moved to Templin and Merkel grew up in the countryside 90 km (56 mi) north of East Berlin.[32]

In 1968, Merkel joined the Free German Youth (FDJ), the official communist youth movement sponsored by the ruling Marxist–Leninist Socialist Unity Party of Germany.[33][34][35] Membership was nominally voluntary, but those who did not join found it difficult to gain admission to higher education.[36] She did not participate in the secular coming of age ceremony Jugendweihe, however, which was common in East Germany. Instead, she was confirmed.[37] During this time, she participated in several compulsory courses on Marxism-Leninism with her grades only being regarded as "sufficient".[38] Merkel later said that "Life in the GDR was sometimes almost comfortable in a certain way, because there were some things one simply couldn't influence."[39]

Education and scientific career

At school Merkel learned to speak Russian fluently, and was awarded prizes for her proficiency in Russian and mathematics. She was the best in her class in mathematics and Russian, and completed her school education with the best possible average Abitur grade 1.0.[40]

Merkel continued her education at Karl Marx University, Leipzig, where she studied physics from 1973 to 1978.[32] While a student, she participated in the reconstruction of the ruin of the Moritzbastei, a project students initiated to create their own club and recreation facility on campus. Such an initiative was unprecedented in the GDR of that period, and initially resisted by the university. With backing of the local leadership of the SED party, the project was allowed to proceed.[41]

Near the end of her studies, Merkel sought an assistant professorship at an engineering school. As a condition for getting the job, Merkel was told she would need to agree to report on her colleagues to officers of the Ministry for State Security (Stasi). Merkel declined, using the excuse that she could not keep secrets well enough to be an effective spy.[42]

Merkel worked and studied at the Central Institute for Physical Chemistry of the Academy of Sciences in Berlin-Adlershof from 1978 to 1990. At first she and her husband squatted in Mitte.[43] At the Academy of Sciences, she became a member of its FDJ secretariat. According to her former colleagues, she openly propagated Marxism as the secretary for "Agitation and Propaganda".[44] However, Merkel has denied this claim and stated that she was secretary for culture, which involved activities like obtaining theatre tickets and organising talks by visiting Soviet authors.[45] She stated: "I can only rely on my memory, if something turns out to be different, I can live with that."[44]

After being awarded a doctorate (Dr. rer. nat.) for her thesis on quantum chemistry in 1986,[46] she worked as a researcher and published several papers.[47] In 1986, she was able to travel freely to West Germany to attend a congress; she also participated in a multi-week language course in Donetsk, in the then-Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.[48]

Early political career

German reunification, 1989–1991

The fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 served as the catalyst for Merkel's political career. Although she did not participate in the crowd celebrations the night the wall came down, one month later Merkel became involved in the growing democracy movement, joining the new party Demokratischer Aufbruch (DA, or in English "Democratic Beginning").[49] Party Leader Wolfgang Schnur appointed her as press spokeswoman of the party in February 1990. However, Schnur was revealed to have served as an "informal co-worker" for the Stasi just a few weeks ahead of the first (and only) multi-party election in 1990 and was later expelled from the party. The DA sank as a result, only managing to elect four members to the Volkskammer. However, because the DA was a member party of the Alliance for Germany, which won the election in a landslide, the DA was included in the government coalition. Merkel was therefore appointed deputy spokesperson of the new and last pre-unification government under Lothar de Maizière.[50]

Merkel had impressed de Maizière with her adept dealing with journalists investigating Schnur's role in the Stasi.[42][49] In April 1990, DA merged with the East German Christian Democratic Union, which in turn merged with its western counterpart after reunification.

Minister for Women and Youth, 1991–1994

In the German federal election of 1990, the first to be held following reunification, Merkel successfully stood for election to the Bundestag in the parliamentary constituency of Stralsund – Nordvorpommern – Rügen in north Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.[51] She received the crucial backing of then-influential CDU minister and state party chairman Günther Krause. She has won re-election from this constituency (renamed, with slightly adjusted borders, Vorpommern-Rügen – Vorpommern-Greifswald I in 2003) at the seven federal elections held since then. Almost immediately following her entry into parliament, Merkel was appointed by Chancellor Helmut Kohl to serve as Minister for Women and Youth in the federal cabinet.[11][52] The ministry was the smallest and least powerful one of the three ministries that were created from the old Ministry for Health, Seniors, Family and Youth.

In November 1991, Merkel, with the support of the federal CDU, ran for the leadership of the neighboring CDU in Brandenburg. She lost to Ulf Finke; this has been the only election to date Merkel has lost.

In June 1993, Merkel was elected leader of the CDU in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, succeeding her former mentor Günther Krause.

Minister for Environment, 1994–1998

In 1994, she was promoted to the position of Minister for the Environment and Nuclear Safety, which gave her greater political visibility and a platform on which to build her personal political career. As one of Kohl's protégées and his youngest Cabinet Minister, she was frequently referred to by Kohl as mein Mädchen ("my girl").[53]

General Secretary of the CDU, 1998–2000

After the Kohl Government was defeated at the 1998 election, Merkel was appointed Secretary-General of the CDU,[52] a key position as the party was no longer part of the federal government. Merkel oversaw a string of CDU election victories in six out of seven state elections in 1999, breaking the long-standing SPD-Green hold on the Bundesrat. Following a party funding scandal that compromised many leading figures of the CDU – including Kohl himself and his successor as CDU Leader, Wolfgang Schäuble – Merkel criticised her former mentor publicly and advocated a fresh start for the party without him.[52]

Chairperson of the CDU, 2000–2018

She was subsequently elected to replace Schäuble, becoming the first female leader of a German party on 10 April 2000.[54] Her election surprised many observers, as her personality offered a contrast to the party she had been elected to lead; Merkel is a centrist Protestant originating from predominantly Protestant northern Germany, while the CDU is a male-dominated, socially conservative party with strongholds in western and southern Germany, and its Bavarian sister party, the CSU, has deep Catholic roots.

Following Merkel's election as CDU Leader, the CDU was not able to win in subsequent state elections. As early as February 2001 her rival Friedrich Merz had made clear he intended to become Chancellor Gerhard Schröder's main challenger in the 2002 election. Merkel's own ambition to become Chancellor was well-known, but she lacked the support of most Minister-presidents and other grandees within her own party. She was subsequently outmaneuvered politically by CSU Leader Edmund Stoiber, to whom she eventually ceded the privilege of challenging Schröder.[55] He went on to squander a large lead in opinion polls to lose the election by a razor-thin margin in an election campaign that was dominated by the Iraq War. While Chancellor Schröder made clear he would not join the war in Iraq,[56] Merkel and the CDU-CSU supported the invasion of Iraq.

Some successes

After Stoiber's defeat in 2002, in addition to her role as CDU Leader, Merkel became Leader of the Opposition in the Bundestag; Friedrich Merz, who had held the post prior to the 2002 election, was eased out to make way for Merkel. Stoiber voted for Merkel.[57]

Merkel supported a substantial reform agenda for Germany's economic and social system, and was considered more pro-market than her own party (the CDU). She advocated German labour law changes, specifically removing barriers to laying off employees and increasing the allowed number of work hours in a week. She argued that existing laws made the country less competitive, because companies could not easily control labour costs when business is slow.[58]

Merkel argued that Germany should phase out nuclear power less quickly than the Schröder administration had planned.[59][60]

Merkel advocated a strong transatlantic partnership and German-American friendship. In the spring of 2003, defying strong public opposition, Merkel came out in favour of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, describing it as "unavoidable" and accusing Chancellor Gerhard Schröder of anti-Americanism. She criticised the government's support for the accession of Turkey to the European Union and favoured a "privileged partnership" instead. In doing so, she reflected public opinion that grew more hostile toward Turkish membership of the European Union.[61]

2005 national election

On 30 May 2005, Merkel won the CDU/CSU nomination as challenger to Chancellor Gerhard Schröder of the SPD in the 2005 national elections. Her party began the campaign with a 21-point lead over the SPD in national opinion polls, although her personal popularity lagged behind that of the incumbent. However, the CDU/CSU campaign suffered[62] when Merkel, having made economic competence central to the CDU's platform, confused gross and net income twice during a televised debate.[63] She regained some momentum after she announced that she would appoint Paul Kirchhof, a former judge at the German Constitutional Court and leading fiscal policy expert, as Minister of Finance.[62]

Merkel and the CDU lost ground after Kirchhof proposed the introduction of a flat tax in Germany, again undermining the party's broad appeal on economic affairs and convincing many voters that the CDU's platform of deregulation was designed to benefit only the rich.[64] This was compounded by Merkel's proposal to increase VAT[65] to reduce Germany's deficit and fill the gap in revenue from a flat tax. The SPD were able to increase their support simply by pledging not to introduce flat taxes or increase VAT. Although Merkel's standing recovered after she distanced herself from Kirchhof's proposals, she remained considerably less popular than Schröder, and the CDU's lead was down to 9% on the eve of the election.[66]

On the eve of the election, Merkel was still favored to win a decisive victory based on opinion polls.[67] On 18 September 2005, Merkel's CDU/CSU and Schröder's SPD went head-to-head in the national elections, with the CDU/CSU winning 35.2% (CDU 27.8%/CSU 7.5%) of the second votes to the SPD's 34.2%.[67] The result was so close, both Schröder and Merkel claimed victory.[52][67] Neither the SPD-Green coalition nor the CDU/CSU and its preferred coalition partners, the Free Democratic Party, held enough seats to form a majority in the Bundestag.[67] A grand coalition between the CDU/CSU and SPD faced the challenge that both parties demanded the chancellorship.[67][68] However, after three weeks of negotiations, the two parties reached a deal whereby Merkel would become Chancellor and the SPD would hold 8 of the 16 seats in the cabinet.[68]

Chancellor of Germany, 2005–2021

Official portrait with the Merkel-Raute, 2010 | |

| Chancellorship of Angela Merkel 22 November 2005 – 8 December 2021 | |

Angela Merkel | |

| Cabinet |

|

| Party | Christian Democratic Union |

| Election | |

| Nominated by | Bundestag |

| Appointed by |

|

| Seat |

|

|

| |

First CDU–SPD grand coalition, 2005–2009

The First Merkel cabinet was sworn in at 16:00 CET on 22 November 2005. On 31 October 2005, after the defeat of his favoured candidate for the position of Secretary General of the SPD, Franz Müntefering indicated that he would resign as party chairman, which he did in November. Ostensibly responding to this, Edmund Stoiber (CSU), who was originally nominated as Minister for Economics and Technology, announced his withdrawal on 1 November 2005. While this was initially seen as a blow to Merkel's attempt at forming a viable coalition, the manner in which Stoiber withdrew earned him much ridicule and severely undermined his position as a Merkel rival. Separate conferences of the CDU, CSU, and SPD approved the proposed Cabinet on 14 November 2005. The second Cabinet of Angela Merkel was sworn in on 28 October 2009.[69]

On 22 November 2005, Merkel assumed the office of Chancellor of Germany following a stalemate election that resulted in a grand coalition with the SPD. The coalition deal was approved by both parties at party conferences on 14 November 2005.[70] Merkel was elected Chancellor by the majority of delegates (397 to 217) in the newly assembled Bundestag on 22 November 2005, but 51 members of the governing coalition voted against her.[71]

Reports at the time indicated that the grand coalition would pursue a mix of policies, some of which differed from Merkel's political platform as leader of the opposition and candidate for Chancellor. The coalition's intent was to cut public spending whilst increasing VAT (from 16 to 19%), social insurance contributions and the top rate of income tax.[72]

When announcing the coalition agreement, Merkel stated that the main aim of her government would be to reduce unemployment, and that it was this issue on which her government would be judged.[73]

CDU–FDP coalition, 2009–2013

Her party was re-elected in 2009 with an increased number of seats, and could form a governing coalition with the FDP. This term was overshadowed by the European debt crisis. Conscription in Germany was abolished and the Bundeswehr became a volunteer military. Unemployment sank below the mark of 3 million unemployed people.[74]

_079.jpg.webp)

In the election of September 2013, Merkel won one of the most decisive victories in German history, achieving the best result for the CDU/CSU since reunification and coming within five seats of the first absolute majority in the Bundestag since 1957.[75] However, their preferred coalition partner, the FDP, failed to enter parliament for the first time since 1949, being below the minimum of 5% of votes required to enter parliament.[18][76]

Second CDU–SPD grand coalition 2013–2017

The CDU/CSU turned to the SPD to form the third grand coalition in postwar German history and the second under Merkel's leadership. The third Cabinet of Angela Merkel was sworn in on 17 December 2013.[77]

Midway through her second term, Merkel's approval plummeted in Germany, resulting in heavy losses in state elections for her party.[78] An August 2011 poll found her coalition had only 36% support compared to a rival potential coalition's 51%.[79] However, she scored well on her handling of the recent euro crisis (69% rated her performance as good rather than poor), and her approval rating reached an all-time high of 77% in February 2012 and again in July 2014.[80]

Merkel's approval rating dropped to 54% in October 2015, during the European migrant crisis, the lowest since 2011.[81] According to a poll conducted after terror attacks in Germany Merkel's approval rating dropped to 47% (August 2016).[82] Half of Germans did not want her to serve a fourth term in office compared to 42% in favor.[83] However, according to a poll taken in October 2016, her approval rating had been found to have risen again, 54% of Germans were found to be satisfied with work of Merkel as Chancellor.[84] According to another poll taken in November 2016, 59% were to found to be in favour of a renewed Chancellor candidature of Merkel in 2017.[85] According to a poll carried out just days after the 2016 Berlin truck attack, in which it was asked which political leader(s) Germans trust to solve their country's problems; 56% named Merkel, 39% Seehofer (CSU), 35% Gabriel (SPD), 32% Schulz (SPD), 25% Özdemir (Greens), 20% Wagenknecht (Left Party), 15% Lindner (FDP), and just 10% for Petry (AfD).[86]

In the 2017 federal election, Merkel led her party to victory for the fourth time. Both CDU/CSU and SPD received a significantly lower proportion of the vote than they did in 2013, and attempted to form a coalition with the FDP and Greens.[87][88] The collapse of these talks led to stalemate.[89] The German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier subsequently appealed successfully to the SPD to change their hard stance and to agree to a third grand coalition with the CDU/CSU.[90]

A YouGov survey published in late December 2017 found that just 36 percent of all respondents wanted Merkel to stay at the helm until 2021, while half of those surveyed voters called for a change at the top before the end of the legislature.[91]

Third CDU–SPD grand coalition, 2018–2021

The Fourth Merkel cabinet was sworn in on 14 March 2018.[92] The negotiations that led to a Grand Coalition agreement with the Social Democrats (SPD) were the longest in German post-war history, lasting almost six months.[93][94]

In October 2018, Merkel announced that she had decided not to run for re-election in the 2021 federal election. In August 2019, 67% of Germans wanted Merkel to stay until the end of her term in 2021, while only 29% wanted her to step down earlier.[95]

In September 2021, she referred to her party after she leaves the chancellery, and said that "after 16 years one does not automatically ... return to the chancellery, that was clear to everyone in the CDU and CSU", describing the close opinion polls about the upcoming election. The remarks came as the Social Democrats had overtaken her conservatives in recent polls.[96]

On 26 September 2021, elections proved inconclusive, although the SPD won the most votes. This necessitated long negotiations among the various parties to form a government. On 23 November 2021, a new coalition was announced, with Olaf Scholz nominated to succeed Merkel.[97] Merkel continued to serve as chancellor in a caretaker capacity until 8 December 2021, when Scholz was sworn in.[98]

Political positions

Immigration, refugees and migration

In October 2010, Merkel told a meeting of younger members of her conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU) party at Potsdam that attempts to build a multicultural society in Germany had "utterly failed,"[99] stating that: "The concept that we are now living side by side and are happy about it" does not work[100] and "we feel attached to the Christian concept of mankind, that is what defines us. Anyone who doesn't accept that is in the wrong place here."[101] She continued to say that immigrants should integrate and adopt Germany's culture and values. This has added to a growing debate within Germany[102] on the levels of immigration, its effect on Germany and the degree to which Muslim immigrants have integrated into German society.

Merkel is in favour of a "mandatory solidarity mechanism" for relocation of asylum-seekers from Italy and Greece to other EU member states as part of the long-term solution to Europe's migrant crisis.[103][104]

2015 European migrant crisis

In late August 2015, during the height of the European migrant crisis, Merkel's government suspended European provisions, which stipulated that asylum seekers must seek asylum in the first EU country they arrive. Instead Merkel announced that Germany would also process asylum applications from Syrian refugees if they had come to Germany through other EU countries.[105] That year, nearly 1.1 million asylum seekers entered Germany.

Junior coalition partner, Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel said that Germany could take in 500,000 refugees annually for the next several years.[106] German opposition to the government's admission of the new wave of migrants was strong and coupled with a rise in anti-immigration protests.[107] Merkel insisted that Germany had the economic strength to cope with the influx of migrants and reiterated that there is no legal maximum limit on the number of migrants Germany can take.[108] In September 2015, enthusiastic crowds across the country welcomed arriving refugees and migrants.[109]

Horst Seehofer, leader of the Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU)—the sister party of Merkel's Christian Democratic Union—and then-Bavarian Minister President, attacked Merkel's policies.[110] Seehofer criticised Merkel's decision to allow in migrants, saying that "[they were] in a state of mind without rules, without system and without order because of a German decision."[111] Seehofer estimated as many as 30 percent of asylum seekers arriving in Germany claiming to be from Syria are in fact from other countries,[112] and suggested reducing EU funding for member countries that rejected mandatory refugee quotas.[113] Meanwhile, Yasmin Fahimi, secretary-general of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), the junior partner of the ruling coalition, praised Merkel's policy allowing migrants in Hungary to enter Germany as "a strong signal of humanity to show that Europe's values are valid also in difficult times".[110]

In November 2015, there were talks inside the governing coalition to stop family unification for migrants for two years, and to establish "Transit Zones" on the border and – for migrants with low chances to get asylum approved – to be housed there until their application is approved. The issues are in conflict between the CSU who favoured those new measures and threatened to leave the coalition without them, and the SPD who opposes them; Merkel agreed to the measures.[114] The November 2015 Paris attacks prompted a reevaluation of German officials' stance on the EU's policy toward migrants.[115] There appeared to be a consensus among officials, with the exception of Merkel, that a higher level of scrutiny was needed in vetting migrants with respect to their mission in Germany.[115] However, while not officially limiting the influx numerically, Merkel tightened asylum policy in Germany.[116]

In October 2016, Merkel travelled to Mali and Niger. The diplomatic visit took place to discuss how their governments could improve conditions which caused people to flee those countries and how illegal migration through and from these countries could be reduced.[117]

The migrant crisis spurred right-wing electoral preferences across Germany with the Alternative for Germany (AfD) gaining 12% of the vote in the 2017 German federal election. These developments prompted debates over the reasons for increased right-wing populism in Germany. Literature argued that the increased right-wing preferences are a result of the European migrant crisis which has brought thousands of people, predominantly from Muslim countries to Germany, and spurred a perception among a share of Germans that refugees constitute an ethnic and cultural threat to Germany.[118]

2018 asylum government crisis

In March 2018, the CSU's Horst Seehofer took over the role of Interior Minister. A policy Seehofer announced is that he has a "master plan for faster asylum procedures, and more consistent deportations."[119] Under Seehofer's plan, Germany would reject migrants who have already been deported or have an entry ban and would instruct police to turn away all migrants who have registered elsewhere in the EU, no matter if these countries agreed to take them back.[120][121] Merkel feared that unilaterally sending migrants back to neighbouring countries without seeking a multilateral European agreement could endanger the stability of the European Union.

In June 2018, Seehofer backed down from a threat to bypass her in the disagreement over immigration policy until she would come back on 1 July from attempts to find a solution at the European level. On 1 July 2018, Seehofer rejected the agreement Merkel had obtained with EU countries as too little and declared his resignation during a meeting of his party's executive, but they refused to accept it.[122][123][124] During the night of 2 July 2018, Seehofer and Merkel announced they had settled their differences and agreed to instead accept a compromise of tighter border control.[125][126] As a result of the agreement, Seehofer agreed to not resign,[127] and to negotiate bilateral agreements with the specific countries himself. Seehofer was criticised for almost bringing the government down while the monthly number of migrants targeted by that policy was in single figures.

COVID-19 pandemic

On 6 April 2020, Merkel stated: "In my view... the European Union is facing the biggest test since its foundation and member states must show greater solidarity so that the bloc can emerge stronger from the economic crisis unleashed by the pandemic".[128] Merkel has won international plaudits for her handling of the pandemic in Germany.[129][16]

During the German presidency of the European Council Merkel not only changed her mind, but spearheaded negotiating a reconstruction package for the time after the pandemic.[130]

Foreign policy

.jpg.webp)

Merkel's foreign policy has focused on strengthening European cooperation and international trade agreements. She and her governments have been closely associated with the Wandel durch Handel policy.[131] For this, she has come under criticism, especially after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[132][133] Merkel has been widely described as the de facto leader of the European Union throughout her tenure as Chancellor.

In 2015, with the absence of Stephen Harper, Merkel became the only leader to have attended every G20 meeting since the first in 2008, having been present at a record fifteen summits as of 2021. She hosted the twelfth meeting at the 2017 G20 Hamburg summit.[134]

United States

One of Merkel's priorities was strengthening transatlantic economic relations. She signed the agreement for the Transatlantic Economic Council on 30 April 2007 at the White House.[135]

Merkel enjoyed good relations with US presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama.[136] Obama described her in 2016 as his "closest international partner" throughout his tenure as president.[137] Obama's farewell visit to Berlin in November 2016 was widely interpreted as the passing of the torch of global liberal leadership to Merkel as Merkel was seen by many as the new standard bearer of liberal democracy since the election of Donald Trump as US president.[138][139]

Upon the election of Donald Trump Merkel said that "Germany and America are tied by values of democracy, freedom and respect for the law and human dignity, independent of origin, skin colour, religion, gender, sexual orientation or political views. I offer the next president of the United States, Donald Trump, close cooperation on the basis of these values."[140] The comment was characterized by policy analyst Jennifer Rubin as manifesting the psychological principle of reintegrative shaming.[141]

Following the G7 Summit in Italy and the NATO Summit in Brussels, Merkel stated on 28 May 2017 that the US was no longer the reliable partner Europe and Germany had depended on in the past.[142] At an electoral rally in Munich, she said that "We have to know that we must fight for our future on our own, for our destiny as Europeans",[143] which has been interpreted as an unprecedented shift in the German-American transatlantic relationship.[144][142]

China

On 25 September 2007, Merkel met the 14th Dalai Lama for "private and informal talks" in the Chancellery in Berlin amid protest from China. China afterwards cancelled separate talks with German officials, including talks with Justice Minister Brigitte Zypries.[145]

In recognition of the importance of China to the German economy, by 2014 Merkel had led seven trade delegations to China since assuming office in 2005. The same year, in March, China's President Xi Jinping visited Germany.[146]

In response to the death of Chinese Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo, who died of organ failure while in government custody, Merkel said in a statement that Liu had been a "courageous fighter for civil rights and freedom of expression."[147]

In July 2019, the UN ambassadors from 22 nations, including Germany, signed a joint letter to the UNHRC condemning China's mistreatment of the Uyghurs as well as its mistreatment of other minority groups, urging the Chinese government to close the Xinjiang re-education camps.[148]

Russia

In 2006, Merkel expressed concern about overreliance on Russian energy, but she received little support from others in Berlin.[149]

In June 2017, Merkel criticized the draft of new US sanctions against Russia that target EU–Russia energy projects, including Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline.[150]

Other issues

Merkel favors the Association Agreement between Ukraine and the European Union; but stated in December 2012 that its implementation depends on reforms in Ukraine.[151]

Merkel expressed support for Israel's right to defend itself during the 2014 Israel–Gaza conflict. She telephoned Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on 9 July to condemn "without reservation rocket fire on Israel".[152]

In June 2018, Merkel said that there had been "no moral or political justification" for the post-war expulsion of ethnic Germans from Central and Eastern European countries.[153]

Eurozone crisis

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

During the financial crisis of 2007–2008, the German government stepped in to assist the mortgage company Hypo Real Estate with a bailout, which was agreed on 6 October, with German banks to contribute €30 billion and the Bundesbank €20 billion to a credit line.[154]

On 4 October 2008, following the Irish Government's decision to guarantee all deposits in private savings accounts, a move she strongly criticised,[155] Merkel said there were no plans for the German Government to do the same. The following day, Merkel stated that the government would guarantee private savings account deposits, after all.[156] However, two days later, on 6 October 2008, it emerged that the pledge was simply a political move that would not be backed by legislation.[157] Other European governments eventually either raised the limits or promised to guarantee savings in full.[157]

Social expenditure

At the World Economic Forum in Davos, 2013, she said that Europe had only 7% of the global population and produced only 25% of the global GDP, but that it accounted for almost 50% of global social expenditure. She went on to say that Europe could only maintain its prosperity by being innovative and measuring itself against the best.[158] Since then, this comparison has become a central element in major speeches.[159] The international financial press has widely commented on her thesis, with The Economist saying:

If Mrs Merkel's vision is pragmatic, so too is her plan for implementing it. It can be boiled down to three statistics, a few charts and some facts on an A4* sheet of paper. The three figures are 7%, 25% and 50%. Mrs Merkel never tires of saying that Europe has 7% of the world's population, 25% of its GDP and 50% of its social spending. If the region is to prosper in competition with emerging countries, it cannot continue to be so generous.[160] ... She produces graphs of unit labour costs ... at EU meetings in much the same way that the late Margaret Thatcher used to pull passages from Friedrich Hayek's Road to Serfdom from her handbag.[160]

The Financial Times commented: "Although Ms Merkel stopped short of suggesting that a ceiling on social spending might be one yardstick for measuring competitiveness, she hinted as much in the light of soaring social spending in the face of an ageing population.[161][lower-alpha 2]

International status

.jpg.webp)

Merkel was widely described as the de facto leader of the European Union throughout her tenure as Chancellor. Merkel was twice named the world's second most powerful person, following Vladimir Putin, by Forbes magazine, the highest ranking ever achieved by a woman.[163][164][165][166][167] On 26 March 2014, Merkel became the longest-serving incumbent head of government in the European Union. In December 2015, Merkel was named as Time magazine's Person of the Year, with the magazine's cover declaring her to be the "Chancellor of the Free World".[168] In 2018, Merkel was named the most powerful woman in the world for a record fourteenth time by Forbes.[169] Following the election of Donald Trump to the US presidency in 2016, Merkel was described by The New York Times as "the Liberal West's Last Defender",[170] and by a number of commentators as the "leader of the free world".[171][172][173][174] Specifically, Politico called Merkel the "leader of the free world" when reporting on her meeting with President Trump.[14] Former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton described Merkel in 2017 as "the most important leader in the free world".[175] The Atlantic described her in 2019 as "the world's most successful living politician, on the basis of both achievement and longevity".[176] She was found in a 2018 survey to be the most respected world leader internationally.[177] She was named as Harvard University's commencement speaker in 2019; Harvard University President Larry Bacow described her as "one of the most widely admired and broadly influential statespeople of our time".[178] When Merkel retired as Chancellor, Hillary Clinton wrote that "she led Europe through difficult times with steadiness and bravery, and for four long years, she was the leader of the free world."[15][179]

Succession

On 29 October 2018, Merkel announced that she would not seek reelection as leader of CDU at their party conference in December 2018, but intended to remain as chancellor until the 2021 German federal election was held. She stated that she did not plan to seek any political office after this. The resignations followed October setbacks for the CSU in the Bavarian state election and for the CDU in the Hessian state election.[21][180] In August 2019, Merkel hinted that she might return to academia at the end of her term in 2021.[181]

She decided not to suggest any person as her successor as leader of the CDU.[182] However, political observers had long considered Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer as Merkel's protégé groomed for succession. This view was confirmed when Kramp-Karrenbauer – widely seen as the chancellor's favourite for the post – was voted to succeed Merkel as leader of the CDU in December 2018.[183] Kramp-Karrenbauer's elevation to Defence Minister after Ursula von der Leyen's departure to become president of the European Commission also boosted her standing as Merkel's most likely candidate for succession.[184] In 2019, media outlets speculated that Kramp-Karrenbauer might take over Merkel's position as Chancellor sooner than planned if the current governing coalition proved unsustainable.[185][186] The possibility was neither confirmed nor denied by the party.[187] In February 2020, Kramp-Karrenbauer announced that she would resign as party leader of the CDU in the summer, after party members in Thuringia defied her by voting with Alternative for Germany to support an FDP candidate for minister-president.[188] Kramp-Karrenbauer was succeeded by Armin Laschet at the 2021 CDU leadership election.[189]

Retired life and legacy

On 25 February 2022, only 24 hours after the Russian invasion of Ukraine began, she told the DPA news agency that she "condemned in the strongest terms [...] the war of aggression led by Russia, which marks a profound break in the history of post-Cold War Europe."[190]

In April her spokesperson stated that she "stood by her position at the NATO summit in Bucharest in 2008," when she had opposed Ukraine's membership in the North Atlantic Alliance.[190]

On 1 June 2022 Merkel made her first semi-public comments about political affairs since leaving office, at a retirement party for Reiner Hoffmann, the president of the German Trade Union Confederation (DGB). As an aside she said "I cannot make this speech without mentioning the blatant violation of international law by Russia. My solidarity is with Ukraine, which has been attacked and invaded by Russia," also applauding "the efforts of the Federal Republic of Germany, the European Union, and the United States to put an end to this barbaric war of aggression led by Russia... The current events remind us that peace and freedom can never be taken for granted. The great idea of Europe as a community based on values and the defense of peace."[190]

On 7 June 2022 Merkel made her first public comments. In a Berlin theatre interview before a crowd of 2,000 with Der Spiegel journalist Alexander Osang, she defended her legacy on Ukraine, and termed the Putinian aggression "not just unacceptable, but also a major mistake from Russia... It's an objective breach of all international laws and of everything that allows us in Europe to live in peace at all. If we start going back through the centuries and arguing over which bit of territory should belong to whom, then we will only have war. That's not an option whatsoever."[191][192] She also said that by the end of her chancellorship in September 2021, it was clear that Putin was moving in the direction of conflict and that he was finished with the Normandy format talks.[193]

Personal life

In 1977, at the age of 23, Merkel, then Angela Kasner, married physics student Ulrich Merkel (born 1953)[194] and took his surname. The marriage ended in divorce in 1982.[195] Her second and current husband is quantum chemist and professor Joachim Sauer, who has largely remained out of the media spotlight. They first met in 1981,[196] became a couple later and married privately on 30 December 1998.[197] She has no children, but Sauer has two adult sons from a previous marriage.[198]

Having grown up in East Germany, Merkel learned Russian at school and not English. She was able to speak informally to Vladimir Putin in Russian, but conducted diplomatic dialogue through an interpreter. She rarely spoke English in public, but delivered a small section of an address to the British parliament in English in 2014.[199][200]

Merkel is a fervent football fan and has been known to listen to games while in the Bundestag and to attend games of the national team in her official capacity, including Germany's 1–0 victory against Argentina in the 2014 World Cup Final.[201][202][203] Merkel stated that her favorite movie is The Legend of Paul and Paula, an East German movie released in 1973.[204]

Merkel has a fear of dogs after being attacked by one in 1995.[205] Vladimir Putin brought in his Labrador Retriever during a press conference in 2007. Putin claims he did not mean to scare her, though Merkel later observed, "I understand why he has to do this – to prove he's a man. ... He's afraid of his own weakness."[205]

Since 2017 Merkel has been seen and filmed to shake visibly on several public occasions, recovering shortly afterwards.[206][207][208] After one such occasion she attributed the shaking to dehydration, saying that she felt better after a drink of water.[209] After three occasions where this happened in June 2019, she began to sit down during the performances of the national anthems during the State visits of Mette Frederiksen and Maia Sandu the following month.

In September 2021, after years of evading the question, Merkel said she considered herself a feminist. The statement came in a conference along with Nigerian writer and feminist icon Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.[210]

Religion

Angela Merkel is a Lutheran member of the Evangelical Church in Berlin, Brandenburg and Silesian Upper Lusatia (German: Evangelische Kirche Berlin-Brandenburg-schlesische Oberlausitz – EKBO), a United Protestant (i.e. both Reformed and Lutheran) church body under the umbrella of the Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD). The EKBO is a church of the Union of Evangelical Churches.[211] Before the 2004 merger of the Evangelical Church in Berlin-Brandenburg and the Evangelical Church in Silesian Upper Lusatia (both also being a part of the EKD), she belonged to the former. In 2012, Merkel said, regarding her faith: "I am a member of the evangelical church. I believe in God and religion is also my constant companion, and has been for the whole of my life. We as Christians should above all not be afraid of standing up for our beliefs."[212] She also publicly declared that Germany suffers not from "too much Islam" but "too little Christianity".[213]

Honours and awards

National honours

Germany:

Germany:  Grand Cross 1st Class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany[214]

Grand Cross 1st Class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany[214]

Foreign honours

Austria:

Austria:  Grand Decoration of Honour in Gold with Sash of the Order of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria[215]

Grand Decoration of Honour in Gold with Sash of the Order of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria[215].svg.png.webp) Belgium:

Belgium:  Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold[216]

Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold[216] Bulgaria:

Bulgaria:  Grand Cross of the Order of the Balkan Mountains[217][218]

Grand Cross of the Order of the Balkan Mountains[217][218] Estonia:

Estonia:  Member 1st Class of the Order of the Cross of Terra Mariana (23 February 2021)

Member 1st Class of the Order of the Cross of Terra Mariana (23 February 2021) France:

France:  Grand Cross of the Order of the Legion of Honour (3 November 2021)

Grand Cross of the Order of the Legion of Honour (3 November 2021) India:

India:  Recipient of the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding[219]

Recipient of the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding[219] Israel:

Israel:  Recipient of the President's Medal[220]

Recipient of the President's Medal[220] Italy:

Italy:  Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic[221]

Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic[221] Jordan:

Jordan:  Grand Cordon of the Supreme Order of the Renaissance (27 October 2021)

Grand Cordon of the Supreme Order of the Renaissance (27 October 2021) Latvia:

Latvia:  Grand Officer of the Order of the Three Stars[222]

Grand Officer of the Order of the Three Stars[222] Luxembourg:

Luxembourg:  Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (18 October 2021)

Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (18 October 2021) Lithuania:

Lithuania:  Grand Cross of the Order of Vytautas the Great[223][224]

Grand Cross of the Order of Vytautas the Great[223][224] Moldova:

Moldova:  Member of the Order of the Republic (12 November 2015)[225]

Member of the Order of the Republic (12 November 2015)[225] Norway:

Norway:  Grand Cross of the Royal Norwegian Order of Merit[226]

Grand Cross of the Royal Norwegian Order of Merit[226] Netherlands:

Netherlands:  Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Netherlands Lion (13 July 2022)[227]

Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Netherlands Lion (13 July 2022)[227] Peru:

Peru:  Grand Cross of the Order of the Sun of Peru

Grand Cross of the Order of the Sun of Peru Portugal:

Portugal:  Collar of the Order of Infante Henry (9 December 2021)

Collar of the Order of Infante Henry (9 December 2021) Saudi Arabia:

Saudi Arabia: .png.webp) Grand Officer of the Order of Abdulaziz al Saud

Grand Officer of the Order of Abdulaziz al Saud United Arab Emirates:

United Arab Emirates:  Collar of the Order of Zayed[228]

Collar of the Order of Zayed[228] United States:

United States: .svg.png.webp) Recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom[lower-alpha 3][229][230]

Recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom[lower-alpha 3][229][230] United States:

United States:  Recipient of the Four Freedoms Award[231]

Recipient of the Four Freedoms Award[231] Slovakia:

Slovakia:  Grand Cross of the Order of the White Double Cross[232]

Grand Cross of the Order of the White Double Cross[232] Slovenia:

Slovenia: .png.webp) Recipient of the Decoration for Exceptional Merits

Recipient of the Decoration for Exceptional Merits Ukraine:

Ukraine:  Recipient of the Order of Liberty[233]

Recipient of the Order of Liberty[233]

Honorary degrees

- In 2007, Merkel was awarded an honorary doctorate from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.[234]

- In June 2008, she was awarded an honorary doctorate from Leipzig University.[235]

- University of Technology in Wrocław (Poland) in September 2008[236] and Babeș-Bolyai University from Cluj-Napoca, Romania on 12 October 2010 for her historical contribution to the European unification and for her global role in renewing international cooperation.[237][238][239]

- On 23 May 2013, she was awarded an honorary doctorate from the Radboud University Nijmegen.

- In November 2013, she was awarded the Honorary Doctorate (Honoris Causa) title by the University of Szeged.

- In November 2014, she was awarded the title Doctor Honoris Causa by Comenius University in Bratislava.

- In September 2015, she was awarded the title Doctor Honoris Causa by the University of Bern.

- In January 2017, she was awarded the title Doctor Honoris Causa jointly by Ghent University and Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.[240]

- In May 2017, Merkel was awarded the title of Doctrix Honoris Causa by the University of Helsinki.[241]

- In May 2019, Merkel was awarded an honorary doctorate from Harvard University.[242]

- In October 2020, Merkel was awarded an honorary doctorate from The Technion - Israel Institute of Technology.[243]

- In July 2021, Merkel was awarded the title Doctor of Humane Letters, honoris causa from Johns Hopkins University.[244]

Awards

- In 2006, Merkel was awarded the Vision for Europe Award for her contribution toward greater European integration.

- She received the Karlspreis (Charlemagne Prize) in 2008 for distinguished services to European unity.[245][246]

- In March 2008, she received the B'nai B'rith Europe Award of Merit.[247]

- Merkel topped Forbes magazine's list of "The World's 100 Most Powerful Women" in 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2020.[248]

- In 2010, New Statesman named Merkel as one of "The World's 50 Most Influential Figures".[249]

- On 16 June 2010, the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies at Johns Hopkins University in Washington D.C. awarded Merkel its Global Leadership Award (AICGS) in recognition of her outstanding dedication to strengthening German-American relations.[250]

- On 21 September 2010, the Leo Baeck Institute, a research institution in New York City devoted to the history of German-speaking Jewry, awarded Merkel the Leo Baeck Medal. The medal was presented by former US Secretary of the Treasury and current Director of the Jewish Museum Berlin, W. Michael Blumenthal, who cited Merkel's support of Jewish cultural life and the integration of minorities in Germany.[251]

- On 31 May 2011, she received the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for the year 2009 from the Indian government. She received the award for International understanding.[252]

- Forbes list of The World's Most Powerful People ranked Merkel as the world's second most powerful person in 2012, the highest ranking achieved by a woman since the list began in 2009; she was ranked fifth in 2013 and 2014

- On 28 November 2012, she received the Heinz Galinski Award in Berlin, Germany.

- In 2013, she received the Indira Gandhi Peace Prize.[253]

- In December 2015, she was named Time magazine's Person of the Year.[254]

- In May 2016, Merkel received the International Four Freedoms Award from the Roosevelt Foundation in Middelburg, the Netherlands.[255]

- In 2017, Merkel received the Elie Wiesel Award from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.[256]

- In January 2019, Merkel received the 2018 Fulbright Prize for International Understanding from the Fulbright Association[257]

- In 2020, Merkel received the Henry A. Kissinger Prize from the American Academy in Berlin.[258]

- In 2022, Angela Merkel wins Unesco Peace Prize 2022 for her efforts to welcome refugees.[259]

Comparisons

.jpg.webp)

As a woman who is a politician from a centre-right party and also a scientist, Merkel has been compared by many in the English-language press to late 20th century British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (Thatcher also had a science degree from Oxford University in chemistry). Some have referred to her as "Iron Lady", "Iron Girl", and even "The Iron Frau", all alluding to Thatcher, whose nickname was "The Iron Lady". Political commentators have debated the precise extent to which their agendas are similar.[260] Later in her tenure, Merkel acquired the nickname "Mutti" (a German familiar form of "mother"). She has also been called the "Iron Chancellor", in reference to Otto von Bismarck.[261][262]

In addition to being the first female German chancellor, the first to have grown up in the former East Germany (though she was born in the West),[263] and the youngest German chancellor since the Second World War, Merkel is also the first born after World War II, and the first chancellor of the Federal Republic with a background in natural sciences. While she studied physics, her predecessors studied law, business or history, among other professions.

Controversies

Merkel has been criticised for being personally present and involved at the M100 Media Award handover[264] to Danish cartoonist Kurt Westergaard, who had triggered the Muhammad cartoons controversy. This happened at a time of fierce emotional debate in Germany over a book by the former Deutsche Bundesbank executive and finance senator of Berlin Thilo Sarrazin, which was critical of the Muslim immigration.[265] At the same time she condemned a planned burning of Qurans by a fundamental pastor in Florida.[266] The Central Council of Muslims in Germany[267][268] and the Left Party[269] (Die Linke) as well as the German Green Party[lower-alpha 4][270] criticised the action by the centre-right chancellor. The Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung newspaper wrote: "This will probably be the most explosive moment of her chancellorship so far."[271] Others have praised Merkel and called it a brave and bold move for the cause of freedom of speech.

Merkel's position towards the negative statements by Thilo Sarrazin with regard to the integration problems with Arab and Turkish people in Germany has been critical throughout. According to her personal statements, Sarrazin's approach is "totally unacceptable" and counterproductive to the ongoing problems of integration.[272]

The term alternativlos (German for "without an alternative"), which was frequently used by Angela Merkel to describe her measures addressing the European sovereign-debt crisis, was named the Un-word of the Year 2010 by a jury of linguistic scholars. The wording was criticised as undemocratic, as any discussion on Merkel's politics would thus be deemed unnecessary or undesirable.[273] The expression is credited for the name of the political party Alternative for Germany, which was founded in 2013.[274]

In July 2013, Merkel defended the surveillance practices of the National Security Agency, and described the United States as "our truest ally throughout the decades".[275][276] During a visit of U.S. President Barack Obama in Berlin, Merkel said on 19 June 2013 in the context of the 2013 mass surveillance disclosures: "The Internet is uncharted territory for us all" (German: Das Internet ist für uns alle Neuland). This statement led to various internet memes and online mockery of Merkel.[277][278]

Merkel compared the NSA to the Stasi when it became known that her mobile phone was tapped by that agency. In response, Susan Rice pledged that the US would desist from spying on her personally, but said there would not be a no-espionage agreement between the two countries.[279]

In July 2014 Merkel said trust between Germany and the United States could only be restored by talks between the two, and she would seek to have talks. She reiterated that the US remained Germany's most important ally.[280]

Her statement "Islam is part of Germany" during a state visit of the Turkish prime minister Ahmet Davutoğlu in January 2015[281] induced criticism within her party. The parliamentary group leader Volker Kauder said that Islam is not part of Germany and that Muslims should deliberate on the question why so many violent people refer to the Quran.[282]

In October 2015, Horst Seehofer, Bavarian State Premier and CSU leader, criticised Merkel's policy of allowing in hundreds of thousands of migrants from the Middle East: "We're now in a state of mind without rules, without system and without order because of a German decision."[111] Seehofer attacked Merkel policies in sharp language, threatened to sue the government in the high court, and hinted that the CSU might topple Merkel. Many MPs of Merkel's CDU party also voiced dissatisfaction with Merkel.[283] Chancellor Merkel insisted that Germany has the economic strength to cope with the influx of migrants and reiterated that there is no legal maximum limit on the number of migrants Germany can take.[284] Under her open-borders policy several women were murdered by the unchecked immigrants like the Murder of Maria Ladenburger and 2018 Killing of Susanna Feldmann, it also allowed the events of the 2015/2016 New Year's Eve, mainly in the city of Cologne, where hundreds of women were sexually assaulted.

At the conclusion of the May 2017 Group of Seven's leaders in Sicily, Merkel criticised American efforts to renege on earlier commitments on climate change. According to Merkel, the discussions were difficult and marred by dissent. "Here we have the situation where six members, or even seven if you want to add the EU, stand against one."[285]

Merkel has faced criticism for failing to take a tough line on the People's Republic of China.[286][287][288] The Asia Times reported that "Unlike certain of her European counterparts, her China diplomacy has focused on non-interference in Beijing's internal affairs. As such, Merkel was reportedly furious when her Foreign Minister Heiko Maas received Hong Kong dissident Joshua Wong in Berlin in September [2019], a move that Beijing publicly protested."[289]

Merkel's government decided to phase out both nuclear power and coal plants and supported the European Commission's Green Deal plans.[290][291] Many critics blamed the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) and closure of nuclear plants for contributing to the 2021–2022 global energy crisis.[291][292][293]

Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Merkel faced renewed criticisms that she had failed to curb Russian president Vladimir Putin's ambitions and aggression by insisting on diplomacy and détente policies.[294][295][296] Critics argued that under her tenure, Germany and Europe was weakened by a dependency on Russian natural gas, including the Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2 pipelines,[294][295] and that the German military was neglected by underfunding.[297][296] Her chancellorship has become tightly associated with the policy of Wandel durch Handel, pursuing close economic ties with authoritarian leaders. When the Wandel durch Handel policy came under intense domestic and international scrutiny following the Russian invasion, Merkel received much of the blame,[131][133] leading Politico to write "[n]o German is more responsible for the crisis in Ukraine than Merkel".[132] Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy also blamed Merkel and then-French president Nicolas Sarkozy's decision to block Ukraine from joining NATO in 2008 for the war; Merkel released a statement that she stands by her decision.[298]

In the arts and media

Since 1991, Merkel has sat annually for sitting and standing portraits by, and interview with, Herlinde Koelbl.[299][300]

Merkel was portrayed by Swiss actress Anna Katarina in the 2012 political satire film The Dictator.[301]

Merkel features as a main character in two of the three plays that make up the Europeans Trilogy (Bruges, Antwerp, and Tervuren) by Paris-based UK playwright Nick Awde: Bruges (Edinburgh Festival, 2014) and Tervuren (2016). A character named Merkel, accompanied by a sidekick called Schäuble, also appears as the sinister female henchman in Michael Paraskos's novel In Search of Sixpence.[302]

On the American sketch-comedy Saturday Night Live, she has been parodied by Kate McKinnon since 2013.[303][304][305]

On the British sketch-comedy Tracey Ullman's Show, comedian Tracey Ullman has parodied Merkel to international acclaim with German media dubbing her impersonation as the best spoof of Merkel in the world.[306]

In 2016, a documentary film Angela Merkel – The Unexpected, a story about her unexpected rise to power from an East German physicist to the most powerful woman in the world, was produced by Broadview TV and MDR in collaboration with Arte and Das Erste.[307]

Cabinets

- de Maizière cabinet (deputy press spokeswoman, not cabinet member)

- Kohl IV (Minister for Women and Youth)

- Kohl V (Minister for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety)

- Merkel I (Chancellor)

- Merkel II (Chancellor)

- Merkel III (Chancellor)

- Merkel IV (Chancellor)

See also

- Willkommenskultur

Explanatory notes

- The English pronunciation of her first name could be /ˈɑːŋɡələ, ˈæŋ-/ (of which the former is a closer approximation of the German). The English pronunciation of her last name is either /ˈmɛərkəl/ or /ˈmɜːrkəl/ (pronunciation respelling MAIR-kəl, MUR-kəl), of which only the former is reported for American English (and is a closer approximation of the German) and only the latter is reported for British English by the Oxford and Merriam-Webster dictionaries, which base their editing on actual usage, not recommendations.[2][3][4] In German, her last name is pronounced [ˈmɛʁkl̩],[5][6] and her first name is pronounced [ˈaŋɡela] or [aŋˈɡeːla],[7] but according to her biographer Langguth, Merkel prefers the pronunciation with stress on the second syllable[8] ([aŋˈɡeːla] with a long /eː/).

- The economist Arno Tausch from Corvinus University in Budapest, in a paper published by the Social Science Research Network in New York has contended that a re-analysis of the Merkel hypothesis about the distribution of global social expenditure based on 169 countries for which we have recent ILO Social Protection data and World Bank GNI data in real purchasing power reveals that the 27 EU countries with complete data spend only 33% of global world social protection expenditures, while the 13 non-EU-OECD members, among them the major other Western democracies, spend 40% of global social protection expenditures, the BRICS 18% and the Rest of the World 9% of global social protection expenditures. Most probably, the author claims, Merkel's 50% ratio is the product of a mere, simple projection of data for the OECD-member countries onto the world level.[162] Tausch also claims that the data reveal the successful social Keynesianism of the Anglo-Saxon overseas democracies, which are in stark contrast to the savings agenda in the framework of the European "fiscal pact", see Tausch, Arno (4 September 2015), Wo Frau Kanzlerin Angela Merkel Irrt: Der Sozialschutz in der Welt, der Anteil Europas und die Beurteilung Seiner Effizienz (Where Chancellor Angela Merkel Got it Wrong: Social Protection in the World, Europe's Share in it and the Assessment of its Efficiency), doi:10.2139/ssrn.2656113, SSRN 2656113

- The medal is presented to people who have made an especially meritorious contribution to the security or national interests of the United States, world peace, or cultural or other significant public or private endeavors

- Grüne/Bündnis 90 Spokesman Renate Künast: "I wouldn't have done it", said Green Party floor leader Renate Künast. It was true that the right to freedom of expression also applies to cartoons, she said. "But if a chancellor also makes a speech on top of that, it serves to heat up the debate."[270]

References

- "Angela Merkel: Her bio in brief". The Christian Science Monitor. 20 September 2013. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- "Merkel, Angela" Archived 7 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine (US) and "Merkel, Angela". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 10 February 2020.

- "Merkel". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- Wells, J. C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Pearson Education Limited.

- Mangold, Max, ed. (1995). Duden, Aussprachewörterbuch (in German) (6th ed.). Dudenverlag. p. 501. ISBN 978-3-411-20916-3.

Merkel ˈmɛrkl̩

- Krech, Eva-Maria; Stock, Eberhard; Hirschfeld, Ursula; Anders, Lutz Christian; et al., eds. (2009). Deutsches Aussprachewörterbuch (1st ed.). Walter de Gruyter. p. 739. ISBN 978-3-11-018202-6.

Merkel mˈɛʶkl̩

- Mangold, Max, ed. (1995). Duden, Aussprachewörterbuch (in German) (6th ed.). Dudenverlag. p. 139. ISBN 978-3-411-20916-3.

Angela ˈaŋɡela auch: aŋˈɡeːla.

- Langguth, Gerd (2005). Angela Merkel (in German). Munich: dtv. p. 50. ISBN 3-423-24485-2.

Merkel wollte immer mit der Betonung auf dem 'e' Angela genannt werden. (Merkel always wanted her first name pronounced with the stress on the 'e'.)

- Government continues as acting government Archived 15 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine, bundeskanzlerin.de, 24 October 2017

- She is known in German as Bundeskanzlerin. Bundeskanzlerin is a grammatically regular formation of a noun denoting a female chancellor, adding "-in" to the end of Bundeskanzler, though the word was not used officially before Merkel.

- Vick, Karl (2015). "Time Person of the Year 2015: Angela Merkel". Time. Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- AFP. "Merkel: From austerity queen to 'leader of free world'". www.timesofisrael.com. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- "The World's Most Powerful Women 2018". Forbes. Archived from the original on 18 September 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- "The leader of the free world meets Donald Trump". POLITICO. 17 March 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- "Hillary Clinton appears to mock Donald Trump in her tribute to Angela Merkel". MSN.

- Miller, Saskia (20 April 2020). "The Secret to Germany's COVID-19 Success: Angela Merkel Is a Scientist". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Germany's Merkel begins new term". BBC. 28 October 2009. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- "German Chancellor Angela Merkel makes a hat-trick win in 2013 Elections". Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- Oltermann, Philip; Connolly, Kate (14 March 2018). "Angela Merkel faces multiple challenges in her fourth term". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Angela Merkel faces outright rebellion within her own party over refugee crisis". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- "Angela Merkel to step down in 2021". BBC News. 29 October 2018. Archived from the original on 29 October 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- Langguth, Gerd (August 2005). Angela Merkel. DTV (in German). p. 10. ISBN 3-423-24485-2.

- "Merkels Vater gestorben – Termine abgesagt" (in German). newsecho. 3 September 2011. Archived from the original on 14 December 2011. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- Qvortrup, Matthew (2016). "In the Shadow of the Berlin Wall". Angela Merkel: Europe's Most Influential Leader. The Overlook Press. ISBN 978-1-4683-1408-3.

- "Picturing the Family: Media, Narrative, Memory | Research". Archived from the original on 1 May 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- Kornelius, Stefan (March 2013). Angela Merkel: Die Kanzlerin und ihre Welt (in German). Hoffmann und Campe. p. 7. ISBN 978-3-455-50291-6.

- Kornelius, Stefan (10 September 2013). "Six things you didn't know about Angela Merkel". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- "The German chancellor's Polish roots". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 3 May 2013.

- "Merkel hat polnische Wurzeln" [Merkel has Polish roots]. Süddeutsche Zeitung. 13 March 2013. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013.

- Krauel, Torsten (13 March 2013). "Ahnenforschung: Kanzlerin Angela Merkel ist zu einem Viertel Polin". Die Welt (in German). Archived from the original on 10 September 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- Boyes, Roger (25 July 2005). "Angela Merkel: Forged in the Old Communist East, Germany's Chancellor-in-Waiting Is Not like the Others". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- Werner, Reutter (1 December 2005). "Who's Afraid of Angela Merkel?: The Life, Political Career, and Future of the New German Chancellor". International Journal. 61. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- Vasagar, Jeevan (1 September 2013). "Angela Merkel, the girl who never wanted to stand out, to win big again". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 19 April 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- Patterson, Tony (17 November 2015). "Angela Merkel's journey from Communist East Germany to Chancellor". The Independent. Archived from the original on 19 April 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- "Angela Merkel – Biography, Political Career & Facts". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- Hugh C. Dyer, Leon Mangasarian, "German Democratic Republic", in The Study of International Relations: The State of the Art, p. 328, Springer, 1989, ISBN 978-1-349-20275-1

- Spohr, Kristina (8 July 2017). "The learning machine: Angela Merkel". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- "5 Things to Know About Germany's Angela Merkel". The New York Times. Associated Press. 2017.

- "Life in Communist East Germany was 'almost comfortable' at times, Merkel says". Reuters. 8 November 2019. Archived from the original on 11 November 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- Langguth, Gerd (August 2005). Angela Merkel (in German). DTV. p. 50. ISBN 3-423-24485-2.

- Reitler, Torsten (27 March 2009). "Drogenwahn auf der Dauerbaustelle". Der Spiegel (in German). Archived from the original on 13 January 2010. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- Crawford, Alan; Czuczka, Tony (20 September 2013). "Angela Merkel's Years in East Germany Shaped Her Crisis Politics". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2017.