Nuclear power phase-out

A nuclear power phase-out is the discontinuation of usage of nuclear power for energy production. Often initiated because of concerns about nuclear power, phase-outs usually include shutting down nuclear power plants and looking towards fossil fuels and renewable energy. Three nuclear accidents have influenced the discontinuation of nuclear power: the 1979 Three Mile Island partial nuclear meltdown in the United States, the 1986 Chernobyl disaster in the USSR (now Ukraine), and the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan.

Following Fukushima, Germany has permanently shut down eight of its 17 reactors and pledged to close the rest by the end of 2022.[2] In late 2021 all but three of the remaining German nuclear power plants were shut down.[3] However, there are no plans to shut down the research reactor in Garching, Forschungsreaktor München II. Italy voted overwhelmingly to keep their country non-nuclear.[4] Switzerland and Spain have banned the construction of new reactors.[5] Japan’s prime minister called for a dramatic reduction in Japan’s reliance on nuclear power.[6] Taiwan province’s governor did the same. Shinzō Abe, the prime minister of Japan from 2012 to 2020, announced a plan to re-start some of the 54 Japanese nuclear power plants (NPPs) and to continue some NPP sites under construction.

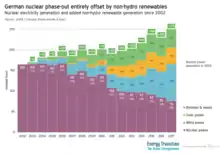

The impacts of the nuclear shut-downs on the power generation mix, post-Fukushima, have significantly set back emissions reductions goals in these countries. A recent study of the impacts of the German and Japan phaseouts concludes that by continuing to operate their nuclear plants "these two countries could have prevented 28,000 air pollution-induced deaths and 2400 MtCO2 emissions between 2011 and 2017.""By sharply reducing nuclear instead of coal and gas after Fukushima both countries lost the chance to prevent very large amounts of air pollution-induced deaths and CO2 emissions".[7] As of 2021 Japan planned on restarting 30 reactors by 2030 as well as investing in future SMR development [8]

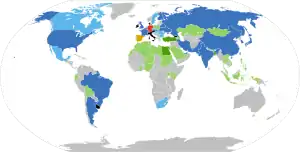

As of 2016, countries including Australia, Austria, Denmark, Ireland, Italy, Estonia, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malaysia, Malta, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal and Serbia have no nuclear power stations and remain opposed to nuclear power.[9][10] Germany, Spain and Switzerland plan nuclear phase-outs by 2030.[10][11][12][13] However several countries formerly opposed to opening nuclear programs or planning phaseouts have reversed course in recent years due to climate concerns and energy independence including Belgium,[14][15] the Philippines[16] and Greece.[17] Globally, more nuclear power reactors have closed than opened in recent years but overall capacity has increased.[12] As Generation II reactors reach the end of their service life, some countries replace them with Generation III reactors or what is deemed "Generation III+ reactors". While Generation IV reactors include small modular reactors, the majority of "evolutionary" designs like the EPR have a higher capacity than comparable reactors of earlier generations. Furthermore, countries like Canada, which decided to refurbish its existing CANDU reactors, among them Bruce Nuclear Generating Station, the most powerful single site nuclear power plant outside Asia, have increased capacity at existing reactors by optimizing efficiency.

As of 2022, Italy is the only country that has permanently closed all of its formerly functioning nuclear plants, with Germany phasing out the remaining 3 plants by the end of the year. Lithuania and Kazakhstan have shut down their only nuclear plants, but plan to build new ones to replace them, while Armenia shut down its only nuclear plant but subsequently restarted it. Austria never used its first nuclear plant that was completely built. Due to financial, political and technical reasons Cuba, Libya, North Korea and Poland never completed the construction of their first nuclear plants (although North Korea and Poland plan to). Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Georgia, Ghana, Ireland, Kuwait, Oman, Peru, Venezuela have planned, but not constructed their first nuclear plants. Between 2005 and 2015 the global production of nuclear power declined by 0.7%.[18][19]

Overview

A popular movement against nuclear power exists in the Western world, based on concerns about more nuclear accidents and concerns about nuclear waste. Anti-nuclear critics see nuclear power as a dangerous, expensive way to boil water to generate electricity.[22] The 1979 Three Mile Island accident and the 1986 Chernobyl disaster played a key role in stopping new plant construction in many countries. Major anti-nuclear power groups include Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace, Institute for Energy and Environmental Research, Nuclear Information and Resource Service, and Sortir du nucléaire (France).

Several countries, especially European countries, have abandoned the construction of new of nuclear power plants.[23] Austria (1978), Sweden (1980) and Italy (1987) voted in referendums to oppose or phase out nuclear power, while opposition in Ireland prevented a nuclear program there. Countries that have no nuclear plants and have restricted new plant constructions comprise Australia, Austria, Denmark, Greece, Italy, Ireland, Norway and Serbia.[24][25] Poland stopped the construction of a plant.[24][26] Belgium, Germany, Spain, and Sweden decided not to build new plants or intend to phase out nuclear power, although still mostly relying on nuclear energy.[24][27]

New reactors under construction in Finland and France, which were meant to lead a nuclear new build, have been substantially delayed and are running over-budget.[28][29][30] Despite these delays the Olkiluoto reactor is now online and delivering low-emissions power to the grid as of March 12, 2022. "When Olkiluoto 3 reaches full output, around 90% of Finland's electricity generation will come from clean, low-carbon electricity sources, with nuclear generation supplying around half of that."[31] In addition, China has 11 units under construction[32] and there are also new reactors being built in Bangladesh, Belarus, Brazil, India, Japan, Pakistan, Russia, Slovakia, South Korea, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom and the United States of America. At least 100 older and smaller reactors will "most probably be closed over the next 10-15 years".[33]

Countries that wish to shut down nuclear power plants must find alternatives for electricity generation; otherwise, they are forced to become dependent on imports. Therefore, the discussion of a future for nuclear energy is intertwined with discussions about fossil fuels or an energy transition to renewable energy.

Countries that have decided on a phase-out

|

Operating reactors, considering phase-out Civil nuclear power is illegal |

Austria

A nuclear power station was built during the 1970s at Zwentendorf, Austria, but its start-up was prevented by a referendum in 1978. On 9 July 1997, the Austrian Parliament voted unanimously to maintain the country's anti-nuclear policy.[34] The built but never used reactor was converted into a museum and has also been used as a movie set and to train people involved in various aspects of nuclear power and safety. It is uniquely suitable for this purpose as it includes every aspect of an actual nuclear power plant except the radiation.[35][36]

Belgium

Belgium's nuclear phase-out legislation was agreed in July 1999 by the Liberals (VLD and MR), the Socialists (SP.A and PS) and the Greens party (Groen! and Ecolo). The phase-out law calls for each of Belgium's seven reactors to close after 40 years of operation with no new reactors built subsequently. When the law was being passed, it was speculated it would be overturned again as soon as an administration without the Greens was in power.[37]

In the federal election in May 2003, there was an electoral threshold of 5% for the first time. Therefore, the Green parties the ECOLO got only 3.06% of the votes, so ECOLO obtained no seat in the Chamber of Representatives. In July 2003, Guy Verhofstadt formed his second government. It was a continuation of the Verhofstadt I Government but without the Green parties. In September 2005, the government decided to partially overturn the previous decision, extending the phase-out period for another 20 years, with possible further extensions.

In July 2005, the Federal Planning Bureau published a new report, which stated that oil and other fossil fuels generate 90% of Belgian energy use, while nuclear power accounts for 9% and renewable energy for 1%. Electricity only amounts to 16% of total energy use, and while nuclear-powered electricity amounts to 9% of use in Belgium, in many parts of Belgium, especially in Flanders, it makes up more than 50% of the electricity provided to households and businesses.[38] This was one of the major reasons to revert the earlier phase-out, since it was impossible to provide more than 50% of the electricity by 'alternative' energy-production, and a revert to the classical coal-driven electricity would mean inability to adhere to the Kyoto Protocol.

In August 2005, French SUEZ offered to buy the Belgian Electrabel, which runs nuclear power stations.[39] At the end of 2005, Suez had some 98.5% of all Electrabel shares. Beginning 2006, Suez and Gaz de France announced a merger.

After the federal election in June 2007, a political crisis began and lasted until the end of 2011.

In the 2010–2011 Belgian government formation negotiations, the phase-out was emphasized again, with concrete plans to shut off three of the country's seven reactors by 2015.[40]

Before the Fukushima nuclear disaster, the plan of the government was for all nuclear power stations to shut down by 2025.[41] Although intermediate deadlines have been missed or pushed back, on 30 March 2018 the Belgian Council of Ministers confirmed the 2025 phase-out date and stated draft legislation would be brought forward later in the year.[42]

In March 2022, the government decided to allow Doel 4 and Tihange 3 to continue operating until 2035 in order to allow the country to "strengthen its independence of fossil fuels in turbulent geopolitical times".[43] Belgium's two newest nuclear plants are operated by French utility Engie and account for almost half of the country's electricity production.[14] "This extension should allow to strengthen our country's independence from fossil fuels in a chaotic geopolitical context", the government said.[44]

Belgium continues to be active in nuclear research and is building MYRRHA, the world's first large scale demonstration of an accelerator-driven subcritical reactor that is to be used for nuclear transmutation of high level waste.[45]

Germany

In 2000, the First Schröder cabinet, consisting of the SPD and Alliance '90/The Greens, officially announced its intention to phase out the use of nuclear energy. The power plants in Stade and in Obrigheim were turned off on 14 November 2003, and 11 May 2005, respectively. The plants' dismantling was scheduled to begin in 2007.[46]

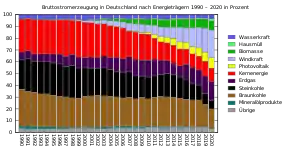

The year 2000 Renewable Energy Sources Act provided for a feed-in tariff in support of renewable energy. The German government, declaring climate protection as a key policy issue, announced a carbon dioxide reduction target by the year 2005 compared to 1990 by 25%.[47] In 1998, the use of renewables in Germany reached 284 PJ of primary energy demand, which corresponded to 5% of the total electricity demand. By 2010, the German government wanted to reach 10%.;[37] in fact, 17% were reached (2011: 20%, 2015: 30%).[48]

Anti-nuclear activists have argued the German government had been supportive of nuclear power by providing financial guarantees for energy providers. Also it has been pointed out, there were, as yet, no plans for the final storage of nuclear waste. By tightening safety regulations and increasing taxation, a faster end to nuclear power could have been forced. A gradual closing down of nuclear power plants had come along with concessions in questions of safety for the population with transport of nuclear waste throughout Germany.[49][50] This latter point has been disagreed with by the Minister of Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety.[51]

In 2005, critics of a phase-out in Germany argued that the power output from the nuclear power stations will not be adequately compensated and predict an energy crisis. They also predicted that only coal-powered plants could compensate for nuclear power and CO2 emissions would increase tremendously (with the use of oil and fossils). Energy would have to be imported from France's nuclear power facilities or Russian natural gas.[52][53][54] Numerous factors, including progress in wind turbine technology and photovoltaics, reduced the need for conventional alternatives.[55]

In 2011, Deutsche Bank analysts concluded that "the global impact of the Fukushima accident is a fundamental shift in public perception with regard to how a nation prioritizes and values its population's health, safety, security, and natural environment when determining its current and future energy pathways". There were many anti-nuclear protests and, on 29 May 2011, Merkel's government announced that it would close all of its nuclear power plants by December 2022.[56][57] Following the March 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, Germany has permanently shut down eight of its 17 reactors. Galvanised by the Fukushima nuclear disaster, first anniversary anti-nuclear demonstrations were held in Germany in March 2012. Organisers say more than 50,000 people in six regions took part.[58]

The German Energiewende designates a significant change in energy policy from 2010. The term encompasses a transition by Germany to a low carbon, environmentally sound, reliable, and affordable energy supply.[59] On 6 June 2011, following Fukushima, the government removed the use of nuclear power as a bridging technology as part of their policy.[60]

In September 2011, German engineering giant Siemens announced it will withdraw entirely from the nuclear industry, as a response to the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan, and said that it would no longer build nuclear power plants anywhere in the world. The company’s chairman, Peter Löscher, said that "Siemens was ending plans to cooperate with Rosatom, the Russian state-controlled nuclear power company, in the construction of dozens of nuclear plants throughout Russia over the coming two decades".[61][62] Also in September 2011, IAEA Director General Yukiya Amano said the Japanese nuclear disaster "caused deep public anxiety throughout the world and damaged confidence in nuclear power".[63]

A 2016 study shows that during the nuclear phaseout, the security of electricity supply in Germany stayed at the same high level compared to other European countries and even improved in 2014. The study was conducted near the halfway point of the phaseout, 9 plants having been shut and a further 8 still in operation.[64][65]

In early-October 2016, Swedish electric power company Vattenfall began litigation against the German government for its 2011 decision to accelerate the phase-out of nuclear power. Hearing are taking place at the World Bank's International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) in Washington DC and Vattenfall is claiming almost €4.7 billion in damages. The German government has called the action "inadmissible and unfounded".[66] These proceedings were ongoing in December 2016, despite Vattenfall commencing civil litigation within Germany.[67]

On 5 December 2016, the Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) ruled that the nuclear plant operators affected by the accelerated phase-out of nuclear power following the Fukushima disaster are eligible for "adequate" compensation. The court found that the nuclear exit was essentially constitutional but that the utilities are entitled to damages for the "good faith" investments they made in 2010. The utilities can now sue the German government under civil law. E.ON, RWE, and Vattenfall are expected to seek a total of €19 billion under separate suits.[68][69][70] Six cases were registered with courts in Germany, as of 7 December 2016.[67][71]

A scientific paper released in 2019 found that the German nuclear shutdown led to an increase in carbon dioxide emissions around 36.2 megatons per year, and killed 1100 people a year through increased air pollution. As they shut down nuclear power, Germany made heavy investments in renewable energy, but those same investments could have "cut much deeper into fossil fuel energy" if the nuclear generation had still been online.[72][73]

Aligning with the end of the 2021 COP26 climate talks, the operators of Germany's six remaining nuclear power stations, utilities E.ON, RWE, and EnBW, rejected calls to keep the plants in operation beyond their scheduled shutdowns at the end of 2022.[74] However, in reaction to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine the debate about whether to extend the life of the three remaining reactors or whether to restart operation in the three reactors shut down at the end of 2021 (whose dismantling hasn't started yet) once more came to the forefront and operators said that it would be possible to extend the life of those reactors under certain conditions.[75][76]

In July 2022, faced with a looming energy crisis, the German parliament voted to reactivate closed coal power plants.[77]

Of the 17 nuclear power plants Germany had at its peak, three remain in operation as of 2022: Isar 2, Emsland and Neckarwestheim 2, which are operated by German energy firms E.ON (EONGn.DE), RWE (RWEG.DE) and EnBW (EBKG.DE), respectively. Current legislation means that the remaining operators will lose the right to operate their plants beyond Dec. 31, 2022, the effective end-date for the stations. Germany's network regulator (part of the Economy Ministry), could decide that they are critical to the security of power supply (both electricity and nuclear transmutation) and allow them to run for longer.[78]

Italy

Nuclear power phase-out commenced in Italy in 1987, one year after the Chernobyl accident. Following a referendum in that year, Italy's four nuclear power plants were closed down, the last in 1990. A moratorium on the construction of new plants, originally in effect from 1987 until 1993, has since been extended indefinitely.[79]

In recent years, Italy has been an importer of nuclear-generated electricity, and its largest electricity utility Enel S.p.A. has been investing in reactors in both France and Slovakia to provide this electricity in the future, and also in the development of the EPR technology.

In October 2005, there was a seminar sponsored by the government about the possibility of reviving Italian nuclear power.[80] The fourth cabinet led by Silvio Berlusconi tried to implement a new nuclear plan but a referendum held in June 2011 stopped any project.

Philippines

In the Philippines, in 2004, President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo outlined her energy policy. She wants to increase indigenous oil and gas reserves through exploration, develop alternative energy resources, enforce the development of natural gas as a fuel and coco diesel as alternative fuel, and build partnerships with Saudi Arabia, Asian countries, China and Russia. She also made public plans to convert the (never completed) Bataan Nuclear Power Plant into a gas-powered facility.[81]

South Korea

In 2017, responding to widespread public concerns after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan, the high earthquake risk in South Korea, and a 2013 nuclear scandal involving the use of counterfeit parts, the new government of President Moon Jae-in had decided to gradually phase out nuclear power in South Korea. Such decision, however, was met with widespread criticism regarding its political transparency and various doubts regarding its process. This was especially highlighted when the construction of Shin Gori unit 5 and 6 were unilaterally stopped by the government. Being faced with stark criticism, the construction of Shin Gori unit 5 and 6 were eventually restarted.

Later into the administrative period, Moon Jae-in government and its nuclear phase-out policy is facing heavier criticism than before, from both the opposing parties as well as general public due to lack of realistic alternative, consequential increase in electricity price, negative effects on the related industries, public consensus of needs to reduce carbon footprint and the decrease of popularity due to other political and economical failures. Surveys from 2021 shows that the support for nuclear phase out has drastically reduced, although the details differ from majority support to majority disapproval depending on the survey.[82][83] President Moon reversed his government's nuclear phaseout policy just before the election in February 2022.[84]

In the 2022 election candidate Yoon Seok-Yeol promised to cancel the phase out if elected and continue running all plants as long as they safely could be develop new technology and become a global export powerhouse. Yoon went on to win a very close election in what was seen as a big win for the nuclear sector [85]

Sweden

A year after the Three Mile Island accident in 1979 the 1980 Swedish nuclear power referendum was held. It led to the Swedish parliament deciding that no further nuclear power plants should be built, and that a nuclear power phase-out should be completed by 2010. On 5 February 2009, the Government of Sweden effectively ended the phase-out policy.[86] In 2010, Parliament approved for new reactors to replace existing ones.[87]

The nuclear reactors at the Barsebäck Nuclear Power Plant were shut down between 1999 and 2005. In October 2015, corporations running the nuclear plants decided to phase out two reactors at Oskarshamn[88] and two at Ringhals,[89] reducing the number of remaining reactors from 12 in 1999 to 6 in 2020.

An opinion poll in April 2016 showed that about half of Swedes want to phase out nuclear power, 30 percent want its use continued, and 20 percent are undecided.[90] Prior to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011, "a clear majority of Swedes" had been in favour of nuclear power.[90] In June 2016, the opposition parties and the government reached an agreement on Swedish nuclear power.[91] The agreement is to phase out the output tax on nuclear power, and allow ten new replacement reactors to be built at current nuclear plants.[92]

Since then, public support of nuclear energy has grown, with a majority of people in favor of nuclear power.[93] Those in favor of decommissioning nuclear has dropped to a record low of 11 percent.

Switzerland

As of 2013, the five operational Swiss nuclear reactors were Beznau 1 and 2, Gösgen, Leibstadt, and Mühleberg—all located in the German speaking part of the country. Nuclear power accounted for 36.4% of the national electricity generation, while 57.9% came from hydroelectricity. The remaining 5.7% was generated by other conventional and non-hydro renewable power stations.[94]

On 25 May 2011, the Federal Council decided on a slow phase-out by not extending running times or building new power plants.[95] The first power plant, Mühleberg, was shut down on 20 December 2019, the last will stop running in 2034.[96]

In 2018, the International Energy Agency has warned that Switzerland's phased withdrawal from nuclear power presents challenges for maintaining its electricity security. They caution that Switzerland will be increasingly relying on imports from its European neighbours to meet electricity demand, especially during the winter months when low water levels impact production from hydro plants.[97]

There have been many Swiss referendums on the topic of nuclear energy, beginning in 1979 with a citizens' initiative for nuclear safety, which was rejected. In 1984, there was a vote on an initiative "for a future without further nuclear power stations" with the result being a 55 to 45% vote against. On 23 September 1990, Switzerland had two more referendums about nuclear power. The initiative "stop the construction of nuclear power stations", which proposed a ten-year moratorium on the construction of new nuclear power plants, was passed with 54.5% to 45.5%. The initiative for a phase-out was rejected with by 53% to 47.1%. In 2000, there was a vote on a green tax for support of solar energy. It was rejected by 67–31%. On 18 May 2003, there were two referendums: "Electricity without Nuclear", asking for a decision on a nuclear power phase-out, and "Moratorium Plus", for an extension of the earlier-decided moratorium on the construction of new nuclear power plants. Both were turned down. The results were: Moratorium Plus: 41.6% Yes, 58.4% No; Electricity without Nuclear: 33.7% Yes, 66.3% No.[98]

The program of the "Electricity without Nuclear" petition was to shut down all nuclear power stations by 2033, starting with Unit 1 and 2 of Beznau nuclear power stations, Mühleberg in 2005, Gösgen in 2009, and Leibstadt in 2014. "Moratorium Plus" was for an extension of the moratorium for another ten years, and additionally a condition to stop the present reactors after 40 years of operation. In order to extend the 40 years by ten more years, another referendum would have to be held (at high administrative costs). The rejection of the Moratorium Plus had come as a surprise to many, as opinion polls before the referendum had showed acceptance. Reasons for the rejections in both cases were seen as the worsened economic situation.[99]

Other significant places

Europe

In Spain a moratorium was enacted by the socialist government in 1983[100][101] and in 2006 plans for a phase-out of seven reactors were being discussed anew.[102]

In Ireland, a nuclear power plant was first proposed in 1968. It was to be built during the 1970s at Carnsore Point in County Wexford. The plan called for first one, then ultimately four plants to be built at the site, but it was dropped after strong opposition from environmental groups, and Ireland has remained without nuclear power since. Despite opposing nuclear power (and nuclear fuel reprocessing at Sellafield), Ireland is to open an interconnector to the mainland UK to buy electricity, which is, in some part, the product of nuclear power.

Slovenian nuclear plant in Krško (co-owned with Croatia) is scheduled to be closed by 2023, and there are no plans to build further nuclear plants. The debate on whether and when to close the Krško plant was somewhat intensified after the 2005/06 winter energy crisis. In May 2006 the Ljubljana-based daily Dnevnik claimed Slovenian government officials internally proposed adding a new 1000 MW block into Krško after the year 2020.

Greece operates only a single small nuclear reactor in the Greek National Physics Research Laboratory in Demokritus Laboratories for research purposes.

Serbia currently operates a single nuclear research reactor in the Vinča Institute. Previously, Vinča Institute had two active reactors: RA and RB. In the 1958, nuclear incident happened. Six workers received critical amount of radiation and one of them died. These workers received first bone marrow transplant in Europe. After, Chernobyl disaster, in 1989, moratorium on use of nuclear energy was in power. Later, the law officially prohibited use of nuclear energy. To this day, Directorate for Nuclear and Radiation Safety (Srbatom) is strongly opposed to any kind of nuclear energy use in Serbia or neighbouring countries.

The future expansion of nuclear power in the United Kingdom to make up 25% of electrical production was announced in March 2022.[103] The country has a number of reactors which are currently reaching the end of their working life, and the future of nuclear in the UK was uncertain. The government has now said it could approve up to eight new reactors to help reach a target of generating 24GW of the total from nuclear power plants. The UK has succeeded in reaching its targets for reduction on CO2 emissions in 2020 [104] in part thanks to nuclear power, its situation may be made worse if new nuclear power stations are not built. The UK also uses a large proportion of gas-fired power stations, which produce half the CO2 emissions as coal, but there have been recent difficulties in obtaining adequate gas supplies. In 2016 the UK government committed to support the new Hinkley Point C nuclear power station.[105] As of 2021, the Hinkley Point C is under construction and 3% over budget [106] largely due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The UK Government is also under talks with EDF Energy for a new nuclear power station at Sizewell C nuclear power station, it is also considering aid in a variety of options at Wylfa nuclear power station, Moorside nuclear power station and Bradwell B nuclear power station signifying a strong will to preserve a large portion of nuclear energy in its energy mix as an effort for further decarbonization.

The Netherlands

In the Netherlands, in 1994, the Dutch parliament voted to phase out after a discussion of nuclear waste management. The power station at Dodewaard was shut down in 1997. In 1997 the government decided to end Borssele's operating license, at the end of 2003. In 2003 the shut-down was postponed by the government to 2013.[107][108] In 2005 the decision was reversed and research in expanding nuclear power has been initiated. Reversal was preceded by the publication of the Christian Democratic Appeal's report on sustainable energy.[109] Other coalition parties then conceded. In 2006 the government decided that Borssele will remain open until 2033, if it can comply with the highest safety standards. The owners, Essent and DELTA will invest 500 million euro in sustainable energy, together with the government, money which the government claims otherwise should have been paid to the plants owners as compensation. In December 2021, the Fourth Rutte cabinet stated that it wants to prepare for the construction of two new nuclear power plants in order to reduce CO2 emissions and meet the European Union goals for tackling climate change.[110] Part of this preparation is the launch of a feasibility study, looking at the advantages and disadvantages of the use of nuclear power to tackle climate change.[111]

Australia

In Australia uranium is mined and exported for power generation though nuclear power plants are illegal domestically. Australia has very extensive, low-cost coal reserves and substantial natural gas and majority political opinion is still opposed to domestic nuclear power on both environmental and economic grounds.

Asia

Renewable energy, mainly hydropower, is gaining share.[112][113]

For North Korea, two PWRs at Kumho were under construction until that was suspended in November 2003. On 19 September 2005 North Korea pledged to stop building nuclear weapons and agreed to international inspections in return for energy aid, which may include one or more light water reactors – the agreement said "The other parties expressed their respect and agreed to discuss at an appropriate time the subject of the provision of light-water reactor" [sic].[114]

In July 2000, the Turkish government decided not to build four reactors at the controversial Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant, but later changed its mind. The official launch ceremony took place in April 2015, and the first unit is expected to be completed in 2020.[115]

Taiwan has 3 active plants and 6 reactors. Active seismic faults run across the island, and some environmentalists argue Taiwan is unsuited for nuclear plants.[116] Construction of the Lungmen Nuclear Power Plant using the ABWR design has encountered public opposition and a host of delays, and in April 2014 the government decided to halt construction.[117] Construction will be halted from July 2015 to 2017 in order to allow time for a referendum to be held.[118] The 2016 election was won by a government with stated policies that included phasing out nuclear power generation.[119]

India has 20 reactors operating, 6 reactors under construction, and is planning an additional 24.[120]

Vietnam had developed detailed plans for 2 nuclear power plants with 8 reactors, but in November 2016 decided to abandon nuclear power plans as they were "not economically viable because of other cheaper sources of power."[121]

Japan

Once a nuclear proponent, Prime Minister Naoto Kan became increasingly anti-nuclear following the Fukushima nuclear disaster. In May 2011, he closed the aging Hamaoka Nuclear Power Plant over earthquake and tsunami fears, and said he would freeze plans to build new reactors. In July 2011, Kan said that "Japan should reduce and eventually eliminate its dependence on nuclear energy ... saying that the Fukushima accident had demonstrated the dangers of the technology".[125] In August 2011, the Japanese government passed a bill to subsidize electricity from renewable energy sources.[126] A 2011 Japanese Cabinet energy white paper says "public confidence in safety of nuclear power was greatly damaged" by the Fukushima disaster, and calls for a reduction in the nation's reliance on nuclear power.[127] As of August 2011, the crippled Fukushima nuclear plant is still leaking low levels of radioactivity and areas surrounding it could remain uninhabitable for decades.[128]

By March 2012, one year after the disaster, all but two of Japan's nuclear reactors were shut down; some were damaged by the quake and tsunami. The following year, the last two were taken off-line. Authority to restart the others after scheduled maintenance throughout the year was given to local governments, and in all cases local opposition prevented restarting.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's government, reelected on a platform of restarting nuclear power, plans to have nuclear power account for 20 to 22 percent of the country’s total electricity supply by 2030, compared with roughly 30 percent before the disaster at the Fukushima complex.

In 2015 two reactors at Sendai nuclear power plant have been restarted.[129] In 2016 Ikata-3 restarted and in 2017 Takahama-4 restarted. In 2021 Mihama Nuclear Power Plant unit 3 was restarted.[130]

United States

The United States is, as of 2013, undergoing a practical phase-out independent of stated goals and continued official support. This is not due to concerns about the source or anti-nuclear groups, but due to the rapidly falling prices of natural gas and the reluctance of investors to provide funding for long-term projects when short term profitability of turbine power is available.

Through the 2000s a number of factors led to greatly increased interest in new nuclear reactors, including rising demand, new lower-cost reactor designs, and concerns about global climate change. By 2009, about 30 new reactors were planned, and a large number of existing reactors had applied for upgrades to increase their output. In total, 39 reactors have had their licences renewed, three Early Site Permits have been applied for, and three consortiums have applied for Combined Construction-Operating Licences under the Nuclear Power 2010 Program. In addition, the Energy Policy Act of 2005 contains incentives to further expand nuclear power.[131]

However, by 2012 the vast majority of these plans were cancelled, and several additional cancellations followed in 2013. Currently only three new reactors are under construction, and one, at Watts Bar, was originally planned in the 1970s and only under construction now. Construction of the new AP1000 design is underway at one location in the United States in Georgia . Plans for additional reactors in Florida were cancelled in 2013.

Some smaller reactors operating in deregulated markets have become uneconomic to operate and maintain, due to competition from generators using low priced natural gas, and may be retired early.[132] The 556 MWe Kewaunee Power Station is being closed 20 years before license expiry for these economic reasons.[133][134] Duke Energy's Crystal River 3 Nuclear Power Plant in Florida closed, as it could not recover the costs needed to fix its containment building.[135]

As a result of these changes, after reaching peak production in 2007, US nuclear capacity has been undergoing constant reduction every year.

In 2021, Indian Point Energy Center, the last remaining nuclear power plant in the New York City metropolitan area, was shut down.[136] Environmental groups celebrated the decision to close the plant, while critics pointed to the sites generation being replaced by two gas fired power plants resulting in an increase of fossil fuel consumption.[137][138]

Pros and cons of nuclear power

The nuclear debate

The nuclear power debate is about the controversy[139][140][141][142][143] which has surrounded the deployment and use of nuclear fission reactors to generate electricity from nuclear fuel for civilian purposes. The debate about nuclear power peaked during the 1970s and 1980s, when it "reached an intensity unprecedented in the history of technology controversies", in some countries.[144][145]

Proponents of nuclear energy argue that nuclear power is a sustainable energy source which reduces carbon emissions and can increase energy security if its use supplants a dependence on imported fuels.[146] Proponents cite scientific studies affirming the consensus that nuclear power produces virtually no air pollution,[147] in contrast to the chief dispatchable alternative of fossil fuel. Proponents also believe that nuclear power is the only viable course to achieve energy independence for most Western countries.[148] They emphasize that the risks of storing spent fuel are small and can be further reduced by using the latest technology in newer reactors, fuel recycling, and long-lived radioisotope burn-up. For instance, spent nuclear fuel in the United States could extend nuclear power generation by hundreds of years[149] because more than 90% of spent fuel can be reprocessed.[150] The operational safety record in the Western world is excellent when compared to the other major kinds of power plants.[151]

Over 10,000 hospitals worldwide use radioisotopes in medicine, and about 90% of the procedures are for diagnosis. The radioisotope most commonly used in diagnosis is technetium-99. Some 40 million procedures per year, accounting for about 80% of all nuclear medicine procedures and 85% of diagnostic scans in nuclear medicine worldwide. The main radioisotopes such as Tc-99m cannot effectively be produced without reactors.[152][153] Most smoke detectors use americium-241, meaning every American home uses these common radioisotopes to ensure the safety of their loved ones.[154]

Opponents say that nuclear power poses many threats to people and the environment. These threats include health risks and environmental damage from uranium mining, processing and transport, the risk of nuclear weapons proliferation or sabotage, and the problem of radioactive nuclear waste.[155][156][157] They also contend that reactors themselves are enormously complex machines where many things can and do go wrong, and there have been many serious nuclear accidents.[158][159] Critics do not believe that these risks can be reduced through new technology.[160] They argue that when all the energy-intensive stages of the nuclear fuel chain are considered, from uranium mining to nuclear decommissioning, nuclear power is not a low-carbon electricity source.[161][162][163] These pieces of criticism have however largely been quelled by the IPCC which indicated in 2014 that nuclear energy was a low carbon energy production technology, comparable to wind and lower than solar in that regard.[164]

Economics

The economics of new nuclear power plants is a controversial subject, since there are diverging views on this topic, and multi-billion dollar investments ride on the choice of an energy source. Nuclear power plants typically have high capital costs for building the plant, but low direct fuel costs (with much of the costs of fuel extraction, processing, use and long term storage externalized). Therefore, comparison with other power generation methods is strongly dependent on assumptions about construction timescales and capital financing for nuclear plants. Cost estimates also need to take into account plant decommissioning and nuclear waste storage costs. On the other hand measures to mitigate global warming, such as a carbon tax or carbon emissions trading, may favor the economics of nuclear power versus fossil fuels.

In recent years there has been a slowdown of electricity demand growth and financing has become more difficult, which affects large projects such as nuclear reactors, with very large upfront costs and long project cycles which carry a large variety of risks.[165] In Eastern Europe, a number of long-established projects are struggling to find finance, notably Belene in Bulgaria and the additional reactors at Cernavoda in Romania, and some potential backers have pulled out.[165] Where cheap natural gas is available and its future supply relatively secure, this also poses a major problem for nuclear projects.[165]

Analysis of the economics of nuclear power must take into account who bears the risks of future uncertainties. To date all operating nuclear power plants were developed by state-owned or regulated utility monopolies[166] where many of the risks associated with construction costs, operating performance, fuel price, and other factors were borne by consumers rather than suppliers. Many countries have now liberalized the electricity market where these risks, and the risk of cheaper competitors emerging before capital costs are recovered, are borne by plant suppliers and operators rather than consumers, which leads to a significantly different evaluation of the economics of new nuclear power plants.[167]

Following the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, costs are likely to go up for currently operating and new nuclear power plants, due to increased requirements for on-site spent fuel management and elevated design basis threats.[168]

Environment

The environmental impact of nuclear power results from the nuclear fuel cycle, operation, and the effects of nuclear accidents.

The greenhouse gas emissions from nuclear fission power are small relative to those associated with coal, oil, gas, and biomass. They are about equal to those associated with wind and hydroelectric.[169]

The routine health risks from nuclear fission power are very small relative to those associated with coal, oil, gas, solar, biomass, wind and hydroelectric.[170]

However, there is a "catastrophic risk" potential if containment fails,[171] which in nuclear reactors can be brought about by over-heated fuels melting and releasing large quantities of fission products into the environment. The public is sensitive to these risks and there has been considerable public opposition to nuclear power. Even so, in comparing the fatalities for major accidents alone in the energy sector it is still found that the risks associated with nuclear power are extremely small relative to those associated with coal, oil, gas and hydroelectric.[170] For the operation of a 1000-MWe nuclear power plant the complete nuclear fuel cycle, from mining to reactor operation to waste disposal, the radiation dose is cited as 136 person-rem/year, the dose is 490 person-rem/year for an equivalent coal-fired power plant.[172]

The 1979 Three Mile Island accident and 1986 Chernobyl disaster, along with high construction costs, ended the rapid growth of global nuclear power capacity.[171] A further disastrous release of radioactive materials followed the 2011 Japanese tsunami which damaged the Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant, resulting in hydrogen gas explosions and partial meltdowns classified as a Level 7 event. The large-scale release of radioactivity resulted in people being evacuated from a 20 km exclusion zone set up around the power plant, similar to the 30 km radius Chernobyl Exclusion Zone still in effect. Subsequent scientific assessment of the health impacts of radiation has shown that these evacuations were more damaging than the radiation could have been, and recommend that the population be advised to remain in place in all but the most severe radiological release events.[173]

Accidents

The effect of nuclear accidents has been a topic of debate practically since the first nuclear reactors were constructed. It has also been a key factor in public concern about nuclear facilities.[174] Some technical measures to reduce the risk of accidents or to minimize the amount of radioactivity released to the environment have been adopted. Despite the use of such measures, human error remains, and "there have been many accidents with varying effects as well near misses and incidents".[174][175]

Benjamin K. Sovacool has reported that worldwide there have been 99 accidents at nuclear power plants.[176] Fifty-seven accidents have occurred since the Chernobyl disaster, and 57% (56 out of 99) of all nuclear-related accidents have occurred in the USA.[176] Serious nuclear power plant accidents include the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster (2011), Chernobyl disaster (1986), Three Mile Island accident (1979), and the SL-1 accident (1961). Stuart Arm states, "apart from Chernobyl, no nuclear workers or members of the public have ever died as a result of exposure to radiation due to a commercial nuclear reactor incident."[178]

The International Atomic Energy Agency maintains a website reporting recent accidents.[179]

Safety

Nuclear safety and security covers the actions taken to prevent nuclear and radiation accidents or to limit their consequences. This covers nuclear power plants as well as all other nuclear facilities, the transportation of nuclear materials, and the use and storage of nuclear materials for medical, power, industry, and military uses.

Although there is no way to guarantee that a reactor will always be designed, built and operated safely, the nuclear power industry has improved the safety and performance of reactors, and has proposed safer reactor designs, though many of these designs have yet to be tested at industrial or commercial scales.[180] Mistakes do occur and the designers of reactors at Fukushima in Japan did not anticipate that a tsunami generated by an earthquake would disable the backup systems that were supposed to stabilize the reactor after the earthquake.[181][182] According to UBS AG, the Fukushima I nuclear accidents have cast doubt on whether even an advanced economy like Japan can master nuclear safety.[183] Catastrophic scenarios involving terrorist attacks are also conceivable.[180]

An interdisciplinary team from MIT have estimated that given the expected growth of nuclear power from 2005 – 2055, at least four serious nuclear accidents would be expected in that period.[184][185] To date, there have been five serious accidents (core damage) in the world since 1970 (one at Three Mile Island in 1979; one at Chernobyl in 1986; and three at Fukushima-Daiichi in 2011), corresponding to the beginning of the operation of generation II reactors. This leads to on average one serious accident happening every eight years worldwide.[182] Despite these accidents and public opinion, the safety record of nuclear power, in terms of lives lost (ignoring nonfatal illnesses) per unit of electricity delivered, is better than every other major source of power in the world, and on par with solar and wind.[170][186][187]

Energy transition

.png.webp)

Energy transition is the shift by several countries to sustainable economies by means of renewable energy, energy efficiency and sustainable development. This trend has been augmented by diversifying electricity generation and allowing homes and businesses with solar panels on their rooftops to sell electricity to the grid. In the future this could "lead to a majority of our energy coming from decentralized solar panels and wind turbines scattered across the country" rather than large power plants.[189] The final goal of German proponents of a nuclear power phase-out is the abolishment of coal and other non-renewable energy sources.[190]

Issues exist that currently prevent a shift over to 100% renewable technologies. There is debate over the environmental impact of solar power, and the environmental impact of wind power. Some argue that the pollution produced and requirement of rare-earth elements offsets many of the benefits compared to other alternative power sources such as hydroelectric, geothermal, and nuclear power.[191]

See also

- Nuclear renaissance

- Anti-nuclear movement

- Energy conservation

- Energy development

- Fossil fuel phase-out

- List of energy topics

- Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

- Nuclear energy policy

- Nuclear power controversy

- Nuclear power in France

- Renewable energy commercialization

- Wind power

Notes and references

- IAEA (2011). "Power Reactor Information System - Highlights". (subscription required)

- Annika Breidthardt (30 May 2011). "German government wants nuclear exit by 2022 at latest". Reuters.

- "Jahreswechsel: Drei weitere Kernkraftwerke gehen vom Netz". www.zdf.de.

- "Italy Nuclear Referendum Results". 13 June 2011. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012.

- Henry Sokolski (28 November 2011). "Nuclear Power Goes Rogue". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 18 December 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- Tsuyoshi Inajima & Yuji Okada (28 October 2011). "Nuclear Promotion Dropped in Japan Energy Policy After Fukushima". Bloomberg.

- Kharecha, Pushker A.; Sato, Makiko (1 September 2019). "Implications of energy and CO2 emission changes in Japan and Germany after the Fukushima accident". Energy Policy. 132: 647–653. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.05.057. S2CID 197781857 – via ScienceDirect.

- "Japan's carbon goal is based on restarting 30 nuclear reactors". 17 October 2021.

- "Nuclear power: When the steam clears". The Economist. 24 March 2011.

- Duroyan Fertl (5 June 2011). "Germany: Nuclear power to be phased out by 2022". Green Left.

- Erika Simpson and Ian Fairlie, Dealing with nuclear waste is so difficult that phasing out nuclear power would be the best option, Lfpress, 26 February 2016.

- "Difference Engine: The nuke that might have been". The Economist. 11 November 2013.

- James Kanter (25 May 2011). "Switzerland Decides on Nuclear Phase-Out". New York Times.

- Strauss, Marine (7 March 2022). "Belgian Greens make U-turn to consider nuclear plants extension". Reuters – via www.reuters.com.

- "404". BNN.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - "Philippines approves revival of nuclear power to help replace coal". Reuters. 3 March 2022.

- "Greece, Bulgaria in talks for nuclear power supply deal | ENERGYPRESS".

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Emerging Nuclear Energy Countries | New Nuclear Build Countries - World Nuclear Association". world-nuclear.org. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- "The Database on Nuclear Power Reactors". IAEA.

- Herbert P. Kitschelt. Political Opportunity and Political Protest: Anti-Nuclear Movements in Four Democracies British Journal of Political Science, Vol. 16, No. 1, 1986, p. 71.

- Helen Caldicott (2006). Nuclear Power is Not the Answer to Global Warming or Anything Else, Melbourne University Press, ISBN 0-522-85251-3, p. xvii

- Netherlands: Court case on closure date Borssele NPP, article from anti-nuclear organization (WISE), dated 29 June 2001.

- Nuclear Power in the World Energy Outlook, by the Uranium Institute, 1999.

- Anti-nuclear resolution of the Austrian Parliament Archived 23 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine, as summarised by an anti-nuclear organisation (WISE).

- Nuclear news from Poland Archived 16 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine, article from the Web site of the European Nuclear Society, April 2005.

- Germany Starts Nuclear Energy Phase-Out, article from Deutsche Welle, 14 November 2003.

- James Kanter. In Finland, Nuclear Renaissance Runs Into Trouble New York Times, 28 May 2009.

- James Kanter. Is the Nuclear Renaissance Fizzling? Green, 29 May 2009.

- Rob Broomby. Nuclear dawn delayed in Finland BBC News, 8 July 2009.

- "Finnish EPR starts supplying electricity : New Nuclear - World Nuclear News". www.world-nuclear-news.org.

- "Nuclear power in a clean energy system". www.iea.org. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- Dittmar, Michael (17 August 2010). "Taking stock of nuclear renaissance that never was". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- "Coalition of Nuclear-Free Countries". WISE News Communique. 26 September 1997. Archived from the original on 23 February 2006. Retrieved 2006-05-19.

- "AKW Zwentendorf | Virtuelle Tour". www.zwentendorf.com.

- "Zwentendorf: Das Atomkraftwerk, das nie anlief". 19 January 2022.

- Ruffles, Philip; Michael Burdekin; Charles Curtis; Brian Eyre; Geoff Hewitt; William Wilkinson (July 2003). "An Essential Programme to Underpin Government Policy on Nuclear Power" (PDF). Nuclear Task Force. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- Henry, Alain (12 July 2005), Quelle énergie pour un développement durable ?, Working Paper 14-05 (in French), Federal Planning Bureau

- Kanter, James (10 August 2005). "Big French Utility Offers a Full Buyout in Belgium". The New York Times.

- "Belgium plans to phase out nuclear power". BBC News. 31 October 2011.

- Addicted to nuclear energy? < Belgian news | Expatica Belgium Archived 19 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Expatica.com. Retrieved on 2011-06-04.

- "Belgium maintains nuclear phase-out policy". World Nuclear News. 4 April 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- "Extended operation of two Belgian reactors approved : Nuclear Policies - World Nuclear News". www.world-nuclear-news.org.

- "Belgium to Extend Life of Nuclear Reactors for Another Decade". BNN Bloomberg. 19 March 2022.

- "MYRRHA protons accelerated successfully | SCK CEN". www.sckcen.be.

- German nuclear energy phase-out begins with first plant closure. Terradaily.com (2003-11-14). Retrieved on 2011-06-04.

- "PDF" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2004.

- "Strom-Report | Statistiken & Infografiken: Energie & Umwelt". STROM-REPORT.

- http://www.pds-coesfeld.de/anti%20atom.gronau2.htm

- Kommunikation Wissenschaft Archived 22 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- 'Nuclear phase-out in Germany and the Challenges for Nuclear Regulation' Archived 20 May 2005 at the Wayback Machine. Bmu.de. Retrieved on 2011-06-04.

- "Germany split over green energy". BBC News. 25 February 2005.

- Belkin, Paul; Ratner, Michael; Welt, Cory; Taylor, Beryl E. (18 March 2019). "Nord Stream 2: A Fait Accompli? [March 18, 2019]". Library of Congress. Congressional Research Service – via www.hsdl.org.

- Belkin, Paul; Welt, Cory; Ratner, Michael (10 March 2022). "Russia's Nord Stream 2 Natural Gas Pipeline to Germany Halted [Updated March 10, 2022]". Library of Congress. Congressional Research Service – via www.hsdl.org.

- "Renewable Energy Germany | German Energy Transition". STROM-REPORT.

- Caroline Jorant (July 2011). "The implications of Fukushima: The European perspective". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 67 (4): 15. doi:10.1177/0096340211414842. S2CID 144198768. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- Knight, Ben (15 March 2011). "Merkel shuts down seven nuclear reactors". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- "Anti-nuclear demos across Europe on Fukushima anniversary". Euronews. 11 March 2011. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology (BMWi); Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) (28 September 2010). Energy concept for an environmentally sound, reliable and affordable energy supply (PDF). Berlin, Germany: Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology (BMWi). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- The Federal Government's energy concept of 2010 and the transformation of the energy system of 2011 (PDF). Bonn, Germany: Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, and Nuclear Safety (BMU). October 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- John Broder (10 October 2011). "The Year of Peril and Promise in Energy Production". New York Times.

- "Siemens to quit nuclear industry". BBC News. 18 September 2011.

- "IAEA sees slow nuclear growth post Japan". UPI. 23 September 2011.

- "Supply security is even more stable despite nuclear phaseout — fossil reserve power is replaceable" (PDF) (Press release). Hamburg, Germany: Greenpeace Energy. 5 September 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- Huneke, Fabian; Lizzi, Philipp; Lenck, Thorsten (August 2016). The consequences so far of Germany's nuclear phaseout on the security of energy supply — A brief analysis commissioned by Greenpeace Energy eG in Germany (PDF). Berlin, Germany: Energy Brainpool. Retrieved 8 September 2016. This reference provides a good overview of the phaseout.

- "Showdown in Germany's nuclear phase-out". Clean Energy Wire (CLEW). Berlin, Germany. 10 October 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- "Nuclear plant operators continue lawsuits". Clean Energy Wire (CLEW). Berlin, German. 8 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- "German utilities eligible for "adequate" nuclear exit compensation". Clean Energy Wire (CLEW). Berlin, Germany. 6 December 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- "The thirteenth amendment to the Atomic Energy Act is for the most part compatible with the Basic Law" (Press release). Karlsruhe, Germany: Bundesverfassungsgericht. 6 December 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- "German utilities win compensation for nuclear phaseout". Deutsche Welle (DW). Bonn, Germany. 5 December 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2016. Provides a history of the nuclear exit.

- "Atomausstieg: Konzerne klagen weiter – auf Auskunft" [Nuclear exit: corporations sue further - for information]. Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Berlin, German. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- "The cost of Germany turning off nuclear power: Thousands of lives". Grist. 8 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Jarvis, Stephen; Deschenes, Olivier; Jha, Akshaya (December 2019). "The Private and External Costs of Germany's Nuclear Phase-Out" (PDF). National Bureau of Economic Research. Cambridge, MA: w26598. doi:10.3386/w26598. S2CID 211027218.

-

Meza, Edgar (12 November 2021). "German nuclear power operators reject calls to keep running plants longer". Clean Energy Wire (CLEW). Berlin, Germany. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- "FDP spricht über Reaktivierung stillgelegter Atomkraftwerke - hamburg.de". Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- "Werden stillgelegte Atomkraftwerke reaktiviert? Energieversorgung wegen Ukraine-Krieg bedroht".

- Kate Connolly (8 July 2022). "Germany to reactivate coal power plants as Russia curbs gas flow". The Guardian.

- Steitz, Christoph; Wacket, Markus (28 February 2022). "Explainer: Could Germany keep its nuclear plants running?". Reuters – via www.reuters.com.

- "Italy - National Energy Policy and Overview". Archived from the original on 6 September 2005. Retrieved 17 August 2005.

- "Prospettive dell'energia nucleare in Italia". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "The Manila Times Internet Edition | OPINION > Why don?t we just nuke it?". www.manilatimes.net. Archived from the original on 23 February 2006.

- Jung, Chan (28 July 2021). "[한국리서치] 문재인 정부 '탈원전 정책방향' '찬성56%-반대32%'". Polinews. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- Lee, Jun-ki (13 September 2021). "설득력 잃은 탈원전…국민 70% "원전 찬성"". Naver News. Digital News. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- "Moon's turnaround on nuclear power leaves many stumped". koreajoongangdaily.joins.com. 1 March 2022.

- Lee, Joyce (11 March 2022). "South Korea's nuclear power at inflection point as advocate wins presidency". Reuters.

- Borgenäs, Johan (11 November 2009). "Sweden Reverses Nuclear Phase-out Policy". Nuclear Threat Initiative.

- "Sweden to replace existing nuclear plants with new ones". BBC News Online. 18 June 2010.

- "OKG - Beslut fattat om förtida stängning av O1 och O2". Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- "R1 and R2 in operation until 2020 and 2019 - Vattenfall". Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- "30 years after Chernobyl: Half of Swedes oppose nuclear power". Sveriges Radio. 26 April 2016.

- "Sweden strikes deal to continue nuclear power". The Local. 10 June 2016.

- Juhlin, Johan (10 June 2016). "Klart i dag: så blir den svenska energipolitiken". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). Sveriges Television. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- "Swedish support for nuclear continues to grow, poll shows". Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- Swiss Federal Office of Energy (SFOE) Electricity statistics 2013 (in French and German) Archived 29 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine, 23 June 2014

- «Mutiger Entscheid» bis «Kurzschlusshandlung» (Politik, Schweiz, NZZ Online). Nzz.ch. Retrieved on 2011-06-04.

- Schweiz plant Atomausstieg – Schweiz – derStandard.at › International. Derstandard.at. Retrieved on 2011-06-04.

- "IEA warns of challenges from Swiss nuclear phase-out : Nuclear Policies - World Nuclear News". www.world-nuclear-news.org.

- Bundesamt für Energie BFE – Startseite . Energie-schweiz.ch. Retrieved on 2011-06-04.

- www.cnfc.or.jp https://web.archive.org/web/20041213102612/http://www.cnfc.or.jp/plutonium/pl42/e/cnfc_report.html. Archived from the original on 13 December 2004.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "Spain halts nuclear power". WISE News Communique. 24 May 1991. Retrieved 19 May 2006.

- "Nuclear Power in Spain". World Nuclear Association. May 2006. Archived from the original on 22 February 2006. Retrieved 19 May 2006.

- "Behauptung 1: Der Atomausstieg ist ein deutscher "Sonderweg"". Archived from the original on 18 February 2005. Retrieved 19 May 2006.

- "PM to put nuclear power at heart of UK 's energy strategy". the Guardian. 6 April 2022.

- "The UK's greenhouse gas emissions in 2020 were 51% below 1990 levels". ORG. 15 September 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- "Government confirms Hinkley Point C project following new agreement in principle with EDF". GOV.UK. 15 September 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- "Higher costs for HPC". COM. 15 September 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- "2003-05-22 Nucleons week 22 May 2003 ; Borssele's political lifetime extended to 2013 by new coalition". www.kerncentrale.nl. Archived from the original on 23 February 2005.

- "NNI - No Nukes Inforesource". www.ecology.at. Archived from the original on 12 June 2007.

- "World Nuclear Association | News | Newsletter | July - August 2005". www.world-nuclear.org. Archived from the original on 23 September 2006.

- "Nederland wil twee nieuwe kerncentrales bouwen". De Standaard (in Flemish). Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- "Dit weten we van de miljardenplannen van het aanstaande kabinet-Rutte IV". nos.nl (in Dutch). 13 December 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- EIA – 1000 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20585. Eia.doe.gov. Retrieved on 2011-06-04. Archived 1 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Article Commentary: A Sustained Reaction". 1 November 2005. Archived from the original on 28 September 2006.

- "N. Korea Agrees to Dismantle Nuke Programs - Yahoo! News". news.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 20 September 2005.

- "Ground broken for Turkey's first nuclear power plant". World Nuclear News. 15 April 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- Andrew Jacobs (12 January 2012). "Vote Holds Fate of Nuclear Power in Taiwan". New York Times. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Taiwan to halt construction of fourth nuclear power plant". Reuters. 28 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- Lin, Sean (4 February 2015). "AEC approves plan to shutter fourth nuclear facility". Taipei Times. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- "EDITORIAL: Taiwan bows to public opinion in pulling plug on nuclear power". The Asahi Shimbun. 31 October 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "International - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". www.eia.gov.

- "Vietnam ditches nuclear power plans". Deutsche Welle. Associated Press. 10 November 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Martin Fackler (1 June 2011). "Report Finds Japan Underestimated Tsunami Danger". New York Times.

- "Thousands march against nuclear power in Tokyo". USA Today. September 2011.

- David H. Slater (9 November 2011). "Fukushima women against nuclear power: finding a voice from Tohoku". The Asia-Pacific Journal. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014.

- Hiroko Tabuchi (13 July 2011). "Japan Premier Wants Shift Away From Nuclear Power". New York Times.

- Chisaki Watanabe (26 August 2011). "Japan Spurs Solar, Wind Energy With Subsidies, in Shift From Nuclear Power". Bloomberg.

- Tsuyoshi Inajima & Yuji Okada (28 October 2011). "Nuclear Promotion Dropped in Japan Energy Policy After Fukushima". Bloomberg.

- "Areas near Japan nuclear plant may be off limits for decades". Reuters. 27 August 2011.

- "Kyushu restarts second reactor at Sendai plant under tighter Fukushima-inspired rules". The Japan Times Online. 15 October 2015. ISSN 0447-5763. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- "Japan allows 1st restarts of nuclear reactors older than 40 years". Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- "US Nuclear Power Industry". Archived from the original on 22 May 2006. Retrieved 29 April 2006.

- "Some merchant nuclear plants could face early retirement: UBS". Platts. 9 January 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- "Dominion To Close, Decommission Kewaunee Power Station". Dominion. 22 October 2012. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- Caroline Peachey (1 January 2013). "Why are North American plants dying?". Nuclear Engineering International. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ""Crystal River Nuclear Plant to be retired; company evaluating sites for potential new gas-fueled generation". 5 February 2013". Archived from the original on 22 October 2013.

- "New York's Indian Point nuclear power plant closes after 59 years of operation - Today in Energy - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". www.eia.gov. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- McGeehan, Patrick (12 April 2021). "Indian Point Is Shutting Down. That Means More Fossil Fuel". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- April 28; Kennedy, 2021 Kit. "Indian Point Is Closing, but Clean Energy Is Here to Stay". NRDC. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- "Sunday Dialogue: Nuclear Energy, Pro and Con". New York Times. 25 February 2012.

- MacKenzie, James J. (December 1977). "Review of The Nuclear Power Controversy by Arthur W. Murphy". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 52 (4): 467–8. doi:10.1086/410301. JSTOR 2823429.

- Walker, J. Samuel (10 January 2006). Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective. University of California Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 9780520246836.

- In February 2010 the nuclear power debate played out on the pages of the New York Times, see A Reasonable Bet on Nuclear Power and Revisiting Nuclear Power: A Debate and A Comeback for Nuclear Power?

- In July 2010 the nuclear power debate again played out on the pages of the New York Times, see We’re Not Ready Nuclear Energy: The Safety Issues

- Kitschelt, Herbert P. (1986). "Political Opportunity and Political Protest: Anti-Nuclear Movements in Four Democracies" (PDF). British Journal of Political Science. 16 (1): 57. doi:10.1017/S000712340000380X. S2CID 154479502.

- Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press.

- U.S. Energy Legislation May Be `Renaissance' for Nuclear Power.

- Review, Energy Industry (23 November 2021). "UNECE: Nuclear is the Lowest Carbon Electricity Source".

- "Books".

- Rhodes, Richard (19 July 2018). "Why Nuclear Power Must Be Part of the Energy Solution". Yale Environment 360. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- Ling, Katherine (18 May 2009). "Is the solution to the U.S. nuclear waste problem in France?". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- Bernard Cohen. "The Nuclear Energy Option". Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- "Radioisotopes in Medicine | Nuclear Medicine - World Nuclear Association". world-nuclear.org.

- "Medical Uses of Nuclear Materials".

- "Backgrounder on Smoke Detectors". NRC Web.

- "Nuclear Energy is not a New Clear Resource". Theworldreporter.com. 2 September 2010.

- Greenpeace International and European Renewable Energy Council (January 2007). Energy Revolution: A Sustainable World Energy Outlook Archived 6 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine, p. 7.

- Giugni, Marco (2004). Social protest and policy change: ecology, antinuclear, and peace movements in comparative perspective. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 44–. ISBN 9780742518278.

- Stephanie Cooke (2009). In Mortal Hands: A Cautionary History of the Nuclear Age, Black Inc., p. 280.

- Sovacool, Benjamin K. (2008). "The costs of failure: A preliminary assessment of major energy accidents, 1907–2007". Energy Policy. 36 (5): 1802–20. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2008.01.040.

- Jim Green . Nuclear Weapons and 'Fourth Generation' Reactors Chain Reaction, August 2009, pp. 18-21.

- Kleiner, Kurt (October 2008). "Nuclear energy: assessing the emissions" (PDF). Nature Climate Change. 2 (810): 130–1. doi:10.1038/climate.2008.99.

- Mark Diesendorf (2007). Greenhouse Solutions with Sustainable Energy, University of New South Wales Press, p. 252.

- Mark Diesendorf. Is nuclear energy a possible solution to global warming? Archived 22 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "IPCC Report 2014 Chapter 7" (PDF). IPCC. 2014.

- Kidd, Steve (21 January 2011). "New reactors—more or less?". Nuclear Engineering International. Archived from the original on 12 December 2011.

- Ed Crooks (12 September 2010). "Nuclear: New dawn now seems limited to the east". Financial Times. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- The Future of Nuclear Power. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 2003. ISBN 0-615-12420-8. Retrieved 10 November 2006.

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2011). "The Future of the Nuclear Fuel Cycle" (PDF). p. xv.

- "Comparison of Lifecycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Various Electricity Generation Sources" (PDF).

- Economic Analysis of Various Options of Electricity Generation - Taking into Account Health and Environmental Effects, based on EU ExterneE Project data Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- International Panel on Fissile Materials (September 2010). "The Uncertain Future of Nuclear Energy" (PDF). Research Report 9. p. 1.

- https://www.ornl.gov/sites/default/files/ORNL%20Review%20v26n3-4%201993.pdf pg28

- Waddington, I.; Thomas, P. J.; Taylor, R. H.; Vaughan, G. J. (1 November 2017). "J-value assessment of relocation measures following the nuclear power plant accidents at Chernobyl and Fukushima Daiichi". Process Safety and Environmental Protection. 112: 16–49. doi:10.1016/j.psep.2017.03.012 – via ScienceDirect.

- M.V. Ramana. Nuclear Power: Economic, Safety, Health, and Environmental Issues of Near-Term Technologies, Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 2009, 34, p. 136.

- Matthew Wald (29 February 2012). "The Nuclear Ups and Downs of 2011". New York Times.

- Benjamin K. Sovacool. A Critical Evaluation of Nuclear Power and Renewable Electricity in Asia Journal of Contemporary Asia, Vol. 40, No. 3, August 2010, pp. 393–400.

- Arm, Stuart T. (July 2010). "Nuclear Energy: A Vital Component of Our Energy Future" (PDF). Chemical Engineering Progress. New York, NY: American Institute of Chemical Engineers: 27–34. ISSN 0360-7275. OCLC 1929453. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- "IAEA Publications". Archived from the original on 23 November 2007. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- Jacobson, Mark Z. & Delucchi, Mark A. (2010). "Providing all Global Energy with Wind, Water, and Solar Power, Part I: Technologies, Energy Resources, Quantities and Areas of Infrastructure, and Materials" (PDF). Energy Policy. p. 6.

- Hugh Gusterson (16 March 2011). "The lessons of Fukushima". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013.

- Diaz Maurin, François (26 March 2011). "Fukushima: Consequences of Systemic Problems in Nuclear Plant Design" (PDF). Economic & Political Weekly (Mumbai). 46 (13): 10–12.

- James Paton (4 April 2011). "Fukushima Crisis Worse for Atomic Power Than Chernobyl, UBS Says". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011.

- Benjamin K. Sovacool (January 2011). "Second Thoughts About Nuclear Power" (PDF). National University of Singapore. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2013.

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2003). "The Future of Nuclear Power" (PDF). p. 48.

- "Dr. MacKay "Sustainable Energy without the hot air" page 168. Data from studies by the Paul Scherrer Institute including non EU data". Inference.phy.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- World Nuclear Association. Safety of Nuclear Power Reactors Archived 4 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- Ipsos 2011, p. 3

- "The Bumpy Road to Energy Deregulation". EnPowered. 28 March 2016. Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- Federal Ministry for the Environment (29 March 2012). Langfristszenarien und Strategien für den Ausbau der erneuerbaren Energien in Deutschland bei Berücksichtigung der Entwicklung in Europa und global [Long-term Scenarios and Strategies for the Development of Renewable Energy in Germany Considering Development in Europe and Globally] (PDF). Berlin, Germany: Federal Ministry for the Environment (BMU). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2012.

- "Advantages and Challenges of Wind Power". DOE. 12 February 2015.

Further reading

- Angwin, Meredith (2020). Shorting the Grid, The Hidden Fragility of Our Electric Grid, Carnot Communications.

- Conley, Mike and Maloney, Tim (2017). ROADMAP TO NOWHERE The Myth of Powering the Nation With Renewable Energy.

- Cooke, Stephanie (2009). In Mortal Hands: A Cautionary History of the Nuclear Age, Black Inc.

- Cragin, Susan (2007). Nuclear Nebraska: The Remarkable Story of the Little County That Couldn’t Be Bought, AMACOM.

- Diesendorf, Mark (2007). Greenhouse Solutions with Sustainable Energy, University of New South Wales Press.

- Elliott, David (2007). Nuclear or Not? Does Nuclear Power Have a Place in a Sustainable Energy Future?, Palgrave.

- Falk, Jim (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press.

- Lovins, Amory B. (1977). Soft Energy Paths: Towards a Durable Peace, Friends of the Earth International, ISBN 0-06-090653-7

- Lovins, Amory B. and John H. Price (1975). Non-Nuclear Futures: The Case for an Ethical Energy Strategy, Ballinger Publishing Company, 1975, ISBN 0-88410-602-0

- Pernick, Ron and Clint Wilder (2007). The Clean Tech Revolution: The Next Big Growth and Investment Opportunity, Collins, ISBN 978-0-06-089623-2

- Price, Jerome (1982). The Antinuclear Movement, Twayne Publishers.

- Rudig, Wolfgang (1990). Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy, Longman.

- Schneider, Mycle, Steve Thomas, Antony Froggatt, Doug Koplow (August 2009). The World Nuclear Industry Status Report, German Federal Ministry of Environment, Nature Conservation and Reactor Safety.

- Sovacool, Benjamin K. (2011). Contesting the Future of Nuclear Power: A Critical Global Assessment of Atomic Energy, World Scientific.

- Walker, J. Samuel (2004). Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective, University of California Press.

- William D. Nordhaus, The Swedish Nuclear Dilemma – Energy and the Environment. 1997. Hardcover, ISBN 0-915707-84-5.

- Bernard Leonard Cohen, The Nuclear Energy Option: An Alternative for the 90's. 1990. Hardcover. ISBN 0-306-43567-5. Bernard Cohen's homepage contains the full text of the book.