Chronic traumatic encephalopathy

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a neurodegenerative disease linked to repeated trauma to the head. The encephalopathy symptoms can include behavioral problems, mood problems, and problems with thinking.[1][2] The disease often gets worse over time and can result in dementia.[2] It is unclear if the risk of suicide is altered.[1]

| Chronic traumatic encephalopathy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Traumatic encephalopathy syndrome, dementia pugilistica,[1] punch drunk syndrome |

| |

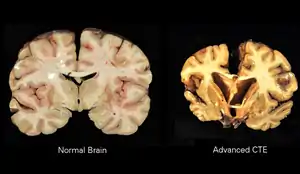

| A normal brain (left) and one with CTE (right) | |

| Specialty | Neurology, psychiatry, sports medicine |

| Symptoms | Behavioral problems, mood problems, problems with thinking[1] |

| Complications | Brain damage, dementia,[2] aggression, depression, suicide[3] |

| Usual onset | Years after initial injuries[2] |

| Causes | Repeated head injuries[1] |

| Risk factors | Contact sports, military, domestic abuse, repeated banging of the head[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Autopsy[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease[3] |

| Treatment | Supportive care[3] |

| Frequency | Uncertain[2] |

Most documented cases have occurred in athletes involved in striking-based combat sports, such as boxing, kickboxing, mixed martial arts, and Muay Thai—hence its original name dementia pugilistica (Latin for "fistfighter's dementia")—and contact sports such as American football, Australian rules football, professional wrestling, ice hockey, rugby, and association football (soccer),[1][4] in semi-contact sports such as baseball and basketball, and military combat arms occupations. Other risk factors include being in the military, prior domestic violence, and repeated banging of the head.[1] The exact amount of trauma required for the condition to occur is unknown, and as of 2022 definitive diagnosis can only occur at autopsy.[1] The disease is classified as a tauopathy.[1]

There is no specific treatment for the disease.[3] Rates of CTE have been found to be about 30% among those with a history of multiple head injuries;[1] however, population rates are unclear.[2] Research in brain damage as a result of repeated head injuries began in the 1920s, at which time the condition was known as dementia pugilistica or "fistfighter's dementia", "boxer's madness", or "punch drunk syndrome".[1][3] It has been proposed that the rules of some sports be changed as a means of prevention.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of CTE, which occur in four stages, generally appear eight to ten years after an individual experiences repetitive mild traumatic brain injuries.[5]

First-stage symptoms are confusion, disorientation, dizziness, and headaches. Second-stage symptoms include memory loss, social instability, impulsive behavior, and poor judgment. Third and fourth stages include progressive dementia, movement disorders, hypomimia, speech impediments, sensory processing disorder, tremors, vertigo, deafness, depression and suicidality.[6]

Additional symptoms include dysarthria, dysphagia, cognitive disorders such as amnesia, and ocular abnormalities, such as ptosis.[7] The condition manifests as dementia, or declining mental ability, problems with memory, dizzy spells or lack of balance to the point of not being able to walk under one's own power for a short time and/or Parkinsonism, or tremors and lack of coordination. It can also cause speech problems and an unsteady gait. Patients with CTE may be prone to inappropriate or explosive behavior and may display pathological jealousy or paranoia.[8]

Cause

Most documented cases have occurred in athletes with mild repetitive head impacts (RHI) over an extended period of time. Evidence indicates that repetitive concussive and subconcussive blows to the head cause CTE.[9] Specifically contact sports such as boxing, American football, Australian rules football, wrestling, mixed martial arts, ice hockey, rugby, and association football.[1][4] In association football (soccer), whether this is just associated with prolific headers or other injuries is unclear as of 2017.[10] Other potential risk factors include military personnel (repeated exposure to explosive charges or large caliber ordnance), domestic violence, and repeated banging of the head.[1] The exact amount of trauma required for the condition to occur is unknown although it is believed that it may take years to develop.[1]

Pathology

The neuropathological appearance of CTE is distinguished from other tauopathies, such as Alzheimer's disease. The four clinical stages of observable CTE disability have been correlated with tau pathology in brain tissue, ranging in severity from focal perivascular epicenters of neurofibrillary tangles in the frontal neocortex to severe tauopathy affecting widespread brain regions.[11]

The primary physical manifestations of CTE include a reduction in brain weight, associated with atrophy of the frontal and temporal cortices and medial temporal lobe. The lateral ventricles and the third ventricle are often enlarged, with rare instances of dilation of the fourth ventricle.[12] Other physical manifestations of CTE include anterior cavum septi pellucidi and posterior fenestrations, pallor of the substantia nigra and locus ceruleus, and atrophy of the olfactory bulbs, thalamus, mammillary bodies, brainstem and cerebellum.[13] As CTE progresses, there may be marked atrophy of the hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and amygdala.[5]

On a microscopic scale, a pathognomonic CTE lesion involves p-tau aggregates in neurons, with or without thorn-shaped astrocytes, at the depths of the cortical sulcus around a small blood vessel, deep in the parenchyma, and not restricted to the subpial and superficial region of the sulcus; the pathognomonic lesion must include p-tau in neurons to distinguish CTE from ARTAG.[14] Supporting features of CTE are: superficial neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs); p–tau in CA2 and CA4 hippocampus; p-tau in: mammillary bodies, hypothalamic nuclei, amygdala, nucleus accumbens, thalamus, midbrain tegmentum, nucleus basalis of Meynert, raphe nuclei, substantia nigra and locus coeruleus; p-tau thorn-shaped astrocytes (TSA) in the subpial region; p-tau dot-like neurites.[15] Purely astrocytic perivascular p-tau pathology represents ARTAG and does not meet the criteria for CTE.[14]

A small group of individuals with CTE have chronic traumatic encephalomyopathy (CTEM), which is characterized by symptoms of motor-neuron disease and which mimics amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Progressive muscle weakness and balance and gait problems (problems with walking) seem to be early signs of CTEM.[12]

Exosome vesicles created by the brain are potential biomarkers of TBI, including CTE.[16]

Loss of neurons, scarring of brain tissue, collection of proteinaceous senile plaques, hydrocephalus, attenuation of the corpus callosum, diffuse axonal injury, neurofibrillary tangles, and damage to the cerebellum are implicated in the syndrome. Neurofibrillary tangles have been found in the brains of dementia pugilistica patients, but not in the same distribution as is usually found in people with Alzheimer's.[17] One group examined slices of brain from patients having had multiple mild traumatic brain injuries and found changes in the cells' cytoskeletons, which they suggested might be due to damage to cerebral blood vessels.[18]

Increased exposure to concussions and subconcussive blows is regarded as the most important risk factor. This exposure can depend on the total number of fights, number of knockout losses, the duration of career, fight frequency, age of retirement, and boxing style.[19]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of CTE cannot be made in living individuals; a clear diagnosis is only possible during an autopsy.[20] Though there are signs and symptoms some researchers associate with CTE, there is no definitive test to prove the existence in a living person. Signs are also very similar to that of other neurological conditions such as Alzheimer's.[21]

The lack of distinct biomarkers is the reason CTE cannot typically be diagnosed while a person is alive. Concussions are non-structural injuries and do not result in brain bleeding, which is why most concussions cannot be seen on routine neuroimaging tests such as CT or MRI.[22] Acute concussion symptoms (those that occur shortly after an injury) should not be confused with CTE. Differentiating between prolonged post-concussion syndrome (PCS, where symptoms begin shortly after a concussion and last for weeks, months, and sometimes even years) and CTE symptoms can be difficult. Research studies are examining whether neuroimaging can detect subtle changes in axonal integrity and structural lesions that can occur in CTE.[5] Recently, more progress in in-vivo diagnostic techniques for CTE has been made, using DTI, fMRI, MRI, and MRS imaging; however, more research needs to be done before any such techniques can be validated.[12]

PET tracers that bind specifically to tau protein are desired to aid diagnosis of CTE in living individuals. One candidate is the tracer [18F]FDDNP, which is retained in the brain in individuals with a number of dementing disorders such as Alzheimer's disease, Down syndrome, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, familial frontotemporal dementia, and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease.[23] In a small study of 5 retired NFL players with cognitive and mood symptoms, the PET scans revealed accumulation of the tracer in their brains.[24] However, [18F]FDDNP binds to beta-amyloid and other proteins as well. Moreover, the sites in the brain where the tracer was retained were not consistent with the known neuropathology of CTE.[25] A more promising candidate is the tracer [18F]-T807, which binds only to tau. It is being tested in several clinical trials.[25]

A putative biomarker for CTE is the presence in serum of autoantibodies against the brain. The autoantibodies were detected in football players who experienced a large number of head hits but no concussions, suggesting that even sub-concussive episodes may be damaging to the brain. The autoantibodies may enter the brain by means of a disrupted blood-brain barrier, and attack neuronal cells which are normally protected from an immune onslaught.[26] Given the large numbers of neurons present in the brain (86 billion), and considering the poor penetration of antibodies across a normal blood-brain barrier, there is an extended period of time between the initial events (head hits) and the development of any signs or symptoms. Nevertheless, autoimmune changes in blood of players may constitute the earliest measurable event predicting CTE.[27]

According to 2017 study on brains of deceased gridiron football players, 99% of tested brains of NFL players, 88% of CFL players, 64% of semi-professional players, 91% of college football players, and 21% of high school football players had various stages of CTE. Players still alive are not able to be tested.[28]

Imaging

Although the diagnosis of CTE cannot be determined by imaging, the effects of head trauma may be seen with the use of structural imaging.[29] Imaging techniques include the use of magnetic resonance imaging, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, CT scan, single-photon emission computed tomography, Diffusion MRI, and Positron emission tomography (PET).[29] One specific use of imaging is the use of a PET scan is to evaluate for tau deposition, which has been conducted on retired NFL players.[30]

Prevention

The use of helmets and mouth-guards has been put forward as a possible preventative measure; though neither has significant research to support its use,[31] both have been shown to reduce direct head trauma.[32] Although there is no significant research to support the use of helmets to reduce the risk of concussions, there is evidence to support that helmet use reduces impact forces. Mouth guards have been shown to decrease dental injuries, but again have not shown significant evidence to reduce concussions.[29] Because repeated impacts are thought to increase the likelihood of CTE development, a growing area of practice is improved recognition and treatment for concussions and other head trauma; removal from sport participation during recovery from these traumatic injuries is essential.[29] Proper return-to-play protocol after possible brain injuries is also important in decreasing the significance of future impacts.[29]

Efforts are being made to change the rules of contact sports to reduce the frequency and severity of blows to the head.[29] Examples of these rule changes are the evolution of tackling technique rules in American football, such as the banning of helmet-first tackles, and the addition of rules to protect defenseless players. Likewise, another growing area of debate is better implementation of rules already in place to protect athletes.[29]

Because of the concern that boxing may cause CTE, there is a movement among medical professionals to ban the sport.[8] Medical professionals have called for such a ban as early as the 1950s.[7]

Management

No cure exists for CTE, and because it cannot be tested for until an autopsy is performed, people cannot know if they have it.[33] Treatment is supportive as with other forms of dementia.[34] Those with CTE-related symptoms may receive medication and non-medication related treatments.[35]

Epidemiology

Rates of disease have been found to be about 30% among those with a history of multiple head injuries.[1] Population rates, however, are unclear.[2]

Professional level athletes are the largest group with CTE, due to frequent concussions and sub-concussive impacts from play in contact sport.[36] These contact-sports include American football, Australian rules football,[37] ice hockey, Rugby football (Rugby union and Rugby league),[38] boxing, kickboxing, mixed martial arts, association football,[39][38] and wrestling.[40] In association football, only prolific headers are known to have developed CTE.[39]

Cases of CTE were also recorded in baseball.[41]

According to a 2017 study on brains of deceased gridiron football players, 99% of tested brains of NFL players, 88% of CFL players, 64% of semi-professional players, 91% of college football players, and 21% of high school football players had various stages of CTE.[28]

Other individuals diagnosed with CTE were those involved in military service, had a previous history of chronic seizures, were domestically abused, or were involved in activities resulting in repetitive head collisions.[42][29][43]

History

CTE was originally studied in boxers in the 1920s as "punch-drunk syndrome." Punch-drunk syndrome was first described in 1928 by a forensic pathologist, Dr. Harrison Stanford Martland, who was the chief medical examiner of Essex County in Newark, New Jersey, in a Journal of the American Medical Association article, in which he noted the tremors, slowed movement, confusion and speech problems typical of the condition.[44] The term "punch-drunk" was replaced with "dementia pugilistica" in 1937 by J.A. Millsbaugh, as he felt the term was condescending to former boxers.[45] The initial diagnosis of dementia pugilistica was derived from the Latin word for boxer pugil (akin to pugnus 'fist', pugnāre 'to fight').[46][47]

Other terms for the condition have included chronic boxer's encephalopathy, traumatic boxer's encephalopathy, boxer's dementia, pugilistic dementia, chronic traumatic brain injury associated with boxing (CTBI-B), and punch-drunk syndrome.[3]

The seminal work on the disease came from British neurologist Macdonald Critchley, who in 1949 wrote a paper titled "Punch-drunk syndromes: the chronic traumatic encephalopathy of boxers".[48] CTE was first recognized as affecting individuals who took considerable blows to the head, but was believed to be confined to boxers and not other athletes. As evidence pertaining to the clinical and neuropathological consequences of repeated mild head trauma grew, it became clear that this pattern of neurodegeneration was not restricted to boxers, and the term chronic traumatic encephalopathy became most widely used.[49][50]

In 1990, a patient nicknamed Wilma was diagnosed postmortem with dementia pugilistica; she was the first woman diagnosed with dementia pugilistica from domestic violence.[51]

In 2002, American football player Mike Webster died following unusual and unexplained behavior. In 2005 Nigerian-American neuropathologist Bennet Omalu, along with colleagues in the Department of Pathology at the University of Pittsburgh, published their findings in a paper titled "Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in a National Football League Player", followed by a paper on a second case in 2006 describing similar pathology.

In June 2007 professional wrestler Chris Benoit murdered his wife and son before committing suicide days after appearing on television. His autopsy revealed he was in very advanced stages of CTE with his brain being said to resemble that of an 87-year-old with advanced Alzheimer's.

In 2008, the Sports Legacy Institute joined with the Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) to form the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy (now the BU CTE Center).[52] Brain Injury Research Institute (BIRI) also studies the impact of concussions.[53][54]

In 2014, Patrick Grange of Albuquerque was the first US soccer player with CTE at autopsy. He was well known for his heading and had died in 2012.[55]

On April 7, 2021, former National Football League player Phillip Adams was found to have shot and killed six people, before killing himself a day later.[56] A subsequent autopsy revealed at that the time of the shooting, Adams had an "unusually severe" case of chronic traumatic encephalopathy.[57]

In October 2022. the United States National Institutes of Health formally acknowledged there was a causal link between repeated blows to the head and CTE.[58]

Research

In 2005, forensic pathologist Bennet Omalu, along with colleagues in the Department of Pathology at the University of Pittsburgh, published a paper, "Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in a National Football League Player", in the journal Neurosurgery, based on analysis of the brain of deceased former NFL center Mike Webster. This was then followed by a paper on a second case in 2006 describing similar pathology, based on findings in the brain of former NFL player Terry Long.

In 2008, the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy at the BU School of Medicine (now the BU CTE Center) started the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank at the Bedford Veterans Administration Hospital to analyze the effects of CTE and other neurodegenerative diseases on the brain and spinal cord of athletes, military veterans, and civilians.[11][59] To date, the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank is the largest CTE tissue repository in the world, with over 1000 brain donors.[12][60]

On 21 December 2009, the National Football League Players Association announced that it would collaborate with the BU CTE Center to support the center's study of repetitive brain trauma in athletes.[61] Additionally, in 2010 the National Football League gave the BU CTE Center a $1 million gift with no strings attached.[62][63] In 2008, twelve living athletes (active and retired), including hockey players Pat LaFontaine and Noah Welch as well as former NFL star Ted Johnson, committed to donate their brains to VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank after their deaths.[52][64] In 2009, NFL Pro Bowlers Matt Birk, Lofa Tatupu, and Sean Morey pledged to donate their brains to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank.[65]

In 2010, 20 more NFL players and former players pledged to join the VA-BU-CLF Brain Donation Registry, including Chicago Bears linebacker Hunter Hillenmeyer, Hall of Famer Mike Haynes, Pro Bowlers Zach Thomas, Kyle Turley, and Conrad Dobler, Super Bowl Champion Don Hasselbeck and former pro players Lew Carpenter, and Todd Hendricks. In 2010, professional wrestlers Mick Foley, Booker T and Matt Morgan also agreed to donate their brains upon their deaths. Also in 2010, MLS player Taylor Twellman, who had to retire from the New England Revolution because of post-concussion symptoms, agreed to donate his brain upon his death. As of 2010, the VA-BU-CLF Brain Donation Registry consists of over 250 current and former athletes.[66]

In 2011, former North Queensland Cowboys player Shaun Valentine became the first Australian National Rugby League player to agree to donate his brain upon his death, in response to recent concerns about the effects of concussions on Rugby League players, who do not use helmets. Also in 2011, boxer Micky Ward, whose career inspired the film The Fighter, agreed to donate his brain upon his death. In 2018, NASCAR driver Dale Earnhardt Jr., who retired in 2017 citing multiple concussions, became the first auto racing competitor agreeing to donate his brain upon his death.[67]

In related research, the Center for the Study of Retired Athletes, which is part of the Department of Exercise and Sport Science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is conducting research funded by National Football League Charities to "study former football players, a population with a high prevalence of exposure to prior Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (MTBI) and sub-concussive impacts, in order to investigate the association between increased football exposure and recurrent MTBI and neurodegenerative disorders such as cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease (AD)".[68]

In February 2011, former NFL player Dave Duerson committed suicide via a gunshot to his chest, thus leaving his brain intact.[69] Duerson left text messages to loved ones asking that his brain be donated to research for CTE.[70] The family got in touch with representatives of the Boston University center studying the condition, said Robert Stern, the co-director of the research group. Stern said Duerson's gift was the first time of which he was aware that such a request had been made by someone who had committed suicide that was potentially linked to CTE.[71] Stern and his colleagues found high levels of the protein tau in Duerson's brain. These elevated levels, which were abnormally clumped and pooled along the brain sulci,[11] are indicative of CTE.[72]

In July 2010, NHL enforcer Bob Probert died of heart failure. Before his death, he asked his wife to donate his brain to CTE research because it was noticed that Probert experienced a mental decline in his 40s. In March 2011, researchers at Boston University concluded that Probert had CTE upon analysis of the brain tissue he donated. He was the second NHL player from the program at the BU CTE Center to be diagnosed with CTE postmortem.[73]

The BU CTE Center has also found indications of links between amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and CTE in athletes who have participated in contact sports. Tissue for the study was donated by twelve athletes and their families to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank at the Bedford, Massachusetts VA Medical Center.[74]

In 2013, President Barack Obama announced the creation of the Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium or CENC, a federally funded research project devised to address the long-term effects of mild traumatic brain injury in military service personnel (SM's) and veterans.[75][76][77] The CENC is a multi-center collaboration linking premiere basic science, translational, and clinical neuroscience researchers from the DoD, VA, academic universities, and private research institutes to effectively address the scientific, diagnostic, and therapeutic ramifications of mild TBI and its long-term effects.[78][79][80][81][82]

Nearly 20% of the more than 2.5 million U.S. service members (SMs) deployed since 2003 to Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) have sustained at least one traumatic brain injury (TBI), predominantly mild TBI (mTBI),[83][84] and almost 8% of all OEF/OIF Veterans demonstrate persistent post-TBI symptoms more than six months post-injury.[85][86] Unlike those head injuries incurred in most sporting events, recent military head injuries are most often the result of blast wave exposure.[87] After a competitive application process, a consortium led by Virginia Commonwealth University was awarded funding.[78][79][80][81][88][89]

The project principal investigator for the CENC is David Cifu, chairman and Herman J. Flax professor[90] of the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (PM&R) at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) in Richmond, Virginia, with co-principal investigators Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, Professor of Neurology, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences,[81] and Rick L. Williams, statistician at RTI International.

In 2017, Aaron Hernandez, a former professional football player and convicted murderer, committed suicide at the age of 27 while in prison. His family donated his brain to the BU CTE Center. Ann McKee, the head of Center, concluded that "Hernandez had Stage 3 CTE, which researchers had never seen in a brain younger than 46 years old."[91]

See also

- Acquired brain injury

- Brain damage

- Concussions in American football

- Concussions in rugby union

- Brendan Schaub

- Health issues in American football

- List of NFL players with chronic traumatic encephalopathy

- The Hit (Chuck Bednarik)

- Traumatic brain injury

References

- Asken, BM; Sullan, MJ; DeKosky, ST; Jaffee, MS; Bauer, RM (1 October 2017). "Research Gaps and Controversies in Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: A Review". JAMA Neurology. 74 (10): 1255–62. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.2396. PMID 28975240. S2CID 24317634.

- Stein, TD; Alvarez, VE; McKee, AC (2014). "Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: a spectrum of neuropathological changes following repetitive brain trauma in athletes and military personnel". Alzheimer's Research & Therapy. 6 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/alzrt234. PMC 3979082. PMID 24423082.

- "Alzheimer's & Dementia". Alzheimer's Association. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- Maroon, Joseph C; Winkelman, Robert; Bost, Jeffrey; Amos, Austin C; Mathyssek, Christina; Miele, Vincent (2015). "Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Contact Sports: A Systematic Review of All Reported Pathological Cases". PLOS One. 10 (2): e0117338. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1017338M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0117338. PMC 4324991. PMID 25671598.

- McKee AC, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ, Hedley-Whyte ET, Gavett BE, Budson AE, Santini VE, Lee HS, Kubilus CA, Stern RA (2009). "Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury". J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 68 (7): 709–35. doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a9d503. PMC 2945234. PMID 19535999.

- Arman Fesharaki-Zadeh (2019). "Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: A Brief Overview". Frontiers in Neurology. 10: 713. doi:10.3389/fneur.2019.00713. PMC 6616127. PMID 31333567.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Corsellis; et al. (1973). "The Aftermath of Boxing". Psychological Medicine. 3 (3): 270–303. doi:10.1017/S0033291700049588. PMID 4729191. S2CID 41879040.

- Mendez MF (1995). "The neuropsychiatric aspects of boxing". International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 25 (3): 249–62. doi:10.2190/CUMK-THT1-X98M-WB4C. PMID 8567192. S2CID 20238578.

-

- Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: A paradigm in search of evidence? Rudy J Castellani

- New insights into the long-term effects of mild brain injury Charlotte Ridler Nature Reviews Neurology volume 13, page195 (2017)

- Concussion, microvascular injury, and early tauopathy in young athletes after impact head injury and an impact concussion mouse model - Brain, Volume 141, Issue 2, February 2018

- Clinical subtypes of chronic traumatic encephalopathy: literature review and proposed research diagnostic criteria for traumatic encephalopathy syndrome - Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014; 6(5): 68. Published online 2014 Sep 24.

- Effects of Subconcussive Head Trauma on the Default Mode Network of the Brain - J Neurotrauma. 2014 Dec 1; 31(23): 1907–1913.

- Understanding the Consequences of Repetitive Subconcussive Head Impacts in Sport: Brain Changes and Dampened Motor Control Are Seen After Boxing Practice - ORIGINAL RESEARCH article Front. Hum. Neurosci., 10 September 2019

- Nitrini, R (2017). "Soccer (Football Association) and chronic traumatic encephalopathy: A short review and recommendation". Dementia & Neuropsychologia. 11 (3): 218–20. doi:10.1590/1980-57642016dn11-030002. PMC 5674664. PMID 29213517.

- McKee AC, Stern RA, Nowinski CJ, Stein TD, Alvarez VE, Daneshvar DH, Lee HS, Wojtowicz SM, Hall G, Baugh CM, Riley DO, Kubilus CA, Cormier KA, Jacobs MA, Martin BR, Abraham CR, Ikezu T, Reichard RR, Wolozin BL, Budson AE, Goldstein LE, Kowall NW, Cantu RC (2013). "The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy". Brain. 136 (Pt 1): 43–64. doi:10.1093/brain/aws307. PMC 3624697. PMID 23208308.

- Baugh CM, Stamm JM, Riley DO, Gavett BE, Shenton ME, Lin A, Nowinski CJ, Cantu RC, McKee AC, Stern RA (2012). "Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: neurodegeneration following repetitive concussive and subconcussive brain trauma". Brain Imaging Behavior. 6 (2): 244–54. doi:10.1007/s11682-012-9164-5. PMID 22552850. S2CID 15955018.

- Jancin, Bruce (1 June 2011). "Chronic traumatic encephalopathy test sought". Internal Medicine News. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- Bienek, Kevin F.; al, et (21 February 2021). "The Second NINDS/NIBIB Consensus Meeting to Define Neuropathological Criteria for the Diagnosis of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy". Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 80 (3): 210–219. doi:10.1093/jnen/nlab001. PMC 7899277. PMID 33611507.

- McKee, Ann C.; al, et (January 2016). "The first NINDS/NIBIB consensus meeting to define neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy". Acta Neuropathologica. 131 (1): 75–86. doi:10.1007/s00401-015-1515-z. PMC 4698281. PMID 26667418.

- Taylor DD, Gercel-Taylor C (2014). "Exosome platform for diagnosis and monitoring of traumatic brain injury". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 369 (1652): 20130503. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0503. PMC 4142024. PMID 25135964.

- Hof PR, Bouras C, Buée L, Delacourte A, Perl DP, Morrison JH (1992). "Differential Distribution of Neurofibrillary Tangles in the Cerebral Cortex of Dementia Pugilistica and Alzheimer's Disease Cases". Acta Neuropathologica. 85 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1007/BF00304630. PMID 1285493. S2CID 11624928.

- Geddes JF, Vowles GH, Nicoll JA, Révész T (1999). "Neuronal Cytoskeletal Changes are an Early Consequence of Repetitive Head Injury". Acta Neuropathologica. 98 (2): 171–78. doi:10.1007/s004010051066. PMID 10442557. S2CID 24694052.

- Jordan, B. D. (2009). "Brain injury in boxing". Clinics in Sports Medicine, 28(4), 561–78, vi.

- Concannon, Leah (2014). "Counseling Athletes on the Risk on Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy". Sports Health. 6 (5): 396–401. doi:10.1177/1941738114530958. PMC 4137675. PMID 25177414.

- Turner, Ryan C., et al. "Alzheimer's disease and chronic traumatic encephalopathy: Distinct but possibly overlapping disease entities", Brain Injury, August 11, 2016. Accessed December 28, 2021. "Alzheimer's disease (AD) and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) have long been recognized as sharing some similar neuropathological features, mainly the presence of neurofibrilary tangles and hyperphosphorylated tau, but have generally been described as distinct entities. Evidence indicates that neurotrauma increases the risk of developing dementia and accelerates the progression of disease. Findings are emerging that CTE and AD may be present in the same patients."

- Poirier MP (2003). "Concussions: Assessment, management, and recommendations for return to activity". Clinical Pediatric Emergency Medicine. 4 (3): 179–85. doi:10.1016/S1522-8401(03)00061-2.

- Villemagne VL, Fodero-Tavoletti MT, Masters CL, Rowe CC (2015). "Tau imaging: early progress and future directions". The Lancet. Neurology. 14 (1): 114–24. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70252-2. PMID 25496902. S2CID 10502833.

- Small GW, Kepe V, Siddarth P, Ercoli LM, Merrill DA, Donoghue N, Bookheimer SY, Martinez J, Omalu B, Bailes J, Barrio JR (2013). "PET scanning of brain tau in retired national football league players: preliminary findings". Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 21 (2): 138–44. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.372.2960. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2012.11.019. PMID 23343487.

- Montenigro PH, Corp DT, Stein TD, Cantu RC, Stern RA (2015). "Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: historical origins and current perspective". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 11: 309–30. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112814. PMID 25581233.

- John Mangels, Cleveland Plain Dealer, 2013/03.

- Marchi N, Bazarian JJ, Puvenna V, Janigro M, Ghosh C, Zhong J, Zhu T, Blackman E, Stewart D, Ellis J, Butler R, Janigro D (2013). "Consequences of repeated blood-brain barrier disruption in football players". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e56805. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...856805M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056805. PMC 3590196. PMID 23483891.

- "BU Researchers Find CTE in 99% of Former NFL Players Studied". Boston University.

- Concannon, Leah (October 2014). "Counseling Athletes on the Risk of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy". Sports Health. 6 (5): 396–401. doi:10.1177/1941738114530958. PMC 4137675. PMID 25177414.

- Stern, Robert A.; Adler, Charles H.; Chen, Kewei; Navitsky, Michael; Luo, Ji; Dodick, David W.; Alosco, Michael L.; Tripodis, Yorghos; Goradia, Dhruman D.; Martin, Brett; Mastroeni, Diego; Fritts, Nathan G.; Jarnagin, Johnny; Devous, Michael D.; Mintun, Mark A.; Pontecorvo, Michael J.; Shenton, Martha E.; Reiman, Eric M. (2019). "Tau Positron-Emission Tomography in Former National Football League Players". New England Journal of Medicine. 380 (18): 1716–25. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1900757. ISSN 0028-4793. PMC 6636818. PMID 30969506.

- Sone, Je Yeong; Kondziolka, Douglas; Huang, Jason H.; Samadani, Uzma (1 March 2017). "Helmet efficacy against concussion and traumatic brain injury: a review". Journal of Neurosurgery. 126 (3): 768–81. doi:10.3171/2016.2.JNS151972. ISSN 1933-0693. PMID 27231972.

- Saffary, Roya (2012). "From Concussion to Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: A Review". Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology: 315–62.

- "Alzheimer's & Dementia". Alzheimer's Association. alz.org. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- "Treating CTE". NHS Choices. GOV.UK. 1 October 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- Cantu, Robert; Budson, Andrew (October 2019). "Management of chronic traumatic encephalopathy". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 19 (10): 1015–23. doi:10.1080/14737175.2019.1633916. PMID 31215252. S2CID 195064872.

- Saulle M, Greenwald BD (2012). "Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: a review" (PDF). Rehabil Res Pract. 2012: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2012/816069. PMC 3337491. PMID 22567320.

- "CTE discovered in Polly Farmer's brain in AFL-first". 26 February 2020.

- Stone, Paul (18 March 2014). "First Soccer and Rugby Players Diagnosed With CTE". Neurologic Rehabilitation Institute at Brookhaven Hospital. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- Ling, Helen; Morris, Huw R.; Neal, James W.; Lees, Andrew J.; Hardy, John; Holton, Janice L.; Revesz, Tamas; Williams, David D.R. (March 2017). "Mixed pathologies including chronic traumatic encephalopathy account for dementia in retired association football (soccer) players". Acta Neuropathologica. 133 (3): 337–52. doi:10.1007/s00401-017-1680-3. PMC 5325836. PMID 28205009.

- Daneshvar DH, Nowinski CJ, McKee AC, Cantu RC (2011). "The epidemiology of sport-related concussion". Clin Sports Med. 30 (1): 1–17, vii. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2010.08.006. PMC 2987636. PMID 21074078.

- "Baseball's New Three-Letter Word: CTE". The Good Men Project. 2 November 2018.

- Daneshvar DH, Riley DO, Nowinski CJ, McKee AC, Stern RA, Cantu RC (2011). "Long-term consequences: effects on normal development profile after concussion". Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 22 (4): 683–700, ix. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2011.08.009. PMC 3208826. PMID 22050943.

- Shetty, Teena (2016). "Imaging in Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy and Traumatic Brain Injury". Sports Health. 8 (1): 26–36. doi:10.1177/1941738115588745. PMC 4702153. PMID 26733590.

- Martland HS (1928). "Punch Drunk". Journal of the American Medical Association. 91 (15): 1103–07. doi:10.1001/jama.1928.02700150029009.

- Castellani, Rudy J.; Perry, George (7 November 2017). "Dementia Pugilistica Revisited". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 60 (4): 1209–21. doi:10.3233/JAD-170669. PMC 5676846. PMID 29036831.

- Pugilism (origin), retrieved on 2 February 2013.

- NCERx. 2005. Brain Trauma, Subdural Hematoma and Dementia Pugilistica Archived 27 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine. About – dementia.com. Retrieved on 19 December 2007.

- "'Concussion' Subject Bennet Omalu Exaggerated His Role, Researchers Say". CBS New York. 17 December 2015.

- Martland H (1928). "Punch Drunk". The Journal of the American Medical Association. 91 (15): 1103–07. doi:10.1001/jama.1928.02700150029009.

- Gavett BE, Stern RA, McKee AC (2011). "Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: a potential late effect of sport-related concussive and subconcussive head trauma". Clin Sports Med. 30 (1): 179–88, xi. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2010.09.007. PMC 2995699. PMID 21074091.

- Roberts, G. W; Whitwell, H. L; Acland, P. R; Bruton, C. J (14 April 1990). "Dementia in a punch-drunk wife". Letters to the Editor. 335 (8694): 918–19. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(90)90520-f. PMID 1970008. S2CID 33534406.

- "New pathology findings show significant brain degeneration in professional athletes with history of repetitive concussions", Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy, 25 September 2008.

- "Seau family revisiting brain decision". ESPN. 6 May 2012. Archived from the original on 7 May 2012.

- "Our Team". Brain Injury Research Institute. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011.

- Branch, John (26 February 2014). "Brain Trauma Extends to the Soccer Field". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- "Ex-NFL player named as gunman who killed renowned doctor and grandchildren". The Independent. 8 April 2021.

- Kaplan, Anna. "Ex-NFL Player Phillip Adams—Who Killed 6 During Rampage—Had Severe CTE Similar To Aaron Hernandez, Doctor Says". Forbes.

- "US health body rules collision sports cause CTE in landmark change". the Guardian. 24 October 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- "VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank | CTE Center". www.bu.edu. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- "1000 Reasons | Concussion Legacy Foundation". concussionfoundation.org. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- Staff. "NFL Players Association to Support Brain Trauma Research at Boston University", Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy press release dated 21 December 2009. Accessed 17 August 2010.

- Support and Funding Archived 15 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy. Accessed 17 August 2010.

- Schwarz, Alan. "N.F.L. Donates $1 Million for Brain Studies", The New York Times, 20 April 2010. Accessed 17 August 2010.

- "Welch to donate brain for concussion study". Edmonton Journal. Archived from the original on 6 October 2010. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Staff. "Three active NFL Pro Bowl players to donate brains to research", Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy press release dated 14 September 2009. Accessed 17 August 2010.

- Staff. "20 more NFL stars to donate brains to research", Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy press release dated 1 February 2010. Accessed 17 August 2010.

- Boren, Cindy. "Dale Earnhardt Jr. plans to donate his brain for concussion research", The Washington Post, March 28, 2016. Accessed December 28, 2021. "He made the announcement in the most Dale Earnhardt Jr. way possible, with a nonchalant tweet on a Saturday night. That's how NASCAR's most popular driver disclosed that he would donate his brain posthumously to science. His announcement came in response to a Sports Illustrated tweet and responses about three members of the Oakland Raiders deciding to donate their brains to the Concussion Legacy Foundation after learning that Hall of Famer Ken Stabler's brain showed evidence of chronic traumatic encephalopathy at autopsy."

- "A Study on the Association Between Football Exposure and Dementia in Retired Football Players". UNC College of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 11 August 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- Smith, Michael David, "Boston researchers request Junior Seau's brain". NBC Sports Pro Football Talk, 3 May 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- Kusinski, Peggy (1 February 2011). "Dave Duerson Committed Suicide: Medical Examiner". NBC Chicago. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- Schwarz, Alan (20 February 2011). "Before Suicide, Duerson Asked for Brain Study". The New York Times.

- Deardorff, Julie (2 May 2011). "Study: Duerson had brain damage at time of suicide". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- Schwarz, Alan (2 March 2011). "Hockey Brawler Paid Price, With Brain Trauma". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- "Researchers Discover Brain Trauma in Sports May Cause a New Disease That Mimics ALS", BUSM press release, 17 August 2010 3:41 pm. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- Jordan, Bryant (12 August 2013). "Obama Introduces New PTSD and Education Programs". military.com. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- "Obama administration to research TBI, PTSD in new efforts Read more: Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium". fiercegovernment.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- "DoD, VA Establish Two Multi-Institutional Consortia to Research PTSD and TBI". va.gov. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- "Fact Sheet: Largest federal grant in VCU's history". spectrum.vcu.edu. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- "VCU to lead major study of concussions". grpva.com. Archived from the original on 3 May 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- "Brain trust – the US consortia tacking military PTSD and brain injury". army-technology.com. 9 March 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- "DOD partners to combat brain injury". army.mil. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- "RTI to research mild traumatic brain injury effects in US soldiers". army-technology.com. 2 August 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- Warden D. Military TBI during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006; 21 (5): 398–402.

- "DoD Worldwide Numbers for TBI". dvbic.dcoe.mil. Archived from the original on 17 January 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- Scholten JD, Sayer NA, Vanderploeg RD, Bidelspach DE, Cifu DX (2012). "Analysis of US Veterans Health Administration comprehensive evaluations for traumatic brain injury in Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom Veterans". Brain Inj. 26 (10): 1177–84. doi:10.3109/02699052.2012.661914. PMID 22646489. S2CID 37365962.

- Taylor BC, Hagel EM, Carlson KF, Cifu DX, Cutting A, Bidelspach DE, Sayer NA (2012). "Prevalence and costs of co-occurring traumatic brain injury with and without psychiatric disturbance and pain among Afghanistan and Iraq War Veteran V.A. users". Med Care. 50 (4): 342–46. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e318245a558. PMID 22228249. S2CID 29920171.

- Weppner J, Linsenmeyer M, Ide W (1 August 2019). "Military Blast-Related Traumatic Brain Injury". Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports. Brain Injury Medicine and Rehabilitation. 7 (4): 323–32. doi:10.1007/s40141-019-00241-8. S2CID 199407324. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "Fact Sheet: The Obama Administration's Work to Honor Our Military Families and Veterans". whitehouse.gov. 1 August 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2014 – via National Archives.

- "Fact Sheet: VCU will lead $62 million study of traumatic brain injuries in military personnel". news.vcu.edu. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- About Us Archived 22 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Virginia Commonwealth University. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- Kilgore, Adam (9 November 2017). "Aaron Hernandez suffered from most severe CTE ever found in a person his age". Washington Post. Retrieved 12 July 2020.