Bristol

Bristol (/ˈbrɪstəl/ (![]() listen)) is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England.[7] Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in South West England.[8]

The wider Bristol Built-up Area is the eleventh most populous urban area in the United Kingdom.[5]

listen)) is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England.[7] Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in South West England.[8]

The wider Bristol Built-up Area is the eleventh most populous urban area in the United Kingdom.[5]

Bristol | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: Bristol skyline, Wills Memorial Building, Bristol Cathedral, Bristol Museum & Art Gallery, Victoria Rooms, the City Hall and Clifton Suspension Bridge | |

Coat of arms | |

| Motto(s): Virtute et industria (With courage and industry) | |

Bristol Location within the United Kingdom  Bristol Location of city centre within county  Bristol Location within England  Bristol Location in Europe | |

| Coordinates: 51°27′N 2°35′W | |

| Sovereign state | |

| Country | |

| Region | South West |

| Royal charter | 1155[1] |

| County corporate | 1373 |

| City status by diocese creation | 1542 |

| Ceremonial county | 1996 |

| Status | City, county and unitary authority |

| Government | |

| • Type | Unitary authority |

| • Governing body | Bristol City Council |

| • Admin HQ | City Hall, College Green |

| • Executive | Labour |

| • Mayor | Marvin Rees (L) |

| • MPs | Thangam Debbonaire (L) Kerry McCarthy (L) Darren Jones (L) Karin Smyth (L) |

| Area | |

| • City and county | 110 km2 (40 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 11 m (36 ft) |

| Population (2020)[5] | |

| • City and county | 465,866 (Ranked 10th district and 43rd ceremonial county) |

| • Density | 4,248/km2 (11,000/sq mi) |

| • Ethnicity[6] |

|

| Demonym | Bristolian |

| Time zone | GMT (UTC) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| Postcode | BS |

| Area codes | 0117, 01275 |

| ISO 3166 code | GB-BST |

| GVA | 2017 |

| • Total | £21.2bn ($26.9bn) (4th) |

| • Growth | |

| • Per capita | £33,700 ($42,800) (4th) |

| • Growth | |

| Website | bristol.gov.uk |

| |

| Click the map for an interactive fullscreen view | |

Iron Age hillforts and Roman villas were built near the confluence of the rivers Frome and Avon. Around the beginning of the 11th century, the settlement was known as Brycgstow (Old English: 'the place at the bridge'). Bristol received a royal charter in 1155 and was historically divided between Gloucestershire and Somerset until 1373 when it became a county corporate. From the 13th to the 18th century, Bristol was among the top three English cities, after London, in tax receipts.

A major port, Bristol was a starting place for early voyages of exploration to the New World. On a ship out of Bristol in 1497, John Cabot, a Venetian, became the first European to land on mainland North America. In 1499, William Weston, a Bristol merchant, was the first Englishman to lead an exploration to North America. At the height of the Bristol slave trade, from 1700 to 1807, more than 2,000 slave ships carried an estimated 500,000 people from Africa to slavery in the Americas. The Port of Bristol has since moved from Bristol Harbour in the city centre to the Severn Estuary at Avonmouth and Royal Portbury Dock.

Bristol's modern economy is built on the creative media, electronics and aerospace industries; the city-centre docks have been redeveloped as centres of heritage and culture. The city has the largest circulating community currency in the UK, the Bristol Pound, which is pegged to the pound sterling. The city has two universities: the University of Bristol and the University of the West of England. There are a variety of artistic and sporting organisations and venues including the Royal West of England Academy, the Arnolfini, Spike Island, Ashton Gate and the Memorial Stadium. It is connected to London and other major UK cities by road and rail, and to the world by sea and air: road, by the M5 and M4 (which connect to the city centre by the Portway and M32); rail, via Bristol Temple Meads and Bristol Parkway mainline rail stations; and Bristol Airport.

Bristol was named the best city in Britain in which to live in 2014 and 2017; it won the European Green Capital Award in 2015.

Etymology

Early recorded place names in the Bristol area include the Roman-era British Celtic Abona (derived from the name of the Avon) and the archaic Welsh Caer Odor ('fort on the chasm'), which may have been calqued as the modern English Clifton.[9][10]

The current name "Bristol" derives from the Old English form Brycgstow, which is typically etymologised as 'place at the bridge'.[11] It has also been suggested that Brycgstow means "the place called Bridge by the place called Stow", the Stow in question referring to an early religious meeting place at what is now College Green.[12] However, other derivations have been proposed.[13] It appears that the form Bricstow prevailed until 1204,[14] and the Bristolian 'L' (the tendency for the local dialect to add the sound "L" to many words ending in a neutral vowel) is what eventually changed the name to Bristol.[15] The original form of the name survives as the surname Bristow, which is derived from the city.[16]

History

Archaeological finds, including flint tools believed to be between 300,000 and 126,000 years old made with the Levallois technique, indicate the presence of Neanderthals in the Shirehampton and St Annes areas of Bristol during the Middle Palaeolithic.[17] Iron Age hill forts near the city are at Leigh Woods and Clifton Down, on the side of the Avon Gorge, and on Kings Weston Hill near Henbury.[18] A Roman settlement, Abona,[19] existed at what is now Sea Mills (connected to Bath by a Roman road); another was at the present-day Inns Court. Isolated Roman villas and small forts and settlements were also scattered throughout the area.[20]

Middle Ages

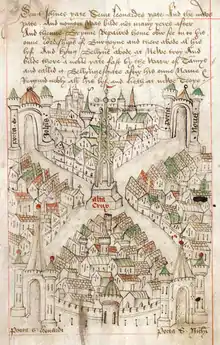

Bristol was founded by 1000; by about 1020, it was a trading centre with a mint producing silver pennies bearing its name.[21] By 1067, Brycgstow was a well-fortified burh, and that year the townsmen beat back a raiding party from Ireland led by three of Harold Godwinson's sons.[21] Under Norman rule, the town had one of the strongest castles in southern England.[22] Bristol was the place of exile for Diarmait Mac Murchada, the Irish king of Leinster, after being overthrown. The Bristol merchants subsequently played a prominent role in funding Richard Strongbow de Clare and the Norman invasion of Ireland.[23]

The port developed in the 11th century around the confluence of the Rivers Frome and Avon, adjacent to Bristol Bridge just outside the town walls.[25] By the 12th century, there was an important Jewish community in Bristol which survived through to the late 13th century when all Jews were expelled from England.[26] The stone bridge built in 1247 was replaced by the current bridge during the 1760s.[27] The town incorporated neighbouring suburbs and became a county in 1373,[28] the first town in England to be given this status.[29][30][31] During this period, Bristol became a shipbuilding and manufacturing centre.[32] By the 14th century, Bristol, York and Norwich were England's largest medieval towns after London.[33] One-third to one-half of the population died in the Black Death of 1348–49,[34] which checked population growth, and its population remained between 10,000 and 12,000 for most of the 15th and 16th centuries.[35]

15th and 16th centuries

During the 15th century, Bristol was the second most important port in the country, trading with Ireland,[36] Iceland[37] and Gascony.[32] It was the starting point for many voyages, including Robert Sturmy's (1457–58) unsuccessful attempt to break the Italian monopoly of Eastern Mediterranean trade.[38] New exploration voyages were launched by Venetian John Cabot, who in 1497 made landfall in North America.[39] A 1499 voyage, led by merchant William Weston of Bristol, was the first expedition commanded by an Englishman to North America.[40] During the first decade of the 16th century Bristol's merchants undertook a series of exploration voyages to North America and even founded a commercial organisation, 'The Company Adventurers to the New Found Land', to assist their endeavours.[41] However, they seem to have lost interest in North America after 1509, having incurred great expenses and made little profit.

During the 16th century, Bristol merchants concentrated on developing trade with Spain and its American colonies.[42] This included the smuggling of prohibited goods, such as food and guns, to Iberia[43] during the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604).[44] Bristol's illicit trade grew enormously after 1558, becoming integral to its economy.[45]

The original Diocese of Bristol was founded in 1542,[46] when the former Abbey of St. Augustine (founded by Robert Fitzharding four hundred years earlier)[47] became Bristol Cathedral. Bristol also gained city status that year.[48] During the English Civil War in the 1640s the city was occupied by Royalists, who built the Royal Fort House on the site of an earlier Parliamentarian stronghold.[49]

17th and 18th centuries

Fishermen from Bristol, who had fished the Grand Banks of Newfoundland since the 16th century,[50] began settling Newfoundland permanently in larger numbers during the 17th century, establishing colonies at Bristol's Hope and Cuper's Cove. Growth of the city and trade came with the rise of England's American colonies in the 17th century. Bristol's location on the west side of Great Britain gave its ships an advantage in sailing to and from the New World, and the city's merchants made the most of it, with the city becoming one of the two leading outports in all of England by the middle of the 18th century.[51] Bristol was the slave capital of England: In 1755, it had the largest number of slave traders in the country with 237, as against London's 147.[52] It was a major supplier of slaves to South Carolina before 1750.[53]

The 18th century saw an expansion of Bristol's population (45,000 in 1750)[54] and its role in the Atlantic trade in Africans taken for slavery to the Americas. Bristol and later Liverpool became centres of the Triangular Trade.[55] Manufactured goods were shipped to West Africa and exchanged for Africans; the enslaved captives were transported across the Atlantic to the Americas in the Middle Passage under brutal conditions.[56] Plantation goods such as sugar, tobacco, rum, rice, cotton and a few slaves (sold to the aristocracy as house servants) returned across the Atlantic to England.[56] Some household slaves were baptised in the hope this would lead them to be freed. The Somersett Case of 1772 clarified that slavery was illegal in England.[57] At the height of the Bristol slave trade from 1700 to 1807, more than 2,000 slave ships carried a conservatively estimated 500,000 people from Africa to slavery in the Americas.[58]

In 1739, John Wesley founded the first Methodist chapel, the New Room, in Bristol.[59] Wesley, along with his brother Charles Wesley and George Whitefield, preached to large congregations in Bristol and the neighbouring village of Kingswood, often in the open air.[60][61]

Wesley published a pamphlet on slavery, titled Thoughts Upon Slavery, in 1774[62] and the Society of Friends began lobbying against slavery in Bristol in 1783. The city's scions remained nonetheless strongly anti-abolitionist. Thomas Clarkson came to Bristol to study the slave trade and gained access to the Society of Merchant Venturers records.[63] One of his contacts was the owner of the Seven Stars public house, who boarded sailors Clarkson sought to meet. Through these sailors he was able to observe how slaver captains and first mates "plied and stupefied seamen with drink" to sign them up.[63][64] Other informants included ship surgeons and seamen seeking redress. When William Wilberforce began his parliamentary abolition campaign on 12 May 1788, he recalled the history of the Irish slave trade from Bristol, which he provocatively claimed continued into the reign of Henry VII.[63] Hannah More, originally from Bristol, and a good friend of both Wilberforce and Clarkson, published "Slavery, A Poem" in 1788, just as Wilberforce began his parliamentary campaign.[65] His major speech on 2 April 1792 likewise described the Bristol slave trade specifically, and led to the arrest, trial and subsequent acquittal of a local slaver captain named Kimber.[63]

19th century

The city was associated with Victorian engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who designed the Great Western Railway between Bristol and London Paddington, two pioneering Bristol-built oceangoing steamships (SS Great Britain and SS Great Western), and the Clifton Suspension Bridge. The new railway replaced the Kennet and Avon Canal, which had fully opened in 1810 as the main route for the transport of goods between Bristol and London.[66] Competition from Liverpool (beginning around 1760), disruptions of maritime commerce due to war with France (1793) and the abolition of the slave trade (1807) contributed to Bristol's failure to keep pace with the newer manufacturing centres of Northern England and the West Midlands. The tidal Avon Gorge, which had secured the port during the Middle Ages, had become a liability. An 1804–09 plan to improve the city's port with a floating harbour designed by William Jessop was a costly error, requiring high harbour fees.[67]

%252C_BRO_Picbox-7-PBA-22%252C_1250x1250.jpg.webp)

During the 19th century, Samuel Plimsoll, known as "the sailor's friend," campaigned to make the seas safer; shocked by overloaded vessels, he successfully fought for a compulsory load line on ships.[68]

By 1867, ships were getting larger and the meanders in the river Avon prevented boats over 300 feet (90 m) from reaching the harbour, resulting in falling trade.[69] The port facilities were migrating downstream to Avonmouth and new industrial complexes were founded there.[70] Some of the traditional industries including copper and brass manufacture went into decline,[71] but the import and processing of tobacco flourished with the expansion of the W.D. & H.O. Wills business.[72]

Supported by new industry and growing commerce, Bristol's population (66,000 in 1801), quintupled during the 19th century,[73] resulting in the creation of new suburbs such as Clifton and Cotham. These provide architectural examples from the Georgian to the Regency style, with many fine terraces and villas facing the road, and at right angles to it. In the early 19th century, the romantic medieval gothic style appeared, partially as a reaction against the symmetry of Palladianism, and can be seen in buildings such as the Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery,[74] the Royal West of England Academy,[75] and The Victoria Rooms.[76] Riots broke out in 1793[77] and 1831; the first over the renewal of tolls on Bristol Bridge, and the second against the rejection of the second Reform Bill by the House of Lords.[78] The population by 1841 had reached 140,158.[79]

The Diocese of Bristol had undergone several boundary changes by 1897 when it was "reconstituted" into the configuration which has lasted into the 21st century.[80]

20th century

From a population of about 330,000 in 1901, Bristol grew steadily during the 20th century, peaking at 428,089 in 1971.[81] Its Avonmouth docklands were enlarged during the early 1900s by the Royal Edward Dock.[82] Another new dock, the Royal Portbury Dock, opened across the river from Avonmouth during the 1970s.[83] As air travel grew in the first half of the century, aircraft manufacturers built factories.[84] The unsuccessful Bristol International Exhibition was held on Ashton Meadows in the Bower Ashton area in 1914.[85] After the premature closure of the exhibition the site was used, until 1919, as barracks for the Gloucestershire Regiment during World War I.[86][87]

Bristol was heavily damaged by Luftwaffe raids during World War II; about 1,300 people living or working in the city were killed and nearly 100,000 buildings were damaged, at least 3,000 beyond repair.[88][89] The original central shopping area, near the bridge and castle, is now a park containing two bombed churches and fragments of the castle. A third bomb-damaged church nearby, St Nicholas was restored and after a period as a museum has now re-opened as a church.[90] It houses a 1756 William Hogarth triptych painted for the high altar of St Mary Redcliffe. The church also has statues of King Edward I (moved from Arno's Court Triumphal Arch) and King Edward III (taken from Lawfords' Gate in the city walls when they were demolished about 1760), and 13th-century statues of Robert, 1st Earl of Gloucester (builder of Bristol Castle) [91] and Geoffrey de Montbray (who built the city's walls) from Bristol's Newgate.[92]

The rebuilding of Bristol city centre was characterised by 1960s and 1970s skyscrapers, mid-century modern architecture and road building. Beginning in the 1980s some main roads were closed, the Georgian-era Queen Square and Portland Square were restored, the Broadmead shopping area regenerated, and one of the city centre's tallest mid-century towers was demolished.[93] Bristol's road infrastructure changed dramatically during the 1960s and 1970s with the development of the M4 and M5 motorways, which meet at the Almondsbury Interchange just north of the city and link Bristol with London (M4 eastbound), Swansea (M4 westbound across the Severn Estuary), Exeter (M5 southbound) and Birmingham (M5 northbound).[94] Bristol was bombed twice by the IRA, in 1974 and again in 1978.[95]

The 20th-century relocation of the docks to Avonmouth Docks and Royal Portbury Dock, 7 miles (11 km) downstream from the city centre, has allowed the redevelopment of the old dock area (the Floating Harbour).[96] Although the docks' existence was once in jeopardy (since the area was seen as a derelict industrial site), the inaugural 1996 International Festival of the Sea held in and around the docks affirmed the area as a leisure asset of the city.[97]

21st century

From 2018, there were lively discussions about a new explicative plaque under a commemorative statue of one of the city's major benefactors in the 17th and 18th centuries. The plaque was meant to replace an original which made no reference to Edward Colston's past with the Royal Africa Company and the Bristol Slave Trade.[98] On 7 June 2020 a statue of Colston was pulled down from its plinth by protestors and pushed into Bristol Harbour.[99] The statue was recovered on 11 June and has become a museum exhibit.[100]

Government

Bristol City council consists of 70 councillors representing 35 wards,[101] with between one and three per ward serving four-year terms. Councillors are elected in thirds, with elections held in three years out of every four-year period. Thus, since wards do not have both councillors up for election at the same time, two-thirds of the wards participate in each election.[102] Although the council was long dominated by the Labour Party, the Liberal Democrats have grown strong in the city and (as the largest party) took minority control of the council after the 2005 United Kingdom general election. In 2007, Labour and the Conservatives united to defeat the Liberal Democrat administration; Labour ruled the council as a minority administration, with Helen Holland as council leader.[103]

In February 2009, the Labour group resigned and the Liberal Democrats re-entered office with a minority administration.[104] In the June 2009 council elections the Liberal Democrats gained four seats and, for the first time, overall control of the city council.[105] In 2010 they increased their representation to 38 seats, giving them a majority of 6.[106] In 2011, they lost their majority; leading to a hung council. In the 2013 local elections, in which a third of the city's wards were up for election, Labour gained 7 seats and the Green Party doubled their seats from 2 to 4. The Liberal Democrats lost 10 seats.[107]

These trends were continued into the next election in May 2014, in which Labour gained three seats to take their total to 31, the Green Party won two more seats, the Conservative party gained one seat, and UKIP won their first-ever seat on the council. The Liberal Democrats lost a further seven seats.[108]

On 3 May 2012, Bristol held a referendum on the question of a directly elected mayor replacing one elected by the council. There were 41,032 votes in favour of a directly elected mayor and 35,880 votes against, with a 24% turnout. An election for the new post was held on 15 November 2012, and Independent candidate George Ferguson became Mayor of Bristol.[109] In May 2022 the city voted to abolish the position in a referendum, replacing it with a committee system. Marvin Rees, mayor in 2022, will hold the post until 2024.[110]

The Lord Mayor of Bristol, not to be confused with the Mayor of Bristol, is a figurehead elected each May by the city council. Councillor Faruk Choudhury was selected by his fellow councillors for the position in 2013. At 38, he was the youngest person to serve as Lord Mayor of Bristol and the first Muslim elected to the office.[111] The current Lord Mayor is Councillor Paula O'Rourke.

Bristol constituencies in the House of Commons also included parts of other local authority areas until the 2010 general election, when their boundaries were aligned with the county boundary. The city is divided into Bristol West, East, South and North West.[112] At the 2017 general election, Labour won all four of the Bristol constituencies, gaining the Bristol North West seat, seven years after losing it to the Conservatives.[113]

The city has a tradition of political activism. Edmund Burke, MP for the Bristol constituency for six years beginning in 1774, insisted that he was a Member of Parliament first and a representative of his constituents' interests second.[114][115] Women's-rights advocate Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence (1867–1954) was born in Bristol,[116] and the left-winger Tony Benn served as MP for Bristol South East in 1950–1960 and again from 1963 to 1983.[117] In 1963 the Bristol Bus Boycott, following the Bristol Omnibus Company's refusal to hire black drivers and conductors, drove the passage of the UK's 1965 Race Relations Act.[118] The 1980 St. Pauls riot protested against racism and police harassment and showed mounting dissatisfaction with the socioeconomic circumstances of the city's Afro-Caribbean residents. Local support of fair trade was recognised in 2005, when Bristol became a fairtrade zone.[119]

Bristol is both a city and a county, since King Edward III granted it a county charter in 1373.[28] The county was expanded in 1835 to include suburbs such as Clifton, and it was named a county borough in 1889 when that designation was introduced.[30]

Former county of Avon

On 1 April 1974, Bristol became a local government district of the county of Avon.[120] On 1 April 1996, Avon was abolished and Bristol became a unitary authority.[121]

The former Avon area, called Greater Bristol by the Government Office of the South West (now abolished) and others,[122] refers to the city and the three neighbouring local authorities—Bath and North East Somerset, North Somerset and South Gloucestershire previously in Avon.

The North Fringe of Bristol, a developed area between the Bristol city boundary and the M4, M5 and M32 motorways (now in South Gloucestershire) was so named as part of a 1987 plan prepared by the Northavon District Council of Avon county.[123]

West of England Combined Authority

The West of England Combined Authority was created on 9 February 2017.[124] Covering Bristol and the rest of the old Avon county with the exception of North Somerset, the new combined authority has responsibility for regional planning, roads, and local transport, and to a lesser extent, education and business investment. The authority's first mayor, Tim Bowles, was elected in May 2017.[125] One of the first actions of the new authority was the announcement of a new train station to be built at Portway.[126]

Geography and environment

Boundaries

Bristol's boundaries can be defined in several ways, including those of the city itself, the developed area, or Greater Bristol.

The city council boundary is the narrowest definition of the city itself. However, it unusually includes a large, roughly rectangular section of the western Severn Estuary ending at (but not including) the islands of Flat Holm (in Cardiff, Wales) and Steep Holm.[127] This "seaward extension" can be traced back to the original boundary of the County of Bristol laid out in the charter granted to the city by Edward III in 1373.[128]

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has defined a Bristol Urban Area, which includes developed areas adjoining Bristol but outside the city-council boundary, such as Kingswood, Mangotsfield, Stoke Gifford, Winterbourne, Almondsbury, Easton in Gordano, Whitchurch village, Filton, Patchway and Bradley Stoke, but excludes undeveloped areas within that boundary.[129]

Geography

Bristol lies within a limestone area running from the Mendip Hills in the south to the Cotswolds in the northeast.[130] The rivers Avon and Frome cut through the limestone to the underlying clay, creating Bristol's characteristically hilly landscape. The Avon flows from Bath in the east, through flood plains and areas which were marshes before the city's growth. To the west the Avon cuts through the limestone to form the Avon Gorge, formed largely by glacial meltwater after the last ice age.[131]

The gorge, which helped protect Bristol Harbour, has been quarried for stone to build the city, and its surrounding land has been protected from development as The Downs and Leigh Woods. The Avon estuary and the gorge form the county boundary with North Somerset, and the river flows into the Severn Estuary at Avonmouth. A smaller gorge, cut by the Hazel Brook which flows into the River Trym, crosses the Blaise Castle estate in northern Bristol.[131]

Bristol is sometimes described, by its inhabitants, as being built on seven hills. From 18th century guidebooks, these 7 hills were known as simply Bristol (the Old Town), Castle Hill, College Green, Kingsdown, St Michaels Hill, Brandon Hill and Redcliffe Hill.[132] Other local hills include Red Lion Hill, Barton Hill, Lawrence Hill, Black Boy Hill, Constitution Hill, Staple Hill, Windmill Hill, Malborough Hill, Nine Tree Hill, Talbot, Brook Hill and Granby Hill.

Bristol is 106 miles (171 km) west of London, 77 miles (124 km) south-southwest of Birmingham and 26 miles (42 km) east of the Welsh capital Cardiff. Areas adjoining the city fall within a loosely defined area known as Greater Bristol. Bath is located 11 miles (18 km) south east of the city centre, Weston-super-Mare is 18 miles (29 km) to the south west, and the Welsh city of Newport is 19 miles (31 km) to the north west.

Climate

The climate is oceanic (Köppen: Cfb), milder than most places in England and United Kingdom.[133][134] Located in southern England, Bristol is one of the warmest cities in the UK with a mean annual temperature of approximately 10.5 °C (50.9 °F).[135][136] It is among the sunniest, with 1,541–1,885 hours of sunshine per year.[137] Although the city is partially sheltered by the Mendip Hills, it is exposed to the Severn Estuary and the Bristol Channel. Annual rainfall increases from north to south, with totals north of the Avon in the 600–900 mm (24–35 in) range and 900–1,200 mm (35–47 in) south of the river.[138] Rain is fairly evenly distributed throughout the year, with autumn and winter the wetter seasons. The Atlantic Ocean influences Bristol's weather, keeping its average temperature above freezing throughout the year, but winter frosts are frequent and snow occasionally falls from early November to late April. Summers are warm and drier, with variable sunshine, rain and clouds, and spring weather is unsettled.[139]

The weather stations nearest Bristol for which long-term climate data are available are Long Ashton (about 5 miles (8 km) south west of the city centre) and Bristol Weather Station, in the city centre. Data collection at these locations ended in 2002 and 2001, respectively, and Filton Airfield is currently the nearest weather station to the city.[140] Temperatures at Long Ashton from 1959 to 2002 ranged from 33.5 °C (92.3 °F) in July 1976[141] to −14.4 °C (6.1 °F) in January 1982.[142] Monthly high temperatures since 2002 at Filton exceeding those recorded at Long Ashton include 25.7 °C (78.3 °F) in April 2003,[143] 34.5 °C (94.1 °F) in July 2006[144] and 26.8 °C (80.2 °F) in October 2011.[145] The lowest recent temperature at Filton was −10.1 °C (13.8 °F) in December 2010.[146] Although large cities in general experience an urban heat island effect, with warmer temperatures than their surrounding rural areas, this phenomenon is minimal in Bristol.[147]

| Climate data for Filton,[lower-alpha 1] elevation: 48 m (157 ft), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1958–present[lower-alpha 2] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.2 (57.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

21.7 (71.1) |

25.7 (78.3) |

27.4 (81.3) |

32.5 (90.5) |

34.5 (94.1) |

33.3 (91.9) |

28.3 (82.9) |

26.8 (80.2) |

17.5 (63.5) |

15.8 (60.4) |

34.5 (94.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.1 (46.6) |

8.5 (47.3) |

10.8 (51.4) |

13.8 (56.8) |

17.0 (62.6) |

19.8 (67.6) |

21.7 (71.1) |

21.3 (70.3) |

18.8 (65.8) |

14.8 (58.6) |

11.0 (51.8) |

8.4 (47.1) |

14.5 (58.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.3 (41.5) |

5.5 (41.9) |

7.3 (45.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

12.7 (54.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

17.6 (63.7) |

17.2 (63.0) |

14.9 (58.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

8.0 (46.4) |

5.6 (42.1) |

10.9 (51.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.4 (36.3) |

2.4 (36.3) |

3.7 (38.7) |

5.5 (41.9) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.4 (52.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

13.2 (55.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

8.3 (46.9) |

5.1 (41.2) |

2.8 (37.0) |

7.3 (45.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −14.4 (6.1) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

0.6 (33.1) |

4.7 (40.5) |

3.9 (39.0) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−11.9 (10.6) |

−14.4 (6.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 82.9 (3.26) |

57.9 (2.28) |

53.3 (2.10) |

47.9 (1.89) |

57.8 (2.28) |

56.3 (2.22) |

58.7 (2.31) |

75.1 (2.96) |

64.3 (2.53) |

85.5 (3.37) |

90.0 (3.54) |

89.9 (3.54) |

819.0 (32.24) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 13.1 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 9.9 | 10.3 | 9.7 | 9.8 | 11.0 | 10.4 | 12.8 | 14.6 | 13.5 | 135.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 61.2 | 78.0 | 122.6 | 174.1 | 206.7 | 219.2 | 220.5 | 189.6 | 153.4 | 107.8 | 68.4 | 56.9 | 1,658.3 |

| Source 1: Met Office[148] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: KNMI[149] | |||||||||||||

- Weather station is located 5 miles (8 km) from the Bristol city centre.

- From 1958–2002, extremes were recorded at Long Ashton. Since 2002, extremes were recorded at Filton.

Environment

Bristol was ranked as Britain's most sustainable city (based on its environmental performance, quality of life, future-proofing and approaches to climate change, recycling and biodiversity), topping environmental charity Forum for the Future's 2008 Sustainable Cities Index.[150][151] Local initiatives include Sustrans (creators of the National Cycle Network, founded as Cyclebag in 1977)[152] and Resourcesaver, a non-profit business established in 1988 by Avon Friends of the Earth.[153] In 2014 The Sunday Times named it as the best city in Britain in which to live.[154] The city received the 2015 European Green Capital Award, becoming the first UK city to receive this award.[155]

In 2019 Bristol City Council voted in favour of banning all privately owned diesel cars from the city centre.[156] Since then, the plans have been revised in favour of a clean air zone whereby older and more polluting vehicles will be charged to drive through the city centre. The Clean Air Zone is currently due to come into effect in Summer 2022.[157]

Green belt

The city has green belt mainly along its southern fringes, taking in small areas within the Ashton Court Estate, South Bristol crematorium and cemetery, High Ridge common and Whitchurch, with a further area around Frenchay Farm. The belt extends outside the city boundaries into surrounding counties and districts, for several miles in places, to afford a protection from urban sprawl to surrounding villages and towns.

Demographics

| Year | Population | Year | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1377 | 9,518[158] | 1901 | 323,698[81] |

| 1607 | 10,549[159] | 1911 | 352,178[81] |

| 1700 | 20,000[81] | 1921 | 367,831[81] |

| 1801 | 68,944[81] | 1931 | 384,204[81] |

| 1811 | 83,922[81] | 1941 | 402,839[81] |

| 1821 | 99,151[81] | 1951 | 422,399[81] |

| 1831 | 120,789[81] | 1961 | 425,214[81] |

| 1841 | 144,803[81] | 1971 | 428,089[81] |

| 1851 | 159,945[81] | 1981 | 384,883[81] |

| 1861 | 194,229[81] | 1991 | 396,559[81] |

| 1871 | 228,513[81] | 2001 | 380,615[81] |

| 1881 | 262,797[81] | 2012 | 432,500[160] |

| 1891 | 297,525[81] | 2017 | 459,300[161] |

In 2014, the Office for National Statistics estimated the Bristol unitary authority's population at 442,474,[162][163] making it the 43rd-largest ceremonial county in England.[163] The ONS, using Census 2001 data, estimated the city's population at 441,556.[164]

According to the 2011 census, 84% of the population was White (77.9% White British, 0.9% White Irish, 0.1% Gypsy or Irish Travellers and 5.1% Other White); 3.6% mixed-race (1.7% white-and-black Caribbean, 0.4% white-and-black African, 0.8% white and Asian and 0.7% other mixed); 5.5% Asian (1.6% Pakistani, 1.5% Indian, 0.9% Chinese, 0.5% Bangladeshi, and 1% other Asian); 6% Black (2.8% African, 1.6% Caribbean, 1.6% Other Black), 0.3% Arab and 0.6% with other heritage. Bristol is unusual among major British towns and cities in its larger black than Asian population.[165] These statistics apply to the Bristol Unitary Authority area, excluding areas of the urban area (2006 estimated population 587,400) in South Gloucestershire, Bath and North East Somerset (BANES) and North Somerset—such as Kingswood, Mangotsfield, Filton and Warmley.[81] 56.2% of the 209,995 Bristol residents who are employed commute to work using either a car, van, motorbike or taxi, 2.2% commute by rail and 9.8% by bus, while 19.6% walk.[166]

Inequality

The Runnymede Trust found in 2017 that Bristol "ranked 7th out of the 348 districts of England & Wales (1=worst) on the Index of Multiple Inequality."[167] In terms of employment, the report found that "ethnic minorities are disadvantaged compared to white British people nationally, but this is to a greater extent in Bristol, particularly for black groups." Black people in Bristol experience the 3rd highest level of educational inequality in England and Wales.[167]

Bristol conurbation

The population of Bristol's contiguous urban area was put at 551,066 by the ONS based on Census 2001 data.[168] In 2006 the ONS estimated Bristol's urban-area population at 587,400,[169] making it England's sixth-most populous city and tenth-most populous urban area.[168] At 3,599 inhabitants per square kilometre (9,321/sq mi) it has the seventh-highest population density of any English district.[170] According to data from 2019, the urban area has the 11th-largest population in the UK with a population of 670,000.[171]

In 2007 the European Spatial Planning Observation Network (ESPON) defined Bristol's functional urban area as including Weston-super-Mare, Bath and Clevedon with a total population of 1.04 million, the twelfth largest of the UK.[172]

Economy

Bristol has a long history of trade, originally exporting wool cloth and importing fish, wine, grain and dairy products;[173] later imports were tobacco, tropical fruits and plantation goods. Major imports are motor vehicles, grain, timber, produce and petroleum products.[174] Since the 13th century, the rivers have been modified for docks; during the 1240s, the Frome was diverted into a deep, man-made channel (known as Saint Augustine's Reach) which flowed into the River Avon.[175][176]

Ships occasionally departed Bristol for Iceland as early as 1420, and speculation exists that sailors (fishermen who landed on the Canadian coast to salt/ smoke their catch) from Bristol made landfall in the Americas before Christopher Columbus or John Cabot.[25] Beginning in the early 1480s, the Bristol Society of Merchant Venturers sponsored exploration of the North Atlantic in search of trading opportunities.[25] In 1552, Edward VI granted a royal charter to the Merchant Venturers to manage the port. Among explorers to depart from the port after Cabot were Martin Frobisher, Thomas James, after whom James Bay, on southern coast of Hudson Bay is named, and Martin Pring, who discovered Cape Cod and the southern New England coast in 1603.[177]

By 1670 the city had 6,000 tons of shipping (of which half was imported tobacco), and by the late 17th and early 18th centuries shipping played a significant role in the slave trade.[25] During the 18th century, Bristol was Britain's second-busiest port;[178] business was conducted in the trading area around The Exchange in Corn Street over bronze tables known as Nails. Although the Nails are cited as originating the phrase "cash on the nail" (immediate payment), the phrase was probably in use before their installation.[179]

The city's economy also relies on the aerospace, defence, media, information technology, financial services and tourism industries.[180][181] The Ministry of Defence (MoD)'s Procurement Executive, later known as the Defence Procurement Agency and Defence Equipment and Support, moved to its headquarters to Abbey Wood, Filton, in 1995. This organisation, with a staff of 12,000 to 13,000, procures and supports MoD equipment.[182] One of the UK's most popular tourist destinations, Bristol was selected in 2009 as one of the world's top-ten cities by international travel publishers Dorling Kindersley in their Eyewitness guides for young adults.[183]

Bristol is one of the eight-largest regional English cities that make up the Core Cities Group, and is ranked as a Gamma level global city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network, the fourth-highest-ranked English city.[184] In 2017 Bristol's gross domestic product was £88.448 billion.[185][186] Its per capita GDP was £46,000 ($65,106, €57,794), which was some 65% above the national average, the third-highest of any English city (after London and Nottingham) and the sixth-highest of any city in the United Kingdom (behind London, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Belfast and Nottingham).[185] According to the 2011 census, Bristol's unemployment rate (claiming Jobseeker's Allowance) was three per cent, compared with two per cent for South West England and the national average of four per cent.[187]

Although Bristol's economy no longer relies upon its port, which was moved to docks at Avonmouth during the 1870s[188] and to the Royal Portbury Dock in 1977 as ship size increased, it is the largest importer of cars to the UK. Until 1991, the port was publicly owned; it is leased, with £330 million invested and its annual tonnage increasing from 3.9 million long tons (4 million tonnes) to 11.8 million (12 million).[189] Tobacco importing and cigarette manufacturing have ceased, but the importation of wine and spirits continues.[190]

The financial services sector employs 59,000 in the city,[191] and 50 micro-electronics and silicon design companies employ about 5,000. In 1983 Hewlett-Packard opened its national research laboratory in Bristol.[192][193] In 2014 the city was ranked seventh in the "top 10 UK destinations" by TripAdvisor.[194]

During the 20th century, Bristol's manufacturing activities expanded to include aircraft production at Filton by the Bristol Aeroplane Company and aircraft-engine manufacturing by Bristol Aero Engines (later Rolls-Royce) at Patchway. Bristol Aeroplane was known for their World War I Bristol Fighter[195] and World War II Blenheim and Beaufighter planes.[195] During the 1950s they were a major English manufacturer of civilian aircraft, known for the Freighter, Britannia and Brabazon. The company diversified into automobile manufacturing during the 1940s, producing hand-built, luxury Bristol Cars at their factory in Filton, and the Bristol Cars company was spun off in 1960.[196] The city also gave its name to Bristol buses, which were manufactured in the city from 1908 to 1983: by Bristol Tramways until 1955, and from 1955 to 1983 by Bristol Commercial Vehicles.[197]

Filton played a key role in the Anglo-French Concorde supersonic airliner project during the 1960s. The British Concorde prototype made its maiden flight from Filton to RAF Fairford on 9 April 1969, five weeks after the French test flight.[198] In 2003 British Airways and Air France decided to discontinue Concorde flights, retiring the aircraft to locations (primarily museums) worldwide. On 26 November 2003 Concorde 216 made the final Concorde flight, returning to Bristol Filton Airport as the centrepiece of a proposed air museum which is planned to include the existing Bristol Aero collection (including a Bristol Britannia).[199]

The aerospace industry remains a major sector of the local economy.[200] Major aerospace companies in Bristol include BAE Systems, a merger of Marconi Electronic Systems and BAe (the latter a merger of BAC, Hawker Siddeley and Scottish Aviation). Airbus[201] and Rolls-Royce are also based at Filton, and aerospace engineering is an area of research at the University of the West of England. Another aviation company in the city is Cameron Balloons, who manufacture hot air balloons;[202] each August the city hosts the Bristol International Balloon Fiesta, one of Europe's largest hot-air balloon festivals.[203]

In 2005 Bristol was named by the UK government one of England's six science cities.[204][205] A £500 million shopping centre, Cabot Circus, opened in 2008 amidst predictions by developers and politicians that the city would become one of England's top ten retail destinations.[206] The Bristol Temple Quarter Enterprise Zone, focused on creative, high-tech and low-carbon industries around Bristol Temple Meads railway station,[207] was announced in 2011[208] and launched the following year.[207] The 70-hectare (170-acre) Urban Enterprise Zone has streamlined planning procedures and reduced business rates. Rates generated by the zone are channelled to five other designated enterprise areas in the region:[209] Avonmouth, Bath, Bristol and Bath Science Park in Emersons Green, Filton, and Weston-super-Mare. Bristol is the only big city whose wealth per capita is higher than that of Britain as a whole. With a highly skilled workforce drawn from its universities, Bristol claims to have the largest cluster of computer chip designers and manufacturers outside Silicon Valley . The wider region has one of the biggest aerospace hubs in the UK, centred on Airbus, Rolls-Royce and GKN at Filton airfield.[210]

Culture

Arts

Bristol has a thriving current and historical arts scene. Some of the modern venues and modern digital production companies have merged with legacy production companies based in old buildings around the city. In 2008 the city was a finalist for the 2008 European Capital of Culture, although the title was awarded to Liverpool.[211] The city was designated "City of Film" by UNESCO in 2017 and has been a member of the Creative Cities Network since then.[212]

The Bristol Old Vic, founded in 1946 as an offshoot of The Old Vic in London, occupies the 1766 Theatre Royal (607 seats) on King Street; the 150-seat New Vic (a studio-type theatre), and a foyer and bar in the adjacent Coopers' Hall (built in 1743). The Theatre Royal, a grade I listed building,[213][214] is the oldest continuously operating theatre in England.[215] The Bristol Old Vic Theatre School (which originated in King Street) is a separate company, and the Bristol Hippodrome is a 1,951-seat theatre for national touring productions. Other smaller theatres include the Tobacco Factory, QEH, the Redgrave Theatre at Clifton College and the Alma Tavern. Bristol's theatre scene features several companies as well as the Old Vic, including Show of Strength, Shakespeare at the Tobacco Factory and Travelling Light. Theatre Bristol is a partnership between the city council, Arts Council England and local residents to develop the city's theatre industry.[216] Several organisations support Bristol theatre; the Residence (an artist-led community) provides office, social and rehearsal space for theatre and performance companies,[217] and Equity has a branch in the city.[218]

The city has many venues for live music, its largest the 2,000-seat Bristol Beacon, previously Colston Hall, named after Edward Colston. Others include the Bristol Academy, The Fleece, The Croft, the Exchange, Fiddlers, the Victoria Rooms, Rough Trade, Trinity Centre, St George's Bristol and several pubs, from the jazz-oriented The Old Duke to rock at the Fleece and indie bands at the Louisiana.[219][220] In 2010 PRS for Music called Bristol the UK's most musical city, based on the number of its members born there relative to the city's population.[221] Since the late 1970s Bristol has been home to bands combining punk, funk, dub and political consciousness. With trip hop and Bristol Sound artists such as Tricky,[222] Portishead[223] and Massive Attack,[224] the list of bands from Bristol is extensive. The city is a stronghold of drum and bass, with artists such as Roni Size's Mercury Prize-winning Reprazent,[225] as DJ Krust,[226] More Rockers[227] and TC.[228] Trip hop and drum & bass music, in particular, is part of the Bristol urban-culture scene which received international media attention during the 1990s.[229] The Downs Festival is also a yearly occurrence where both local and well-known bands play. Since its inception in 2016, it has become a major event in the city.

The Bristol Museum and Art Gallery houses a collection encompassing natural history, archaeology, local glassware, Chinese ceramics and art. The M Shed museum opened in 2011 on the site of the former Bristol Industrial Museum.[230] Both are operated by Bristol Culture and Creative Industries, which also runs three historic houses—the Tudor Red Lodge, the Georgian House and Blaise Castle House; and Bristol Archives.[231] The 18th- and 19th-century portrait painter Thomas Lawrence, 19th-century architect Francis Greenway (designer of many of Sydney's first buildings) were born in the city. The graffiti artist Banksy is believed to be from Bristol, and many of his works are on display in the city.

The Watershed Media Centre and Arnolfini gallery (both in dockside warehouses) exhibit contemporary art, photography and cinema, and the city's oldest gallery is at the Royal West of England Academy in Clifton.[232] The nomadic Antlers Gallery opened in 2010, moving into empty spaces on Park Street, on Whiteladies Road and in the Purifier House on Bristol's Harbourside.[233] Stop-motion animation films and commercials (produced by Aardman Animations) are made in Bristol.[234] Robert Newton, Bobby Driscoll and other cast members of the 1950 Walt Disney film Treasure Island (some scenes were filmed along the harbourside) were visitors to the city along with Walt Disney himself. Bristol is home to the regional headquarters of BBC West and the BBC Natural History Unit.[235] Locations in and around Bristol have featured in the BBC's natural-history programmes, including Animal Magic (filmed at Bristol Zoo).[236]

Bristol is the birthplace of 18th-century poets Robert Southey[237] and Thomas Chatterton.[238] Southey (born on Wine Street in 1774) and his friend, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, married the Fricker sisters from the city.[239] William Wordsworth spent time in Bristol,[240] where Joseph Cottle published Lyrical Ballads in 1798. Actor Cary Grant was born in Bristol, and comedians from the city include Justin Lee Collins,[241] Lee Evans,[242] Russell Howard[243] and writer-comedian Stephen Merchant.[244]

The author John Betjeman wrote a poem called "Bristol". [245] It begins:

Green upon the flooded Avon shone the after-storm-wet-sky,

Quick the struggling withy branches let the leaves of autumn fly,

And a star shone over Bristol, wonderfully far and high.

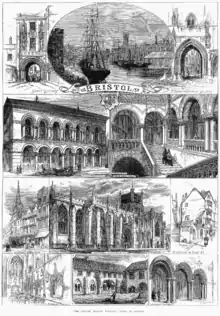

Architecture

Bristol has 51 Grade I,[214] 500 Grade II* and over 3,800 Grade II listed buildings[246] in a variety of architectural styles, from medieval to modern. During the mid-19th century Bristol Byzantine, a style unique to the city, was developed, and several examples have survived. Buildings from most architectural periods of the United Kingdom can be seen in the city. Surviving elements of the fortifications and castle date to the medieval period,[247] and the Church of St James dates back to the 12th century.[248]

The oldest Grade I listed buildings in Bristol are religious. St James' Priory was founded in 1129 as a Benedictine priory by Earl Robert of Gloucester, the illegitimate son of Henry I.[249] The second-oldest is Bristol Cathedral and its associated Great Gatehouse.[250] Founded in 1140, the church became the seat of the bishop and cathedral of the new Diocese of Bristol in 1542. Most of the medieval stonework, particularly the Elder Lady Chapel, is made from limestone taken from quarries around Dundry and Felton with Bath stone being used in other areas.[251] Amongst the other churches included in the list is the 12th-century St Mary Redcliffe which is the tallest building in Bristol. The church was described by Queen Elizabeth I as "the fairest, goodliest, and most famous parish church in England."[252]

Secular buildings include The Red Lodge, built in 1580 for John Yonge as a lodge for a larger house that once stood on the site of the present Bristol Beacon (previously known as Colston Hall). It was subsequently added to in Georgian times and restored in the early 20th century.[253] St Bartholomew's Hospital is a 12th-century town house which was incorporated into a monastery hospital founded in 1240 by Sir John la Warr, 2nd Baron De La Warr (c. 1277–1347), and became Bristol Grammar School from 1532 to 1767, and then Queen Elizabeth's Hospital 1767–1847. The round piers predate the hospital, and may come from an aisled hall, the earliest remains of domestic architecture in the city, which was then adapted to form the hospital chapel.[254] Three 17th-century town houses which were attached to the hospital were incorporated into model workers' flats in 1865, and converted to offices in 1978. St Nicholas's Almshouses were built in 1652[255] to provide care for the poor. Several public houses were also built in this period, including the Llandoger Trow[256] on King Street and the Hatchet Inn.[257]

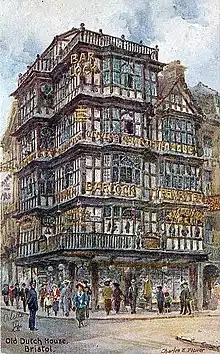

Manor houses include Goldney Hall, where the highly decorated Grotto dates from 1739.[258] Commercial buildings such as the Exchange[259] and Old Post Office[260] from the 1740s are also included in the list. Residential buildings include the Georgian Portland Square[261] and the complex of small cottages around a green at Blaise Hamlet, which was built around 1811 for retired employees of Quaker banker and philanthropist John Scandrett Harford, who owned Blaise Castle House.[262] The 18th-century Kings Weston House, in northern Bristol, was designed by John Vanbrugh and is the only Vanbrugh building in any UK city outside London. Almshouses[263] and pubs from the same period[264] intermingle with modern development. Several Georgian squares were designed for the middle class as prosperity increased during the 18th century.[265] During World War II, the city centre was heavily bombed during the Bristol Blitz.[266] The central shopping area near Wine Street and Castle Street was particularly hard-hit, and the Dutch House and St Peter's Hospital were destroyed. Nevertheless, in 1961 John Betjeman called Bristol "the most beautiful, interesting and distinguished city in England".[267]

Sport

Bristol is represented by professional teams in all the major national sports. Bristol City and Bristol Rovers are the city's main football clubs. Bristol Bears (rugby union) and Gloucestershire County Cricket Club are also based in the city.

The two Football League clubs are Bristol City and Bristol Rovers—the former being the only club from the city to play in the precursor to the Premier League. Non-league clubs include Bristol Manor Farm, Hengrove Athletic, Brislington, Roman Glass St George and Bristol Telephones. Bristol City, formed in 1894, were Division One runners-up in 1907 and lost the FA Cup final in 1909. In the First Division in 1976, they then sank to the bottom professional tier before reforming after a 1982 bankruptcy. 28 October 2000 is a date of significance in the city as it is the last time Bristol Rovers were above Bristol City in the Football league. Bristol City were promoted to the second tier of English football in 2007, losing to Hull City in the playoff for promotion to the Premier League that season.[268] Bristol City Women are based at Twerton Park.[269]

Bristol Rovers, the oldest professional football team in the city, were formed in 1883 and promoted back into the football league in 2015. They were third-tier champions twice (Division Three South in 1952–53 and Division Three in 1989–90), Watney Cup Winners (1972) and runners-up for the Johnstone's Paint Trophy (2006–07) although have never played in England's top Division. The club has planning permission for a new 21,700-capacity all-seater stadium at the University of the West of England's Frenchay campus. Construction was due to begin in mid-2014, but in March 2015 the sale of the Memorial Stadium site (needed to finance the new stadium) was in jeopardy.[270][271]

Bristol Manor Farm are the highest-ranked non-league club within the city boundaries. They play their games at The Creek, Sea Mills,[272] in the north of Bristol. Formed in 1960, the club currently play in the Southern League Division One South having finished the 2016–17 Western League season as champions. They reached the quarter finals of the FA Vase in 2015–16.[273]

The city is also home to Bristol Bears,[274] formed in 1888 as Bristol Football Club by the merger of the Carlton club with rival Redland Park. Westbury Park declined the merger and folded, with many of its players joining what was then Bristol Rugby.[275] Bristol Rugby has often competed at the highest level of the sport since its formation in 1888.[276] The club played at the Memorial Ground, which it shared with Bristol Rovers from 1996. Although Bristol Rugby owned the stadium when the football club arrived, a decline in the rugby club's fortunes led to a transfer of ownership to Bristol Rovers. In 2014 Bristol Rugby moved to their new home, Ashton Gate Stadium (home to Bristol Rovers' rivals Bristol City), for the 2014–15 season.[277][278] They changed their name from Bristol Rugby to Bristol Bears to coincide with their return to Premiership Rugby in 2018–19.

Dating from 1901, the Bristol Combination and its 53 clubs promote rugby union in the city and help support Bristol Bears.[279] The most prominent of Bristol's smaller rugby clubs include Clifton Rugby, Dings Crusaders, and Cleve. Rugby league is represented in Bristol by the Bristol Sonics.[280]

The first-class cricket club Gloucestershire County Cricket Club[281] has its headquarters and plays the majority of its home games at the Bristol County Ground, the only major international sports venue in the south-west of England. It was formed by the family of W. G. Grace.[282] The club is arguably Bristol's most successful, achieving a period of success between 1999 and 2006 when it won nine trophies and became the most formidable one-day outfit in England, including winning a "double double" in 1999 and 2000 (both the Benson and Hedges Cup and the C&G Trophy), and the Sunday League in 2000. Gloucestershire CCC also won the Royal London One-Day Cup in 2015.

The Bristol Flyers basketball team have competed in the British Basketball League, the UK's premier professional basketball league, since 2014.[283] Bristol Aztecs play in Britain's premier American football competition, the BAFA National Leagues.[284] In 2009 ice hockey returned to Bristol after a 17-year absence, with the Bristol Pitbulls playing at Bristol Ice Rink; after its closure, it shared a venue with Oxford City Stars.[285] Bristol sponsors an annual half marathon and hosted the 2001 IAAF World Half Marathon Championships.[286] Athletic clubs in Bristol include Bristol and West AC, Bitton Road Runners and Westbury Harriers. Bristol has staged finishes and starts of the Tour of Britain cycle race[287] and facilities in the city were used as training camps for the 2012 London Olympics.[288] The Bristol International Balloon Fiesta, a major UK hot-air ballooning event, is held each summer at Ashton Court.[289]

Dialect

.jpg.webp)

A dialect of English (West Country English), known as Bristolian, is spoken by longtime residents, who are known as Bristolians.[290] Bristol natives have a rhotic accent, in which the post-vocalic r in car and card is pronounced (unlike in Received Pronunciation). The unique feature of this accent is the 'Bristol (or terminal) l', in which l is appended to words ending in a or o.[291] Whether this is a broad l or a w is a subject of debate,[292] with area pronounced 'areal' or 'areaw'. The ending of Bristol is another example of the Bristol l. Bristolians pronounce -a and -o at the end of a word as -aw (cinemaw). To non-natives, the pronunciation suggests an l after the vowel.[293][294]

Until recently, Bristolese was characterised by retention of the second-person singular, as in the doggerel "Cassn't see what bist looking at? Cassn't see as well as couldst, casst? And if couldst, 'ouldn't, 'ouldst?" The West Saxon bist is used for the English art,[295] and children were admonished with "Thee and thou, the Welshman's cow". In Bristolian, as in French and German, the second-person singular was not used when speaking to a superior (except by the egalitarian Quakers). The pronoun thee is also used in the subject position ("What bist thee doing?"), and I or he in the object position ("Give he to I.").[296] Linguist Stanley Ellis, who found that many dialect words in the Filton area were linked to aerospace work, described Bristolian as "a cranky, crazy, crab-apple tree of language and with the sharpest, juiciest flavour that I've heard for a long time".[297]

Religion

In the 2011 United Kingdom census, 46.8% of Bristol's population identified as Christian and 37.4% said they were not religious; the English averages were 59.4% and 24.7%, respectively. Islam is observed by 5.1% of the population, Buddhism by 0.6%, Hinduism by 0.6%, Sikhism by 0.5%, Judaism by 0.2% and other religions by 0.7%; 8.1% did not identify with a religion.[298]

Among the notable Christian churches are the Anglican Bristol Cathedral and St Mary Redcliffe and the Roman Catholic Clifton Cathedral. Nonconformist chapels include Buckingham Baptist Chapel and John Wesley's New Room in Broadmead.[299] After St James' Presbyterian Church was bombed on 24 November 1940, it was never again used as a church;[300] although its bell tower remains, its nave was converted into offices.[301] The city has eleven mosques,[302] several Buddhist meditation centres,[303] a Hindu temple,[304] Reform and Orthodox-Jewish synagogues[305] and four Sikh temples.[306][307][308]

Bars and nightlife

Bristol has been awarded Purple Flag status[309] on many of its districts, which shows that it meets or surpasses the standards of excellence in managing the evening and night-time economy.

DJ Mag's top 100 club list ranked Motion as the 19th-best club in the world in 2016.[310] This is up 5 spots from 2015.[310] Motion is host to some of the world's top DJs, and leading producers. Motion is a complex made up of different rooms, outdoor space and a terrace that looks over the river Avon.[311] In 2011, Motion was transformed from a skate park into the rave spot it is today.[312] In:Motion is an annual series which takes place each autumn and delivers 12 weeks of music and dancing.[312] The club, on Avon Street, behind Temple Meads train station,[313] does not limit itself to playing one genre of music. Party-goers can hear everything from disco, house, techno, grime, drum and bass or hip hop, depending on the night.[311] In 2020 and 2021, Motion adapted many of its indoor events into outdoor events. Some of these included Bingo Lingdo.[314] Other famous clubs in the city include Lakota and Thekla.

The Attic Bar is a venue located in Stokes Croft.[315] Equipped with a sound system and stage which are used every weekend for gigs of every genre, the bar and the connected Full Moon Pub were rated by The Guardian, a British daily paper, as one of the top ten clubs in the UK.[316] Located by Bristol's harbourside, The Apple is a cider bar which opened in 2004, in a converted Dutch barge, offering a range of 40 different ciders.[317] In 2014, the Great British Pub Awards ranked The Apple as the best cider bar in the UK.[318] Bristol is also home to the pie chain Pieminster started in the Stokes Croft area of the city.

Media

Bristol is home to the regional headquarters of BBC West and the BBC Natural History Unit based at Broadcasting House, which produces television, radio and online content with a natural history or wildlife theme. These include nature documentaries, including The Blue Planet and Planet Earth. The city has a long association with David Attenborough's authored documentaries, including Life on Earth.[319] It was made public in 2021 that the BBC was moving the production of many of its programmes from Broadcasting House to Bridgewater House in Finzels Reach in Bristol City Centre.[320]

Bristol has two daily newspapers, the Western Daily Press and the Bristol Post, (both owned by Reach plc); and a Bristol edition of the free Metro newspaper (owned by DMGT). The Bristol Cable specialises in investigative journalism with a quarterly print edition and website.

Aardman Animations is an Oscar-winning animation studio founded and still based in Bristol. They created famous characters such as Wallace and Gromit and Morph. Its films include Chicken Run (2000), Early Man (2018), shorts such as Creature Comforts and Adam and TV series like Shaun the Sheep and Timmy Time.

The city has several radio stations, including BBC Radio Bristol. Bristol's television productions include Points West for BBC West, Endemol productions such as Deal or No Deal, The Crystal Maze, and ITV News West Country for ITV West Country. The hospital drama Casualty, formerly filmed in Bristol, moved to Cardiff in 2012.[321] In October 2018, Channel 4 announced that Bristol would be home to one of its 'Creative Hubs', as part of their move to produce more content outside of London.[322]

Publishers in the city have included 18th-century Bristolian Joseph Cottle, who helped introduce Romanticism by publishing the works of William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.[323] During the 19th century, J.W. Arrowsmith published the Victorian comedies Three Men in a Boat (by Jerome K. Jerome) and The Diary of a Nobody by George and Weedon Grossmith.[324] The contemporary Redcliffe Press has published over 200 books covering all aspects of the city.[325] Bristol is home to YouTube video developers and stylists The Yogscast, with founders Simon Lane and Lewis Brindley moving their operations from Reading to Bristol in 2012.[326]

Education

.jpg.webp)

Bristol has two major institutions of higher education: the University of Bristol, a redbrick chartered in 1909;[327] and the University of the West of England, opened as Bristol Polytechnic in 1969, which became a university in 1992.[328] The University of Law also has a campus in the city. Bristol has two further education institutions (City of Bristol College and South Gloucestershire and Stroud College) and two theological colleges: Trinity College, and Bristol Baptist College. The city has 129 infant, junior and primary schools,[329] 17 secondary schools,[330] and three learning centres. After a section of north London, Bristol has England's second-highest number of independent school places.[331] Independent schools in the city include Clifton College, Clifton High School, Badminton School, Bristol Grammar School, Queen Elizabeth's Hospital (the only all-boys school) and the Redmaids' School (founded in 1634 by John Whitson, which claims to be England's oldest girls' school).[332]

In 2005, Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown named Bristol one of six English 'science cities',[333] and a £300 million science park was planned at Emersons Green.[334] Research is conducted at the two universities, the Bristol Royal Infirmary and Southmead Hospital, and science outreach is practised at We The Curious, the Bristol Zoo, the Bristol Festival of Nature and the CREATE Centre.[335]

The city has produced a number of scientists, including 19th-century chemist Humphry Davy[336] (who worked in Hotwells). Physicist Paul Dirac (from Bishopston) received the 1933 Nobel Prize for his contributions to quantum mechanics.[337] Cecil Frank Powell was the Melvill Wills Professor of Physics at the University of Bristol when he received the 1950 Nobel Prize for, among other discoveries, his photographic method of studying nuclear processes. Colin Pillinger[338] was the planetary scientist behind the Beagle 2 project, and neuropsychologist Richard Gregory founded the Exploratory (a hands-on science centre which was the predecessor of At-Bristol/We The Curious).[339]

Initiatives such as the Flying Start Challenge encourage an interest in science and engineering in Bristol secondary-school pupils; links with aerospace companies impart technical information and advance student understanding of design.[340] The Bloodhound SSC project to break the land speed record is based at the Bloodhound Technology Centre on the city's harbourside.[341]

Transport

Rail

Railways in the Bristol area | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bristol has two principal railway stations. Bristol Temple Meads (near the city centre) has Great Western Railway services which include high-speed trains to London Paddington and local, regional and CrossCountry trains. Bristol Parkway, north of the city centre, has high-speed Great Western Railway services to Swansea, Cardiff Central and London Paddington and CrossCountry services to Birmingham and east of Northern England. A limited service to London Waterloo, via Clapham Junction, from Temple Meads is operated by South Western Railway and there are scheduled coach links to most major UK cities.[342]

Bristol's principal surviving suburban railway is the Severn Beach Line to Avonmouth and Severn Beach. Although Portishead Railway's passenger service was a casualty of the Beeching cuts, freight service to the Royal Portbury Dock was restored from 2000 to 2002 with a Strategic Rail Authority rail-freight grant. The MetroWest scheme, formerly known as The Greater Bristol Metro, proposes to increase the city's rail capacity[343] including the restoration of a further 3 miles (5 km) of track on the line to Portishead (a dormitory town with one connecting road), is due to open in 2023.[344] A further commuter rail line from Bristol Temple Meads to Henbury, on an existing freight line, is due to open in 2021.[345]

Roads

The M4 motorway connects the city on an east–west axis from London to West Wales, and the M5 is a north–south west axis from Birmingham to Exeter. The M49 motorway is a shortcut between the M5 in the south and the M4 Severn Crossing in the west, and the M32 is a spur from the M4 to the city centre.[342] The Portway connects the M5 to the city centre, and was the most expensive road in Britain when opened in 1926.[346][347]

As of 2019, Bristol is working on plans for a Clean Air Zone to reduce pollution, which could involve charging the most polluting vehicles to enter the city centre.[348][349]

Several road-construction plans, including re-routing and improving the South Bristol Ring Road, are supported by the city council.[350]

Private car use is high in the city, leading to traffic congestion costing an estimated £350 million per year.[351] Bristol allows motorcycles to use most of the city's bus lanes and provides secure, free parking for them.[352]

Public transport

Public transport in the city consists primarily of a First West of England bus network. Other providers are Abus,[353] Stagecoach West, Stagecoach South West and until its sale to Stagecoach West, Wessex Bus.[354][355] Bristol's bus service has been criticised as unreliable and expensive, and in 2005 FirstGroup was fined for delays and safety violations.[356][357]

Although the city council has included a light rail system in its local transport plan since 2000, it has not yet funded the project; Bristol was offered European Union funding for the system, but the Department for Transport did not provide the required additional funding.[358] As of 2019, a four-line mass transit network with potential underground sections is proposed to link Bristol city centre with Bristol Airport via South Bristol, the North Fringe, East Bristol and Bath.[359]

A new bus rapid transit system (BRT) called MetroBus, is currently under construction across Bristol, as of 2018, to provide a faster and more reliable service than buses, improve transport infrastructure and reduce congestion. The MetroBus rapid transit scheme will run on both bus lanes and segregated guided busways on three routes; North Fringe to Hengrove (route m1), Ashton Vale to Bristol Temple Meads (route m2), and Emersons Green to The Centre (route m3).[360] MetroBus services started in 2018.[361]

Three park and ride sites serve Bristol.[362] The city centre has water transport operated by Bristol Ferry Boats, Bristol Packet Boat Trips and Number Seven Boat Trips, providing leisure and commuter service in the harbour.[363]

Cycling

Bristol was designated as England's first "cycling city" in 2008 and one of England's 12 "Cycling demonstration" areas.[364] It is home to Sustrans, the sustainable transport charity. The Bristol and Bath Railway Path links it to Bath, and was the first part of the National Cycle Network. The city also has urban cycle routes and links with National Cycle Network routes to The rest of the Country. Cycling trips increased by 21% from 2001 to 2005.[351]

Air

The runway, terminal and other facilities at Bristol Airport (BRS), Lulsgate, have been upgraded since 2001.[342] In 2019 it was ranked the eighth busiest airport in the United Kingdom, handling nearly 8.9 million passengers, an over 3% increase compared with 2018.[365]

International relations

Bristol was among the first cities to adopt town twinning after World War II.[366][367] Twin towns include:

- Bordeaux, France[368][369] (since 1947)

- Hanover, Germany[370] (since 1947; one of the first post-war twinnings of British and German cities)

- Porto, Portugal (since 1984)[371]

- Tbilisi, Georgia (since 1988)[372]

- Puerto Morazán, Nicaragua (since 1989)[373]

- Beira, Mozambique (since 1990)[374]

- Guangzhou, China (since 2001)[375][376]

Freedom of the City

People and military units receiving the Freedom of the City of Bristol include:

- Billy Hughes: 20 May 1916.[377]

- Kipchoge Keino: 5 July 2012.[378]

- Peter Higgs: 4 July 2013.[379]

- Sir David Attenborough: 17 December 2013.[380]

- The Rifles: 2007, 2015.[381]

- 39 Signal Regiment: 20 March 2019.[382][383]

See also

- Atlantic history

- Bristol Christian Fellowship

- Bristol Pound

- Bristol power stations

- Healthcare in Bristol

- Parks of Bristol

- Subdivisions of Bristol

References

- N. Dermott Harding. Bristol Charters 1155–1373 (PDF). Bristol Record Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- Bevis, Gavin (24 January 2020). "Is Rutland really England's smallest county?". BBC News Online. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- "Bristol". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- "Historical Weather for Bristol, England, United Kingdom". Weatherbase. Canty & Associates. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- "Population Estimates for UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, Mid-2019". Office for National Statistics. 6 May 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "2011 Census: Ethnicgroup, local authorities in England and Wales". Census 2011. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- "The Lord-Lieutenant of the County & City of Bristol". The Lord-Lieutenant of the County & City of Bristol. Archived from the original on 22 October 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- "The population of Bristol - bristol.gov.uk". www.bristol.gov.uk.

- Higgins, David. "The history of the Bristol region in the Roman period" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- James Fawckner Nicholls and John Taylor, Bristol Past and Present: Civil History (1881), p. 6

- Little 1967, p. ix.

- Smith, Gavin (2016). "The City called 'Bridge' by the Hill called 'Stow' - Implications of the Names of Bristol" (PDF). Bristol & Avon Archaeology. 27: 45–48. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- Seyer, Samuel (1823). Memoirs, Historical and Topographical of Bristol and its Neighborhood. Bristol, Printed for the author by J. M. Gutch. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- "Market Towns Of Gloucestershire". oldtowns.co.uk. SDUK Penny Cyclopedia. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- Brace, Keith (1996). Portrait of Bristol. London: Robert Hale. ISBN 978-0-7091-5435-8.

- "Bristow Surname Definition". Forebears.io. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Bates, M.R.; Wenban-Smith, F.F. "Palaeolithic Research Framework for the Bristol Avon Basin" (PDF). Bristol City Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- "Bristol in the Iron Age". Bristol City Council. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- "Abona – Major Romano-British Settlement". Roman-Britain.co.uk.

- "Bristol in the Roman Period". Bristol City Council. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- Lobel & Carus-Wilson 1975, pp. 2–3.

- "The Impregnable City". Bristol Past. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- "Bristol merchants funded Anglo-Norman invasion". Irish Times. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- Jean Manco (2006). "Ricart's View of Bristol". Bristol Magazine. Archived from the original on 14 September 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- Brace 1976, pp. 13–15.

- "The Jewish Community of Bristol". The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.