Clade

A clade (from Ancient Greek κλάδος (kládos) 'branch'), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group,[1] is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree.[2] Rather than the English term, the equivalent Latin term cladus (plural cladi) is often used in taxonomical literature.

The common ancestor may be an individual, a population, or a species (extinct or extant). Clades are nested, one in another, as each branch in turn splits into smaller branches. These splits reflect evolutionary history as populations diverged and evolved independently. Clades are termed monophyletic (Greek: "one clan") groups.

Over the last few decades, the cladistic approach has revolutionized biological classification and revealed surprising evolutionary relationships among organisms.[3] Increasingly, taxonomists try to avoid naming taxa that are not clades; that is, taxa that are not monophyletic. Some of the relationships between organisms that the molecular biology arm of cladistics has revealed include that fungi are closer relatives to animals than they are to plants, archaea are now considered different from bacteria, and multicellular organisms may have evolved from archaea.[4]

The term "clade" is also used with a similar meaning in other fields besides biology, such as historical linguistics; see Cladistics § In disciplines other than biology.

Naming and etymology

The term "clade" was coined in 1957 by the biologist Julian Huxley to refer to the result of cladogenesis, the evolutionary splitting of a parent species into two distinct species, a concept Huxley borrowed from Bernhard Rensch.[5][6]

Many commonly named groups – rodents and insects, for example – are clades because, in each case, the group consists of a common ancestor with all its descendant branches. Rodents, for example, are a branch of mammals that split off after the end of the period when the clade Dinosauria stopped being the dominant terrestrial vertebrates 66 million years ago. The original population and all its descendants are a clade. The rodent clade corresponds to the order Rodentia, and insects to the class Insecta. These clades include smaller clades, such as chipmunk or ant, each of which consists of even smaller clades. The clade "rodent" is in turn included in the mammal, vertebrate and animal clades.

History of nomenclature and taxonomy

The idea of a clade did not exist in pre-Darwinian Linnaean taxonomy, which was based by necessity only on internal or external morphological similarities between organisms. Many of the better known animal groups in Linnaeus' original Systema Naturae (mostly vertebrate groups) do represent clades. The phenomenon of convergent evolution is responsible for many cases of misleading similarities in the morphology of groups that evolved from different lineages.

With the increasing realization in the first half of the 19th century that species had changed and split through the ages, classification increasingly came to be seen as branches on the evolutionary tree of life. The publication of Darwin's theory of evolution in 1859 gave this view increasing weight. Thomas Henry Huxley, an early advocate of evolutionary theory, proposed a revised taxonomy based on a concept strongly resembling clades,[7] although the term clade itself would not be coined until 1957 by his grandson, Julian Huxley. For example, the elder Huxley grouped birds with reptiles, based on fossil evidence.[7]

German biologist Emil Hans Willi Hennig (1913–1976) is considered to be the founder of cladistics.[8] He proposed a classification system that represented repeated branchings of the family tree, as opposed to the previous systems, which put organisms on a "ladder", with supposedly more "advanced" organisms at the top.[3][9]

Taxonomists have increasingly worked to make the taxonomic system reflect evolution.[9] When it comes to naming, this principle is not always compatible with the traditional rank-based nomenclature (in which only taxa associated with a rank can be named) because not enough ranks exist to name a long series of nested clades. For these and other reasons, phylogenetic nomenclature has been developed; it is still controversial.

As an example, see the full current classification of Anas platyrhynchos (the mallard duck) with 40 clades from Eukaryota down by following this Wikispecies link and clicking on "Expand".

The name of a clade is conventionally a plural, where the singular refers to each member individually. A unique exception is the reptile clade Dracohors, which was made by haplology from Latin "draco" and "cohors", i.e. "the dragon cohort"; its form with a suffix added should be e.g. "dracohortian".

Definition

A clade is by definition monophyletic, meaning that it contains one ancestor (which can be an organism, a population, or a species) and all its descendants.[note 1][10][11] The ancestor can be known or unknown; any and all members of a clade can be extant or extinct.

Clades and phylogenetic trees

The science that tries to reconstruct phylogenetic trees and thus discover clades is called phylogenetics or cladistics, the latter term coined by Ernst Mayr (1965), derived from "clade". The results of phylogenetic/cladistic analyses are tree-shaped diagrams called cladograms; they, and all their branches, are phylogenetic hypotheses.[12]

Three methods of defining clades are featured in phylogenetic nomenclature: node-, stem-, and apomorphy-based (see Phylogenetic nomenclature§Phylogenetic definitions of clade names for detailed definitions).

Terminology

The relationship between clades can be described in several ways:

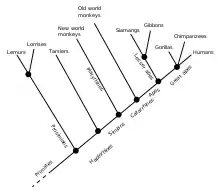

- A clade located within a clade is said to be nested within that clade. In the diagram, the hominoid clade, i.e. the apes and humans, is nested within the primate clade.

- Two clades are sisters if they have an immediate common ancestor. In the diagram, lemurs and lorises are sister clades, while humans and tarsiers are not.

- A clade A is basal to a clade B if A branches off the lineage leading to B before the first branch leading only to members of B. In the adjacent diagram, the strepsirrhine/prosimian clade, is basal to the hominoids/ape clade. In this example, both Haplorrhine as prosimians should be considered as most basal groupings. It is better to say that the prosimians are the sister group to the rest of the primates.[13] This way one also avoids unintended and misconceived connotations about evolutionary advancement, complexity, diversity, ancestor status, and ancienity e.g. due to impact of sampling diversity and extinction.[13][14] Basal clades should not be confused with stem groupings, as the latter is associated with paraphyletic or unresolved groupings.

Age

The age of a clade can be described based on two different reference points, crown age and stem age. The crown age of a clade refers to the age of the most recent common ancestor of all of the species in the clade. The stem age of a clade refers to the time that the ancestral lineage of the clade diverged from its sister clade. A clade's stem age is either the same as or older than its crown age.[15] Note that ages of clades cannot be directly observed. They are inferred, either from stratigraphy of fossils, or from molecular clock estimates.[16]

In popular culture

Clade is the title of a novel by James Bradley, who chose it both because of its biological meaning and also because of the larger implications of the word.[17]

An episode of Elementary is titled "Dead Clade Walking" and deals with a case involving a rare fossil.

See also

- Adaptive radiation

- Binomial nomenclature

- Biological classification

- Cladistics

- Crown group

- Monophyly

- Paraphyly

- Phylogenetic network

- Phylogenetic nomenclature

- Phylogenetics

- Polyphyly

Notes

- A semantic case has been made that the name should be "holophyletic", but this term has not acquired widespread use. For more information, see holophyly.

References

- Martin, Elizabeth; Hin, Robert (2008). A Dictionary of Biology. Oxford University Press.

- Cracraft, Joel; Donoghue, Michael J., eds. (2004). "Introduction". Assembling the Tree of Life. Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-19-972960-9.

- Palmer, Douglas (2009). Evolution: The Story of Life. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 13.

- Pace, Norman R. (18 May 2006). "Time for a change". Nature. 441 (7091): 289. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..289P. doi:10.1038/441289a. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 16710401. S2CID 4431143.

- Dupuis, Claude (1984). "Willi Hennig's impact on taxonomic thought". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 15: 1–24. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.15.110184.000245.

- Huxley, J. S. (1957). "The three types of evolutionary process". Nature. 180 (4584): 454–455. Bibcode:1957Natur.180..454H. doi:10.1038/180454a0. S2CID 4174182.

- Huxley, T.H. (1876): Lectures on Evolution. New York Tribune. Extra. no 36. In Collected Essays IV: pp 46-138 original text w/ figures

- Brower, Andrew V. Z. (2013). "Willi Hennig at 100". Cladistics. 30 (2): 224–225. doi:10.1111/cla.12057.

- ”Evolution 101". page 10. Understanding Evolution website. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- "International Code of Phylogenetic Nomenclature. Version 4c. Chapter I. Taxa". 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- Envall, Mats (2008). "On the difference between mono-, holo-, and paraphyletic groups: a consistent distinction of process and pattern". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 94: 217. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.00984.x.

- Nixon, Kevin C.; Carpenter, James M. (1 September 2000). "On the Other "Phylogenetic Systematics"". Cladistics. 16 (3): 298–318. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2000.tb00285.x. PMID 34902935. S2CID 73530548.

- Krell, F.-T. & Cranston, P. (2004). "Which side of the tree is more basal?". Systematic Entomology. 29 (3): 279–281. doi:10.1111/j.0307-6970.2004.00262.x. S2CID 82371239.

- Smith, Stacey (19 September 2016). "For the love of trees: The ancestors are not among us". For the love of trees. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- Harmon 2021.

- Brower, A. V. Z., Schuh, R. T. 2021. Biological Systematics: Principles and Applications (3rd edn.). Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.

- "Choosing the Book title 'Clade'". Penguin Group Australia. 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

Bibliography

- Harmon, Luke J (3 January 2021). "11.2: Clade Age and Diversity". Biology LibreTexts: Evolutionary Developmental Biology. University of California Davis. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

External links

- Evolving Thoughts: "Clade"

- DM Hillis, D Zwickl & R Gutell. "Tree of life". An unrooted cladogram depicting around 3000 species.

- "Phylogenetic systematics, an introductory slide-show on evolutionary trees" – University of California, Berkeley