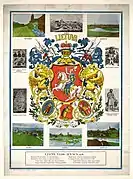

Coat of arms of Lithuania

The coat of arms of Lithuania consists of a mounted armoured knight holding a sword and shield, known as Vytis (pronounced ['vîːtɪs]).[1] Since the early 15th century, it has been Lithuania's official coat of arms and is one of the oldest European coats of arms.[2][3][4] It is also known by other names in various languages, such as Waikymas, Pagaunė[5][6] in the Lithuanian language or as Pogonia, Pogoń, Пагоня (romanized: Pahonia) in the Polish, and Belarusian languages.[2][7][8] Vytis is translatable as Chase, Pursuer, Knight or Horseman, similar to the Slavic vityaz (Old East Slavic for brave, valiant warrior).[9] Historically – raitas senovės karžygys (mounted epic hero of old) or in heraldry – raitas valdovas (mounted sovereign).[9][10][11]

| Coat of arms of Lithuania Lietuvos herbas Vytis (Pogonia, Pahonia) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Armiger | Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Republic of Lithuania |

| Adopted | First documented in 1366. Current version official since 1991. |

| Blazon | Gules, an armoured knight armed cap-à-pie mounted on a horse salient holding in his dexter hand a sword Argent above his head. A shield Azure hangs on the sinister shoulder charged with a double cross (Cross of Lorraine) Or. The horse saddles, straps, and belts Azure. The hilt of the sword and the fastening of the sheath, the stirrups, the curb bits of the bridle, the horseshoes, as well as the decoration of the harness, all Or. |

| Earlier version(s) | see below |

The once powerful and vast Lithuanian state,[12] first as Duchy, then Kingdom, and finally Grand Duchy was created by the initially pagan Lithuanians, in reaction to pressures from the Teutonic Order and Swordbrothers which conquered modern-day Estonia and Latvia, forcibly converting them to Christianity.[13][14][15] The Lithuanians are the only Balts that created a state before the modern era.[16] Moreover, the pressure stimulated Lithuanians to expand their lands eastward into territory of Ruthenian Orthodox in the Dnieper's upper basin and that of the Eurasian nomads in the Eurasian Steppe between lower Dnieper and Dniester, vanquishing present-day Belarusian, Ukrainian, and Russian lands in the process.[14][17][18][19][20] This expansive Lithuania was conveyed in the coat of arms of Lithuania, the galloping horseman.[17][21]

The ruling Gediminid dynasty first adopted the horseback knight as a dynastical symbol which depicted them. Later, in the early 15th century, Grand Duke Vytautas the Great made the mounted knight on a red field the coat of arms of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Ever since, the Lithuanian rulers and nobles related to the ruling dynasty used the coat of arms.[2][8] The knight's shield was designed for decoration with the Columns of Gediminas or the Jagiellonian Double Cross.[22][23] Article 15 of the Constitution of Lithuania, approved by national referendum in 1992, stipulates, "The Coat of Arms of the State shall be a white Vytis on a red field".[24]

Blazoning

The heraldic shield features the field gules (red) with an armoured knight on a horse salient argent (silver). The knight is holding in his dexter hand a sword argent above his head. A shield azure hangs on the sinister shoulder of the knight with a double cross/two-barred cross or (gold) on it. The horse saddle, straps, and belts are azure. The hilt of the sword and the fastening of the sheath, the stirrups, the curb bits of the bridle, the horseshoes, as well as the decoration of the harness, are or (gold).

| Variants employed by institutions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

.svg.png.webp) |

.svg.png.webp) |

|

| |

| President | Seimas | Ministry of Agriculture | Ministry of the Interior | Police | Ministry of National Defence | |

Names of the coat of arms

In early heraldry, a knight on horseback is usually depicted as ready to defend himself and is not yet called Vytis.[2] It is unknown for certain what Lithuania's coat of arms was initially called.[25][26]

Lithuanian language

The origins of the Lithuanian proper noun Vytis are also unclear. At the dawn of the Lithuanian National Revival, Simonas Daukantas employed the term vytis, referring not to the Lithuanian coat of arms, but to the knight, for the first time in his historical piece Budą Senowęs Lietuwiû kalneniu ir Żemaitiû, published in 1846.[27][28] The etymology of this particular word is not universally accepted; it is either a direct translation of the Polish Pogoń, a common noun constructed from the Lithuanian verb vyti ("to chase"), or, less likely, a derivative from the East Slavic vityaz. In western South Slavic languages (Slovenian, Croatian/Serbian/Montenegrin and Macedonian) and Hungarian, vitez denotes the lowest feudal rank, a knight.[29] According to the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, vitez is derived from the Old High German word Witing.[30]

The first presumption, raised by the linguist Pranas Skardžius in 1937, is challenged by some, as Pogoń does not mean "chasing (knight)".[31] In support of the second proposal, the Lithuanian language has words with the stem -vyt in personal names like Vytenis; furthermore, vytis has a structure common to words derived from verbs.[32] According to professor Leszek Bednarczuk, there existed a derivative word vỹtis, vỹčio in the Old Lithuanian language, which translates to English as pursuit (from persekiojimas), chase (from vijimasis).[31]

For the 13th century the Old Prussian word vitingas is attested, meaning "knight" or "nobleman".[33] In today's Lithuania, it can be found in place names, personal names and action verbs.[33] So it is possible that in the Old Lithuanian language there was a similar word describing act of chasing an enemy or an armed horseman chasing an enemy.[33] Another possibility is that Grand Duke Vytenis name is derived from the Old Prussian word vitingas.[6] Therefore, Vytenis' reign (1295-1316) is also associated with the word Vytis as the Ruthenian Hypatian Codex[34] mentions that after beginning to rule the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the 13th century, he came up with a seal with an armored horseman and a sword raised above his head (in the Codex's original Old Church Slavonic it is written that Vytenis named it Pogonia[6]).[35][36][37][38][4]

Several historical sources mention place names which names are probably derived from the Vytis word.[6] A Teutonic source, probably dating from the late 14th century[39] or early 15th century,[40] mentions a place referred to as Wythes Hof.[6][39][41] This is translatable to Vytenis' Court in German.[42] It was located close to the Lithuanian Bisenė fortress, the base for Vytenis' attack on the Teutonic Christmemel fortress in 1315.[42][43] In 1629 Konstantinas Sirvydas used a toponym Vutec Kalnsь (English: Vytis'/Vyties' Mountain) on the basis of a document from Kęsčiai, Karšuva County and associated it with personal names Vygailas, Vytenis, Vytautas.[7] This version is also supported by the fact that the Grand Dukes of Lithuania themselves were depicted on early Lithuanian seals,[2] therefore it is likely that the horseman on the seal of Vytenis was named after him.[6]

In 17th century in his Polish-Latin-Lithuanian dictionary Konstantinas Sirvydas translated the Polish word Pogonia in the sense of the person doing the chasing into Lithuanian as Waykitoias, and in the sense of the act of chasing as Waykimas. Today Waykimas (Vaikymas in the modern Lithuanian orthography) is considered to be the earliest known Lithuanian language name for the coat of arms of Lithuania.[2][44][45][46] Waikymas was also used into the 19th century,[45] together with another Lithuanian name – Pagaunia.

In 1884, Mikalojus Akelaitis referred to the coat of arms of Lithuania per se as Vytis in the Aušra newspaper.[47][48] This name became popular and was eventually became official in the independent Republic of Lithuania. Originally called Vytimi in 1st person Sg. Dat., by the 1930s Vytis came to be called Vyčiu in 1st person Sg. Dat.[47]

.jpg.webp)

Slavic languages

The words pogoń and pogonia have been known in Polish since the 14th century in the sense of "pursuit"[49] or the legal obligation to chase fleeing opponent.[50] It was not until the 16th century that the use of the word appeared to describe an armed horseman.[51][52]

The word came into heraldic use in 1434, when King Władysław II granted a coat of arms with this name (Pogonya) to Mikołaj, the mayor of Lelów. The coat of arms depicted a hand wielding a sword emerging from a cloud. The resemblance to the Lithuanian coat of arms of the king is obvious, so it is possible that it was an abatement of the ruler's coat of arms.[49] The word pogonia to describe the Lithuanian coat of arms in the Polish language for the first time appears in Marcin Bielski's chronicle, published in 1551. However, Bielski makes a mistake, and speaking about the Lithuanian coat of arms he describes Polish noble coat of arms: "From this custom Lithuanian principality uses Pogonia as its coat of arms, that is an armed hand passes a bare sword".[53][54] The term gradually became established with the spread of the Polish language and culture.[2][8][28][52] Pogonia is also found in Prince Roman Sanguszko's documents from 1558 and 1564.[52]

The emblem was described a century earlier, in a document of Supreme Duke Władysław III Jagiellon from 1442 in which he confirmed the rights of the Czartoryski, descendents of Karijotas, to use the armed horseman (Latin: sigillo eorum ducali frui, quo ex avo et patre ipsorum uti consueverunt, scilicet equo, cui subsidet vir armatus, gladium evaginatum in manu tenens; English: to enjoy their duke's seal, which they were accustomed to use from their grandfather and father, namely, a horse on which sits an armed man, holding a drawn sword in his hand[55]), as well as in Jan Długosz's Annales seu cronicae incliti Regni Poloniae or the early 16th-century Bychowiec Chronicle.[52][56] Another popular Polish term was pogończyk.[47] The symbol's meaning and appearance also changed: the old defender of the land became more and more like a rider chasing an enemy.[2] The name Pogonia was first recorded legally in the Third Statute of Lithuania of 1588.[57][58] The Lithuanian Statutes were used not only in Lithuania, but also in White Ruthenia and Little Russia following the Partitions in 1795, into the 19th-century.[59]

Possible early beginnings

.jpg.webp)

The leader of neo-pagan movement Romuva, Lithuanian ethnologist and folklorist Jonas Trinkūnas suggested that the Lithuanian horseman depicts Perkūnas, considered as the god of the Lithuanian soldiers, thunder, lightning, storms, and rain in Lithuanian mythology.[36][60][61] It is believed that the Vytis may represent Perkūnas as supreme god or Kovas who was also a war god and has been depicted as a horseman since ancient times. Very early on, Perkūnas was imagined as a horseman and archeological findings testify that Lithuanians had amulets with horsemen already in the 10th–11th centuries, moreover, Lithuanians were previously buried with their horses who were sacrificed during pagan rituals, and prior to that it is likely that these horses carried the deceased to the burial sites.[36][60][62] One of the pendants made from brass and symbolizing a horseman was found in tumulus in the Plungė District Municipality, dating to the 11th–12th centuries.[63]

Lithuanian mythologists believe that the bright rider on the white horse symbolizes the ghost of the ancestral warrior, reminiscent of core values and goals, giving strength and courage.[64] Gintaras Beresnevičius also points out that a white horse had a sacral meaning to Balts.[65] These interpretations coincide with one of the interpretations of the German coat of arms, that suggests an adler being the bird of Odin, a god of war, which is commonly depicted as a horserider.

Emblems of Lithuania's rulers (before 1400)

The old Lithuanian heraldry of the Lithuanian nobles was characterized by various lines, arrows, framed in shields, colored and passed down from generation to generation.[66] They were mostly used until the Union of Horodło (1413) when 47 Lithuanian families were granted various Polish coat of arms,[67] yet some Samogitian nobles retained old Lithuanian heraldry up to mid-16th century.[68]

The second redaction of the Lithuanian Chronicles, compiled in the 1520s at the court of Albertas Goštautas mentions that semi-legendary Grand Duke Narimantas (late 13th century) was the first Grand Duke to adopt knight on horseback as his and the Grand Duchy's coat of arms. It describes it as an armed man on a white horse, on the red field, with a naked sword over his head as if he was chasing someone, as the author explains that is why it is called "погоня" (pohonia).[21][69] A slightly later edition of the chronicle, so-called Bychowiec Chronicle, tells a similar story, without mentioning coat of arms name: "when Narimantas took the throne of the Grand Duke of Lithuania, he handed his Centaur coat of arms to his brothers and made a coat of arms of a rider with a sword for himself. This coat of arms indicates a mature ruler capable of defending his homeland with a sword".[4][70]

The legend of the adoption of the Lithuanian coat of arms at the time of Narimantas in the version of Bychowiec Chronicle is repeated by later authors: Augustinus Rotundus, Maciej Stryjkowski, Bartosz Paprocki and later historians and heraldists of the 17th and 18th centuries.[71]

Symbols of Mindaugas

.jpg.webp)

We do not know the symbols used by the first rulers of Lithuania. One of the few relics that have survived to our times is the seal of Mindaugas. In 1236 Mindaugas united several Lithuanian tribes and accepted Roman Catholicism in 1251. In 1253 he was crowned by the papal legate as King of Lithuania and his realm was elevated to the rank of a kingdom.[72][16] However the authenticity of a partially survived seal, attached to the act of 1255, according to which Selonia was transferred to the Livonian Order, is disputed.[73][74] According to the 1393 description, when the legend was still intact, the seal of Mindaugas had an inscription: + MYNDOUWE DEI GRA REX LITOWIE (English: Mindaugas, by the grace of God, King of Lithuania).[73]

In 1263, following the assassination of King Mindaugas and his family members by Daumantas and Treniota, Lithuania suffered internal disorder as three of his successors: Treniota, his son-in-law Švarnas, and his son Vaišvilkas were assassinated during the next seven years. Stability returned with Traidenis' reign, designated Grand Duke c. 1270.[75] At a similar time, the ancient Lithuanian capital Kernavė was first mentioned in 1279 in the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle by noting that the Livonian Order's army devastated an area in King Traidenis' lands, which was their main objective (part of early military clashes prior to the Lithuanian Crusade).[76] The coat of arms, seals or symbols of Traidenis are unknown.[77] However, archaeological findings in the 13th and 14th century necropolis in Kernavė offer an astounding variety of symbols and ornaments, of which plants, herbs, palmettes motifs, and suns (swastikas) are one of the most distinct symbols, depicted on the discovered headbands and rings, dating to the pagan period before the Christianization of Lithuania.[77]

Symbols of Gediminas

Grand Duke Gediminas's authentic symbols did not survive to this day. In 1323 Gediminas have sent seven letters to various recipients in western Europe. Their contents are known only from later copies, some of which contain a description of the Gediminas' seal.[78] On 18 July 1323 in Lübeck imperial scribe John of Bremen made a copy of three letters sent by Gediminas on 26 May to the recipients in Saxony,[79] his transcripts contain also a detailed description of the oval waxy seal which was attached to the letter.[80][78] According to the notary's transcript, the oval seal of Gediminas had a twelve corners edging, at the middle of the edging was an image of a man with long hairs, who sat on a throne and held a crown (or a wreath) in his right hand and a sceptre in his left hand, moreover, a cross was engraved around the man along with a Latin inscription: S DEI GRACIA GEDEMINNI LETHWINOR ET RUTKENOR REG (English: Gediminas', by the grace of God, the King of the Lithuanians and the Rus' people, seal).[78][80][81] The cross' usage in a pagan ruler's seal is explained as a diplomatic action because Gediminas did not accept baptism in his life and kept Lithuania pagan, despite several negotiations.[78][82][83] In addition, Gediminas strictly distinguished Lithuania and Lithuanians from the region of Rus' (Ruthenia) and Rus' people (Ruthenians) in legal documents (e.g. in a 1338 Peace and Trade Agreement, concluded in Vilnius, between the Grand Duke Gediminas and his sons and the Master of the Livonian Order Everhard von Monheim).[84]

In 1337, a Lithuanian banner is mentioned for the first time in Wigand of Marburg's chronicles, who wrote that during the battle at Bayernburg Castle (near Veliuona, Lithuania) Tilman Zumpach, head of the Teutonic riflemen, burned the Lithuanian banner with a flaming lance and then mortally wounded the King of Trakai, however, he didn't describe its appearance.[85]

Pečat coins

The most mysterious heraldic symbol of Lithuania is a spearhead with a cross, found on the early Lithuanian coins (also known as PEČAT or ПЕЧАТЬ coins) minted by Jogaila, Vytautas the Great, and possibly Algirdas or Skirgaila.[86][87][88] The mystery concerns the fact that it was used simultaneously by both Jogaila and Vytautas, who fought against each other in the Lithuanian Civil War (1381–1384), therefore it is impossible that Jogaila used his rival's symbol, however it is also not a dynastic symbol like the Columns of Gediminas.[86][88] A particularly important argument for determining the time of minting the Pečat-type coins is the Borshchiv treasure where a Pečat-type coin was found along with the Novgorod Republic's hryvnia, Grand Prince of Kyiv Vladimir Olgerdovich's coins, and Golden Horde's Khans' dirhams (the latest coins of them are of Khan Tokhtamysh, minted in the early 1380s).[86][88] Vladimir Olgerdovich, son and vassal knyaz of Algirdas, minted coins at the Principality of Kyiv since the 1360s, therefore it is highly unlikely that his father Algirdas did not mint his own coins at the late period of his reign.[87][89]

Hence, Pečat-type coins are attributed to Grand Duke Algirdas' reign as well and the use of a cross on a pagan ruler's coins is yet another diplomatic action of the Gediminids (like in his father's Gediminas' seal) because while being a talented diplomat, Algirdas was not baptized in his life and remained pagan as he tortured and executed Anthony, John, and Eustathius (Russian Orthodox Muscovite missionaries) in Vilnius in 1347 for their religion, despite his marriages with Orthodox Princesses Maria of Vitebsk in 1318 and Uliana of Tver in 1349.[78][90][91][92] Regardless, the spearhead with a cross on the anonymous coins could have been created to showcase Algirdas' marriages with Orthodox princesses, especially Uliana of Tver, who was known for her political involvement (e.g. following Algirdas' death in 1377, she advised their son Jogaila to sign the Treaty of Dovydiškės in 1380, which resulted in the murdering of Algirdas's brother Grand Duke Kęstutis,[93] who for his unquestionable support was previously Lithuania's coruler with Algirdas and also a staunch pagan,[94][95] in 1382).[89][88] Moreover, Algirdas unified all modern-day Belarusian and most of the Ukrainian lands under the Lithuanian state and he earned Ukrainian loyalty for respecting Ukrainian culture and their Church.[96] The alleged Seal of Algirdas with arrows and name Olger was proven to be forged by Marian Gumowski, who modified the 1388 Seal of David of Gorodets (David Dmitrovich), husband of Jogaila's sister Maria, which was published by Franciszek Piekosiński, notwithstanding Algirdas in fact had a similar ducal seal, but the original was not visually preserved.[86][88][97] After becoming the ruler of Lithuania, Algirdas was titled the King of Lithuania (Latin: rex Letwinorum) in the Livonian Chronicles instead of the Ruthenian terms knyaz (English: prince, duke) or velikiy knyaz (grand prince).[98][99]

Symbols on coins of Vytautas and Jogaila

.jpg.webp)

Several very rare Lithuanian coins were found with a lion or leopards and the Columns of Gediminas, dated to the reign of Vytautas the Great and Jogaila in the 14th century (one of them was found in Kernavė).[100][101] There is still disagreement where these coins were minted, with the most likely location being Smolensk, other proposed are Polotsk, Vyazma, Bryansk, Ryazan or Vilnius.[100][102][101] Such coins symbolized the Ruthenian vassalship.[102] The leopards were depicted with lily-shaped tails, which symbolized a sovereign ruler, therefore such coins must have been minted after the Pact of Vilnius and Radom in 1401 when Vytautas became fully in charge of the Lithuanian affairs.[100][103] Vytautas minted such coins with leopards in the Principality of Smolensk before its Uprising of 1401 and after 1404 when it became a permanent part of Lithuania.[100] Another type of coins with lion and node symbol are found in eastern Lithuania and Vilnius, researchers associate them with Skirgaila or Jogaila, however such associations lack genuine evidence as the seal of Jogaila attached to the Union of Krewo and the 1382 seal of Skirgaila were not preserved.[104] Despite that, it is possible that the Ruthenian lion also was one of the early coat of arms of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as Jogaila in the Union of Krewo styled himself as: Nos Jagalo virtute Dei dux magnus Litwanorum Rusieque dominus et heres naturalis (English: With God's will of the Grand Duke of Lithuania and the natural lord and heir of Rus).[104] Historian Eugenijus Ivanauskas suggested that the lion was abolished as the Lithuanian coat of arms after the Union of Krewo because in medieval heraldry it was equivalent to the Polish Eagle (lion is the king of animals, while eagle is the king of birds) and Lithuania at the time became a vassal state of the Kingdom of Poland, thus with a lower status.[105][106][107]

Notably, the Lithuanian dukes and nobles declined Uliana of Tver's, Jogaila's mother, suggestion to baptise the Lithuanians as Orthodox before the Union of Krewo and sought Catholicism instead.[108] Grand Duke Jogaila also rejected the Grand Prince of Moscow Dmitry Donskoy's offer to marry his daughter Sofia, convert Lithuania into an Orthodox state and to recognize himself as a vassal of Dmitry Donskoy, instead he chose Catholicism and married Queen Jadwiga of Poland, while also continuing to title himself as ruler of all the Rus' people, therefore minting coins with his portrait (as a horseman) on the obverse and a lion with a braid above him on the reverse, other Jogaila's coins features the Polish Eagle instead of his portrait on one side and a lion on the other side.[109] In 2021, a treasure was discovered in Raišiai, with 40 Jogaila's coins (Denars), some of which are with lions while others are with horsemen wielding swords or spears, most of these coins were minted in 1377–1386 (prior to crowning of Jogaila as the Polish King).[110][111]

The Treasure of Verkiai, discovered in 1941, has 1983 coins of Vytautas the Great which resembles the Pečat-type coins, however, they likely have a crossbow bolt (instead of an arrowhead or a spearhead) and a cross on one side and the Columns of Gediminas on the other side, thus they presumably have been minted later than the Pečat-type coins.[88] Quite a lot of such coins of Vytautas the Great were also found in other places of Lithuania (mostly in the southeastern and central part, but also in Samogitia), Ukraine (especially in Volhynia), and Belarus.[112] In comparison, coins attributed to Jogaila, which have a similar appearance to the Pečat-type coins, has a spearhead and a cross on one side and the Double Cross of the Jagiellonians in a shield on the other side.[88]

Following the Christianization of Lithuania, in ~1388, Grand Duke Jogaila minted new coins: with a fish rolled into a ring (Christian sign of the fish) and inscription КНЯЗЬ ЮГА (English: Duke Jogaila) on the obverse and with a Double Cross of the Jagiellonians in a shield on the reverse.[109] It is believed that such coins were minted to commemorate the Christianization of Lithuania and the Christian sign of the fish could have been chosen when Pope Urban VI officially recognized Lithuania as a Catholic state (such recognition occurred on 17 April 1388).[109] Nevertheless, a fish–blossom symbol, depicted on the coins, can also be associated with an earlier date of 11 March 1388 when Pope Urban VI recognized the Roman Catholic Diocese of Vilnius, which was established by Grand Duke Jogaila.[109] In any case, the main purpose of this symbol was to showcase the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as a Catholic state, recognized and under the auspices of the Pope.[109] Lithuania was the last state in Europe to be Christianized.[113]

Knight on horseback

%252C_minted_in_1388%E2%80%931392.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The coat of arms of Lithuania originate from rulers depictions on seals.[2][47] Originally the riding horseman symbolized the ruler of the Duchy of Lithuania (Duchy of Vilnius), which was the most important land of the state.[114] Algirdas was probably the first ruler to use a seal with a depiction of himself on horseback. The seal, which was attached to Polish-Lithuanian treaty of 1366, wasn't preserved,[47][64] and we know its appearance only thanks to historian Tadeusz Czacki who claimed to have seen the seal.[4][35] The oldest preserved such seal is Jogaila's seal that he was using in years 1377–1380, when he became Grand Duke of Lithuania.[115] Duke of Kernavė Vygantas' seal of 1388 is the oldest preserved seal with a riding knight depicted on the shield, giving it a status of a coat of arms.[116][47] Jogaila and other Algirdas sons: Skirgaila, Lengvenis, Kaributas, Vygantas, and Švitrigaila all were using seals with a horseman-type images.[8][47] The horseman was chosen due to at the time flourishing culture of knighthood in Europe.[64] At first, the charging knight was depicted riding to left or right, and holding a lance instead of the sword: two seals of Lengvenis of 1385 and of 1388 exhibit this change.[117] Initially Kęstutis and his son Vytautas were depicted on their seals as standing warriors. Only later Vytautas adopted, like other Lithuanian dukes, the image of a riding knight.[118]

_with_Vytis_(Waykimas)%252C_1388.jpg.webp)

The establishment of the sword in the heraldry of the Lithuanian rulers is related to the ideological changes of the ruling Gediminids dynasty.[117] The lance was more often exhibited on the seals of Skirgaila and Kaributas.[2] In 1386, after Jogaila was crowned as King of Poland, a new heraldic seal was made for him, with four coat of arms: white eagle, representing Kingdom of Poland, knight on a horse, with lance in hand and a Double Cross on his shield, representing the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and coat of arms Kalisz land and Kuyavia.[119] The Double Cross was adopted by Jogaila after his baptism as Władysław and marriage with a queen Jadwiga of Poland in 1386, daughter of Louis I of Hungary, therefore the Double Cross was most likely taken over from the Kingdom of Hungary where it spread in the 12th century from the Byzantine Empire.[120] It is also possible that the new coat of arms was made in imitation of the Holy Cross relics from the sanctuary of Łysa Góra, and with this gesture the newly crowned king emphasised his sincere faith.[121] The symbolism of the Double Cross was connected with this event's significance for both Jogaila and the entire land.[23] A similar cross in Western heraldry is called the patriarchal Cross of Lorraine, and it is used by archbishops while the cross itself symbolizes baptism.[23]

Columns of Gediminas

The Columns of Gediminas are one of the earliest surviving national symbols of Lithuania and its historical coats of arms.[122] Historian Edmundas Rimša, who analyzed the ancient coins, suggested that the Columns of Gediminas symbolize the Trakai Peninsula Castle Gates.[123] There is no data that they were used by Grand Duke Gediminas himself, and it is believed that their name originated when Gediminas was considered the founder of the Gediminids dynasty.[122] Since 1397, the Columns of the Gediminids were undoubtedly used on Vytautas the Great coat of arms, and it is believed that a similar symbol may have been used by his father Kęstutis, who was Duke of Trakai and Grand Duke of Lithuania, titles which Vytautas inherited.[22][122][124] After Vytautas' death, the symbol was taken over by his brother Grand Duke Sigismund Kęstutaitis.[22] At first, the Columns used to represent the family of Kęstutis, and since the 16th century, when Grand Duke Jogaila's successors started using them in Lithuania as well, the Columns became the symbol of all Gediminids.[22] It was Grand Duke Casimir IV Jagiellon who made the Columns of the Gediminids as the coat of arms of his dynasty after becoming the Grand Duke of Lithuania in 1440.[122] In heraldry, the Columns of Gediminas were usually pictured in gold or yellow on a red field, while they were occasionally portrayed in silver or white since the second half of the 16th century.[22] There is no doubt that the Columns of the Gediminids are of local origin as similar symbols can be found on the insignias of the Lithuanian nobility.[22] It is believed that the Columns of the Gediminids were derived from signs used to mark property.[22]

Compared to the Double Cross of the Jagiellonian dynasty, the Columns of the Gediminids had been used more predominantly in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[22] The Columns of the Gediminids were featured on the Lithuanian coins of the 14th and subsequent centuries; the banners of the regiments led by Grand Duke Vytautas at the Battle of Grunwald; the 15th and 16th century church paraphernalia given to Vilnius Cathedral; the 15th century seals of the Lithuanian Franciscans and major state seals in 1581–1795; book graphics; and the pieces of work by Vilnius' goldsmiths.[22][125][126] Combined with the knight on horseback, the Columns of Gediminas were also embedded on the Lithuanian cannon barrels in the 16th and 17th centuries.[22] The symbol also decorated horse bridles and landmarks of the dominions of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania.[22] In 1572, after the death of the last male Gediminid descendant, Grand Duke Sigismund II Augustus, the Columns of Gedimimas remained in the insignias of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as the secondary (alongside the knight on horseback) coat of arms of the state.[122] In later years, the Columns of Gediminas were called simply as the Columns (it is known from the early 16th century sources).[122]

Official coat of arms of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

15th century

- Coat of arms of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania at the time of Vytautas the Great

Seal of Vytautas the Great with the Lithuanian coat of arms, featuring horseman, in his left hand, circa 14th–15th centuries

Seal of Vytautas the Great with the Lithuanian coat of arms, featuring horseman, in his left hand, circa 14th–15th centuries Seal of Vytautas the Great with Vytis (Waikymas), which features the Columns of Gediminas on the shield, 1404

Seal of Vytautas the Great with Vytis (Waikymas), which features the Columns of Gediminas on the shield, 1404%252C_used_during_the_Council_of_Constance_in_1416.jpg.webp) One of the earliest surviving depictions of Vytis (Waikymas) in a flag of Vytautas the Great. Painted in 1416 by a Portuguese herald, who attended the Council of Constance.[127]

One of the earliest surviving depictions of Vytis (Waikymas) in a flag of Vytautas the Great. Painted in 1416 by a Portuguese herald, who attended the Council of Constance.[127]%252C_used_during_the_Council_of_Constance_from_1414_to_1418_(cropped).jpg.webp) Coat of arms of Vytautas the Great, which features the standing knight of Kęstutaičiai and Vytis (Waikymas), used during the Council of Constance. Painted by Ulrich of Richenthal, 15th century.

Coat of arms of Vytautas the Great, which features the standing knight of Kęstutaičiai and Vytis (Waikymas), used during the Council of Constance. Painted by Ulrich of Richenthal, 15th century. Seal of Sigismund Kęstutaitis with Vytis in his left hand, 15th century.

Seal of Sigismund Kęstutaitis with Vytis in his left hand, 15th century..jpg.webp) Duke Sigismund Korybut and his troops flying the Lithuanian coat of arms in Prague, 15th century

Duke Sigismund Korybut and his troops flying the Lithuanian coat of arms in Prague, 15th century

The meaning of the Lithuanian ruler's coat of arms and the coat of arms of the Lithuanian state was given to the horseman not by Jogaila, but by his cousin, the Grand Duke Vytautas the Great.[2] Firstly, around 1382, he changed the infantry on his coat of arms, inherited from his father Grand Duke Kęstutis, to a horseman, then made the portrait heraldic – in Vytautas' majestic seal (early 15th century), he is surrounded by the coat of arms of lands belonging to him, in one hand he holds a sword, which represents the power of the Grand Duke of Lithuania, in the other hand – a raised shield (on which a horseman is depicted), which, like an apple of royal power, symbolizes the Lithuanian state ruled by him.[2][64] Furthermore, Vytautas the Great minted coins with the horseman on one side and the Columns of Gediminas on the other side.[100]

In the 15th century, Jan Długosz claimed that Vytautas brought forty regiments to the victorious Battle of Grunwald in 1410 and that everyone used red flags of which thirty regiments flags had an embroidered armored horseman with a raised sword riding on a white, sometimes black, bay or dappled horse, while the rest of ten regiments flags had embroidered Columns of Gediminas with which Vytautas marked his elite troops with horses.[85][125][126] According to Długosz, those flags were named after lands or dukes: Vilnius, Kaunas, Trakai, Medininkai, Sigismund Korybut, Lengvenis, and other.[85] It is believed that the regiments with the Columns of Gediminas were brought from Vytautas' homeland (the Duchy of Trakai), and with a horseman – from other areas of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[85] Sigismund Korybut during his visit to Prague at the invitation of the Czech Hussites in 1422 as a delegate of Grand Duke Vytautas the Great, was depicted in a drawing wherein he carries his armorial banner decorated with a white charging knight on a red field; at its top, there is a narrow streamer, which the Germans, in particular, were fond of depicting in the 15th century.[85]

The history between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Lithuanian Jagiellonian dynasty and the Kingdom of Hungary and Kingdom of Croatia is closely related as Władysław III Jagiellon, the eldest son of Władysław II Jagiełło and his Lithuanian wife Sophia of Halshany,[128] was crowned as the King of Hungary and King of Croatia on 15 May 1440 in Visegrád, moreover, following his father's death, he also inherited the title of the Supreme Duke (Supremus Dux) of Grand Duchy of Lithuania, held it in 1434–1444 and presented himself with it, as such share of powers was agreed in the Union of Horodło of 1413 between his father and Grand Duke Vytautas the Great.[129][130][67] The Royal Seal of Władysław III Jagiellon includes a Lithuanian Vytis (Pogonia) with wings laid out above the coat of arms of Hungary and alongside the Polish Eagle.[131]

At the end of the 14th century, the knight on horseback appeared on the first Lithuanian coins, however, this figure had not yet fully formed, therefore in some coins, the knight is depicted as riding to the left, in others – to the right.[3] In some he holds a spear while others depict a sword; the horse can either be standing in place or galloping.[3] The Double Cross was used in isolation on the Lithuanian coins of the late 14th century and on the banner of the royal court referred to in the Lithuanian language as Gončia (English: The Chaser).[23] During Grand Duke Alexander Jagiellon's reign in Lithuania from 1492 to 1506, the depiction of the knight's direction was established – the horse was always galloping to the left (in the heraldic sense – to the right).[3] Also, the knight was for the first time depicted with a scabbard, while the horse – with a horse harness, however, the knight does not yet have on his shoulder a shield with the double-cross of the Jagiellonian dynasty.[3] Moreover, Alexander's coins also depict an eagle as the symbol of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania's dynastic claim to the Polish throne.[3] During the reign of Grand Duke Sigismund I the Old, who ruled Lithuania from 1506 to 1544, the image of the horseman was moved to the other side of the coins – the reverse, thus marking that it was the coin of Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[3] The knight was also for the first time depicted with a shield with the Double-Cross of the Jagiellonian dynasty.[3] In heraldry, such an image of the horseman is only associated with the Lithuanian state.[3] In the 15th century, the Double Cross of the Jagiellonians became an integral part of the Lithuanian coat of arms and was started to be depicted on the horseman's shield.[132]

At the beginning of the 15th century, the colors and composition of the seal became uniform: on a red field a white (silver) charging knight with a sword raised above his head, with a blue shield with a Double Golden Cross to his left shoulder (during the reign of Kęstutaičiai dynasty – red shield with the golden Columns of Gediminas[133]); horse bridles, leather belts and a short girdle – colored in blue.[2][47][134] Metals (gold and silver) and the two most important colors of medieval coats of arms were used for the Lithuanian coat of arms – Gules (red) then meant material, or earthly (life, courage, blood), Azure (blue) – spiritual, or heavenly (heaven, divine wisdom, mind) values.[2][47]

- Lithuanian Coat of arms during the rest of the 15th century

Vytis with Columns of Gediminas from the 15th-century Codex Bergshammar. Attributed to Grand Duke Žygimantas Kęstutaitis.

Vytis with Columns of Gediminas from the 15th-century Codex Bergshammar. Attributed to Grand Duke Žygimantas Kęstutaitis. Royal Seal of Jogaila which features Vytis (Waikymas)

Royal Seal of Jogaila which features Vytis (Waikymas)%252C_used_during_the_Council_of_Constance_from_1414_to_1418.jpg.webp) Flag of Jogaila with the Polish Eagle and Vytis (Waikymas), used during the Council of Constance in 1416

Flag of Jogaila with the Polish Eagle and Vytis (Waikymas), used during the Council of Constance in 1416_from_the_Bavarian_State_Library_(1475).jpg.webp) Lithuanian coat of arms, dating to 1475, which, judging from its archaic look, was likely redrawn from an even earlier painting[127]

Lithuanian coat of arms, dating to 1475, which, judging from its archaic look, was likely redrawn from an even earlier painting[127]_2.jpg.webp) Lithuanian Denar of Grand Duke Casimir IV Jagiellon with horseman and the Columns of Gediminas, 15th century

Lithuanian Denar of Grand Duke Casimir IV Jagiellon with horseman and the Columns of Gediminas, 15th century_from_the_Codex_Bergshammar%252C_1440.jpg.webp) Columns of Gediminas from the 15th-century Codex Bergshammar

Columns of Gediminas from the 15th-century Codex Bergshammar%252C_minted_in_1495%E2%80%931506.jpg.webp) Half-Groschen of Grand Duke Alexander Jagiellon with Vytis (Waikymas) from the late 15th century or early 16th century

Half-Groschen of Grand Duke Alexander Jagiellon with Vytis (Waikymas) from the late 15th century or early 16th century

16th century

Only in the 16th century a distinction between the ruler (Grand Duke) and state emerged (it was the same entity previously), from which time one also finds mention of a state flag.[85] In 1578, Alexander Guagnini was the first to describe such a state flag, according to him the state flag of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was made of red silk and had four tails, its principal side, to the right of the flag staff, was charged with a white mounted knight underneath the ducal crown; the other side bore an image of the Blessed Virgin Mary.[85] The highly revered Blessed Virgin Mary was considered the patron saint of the state of Lithuania, and even the most prominent state dignitaries favoured her image on their flags, thus the saying: "Lithuania – land of Mary".[85] Later only the knight is mentioned embroidered on both sides of the state flag.[85]

After the Union of Lublin, which was signed on 1 July 1569 in Lublin, Poland, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was established, thus a joint coat of arms of the new country was adopted.[47] Its four quarterly fields portrayed, in diagonal, the eagle and the riding knight as the symbols of the two constituent states.[47] Hence, the old colors of the coat of arms of Lithuania, probably influenced by the colors of the coat of arms of Poland (red, white, and yellow), began to change: sometimes the horse blanket was depicted in red or purple, the leather belts in yellow; however the horseman's shield with the golden Double Cross changed less.[2] In 1572, following the death of Grand Duke Sigismund II Augustus, the last male descendant of the Jagiellonian dynasty as he did not leave any male heir to the throne, the Double Cross remained as a symbol in the national coat of arms and was started to be referred to as simply the Cross of Vytis (Waikymas) after losing the connection with the dynasty.[23]

- 16th-century depictions of the Lithuanian Coat of arms

_in_1506_(cropped_from_an_authentic_painting).jpg.webp) A 1506 depiction of Grand Duke Alexander Jagiellon in the Polish Senate, surrounded by Lithuanian and Polish coat of arms, one of them are the golden Columns of Gediminas

A 1506 depiction of Grand Duke Alexander Jagiellon in the Polish Senate, surrounded by Lithuanian and Polish coat of arms, one of them are the golden Columns of Gediminas.jpg.webp) The first page of the Latin copy of Laurentius (1531) of the First Statute of Lithuania. Vytis (Waikymas) is drawn on a damasked shield.

The first page of the Latin copy of Laurentius (1531) of the First Statute of Lithuania. Vytis (Waikymas) is drawn on a damasked shield. Authentic coat of arms of Lithuania with historical colors (gules, argent, or, and azure), circa 1555

Authentic coat of arms of Lithuania with historical colors (gules, argent, or, and azure), circa 1555_and_the_Columns_of_Gediminas%252C_minted_in_1568.jpg.webp) A 1568 Lithuanian coin of Grand Duke Sigismund II Augustus with horseman and the Columns of Gediminas

A 1568 Lithuanian coin of Grand Duke Sigismund II Augustus with horseman and the Columns of Gediminas.jpg.webp) Tapestry with the coat of arms of Grand Duke Sigismund II Augustus

Tapestry with the coat of arms of Grand Duke Sigismund II Augustus Thaler of Grand Duke Stephen Báthory with Vytis (Waikymas) and the Polish Eagle, 1579

Thaler of Grand Duke Stephen Báthory with Vytis (Waikymas) and the Polish Eagle, 1579%252C_Columns_of_Gediminas%252C_Polish_Eagle_and_family_symbol_of_Steponas_Batoras.jpg.webp) Coat of arms of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth with Vytis (Waikymas), decorated with the Columns of Gediminas, used during the reign of Grand Duke Stephen Báthory

Coat of arms of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth with Vytis (Waikymas), decorated with the Columns of Gediminas, used during the reign of Grand Duke Stephen Báthory

17th century to 1795

- 17th-century Coat of arms of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Authentic Vytis (Waikymas) depicted on the Gate of Dawn, which survived annexations

Authentic Vytis (Waikymas) depicted on the Gate of Dawn, which survived annexations%252C_1550-1609.jpg.webp) Coat of arms of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth during the reign of the Vasa dynasty

Coat of arms of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth during the reign of the Vasa dynasty Authentic Vytis (Waikymas) depicted on the outer wall of the Chapel of Saint Casimir

Authentic Vytis (Waikymas) depicted on the outer wall of the Chapel of Saint Casimir Coin of 15 golden Ducats of Grand Duke Sigismund III Vasa with Vytis (Waikymas), 1617

Coin of 15 golden Ducats of Grand Duke Sigismund III Vasa with Vytis (Waikymas), 1617 The Great Seal of Lithuania with Vytis (Waikymas) and Columns of Gediminas, belonging to Władysław IV Vasa

The Great Seal of Lithuania with Vytis (Waikymas) and Columns of Gediminas, belonging to Władysław IV Vasa%252C_1665.jpg.webp) Golden Lithuanian Ducat of Grand Duke John II Casimir Vasa with Vytis (Waikymas), 1665

Golden Lithuanian Ducat of Grand Duke John II Casimir Vasa with Vytis (Waikymas), 1665 Coin of Grand Duke John III Sobieski with Vytis (Waikymas) and the Polish Eagle, 1684

Coin of Grand Duke John III Sobieski with Vytis (Waikymas) and the Polish Eagle, 1684.jpg.webp) Wall fragment of the Polish-Lithuanian coat of arms in the New Grodno Castle

Wall fragment of the Polish-Lithuanian coat of arms in the New Grodno Castle

The Renaissance introduced minor stylistic changes and variations: long feathers waving from the tip of the knight's helm, a long saddle-cloth, the horsetail turned upwards and shaped as nosegay. With these changes, the red flag with its white knight survived until the end of the 18th century and Grand Duke Stanislaus II Augustus was the last Grand Duke of Lithuania to employ it.[85] His flag was colored in crimson, had two tails, and was decorated with the knight on one side and the ruler's monogram – SAR (Stanislaus Augustus Rex) on the other side.[85] SAR monogram was also inscribed on the flagpole finial.[85] In 1795, after the Third Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Grand Duchy of Lithuania was annexed to the Russian Empire, with a smaller part going to the Kingdom of Prussia, and traditional coat of arms of Lithuania, which represented the state for more than four centuries, was abolished and the Russification of Lithuania was imposed.[2]

- 18th-century Lithuanian Coat of arms

Thaler of Grand Duke Augustus II the Strong with Vytis (Waikymas), 1702

Thaler of Grand Duke Augustus II the Strong with Vytis (Waikymas), 1702 Coin of 10 golden Ducats of Grand Duke Augustus III with Vytis (Waikymas), 1756

Coin of 10 golden Ducats of Grand Duke Augustus III with Vytis (Waikymas), 1756%252C_18th_century.jpg.webp) Seal of the Treasury of Lithuania, 18th century

Seal of the Treasury of Lithuania, 18th century.PNG.webp) The 1st Lithuanian National Cavalry Brigade's Grand Seal (late 18th century)

The 1st Lithuanian National Cavalry Brigade's Grand Seal (late 18th century)%252C_1764-1795.jpg.webp) Coat of arms of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, used during the reign of Stanislaus II Augustus, 1764–1795

Coat of arms of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, used during the reign of Stanislaus II Augustus, 1764–1795.jpg.webp) Lithuanian coat of arms with the Jagiellonian Double Cross, depicted by Franz Johann Joseph von Reilly in 1793

Lithuanian coat of arms with the Jagiellonian Double Cross, depicted by Franz Johann Joseph von Reilly in 1793

1795–1918

At first, the charging knight was interpreted as the country's ruler. As time passed, he became a knight who is chasing intruders out of his native country. Such an interpretation was especially popular in the 19th century, and the first half of the 20th century, when Lithuania was part of the Russian Empire and sought its independence.[2] During the Lithuanian National Revival in the 19th century, Lithuanian intellectuals Teodor Narbutt and Simonas Daukantas claimed that the reviving Lithuanian nation is the inheritor of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania heritage, including the Lithuanian coat of arms Vytis (Waikymas), which was widely used in their organized events.[135]

19th-century anti-Russian uprisings

Uprisings to restore the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth like the 1830–31 November Uprising and 1863–64 January Uprising saw Vytis (Waikymas) being used as a symbol of rebellion against the Russian Empire.[136][137][138] The Lithuanian Vytis was widely used alongside the Polish White Eagle throughout the uprisings on flags, banners, coins, banknotes, seals, medals, etc.[139] After the dethronement of Emperor Nicholas I Romanov (Emperor of Russia since 1825, King of Poland 1825–1831) by the Sejm during its proceedings in Warsaw on 25 January 1831, the coats of arms of the Russian Emperors were removed from the mint dies and Polish złotys with Eagle and Vytis were introduced into circulation, which were manufactured at the Warsaw's Banknote Factory and minted at the Warsaw Mint, as on 9 December 1830 the Provisional Government appointed the Bank of Poland to manage the Warsaw Mint.[140]

- Coat of arms of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the Uprisings of 1830–1831 and 1863–1864

.jpg.webp) Relics of the Uprising of 1831, exhibited in the National Museum of Lithuania in Vilnius

Relics of the Uprising of 1831, exhibited in the National Museum of Lithuania in Vilnius%252C_1830-1831.jpg.webp) Coat of arms of the November Uprising, 1830–31

Coat of arms of the November Uprising, 1830–31 Banner with emblem of the November Uprising, 1830—31

Banner with emblem of the November Uprising, 1830—31 The Provisional Government in Warsaw reintroduced Vytis (Pogonia) and Eagle on the coins and banknotes during the 1830–31 November Uprising

The Provisional Government in Warsaw reintroduced Vytis (Pogonia) and Eagle on the coins and banknotes during the 1830–31 November Uprising Painting commemorating Polish–Lithuanian union; ca. 1861. The motto reads "Eternal union".

Painting commemorating Polish–Lithuanian union; ca. 1861. The motto reads "Eternal union". Emblem of the January Uprising, 1863–64

Emblem of the January Uprising, 1863–64

The 1863–64 January Uprising spread especially wide in the ethnic Lithuanian lands, whereas many rebels demanded for a completely independent, sovereign Lithuanian state, however at the time the majority of the Lithuanians decided to support the Polish–Lithuanian union in order to fight the Russian oppression more effectively.[141] In the Soviet times, the 1863–64 January Uprising was interpreted as a class struggle between peasantry and landed aristocracy, while since 1990, it came to be seen in Lithuania as a strife for liberation from the Russian rule.[142] On 22 November 2019, upon the rediscovery of their remains on the Gediminas' Hill, the 1863–64 January Uprising commanders Konstanty Kalinowski and Zygmunt Sierakowski were buried at the Rasos Cemetery in Vilnius, while the flags covering their coffins were presented to the President of Lithuania Gitanas Nausėda and the President of Poland Andrzej Duda.[143]

In the Russian Empire (1795–1915)

Following the partition of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, most of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was absorbed by the Russian Empire and Vytis was incorporated into the Greater Coat of arms of the Russian Empire.[144] Vytis was the coat of arms of the Vilna Governorate following the incorporation of Vilnius and surrounding lands into the Russian Empire.[145][146][147] Statues of Vytis placed on the White Columns of Vilnius greeted visitors at the entrances to Vilnius from 1818 until 1840, when the statues were replaced with the double-headed eagles – the state symbol of the Russian Empire.[148] In 2019, the Mayor of Vilnius Remigijus Šimašius suggested that the White Columns of Vilnius in the city's eldership of Naujamiestis should be restored.[148] A notable example of the coat of arms of Lithuania usage during the Tsarist period is on the bridge railings above the Vilnelė River in Vilnius.[144] Several authentic coat of arms of Lithuania survived the occupations and annexations. For example, on the side wall of the Vilnius Cathedral, on the main portal of the Dominican Church of the Holy Spirit and on the Gate of Dawn.[144][149]

- Use of the Lithuanian coat of arms by the Russian Empire

.jpg.webp) The White Columns of Vilnius (1818–1840) with Vytis (Pogonia), which were later replaced with the double-headed eagles

The White Columns of Vilnius (1818–1840) with Vytis (Pogonia), which were later replaced with the double-headed eagles%252C_19th_century.jpg.webp) Seal of the Duma of the City of Vilnius, 19th century

Seal of the Duma of the City of Vilnius, 19th century%252C_middle_of_the_19th_century.jpg.webp) Seals of the Vilnius University, mid-19th century

Seals of the Vilnius University, mid-19th century

However, in 1845 Tsar Nicholas I confirmed a coat of arms for the Vilna Governorate that closely resembled the historical one.[2] A notable change was the replacement of the Double-Cross of the Jagiellonians with the Patriarchal cross on the knight's shield.[2][150]

- Coat of arms of Imperial Russian Governorates, which were based on the Lithuanian coat of arms

.jpg.webp) Coat of arms of Vitebsk from 1781

Coat of arms of Vitebsk from 1781.jpg.webp) Coat of arms of Grodno Governorate, 1802

Coat of arms of Grodno Governorate, 1802_(1845).png.webp) Coat of arms of Vilna Governorate, 1845

Coat of arms of Vilna Governorate, 1845 Coat of arms of Vitebsk Governorate, 1856

Coat of arms of Vitebsk Governorate, 1856 Coat of arms of the Vilna Governorate with Vytis (Pogonia) and Orthodox cross, 1878

Coat of arms of the Vilna Governorate with Vytis (Pogonia) and Orthodox cross, 1878

_by_Mikalojus_Konstantinas_%C4%8Ciurlionis%252C_1909.jpg.webp)

In 1905, the Great Seimas of Vilnius took place in Vilnius during which the decision to demand wide political autonomy of Lithuania within the Russian Empire was made.[151] It was proposed by the Chairman of the Great Seimas of Vilnius Jonas Basanavičius to recognize the flag of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (a white horse rider on a red bottom) as the flag of Lithuania, but this proposal was rejected due to the negative associations of red color with the 1905 Russian Revolution.[85][152]

_and_Lithuanian_flag_by_Jonas_Vanagaitis.jpg.webp)

1915–1918

The discussions on the national flag resumed during World War I. Following the German Empire occupation of Lithuania in September 1915, the Lithuanians gathered into committees and organizations of various currents, which united their representatives.[152] According to the signatory of the Act of Independence of Lithuania of 16 February 1918 Petras Klimas, they considered the main problems of the reestablishment of Lithuania's statehood, among which one of the main questions were the national colors and the national flag.[152] Although, serious discussions about the Lithuanian state flag and coat of arms resumed only in 1917 when the real prospect of restoring the Lithuanian state emerged.[152]

For the first time, according to Petras Klimas, a specific question of the national flag and national colors was raised at the Lithuanian intelligentsia Consortium Meeting of 6 June 1917 in the premises of the Lithuanian Scientific Society (the so-called Consortium Meeting united Lithuanian intellectuals in Vilnius, such as, Jonas Basanavičius, Povilas Dogelis, Petras Klimas, Jurgis Šaulys, Antanas Smetona, Mykolas Biržiška, Augustinas Janulaitis, Steponas Kairys, Aleksandras Stulginskis, Antanas Žmuidzinavičius).[152] During this Consortium Meeting, Jonas Basanavičius read a report in which he proved that in the past the color of the Lithuanian flag was red and that on the red bottom was depicted a rider with a raised sword on a dapple-grey horse.[152] Jonas Basanavičius suggested continuing this tradition and choosing this option as the flag of the reborn Lithuanian state.[152] There was nobody who opposed it, however considerations began that such variant of the national flag does not solve the issue of the national colors, especially because a red flag without Vytis (Pogonia) could not be used.[152]

As a result, new colors had to be chosen that could form a simple, everyday, easily sewn flag, which would be used alongside the historical flag of Vytis (Waikymas).[152] The members of this meeting established the principle according to which national colors had to be chosen: everyone agreed that it is necessary to choose such colors that are most often found in folk wares, ribbons, aprons, etc.[152] Everyone agreed that such colors are green and red, therefore the task of harmonizing these colors in the flag was assigned to the artist Antanas Žmuidzinavičius, however the searching for a color combination took a long time.[152] Artist and archeologist Tadas Daugirdas', who was invited as a consultant, combinations of the national flag colors varied from those proposed by Antanas Žmuidzinavičius.[152] In general, a question of the number of colors arose as some demanded a green-red flag (such proposal was also supported by the Lithuanian Americans), while the others demanded a tricolor combination.[152] Finding the third color was the most difficult task, even an exhibition of flag projects was held, however, the question was not solved until the Vilnius Conference of 1917, therefore a question of the national colors was included into the agenda of the Vilnius Conference.[152]

During the preparation of the Vilnius Conference, which met in Vilnius and set out the guidelines for the restoration of Lithuania's independence and elected the members of the Council of Lithuania, Antanas Žmuidzinavičius prepared a green-red Lithuanian flag project with whom the Vilnius City Theater Hall (present-day Old Theatre of Vilnius) was decorated.[152] However, the flag proposed by Antanas Žmuidzinavičius seemed gloomy to the Vilnius Conference participants.[152] Consequently, Tadas Daugirdas proposed the flag consisting of green at the top, white in the middle and red at the bottom, but he himself was not fond of such proposal as he preferred the green and red combination because these colors dominated in the Lithuanian cloths.[152] Finally, Tadas Daugirdas proposed to include a narrow yellow line between the other two colors of green and red with the yellow color symbolizing dawn (the first national Lithuanian newspaper was also named Aušra) and rebirth (Lithuanian National Revival).[152] Despite that, Antanas Žmuidzinavičius categorically defended the green and red flag as these colors symbolized love and hope, while the others demanded for a green (at the bottom; symbolizing green fields and meadows), yellow (at the middle; symbolizing yellow blossoms), and red (at the top; symbolizing the rising sun).[152] As a result, the participants of the conference did not decide on the colors of the flag, therefore assigned this question to a commission formed by the Council of Lithuania that consisted of Jonas Basanavičius, Antanas Žmuidzinavičius, and Tadas Daugirdas.[152]

_by_Tadas_Daugirdas.jpg.webp)

On 16 February 1918, the Council of Lithuania declared the Independence of Lithuania and adopted Vytis as its coat of arms with the first drafts of the coat of arms being designed by Tadas Daugirdas and Antanas Žmuidzinavičius.[47][153] On 19 April 1918, the commission accepted a Lithuanian flag project which consisted of three equal width horizontal lines of yellow, green, and red colors.[152] On 25 April 1918, the Council of Lithuania unanimously approved this flag project as the Flag of the State of Lithuania.[152] At the meeting of the same day, it was proposed to raise the tricolor flag of the Lithuanian state above the Tower of the Gediminas' Castle, which was done in the middle of 1918 after difficult negotiations with the German authorities.[152]

Following the occupation of Vilnius by Soviet Russia, the Lithuanian institutions were evacuated to the temporary capital Kaunas in the first days of January 1919. In the temporary capital Kaunas, the historical flag of Lithuania was raised above the Presidential Palace, Palace of Seimas, and on top of the Tower of the Vytautas the Great War Museum (this historical flag was previously adopted by the Council of Lithuania and had a white horseman on a red bottom on one side and the Columns of Gediminas on the other side).[152][153]

Republic of Lithuania in the interwar period

"What is the ideal of our nation? It is inscribed on the symbol of our state, inherited from the ancient times. Other nations have lions, Ares, or other symbols of power in their flags. It is beautiful, it is majestic! We have Vytis, an armored horseman on a horse with a sword in his hand, rushing with gallops. It is beautiful, it is noble! He, as published in the ancient writings, was chanted by the Vaidilas [ a clergymen in the Baltic religion ], sung by the singers. That symbol is the pride of our nation: a symbol of chivalrous justice. Let us never forget him, either in our relations with our minorities or with other states. Until we are faithful to him, no one will defeat us. The knight is righteous, but he is equipped with armors and has a sword in his hand. When necessary, he pulls out the sword and stands up for justice against those who despise it. To depict justice in this way is to feel and act not only statesmanlike, but also nationally."

— Antanas Smetona, the first and last President of interbellum Lithuania (1919–1920, 1926–1940) about the coat of arms of Lithuania.[154][155]

%252C_used_in_1919-1940.jpg.webp)

When Lithuania restored its independence in 1918–1920, several artists produced updated versions of the coat of arms. Almost all included a scabbard, which is not found in its earliest historical versions. A romanticized version by Antanas Žemaitis became the most popular.[2] The horse appeared to be flying through the air (courant). The gear was very ornate. For example, the saddle blanket was very long and divided into three parts.[2] There was no uniform or official version of the coat of arms. To address popular complaints, in 1929 a special commission was set up to analyze the best 16th-century specimens of Vytis to design an official state emblem.[47] Mstislav Dobuzhinsky was the chief artist.[47] The commission worked for 5 years, but its version was never officially confirmed.[47] Meanwhile, a design by Juozas Zikaras was introduced for official use on Lithuanian coins.[2]

The Columns of the Gediminids and the Double Cross of the Jagiellonians were particularly widely used in the first half of the 20th century following the restoration of the independent state of Lithuania on 16 February 1918.[22][23] These symbols, as a distinctive sign, were adopted by the Lithuanian Land Forces, Lithuanian Air Force, and other public authorities.[22][23] It was used to decorate Lithuanian coins, banknotes orders, medals, and insignias and became an attribute of numerous public societies and organizations.[22][23] To commemorate the 500th anniversary of the death of Grand Duke Vytautas the Great, flags decorated with the Columns of the Gediminids were hoisted in Lithuanian cities and towns in 1930.[156] Moreover, in his honor, a Lithuanian state award was instituted in the same year – Order of Vytautas the Great, which was awarded for distinguished services to the State of Lithuania and since 1991 is still conferred nowadays.[157]

In 1919, the Double Cross of the Jagiellonians was named the Cross for Homeland and was featured on one of the highest-ranking Lithuanian state decorations – Order of the Cross of Vytis, which was awarded for acts of bravery performed in defending the freedom and independence of Lithuania (the order was abolished following the occupations of Lithuania, but was re-established in 1991).[23][158] According to a presidential decree of 3 February 1920, issued by the President of Lithuania Antanas Smetona, the Cross for Homeland was renamed to the Cross of Vytis.[23] In 1928, the Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas was instituted and was awarded to the citizens of Lithuania for outstanding performance in civil and public offices (it was also abolished following the occupations of Lithuania, but was re-established in 1991).[159]

Vytis was the state emblem of the Republic of Lithuania until 1940 when the Republic was occupied by the Soviet Union and national symbols were suppressed, those who still displayed them received severe punishments.[22] With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Vytis, together with the Columns of Gediminas and the national flag, became symbols of the independence movement in Lithuania.[22][160] In 1988, Lithuania's Soviet authorities legalized the public display of Vytis (Waikymas).[161]

- Coat of arms of the Republic of Lithuania in the interwar

An unknown version of the First Lithuanian Republic coat-of-arms, probably its greater coat of arms

An unknown version of the First Lithuanian Republic coat-of-arms, probably its greater coat of arms%252C_coat_of_arms_of_Lithuania%252C_designed_by_Antanas_%C5%BDmuidzinavi%C4%8Dius.jpg.webp) A design of Vytis by Antanas Žmuidzinavičius; popular in interwar independent Lithuania

A design of Vytis by Antanas Žmuidzinavičius; popular in interwar independent Lithuania Juozas Zikaras' design (1925), widely used on the interwar independent Lithuania coins

Juozas Zikaras' design (1925), widely used on the interwar independent Lithuania coins A banknote of 10 Lithuanian litas with Vytis and the Columns of the Gediminids (1927)

A banknote of 10 Lithuanian litas with Vytis and the Columns of the Gediminids (1927) A banknote of 5 Lithuanian litas with Vytautas the Great and Vytis, 1929

A banknote of 5 Lithuanian litas with Vytautas the Great and Vytis, 1929 A foreign passport of the Republic of Lithuania with Vytis, used until the 1940 annexation

A foreign passport of the Republic of Lithuania with Vytis, used until the 1940 annexation A fireplace of a sitting-room of Vytautas the Great at the Kaunas Garrison Officers' Club Building

A fireplace of a sitting-room of Vytautas the Great at the Kaunas Garrison Officers' Club Building_in_Panemun%C4%97%252C_Lithuania%252C_1937.jpg.webp) Queen Louise Bridge, which at the time connected the Lithuanian town Panemunė and Prussian city Tilsit, decorated with Vytis in 1937

Queen Louise Bridge, which at the time connected the Lithuanian town Panemunė and Prussian city Tilsit, decorated with Vytis in 1937_and_the_Columns_of_Gediminas_in_Kaunas%252C_1930.jpg.webp) Ministry of Finance of Lithuania Building in Kaunas, decorated with portraits of Antanas Smetona, Vytautas the Great, Vytis and the Columns of Gediminas, 1930

Ministry of Finance of Lithuania Building in Kaunas, decorated with portraits of Antanas Smetona, Vytautas the Great, Vytis and the Columns of Gediminas, 1930 Commander of the Lithuanian Army Stasys Raštikis holds the Lithuanian Army flag with Vytis on obverse side, while a Lithuanian soldier swears his loyalty by kneeling in front of it

Commander of the Lithuanian Army Stasys Raštikis holds the Lithuanian Army flag with Vytis on obverse side, while a Lithuanian soldier swears his loyalty by kneeling in front of it A Lithuanian bomber-reconnaissance monoplane ANBO VIII with the Double Cross of the Jagiellonians, constructed by the Lithuanian aeronautical engineer Antanas Gustaitis, in 1939

A Lithuanian bomber-reconnaissance monoplane ANBO VIII with the Double Cross of the Jagiellonians, constructed by the Lithuanian aeronautical engineer Antanas Gustaitis, in 1939 Lithuanian Vickers Light Tanks M1936 with the Columns of the Gediminids, heading to the Lithuanian capital Vilnius in 1939

Lithuanian Vickers Light Tanks M1936 with the Columns of the Gediminids, heading to the Lithuanian capital Vilnius in 1939 Session of the Provisional Government of Lithuania, which attempted to restore the statehood of the interwar Republic during the June Uprising in Lithuania, in 1941

Session of the Provisional Government of Lithuania, which attempted to restore the statehood of the interwar Republic during the June Uprising in Lithuania, in 1941_in_1946.jpg.webp) The Lithuanian partisans fought with the occupants in 1944–1953, wearing the interwar Lithuanian uniforms and symbols

The Lithuanian partisans fought with the occupants in 1944–1953, wearing the interwar Lithuanian uniforms and symbols

Republic of Lithuania in the post-Cold War era

On March 11, 1990, Lithuania declared its independence and restored all of its pre-war national symbols, including its historic coat of arms Vytis.[47] On March 20, 1990, the Supreme Council of Lithuania approved the description of the State's coat of arms and determined the principal regulations for its use.[47] The design was based on Juozas Zikaras' version.[47] This was to demonstrate that Lithuania was resuming the traditions of the state that existed between 1918–1940. On September 4, 1991, a new design by Arvydas Každailis was approved based on the recommendations of a special Lithuanian Heraldry Commission.[47] It abandoned romantic interwar interpretations, harkening back to the times of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Nevertheless, it re-established the original colors and metals (red, blue, silver, and gold), dating to the reign of Grand Duke Vytautas the Great, but placed the horse and rider in an ostensibly more "defensive" posture, airs above the ground, rather than leaping forward and sword simply elevated rather than poised to strike.[2][47] The revival of historical colors and the historical coat of arms Vytis meant that the Republic of Lithuania is not only the heir and follower of the traditions of statehood of independent Lithuania of 1918–40, but also of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[2] The Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania, adopted by citizens of the Republic of Lithuania in the Constitutional Referendum of 25 October 1992, states that the Coat of Arms of the State shall be a white Vytis on a red field.[24] Despite the newly adopted Každailis' variant of Vytis, the Lithuanian litas coins featured Zikaras' design until they were replaced by the euro in 2015.[162][163]

On 10 April 1990, the Supreme Council – Reconstituent Seimas adopted the Law on the National Coat of Arms, Emblems, and Other Insignias of the Republic of Lithuania, which regulates the usage of the Lithuanian national coat of arms Vytis and the historical national symbols of Lithuania.[164] According to the 6th article of this Law, the historical national symbols of Lithuania are the Double Cross of the Jagiellonians and Columns of Gediminas.[164]

In 2004, Lithuania's Seimas confirmed a new variant of the Vytis on the historical flag of Lithuania, the final design was approved on 17 June 2010.[85][165] It is depicted on a rectangular red fabric, recalling the old battle flags of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[85] The flag does not replace the yellow-green-red tri-color national flag of Lithuania and it is used on special occasions, anniversaries, and buildings of historical significance (e.g. Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania, Trakai Island Castle, Medininkai Castle).[85]

It is currently proposed that a larger version of the coat of arms be adopted. It would feature a line from "Tautiška giesmė", the national anthem of Lithuania, "Vienybė težydi" ("May unity blossom"). The Seimas already uses a larger version of the coat of arms with this phrase as its motto, along with two supporters: the dexter one a griffin argent beaked and membered or, langued gules, and the sinister one a unicorn argent, armed and unguled or, langued gules, and the ducal hat on top of the shield. The President of Lithuania uses the shield and supporters only.

Lithuania joined the Eurozone by adopting the euro on 1 January 2015.[166] The designs of Lithuanian euro coins share a similar national side for all denominations, featuring the Vytis and the country's name in Lithuanian – Lietuva.[163] The design was announced on 11 November 2004 following a public opinion poll conducted by the Bank of Lithuania.[167] The horse is again leaping forward, as in more traditional versions.[163]

Gintautas Genys released a three-tomes historical adventure novel book Pagaunės medžioklė (English: The Hunt for Pagaunė), which analyzes different periods of the history of Lithuania: the first tome, released in 2012, is about the last decade of the 18th century (close to the Third Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth),[168] the second tome, released in 2014, presents the vision of the restoration of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the sticky web of intrigues and conflicts of the monarchs of France, Russia, and Prussia,[169] while the third tome, released in 2019, presents the course of the history of Russia, Poland, and Lithuania from the 1810s to 1860s, consistently and vividly reveals the terrible drama of mutual relations between them.[170]

- Coat of arms of the Republic of Lithuania in the Post-Cold War era

An Anti-Soviet rally in Vingis Park of about 250,000 people in 1988. The Columns of the Gediminids are hanging above the stage.

An Anti-Soviet rally in Vingis Park of about 250,000 people in 1988. The Columns of the Gediminids are hanging above the stage. The presidential version of the coat of arms, as depicted on the Presidential Palace, and the Flag of the President of Lithuania

The presidential version of the coat of arms, as depicted on the Presidential Palace, and the Flag of the President of Lithuania.svg.png.webp) The historical state flag of Lithuania with Vytis

The historical state flag of Lithuania with Vytis.jpg.webp) Modern Lithuanian state flag flying at Trakai

Modern Lithuanian state flag flying at Trakai The current passport of the Republic of Lithuania design

The current passport of the Republic of Lithuania design Litas commemorative coin featuring a historical Vytis

Litas commemorative coin featuring a historical Vytis.jpg.webp) A banknote of 500 Lithuanian litas with Vytis, 2000

A banknote of 500 Lithuanian litas with Vytis, 2000 A coin of 1 Lithuanian Euro with Vytis, used since 1 January 2015

A coin of 1 Lithuanian Euro with Vytis, used since 1 January 2015.png.webp) Flag of the Lithuanian Armed Forces with Vytis

Flag of the Lithuanian Armed Forces with Vytis The Lithuanian soldiers with the Columns of Gediminas during the Battle of Grunwald reconstruction

The Lithuanian soldiers with the Columns of Gediminas during the Battle of Grunwald reconstruction An armoured fighting vehicle Vilkas (Lithuanian variant of Boxer) with the Columns of the Gediminids

An armoured fighting vehicle Vilkas (Lithuanian variant of Boxer) with the Columns of the Gediminids Lithuanian Air Forces aircraft with the Double Cross of the Jagiellonians in 2016

Lithuanian Air Forces aircraft with the Double Cross of the Jagiellonians in 2016 Jotvingis (N42) of the Lithuanian Naval Force using the state flag as jack

Jotvingis (N42) of the Lithuanian Naval Force using the state flag as jack Boundary marker of the Lithuanian Republic

Boundary marker of the Lithuanian Republic

Similar coats of arms

Lithuania

Recently adopted coats of arms of Vilnius and Panevėžys counties use different color schemes and add additional details to the basic image of the knight.[171] Several towns in Lithuania use motifs similar to Vytis. For example, the coat of arms of Liudvinavas is parted per pale. One half depicts the Vytis and the other, Lady Justice.[172]

- Coats of arms of the Lithuanian counties, cities, and towns which features a horseman

Ethnographic region Aukštaitija coat of arms

Ethnographic region Aukštaitija coat of arms Vilnius University coat of arms

Vilnius University coat of arms Vilnius County coat of arms

Vilnius County coat of arms Liudvinavas coat of arms

Liudvinavas coat of arms Panevėžys County coat of arms

Panevėžys County coat of arms Veiviržėnai coat of arms

Veiviržėnai coat of arms Josvainiai coat of arms

Josvainiai coat of arms Marijampolė coat of arms

Marijampolė coat of arms Daugailiai coat of arms

Daugailiai coat of arms Adutiškis coat of arms

Adutiškis coat of arms

Poland

As Lithuania and Poland were closely related for centuries, especially during the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth period, the Lithuanian coat of arms was also depicted in Poland.[139]

- Usage of Vytis (Pogonia) in Poland

Vytis (Pogonia) is depicted on one of the Wawel Castle's towers in Kraków, alongside the Polish Eagle and the Double Cross of the Jagiellonians

Vytis (Pogonia) is depicted on one of the Wawel Castle's towers in Kraków, alongside the Polish Eagle and the Double Cross of the Jagiellonians

-POL%252C_Krak%C3%B3w.jpg.webp) Vytis (Pogonia) as depicted on the façade of the Collegium Novum of the Jagiellonian University in Kraków

Vytis (Pogonia) as depicted on the façade of the Collegium Novum of the Jagiellonian University in Kraków.jpg.webp) Illustration with coat of arms of John I Albert (after 1492)

Illustration with coat of arms of John I Albert (after 1492)%252C_Polish_Eagle_and_his_personal_coat_of_arms%252C_1780.png.webp) Illustration with coat of arms of Stanislaw August Poniatowski, 1780

Illustration with coat of arms of Stanislaw August Poniatowski, 1780 Białystok Voivodeship (1919–1939) and Podlaskie Voivodeship (1513–1795) coat of arms

Białystok Voivodeship (1919–1939) and Podlaskie Voivodeship (1513–1795) coat of arms Podlaskie Voivodeship coat of arms

Podlaskie Voivodeship coat of arms Byalistok coat of arms

Byalistok coat of arms Brańsk coat of arms

Brańsk coat of arms Puławy coat of arms

Puławy coat of arms Siedlce coat of arms

Siedlce coat of arms_(12).JPG.webp) Church of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Piaseczno

Church of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Piaseczno Malbork Castle, Malbork, 1590s

Malbork Castle, Malbork, 1590s Wawel, Kraków

Wawel, Kraków Wawel, Kraków

Wawel, Kraków Royal Castle, Warsaw, 17th century

Royal Castle, Warsaw, 17th century Royal Castle, Warsaw, Warsaw, 18th century

Royal Castle, Warsaw, Warsaw, 18th century.jpg.webp) Post milestone, Lubań, 1725

Post milestone, Lubań, 1725 Royal Castle, Warsaw, Warsaw, 18th century

Royal Castle, Warsaw, Warsaw, 18th century Łazienki Park, Warsaw, 18th century

Łazienki Park, Warsaw, 18th century

Guardhouse, Poznań, 1780s

Guardhouse, Poznań, 1780s

Belarus

.svg.png.webp)