Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States.[6] Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas to the south and Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska to the west. In the south are the Ozarks, a forested highland, providing timber, minerals, and recreation. The Missouri River, after which the state is named, flows through the center into the Mississippi River, which makes up the eastern border. With more than six million residents, it is the 19th-most populous state of the country. The largest urban areas are St. Louis, Kansas City, Springfield and Columbia; the capital is Jefferson City.

Missouri | |

|---|---|

| State of Missouri | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): Show Me State, Cave State and Mother of the West | |

| Motto: Salus populi suprema lex esto (Latin) Let the good of the people be the supreme law | |

| Anthem: "Missouri Waltz" | |

Map of the United States with Missouri highlighted | |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Missouri Territory |

| Admitted to the Union | August 10, 1821 (24th) |

| Capital | Jefferson City |

| Largest city | Kansas City |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Greater St. Louis |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Mike Parson (R) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Mike Kehoe (R) |

| Legislature | General Assembly |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| Judiciary | Supreme Court of Missouri |

| U.S. senators | Roy Blunt (R) Josh Hawley (R) |

| U.S. House delegation | 6 Republicans 2 Democrats (list) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 69,715 sq mi (180,560 km2) |

| • Land | 68,886 sq mi (179,015 km2) |

| • Rank | 21st |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 300 mi (480 km) |

| • Width | 241 mi (390 km) |

| Elevation | 800 ft (244 m) |

| Highest elevation (Taum Sauk Mountain[1]) | 1,773 ft (540 m) |

| Lowest elevation (St. Francis River at Arkansas border) | 230 ft (70 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 6,160,281[2] |

| • Rank | 19th |

| • Density | 88.2/sq mi (34.1/km2) |

| • Rank | 30th |

| • Median household income | $53,578[3] |

| • Income rank | 38th |

| Demonym | Missourian |

| Language | |

| • Official language | English |

| • Spoken language |

|

| Time zone | UTC−06:00 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−05:00 (CDT) |

| USPS abbreviation | MO |

| ISO 3166 code | US-MO |

| Traditional abbreviation | Mo. |

| Latitude | 36° 0′ N to 40° 37′ N |

| Longitude | 89° 6′ W to 95° 46′ W |

| Website | www |

| Missouri state symbols | |

|---|---|

Flag of Missouri | |

| |

| Living insignia | |

| Amphibian | American bullfrog |

| Bird | Eastern bluebird |

| Fish | Channel catfish |

| Flower | White hawthorn |

| Grass | Big bluestem |

| Horse breed | Missouri Fox Trotter |

| Insect | Western honey bee |

| Mammal | Missouri Mule |

| Tree | Flowering Dogwood |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Dance | Square dance |

| Dinosaur | Hypsibema missouriensis[4] |

| Food | Dessert: Ice cream |

| Fossil | Crinoid |

| Gemstone | Beryl |

| Instrument | Fiddle |

| Mineral | Galena |

| Rock | Mozarkite |

| Soil | Menfro |

| Song | Missouri Waltz |

| Other | Paw-paw (fruit tree)[5] |

| State route marker | |

| |

| State quarter | |

Released in 2003 | |

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

Humans have inhabited what is now Missouri for at least 12,000 years. The Mississippian culture, which emerged at least in the ninth century, built cities and mounds before declining in the 14th century. When European explorers arrived in the 17th century, they encountered the Osage and Missouria nations. The French incorporated the territory into Louisiana, founding Ste. Genevieve in 1735 and St. Louis in 1764. After a brief period of Spanish rule, the United States acquired Missouri as part of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Americans from the Upland South, including enslaved African Americans, rushed into the new Missouri Territory. Missouri was admitted as a slave state as part of the Missouri Compromise of 1820. Many from Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee settled in the Boonslick area of Mid-Missouri. Soon after, heavy German immigration formed the Missouri Rhineland.

Missouri played a central role in the westward expansion of the United States, as memorialized by the Gateway Arch. The Pony Express, Oregon Trail, Santa Fe Trail and California Trail all began in Missouri.[7] As a border state, Missouri's role in the American Civil War was complex, and it was subject to rival governments, raids, and guerilla warfare. After the war, both Greater St. Louis and the Kansas City metropolitan area became centers of industrialization and business. Today the state is divided into 114 counties and the independent city of St. Louis.

Missouri's culture blends elements of the Midwestern and Southern United States. It is the birthplace of the musical genres ragtime, Kansas City jazz and St. Louis blues. The well-known Kansas City-style barbecue, and the lesser-known St. Louis-style barbecue, can be found across the state and beyond. Missouri is a major center of beer brewing and has some of the most permissive alcohol laws in the U.S.[8] It is home to Anheuser-Busch, the world's largest beer producer, and produces an eponymous wine produced in the Missouri Rhineland and Ozarks. Outside the state's major cities, popular tourist destinations include the Lake of the Ozarks, Table Rock Lake and Branson.

Well-known Missourians include Chuck Berry, Sheryl Crow, Walt Disney, Edwin Hubble, Nelly, Brad Pitt, Harry S. Truman, and Mark Twain. Some of the largest companies based in the state include Cerner, Express Scripts, Monsanto, Emerson Electric, Edward Jones, H&R Block, Wells Fargo Advisors, Centene Corporation, and O'Reilly Auto Parts. Well-known universities in Missouri include the University of Missouri, Saint Louis University, Washington University in St. Louis.[9] Missouri has been called the "Mother of the West" and the "Cave State", but its most famous nickname is the "Show Me State".[10]

Etymology and pronunciation

The state is named for the Missouri River, which was named after the indigenous Missouri Indians, a Siouan-language tribe. It is said they were called the ouemessourita (wimihsoorita),[11] meaning "those who have dugout canoes", by the Miami-Illinois language speakers.[12]

Assuming Missouri were deriving from the Siouan language, it could come from "Maya Sunni" (MAH-yah SOO-nee), which translates as "It connects to the side of it", in reference to the river itself.[13] Most likely, though, the name Missouri comes from Chiwere, a Siouan language spoken by people who resided in the modern-day states of Wisconsin, Iowa, South Dakota, Missouri, and Nebraska.

The name Missouri has several different pronunciations even among its present-day inhabitants,[14] the two most common being /mɪˈzɜːri/ (![]() listen) mə-ZUR-ee and /mɪˈzɜːrə/ (

listen) mə-ZUR-ee and /mɪˈzɜːrə/ (![]() listen) mə-ZUR-ə.[15][16] Further pronunciations also exist in Missouri or elsewhere in the United States, involving the realization of the medial consonant as either /z/ or /s/; the vowel in the second syllable as either /ɜːr/ or /ʊər/;[17] and the third syllable as /i/ (phonetically [i] (

listen) mə-ZUR-ə.[15][16] Further pronunciations also exist in Missouri or elsewhere in the United States, involving the realization of the medial consonant as either /z/ or /s/; the vowel in the second syllable as either /ɜːr/ or /ʊər/;[17] and the third syllable as /i/ (phonetically [i] (![]() listen), [ɪ] (

listen), [ɪ] (![]() listen), or [ɪ̈] (

listen), or [ɪ̈] (![]() listen)) or /ə/.[16] Any combination of these phonetic realizations may be observed coming from speakers of American English. In British received pronunciation, the preferred variant is /mɪˈzʊəri/, with /mɪˈsʊəri/ being a possible alternative.[18][19]

listen)) or /ə/.[16] Any combination of these phonetic realizations may be observed coming from speakers of American English. In British received pronunciation, the preferred variant is /mɪˈzʊəri/, with /mɪˈsʊəri/ being a possible alternative.[18][19]

The linguistic history was treated definitively by Donald M. Lance, who acknowledged that the question is sociologically complex, but no pronunciation could be declared "correct", nor could any be clearly defined as native or outsider, rural or urban, southern or northern, educated or otherwise.[20] Politicians often employ multiple pronunciations, even during a single speech, to appeal to a greater number of listeners.[14] In informal contexts respellings of the state's name, such as "Missour-ee" or "Missour-uh", are occasionally used to distinguish pronunciations phonetically.

Nicknames

There is no official state nickname.[21] However, Missouri's unofficial nickname is the "Show Me State," which appears on its license plates. This phrase has several origins. One is popularly ascribed to a speech by Congressman Willard Vandiver in 1899, who declared that "I come from a state that raises corn and cotton, cockleburs and Democrats, and frothy eloquence neither convinces nor satisfies me. I'm from Missouri, and you have got to show me." This is in keeping with the saying "I'm from Missouri," which means "I'm skeptical of the matter and not easily convinced."[22] However, according to researchers, the phrase "show me" was already in use before the 1890s.[23] Another one states that it is a reference to Missouri miners who were taken to Leadville, Colorado to replace striking workers. Since the new men were unfamiliar with the mining methods, they required frequent instruction.[21]

Other nicknames for Missouri include "The Lead State", "The Bullion State", "The Ozark State", "The Mother of the West", "The Iron Mountain State", and "Pennsylvania of the West".[24] It is also known as the "Cave State"[25]: 53 because there are more than 7,300 recorded caves in the state (second to Tennessee). Perry County is the county with the largest number of caves and the single longest cave.[26][27]

The official state motto is Latin: "Salus Populi Suprema Lex Esto", which means "Let the welfare of the people be the supreme law."[28]

History

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

Early history

Archaeological excavations along river valleys have shown continuous habitation since about 9000 BCE.[29] Beginning before 1000 CE, the people of the Mississippian culture created regional political centers at present-day St. Louis and across the Mississippi River at Cahokia, near present-day Collinsville, Illinois. Their large cities included thousands of individual residences. Still, they are known for their surviving massive earthwork mounds, built for religious, political and social reasons, in platform, ridgetop and conical shapes. Cahokia was the center of a regional trading network that reached from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico. The civilization declined by 1400 CE, and most descendants left the area long before the arrival of Europeans. St. Louis was at one time known as Mound City by the European Americans because of the numerous surviving prehistoric mounds since lost to urban development. The Mississippian culture left mounds throughout the middle Mississippi and Ohio river valleys, extending into the southeast and the upper river.

The land that became the state of Missouri was part of numerous different territories possessed changing and often indeterminate borders and had many different Native American and European names between the 1600s and statehood. For much of the first half of the 1700s, the west bank of the Mississippi River that would become Missouri was mostly uninhabited, something of a no man's land that kept peace between the Illinois on the east bank of the Mississippi River and to the North, and the Osage and Missouri Indians of the lower Missouri Valley. In the early 1700s, French traders and missionaries explored the whole of the Mississippi Valley, named the region “Louisiana.” Around the same time, a different group of French Canadians who established five villages on the east bank of the Mississippi River placed their settlements in the le pays des Illinois, “the country of the Illinois.” When habitants – settlers of French Canadian descent – began crossing the Mississippi River to establish settlements such as Ste. Genevieve, they continued to place their settlements in the Illinois Country. At the same time, the French settlements on both sides of the Mississippi River were part of the French province of Louisiana. To distinguish the settlements in the Middle Mississippi Valley from French settlements in the lower Mississippi Valley around New Orleans, French officials and inhabitants referred to the Middle Mississippi Valley as La Haute Louisiane, “The High Louisiana,” or “Upper Louisiana.”

The first European settlers were mostly ethnic French Canadians, who created their first settlement in Missouri at present-day Ste. Genevieve, about an hour south of St. Louis. They had migrated about 1750 from the Illinois Country. They came from colonial villages on the east side of the Mississippi River, where soils were becoming exhausted, and there was insufficient river bottom land for the growing population. The early Missouri settlements included many enslaved Africans and Native Americans, and slave labor was central to both commercial agriculture and the fur trade. Sainte-Geneviève became a thriving agricultural center, producing enough surplus wheat, corn and tobacco to ship tons of grain annually downriver to Lower Louisiana for trade. Grain production in the Illinois Country was critical to the survival of Lower Louisiana and especially the city of New Orleans.

St. Louis was founded soon after by French fur traders, Pierre Laclède and stepson Auguste Chouteau from New Orleans in 1764. From 1764 to 1803, European control of the area west of the Mississippi to the northernmost part of the Missouri River basin, called Louisiana, was assumed by the Spanish as part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, due to Treaty of Fontainebleau[30] (in order to have Spain join with France in the war against England). The arrival of the Spanish in St. Louis was in September 1767.

St. Louis became the center of a regional fur trade with Native American tribes that extended up the Missouri and Mississippi rivers, which dominated the regional economy for decades. Trading partners of major firms shipped their furs from St. Louis by river down to New Orleans for export to Europe. They provided a variety of goods to traders for sale and trade with their Native American clients. The fur trade and associated businesses made St. Louis an early financial center and provided the wealth for some to build fine houses and import luxury items. Its location near the confluence of the Illinois River meant it also handled produce from the agricultural areas. River traffic and trade along the Mississippi were integral to the state's economy. As the area's first major city, St. Louis expanded greatly after the invention of the steamboat and the increased river trade.

19th century

Napoleon Bonaparte had gained Louisiana for French ownership from Spain in 1800 under the Treaty of San Ildefonso after it had been a Spanish colony since 1762. But the treaty was kept secret. Louisiana remained nominally under Spanish control until a transfer of power to France on November 30, 1803, just three weeks before the cession to the United States.

Part of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase by the United States, Missouri earned the nickname Gateway to the West because it served as a significant departure point for expeditions and settlers heading to the West during the 19th century. St. Charles, just west of St. Louis, was the starting point and the return destination of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which ascended the Missouri River in 1804, to explore the western lands to the Pacific Ocean. St. Louis was a major supply point for decades, for parties of settlers heading west.

As many of the early settlers in western Missouri migrated from the Upper South, they brought enslaved African Americans as agricultural laborers, and they desired to continue their culture and the institution of slavery. They settled predominantly in 17 counties along the Missouri River, in an area of flatlands that enabled plantation agriculture and became known as "Little Dixie."

The state was rocked by the 1811–12 New Madrid earthquakes. Casualties were few due to the sparse population.

Admission as a state in 1821

In 1821, the former Missouri Territory was admitted as a slave state, under the Missouri Compromise, and with a temporary state capital in St. Charles. In 1826, the capital was shifted to its current, permanent location of Jefferson City, also on the Missouri River.

Originally the state's western border was a straight line, defined as the meridian passing through the Kawsmouth,[31] the point where the Kansas River enters the Missouri River. The river has moved since this designation. This line is known as the Osage Boundary.[32] In 1836 the Platte Purchase was added to the northwest corner of the state after purchase of the land from the native tribes, making the Missouri River the border north of the Kansas River. This addition increased the land area of what was already the largest state in the Union at the time (about 66,500 square miles (172,000 km2) to Virginia's 65,000 square miles, which then included West Virginia).[33]

In the early 1830s, Mormon migrants from northern states and Canada began settling near Independence and areas just north of there. Conflicts over religion and slavery arose between the 'old settlers' (mainly from the South) and the Mormons (mainly from the North). The Mormon War erupted in 1838. By 1839, with the help of an "Extermination Order" by Governor Lilburn Boggs, the old settlers forcibly expelled the Mormons from Missouri and confiscated their lands.

Conflicts over slavery exacerbated border tensions among the states and territories. From 1838 to 1839, a border dispute with Iowa over the so-called Honey Lands resulted in both states' calling-up of militias along the border.

With increasing migration, from the 1830s to the 1860s, Missouri's population almost doubled with every decade. Most newcomers were American-born, but many Irish and German immigrants arrived in the late 1840s and 1850s. As a majority were Catholic, they set up their own religious institutions in the state, which had been mostly Protestant. Many settled in cities, creating a regional and then state network of Catholic churches and schools. 19th-century German immigrants created the wine industry along the Missouri River and the beer industry in St. Louis.

While many German immigrants were strongly anti-slavery,[34][35] many Irish immigrants living in cities were pro-slavery, fearing that liberating African-American slaves would create a glut of unskilled labor, driving wages down.[35]

Most Missouri farmers practiced subsistence farming before the American Civil War. The majority of those who held slaves had fewer than five each. Planters, defined by some historians as those holding 20 slaves or more, were concentrated in the counties known as "Little Dixie," in the central part of the state along the Missouri River. The tensions over slavery chiefly had to do with the future of the state and nation. In 1860, enslaved African Americans made up less than 10% of the state's population of 1,182,012.[36] In order to control the flooding of farmland and low-lying villages along the Mississippi, the state had completed construction of 140 miles (230 km) of levees along the river by 1860.[37]

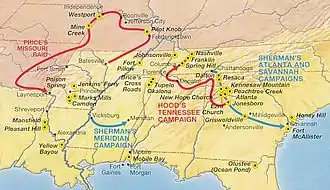

American Civil War

After the secession of Southern states began in 1861, the Missouri legislature called for the election of a special convention on secession. This convention voted against succession, but also qualified their support of the Union. In the aftermath of Battle of Fort Sumter Pro-Southern Governor Claiborne F. Jackson ordered the mobilization of several hundred members of the state militia who had gathered in a camp in St. Louis for training. In secret, he also requested Confederate arms and artillery to help take the St. Louis Arsenal. Alarmed at this action, and discovering the Confederate aid, General Nathaniel Lyon struck first, encircling the camp and forcing the state troops to surrender. Lyon directed his soldiers, largely non-English-speaking German immigrants, to march the prisoners through the streets, and this lead to riot by pro-secession citizens. While it is disputed how it started, this riot lead to violence and Union soldiers killed by St. Louis civilians. The event as a whole, is called the Camp Jackson Affair.

These events sharpened the divisions within the state. Governor Jackson appointed Sterling Price, president of the convention on secession, as head of the new Missouri State Guard. In the face of Union General Lyon's rapid advance through the state, Jackson and Price were forced to flee the capital of Jefferson City on June 14, 1861. In Neosho, Missouri, Jackson called the state legislature into session to call for secession. However, the elected legislative body was split between pro-Union and pro-Confederate. As such, few of the pro-unionist attended the session called in Neosho, and the ordinance of secession was quickly adopted. The Confederacy recognized Missouri secession on October 30, 1861.

With the elected governor absent from the capital and the legislators largely dispersed, the state convention was reassembled with most of its members present, save twenty who fled south with Jackson's forces. The convention declared all offices vacant and installed Hamilton Gamble as the new governor of Missouri. President Lincoln's administration immediately recognized Gamble's government as the legal Missouri government. The federal government's decision enabled raising pro-Union militia forces for service within the state and volunteer regiments for the Union Army.

Fighting ensued between Union forces and a combined army of General Price's Missouri State Guard and Confederate troops from Arkansas and Texas under General Ben McCulloch. After winning victories at the battle of Wilson's Creek and the siege of Lexington, Missouri and suffering losses elsewhere, the Confederate forces retreated to Arkansas and later Marshall, Texas, in the face of a largely reinforced Union Army.

Though regular Confederate troops staged some large-scale raids into Missouri, the fighting in the state for the next three years consisted chiefly of guerrilla warfare. "Citizen soldiers" or insurgents such as Captain William Quantrill, Frank and Jesse James, the Younger brothers, and William T. Anderson made use of quick, small-unit tactics. Pioneered by the Missouri Partisan Rangers, such insurgencies also arose in portions of the Confederacy occupied by the Union during the Civil War. Historians have portrayed stories of the James brothers' outlaw years as an American "Robin Hood" myth.[38] The vigilante activities of the Bald Knobbers of the Ozarks in the 1880s were an unofficial continuation of insurgent mentality long after the official end of the war, and they are a favorite theme in Branson's self-image.[39]

20th century

The Progressive Era (1890s to 1920s) saw numerous prominent leaders from Missouri trying to end corruption and modernize politics, government, and society. Joseph "Holy Joe" Folk was a key leader who made a strong appeal to the middle class and rural evangelical Protestants. Folk was elected governor as a progressive reformer and Democrat in the 1904 election. He promoted what he called "the Missouri Idea," the concept of Missouri as a leader in public morality through popular control of law and strict enforcement. He successfully conducted antitrust prosecutions, ended free railroad passes for state officials, extended bribery statutes, improved election laws, required formal registration for lobbyists, made racetrack gambling illegal and enforced the Sunday-closing law. He helped enact Progressive legislation, including an initiative and referendum provision, regulation of elections, education, employment and child labor, railroads, food, business, and public utilities. Several efficiency-oriented examiner boards and commissions were established during Folk's administration, including many agricultural boards and the Missouri library commission.[40]

Between the Civil War and the end of World War II, Missouri transitioned from a rural economy to a hybrid industrial-service-agricultural economy as the Midwest rapidly industrialized. The expansion of railroads to the West transformed Kansas City into a major transportation hub within the nation. The growth of the Texas cattle industry along with this increased rail infrastructure and the invention of the refrigerated boxcar also made Kansas City a major meatpacking center, as large cattle drives from Texas brought herds of cattle to Dodge City and other Kansas towns. There, the cattle were loaded onto trains destined for Kansas City, where they were butchered and distributed to the eastern markets. The first half of the 20th century was the height of Kansas City's prominence, and its downtown became a showcase for stylish Art Deco skyscrapers as construction boomed.

In 1930, there was a diphtheria epidemic in the area around Springfield, which killed approximately 100 people. Serum was rushed to the area, and medical personnel stopped the epidemic.

During the mid-1950s and 1960s, St. Louis and Kansas City suffered deindustrialization and loss of jobs in railroads and manufacturing, as did other Midwestern industrial cities. In 1956 St. Charles claims to be the site of the first interstate highway project.[41] Such highway construction made it easy for middle-class residents to leave the city for newer housing developed in the suburbs, often former farmland where land was available at lower prices. These major cities have gone through decades of readjustment to develop different economies and adjust to demographic changes. Suburban areas have developed separate job markets, both in knowledge industries and services, such as major retail malls.

21st century

In 2014, Missouri received national attention for the protests and riots that followed the shooting of Michael Brown by a police officer of Ferguson,[42][43][44] which led Governor Jay Nixon to call out the Missouri National Guard.[45][46] A grand jury declined to indict the officer, and the U.S. Department of Justice concluded, after careful investigation, that the police officer legitimately feared for his safety.[47] However, in a separate investigation, the Department of Justice also found that the Ferguson Police Department and the City of Ferguson relied on unconstitutional practices in order to balance the city's budget through racially motivated excessive fines and punishments,[48] that the Ferguson police "had used excessive and dangerous force and had disproportionately targeted blacks,"[49] and that the municipal court "emphasized revenue over public safety, leading to routine breaches of citizens' constitutional guarantees of due process and equal protection under the law."[50]

A series of student protests at the University of Missouri against what the protesters viewed as poor response by the administration to racist incidents on campus began in September 2015.[51][52]

On June 7, 2017, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People issued a warning to prospective African-American travelers to Missouri. This is the first NAACP warning ever covering an entire state.[53][54] According to a 2018 report by the Missouri Attorney General's office, for the past 18 years, "African Americans, Hispanics and other people of color are disproportionately affected by stops, searches and arrests."[55] The same report found that the biggest discrepancy was in 2017, when "black motorists were 85% more likely to be pulled over in traffic stops".[56]

In 2018 the USDA announced its plans to relocate Economic Research Service (ERS) and National Institute of Food & Agriculture (NIFA) to Kansas City. They have since decided on a specific location in downtown Kansas City, Missouri.[57] With the addition of the KC Streetcar project and construction of the Sprint Center Arena, the downtown area in KC has attracted investment in new offices, hotels, and residential complexes. Both Kansas City and St. Louis are undergoing a rebirth in their downtown areas with the addition of the new Power & Light (KC) and Ballpark Village (STL) districts and the renovation of existing historical buildings in each downtown area.[58] The 2019 announcement of an MLS expansion team in St. Louis is driving even more development in the downtown west area of St. Louis.[59]

Geography

Missouri borders eight different states, a figure equaled only by its neighbor, Tennessee. Missouri is bounded by Iowa on the north; by Illinois, Kentucky, and Tennessee across the Mississippi River on the east; on the south by Arkansas; and by Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska (the last across the Missouri River) on the west. Whereas the northern and southern boundaries are straight lines, the Missouri Bootheel extends south between the St. Francis and the Mississippi rivers. The two largest rivers are the Mississippi (which defines the eastern boundary of the state) and the Missouri River (which flows from west to east through the state), essentially connecting the two largest metros of Kansas City and St. Louis.

Although today it is usually considered part of the Midwest,[60] Missouri was historically seen by many as a border state, chiefly because of the settlement of migrants from the South and its status as a slave state before the Civil War, balanced by the influence of St. Louis. The counties that made up "Little Dixie" were those along the Missouri River in the center of the state, settled by Southern migrants who held the greatest concentration of slaves.

In 2005, Missouri received 16,695,000 visitors to its national parks and other recreational areas totaling 101,000 acres (410 km2), giving it $7.41 million in annual revenues, 26.6% of its operating expenditures.[61]

Topography

North of, and in some cases just south of, the Missouri River lie the Northern Plains that stretch into Iowa, Nebraska, and Kansas. Here, rolling hills remain from the glaciation that once extended from the Canadian Shield to the Missouri River. Missouri has many large river bluffs along the Mississippi, Missouri, and Meramec Rivers. Southern Missouri rises to the Ozark Mountains, a dissected plateau surrounding the Precambrian igneous St. Francois Mountains. This region also hosts karst topography characterized by high limestone content with the formation of sinkholes and caves.[62]

The southeastern part of the state is known as the Missouri Bootheel region, which is part of the Mississippi Alluvial Plain or Mississippi embayment. This region is the lowest, flattest, warmest, and wettest part of the state. It is also among the poorest, as the economy there is mostly agricultural.[63] It is also the most fertile, with cotton and rice crops predominant. The Bootheel was the epicenter of the four New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811 and 1812.

Climate

Missouri generally has a humid continental climate with cool, sometimes cold, winters and hot, humid, and wet summers. In the southern part of the state, particularly in the Bootheel, the climate becomes humid subtropical. Located in the interior United States, Missouri often experiences extreme temperatures. Without high mountains or oceans nearby to moderate temperature, its climate is alternately influenced by air from the cold Arctic and the hot and humid Gulf of Mexico. Missouri's highest recorded temperature is 118 °F (48 °C) at Warsaw and Union on July 14, 1954, while the lowest recorded temperature is −40 °F (−40 °C) also at Warsaw on February 13, 1905.

Located in Tornado Alley, Missouri also receives extreme weather in the form of severe thunderstorms and tornadoes. On May 22, 2011, a massive EF-5 tornado killed 158 people and destroyed roughly one-third of the city of Joplin. The tornado caused an estimated $1–3 billion in damages, killed 159 people and injured more than a thousand. It was the first EF5 to hit the state since 1957 and the deadliest in the U.S. since 1947, making it the seventh deadliest tornado in American history and 27th deadliest in the world. St. Louis and its suburbs also have a history of experiencing particularly severe tornadoes, the most recent one of note being an EF4 that damaged Lambert-St. Louis International Airport on April 22, 2011. One of the worst tornadoes in American history struck St. Louis on May 27, 1896, killing at least 255 people and causing $10 million in damage (equivalent to $3.9 billion in 2009 or $4.93 billion in today's dollars).

| Monthly normal high and low temperatures for various Missouri cities in °F (°C). | |||||||||||||||

| City | Avg. | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Columbia | High | 37 (3) |

44 (7) |

55 (13) |

66 (19) |

75 (24) |

84 (29) |

89 (32) |

87 (31) |

79 (26) |

68 (20) |

53 (12) |

42 (6) |

65.0 (18.3) |

|

| Columbia | Low | 18 (−8) |

23 (−5) |

33 (1) |

43 (6) |

53 (12) |

62 (17) |

66 (19) |

64 (18) |

55 (13) |

44 (7) |

33 (1) |

22 (−6) |

43.0 (6.1) |

|

| Kansas City | High | 36 (2) |

43 (6) |

54 (12) |

65 (18) |

75 (24) |

84 (29) |

89 (32) |

87 (31) |

79 (26) |

68 (20) |

52 (11) |

40 (4) |

64.4 (18.0) |

|

| Kansas City | Low | 18 (−8) |

23 (−5) |

33 (1) |

44 (7) |

54 (12) |

63 (17) |

68 (20) |

66 (19) |

57 (14) |

46 (8) |

33 (1) |

22 (−6) |

44.0 (6.7) |

|

| Springfield | High | 42 (6) |

48 (9) |

58 (14) |

68 (20) |

76 (24) |

85 (29) |

90 (32) |

90 (32) |

81 (27) |

71 (22) |

56 (13) |

46 (8) |

67.6 (19.8) |

|

| Springfield | Low | 22 (−6) |

26 (−3) |

35 (2) |

44 (7) |

53 (12) |

62 (17) |

67 (19) |

66 (19) |

57 (14) |

46 (8) |

35 (2) |

26 (−3) |

45.0 (7.2) |

|

| St. Louis | High | 40 (4) |

45 (7) |

56 (13) |

67 (19) |

76 (24) |

85 (29) |

89 (32) |

88 (31) |

80 (27) |

69 (21) |

56 (13) |

43 (6) |

66.2 (19.0) |

|

| St. Louis | Low | 24 (−4) |

28 (−2) |

37 (3) |

47 (8) |

57 (14) |

67 (19) |

71 (22) |

69 (21) |

61 (16) |

49 (9) |

38 (3) |

27 (−3) |

48.0 (8.9) |

|

| Source:[64] | |||||||||||||||

.jpg.webp)

Wildlife

Missouri is home to diverse flora and fauna, including several endemic species.[65] There is a large amount of fresh water present due to the Mississippi River, Missouri River, Table Rock Lake and Lake of the Ozarks, with numerous smaller tributary rivers, streams, and lakes. North of the Missouri River, the state is primarily rolling hills of the Great Plains, whereas south of the Missouri River, the state is dominated by the Oak-Hickory Central U.S. hardwood forest.

Forests

Recreational and commercial uses of public forests, including grazing, logging, and mining, increased after World War II. Fishermen, hikers, campers, and others started lobbying to protect forest areas with a "wilderness character." During the 1930s and 1940s Aldo Leopold, Arthur Carhart and Bob Marshall developed a "wilderness" policy for the Forest Service. Their efforts bore fruit with the Wilderness Act of 1964, which designated wilderness areas "where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by men, where man himself is a visitor and does not remain." This included second growth public forests like the Mark Twain National Forest.[66]

Demographics

.png.webp)

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1810 | 19,783 | — | |

| 1820 | 66,586 | 236.6% | |

| 1830 | 140,455 | 110.9% | |

| 1840 | 383,702 | 173.2% | |

| 1850 | 682,044 | 77.8% | |

| 1860 | 1,182,012 | 73.3% | |

| 1870 | 1,721,295 | 45.6% | |

| 1880 | 2,168,380 | 26.0% | |

| 1890 | 2,679,185 | 23.6% | |

| 1900 | 3,106,665 | 16.0% | |

| 1910 | 3,293,335 | 6.0% | |

| 1920 | 3,404,055 | 3.4% | |

| 1930 | 3,629,367 | 6.6% | |

| 1940 | 3,784,664 | 4.3% | |

| 1950 | 3,954,653 | 4.5% | |

| 1960 | 4,319,813 | 9.2% | |

| 1970 | 4,676,501 | 8.3% | |

| 1980 | 4,916,686 | 5.1% | |

| 1990 | 5,117,073 | 4.1% | |

| 2000 | 5,595,211 | 9.3% | |

| 2010 | 5,988,927 | 7.0% | |

| 2020 | 6,154,913 | 2.8% | |

| Source: 1910–2020[67] | |||

The United States Census Bureau estimates that the population of Missouri was 6,137,428 on July 1, 2019, a 2.48% increase since the 2010 United States census.[68]

Missouri had a population of 5,988,927, according to the 2010 census; an increase of 137,525 (2.3 percent) since the year 2010. From 2010 to 2018, this includes a natural increase of 137,564 people since the last census (480,763 births less 343,199 deaths) and an increase of 88,088 people due to net migration into the state. Immigration from outside the United States resulted in a net increase of 50,450 people, and migration within the country produced a net increase of 37,638 people. More than half of Missourians (3,294,936 people, or 55.0%) live within the state's two largest metropolitan areas—St. Louis and Kansas City. The state's population density 86.9 in 2009, is also closer to the national average (86.8 in 2009) than any other state.

| Racial composition | 1990[69] | 2000[70] | 2010[71] |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 87.7% | 84.9% | 82.8% |

| Black | 10.7% | 11.3% | 11.6% |

| Asian | 0.8% | 1.1% | 1.6% |

| Native | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.5% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander | – | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Other race | 0.4% | 0.8% | 1.3% |

| Two or more races | – | 1.5% | 2.1% |

The U.S. census of 2010 found that the population center of the United States is in Texas County, while the 2000 census found the mean population center to be in Phelps County. The center of population of Missouri is in Osage County, in the city of Westphalia.[72]

In 2004, the population included 194,000 foreign-born (3.4 percent of the state population).

The five largest ancestry groups in Missouri are: German (27.4 percent), Irish (14.8 percent), English (10.2 percent), American (8.5 percent) and French (3.7 percent).

German Americans are an ancestry group present throughout Missouri. African Americans are a substantial part of the population in St. Louis (56.6% of African Americans in the state lived in St. Louis or St. Louis County as of the 2010 census), Kansas City, Boone County and in the southeastern Bootheel and some parts of the Missouri River Valley, where plantation agriculture was once important. Missouri Creoles of French ancestry are concentrated in the Mississippi River Valley south of St. Louis (see Missouri French). Kansas City is home to large and growing immigrant communities from Latin America esp. Mexico and Colombia, Africa (i.e. Sudan, Somalia and Nigeria), and Southeast Asia including China and the Philippines; and Europe like the former Yugoslavia (see Bosnian American). A notable Cherokee Indian population exists in Missouri.

In 2004, 6.6 percent of the state's population was reported as younger than 5, 25.5 percent younger than 18, and 13.5 percent 65 or older. Females were approximately 51.4 percent of the population. 81.3 percent of Missouri residents were high school graduates (more than the national average), and 21.6 percent had a bachelor's degree or higher. 3.4 percent of Missourians were foreign-born, and 5.1 percent reported speaking a language other than English at home.

In 2010, there were 2,349,955 households in Missouri, with 2.45 people per household. The homeownership rate was 70.0 percent, and the median value of an owner-occupied housing unit was $137,700. The median household income for 2010 was $46,262, or $24,724 per capita. There was 14.0 percent (1,018,118) of Missourians living below the poverty line in 2010.

The mean commute time to work was 23.8 minutes.

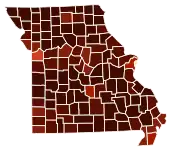

Non-Hispanic White 50–60%60–70%70–80%80–90%90%+Black or African American 40–50%

Birth data

In 2011, 28.1% of Missouri's population younger than age 1 were minorities.[73]

Note: Births in table don't add up, because Hispanics are counted both by their ethnicity and by their race, giving a higher overall number.

| Race | 2013[74] | 2014[75] | 2015[76] | 2016[77] | 2017[78] | 2018[79] | 2019[80] | 2020[81] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White: | 61,097 (81.1%) | 60,968 (80.9%) | 60,913 (81.1%) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| > non-Hispanic White | 57,361 (76.2%) | 57,150 (75.8%) | 57,092 (76.1%) | 55,455 (74.2%) | 53,800 (73.7%) | 53,697 (73.3%) | 52,523 (72.8%) | 50,190 (72.4%) |

| Black | 11,722 (15.6%) | 11,783 (15.6%) | 11,660 (15.5%) | 10,445 (14.0%) | 10,495 (14.4%) | 10,589 (14.4%) | 10,501 (14.6%) | 10,156 (14.6%) |

| Asian | 2,075 (2.8%) | 2,186 (2.9%) | 2,129 (2.8%) | 1,852 (2.5%) | 1,773 (2.4%) | 1,698 (2.3%) | 1,814 (2.5%) | 1,610 (2.3%) |

| Pacific Islander | ... | ... | ... | 199 (0.3%) | 183 (0.3%) | 199 (0.3%) | 228 (0.3%) | 249 (0.3%) |

| American Indian | 402 (0.5%) | 423 (0.6%) | 359 (0.5%) | 156 (0.2%) | 167 (0.2%) | 140 (0.2%) | 145 (0.2%) | 163 (0.2%) |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 3,931 (5.2%) | 3,959 (5.3%) | 4,042 (5.4%) | 4,136 (5.5%) | 4,156 (5.7%) | 4,409 (6.0%) | 4,386 (6.1%) | 4,469 (6.4%) |

| Total Missouri | 75,296 (100%) | 75,360 (100%) | 75,061 (100%) | 74,705 (100%) | 73,034 (100%) | 73,269 (100%) | 72,127 (100%) | 69,285 (100%) |

- Since 2016, data for births of White Hispanic origin are not collected, but included in one Hispanic group; persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race.

Language

The vast majority of people in Missouri speak English. Approximately 5.1% of the population reported speaking a language other than English at home. The Spanish language is spoken in small Latino communities in the St. Louis and Kansas City Metro areas.[82]

Missouri is home to an endangered dialect of the French language known as Missouri French. Speakers of the dialect, who call themselves Créoles, are descendants of the French pioneers who settled the area then known as the Illinois Country beginning in the late 17th century. It developed in isolation from French speakers in Canada and Louisiana, becoming quite distinct from the varieties of Canadian French and Louisiana Creole French. Once widely spoken throughout the area, Missouri French is now nearly extinct, with only a few elderly speakers able to use it.[83][84]

Religion

According to a Pew Research study[85] conducted in 2014, 80% of Missourians identify with a religion. 77% affiliate with Christianity and its various denominations and the other 3% are adherents of non-Christian religions. The remaining 20% have no religion, with 2% specifically identifying as atheists and 3% identifying as agnostics (the other 15% do not identify as "anything in particular").

The religious demographics of Missouri are as follows:

- Christian 77%

- Protestant 58%

- Evangelical Protestant 36%

- Mainline Protestant 16%

- Historically Black Protestant 6%

- Catholic 16%

- Mormon 1%

- Orthodox Christian <1%

- Jehovah's Witness <1%

- Other Christian <1%

- Protestant 58%

- Non-Christian Religions 3%

- Jewish <1%

- Muslim <1%

- Buddhist 1%

- Hindu <1%

- Other World Religions <1%

- Unaffiliated (No religion) 20%

- Atheist 2%

- Agnostic 3%

- Nothing in particular 15%

- Don't know <1%

The largest denominations by number of adherents in 2010 were the Southern Baptist Convention with 749,685; the Roman Catholic Church with 724,315; and the United Methodist Church with 226,409.[86]

Among the other denominations there are approximately 93,000 Mormons in 253 congregations, 25,000 Jewish adherents in 21 synagogues, 12,000 Muslims in 39 masjids, 7,000 Buddhists in 34 temples, 20,000 Hindus in 17 temples, 2,500 Unitarians in nine congregations, 2,000 of the Baháʼí Faith in 17 temples, five Sikh temples, a Zoroastrian temple, a Jain temple and an uncounted number of neopagans.[87]

Several religious organizations have headquarters in Missouri, including the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod, which has its headquarters in Kirkwood, as well as the United Pentecostal Church International in Hazelwood, both outside St. Louis.

Independence, near Kansas City, is the headquarters for the Community of Christ (formerly the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints), the Church of Christ (Temple Lot) and the group Remnant Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. This area and other parts of Missouri are also of significant religious and historical importance to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), which maintains several sites and visitor centers.

Springfield is the headquarters of the Assemblies of God USA and the Baptist Bible Fellowship International. The General Association of General Baptists has its headquarters in Poplar Bluff. The Unity Church is headquartered in Unity Village. Springfield is particularly known as a Christian center in the state[88] and is considered by some to be a "buckle" of the Bible Belt.[89]

Hindu Temple of St. Louis is the largest Hindu Temple in Missouri, serving more than 14,000 Hindus.

Economy

- Total employment in 2016: 2,494,720

- Total Number of employer establishments in 2016: 160,912[91]

The U.S. Department of Commerce's Bureau of Economic Analysis estimated Missouri's 2016 gross state product at $299.1 billion, ranking 22nd among U.S. states.[92] Per capita personal income in 2006 was $32,705,[61] ranking 26th in the nation. Major industries include aerospace, transportation equipment, food processing, chemicals, printing/publishing, electrical equipment, light manufacturing, financial services and beer.

The agriculture products of the state are beef, soybeans, pork, dairy products, hay, corn, poultry, sorghum, cotton, rice, and eggs. Missouri is ranked 6th in the nation for the production of hogs and 7th for cattle. Missouri is ranked in the top five states in the nation for production of soy beans, and it is ranked fourth in the nation for the production of rice. In 2001, there were 108,000 farms, the second-largest number in any state after Texas. Missouri actively promotes its rapidly growing wine industry. According to the Missouri Partnership, Missouri's agriculture industry contributes $33 billion in GDP to Missouri's economy, and generates $88 billion in sales and more than 378,000 jobs.[93]

Missouri has vast quantities of limestone. Other resources mined are lead, coal, and crushed stone. Missouri produces the most lead of all the states. Most of the lead mines are in the central eastern portion of the state. Missouri also ranks first or near first in the production of lime, a key ingredient in Portland cement.

Missouri also has a growing science, agricultural technology, and biotechnology field. Monsanto, formerly one of the largest biotech companies in America, was based in St. Louis until it was acquired by Bayer AG in 2018. It is now part of the Crop Science Division of Bayer Corporation, Bayer's U.S. subsidiary.

Tourism, services, and wholesale/retail trade follow manufacturing in importance—tourism benefits from the many rivers, lakes, caves, parks, etc., throughout the state. In addition to a network of state parks, Missouri is home to Gateway Arch National Park in St. Louis and the Ozark National Scenic Riverways. A much-visited show cave is Meramec Caverns in Stanton.

Missouri is the only state in the Union to have two Federal Reserve Banks: one in Kansas City (serving western Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Colorado, northern New Mexico, and Wyoming) and one in St. Louis (serving eastern Missouri, southern Illinois, southern Indiana, western Kentucky, western Tennessee, northern Mississippi, and all of Arkansas).[94]

The state's seasonally adjusted unemployment rate in April 2017 was 3.9 percent.[95] In 2017, Missouri became a right-to-work state,[96] but in August 2018, Missouri voters rejected a right-to-work law with 67% to 33%.[97][98][99]

Taxation

Personal income is taxed in ten different earning brackets, ranging from 1.5% to 6.0%. Missouri's sales tax rate for most items is 4.225%, with some additional local levies. More than 2,500 Missouri local governments rely on property taxes levied on real property (real estate) and personal property.

Most personal property is exempt, except for motorized vehicles. Exempt real estate includes property owned by governments and property used as nonprofit cemeteries, exclusively for religious worship, for schools and colleges, and purely charitable purposes. There is no inheritance tax and limited Missouri estate tax related to federal estate tax collection.

In 2017, the Tax Foundation rated Missouri as having the 5th-best corporate tax index,[100] and the 15th-best overall tax climate.[100] Missouri's corporate income tax rate is 6.25%; however, 50% of federal income tax payments may be deducted before computing taxable income, leading to an effective rate of 5.2%.[101]

Energy

In 2012, Missouri had roughly 22,000 MW of installed electricity generation capacity.[102] In 2011, 82% of Missouri's electricity was generated by coal.[103] Ten percent was generated from the state's only nuclear power plant,[103] the Callaway Plant in Callaway County, northeast of Jefferson City. Five percent was generated by natural gas.[103] One percent was generated by hydroelectric sources,[103] such as the dams for Truman Lake and Lake of the Ozarks. Missouri has a small but growing amount of wind and solar power—wind capacity increased from 309 MW in 2009 to 459 MW in 2011, while photovoltaics have increased from 0.2 MW to 1.3 MW over the same period.[104][105] As of 2016, Missouri's solar installations had reached 141 MW.[106]

Oil wells in Missouri produced 120,000 barrels of crude oil in fiscal 2012.[107] There are no oil refineries in Missouri.[105][108]

Transportation

Airports

Missouri has two major airport hubs: St. Louis Lambert International Airport and Kansas City International Airport. Southern Missouri has the Springfield–Branson National Airport (SGF) with multiple non-stop destinations.[109] Residents of Mid-Missouri use Columbia Regional Airport (COU) to fly to Chicago (ORD), Dallas (DFW) or Denver (DEN).[110]

Rail

Missouri passenger rail stations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg.webp)

Two of the nation's three busiest rail centers are in Missouri. Kansas City is a major railroad hub for BNSF Railway, Norfolk Southern Railway, Kansas City Southern Railway, and Union Pacific Railroad, and every class 1 railroad serves Missouri. Kansas City is the second-largest freight rail center in the US (but is first in the amount of tonnage handled). Like Kansas City, St. Louis is a major destination for train freight. Springfield remains an operational hub for BNSF Railway.

Amtrak passenger trains serve Kansas City, La Plata, Jefferson City, St. Louis, Lee's Summit, Independence, Warrensburg, Hermann, Washington, Kirkwood, Sedalia, and Poplar Bluff. A proposed high-speed rail route in Missouri as part of the Chicago Hub Network has received $31 million in funding.[111]

The only urban light rail/subway system operating in Missouri is MetroLink, which connects the city of St. Louis with suburbs in Illinois and St. Louis County. It is one of the largest systems (by track mileage) in the United States. The KC Streetcar in downtown Kansas City opened in May 2016.[112]

The Gateway Multimodal Transportation Center in St. Louis is the largest active multi-use transportation center in the state. It is in downtown St. Louis, next to the historic Union Station complex. It serves as a hub center/station for MetroLink, the MetroBus regional bus system, Greyhound, Amtrak, and taxi services.

The proposed Missouri Hyperloop would connect St. Louis, Kansas City, and Columbia, reducing travel times to around a half hour.[113]

Bus

Many cities have regular fixed-route systems, and many rural counties have rural public transit services. Greyhound and Trailways provide inter-city bus service in Missouri. Megabus serves St. Louis, but discontinued service to Columbia and Kansas City in 2015.[114]

Rivers

The Mississippi River and Missouri River are commercially navigable over their entire lengths in Missouri. The Missouri was channelized through dredging and jetties, and the Mississippi was given a series of locks and dams to avoid rocks and deepen the river. St. Louis is a major destination for barge traffic on the Mississippi.

Roads

Following the passage of Amendment 3 in late 2004, the Missouri Department of Transportation (MoDOT) began its Smoother, Safer, Sooner road-building program with a goal of bringing 2,200 miles (3,500 km) of highways up to good condition by December 2007. From 2006 to 2011 traffic deaths have decreased annually from 1,257 in 2005, to 1,096 in 2006, to 992 in 2007, to 960 in 2008, to 878 in 2009, to 821 in 2010, to 786 in 2011.[115]

Law and government

| Missouri Government | |

| Governor of Missouri | Mike Parson (R) |

| Lieutenant Governor of Missouri: | Mike Kehoe (R) |

| Missouri Secretary of State: | Jay Ashcroft (R) |

| Missouri State Auditor: | Nicole Galloway (D) |

| Missouri State Treasurer: | Scott Fitzpatrick (R) |

| Missouri Attorney General: | Eric Schmitt (R) |

| United States Senator: | Josh Hawley (R) |

| United States Senator: | Roy Blunt (R) |

The current Constitution of Missouri, the fourth constitution for the state, was adopted in 1945. It provides for three branches of government: the legislative, judicial, and executive branches. The legislative branch consists of two bodies: the House of Representatives and the Senate. These bodies comprise the Missouri General Assembly.

The House of Representatives has 163 members apportioned based on the last decennial census. The Senate consists of 34 members from districts of approximately equal populations. The judicial department comprises the Supreme Court of Missouri, which has seven judges, the Missouri Court of Appeals (an intermediate appellate court divided into three districts), sitting in Kansas City, St. Louis, and Springfield, and 45 Circuit Courts which function as local trial courts. The executive branch is headed by the Governor of Missouri and includes five other statewide elected offices. Following the death of State Auditor Tom Schweich in 2015, only one of Missouri's statewide elected offices is held by a Democrat: his successor Nicole Galloway.

Harry S Truman (1884–1972), the 33rd President of the United States (Democrat, 1945–1953), was born in Lamar. He was a judge in Jackson County and then represented the state in the United States Senate for ten years, before being elected vice-president in 1944. He lived in Independence after retiring as president in 1953.

In a 2020 study, Missouri was ranked as 48th on the "Cost of Voting Index" with only Texas and Georgia ranking higher.[116]

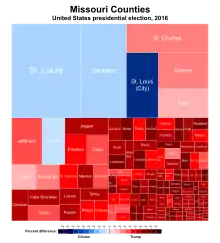

Former status as a political bellwether

Missouri was widely regarded as a bellwether in American politics, often making it a swing state. The state had a longer stretch of supporting the winning presidential candidate than any other state, having voted with the nation in every election from 1904 to 2004 with a single exception: 1956 when Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson of neighboring Illinois lost the election despite carrying Missouri. However, in recent years, areas of the state outside Kansas City, St. Louis, and Columbia have shifted heavily to the right, making Missouri a safe Republican state on the whole. The last Democrat to win the state's electoral votes was Bill Clinton in 1996. It rejected Democrat Barack Obama of neighboring Illinois in both of his successful campaigns in 2008 and 2012. Missouri voted for Mitt Romney by nearly 10% in 2012 and voted for Donald Trump by over 18% in 2016 and 15% in 2020.

On October 24, 2012, there were 4,190,936 registered voters.[117] At the state level, both Democratic Senator Claire McCaskill and Democratic Governor Jay Nixon were re-elected.

On November 3, 2020, there were 4,318,758 registered voters, with 3,026,028 voting (70.1%).[118] By this time, the state had favored more Republican candidates for federal offices. The offices held by Democratic party officials a decade before were subsequently held by Republican Senator Josh Hawley and Republican Governor Mike Parson.

Missouri's accuracy rate for the last 29 presidential elections is now 89.66%. This percentage is on par with that of Ohio, which has voted for the winner of every presidential election since 1896, except in 1944, 1960 and 2020, with no Republican ever winning the White House without the state. Nevada has been carried by the winner of every presidential election since 1912, with only two exceptions: 1976 and 2016. New Mexico has voted for the winner of every presidential election since its statehood in 1912, except in 1976, 2000 and 2016.

| Year | Republican / Whig | Democratic | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 1,718,736 | 56.71% | 1,253,014 | 41.34% | 58,998 | 1.95% |

| 2016 | 1,594,511 | 56.38% | 1,071,068 | 37.87% | 162,687 | 5.75% |

| 2012 | 1,482,440 | 53.64% | 1,223,796 | 44.28% | 57,453 | 2.08% |

| 2008 | 1,445,814 | 49.36% | 1,441,911 | 49.23% | 41,386 | 1.41% |

| 2004 | 1,455,713 | 53.30% | 1,259,171 | 46.10% | 16,480 | 0.60% |

| 2000 | 1,189,924 | 50.42% | 1,111,138 | 47.08% | 58,830 | 2.49% |

| 1996 | 890,016 | 41.24% | 1,025,935 | 47.54% | 242,114 | 11.22% |

| 1992 | 811,159 | 33.92% | 1,053,873 | 44.07% | 526,533 | 22.02% |

| 1988 | 1,084,953 | 51.83% | 1,001,619 | 47.85% | 6,656 | 0.32% |

| 1984 | 1,274,188 | 60.02% | 848,583 | 39.98% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1980 | 1,074,181 | 51.16% | 931,182 | 44.35% | 94,461 | 4.50% |

| 1976 | 927,443 | 47.47% | 998,387 | 51.10% | 27,770 | 1.42% |

| 1972 | 1,154,058 | 62.29% | 698,531 | 37.71% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1968 | 811,932 | 44.87% | 791,444 | 43.74% | 206,126 | 11.39% |

| 1964 | 653,535 | 35.95% | 1,164,344 | 64.05% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 962,221 | 49.74% | 972,201 | 50.26% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1956 | 914,289 | 49.89% | 918,273 | 50.11% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1952 | 959,429 | 50.71% | 929,830 | 49.14% | 2,803 | 0.15% |

| 1948 | 655,039 | 41.49% | 917,315 | 58.11% | 6,274 | 0.40% |

| 1944 | 761,524 | 48.43% | 807,804 | 51.37% | 3,146 | 0.20% |

| 1940 | 871,009 | 47.50% | 958,476 | 52.27% | 4,244 | 0.23% |

| 1936 | 697,891 | 38.16% | 1,111,043 | 60.76% | 19,701 | 1.08% |

| 1932 | 564,713 | 35.08% | 1,025,406 | 63.69% | 19,775 | 1.23% |

| 1928 | 834,080 | 55.58% | 662,562 | 44.15% | 4,079 | 0.27% |

| 1924 | 648,486 | 49.58% | 572,753 | 43.79% | 86,719 | 6.63% |

| 1920 | 727,162 | 54.56% | 574,799 | 43.13% | 30,839 | 2.31% |

| 1916 | 369,339 | 46.94% | 398,032 | 50.59% | 19,398 | 2.47% |

| 1912 | 207,821 | 29.75% | 330,746 | 47.35% | 159,999 | 22.90% |

| 1908 | 347,203 | 48.50% | 346,574 | 48.41% | 22,150 | 3.09% |

| 1904 | 321,449 | 49.93% | 296,312 | 46.02% | 26,100 | 4.05% |

| 1900 | 314,092 | 45.94% | 351,922 | 51.48% | 17,642 | 2.58% |

| 1896 | 304,940 | 45.25% | 363,667 | 53.96% | 5,299 | 0.79% |

| 1892 | 227,646 | 42.03% | 268,400 | 49.56% | 45,537 | 8.41% |

| 1888 | 236,252 | 45.31% | 261,943 | 50.24% | 23,165 | 4.44% |

| 1884 | 203,081 | 46.02% | 236,023 | 53.49% | 2,164 | 0.49% |

| 1880 | 153,647 | 38.67% | 208,600 | 52.51% | 35,042 | 8.82% |

| 1876 | 145,027 | 41.36% | 202,086 | 57.64% | 3,497 | 1.00% |

| 1872 | 119,196 | 43.65% | 151,434 | 55.46% | 2,429 | 0.89% |

| 1868 | 86,860 | 56.96% | 65,628 | 43.04% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1864 | 72,750 | 69.72% | 31,596 | 30.28% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1860 | 17,028 | 10.28% | 58,801 | 35.52% | 89,734 | 54.20% |

| 1856 | 0 | 0.00% | 57,964 | 54.43% | 48,522 | 45.57% |

| 1852 | 29,984 | 43.58% | 38,817 | 56.42% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1848 | 32,671 | 44.91% | 40,077 | 55.09% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1844 | 31,200 | 43.02% | 41,322 | 56.98% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1840 | 22,954 | 43.37% | 29,969 | 56.63% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1836 | 7,337 | 40.02% | 10,995 | 59.98% | 0 | 0.00% |

Laissez-faire alcohol and tobacco laws

Missouri has been known for its population's generally "stalwart, conservative, noncredulous" attitude toward regulatory regimes, which is one of the origins of the state's unofficial nickname, the "Show-Me State".[120] As a result, and combined with the fact that Missouri is one of America's leading alcohol states, regulation of alcohol and tobacco in Missouri is among the most laissez-faire in America. For 2013, the annual "Freedom in the 50 States" study prepared by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University ranked Missouri as #3 in America for alcohol freedom and #1 for tobacco freedom (#7 for freedom overall).[121] The study notes that Missouri's "alcohol regime is one of the least restrictive in the United States, with no blue laws and taxes well below average", and that "Missouri ranks best in the nation on tobacco freedom".[121]

Missouri law makes it "an improper employment practice" for an employer to refuse to hire, to fire, or otherwise to disadvantage any person because that person lawfully uses alcohol and/or tobacco products outside of work.[122]

With a large German immigrant population and the development of a brewing industry, Missouri always has had among the most permissive alcohol laws in the United States. It has never enacted statewide prohibition. Missouri voters rejected prohibition in three separate referendums in 1910, 1912, and 1918. Alcohol regulation did not begin in Missouri until 1934.

Today, alcohol laws are controlled by the state government, and local jurisdictions are prohibited from going beyond those state laws. Missouri has no statewide open container law or prohibition on drinking in public, no alcohol-related blue laws, no local option, no precise locations for selling liquor by the package (allowing even drug stores and gas stations to sell any kind of liquor), and no differentiation of laws based on alcohol percentage. State law protects persons from arrest or criminal penalty for public intoxication.[123]

Missouri law expressly prohibits any jurisdiction from going dry.[124] Missouri law also expressly allows parents and guardians to serve alcohol to their children.[125] The Power & Light District in Kansas City is one of the few places in the United States where a state law explicitly allows persons over 21 to possess and consume open containers of alcohol in the street (as long as the beverage is in a plastic cup).[126]

As for tobacco (as of July 2016), Missouri has the lowest cigarette excise taxes in the United States, at 17 cents per pack,[127] and the state electorate voted in 2002, 2006, 2012, and twice in 2016 to keep it that way.[128][129] In 2007, Forbes named Missouri's largest metropolitan area, St. Louis, America's "best city for smokers".[130][131]

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in 2008 Missouri had the fourth highest percentage of adult smokers among U.S. states, at 24.5%.[132] Although federal law prohibits the sale of tobacco to persons under 21, tobacco products can be distributed to persons under 21 by family members on private property.[133]

No statewide smoking ban ever has been seriously entertained before the Missouri General Assembly, and in October 2008, a statewide survey by the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services found that only 27.5% of Missourians support a statewide ban on smoking in all bars and restaurants.[134] Missouri state law permits restaurants seating less than 50 people, bars, bowling alleys, and billiard parlors to decide their own smoking policies, without limitation.[135]

Cannabis laws

In 2014, a Republican-led legislature and Democratic governor Jay Nixon enacted a series of laws to partially decriminalize possession of cannabis by making first-time possession of up to 10 grams no longer punishable with jail time and legalizing CBD oil. In November 2018, 66% of voters approved a constitutional amendment that established a right to medical marijuana and a system for licensing, regulating, and taxing medical marijuana.

Counties

Missouri has 114 counties and one independent city, St. Louis, which is Missouri's most densely populated—5,140 people per square mile.

The largest counties by population are St. Louis (996,726), Jackson (698,895), and St. Charles (395,504). Worth County is the smallest (2,057).

The largest counties by size are Texas (1,179 square miles) and Shannon (1,004). Worth County is the smallest (266).

Cities and towns

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kansas City  St. Louis |

1 | Kansas City | Jackson, Clay, Platte, and Cass | 508,090 |  Springfield  Columbia | ||||

| 2 | St. Louis | Independent city | 301,578 | ||||||

| 3 | Springfield | Greene | 169,176 | ||||||

| 4 | Columbia | Boone | 126,254 | ||||||

| 5 | Independence | Jackson | 123,011 | ||||||

| 6 | Lee's Summit | Jackson | 101,108 | ||||||

| 7 | O'Fallon | St. Charles | 91,316 | ||||||

| 8 | St. Joseph | Buchanan | 72,473 | ||||||

| 9 | St. Charles | St. Charles | 71,028 | ||||||

| 10 | St. Peters | St. Charles | 58,212 | ||||||

Jefferson City is the capital city of Missouri, while the state's five largest cities are Kansas City, St. Louis, Springfield, Columbia, and Independence.[136]

St. Louis is the principal city of the largest metropolitan area in Missouri, composed of 17 counties and the independent city of St. Louis; eight of its counties are in Illinois. As of 2019, St. Louis was the 21st-largest metropolitan area in the nation with 2.91 million people. However, if ranked using Combined Statistical Area, it is 20th-largest with 2.91 million people in 2019. Some of the major cities making up the St. Louis metro area in Missouri are O'Fallon, St. Charles, St. Peters, Florissant, Chesterfield, Wentzville, Wildwood, University City, and Ballwin.

Kansas City is Missouri's largest city and the principal city of the fourteen-county Kansas City Metropolitan Statistical Area, including five counties in the state of Kansas. As of 2019, it was the 31st-largest metropolitan area in the U.S., with 2.16 million people. In the Combined Statistical Area in 2019, it ranked 27th with 2.51 million. Some of the other major cities comprising the Kansas City metro area in Missouri include Independence, Lee's Summit, Blue Springs, Liberty, Raytown, Gladstone, and Grandview.

Springfield is Missouri's third-largest city and the principal city of the Springfield-Branson Metropolitan Area, which has a population of 549,423 and includes seven counties in southwestern Missouri. Branson is a major tourist attraction in the Ozarks in southwest Missouri. Some of the other major cities comprising the Springfield-Branson metro area include Nixa, Ozark, and Republic.

Education

Missouri State Board of Education

The Missouri State Board of Education has general authority over all public education in the state of Missouri. It is made up of eight citizens appointed by the governor and confirmed by the Missouri Senate.

Primary and secondary schools

Education is compulsory from ages seven to seventeen. It is required that any parent, guardian, or another person with custody of a child between the ages of seven and seventeen, the compulsory attendance age for the district, must ensure the child is enrolled in and regularly attends public, private, parochial school, home school or a combination of schools for the full term of the school year. Compulsory attendance also ends when children complete sixteen credits in high school.

Children in Missouri between the ages of five and seven are not required to be enrolled in school. However, if they are enrolled in a public school, their parent, guardian, or custodian must ensure they regularly attend.

Missouri schools are commonly but not exclusively divided into three tiers of primary and secondary education: elementary school, middle school or junior high school and high school. The public school system includes kindergarten to 12th grade. District territories are often complex in structure. In some cases, elementary, middle, and junior high schools of a single district feed into high schools in another district. As another example, special education and related services for students in the twenty-two school districts of St. Louis County are provided by staff employeed by a special school sistrict, a local education agency that serves students county-wide. High school athletics and competitions are governed by the Missouri State High School Activities Association (MSHSAA).

Homeschooling is legal in Missouri and is an option to meet the compulsory education requirement. It is neither monitored nor regulated by the state's Department of Elementary and Secondary Education.[137]

Another gifted school is the Missouri Academy of Science, Mathematics and Computing, which is at the Northwest Missouri State University.

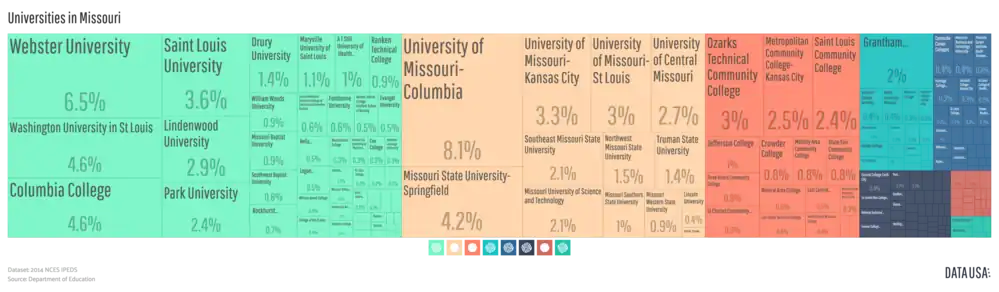

Colleges and universities

The University of Missouri System is Missouri's statewide public university system. The flagship institution and largest university in the state is the University of Missouri in Columbia. The others in the system are University of Missouri–Kansas City, University of Missouri–St. Louis, and Missouri University of Science and Technology in Rolla.

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the state established a series of normal schools in each region of the state, originally named after the geographic districts: Northeast Missouri State University (now Truman State University) (1867), Central Missouri State University (now the University of Central Missouri) (1871), Southeast Missouri State University (1873), Southwest Missouri State University (now Missouri State University) (1905), Northwest Missouri State University (1905), Missouri Western State University (1915), Maryville University (1872) and Missouri Southern State University (1937). Lincoln University and Harris–Stowe State University were established in the mid-nineteenth century and are historically black colleges and universities.

Among private institutions Washington University in St. Louis and Saint Louis University are two top ranked schools in the US.[138] There are numerous junior colleges, trade schools, church universities and other private universities in the state. A.T. Still University was the first osteopathic medical school in the world. Hannibal–LaGrange University in Hannibal, Missouri, was one of the first colleges west of the Mississippi (founded 1858 in LaGrange, Missouri, and moved to Hannibal in 1928).[139]

The state funds a $2000, renewable merit-based scholarship, Bright Flight, given to the top three percent of Missouri high school graduates who attend a university in-state.

The 19th-century border wars between Missouri and Kansas have continued as a sports rivalry between the University of Missouri and University of Kansas. The rivalry was chiefly expressed through football and basketball games between the two universities, but since Missouri left the Big 12 Conference in 2012, the teams no longer regularly play one another. It was the oldest college rivalry west of the Mississippi River and the second-oldest in the nation. Each year when the universities met to play, the game was coined the "Border War." Following the game, an exchange occurred where the winner took a historic Indian War Drum, which had been passed back and forth for decades. Though Missouri and Kansas no longer have an annual game after the University of Missouri moved to the Southeastern Conference, rivalry still exists between them.

Culture

Music

Many well-known musicians were born or have lived in Missouri. These include guitarist and rock pioneer Chuck Berry, singer and actress Josephine Baker, "Queen of Rock" Tina Turner, pop singer-songwriter Sheryl Crow, Michael McDonald of the Doobie Brothers, and rappers Nelly, Chingy and Akon, all of whom are either current or former residents of St. Louis.

Country singers from Missouri include Perryville native Chris Janson, New Franklin native Sara Evans, Cantwell native Ferlin Husky, West Plains native Porter Wagoner, Tyler Farr of Garden City, and Mora native Leroy Van Dyke, along with bluegrass musician Rhonda Vincent, a native of Greentop. Rapper Eminem was born in St. Joseph and also lived in Savannah and Kansas City. Ragtime composer Scott Joplin lived in St. Louis and Sedalia. Jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker lived in Kansas City. Rock and Roll singer Steve Walsh of the group Kansas was born in St. Louis and grew up in St. Joseph.

The Kansas City Symphony and the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra are the state's major orchestras. The latter is the nation's second-oldest symphony orchestra and achieved prominence in recent years under conductor Leonard Slatkin. Branson is well known for its music theaters, most of which bear the name of a star performer or musical group.

Literature

Missouri is the native state of Mark Twain. His novels The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn are set in his boyhood hometown of Hannibal. Authors Kate Chopin, T. S. Eliot and Tennessee Williams were from St. Louis. Kansas City-born writer William Least Heat-Moon resides in Rocheport. He is best known for Blue Highways, a chronicle of his travels to small towns across America, which was on The New York Times Bestseller list for 42 weeks in 1982–1983. Novelist Daniel Woodrell, known for depicting life in the Missouri Ozarks, was born in Springfield and lives in West Plains.

Film

Filmmaker, animator, and businessman Walt Disney spent part of his childhood in the Linn County town of Marceline before settling in Kansas City. Disney began his artistic career in Kansas City, where he founded the Laugh-O-Gram Studio.

Several film versions of Mark Twain's novels The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn have been made. Meet Me in St. Louis, a musical involving the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair, starred Judy Garland. Part of the 1983 road movie National Lampoon's Vacation was shot on location in Missouri, for the Griswolds' trip from Chicago to Los Angeles. The Thanksgiving holiday film Planes, Trains, and Automobiles was partially shot at Lambert–St. Louis International Airport. White Palace was filmed in St. Louis. The award-winning 2010 film Winter's Bone was shot in the Ozarks of Missouri. Up in the Air starring George Clooney was filmed in St. Louis. John Carpenter's Escape from New York was filmed in St. Louis during the early 1980s due to a large number of abandoned buildings in the city. The 1973 movie Paper Moon, which starred Ryan and Tatum O'Neal, was partly filmed in St. Joseph. Most of HBO's film Truman (1995) was filmed in Kansas City, Independence, and the surrounding area; Gary Sinise won an Emmy for his portrayal of Harry Truman in the film. Ride With the Devil (1999), starring Jewel and Tobey Maguire, was filmed in the countryside of Jackson County (where the historical events of the film actually took place). Gone Girl, a 2014 film starring Ben Affleck, Rosamund Pike, Neil Patrick Harris, and Tyler Perry, was filmed in Cape Girardeau.

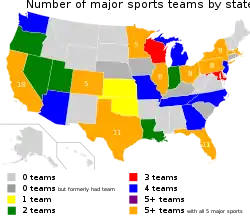

Sports

Missouri hosted the 1904 Summer Olympics at St. Louis, the first time the games were hosted in the United States.

Professional major league teams:

- MLB: St. Louis Cardinals, Kansas City Royals

- NFL: Kansas City Chiefs

- NHL: St. Louis Blues

- MLS: St. Louis City SC (Founded 2019, has not started play yet)

Former professional major league teams:

- National Football League:

- St. Louis Cardinals (moved from Chicago in 1960; moved to Tempe, Arizona, in 1988 and are now the Arizona Cardinals)

- St. Louis All Stars (active in 1923 only)

- Kansas City Blues/Cowboys (active 1924–1926, folded)

- St. Louis Gunners (independent team, joined the NFL for the last three weeks of the 1934 season and folded thereafter)

- St. Louis Rams 1995–2015 moved from Los Angeles and then back to Los Angeles

- Major League Baseball (American League):

- St. Louis Browns (moved from Milwaukee in 1902; moved to Baltimore, Maryland after the 1953 season and are now the Baltimore Orioles)

- Kansas City Athletics (moved from Philadelphia in 1955; moved to Oakland, California after the 1967 season and are now the Oakland Athletics)

- National Basketball Association: