New Spain

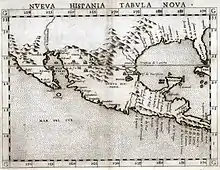

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain (Spanish: Virreinato de Nueva España, Spanish pronunciation: [birejˈnato ðe ˈnweβa esˈpaɲa] (![]() listen)), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Americas and having its capital in Mexico City. Its jurisdiction comprised a huge area that included what is now Mexico, much of the Southwestern U.S. and California in North America; Central America, northern parts of South America, and several territorial Pacific Ocean archipelagos.

listen)), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Americas and having its capital in Mexico City. Its jurisdiction comprised a huge area that included what is now Mexico, much of the Southwestern U.S. and California in North America; Central America, northern parts of South America, and several territorial Pacific Ocean archipelagos.

Viceroyalty of New Spain Virreinato de Nueva España | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1521–1821 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto: Plus Ultra "Further Beyond" | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: Marcha Real "Royal March" (1775–1821) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png.webp)  left: Flag of Spain: first national flag, naval and fortress flag, the last flag to float in continental America, in the Fortress of San Juan de Ulúa. right: Standard of the Viceroyalty of New Spain with Cross of Burgundy and Royal or Duchy Crown (military flag) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Maximum extent of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The areas in light green were territories claimed but not controlled by New Spain. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | México | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Spanish (official, administrative), Nahuatl, Mayan, Indigenous languages, French (Spanish Louisiana) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Kingdom | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1521–1556 | Charles I (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1813–1821 | Ferdinand VII (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Viceroy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1535–1550 | Antonio de Mendoza (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1821 | Juan O'Donojú Political chief superior (not viceroy) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Council of the Indies | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Colonial era | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1519–1521 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Kingdom created | 1521 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Venezuela annexed to Kingdom of New Granada | 27 May 1717 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Panama annexed to New Kingdom of Granada | 1739 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Acquisition of Louisiana from France | 1762 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Treaty of San Ildefonso | 1 October 1800 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Adams-Onís Treaty | 22 February 1819 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Trienio Liberal abolished the Kingdom of New Spain | 31 May 1820 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Mexican War of Independence and Central American Independence | 1821 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1519 | 10 million | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1810 | 8 million | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Spanish colonial real | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

After the 1521 Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire, conqueror Hernán Cortés named the territory New Spain, and established the new capital, Mexico City, on the site of the Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Mexica (Aztec) Empire. Central Mexico became the base of expeditions of exploration and conquest, expanding the territory claimed by the Spanish Empire. With the political and economic importance of the conquest, the crown asserted direct control over the densely populated realm. The crown established New Spain as a viceroyalty in 1535, appointing as viceroy Antonio de Mendoza, an aristocrat loyal to the monarch rather than the conqueror Cortés. New Spain was the first of the viceroyalties that Spain created, the second being Peru in 1542, following the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire. Both New Spain and Peru had dense indigenous populations at conquest as a source of labor and material wealth in the form of vast silver deposits, discovered and exploited beginning in the mid 1500s.

New Spain developed strong regional divisions based on local climate, topography, distance from the capital and the Gulf Coast port of Veracruz, size and complexity of indigenous populations, and the presence or absence of mineral resources. Central and southern Mexico had dense indigenous populations, each with complex social, political, and economic organization, but no large-scale deposits of silver to draw Spanish settlers. By contrast, the northern area of Mexico was arid and mountainous, a region of nomadic and semi-nomadic indigenous populations, which do not easily support human settlement. In the 1540s, the discovery of silver in Zacatecas attracted Spanish mining entrepreneurs and workers, to exploit the mines, as well as crown officials to ensure the crown received its share of revenue. Silver mining became integral not only to the development of New Spain, but also to the enrichment of the Spanish crown, which marked a transformation in the global economy. New Spain's port of Acapulco became the New World terminus of the transpacific trade with Asia via the Manila galleon. The New Spain became a vital link between Spain's New World empire and its East Indies empire.

From the beginning of the 19th century, the kingdom fell into crisis, aggravated by the 1808 Napoleonic invasion of Iberia and the forced abdication of the Bourbon monarch, Charles IV. This resulted in the political crisis in New Spain and much of the Spanish Empire in 1808, which ended with the government of Viceroy José de Iturrigaray. Conspiracies of American-born Spaniards sought to take power, leading to the Mexican War of Independence, 1810-1821. At its conclusion in 1821, the viceroyalty was dissolved and the Mexican Empire was established. Former royalist military officer turned insurgent for independence Agustín de Iturbide would be crowned as emperor.

The Crown and the Viceroyalty of New Spain

The Kingdom of New Spain was established on 18 August 1521, following the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, as a New World kingdom ruled by the Crown of Castile. The initial funds for exploration came from Queen Isabella.[3][4] Although New Spain was a dependency of Castile, it was a kingdom and not a colony, subject to the presiding monarch on the Iberian Peninsula.[5][6]

The monarch had sweeping power in the overseas territories, with not just sovereignty over the realm but also property rights. All power over the state came from the monarch. The crown had sweeping powers over the Roman Catholic Church in its overseas territories, and via the Patronato real, a grant by the papacy to the crown to oversee the Church in all aspects save doctrine. The Viceroyalty of New Spain was created by royal decree on October 12, 1535, in the Kingdom of New Spain with a viceroy appointed as the king's "deputy" or substitute. This was the first New World viceroyalty and one of only two that the Spanish empire administered in the continent until the 18th-century Bourbon Reforms.

Territorial extent of the overseas Spanish Empire

At its greatest extent, the Spanish crown claimed on the mainland of the Americas much of North America south of Canada, that is: all of present-day Mexico and Central America except Panama; most of present-day United States west of the Mississippi River, plus the Floridas. The Spanish West Indies, settled prior to the conquest of the Aztec Empire, also came under New Spain's jurisdiction: (Cuba, Hispaniola (comprising the modern states of Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Puerto Rico, Jamaica, the Cayman Islands, Trinidad, and the Bay Islands). [7][8][9] New Spain also claimed jurisdiction over the overseas territories of the Spanish East Indies in Asia and Oceania, (the Philippine Islands, the Mariana Islands, the Caroline Islands, parts of Taiwan, and parts of the Moluccas). Although asserting sovereignty over this vast realm, it did not effectively control large swaths. Other European powers, including England, France, and the Netherlands established colonies in territories Spain claimed.

Much of what was called in the United States the "Spanish borderlands", is territory that did not attract many Spanish settlers, with less dense indigenous populations and apparently lacking in mineral wealth. Huge deposits of gold in California were discovered immediately after it was incorporated into the U.S. following the Mexican-American War (1846–48). The northern region of New Spain in the colonial era was considered more marginal to Spanish interests than the most densely populated and lucrative areas of central Mexico. To shore up its claims in North America in the eighteenth century as other powers encroached on its claims, the crown sent expeditions to the Pacific Northwest, which explored and claimed the coast of what is now British Columbia and Alaska. Religious missions and fortified presidios were established to shore up Spanish control on the ground. On the mainland, the administrative units included Las Californias, that is, the Baja California peninsula, still part of Mexico and divided into Baja California and Baja California Sur; Alta California (present-day Arizona, California, Nevada, Utah, western Colorado, and southern Wyoming); (from the 1760s) Louisiana (including the western Mississippi River basin and the Missouri River basin); Nueva Extremadura (the present-day states of Coahuila and Texas); and Santa Fe de Nuevo México (parts of Texas and New Mexico).[10]

Government

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

Viceroyalty

The Viceroyalty was administered by a viceroy residing in Mexico City and appointed by the Spanish monarch, who had administrative oversight of all of these regions, although most matters were handled by the local governmental bodies, which ruled the various regions of the viceroyalty. First among these were the audiencias, which were primarily superior tribunals, but which also had administrative and legislative functions. Each of these was responsible to the Viceroy of New Spain in administrative matters (though not in judicial ones), but they also answered directly to the Council of the Indies.

Captaincies general and governorates

The Captaincy Generals were the second-level administrative divisions and these were relatively autonomous from the viceroyalty. Santo Domingo (1535); Philippines (1574); Puerto Rico (1580); Cuba (1608); Guatemala (1609); Yucatán (1617); Commandancy General of the Provincias Internas (1776) (analogous to a dependent captaincy general). Two governorates, third-level administrative divisions, were established, the Governorate of Spanish Florida (Spanish: La Florida) and the Governorate of Spanish Louisiana (Spanish: Luisiana).

High courts

The high courts, or audiencias, were established in major areas of Spanish settlement. In New Spain the high court was established in 1527, prior to the establishment of the viceroyalty. The First Audiencia was headed by Hernán Cortés's rival Nuño de Guzmán, who used the court to deprive Cortés of power and property. The crown dissolved the First Audiencia and established the Second Audiencia.[11] The audiencias of New Spain were Santo Domingo (1511, effective 1526, predated the Viceroyalty); Mexico (1527, predated the Viceroyalty); Panama (1st one, 1538–1543); Guatemala (1543); Guadalajara (1548); Manila (1583). Audiencia districts further incorporated the older, smaller divisions known as governorates (gobernaciones, roughly equivalent to provinces), which had been originally established by conquistador-governors known as adelantados. Provinces which were under military threat were grouped into captaincies general, such as the Captaincies General of the Philippines (established 1574) and Guatemala (established in 1609) mentioned above, which were joint military and political commands with a certain level of autonomy. (The viceroy was captain-general of those provinces that remained directly under his command).

Local-level administration

At the local level there were over two hundred districts, in both indigenous and Spanish areas, which were headed by either a corregidor (also known as an alcalde mayor) or a cabildo (town council), both of which had judicial and administrative powers. In the late 18th century the Bourbon dynasty began phasing out the corregidores and introduced intendants, whose broad fiscal powers cut into the authority of the viceroys, governors and cabildos. Despite their late creation, these intendancies so affected the formation of regional identity that they became the basis for the nations of Central America and the first Mexican states after independence.

Intendancies 1780s

As part of the sweeping eighteenth-century administrative and economic changes known as the Bourbon Reforms, the Spanish crown created new administrative units called intendancies, to strengthen central control over the viceroyalty. Some measures aimed to break the power of local elites in order to improve the economy of the empire. Reforms included the improvement of the public participation in communal affairs, distribution of undeveloped lands to the indigenous and Spaniards, end the corrupt practices of local crown officials, encourage trade and mining, and establish a system of territorial division similar to the model created by the government of France, already adopted in Spain. The establishment of intendancies found strong resistance by the viceroyalties and general captaincies similar to the opposition in the Iberian Peninsula when the reform was adopted. Royal audiencias and ecclesiastical hierarchs opposed the reform for its interventions in economic issues, by its centralist politics, and the forced ceding of many of their functions to the intendants. In New Spain, these units generally corresponded to the regions or provinces that had developed earlier in the center, South, and North. Many of the intendancy boundaries became Mexican state boundaries after independence. The intendancies were created between 1764 and 1789, with the greatest number in the mainland in 1786: 1764 Havana (later subdivided); 1766 New Orleans; 1784 Puerto Rico; 1786 Mexico, Veracruz, Puebla de Los Angeles, Guadalajara, Guanajuato, Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí, Sonora, Durango, Oaxaca, Guatemala, San Salvador, Comayagua, León, Santiago de Cuba, Puerto Príncipe; 1789 Mérida.[12][13]

History of New Spain

The history of mainland New Spain spans three hundred years from the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire (1519–1521) to the collapse of Spanish rule in the Mexican War of Independence (1810–1821).

Conquest era (1521–1535)

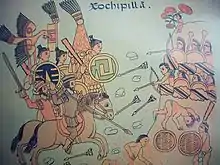

The Caribbean islands and early Spanish explorations around the circum-Caribbean region had not been of major political, strategic, or financial importance until the conquest of the Aztec Empire in 1521. However, important precedents of exploration, conquest, and settlement and crown rule had been initially worked out in the Caribbean, which long affected subsequent regions, including Mexico and Peru.[14] The indigenous societies of Mesoamerica brought under Spanish control were of unprecedented complexity and wealth compared to what the conquerors had encountered in the Caribbean. This presented both an important opportunity and a potential threat to the power of the Crown of Castile, since the conquerors were acting independent of effective crown control. The societies could provide the conquistadors, especially Hernán Cortés, a base from which the conquerors could become autonomous, or even independent, of the Crown. Cortés had already defied orders that curtailed his ambition of an expedition of conquest. He was spectacularly successful in gaining indigenous allies against the Aztec Empire, with the indispensable aid of indigenous cultural translator, Marina, also known as Malinche, toppling the rulers of the Aztec empire. Cortés then divvied up the spoils of war without crown authorization, including grants of labor and tribute of groups of indigenous, to participants in the conquest.

As a result, the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, Charles V created the Council of the Indies[Note 1] in 1524 as the crown entity to oversee the crown's interests in the New World. Since the time of the Catholic Monarchs, central Iberia was governed through councils appointed by the monarch with particular jurisdictions. The creation of the Council of the Indies became another, but extremely important, advisory body to the monarch.

The crown had already created the Casa de Contratación (House of Trade) in 1503 to regulate contacts between Spain and its overseas possessions. A key function was to gather information about navigation to make trips less risky and more efficient. Philip II sought systematic information about his overseas empire and mandated reports, known as the Relaciones geográficas, describing topography, economic conditions, and populations, among other information. They were accompanied by maps of the area discussed, many of which were drawn by indigenous artists.[15][16][17][18][19] The Francisco Hernández Expedition (1570–77), the first scientific expedition to the New World, was sent to gather information on medicinal plants and practices.[20]

The crown created the first mainland high court, or Audiencia, in 1527 to regain control of the administration of New Spain from Cortés, who as the premier conqueror of the Aztec empire, was ruling in the name of the king but without crown oversight or control. An earlier Audiencia had been established in Santo Domingo in 1526 to deal with the Caribbean settlements. That court, housed in the Casa Reales in Santo Domingo, was charged with encouraging further exploration and settlements with the authority granted it by the crown. Management by the Audiencia, which was expected to make executive decisions as a body, proved unwieldy. In 1535, Charles V of Spain appointed Don Antonio de Mendoza as the first Viceroy of New Spain, an aristocrat loyal to the crown, rather than the conqueror Hernán Cortés, who had embarked on the expedition of conquest and distributed spoils of the conquest without crown approval. Cortés was instead awarded a vast, entailed estate and a noble title.

Christian evangelization

Spanish conquerors saw it as their right and their duty to convert indigenous populations to Christianity. Because Christianity had played such an important role in the Reconquista (Christian reconquest) of the Iberian peninsula from the Muslims, the Catholic Church in essence became another arm of the Spanish government, since the crown was granted sweeping powers over ecclesiastical affairs in its overseas territories. The Spanish Crown granted it a large role in the administration of the state, and this practice became even more pronounced in the New World, where prelates often assumed the role of government officials. In addition to the Church's explicit political role, the Catholic faith became a central part of Spanish identity after the conquest of last Muslim kingdom in the peninsula, the Emirate of Granada, and the expulsion of all Jews who did not convert to Christianity.

The conquistadors brought with them many missionaries to promulgate the Catholic religion. Amerindians were taught the Roman Catholic religion and the Spanish language. Initially, the missionaries hoped to create a large body of Amerindian priests, but were not successful. They did work to keep the Amerindian cultural aspects that did not violate the Catholic traditions, and a syncretic religion developed. Most Spanish priests committed themselves to learn the most important Amerindian languages (especially during the 16th century) and wrote grammars so that the missionaries could learn the languages and preach in them. This was similar to practices of French colonial missionaries in North America.

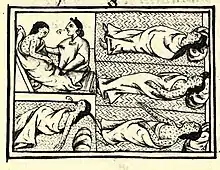

At first, conversion of indigenous peoples seemed to happen rapidly. The missionaries soon found that most of the natives had simply adopted "the god of the heavens," as they called the Christian god, as another one of their many gods. While they often held the Christian god to be an important deity because it was the god of the victorious conquerors, they did not see the need to abandon their old beliefs. As a result, a second wave of missionaries began an effort to completely erase the old beliefs, which they associated with the ritualized human sacrifice found in many of the native religions. They eventually prohibited this practice, which had been common before Spanish colonization. In the process many artifacts of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican culture were destroyed. Hundreds of thousands of native codices were burned, native priests and teachers were persecuted, and the temples and statues of the old gods were torn down. The missionaries even prohibited some foods associated with the native religions, such as amaranth.

Many clerics, such as Bartolomé de las Casas, also tried to protect the natives from de facto and actual enslavement to the settlers, and obtained from the Crown decrees and promises to protect native Mesoamericans, most notably the New Laws. But the royal government was too far away to fully enforce these, and settler abuses against the natives continued, even among the clergy. Eventually, the Crown declared the natives to be legal minors and placed under the guardianship of the Crown, which was responsible for their indoctrination. It was this status that barred the native population from the priesthood. During the following centuries, under Spanish rule, a new culture developed that combined the customs and traditions of the indigenous peoples with that of Catholic Spain. The Spaniards had numerous churches and other buildings constructed in the Spanish style by native labor, and named their cities after various saints or religious topics, such as San Luis Potosí (after Saint Louis) and Vera Cruz (the True Cross).

The Spanish Inquisition, and its New Spanish counterpart, the Mexican Inquisition, continued to operate in the viceroyalty until Mexico declared its independence in 1821. This resulted in the execution of more than 30 people during the colonial period. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the Inquisition worked with the viceregal government to block the diffusion of liberal ideas during the Enlightenment, as well as the revolutionary republican and democratic ideas of the United States War of Independence and the French Revolution.

Sixteenth-century founding of Spanish cities

During the first twenty years after the conquest, before the establishment of the viceroyalty, some of the important cities of the colonial era that remain important today were founded. Even before the 1535 establishment of the viceroyalty of New Spain, conquerors in central Mexico founded new Spanish cities and embarked on further conquests, a pattern that had been established in the Caribbean.[21] In central Mexico, they transformed the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan into the main settlement of the territory; thus, the history of Mexico City is of huge importance to the whole colonial enterprise. Spaniards founded new settlements in Puebla de los Angeles (founded 1531) at the midway point between the Mexico City (founded 1521–24) and the Caribbean port of Veracruz (1519). Colima (1524), Antequera (1526, now Oaxaca City), and Guadalajara (1532) were all new Spanish settlements. North of Mexico City, the city of Querétaro was founded (ca. 1531) in a region known as the Bajío, a major zone of commercial agriculture. Guadalajara was founded northwest of Mexico City (1531–42) and became the dominant Spanish settlement in the region. West of Mexico City the settlement of Valladolid (Michoacan) was founded (1529–41). In the densely populated indigenous South, as noted, Antequera (1526) became the center of Spanish settlement in Oaxaca; Santiago de Guatemala was founded in 1524; and in Yucatán, Mérida (1542) was founded inland, with Campeche founded in 1541 as a small, Caribbean port. Sea trade flourished between Campeche and Veracruz.[22] The discovery of silver in Zacatecas in the far north was a transformative event in the history of New Spain and the Spanish Empire, with silver becoming the primary driver of the economy. The city of Zacatecas was founded in 1547 and Guanajuato, the other major mining region, was founded in 1548, deep in the territory of the nomadic and fierce Chichimeca, whose resistance to Spanish presence became known as the protracted conflict of the Chichimeca War. The silver was so valuable to the crown that waging a fifty-year war was worth doing.[23][24] Other Spanish cities founded before 1600 were the Pacific coast port of Acapulco (1563), Durango (1563), Saltillo (1577), San Luis Potosí (1592), and Monterrey (1596). The cities were outposts of European settlement and crown control, while the countryside was almost exclusively inhabited by the indigenous populations.

Later mainland expansion

During the 16th century, many Spanish cities were established in North and Central America. Spain attempted to establish missions in what is now the southern United States, including Georgia and South Carolina between 1568 and 1587. These efforts were mainly successful in the region of present-day Florida, where the city of St. Augustine was founded in 1565. It is the oldest European city in the United States.

Upon his arrival, Viceroy Don Antonio de Mendoza vigorously took to the duties entrusted to him by the King and encouraged the exploration of Spain's new mainland territories. He commissioned the expeditions of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado into the present day American Southwest in 1540–1542. The Viceroy commissioned Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo in the first Spanish exploration up the Pacific Ocean in 1542–1543. Cabrillo sailed far up the coast, becoming the first European to see present-day California, now part of the United States. The Viceroy also sent Ruy López de Villalobos to the Spanish East Indies in 1542–1543. As these new territories became controlled, they were brought under the purview of the Viceroy of New Spain. Spanish settlers expanded to Nuevo Mexico, and the major settlement of Santa Fe was founded in 1610.

The establishment of religious missions and military presidios on the northern frontier became the nucleus of Spanish settlement and the founding of Spanish towns.

Pacific expansion and the Philippine trade

Seeking to develop trade between the East Indies and the Americas across the Pacific Ocean, Miguel López de Legazpi established the first Spanish settlement in the Philippine Islands in 1565, which became the town of San Miguel (present-day Cebu City). Andrés de Urdaneta discovered an efficient sailing route from the Philippine Islands to Mexico which took advantage of the Kuroshio Current. In 1571, the city of Manila became the capital of the Spanish East Indies, with trade soon beginning via the Manila-Acapulco Galleons. The Manila-Acapulco trade route shipped products such as silk, spices, silver, porcelain and gold to the Americas from Asia.[26][27] The first census in the Philippines was founded in 1591, based on tributes collected. The tributes count the total founding population of Spanish-Philippines as 667,612 people,[28] of which: 20,000 were Chinese migrant traders,[29] at different times: around 16,500 individuals were Latino soldier-colonists who were cumulatively sent from Peru and Mexico and they were shipped to the Philippines annually,[30] 3,000 were Japanese residents,[31] and 600 were pure Spaniards from Europe,[32] there was also a large but unknown number of Indian Filipinos, the rest of the population were Malays and Negritos. Thus, with merely 667,612 people, during this era, the Philippines was among the most sparsely populated lands in Asia.

Despite the sparsity of the Philippine population, it was profitable for Mexico City which used it as a transhipment point of cheap Asian products like Silk and Porcelain, however, due to the higher quantity of products from Asia it became a point of contention with the mercantilist policies of mainland Spain which supported manufacturing based on the capital instead of the colonies, in which case the Manila-Mexico commercial alliance was at odds against Madrid.[33][34] The importance of the Philippines to the Spanish empire can be seen by its creation as a separate Captaincy-General.[35] Products brought from Asia were sent to Acapulco then overland to Veracruz, and then shipped to Spain aboard the West Indies Fleets. Later they were traded across Europe. Several cities and towns in the Philippines were founded as Presidios commanded by Spanish officers and staffed by Mexican and Peruvian soldiers who were mostly forcefully conscripted vagrants, estranged teenagers, petty criminals, rebels or political exiles at Mexico and Peru and were thus a rebellious element among the Spanish colonial apparatus in the Philippines.[36]

Since the Philippines was at the center of a crescent from Japan to Indonesia, it alternated into periods of extreme wealth congregating to the location,[37] to periods where it was the arena of constant warfare waged between it and the surrounding nation(s).[38] This left only the fittest and strongest to survive and serve out their military service. There was thus high desertion and death rates which also applied to the native Filipino warriors and laborers levied by Spain, to fight in battles all across the archipelago and elsewhere or build galleons and public works. The repeated wars, lack of wages, dislocation, and near starvation were so intense, that almost half of the soldiers sent from Latin America and the warriors and laborers recruited locally either died or disbanded to the lawless countryside to live as vagabonds among the rebellious natives, escaped enslaved Indians (from India)[39] and Negrito nomads, where they race-mixed through rape or prostitution, which increased the number of Filipinos of Spanish or Latin American descent, but were not the children of valid marriages.[40] This further blurred the racial caste system Spain tried so hard to maintain in the towns and cities.[41] These circumstances contributed to the increasing difficulty of governing the Philippines. Due to these, the Royal Fiscal of Manila wrote a letter to King Charles III of Spain, in which he advises to abandon the colony, but this was successfully opposed by the religious and missionary orders that argued that the Philippines was a launching pad for further conversions in the Far East.[42] Due to the missionary nature of the Philippine colony, unlike in Mexico where most immigrants were of a civilian nature, most settlers in the Philippines were either soldiers, merchants or clergy and were overwhelmingly male.

At times, non-profitable war-torn Philippine colony survived on an annual subsidy paid by the Spanish Crown and often procured from taxes and profits accumulated by the Viceroyalty of New Spain (Mexico), mainly paid by annually sending 75 tons of precious Silver Bullion,[43] gathered from and mined from Potosi, Bolivia where hundreds of thousands of Incan lives were regularly lost while being enslaved to the Mit'a system.[44] Unfortunately, the silver mined through the cost of many lives and being a precious metal barely made it to the starving or dying Spanish, Mexican, Peruvian and Filipino soldiers who were stationed in presidios across the archipelago, struggling against constant invasions, while it was sought after by Chinese, Indian, Arab and Malay merchants in Manila who traded with the Latinos for their precious metal in exchange for silk, spices, pearls and aromatics. Trade and immigration was not just aimed towards the Philippines, however. It also went the opposite direction, to the Americas, from rebellious Filipinos, especially the exiled Filipino royalties, who were denied their traditional rights by new Spanish officers from Spain who replaced the original Spanish conquistadors from Mexico who were more political in alliance-making and who they had treaties of friendship with (due to their common hatred against Muslims, since native Pagan Filipinos fought against the Brunei Sultanate and native Spaniards conquered the Emirate of Granada). The idealistic original pioneers died and were replaced by ignorant royal officers who broke treaties, thus causing the Conspiracy of the Maharlikas among Filipinos, who conspired together with Bruneians and Japanese, yet the failure of the conspiracy caused the royals' exile to the Americas, where they formed communities across the western coasts, chief among which was Guerrero, Mexico,[45] which was later a center of the Mexican war of Independence.[46]

Spanish ocean trade routes and defense

The Spanish crown created a system of convoys of ships (called the flota) to prevent attacks by European privateers. Some isolated attacks on these shipments took place in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea by English and Dutch pirates and privateers. One such act of piracy was led by Francis Drake in 1580, and another by Thomas Cavendish in 1587. In one episode, the cities of Huatulco (Oaxaca) and Barra de Navidad in Jalisco Province of México were sacked. However, these maritime routes, both across the Pacific and the Atlantic, were successful in the defensive and logistical role they played in the history of the Spanish Empire. For over three centuries the Spanish Navy escorted the galleon convoys that sailed around the world. Don Lope Díez de Armendáriz, born in Quito, Ecuador, was the first Viceroy of New Spain who was born in the 'New World'. He formed the 'Navy of Barlovento' (Armada de Barlovento), based in Veracruz, to patrol coastal regions and protect the harbors, port towns, and trade ships from pirates and privateers.

Indigenous revolts

After the invasion of central Mexico, there were many major Native American rebellions defeating, changing or challenging Spanish rule. In the Mixtón war in 1541, the viceroy Don Antonio de Mendoza led an army against an uprising by Caxcanes. In the 1680 Pueblo revolt, Indians in 24 settlements in New Mexico expelled the Spanish, who left for Texas, an exile lasting a decade. The Chichimeca war lasted over fifty years, 1550–1606, between the Spanish and various indigenous groups of northern New Spain, particularly in silver mining regions and the transportation trunk lines.[47] Non-sedentary or semi-sedentary Northern Indians were difficult to control once they acquired the mobility of the horse.[48] In 1616, the Tepehuan revolted against the Spanish, but it was relatively quickly suppressed.[49] The Tarahumara Indians were in revolt in the mountains of Chihuahua for several years. In 1670 Chichimecas invaded Durango, and the governor, Francisco González, abandoned its defense. The Spanish-Chamorro Wars that began on Guam in 1670 after the Spanish establishment of a physical presence resulted in a series of sieges of the Spanish presidio, the last in 1684.

In the southern area of New Spain, the Tzeltal Maya and other indigenous groups, including the Tzotzil and Chol revolted in 1712. It was a multiethnic revolt sparked by religious issues in several communities.[50] In 1704 viceroy Francisco Fernández de la Cueva suppressed a rebellion of Pima in Nueva Vizcaya.

Bourbon reforms

The Bourbon monarchy embarked upon a far-reaching program to revitalize the economy of its territories, both on the peninsula and its overseas possessions. The crown sought to enhance its control and administrative efficiency, and to decrease the power and privilege of the Roman Catholic Church vis-a-vis the state.[51][52]

The British capture and occupation of both Manila and Havana in 1762, during the global conflict of the Seven Years' War, meant that the Spanish crown had to rethink its military strategy for defending its possessions. The Spanish crown had engaged with Britain for a number of years in low-intensity warfare, with ports and trade routes harassed by English privateers. The crown strengthened the defenses of Veracruz and San Juan de Ulúa, Jamaica, Cuba, and Florida, but the British sacked ports in the late seventeenth century. Santiago de Cuba (1662), St. Augustine Spanish Florida (1665) and Campeche 1678 and so with the loss of Havana and Manila, Spain realized it needed to take significant steps. The Bourbons created a standing army in New Spain, beginning in 1764, and strengthened defensive infrastructure, such as forts.[53][54]

The crown sought reliable information about New Spain and dispatched José de Gálvez as Visitador General (inspector general), who observed conditions needing reform, starting in 1765, in order to strengthen crown control over the kingdom.[55]

An important feature of the Bourbon Reforms was that they ended the significant amount of local control that was a characteristic of the bureaucracy under the Habsburgs, especially through the sale of offices. The Bourbons sought a return to the monarchical ideal of having those not directly connected with local elites as administrators, who in theory should be disinterested, staff the higher echelons of regional government. In practice this meant that there was a concerted effort to appoint mostly peninsulares, usually military men with long records of service (as opposed to the Habsburg preference for prelates), who were willing to move around the global empire. The intendancies were one new office that could be staffed with peninsulares, but throughout the 18th century significant gains were made in the numbers of governors-captain generals, audiencia judges and bishops, in addition to other posts, who were Spanish-born.

In 1766, the crown appointed Carlos Francisco de Croix, marqués de Croix as viceroy of New Spain. One of his early tasks was to implement the crown's decision to expel the Jesuits from all its territories, accomplished in 1767. Since the Jesuits had significant power, owning large, well managed haciendas, educating New Spain's elite young men, and as a religious order resistant to crown control, the Jesuits were a major target for the assertion of crown control. Croix closed the religious autos-de-fe of the Holy Office of the Inquisition to public viewing, signaling a shift in the crown's attitude toward religion. Other significant accomplishments under Croix's administration was the founding of the College of Surgery in 1768, part of the crown's push to introduce institutional reforms that regulated professions. The crown was also interested in generating more income for its coffers and Croix instituted the royal lottery in 1769. Croix also initiated improvements in the capital and seat of the viceroyalty, increasing the size of its central park, the Alameda.

Another activist viceroy carrying out reforms was Antonio María de Bucareli y Ursúa, marqués de Valleheroso y conde de Jerena, who served from 1771 to 1779, and died in office. José de Gálvez, now Minister of the Indies following his appointment as Visitor General of New Spain, briefed the newly appointed viceroy about reforms to be implemented. In 1776, a new northern territorial division was established, Commandancy General of the Provincias Internas known as the Provincias Internas (Commandancy General of the Internal Provinces of the North, Spanish: Comandancia y Capitanía General de las Provincias Internas). Teodoro de Croix (nephew of the former viceroy) was appointed the first Commander General of the Provincias Internas, independent of the Viceroy of New Spain, to provide better administration for the northern frontier provinces. They included Nueva Vizcaya, Nuevo Santander, Sonora y Sinaloa, Las Californias, Coahuila y Tejas (Coahuila and Texas), and Nuevo México. Bucareli was opposed to Gálvez's plan to implement the new administrative organization of intendancies, which he believed would burden areas with sparse population with excessive costs for the new bureaucracy.[56]

The new Bourbon kings did not split the Viceroyalty of New Spain into smaller administrative units as they did with the Viceroyalty of Peru, carving out the Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata and the Viceroyalty of New Granada, but New Spain was reorganized administratively and elite American-born Spanish men were passed over for high office. The crown also established a standing military, with the aim of defending its overseas territories.

The Spanish Bourbons monarchs' prime innovation introduction of intendancies, an institution emulating that of Bourbon France. They were first introduced on a large scale in New Spain, by the Minister of the Indies José de Gálvez, in the 1770s, who originally envisioned that they would replace the viceregal system (viceroyalty) altogether. With broad powers over tax collection and the public treasury and with a mandate to help foster economic growth over their districts, intendants encroached on the traditional powers of viceroys, governors and local officials, such as the corregidores, which were phased out as intendancies were established. The Crown saw the intendants as a check on these other officers. Over time accommodations were made. For example, after a period of experimentation in which an independent intendant was assigned to Mexico City, the office was thereafter given to the same person who simultaneously held the post of viceroy. Nevertheless, the creation of scores of autonomous intendancies throughout the Viceroyalty, created a great deal of decentralization, and in the Captaincy General of Guatemala, in particular, the intendancy laid the groundwork for the future independent nations of the 19th century. In 1780, Minister of the Indies José de Gálvez sent a royal dispatch to Teodoro de Croix, Commandant General of the Internal Provinces of New Spain (Provincias Internas), asking all subjects to donate money to help the American Revolution. Millions of pesos were given.

The focus on the economy (and the revenues it provided to the royal coffers) was also extended to society at large. Economic associations were promoted, such as the Economic Society of Friends of the Country. Similar "Friends of the Country" economic societies were established throughout the Spanish world, including Cuba and Guatemala.[57]

The crown sent a series of scientific expeditions to its overseas possessions, including the Royal Botanical Expedition to New Spain, led by Martín de Sessé and José Mariano Mociño (1787–1808).[58] Alexander von Humboldt spent a year in New Spain in 1804 on his self-funded scientific expedition to Spanish America. Trained as a mining engineer, Humboldt's observations of silvermining in New Spain were especially important to the crown, which depended on New World silver revenues.

The Bourbon Reforms were not a unified or entirely coherent program, but instead a series of crown initiatives designed to revitalize the economies of its overseas possessions and make administration more efficient and firmly under control of the crown. Record keeping improved and records were more centralized. The bureaucracy was staffed with well-qualified men, most of them peninsular-born Spaniards. The preference for them meant that there was resentment from American-born elite men and their families, who were excluded from holding office. The creation of a military meant that some American Spaniards became officers in local militias, but the ranks were filled with poor, mixed-race men, who resented service and avoided it if possible.[59]

Carlos Francisco de Croix, 1st Marquess of Croix, Viceroy of New Spain (1766–1771)

Carlos Francisco de Croix, 1st Marquess of Croix, Viceroy of New Spain (1766–1771) Antonio María de Bucareli, Viceroy of New Spain

Antonio María de Bucareli, Viceroy of New Spain Juan Vicente de Güemes, 2nd Count of Revillagigedo, Viceroy of New Spain (1789–1794)

Juan Vicente de Güemes, 2nd Count of Revillagigedo, Viceroy of New Spain (1789–1794)

18th-century military conflicts

The first century that saw the Bourbons on the Spanish throne coincided with series of global conflicts that pitted primarily France against Great Britain. Spain, as an ally of Bourbon France, was drawn into these conflicts. In fact part of the motivation for the Bourbon Reforms was the perceived need to prepare the empire administratively, economically, and militarily for what was the next expected war. The Seven Years' War proved to be catalyst for most of the reforms in the overseas possessions, just like the War of the Spanish Succession had been for the reforms on the Peninsula.

In 1720, the Villasur expedition from Santa Fe met and attempted to parley with French- allied Pawnee in what is now Nebraska. Negotiations were unsuccessful, and a battle ensued; the Spanish were badly defeated, with only thirteen managing to return to New Mexico. Although this was a small engagement, it is significant in that it was the deepest penetration of the Spanish into the Great Plains, establishing the limit to Spanish expansion and influence there.

The War of Jenkins' Ear broke out in 1739 between the Spanish and British and was confined to the Caribbean and Georgia. The major action in the War of Jenkins' Ear was a major amphibious attack launched by the British under Admiral Edward Vernon in March 1741 against Cartagena de Indias, one of Spain's major gold-trading ports in the Caribbean (today Colombia). Although this episode is largely forgotten, it ended in a decisive victory for Spain, who managed to prolong its control of the Caribbean and indeed secure the Spanish Main until the 19th century.

Following the French and Indian War/Seven Years' War, the British troops invaded and captured the Spanish cities of Havana in Cuba and Manila in the Philippines in 1762. The Treaty of Paris (1763) gave Spain control over the Louisiana part of New France including New Orleans, creating a Spanish empire that stretched from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean; but Spain also ceded Florida to Great Britain in order to regain Cuba, which the British occupied during the war. Louisiana settlers, hoping to restore the territory to France, in the bloodless Rebellion of 1768 forced the Louisiana Governor Antonio de Ulloa to flee to Spain. The rebellion was crushed in 1769 by the next governor Alejandro O'Reilly, who executed five of the conspirators. The Louisiana territory was to be administered by superiors in Cuba with a governor on site in New Orleans.

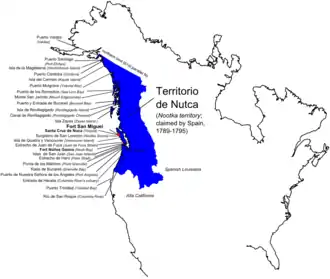

The 21 northern missions in present-day California (U.S.) were established along California's El Camino Real from 1769. In an effort to exclude Britain and Russia from the eastern Pacific, King Charles III of Spain sent forth from Mexico a number of expeditions to the Pacific Northwest between 1774 and 1793. Spain's long-held claims and navigation rights were strengthened and a settlement and fort were built in Nootka Sound, Alaska.

Spain entered the American Revolutionary War as an ally of the United States and France in June 1779. From September 1779 to May 1781, Bernardo de Galvez led an army in a campaign along the Gulf Coast against the British. Galvez's army consisted of Spanish regulars from throughout Latin America and a militia which consisted of mostly Acadians along with Creoles, Germans, and Native Americans. Galvez's army engaged and defeated the British in battles fought at Manchac and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Natchez, Mississippi, Mobile, Alabama, and Pensacola, Florida. The loss of Mobile and Pensacola left the British with no bases along the Gulf Coast. In 1782, forces under Galvez's overall command captured the British naval base at Nassau on New Providence Island in the Bahamas. Galvez was angry that the operation had proceeded against his orders to cancel, and ordered the arrest and imprisonment of Francisco de Miranda, aide-de-camp of Juan Manuel Cajigal, the commander of the expedition. Miranda later ascribed this action on the part of Galvez to jealousy of Cajigal's success.

In the second Treaty of Paris (1783), which ended the American Revolution, Great Britain returned control of Florida back to Spain in exchange for the Bahamas. Spain then had control over the Mississippi River south of 32°30' north latitude, and, in what is known as the Spanish Conspiracy, hoped to gain greater control of Louisiana and all of the west. These hopes ended when Spain was pressured into signing Pinckney's Treaty in 1795. France re-acquired Louisiana from Spain in the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso in 1800. The United States bought the territory from France in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803.

New Spain claimed the entire west coast of North America and therefore considered the Russian fur trading activity in Alaska, which began in the middle to late 18th century, an encroachment and threat. Likewise, the exploration of the northwest coast by Captain James Cook of the British Navy and the subsequent fur trading activities by British ships was considered an encroachment on Spanish territory. To protect and strengthen its claim, New Spain sent a number of expeditions to the Pacific Northwest between 1774 and 1793. In 1789, a naval outpost called Santa Cruz de Nuca (or just Nuca) was established at Friendly Cove in Nootka Sound (now Yuquot), Vancouver Island. It was protected by an artillery land battery called Fort San Miguel. Santa Cruz de Nuca was the northernmost establishment of New Spain. It was the first European colony in what is now the province of British Columbia and the only Spanish settlement in what is now Canada. Santa Cruz de Nuca remained under the control of New Spain until 1795, when it was abandoned under the terms of the third Nootka Convention. Another outpost, intended to replace Santa Cruz de Nuca, was partially built at Neah Bay on the southern side of the Strait of Juan de Fuca in what is now the U.S. state of Washington. Neah Bay was known as Bahía de Núñez Gaona in New Spain, and the outpost there was referred to as "Fuca." It was abandoned, partially finished, in 1792. Its personnel, livestock, cannons, and ammunition were transferred to Nuca.[60]

In 1789, at Santa Cruz de Nuca, a conflict occurred between the Spanish naval officer Esteban José Martínez and the British merchant James Colnett, triggering the Nootka Crisis, which grew into an international incident and the threat of war between Britain and Spain. The first Nootka Convention averted the war but left many specific issues unresolved. Both sides sought to define a northern boundary for New Spain. At Nootka Sound, the diplomatic representative of New Spain, Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra, proposed a boundary at the Strait of Juan de Fuca, but the British representative, George Vancouver refused to accept any boundary north of San Francisco. No agreement could be reached and the northern boundary of New Spain remained unspecified until the Adams–Onís Treaty with the United States (1819). That treaty also ceded Spanish Florida to the United States.

End of the Viceroyalty (1806–1821)

_01.svg.png.webp)

The Third Treaty of San Ildefonso ceded to France the vast territory that Napoleon then sold to the United States in 1803, known as the Louisiana Purchase. The United States obtained Spanish Florida in 1819 in the Adams–Onís Treaty. That treaty also defined a northern border for New Spain, at 42° north latitude (now the northern boundary of the U.S. states of California, Nevada, and Utah).

In the 1821 Declaration of Independence of the Mexican Empire, both Mexico and Central America declared their independence after three centuries of Spanish rule and formed the First Mexican Empire, although Central America quickly rejected the union. After priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla's 1810 Grito de Dolores (call for independence), the insurgent army began an eleven-year war. At first, the Criollo class fought against the rebels. But in 1820, a military coup in Spain forced Ferdinand VII to accept the authority of the liberal Spanish Constitution. The specter of liberalism that could undermine the authority and autonomy of the Roman Catholic Church made the Church hierarchy in New Spain view independence in a different light. In an independent nation, the Church anticipated retaining its power. Royalist military officer Agustín de Iturbide proposed uniting with the insurgents with whom he had battled, and gained the alliance of Vicente Guerrero, leader of the insurgents in a region now bearing his name, a region that was populated by immigrants from Africa and the Philippines,[61][62] crucial among which was the Filipino-Mexican General Isidoro Montes de Oca who impressed Criollo Royalist Itubide into joining forces with Vicente Guerrero by Isidoro Montes De Oca defeating royalist forces three times larger than his, in the name of his leader, Vicente Guerrero.[63] Royal government collapsed in New Spain and the Army of the Three Guarantees marched triumphantly into Mexico City in 1821.

The new Mexican Empire offered the crown to Ferdinand VII or to a member of the Spanish royal family that he would designate. After the refusal of the Spanish monarchy to recognize the independence of Mexico, the ejército Trigarante (Army of the Three Guarantees), led by Agustín de Iturbide and Vicente Guerrero, cut all political and economic ties with Spain and crowned Iturbide as emperor Agustín of Mexico. Central America was originally envisioned as part of the Mexican Empire; but it seceded peacefully in 1823, forming the United Provinces of Central America under the Constitution of 1824.

This left only Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Spanish West Indies, and the Philippines in the Spanish East Indies as part of the Spanish Empire; until their loss to the United States in the Spanish–American War (1898). Before, the Spanish-American War, the Philippines had an almost successful revolt against Spain under the uprising of Andres Novales which were supported by Criollos and Latin Americans who were the Philippines, mainly by the former Latino officers “americanos”, composed mostly of Mexicans with a sprinkling of Creoles and Mestizos from the now independent nations of Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Chile, Argentina and Costa Rica.[64] went out to start a revolt.[65][66] In the aftermath, Spain, in order to ensure obedience to the empire, disconnected the Philippines from her Latin-American allies and placed in the Spanish army of the colony, Peninsulars from the mainland, which displaced and angered the Latin American and Filipino soldiers who were at the Philippines.[67]

The legacy of the colonial era Mexico is significant in many domains. Mexico was the location of the first printing shop (1539),[68] first university (1551),[69] first public park (1592),[70] and first public library (1640) in the Americas,[71] among other institutions. Important artists of the colonial period, include the writers Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora, and Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, painters Cristóbal de Villalpando and Miguel Cabrera, and architect Manuel Tolsá. The Academy of San Carlos (1781) was the first major school and museum of art in the Americas.[72] German scientist Alexander von Humboldt spent a year in Mexico, finding the scientific community in the capital active and learned. He met Mexican scientist Andrés Manuel del Río Fernández, who discovered the element vanadium in 1801.[73] Many Mexican cultural features including tequila,[74] first distilled in the 16th century, charreria (17th),[75] mariachi (18th) and Mexican cuisine, a fusion of American and European (particularly Spanish) cuisine, arose during the colonial era.

Economy

.jpg.webp)

During the era of the conquest, in order to pay off the debts incurred by the conquistadors and their companies, the new Spanish governors awarded their men grants of native tribute and labor, known as encomiendas. In New Spain these grants were modeled after the tribute and corvee labor that the Mexica rulers had demanded from native communities. This system came to signify the oppression and exploitation of natives, although its originators may not have set out with such intent. In short order the upper echelons of patrons and priests in the society lived off the work of the lower classes. Due to some horrifying instances of abuse against the indigenous peoples, Bishop Bartolomé de las Casas suggested bringing black slaves to replace them. Fray Bartolomé later repented when he saw the even worse treatment given to the black slaves.

In colonial Mexico, encomenderos de negros were specialized middlemen during the first half of the seventeenth century. While encomendero (alternatively, encomenderos de indios) generally refers to men granted the labor and tribute of a particular indigenous group in the immediate post-conquest era, encomenderos de negros were Portuguese slave dealers who were permitted to operate in Mexico for the slave trade.

In Peru, the other discovery that perpetuated the system of forced labor, the mit'a, was the enormously rich single silver mine discovered at Potosí, but in New Spain, labor recruitment differed significantly. With the exception of silver mines worked in the Aztec period at Taxco, southwest of Tenochtitlan, the Mexico's mining region was outside the area of dense indigenous settlement. Labor for the mines in the north of Mexico had a workforce of black slave labor and indigenous wage labor, not draft labor.[76] Indigenous who were drawn to the mining areas were from different regions of the center of Mexico, with a few from the north itself. With such diversity they did not have a common ethnic identity or language and rapidly assimilated to Hispanic culture. Although mining was difficult and dangerous, the wages were good, which is what drew the indigenous labor.[76]

The Viceroyalty of New Spain was the principal source of income for Spain in the eighteenth century, with the revival of mining under the Bourbon Reforms. Important mining centers like Zacatecas, Guanajuato, San Luis Potosí and Hidalgo had been established in the sixteenth century and suffered decline for a variety of reasons in the seventeenth century, but silver mining in Mexico out-performed all other Spanish overseas territories in revenues for the royal coffers.

The fast red dye cochineal was an important export in areas such as central Mexico and Oaxaca in terms of revenues to the crown and stimulation of the internal market of New Spain. Cacao and indigo were also important exports for the New Spain, but was used through rather the vice royalties rather than contact with European countries due to piracy, and smuggling.[77] The indigo industry in particular also helped to temporarily unite communities throughout the Kingdom of Guatemala due to the smuggling.[77]

There were two major ports in New Spain, Veracruz the viceroyalty's principal port on the Atlantic, and Acapulco on the Pacific, terminus of the Manila Galleon. In the Philippines Manila near the South China Sea was the main port. The ports were fundamental for overseas trade, stretching a trade route from Asia, through the Manila Galleon to the Spanish mainland.

These were ships that made voyages from the Philippines to Mexico, whose goods were then transported overland from Acapulco to Veracruz and later reshipped from Veracruz to Cádiz in Spain. So then, the ships that set sail from Veracruz were generally loaded with merchandise from the East Indies originating from the commercial centers of the Philippines, plus the precious metals and natural resources of Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. During the 16th century, Spain held the equivalent of US$1.5 trillion (1990 terms) in gold and silver received from New Spain.

However, these resources did not translate into development for the Metropolis (mother country) due to Spanish Roman Catholic Monarchy's frequent preoccupation with European wars (enormous amounts of this wealth were spent hiring mercenaries to fight the Protestant Reformation), as well as the incessant decrease in overseas transportation caused by assaults from companies of British buccaneers, Dutch corsairs and pirates of various origin. These companies were initially financed by, at first, by the Amsterdam stock market, the first in history and whose origin is owed precisely to the need for funds to finance pirate expeditions, as later by the London market. The above is what some authors call the "historical process of the transfer of wealth from the south to the north."

Regions of mainland New Spain

In the colonial period, basic patterns of regional development emerged and strengthened.[78] European settlement and institutional life was built in the Mesoamerican heartland of the Aztec Empire in Central Mexico. The South (Oaxaca, Michoacan, Yucatán, and Central America) was a region of dense indigenous settlement of Mesoamerica, but without exploitable resources of interest to Europeans, the area attracted few Europeans, while the indigenous presence remained strong. The North was outside the area of complex indigenous populations, inhabited primarily by nomadic and hostile northern indigenous groups. With the discovery of silver in the north, the Spanish sought to conquer or pacify those peoples in order to exploit the mines and develop enterprises to supply them. Nonetheless, much of northern New Spain had sparse indigenous population and attracted few Europeans. The Spanish crown and later the Republic of Mexico did not effectively exert sovereignty over the region, leaving it vulnerable to the expansionism of the United States in the nineteenth century.

Regional characteristics of colonial Mexico have been the focus of considerable study within the vast scholarship on centers and peripheries.[78][79] For those based in the vice-regal capital of Mexico City itself, everywhere else were the "provinces." Even in the modern era, "Mexico" for many refers solely to Mexico City, with the pejorative view of anywhere but the capital is a hopeless backwater.[80] "Fuera de México, todo es Cuauhtitlán" ["outside of Mexico City, it's all Podunk"],[81][82] that is, poor, marginal, and backward, in short, the periphery. The picture is far more complex, however; while the capital is enormously important as the center of power of various kinds (institutional, economic, social), the provinces played a significant role in colonial Mexico. Regions (provinces) developed and thrived to the extent that they were sites of economic production and tied into networks of trade. "Spanish society in the Indies was import-export oriented at the very base and in every aspect," and the development of many regional economies was usually centered on support of that export sector.[83]

Mexico City, Capital of the Viceroyalty

Mexico City was the center of the Central region, and the hub of New Spain. The development of Mexico City itself is extremely important to the development of New Spain as a whole. It was the seat of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, the Archdiocese of the Catholic Church, the Holy Office of the Inquisition, the merchants' guild (consulado), and home of the most elite families in the Kingdom of New Spain. Mexico City was the single-most populous city, not just in New Spain, but for many years the entire Western Hemisphere, with a high concentration of mixed-race castas.

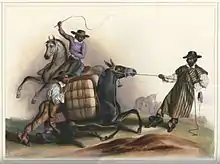

Veracruz to Mexico City

Significant regional development grew along the main transportation route from the capital east to the port of Veracruz. Alexander von Humboldt called this area, Mesa de Anahuac, which can be defined as the adjacent valleys of Puebla, Mexico, and Toluca, enclosed by high mountains, along with their connections to the Gulf Coast port of Veracruz and the Pacific port of Acapulco, where over half the population of New Spain lived.[84] These valleys were linked trunk lines, or main routes, facilitating the movement of vital goods and people to get to key areas.[85] Even in this relatively richly endowed region of Mexico, the difficulty of transit of people and goods in the absence of rivers and level terrain remained a major challenge to the economy of New Spain. This challenge persisted during the post-independence years until the late nineteenth-century construction of railroads. In the colonial era and up until the railroads were built in key areas in post-independence in the late nineteenth century, mule trains were the main mode of transporting goods. Mules were used because unpaved roads, mountainous terrain, and seasonal flooding could not generally accommodate carts.

In the late eighteenth century, the crown devoted some resources to the study and remedy the problem of poor roads. The Camino Real (royal road) between the port of Veracruz and the capital had some short sections paved and bridges constructed. The construction was done despite protests from some indigenous settlements when the infrastructure improvements, which sometimes included rerouting the road through communal lands. The Spanish crown finally decided that road improvement was in the interests of the state for military purposes, as well as for fostering commerce, agriculture, and industry, but the lack of state involvement in the development of physical infrastructure was to have lasting effects constraining development until the late nineteenth century.[86][87] Despite some road improvements, transit was still difficult, particularly for heavy military equipment.

Although the crown had ambitious plans for both the Toluca and Veracruz portions of the king's highway, actual improvements were limited to a localized network.[88] Even where infrastructure was improved, transit on the Veracruz-Puebla main road had other obstacles, with wolves attacking mule trains, killing animals, and rendering some sacks of foodstuffs unsellable because they were smeared with blood.[89] The north-south Acapulco route remained a mule track through mountainous terrain.

Veracruz, port city and province

Veracruz was the first Spanish settlement founded in what became New Spain, and it endured as the only viable Gulf Coast port, the gateway for Spain to New Spain. The difficult topography around the port affected local development and New Spain as a whole. Going from the port to the central plateau entailed a daunting 2000 meter climb from the narrow tropical coastal plain in just over a hundred kilometers. The narrow, slippery road in the mountain mists was treacherous for mule trains, and in some cases mules were hoisted by ropes. Many tumbled with their cargo to their deaths.[90] Given these transport constraints, only high-value, low-bulk goods continued to be shipped in the transatlantic trade, which stimulated local production of foodstuffs, rough textiles, and other products for a mass market. Although New Spain produced considerable sugar and wheat, these were consumed exclusively in the colony even though there was demand elsewhere. Philadelphia, not New Spain, supplied Cuba with wheat.[91]

The Caribbean port of Veracruz was small, with its hot, pestilential climate not a draw for permanent settlers: its population never topped 10,000.[92] Many Spanish merchants preferred living in the pleasant highland town of Jalapa (1,500 m). For a brief period (1722–76) the town of Jalapa became even more important than Veracruz, after it was granted the right to hold the royal trade fair for New Spain, serving as the entrepot for goods from Asia via Manila Galleon through the port of Acapulco and European goods via the flota (convoy) from the Spanish port of Cádiz.[93] Spaniards also settled in the temperate area of Orizaba, east of the Citlaltepetl volcano. Orizaba varied considerably in elevation from 800 metres (2,600 ft) to 5,700 metres (18,700 ft) (the summit of the Citlaltepetl volcano), but "most of the inhabited part is temperate."[94] Some Spaniards lived in semitropical Córdoba, which was founded as a villa in 1618, to serve as a Spanish base against runaway slave (cimarrón) predations on mule trains traveling the route from the port to the capital. Some cimarrón settlements sought autonomy, such as one led by Gaspar Yanga, with whom the crown concluded a treaty leading to the recognition of a largely black town, San Lorenzo de los Negros de Cerralvo, now called the municipality of Yanga.[95]

European diseases immediately affected the multiethnic Indian populations in the Veracruz area and for that reason Spaniards imported black slaves as either an alternative to indigenous labor or its complete replacement in the event of a repetition of the Caribbean die-off. A few Spaniards acquired prime agricultural lands left vacant by the indigenous demographic disaster. Portions of the province could support sugar cultivation and as early as the 1530s sugar production was underway. New Spain's first viceroy, Don Antonio de Mendoza established an hacienda on lands taken from Orizaba.[96]

Indians resisted cultivating sugarcane themselves, preferring to tend their subsistence crops. As in the Caribbean, black slave labor became crucial to the development of sugar estates. During the period 1580–1640 when Spain and Portugal were ruled by the same monarch and Portuguese slave traders had access to Spanish markets, African slaves were imported in large numbers to New Spain and many of them remained in the region of Veracruz. But even when that connection was broken and prices rose, black slaves remained an important component of Córdoba's labor sector even after 1700. Rural estates in Córdoba depended on African slave labor, who were 20% of the population there, a far greater proportion than any other area of New Spain, and greater than even nearby Jalapa.[97]

In 1765 the crown created a monopoly on tobacco, which directly affected agriculture and manufacturing in the Veracruz region. Tobacco was a valuable, high-demand product. Men, women, and even children smoked, something commented on by foreign travelers and depicted in eighteenth-century casta paintings.[98] The crown calculated that tobacco could produce a steady stream of tax revenues by supplying the huge Mexican demand, so the crown limited zones of tobacco cultivation. It also established a small number of manufactories of finished products, and licensed distribution outlets (estanquillos).[99] The crown also set up warehouses to store up to a year's worth of supplies, including paper for cigarettes, for the manufactories.[100] With the establishment of the monopoly, crown revenues increased and there is evidence that despite high prices and expanding rates of poverty, tobacco consumption rose while at the same time, general consumption fell.[101]

In 1787 during the Bourbon Reforms Veracruz became an intendancy, a new administrative unit.

Valley of Puebla

Founded in 1531 as a Spanish settlement, Puebla de los Angeles quickly rose to the status of Mexico's second-most important city. Its location on the main route between the viceregal capital and the port of Veracruz, in a fertile basin with a dense indigenous population, largely not held in encomienda, made Puebla a destination for many later arriving Spaniards. If there had been significant mineral wealth in Puebla, it could have been even more prominent a center for New Spain, but its first century established its importance. In 1786 it became the capital of an intendancy of the same name.[102]

It became the seat of the richest diocese in New Spain in its first century, with the seat of the first diocese, formerly in Tlaxcala, moved there in 1543.[103] Bishop Juan de Palafox asserted the income from the diocese of Puebla as being twice that of the archbishopic of Mexico, due to the tithe income derived from agriculture.[104] In its first hundred years, Puebla was prosperous from wheat farming and other agriculture, as the ample tithe income indicates, plus manufacturing woolen cloth for the domestic market. Merchants, manufacturers, and artisans were important to the city's economic fortunes, but its early prosperity was followed by stagnation and decline in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[105]

The foundation of the town of Puebla was a pragmatic social experiment to settle Spanish immigrants without encomiendas to pursue farming and industry.[106] Puebla was privileged in a number of ways, starting with its status as a Spanish settlement not founded on existing indigenous city-state, but with a significant indigenous population. It was located in a fertile basin on a temperate plateau in the nexus of the key trade triangle of Veracruz–Mexico City–Antequera (Oaxaca). Although there were no encomiendas in Puebla itself, encomenderos with nearby labor grants settled in Puebla. And despite its foundation as a Spanish city, sixteenth-century Puebla had Indians resident in the central core.[106]

Administratively Puebla was far enough away from Mexico City (approximately 160 km or 100 mi) so as not to be under its direct influence. Puebla's Spanish town council (cabildo) had considerable autonomy and was not dominated by encomenderos. The administrative structure of Puebla "may be seen as a subtle expression of royal absolutism, the granting of extensive privileges to a town of commoners, amounting almost to republican self-government, in order to curtail the potential authority of encomenderos and the religious orders, as well as to counterbalance the power of the viceregal capital."[107]

During the "golden century" from its founding in 1531 until the early 1600s, Puebla's agricultural sector flourished, with small-scale Spanish farmers plowing the land for the first time, planting wheat and vaulting Puebla to importance as New Spain's breadbasket, a role assumed by the Bajío (including Querétaro) in the seventeenth century, and Guadalajara in the eighteenth.[108] Puebla's wheat production was the initial element of its prosperity, but it emerged as a manufacturing and commercial center, "serving as the inland port of Mexico's Atlantic trade."[109] Economically, the city received exemptions from the alcabala (sales tax) and almojarifazgo (import/export duties) for its first century (1531–1630), which helped promote commerce.

Puebla built a significant manufacturing sector, mainly in textile production in workshops (obrajes), supplying New Spain and markets as far away as Guatemala and Peru. Transatlantic ties between a particular Spanish town, Brihuega, and Puebla demonstrate the close connection between the two settlements. The take-off for Puebla's manufacturing sector did not simply coincide with immigration from Brihuega but was crucial to "shaping and driving Puebla's economic development, especially in the manufacturing sector."[110] Brihuega immigrants not only came to Mexico with expertise in textile production, but the transplanted briocenses provided capital to create large-scale obrajes. Although obrajes in Brihuega were small-scale enterprises, quite a number of them in Puebla employed up to 100 workers. Supplies of wool, water for fulling mills, and labor (free indigenous, incarcerated Indians, black slaves) were available. Although much of Puebla's textile output was rough cloth, it also produced higher quality dyed cloth with cochineal from Oaxaca and indigo from Guatemala.[111] But by the eighteenth century, Querétaro had displaced Puebla as the mainstay of woolen textile production.[112]

In 1787, Puebla became an intendancy as part of the new administrative structuring of the Bourbon Reforms.

Valley of Mexico

Mexico City dominated the Valley of Mexico, but the valley continued to have dense indigenous populations challenged by growing, increasingly dense Spanish settlement. The Valley of Mexico had many former Indian city-states that became Indian towns in the colonial era. These towns continued to be ruled by indigenous elites under the Spanish crown, with an indigenous governor and a town councils.[113][114] These Indian towns close to the capital were the most desirable ones for encomenderos to hold and for the friars to evangelize.

The capital was provisioned by the indigenous towns, and its labor was available for enterprises that ultimately created a colonial economy. The gradual drying up of the central lake system created more dry land for farming, but the sixteenth-century population declines allowed Spaniards to expand their acquisition of land. One region that retained strong Indian land holding was the southern fresh water area, with important suppliers of fresh produce to the capital. The area was characterized by intensely cultivated chinampas, man-made extensions of cultivable land into the lake system. These chinampa towns retained a strong indigenous character, and Indians continued to hold the majority of that land, despite its closeness to the Spanish capital. A key example is Xochimilco.[115][116][117]

Texcoco in the pre-conquest period was one of the three members of the Aztec Triple Alliance and the cultural center of the empire. It fell on hard times in the colonial period as an economic backwater. Spaniards with any ambition or connections would be lured by the closeness of Mexico City, so that the Spanish presence was minimal and marginal.[118]

Tlaxcala, the major ally of the Spanish against the Aztecs of Tenochtitlan, also became something of a backwater, but like Puebla it did not come under the control of Spanish encomenderos. No elite Spaniards settled there, but like many other Indian towns in the Valley of Mexico, it had an assortment of small-scale merchants, artisans, farmers and ranchers, and textile workshops (obrajes).[119]

North

Since portions of northern New Spain became part of the United States' Southwest region, there has been considerable scholarship on the Spanish borderlands in the north. The motor of the Spanish colonial economy was the extraction of silver. In Bolivia, it was from the single rich mountain of Potosí; but in New Spain, there were two major mining sites, one in Zacatecas, the other in Guanajuato.