Roanoke Colony

The establishment of the Roanoke Colony (/ˈroʊənoʊk/ ROH-ə-nohk) was an attempt by Sir Walter Raleigh to found the first permanent English settlement in North America. The English, led by Sir Humphrey Gilbert, had briefly claimed St. John's, Newfoundland in 1583 as the first English territory in North America at the royal prerogative of Queen Elizabeth I, but Gilbert was lost at sea on his return journey to England.

| Roanoke Colony | |

|---|---|

| Colony of England | |

| 1585–1590 | |

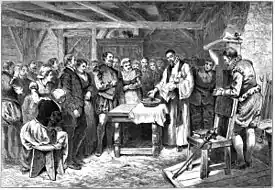

.jpg.webp) The discovery of the abandoned colony, 1590 | |

Location of Roanoke Colony within what is now North Carolina | |

| Population | |

• 1585 | Approx. 108[lower-alpha 1] |

• 1587 | Approx. 112–121[lower-alpha 1] |

| History | |

| Government | |

| Governor | |

• 1585–1586 | Ralph Lane |

• 1587 | John White |

| Historical era | Elizabethan era |

• Established | 1585 |

• Evacuated | 1586 |

• Re-established | 1587 |

• Found abandoned | 1590 |

| Today part of | Dare County, North Carolina, US |

Roanoke colony was founded by governor Ralph Lane in 1585 on Roanoke Island in what is now Dare County, North Carolina, United States.[1](pp 45, 54–59). Lane's colony was troubled by a lack of supplies and poor relations with the local Native Americans. While awaiting a delayed resupply mission by Sir Richard Grenville, Lane abandoned the colony and returned to England with Sir Francis Drake in 1586. Grenville arrived two weeks later and also returned home, leaving behind a small detachment to protect Raleigh's claim.[1](pp 70–77)

Following the failure of the 1585 settlement, a second expedition, led by John White, landed on the same island in 1587, and set up another settlement. Sir Walter Raleigh had sent him to establish the "Cittie of Raleigh" in Chesapeake Bay. That attempt became known as the Lost Colony due to the subsequent unexplained disappearance of its population.[1](pp xx, 89, 276)

During a stop to check on Grenville's men, flagship pilot Simon Fernandes forced White and his colonists to remain on Roanoke.[1](pp 81–82, 89) White returned to England with Fernandes, intending to bring more supplies back for his colony in 1588.[1](pp 93–94) The Anglo-Spanish War delayed White's return to Roanoke until 1590,[1](pp 94, 97) and upon his arrival he found the settlement fortified but abandoned. The cryptic word "CROATOAN" was found carved into the palisade, which White interpreted to mean the colonists had relocated to Croatoan Island. Before White could follow this lead, rough seas and a lost anchor forced the mission to return to England.[1](pp 100–03)

The fate of the approximately 112–121 colonists remains unknown. Speculation that they had assimilated with nearby Native American communities appears in writings as early as 1605.[1](pp 113–114) Investigations by the Jamestown colonists produced reports that the Roanoke settlers had been massacred and stories of people with European features in Native American villages, but no hard evidence was produced.[1](pp 116–125)

Interest in the matter fell into decline until 1834, when George Bancroft published his account of the events in A History of the United States. Bancroft's description of the colonists, particularly White's infant granddaughter Virginia Dare, cast them as foundational figures in American culture, and captured the public imagination.[1](pp 128–130) Despite this renewed interest, modern research has failed to find archaeological evidence to explain the disappearance of the colonists.[1](p 270)

Background

The Outer Banks were explored in 1524 by Giovanni da Verrazzano, who mistook Pamlico Sound for the Pacific Ocean, and concluded that the barrier islands were an isthmus. Recognizing this as a potential shortcut to China, he presented his findings to King Francis I of France and King Henry VIII of England, neither of whom pursued the matter.[1](pp 17–19)

In 1578, Queen Elizabeth I granted a charter to Sir Humphrey Gilbert to explore and colonize territories "unclaimed by Christian kingdoms".[1](pp 27–28) Gilbert had helped to crush the first of the Desmond Rebellions in Ireland's Munster province in the early 1570s. The terms of the charter granted by the Queen were vague, though Gilbert understood it to give him rights to all territory in the New World north of Spanish Florida.[2](p 5) Following Gilbert's death in 1583,[1](p 30) Queen Elizabeth divided the charter between his brother Adrian Gilbert, and his half-brother Sir Walter Raleigh. Adrian's charter gave him the patent on Newfoundland and all points north, where geographers expected to eventually find a long-sought Northwest Passage to Asia. Raleigh was awarded the lands to the south, though much of it was already claimed by Spain.[1](p 33) Richard Hakluyt, however, had by this time taken notice of Verazzano's "isthmus" – located within Raleigh's claim – and was campaigning for England to capitalize on the opportunity.[1](pp 31–33)

Raleigh's charter, issued on March 25, 1584, specified that he needed to establish a colony by 1591, or lose his right to colonization.[2](p 9) He was to "discover, search, find out, and view such remote heathen and barbarous Lands, Countries, and territories ... to have, hold, occupy, and enjoy".[3] It was expected that Raleigh would establish a base from which to send privateers on raids against the treasure fleets of Spain.[4](p 12)

Despite the broad powers granted to Raleigh, he was forbidden to leave the queen's side. Instead of personally leading voyages to the Americas, he delegated the missions to his associates and oversaw operations from London.[1](pp 30, 34)

Amadas–Barlowe expedition

.jpg.webp)

Raleigh quickly arranged an expedition to explore his claim. It departed England on April 27, 1584.[4](p 14) The fleet consisted of two barques; Philip Amadas was captain of the larger vessel, with Simon Fernandes as pilot, while Arthur Barlowe was in command of the other. There are indications that Thomas Harriot and John White may have participated in the voyage, but no records survive which directly confirm their involvement.[2](pp 20–23)

The expedition employed a standard route for transatlantic voyages, sailing south to catch trade winds, which carried them westward to the West Indies, where they collected fresh water. The two ships then sailed north until July 4, when they sighted land at what is now called Cape Fear. The fleet made landfall on July 13 at an inlet north of Hatorask Island, which was named "Port Ferdinando" after Fernandes, who discovered it.[4](p 14)

The Native Americans in the region had likely encountered, or at least observed, Europeans from previous expeditions. The Secotan, who controlled Roanoke Island and the mainland between Albemarle Sound and the Pamlico River, soon made contact with the English and established friendly relations. The Secotan chieftain, Wingina, had recently been injured in a war with the Pamlico, so his brother Granganimeo represented the tribe in his place.[5](pp 44–55)

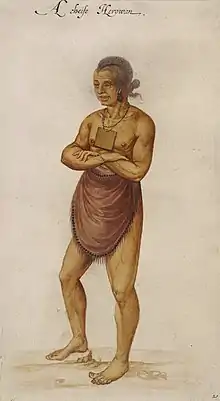

Upon their return to England in the autumn of 1584, Amadas and Barlowe spoke highly of the tribes' hospitality and the strategic location of Roanoke. They brought back two natives: Wanchese, a Secotan, and Manteo, a Croatan whose mother was the chieftain of Croatoan Island.[5](p 56) The expedition's reports described the region as a pleasant and bountiful land, alluding to the Golden Age and the Garden of Eden, although these accounts may have been embellished by Raleigh.[2](pp 29–38)

Queen Elizabeth was impressed with the results of Raleigh's expedition. In 1585, during a ceremony to knight Raleigh, she proclaimed the land granted to him "Virginia" and proclaimed him "Knight Lord and Governor of Virginia". Sir Walter Raleigh proceeded to seek investors to fund a colony.[1](p 45)

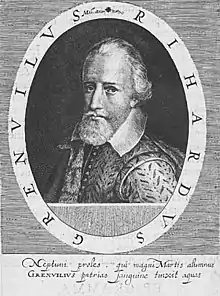

Lane colony

For the first colony in Virginia, Raleigh planned a largely military operation focused on the exploration and evaluation of natural resources. The intended number of colonists was 69, but approximately six hundred men were sent in the voyage, with about half intended to remain at the colony, and were to be followed by a second wave later. Ralph Lane was appointed governor of the colony, and Philip Amadas would serve as admiral, although the fleet commander Sir Richard Grenville led the overall mission.[2](pp 53–56) Civilian attendants included metallurgist Joachim Gans, scientist Thomas Harriot, and artist John White. Manteo and Wanchese, returning home from their visit to England, were also passengers on the voyage.[1](pp 45–49)

Voyage

The fleet consisted of seven ships: The galleass Tiger (Grenville's flagship, with Fernandes as pilot), the flyboat Roebuck (captained by John Clarke), Red Lion (under the command of George Raymond), Elizabeth (captained by Thomas Cavendish), Dorothy (Raleigh's personal ship, perhaps captained by Arthur Barlowe) and two small pinnaces.[2](pp 55–56)

On April 9, 1585, the fleet departed Plymouth, heading south through the Bay of Biscay. A severe storm off the coast of Portugal separated Tiger from the rest of the fleet, and sank one of the pinnaces. Fortunately, Fernandes had advised a plan for such an occurrence, wherein the ships would meet up at Mosquetal,[lower-alpha 2] on the south coast of Puerto Rico. Proceeding alone, Tiger made good speed for the Caribbean, arriving at the rendezvous point on May 11, ahead of the other ships.[2](p 57)

While awaiting the fleet, Grenville established a base camp, where his crew could rest and defend themselves from Spanish forces. Lane's men used the opportunity to practice for building the fortifications that would be needed at the new colony. The crew also set about replacing the lost pinnace, forging nails and sawing local lumber to construct a new ship.[2](p 57) Elizabeth arrived on May 19, shortly after the completion of the fort and pinnace.[2](p 58)[8](p 91)

The remainder of the fleet never arrived at Mosquetal. At least one of the ships encountered difficulties near Jamaica and ran out of supplies, causing its captain to send twenty of his crew ashore. Eventually Roebuck, Red Lion, and Dorothy continued to the Outer Banks, arriving by mid-June. Red Lion left about thirty men on Croatoan Island and departed for privateering in Newfoundland. In the meantime, Grenville established contact with local Spanish authorities, in the hopes of obtaining fresh provisions. When the Spanish failed to deliver the promised supplies, Grenville suspected they would soon attack, so he and his ships abandoned the temporary fort.[2](pp 60, 64)

Grenville captured two Spanish ships in the Mona Passage, adding them to his fleet. Lane took one of these ships to Salinas Bay, where he captured salt mounds collected by the Spanish. Lane again built fortifications to protect his men as they brought the salt aboard. Grenville's ships then sailed to La Isabela, where the Spanish set aside hostilities to trade with the well-armed English fleet. On June 7, Grenville left Hispaniola to continue to the Outer Banks.[2](pp 60–63)

The fleet sailed through an inlet at Wococon Island (near present-day Ocracoke Inlet) on June 26. Tiger struck a shoal, ruining most of the food supplies and nearly destroying the ship.[2](p 63) There are indications that Grenville's fleet was supposed to spend the winter with the new colony, perhaps to immediately begin using it as a privateering base. The wreck of Tiger, however, made that impossible. The remaining provisions could not support a settlement as large as had been planned. Moreover, the shallow inlets of the Outer Banks made the region unsuitable for a base to support large ships. The colony's top priority would now be to locate a better harbour.[4](p 20)

After repairs, Tiger continued with the rest of the fleet to Port Ferdinando, where they reunited with Roebuck and Dorothy. The men left behind by Red Lion were presumably also located during this time.[2](pp 63–64) On August 5, John Arundell took command of one of the faster vessels and set sail for England, to report the expedition's safe arrival.[2](p 75)

Establishment of the colony

The loss of provisions from the Tiger meant that the colony would support far fewer settlers than originally planned. Grenville decided that only about one hundred would stay with Lane, which would be enough to fulfill the colony's objectives until another fleet, scheduled to leave England in June 1585, could deliver a second wave of colonists and supplies.[2](pp 64–67) However, Grenville could not know that this expedition had been redirected to Newfoundland, to alert fishing fleets that the Spanish had begun seizing English commercial vessels in retaliation for attacks by English privateers.[2](p 85) Until a resupply mission could be arranged, Lane's colony would be heavily dependent on the generosity of the natives.[4](p 23)

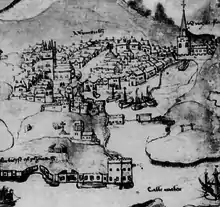

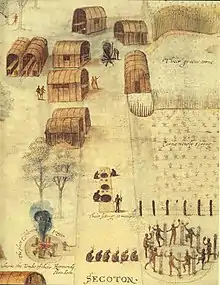

While the Tiger was under repair, Grenville organized an expedition to explore Pamlico Sound and the Secotan villages of Aquascogoc, Pamlico, and Secotan. His party made contact with the locals, presenting Harriot and White with an opportunity to extensively study Native American society.[8](pp 102–110) Although much of their research did not survive the 1586 evacuation of the colony, Harriot's extensive survey of Virginia's inhabitants and natural resources was published in 1588, with engravings of White's illustrations included in the 1590 edition.[2](pp 157–158)[9]

Following this initial exploration, a silver cup was reported missing. Believing the item stolen, Grenville sent Amadas to lead a detachment back to Aquascogoc to demand the return of the missing property. When the villagers did not produce the cup, the English decided that severe retribution was necessary in order to avoid the appearance of weakness. Amadas and his men burnt down the entire town and its crops, sending the natives fleeing.[4](p 72)[10](pp 298–299)

.jpg.webp)

Manteo arranged a meeting for Grenville and Lane with Granganimeo, to provide land for the English settlement on Roanoke Island. Both sides agreed that the island was strategically located for access to the ocean and to avoid detection from Spanish patrols. Lane began construction of a fort on the north side of the island.[1](pp 58–59) There are no surviving renderings of the Roanoke fort, but it was likely similar in structure to the one at Mosquetal.[11](p 27)

Grenville set sail for England aboard the Tiger on August 25, 1585. Days later, in Bermuda, Grenville raided a large Spanish galleon, the Santa Maria de San Vicente, which had become separated from the rest of its fleet.[12](pp 29–34) The merchant ship, which Grenville took back to England as a prize, was loaded with enough treasure to make the entire Roanoke expedition profitable, spurring excitement in Queen Elizabeth's court about Raleigh's colonisation efforts.[5](pp 84–86)

The Roebuck left Roanoke on September 8, 1585, leaving behind one of the pinnaces under the command of Amadas.[2](pp 82, 92) Records indicate 107 men remained with Lane at the colony, for a total population of 108. However, historians disagree as to whether White returned to England with Grenville, or spent the winter at Roanoke despite his absence from the list of colonists.[5](p 259)[2](p 82)

Exploration

Many of the colonists had joined the mission expecting to discover sources of gold and silver. When no such sources were located, these men became dispirited and decided the entire operation was a waste of their time. The English also researched where the local Native Americans obtained their copper, but ultimately never tracked the metal to its origin.[2](pp 93–95)

The colonists spent the autumn of 1585 acquiring corn from the neighboring villages, to augment their limited supplies. The colony apparently obtained enough corn (along with venison, fish, and oysters) to sustain them through the winter.[2](p 91) Little information survives, however, about what transpired at the colony between September 1585 and March 1586, making a full assessment of the winter impossible.[2](p 99) The colonists most likely exhausted their English provisions and American corn by October, and the resulting monotony of their remaining food sources no doubt contributed to the men's low morale.[2](pp 104, 108)

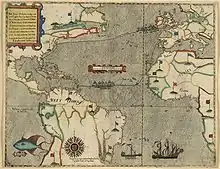

Amadas spent the winter exploring Chesapeake Bay, traveling as far as Cape Henry and the James River. While there his party made contact with the Chesapeake villages of Chesepioc and Skicóak. The Secotans had described Skicóak as the largest city in the region, possibly leading the English to expect something like the wealthy Inca and Aztec kingdoms encountered by the Spanish. Amadas instead found a more modest settlement, although he was impressed with the area's climate and soil quality.[5](pp 87–89) Harriot and Gans explored the Virginia territory, meeting Native American tribes and taking stock of natural resources. During his travels, Harriot and his assistants collected data that would eventually be used to produce White's La Virginea Pars map.[1](pp 63–64)

Although 16th-century science could not explain the phenomenon, Harriot noticed that each town the colonists visited quickly suffered a deadly epidemic, which may have been influenza or smallpox. Some of the Secotan suspected the disease was caused by supernatural forces unleashed by the English. When Wingina fell sick, his own people could not treat him, but he recovered after requesting prayers from the English. Impressed, Wingina asked the colonists to share this power with other stricken communities, which only hastened the spread of disease. The epidemic likely had a severe impact on the fall harvest, at a time when Lane's colony would be heavily dependent on its neighbors to supplement its limited food supply.[1](pp 64–65)[5](pp 89–91)

Hostilities and food shortages

By spring, relations between the Secotan and the colony were strained, most likely due to the colony's over-reliance on Secotan food. The death of Granganimeo, who had been a powerful advocate for the colony, apparently helped to turn Wingina against the English. Wingina changed his name to "Pemisapan" ("one who watches"), suggesting a newly cautious and vigilant policy, and established a new temporary tribal capital on Roanoke Island. The English did not initially recognize these developments represented a threat to their interests.[4](pp 75–76)

In March, Lane consulted Pemisapan about a plan to explore the mainland, beyond Secotan territory. Pemisapan supported the plan and advised Lane that the Chowanoke leader Menatonon was meeting with his allies to plan an attack on the English, and that three thousand warriors had gathered at Choanoac. At the same time, Pemisapan sent word to Menatonon that the English would be coming, ensuring both sides would expect hostilities. When Lane's well-armed party arrived at Choanoac, he found representatives of the Chowanoke, Mangoak, Weapemeoc, and Moratuc. Since this gathering was not planning an attack, Lane caught them by surprise. He easily captured Menatonon, who informed him that it was Pemisapan who had requested the council in the first place.[4](pp 76–77)[13]: 293 [5](pp 93–94)

Menatonon quickly gained Lane's trust by offering information about lucrative opportunities in lands the English had not yet discovered. He described a rich and powerful king to the northeast (presumably the leader of the Powhatan), warning that Lane should bring a considerable force if he sought to make contact. Menatonon also corroborated rumors Lane had heard about a sea just beyond the head of the Roanoke River, apparently confirming English hopes of finding access to the Pacific Ocean. The chief's son Skiko described a place to the west called "Chaunis Temoatan" rich in a valuable metal, which Lane thought could be copper or perhaps even gold.[5](pp 94–97)

Based on this information, Lane envisioned a detailed plan in which his forces would divide into two groups – one traveling north up the Chowan River, the other along the Atlantic coast—to resettle at Chesapeake Bay. However, he decided to defer this mission until the colony received fresh supplies, which Grenville had promised would arrive by Easter.[4](pp 77–78)[14](p 322) In the meantime, Lane ransomed Menatonon and had Skiko sent back to Roanoke as a hostage. He proceeded with forty men for about 100 miles (160 km) up the Roanoke River in search of Chaunis Temotan, but they found only deserted villages and warriors lying in ambush.[5](pp 97–98) Lane had expected the Moratuc to provide provisions for him along his route, but Pemisapan had sent word that the English were hostile and villagers should withdraw from the river with their food.[4](pp 78–79)

Lane and his party returned to the colony shortly after Easter, half-starved and empty-handed. During their absence, rumors had spread that they'd been killed, and Pemisapan had been preparing to withdraw the Secotan from Roanoke Island and leave the colony to starve. There was no sign of Grenville's resupply fleet, which had not yet even left England. According to Lane, Pemisapan was so surprised that Lane returned alive from the Roanoke River mission that he reconsidered his plans. Ensenore, an elder among Pemisapan's council, argued in favor of the English. Later, an envoy for Menatonon informed Lane that the Weapemeoc leader Okisko has pledged fealty to Queen Elizabeth and Sir Walter Raleigh. This shift in the balance of power in the region further deterred Pemisapan from following through on his plans against the colony. He instead ordered his people to sow crops and build fishing weirs for the settlers.[4](pp 80–82)

The renewed accord between the English and the Secotan was short-lived. On April 20 Ensenore died, depriving the colony of its last advocate in Pemisapan's inner circle. Wanchese had risen to become a senior advisor, and his time among the English had convinced him that they were a threat. Pemisapan evacuated the Secotan from Roanoke, destroyed the fishing weirs, and ordered them not to sell food to the English. Left to their own devices, the English had no way to produce enough food to sustain the colony. Lane ordered his men to break up into small groups to forage and beg for food in the Outer Banks and the mainland.[4](p 82)

Lane continued to keep Skiko as a hostage. Although Pemisapan met regularly with Skiko and believed him sympathetic to the anti-English cause, Skiko sought to honor his father's intention of maintaining relations with the colony. Skiko informed Lane that Pemisapan planned to organize a war council meeting on June 10 with various regional powers. With the copper the Secotan had gained from trading with the colony, Pemisapan was able to offer substantial inducements to other tribes to side with him in a final offensive against the English. Oksiko declined to get involved, although individual Weapemeocs were permitted to participate. The plan of attack was to ambush Lane and other key leaders as they slept at the colony, and then signal for a general attack on the rest. Based on this information, Lane sent disinformation to the Secotan indicating that an English fleet had arrived, to force Pemisapan's hand.[4](pp 83–84)

Forced to accelerate his schedule by the possibility of English reinforcements, Pemisapan gathered as many allies as he could for a meeting on May 31 at Dasamongueponke. That evening, Lane attacked the warriors posted at Roanoke, hoping to prevent them from alerting the mainland the following morning. On June 1, Lane, his top officers, and twenty-five men visited Dasamongueponke under the pretense of discussing a Secotan attempt to free Skiko. Once they were admitted into the council, Lane gave the signal for his men to attack. Pemisapan was shot and fled into the woods, but Lane's men caught up to him and brought back his severed head.[4](pp 83–85) The head was impaled outside the colony's fort.[15](p 98)

Evacuation

In June, the colonists made contact with the fleet of Sir Francis Drake, on his way back to England from successful campaigns in Santo Domingo, Cartagena, and St. Augustine.[1](pp 70–71) During these raids, Drake had acquired refugees, slaves, and hardware with the intent of delivering them to Raleigh's colony. Upon learning of the colony's misfortunes, Drake agreed to leave behind four months of supplies and one of his ships, the Francis. However, a hurricane hit the Outer Banks, sweeping the Francis out to sea.[2](pp 134–137)

After the storm, Lane persuaded his men to evacuate the colony, and Drake agreed to take them back to England. Manteo and an associate, Towaye, joined them. Three of Lane's colonists were left behind and never heard from again. Because the colony was abandoned, it is unclear what became of the slaves and refugees Drake had meant to place there. There is no record of them arriving in England with the fleet, and it is possible Drake left them on Roanoke with some of the goods he had previously set aside for Lane.[1](pp 74–75) Drake's fleet, along with Lane's colonists, reached England in July 1586.[1](p 77) Upon arrival, the colonists introduced tobacco, maize, and potatoes to England.[16](p 5)

Grenville's detachment

A single supply ship, sent by Raleigh, arrived at Roanoke just days after Drake evacuated the colony. The crew could not find any trace of the colonists and left. Two weeks later, Grenville's relief fleet finally arrived with a year's worth of supplies and reinforcements of 400 men. Grenville conducted an extensive search and interrogated three natives, one of which finally related an account of the evacuation.[2](pp 140–145) The fleet returned to England, leaving behind a small detachment of fifteen men both to maintain an English presence and to protect Raleigh's claim to Roanoke Island.[2](pp 150–151)

According to the Croatan, this contingent was attacked by an alliance of mainland tribes shortly after Grenville's fleet left. Five of the English were away gathering oysters when two of the attackers, appearing unarmed, approached the encampment and asked to meet with two Englishmen peacefully. One of the Native Americans concealed a wooden sword, which he used to kill an Englishman. Another 28 attackers revealed themselves, but the other Englishman escaped to warn his unit. The natives attacked with flaming arrows, setting fire to the house where the English kept their food stores, and forcing the men to take up whatever arms were handy. A second Englishman was killed; the remaining nine retreated to the shore, and fled the island on their boat. They found their four compatriots returning from the creek, picked them up, and continued into Port Ferdinando. The thirteen survivors were never seen again.[17](pp 364–365)

Lost Colony

_(14784788945).jpg.webp)

Despite the desertion of the Lane colony, Raleigh was persuaded to make another attempt by Hakluyt, Harriot, and White.[1](p 81) However, Roanoke Island would no longer be safe for English settlers, following the hostilities between Lane's men and the Secotan, and the death of Wingina.[1](p 90) Hakluyt recommended Chesapeake Bay as the site for a new colony, in part because he believed the Pacific coast lay just beyond the explored areas of the Virginia territory. On January 7, 1587, Raleigh approved a corporate charter to found "the Cittie of Raleigh" with White as governor and twelve assistants.[1](pp 81–82, 202) Approximately 115 people agreed to join the colony, including White's pregnant daughter Eleanor and her husband Ananias Dare. The colonists were largely middle-class Londoners, perhaps seeking to become landed gentry.[1](pp 84–85) Manteo and Towaye, who had left the Lane colony with Drake's fleet, were also brought along.[1](p 88) This time, the party included women and children, but no organized military force.[1](p 85)

The expedition consisted of three ships: The flagship Lion, captained by White with Fernandes as master and pilot, along with a flyboat (under the command of Edward Spicer) and a full-rigged pinnace (commanded by Edward Stafford). The fleet departed on May 8.[2](pp 268–269)

On July 22, the flagship and pinnace anchored at Croatoan Island. White planned to take forty men aboard the pinnace to Roanoke, where he would consult with the fifteen men stationed there by Grenville, before continuing on to Chesapeake Bay. Once he boarded the pinnace however, a "gentleman" on the flagship representing Fernandes ordered the sailors to leave the colonists on Roanoke.[1](p 89)[8]: 215 [18](p 25)

The following morning, White's party located the site of Lane's colony. The fort had been dismantled, while the houses stood vacant and overgrown with melons. There was no sign that Grenville's men had ever been there except for human bones that White believed were the remains of one of them, killed by Native Americans.[1](p 90)[17](pp 362–363)

Following the arrival of the flyboat on July 25, all of the colonists disembarked.[1](p 90) Shortly thereafter, colonist George Howe was killed by a native while searching alone for crabs in Albemarle Sound.[19](pp 120–123)

White dispatched Stafford to re-establish relations with the Croatan, with the help of Manteo. The Croatan described how a coalition of mainland tribes, led by Wanchese, had attacked Grenville's detachment.[1](p 90–92) The colonists attempted to negotiate a truce through the Croatan, but received no response.[1](p 91)[19](pp 120–123) On August 9, White led a pre-emptive strike on Dasamongueponke, but the enemy (fearing reprisal for the death of Howe) had withdrawn from the village, and the English accidentally attacked Croatan looters. Manteo again smoothed relations between the colonists and the Croatan.[1](p 92) For his service to the colony, Manteo was baptized and named "Lord of Roanoke and Dasamongueponke".[1](p 93)

On August 18, 1587, Eleanor Dare gave birth to a daughter, christened "Virginia" in honor of being "the first Christian born in Virginia". Records indicate Margery Harvye gave birth shortly thereafter, although nothing else is known about her child.[1](p 94)

By the time the fleet was preparing to return to England, the colonists had decided to relocate 50 miles (80 km) up Albemarle Sound.[17](p 360) The colonists persuaded Governor White to return to England to explain the colony's desperate situation and ask for help.[19](pp 120–123) White reluctantly agreed, and departed with the fleet on August 27, 1587.[17](p 369)

1588 relief mission

After a difficult journey, White returned to England on November 5, 1587.[17](p 371) By this time reports of the Spanish Armada mobilizing for an attack had reached London, and Queen Elizabeth had prohibited any able ship from leaving England so that they might participate in the coming battle.[4](pp 119–121)[1](p 94)

During the winter, Grenville was granted a waiver to lead a fleet into the Caribbean to attack the Spanish, and White was permitted to accompany him in a resupply ship. The fleet was set to launch in March 1588, but unfavorable winds kept them in port until Grenville received new orders to stay and defend England. Two of the smaller ships in Grenville's fleet, the Brave and the Roe, were deemed unsuitable for combat, and White was permitted to take them to Roanoke. The ships departed on April 22, but the captains of the ships attempted to capture several Spanish ships on the outward-bound voyage (in order to improve their profits).[2](p 302)[4]: 121–22 On May 6 they were attacked by French mariners (or pirates) near Morocco. Nearly two dozen of the crew were killed, and the supplies bound for Roanoke were looted, leaving the ships to return to England.[1](pp 94–95)

Following the defeat of the Spanish Armada in August, England maintained the ban on shipping in order to focus efforts on organising a Counter Armada to attack Spain in 1589. White would not gain permission to make another resupply attempt until 1590.[1](p 97)

Spanish reconnaissance

The Spanish Empire had been gathering intelligence on the Roanoke colonies since Grenville's capture of Santa Maria de San Vicente in 1585. They feared that the English had established a haven for piracy in North America, but were unable to locate such a base.[1](p 60) They had no cause to assume Lane's colony had been abandoned, or that White's would be placed in the same location.[1]: 88 Indeed, the Spanish greatly overestimated the success of the English in Virginia; rumors suggested the English had discovered a mountain made of diamonds and a route to the Pacific Ocean.[1](p 95)

Following a failed reconnaissance mission in 1587, Philip II of Spain ordered Vicente González to search Chesapeake Bay in 1588. González failed to find anything in Chesapeake, but on the way back he chanced to discover Port Ferdinando along the Outer Banks. The port appeared abandoned. González left without conducting a thorough investigation. Although the Spanish believed González had located the secret English base, the defeat of the Spanish Armada prevented Phillip from immediately ordering an attack upon it. In 1590, a plan was reportedly made to destroy the Roanoke colony and set up a Spanish colony in Chesapeake Bay, but this was merely disinformation designed to misdirect English intelligence.[1](pp 95–98)

1590 relief mission

Eventually, Raleigh arranged passage for White on a privateering expedition organized by John Watts. The fleet of six ships would spend the summer of 1590 raiding Spanish outposts in the Caribbean, but the flagship Hopewell and the Moonlight would split off to take White to his colony.[1](p 97) At the same time, however, Raleigh was in the process of turning the venture over to new investors.[1](p 98)

Hopewell and Moonlight anchored at Croatoan Island on August 12, but there is no indication that White used the time to contact the Croatan for information. On the evening of August 15, while anchored at the north end of Croatoan Island, the crews sighted plumes of smoke on Roanoke Island; the following morning, they investigated another column of smoke on the southern end of Croatoan, but found nothing.[1](p 98) White's landing party spent the next two days attempting to cross Pamlico Sound with considerable difficulty and loss of life. On August 17 they sighted a fire on the north end of Roanoke and rowed towards it, but they reached the island after nightfall and decided not to risk coming ashore. The men spent the night in their anchored boats, singing English songs in hopes that the colonists would hear.[1](pp xvii–xix)

White and the others made landfall on the morning of August 18 (his granddaughter's third birthday). The party found fresh tracks in the sand, but were not contacted by anyone. They also discovered the letters "CRO" carved into a tree. Upon reaching the site of the colony, White noted the area had been fortified with a palisade. Near the entrance of the fencing, the word "CROATOAN" was carved in one of the posts.[1](pp xix) White was certain these two inscriptions meant that the colonists had peacefully relocated to Croatoan Island, since they had agreed in 1587 that the colonists would leave a "secret token" indicating their destination, or a cross pattée as a duress code.[20](p 384)[4](pp 126–127)

Within the palisade, the search party found that houses had been dismantled, and anything that could be carried had been removed. Several large trunks (including three belonging to White, containing the belongings he left behind in 1587) had been dug up and looted. None of the colony's boats could be found along the shore.[1](p 101) The party returned to Hopewell that evening, and plans were made to return to Croatoan the following day. However, Hopewell's anchor cable snapped, leaving the ship with only one working cable and anchor. The search mission could not continue given the considerable risk of shipwreck. Moonlight set off for England, but the crew of Hopewell offered a compromise with White, in which they would spend winter in the Caribbean and return to the Outer Banks in the spring of 1591. This plan fell through, though, when Hopewell was blown off course, forcing them to stop for supplies in the Azores. When the winds prevented landfall there, the ship was again forced to change course for England, arriving on October 24, 1590.[1](pp 102–103)

Investigations into Roanoke

1595–1602: Walter Raleigh

Although White failed to locate his colonists in 1590, his report suggested they had simply relocated and might yet be found alive. However, it served Raleigh's purposes to keep the matter in doubt; so long as the settlers could not be proven dead, he could legally maintain his claim on Virginia.[1](p 111) Nevertheless, a 1594 petition was made to declare Ananias Dare legally dead so that his son, John Dare, could inherit his estate. The petition was granted in 1597.[21](pp 225–226)

During Raleigh's first transatlantic voyage in 1595, he claimed to be in search of his lost colonists, although he later admitted this was disinformation to cover his search for El Dorado. On the return voyage, he sailed past the Outer Banks, and later claimed that weather had prevented him from landing.[1](p 111)

Raleigh later sought to enforce his monopoly on Virginia – based on the potential survival of the Roanoke colonists – when the price of sassafras skyrocketed. He funded a 1602 mission to the Outer Banks, with the stated goal of resuming the search.[1](pp 112–113) Led by Samuel Mace, this expedition differed from previous voyages in that Raleigh bought his own ship and guaranteed the sailors' wages so that they would not be distracted by privateering.[4](p 130) However, the ship's itinerary and manifest indicate that Raleigh's top priority was harvesting sassafras far south of Croatoan Island. By the time Mace approached Hatteras, bad weather prevented them from lingering in the area.[1]: 113 In 1603, Raleigh was implicated in the Main Plot and arrested for treason against King James, effectively ending his Virginia charter.[4](pp 147–148)

1603: Bartholomew Gilbert

There was one final expedition in 1603 led by Bartholomew Gilbert with the intention of finding the Roanoke colonists. Their intended destination was Chesapeake Bay, but bad weather forced them to land in an unspecified location near there. The landing team, including Gilbert himself, was killed by a group of Native Americans for unknown reasons on July 29. The remaining crew were forced to return to England empty-handed.[22](p 50)

1607–1609: John Smith

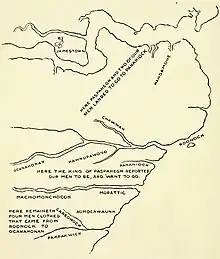

Following the establishment of the Jamestown settlement in 1607, John Smith was captured by the Powhatan and met with both their leader Wahunsenacawh (often referred to as "Chief Powhatan") and his brother Opechanacanough. They described to him a place called "Ocanahonan", where men wore European-style clothing; and "Anone", which featured walled houses. Later, after Smith returned to the colony, he made arrangements with Wowinchopunk, the king of the Paspahegh, to investigate "Panawicke", another place reportedly inhabited by men in European dress. The colony produced a crude map of the region with labels for these villages. The map also featured a place called "Pakrakanick" with a note indicating, "Here remayneth 4 men clothed that came from Roonocok to Ocanahawan."[18](pp 128–133)

In the summer of 1608, Smith sent a letter about this information, along with the map, back to England. The original map is now lost, but a copy was obtained by Pedro de Zúñiga, the Spanish ambassador to England, who passed it on to Philip III of Spain. The copy, now commonly referred to as the "Zúñiga Map", was rediscovered in 1890.[18](pp 129, 131)

Smith planned to explore Pakrakanick, but a dispute with the Paspahegh ended the mission before it could begin. He also dispatched two search parties, possibly to look for the other villages reported to him, with instructions to find "the lost company of Sir Walter Rawley". Neither group could find any sign of the Roanoke colonists living in the area.[18](pp 151, 154)

By May 1609, word had reached England's Royal Council for Virginia that the 1587 colonists had been massacred by Wahunsenacawh.[23](p 17) The source of this allegation is unknown. Machumps, Wahunsenacawh's brother-in-law, is known to have provided information about Virginia, and he had recently arrived in England.[1](p 121) It has been speculated that the same voyage could have also delivered a letter from Smith, although no evidence for this exists.[2](p 365)

Based on this intelligence, as well as Smith's earlier report, the Council drafted orders for the Jamestown colony to relocate. These orders recommended "Ohonahorn" (or "Oconahoen"), near the mouth of the Chowan River, as a new base. Among the purported advantages of this location were proximity to "Riche Copper mines of Ritanoc" and "Peccarecamicke", where four of Raleigh's colonists were supposed to be held by a chieftain named "Gepanocon".[23](pp 16–17) These orders, along with the new acting governor, Thomas Gates, were delayed due to the shipwreck of the Sea Venture at Bermuda. Gates arrived at Jamestown in May 1610, several months into the Starving Time. The crisis may have deterred the colonists from attempting the proposed relocation. An expedition was sent to the Chowan River, but there is no record of its findings.[1](pp 120–122)

1610–1612: William Strachey

William Strachey arrived in Jamestown, along with Gates and Machumps, in May 1610. By 1612, he had returned to England, where he wrote The Historie of Travaile into Virginia Britannia, an overview of the Virginia territory.[1](pp 120–122) He described "Peccarecamek", "Ochanahoen", "Anoeg", and "Ritanoe" in a manner consistent with Smith's map and the Virginia Council's orders to Gates. However, Strachey introduced additional details about "the slaughter at Roanoak".[24](pp 26, 48)

Strachey suggested that the lost colonists had spent twenty years living peacefully with a tribe beyond Powhatan territory. Wahunsenacawh, he claimed, carried out the unprovoked attack at the recommendation of his priests, shortly before the arrival of the Jamestown colonists. Based on this account, seven English – four men, two boys, and one woman – survived the assault and fled up the Chowan River. They later came under the protection of a chieftain named "Eyanoco", for whom they beat copper at "Ritanoe".[24](pp 26, 85–86)

The Historie of Travaile never directly identifies the tribe that supposedly hosted the Roanoke colonists. However, Strachey did describe an attack against the Chesepians, in which Wahunsenacawh's priests warned him that a nation would arise in Chesapeake Bay to threaten his dominion.[24](p 101) It has been inferred that the colonists had relocated to Chesapeake, and both groups were massacred in the same attack.[2](pp 367–368)

Strachey believed that the Powhatan religion was inherently Satanic, and that the priests might literally be in communion with Satan. He advocated for England to facilitate the Powhatans' conversion to Christianity. To that end, he recommended a plan in which King James would show mercy to the Powhatan people for the massacre of the Roanoke colonists, but demand revenge upon the priests.[24](p 83–86) However, the London Company did not publish The Historie of Travaile, which fell into obscurity until 1849.[24](pp xx) There is no indication that any actions were taken against Wahunsenacawh or his priests in retaliation for the alleged massacre.[1](p 123)

1625: Samuel Purchas

After the Powhatan attacked Jamestown in 1622, there was a dramatic shift in English commentary on Native Americans, as writers increasingly questioned their humanity. The London Company sponsored propaganda arguing that the massacre had justified genocidal retaliation, in order to assure potential backers that their investment in the colony would be safe.[25](pp 453–454)[26](p 265)

In this context, Samuel Purchas wrote Virginia's Verger in 1625, asserting England's right to possess and exploit its North American claim. He argued that the natives, as a race, had forfeited their right to the land through bloodshed, citing the 1586 ambush of Grenville's garrison, an alleged attack on White's colonists, and the 1622 Jamestown massacre. Purchas offered no evidence for his claim about the 1587 colony except to state, "Powhatan confessed to Cap. Smith, that hee had beene at their slaughter, and had divers utensills of theirs to shew."[27](pp 228–229)

It is possible Smith related the story of Wahunsenacawh's confession to Purchas, as they are known to have spoken together. Smith's own writings, however, never mention the confession, leaving Purchas' claim to stand alone in what historian Helen Rountree dismisses as "an anti-Indian polemic".[28](pp 21–22) Even if taken at face value, the alleged confession is not persuasive, as Wahunsenacawh might have invented the story in an attempt to intimidate Smith. The European artifacts allegedly offered as "proof" of a raid on the Roanoke colonists could just as easily have been obtained from other sources, such as Ajacán.[29](p 71)

1701–1709: John Lawson

Sea traffic through Roanoke Island fell into decline in the 17th century, owing to the dangerous waters of the Outer Banks.[1](p 126) In 1672, the inlet between Hatorask and Croatoan Islands closed, and the resulting landmass became known as Hatteras Island.[30](p 180)

During John Lawson's 1701–1709 exploration of northern Carolina, he visited Hatteras Island and encountered the Hatteras people.[30](p 171) Although there is evidence of European activity in the Outer Banks throughout the 17th century, Lawson was the first historian to investigate the region since White left in 1590.[30](pp 181–182) Lawson was impressed with the influence of English culture on the Hatteras. They reported that several of their ancestors had been white, and some of them had gray eyes, supporting this claim. Lawson theorized that members of the 1587 colony had assimilated into this community after they lost hope of regaining contact with England.[31](p 62) While visiting Roanoke Island itself, Lawson reported finding the remains of a fort, as well as English coins, firearms, and a powder horn.[1](p 138)

Modern research

Research into the disappearance of the 1587 colonists largely ended with Lawson's 1701 investigation. Renewed interest in the Lost Colony during the 19th century eventually led to a wide range of scholarly analyses.

1800s–1950: Site preservation

The ruins that Lawson encountered in 1701 eventually became a tourist attraction. U.S. President James Monroe visited the site on April 7, 1819. During the 1860s, visitors described the deteriorated "fort" as little more than an earthwork in the shape of a small bastion, and reported holes dug nearby in search of valuable relics. Production of the 1921 silent film The Lost Colony and road development further damaged the site. In the 1930s, J. C. Harrington advocated for the restoration and preservation of the earthwork.[1](pp 135–141) The National Park Service began administration of the area in 1941, designating it Fort Raleigh National Historic Site. In 1950, the earthwork was reconstructed in an effort to restore its original size and shape.[32]

1887–present: Archaeological evidence

Archaeological research on Roanoke Island only began when Talcott Williams discovered a Native American burial site in 1887. He returned in 1895 to excavate the fort, but found nothing of significance. Ivor Noël Hume would later make several compelling finds in the 1990s, but none that could be positively linked to the 1587 colony, as opposed to the 1585 outpost.[1](pp 138–142)

After Hurricane Emily uncovered a number of Native American artifacts along Cape Creek in Buxton, North Carolina, anthropologist David Sutton Phelps Jr. organized an excavation in 1995. Phelps and his team discovered a ring in 1998, which initially appeared to be a gold signet ring bearing the heraldry of a Kendall family in the 16th century.[1](pp 184–189)[33] The find was celebrated as a landmark discovery, but Phelps never published a paper on his findings, and neglected to have the ring properly tested. X-ray analysis in 2017 proved the ring was brass, not gold, and experts could not confirm the alleged connection to Kendall heraldry. The low value and relative anonymity of the ring make it more difficult to conclusively associate with any particular person from the Roanoke voyages, which in turn increases the likelihood that it could have been brought to the New World at a later time.[34][1](pp 199–205)

A significant challenge for archaeologists seeking information about the 1587 colonists is that many common artifacts could plausibly originate from the 1585 colony, or from Native Americans who traded with other European settlements in the same era. Andrew Lawler suggests that an example of a conclusive find would be female remains (since the 1585 colony was exclusively male) buried according to Christian tradition (supine, in an east–west orientation) which can be dated to before 1650 (by which point Europeans would have spread throughout the region).[1](p 182) However, few human remains of any kind have been discovered at sites related to the Lost Colony.[1](p 313)

One possible explanation for the extreme deficiency in archaeological evidence is shoreline erosion. The northern shore of Roanoke Island, where the Lane and White colonies were located, lost 928 feet (283 m) between 1851 and 1970. Extrapolating from this trend back to the 1580s, it is likely that portions of the settlements are now underwater, along with any artifacts or signs of life.[35]

2011–2019: Site X

In November 2011, researchers at the First Colony Foundation noticed two corrective patches on White's 1585 map La Virginea Pars. At their request, the British Museum examined the original map with a light table. One of the patches, at the confluence of the Roanoke and Chowan rivers, was found to cover a symbol representing a fort.[1](pp 163–170)[36]

As the symbol is not to scale, it covers an area on the map representing thousands of acres in Bertie County, North Carolina. However, the location is presumed to be in or near the 16th-century Weapemeoc village of Mettaquem. In 2012, when a team prepared to excavate where the symbol indicated, archaeologist Nicholas Luccketti suggested they name the location "Site X", as in "X marks the spot."[1](pp 176–177)

In an October 2017 statement, the First Colony Foundation reported finding fragments of Tudor pottery and weapons at Site X, and concluded that these indicate a small group of colonists residing peacefully in the area.[37] The challenge for this research is to convincingly rule out the possibility that such finds were brought to the area by the 1585 Lane colony, or the trading post established by Nathaniel Batts in the 1650s.[1](pp 174–182) In 2019, the Foundation announced plans to expand the research into land that has been donated to North Carolina as Salmon Creek State Natural Area.[38][39]

1998: Climate research

In 1998, a team led by climatologist David W. Stahle (of the University of Arkansas) and archaeologist Dennis B. Blanton (of the College of William and Mary) concluded that an extreme drought occurred in Tidewater between 1587 and 1589. Their study measured growth rings from a network of bald cypress trees, producing data ranging from 1185 to 1984. Specifically, 1587 was measured as the worst growing season in the entire 800-year period. The findings were considered consistent with the concerns the Croatan expressed about their food supply.[40]

2005–2019: Genetic analysis

Since 2005, computer scientist Roberta Estes has founded several organisations for DNA analysis and genealogical research. Her interest in the disappearance of the 1587 colony motivated various projects to establish a genetic link between the colonists and potential Native American descendants. Examining autosomal DNA for this purpose is unreliable, as so little of the colonists' genetic material would remain after five or six generations. However, testing of Y chromosomes and mitochondrial DNA is more reliable over large spans of time. The main challenge of this work is to obtain a genetic point of comparison, either from the remains of a Lost Colonist or one of their descendants. While it is conceivable to sequence DNA from 430-year-old bones, there are as yet no bones from the Lost Colony to work with. As of 2019, the project has yet to identify any living descendants, either.[1](pp 311–314)

Hypotheses about the colony's disappearance

It's the ‘Area 51' of colonial history.

Without evidence of the Lost Colony's relocation or destruction, speculation about their fate has endured since the 1590s.[1](p 110) The matter has developed a reputation among academics for attracting obsession and sensationalism with little scholastic benefit.[1](pp 8, 263, 270–71, 321–24)

Conjecture about the Lost Colonists typically begins with the known facts about the case. When White returned to the colony in 1590, there was no sign of battle or withdrawal under duress, although the site was fortified. There were no human remains or graves reported in the area, suggesting that everyone was alive when they left. The "CROATOAN" message is consistent with the agreement with White to indicate where to look for them, suggesting they expected White to look for them and wanted to be found.[1](pp 324–326)

Powhatan attack at Chesapeake Bay

David Beers Quinn concluded that the 1587 colonists sought to relocate to their original destination – Chesapeake Bay – using the pinnace and other small boats to transport themselves and their belongings. A small group would have been stationed at Croatoan, to await White's return and direct him to the transplanted colony. Following White's failure to locate any of the colonists, the main body of the colonists would have quickly assimilated with the Chesepians, while the lookouts on Croatoan would have blended into the Croatan tribe.

Quinn suggested that Samuel Mace's 1602 voyage might have ventured into Chesapeake Bay and kidnapped Powhatans to bring back to England. From there, these abductees would be able to communicate with Thomas Harriot, and might reveal that Europeans were living in the region. Quinn evidently believed circumstances such as these were necessary to explain optimism about the colonists' survival after 1603.

Although Strachey accused Wahunsenacawh of slaughtering the colonists and Chesepians in separate passages, Quinn decided that these events occurred in a single attack on an integrated community, in April 1607. He supposed that Wahunsenacawh could have been seeking revenge for the speculative kidnappings by Mace. In Quinn's estimation, John Smith was the first to learn of the massacre, but for political considerations he quietly reported it directly to King James rather than revealing it in his published writings.[2](pp 341–377) Despite Quinn's reputation on the subject, his peers had reservations about his theory, which relies heavily on the accounts of Strachey and Purchas.[1](p 132)

Integration with local tribes

People have considered the possibility that the missing colonists could have assimilated into nearby Native American tribes since at least 1605.[1](p 113) If this integration was successful, the assimilated colonists would gradually exhaust their European supplies (ammunition, clothing) and discard European culture (language, style of dress, agriculture) as Algonquian lifestyle became more convenient.[1](p 328) Colonial era Europeans observed that many people removed from European society by Native Americans for substantial periods of time – even if captured or enslaved – were reluctant to return; the reverse was seldom true. Therefore, it is reasonable to postulate that, if the colonists were assimilated, they or their descendants would not seek reintegration with subsequent English settlers.[1](p 328)

Most historians today believe this to be the most likely scenario for the surviving colonists' fate.[1](p 329) However, this leaves open the question of which tribe, or tribes, the colonists assimilated into. It is widely accepted that the Croatan were ancestors of the 18th century Hatteras, although evidence of this is circumstantial.[30](p 180)[41] The present-day Roanoke-Hatteras tribe identifies as descendants of both the Croatan and the Lost Colonists by way of the Hatteras.[1](pp 339–344)

Some 17th century maps use the word "Croatoan" to describe locations on the mainland, across Pamlico Sound from Roanoke and Hatteras. By 1700, these areas were associated with the Machapunga.[1](p 334) Oral traditions and legends about the migration of the Croatan through the mainland are prevalent in eastern North Carolina.[4](p 137) For example, the "Legend of the Coharie" in Sampson County was transcribed by Edward M. Bullard in 1950.[18](pp 102–110)

More famously, in the 1880s, state legislator Hamilton McMillan proposed that the Native American community in Robeson County (then considered free people of color) retained surnames and linguistic characteristics from the 1587 colonists.[42] His efforts convinced the North Carolina legislature to confer tribal recognition to the community in 1885, with the new designation of "Croatan". The tribe petitioned to be renamed in 1911, eventually settling on the name Lumbee in 1956.[1](pp 301–307)

Other tribes purportedly linked to the Roanoke colonists include the Catawba and the Coree.[12](p 128) S.A'C. Ashe was convinced that the colonists had relocated westward to the banks of the Chowan River in Bertie County, and Conway Whittle Sams claimed that after being attacked by Wanchese and Wahunsenacawh, they scattered to multiple locations: The Chowan River, and south to the Pamlico and Neuse Rivers.[43](p 233)

Reports of encounters with pale-skinned, blond-haired people among various Native American tribes occur as early as 1607. Although this is frequently attributed to assimilated Lost Colonists, it may be more easily explained by dramatically higher rates of albinism in Native Americans than in people of European descent.[1](p 116) Dawson (2020)[44] proposed that the colonists merged with the Croatoan people; he claims, "They were never lost. It was made up. The mystery is over."[45][46] However, this conclusion has been called into question. Dr. Alain Outlaw, an archaeologist and faculty member at Christopher Newport University, called Dawson's conclusion as "storytelling, not evidence-based information", while archaeologist Nick Luccketti wrote "I have not seen any evidence at Croatoan of artifacts that indicate that Englishmen were living there." In addition, the actual text of Dawson's 2020 book The Lost Colony and Hatteras Island admitted that there was no "smoking gun" of evidence that the colonists had assimilated with the tribe. The book was also not subject to peer review, leaving the question open in spite of the sensationalist headlines that accompanied its publication.[47]

Attempt to return to England

The colonists could have decided to rescue themselves by sailing for England in the pinnace, left behind by the 1587 expedition. If such an effort was made, the ship could have been lost with all hands at sea, accounting for the absence of both the ship and any trace of the colonists.[43](pp 235–236) It is plausible that the colony included sailors qualified to attempt the return voyage. Little is known about the pinnace, but ships of its size were capable of making the trip, although they typically did so alongside other vessels.[18](pp 83–84)

The colonists may have feared that a standard route across the Atlantic Ocean, with a stop in the Caribbean, would risk a Spanish attack. Nevertheless, it was feasible for the colonists to attempt a direct course to England. In 1563, French settlers at the failed Charlesfort colony built a crude boat and successfully (albeit desperately) returned to Europe. Alternatively, the Roanoke colonists could have sailed north along the coast, in the hopes of making contact with English fishing fleets in the Gulf of Maine.[18](pp 85–89)

The pinnace would not have been large enough to carry all of the colonists. Additionally, the provisions needed for a transatlantic voyage would further restrict the number of passengers. The colonists may have possessed the resources to construct another seaworthy vessel, using local lumber and spare parts from the pinnace. Considering the ships were built by survivors of the 1609 Sea Venture shipwreck, it is at least possible that the Lost Colonists could produce a second ship that, with the pinnace, could transport most of their party.[18](pp 84–90) Even in these ideal conditions, however, at least some colonists would remain in Virginia, leaving open the question of what became of them.[43](p 244)

Conspiracy against Raleigh

Anthropologist Lee Miller proposed that Sir Francis Walsingham, Simon Fernandes, Edward Strafford, and others participated in a conspiracy to maroon the 1587 colonists at Roanoke. The purpose of this plot, she argued, was to undermine Walter Raleigh, whose activities supposedly interfered with Walsingham's covert machinations to make England a Protestant world power, at the expense of Spain and other Catholic nations. This conspiracy would have impeded Raleigh and White from dispatching a relief mission until Walsingham's death in 1590.[48](pp 168–204) Miller also suggested that the colonists may have been separatists, seeking refuge in America from religious persecution in England. Raleigh expressed sympathy for the separatists, while Walsingham considered them a threat to be eliminated.[48](pp 43–50, 316)

According to Miller, the colonists split up, with a small group relocating to Croatoan while the main body sought shelter with the Chowanoke. The colonists, however, would have quickly spread European diseases among their hosts, decimating the Chowanoke and thereby destabilising the balance of power in the region. From there Miller reasoned that the Chowanoke were attacked, with the survivors taken captive, by the "Mandoag", a powerful nation to the west that the Jamestown colonists only knew from the vague accounts of their neighbors.[48](pp 227–237) She concluded that the "Mandoag" were the Eno, who traded the captured surviving Lost Colonists as slaves, dispersing them throughout the region.[48](pp 255–260)

Miller's theory has been challenged based on Walsingham's considerable financial support of Raleigh's expeditions, and the willingness of Fernandes to bring John White back to England, instead of abandoning him with the other colonists.[18](pp 29–30)

Secret operation at Beechland

Local legends in Dare County refer to an abandoned settlement called "Beechland", located within what is now the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge. The area has had reports of small coffins, some with Christian markings, encouraging speculation of a link to the Lost Colony.[12](pp 127–128) Based on these legends, engineer Phillip McMullan and amateur archaeologist Fred Willard concluded that Walter Raleigh dispatched the 1587 colonists to harvest sassafras along the Alligator River. All records suggesting the colony's intended destination was Chesapeake Bay, and that England had lost contact with the colony, were supposedly falsified to conceal the operation from Spanish operatives and other potential competitors.[49][1](p 263)

According to McMullan,[49] Raleigh quietly re-established contact with the colony by 1597, and his sassafras expeditions were simply picking up the colonists' harvests. In this view, the colony was not truly abandoned until the secret of the colony's location died with Raleigh in 1618. After that point, McMullan argued, the colonists would have begun to assimilate with the Croatan at Beechland.[49]

This hypothesis largely depends upon oral traditions and unsubstantiated reports about Beechland, as well as a 1651 map that depicts a sassafras tree near the Alligator River. A significant problem with the hypothesis is that Raleigh supposedly planned a sassafras farm in 1587, to capitalize on a dramatic increase in crop prices, so that he could quickly compensate for the great expense of the failed 1585 colony.[49] The proposed financial motivation overlooks the fact that Richard Grenville's privateering recovered the cost of the 1585 expedition.[1](p 60) Additionally, sassafras prices did not skyrocket in value until the late 1590s, well after the establishment of the 1587 colony.[1](p 112)

Spanish attack

P. Green, while collecting material for a 1937 stage play, noticed that Spanish records from the period contained abundant references to Raleigh and his settlements.[50](pp 63–64) Spanish forces knew of English plans to establish a new Virginia base in 1587, and were searching for it before White's colonists had even arrived. The Spanish Empire had included most of North America in their Florida claim, and did not recognize England's right to colonize Roanoke or Chesapeake Bay. Given the Spanish sack of Fort Caroline in 1565, the colonists likely recognized the threat they represented.[lower-alpha 3][18](pp 33–34) However, the Spanish were still searching for the colony in Chesapeake Bay as late as 1600, suggesting that they also were unaware of its fate.[43](p 238)

CORA tree

In 2006, writer Scott Dawson proposed that a Southern live oak tree on Hatteras Island, which bears the faint inscription "CORA" in its bark, might be connected to the Lost Colony. The CORA tree had already been the subject of local legends, most notably a story about a witch named "Cora" that was popularized in a 1989 book by C.H. Whedbee. Nevertheless, Dawson argued that the inscription might represent another message from the colonists, similar to the "CROATOAN" inscription at Roanoke.[18](pp 71–72) If so, "CORA" might indicate that the colonists left Croatoan Island to settle with the Coree (also known as the Coranine) on the mainland, near Lake Mattamuskeet.[12](p 128)

A 2009 study to determine the age of the CORA tree was inconclusive. Damage to the tree, caused by lightning and decay, has made it impossible to obtain a valid core sample for tree-ring dating. Even if the tree dates back to the 16th century, establishing the age of the inscription would be another matter.[18](pp 72–73)

Dare Stones

From 1937–1941, a series of inscribed stones were discovered that were claimed to have been written by Eleanor Dare, mother of Virginia Dare. They told of the travelings of the colonists and their ultimate deaths. Most historians today believe that they are a fraud because investigations linked all but one to stonecutter Bill Eberhardt.[51] The first one is sometimes regarded as different from the rest, based on a linguistic and chemical analysis, and as possibly genuine.[52]

In popular culture

Raleigh was publicly criticized for his apparent indifference to the fate of the 1587 colony, most notably by Sir Francis Bacon.[1](p 111) "It is the sinfullest thing in the world," Bacon wrote in 1597, "to forsake or destitute a plantation once in forwardness; for besides the dishonour, it is the guiltiness of blood of many commiserable persons."[53] The 1605 comedy Eastward Hoe features characters bound for Virginia, who are assured that the lost colonists have by that time intermarried with Native Americans to give rise to "a whole country of English".[54]

United States historians largely overlooked or minimized the importance of the Roanoke settlements until 1834, when George Bancroft lionized the 1587 colonists in A History of the United States.[1](pp 127–128) Bancroft emphasized the nobility of Walter Raleigh, the treachery of Simon Fernandes, the threat of the Secotan, the courage of the colonists, and the uncanny tragedy of their loss.[1](pp 128–129)[55](pp 117–123) He was the first since John White to write about Virginia Dare, calling attention to her status as the first English child born on what would become US soil, and the pioneering spirit exhibited by her name.[1](p 129)[55](p 122) The account captivated the American public. As Andrew Lawler puts it, "The country was hungry for an origin story more enchanting than the spoiled fops of Jamestown or the straitlaced Puritans of Plymouth... Roanoke, with its knights and villains and its brave but outnumbered few facing an alien culture, provided all the elements for a national myth."[1](p 129)

The first known use of the phrase "The Lost Colony" to describe the 1587 Roanoke settlement was by Eliza Lanesford Cushing in an 1837 historical romance, Virginia Dare; or, the Lost Colony.[1](p 276)[56] Cushing also appears to be the first to cast White's granddaughter being reared by Native Americans, following the massacre of the other colonists, and to focus on her adventures as a beautiful young woman.[1](p 277) In 1840, Cornelia Tuthill published a similar story, introducing the conceit of Virginia wearing the skin of a white doe.[1](p 278)[57] An 1861 Raleigh Register serial by Mary Mason employs the premise of Virginia being magically transformed into a white doe.[1](p 280)[58] The same concept was used more famously in The White Doe, a 1901 poem by Sallie Southall Cotten.[1](pp 283–284)[59]

The popularity of the Lost Colony and Virginia Dare in the 19th and early 20th centuries coincided with American controversies about rising numbers of Catholic and non-British immigrants, as well as the treatment of African Americans and Native Americans.[1](p 276) Both the colony and the adult Virginia character were embraced as symbols of white nationalism.[1](p 281) Even when Virginia Dare was invoked in the name of women's suffrage in the 1920s, it was to persuade North Carolina legislators that granting white women the vote would assure white supremacy.[1](p 281) By the 1930s this racist connotation apparently subsided, although the VDARE organisation, founded in 1999, has been denounced for promoting white supremacists.[1](pp 290–291)

Celebrations of the Lost Colony, on Virginia Dare's birthday, have been organized on Roanoke Island since the 1880s.[1](p 294) To expand the tourist attraction, Paul Green's play The Lost Colony opened in 1937, and remains in production today. President Franklin D. Roosevelt attended the play on August 18, 1937 – Virginia Dare's 350th birthday.[1](pp 141, 347)

Bereft of its full context, the colonists' sparse message of "CROATOAN" has taken on a paranormal quality in Harlan Ellison's 1975 short story Croatoan and Stephen King's 1999 television miniseries Storm of the Century, as well as being a human-like villain (portrayed by William Shatner) in the 5th series of Stephen King's Haven, which is based on the Stephen King's novel The Colorado Kid. Croatoan, coincidentally, was the murderer of the Colorado kid in Haven and Croatoan also appears in the 2005 television series Supernatural.[1](p 185)[60] The 1994 graphic novel Batman-Spawn: War Devil states that "Croatoan" was the name of a powerful demon who, in the 20th century, attempts to sacrifice the entirety of Gotham City to Satan.[61]

In the 1999 comic fiction book 100 Bullets, an organisation of powerful European families known as The Trust massacred the Roanoke Colony as a warning to the kings of Europe, as they wished to claim the riches of the New World for themselves. The word "Croatoa" is used to "reactivate" agents of The Minutemen, an organisation which polices The Trust, who have been placed in hiding with their memories of The Minutemen suppressed.

In the 2015 novel The Last American Vampire, the colonists are the victims of a vampire named "Crowley"; the inscription "CRO" was thus an incomplete attempt to implicate him.[60]

The 2011 American Horror Story episode "Birth" relates a fictional legend in which the Lost Colonists mysteriously died, and their ghosts haunted the local Native Americans until a tribal elder banished them with the word "Croatoan".[62] This premise is expanded upon in the sixth season of the series, American Horror Story: Roanoke, which presents a series of fictional television programs documenting encounters with the ghost colonists.[63] The leader of the undead colonists, "The Butcher", is depicted as John White's wife Thomasin, although there is no historical evidence that she was one of the colonists.[64][65]

See also

- List of people who disappeared mysteriously: pre-1970

- Timeline of the colonisation of North America

- Other failed North American colonies:

- Popham Colony

- Charlesbourg-Royal

- Fort Caroline

- Charlesfort-Santa Elena Site

- Ajacán Mission

Notes

- The precise number of colonists is disputed. See List of colonists at Roanoke.

- The English called this place "Bay of Muskito" (Mosquito Bay) while the Spanish called it "Mosquetal".[6](pp 181, 740) the precise location of which is uncertain. David Beers Quinn identified Mosquetal as Tallaboa Bay in 1955, but he later concurred with Samuel Eliot Morison's 1971 conclusion that the name referred to Guayanilla Bay,[7](pp 633–635, 655)[2](pp 57, 430–31)

- Green's play ends with the colonists leaving Roanoke Island to evade an approaching Spanish ship, leaving the audience to wonder if the Spanish found them.[1](p 353)

References

- Lawler, Andrew (2018). The Secret Token: Myth, Obsession, and the Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0385542012.

- Quinn, David B. (1985). Set Fair for Roanoke: Voyages and Colonies, 1584–1606. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4123-5. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- Elizabeth I (1600). "The letters patents, granted by the Queenes Majestie to M. Walter Ralegh now Knight, for the discouering and planting of new lands and Countries, to continue the space of 6. yeeres and no more.". In Hakluyt, Richard; Goldsmid, Edmund (eds.). The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques, And Discoveries of the English Nation. Vol. XIII: America. Part II. Edinburgh: E. & G. Goldsmid (published 1889). pp. 276–282. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- Kupperman, Karen Ordahl (2007). Roanoke: The Abandoned Colony (2nd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-5263-0.

- Horn, James (2010). A Kingdom Strange: The Brief and Tragic History of the Lost Colony of Roanoke. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00485-0.

- Quinn, David Beers, ed. (1955). The Roanoke Voyages, 1584–1590: Documents to illustrate the English Voyages to North America under the Patent granted to Walter Raleigh in 1584. Farnham: Ashgate (published 2010). ISBN 978-1-4094-1709-5.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1971). The European Discovery of America. Vol. 1: The Northern Voyages, A.D. 500–1600. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-501377-8.

- Milton, Giles (2001). Big Chief Elizabeth: The Adventures and Fate of the First English Colonists in America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-312-42018-5. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- Harriot, Thomas (1590). A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia, of the commodities and of the nature and manners of the naturall inhabitants. Discouered by the English colony there seated by Sir Richard Greinuile Knight in the yeere 1585. Which Remained Vnder the gouernement of twelue monethes, at the speciall charge and direction of the Honourable Sir Walter Raleigh Knight lord Warden of the stanneries Who therein hath beene fauoured and authorized by her Maiestie and her letters patents. Frankfurt: Johannes Wechel. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- Anon. (1600). "The voiage made by Sir Richard Greenuile, for Sir Walter Ralegh, to Virginia, in the yeere 1585.". In Hakluyt, Richard; Goldsmid, Edmund (eds.). The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques, And Discoveries of the English Nation. Vol. XIII: America. Part II. Edinburgh: E. & G. Goldsmid (published 1889). pp. 293–300. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- Harrington, Jean Carl (1962). Search for the Cittie of Raleigh: Archeological Excavations at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, North Carolina. Washington, DC: National Park Service, US Department of the Interior. Retrieved September 20, 2019.

- Gabriel-Powell, Andy (2016). Richard Grenville and the Lost Colony of Roanoke. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-6571-9.

- Donegan, Kathleen (2013). "What Happened in Roanoke: Ralph Lane's Narrative Incursion". Early American Literature. University of North Carolina Press. 48 (2): 285–314. doi:10.1353/eal.2013.0032. JSTOR 24476352. S2CID 162342657.

- Lane, Ralph (1600). "An account of the particularities of the imployments of the English men left in Virginia by Richard Greeneuill vnder the charge of Master Ralph Lane Generall of the same, from the 17. of August 1585. vntil the 18. of Iune 1586. at which time they departed the Countrey; sent and directed to Sir Walter Ralegh.". In Hakluyt, Richard; Goldsmid, Edmund (eds.). The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques, And Discoveries of the English Nation. Vol. XIII: America. Part II. Edinburgh: E. & G. Goldsmid (published 1889). pp. 302–322. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- Oberg, Michael Leroy (2008). The Head in Edward Nugent's Hand: Roanoke's Forgotten Indians. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. ISBN 978-0-8122-4031-3. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- Chandler, J. A. C. (1909). "The Beginnings of Virginia, 1584–1624". In Chandler, J. A. C. (ed.). The South in the Building of the Nation: A History of the Southern States Designed to Record the South's Part in Making the American Nation; to Portray the Character and Genius, to Chronicle the Achievements and Progress and to Illustrate the Life and Traditions of the Southern People. Vol. I: History of the States. Richmond, Virginia: The Southern Historical Publication Society. pp. 1–23. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- White, John (1600). "The fourth voyage made to Virginia with three ships, in yere 1587. Wherein was transported the second Colonie.". In Hakluyt, Richard; Goldsmid, Edmund (eds.). The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques, And Discoveries of the English Nation. Vol. XIII: America. Part II. Edinburgh: E. & G. Goldsmid (published 1889). pp. 358–373. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- Fullam, Brandon (2017). The Lost Colony of Roanoke: New Perspectives. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4766-6786-7.

- Grizzard, Frank E.; Smith, D. Boyd (2007). Jamestown Colony: A Political, Social, and Cultural History. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-637-4. Retrieved October 2, 2019.