Dalek

The Daleks (/ˈdɑːlɛks/ (![]() listen) DAH-leks) are a fictional extraterrestrial race of mutants principally portrayed in the British science fiction television programme Doctor Who. They were conceived by writer Terry Nation and first appeared in the 1963 Doctor Who serial The Daleks, in shells designed by Raymond Cusick.

listen) DAH-leks) are a fictional extraterrestrial race of mutants principally portrayed in the British science fiction television programme Doctor Who. They were conceived by writer Terry Nation and first appeared in the 1963 Doctor Who serial The Daleks, in shells designed by Raymond Cusick.

| Dalek | |

|---|---|

| Doctor Who race | |

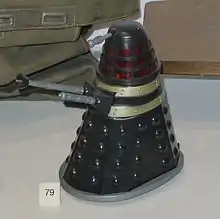

Time War Dalek model on display at the BBC Shop in London, demonstrating their design in the revived series | |

| First appearance | The Daleks (1963) |

| Created by | Terry Nation |

| In-universe information | |

| Created by | Davros |

| Home world | Skaro |

| Type | Kaled mutants in Mark III Travel Machines |

| Affiliation |

|

Drawing inspiration from the Nazis, Nation portrayed the Daleks as violent, merciless and pitiless cyborg aliens who demand total conformity to their will,[1] and are bent on the conquest of the universe and the extermination of what they see as inferior races. Collectively, they are the greatest enemies of Doctor Who's protagonist, the Time Lord known as "the Doctor". During the second year of the original Doctor Who programme (1963–1989), the Daleks developed their own form of time travel. In the beginning of the second Doctor Who TV series that debuted in 2005, it was established that the Daleks had engaged in a Time War against the Time Lords that affected much of the universe and altered parts of history.

In the programme's narrative, the planet Skaro suffered a thousand-year war between two societies: the Kaleds and the Thals. During this time-period, many natives of Skaro became badly mutated by fallout from nuclear weapons and chemical warfare. The Kaled government believed in genetic purity and swore to "exterminate the Thals" for being inferior. Believing his own society was becoming weak and that it was his duty to create a new master race from the ashes of his people, the Kaled scientist Davros genetically modified several Kaleds into squid-like life-forms he called Daleks, removing "weaknesses" such as mercy and sympathy while increasing aggression and survival-instinct. He then integrated them with tank-like robotic shells equipped with advanced technology based on the same life-support system he himself used since being burned and blinded by a nuclear attack. His creations became intent on dominating the universe by enslaving or purging all "inferior" non-Dalek life.

The Daleks are the show's most popular and famous villains and their returns to the series over the decades have often gained media attention. Their frequent declaration "Exterminate!" has become common usage. Contrary to popular belief, the Daleks are not contractually required to appear in every season.[2]

Creation

The Daleks were created by Terry Nation and designed by the BBC designer Raymond Cusick.[3] They were introduced in December 1963 in the second Doctor Who serial, colloquially known as The Daleks.[4] They became an immediate and huge hit with viewers, featuring in many subsequent serials and, in the 1960s, two films. They have become as synonymous with Doctor Who as the Doctor himself, and their behaviour and catchphrases are now part of British popular culture. "Hiding behind the sofa whenever the Daleks appear" has been cited as an element of British cultural identity,[5] and a 2008 survey indicated that nine out of ten British children were able to identify a Dalek correctly.[6] In 1999 a Dalek photographed by Lord Snowdon appeared on a postage stamp celebrating British popular culture.[7] In 2010, readers of science fiction magazine SFX voted the Dalek as the all-time greatest monster, beating competition including Japanese movie monster Godzilla and J. R. R. Tolkien's Gollum, of The Lord of the Rings.[8]

Entry into popular culture

As early as one year after first appearing on Doctor Who, the Daleks had become popular enough to be recognized even by non-viewers. In December 1964 editorial cartoonist Leslie Gilbert Illingworth published a cartoon in the Daily Mail captioned "THE DEGAULLEK", caricaturing French President Charles de Gaulle arriving at a NATO meeting as a Dalek with de Gaulle's prominent nose.[9]

The word "Dalek" has entered major dictionaries, including the Oxford English Dictionary, which defines "Dalek" as "a type of robot appearing in 'Dr. Who' [sic], a B.B.C. Television science-fiction programme; hence used allusively."[10] English-speakers sometimes use the term metaphorically to describe people, usually authority figures, who act like robots unable to break from their programming. For example, John Birt, the Director-General of the BBC from 1992 to 2000, was called a "croak-voiced Dalek" by playwright Dennis Potter in the MacTaggart Lecture at the 1993 Edinburgh Television Festival.[11]

Physical characteristics

Externally Daleks resemble human-sized pepper pots[3] with a single mechanical eyestalk mounted on a rotating dome, a gun-mount containing an energy-weapon ("gunstick" or "death ray") resembling an egg-whisk, and a telescopic manipulator arm usually tipped by an appendage resembling a sink-plunger. Daleks have been known to use their plungers to interface with technology,[12] crush a man's skull by suction,[12] measure the intelligence of a subject,[13] and extract information from a man's mind.[14] Dalek casings are made of a bonded polycarbide material called "Dalekanium" by a member of the human resistance in The Dalek Invasion of Earth and the Dalek comics, as well as by the Cult of Skaro in "Daleks in Manhattan."[13][15]

The lower half of a Dalek's shell is covered with hemispherical protrusions, or 'Dalek-bumps', which are shown in the episode "Dalek" to be spheres embedded in the casing.[12] Both the BBC-licensed Dalek Book (1964) and The Doctor Who Technical Manual (1983) describe these items as being part of a sensory array,[16] while in the 2005 series episode "Dalek" they are integral to a Dalek's forcefield mechanism,[12] which evaporates most bullets and resists most types of energy weapons. The forcefield seems to be concentrated around the Dalek's midsection (where the mutant is located), as normally ineffective firepower can be concentrated on the eyestalk to blind a Dalek. In 2019 episode "Resolution" the bumps give way to reveal missile launchers capable of wiping out a military tank with ease. Daleks have a very limited visual field, with no peripheral sight at all, and are relatively easy to hide from in fairly exposed places.[17] Their own energy weapons are capable of destroying them.[18] Their weapons fire a beam that has electrical tendencies, is capable of propagating through water, and may be a form of plasma or electrolaser. The eyepiece is a Dalek's most vulnerable spot; impairing its vision often leads to a blind, panicked firing of its weapon while exclaiming "My vision is impaired; I cannot see!" Russell T Davies subverted the catchphrase in his 2008 episode "The Stolen Earth", in which a Dalek vaporises a paintball that has blocked its vision while proclaiming, "My vision is not impaired!"[19][20]

The creature inside the mechanical casing is soft and repulsive in appearance, and vicious in temperament. The first-ever glimpse of a Dalek mutant, in The Daleks, was a claw peeking out from under a Thal cloak after it had been removed from its casing.[21] The mutants' actual appearance has varied, but often adheres to the Doctor's description of the species in Remembrance of the Daleks as "little green blobs in bonded polycarbide armour".[22] In Resurrection of the Daleks a Dalek creature, separated from its casing, attacks and severely injures a human soldier;[23] in Remembrance of the Daleks there are two Dalek factions (Imperial and Renegade), and the creatures inside have a different appearance in each case, one resembling the amorphous creature from Resurrection, the other the crab-like creature from the original Dalek serial. As the creature inside is rarely seen on screen there is a common misconception that Daleks are wholly mechanical robots.[24] In the new series Daleks are retconned to be mollusc-like in appearance, with small tentacles, one or two eyes, and an exposed brain.[12] In the new series, a Dalek creature separated from its casing is shown capable of inserting a tentacle into the back of a human's neck and controlling them.[25]

Daleks' voices are electronic; when out of its casing the mutant is able only to squeak.[23] Once the mutant is removed the casing itself can be entered and operated by humanoids; for example, in The Daleks, Ian Chesterton (William Russell) enters a Dalek shell to masquerade as a guard as part of an escape plan.[21]

For many years it was assumed that, due to their design and gliding motion, Daleks were unable to climb stairs, and that this provided a simple way of escaping them. A cartoon from Punch pictured a group of Daleks at the foot of a flight of stairs with the caption, "Well, this certainly buggers our plan to conquer the Universe".[26] In a scene from the serial Destiny of the Daleks, the Doctor and companions escape from Dalek pursuers by climbing into a ceiling duct. The Fourth Doctor calls down, "If you're supposed to be the superior race of the universe, why don't you try climbing after us?"[27] The Daleks generally make up for their lack of mobility with overwhelming firepower; a joke among Doctor Who fans is that "Real Daleks don't climb stairs; they level the building."[28] Dalek mobility has improved over the history of the series: in their first appearance, in The Daleks, they were capable of movement only on the conductive metal floors of their city; in The Dalek Invasion of Earth a Dalek emerges from the waters of the River Thames, indicating not only that they had become freely mobile, but that they are amphibious;[29] Planet of the Daleks showed that they could ascend a vertical shaft by means of an external anti-gravity mat placed on the floor; Revelation of the Daleks showed Davros in his life-support chair and one of his Daleks hovering and Remembrance of the Daleks depicted them as capable of hovering up a flight of stairs.[30] Despite this, journalists covering the series frequently refer to the Daleks' supposed inability to climb stairs; characters escaping up a flight of stairs in the 2005 episode "Dalek" made the same joke and were shocked when the Dalek began to hover up the stairs after uttering the phrase "ELEVATE", in a similar manner to their normal phrase "EXTERMINATE".[12] The new series depicts the Daleks as fully capable of flight, even space flight.[17]

Prop details

The non-humanoid shape of the Dalek did much to enhance the creatures' sense of menace.[31] A lack of familiar reference points differentiated them from the traditional "bug-eyed monster" of science fiction, which Doctor Who creator Sydney Newman had wanted the show to avoid.[32] The unsettling Dalek form, coupled with their alien voices, made many believe that the props were wholly mechanical and operated by remote control.[33]

The Daleks were actually controlled from inside by short operators,[34] who had to manipulate their eyestalks, domes and arms, as well as flashing the lights on their heads in sync with the actors supplying their voices. The Dalek cases were built in two pieces; an operator would step into the lower section and then the top would be secured. The operators looked out between the cylindrical louvres just beneath the dome, which were lined with mesh to conceal their faces.[34]

In addition to being hot and cramped, the Dalek casings also muffled external sounds, making it difficult for operators to hear the director or dialogue. John Scott Martin, a Dalek operator from the original series, said that Dalek operation was a challenge: "You had to have about six hands: one to do the eyestalk, one to do the lights, one for the gun, another for the smoke canister underneath, yet another for the sink plunger. If you were related to an octopus then it helped."[35]

For Doctor Who's 21st-century revival the Dalek casings retain the same overall shape and dimensional proportions of previous Daleks, although many details have been redesigned to give the Dalek a heavier and more solid look.[36] Changes include a larger, more pointed base; a glowing eyepiece; an all-over metallic-brass finish (specified by Davies); thicker, nailed strips on the "neck" section; a housing for the eyestalk pivot; and significantly larger dome lights.[36] The new prop made its on-screen debut in the 2005 episode "Dalek".[36] These Dalek casings use a short operator inside the housing while the 'head' and eyestalk are operated via remote control. A third person, Nicholas Briggs, supplies the voice in their various appearances.[37] In the 2010 season, a new, larger model appeared in several colours representing different parts of the Dalek command hierarchy.

Movement

Terry Nation's original plan was for the Daleks to glide across the floor. Early versions of the Daleks rolled on nylon castors, propelled by the operator's feet. Although castors were adequate for the Daleks' debut serial, which was shot entirely at the BBC's Lime Grove Studios, for The Dalek Invasion of Earth Terry Nation wanted the Daleks to be filmed on the streets of London. To enable the Daleks to travel smoothly on location, designer Spencer Chapman built the new Dalek shells around miniature tricycles with sturdier wheels, which were hidden by enlarged fenders fitted below the original base.[38] The uneven flagstones of Central London caused the Daleks to rattle as they moved and it was not possible to remove this noise from the final soundtrack. A small parabolic dish was added to the rear of the prop's casing to explain why these Daleks, unlike the ones in their first serial, were not dependent on static electricity drawn up from the floors of the Dalek city for their motive power.[35]

Later versions of the prop had more efficient wheels and were once again simply propelled by the seated operators' feet, but they remained so heavy that when going up ramps they often had to be pushed by stagehands out of camera shot. The difficulty of operating all the prop's parts at once contributed to the occasionally jerky Dalek movements.[35] This problem has largely been eradicated with the advent of the "new series" version, as its remotely controlled dome and eyestalk allow the operator to concentrate on the smooth movement of the Dalek and its arms.[39]

Voices

The staccato delivery, harsh tone and rising inflection of the Dalek voice were initially developed by two voice actors, Peter Hawkins and David Graham, who varied the pitch and speed of the lines according to the emotion needed. Their voices were further processed electronically by Brian Hodgson at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. The sound-processing devices used have varied over the decades. In 1963 Hodgson and his colleagues used equalisation to boost the mid-range of the actor's voice, then subjected it to ring modulation with a 30 Hz sine wave. The distinctive harsh, grating vocal timbre this produced has remained the pattern for all Dalek voices since (with the exception of those in the 1985 serial Revelation of the Daleks, for which the director, Graeme Harper, deliberately used less distortion).[40]

Besides Hawkins and Graham, other voice actors for the Daleks have included Roy Skelton, who first voiced the Daleks in the 1967 story The Evil of the Daleks and provided voices for five additional Dalek serials including Planet of the Daleks,[41] and for the one-off anniversary special The Five Doctors. Michael Wisher, the actor who originated the role of Dalek creator Davros in Genesis of the Daleks, provided Dalek voices for that same story, as well as for Frontier in Space, Planet of the Daleks, and Death to the Daleks. Other Dalek voice actors include Royce Mills (three stories),[42][43][44] Brian Miller (two stories),[43][44] and Oliver Gilbert and Peter Messaline (one story).[45] John Leeson, who performed the voice of K9 in several Doctor Who stories, and Davros actors Terry Molloy and David Gooderson also contributed supporting voices for various Dalek serials.[43][46]

Since 2005 the Dalek voice in the television series has been provided by Nicholas Briggs, speaking into a microphone connected to a voice modulator.[37][47] Briggs had previously provided Dalek and other alien voices for Big Finish Productions audio plays, and continues to do so. In a 2006 BBC Radio interview, Briggs said that when the BBC asked him to do the voice for the new television series, they instructed him to bring his own analogue ring modulator that he had used in the audio plays. The BBC's sound department had changed to a digital platform and could not adequately create the distinctive Dalek sound with their modern equipment. Briggs went as far as to bring the voice modulator to the actors' readings of the scripts.[37][47]

Construction

Manufacturing the props was expensive. In scenes where many Daleks had to appear, some of them would be represented by wooden replicas (Destiny of the Daleks)[46] or life-size photographic enlargements in the early black-and-white episodes (The Daleks, The Dalek Invasion of Earth,[15][48] and The Power of the Daleks).[49][50] In stories involving armies of Daleks, the BBC effects team even turned to using commercially available toy Daleks, manufactured by Louis Marx & Co and Herts Plastic Moulders Ltd. Examples of this can be observed in the serials The Power of the Daleks, The Evil of the Daleks, and Planet of the Daleks.[51] Judicious editing techniques also gave the impression that there were more Daleks than were actually available, such as using a split screen in "The Parting of the Ways".[17]

Four fully functioning props were commissioned for the first serial "The Daleks" in 1963, and were constructed from BBC plans by Shawcraft Engineering.[52] These became known in fan circles as "Mk I Daleks". Shawcraft were also commissioned to construct approximately 20 Daleks for the two Dalek movies in 1965 and 1966 (see below). Some of these movie props filtered back to the BBC and were seen in the televised serials, notably The Chase, which was aired before the first movie's debut. The remaining props not bought by the BBC were either donated to charity or given away as prizes in competitions.[53]

The BBC's own Dalek props were reused many times, with components of the original Shawcraft "Mk I Daleks" surviving right through to their final classic series appearance in 1988.[54] But years of storage and repainting took their toll. By the time of the Sixth Doctor's Revelation of the Daleks new props were being manufactured out of fibreglass. These models were lighter and more affordable to construct than their predecessors.[55] These newer models were slightly bulkier in appearance around the mid-shoulder section, and also had a redesigned skirt section which was more vertical at the back. Other minor changes were made to the design due to these new construction methods, including altering the fender and incorporating the arm boxes, collars, and slats into a single fibreglass moulding.[55] These props were repainted in grey for the Seventh Doctor serial Remembrance of the Daleks and designated as "Renegade Daleks"; another redesign, painted in cream and gold, became the "Imperial Dalek" faction.

New Dalek props were built for the 21st-century version of Doctor Who. The first, which appeared alone in the 2005 episode "Dalek", was built by modelmaker Mike Tucker.[36] Additional Dalek props based on Tucker's master were subsequently built out of fibreglass by Cardiff-based Specialist Models.[56]

Development

Wishing to create an alien creature that did not look like a "man in a suit", Terry Nation stated in his script for the first Dalek serial that they should have no legs.[57] He was also inspired by a performance by the Georgian National Ballet, in which dancers in long skirts appeared to glide across the stage.[57] For many of the shows the Daleks were operated by retired ballet dancers wearing black socks while sitting inside the Dalek.[33] Raymond Cusick was given the task of designing the Daleks when Ridley Scott, then a designer for the BBC, proved unavailable after having been initially assigned to their debut serial.[58] According to Jeremy Bentham's Doctor Who—The Early Years (1986), after Nation wrote the script, Cusick was given only an hour to come up with the design for the Daleks and was inspired in his initial sketches by a pepper pot on a table.[59] Cusick himself, however, states that he based it on a man seated in a chair, and used the pepper pot only to demonstrate how it might move.[60]

In 1964, Nation told a Daily Mirror reporter that the Dalek name came from a dictionary or encyclopaedia volume, the spine of which read "Dal – Lek" (or, according to another version, "Dal – Eks").[61] He later admitted that this book and the associated origin of the Dalek name were completely fictitious, and that anyone bothering to check out his story would have found him out.[61] The name had simply rolled off his typewriter.[62] Later, Nation was pleasantly surprised to discover that in Serbo-Croatian the word "dalek" means "far" or "distant".[63]

Nation grew up during the Second World War and remembered the fear caused by German bombings. He consciously based the Daleks on the Nazis, conceiving the species as faceless, authoritarian figures dedicated to conquest, racial purity and complete conformity.[64] The allusion is most obvious in the Dalek stories written by Nation, in particular The Dalek Invasion of Earth (1964) and Genesis of the Daleks (1975).[65][66][67]

Before he wrote the first Dalek serial, Nation was a scriptwriter for the comedian Tony Hancock. The two men had a falling out and Nation either resigned or was fired.[57][61][68] Hancock worked on several series proposals, one of which was called From Plip to Plop, a comedic history of the world that would have ended with a nuclear apocalypse, the survivors being reduced to living in dustbin-like robot casings and eating radiation to stay alive. According to Hancock's biographer Cliff Goodwin, when Hancock saw the Daleks he allegedly shouted at the screen, "That bloody Nation — he's stolen my robots!"[69]

The titling of early Doctor Who stories is complex and sometimes controversial.[70][71] The first Dalek serial is called, variously, The Survivors (the pre-production title), The Mutants (its official title at the time of production and broadcast, later taken by another unrelated story), Beyond the Sun (used on some production documentation), The Dead Planet (the on-screen title of the serial's first episode), or simply The Daleks.[70]

The instant appeal of the Daleks caught the BBC off-guard,[61] and transformed Doctor Who into a national phenomenon. Children were both frightened and fascinated by the alien look of the monsters, and the idea of 'hiding behind the sofa' became a popular, if inaccurate or exaggerated, meme. The Doctor Who production office was inundated with letters and calls asking about the creatures. Newspaper articles focused attention on the series and the Daleks, further enhancing their popularity.[33]

Nation jointly owned the intellectual property rights to the Daleks with the BBC, and the money-making concept proved nearly impossible to sell to anyone else, so he was dependent on the BBC wanting to produce stories featuring the creatures.[72] Several attempts to market the Daleks outside the series were unsuccessful.[73][74] Since Nation's death in 1997, his share of the rights is now administered by his former agent, Tim Hancock.[75]

Early plans for what eventually became the 1996 Doctor Who television movie included radically redesigned Daleks whose cases unfolded like spiders' legs.[76] The concept for these "Spider Daleks" was abandoned, but it was picked up again in several Doctor Who spin-offs.[77]

When the new series was announced, many fans hoped that the Daleks would return once more to the programme.[78][79] The Nation estate, however, demanded levels of creative control over the Daleks' appearances and scripts that were unacceptable to the BBC.[80] Eventually the Daleks were cleared to appear in the first series.[75][81]

Fictional history

Dalek in-universe history has seen many retroactive changes, which have caused continuity problems.[82] When the Daleks first appeared, they were presented as the descendants of the Dals, mutated after a brief nuclear war between the Dal and Thal races 500 years ago. This race of Daleks is destroyed when their power supply is wrecked.[83] However, when they reappear in The Dalek Invasion of Earth, they have conquered Earth in the 22nd century. Later stories saw them develop time travel and a space empire. In 1975, Terry Nation revised the Daleks' origins in Genesis of the Daleks, where the Dals were now called Kaleds (of which "Daleks" is an anagram), and the Dalek design was attributed to one man, the paralyzed Kaled chief scientist and evil genius, Davros.[84] Later Big Finish Productions audio plays attempted to explain this retcon by saying that the Skaro word "dal" simply means warrior,[85] which is how the Kaleds described themselves, while "dal-ek" means "god."[86] According to Genesis of the Daleks, instead of a short nuclear exchange, the Kaled-Thal war was a thousand-year-long war of attrition, fought with nuclear, biological and chemical weapons which caused widespread mutations among the life forms of Skaro. Davros experimented on living Kaled cells to find the ultimate mutated form of the Kaled species, believing his own people had become weak and needed to be replaced by a greater life form. He placed his new Dalek creations in tank-like "travel machines" of advanced technology whose design was based on his own life-support chair.[84]

Genesis of the Daleks marked a new era for the depiction of the species, with most of their previous history either forgotten or barely referred to again.[87] Future stories in the original Doctor Who series, which followed a rough story arc,[88] would also focus more on Davros, much to the dissatisfaction of some fans who felt that the Daleks should take centre stage rather than merely becoming minions of their creator.[89] Davros made his last televised appearance for 20 years in Remembrance of the Daleks, which depicted a civil war between two factions of Daleks. One faction, the "Imperial Daleks", were loyal to Davros, who had become their Emperor, whilst the other, the "Renegade Daleks", followed a black Supreme Dalek. By the end of the story, armies of both factions have been wiped out and the Doctor has tricked them into destroying Skaro. However, Davros escapes and based on the fact that Daleks possess time travel and were spread throughout the universe, there was still a possibility that many had survived these events.[43]

The original "classic" Doctor Who series ended in 1989. In the 1996 Doctor Who TV-movie (which introduced the Eighth Doctor), Skaro has seemingly been recreated and the Daleks are shown to still rule it. Though the aliens are never seen on-screen, the story shows the Time Lord villain the Master being executed on Skaro as Dalek voices chant "Exterminate." In Eighth Doctor audio plays produced by Big Finish from 2000-2005, Paul McGann reprised his role. The audio play The Time of the Daleks featured the Daleks without Davros and nearly removing William Shakespeare from history. In Terror Firma, the Eighth Doctor met a Dalek faction led by Davros who was devolving more into a Dalek-like life form himself while attempting to create new Daleks from mutated humans of Earth. The audio dramas The Apocalypse Element and Dalek Empire also depicted the alien villains invading Gallifrey and then creating their own version of the Time Lord power source known as the Eye of Harmony, allowing the Daleks to rebuild an empire and become a greater threat against the Time Lords and other races that possess time travel.

A new Doctor Who series premiered in 2005, introducing the Ninth Doctor and revealing that the "Last Great Time War" had just ended, resulting in the seeming destruction of the Time Lord society. The episode "Dalek", written by Robert Shearman, was broadcast on BBC One on 30 April 2005 and confirmed that the Time War had mainly involved the Daleks fighting the Time Lords, with the Doctor ending the conflict by seemingly destroying both sides, remarking that his own survival was "not by choice." The episode featured a single Dalek who appeared to be the sole survivor of his race from the Time War.[12] Later audio plays by Big Finish Productions expanded on the Time War in different audio drama series such as Gallifrey: Time War, The Eighth Doctor: Time War, The War Doctor, and The War Master.

A Dalek Emperor returned at the end of the 2005 series, having survived the Time War and then rebuilt the Dalek race with genetic material harvested from human subjects. It saw itself as a god, and the new human-based Daleks were shown worshipping it. The Emperor and this Dalek fleet were destroyed in "The Parting of the Ways".[17] The 2006 season finale "Army of Ghosts"/"Doomsday" featured a squad of four Dalek survivors from the old Empire, known as the Cult of Skaro, composed of Daleks who were tasked with developing imagination to better predict and combat enemies. These Daleks took on names: Jast, Thay, Caan, and their black Dalek leader Sec. The Cult had survived the Time War by escaping into the Void between dimensions. They emerged along with the Genesis Ark, a Time Lord prison vessel containing millions of Daleks, at Canary Wharf due to the actions of the Torchwood Institute and Cybermen from a parallel world. This resulted in a Cyberman-Dalek clash in London, which was resolved when the Tenth Doctor caused both groups to be sucked into the Void. The Cult survived by utilising an "emergency temporal shift" to escape.[14][90]

These four Daleks - Sec, Jast, Thay and Caan - returned in the two-part story "Daleks in Manhattan"/"Evolution of the Daleks", in which whilst stranded in 1930s New York, they set up a base in the partially built Empire State Building and attempt to rebuild the Dalek race. To this end, Dalek Sec merges with a human being to become a Human/Dalek hybrid. The Cult then set about creating "Human Daleks" by "formatting" the brains of a few thousand captured humans so they can have Dalek minds.[18] Dalek Sec, however, becomes more human in personality and alters the plan so the hybrids will be more human like him. The rest of the Cult mutinies. Sec is killed, while Thay and Jast are later wiped out with the hybrids. Dalek Caan, believing it may be the last of its kind now, escapes once more via an emergency temporal shift.[18]

The Daleks returned in the 2008 season's two-part finale, "The Stolen Earth"/"Journey's End", accompanied once again by their creator Davros. The story reveals that Caan's temporal shift sent him into the Time War, despite the War being "Time-Locked." The experience of piercing the Time-Lock resulted in Caan seeing parts several futures, destroying his sanity in the process. Caan rescued many Time War era Daleks and Davros, who created new Dalek troops using his own body's cells. A red Supreme Dalek leads the new army while keeping Caan and Davros imprisoned on the Dalek flagship, the Crucible. Davros and the Daleks plan to destroy reality itself with a "reality bomb." The plan fails due to the interference of Donna Noble, a companion of the Doctor, and Caan, who has been manipulating events to destroy the Daleks after realising the severity of the atrocities they have committed.[20][91]

The Daleks returned in the 2010 episode "Victory of the Daleks", wherein it is revealed that some Daleks survived the destruction of their army in "Journey's End" and retrieved the "Progenitor," a tiny apparatus containing 'original' Dalek DNA.[92] The activation of the Progenitor results in the creation of New Paradigm Daleks who deem the Time War era Daleks to be inferior. The new Daleks are organised into different roles (drone, scientist, strategists, supreme and eternal), which are identifiable with colour-coded armour instead of the identification plates under the eyestalk used by their predecessors. They escape the Doctor at the end of the episode via time travel with the intent to rebuild their Empire.[93]

The Daleks appeared only briefly in subsequent finales "The Pandorica Opens"/"The Big Bang" (2010) and The Wedding of River Song (2011) as Steven Moffat decided to "give them a rest" and stated, "There's a problem with the Daleks. They are the most famous of the Doctor's adversaries and the most frequent, which means they are the most reliably defeatable enemies in the universe."[94] These episodes also reveal that Skaro has been recreated yet again. They next appear in "Asylum of the Daleks" (2012), where the Daleks are shown to have greatly increased numbers and now have a Parliament; in addition to the traditional "modern" Daleks, several designs from both the original and new series appear, all co-existing rather than judging each other as inferior or outdated (except for those Daleks whose personalities deem them "insane" or can no longer battle). All record of the Doctor is removed from their collective consciousness at the end of the episode.

The Daleks then appear in the 50th Anniversary special "The Day of the Doctor", where they are seen being defeated in the Time War. The same special reveals that many Time Lords survived the war since the Doctor found a way to transfer their planet Gallifrey out of phase with reality and into a pocket dimension. In "The Time of the Doctor", the Daleks are one of the races that besieges Trenzalore in an attempt to stop the Doctor from releasing the Time Lords from imprisonment. After converting Tasha Lem into a Dalek puppet, they regain knowledge of the Doctor.

The Twelfth Doctor's first encounter with the Daleks is in his second full episode, "Into the Dalek" (2014), where he encounters a damaged Dalek he names 'Rusty.' Connecting to the Doctor's love of the universe and his hatred of the Daleks, Rusty assumes a mission to destroy other Daleks. In "The Magician's Apprentice"/"The Witch's Familiar" (2015), the Doctor is summoned to Skaro where he learns Davros has rebuilt the Dalek Empire. In "The Pilot" (2017), the Doctor briefly visits a battle during the Dalek-Movellan war.

The Thirteenth Doctor encountered a Dalek in a New Year's Day episode, "Resolution" (2019). A Dalek mutant, separated from its armoured casing, takes control of a human in order to build a new travel device for itself and summon more Daleks to conquer Earth. This Dalek is cloned by a scientist in "Revolution of the Daleks (2021), and attempts to take over Earth using further clones, but are killed by other Daleks for perceived genetic impurity. The Dalek army is later sent by the Doctor into the "void" between worlds to be destroyed, using a spare TARDIS she recently acquired on Gallifrey.

Dalek culture

Daleks have little, if any, individual personality,[14] ostensibly no emotions other than hatred and anger,[12] and a strict command structure in which they are conditioned to obey superiors' orders without question.[95] Dalek speech is characterised by repeated phrases, and by orders given to themselves and to others.[96] Unlike the stereotypical emotionless robots often found in science fiction, Daleks are often angry; author Kim Newman has described the Daleks as behaving "like toddlers in perpetual hissy fits", gloating when in power and flying into a rage when thwarted.[97] They tend to be excitable and will repeat the same word or phrase over and over again in heightened emotional states, most famously "Exterminate! Exterminate!"

Daleks are extremely aggressive, and seem driven by an instinct to attack. This instinct is so strong that Daleks have been depicted fighting the urge to kill[18][44] or even attacking when unarmed.[12][98] The Fifth Doctor characterises this impulse by saying, "However you respond [to Daleks] is seen as an act of provocation."[44] The fundamental feature of Dalek culture and psychology is an unquestioned belief in the superiority of the Dalek race,[95] and their default directive is to destroy all non-Dalek life-forms.[12] Other species are either to be exterminated immediately or enslaved and then exterminated once they are no longer useful.[44]

The Dalek obsession with their own superiority is illustrated by the schism between the Renegade and Imperial Daleks seen in Revelation of the Daleks and Remembrance of the Daleks: the two factions each consider the other to be a perversion despite the relatively minor differences between them.[43] This intolerance of any "contamination" within themselves is also shown in "Dalek",[12] The Evil of the Daleks[95] and in the Big Finish Productions audio play The Mutant Phase.[99] This superiority complex is the basis of the Daleks' ruthlessness and lack of compassion.[12][95] This is shown in extreme in "Victory of the Daleks", where the new, pure Daleks destroy their creators, impure Daleks, with the latters' consent. It is nearly impossible to negotiate or reason with a Dalek, a single-mindedness that makes them dangerous and not to be underestimated.[12] The Eleventh Doctor (Matt Smith) is later puzzled in the "Asylum of the Daleks" as to why the Daleks don't just kill the sequestered ones that have "gone wrong". Although the Asylum is subsequently obliterated, the Prime Minister of the Daleks explains that "it is offensive to us to destroy such divine hatred", and the Doctor is sickened at the revelation that hatred is actually considered beautiful by the Daleks.

Dalek society is depicted as one of extreme scientific and technological advancement; the Third Doctor states that "it was their inventive genius that made them one of the greatest powers in the universe."[98] However, their reliance on logic and machinery is also a strategic weakness which they recognise,[43][46] and thus use more emotion-driven species as agents to compensate for these shortcomings.[43][44][95]

Although the Daleks are not known for their regard for due process, they have taken at least two enemies back to Skaro for a "trial", rather than killing them immediately. The first was their creator, Davros, in Revelation of the Daleks,[42] and the second was the renegade Time Lord known as the Master in the 1996 television movie.[100] The reasons for the Master's trial, and why the Doctor would be allowed to retrieve the Master's remains, have never been explained on screen. The Doctor Who Annual 2006 implies that the trial may have been due to a treaty signed between the Time Lords and the Daleks.[101] The framing device for the I, Davros audio plays is a Dalek trial to determine if Davros should be the Daleks' leader once more.[102]

Spin-off novels contain several tongue-in-cheek mentions of Dalek poetry, and an anecdote about an opera based upon it, which was lost to posterity when the entire cast was exterminated on the opening night. Two stanzas are given in the novel The Also People by Ben Aaronovitch.[103] In an alternative timeline portrayed in the Big Finish Productions audio adventure The Time of the Daleks, the Daleks show a fondness for the works of Shakespeare.[104] A similar idea was satirised by comedian Frankie Boyle in the BBC comedy quiz programme Mock the Week; he gave the fictional Dalek poem "Daffodils; EXTERMINATE DAFFODILS!" as an "unlikely line to hear in Doctor Who".[105]

Because the Doctor has defeated the Daleks so often, he has become their collective arch-enemy and they have standing orders to capture or exterminate him on sight. In later fiction, the Daleks know the Doctor as "Ka Faraq Gatri" ("Bringer of Darkness" or "Destroyer of Worlds"), and "The Oncoming Storm".[17][91] Both the Ninth Doctor (Christopher Eccleston) and Rose Tyler (Billie Piper) suggest that the Doctor is one of the few beings the Daleks fear. In "Doomsday", Rose notes that while the Daleks see the extermination of five million Cybermen as "pest control", "one Doctor" visibly un-nerves them (to the point they physically recoil).[14] To his indignant surprise, in "Asylum of the Daleks", the Eleventh Doctor (Matt Smith) learns that the Daleks have designated him as "The Predator".

Measurements

A rel is a Dalek and Kaled unit of measurement. It was usually a measurement of time, with a duration of slightly more than one second, as mentioned in "Doomsday", "Evolution of the Daleks" and "Journey's End", counting down to the ignition of the reality bomb. (One earth minute most likely equals about 50 rels.) However, in some comic books it was also used as a unit of velocity. Finally, in some cases it was used as a unit of hydroelectric energy (not to be confused with a vep, the unit used to measure artificial sunlight).

The rel was first used in the non-canonical feature film Daleks – Invasion Earth: 2150 A.D., soon after appearing in early Doctor Who comic books.

Licensed appearances

Two Doctor Who movies starring Peter Cushing featured the Daleks as the main villains: Dr. Who and the Daleks, and Daleks - Invasion Earth 2150 AD, based on the television serials The Daleks and The Dalek Invasion of Earth, respectively. The movies were not direct remakes; for example, the Doctor in the Cushing films was a human inventor called "Dr. Who" who built a time-travelling device named Tardis, instead of a mysterious alien who stole a device called "the TARDIS".[106]

Four books focusing on the Daleks were published in the 1960s. The Dalek Book (1964, written by Terry Nation and David Whitaker), The Dalek World (1965, written by Nation and Whitaker) and The Dalek Outer Space Book (1966, by Nation and Brad Ashton) were all hardcover books formatted like annuals, containing text stories and comics about the Daleks, along with fictional information (sometimes based on the television serials, other times made up for the books).[107] Nation also published The Dalek Pocketbook and Space-Travellers Guide, which collected articles and features treating the Daleks as if they were real.[108] Four more annuals were published in the 1970s by World Distributors under the title Terry Nation's Dalek Annual (with cover dates 1976–1979, but published 1975–1978).[109] Two original novels by John Peel, War of the Daleks (1997) and Legacy of the Daleks (1998), were released as part of the Eighth Doctor Adventures series of Doctor Who novels.[110] A novella, The Dalek Factor by Simon Clark, was published in 2004, and two books featuring the Daleks and the Tenth Doctor (I am a Dalek by Gareth Roberts, 2006, and Prisoner of the Daleks by Trevor Baxendale, 2009) have been released as part of the New Series Adventures.[111]

Nation authorised the publication of the comic strip The Daleks in the comic TV Century 21 in 1965. The weekly one-page strip, written by Whitaker but credited to Nation, featured the Daleks as protagonists and "heroes", and continued for two years, from their creation of the mechanised Daleks by the humanoid Dalek scientist, Yarvelling, to their eventual discovery in the ruins of a crashed space-liner of the co-ordinates for Earth, which they proposed to invade. Although much of the material in these strips was directly contradicted by what was later shown on television, some concepts like the Daleks using humanoid duplicates and the design of the Dalek Emperor did show up later on in the programme.[112]

At the same time, a Doctor Who strip was also being published in TV Comic. Initially, the strip did not have the rights to use the Daleks, so the First Doctor battled the "Trods" instead, cone-shaped robotic creatures that ran on static electricity. By the time the Second Doctor appeared in the strip in 1967 the rights issues had been resolved, and the Daleks began making appearances starting in The Trodos Ambush (TVC #788-#791), where they massacred the Trods. The Daleks also made appearances in the Third Doctor-era Dr. Who comic strip that featured in the combined Countdown/TV Action comic during the early 1970s.[113]

An animated series called Daleks!, which consists of five 10-minute long episodes, was released on the official Doctor Who YouTube channel in 2020.[114]

Other licensed appearances have included a number of stage plays (see Stage plays below) and television adverts for Wall's "Sky Ray" ice lollies (1966), Weetabix breakfast cereal (1977), Kit Kat chocolate bars (2001),[115][116] and the ANZ Bank (2005).[117] In 2003, Daleks also appeared in UK billboard ads for Energizer batteries, alongside the slogan "Are You Power Mad?"[115]

Other major appearances

Stage plays

- The Curse of the Daleks: Wyndham's Theatre, London (premiere 21 December 1965)

- Doctor Who and the Daleks in the Seven Keys to Doomsday: Adelphi Theatre, London (premiere 16 December 1974)

- Doctor Who - The Ultimate Adventure: Wimbledon Theatre, London (premiere 23 March 1989)

- The Trial of Davros: The Village Hotel, Hyde, Greater Manchester (premiere 14 November 1993)

- The Trial of Davros: Tameside Hippodrome, Ashton-under-Lyne (premiere 16 July 2005)

- The Evil of the Daleks: Theatre Royal, Portsmouth (premiere 25 October 2006)

- The Daleks' Master Plan: Theatre Royal, Portsmouth (premiere 24 October 2007)

- Recall U.N.I.T. or THE GREAT TEA BAG MYSTERY! Archived 20 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine: Edinburgh Fringe Festival 1984 play by Richard Franklin

Concerts

- Doctor Who Prom (27 July 2008)

- Doctor Who Prom (27 July 2010)

- Doctor Who Prom (27 July 2013)

Original novels and novellas

- War of the Daleks by John Peel (Eighth Doctor Adventures), published October 1997

- Legacy of the Daleks by John Peel (Eighth Doctor Adventures), published April 1998

- The Dalek Factor by Simon Clark (Telos Doctor Who novellas), published March 2004

- I am a Dalek by Gareth Roberts (New Series Adventures, part of the Quick Reads Initiative), published May 2006

- Prisoner of the Daleks by Trevor Baxendale (New Series Adventures), published April 2009

- The Only Good Dalek by Justin Richards and Mike Collins (New Series Adventures), published November 2010

- The Dalek Generation by Nicholas Briggs (New Series Adventures), published April 2013

- Engines of War by George Mann (New Series Adventures), published July 2014

Other appearances

Non–Doctor Who television and film

Daleks have made cameo appearances in television programmes and films unrelated to Doctor Who from the 1960s to the present day.

- Dalek toys are seen in a department store in "Death at Bargain Prices", a 1965 episode of the fantasy/thriller series The Avengers, which, like Doctor Who, was created by Sydney Newman, although broadcast on the rival ITV network.[118]

- Daleks appear in a 1972 episode of BBC TV's Vision On, performing a short ballet sequence to the music of Manuel de Falla's "Ritual Fire Dance".[119]

- During the 1992 Christmas special of the comedy series Mr. Bean, "Merry Christmas Mr. Bean", the title character uses children's toys to play out a bizarre nativity scene in which a Marx Dalek exterminates a tiny lamb and a Tyrannosaurus rex.[120]

- Two to three purple toy Daleks are also seen in the background of an episode of the American children's cartoon Rugrats.[121]

- In the television special The Red Dwarf A–Z, two Daleks are shown (under "E" for "Exterminate") arguing that all Earth television is human propaganda, and the works more commonly attributed to William Shakespeare and Ludwig van Beethoven were actually written by Daleks, although they deny having written "Mandy" by Barry Manilow; subsequently, one of them remarks that the "change the bulb" joke from the episode "Legion" was funny, and is promptly exterminated by the other for the crime of "not behaving like a true Dalek".[122]

- In the 2004 series of Coupling, written by Steven Moffat (who was later to write for and produce Doctor Who), a Dalek appears in the second episode of season four.[123] This was voiced by Nicholas Briggs,[124] who later went on to provide Dalek voices for the series proper from 2005 onwards.[125] (Terry Nation's original Dalek rights deal with the BBC had been negotiated by his then agent Beryl Vertue, later Moffat's mother-in-law.)[126]

- In the film Looney Tunes: Back in Action, the secret military base, Area 52, detains a number of monsters and robots from old sci-fi films; among those are two Daleks, who upon release by Marvin the Martian, proceed to attack while spouting their catchphrases.[115][127]

- A Dalek appeared alongside Darth Vader, Ming the Merciless, a Klingon, the Sixth Doctor and a 1980s Cyberman in a 2003 episode of the British motoring programme Top Gear, to see who was "Master of the Universe" with a lap around their test track in a racing modified Honda Civic.[128] The Dalek could not get into the car, so it exterminated the other drivers (with the exception of the Klingon and the Doctor; who had apparently fled beforehand as they were not present); the Cyberman was eventually declared the winner by the hosts.[129]

- In the final episode of the 2007 series of The Vicar of Dibley, Dawn French's character gets married, supported by two Dalek bridesmaids.

- In a 2009 episode of the American sitcom Better Off Ted, a deactivated Dalek is spotted in the sub-basement where the supposed "Robot Farm" is located.[130]

- In a December 2009 episode ("Party Animals") of the British children's television series Shaun the Sheep, one of the sheep is dressed as a crude version of a Dalek trying to get up some stairs but failing because of the suit.

- In 2010, a Dalek was a "guest" on The Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson sitting off to the side and keeping a watchful eye on Ferguson. It never spoke, but occasionally moved around. This was a lead-up to having Matt Smith as a real guest on the show.

- On 4 May 2011, the popular animated television show, South Park aired its 211th episode, #1502 entitled "Funnybot" featuring a new character, "Funnybot". Funnybot was designed by the Germans to prove that they were a funny people, contrary to what the students of South Park Elementary had to say about them. What the Germans created looked in some ways similar to a Dalek, and in the end lived up to its appearance, albeit with Gatling guns in lieu of a death ray.[131] It even shouts "Exterminate!" at one point.

- In the children's book Animalia by Graeme Base, a Dalek appears on the pages with objects starting with the letter D.[132]

- The 9 December 2012 episode of The Simpsons entitled "The Day the Earth Stood Cool," an outline of a Dalek can be seen on the bottom drawer of T-Rex's dresser when Bart discovers his action figures.

- On 2 September 2013, the Daleks made an appearance in the sketch "Doctor Who's Line is it Anyway?", on the Cartoon Network show Mad.

- In the 2017 film The Lego Batman Movie, the Daleks, in what appears to be a Lego adaptation of their 2010 designs, make an appearance as escaped prisoners from the Phantom Zone.[133] They, who are seen extremely briefly and moving, also seem to be the Lego minifigures produced for Lego Dimensions.

- The Daleks appear in the 2021 drama It's a Sin (written by former Doctor Who show runner Russell T Davies), in scenes where series lead Ritchie Tozer (Olly Alexander) is cast in a fictional Doctor Who story called Regression of the Daleks.[134]

Comic books

- In The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Volume III: Century (2009), a Dalek can be seen during a psychedelic hallucination by Mina Murray.[135]

- In the graphic novel Abslom Daak: Dalek Killer, the titular protagonist, a sentenced criminal with a death wish and an insatiable hatred of the Daleks, hunts his nemeses who have recently invaded the planet Mazar, homeworld of princess Taiyin.[136][137]

Music

Daleks have been referred to or associated in many musical compositions.

- The first known musical reference to Daleks is the 1964 novelty single "I'm Gonna Spend My Christmas with a Dalek" by the Go-Go's, released during the 1960s' "Dalekmania" fad.[138]

- Dalek voices were sampled and recreated in the 1988 novelty single "Doctorin' the Tardis" by The Timelords (who later performed as the KLF),[139]

- Daleks were also sampled by the German electronic band Rotersand in their 2005 single "Exterminate Annihilate Destroy".[140]

- Many other musicians have mentioned Daleks in lyrics, including: the Clash, in "Remote Control" ("Repression—gonna be a Dalek / Repression—I am a robot / Repression—I obey.");[141] the Creatures, in "Weathercade" ("The Dalek drones are drowning");[142] Martin Gordon in "Her Daddy Was a Dalek, Her Mummy Was a Non-Stick Frying Pan" from his album "The Joy of More Hogwash"[143] and the Supernaturals, in "Smile" ("I feel like a Dalek inside/ Everything's gone grey but used to be so black and white").[144] The trock band Chameleon Circuit's eponymous album features a song called Exterminate, Regenerate; which illustrates the conflict between the Doctor and the Daleks. Bands have even incorporated Daleks into their names: Dalek I Love You, a synthpop band active for over ten years from the late 1970s to the beginning of the 1990s, and instrumental surf-rock trio Dalek Beach Party, whose 1992 EP featured the song "Exterminate! Exterminate!"[145]

Dalek is also mentioned and pictured in the Doc Brown vs Doctor Who. Epic Rap Battles of History Season 2, being summoned by Brown to exterminate the Tenth Doctor.

Samples of Dalek voices uttering the phrases "the prisoners have escaped" and "exterminate them" appear in the song "Shakespeare's Tacklebox" by the Australian band Spiderbait on their 1993 debut LP "ShaShaVaGlava".[146]

Video games

Licensed Doctor Who games featuring Daleks include 1984's The Key to Time, a text adventure game for the Sinclair ZX Spectrum.[147] The first graphical game to feature daleks was the eponymous, turn-based title released by Johan Strandberg for the Macintosh in the same year.[148] Daleks also appeared in minor roles or as thinly disguised versions in other, minor games throughout the 80s, but did not feature as central adversaries in a licensed game until 1992, when Admiral Software published Dalek Attack.[149] The game allowed the player to play various Doctors or companions, running them through several environments to defeat the Daleks.[149][150] In 1997 the BBC released a PC game entitled Destiny of the Doctors which also featured the Daleks, among other adversaries.[151]

Unauthorized games featuring Daleks continued to appear through the 1990s and 2000s, including Dalek-based modifications of Dark Forces, Quake, and Half-Life, and even more recently, a mod of Halo: Combat Evolved; many of these can be found online, including an Adobe Flash game, Dalek:Dissolution Earth.[152] In 1998 QWho, a modification for Quake, featured the Daleks as adversaries. This also formed the basis of TimeQuake, a total conversion written in 2000 which included other Doctor Who monsters such as Sontarans.[153] Another unauthorised game is DalekTron, a based on Robotron: 2084 written to coincide with the 2005 series.[154]

One authorised online game is The Last Dalek, a Flash game created by New Media Collective for the BBC. It is based on the 2005 episode "Dalek" and can be played at the official BBC Doctor Who website.[155] The Doctor Who website also features another game, Daleks vs Cybermen (also known as Cyber Troop Control Interface), based on the 2006 episode "Doomsday"; in this game, the player controls troops of Cybermen which must fight Daleks as well as Torchwood Institute members.[156]

On 5 June 2010, the BBC released the first of four official computer games on its website, Doctor Who: The Adventure Games, which are intended as part of the official TV series adventures. In the first of these, 'The City of the Daleks', the Doctor in his 11th incarnation and Amy Pond must stop the Daleks re-writing time and reviving Skaro, their homeland.

They also appear in the Nintendo DS and Wii games Doctor Who: Evacuation Earth and Doctor Who: Return to Earth.

Several Daleks appear in the iOS game The Mazes of Time[157] as rare enemies the player faces, appearing only in the first and final levels.

The robot model 883 in the game Paradroid for the Commodore 64 looks like a Dalek. The game was later ported to other platforms, and several free software clones have been developed since, among them Freedroid Classic. Based on this game is a Diablo style role-playing game called Freedroid RPG where several Dalek-like robots appear. The base version is called Dalex, its powerful, but slow weapon, the Exterminator, is also available to the player.

The Daleks also appear in Lego Dimensions where they ally themselves with Lord Vortech and possess the size-altering scale keystone. When Batman, Gandalf, and Wyldstyle encounter them, they assume that they are allies of the Doctor and attack the trio. The main characters continue to fight the Daleks until they call the Doctor to save them. A Dalek saucer also appears in the level based on Metropolis, in which the top of it serves as the stage for the boss battle against Sauron and includes Daleks among the various enemies summoned to attack the player. A Dalek is also among the elements summoned by the player to deal with the obstacles in the Portal 2 story level.

The Daleks also appear in Doctor Who: The Edge of Time, a Virtual Reality Game for the PlayStation VR, Oculus Rift, Oculus Quest, HTC Vive, and Vive Cosmos, which is set to be released in September 2019.[158]

Politics

At the 1966 Conservative Party conference in Blackpool, delegate Hugh Dykes publicly compared the Labour government's Defence Secretary Denis Healey to the creatures. "Mr. Healey is the Dalek of defence, pointing a metal finger at the armed forces and saying 'I will eliminate you'."[159]

In a British Government Parliamentary Debate in the House of Commons on 12 February 1968, the then Minister of Technology Tony Benn mentioned the Daleks during a reply to a question from the Labour MP Hugh Jenkins concerning the Concorde aircraft project. In the context of the dangers of solar flares, he said, "Because we are exploring the frontiers of technology, some people think Concorde will be avoiding solar flares like Dr. Who avoiding Daleks. It is not like this at all."[160][161]

Australian Labor Party luminary Robert Ray described his right wing Labor Unity faction successor, Victorian Senator Stephen Conroy, and his Socialist Left faction counterpart, Kim Carr, as "factional Daleks" during a 2006 Australian Fabian Society lunch in Sydney.[162]

During a 2021 House of Commons debate about the retention of dentists in rural areas of the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 pandemic, the voice of Conservative MP Scott Mann of North Cornwall, while on a video link, became distorted due to a malfunction with his audio feed. Deputy Speaker of the House Nigel Evans interrupted his broadcast by saying, "Scott, you sound like a Dalek and I don’t mean that unkindly. There’s clearly a communications problem." Mann later returned to apologise.[163][164]

Daleks have been used in political cartoons to caricature: Douglas Hurd, as the 'Douglek', in Private Eye's Dan Dire – Pilot of the Future; Tony Benn,[165] John Birt,[166] Tony Blair[167] (also portrayed as Davros),[168] Alec Douglas-Home,[169] Charles de Gaulle,[170] Mark Thompson.[171]

Magazine covers

Daleks have appeared on magazine covers promoting Doctor Who since the "Dalekmania" fad of the 1960s. Radio Times has featured the Daleks on its cover several times, beginning with the 21–27 November 1964 issue which promoted The Dalek Invasion of Earth.[172] Other magazines also used Daleks to attract readers' attention, including Girl Illustrated.[173]

In April 2005, Radio Times created a special cover to commemorate both the return of the Daleks to the screen in "Dalek" and the forthcoming general election.[174] This cover recreated a scene from The Dalek Invasion of Earth in which the Daleks were seen crossing Westminster Bridge, with the Houses of Parliament in the background. The cover text read "VOTE DALEK!" In a 2008 contest sponsored by the Periodical Publishers Association, this cover was voted the best British magazine cover of all time.[175] In 2013 it was voted "Cover of the century" by the Professional Publishers Association.[176] The 2010 United Kingdom general election campaign also prompted a collector's set of three near-identical covers of the Radio Times on 17 April with exactly the same headline but with the newly redesigned Daleks in their primary colours representing the three main political parties, Red being Labour, Blue as Conservative and Yellow as Liberal Democrats.

Parodies

Daleks have been the subject of many parodies, including Spike Milligan's "Pakistani Dalek" sketch in his comedy series Q,[177][178][179] and Victor Lewis-Smith's "Gay Daleks".[179][180] Occasionally the BBC has used the Daleks to parody other subjects: in 2002, BBC Worldwide published the Dalek Survival Guide, a parody of The Worst-Case Scenario Survival Handbooks.[181] Comedian Eddie Izzard has an extended stand-up routine about Daleks, which was included in his 1993 stand-up show "Live at the Ambassadors".[182] The Daleks made two brief appearances in a pantomime version of Aladdin at the Birmingham Hippodrome which starred Torchwood star John Barrowman in the lead role.[183] A joke-telling robot, possessing a Dalek-like boom, and loosely modelled after the Dalek, also appeared in the South Park episode "Funnybot", even spouting out "exterminate".[184] A Dalek can also be seen in the background at timepoints 1:13 and 1:17 in the Sam & Max animated series episode "The Trouble with Gary". In the Community parody of Doctor Who called Inspector Spacetime, they are referred to as Blorgons.

Merchandising

The BBC approached Walter Tuckwell, a New Zealand-born entrepreneur who was handling product merchandising for other BBC shows, and asked him to do the same for the Daleks and Doctor Who.[185] Tuckwell created a glossy sales brochure that sparked off a Dalek craze, dubbed "Dalekmania" by the press, which peaked in 1965.[186]

Toys and models

The first Dalek toys were released in 1965 as part of the "Dalekmania" craze.[187] These included battery-operated, friction drive and "Rolykins" Daleks from Louis Marx & Co., as well as models from Cherilea, Herts Plastic Moulders Ltd and Cowan, de Groot Ltd, and "Bendy" Daleks made by Newfeld Ltd.[187] At the height of the Daleks' popularity, in addition to toy replicas, there were Dalek board games and activity sets, slide projectors for children and even Dalek playsuits made from PVC.[188] Collectible cards, stickers, toy guns, music singles, punching bags and many other items were also produced in this period.[188] Dalek toys released in the 1970s included a new version of Louis Marx's battery-operated Dalek (1974), a "talking Dalek" from Palitoy (1975) and a Dalek board game (1975) and Dalek action figure (1977), both from Denys Fisher.[189] From 1988 to 2002, Dapol released a line of Dalek toys in conjunction with its Doctor Who action figure series.[190]

In 1984, Sevans Models released a self-assembly model kit for a one-fifth scale Dalek, which Doctor Who historian David Howe has described as "the most accurate model of a Dalek ever to be released".[191] Comet Miniatures released two Dalek self-assembly model kits in the 1990s.[192]

In 1992, Bally released a Doctor Who pinball machine which prominently featured the Daleks both as a primary playfield feature and as a motorised toy in the topper.[193]

Bluebird Toys produced a Dalek-themed Doctor Who playset in 1998.[194]

Beginning in 2000, Product Enterprise (who later operated under the names "Iconic Replicas" and "Sixteen 12 Collectibles") produced various Dalek toys. These included one-inch (2.5 cm) Dalek "Rolykins" (based on the Louis Marx toy from 1965); push-along "talking" 7-inch (17.8 cm) Daleks; 21⁄2-inch (6.4 cm) Dalek "Rollamatics" with a pull back and release mechanism; and a one-foot (30.5 cm) remote control Dalek.[195]

In 2005 Character Options was granted the "Master Toy License" for the revived Doctor Who series, including the Daleks.[196] Their product lines have included 5-inch (12.7 cm) static/push-along and radio controlled Daleks, radio controlled 12-inch (30.5 cm) versions and radio controlled 18-inch (45.7 cm) / 1:3 scale variants.[197] The 12-inch remote control Dalek won the 2005 award for Best Electronic Toy of the Year from the Toy Retailers Association.[196] Some versions of the 18-inch model included semi-autonomous and voice command-features.[198] In 2008, the company acquired a license to produce 5-inch (12.7 cm) Daleks of the various "classic series" variants.[199] For the fifth revived series, both Ironside (Post-Time war Daleks in camouflage khaki), Drone (new, red) and, later, Strategist Daleks (new, blue) were released as both RC Infrared Battle Daleks and action figures.

A pair of Lego based Daleks were included in the Lego Ideas Doctor Who set, and another appeared in the Lego Dimensions Cyberman Fun-Pack.

Full-size reproductions

Dalek fans have been building life-size reproduction Daleks for many years.[200] The BBC and Terry Nation estate officially disapprove of self-built Daleks, but usually intervene only if attempts are made to trade unlicensed Daleks and Dalek components commercially, or if it is considered that actual or intended use may damage the BBC's reputation or the Doctor Who/Dalek brand.[201] The Crewe, Cheshire-based company "This Planet Earth" is the only business which has been licensed by the BBC and the Terry Nation Estate to produce full-size TV Dalek replicas, and by Canal+ Image UK Ltd. to produce full size Movie Dalek replicas commercially.[202][203]

See also

- History of the Daleks

- Dalek variants

- Dalekmania

- Dalek comic strips, illustrated annuals and graphic novels

References

- Martin, Tim; Jones, Ross; Harrod, Horatia; Thompson, Jessie; Lewis, Matt (28 January 2016). "The Daleks were based on the Nazis..." The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 26 February 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- DWTV (15 November 2014). "Moffat: Daleks Are Not A Contractual Obligation". Doctor Who TV. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- Briggs, Asa (1995). The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom. Vol. 5. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-215964-X. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

Designer Raymond Cusick said that he got the idea for their appearance "whilst fiddling with a pepperpot" and had them produced in fibreglass, at a cost of less than £250 each. - Writer Terry Nation, Director Christopher Barry, Producer Verity Lambert (28 December 1963). "The Survivors". Doctor Who. London. BBC.

- "The end of Olde Englande: A lament for Blighty". The Economist. 14 September 2006. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- "Wildlife is alien to a generation of indoor children". National Trust website. 9 July 2008. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- "Mercury and Moore head millennium stamps". BBC News. 24 May 1999. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- "Daleks named greatest monsters by sci-fi fans". The Telegraph. London. 18 August 2010. Archived from the original on 20 August 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- Illingworth, Leslie Gilbert (16 December 1964). "The Degaullek". British Cartoon Archive. University of Kent. Archived from the original on 28 July 2019.

- Simpson, J. A.; Weiner, E. S. C., eds. (1989). Oxford English Dictionary, Volume IV: creel–duzepere (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 221–222. ISBN 0-19-861216-8.

- Gibson, Owen (14 May 2007). "Paxman to raise eyebrows at TV festival lecture" (online). The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 3 October 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- Writer Rob Shearman, Director Joe Ahearne, Executive Producers Russell T Davies, Julie Gardner and Mal Young (30 April 2005). "Dalek". Doctor Who. Cardiff. BBC. BBC One.

- Writer Helen Raynor, Director James Strong, Producer Phil Collinson (21 April 2007). "Daleks in Manhattan". Doctor Who. Cardiff. BBC. BBC1.

- Writer Russell T Davies, Director Graeme Harper, Executive Producers Russell T Davies and Julie Gardner (8 August 2006). "Doomsday". Doctor Who. Cardiff. BBC. BBC One.

- Writer Terry Nation, Director Richard Martin, Producer Verity Lambert (5 December 1964). "Day of Reckoning". Doctor Who. London. BBC. BBC1.

- Harris (1983), p. 22

- Writer Russell T Davies, Director Joe Ahearne, Executive Producers Russell T Davies, Julie Gardner and Mal Young (18 June 2005). "The Parting of the Ways". Doctor Who. Cardiff. BBC. BBC One.

- Writer Helen Raynor, Director James Strong, Producer Phil Collinson (28 April 2007). "Evolution of the Daleks". Doctor Who. Cardiff. BBC. BBC1.

- Cook, Benjamin; Cribbins, Bernard (25 July 2008). "Bernard Cribbins: Stargazer: Wilfred Mott". Doctor Who Magazine. No. 398. Royal Tunbridge Wells, Kent: Panini Comics. p. 33.

- Writer Russell T Davies, Director Graeme Harper, Producer Phil Collinson (28 June 2008). "The Stolen Earth". Doctor Who. Cardiff. BBC. BBC One.

- Writer Terry Nation, Director Christopher Barry, Producer Verity Lambert (4 January 1964). "The Escape". Doctor Who. London. BBC.

- Writer Ben Aaronovitch, Director Andrew Morgan, Producer John Nathan-Turner (19 October 1988). "Remembrance of the Daleks, Part Three". Doctor Who. London. BBC. BBC1.

- Writer Eric Saward, Director Matthew Robinson, Producer John Nathan-Turner (8 February 1984). "Resurrection of the Daleks, Part One". Doctor Who. London. BBC. BBC1.

- Dicks, Terrance (20 December 1974). "Letters to the Editor – Inside a Dalek". The Times. UK. p. 13.

- Chris Chibnall (writer), Wayne Yip (director), Nikki Wilson (producer) (1 January 2019). "Resolution". Doctor Who. Series 11. Episode - 2019 New Year's Day Special. BBC. BBC One.

- "Ray Cusick, designer of the Daleks, died on February 21st, aged 84". The Economist. 2 March 2013. Archived from the original on 18 January 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- Writer Terry Nation, Director Ken Grieve, Producer Graham Williams (8 September 1979). "Destiny of the Daleks, Episode Two". Doctor Who. London. BBC. BBC1.

- Dippold, Ron (6 February 1992). "Federal Department of Transportation Bulletin #92–132" (USENET post). alt.fan.warlord. Archived from the original on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 9 March 2010 – via Google Groups.

- Writer Terry Nation, Director Richard Martin, Producer Verity Lambert (21 November 1964). "World's End". Doctor Who. London. BBC. BBC1.

- Writer Ben Aaronovitch, Director Andrew Morgan, Producer John Nathan-Turner (5 October 1988). "Remembrance of the Daleks, Part One". Doctor Who. London. BBC. BBC1.

- "Aliens with a Human Face: The Human-like Non-Humans of Doctor Who | Mithila Review". Mithila Review. 11 April 2017. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Howe (1992), pp. 3, 26–27

- Howe (2004), p. 31

- Howe (1997), p. 82

- Howe (1997), p. 85

- Arnopp, Jason (July 2005). "Tucker's Luck". Doctor Who Magazine Special Edition. No. 11. Royal Tunbridge Wells, Kent: Panini Comics. pp. 62–70.

- Briggs, Nicholas (25 May 2005). "Diary of a Dalek". Doctor Who Magazine. No. 356. Royal Tunbridge Wells, Kent: Panini Comics. pp. 23–27.

- Howe (1997), pp. 84–85

- Russell (2006), p. 163

- "BBC – Doctor Who – Dalek Empire III [interview with Nicholas Briggs]". BBC News. 8 July 2004. Archived from the original on 10 January 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- Planet of the Daleks. Writer Terry Nation, Director David Maloney, Producer Barry Letts. Doctor Who. BBC1, London. 7 April–12 May 1973.

- Revelation of the Daleks. Writer Eric Saward, Director Graeme Harper, Producer John Nathan-Turner. Doctor Who. BBC1, London. 23–30 March 1985.

- Remembrance of the Daleks. Writer Ben Aaronovitch, Director Andrew Morgan, Producer John Nathan-Turner. Doctor Who. BBC1, London. 5–26 October 1988.

- Resurrection of the Daleks. Writer Eric Saward, Director Matthew Robinson, Producer John Nathan-Turner. Doctor Who. BBC1, London. 8–15 February 1984.

- Day of the Daleks. Writer Louis Marks, Director Paul Bernard, Producer Barry Letts. Doctor Who. BBC1, London. 1–22 January 1972.

- Destiny of the Daleks. Writer Terry Nation, Director Ken Grieve, Producer Graham Williams. Doctor Who. BBC1, London. 1–22 September 1979.

- Seaborne, Gilliane (director) (30 April 2005). "Dalek". Doctor Who Confidential. BBC Three.

- Writer Terry Nation, Director Richard Martin, Producer Verity Lambert (28 November 1964). "The Daleks". Doctor Who. London. BBC. BBC1.

- Writer David Whitaker, Director Christopher Barry, Producer Innes Lloyd (26 November 1966). "The Power of the Daleks, Episode Four". Doctor Who. London. BBC. BBC1.

- "BBC – Doctor Who – Photonovels Power of the Daleks – Episode Four". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 January 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- Writer Terry Nation, Director David Maloney, Producer Barry Letts (12 March 1973). "Planet of the Daleks, Episode Six". Doctor Who. London. BBC. BBC1.

- Burk, Graeme (2013). Who's 50: the 50 Doctor Who stories to watch before you die : an unofficial companion. Toronto: ECW Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-77041-166-1. OCLC 861785703.

- Howe (1992), pp. 132, 137

- "Dalek 6388 Remembrance". Dalek 6388 – A Dalek Prop History – Remembrance of the Daleks. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- Howe (1997), p. 92

- "BBC Wales Dr Who Daleks Fibreglass Props". Specialist Models & Displays. 21 March 2010. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- Howe (1997), p. 80

- Howe (1994), p. 61

- Bentham, Jeremy (May 1986). Doctor Who—The Early Years. England: W.H. Allen. ISBN 0-491-03612-4.

- Walker (2006), p. 61

- Peel (1988), pp. 21–22

- Howe (1998), p. 13

- Davies, Kevin (director) (1993). More than 30 Years in the TARDIS London, UK: BBC Video.

- Howe (1992), p. 31

- Miles (2006), pp. 105–109

- Howe (1998), p. 280

- Howe, David J.; Stephen James Walker (2003) [1998]. "Doctor Who Classic Episode Guide – Genesis of the Daleks – Details". official Doctor Who website. BBC. Archived from the original on 11 August 2010. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- Miles (2006), p. 40

- Goodwin, Cliff (November 2000). When the Wind Changed: The Life and Death of Tony Hancock. England: Arrow. ISBN 0-09-960941-X.

- Pixley, Andrew (15 January 2001). "By Any Other Name". Earthbound Timelords. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- Howe (1998), unpaginated "Authors' Note"

Richards, Justin (2003). Doctor Who—The Legend: 40 Years of Time Travel. London: BBC Books. p. 19. ISBN 0-563-48602-3. - On-screen production notes, The Dalek Invasion of Earth London, UK: BBC Video, 2003.

- Peel (1988), p. 56

- Howe (1997), p. 86

- "Daleks back to fight Doctor Who". BBC News. 4 August 2004. Archived from the original on 27 April 2010. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- Segal (2000), pp. 48–53

- Barnes, Alan (w), Geraghty, Martin (p), Smith, Robin (i). "Fire and Brimstone" Doctor Who: Endgame: 52–89, 214 (2005), Royal Tunbridge Wells, Kent: Panini Comics, ISBN 1-905239-09-2

Peel, John (1997). Doctor Who: War of the Daleks. London: BBC Books. ISBN 0-563-40573-2. - Michael Anthony Basil (6 October 2003). "Science Fiction Weekly – Letters to the Editor". Archived from the original on 14 October 2003. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- "Put scary Daleks back in Dr Who!". thisishampshire.net. Archived from the original on 28 April 2010. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- "No Daleks in Doctor Who's return". BBC News. 2 July 2004. Archived from the original on 27 February 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- Bishop, Tom (24 April 2005). "Dalek terror returns to Doctor Who". BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 April 2010. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- Peel (1988), p. 78

- The Daleks. Writer Terry Nation, Director Christopher Barry, Producer Verity Lambert. Doctor Who. BBC, London. 21 December 1963 – 1 February 1964.

- Genesis of the Daleks. Writer Terry Nation, Director David Maloney, Producer Philip Hinchcliffe. Doctor Who. BBC1, London. 8 March–12 April 1975.

- Big Finish audio play The New Adventures of Bernice Summerfield: The Lights of Skaro

- Big Finish audio play I, Davros: Guilt

- Cornell, Paul; Day, Martin; Topping, Keith (1995). "The second history of the Daleks". Official Doctor Who website. BBC. Archived from the original on 1 October 2010. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- Parkin (2006), p. 237

- Howe, David J; Walker, Stephen James (1998). Doctor Who: The Television Companion (1st ed.). London: BBC Books. p. 455. ISBN 1-903889-51-0.

- Writer Russell T Davies, Director Graeme Harper, Producer Phil Collinson (1 July 2006). "Army of Ghosts". Doctor Who. Cardiff. BBC. BBC One.

- Writer Russell T Davies, Director Graeme Harper, Producer Phil Collinson (5 July 2008). "Journey's End". Doctor Who. Cardiff. BBC. BBC One.

- McKinstry, Peter. "BBC concept artwork for Dalek Progenator". BBC. Archived from the original on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- "The Eleventh Doctor is coming!". Doctor Who Magazine. No. 418. Royal Tunbridge Wells, Kent: Panini Comics. 3 March 2010. p. 5. ISSN 0957-9818.

- "Doctor Who writer Steven Moffat to 'rest' Daleks". BBC News. 30 May 2011. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- The Evil of the Daleks. Writer David Whitaker, Director Derek Martinus, Producer Innes Lloyd. Doctor Who. BBC1, London. 20 May–1 July 1967.

- Peel (1988), p. 4

- Newman, p. 33

- Death to the Daleks. Writer Terry Nation, Director Michael E. Briant, Producer Barry Letts. Doctor Who. BBC1, London. 23 February–16 March 1974.

- The Mutant Phase. Writer and Director Nicholas Briggs. Producers Gary Russell and Jason Haigh-Ellery. Big Finish Productions, 2000.