Devika Rani

Devika Rani Choudhuri (30 March 1908 – 9 March 1994), usually known as Devika Rani, was an Indian actress who was active in Hindi films during the 1930s and 1940s. Widely acknowledged as the first lady of Indian cinema, Devika Rani had a successful film career that spanned 10 years.

Devika Rani | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Rani in Nirmala (1938) | |

| Born | Devika Rani Chaudhuri 30 March 1908 |

| Died | 9 March 1994 (aged 85) |

| Other names | Devika Rani Roerich |

| Occupation | Textile designer, actress, singer |

| Years active | 1928–1943 |

| Spouses | |

| Awards | Dadasaheb Phalke Award (1969) |

| Honours | Padma Shri (1958) |

| Signature | |

| |

Born into a wealthy, anglicized Indian family, Devika Rani was sent to boarding school in England at age nine and grew up in that country. In 1928, she met Himanshu Rai, an Indian film-producer, and married him the following year. She assisted in costume design and art direction for Rai's experimental silent film A Throw of Dice (1929).[lower-alpha 1] Both of them then went to Germany and received training in film-making at UFA Studios in Berlin. Rai then cast himself as hero and her as heroine in his next production, the bilingual film Karma (1933), made simultaneously in English & Hindi. The film premiered in England in 1933, elicited interest there for a prolonged kissing scene featuring the real-life couple, and flopped badly in India. The couple returned to India in 1934, where Himanshu Rai established a production studio, Bombay Talkies, in partnership with certain other people. The studio produced several successful films over the next 5–6 years, and Devika Rani played the lead role in many of them. Her on-screen pairing with Ashok Kumar became popular in India.

Following Rai's death in 1940, Devika Rani took control of the studio and produced some more films in partnership with her late husband's associates, namely Sashadhar Mukherjee and Ashok Kumar. As she was to recollect in her old age, the films which she supervised tended to flop, while the films supervised by the partners tended to be hits. In 1945, she retired from films, married the Russian painter Svetoslav Roerich and moved to his estate on the outskirts of Bangalore, thereafter leading a very reclusive life for the next five decades. Her persona, no less than her film roles, were considered socially unconventional. Her awards include the Padma Shri (1958), Dadasaheb Phalke Award (1970) and the Soviet Land Nehru Award (1990).

Background and education

Devika Rani was born as Devika Rani Choudhury on 30 March 1908 in Waltair near Visakhapatnam in present-day Andhra Pradesh, into an extremely affluent and educated Bengali family, the daughter of Col. Dr. Manmathnath Choudhury by his wife Leela Devi Choudhury.

Devika's father, Colonel Manmatha Nath Chaudhuri, scion of a large landowning zamindari family, was the first Indian Surgeon-General of Madras Presidency. Devika's paternal grandfather, Durgadas Choudhury, was the Zamindar (landlord) of Chatmohar Upazila of Pabna district of present-day Bangladesh. Her paternal grandmother, Sukumari Devi (wife of Durgadas), was a sister of the nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore.[2][3][4] Devika's father had five brothers, all of them distinguished in their own fields, mainly law, medicine and literature. They were Sir Ashutosh Chaudhuri, Chief Justice of Calcutta High Court during the British Raj; Jogesh Chandra Chaudhuri and Kumudnath Chaudhuri, both prominent Kolkata-based barristers; Pramathanath Choudhary, the famous Bengali writer, and Dr. Suhridnath Chaudhuri, a noted medical practitioner.[5] The future Chief of Army Staff, Jayanto Nath Chaudhuri, was Devika's first cousin: their fathers were brothers to each other.

Devika's mother, Leela Devi Choudhury, also came from an equally educated family and was a niece of Rabindranath Tagore. Thus, Devika Rani was related through both her parents to the poet and Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore. Her father, Manmathnath Choudhury, was the son of Sukumari Devi Choudhury, sister of Rabindranath Tagore. Devika's mother, Leela Devi Chaudhuri, was the daughter of Indumati Devi Chattopadhyay, whose mother Saudamini Devi Gangopadhyay was another sister of the Nobel laureate. Thus, Devika's father and maternal grandmother were first cousins to each other, being the children of two sisters of Rabindranath Tagore.[6] Nor was this all: Two of Devika's uncles (Chief Justice Sir Ashutosh and Pramathanath) were married to their first cousins (mother's brother's daughters), the nieces of Rabindranath Tagore: Prativa Devi Choudhury, wife of Sir Ashutosh Choudhury, was the daughter of Hemendranath Tagore, and Indira Devi Choudhury, wife of Pramathanath Choudhury, was the daughter of Satyendranath Tagore.[7] Devika thus had extremely strong family ties to Jarasanko, seat of the Tagore family in Kolkata and a major crucible of the Bengali Renaissance.

Devika Rani was sent to boarding school in England at the age of nine, and grew up there. After completing her schooling in the mid-1920s,[8] she enrolled in the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) and the Royal Academy of Music in London to study acting and music.[3][9] She also enrolled for courses in architecture, textile and decor design, and even apprenticed under Elizabeth Arden. All of these courses, each of them a few months long, were completed by 1927, and Devika Rani then took up a job in textile design.[10]

Career

In 1928, Devika Rani first met her future husband, Himanshu Rai, an Indian barrister-turned-film maker, who was in London preparing to shoot his forthcoming film A Throw of Dice.[lower-alpha 1][9][11] Rai was impressed with Devika's "exceptional skills" and invited her to join the production team of the film, although not as an actress.[12] She readily agreed, assisting him in areas such as costume designing and art direction.[13] The two also traveled to Germany for the post-production work, where she had occasion to observe the film-making techniques of the German film industry, specifically of G. W. Pabst and Fritz Lang.[12] Inspired by their methods of film-making, she enrolled for a short film-making course at Universum Film AG studio in Berlin.[12] Devika Rani learnt various aspects of film-making and also took a special course in film acting.[9] Around this time, they both acted in a play together, for which they received many accolades in Switzerland and the Scandinavian countries. During this time she was also trained in the production unit of Max Reinhardt, an Austrian theatre director.[14]

In 1929, shortly after the release of A Throw of Dice, Devika Rani and Himanshu Rai were married.[12]

Acting debut

.jpg.webp)

Devika and Himanshu Rai returned to India, where Himanshu produced a film titled Karma (1933). The film was his first talkie, and like his previous films, it was a joint production between people from India, Germany and the United Kingdom. Rai, who played the lead role, decided to cast Devika Rani as the female lead, and this marked her acting debut. Karma is credited as having been the first English language talkie made by an Indian. It was one of the earliest Indian films to feature a kissing scene.[15] The kissing scene, involving Himanshu Rai and Devika Rani, lasted for about four minutes,[16] and eighty years later, this stands as the record for duration of a kissing scene in Indian cinema as of 2014.[17][18] Devika Rani also sang a song in the film, a bi-lingual song in English and Hindi. This song is said to be Bollywood's first English song.[19][20]

.jpg.webp)

Made simultaneously in both English and Hindi, Karma premiered in London in May 1933. Alongside a special screening for the Royal family at Windsor, the film was well received throughout Europe.[21] Devika Rani's performance was internationally acclaimed as she won "rave reviews" in the London media.[12] A critic from The Daily Telegraph noted Devika Rani for her "beauty" and "charm" while also crediting her to be a "potential star of the first magnitude".[21] Following the release of the film, she was invited by the BBC to enact a role in their first ever television broadcast in Britain in 1933. She also inaugurated the company's first short wave radio transmission to India.[22] In spite of its success in England, Karma did not interest Indian audiences and turned out be a failure in India when it was released in Hindi as Nagin Ki Ragini in early 1934. However, the film received good critical response and helped Devika Rani establish herself as a leading actress in Indian cinema. Indian independence activist and poet Sarojini Naidu called her a "lovely and gifted little lady".[21]

Bombay Talkies

After the critical success of Karma, the couple returned to India in 1934. Although the Hindi version of the film, released in India in 1934, flopped without a trace, Himanshu Rai had established the required networks in Europe, and was able to start a film studio named Bombay Talkies, partnering with Niranjan Pal, a Bengali playwright and screenwriter who he had met previously in London[4] and Franz Osten, who directed several of Rai's films.[23]

Upon inception, Bombay Talkies was one of the "best-equipped" film studios in the country. The studio would serve as a launch pad for future actors including Dilip Kumar, Leela Chitnis, Madhubala, Raj Kapoor, Ashok Kumar and Mumtaz.[24] The studio's first film Jawani Ki Hawa (1935), a crime thriller, [25] starring Devika Rani and Najm-ul-Hassan, was shot fully on a train.[12]

Elopement

Najm-ul-Hassan was also Devika's co-star in the studio's next venture, Jeevan Naiya. The two co-stars developed a romantic relationship, and during the shooting schedule of Jeevan Naiya, Devika eloped with Hassan. Himanshu was both enraged and distraught. Since the leading pair were absent, production was stalled. A significant portion of the movie had been shot and a large sum of money, which had been taken as credit from financers, had been spent. The studio therefore suffered severe financial losses and a loss of credit among bankers in the city while the runaway couple made merry.

Sashadhar Mukherjee, an assistant sound-engineer at the studio, had a brotherly bond with Devika Rani because both of them were Bengalis and spoke that language with each other. He established contact with the runaway couple and managed to convince Devika Rani to return to her husband. In the India of that era, divorce was legally almost impossible and women who eloped were regarded as no better than prostitutes and were shunned by their own families. In her heart of hearts, Devika Rani knew that she could not secure a divorce or marry Hassan under any circumstances. She negotiated with her husband through the auspices of Sashadhar Mukherjee, seeking the separation of her finances from those of her husband as a condition for her return. Henceforth, she would be paid separately for working in his films, but he would be required to single-handedly pay the household expenses for the home in which both of them would live. Himanshu agreed to this, in order to save face in society and to prevent his studio from going bankrupt. Devika Rani returned to her marital home. However, things would never be the same between husband and wife again, and it is said that thenceforth, their relationship was largely confined to work and little or no intimacy transpired between them after this episode.

Despite the additional expense involved in re-shooting many portions of the film, Himanshu Rai replaced Najm-ul-Hassan with Ashok Kumar, who was the brother of Sashadhar Mukherjee's wife, as the hero of Jeevan Naiya. This marked the debut, improbable as it may seem, of Ashok Kumar's six-decade-long career in Hindi films. Najm-ul-Hassan was dismissed from his job at Bombay Talkies (this was the period in which actors and actresses were paid regular monthly salaries by one specific film studio and could not work in any other studio). His reputation as a dangerous cad established, he could not find work in any other studio. His career was ruined and he sank into obscurity.[26]

Golden era of Bombay Talkies

.jpg.webp)

Achhut Kannya (1936), the studio's next production was a tragedy drama that had Devika Rani and Ashok Kumar portraying the roles of an untouchable girl and a Brahmin boy who fall in love.[27] The film is considered a "landmark" in Indian cinema as it challenged the caste system in the country. The casting of Devika Rani was considered a mismatch as her looks did not match the role of a poor untouchable girl by virtue of her "upper-class upbringing".[28] However, her pairing with Ashok Kumar became popular and they went on to star in as many as ten films together with most of them being Bombay Talkies productions.[12][27]

In the 1930s, Bombay Talkies produced several women-centric films with Devika Rani playing the lead role in all of them. In majority of the films produced by the studio, she was paired opposite Ashok Kumar, who was "overshadowed" by her.[29] Jeevan Prabhat, released in 1937, saw a role-reversal between Devika Rani and Ashok Kumar—she played a higher-caste Brahmin woman who is mistaken by society of having an extra-marital affair with an untouchable man. Her next release Izzat (1937), based on Romeo and Juliet, was set in the medieval period and depicted two lovers belonging to enemy clans of a Maratha empire.[27] Nirmala, released in the following year, dealt with the plight of a child-less woman who is told by an astrologer to abandon her husband to ensure successful pregnancy.[27] In Vachan, her second release of the year, she played a Rajput princess.[30] Durga, her only release in 1939, was a romantic drama that told the story of an orphaned girl and a village doctor, played by Ashok Kumar.[12][31]

Widowhood and studio decline

Following the death of Rai in 1940, there was a rift between two parties of the Bombay Talkies led by Mukherjee and Amiya Chakravarty.[32] Devika Rani assumed principal responsibility and took over the studio along with Mukherjee. In 1941, she produced and acted in Anjaan co-starring Ashok Kumar. In the subsequent years, she produced two successful films under the studio—Basant and Kismet. Basant Kismet (1943) contained anti-British messages (India was under British rule at that time) and turned out to be a "record-breaking" film.[33] Devika Rani made her last film appearance in Hamari Baat (1943), which had Raj Kapoor playing a small role.

She handpicked newcomer Dilip Kumar for a role in Jwar Bhata (1944), produced by her on behalf of the studio. An internal politics that arose in the studio led prominent personalities including Mukherjee and Ashok Kumar to part ways with her and set up a new studio called Filmistan.[33] Due to lack of support and interest, she decided to quit the film industry. In an interview to journalist Raju Bharatan, she mentioned that her idea of not willing to compromise on "artistic values" of film-making as one of the major reasons for her quitting the industry.[34]

Retirement

Following her retirement from films, Devika Rani married Russian painter Svetoslav Roerich, son of Russian artist Nicholas Roerich, in 1945. After marriage, the couple moved to Manali, Himachal Pradesh where they got acquainted with the Nehru family. During her stay in Manali, Devika Rani made a few documentaries on wildlife. After staying in Manali for some years, they moved to Bangalore, Karnataka, and settled there managing an export company.[35] The couple bought a 450 acres (1,800,000 m2) estate on the outskirts of the city and led a solitary life for the remainder of their lives.[12]

Death

She died of bronchitis on 9 March 1994—a year after Roerich died—in Bangalore.[37][38] At her funeral, Devika Rani was given full state honors.[39] Following her death, the estate was on litigation for many years as the couple had no legal claimants; Devika Rani remained childless throughout her life. In August 2011, the Government of Karnataka acquired the estate after the Supreme Court of India passed the verdict in favour of them.[40]

Legacy

Devika Rani was called the first lady of Indian cinema.[24][41][42] She is credited for being one of the earliest personalities who took the position of Indian cinema to global standards.[43] Her films were mostly tragic romantic dramas that contained social themes.[29] The roles played by her in films of Bombay Talkies usually involved in romantic relationship with men who were unusual for the social norms prevailing in the society at that time, mainly for their caste background or community identity.[27] Rani was highly influenced by the German cinema by virtue of her training at the UFA Studios;[41]

Although she was influenced by German actress Marlene Dietrich,[24] her acting style was compared to Greta Garbo,[39] thus leading to Devika Rani being named the "Indian Garbo".[44][45]

Rani's attire, both in films and sometimes in real life, were considered "risque" at that time.[46] In his book Bless You Bollywood!: A tribute to Hindi Cinema on completing 100 years, Tilak Rishi mentions that Devika Rani was known as the "Dragon Lady" for her "smoking, drinking, cursing and hot temper".[47]

In 1958, the Government of India honoured Devika Rani with a Padma Shri, the country's fourth highest civilian honour. She became the first ever recipient of the Dadasaheb Phalke Award, the country's highest award for films, when it was instituted in 1969.[39][48]

In 1990, Soviet Russia honoured her with the "Soviet Land Nehru Award".[49]

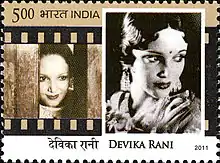

A postage stamp commemorating her life was released by the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology in February 2011.[50]

In 2020, Kishwar Desai published a book titled The Longest Kiss: The Life and Times of Devika Rani, which sheds light on Devika Rani's professional accomplishments and her personal misfortunes.[51][52]

Filmography

- Karma (1933)

- Jawani Ki Hawa (1935)

- Mamta Aur Mian Biwi (1936)

- Jeevan Naiya (1936)

- Janmabhoomi (1936)

- Achhoot Kannya (1936)

- Savitri (1937)

- Jeevan Prabhat (1937)

- Izzat (1937)

- Prem Kahani (1937)

- Nirmala (1938)

- Vachan (1938)

- Durga (1939)

- Anjaan (1941)

- Hamari Baat (1943)

Notes

- A Throw of Dice was alternately known as Prapancha Pash in India.[1]

References

Citations

- Papamichael, Stella (24 August 2007). "A Throw Of Dice (Prapancha Pash) (2007)". BBC. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- "B-town women who dared!". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- Erik 1980, p. 93.

- "Devika Rani" (PDF). Press Information Bureau. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- Paul, Samar (17 March 2012). "Pramatha Chaudhury's home: Our responsibility". The Financial Express. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- "Tagore family". Archived from the original on 13 May 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- Tagore family Archived 24 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Rogowski 2010, p. 168.

- "Devika Rani Roerich". Roerich & DevikaRani Roerich Estate Board, Government of Karnataka. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- Ghosh 1995, pp. 28–29.

- Ghosh 1995, p. 29.

- Varma, Madhulika (26 March 1994). "Obituary: Devika Rani". The Independent. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- Gulzar, Nihalani & Chatterjee 2003, p. 545.

- Patel 2012, p. 19.

- "Karma 1933". The Hindu. 10 January 2009. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- Jaikumar 2006, p. 229.

- Barrass, Natalie (14 April 2014). "In bed with Bollywood: sex and censorship in Indian cinema". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- Dasgupta, Priyanka (30 April 2012). "India's longest kissing scene clips in Paoli film". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 25 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- Ranchan 2014, p. 42.

- Chakravarty, Riya (3 May 2013). "Indian cinema@100: 40 Firsts in Indian cinema". NDTV. Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- "Pathbreaker by Karma". The Hindu. 10 January 2009. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- "Top heroines of Bollywood". India Today. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- Manjapra 2014, p. 239.

- Kohli, Suresh (15 April 2014). "Indian cinema's prima donna". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- Hardy 1997, p. 180.

- Manṭo 2003, pp. 244–245.

- Manjapra 2014, p. 270.

- Majumdar 2009, p. 88.

- Manjapra 2014, p. 271.

- Patel 2012, p. 23.

- Baghdadi & Rao 1995, p. 353.

- Patel 2012, p. 27.

- Patel 2012, p. 24.

- Patel 2012, pp. 24–25.

- Patel 2012, p. 25.

- "The Rediff Special/M D Riti". 4 October 2002. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- "Devika Rani Roerich". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. 11 March 1994. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- Kaur 2013, p. 12.

- Rohith B. R. (19 February 2014). "Roerichs' Tataguni estate to get a new life". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- Rogowski 2010, p. 169.

- Rishi 2012, p. 98.

- Manjapra 2014, pp. 258.

- Imprint 1973, p. 31.

- "The Indian Garbo". Hindustan Times. 30 May 2003. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- Manjapra 2014, pp. 270–271.

- Rishi 2012, p. 112.

- "Dadasaheb Phalke Awards". Directorate of Film Festivals. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- "Eye catchers". India Today. 15 February 1990. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014.

- "Stamps 2011". Department of Posts, Ministry of Communications & Information Technology (India). Archived from the original on 18 May 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- "'The Longest Kiss' sheds light on Devika Rani's life kept away from world". Malayala Manorama. 22 December 2020. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- "Review: The Longest Kiss; The Life and Times of Devika Rani by Kishwar Desai". Hindustan Times. 20 August 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

Bibliography

- Baghdadi, Rafique; Rao, Rajiv (1995). Talking films. Indus. ISBN 978-81-7223-197-2.

- Erik, Barnouw (1980). Indian film. Oxford University Press, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-19-502682-5.

- Ghosh, Nabendu (1995). Ashok Kumar: His Life and Times. Indus. ISBN 978-81-7223-218-4.

- Gulzar; Nihalani, Govind; Chatterjee, Saibal (2003). "Biographies". Encyclopaedia of Hindi Cinema. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 81-7991-066-0.

- Hardy, Phil (1997). The BFI Companion to Crime. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21538-2.

- Jaikumar, Priya (2006). Cinema at the End of Empire: A Politics of Transition in Britain and India. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3793-2.

- Kaur, Simren (2013). Fin Feather and Field. Partridge Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4828-0066-1.

- Majumdar, Neepa (2009). Wanted Cultured Ladies Only!: Female Stardom and Cinema in India, 1930s-1950s. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-09178-0.

- Manjapra, Kris (2014). Age of Entanglement. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72631-4.

- Manṭo, Saʻādat Ḥasan (2003). Black Margins: Stories. Katha. ISBN 978-81-87649-40-3.

- Patel, Bhaichand (2012). Bollywood's Top 20: Superstars of Indian Cinema. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-670-08572-9.

- Ranchan, Vijay (2014). Story of a Bollywood Song. Abhinav Publications. GGKEY:9E306RZQTQ7.

- Rishi, Tilak (2012). Bless You Bollywood!: A tribute to Hindi Cinema on completing 100 years. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4669-3962-2.

- Rogowski, Christian (2010). The Many Faces of Weimar Cinema: Rediscovering Germany's Filmic Legacy. Camden House. ISBN 978-1-57113-429-5.

- "1973 imprint". Imprint. Business Press. 13 (2). 1973.