Dhaka

Dhaka (/ˈdɑːkə/ DAH-kə or /ˈdækə/ DAK-ə; Bengali: ঢাকা, romanized: Ḍhākā, Bengali pronunciation: [ˈɖʱaka]), formerly known as Dacca,[12] is the capital and largest city of Bangladesh, as well as the world's largest Bengali-speaking city. It is the eighth largest and sixth most densely populated city in the world with a population of 8.9 million residents as of 2011, and a population of over 21.7 million residents in the Greater Dhaka Area.[13][14] According to a Demographia survey, Dhaka has the most densely populated built-up urban area in the world, and is popularly described as such in the news media.[15][16]Dhaka is one of the major cities of South Asia and a major global Muslim-majority city.As of 2021, Dhaka's nominal GDP is estimated to be US$253.30 billion and GDP (PPP) is estimated to be US$510.276 billion.[17] Dhaka ranks 39th in the world and 3rd in South Asia in terms of urban GDP. As part of the Bengal delta, the city is bounded by the Buriganga River, Turag River, Dhaleshwari River and Shitalakshya River.

Dhaka

ঢাকা Dacca | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp)    .jpg.webp) From top: Shapla Square in Motijheel, Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban in Sher-e-Bangla Nagar , Ahsan Manzil in Old Dhaka, Lalbagh Fort, Curzon Hall of the University of Dhaka, lakefront of Hatirjheel | |

| Nickname: | |

Dhaka Location in Dhaka  Dhaka Location in Dhaka Division  Dhaka Location in Bangladesh  Dhaka Location in Asia .svg.png.webp) Dhaka Location in Earth | |

| Coordinates: 23°45′50″N 90°23′20″E | |

| Country | Bangladesh |

| Division | Dhaka Division |

| District | Dhaka District |

| Establishment | 1608 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor - Council |

| • Body | DNCC and DSCC |

| • North Mayor | Atiqul Islam[3] |

| • South Mayor | Sheikh Fazle Noor Taposh[3] |

| • Police Commissioner | Shafiqul Islam, BPM (Bar) |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 305.47 km2 (117.94 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,161.17[6] km2 (834.432[6] sq mi) |

| Elevation | 32 m (104.96 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Rank | 1st |

| • Density | 29,373/km2 (76,080/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 8,906,039 |

| • Metro | 21,741,090 |

| Demonym | Dhakaiya |

| Time zone | UTC+6 (BST) |

| Postal code | 1000, 1100, 12xx, 13xx |

| HDI (2019) | 0.711[10] high |

| Calling code | 02 [For Dhaka city only] |

| Metro GDP | $405.872 Billion PPP[11] |

| Police | Dhaka Metropolitan Police |

| International airport | Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport |

| ISO 3166-2 | BD-13 |

| Website | Dhaka North City Corporation Dhaka South City Corporation |

The area of Dhaka has been inhabited since the first millennium. An early modern city developed from the 17th century as a provincial capital and commercial centre of the Mughal Empire. Dhaka was the capital of a proto-industrialised Mughal Bengal for 75 years (1608–39 and 1660–1704). It was the hub of the muslin trade in Bengal and one of the most prosperous cities in the world. The Mughal city was named Jahangirnagar (City of Jahangir) in honour of the erstwhile ruling emperor Jahangir.[18][19][20] The city's wealthy Mughal elite included princes and the sons of Mughal emperors. The pre-colonial city's glory peaked in the 17th and 18th centuries when it was home to merchants from across Eurasia. The Port of Dhaka was a major trading post for both riverine and seaborne trade. The Mughals decorated the city with well-laid gardens, tombs, mosques, palaces and forts. The city was once called the Venice of the East.[21] Under British rule, the city saw the introduction of electricity, railways, cinemas, Western-style universities and colleges and a modern water supply. It became an important administrative and educational centre in the British Raj, as the capital of Eastern Bengal and Assam province after 1905.[22] In 1947, after the end of British rule, the city became the administrative capital of East Pakistan. It was declared the legislative capital of Pakistan in 1962. In 1971, after the Liberation War, it became the capital of independent Bangladesh.

A beta-global city,[23] Dhaka is the center of political, economic and culture life in Bangladesh. It is the seat of the Government of Bangladesh, many Bangladeshi companies and leading Bangladeshi educational, scientific, research and cultural organizations. Since its establishment as a modern capital city; the population, area and social and economic diversity of Dhaka have grown tremendously. The city is now one of the most densely industrialized regions in the country. The city accounts for 35% of Bangladesh's economy.[24] The Dhaka Stock Exchange has over 750 listed companies. Dhaka hosts over 50 diplomatic missions as well as the headquarters of BIMSTEC, CIRDAP and the International Jute Study Group. Dhaka has a renowned culinary heritage. The city's culture is known for its rickshaws, biryani, art festivals and religious diversity. The old city is home to around 2000 buildings from the Mughal and British periods. Since 1947, the city saw significant growth in its publishing industry, including the emergence of a thriving press.[25] In Bengali literature, Dhaka's heritage has been reflected in the works of Akhteruzzaman Elias, Tahmima Anam, Shazia Omar and other Bangladeshi writers.[26]

Etymology

The origins of the name Dhaka are uncertain. Once dhak trees were very common in the area and the name may have originated from it. Alternatively, this name may refer to the hidden Hindu goddess Dhakeshwari, whose temple is located in the south-western part of the city.[27] Another popular theory states that Dhaka refers to a membranophone instrument, dhak which was played by order of Subahdar Islam Khan I during the inauguration of the Bengal capital in 1610.[28]

Some references also say it was derived from a Prakrit dialect called Dhaka Bhasa; or Dhakka, used in the Rajtarangini for a watch-station; or it is the same as Davaka, mentioned in the Allahabad pillar inscription of Samudragupta as an eastern frontier kingdom.[29] According to Rajatarangini written by a Kashmiri Brahman, Kalhana,[30] the region was originally known as Dhakka. The word Dhakka means watchtower. Bikrampur and Sonargaon—the earlier strongholds of Bengal rulers were situated nearby. So Dhaka was most likely used as the watchtower for the fortification purpose.[30]

History

Pre-Mughal

The history of urban settlements in the area of modern-day Dhaka dates to the first millennium.[27] The region was part of the ancient district of Bikrampur, which was ruled by the Sena dynasty.[31] Under Islamic rule, it became part of the historic district of Sonargaon, the regional administrative hub of the Delhi and the Bengal Sultanates.[32] The Grand Trunk Road passed through the region, connecting it with North India, Central Asia and the southeastern port city of Chittagong. Before Dhaka, the capital of Bengal was Gour. Even earlier capitals included Pandua, Bikrampur and Sonargaon. The latter was also the seat of Isa Khan and his son Musa Khan, who both headed a confederation of twelve chieftains that resisted Mughal expansion in eastern Bengal during the late 16th century. Due to a change in the course of the Ganges, the strategic importance of Gour was lost. Dhaka was viewed with strategic importance due to the Mughal need to consolidate control in eastern Bengal. The Mughals also planned to extend their empire beyond into Assam and Arakan. Dhaka and Chittagong became the eastern frontiers of the Mughal Empire.

Early period of Mughal Bengal

_Dhaka_Bangladesh_2011_54.JPG.webp)

Dhaka became the capital of the Mughal province of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa in 1610 with a jurisdiction covering modern-day Bangladesh and eastern India, including the modern-day Indian states of West Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. This province was known as Bengal Subah. Dhaka became one of the richest and greatest cities in the world during the early period of Bengal Subah (1610-1717). The prosperity of Dhaka reached its peak during the administration of governor Shaista Khan (1644-1677 and 1680-1688). Rice was then sold at eight maunds per rupee. Thomas Bowrey, an English merchant sailor who visited the city between 1669 and 1670, wrote that the city was 40 miles in circuit. He estimated the city to be more populated than London with 900,000 people.[33]

Bengal became the economic engine of the Mughal Empire. Dhaka played a key role in the proto-industrialisation of Bengal. It was the center of the muslin trade in Bengal, leading to muslin being called "daka" in distant markets as far away as Central Asia.[34] Mughal India depended on Bengali products like rice, silk and cotton textiles. European East India Companies from Britain, Holland, France and Denmark also depended on Bengali products. Bengal accounted for 40% of Dutch imports from Asia, with many products being sold to Dutch ships in Bengali harbors and then transported to Batavia in the Dutch East Indies. Bengal accounted for 50% of textiles and 80% of silks in Dutch textile imports from Asia.[35] Silk was also exported to premodern Japan.[36] The region had a large shipbuilding industry which supplied the Mughal Navy. The shipbuilding output of Bengal during the 16th and 17th centuries stood at 223,250 tons annually, compared to 23,061 tons produced by North America from 1769 to 1771.[37] The Mughals decorated the city with well-laid out gardens. Caravanserai included the Bara Katra and Choto Katra. The architect of the palatial Bara Katra was Abul Qashim Al Hussaini Attabatayi Assemani.[38] According to inscriptions in the Bangladesh National Museum, the ownership of Bara Katra was entrusted to an Islamic waqf.[38] The Bara Katra also served as a residence for Mughal governors, including Prince Shah Shuja (the son of Taj Mahal builder and Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan).[38] Dhaka was home to an array of Mughal bureaucrats and military officials, as well as members of the imperial family. The city was guarded by Mughal artillery like the Bibi Mariam Cannon (Lady Mary Cannon).

Islam Khan I was the first Mughal governor to reside in the city.[39] Khan named it "Jahangir Nagar" (City of Jahangir) in honour of the Emperor Jahangir. The name was dropped soon after the English conquered. The main expansion of the city took place under governor Shaista Khan. The city then measured 19 by 13 kilometres (11.8 by 8.1 mi), with a population of nearly one million.[40] Dhaka became home to one of the richest elites in Mughal India.[41] The construction of Lalbagh Fort was commenced in 1678 by Prince Azam Shah, who was the governor of Bengal, a son of Emperor Aurangzeb and a future Mughal Emperor himself. The Lalbagh Fort was intended to be the viceregal residence of Mughal governors in eastern India. Before the fort's construction could be completed, the prince was recalled by Emperor Aurangzeb. The fort's construction was halted by Shaista Khan after the death of his daughter Pari Bibi, who is buried in a tomb in the center of the unfinished fort. Pari Bibi, whose name means Fairy Lady, was legendary for her beauty, engaged to Prince Azam Shah, and a potential future Mughal empress before her premature death.[42] Internal conflict in the Mughal court cut short Dhaka's growth as an imperial city. Prince Azam Shah's rivalry with Murshid Quli Khan resulted in Dhaka losing its status as the provincial capital. In 1717, the provincial capital was shifted to Murshidabad where Murshid Quli Khan declared himself as the Nawab of Bengal.

Naib Nizamat

Under the Nawabs of Bengal, the Naib Nazim of Dhaka was in charge of the city. As the principal tax collector, the annual revenue of the Naib Nazim was 1 million rupees, which was a staggeringly high amount in that era.[43] The Naib Nazim was the deputy governor of Bengal. He also dealt with the upkeep of the Mughal Navy. The Naib Nazim was in charge of Dhaka Division, which included Dhaka, Comilla, and Chittagong. Dhaka Division was one of the four divisions under the Nawabs of Bengal. The Nawabs of Bengal allowed European trading companies to establish factories across Bengal. The region then became a hotbed for European rivalries. The British moved to oust the last independent Nawab of Bengal in 1757, who was allied with the French. Due to the defection of the Nawab's army chief Mir Jafar to the British side, the last Nawab lost the Battle of Plassey.

After the Battle of Buxar in 1765, the Treaty of Allahabad allowed the British East India Company to become the tax collector in Bengal on behalf of the Mughal Emperor in Delhi. The Naib Nazim continued to function until 1793, when all his powers were transferred to the East India Company. The city formally passed to the control of the East India Company in 1793. British military raids damaged a lot of the city's infrastructure.[44] The military conflict caused a sharp decline in the urban population.[45] Dhaka's fortunes received a boost with connections to the mercantile networks of the British Empire.[46] With the dawn of the Industrial Revolution in Britain, Dhaka became a leading center of the jute trade, as Bengal accounted for the largest share of the world's jute production.[47] But the British neglected Dhaka's industrial and urban development until the late 19th century. Income from the pre-colonial, proto-industrialized textile industry dried up. Bengali weavers went out of business due to Britain's subsidized garments industry, including the imposition of a 75 percent customs tax on Indian fabric imports in England, as well as the surge in imports of cheap, British-manufactured fabrics into India after the advent of the spinning mule and steam power.[48] English fabric imports were subjected to only token taxes.[49] Many of the city's weavers starved to death during Bengal's great famines under British rule.[50] The rapid growth of the colonial capital Calcutta contributed to the decline in Dhaka's population and economy in the early 1800s. In 1824, an Anglican bishop described Dhaka as a "city of magnificent ruins".[51]

Trade and migration

Dhaka hosted factories of the English East India Company, the Dutch East India Company,[52] and French East India Company.[53] The property of the Ahsan Manzil was initially bought by the French for their factory and later sold to the Dhaka Nawab Family. The Portuguese were reportedly responsible for introducing cheese.[54][55] Dhaka saw an influx of migrants during the Mughal Empire. An Armenian community from the Safavid Empire settled in Dhaka and was involved in the city's textile trade, paying a 3.5% tax.[56] The Armenians were very active in the city's social life. They opened the Pogose School. Marwaris were the Hindu trading community. Dhaka also became home to Jews and Greeks.[57][58] The city has a Greek memorial. Several families of Dhaka's elite spoke Urdu and included Urdu poets. Persians also settled in the city to serve as administrators and military commanders of the Mughal government in Bengal.[59] The legacy of cosmopolitan trading communities lives on in the names of neighborhoods in Old Dhaka, including Farashganj (French Bazaar), Armanitola (Armenian Quarter) and Postogola (Portuguese Quarter).

According to those who lived in the historic city, "Dhaka was a courtly, genteel town – the very last flowering, in their telling, of Mughal etiquette and sensibility. It is this history that is today still reflected in the faded grandeur of the old city, now crumbling due to decades of neglect. The narrow, winding, high-walled lanes and alleyways, the old high-ceilinged houses with verandas and balconies, the old neighbourhoods, the graveyards and gardens, the mosques, the grand old mansions – these are all still there if one goes looking".[60] Railway stations, postal departments, civil service posts and river port stations were often manned by Anglo-Indians.[61]

The city's hinterland supplied rice, jute, gunny sacks, turmeric, ginger, leather hides, silk, rugs, saltpeter,[62] salt,[63] sugar, indigo, cotton, and iron.[64] British opium policy in Bengal contributed to the Opium Wars with China. American traders collected artwork, handicrafts, terracotta, sculptures, religious and literary texts, manuscripts and military weapons from Bengal. Some objects from the region are on display in the Peabody Essex Museum.[65] The increase in international trade led to profits for many families in the city, allowing them to buy imported luxury goods.

British Raj

During the Indian mutiny of 1857, the city witnessed revolts by the Bengal Army.[66] Direct rule by the British crown was established following the successful quelling of the mutiny. It bestowed privileges on the Dhaka Nawab Family, which dominated the city's political and social elite. The Dhaka Cantonment was established as a base for the British Indian Army. The British developed the modern city around Ramna, Shahbag Garden and Victoria Park. Dhaka got its own version of the hansom cab as public transport in 1856.[67] The number of carriages increased from 60 in 1867 to 600 in 1889.[67]

A modern civic water system was introduced in 1874.[68] In 1885, the Dhaka State Railway was opened with a 144 km metre gauge (1000 mm) rail line connecting Mymensingh and the Port of Narayanganj through Dhaka.[69] The city later became a hub of the Eastern Bengal State Railway.[69] The first film shown in Dhaka was screened on the riverfront Crown Theatre on 17 April 1898.[70] The film show was organized by the Bedford Bioscope Company.[70] The electricity supply began in 1901.[71]

This period is described as being "the colonial-era part of Dhaka, developed by the British during the early 20th century. Similar to colonial boroughs the length and breadth of the Subcontinent, this development was typified by stately government buildings, spacious tree-lined avenues, and sturdy white-washed bungalows set amidst always overgrown (the British never did manage to fully tame the landscape) gardens. Once upon a time, this was the new city; and even though it is today far from the ritziest part of town, the streets here are still wider and the trees more abundant and the greenery more evident than in any other part".[60]

Some of the early educational institutions established during the period of British rule include the Dhaka College, the Dhaka Medical School, the Eden College, St. Gregory's School, the Mohsinia Madrasa, Jagannath College and the Ahsanullah School of Engineering. Horse racing was a favourite pastime for elite residents in the city's Ramna Race Course beside the Dhaka Club.[72] The Viceroy of India would often dine and entertain with Bengali aristocrats in the city. Automobiles began appearing after the turn of the century. An 1937 Sunbeam-Talbot Ten was preserved in the Liberation War Museum. The Nawabs of Dhaka owned Rolls Royces. Austin cars were widely used. Beauty Boarding was a popular inn and restaurant.

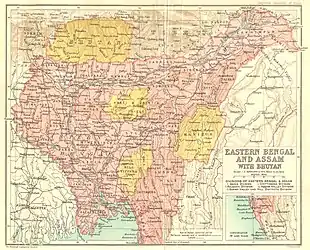

Dhaka's fortunes changed in the early 20th century. British neglect of Dhaka's urban development was overturned with the first partition of Bengal in 1905, which restored Dhaka's status as a regional capital. The city became the seat of government for Eastern Bengal and Assam, with a jurisdiction covering most of modern-day Bangladesh and all of what is now Northeast India. The partition was the brainchild of Lord Curzon, who finally acted on British ideas for partitioning Bengal with a view to improve administration, education and business. Dhaka became the seat of the Eastern Bengal and Assam Legislative Council. While Dhaka was the main capital throughout the year, Shillong acted as the summer retreat of the administration. Lieutenant Governors were in charge of the province. They resided in Dhaka. The Lt Governors included Sir Bampfylde Fuller (1905-1906), Sir Lancelot Hare (1906-1911) and Sir Charles Stuart Bayley (1911-1912). Their legacy lives on in the names of three major thoroughfares in modern Dhaka, including Hare Road,[73] Bayley Road, and Fuller Road.[74] The period saw the construction of stately buildings, including the High Court and Curzon Hall.

Dhaka was the seat of government for 4 administrative divisions, including the Assam Valley Division, Chittagong Division, Dacca Division, Rajshahi Division and the Surma Valley Division. There were a total of 30 districts in Eastern Bengal and Assam, including Dacca, Mymensingh, Faridpur and Backergunge in Dacca Division; Tippera, Noakhali, Chittagong and the Hill Tracts in Chittagong Division; Rajshahi, Dinajpur, Jalpaiguri, Rangpur, Bogra, Pabna and Malda in Rajshahi Division; Sylhet, Cachar, the Khasi and Jaintia Hills, the Naga Hills and the Lushai Hills in Surma Valley Division; and Goalpara, Kamrup, the Garo Hills, Darrang, Nowgong, Sibsagar and Lakhimpur in Assam Valley Division.[75] The province was bordered by Cooch Behar State, Hill Tipperah and the Kingdom of Bhutan.

On the political front, partition allowed Dhaka to project itself as the standard-bearer of Muslim communities in British India; as opposed to the heavily Hindu-dominated city of Calcutta.[47] In 1906, the All India Muslim League was founded in the city during a conference on liberal education hosted by the Nawab of Dhaka and the Aga Khan III. The Muslim population in Dhaka and eastern Bengal generally favored partition in the hopes of getting better jobs and educational opportunities. Many Bengalis, however, opposed the bifurcation of the ethnolinguistic region. The partition was annulled by an announcement of King George V during the Delhi Durbar in 1911. The British decided to reunite Bengal while the capital of India was shifted to New Delhi from Calcutta.

As a "splendid compensation" for the annulment of partition,[76] the British gave the city a newly formed university in the 1920s. The University of Dhaka was initially modelled on the residential style of the University of Oxford. It became known as the Oxford of the East because of its residential character. Like Oxford, students in Dhaka were affiliated with their halls of residence instead of their academic departments (this system was dropped after 1947 and students are now affiliated with academic departments).[77][78] The university's faculty included scientist Satyendra Nath Bose (who is the namesake of the Higgs boson); linguist Muhammad Shahidullah, Sir A F Rahman (the first Bengali vice-chancellor of the university); and historian R. C. Majumdar.[78] The university was established in 1921 by the Imperial Legislative Council. It started with three faculties and 12 departments, covering the subjects of Sanskrit, Bengali, English, liberal arts, history, Arabic, Islamic Studies, Persian, Urdu, philosophy, economics, politics, physics, chemistry, mathematics, and law.

The East Bengal Cinematograph Company produced the first full-length silent movies in Dhaka during the 1920s, including Sukumari and The Last Kiss.[70] DEVCO, a subsidiary of the Occtavian Steel Company, began widescale power distribution in 1930.[71] The Tejgaon Airport was constructed during World War II as a base for Allied Forces. The Dhaka Medical College was established in 1946.

Metropolitan Dhaka

The development of the "real city" began after the partition of India.[60] After partition, Dhaka became known as the second capital of Pakistan.[60][79] This was formalized in 1962 when Ayub Khan declared the city as the legislative capital under the 1962 constitution. New neighborhoods began to spring up in formerly baren and agrarian areas. These included Dhanmondi (rice granary), Katabon (thorn forest), Kathalbagan (jackfruit grove), Kalabagan (banana grove), and Gulshan (flower garden).[60] Living standards rapidly improved from the pre-partition standards.[80] The economy began to industrialize. On the outskirts of the city, the world's largest jute mill was built. The mill produced jute goods which were in high demand during the Korean War.[81] People began building duplex houses. In 1961, Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip witnessed the improved living standards of Dhaka's residents.[82] The Intercontinental hotel, designed by William B. Tabler, was opened in 1966. Estonian-American architect Louis I. Kahn was enlisted to design the Dhaka Assembly, which was originally intended to be the federal parliament of Pakistan and later became independent Bangladesh's parliament. The East Pakistan Helicopter Service connected the city to regional towns.

The Dhaka Stock Exchange was opened on 28 April 1954. The first local airline Orient Airways began flights between Dhaka and Karachi on 6 June 1954. The Dhaka Improvement Trust was established in 1956 to coordinate the city's development. The first master plan for the city was drawn up in 1959.[83] The Southeast Asia Treaty Organization established a medical research centre (now called ICDDR,B) in the city in 1960.

The early period of political turbulence was seen between 1947 and 1952, particularly the Bengali Language Movement. From the mid-1960s, the Awami League's 6 point autonomy demands began giving rise to pro-independence aspirations across East Pakistan. In 1969, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was released from prison amid a mass upsurge which led to the resignation of Ayub Khan in 1970. The city had an influential press with prominent newspapers like the Pakistan Observer, Ittefaq, Forum, and the Weekly Holiday. During the political and constitutional crisis in 1971, the military junta led by Yahya Khan refused to transfer power to the newly elected National Assembly, causing mass riots, civil disobedience and a movement for self-determination. On 7 March 1971, Awami League leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman addressed a massive public gathering at the Ramna Race Course Maidan in Dhaka, in which he warned of an independence struggle.[84][85] Subsequently, East Pakistan came under a non-co-operation movement against the Pakistani state. On Pakistan's Republic Day (23 March 1971), Bangladeshi flags were hoisted throughout Dhaka in a show of resistance.[86]

On 25 March 1971, the Pakistan Army launched military operations under Operation Searchlight against the population of East Pakistan.[87] Dhaka bore the brunt of the army's atrocities, witnessing a genocide and a campaign of wide scale repression, with the arrest, torture and murder of the city's civilians, students, intelligentsia, political activists and religious minorities. The army faced mutinies from the East Pakistan Rifles and the Bengali police.[88] Large parts of the city were burnt and destroyed, including Hindu neighborhoods.[87] Much of the city's population was either displaced or forced to flee to the countryside.[89] In the ensuing Bangladesh War of Independence, the Bangladesh Forces launched regular guerrilla attacks and ambush operations against Pakistani forces. Dhaka was struck with numerous air raids by the Indian Air Force in December.[90] Dhaka witnessed the surrender of the west Pakistan forces in front of the Bangladesh-India Allied Forces on 16 December 1971 with the surrender of Pakistan.[91]

After independence, Dhaka's population grew from several hundred thousand to several million in a span of five decades. Dhaka was declared the national capital by the Constituent Assembly of Bangladesh in 1972. The post-independence period witnessed rapid growth as Dhaka attracted migrant workers from across rural Bangladesh. 60% of population growth has been due to rural migration.[92] The city endured socialist unrest in the early 1970s, followed by a few years of martial law. The stock exchange and free market were restored in the late 1970s. In the 1980s, Dhaka saw the inauguration of the National Parliament House (which won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture), a new international airport and the Bangladesh National Museum. Bangladesh pioneered the formation of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and hosted its first summit in Dhaka in 1985.[93] A mass uprising in 1990 led to the return of parliamentary democracy. Dhaka has hosted a trilateral summit between India, Pakistan and Bangladesh in 1998;[94] the summit of the D-8 Organization for Economic Cooperation in 1999 and conferences of the Commonwealth, SAARC, the OIC and United Nations agencies during various years.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Dhaka experienced improved economic growth and the emergence of affluent business districts and satellite towns.[95] Between 1990 and 2005, the city's population doubled from 6 million to 12 million.[96] There has been increased foreign investment in the city, particularly in the financial and textile manufacturing sectors. But frequent hartals by political parties have greatly hampered the city's economy.[97] The hartal rate has declined since 2014. In some years, the city experienced a widespread flash flood during the monsoon.

Dhaka is one of the fastest growing megacities in the world.[98] It is predicted to be one of the world's largest metropolises by 2025, along with Tokyo, Mexico City, Shanghai, Beijing and New York City.[99] Dhaka remains one of the poorest megacities. Most of its population are rural migrants, including climate refugees.[100] Blue-collar workers are often housed in slums. Congestion is one of the most prominent features of modern Dhaka. In 2014, it was reported that only 7% of the city was covered by roads.[101] The first phase of the Dhaka Metro is planned for opening in December 2022, coinciding with Bangladesh's 51st victory day.[102]

Geography

Topography

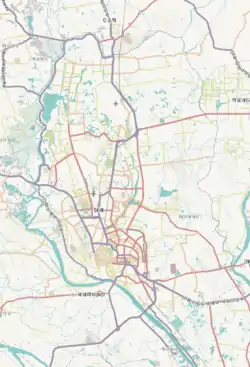

Dhaka is located in central Bangladesh at 23°42′N 90°22′E, on the eastern banks of the Buriganga River. The city lies on the lower reaches of the Ganges Delta and covers a total area of 306.38 square kilometres (118.29 sq mi). Tropical vegetation and moist soils characterize the land, which is flat and close to sea level. This leaves Dhaka susceptible to flooding during the monsoon seasons owing to heavy rainfall and cyclones.[103] Due to its location on the lowland plain of the Ganges Delta, the city is fringed by extensive mangroves and tidal flat ecosystems.[104] Dhaka District is bounded by the districts of Gazipur, Tangail, Munshiganj, Rajbari, Narayanganj, Manikganj.

Cityscape

With the exception of Old Dhaka, which is an old bazaar-style neighborhood, the layout of the city follows a grid pattern with organic development influenced by traditional South Asian as well as Middle Eastern and Western patterns. Growth of the city is largely unplanned and is focused on the northern regions and around the city centre, where many of the more affluent neighborhoods may be found.[105] Most of the construction in the city consists of concrete high-rise buildings. Middle-class and upper-class housing, along with commercial and industrial areas, occupy most of the city; slums may be found in the outskirts and in less-visible areas such as alleyways. The most significant area of slums is found near the Buriganga River covering Kamrangirchar Thana.[106][105]

Dhaka does not have a well-defined central business district. Old Dhaka is the historic commercial center, but most development has moved to the north. The area around Motijheel is considered the "old" CBD, while to some extent Gulshan is considered the "new" CBD.[107] Many Bangladeshi government institutions can be found in Tejgaon, Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, and Ramna.

Dhaka is among the most congested cities in the world, and traffic was estimated to cost the local economy US$3.9 billion per year in 2013. The average speed of a car travelling in Dhaka is estimated to be around 20 kilometres per hour (12 mph).[108] Most residents travel by rickshaw and green-coloured auto rickshaws powered by compressed natural gas, often referred to by locals as "CNGs". Much activity is centered around a few large roads, where road laws are rarely obeyed and street vendors and beggars are frequently encountered.[105][109][110]

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Dhaka has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen Aw). The city has a distinct monsoonal season, with an annual average temperature of 26 °C (79 °F) and monthly means varying between 19 °C (66 °F) in January and 29 °C (84 °F) in May.[111] Approximately 87% of the average annual rainfall of 2,123 millimetres (83.6 inches) occurs between May and October.[111] According to the air quality index (AQI), the air of Dhaka is "unhealthy", and it posited third in the measurement of pollution.[112] Increasing air and water pollution emanating from traffic congestion and industrial waste are serious problems affecting public health and the quality of life in the city.[113] Water bodies and wetlands around Dhaka are facing destruction as these are being filled up to construct multi-storied buildings and other real estate developments. Coupled with pollution, such erosion of natural habitats threatens to destroy much of the regional biodiversity.[113] Due to the unregulated manufacturing of brick and other causes, Dhaka is one of the most polluted world cities with very high levels of PM2.5 air pollution.[114]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 31.1 (88.0) |

34.4 (93.9) |

40.6 (105.1) |

42.2 (108.0) |

41.1 (106.0) |

36.7 (98.1) |

35.0 (95.0) |

36.1 (97.0) |

36.7 (98.1) |

37.4 (99.3) |

34.4 (93.9) |

30.6 (87.1) |

42.2 (108.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 25.1 (77.2) |

28.3 (82.9) |

32.5 (90.5) |

33.8 (92.8) |

33.4 (92.1) |

32.5 (90.5) |

31.8 (89.2) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.8 (89.2) |

29.7 (85.5) |

26.5 (79.7) |

30.8 (87.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 18.6 (65.5) |

22.0 (71.6) |

26.3 (79.3) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.8 (83.8) |

29.0 (84.2) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.9 (84.0) |

28.5 (83.3) |

27.4 (81.3) |

24.0 (75.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

25.9 (78.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 13.1 (55.6) |

16.2 (61.2) |

20.8 (69.4) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.8 (76.6) |

26.2 (79.2) |

26.3 (79.3) |

26.4 (79.5) |

25.9 (78.6) |

23.9 (75.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

14.8 (58.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 6.1 (43.0) |

6.7 (44.1) |

10.6 (51.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

14.4 (57.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

21.1 (70.0) |

21.7 (71.1) |

21.1 (70.0) |

17.2 (63.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

6.1 (43.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 7.5 (0.30) |

23.7 (0.93) |

61.7 (2.43) |

140.6 (5.54) |

278.4 (10.96) |

346.5 (13.64) |

375.5 (14.78) |

292.9 (11.53) |

340.0 (13.39) |

174.5 (6.87) |

31.1 (1.22) |

12.1 (0.48) |

2,084.5 (82.07) |

| Average rainy days | 2 | 3 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 14 | 17 | 16 | 13 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 105 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71 | 64 | 62 | 71 | 76 | 82 | 83 | 82 | 83 | 78 | 73 | 73 | 75 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 220.3 | 225.3 | 256.3 | 237.8 | 220.9 | 142.2 | 131.5 | 140.6 | 152.7 | 228.6 | 236.3 | 242.6 | 2,435.1 |

| Source 1: Bangladesh Meteorological Department[115][116][117] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Sistema de Clasificación Bioclimática Mundial (extremes 1934–1994),[118] Deutscher Wetterdienst (sun, 1961–1990)[119][120][121] | |||||||||||||

Parks and greenery

There are many parks within Dhaka City, including Ramna Park, Suhrawardy Udyan, Shishu Park, National Botanical Garden, Baldha Garden, Chandrima Uddan, Gulshan Park and Dhaka Zoo. There are lakes within city, such as Crescent Lake, Dhanmondi Lake, Baridhara-Gulshan Lake, Banani lake, Uttara Lake, Hatirjheel-Begunbari Lake and 300 Feet Road Prionty lake.[122]

Government

Capital city

As the capital of the People's Republic of Bangladesh, Dhaka is the home to numerous state and diplomatic institutions. The Bangabhaban is the official residence and workplace of the President of Bangladesh, who is the ceremonial head of state under the constitution. The National Parliament House is located in the modernist capital complex designed by Louis Kahn in Sher-e-Bangla Nagar. The Gonobhaban, the official residence of the Prime Minister, is situated on the north side of Parliament. The Prime Minister's Office is located in Tejgaon. Most ministries of the Government of Bangladesh are housed in the Bangladesh Secretariat.[123] The Supreme Court, the Dhaka High Court and the Foreign Ministry are located in the Ramna area. The Defence Ministry and the Ministry of Planning are located in Sher-e-Bangla Nagar.[123] The Armed Forces Division of the government of Bangladesh and Bangladesh Armed Forces headquarters are located in Dhaka Cantonment.[123] Several important installations of the Bangladesh Army are also situated in Dhaka and Mirpur Cantonments. The Bangladesh Navy's principal administrative and logistics base, BNS Haji Mohshin, is located in Dhaka.[124] The Bangladesh Air Force maintains the BAF Bangabandhu Air Base and BAF Khademul Bashar Air Base in Dhaka.[125]

Dhaka hosts 54 resident embassies and high commissions and numerous international organizations. Most diplomatic missions are located in the Gulshan and Baridhara areas of the city. The Agargaon area near Parliament is home to the country offices of the United Nations, the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and the Islamic Development Bank.

Civic administration

History

The municipality of Dhaka was founded on 1 August 1864 and upgraded to "Metropolitan" status in 1978. In 1983, the Dhaka City Corporation was created as a self-governing entity to govern Dhaka.[126]

Under a new act in 1993, an election was held in 1994 for the first elected Mayor of Dhaka.[127] The Dhaka City Corporation ran the affairs of the city until November 2011.[128]

Municipal government

In 2011, Dhaka City Corporation was split into two separate corporations – Dhaka North City Corporation and Dhaka South City Corporation for ensuring better civic facilities.[129] These two corporations are headed by two mayors, who are elected by direct vote of the citizen for a 5-year period. The area within city corporations was divided into several wards, each having an elected commissioner. In total, the city has 130 wards and 725 mohallas.

- RAJUK is responsible for coordinating urban development in the Greater Dhaka area.[130]

- DMP is responsible for maintaining law and order within the metro area. It was established in 1976. DMP has 56 police stations as administrative units.[131][132]

Administrative agencies

Unlike other megacities worldwide, Dhaka is serviced by over two dozen government organizations under different ministries. Lack of coordination among them and centralization of all powers by the Government of Bangladesh keeps the development and maintenance of the city in a chaotic situation.[133]

| Agency | Service | Parent agency |

|---|---|---|

| Dhaka North City Corporation Dhaka South City Corporation |

Public service | Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Co-operatives ∟ Local Government Division |

| Dhaka Metropolitan Police | Law enforcement | Ministry of Home Affairs ∟ Bangladesh Police |

| RAJUK | Urban planning | Ministry of Housing and Public Works |

| Dhaka Electric Supply Company Limited Dhaka Power Distribution Company Limited |

Power distribution | Ministry of Power, Energy and Mineral Resources ∟ Power Division |

| Dhaka WASA | Water supply | Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Co-operatives ∟ Local Government Division |

| Dhaka Transport Coordination Authority | Transport | Ministry of Road Transport and Bridges ∟Road Transport and Highways Division |

Economy

As the most densely industrialized region of the country, the Greater Dhaka Area accounts for 35% of Bangladesh's economy.[24] The Globalization and World Cities Research Network ranks Dhaka as a beta− global city, in other words, one that is instrumental in linking their region into the world economy.[134] Major industrial areas are Tejgaon, Shyampur and Hazaribagh.[135] The city has a growing middle class, driving the market for modern consumer and luxury goods.[29][136] Shopping malls serve as vital elements in the city's economy. The city has historically attracted numerous migrant workers.[137] Hawkers, peddlers, small shops, rickshaw transport, roadside vendors and stalls employ a large segment of the population[137][138] – rickshaw drivers alone number as many as 400,000.[139] Half the workforce is employed in household and unorganised labour, while about 800,000 work in the textile industry. The unemployment rate in Dhaka was 23% in 2013.[140]

Almost all large local conglomerates have their corporate offices located in Dhaka. Microcredit also began here and the offices of the Nobel Prize-winning Grameen Bank[141] and BRAC (the largest non-governmental development organisation in the world) are based in Dhaka.[142] Urban developments have sparked a widespread construction boom; new high-rise buildings and skyscrapers have changed the city's landscape.[136] Growth has been especially strong in the finance, banking, manufacturing, telecommunications and service sectors, while tourism, hotels and restaurants continue as important elements of the Dhaka economy.[137]

Dhaka has rising traffic congestion and inadequate infrastructure; the national government has recently implemented a policy for rapid urbanization of surrounding areas and beyond by the introduction of a ten-year relief on income tax for new construction of facilities and buildings outside Dhaka.[143]

CBDs

The Dhaka metropolitan area boasts of several central business districts (CBDs). In the southern part of the city, the riverfront of Old Dhaka is home to many small businesses, factories and trading companies. Near Old Dhaka lies Motijheel, which is the biggest CBD in Bangladesh. The Motijheel area developed since the 1960s. Motijheel is home to the Bangladesh Bank, the nation's central bank; as well as the headquarters of the largest state-owned banks, including Janata Bank, Pubali Bank, Sonali Bank and Rupali Bank. By the 1990s, the affluent residential neighborhoods of Gulshan, Banani and Uttara in the northern part of the city became major business centers and now hosts many international companies operating in Bangladesh. The Purbachal New Town Project is planned as the city's future CBD.

The following is a list of the main CBDs in Dhaka.

- Motijheel

- Kawran Bazar

- Paltan

- Dhanmondi

- Gulshan

- Banani

- Uttara

- Mirpur

- Bashundhara Residential Area

- Panthapath

- Maghbazar

- Mohakhali

Industrial areas

- Tejgaon

- Old Dhaka

- Savar

Trade associations

Major trade associations based in the city include:

- Federation of Bangladesh Chambers of Commerce & Industries (FBCCI)

- Dhaka Chamber of Commerce & Industry (DCCI)

- Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce and Industry (MCCI)

- Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA)

- Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BKMEA)

- Newspaper Owners' Association of Bangladesh (NOAB)

- Real Estate and Housing Association of Bangladesh (REHAB)

Stock market

The Dhaka Stock Exchange (DSE) had a market capitalization of BDT 5,136,979.000 million in 2021.[144] Some of the largest companies listed on the DSE include:[145]

- Grameenphone

- BEXIMCO

- BSRM

- Titas Gas

- Summit Group

- The City Bank

- BRAC Bank

- IDLC Finance Limited

- Square Pharmaceuticals

- Eastern Bank Limited

- Orion Group

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 335,760 | — |

| 1961 | 507,921 | +51.3% |

| 1971 | 1,373,718 | +170.5% |

| 1981 | 3,265,663 | +137.7% |

| 1991 | 6,620,697 | +102.7% |

| 2001 | 10,284,947 | +55.3% |

| 2011 | 14,730,537 | +43.2% |

| 2021 | 21,741,090 | +47.6% |

| for Dhaka Agglomeration:[146] | ||

The city, in combination with localities forming the wider metropolitan area, is home to over 22 million as of 2022.[147] The population is growing by an estimated 3.3% per year,[147] one of the highest rates among Asian cities.[137] The continuing growth reflects ongoing migration from rural areas to the Dhaka urban region, which accounted for 60% of the city's growth in the 1960s and 1970s. More recently, the city's population has also grown with the expansion of city boundaries, a process that added more than a million people to the city in the 1980s.[137] According to the Far Eastern Economic Review, Dhaka will be home to 25 million people by the end of 2025.[148]

Ethnicity

The city population is composed of people from virtually every region of Bangladesh. The long-standing inhabitants of the old city are known as Dhakaite and have a distinctive dialect and culture. Dhaka is also home to a large number of Bihari refugees, who are descendants of migrant Muslims from eastern India during 1947 and settled down in East Pakistan. The correct population of Biharis living in the city is ambiguous, but it is estimated that there are at least 300,000 Urdu-speakers in all of Bangladesh, mostly residing in old Dhaka and in refugee camps in Dhaka, although official figures estimate only 40,000.[149][150][151] Between 15,000 and 20,000 of the Rohingya, Santal, Khasi, Garo, Chakma and Mandi tribal peoples reside in the city.[152]

Language

Most residents of Dhaka speak Bengali, the national language. Many distinctive Bengali dialects and regional languages such as Dhakaiya Kutti, Chittagonian and Sylheti are also spoken by segments of the population. English is spoken by a large segment of the population, especially for business purposes. The city has both Bengali and English newspapers. Urdu, including Dhakaiya Urdu, is spoken by members of several non-Bengali communities, including the Biharis.[153]

Literacy

The literacy rate in Dhaka is also increasing quickly. It was estimated at 69.2% in 2001. The literacy rate had gone up to 74.6% by 2011[154] which is significantly higher than the national average of 72%.[155]

Religion

Islam is the dominant religion of the city, with 19.3 million of the city's population being Muslim, and a majority belonging to the Sunni sect. There is also a small Shia sect, and an Ahmadiya community. Hinduism is the second-largest religion numbering around 1.47 million adherents. Smaller segments represent 1% and practice Christianity and Buddhism. In the city proper, over 8.5 million of the 8.9 million residents are Muslims, while 320,000 are Hindu and nearly 50,000 Christian.[157][156]

Culture

Literature

Dhaka is a major center for Bengali literature. It has been the hub of Bengali Muslim literature for more than a century. Its heritage also includes historic Urdu and Persian literary traditions. The Soldier in the Attic by Akhteruzzaman Elias is considered to be one of the best depictions of life in Old Dhaka and is set during Bengali uprisings in 1969. A Golden Age by Tahmima Anam is also set in Dhaka during the Bangladeshi war of independence and includes references to the Dhaka Club, the Dhaka University and the Dhanmondi area. The Dark Diamond by Shazia Omar traverses through Dhaka's history, beginning with the rule of Shaista Khan in the Mughal period.[158]

Festivals

Annual celebrations for Language Martyrs' Day (21 February), Independence Day (26 March), and Victory Day (16 December) are prominently celebrated across the city. Dhaka's people congregate at the Shaheed Minar and the Jatiyo Smriti Soudho to remember the national heroes of the liberation war. These occasions are observed with public ceremonies and rallies on public grounds. Many schools and colleges organise fairs, festivals and concerts in which citizens from all levels of society participate.[159] Pohela Baishakh, the Bengali New Year, falls annually on 14 April and is popularly celebrated across the city.[159] Large crowds of people gather on the streets of Shahbag, Ramna Park and the campus of the University of Dhaka for celebrations. Pahela Falgun, the first day of spring of the month Falgun in the Bengali calendar, is also celebrated in the city in a festive manner.[160] This day is marked with colourful celebration and traditionally, women wear yellow saris to celebrate this day. This celebration is also known as Basanta Utsab (Spring Festival). Nabanna is a harvest celebration, usually celebrated with food and dance and music on the 1st day of the month of Agrahayan of the Bengali year. Birthdays of Rabindranath Tagore and Kazi Nazrul Islam are observed respectively as Rabindra Jayanti and Nazrul Jayanti. The Ekushey Book Fair, which is arranged each year by Bangla Academy, takes place for the whole month of February. This event is dedicated to the martyrs who died on 21 February 1952 in a demonstration calling for the establishment of Bengali as one of the state languages of former East Pakistan. Shakrain Festival is an annual celebration observed with the flying of kites.[161] It is usually observed in the old part of the city at the end of Poush, the ninth month of the Bengali calendar (14 or 15 January in the Gregorian calendar).

The Islamic festivals of Eid ul-Fitr, Eid ul-Adha, Eid-E-Miladunnabi and Muharram; the Hindu festival of Durga Puja; the Buddhist festival of Buddha Purnima; and the Christian festival of Christmas witness widespread celebrations across the city. Despite the growing popularity of music groups and rock bands, traditional folk music remains widely popular.[162] The works of the national poet Kazi Nazrul Islam, national anthem writer Rabindranath Tagore and mystic saint songwriter Lalon have a widespread following across Dhaka.[163] The Baily Road area is known as Natak Para (Theatre Neighbourhood) which is the center of Dhaka's thriving theatre movement.[164] For much of recent history, Dhaka was characterized by roadside markets and small shops that sold a wide variety of goods.[165] Recent years have seen the widespread construction of shopping malls.[166] Two of the largest shopping malls in the city and the wider South Asian region are the Jamuna Future Park and Bashundhara City.

.jpg.webp)

Cultural institutions

- Bengal Foundation

- Chhayanaut

- Institute of Fine Arts

- Nazrul Institute

- Samdani Art Foundation

- Shilpakala Academy

Annual and biennial cultural events

- Bengal Classical Music Festival

- Chobi Mela International Photography Festival

- Dhaka Art Summit

- Dhaka Lit Fest

- Dhaka World Music Festival

- Dhaka International Book Fair

- Dhaka International Trade Fair

- Ekushey Book Fair

Cuisine

Historically, Dhaka has been the culinary capital of Bengal in terms of Mughlai cuisine. A distinct variant of Bengali-Mughlai cuisine evolved in the city. Chefs from Dhaka, the former Mughal provincial capital, served in the kitchens of the Nawabs of Bengal in Murshidabad. They invented the kachi biryani, which is a variant of biryani with mutton steaks and potatoes. One of the longest surviving outlets serving authentic kachi biryani is Fakhruddin's.[167] Kachi biryani is highly popular in Bangladeshi cuisine, with food critic and former MasterChef Australia judge Matt Preston praising its use of potatoes.[168] The Nawabi cuisine of Dhaka was notable for its patishapta dessert and the Kubali pulao. The korma recipe of the Nawab family was included by Madhur Jaffrey in her cookbook "Madhur Jaffrey's Ultimate Curry Bible".[169] Bakarkhani breads from Dhaka were served in the courts of Mughal rulers.[170] Since 1939, Haji biryani has been a leading biryani restaurant of the city. Dhaka also has a style of Murg Pulao (chicken biryani) which uses turmeric and malai (cream of milk) together.[171] Along with South Asian cuisine, a large variety of Western and Chinese cuisine is served at numerous restaurants and eateries.[136] Upmarket areas include many Thai, Japanese and Korean restaurants.[172]

During Ramadan, Chowkbazaar becomes a busy marketplace for iftar items. The jilapi of Dhaka are much thicker than counterparts in India and Pakistan.[173] The Shahi jilapi (king's jilapi) is one of the thickest jilapi produced. The phuchka is a popular street food. Dhaka hosts an array of Bengali dessert chains which sell a wide variety of sweets. Samosas and shingaras are also widely eaten traditional snacks. In recent years, the number of Bangladeshi-owned burger outlets have increased across the city. Notable bakeries include the Prince of Wales bakery in Old Dhaka and the Cooper's chain.

Architecture

The architectural history of Dhaka can be subdivided into the Mughal, British and modern periods. As a result, Dhaka has landmarks of Mughal architecture, Indo-Saracenic architecture and modernist architecture. The oldest brick structure in the city is the Binat Bibi Mosque, which was built in 1454 in the Narinda area of Dhaka during the reign of the Sultan Nasiruddin Mahmud Shah (r. 1435 – 1459) of the Bengal Sultanate.[174][175] Old Dhaka is home to over 2000 buildings built between the 16th and 19th centuries, which form an integral part of Dhaka's cultural heritage. Modern Dhaka is often criticized as a concrete jungle.[176] But there are hidden gems in the concrete jungle, including traces of Dhaka's Mughal and colonial past; as well as landmarks of modernist architecture.

In the old part of the city, the fading grandeur of the Mughal era is evident in the crumbling, neglected caravanserai like Bara Katra and Choto Katra. Some structures like the Nimtali arch have been restored. The old city features narrow alleyways with high-walled lanes and houses with indoor courtyards.[60] The early 20th century government quarter in Ramna includes stately colonial buildings set amidst gardens and parks.[60] Among colonial buildings, the Curzon Hall stands out for "synthesizing imperial grandiosity with sporadic Mughal motifs, the imposing building symbolizes how the colonial administration sought to include elements of 'local' architecture as a way to show its sensitivity to native culture, which they hoped would counter growing nationalist sentiments among the natives".[177]

Amongst modernist buildings, the Grameenphone headquarters is described as "a paradigm setter for corporate Bangladesh".[177] The Museum of Independence and its attached national monument were inspired by the "land-water mysticism of deltaic Bengal" and the "evocative expansiveness of a Roman forum or the geographical assemblage of an Egyptian mastaba sanctuary".[177] Dhaka's Art Institute, designed by Muzharul Islam, was the pioneering building of Bengali regional modernism.[177] The vast expanse of the national parliament complex was designed by Louis Kahn. It is celebrated as Dhaka's pre-eminent civic space.[178] The national parliament complex comprises 200 acres (800,000 m2) in the heart of the city.[179] The Kamalapur railway station was designed by American architect Robert Boughey.[180] In the last few decades, Bangladesh's new wave of cultural architecture has been influenced by Bengali aesthetics and the environment.[181] City Centre Bangladesh is currently the tallest building in the city.

- Architecture of Dhaka

Haturia House, a single floor house built in the Curzon Hall style

Haturia House, a single floor house built in the Curzon Hall style Ruplal House and the Buriganga River

Ruplal House and the Buriganga River Ahsan Manzil was the residence of the Nawabs of Dhaka

Ahsan Manzil was the residence of the Nawabs of Dhaka Khan Mohammad Mridha Mosque

Khan Mohammad Mridha Mosque A building designed by Rafiq Azam

A building designed by Rafiq Azam Chistia Palace is a modernist castle and one of the most famous private residences in Dhaka

Chistia Palace is a modernist castle and one of the most famous private residences in Dhaka.jpg.webp) ABC Tower on Kemal Ataturk Avenue

ABC Tower on Kemal Ataturk Avenue Bait Ur Rouf Mosque designed by Marina Tabassum

Bait Ur Rouf Mosque designed by Marina Tabassum Gulshan Society Mosque designed by Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury

Gulshan Society Mosque designed by Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury

Publishing and media

In 1849, the Kattra Press became the first printing press in the city. The name eludes to the katra, the Bengali word for caravanserai. In 1856, Dacca News became the first English language newspaper in the city. The Dacca News Press was the first commercial printing press in the city. Books published in Dhaka stirred discourse in the social and literary circles of Bengal. The Bengal Library Catalogue records the expansion of the publishing industry during the 1860s. Between 1877 and 1895, there were 45 printing presses in Dhaka. Between 1863 and 1900, more than a hundred Islamic puthi were published in Dhaka. Bookshops sprang up in Chowkbazaar, Islampur, Mughaltuli and Patuatuli. Albert Library was a den for leftwing activists.[25] After partition, the number of publishing houses in Dhaka rose from 27 in 1947 to 88 in 1966.[25] Prominent bookshops included Wheeler's bookstall and Presidency Library. Banglabazaar has since become the hub of the book trade.[25] Bookworm is a famous local book shop which has been located adjacent to the Prime Minister's Office for three decades, until being ordered to relocate in 2022.[182][183][184]

Dhaka is the center of the national media in Bangladesh. It is home to the state-owned Bangladesh Television and Bangladesh Betar. In recent years, the number of privately-owned television channels and radio stations have increased greatly. There are over two dozen Bengali language television channels in the private sector, including 24 hour news channels. Radio is also popular across the city. Dhaka is home to national newspapers, including Bengali newspapers like Prothom Alo,[185] Ittefaq, Inqilab, Janakantha, and Jugantor; as well as English language newspapers The Daily Star,[186] The Financial Express, The Business Standard, Dhaka Tribune, and New Age. Broadcast media based in Dhaka include Gaan Bangla, Banglavision, DBC News, Somoy TV, Independent TV and Ekattor.

Education and research

Dhaka has the largest number of schools, colleges and universities of any Bangladeshi city. The education system is divided into five levels: primary (from grades 1 to 5), junior (from grades 6 to 8), secondary (from grades 9 to 10), higher secondary (from grades 11 to 12) and tertiary.[187] The five years of primary education concludes with a Primary School Completion (PSC) Examination, the three years of junior education concludes with Junior School Certificate (JSC) Examination. Next, two years of secondary education concludes with a Secondary School Certificate (SSC) Examination. Students who pass this examination proceed to two years of higher secondary or intermediate training, which culminate in a Higher Secondary School Certificate (HSC) Examination.[187] Education is mainly offered in Bengali. However, English is also widely taught and used. Many Muslim families send their children to attend part-time courses or even to pursue full-time religious education alongside other subjects, which is imparted in Bengali and Arabic in schools, colleges and madrasas.[187]

There are 52 universities in Dhaka. Dhaka College is the oldest institution for higher education in the city and among the earliest established in British India, founded in 1841. Since independence, Dhaka has seen the establishment of numerous public and private colleges and universities that offer undergraduate and graduate degrees as well as a variety of doctoral programmes.[188] The University of Dhaka is the oldest public university[189] in the country which has more than 30,000 students and 1,800 faculty staff. It was established in 1921 being the first university in the region. The university has 23 research centers and 70 departments, faculties and institutes.[190] Eminent seats of higher education include Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET), Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU), Jagannath University and Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University. Dhaka Medical College and Sir Salimullah Medical College are two of the best medical colleges in the country.[191] Founded in 1875, the Dhaka Medical School was the first medical school in British East Bengal, which became Sir Salimullah Medical College in 1962.[192] Other government medical colleges are Shaheed Suhrawardy Medical College, Mugda Medical College and Armed Forces Medical College, Dhaka.

Learned societies and think tanks

- Asiatic Society of Bangladesh

- Atomic Energy Centre, Dhaka

- Bangla Academy

- Bangladesh Academy of Sciences

- Bangladesh Enterprise Institute

- Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies

- Bangladesh Center for Advanced Studies

- Bangladesh Institute of Law and International Affairs

- Bangladesh Institute of Peace & Security Studies

- Centre for Policy Dialogue

- Centre on Integrated Rural Development for Asia and the Pacific

- International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh

- International Jute Study Group

- IBA Dhaka

- Space Research and Remote Sensing Organization

- Yunus Centre

Sports

Cricket and football are the two most popular sports in Dhaka and across the nation.[193] Teams are fielded in intra-city and national competitions by many schools, colleges and private entities. The Dhaka Metropolis cricket team represents Dhaka City in the National Cricket League, the oldest domestic first-class cricket competition in Bangladesh.[194] The Dhaka Premier League is the only domestic List A cricket tournament now in Bangladesh. It gained List A status in 2013–14 season.[195] In domestic Twenty20 cricket, Dhaka has a Bangladesh Premier League (BPL) franchise known as Minister Dhaka.[196]

Dhaka has the distinction of having hosted the first official Test cricket match of the Pakistan cricket team in 1954 against India.[197] The Bangabandhu National Stadium was formerly the main venue for domestic and international cricket matches, but now exclusively hosts football matches.[197] It hosted the opening ceremony of the 2011 Cricket World Cup,[198] while the Sher-e-Bangla National Cricket Stadium, exclusively used for cricket, hosted 6 matches of the tournament including two quarter-final matches.[199] Dhaka has also hosted the South Asian Games three times, in 1985, 1993 and 2010. Dhaka is the first city to host the games three times. The Bangabandhu National Stadium was the main venue for all three editions.[200] Dhaka also hosted the ICC Men's T20 World Cup, along with Chittagong and Sylhet, in 2014.[201]

The Dhaka Derby between Mohammedan Sporting Club and Abahani, two of the most famous football teams in the country, maintaining a fierce rivalry over the years, especially in the Bangladesh Football Premier League and previously in the historic Dhaka League.[202] Along with the two Dhaka giants, Brothers Union and Muktijoddha KC are also among the well renowned clubs residing in the capital.[203] The Bangabandhu National Stadium, also known as the Dhaka Stadium, has been the main venue for the Bangladesh national football team and Bangladesh women's national football team, since 2005.[204] Dhaka Stadium has also hosted the SAFF Championship on three occasions. The stadium was used as the main venue for the 2003 SAFF Championship, which was Bangladesh's first ever SAFF triumph.[205]

The National Sports Council, responsible for promoting sports activities across the nation, is based in Dhaka. Dhaka also has stadiums largely used for domestic events such as the Bangladesh Army Stadium, the Bir Sherestha Shaheed Shipahi Mostafa Kamal Stadium, the Dhanmondi Cricket Stadium, the Maulana Bhasani Hockey Stadium and the Outer Stadium Ground.[206] The Dhaka University Ground and the BUET Sports Ground host many intercollegiate tournaments.[207]

There are two golf courses in Dhaka, Army Golf Club and Kurmitola Golf Club.[208]

Transport

Public transportation

Dhaka suffers some of the worst traffic congestion in the world. The city lacks an organized public transport system. Cycle rickshaws and auto rickshaws are the main mode of transport within the metro area, with close to 400,000 rickshaws running each day: the highest number in any city in the world.[136][209][210][211] However, only about 85,000 rickshaws are licensed by the city government.[137][212] Relatively low-cost and non-polluting cycle rickshaws are superior to private cars, which are exclusively responsible for Dhaka's congestion.[213] The government has overseen the replacement of two-stroke engine auto rickshaws with "green auto-rickshaws", which run on compressed natural gas.[214]

Public buses are operated by the state-run Bangladesh Road Transport Corporation (BRTC) and by numerous private companies and operators. There are three inter-district bus terminals in Dhaka, which are located in the Mohakhali, Saidabad and Gabtoli areas of the city. It is now planned to move three inter-district bus terminals to outside of the city.[215] Highway links to the Indian cities of Kolkata, Agartala, Guwahati and Shillong have been established by the BRTC and private bus companies which also run regular international bus services to those cities from Dhaka.[216] Limited numbers of taxis are available. It is planned to raise the total number of taxis to 18,000 gradually.[217][218][219] Ride-sharing services like Uber and Pathao as well as scooters and privately owned cars are popular modes of transportation.

Road

Dhaka is connected to the other parts of the country through highway and railway links. Five of the eight major national highways of Bangladesh start from the city: N1, N2, N3, N5 and N8. Dhaka is also directly connected to the two longest routes of the Asian Highway Network: AH1 and AH2, as well as to the AH41 route. Highway links to the Indian cities of Kolkata, Agartala, Guwahati and Shillong have been established by the BRTC and private bus companies which also run regular international bus services to those cities from Dhaka.[216][220] As of 2022, The elevated expressway is still under construction.[221] The Dhaka Elevated Expressway would run from Shahjalal International Airport-Kuril-Banani-Mohakhali-Tejgaon-Saatrasta-Moghbazar Rail Crossing-Khilgaon-Kamalapur-Golapbagh to Dhaka-Chittagong Highway at Kutubkhali Point. Dhaka Elevated Expressway is set to open in 2022 partially.[222] A second elevated expressway named Dhaka-Ashulia Elevated Expressway is expected to be opened in 2026.[223] Dhaka was introduced to Japanese automobiles in the late 1990's. This resulted in the car industry to bloom, but this also caused a rise in traffic to the streets of Dhaka.

Waterway

The Sadarghat River Port on the banks of the Buriganga River serves for the transport of goods and passengers upriver and to other ports in Bangladesh.[224] Inter-city and inter-district motor vessels and passenger-ferry services are used by many people to travel riverine regions of the country from the city. Water bus services are available on Buriganga River and Hatirjheel and Gulshan lakes. Water buses of the Buriganga River ferry passengers on the Sadarghat to Gabtali route.[225] Water taxis in Hatirjheel and Gulshan lakes provide connectivity via two routes, one route between Tejgaon and Gulshan and the other route between the Tejgaon and Rampura areas.[226]

Rail

Kamalapur railway station, situated in the north-east side of Motijheel, is the largest and busiest among the railway stations in the city.[180] It was designed by American architect Robert Boughey, and was completed in 1969.[227] The state-owned Bangladesh Railway provides suburban and national services, with regular express train services connecting Dhaka with other major urban areas, such as Chittagong, Rajshahi, Khulna, Sylhet and Rangpur.[228] The Maitree Express provides connection from Dhaka to Kolkata, one of the largest cities in India.[229]

In 2013, suburban services to Narayanganj and Gazipur cities were upgraded using diesel electric multiple unit trains.[230][231] The Dhaka Metro Rail feasibility study has been completed. A 20.1-kilometre (12.5 mi), $2.8-billion Phase 1 metro route is being negotiated by the Government with Japan International Cooperation Agency.[232] The first route, originally projected to start from Uttara, a northern suburb of Dhaka, to Sayedabad, in the south of the capital,[233] was eventually extended north to Uttara and truncated south to Motijheel.[234] Initiatives have been taken to extend MRT Line-6 from Motijheel to Kamalapur. Topographic Survey has already been completed. Social Survey in progress. The length of this part is 1.17 km. This will enable the passengers of Kamalapur railway station to travel by metro rail.[235] The route consists of 16 elevated stations each 180 metres (590 ft) long. Construction began on 26 June 2016.[236]

Air

Shahjalal International Airport, located 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) north of Dhaka city centre, is the largest and busiest international airport in the country.[237] The airport has an area of 1,981 acres (802 ha). The airport has a capacity of handling 15 million passengers annually,[238] and is predicted by the Civil Aviation Authority, Bangladesh to be sufficient to meet demand until 2026.[239] In 2014, it handled 6.1 million passengers, and 248,000 tonnes of cargo.[240] Average aircraft movement per day is around 190 flights.[241] It is the hub of all Bangladeshi airlines. Domestic service flies to Chittagong, Sylhet, Rajshahi, Cox's Bazar, Jessore, Barisal, Saidpur and international services fly to major cities in Asia, Europe and the Middle East.[242][243] A third international terminal is under construction and it is expected to be operational in 2023.[244] According to the project design, the third terminal will have 12 boarding bridges and 12 conveyor belts. The terminal will have 115 check-in counters, 59 immigration desks. Another large scale airport known as Bangabandhu international airport has been proposed to be built outside Dhaka.

Twin towns – sister cities

See also

- List of districts and suburbs of Dhaka

- List of places of worship in Dhaka city

- List of largest cities

- List of metropolitan areas in Asia

- List of most expensive cities for expatriate employees

- List of urban agglomerations in Asia

- Mia Shaheb Moidan

References

- "The tales of urban street children: Is there anything we could do?". Dhaka Tribune. 10 December 2019.

- "Are we willing to know more of Dhaka?". The Daily Star. 4 May 2018.

- "Hasan Mahmud states 3 reasons behind low voter turnout". The Daily Star. UNB. 2 February 2020. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Partha Pratim Bhattacharjee; Mahbubur Rahman Khan (7 May 2016). "Govt to double size of Dhaka city area". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "Dhaka City expands by more than double after inclusion of 16 union councils". bdnews24.com. 9 May 2016. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "Dhaka Metropolitan City Area". Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- "Dhaka, Bangladesh Map". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 7 January 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- "Dhaka (Bangladesh): City Districts and Subdistricts - Population Statistics, Charts and Map". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "Population & Housing Census-2011" (PDF). Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. p. 41. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- "Dhaka, Bangladesh GDP and Income Distribution". www.canback.com. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Choguill, C.L. (2012). New Communities for Urban Squatters: Lessons from the Plan That Failed in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Springer Science & Business Media. p. viii. ISBN 978-1-4613-1863-7. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- "Population & Housing Census-2011" (PDF). Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- "The World's Most Densely Populated Cities". WorldAtlas. 4 October 2020.

- Demographia World Urban Areas 17th Annual Edition: 202106 (PDF). Demographia. Demographia.

- Ferreira, Luana (3 September 2021). "Here's How Many People Live In The Most Densely Populated City On Earth". Grunge.com. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- "Dhaka, Bangladesh GDP and Income Distribution". www.canback.com. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "Forum". The Daily Star. Archive.thedailystar.net. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- "Islam Khan Chisti". Banglapedia. 18 June 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- Khondker, Kamrun Nessa (December 2012). Mughal River Forts in Bangladesh (1575-1688): An Archaeological Appraisal (PDF) (PhD). School of History, Archaeology and Religion, Cardiff University.

- Hough, Michael (2004) [First published 1995]. Cities and Natural Process: A Basis for Sustainability (2nd ed.). Psychology Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-415-29854-4. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan (1962) [First published 1956]. Dacca: A record of its changing fortunes (2nd ed.). Mrs. Safiya S. Dani. pp. 98, 118–119, 126. OCLC 987755973.

- "The World According to GaWC 2020". GaWC - Research Network. Globalization and World Cities. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- Rezaul Karim (24 February 2017). "Dhaka's economic activities unplanned: analysts". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- "How Partition impacted the Dhaka book trade". The Daily Star. 19 August 2022.

- "Dhaka and Akhtaruzzaman Elias". 16 June 2022.

- "Dhaka". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- "Islam Khan Chisti". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- Chowdhury, A.M. (23 April 2007). "Dhaka". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- Mamoon, Muntassir (2010) [First published 1993]. Dhaka: Smiriti Bismiritir Nogori. Anannya. p. 94.

- Dhaka City Corporation (5 September 2006). "Pre-Mughal Dhaka (before 1608)". Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- "From Jahangirnagar to Dhaka". Forum. The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- Historical Background for the Establishment of Naib-Nazimship (Deputy Governorship for the four Divisions of Subah Bangla), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh

- Richard Maxwell Eaton (1996), The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760, page 202, University of California Press

- Om Prakash, "Empire, Mughal", in John J. McCusker (ed.), History of World Trade Since 1450, vol. 1, Macmillan Reference USA, 2006, pp. 237–240, World History in Context. Retrieved 3 August 2017

- John F. Richards (1995), The Mughal Empire, page 202, Cambridge University Press

- Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857). Routledge. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- "A discovery that may save Bara Katra". The Daily Star. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- Kraas, Frauke; Aggarwal, Surinder; Coy, Martin; Mertins, Günter, eds. (2013). Megacities: Our Global Urban Future. Springer. p. 60. ISBN 978-90-481-3417-5.

- "State of Cities: Urban Governance in Dhaka" (PDF). BRAC University. May 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- Shay, Christopher. "Travel – Saving Dhaka's heritage". BBC. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- https://www.thedailystar.net/star-weekend/heritage/legends-lalbagh-95554

- Golam Rabbani (1997). Dhaka: From Mughal Outpost to Metropolis. Upl. pp. 14–19. ISBN 978-984-05-1374-1.

- Lloyd's Evening Post, 16-18 May, 1764

- Historical Background for the Establishment of Naib-Nazimship (Deputy Governorship for the four Divisions of Subah Bangla), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh

- Srangio, Sebastian (1 October 2010). "Dhaka: Saving Old Dhaka's Landmarks". The Caravan. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015.

- "Worldview". Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- https://www.livehistoryindia.com/story/religious-places/sunderbans

- https://www.livehistoryindia.com/story/religious-places/sunderbans

- "Which India is claiming to have been colonizsed?". The Daily Star (Op-ed). 31 July 2015. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- Lalbagh Kella (Lalbagh Fort) Dhaka Bangladesh 2011 54.JPG

- "The rise and fall of the Dutch in Dhaka". 5 February 2018.

- "French, the - Banglapedia".

- "Você fala Bangla?". 24 January 2014.

- "Portuguese influence in Bengal | the Asian Age Online, Bangladesh".

- Ali, Ansar; Chaudhury, Sushil; Islam, Sirajul (2012). "Armenians, The". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- https://www.thejc.com/lifestyle/features/the-extraordinary-story-of-the-bangladesh-jews-1.58433

- "History of the Greek community in Dhaka". 11 January 2021.

- Karim, Abdul (2012). "Iranians, The". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- "Out of place, out of time". 26 March 2019.

- Railways, steamer services, postal departments and lower civil services

- https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php/Saltpetre

- https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Salt_Industry

- https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Americans,_The

- https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Americans,_The

- "Rare 1857 reports on Bengal uprisings". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- "From Elephants to Motor Cars". The Daily Star. 24 September 2018. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- "Dhaka WASA". Dwasa.org.bd. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2015.