Urdu

Urdu (/ˈʊərduː/;[11] Urdu: اُردُو, ALA-LC: Urdū) is an Indo-Aryan language spoken chiefly in South Asia.[12][13] It is the national language and lingua franca of Pakistan, where it is also an official language alongside English.[14] In India, Urdu is an Eighth Schedule language whose status and cultural heritage is recognized by the Constitution of India;[15][16] it also has an official status in several Indian states.[note 1][14] In Nepal, Urdu is a registered regional dialect.[17]

| Urdu | |

|---|---|

| Standard Urdu | |

| اردو | |

"Urdu" written in the Nastaliq calligraphic hand | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈʊrduː] ( |

| Native to | India and Pakistan |

| Region | Hindustani Belt and Deccan (in India) Whole Country (in Pakistan) |

| Ethnicity | Urdu-speaking people[1] |

Native speakers | 51 million (India; 2011 census) 15 million (Pakistan; 2017 census) 691,546 (Nepal; 2011 census) 3 million (international) Secondary speakers: 149 million (Pakistan, 2018) 12 million (India, 2011) |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | Shauraseni Prakrit

|

| Dialects |

|

| |

Signed forms | Indo-Pakistani Sign Language |

| Official status | |

Official language in | (national, official) |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | National Language Promotion Department (Pakistan) National Council for Promotion of Urdu Language (India) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ur |

| ISO 639-2 | urd |

| ISO 639-3 | urd |

| Glottolog | urdu1245 |

| Linguasphere | 59-AAF-q |

Areas in India and Pakistan where Urdu is either official or co-official

Areas where Urdu is neither official nor co-official | |

The Urdu language has been described as a Persianised register of the Hindustani language;[18][19] Urdu and Hindi share a common Sanskrit- and Prakrit-derived vocabulary base, phonology, syntax, and grammar, making them mutually intelligible during colloquial communication.[20][21] While formal Urdu draws literary, political, and technical vocabulary from Persian,[22] formal Hindi draws these aspects from Sanskrit; consequently, the two languages' mutual intelligibility effectively decreases as the factor of formality increases.

In 1837, the British East India Company chose Urdu as the language to replace Persian across northern India during Company rule; Persian had until this point served as the court language of various Indo-Islamic empires.[23] Religious, social, and political factors arose during the European colonial period that advocated a distinction between Urdu and Hindi, leading to the Hindi–Urdu controversy.[24] Urdu became a literary language in the 18th century and two similar standard forms came into existence in Delhi and Lucknow. Since the partition of India in 1947, a third standard has arisen in the Pakistani city of Karachi.[25][26] Deccani, an older form used in Deccan, became a court language of the Deccan sultanates by the 16th century.[27][26]

According to 2018 estimates by Ethnologue, Urdu is the 10th-most widely spoken language in the world, with 230 million total speakers, including those who speak it as a second language.[28]

Etymology

The name Urdu was first used by the poet Ghulam Hamadani Mushafi around 1780 for Hindustani language[29][30] even though he himself also used Hindvi term in his poetry to define the language.[31] Ordu means army in the Turkic. In late 18th century, it was known as Zaban-e-Urdu ay Mualla زبانِ اردو اے معلّی means language of the exalted camp.[32][33][34] Earlier it was known as Hindvi, Hindi and Hindustani.[30][35]

History

Urdu, like Hindi, is a form of Hindustani.[36][37][38] Some linguists have suggested that the earliest forms of Urdu evolved from the medieval (6th to 13th century) Apabhraṃśa register of the preceding Shauraseni language, a Middle Indo-Aryan language that is also the ancestor of other modern Indo-Aryan languages.[39][40]

Origins

In the Delhi region of India the native language was Khariboli, whose earliest form is known as Old Hindi (or Hindavi).[41][42][43][44] It belongs to the Western Hindi group of the Central Indo-Aryan languages.[45][46] The contact of Hindu and Muslim cultures during the period of Islamic conquests in the Indian subcontinent (12th to 16th centuries) led to the development of Hindustani as a product of a composite Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb.[47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54]

In cities such as Delhi, the Indian language Old Hindi began to acquire many Persian loanwords and continued to be called "Hindi" and later, also "Hindustani".[43][35][55][30][45] An early literary tradition of Hindavi was founded by Amir Khusrau in the late 13th century.[56][57][58][59] After the conquest of the Deccan, and a subsequent immigration of noble Muslim families into the south, a form of the language flourished in medieval India as a vehicle of poetry, (especially under the Bahmanids),[60] and is known as Dakhini, which contains loanwords from Telugu and Marathi.[61][62][63]

From the 13th century until the end of the 18th century the language now known as Urdu was called Hindi,[30] Hindavi, Hindustani,[35] Dehlavi,[64] Lahori,[64] and Lashkari.[65] The Delhi Sultanate established Persian as its official language in India, a policy continued by the Mughal Empire, which extended over most of northern South Asia from the 16th to 18th centuries and cemented Persian influence on Hindustani.[66][55]

According to the Tashih Gharaib-ul-Lughat by Khan-i Arzu, the "Zaban-e Urdu-e Shahi" [language of the Imperial Camp] had attained special importance in the time of Alamgir".[67] By the end of the reign of Aurangzeb in the early 1700s, the common language around Delhi began to be referred to as Zaban-e-Urdu,[33] a name derived from the Turkic word ordu (army) or orda and is said to have arisen as the "language of the camp", or "Zaban-i-Ordu" means "Language of High camps"[32] or natively "Lashkari Zaban" means "Language of Army".[68] It is recorded that Aurangzeb spoke in Hindvi, which was most likely Persianized, as there are substantial evidence that Hindvi was written in the Persian script in this period.[69]

During this time period Urdu was referred to as "Moors", which simply meant Muslim,[70] by European writers.[71] John Ovington wrote in 1689:[72]

The language of the Moors is different from that of the ancient original inhabitants of India, but is oblig'd to these Gentiles for its characters. For though the Moors dialect is peculiar to themselves, yet it is destitute of Letters to express it; and therefore in all their Writings in their Mother Tongue, they borrow their letters from the Heathens, or from the Persians, or other Nations.

The name Urdu was first introduced by the poet Ghulam Hamadani Mushafi around 1780.[29][30] As a literary language, Urdu took shape in courtly, elite settings.[73][74] While Urdu retained the grammar and core Indo-Aryan vocabulary of the local Indian dialect Khariboli, it adopted the Nastaleeq writing system[45][75] – which was developed as a style of Persian calligraphy.[76]

Other historical names

Throughout the history of the language, Urdu has been referred to by several other names: Hindi, Hindavi, Rekhta, Urdu-e-Muallah, Dakhini, Moors and Dehlavi.

In 1773, the Swiss-French soldier Antoine Polier notes that the English liked to use the name "Moors" for Urdu:[77]

I have a deep knowledge [je possède à fond] of the common tongue of India, called Moors by the English, and Ourdouzebain by the natives of the land.

Several works of Sufi writers like Ashraf Jahangir Semnani used similar names for the Urdu language. Shah Abdul Qadir Raipuri was the first person who translated The Quran into Urdu.[78]

During Shahjahan's time, the Capital was relocated to Delhi and named Shahjahanabad and the Bazar of the town was named Urdu e Muallah.[79][80]

In the Akbar era the word Rekhta was used to describe Urdu for the first time. It was originally a Persian word that meant "to create a mixture". Khusru was the first person to use the same word for Poetry.

Colonial period

Before the standardization of Urdu into colonial administration, British officers often referred to the language as "Moors" or "Moorish jargon". John Gilchrist was the first in British India to begin a systematic study on Urdu, and began to use the term "Hindustani" what the majority of Europeans called "Moors", authoring the book The Strangers's East Indian Guide to the Hindoostanee Or Grand Popular Language of India (improperly Called Moors).[81]

Urdu was then promoted in colonial India by British policies to counter the previous emphasis on Persian.[82] In colonial India, "ordinary Muslims and Hindus alike spoke the same language in the United Provinces in the nineteenth century, namely Hindustani, whether called by that name or whether called Hindi, Urdu, or one of the regional dialects such as Braj or Awadhi."[83] Elites from Muslim communities, as well as a minority of Hindu elites, such as Munshis of Hindu origin,[84] wrote the language in the Perso-Arabic script in courts and government offices, though Hindus continued to employ the Devanagari script in certain literary and religious contexts.[83][75][85] Urdu and English replaced Persian as the official languages in northern parts of India in 1837.[86] In colonial Indian Islamic schools, Muslims were taught Persian and Arabic as the languages of Indo-Islamic civilisation; the British, in order to promote literacy among Indian Muslims and attract them to attend government schools, started to teach Urdu written in the Perso-Arabic script in these governmental educational institutions and after this time, Urdu began to be seen by Indian Muslims as a symbol of their religious identity.[83] Hindus in northwestern India, under the Arya Samaj agitated against the sole use of the Perso-Arabic script and argued that the language should be written in the native Devanagari script,[87] which triggered a backlash against the use of Hindi written in Devanagari by the Anjuman-e-Islamia of Lahore.[87] Hindi in the Devanagari script and Urdu written in the Perso-Arabic script established a sectarian divide of "Urdu" for Muslims and "Hindi" for Hindus, a divide that was formalised with the partition of colonial India into the Dominion of India and the Dominion of Pakistan after independence (though there are Hindu poets who continue to write in Urdu, including Gopi Chand Narang and Gulzar).[88][89]

Post-Partition

Urdu was chosen as an official language of Pakistan in 1947 as it was already the lingua franca for Muslims in north and northwest British India,[90] although Urdu had been used as a literary medium for colonial Indian writers from the Bombay Presidency, Bengal, Orissa Province, and Tamil Nadu as well.[91]

In 1973, Urdu was recognised as the sole national language of Pakistan – although English and regional languages were also granted official recognition.[92] Following the 1979 Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan and subsequent arrival of millions of Afghan refugees who have lived in Pakistan for many decades, many Afghans, including those who moved back to Afghanistan,[93] have also become fluent in Hindi-Urdu, an occurrence aided by exposure to the Indian media, chiefly Hindi-Urdu Bollywood films and songs.[94][95][96]

There have been attempts to purge Urdu of native Prakrit and Sanskrit words, and Hindi of Persian loanwords – new vocabulary draws primarily from Persian and Arabic for Urdu and from Sanskrit for Hindi.[97][98] English has exerted a heavy influence on both as a co-official language.[99] According to Bruce (2021), Urdu has adapted English words since the eighteenth century.[100] A movement towards the hyper-Persianisation of an Urdu emerged in Pakistan since its independence in 1947 which is "as artificial as" the hyper-Sanskritised Hindi that has emerged in India;[101] hyper-Persianisation of Urdu was prompted in part by the increasing Sanskritisation of Hindi.[102] However, the style of Urdu spoken on a day-to-day basis in Pakistan is akin to neutral Hindustani that serves as the lingua franca of the northern Indian subcontinent.[103][104]

Since at least 1977,[105] some commentators such as journalist Khushwant Singh have characterised Urdu as a "dying language", though others, such as Indian poet and writer Gulzar (who is popular in both countries and both language communities, but writes only in Urdu (script) and has difficulties reading Devanagari, so he lets others 'transcribe' his work) have disagreed with this assessment and state that Urdu "is the most alive language and moving ahead with times" in India.[106][107][108][105][109][110][111] This phenomenon pertains to the decrease in relative and absolute numbers of native Urdu speakers as opposed to speakers of other languages;[112][113] declining (advanced) knowledge of Urdu's Perso-Arabic script, Urdu vocabulary and grammar;[112][114] the role of translation and transliteration of literature from and into Urdu;[112] the shifting cultural image of Urdu and socio-economic status associated with Urdu speakers (which negatively impacts especially their employment opportunities in both countries),[114][112] the de jure legal status and de facto political status of Urdu,[114] how much Urdu is used as language of instruction and chosen by students in higher education,[114][112][113][111] and how the maintenance and development of Urdu is financially and institutionally supported by governments and NGOs.[114][112]

In India, although Urdu is not and never was used exclusively by Muslims (and Hindi never exclusively by Hindus),[111][115] the ongoing Hindi–Urdu controversy and modern cultural association of each language with the two religions has led to fewer Hindus using Urdu.[111][115] In the 20th century, Indian Muslims initially more or less gradually collectively embraced Urdu[115] (for example, 'post-independence Muslim politics of Bihar saw a mobilisation around the Urdu language as tool of empowerment for minorities especially coming from weaker socio-economic backgrounds'[112]), but in the early 21st century an increasing percentage of Indian Muslims began switching to Hindi due to socio-economic factors, such as Urdu being abandoned as the language of instruction in much of India,[113][112] and having limited employment opportunities compared to Hindi, English and regional languages.[111]

The number of Urdu speakers in India fell 1.5% between 2001 and 2011 (then 5.08 million Urdu speakers), especially in the most Urdu-speaking states of Uttar Pradesh (c. 8% to 5%) and Bihar (c. 11.5% to 8.5%), even though the number of Muslims in these two states grew in the same period.[113] Although Urdu is still very prominent in early 21st-century Indian pop culture, ranging from Bollywood[110] to social media, knowledge of the Urdu script and the publication of books in Urdu have steadily declined, while policies of the Indian government do not actively support the preservation of Urdu in professional and official spaces.[112]

In part because the Pakistani government proclaimed Urdu the national language at Partition, the Indian state and some religious nationalists began to regard Urdu as a 'foreign' language, to be viewed with suspicion.[109] Urdu advocates in India disagree whether it should be allowed to write Urdu in the Devanagari and Latin script (Roman Urdu) to allow its survival,[111][116] or whether this will only hasten its demise and that the language can only be preserved if expressed in the Perso-Arabic script.[112]

For Pakistan, Willoughby & Aftab (2020) argued that Urdu originally had the image of a refined elite language of the Enlightenment, progress and emancipation, which contributed to the success of the independence movement.[114] But after the 1947 Partition, when it was chosen as the national language of Pakistan to unite all inhabitants with one linguistic identity, it faced serious competition primarily from Bengali (spoken by 56% of the total population, mostly in East Pakistan until that attained independence in 1971 as Bangladesh), and after 1971 from English. Both pro-independence elites that formed the leadership of the Muslim League in Pakistan and the Hindu-dominated Congress Party in India had been educated in English during the British colonial period, and continued to operate in English and send their children to English-medium schools as they continued dominate both countries' post-Partition politics.[114] Although the Anglicised elite in Pakistan has made attempts at Urduisation of education with varying degrees of success, no successful attempts were ever made to Urduise politics, the legal system, the army, or the economy, all of which remained solidly Anglophone.[114] Even the regime of general Zia-ul-Haq (1977–1988), who came from a middle-class Urdu-speaking family and initially fervently supported a rapid and complete Urduisation of Pakistani society (earning him the honorary title of the 'Patron of Urdu' in 1981), failed to make significant achievements, and by 1987 had abandoned most of his efforts in favour of pro-English policies.[114] Since the 1960s, the Urdu lobby and eventually the Urdu language itself in Pakistan has been associated with religious Islamism and political national conservatism (and eventually the lower and lower-middle classes, alongside regional languages such as Punjabi, Sindhi, and Balochi), while English has been associated with the internationally oriented secular and progressive left (and eventually the upper and upper-middle classes).[114] Despite these governmental attempts at Urduisation, the position and prestige of English only grew stronger in the meantime.[114]

Demographics and geographic distribution

There are over 100 million native speakers of Urdu in India and Pakistan together: there were 50.8 million Urdu speakers in India (4.34% of the total population) as per the 2011 census;[117][118] approximately 16 million in Pakistan in 2006.[119] There are several hundred thousand in the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, United States, and Bangladesh.[120] However, Hindustani, of which Urdu is one variety, is spoken much more widely, forming the third most commonly spoken language in the world, after Mandarin and English.[121] The syntax (grammar), morphology, and the core vocabulary of Urdu and Hindi are essentially identical – thus linguists usually count them as one single language, while some contend that they are considered as two different languages for socio-political reasons.[122]

Owing to interaction with other languages, Urdu has become localized wherever it is spoken, including in Pakistan. Urdu in Pakistan has undergone changes and has incorporated and borrowed many words from regional languages, thus allowing speakers of the language in Pakistan to distinguish themselves more easily and giving the language a decidedly Pakistani flavour. Similarly, the Urdu spoken in India can also be distinguished into many dialects such as the Standard Urdu of Lucknow and Delhi, as well as the Dakhni (Deccan) of South India.[25][61] Because of Urdu's similarity to Hindi, speakers of the two languages can easily understand one another if both sides refrain from using literary vocabulary.[20]

Pakistan

Although Urdu is widely spoken and understood throughout all of Pakistan,[123] only 7% of Pakistan's population spoke Urdu as their native language around 1992.[124] Most of the nearly three million Afghan refugees of different ethnic origins (such as Pashtun, Tajik, Uzbek, Hazarvi, and Turkmen) who stayed in Pakistan for over twenty-five years have also become fluent in Urdu.[96] Muhajirs since 1947 have historically formed the majority population in the city of Karachi, however.[125] Many newspapers are published in Urdu in Pakistan, including the Daily Jang, Nawa-i-Waqt, and Millat.

No region in Pakistan uses Urdu as its mother tongue, though it is spoken as the first language of Muslim migrants (known as Muhajirs) in Pakistan who left India after independence in 1947.[126] Other communities, most notably the Punjabi elite of Pakistan, have adopted Urdu as a mother tongue and identify with both an Urdu speaker as well as Punjabi identity.[127][128] Urdu was chosen as a symbol of unity for the new state of Pakistan in 1947, because it had already served as a lingua franca among Muslims in north and northwest British India.[90] It is written, spoken and used in all provinces/territories of Pakistan, and together with English as the main languages of instruction,[129] although the people from differing provinces may have different native languages.[130]

Urdu is taught as a compulsory subject up to higher secondary school in both English and Urdu medium school systems, which has produced millions of second-language Urdu speakers among people whose native language is one of the other languages of Pakistan – which in turn has led to the absorption of vocabulary from various regional Pakistani languages,[131] while some Urdu vocabularies has also been assimilated by Pakistan's regional languages.[132] Some who are from a non-Urdu background now can read and write only Urdu. With such a large number of people(s) speaking Urdu, the language has acquired a peculiar Pakistani flavour further distinguishing it from the Urdu spoken by native speakers, resulting in more diversity within the language.[133]

India

In India, Urdu is spoken in places where there are large Muslim minorities or cities that were bases for Muslim empires in the past. These include parts of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra (Marathwada and Konkanis), Karnataka and cities such as Hyderabad, Lucknow, Delhi, Malerkotla, Bareilly, Meerut, Saharanpur, Muzaffarnagar, Roorkee, Deoband, Moradabad, Azamgarh, Bijnor, Najibabad, Rampur, Aligarh, Allahabad, Gorakhpur, Agra, Firozabad, Kanpur, Badaun, Bhopal, Hyderabad, Aurangabad,[17] Bangalore, Kolkata, Mysore, Patna, Darbhanga,Gaya,Madhubani,Samastipur,Siwan,Saharsa,Supaul,Muzaffarpur,Nalanda,Munger,Bhagalpur,Araria,Gulbarga, Parbhani, Nanded, Malegaon, Bidar, Ajmer, and Ahmedabad.[11] In a very significant amount among the nearly 800 districts of India, there is a small Urdu-speaking minority at least. In Araria district, Bihar, there is a plurality of Urdu speakers and near-plurality in Hyderabad district, Telangana (43.35% Telugu speakers and 43.24% Urdu speakers).

Some Indian schools teach Urdu as a first language and have their own syllabi and exams. India's Bollywood industry frequently employs the use of Urdu – especially in songs.[134]

India has more than 3,000 Urdu publications, including 405 daily Urdu newspapers.[135][136] Newspapers such as Neshat News Urdu, Sahara Urdu, Daily Salar, Hindustan Express, Daily Pasban, Siasat Daily, The Munsif Daily and Inqilab are published and distributed in Bangalore, Malegaon, Mysore, Hyderabad, and Mumbai.[137]

Elsewhere

Outside South Asia, it is spoken by large numbers of migrant South Asian workers in the major urban centres of the Persian Gulf countries. Urdu is also spoken by large numbers of immigrants and their children in the major urban centres of the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Germany, New Zealand, Norway, and Australia.[138] Along with Arabic, Urdu is among the immigrant languages with the most speakers in Catalonia.[139]

Cultural identity

Colonial India

Religious and social atmospheres in early nineteenth century India played a significant role in the development of the Urdu register. Hindi became the distinct register spoken by those who sought to construct a Hindu identity in the face of colonial rule.[24] As Hindi separated from Hindustani to create a distinct spiritual identity, Urdu was employed to create a definitive Islamic identity for the Muslim population in India.[140] Urdu's use was not confined only to northern India – it had been used as a literary medium for Indian writers from the Bombay Presidency, Bengal, Orissa Province, and Tamil Nadu as well.[141]

As Urdu and Hindi became means of religious and social construction for Muslims and Hindus respectively, each register developed its own script. According to Islamic tradition, Arabic, the language spoken by the prophet Muhammad and uttered in the revelation of the Qur'an, holds spiritual significance and power.[142] Because Urdu was intentioned as means of unification for Muslims in Northern India and later Pakistan, it adopted a modified Perso-Arabic script.[143][24]

Pakistan

Urdu continued its role in developing a Muslim identity as the Islamic Republic of Pakistan was established with the intent to construct a homeland for Muslims of South Asia. Several languages and dialects spoken throughout the regions of Pakistan produced an imminent need for a uniting language. Urdu was chosen as a symbol of unity for the new state of Pakistan in 1947, because it had already served as a lingua franca among Muslims in north and northwest British India.[90] Urdu is also seen as a repertory for the cultural and social heritage of Pakistan.[144]

While Urdu and Islam together played important roles in developing the national identity of Pakistan, disputes in the 1950s (particularly those in East Pakistan, where Bengali was the dominant language), challenged the idea of Urdu as a national symbol and its practicality as the lingua franca. The significance of Urdu as a national symbol was downplayed by these disputes when English and Bengali were also accepted as official languages in the former East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).[145]

Official status

Pakistan

Urdu is the sole national, and one of the two official languages of Pakistan (along with English).[92] It is spoken and understood throughout the country, whereas the state-by-state languages (languages spoken throughout various regions) are the provincial languages, although only 7.57% of Pakistanis speak Urdu as their first language.[146] Its official status has meant that Urdu is understood and spoken widely throughout Pakistan as a second or third language. It is used in education, literature, office and court business,[147] although in practice, English is used instead of Urdu in the higher echelons of government.[148] Article 251(1) of the Pakistani Constitution mandates that Urdu be implemented as the sole language of government, though English continues to be the most widely used language at the higher echelons of Pakistani government.[149]

India

Urdu is also one of the officially recognised languages in India and also has the status of "additional official language" in the Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Telangana and the national capital territory Delhi.[150][151] Also as one of the five official languages of Jammu and Kashmir.[152] In the former Jammu and Kashmir state, section 145 of the Kashmir Constitution stated: "The official language of the State shall be Urdu but the English language shall unless the Legislature by law otherwise provides, continue to be used for all the official purposes of the State for which it was being used immediately before the commencement of the Constitution."[153]

India established the governmental Bureau for the Promotion of Urdu in 1969, although the Central Hindi Directorate was established earlier in 1960, and the promotion of Hindi is better funded and more advanced,[154] while the status of Urdu has been undermined by the promotion of Hindi.[155] Private Indian organisations such as the Anjuman-e-Tariqqi Urdu, Deeni Talimi Council and Urdu Mushafiz Dasta promote the use and preservation of Urdu, with the Anjuman successfully launching a campaign that reintroduced Urdu as an official language of Bihar in the 1970s.[154]

Dialects

Urdu has a few recognised dialects, including Dakhni, Dhakaiya, Rekhta, and Modern Vernacular Urdu (based on the Khariboli dialect of the Delhi region). Dakhni (also known as Dakani, Deccani, Desia, Mirgan) is spoken in Deccan region of southern India. It is distinct by its mixture of vocabulary from Marathi and Konkani, as well as some vocabulary from Arabic, Persian and Chagatai that are not found in the standard dialect of Urdu. Dakhini is widely spoken in all parts of Maharashtra, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka. Urdu is read and written as in other parts of India. A number of daily newspapers and several monthly magazines in Urdu are published in these states.

Dhakaiya Urdu is a dialect native to the city of Old Dhaka in Bangladesh, dating back to the Mughal era. However, its popularity, even amongst native speakers, has been gradually declining since the Bengali Language Movement in the 20th century. It is not officially recognised by the Government of Bangladesh. The Urdu spoken by Stranded Pakistanis in Bangladesh is different from this dialect.

Code switching

Many bilingual or multi-lingual Urdu speakers, being familiar with both Urdu and English, display code-switching (referred to as "Urdish") in certain localities and between certain social groups. On 14 August 2015, the Government of Pakistan launched the Ilm Pakistan movement, with a uniform curriculum in Urdish. Ahsan Iqbal, Federal Minister of Pakistan, said "Now the government is working on a new curriculum to provide a new medium to the students which will be the combination of both Urdu and English and will name it Urdish."[156][157][158]

Comparison with Modern Standard Hindi

Standard Urdu is often compared with Standard Hindi.[159] Both Urdu and Hindi, which are considered standard registers of the same language, Hindustani (or Hindi-Urdu), share a core vocabulary and grammar.[160][19][20][161]

Apart from religious associations, the differences are largely restricted to the standard forms: Standard Urdu is conventionally written in the Nastaliq style of the Persian alphabet and relies heavily on Persian and Arabic as a source for technical and literary vocabulary,[162] whereas Standard Hindi is conventionally written in Devanāgarī and draws on Sanskrit.[163] However, both share a core vocabulary of native Sanskrit and Prakrit derived words and a significant amount of Arabic and Persian loanwords, with a consensus of linguists considering them to be two standardised forms of the same language[164][165] and consider the differences to be sociolinguistic;[166] a few classify them separately.[167] The two languages are often considered to be a single language (Hindustani or Hindi-Urdu) on a dialect continuum ranging from Persianised to Sanskritised vocabulary.[155] Old Urdu dictionaries also contain most of the Sanskrit words now present in Hindi.[168][169]

Mutual intelligibility decreases in literary and specialised contexts that rely on academic or technical vocabulary. In a longer conversation, differences in formal vocabulary and pronunciation of some Urdu phonemes are noticeable, though many native Hindi speakers also pronounce these phonemes.[170] At a phonological level, speakers of both languages are frequently aware of the Perso-Arabic or Sanskrit origins of their word choice, which affects the pronunciation of those words.[171] Urdu speakers will often insert vowels to break up consonant clusters found in words of Sanskritic origin, but will pronounce them correctly in Arabic and Persian loanwords.[172] As a result of religious nationalism since the partition of British India and continued communal tensions, native speakers of both Hindi and Urdu frequently assert that they are distinct languages.

The grammar of Hindi and Urdu is shared,[160][173] though formal Urdu makes more use of the Persian "-e-" izafat grammatical construct (as in Hammam-e-Qadimi, or Nishan-e-Haider) than does Hindi.

Urdu speakers by country

The following table shows the number of Urdu speakers in some countries.

| Country | Population | Urdu as a native language speakers | % | Native speakers or very good speakers as a second language | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,296,834,042[174] | 50,772,631[90] | 3.9 | 12,151,715[90] | 0.9 | |

| 207,862,518[175] | 30,000,000[1] | 14.4 | 105,000,000[176] | 50.5 | |

| 34,940,837[171] | – | - | 1,048,225[171] | 3.0 | |

| 33,091,113[177] | 757,000 | 2.3 | – | - | |

| 29,717,587[178] | 691,546[179] | 2.3 | – | - | |

| 65,105,246[180] | 400,000[181] | 0.6 | – | - | |

| 329,256,465[182] | 397,502[183] | 0.1 | – | - | |

| 9,890,400 | 300,000 | 3.0 | 1,500,000 | 15.1 | |

| 159,453,001[184] | 250,000[185] | 0.1 | – | - | |

| 35,881,659[186] | 243,090[187] | 0.6 | – | - | |

| 2,363,569[188] | 173,000 | 7.3 | – | - | |

| 4,613,241[189] | 95,000 | 2.0 | – | - | |

| 83,024,745[190] | 88,000 | 0.1 | – | - | |

| 1,442,659[191] | 74,000 | 5.1 | – | - | |

| 5,372,191[192] | 34,000 | 0.6 | – | - | |

| 81,257,239[193] | 24,000 | 0.03 | – | - | |

| 80,457,737[194] | 23,000 | 0.03 | – | - |

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m م | n ن | ŋ ن٘ | ||||||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | p پ | t ت | ʈ ٹ | tʃ چ | k ک | (q) ق | ||

| voiceless aspirated | pʰ پھ | tʰ تھ | ʈʰ ٹھ | tʃʰ چھ | kʰ کھ | ||||

| voiced | b ب | d د | ɖ ڈ | dʒ ج | ɡ گ | ||||

| voiced aspirated | bʰ بھ | dʰ دھ | ɖʰ ڈھ | dʒʰ جھ | gʰ گھ | ||||

| Flap/Trill | plain | r ر | ɽ ڑ | ||||||

| voiced aspirated | ɽʱ ڑھ | ||||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f ف | s س | ʃ ش | x خ | ɦ ہ | |||

| voiced | ʋ و | z ز | (ʒ) ژ | (ɣ) غ | |||||

| Approximant | l ل | j ی | |||||||

- Notes

- Marginal and non-universal phonemes are in parentheses.

- /ɣ/ is post-velar.[196]

Vocabulary

Syed Ahmed Dehlavi, a 19th-century lexicographer who compiled the Farhang-e-Asifiya[199] Urdu dictionary, estimated that 75% of Urdu words have their etymological roots in Sanskrit and Prakrit,[200][201][202] and approximately 99% of Urdu verbs have their roots in Sanskrit and Prakrit.[203][204] Urdu has borrowed words from Persian and to a lesser extent, Arabic through Persian,[205] to the extent of about 25%[200][201][202][206] to 30% of Urdu's vocabulary.[207] A table illustrated by the linguist Afroz Taj of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill likewise illustrates the amount of Persian loanwords to native Sanskrit-derived words in literary Urdu as comprising a 1:3 ratio.[202]

The "trend towards Persianisation" started in the 18th century by the Delhi school of Urdu poets, though other writers, such as Meeraji, wrote in a Sanskritised form of the language.[209] There has been a move towards hyper Persianisation in Pakistan since 1947, which has been adopted by much of the country's writers;[210] as such, some Urdu texts can be composed of 70% Perso-Arabic loanwords just as some Persian texts can have 70% Arabic vocabulary.[211] Some Pakistani Urdu speakers have incorporated Hindi vocabulary into their speech as a result of exposure to Indian entertainment.[212][213] In India, Urdu has not diverged from Hindi as much as it has in Pakistan.[214]

Most borrowed words in Urdu are nouns and adjectives.[215] Many of the words of Arabic origin have been adopted through Persian,[200] and have different pronunciations and nuances of meaning and usage than they do in Arabic. There are also a smaller number of borrowings from Portuguese. Some examples for Portuguese words borrowed into Urdu are chabi ("chave": key), girja ("igreja": church), kamra ("cámara": room), qamīz ("camisa": shirt).[216]

Although the word Urdu is derived from the Turkic word ordu (army) or orda, from which English horde is also derived,[217] Turkic borrowings in Urdu are minimal[218] and Urdu is also not genetically related to the Turkic languages. Urdu words originating from Chagatai and Arabic were borrowed through Persian and hence are Persianised versions of the original words. For instance, the Arabic ta' marbuta ( ة ) changes to he ( ه ) or te ( ت ).[219][note 2] Nevertheless, contrary to popular belief, Urdu did not borrow from the Turkish language, but from Chagatai, a Turkic language from Central Asia. Urdu and Turkish both borrowed from Arabic and Persian, hence the similarity in pronunciation of many Urdu and Turkish words.[220]

Formality

Urdu in its less formalised register has been referred to as a rek̤h̤tah (ریختہ, [reːxtaː]), meaning "rough mixture". The more formal register of Urdu is sometimes referred to as zabān-i Urdū-yi muʿallá (زبانِ اُردُوئے معلّٰى [zəbaːn eː ʊrdu eː moəllaː]), the "Language of the Exalted Camp", referring to the Imperial army[221] or in approximate local translation Lashkari Zabān (لشکری زبان [ləʃkəɾi: zɑ:bɑ:n])[222] or simply just Lashkari.[223] The etymology of the word used in Urdu, for the most part, decides how polite or refined one's speech is. For example, Urdu speakers would distinguish between پانی pānī and آب āb, both meaning "water": the former is used colloquially and has older Sanskrit origins, whereas the latter is used formally and poetically, being of Persian origin.

If a word is of Persian or Arabic origin, the level of speech is considered to be more formal and grander. Similarly, if Persian or Arabic grammar constructs, such as the izafat, are used in Urdu, the level of speech is also considered more formal and grander. If a word is inherited from Sanskrit, the level of speech is considered more colloquial and personal.[224]

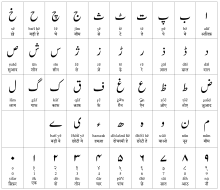

Writing system

Urdu is written right-to left in an extension of the Persian alphabet, which is itself an extension of the Arabic alphabet. Urdu is associated with the Nastaʿlīq style of Persian calligraphy, whereas Arabic is generally written in the Naskh or Ruq'ah styles. Nasta’liq is notoriously difficult to typeset, so Urdu newspapers were hand-written by masters of calligraphy, known as kātib or khush-nawīs, until the late 1980s. One handwritten Urdu newspaper, The Musalman, is still published daily in Chennai.[225]

A highly Persianised and technical form of Urdu was the lingua franca of the law courts of the British administration in Bengal and the North-West Provinces & Oudh. Until the late 19th century, all proceedings and court transactions in this register of Urdu were written officially in the Persian script. In 1880, Sir Ashley Eden, the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal in colonial India abolished the use of the Persian alphabet in the law courts of Bengal and ordered the exclusive use of Kaithi, a popular script used for both Urdu and Hindi; in the Bihar Province, the court language was Urdu written in the Kaithi script.[226][227][228][229] Kaithi's association with Urdu and Hindi was ultimately eliminated by the political contest between these languages and their scripts, in which the Persian script was definitively linked to Urdu.[230]

More recently in India, Urdu speakers have adopted Devanagari for publishing Urdu periodicals and have innovated new strategies to mark Urdu in Devanagari as distinct from Hindi in Devanagari. Such publishers have introduced new orthographic features into Devanagari for the purpose of representing the Perso-Arabic etymology of Urdu words. One example is the use of अ (Devanagari a) with vowel signs to mimic contexts of ع (‘ain), in violation of Hindi orthographic rules. For Urdu publishers, the use of Devanagari gives them a greater audience, whereas the orthographic changes help them preserve a distinct identity of Urdu.[231]

Some poets from Bengal, namely Qazi Nazrul Islam, have historically used the Bengali script to write Urdu poetry like Prem Nagar Ka Thikana Karle and Mera Beti Ki Khela, as well as bilingual Bengali-Urdu poems like Alga Koro Go Khõpar Bãdhon, Juboker Chholona and Mera Dil Betab Kiya.[232][233][234] Dhakaiya Urdu is a colloquial non-standard dialect of Urdu which was typically not written. However, organisations seeking to preserve the dialect have begun transcribing the dialect in the Bengali script.[note 3][235][236]

|

| Constitutionally recognised languages of India |

|---|

| Category |

| Official Languages of the Indian Republic |

| Related |

|

Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India Official Languages Commission Languages by number of native speakers |

|

See also

- List of Urdu-language poets

- List of Urdu-language writers

- Urdu-speaking people

- Urdu movement

- Persian and Urdu

- States of India by Urdu speakers

- Urdu in the United Kingdom

- Uddin and Begum Hindustani Romanisation

- Urdu poetry

- Urdu Digest

- Urdu in Aurangabad

- Urdu Informatics

- Urdu Wikipedia

- Urdu keyboard

- Glossary of the British Raj

- Persian language in the Indian subcontinent

Notes

- Urdu has some form of official status in the Indian states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Telangana, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal, as well as the national capital territory of Delhi and the Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir.[14]

- An example can be seen in the word "need" in Urdu. Urdu uses the Persian version ضرورت rather than the original Arabic ضرورة. See: John T. Platts "A dictionary of Urdu, classical Hindi, and English" (1884) Page 749. Urdu and Hindi use Persian pronunciation in their loanwords, rather than that of Arabic– for instance rather than pronouncing ض as the emphatic consonant "ḍ", the original sound in Arabic, Urdu uses the Persian pronunciation "z". See: John T. Platts "A dictionary of Urdu, classical Hindi, and English" (1884) Page 748

- Organisations like Dhakaiya Sobbasi Jaban and Dhakaiya Movement, among others, consistently write Dhakaiya Urdu using the Bengali script.

References

- Carl Skutsch (7 November 2013). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. Taylor & Francis. pp. 2234–. ISBN 978-1-135-19395-9.

- Hindustani (2005). Keith Brown (ed.). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2 ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 0-08-044299-4.

- "Indo-Pakistani Sign Language", Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics

- Gaurav Takkar. "Short Term Programmes". punarbhava.in. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Official languages specified in the Constitution of India". Jagran Prakashan. 29 March 2018.

- "Urdu second official language in Andhra Pradesh". Deccan Chronicles. 24 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- "Bill recognising Urdu as second official language passed". The Hindu. 23 March 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- "Urdu is Telangana's second official language". The Indian Express. 16 November 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- "Urdu is second official language in Telangana as state passes Bill". The News Minute. 17 November 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- "Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 - Chapter 1: Founding Provisions". www.gov.za. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- "Urdu"Archived 19 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Urdu language, Encyclopaedia Britannica, 5 December 2019, retrieved 17 October 2020,

member of the Indo-Aryan group within the Indo-European family of languages. Urdu is spoken as a first language by nearly 70 million people and as a second language by more than 100 million people, predominantly in Pakistan and India. It is the official state language of Pakistan and is also officially recognized, or “scheduled,” in the constitution of India.

- Urdu (n), Oxford English Dictionary, June 2020, retrieved 11 September 2020,

An Indo-Aryan language of northern South Asia (now esp. Pakistan), closely related to Hindi but written in a modified form of the Arabic script and having many loanwords from Persian and Arabic.

- Muzaffar, Sharmin; Behera, Pitambar (2014). "Error analysis of the Urdu verb markers: a comparative study on Google and Bing machine translation platforms". Aligarh Journal of Linguistics. 4 (1–2): 1.

Modern Standard Urdu, a register of the Hindustani language, is the national language, lingua-franca and is one of the two official languages along with English in Pakistan and is spoken in all over the world. It is also one of the 22 scheduled languages and officially recognized languages in the Constitution of India and has been conferred the status of the official language in many Indian states of Bihar, Telangana, Jammu, and Kashmir, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, and New Delhi. Urdu is one of the members of the new or modern Indo-Aryan language group within the Indo-European family of languages.

- Gazzola, Michele; Wickström, Bengt-Arne (2016). The Economics of Language Policy. MIT Press. pp. 469–. ISBN 978-0-262-03470-8. Quote: "The Eighth Schedule recognizes India's national languages as including the major regional languages as well as others, such as Sanskrit and Urdu, which contribute to India's cultural heritage. ... The original list of fourteen languages in the Eighth Schedule at the time of the adoption of the Constitution in 1949 has now grown to twenty-two."

- Groff, Cynthia (2017). The Ecology of Language in Multilingual India: Voices of Women and Educators in the Himalayan Foothills. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-1-137-51961-0. Quote: "As Mahapatra says: “It is generally believed that the significance for the Eighth Schedule lies in providing a list of languages from which Hindi is directed to draw the appropriate forms, style and expressions for its enrichment” ... Being recognized in the Constitution, however, has had significant relevance for a language's status and functions.

- "National Languages Policy Recommendation Commission" (PDF). MOE Nepal. 1994. p. Appendix one. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- Gibson, Mary (13 May 2011). Indian Angles: English Verse in Colonial India from Jones to Tagore. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0821443583.

Bayly's description of Hindustani (roughly Hindi/Urdu) is helpful here; he uses the term Urdu to represent "the more refined and Persianised form of the common north Indian language Hindustani" (Empire and Information, 193); Bayly more or less follows the late eighteenth-century scholar Sirajuddin Ali Arzu, who proposed a typology of language that ran from "pure Sanskrit, through popular and regional variations of Hindustani to Urdu, which incorporated many loan words from Persian and Arabic. His emphasis on the unity of languages reflected the view of the Sanskrit grammarians and also affirmed the linguistic unity of the north Indian ecumene. What emerged was a kind of register of language types that were appropriate to different conditions. ...But the abiding impression is of linguistic plurality running through the whole society and an easier adaptation to circumstances in both spoken and written speech" (193). The more Persianized the language, the more likely it was to be written in Arabic script; the more Sanskritized the language; the more likely it was to be written in Devanagari.

- Basu, Manisha (2017). The Rhetoric of Hindutva. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107149878.

Urdu, like Hindi, was a standardized register of the Hindustani language deriving from the Dehlavi dialect and emerged in the eighteenth century under the rule of the late Mughals.

- Gube, Jan; Gao, Fang (2019). Education, Ethnicity and Equity in the Multilingual Asian Context. Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-981-13-3125-1.

The national language of India and Pakistan 'Standard Urdu' is mutually intelligible with 'Standard Hindi' because both languages share the same Indic base and are all but indistinguishable in phonology.

- Clyne, Michael (24 May 2012). Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations. Walter de Gruyter. p. 385. ISBN 978-3-11-088814-0.

With the consolidation of the different linguistic bases of Khari Boli there were three distinct varieties of Hindi-Urdu: the High Hindi with predominant Sanskrit vocabulary, the High-Urdu with predominant Perso-Arabic vocabulary and casual or colloquial Hindustani which was commonly spoken among both the Hindus and Muslims in the provinces of north India. The last phase of the emergence of Hindi and Urdu as pluricentric national varieties extends from the late 1920s till the partition of India in 1947.

- Kiss, Tibor; Alexiadou, Artemis (10 March 2015). Syntax - Theory and Analysis. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 1479. ISBN 978-3-11-036368-5.

- Metcalf, Barbara D. (2014). Islamic Revival in British India: Deoband, 1860-1900. Princeton University Press. pp. 207–. ISBN 978-1-4008-5610-7.

The basis of that shift was the decision made by the government in 1837 to replace Persian as court language by the various vernaculars of the country. Urdu was identified as the regional vernacular in Bihar, Oudh, the North-Western Provinces, and Punjab, and hence was made the language of government across upper India.

- Ahmad, Rizwan (1 July 2008). "Scripting a new identity: The battle for Devanagari in nineteenth-century India". Journal of Pragmatics. 40 (7): 1163–1183. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2007.06.005.

- Schmidt, Ruth Laila (8 December 2005). Urdu: An Essential Grammar. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-71319-6.

Historically, Urdu developed from the sub-regional language of the Delhi area, which became a literary language in the eighteenth century. Two quite similar standard forms of the language developed in Delhi, and in Lucknow in modern Uttar Pradesh. Since 1947, a third form, Karachi standard Urdu, has evolved.

- Mahapatra, B. P. (1989). Constitutional languages. Presses Université Laval. p. 553. ISBN 978-2-7637-7186-1.

Modern Urdu is a fairly homogenous language. An older southern form, Deccani Urdu, is now obsolete. Two varieties however, must be mentioned viz. the Urdu of Delhi, and the Urdu of Lucknow. Both are almost identical, differing only in some minor points. Both of these varieties are considered 'Standard Urdu' with some minor divergences.

- Dwyer, Rachel (27 September 2006). Filming the Gods: Religion and Indian Cinema. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-38070-1.

- "What are the top 200 most spoken languages?". Ethnologue. 3 March 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- Faruqi, Shamsur Rahman (2003), Sheldon Pollock (ed.), A Long History of Urdu Literary Culture Part 1, Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions From South Asia, University of California Press, p. 806, ISBN 978-0-520-22821-4

- Rahman, Tariq (2001). From Hindi to Urdu: A Social and Political History (PDF). Oxford University Press. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-0-19-906313-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- "A Historical Perspective of Urdu | National Council for Promotion of Urdu Language". web.archive.org. 15 October 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- Dictionary, Rekhta (5 April 2022). "Meaning of Urdu". Rekhta dictionary. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- Clyne, Michael G. (1992). Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations. Walter de Gruyter. p. 383. ISBN 9783110128550.

- "Meaning of urdu-e-mualla in English". Rekhta Dictionary. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- Bhat, M. Ashraf (2017). The Changing Language Roles and Linguistic Identities of the Kashmiri Speech Community. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-4438-6260-8.

Although it has borrowed a large number of lexical items from Persian and some from Turkish, it is a derivative of Hindvi (also called 'early Urdu'), the parent of both modern Hindi and Urdu. It originated as a new, common language of Delhi, which has been called Hindavi or Dahlavi by Amir Khusrau. After the advent of the Mughals on the stage of Indian history, the Hindavi language enjoyed greater space and acceptance. Persian words and phrases came into vogue. The Hindavi of that period was known as Rekhta, or Hindustani, and only later as Urdu. Perfect amity and tolerance between Hindus and Muslims tended to foster Rekhta or Urdu, which represented the principle of unity in diversity, thus marking a feature of Indian life at its best. The ordinary spoken version ('bazaar Urdu') was almost identical to the popularly spoken version of Hindi. Most prominent scholars in India hold the view that Urdu is neither a Muslim nor a Hindu language; it is an outcome of a multicultural and multi-religious encounter.

- Dua, Hans R. (1992). Hindi-Urdu is a pluricentric language. In M. G. Clyne (Ed.), Pluricentric languages: Differing norms in different nations. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-012855-1.

- Kachru, Yamuna (2008), Braj Kachru; Yamuna Kachru; S. N. Sridhar (eds.), Hindi-Urdu-Hindustani, Language in South Asia, Cambridge University Press, p. 82, ISBN 978-0-521-78653-9, archived from the original on 24 January 2020

- Qalamdaar, Azad (27 December 2010). "Hamari History". Hamari Boli Foundation. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010.

Historically, Hindustani developed in the post-12th century period under the impact of the incoming Afghans and Turks as a linguistic modus vivendi from the sub-regional apabhramshas of north-western India. Its first major folk poet was the great Persian master, Amir Khusrau (1253–1325), who is known to have composed dohas (couplets) and riddles in the newly-formed speech, then called 'Hindavi'. Through the medieval time, this mixed speech was variously called by various speech sub-groups as 'Hindavi', 'Zaban-e-Hind', 'Hindi', 'Zaban-e-Dehli', 'Rekhta', 'Gujarii. 'Dakkhani', 'Zaban-e-Urdu-e-Mualla', 'Zaban-e-Urdu', or just 'Urdu'. By the late 11th century, the name 'Hindustani' was in vogue and had become the lingua franca for most of northern India. A sub-dialect called Khari Boli was spoken in and around the Delhi region at the start of the 13th century when the Delhi Sultanate was established. Khari Boli gradually became the prestige dialect of Hindustani (Hindi-Urdu) and became the basis of modern Standard Hindi & Urdu.

- Schmidt, Ruth Laila. "1 Brief history and geography of Urdu 1.1 History and sociocultural position." The Indo-Aryan Languages 3 (2007): 286.

- Malik, Shahbaz, Shareef Kunjahi, Mir Tanha Yousafi, Sanawar Chadhar, Alam Lohar, Abid Tamimi, Anwar Masood et al. "Census History of Punjabi Speakers in Pakistan."

- Mody, Sujata Sudhakar (2008). Literature, Language, and Nation Formation: The Story of a Modern Hindi Journal 1900-1920. University of California, Berkeley. p. 7.

...Hindustani, Rekhta, and Urdu as later names of the old Hindi (a.k.a. Hindavi).

- English-Urdu Learner's Dictionary. Multi Linguis. 6 March 2021. ISBN 978-1-005-94089-8.

** History (Simplified) ** Proto-Indo European > Proto-Indo-Iranian > Proto-Indo-Aryan > Vedic Sanskrit > Classical Sanskrit > Sauraseni Prakrit > Sauraseni Apabhramsa > Old Hindi > Hindustani > Urdu

- Kesavan, B. S. (1997). History Of Printing And Publishing in India. National Book Trust, India. p. 31. ISBN 978-81-237-2120-0.

It might be useful to recall here that Old Hindi or Hindavi, which was a naturally Persian- mixed language in the largest measure, has played this role before, as we have seen, for five or six centuries.

- Sisir Kumar Das (2005). History of Indian Literature. Sahitya Akademi. p. 142. ISBN 978-81-7201-006-5.

The most important trend in the history of Hindi-Urdu is the process of Persianization on the one hand and that of Sanskritization on the other. Amrit Rai offers evidence to show that although the employment of Perso-Arabic script for the language which was akin to Hindi/Hindavi or old Hindi was the first step towards the establishment of the separate identity of Urdu, it was called Hindi for a long time. "The final and complete change-over to the new name took place after the content of the language had undergone a drastic change." He further observes: "In the light of the literature that has come down to us, for about six hundred years, the development of Hindi/Hindavi seems largely to substantiate the view of the basic unity of the two languages. Then, sometime in the first quarter of the eighteenth century, the cleavage seems to have begun." Rai quotes from Sadiq, who points out how it became a "systematic policy of poets and scholars" of the eighteenth century to weed out, what they called and thought, "vulgar words." This weeding out meant "the elimination, along with some rough and unmusical plebian words, of a large number of Hindi words for the reason that to the people brought up in Persian traditions they appeared unfamiliar and vulgar." Sadiq concludes: hence the paradox that this crusade against Persian tyranny, instead of bringing Urdu close to the indigenous element, meant in reality a wider gulf between it and the popular speech. But what differentiated Urdu still more from the local dialects was a process of ceaseless importation from Persian. It may seem strange that Urdu writers in rebellion against Persian should decide to draw heavily on Persian vocabulary, idioms, forms, and sentiments. . . . Around 1875 in his word Urdu Sarf O Nahr, however, he presented a balanced view pointing out that attempts of the Maulavis to Persianize and of the Pandits to Sanskritize the language were not only an error but against the natural laws of linguistic growth. The common man, he pointed out, used both Persian and Sanskrit words without any qualms;

- Taj, Afroz (1997). "About Hindi-Urdu". The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- "Two Languages or One?". hindiurduflagship.org. Archived from the original on 11 March 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

Hindi and Urdu developed from the "khari boli" dialect spoken in the Delhi region of northern India.

- Farooqi, M. (2012). Urdu Literary Culture: Vernacular Modernity in the Writing of Muhammad Hasan Askari. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-02692-7.

Historically speaking, Urdu grew out of interaction between Hindus and Muslims. He noted that Urdu is not the language of Muslims alone, although Muslims may have played a larger role in making it a literary language. Hindu poets and writers could and did bring specifically Hindu cultural elements into Urdu and these were accepted.

- King, Christopher Rolland (1999). One Language, Two Scripts: The Hindi Movement in Nineteenth Century North India. Oxford University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-19-565112-6.

Educated Muslims, for the most part supporters of Urdu, rejected the Hindu linguistic heritage and emphasized the joint Hindu-Muslim origins of Urdu.

- Taylor, Insup; Olson, David R. (1995). Scripts and Literacy: Reading and Learning to Read Alphabets, Syllabaries, and Characters. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-7923-2912-1.

Urdu emerged as the language of contact between Hindu inhabitants and Muslim invaders to India in the 11th century.

- Dhulipala, Venkat (2000). The Politics of Secularism: Medieval Indian Historiography and the Sufis. University of Wisconsin–Madison. p. 27.

Persian became the court language, and many Persian words crept into popular usage. The composite culture of northern India, known as the Ganga Jamuni tehzeeb was a product of the interaction between Hindu society and Islam.

- Indian Journal of Social Work, Volume 4. Tata Institute of Social Sciences. 1943. p. 264.

... more words of Sanskrit origin but 75% of the vocabulary is common. It is also admitted that while this language is known as Hindustani, ... Muslims call it Urdu and the Hindus call it Hindi. ... Urdu is a national language that evolved through years of Hindu and Muslim cultural contact and, as stated by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, is essentially an Indian language and has no place outside.

- "Women of the Indian Sub-Continent: Makings of a Culture - Rekhta Foundation". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

The "Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb" is one such instance of the composite culture that marks various regions of the country. Prevalent in the North, particularly in the central plains, it is born of the union between the Hindu and Muslim cultures. Most of the temples were lined along the Ganges and the Khanqah (Sufi school of thought) were situated along the Yamuna river (also called Jamuna). Thus, it came to be known as the Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb, with the word "tehzeeb" meaning culture. More than communal harmony, its most beautiful by-product was "Hindustani" which later gave us the Hindi and Urdu languages.

- Zahur-ud-Din (1985). Development of Urdu Language and Literature in the Jammu Region. Gulshan Publishers. p. 13.

The beginning of the language, now known as Urdu, should therefore, be placed in this period of the earlier Hindu Muslim contact in the Sindh and Punjab areas that took place in early quarter of the 8th century A.D.

- Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

The primary sources of non-IA loans into MSH are Arabic, Persian, Portuguese, Turkic and English. Conversational registers of Hindi/Urdu (not to mentioned formal registers of Urdu) employ large numbers of Persian and Arabic loanwords, although in Sanskritised registers many of these words are replaced by tatsama forms from Sanskrit. The Persian and Arabic lexical elements in Hindi result from the effects of centuries of Islamic administrative rule over much of north India in the centuries before the establishment of British rule in India. Although it is conventional to differentiate among Persian and Arabic loan elements into Hindi/Urdu, in practice it is often difficult to separate these strands from one another. The Arabic (and also Turkic) lexemes borrowed into Hindi frequently were mediated through Persian, as a result of which a thorough intertwining of Persian and Arabic elements took place, as manifest by such phenomena as hybrid compounds and compound words. Moreover, although the dominant trajectory of lexical borrowing was from Arabic into Persian, and thence into Hindi/Urdu, examples can be found of words that in origin are actually Persian loanwords into both Arabic and Hindi/Urdu.

- Strnad, Jaroslav (2013). Morphology and Syntax of Old Hindī: Edition and Analysis of One Hundred Kabīr vānī Poems from Rājasthān. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-25489-3.

Quite different group of nouns occurring with the ending -a in the dir. plural consists of words of Arabic or Persian origin borrowed by the Old Hindi with their Persian plural endings.

- "Amīr Khosrow - Indian poet".

- Jaswant Lal Mehta (1980). Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India. Vol. 1. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 10. ISBN 9788120706170.

- Bakshi, Shiri Ram; Mittra, Sangh (2002). Hazart Nizam-Ud-Din Auliya and Hazrat Khwaja Muinuddin Chisti. Criterion. ISBN 9788179380222.

- "Urdu language". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Culture and Circulation: Literature in Motion in Early Modern India. Brill. 2014. ISBN 9789004264489.

- Khan, Abdul Rashid (2001). The All India Muslim Educational Conference: Its Contribution to the Cultural Development of Indian Muslims, 1886-1947. Oxford University Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-19-579375-8.

After the conquest of the Deccan, Urdu received the liberal patronage of the courts of Golconda and Bijapur. Consequently, Urdu borrowed words from the local language of Telugu and Marathi as well as from Sanskrit.

- Luniya, Bhanwarlal Nathuram (1978). Life and Culture in Medieval India. Kamal Prakashan. p. 311.

Under the liberal patronage of the courts of Golconda and Bijapur, Urdu borrowed words from the local languages like Telugu and Marathi as well as from Sanskrit, but its themes were moulded on Persian models.

- Kesavan, Bellary Shamanna (1985). History of Printing and Publishing in India: Origins of printing and publishing in the Hindi heartland. National Book Trust. p. 7. ISBN 978-81-237-2120-0.

The Mohammedans of the Deccan thus called their Hindustani tongue Dakhani (Dakhini), Gujari or Bhaka (Bhakha) which was a symbol of their belonging to Muslim conquering and ruling group in the Deccan and South India where overwhelming number of Hindus spoke Marathi, Kannada, Telugu and Tamil.

- Rauf Parekh (25 August 2014). "Literary Notes: Common misconceptions about Urdu". dawn.com. Archived from the original on 25 January 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

Urdu did not get its present name till late 18th Century and before that had had a number of different names – including Hindi, Hindvi, Hindustani, Dehlvi, Lahori, Dakkani, and even Moors – though it was born much earlier.

- Malik, Muhammad Kamran, and Syed Mansoor Sarwar. "Named entity recognition system for postpositional languages: urdu as a case study." International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 7.10 (2016): 141-147.

- First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913–1936. Brill Academic Publishers. 1993. p. 1024. ISBN 9789004097964.

Whilst the Muhammadan rulers of India spoke Persian, which enjoyed the prestige of being their court language, the common language of the country continued to be Hindi, derived through Prakrit from Sanskrit. On this dialect of the common people was grafted the Persian language, which brought a new language, Urdu, into existence. Sir George Grierson, in the Linguistic Survey of India, assigns no distinct place to Urdu, but treats it as an offshoot of Western Hindi.

- Am.rta Rāya, Amrit Rai, Amr̥tarāya (1984). A House Divided: The Origin and Development of Hindi/Hindavi. Oxford University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-19-561643-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Alyssa Ayres (23 July 2009). Speaking Like a State: Language and Nationalism in Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 9780521519311.

- Language Problem in India. Institute of Objective Studies. 1997. p. 138.

- sir Richard Francis Burton, Luis Vaz de Camoens (1881). Camoens: his life and his Lusiads, a commentary: Volume 2. Oxford University. p. 573.

The "Moor" of Camoens, meaning simply "Moslem", was used by a past generation of Anglo-Indians, who called the Urdu or Hindustani dialect "the Moors"

- Henk W. Wagenaar, S. S. Parikh, D. F. Plukker, R. Veldhuijzen van Zanten (1993). Allied Chambers transliterated Hindi-Hindi-English dictionary. Allied Publishers. ISBN 9788186062104.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - John Ovington (1994). A Voyage to Surat in the Year 1689. Asian Educational Services. p. 147.

- Coatsworth, John (2015). Global Connections: Politics, Exchange, and Social Life in World History. United States: Cambridge Univ Pr. p. 159. ISBN 9780521761062.

- Tariq Rahman (2011). "Urdu as the Language of Education in British India" (PDF). Pakistan Journal of History and Culture. NIHCR. 32 (2): 1–42.

- Delacy, Richard; Ahmed, Shahara (2005). Hindi, Urdu & Bengali. Lonely Planet. pp. 11–12.

Hindi and Urdu are generally considered to be one spoken language with two different literary traditions. That means that Hindi and Urdu speakers who shop in the same markets (and watch the same Bollywood films) have no problems understanding each other -- they'd both say yeh kitne kaa hay for 'How much is it?' -- but the written form for Hindi will be यह कितने का है? and the Urdu one will be یہ کتنے کا ہے؟ Hindi is written from left to right in the Devanagari script, and is the official language of India, along with English. Urdu, on the other hand, is written from right to left in the Nastaliq script (a modified form of the Arabic script) and is the national language of Pakistan. It's also one of the official languages of the Indian states of Bihar and Jammu & Kashmir. Considered as one, these tongues constitute the second most spoken language in the world, sometimes called Hindustani. In their daily lives, Hindi and Urdu speakers communicate in their 'different' languages without major problems. ... Both Hindi and Urdu developed from Classical Sanskrit, which appeared in the Indus Valley (modern Pakistan and northwest India) at about the start of the Common Era. The first old Hindi (or Apabhransha) poetry was written in the year 769 AD, and by the European Middle Ages it became known as 'Hindvi'. Muslim Turks invaded the Punjab in 1027 and took control of Delhi in 1193. They paved the way for the Islamic Mughal Empire, which ruled northern India from the 16th century until it was defeated by the British Raj in the mid-19th century. It was at this time that the language of this book began to take form, a mixture of Hindvi grammar with Arabic, Persian and Turkish vocabulary. The Muslim speakers of Hindvi began to write in the Arabic script, creating Urdu, while the Hindu population incorporated the new words but continued to write in Devanagari script.

- Holt, P. M.; Lambton, Ann K. S.; Lewis, Bernard, eds. (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 723. ISBN 0-521-29138-0.

- Sanjay Subrahmanyam (2017). Europe's India: Words, People, Empires, 1500–1800. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674977556.

- Christine Everaert (2010). Tracing the Boundaries Between Hindi and Urdu. ISBN 978-9004177314.

- Varma, Siddheshwar (1973). G. A. Grierson's Linguistic Survey of India.

- Khan, Abdul Jamil (2006). Urdu/Hindi: An Artificial Divide: African Heritage, Mesopotamian Root. ISBN 9780875864372.

- David Prochaska, Edmund Burke III (July 2008). Genealogies of Orientalism: History, Theory, Politics. Nebraska Paperback.

- Rahman, Tariq (2000). "The Teaching of Urdu in British India" (PDF). The Annual of Urdu Studies. 15: 55. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2014.

- Hutchinson, John; Smith, Anthony D. (2000). Nationalism: Critical Concepts in Political Science. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-20112-4.

In the nineteenth century in north India, before the extension of the British system of government schools, Urdu was not used in its written form as a medium of instruction in traditional Islamic schools, where Muslim children were taught Persian and Arabic, the traditional languages of Islam and Muslim culture. It was only when the Muslim elites of north India and the British decided that Muslims were backward in education in relation to Hindus and should be encouraged to attend government schools that it was felt necessary to offer Urdu in the Persian-Arabic script as an inducement to Muslims to attend the schools. And it was only after the Hindi-Urdu controversy developed that Urdu, once disdained by Muslim elites in north India and not even taught in the Muslim religious schools in the early nineteenth century, became a symbol of Muslim identity second to Islam itself. A second point revealed by the Hindi-Urdu controversy in north India is how symbols may be used to separate peoples who, in fact, share aspects of culture. It is well known that ordinary Muslims and Hindus alike spoke the same language in the United Provinces in the nineteenth century, namely Hindustani, whether called by that name or whether called Hindi, Urdu, or one of the regional dialects such as Braj or Awadhi. Although a variety of styles of Hindi-Urdu were in use in the nineteenth century among different social classes and status groups, the legal and administrative elites in courts and government offices, Hindus and Muslims alike, used Urdu in the Persian-Arabic script.

- Sachchidananda Sinha (1911). The Hindustan Review: Volume 23. University of Wisconsin- Madison. p. 243.

- McGregor, Stuart (2003), "The Progress of Hindi, Part 1", Literary cultures in history: reconstructions from South Asia, p. 912, ISBN 978-0-520-22821-4 in Pollock (2003)

- Ali, Syed Ameer (1989). The Right Hon'ble Syed Ameer Ali: Political Writings. APH Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 978-81-7024-247-5.

- Clyne, Michael (24 May 2012). Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-088814-0.

- King, Christopher Rolland (1999). One Language, Two Scripts: The Hindi Movement in Nineteenth Century North India. Oxford University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-19-565112-6.

British language policy both resulted from and contributed to the larger political processes which eventually led to the partition of British India into India and Pakistan, an outcome almost exactly paralleled by the linguistic partition of the Hindi-Urdu continuum into highly Sanskritized Hindi and highly Persianized Urdu.

- Ahmad, Irfan (20 November 2017). Religion as Critique: Islamic Critical Thinking from Mecca to the Marketplace. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-1-4696-3510-1.

There have been and are many great Hindu poets who wrote in Urdu. And they learned Hinduism by readings its religious texts in Urdu. Gulzar Dehlvi—who nonliterary name is Anand Mohan Zutshi (b. 1926)—is one among many examples.

- "Why did the Quaid make Urdu Pakistan's state language? | ePaper | DAWN.COM". epaper.dawn.com. 25 December 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Ahmad, Aijazuddin (2009). Geography of the South Asian Subcontinent: A Critical Approach. Concept Publishing Company. p. 119. ISBN 978-81-8069-568-1.

- Raj, Ali (30 April 2017). "The case for Urdu as Pakistan's official language". Herald Magazine. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Hakala, Walter (2012). "Languages as a Key to Understanding Afghanistan's Cultures" (PDF). Afghanistan: Multidisciplinary Perspectives.

- Hakala, Walter N. (2012). "Languages as a Key to Understanding Afghanistan's Cultures" (PDF). National Geographic. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

In the 1980s and '90s, at least three million Afghans--mostly Pashtun--fled to Pakistan, where a substantial number spent several years being exposed to Hindi language media, especially Bollywood films and songs, and being educated in Urdu-language schools, both of which contributed to the decline of Dari, even among urban Pashtuns.

- Krishnamurthy, Rajeshwari (28 June 2013). "Kabul Diary: Discovering the Indian connection". Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

Most Afghans in Kabul understand and/or speak Hindi, thanks to the popularity of Indian cinema in the country.

- "Who Can Be Pakistani?". thediplomat.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- Vanita, R. (2012). Gender, Sex, and the City: Urdu Rekhti Poetry in India, 1780-1870. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-01656-0.

Desexualizing campaigns dovetailed with the attempt to purge Urdu of Sanskrit and Prakrit words at the same time as Hindi literateurs tried to purge Hindi of Persian and Arabic words. The late-nineteenth century politics of Urdu and Hindi, later exacerbated by those of India and Pakistan, had the unfortunate result of certain poets being excised from the canon.

- Zecchini, Laetitia (31 July 2014). Arun Kolatkar and Literary Modernism in India: Moving Lines. A&C Black. ISBN 9781623565589.

- Rahman, Tariq (2014), Pakistani English (PDF), Quaid-i-Azam University=Islamabad, p. 9, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2014, retrieved 18 October 2014

- Bruce, Gregory Maxwell. "2 The Arabic Element". Urdu Vocabulary: A Workbook for Intermediate and Advanced Students, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2022, pp. 55-156. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781474467216-005

- Shackle, C. (1990). Hindi and Urdu Since 1800: A Common Reader. Heritage Publishers. ISBN 9788170261629.

- A History of Indian Literature: Struggle for freedom: triumph and tragedy, 1911–1956. Sahitya Akademi. 1991. ISBN 9788179017982.

- Kachru, Braj (2015). Collected Works of Braj B. Kachru: Volume 3. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-3713-5.

The style of Urdu, even in Pakistan, is changing from "high" Urdu to colloquial Urdu (more like Hindustani, which would have pleased M.K. Gandhi).

- Ashmore, Harry S. (1961). Encyclopaedia Britannica: a new survey of universal knowledge, Volume 11. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 579.

The everyday speech of well over 50,000,000 persons of all communities in the north of India and in West Pakistan is the expression of a common language, Hindustani.

- Oh Calcutta, Volume 6. 1977. p. 15. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

It is generally admitted that Urdu is a dying language. What is not generally admitted is that it is a dying National language. What used to be called Hindustani, the spoken language of the largest number of Indians, contains more elements of Urdu than Sanskrit academics tolerate, but it is still the language of the people.

- "Urdu Is Alive and Moving Ahead With Times: Gulzar". Outlook. 13 February 2006. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- Gulzar (11 June 2006). "Urdu is not dying: Gulzar". The Hindustan Times.

- Daniyal, Shoaib (1 June 2016). "The death of Urdu in India is greatly exaggerated – the language is actually thriving". Scroll.in. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- Mir, Ali Husain; Mir, Raza (2006). Anthems of Resistance: A Celebration of Progressive Urdu Poetry. New Delhi: Roli Books Private Limited. p. 118. ISBN 9789351940654. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

Phrases like 'dying language' are often used to describe the condition of Urdu in India and indicators like 'the number of Urdu-medium schools' present a litany of bad news with respect to the present conditions and future of the language.

- Journal of the Faculty of Arts, Volume 2. Aligarh Muslim University. 1996. p. 42. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

Arvind Kala is not much off the mark when he says 'Urdu is a dying language (in India), but it is Hindi movie dialogues which have heightened appreciation of Urdu in India. Thanks to Hindi films, knowledge of Urdu is seen as a sign of sophistication among the cognoscent of the North.'

- Singh, Khushwant (2011). Celebrating the Best of Urdu Poetry. Penguin UK. pp. 9–10. ISBN 9789386057334. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- Hanan Irfan (15 July 2021). "The Burden of Urdu Must Be Shared". LiveWire. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- Shoaib Daniyal (4 July 2018). "Surging Hindi, shrinking South Indian languages: Nine charts that explain the 2011 language census". Scroll.in. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- John Willoughby & Zehra Aftab (2020). "The Fall of Urdu and the Triumph of English in Pakistan: A Political Economic Analysis" (PDF). PIDE Working Papers. Pakistan Institute of Development Economics. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- Brass, Paul R. (2005). Language, Religion and Politics in North India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 136. ISBN 9780595343942. Retrieved 1 August 2021.