Dick Tracy (1990 film)

Dick Tracy is a 1990 American action crime comedy film based on the 1930s comic strip character of the same name created by Chester Gould. Warren Beatty produced, directed, and starred in the film, whose supporting cast includes Al Pacino, Madonna, Glenne Headly, and Charlie Korsmo. Dick Tracy depicts the detective's romantic relationships with Breathless Mahoney and Tess Trueheart as well as his conflicts with crime boss Alphonse "Big Boy" Caprice and his henchmen. Tracy also begins fostering a young street urchin named Kid.

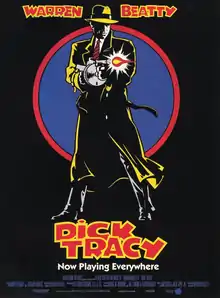

| Dick Tracy | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Warren Beatty |

| Written by | Jim Cash Jack Epps Jr. |

| Based on | Characters by Chester Gould |

| Produced by | Warren Beatty |

| Starring | Warren Beatty Al Pacino |

| Cinematography | Vittorio Storaro |

| Edited by | Richard Marks |

| Music by | Danny Elfman |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Pictures Distribution |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 105 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $46 million[2] |

| Box office | $162.7 million[3] |

Development of the film began in the early 1980s with Tom Mankiewicz assigned to write the script. The screenplay was written instead by Jim Cash and Jack Epps Jr., both of Top Gun fame. The project also went through directors Steven Spielberg, John Landis, Walter Hill, and Richard Benjamin before the arrival of Beatty. It was filmed mainly at Universal Studios. Danny Elfman was hired to compose the score, and the film's music was featured on three separate soundtrack albums.

Dick Tracy premiered at the Uptown Theatre in Washington, D.C., on June 10, 1990 and was released nationwide a day later. Reviews ranged from favorable to mixed, with positive comments on Madonna's acting and Beatty's direction. The film was a success at the box office and at awards time. It garnered seven Academy Award nominations, winning in three of the categories: Best Original Song, Best Makeup, and Best Art Direction.[4] Dick Tracy is remembered today for its visual style.

Plot

In 1938,[5][6] at an illegal card game, a 10-year-old young street urchin witnesses the massacre of a group of mobsters at the hands of Flattop and Itchy, two of the hoods on the payroll of Alphonse "Big Boy" Caprice. Big Boy's crime syndicate is aggressively taking over small businesses in the city. Detective Dick Tracy catches the urchin (who calls himself "Kid") in an act of petty theft. After rescuing him from a ruthless host, Tracy temporarily adopts him with the help of his girlfriend, Tess Trueheart.

Meanwhile, Big Boy coerces club owner Lips Manlis into signing over the deed to Club Ritz. He then kills Lips with a cement overcoat (referred to onscreen as "The Bath") and steals his girlfriend, the seductive and sultry singer Breathless Mahoney. After Lips is reported missing, Tracy interrogates his three hired guns Flattop, Itchy, and Mumbles, then goes to the club to arrest Big Boy for Lips' murder. Breathless is the only witness. Instead of providing testimony, she unsuccessfully attempts to seduce Tracy. Big Boy cannot be indicted, and he is released from jail. Big Boy's next move is to try to bring other criminals, including Spud Spaldoni, Pruneface, Influence, Texie Garcia, Ribs Mocca, and Numbers, together under his leadership. Spaldoni refuses and is killed with a carbomb, leaving Dick Tracy, who discovered the meeting and was attempting to spy on it, wondering what is going on. The next day, Big Boy and his henchmen kidnap Tracy and attempt to bribe him; Tracy rebuffs them, prompting the criminals to attempt to kill him. However, Tracy is saved by Kid, who is then bestowed by the police with an honorary detective certificate, which will remain temporary until he decides on a legitimate name for himself.

Breathless shows up at Tracy's apartment, once again in an attempt to seduce him. Tracy allows her to kiss him. Tess witnesses this scene and eventually leaves town. Tracy leads a seemingly unsuccessful raid on Club Ritz, but it is actually a diversion so that Officer "Bug" Bailey can enter the building to operate a secretly installed listening device so the police can listen in on Big Boy's criminal activities. The resultant raids all but wipe out Big Boy's criminal empire. However, Big Boy discovers Bug, and captures him for a trap planned by Influence and Pruneface to kill Tracy in the warehouse. In the resulting gun battle, a stranger with no face called "The Blank" steps out of the shadows to save Tracy after he is cornered, and kills Pruneface. Influence escapes as Tracy rescues Bug from the fate that befell Lips Manlis, and Big Boy is enraged to hear that The Blank foiled the hit. Tracy again attempts to extract the testimony from Breathless that he needs to put Big Boy away. She agrees to testify only if Tracy agrees to give in to her advances. Tess eventually has a change of heart, but before she can tell Tracy, she is kidnapped by The Blank, with the help of Big Boy's club piano player, 88 Keys. Tracy is drugged and rendered unconscious by The Blank, then framed for murdering the corrupt District Attorney John Fletcher, whereupon he is detained by the police. The Kid, meanwhile, adopts the name "Dick Tracy, Jr."

Big Boy's business thrives until The Blank frames him for Tess' kidnapping. Released by his colleagues on New Year's Eve, Tracy interrogates Mumbles, and arrives at a gun battle outside the Club Ritz where Big Boy's men are killed or captured by Tracy and the police. Abandoning his crew, Big Boy flees to a drawbridge and ties Tess to its gears before he is confronted by Tracy. Their fight is halted when The Blank appears and holds both men at gunpoint, offering to share the city with Tracy after Big Boy is dead. When Junior arrives, Big Boy takes advantage of the distraction and opens fire before Tracy sends him falling to his death in the bridge's gears, while Junior rescues Tess. Mortally wounded, The Blank is unmasked to reveal Breathless Mahoney, who kisses Tracy before dying. All charges against Tracy are dropped.

Later, Tracy proposes to Tess, but is interrupted by the report of a robbery in progress. He leaves her with the ring before he and Dick Tracy, Jr., depart to respond to the robbery.

Cast

- Main characters

- Warren Beatty as Dick Tracy: a square-jawed, fast-shooting, hard-hitting, and intelligent police detective sporting a yellow overcoat and fedora. He is heavily committed to breaking the hold that organized crime has on the city. In addition, Tracy is in line to become the chief of police, which he scorns as a "desk job".

- Al Pacino as Alphonse "Big Boy" Caprice: the leading crime boss of the city. Although he is involved with numerous criminal activities, they remain unproven, as Tracy has never been able to catch him in the act or find a witness to testify.

- Madonna as Breathless "The Blank" Mahoney: an entertainer at Club Ritz who wants to steal Tracy from his girlfriend. She is also the sole witness to several of Caprice's crimes.

- Glenne Headly as Tess Trueheart: Dick Tracy's girlfriend. She feels that Tracy cares more for his job than for her.

- Charlie Korsmo as The Kid: a 10-year-old scrawny street orphan who survives by eating out of garbage cans and is a protege of Steve the Tramp. He falls into the life of both Tracy and Trueheart and becomes an ally. He becomes Tracy's protege then, adopting the name "Dick Tracy, Jr.".

- Law enforcement

- James Keane as Pat Patton: Tracy's closest associate and second-in-command.

- Seymour Cassel as Sam Catchem: Tracy's closest associate and third-in-command.

- Michael J. Pollard as Bug Bailey: a surveillance expert.

- Charles Durning as Chief Brandon: the chief of police who supports Tracy's crusade.

- Dick Van Dyke as District Attorney John Fletcher: a corrupt district attorney who refuses to prosecute Caprice as he is on Caprice's payroll.

- Frank Campanella as Judge Harper

- Kathy Bates as Mrs. Green: a stenographer

- The mob

- Dustin Hoffman as Mumbles: Caprice's fast-talking henchman.

- William Forsythe as Flattop: Caprice's top hitman. His most distinguishing feature is his square, flat cranium and matching haircut.

- Ed O'Ross as Itchy: Caprice's other hitman. He is usually paired with Flattop.

- James Tolkan as Numbers: Caprice's accountant.

- Mandy Patinkin as 88 Keys: a piano player at Club Ritz who becomes The Blank's minion.

- R. G. Armstrong as Pruneface: a deformed crime boss who becomes one of Caprice's minions.

- Henry Silva as Influence: Pruneface's sinister top gunman.

- Paul Sorvino as Lips Manlis: the original owner of Club Ritz and Caprice's mentor.

- Chuck Hicks as The Brow: a criminal with a large, wrinkled forehead.

- Neil Summers as Rodent: a criminal with a pointed nose, small eyes, and buck teeth.

- Stig Eldred as Shoulders: a criminal with broad shoulders.

- Lawrence Steven Meyers as Little Face: a criminal with a big head and a small face.

- James Caan as Spud Spaldoni: a crime boss who refuses to submit to Caprice.

- Catherine O'Hara as Texie Garcia: a female criminal who submits to Caprice.

- Robert Beecher as Ribs Mocca: a criminal who submits to Caprice.

- Others

- Rita Bland, Lada Boder, Dee Hengstler, Liz Imperio, Michelle Johnston, Karyne Ortega and Karen Russell as Breathless Mahoney's dancers at Club Ritz

- Lew Horn as Lefty Moriarty

- Mike Hagerty as Doorman

- Arthur Malet as Diner Patron

- Bert Remsen as Bartender

- Jack Kehoe as Customer at Raid

- Michael Donovan O'Donnell as McGillicuddy

- Tom Signorelli as Mike: proprietor of the diner Tracy frequents

- Jim Wilkey as Stooge

- Mary Woronov as Welfare Person

Estelle Parsons portrays Tess Trueheart's mother. Tony Epper plays Steve the Tramp. Hamilton Camp appears as a store owner and Bing Russell plays a Club Ritz patron. Robert Costanzo cameos as Lips Manlis' bodyguard, and Marshall Bell briefly appears as a goon of Big Boy Caprice who poses as an arresting officer to ensnare Lips. Allen Garfield, John Schuck, and Charles Fleischer make cameos as reporters. Walker Edmiston, John Moschitta Jr., and Neil Ross provide the voices of each radio announcer. Colm Meaney appears as a police officer at Tess Trueheart's home. Mike Mazurki (who played Splitface in the original Dick Tracy film) appears in a small cameo, as Old Man at Hotel. 93-year-old veteran character actor Ian Wolfe plays his last film role as "Munger".

Production

Development

Beatty had a concept for a Dick Tracy film in 1975. At the time, the film rights were owned by Michael Laughlin, who gave up his option from Tribune Media Services after he was unsuccessful in pitching Dick Tracy to Hollywood studios. Floyd Mutrux and Art Linson purchased the film rights from the Tribune in 1977,[7] and, in 1980, United Artists became interested in financing/distributing Dick Tracy. Tom Mankiewicz was under negotiations to write the script, based on his previous success with Superman (1978) and Superman II (1980). The deal fell through when Chester Gould, creator of the Dick Tracy comic strip, insisted on strict financial and artistic control.[8]

That same year, Mutrux and Linson eventually took the property to Paramount Pictures, who began developing screenplays, offered Steven Spielberg the director's position, and brought in Universal Pictures to co-finance. Universal put John Landis forward as a candidate for director, courted Clint Eastwood for the title role, and commissioned Jim Cash and Jack Epps, Jr. to write the screenplay. "Before we were brought on, there were several failed scripts at Universal," reflected Epps, "then it went dormant, but John Landis was interested in Dick Tracy, and he brought us in to write it."[9] Cash and Epps' simple orders from Landis were to write the script in a 1930s pulp magazine atmosphere and center it with Alphonse "Big Boy" Caprice as the primary villain. For research, Epps read every Dick Tracy comic strip from 1930 to 1957. The writers wrote two drafts for Landis; Max Allan Collins, then-writer of the Dick Tracy comic strip, remembers reading one of them. "It was terrible. The only positive thing about it was a thirties setting and lots of great villains, but the story was paper-thin and it was uncomfortably campy."[9]

In addition to Beatty and Eastwood, other actors who were considered for the lead role included Harrison Ford, Richard Gere, Tom Selleck, and Mel Gibson.[10] Landis left Dick Tracy following the controversial on-set accident on Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983), in which three actors were killed.[9] Walter Hill then came on board to direct with Joel Silver as producer. Cash and Epps wrote another draft, and Hill approached Warren Beatty for the title role. Pre-production had progressed as far as set building, but the film was stalled when artistic control issues arose with Beatty, a fan of the Dick Tracy comic strip.[11] Hill wanted to make the film violent and realistic, while Beatty envisioned a stylized homage to the 1930s comic strip.[7] The actor also reportedly wanted $5 million plus fifteen percent of the box office gross, a deal which Universal refused to accept.[11]

Hill and Beatty left the film, which Paramount began developing as a lower-budget project with Richard Benjamin directing. Cash and Epps continued to rewrite the script, but Universal was unsatisfied. The film rights eventually reverted to Tribune Media Services in 1985. However, Beatty decided to option the Dick Tracy rights himself for $3 million,[12] along with the Cash/Epps script. When Jeffrey Katzenberg and Michael Eisner moved from Paramount to the Walt Disney Studios, Dick Tracy resurfaced with Beatty as director, producer and leading man.[11] Katzenberg considered hiring Martin Scorsese to direct the film,[13] but changed his mind. "It never occurred to me to direct the movie," Beatty admitted, "but finally, like most of the movies that I direct, when the time comes to do it, I just do it because it's easier than going through what I'd have to go through to get somebody else to do it."[11]

Beatty's reputation for directorial profligacy, notably with the critically acclaimed Reds (1981), did not sit well with Disney.[11] As a result, Beatty and Disney reached a contracted agreement whereby any budget overruns on Dick Tracy would be deducted from Beatty's fee as producer, director, and star.[14] Beatty and regular collaborator Bo Goldman significantly rewrote the dialogue but lost a Writers Guild arbitration and did not receive screen credit.[7]

Disney greenlit Dick Tracy in 1988 under the condition that Beatty keep the production budget within $25 million.[7] Beatty's fee was $7 million against 15% of the gross (once the distributor's gross reached $50 million).[12] Costs began to rise once filming started and quickly jumped to $30 million[15] and its total negative cost ended up being $46.5 million: $35.6 million of direct expenditure, $5.3 million in studio overhead and $5.6 million in interest.[12] Disney spent an additional $48.1 million on advertising and publicity and $5.8 million on prints, resulting in a total of $101 million spent overall.[12] The financing for Dick Tracy came from Disney and Silver Screen Partners IV, as well as Beatty's own production company, Mulholland Productions. Disney was originally going to release the film under the traditional Walt Disney Pictures banner,[16] but chose instead to release and market the film under the adult-oriented Touchstone Pictures label leading up to the film's theatrical debut, because the studio felt it had too many mature themes for a Disney-branded film.[17]

Casting

Although Al Pacino was Beatty's first choice for the role of Alphonse "Big Boy" Caprice, Robert De Niro was under consideration.[18] Michelle Pfeiffer, Kathleen Turner and Kim Basinger were too expensive to cast as Breathless Mahoney. Sharon Stone auditioned for the role but she was turned down.[19][20] Madonna pursued the part of Breathless Mahoney, offering to work for scale.[21] Her resulting paycheck for the film was just $35,000.[7] Sean Young claims she was forced out of the role of Tess Truehart (which eventually went to Glenne Headly) after rebuffing sexual advances from Beatty. In a 1989 statement, Beatty said, "I made a mistake casting Sean Young in the part and I felt very badly about it."[22] Mike Mazurki, who had appeared in Dick Tracy (1945) had a cameo. Beatty approached Gene Hackman to do a cameo in the film, but he declined.[23]

Filming

Principal photography for Dick Tracy began on February 2, 1989.[24] The filmmakers considered shooting the film on-location in Chicago, but production designer Richard Sylbert believed Dick Tracy would work better using sound stages and backlots[25] at Universal Studios in Universal City, California.[24] Other filming took place at Warner Bros. Studios in Burbank.[26] In total, 53 interior and 25 exterior sets were constructed. Beatty, being a perfectionist, often filmed dozens of takes of every scene.[24]

As filming continued, Disney and Max Allan Collins conflicted over the novelization. The studio rejected his manuscript: "I wound up doing an eleventh hour rewrite that was more faithful to the screenplay, even while I made it much more consistent with the strip," Collins continued, "and fixed as many plot holes as I could."[24] Disney did not like this version either, but accepted based on Beatty's insistence to incorporate some of Collins' writing into the shooting script, which solved the plot hole concerns. Through post-production dubbing, some of Collins' dialogue was also incorporated into the film. Principal photography for Dick Tracy ended in May 1989.[24]

Design

Early in the development of Dick Tracy, Beatty decided to make the film using a palette limited to just seven colors, primarily red, green, blue and yellow—to evoke the film's comic strip origins; furthermore each of the colors was to be exactly the same shade. Beatty's design team included production designer Richard Sylbert, set decorator Rick Simpson, cinematographer Vittorio Storaro (whom Beatty had worked with on his previous film, Ishtar, as producer and lead actor), visual effects supervisors Michael Lloyd and Harrison Ellenshaw, prosthetic makeup designers John Caglione, Jr. and Doug Drexler, and costume designer Milena Canonero. Their main intention was to stay close to Chester Gould's original drawings from the 1930s. Other influences came from the Art Deco movement and German Expressionism.[27]

For Storaro, the limited color palette was the most challenging aspect of production. "These are not the kind of colors the audience is used to seeing," he noted. "These are much more dramatic in strength, in saturation. Comic strip art is usually done with very simple and primitive ideas and emotions," Storaro theorized. "One of the elements is that the story is usually told in vignette, so what we tried to do is never move the camera at all. Never. Try to make everything work into the frame."[10] For the matte paintings, Ellenshaw and Lloyd executed over 57 paintings on glass, which were then optically combined with the live action. For a brief sequence in which The Kid dashes in front of a speeding locomotive, only 150 feet (46 m) of real track was laid; the train itself was a 2-foot (0.61 m) scale model, and the surrounding trainyard a matte painting.[25] The film was one of the last major American studio blockbusters to have no computer-generated imagery.

Caglione and Drexler were recommended for the prosthetic makeup designs by Canonero, with whom they had worked on The Cotton Club (1984). The rogues gallery makeup designs were taken directly from Gould's drawings,[28] with the exception of Al Pacino (Big Boy Caprice), who improvised his own design, ignoring the rather overweight character of the strip.[25] His makeup took 3.5 hours to apply.[29]

Music

"Directors don't know anything about music really, and if they do, it's not necessarily a help. Warren Beatty is a pianist and knows much more about music than almost any director, but when he and I started on Dick Tracy, communicating on a musical level was getting us nowhere because it is all so interpretive. We started having much more success when we started talking on a strictly gut level."

— Danny Elfman[30]

Beatty hired Danny Elfman to compose the film score based on his previous success with Batman (1989). Elfman enlisted the help of Oingo Boingo bandmate Steve Bartek and Shirley Walker to arrange compositions for the orchestra. "In a completely different way," Elfman commented, "Dick Tracy has this unique quality that Batman had for me. It gives an incredible sense of non-reality."[31] In addition, Beatty hired acclaimed songwriter Stephen Sondheim to write five original songs: "Sooner or Later (I Always Get My Man)," "More," "Live Alone and Like It," "Back in Business," and "What Can You Lose?". "Sooner or Later" and "More" were performed by Madonna, with "What Can You Lose?" being a duet with Mandy Patinkin. Mel Tormé sang "Live Alone and Like It," and "Back in Business" was performed by Janis Siegel, Cheryl Bentyne, and Lorraine Feather. "Back in Business" and "Live Alone and Like It" were both used as background music during montage sequences.[32] "Sooner or Later" and "Back in Business" were featured in the original 1992 production of the Sondheim revue Putting It Together in Oxford, England, and four of the five Sondheim songs from Dick Tracy (the exception being "What Can You Lose?") were used in the 1999 Broadway production of Putting It Together. A short opera sequence in the film was composed by Thomas Pasatieri [33]

Dick Tracy is also the first film to use digital audio.[34] In a December 1990 interview with The New York Times, Elfman criticized the growing tendency to use digital technology for sound design and dubbing purposes. "I detest contemporary scoring and dubbing in cinema. Film music as an art took a deep plunge when Dolby stereo hit. Stereo has the capacity to make orchestral music sound big and beautiful and more expansive, but it also can make sound effects sound four times as big. That began the era of sound effects over music."[30]

Marketing

.jpg.webp)

Disney modeled its marketing campaign after the 1989 success of Batman, which was based on high concept promotion. This included a McDonald's promotional tie-in and a Warren Beatty interview conducted by Barbara Walters on 20/20. "I find the media's obsession with promotion and demographics upsetting," Beatty said. "I find all this anti-cultural." In attempting to increase awareness for Dick Tracy, Disney added a new Roger Rabbit cartoon short (Roller Coaster Rabbit) and made two specific television advertisements centered on The Kid (Charlie Korsmo). In total, Disney commissioned 28 TV advertisements.[7] Playmates Toys manufactured a line of 14 Dick Tracy figures.[35]

It was Madonna's idea to include the film as part of her Blond Ambition World Tour.[7] Prior to the June 1990 theatrical release, Disney had already featured Dick Tracy in musical theatre stage shows in both Disneyland and the Walt Disney World Resort, using Stephen Sondheim and Danny Elfman's music. The New York Times also wrote in June 1990 of Disney Stores "selling nothing but Tracy-related merchandise".[36] Max Allan Collins lobbied to write the film's novelization long before Disney had even greenlighted Dick Tracy in 1988. "I hated the idea that anyone else would write a Tracy novel," Collins explained. After much conflict with Disney,[10] leading to seven different printings of the novelization,[32] the book was released in May 1990, published by Bantam Books.[37] It sold almost one million copies prior to the film's release.[32] A graphic novel adaptation of the film was also released, written and illustrated by Kyle Baker.[34] Reruns of The Dick Tracy Show began airing to coincide with the release of the film, but stations in Los Angeles and New York pulled and edited the episodes when Asian and Hispanic groups protested that the characters Joe Jitsu and Go Go Gomez were offensive stereotypes.[38][39] A theme park ride for Disneyland, Disney-MGM Studios and Euro Disney Resort called Dick Tracy's Crime Stoppers was planned but ultimately never built.[40] Another tie-in for the movie was an ingenious plan where 1,500 movie theatres were shipped T-shirts with the film's title art on them, which fans could then buy for $12 to $20 and wear into the movie in lieu of buying tickets at the box office.[41]

Reception

Release

Dick Tracy had a benefit premiere at a small 300-seat theater in Woodstock, Illinois (the hometown of Tracy creator Chester Gould), on June 13, 1990[42] while the production premiere occurred the next day at the Walt Disney World Village's Pleasure Island in Lake Buena Vista, Florida.[7][43] The film was released in the United States in 2,332 theaters on June 15, 1990, earning $22.54 million in its opening weekend,[3] including an estimated $1.5 million of t-shirt sales.[44] This was the third-highest opening weekend of 1990[45] and Disney's biggest ever.[44] Dick Tracy eventually grossed $103.74 million in the United States and Canada and $59 million elsewhere, coming to a worldwide total of $162.74 million.[3] Dick Tracy was also the ninth-highest-grossing film of America in 1990,[45] and number twelve in worldwide totals.[46]

Although Disney was impressed by the opening weekend gross,[32] studio management was expecting the film's total earnings to match Batman (1989).[32] Prior to its overseas release (and other revenue streams), the film was estimated to have generated a $57 million deficit for Disney.[12] Studio chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg expressed disappointment in a studio memo that noted that Dick Tracy had cost about $100 million in total to produce, market and promote. "We made demands on our time, talent and treasury that, upon reflection, may not have been worth it," Katzenberg reported.[47]

When released, it was preceded by the Roger Rabbit short Roller Coaster Rabbit.

Critical response

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 64% based on 55 reviews, with an average rating of 5.9/10. The site's critics consensus reads: "Dick Tracy is stylish, unique, and an undeniable technical triumph, but it ultimately struggles to rise above its two-dimensional artificiality."[48] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 68 out of 100, based on 24 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[49] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B+" on an A+ to F scale.[50]

Roger Ebert gave the film four stars in his review, arguing that Warren Beatty succeeded in creating the perfect tone of nostalgia for the film. Ebert mostly praised the matte paintings, art direction and prosthetic makeup design. "Dick Tracy is one of the most original and visionary fantasies I've seen on a screen," he wrote.[51]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote, "Dick Tracy has just about everything required of an extravaganza: a smashing cast, some great Stephen Sondheim songs, all of the technical wizardry that money can buy, and a screenplay that observes the fine line separating true comedy from lesser camp."[52] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly gave a mixed review, but was impressed by Madonna's performance. "Dick Tracy is an honest effort but finally a bit of a folly. It could have used a little less color and a little more flesh and blood," Gleiberman concluded.[53]

In his heavily negative review for The Washington Post, Desson Thomson criticized Disney's hyped marketing campaign and the film in general. "Dick Tracy is Hollywood's annual celebration of everything that's wrong with Hollywood," he stated.[54] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone wrote that Warren Beatty, at 52 years old, was too old for the part. He also found similarities with Batman (1989), in which both films involve "a loner hero, a grotesque villain, a blond bombshell, a marketable pop soundtrack and a no-mercy merchandising campaign," Travers continued. "But Batman possesses something else: a psychological depth that gives the audience a stake in the characters. Tracy sticks to its eye-poppingly brilliant surface. Though the film is a visual knockout, it's emotionally impoverished."[55]

Although Max Allan Collins (then a Dick Tracy comic-strip writer) had conflicts with Disney concerning the novelization, he gave the finished film a positive review. He praised Beatty for hiring an elaborate design team and his decision to mimic the strip's limited color palette. Collins also enjoyed Beatty's performance, both the prosthetic makeup and characterization of the rogues gallery, as well as the Stephen Sondheim music. However, he believed the filmmakers still sacrificed the storyline in favor of the visual design.[34]

Accolades

The film was nominated for seven Academy Awards (winning three), the film is currently tied with Black Panther for having the most wins for a comic book or comic strip movie.

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20/20 Awards | Best Art Direction | Richard Sylbert | Nominated |

| Best Costume Design | Milena Canonero | Nominated | |

| Best Makeup | John Caglione Jr. and Doug Drexler | Nominated | |

| Best Original Song | "Sooner or Later (I Always Get My Man)" Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim |

Won | |

| Academy Awards[56] | Best Supporting Actor | Al Pacino | Nominated |

| Best Art Direction | Richard Sylbert and Rick Simpson | Won | |

| Best Cinematography | Vittorio Storaro | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | Milena Canonero | Nominated | |

| Best Makeup | John Caglione Jr. and Doug Drexler | Won | |

| Best Original Song | "Sooner or Later (I Always Get My Man)" Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim |

Won | |

| Best Sound | Thomas Causey, Chris Jenkins, David E. Campbell and Doug Hemphill | Nominated | |

| American Comedy Awards[57] | Funniest Supporting Actor in a Motion Picture | Al Pacino | Won |

| American Society of Cinematographers Awards[58] | Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography in Theatrical Releases | Vittorio Storaro | Nominated |

| Artios Awards[59] | Outstanding Achievement in Feature Film Casting – Comedy | Jackie Burch | Nominated |

| BMI Film & TV Awards | Film Music Award | Danny Elfman | Won |

| Boston Society of Film Critics Awards[60] | Best Cinematography | Vittorio Storaro (also for The Sheltering Sky) | Won |

| British Academy Film Awards[61] | Best Actor in a Supporting Role | Al Pacino | Nominated |

| Best Costume Design | Milena Canonero | Nominated | |

| Best Editing | Richard Marks | Nominated | |

| Best Make Up Artist | John Caglione Jr. and Doug Drexler | Won | |

| Best Production Design | Richard Sylbert | Won | |

| Best Sound | Dennis Drummond, Thomas Causey, Chris Jenkins, David E. Campbell and Doug Hemphill |

Nominated | |

| Best Special Visual Effects | Nominated | ||

| British Society of Cinematographers[62] | Best Cinematography in a Theatrical Feature Film | Vittorio Storaro | Nominated |

| Chicago Film Critics Association Awards[63] | Best Supporting Actor | Al Pacino | Nominated |

| Dallas–Fort Worth Film Critics Association Awards | Best Supporting Actor | Nominated | |

| Best Cinematography | Vittorio Storaro | Nominated | |

| Golden Globe Awards[64] | Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | Al Pacino | Nominated | |

| Best Original Song – Motion Picture | "Sooner or Later (I Always Get My Man)" Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim |

Nominated | |

| "What Can You Lose?" Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim |

Nominated | ||

| Grammy Awards[65] | Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or for Television | Dick Tracy – Danny Elfman | Nominated |

| Best Song Written Specifically for a Motion Picture or Television | "More" – Stephen Sondheim | Nominated | |

| "Sooner or Later (I Always Get My Man)" – Stephen Sondheim | Nominated | ||

| Nastro d'Argento | Best Foreign Director | Warren Beatty | Nominated |

| National Society of Film Critics Awards[66] | Best Supporting Actor | Al Pacino | 3rd Place |

| Saturn Awards[67] | Best Fantasy Film | Won | |

| Best Actor | Warren Beatty | Nominated | |

| Best Actress | Madonna | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Al Pacino | Nominated | |

| Best Performance by a Younger Actor | Charlie Korsmo | Nominated | |

| Best Costumes | Milena Canonero | Nominated | |

| Best Make-Up | John Caglione Jr., Doug Drexler and Cheri Minns | Won | |

| Young Artist Awards[68] | Most Entertaining Family Youth Motion Picture – Comedy/Horror | Nominated | |

| Best Young Actor Starring in a Motion Picture | Charlie Korsmo | Nominated | |

Legacy

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2003: AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

- Dick Tracy – Nominated Hero[69]

- 2004: AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

- "Sooner or Later (I Always Get My Man)" – Nominated[70]

- 2006: AFI's Greatest Movie Musicals – Nominated[71]

Retrospective reviews called the film exceptionally unique. Writers for Vox[72] and The Atlantic[73] asserted that it was one of the most unique movies ever. Multiple authors contrast it with newer comic book movies.[74] One article calls it a "road[] not taken" in comic book adaptations. The author praised Popeye, Dick Tracy, and Hulk for their use of comic techniques such as "masking, paneling, and page layout" in ways the DC Extended Universe and Marvel Cinematic Universe do not.[75]

The Encyclopedia of Sexism in American Films (2019) found the women of the film are subservient to a male power structure.[76]

Home media release

The film was released on VHS on December 18, 1990, and was first released on DVD in Europe in 2000, but domestic release in the US was delayed until April 2, 2002, and without any special features. Rumors circulated over the web shortly after the US DVD release that Warren Beatty had planned to release a director's cut under Disney's "Vista Series" label; including at least ten extra minutes of footage.[77]

The Blu-ray was released in the US and Canada on December 11, 2012. This release also lacked special features, save for a digital copy.[78]

Possible sequel, legal issues and reboot

Disney had hoped Dick Tracy would launch a successful franchise, like the Indiana Jones series, but Disney halted plans.[2] In addition, executive producers Art Linson and Floyd Mutrux sued Beatty shortly after the release of the film, alleging that they were owed profit participation from the film.[34]

Beatty purchased the Dick Tracy film and television rights in 1985 from Tribune Media Services.[79] He then took the property to Walt Disney Studios, who optioned the rights in 1988. According to Beatty, in 2002, Tribune attempted to reclaim the rights and notified Disney—but not through the process outlined in the 1985 agreement.[80] Beatty, who commented he had "a very good idea"[81] for a sequel, believed Tribune violated various notification procedures that "clouded the title"[81] to the rights and made it "commercially impossible" for him to produce a sequel.[81] He approached Tribune in 2004 to settle the situation, but the company said they had met the conditions to get back the rights.[79]

Disney, which had no intention of producing a sequel, rejected Tribune's claim, and gave Beatty back most of the rights in May 2005.[82] That same month, Beatty filed a lawsuit in the Los Angeles, California Superior Court seeking $30 million in damages against Tribune and a declaration over the rights. Bertram Fields, Beatty's lawyer, said the original 1985 agreement with Tribune was negotiated specifically to allow Beatty a chance to make another Dick Tracy film. "It was very carefully done, and they just ignored it," he stated. "Tribune is a big, powerful company, and they think they can just run roughshod over people. They picked the wrong guy."[81]

Tribune believed the situation would be settled quickly,[83] and was confident enough to begin developing a Dick Tracy live-action television series with Lorenzo di Bonaventura, Robert Newmyer, and Outlaw Productions. The TV show was to have a contemporary setting, comparable to Smallville, and Di Bonaventura commented that if the TV show was successful, a feature film would likely follow.[79] However, an August 2005 ruling by federal judge Dean D. Pregerson cleared the way for Beatty to sue Tribune.[82] The April 2006 hearing ended without a ruling,[84] but in July 2006, a Los Angeles judge ruled that the case could go to trial; Tribune's request to end the suit in their favor was rejected.[85] The legal battle between Beatty and Tribune continued.[86]

In 2008, Beatty enlisted cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki and film critic Leonard Maltin to make Dick Tracy Special for Turner Classic Movies, which featured Beatty as Tracy in a retrospective interview with Maltin.[87][88] Maltin explicitly asked the fictional Tracy if Warren Beatty planned to make a sequel to the 1990 film, and he responded that he'd heard about that, but Maltin needed to ask Beatty himself. By March 2009, Tribune was in Chapter 11 bankruptcy, and lawyers for the company began to declare their ownership of television and film rights to Dick Tracy. "Mr. Beatty's conduct and wrongful claims have effectively locked away certain motion picture and television rights to the Dick Tracy property," lawyers for Tribune wrote in a filing.[86] Fields responded that it was "a nuisance lawsuit by a bankrupt company, and they should be ashamed of themselves".[86]

On March 25, 2011, U.S. District Court Judge Dean D. Pregerson granted Beatty's request for a summary judgment, and ruled in the actor's favor. Judge Pregerson wrote in his order that "Beatty's commencement of principal photography of his television special on November 8, 2008 was sufficient for him to retain the Dick Tracy rights."[89] Beatty's lawyer said the court found that Beatty had done everything contractually required of him to keep the rights to the character.[90]

In June 2011, Beatty confirmed his intention to make a sequel to Dick Tracy, but he refused to discuss details. He said: "I'm gonna make another one [but] I think it's dumb talking about movies before you make them. I just don't do it. It gives you the perfect excuse to avoid making them." When asked when the sequel would get made, he replied: "I take so long to get around to making a movie that I don’t know when it starts."[77]

While there have not been any sequels in either television or motion-picture form, there have been sequels in novel form. Shortly after the release of the 1990 film, Max Allan Collins wrote Dick Tracy Goes to War. The story is set after the commencement of World War II, and involves Dick Tracy's enlistment in the U.S. Navy, working for their Military Intelligence Division (as he did in the comic strip). In the story, Nazi saboteurs Black Pearl and Mrs. Pruneface (Pruneface's widow) set up a sabotage/espionage operation out of Caprice's old headquarters in Club Ritz. For their activities, they recruit B.B. Eyes, The Mole, and Shaky. Their reign of terror, culminating in an attempt to bomb a weapons plant, is averted by Tracy. A year after War was released, Collins wrote a third novel titled Dick Tracy Meets His Match, in which Tracy finally follows through on his marriage proposal to Tess Trueheart.

In April 2016, Beatty again mentioned the possibility of producing a sequel when he attended CinemaCon.[91]

See also

- List of 1990 box office number-one films in the United States

References

- "Dick Tracy (PG)". British Board of Film Classification. July 2, 1990. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- Stewart, pp. 111-115

- "Dick Tracy". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- "1990 (63) Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- VanDerWerff, Emily Todd (June 17, 2015). "Dick Tracy was unlike any other movie made in 1990 — and any movie made today". Vox.

- Roberts, Garyn G (2003). Dick Tracy and American Culture: Morality and Mythology, Text and Context. Jefferson, N.C: McFarland. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-7864-1698-1. OCLC 27977131.

- David Ansen; Pamela Abramson (June 25, 1990). "Tracymania". Newsweek. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dickholtz, Daniel (December 1998). "Steel Dreams: Interview With Tom Mankiewicz". Starlog. pp. 53–57.

- Hughes, pp. 51

- Hughes, pp. 53-54

- Hughes, pp. 52

- Eller, Claudia (October 22, 1990). "'Tracy' cost put at $101 mil". Variety. p. 3.

- Staff (July 1985). "Martin Scorsese to direct Dick Tracy". The Comics Journal. pp. 20–22.

- Staff (July 1990). "Big Shot". Empire.

- John Greenwald; Richard Natale; Janice C. Simpson (May 21, 1990). "Shooting The Works Lights! Camera! Money!". Time. Archived from the original on November 26, 2010. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- Citron, Alan (April 27, 1990). "Disney Takes On Tradition With 'Tracy' : Entertainment: The upcoming movie, which features some violence and overt sexuality, is meant to show that the studio feels the time is right to broaden its appeal". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035.

- "Disney Opts To Release 'Tracy' On Touchstone". Orlando Sentinel. May 25, 1990. Retrieved October 11, 2016.

- David S. Cohen (June 6, 2007). "Al Pacino tackles each role like a novice". Variety. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- Mell, Eila (January 24, 2015). Casting Might-Have-Beens: A Film by Film Directory of Actors Considered for Roles Given to Others. ISBN 9781476609768.

- "Tracymania". Newsweek. June 24, 1990.

- Ira Madison III (August 17, 2016). "Dick Tracy made Madonna Pop Music's Femme Fatale". MTV. Archived from the original on May 7, 2022. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- Irwin, Lew (July 22, 2004). "Young Slams Lecherous Beatty". IMDb. Archived from the original on November 2, 2005. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- Sellers, Robert (July 13, 2010). Hollywood Hellraisers: The Wild Lives and Fast Times of Marlon Brando, Dennis Hopper, Warren Beatty, and Jack Nicholson. ISBN 9781616080358.

- Hughes, pp. 55

- Staff (June 15, 1990). "Strip Show: The Comic Book Look of Dick Tracy". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- Larry Richter (August 13, 1990). "A Soviet Film Re-creates History, But It Makes History in Hollywood". The New York Times.

- Kathleen Beckett-Young (June 10, 1990). "The Movie's Creators Used the Strip To Tease". The New York Times.

- Anne Thompson (July 6, 1990). "Making up is hard to do". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- Richard Corliss'; Elizabeth L. Bland (June 18, 1990). "Extra!". Time. Archived from the original on October 23, 2007. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Larry Richter (December 9, 1990). "Batman? Bartman? Darkman? Elfman". The New York Times.

- Staff (February 23, 1990). "The Elfman Cometh". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- Hughes, pp. 56-58

- "Dick Tracy (1990) - IMDb". IMDb.

- Hughes, pp.59-60

- Carol Lawson (February 15, 1990). "Magic and Money: Show and Sell at Toy Fair". The New York Times.

- Richard W. Stevenson (June 22, 1990). "A Real Blockbuster, Or Merely a Smash?". The New York Times.

- Collins, Max Allan; Cash, Jim (1990). Dick Tracy (Mass Market Paperback). ISBN 0553285289.

- Lynne Heffley; Robert Smaus (July 5, 1990). "Disney's KCAL Comes Under Fire". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- Benjamin Svetkey (July 27, 1990). "News & Notes". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- Fan, Max (April 11, 2008). "A Disney MGM Studios celebration — Part Four — The Dick Tracy Crime Stoppers attraction that never was — original artwork". blogspot.com.au. Retrieved April 21, 2014.

- Eller, Claudia (June 13, 1990). "Should 'Tracy' t-shirt tix tally into the total take?". Variety. p. 7.

- Dellios, Hugh (June 14, 1990). "Woodstock welcomes home Dick Tracy". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- Hinman, Catherine (June 15, 1990). "A Night Atop The Movie World Premiere Of 'Dick Tracy' Comes On Like Gangbusters". The Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- Cohn, Lawrence (June 20, 1990). "'Tracy' and t-shirts grab solid $22.5-mil; 'Another 48 HRS,' 'Recall' staunch". Variety. p. 8.

- "1990 Domestic Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- "1990 Worldwide Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- Larry Richter (February 2, 1991). "Hollywood Abuzz Over Cost Memo". The New York Times. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- "Dick Tracy (1991)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved April 5, 2022.

- "Dick Tracy Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- "CinemaScore". cinemascore.com.

- Ebert, Roger (June 15, 1990). "Dick Tracy". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved April 23, 2009 – via rogerebert.com.

- Canby, Vincent (June 15, 1990). "A Cartoon Square Comes to Life In 'Dick Tracy'". The New York Times.

- Gleiberman, Owen (June 15, 1994). "Movie Review: Dick Tracy". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 23, 2009.

- Thomson, Desson (June 15, 1990). "Dick Tracy". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 23, 2009.

- Travers, Peter (July 12, 1990). "Dick Tracy". Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- "The 63rd Academy Awards (1991) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on October 20, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- "1991 American Comedy Awards". Mubi. American Comedy Awards. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- "The ASC Awards for Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography". Archived from the original on August 2, 2011.

- "Nominees/Winners". Casting Society of America. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- "BSFC Winners: 1990s". Boston Society of Film Critics. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1991". BAFTA. 1991. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- "Best Cinematography in Feature Film" (PDF). Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- "1988-2013 Award Winner Archives". Chicago Film Critics Association. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- "Dick Tracy – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- "1990 Grammy Award Winners". Grammy.com. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- "Past Awards". National Society of Film Critics. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- "Past Saturn Awards". Saturn Awards.org. Archived from the original on September 14, 2008. Retrieved May 7, 2008.

- "12th Annual Youth In Film Awards". YoungArtistAwards.org. Archived from the original on July 16, 2015. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- "AFI's Greatest Movie Musicals Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- VanDerWerff, Emily (June 17, 2015). "Dick Tracy was unlike any other movie made in 1990 — and any movie made today". Vox.

- Sims, David (May 23, 2020). "30 Movies That Are Unlike Anything You've Seen Before". The Atlantic.

- "The Comic-Book Movie Peaked 30 Years Ago, When "Dick Tracy" Came Out". InsideHook.

- Hassler-Forest, Dan (May 25, 2017). Leitch, Thomas (ed.). "Roads Not Taken in Hollywood's Comic Book Movie Industry". The Oxford Handbook of Adaptation Studies. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199331000.013.23. ISBN 978-0-19-933100-0. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- Murguía, Salvador Jiménez; Dymond, Erica Joan; Fennelly, Kristina (2020). The encyclopedia of sexism in American films. Lanham, Maryland. pp. 78–81. ISBN 978-1538115510.

- Warren Beatty Speaks from The Hero Complex Fest! Dick Tracy coming to Blu-Ray! A sequel is in the works! - Ain't It Cool News, June 10, 2011

- "Dick Tracy Blu-ray" – via www.blu-ray.com.

- Fleming, Michael (May 16, 2005). "Outlaw, Tribune team for Tracy". Variety. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- Lew Irwin (August 12, 2005). "Beatty Wins First Round in 'Dick Tracy' Battle". IMDb. Archived from the original on April 28, 2006. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- Staff (May 17, 2005). "Warren Beatty sues Tribune over Dick Tracy". USA Today. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- Cohen, David S. (August 10, 2005). "'Tracy' star makes case". Variety. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- Fleming, Michael (May 22, 2005). "Tracy walks; Beatty balks". Variety. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- Staff (April 4, 2006). "No Ruling in Beatty Lawsuit over Dick Tracy Rights". Fox News. Archived from the original on March 28, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- Stax (July 19, 2006). "Beatty Still Following Dick". IGN. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- "Tribune Company Tries To Secure Rights To Dick Tracy". The New York Times. Associated Press. March 21, 2009.

- Vishnevetsky, Ignatiy (December 1, 2014). "Our Option on Atlas Shrugged Expires in Two Days: 6-Plus Copyright Extensions Disguised as Movies". The A.V. Club.

- "Remembering That Weird TCM Dick Tracy Special". Disney Insider. The Walt Disney Company. July 2015. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- "Warren Beatty prevails in Dick Tracy lawsuit". Reuters. March 25, 2011. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- "Dick Tracy: Warren Beatty finally gets his man". Los Angeles Times. March 25, 2011. Archived from the original on August 22, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- Rainey, James (April 13, 2016). "Warren Beatty Eyeing 'Dick Tracy' Sequel, Howard Hughes Movie Gets Release Date". Variety.

Further reading

- Mike Bonifer (June 1990). Dick Tracy: The Making of the Movie. New York City: Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-34900-7.

- David Hughes (2003). "Dick Tracy". Comic Book Movies. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 0-7535-0767-6.

- James B. Stewart (2005). DisneyWar. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80993-1.

- Max Allan Collins (May 1990). Dick Tracy. Novelization of the film. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-28528-4.