Dmitry Medvedev

Dmitry Anatolyevich Medvedev (Russian: Дмитрий Анатольевич Медведев, IPA: [ˈdmʲitrʲɪj ɐnɐˈtolʲjɪvʲɪtɕ mʲɪdˈvʲedʲɪf]; born 14 September 1965) is a Russian politician who has been serving as the deputy chairman of the Security Council of Russia since 2020.[2] Medvedev also served as the president of Russia between 2008 and 2012 and prime minister of Russia between 2012 and 2020.[3]

Dmitry Medvedev | |

|---|---|

Дмитрий Медведев | |

_(cropped).jpg.webp) Official portrait, 2016 | |

| Deputy Chairman of the Security Council | |

Incumbent | |

| Assumed office 16 January 2020 | |

| Chairman | Vladimir Putin |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Leader of United Russia | |

Incumbent | |

| Assumed office 30 May 2012 | |

| Secretary General | Andrey Turchak |

| Preceded by | Vladimir Putin |

| Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Union State | |

| In office 18 July 2012 – 16 January 2020 | |

| Secretary General | Grigory Rapota |

| Preceded by | Vladimir Putin |

| Succeeded by | Mikhail Mishustin |

| Prime Minister of Russia | |

| In office 8 May 2012 – 16 January 2020 | |

| President | Vladimir Putin |

| First Deputy | Viktor Zubkov Igor Shuvalov Anton Siluanov |

| Preceded by | Vladimir Putin |

| Succeeded by | Mikhail Mishustin |

| President of Russia | |

| In office 7 May 2008 – 7 May 2012 | |

| Prime Minister | Vladimir Putin |

| Preceded by | Vladimir Putin |

| Succeeded by | Vladimir Putin |

| First Deputy Prime Minister of Russia | |

| In office 14 November 2005 – 12 May 2008 Serving with Sergei Ivanov | |

| Prime Minister | Mikhail Fradkov Viktor Zubkov |

| Preceded by | Mikhail Kasyanov |

| Succeeded by | Viktor Zubkov Igor Shuvalov |

| Chief of Staff of the Kremlin | |

| In office 30 October 2003 – 14 November 2005 | |

| President | Vladimir Putin |

| Preceded by | Alexander Voloshin |

| Succeeded by | Sergey Sobyanin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 14 September 1965 Leningrad, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union (now Saint Petersburg, Russia) |

| Political party | United Russia (2012–present) |

| Other political affiliations | CPSU (before 1991) Independent (1991–2011)[1] |

| Spouse | Svetlana Linnik (m. 1993) |

| Domestic partner | Anatoly Medvedev (father) |

| Children | 1 |

| Education | Leningrad State University |

| Signature | |

| Website | Official website |

Medvedev was elected president in the 2008 election. He was regarded as more liberal than his predecessor, Vladimir Putin, who was also appointed prime minister during Medvedev's presidency. Medvedev's top agenda as president was a wide-ranging modernisation programme, aiming at modernising Russia's economy and society, and lessening the country's reliance on oil and gas. During Medvedev's tenure, the New START nuclear arms reduction treaty was signed by Russia and the United States, Russia emerged victorious in the Russo-Georgian War, and recovered from the Great Recession. Medvedev also launched an anti-corruption campaign, despite later being accused of corruption himself.

He served a single term in office and was succeeded by Putin following the 2012 presidential election. Medvedev was then appointed by Putin as prime minister. He resigned along with the rest of the government on 15 January 2020 to allow Putin to make sweeping constitutional changes; he was succeeded by Mikhail Mishustin on 16 January 2020. On the same day, Putin appointed Medvedev to the new office of deputy chairman of the Security Council.[4]

In the views of some analysts, Medvedev's presidency did seem to promise positive changes, both at home and in ties with the West, signaling "the possibility of a new, more liberal period in Russian politics"; however, he later seemed to adopt increasingly radical positions.[5][6][7]

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Former Prime Minister of Russia Political views

Elections

Presidency

Premiership

|

||

Early life and education

Dmitry Medvedev was born on 14 September 1965 in Leningrad, in the Soviet Union. His father, Anatoly Afanasyevich Medvedev (November 1926 – 2004), was a chemical engineer teaching at the Leningrad State Institute of Technology.[8][9] Dmitry's mother, Yulia Veniaminovna Medvedeva (née Shaposhnikova, born 21 November 1939),[10] studied languages at Voronezh University and taught Russian at Herzen State Pedagogical University. Later, she would also work as a tour guide at Pavlovsk Palace. The Medvedevs lived in a 40 m2 apartment at 6 Bela Kun Street in the Kupchino Municipal Okrug (district) of Leningrad.[11][12] Dmitry was his parents' only child. The Medvedevs were regarded at the time as a Soviet intelligentsia family.[12] His maternal grandparents were Ukrainians whose surname was Kovalev, originally Koval. Medvedev traces his family roots to the Belgorod region.[13]

As a child, Medvedev was intellectually curious, described by his first grade teacher Vera Smirnova as a "dreadful why-asker". After school, he would spend some time playing with his friends before hurrying home to work on his assignments. In the third grade, Medvedev studied the ten-volume Small Soviet Encyclopedia belonging to his father.[12] In the second and third grades, he showed interest in dinosaurs and memorised primary Earth's geologic development periods, from the Archean up to the Cenozoic. In the fourth and fifth grades he demonstrated interest in chemistry, conducting elementary experiments. He was involved to some degree with sport. In grade seven, his adolescent curiosity blossomed through his relationship with Svetlana Linnik, his future wife, who was studying at the same school in a parallel class.[12] This apparently affected Medvedev's school performance. He calls the school's final exams in 1982 a "tough period when I had to mobilize my abilities to the utmost for the first time in my life."[11][14]

Student years and academic career

In the autumn of 1982, 17-year-old Medvedev enrolled at Leningrad State University to study law. Although he also considered studying linguistics, Medvedev later said he never regretted his choice, finding his chosen subject increasingly fascinating, stating that he was lucky "to have chosen a field that genuinely interested him and that it was really 'his thing'".[11][12] Fellow students described Medvedev as a correct and diplomatic person who in debates presented his arguments firmly, without offending.[12]

During his student years, Medvedev was a fan of the English rock bands Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin, and Deep Purple. He was also fond of sports, and participated in athletic competitions in rowing and weight-lifting.[15]

He graduated from the Leningrad State University Faculty of Law in 1987 (together with Ilya Yeliseyev, Anton Ivanov, Nikolay Vinnichenko and Konstantin Chuychenko, who later became associates). After graduating, Medvedev considered joining the prosecutor's office to become an investigator however, he took an opportunity to pursue graduate studies as the civil law chair, deciding to accept three budget-funded post-graduate students to work at the chair itself.[11]

In 1990, Medvedev defended his dissertation titled, "Problems of Realisation of Civil Juridical Personality of State Enterprise" and received his Doctor of Juridical Science (Candidate of Juridical Sciences) degree in civil law.[16]

Anatoly Sobchak, a major democratic politician of the 1980s and 1990s was one of Medvedev's professors at the university. In 1988, Medvedev joined Sobchak's team of democrats and served as the de facto head of Sobchak's successful campaign for a seat in the new Soviet parliament, the Congress of People's Deputies of the USSR.[17]

After Sobchak's election campaign Medvedev continued his academic career in the position of docent at his alma mater, now renamed Saint Petersburg State University.[18] He taught civil and Roman law until 1999. According to one student, Medvedev was a popular teacher; "strict but not harsh". During his tenure Medvedev co-wrote a popular three-volume civil law textbook which over the years has sold a million copies.[12] Medvedev also worked at a small law consultancy firm which he had founded with his friends Anton Ivanov and Ilya Yeliseyev, to supplement his academic salary.[12]

Early career

Career in St Petersburg

In 1990, Anatoly Sobchak returned from Moscow to become chairman of the Leningrad City Council. Sobchak hired Medvedev who had previously headed his election campaign. One of Sobchak's former students, Vladimir Putin, became an adviser. The next summer, Sobchak was elected Mayor of the city, and Medvedev became a consultant to City Hall's Committee for Foreign Affairs. It was headed by Putin.[11][12]

In November 1993, Medvedev became the legal affairs director of Ilim Pulp Enterprise (ILP), a St. Petersburg-based timber company. Medvedev aided the company in developing a strategy as the firm launched a significant expansion. Medvedev received 20% of the company's stock. In the next seven years Ilim Pulp Enterprise became Russia's largest lumber company with an annual revenue of around $500 million. Medvedev sold his shares in ILP in 1999. He then took his first job at the central government of Russia. The profits realised by Medvedev are unknown.[12]

Career in the central government

In June 1996, Medvedev's colleague Vladimir Putin was brought into the Russian presidential administration. Three years later, on 16 August 1999, he became Prime Minister of Russia. Three months later, in November 1999, Medvedev became one of several from St. Petersburg brought in by Vladimir Putin to top government positions in Moscow. On 31 December, he was appointed deputy head of the presidential staff, becoming one of the politicians closest to future President Putin. On 17 January 2000, Dmitry Medvedev was promoted to 1st class Active State Councillor of the Russian Federation (the highest federal state civilian service rank) by the Decree signed by Vladimir Putin as acting President of Russia.[19] During the 2000 presidential elections, he was Putin's campaign manager. Putin won the election with 52.94% of the popular vote. Medvedev was quoted after the election commenting he thoroughly enjoyed the work and the responsibility calling it "a test of strength".[12]

As president, Putin launched a campaign against corrupt oligarchs and economic mismanagement. He appointed Medvedev chairman of gas company Gazprom's board of directors in 2000 with Alexei Miller. Medvedev put an end to the large-scale tax evasion and asset stripping by the previous corrupt management.[20] Medvedev then served as deputy chair from 2001 to 2002, becoming chair for the second time in June 2002,[11] a position which he held until his ascension to presidency in 2008.[21] During Medvedev's tenure, Gazprom's debts were restructured[22] and the company's market capitalisation grew from $7.8 billion[23] in 2000 to $300 billion in early 2008. Medvedev headed Russia's negotiations with Ukraine and Belarus during gas price disputes.[22]

In October 2003, Medvedev replaced Alexander Voloshin as presidential chief of staff. In November 2005, Medvedev moved from the presidential administration of the government when Putin appointed him as first deputy prime minister of Russia. In particular, Medvedev was made responsible for the implementation of the National Priority Projects focusing on improving public health, education, housing and agriculture. The program saw an increase of wages in healthcare and education and construction of new apartments but its funding, 4% of the federal budget, was not enough to significantly overhaul Russia's infrastructure. According to opinion polls, most Russians believed the money invested in the projects had been spent ineffectively.[12]

Presidential candidate

Following his appointment as first deputy prime minister, many political observers began to regard Medvedev as a potential candidate for the 2008 presidential elections,[24] although Western observers widely believed Medvedev was too liberal and too pro-Western for Putin to endorse him as a candidate. Instead, Western observers expected the candidate to arise from the ranks of the so-called siloviki, security and military officials many of whom were appointed to high positions during Putin's presidency.[12] The silovik Sergei Ivanov and the administrator-specialist Viktor Zubkov were seen as the strongest candidates.[25] In opinion polls which asked Russians to pick their favourite successor to Putin from a list of candidates not containing Putin himself, Medvedev often came out first, beating Ivanov and Zubkov as well as the opposition candidates.[26] In November 2006, Medvedev's trust rating was 17%, more than double than that of Ivanov. Medvedev's popularity was probably boosted by his high-profile role in the National Priority Projects.[27]

Many observers were surprised when on 10 December 2007, President Putin introduced Medvedev as his preferred successor. This was staged on TV with four parties suggesting Medvedev's candidature to Putin, and Putin then giving his endorsement. The four pro-Kremlin parties were United Russia, Fair Russia, Agrarian Party of Russia and Civilian Power.[25] United Russia held its party congress on 17 December 2007 where by secret ballot of the delegates, Medvedev was officially endorsed as their candidate in the 2008 presidential election.[28] He formally registered his candidacy with the Central Election Commission on 20 December 2007 and said he would step down as chairman of Gazprom, since under the current laws, the president is not permitted to hold another post.[29] His registration was formally accepted as valid by the Russian Central Election Commission on 21 January 2008.[30] Describing his reasons for endorsing Medvedev, Putin said:

I am confident that he will be a good president and an effective manager. But besides other things, there is this personal chemistry: I trust him. I just trust him.[12]

2008 presidential election

Election campaign

As 2 March 2008 election approached, the outgoing president, Vladimir Putin, remained the country's most popular politician. An opinion poll by Russia's independent polling organisation, the Levada Center,[31] conducted over the period 21–24 December 2007 indicated that when presented a list of potential candidates, 79% of Russians were ready to vote for Medvedev if the election was immediately held.[32][33][34] The other main contenders, the Communist Gennady Zyuganov and the LDPR's Vladimir Zhirinovsky both received in 9% in the same poll.[35][36] Much of Putin's popularity transferred to his chosen candidate, with 42% of the survey responders saying that Medvedev's strength came from Putin's support to him.[37][38]

In his first speech after being endorsed, Medvedev stated that, as president, he would appoint Vladimir Putin to the post of prime minister to head the Russian government.[39] Although constitutionally barred from a third consecutive presidential term, such a role would allow Putin to continue as an influential figure in Russian politics.[40] Putin pledged that he would accept the position of prime minister should Medvedev be elected president. Although Putin had pledged not to change the distribution of authority between the president and prime minister, many analysts expected a shift in the center of power from the presidency to the prime minister post when Putin assumed the latter under a Medvedev presidency.[41] Election posters portrayed the pair side by side with the slogan "Together We Win"[42] ("Вместе победим").[43] Medvedev vowed to work closely with Putin once elected.[44]

In December 2007, in preparation for his election campaign, Medvedev promised that funding of the National Priority Projects would be raised by 260 billion rubles for 2008. Medvedev's election campaign was relatively low-key and, like his predecessor, Medvedev refused to take part in televised debates, citing his high workload as first deputy prime minister as the reason. Instead, Medvedev preferred to present his views on his election website Medvedev2008.ru.[45]

In January 2008, Medvedev launched his campaign with stops in the oblasts.[46] On 22 January 2008, Medvedev held what was effectively his first campaign speech at Russia's second Civic Forum, advocating a liberal-conservative agenda for modernising Russia. Medvedev argued that Russia needed "decades of stable development" because the country had "exhausted its share of revolutions and social upheavals back in the twentieth century". Medvedev therefore emphasised liberal modernisation while still aiming to continue his predecessor's agenda of stabilisation.[47] On 15 February 2008, Medvedev held a keynote speech at the Fifth Krasnoyarsk Economic Forum, saying that:

Freedom is better than non-freedom – this principle should be at the core of our politics. I mean freedom in all its manifestations – personal freedom, economic freedom and, finally, freedom of expression.[47]

In the Krasnoyarsk speech, Medvedev harshly condemned Russia's "legal nihilism" and highlighted the need to ensure the independence of the country's judicial system and the need for an anti-corruption program. Economically, Medvedev advocated private property, economic deregulation and lower taxes. According to him, Russia's economy should be modernised by focusing on four "I"s: institutions, infrastructure, innovation and investment.[47][48][49]

Election win

Medvedev was elected President of Russia on 2 March 2008. The final election results gave him 70.28% (52,530,712) of votes with a turnout of 69.78% of registered voters. The main contenders, Gennady Zyuganov and Vladimir Zhirinovsky received 17.72% and 9.35% respectively. Three-quarters of Medvedev's vote was Putin's electorate. According to surveys, had Putin and Medvedev both run for president in the same elections, Medvedev would have received 9% of the vote.[50]

The fairness of the election was disputed by international observers. Andreas Gross, head of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) mission, stated that the elections were "neither free nor fair". Moreover, the few western vote monitors bemoaned the inequality of candidate registration and the abuse of administrative resources by Medvedev allowing blanket television coverage.[51] Russian programmer Shpilkin analysed the results of Medvedev's election and came to the conclusion that the results were falsified by the election committees. However, after the correction for the alleged falsification factor, Medvedev still came out as the winner although with 63% of the vote instead of 70%.[52]

Presidency (2008–12)

Inauguration

On 7 May 2008, Dmitry Medvedev took an oath as the third president of the Russian Federation in a ceremony held in the Grand Kremlin Palace.[53] After taking the oath of office and receiving a gold chain of double-headed eagles symbolising the presidency, he stated:[54]

I believe my most important aims will be to protect civil and economic freedoms... We must fight for a true respect of the law and overcome legal nihilism, which seriously hampers modern development.[54]

His inauguration coincided with the celebration of the Victory Day on 9 May. He attended the military parade at Red Square and signed a decree to provide housing to war veterans.[55]

Personnel appointments

On 8 May 2008, Dmitry Medvedev appointed Putin Prime Minister of Russia as he had promised during his election campaign. The nomination was approved by the State Duma with a clear majority of 392–56, with only Communist Party of the Russian Federation deputies voting against.[22]

12 May 2008, Putin proposed the list of names for his new cabinet which Medvedev approved.[56] Most of the personnel remained unchanged from the period of Putin's initial presidency but there were several high-profile changes. The Minister of Justice, Vladimir Ustinov was replaced by Aleksandr Konovalov; the Minister of Energy, Viktor Khristenko was replaced with Sergei Shmatko; the Minister of Communications, Leonid Reiman was replaced with Igor Shchyogolev and Vitaliy Mutko received the newly created position of Minister of Sports, Tourism and Youth policy.[22]

In the presidential administration, Medvedev replaced Sergei Sobyanin with Sergei Naryshkin as the head of the administration. The head of the Federal Security Service, Nikolai Patrushev, was replaced with Alexander Bortnikov.[22] Medvedev's economic adviser Arkady Dvorkovich and his press attaché Natalya Timakova became part of the president's core team. Medvedev's old classmate from his student years, Konstantin Chuichenko, became his personal assistant.[27]

Medvedev was reported to have taken care not to upset the balance of different factions in the presidential administration and in the government. However, the influence of the powerful security/military-related siloviki weakened after Medvedev's inauguration for the first time in 20 years. In their place, Medvedev brought in the so-called civiliki, a network of St. Petersburg civil law scholars preferred by Medvedev for high positions.[27][57]

"Tandem rule"

From the beginning of Medvedev's tenure, the nature of his presidency and his relationship with Putin was subject to considerable media speculation. In a unique situation in the Russian Federation's political history, the constitutionally powerful president was now flanked with a highly influential prime minister (Putin), who also remained the country's most popular politician. Previous prime ministers had proven to be almost completely subordinate to the president and none of them had enjoyed strong public approval, with Yevgeny Primakov and Putin's previous tenure (1999–2000) as prime minister under Boris Yeltsin being the only exceptions.[22] Journalists quickly dubbed the new system with a practically dual-headed executive as "government by tandem" or "tandemocracy", with Medvedev and Putin called the "ruling tandem".[12]

Daniel Treisman has argued that early in Medvedev's presidency, Putin seemed ready to disengage and started withdrawing to the background. In the first year of Medvedev's presidency, two external events threatening Russia—the late-2000s financial crisis and the 2008 South Ossetia war—changed Putin's plans and caused him to resume a stronger role in Russian politics.[12]

2008 Russo-Georgian War

The long-lingering conflict between Georgia and the separatist regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, which were supported by Russia, escalated during the summer of 2008.On 1 August 2008, the Russian-backed South Ossetian forces started shelling Georgian villages, with a sporadic response from Georgian peacekeepers in the area. Intensifying artillery attacks by the South Ossetians broke a 1992 ceasefire agreement. To put an end to these attacks, the Georgian army units were sent in to the South Ossetian conflict zone on 7 August. Georgian troops took control of most of Tskhinvali, a separatist stronghold, in hours.[58][59]

At the time of the attack, Medvedev was on vacation and Putin was attending the opening ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Olympics.[60] At about 1:00 a.m on 8 August, Medvedev held a telephone conversation with the Defence Minister, Anatoliy Serdyukov. It is likely that during this conversation, Medvedev authorised the use of force against Georgia.[61] The next day, Medvedev released a statement, in which he said:

Last night, Georgian troops committed what amounts to an act of aggression against Russian peacekeepers and the civilian population in South Ossetia ... In accordance with the Constitution and the federal laws, as President of the Russian Federation it is my duty to protect the lives and dignity of Russian citizens wherever they may be. It is these circumstances that dictate the steps we will take now. We will not allow the deaths of our fellow citizens to go unpunished. The perpetrators will receive the punishment they deserve.

— Dmitry Medvedev on 8 August 2008[62]

In the early hours of 8 August, Russian military forces launched a counter-offensive against Georgian troops. After five days of heavy fighting, all Georgian forces were routed from South Ossetia and Abkhazia. On 12 August, Medvedev ended the Russian military operation, entitled "Operation to force Georgia into peace". Later on the same day, a peace deal brokered by the French and EU president, Nicolas Sarkozy, was signed between the warring parties. On 26 August, after being unanimously passed by the State Duma, Medvedev signed a decree recognising South Ossetia and Abkhazia as independent states. The five-day conflict cost the lives of 48 Russian soldiers, including 10 peacekeepers, while the casualties for Georgia was 170 soldiers and 14 policemen.[63]

The Russian popular opinion of the military intervention was broadly positive, not just among the supporters of the government, but across the political spectrum.[64] Medvedev's popularity ratings soared by around 10 percentage points to over 70%,[65] due to what was seen as his effective handling of the war.[66]

Shortly in the aftermath of the conflict, Medvedev formulated a 5-point strategy of the Russian foreign policy, which has become known as the Medvedev Doctrine. On 30 September 2009, the European Union–sponsored Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on the Conflict in Georgia stated that, while preceded by months of mutual provocations, "open hostilities began with a large-scale Georgian military operation against the town of Tskhinvali and the surrounding areas, launched in the night of 7 to 8 August 2008."[67][68]

2008–09 economic crisis

In September 2008, Russia was hit by repercussions of the global financial crisis. Before this, Russian officials, such as the Finance Minister, Alexei Kudrin, had said they believed Russia would be safe, due to its stable macroeconomic situation and substantial reserves accumulated during the years of growth. Despite this, the recession proved to be the worst in the history of Russia, and the country's GDP fell by over 8% in 2009.[69] The government's response was to use over a trillion rubles (more than $40 billion U.S. Dollars) to help troubled banks,[70] and initiated a large-scale stimulus programme, lending $50 billion to struggling companies.[69][70] No major banks collapsed, and minor failures were handled in an effective way. The economic situation stabilised in 2009, but substantial growth did not resume until 2010. Medvedev's approval ratings declined during the crisis, dropping from 83% in September 2008 to 68% in April 2009, before recovering to 72% in October 2009 following improvements in the economy.[71][72]

According to some analysts, the economic crisis, together with the 2008 South Ossetia war, delayed Medvedev's liberal programme. Instead of launching the reforms, the government and the presidency had to focus their efforts on anti-crisis measures and handling the foreign policy implications of the war.[73][74]

Economy

In the economic sphere, Medvedev has launched a modernisation programme which aims at modernising Russia's economy and society, decreasing the country's dependency on oil and gas revenues and creating a diversified economy based on high technology and innovation.[75] The programme is based on the top 5 priorities for the country's technological development: efficient energy use; nuclear technology; information technology; medical technology and pharmaceuticals; and space technology in combination with telecommunications.[76]

In November 2010, on his annual speech to the Federal Assembly Medvedev stressed for greater privatisation of unneeded state assets both at the federal and regional level, and that Russia's regions must sell-off non-core assets to help fund post-crisis spending, following in the footsteps of the state's planned $32 billion 3-year asset sales. Medvedev said the money from privatisation should be used to help modernise the economy and the regions should be rewarded for finding their own sources of cash.[77][78]

Medvedev has named technological innovation one of the key priorities of his presidency. In May 2009, Medvedev established the Presidential Commission on Innovation, which he will personally chair every month. The commission comprises almost the entire Russian government and some of the best minds from academia and business.[79] Medvedev has also said that giant state corporations will inevitably be privatised, and although the state had increased its role in the economy in recent years, this should remain a temporary move.[80]

On 7 August 2009, Dmitry Medvedev instructed the prosecutor general, Yury Chayka, and the chief of the Audit Directorate of the Presidential Administration of Russia, Konstantin Chuychenko, to probe state corporations, a new highly privileged form of organisation earlier promoted by President Putin, to question their appropriateness.[81][82]

In June 2010, he visited the Twitter headquarters in Silicon Valley declaring a mission to bring more high-tech innovation and investment to the country.[83]

Police reform

Medvedev made reforming Russia's law enforcement one of his top agendas, the reason for which was a shooting started by a police officer in April 2009 in one of Moscow's supermarkets. Medvedev initiated the reform at the end of 2009, with a presidential decree issued on 24 December ordering the government to begin planning the reform. In early August 2010, a draft law was posted on the Internet at the address for public discussion. The new website received more than 2,000 comments within 24 hours.[84] Based on citizen feedback, several modifications to the draft were made. On 27 October 2010, President Medvedev submitted the draft to the lower house of the Russian parliament, the State Duma.[85] The State Duma voted to approve the bill on 28 January 2011, and the upper house, the Federation Council followed suit on 2 February 2011. On 7 February 2011, President Medvedev signed the bill into law.[86] The changes came into effect on 1 March 2011.[87]

Under the reform, the salaries of Russian police officers were increased by 30%, Interior Ministry personnel were cut and financing and jurisdiction over the police were centralised. Around 217 billion rubles ($7 billion) were allocated to the police reform from the federal budget for the time frame 2012–2013.[88]

Anti-corruption campaign

On 19 May 2008, Medvedev signed a decree on anti-corruption measures, which included creation of an Anti-Corruption Council.[89] In the first meeting of the council on 30 September 2008, Medvedev said:[90]

I will repeat one simple, but very painful thing. Corruption in our country has become rampant. It has become commonplace and characterises the life of the Russian society.

In July 2008, Medvedev's National Anti-Corruption Plan was published in the official Rossiyskaya Gazeta newspaper. It suggested measures aimed at making sanctions for corruption more severe, such as legislation to disqualify state and municipal officials who commit minor corruption offences and making it obligatory for officials to report corruption. The plan ordered the government to prepare anti-corruption legislation based on these suggestions.[91][92] The bill that followed, called On Corruption Counteraction was signed into law on 25 December 2008 as Federal Law N 273-FZ.[93] According to Professor Richard Sakwa, "Russia now at last had serious, if flawed, legislation against corruption, which in the context was quite an achievement, although preliminary results were meagre."[90] Russia's score in Corruption Perceptions Index rose from 2.1 in 2008 to 2.2 in 2009, which "could be interpreted as a mildly positive response to the newly adopted package of anti-corruption legislation initiated and promoted by president Medvedev and passed by the Duma in December 2008", according to Transparency International's CPI 2009 Regional Highlights report.[94]

On 13 April 2010, Medvedev signed presidential decree No. 460 which introduced the National Anti-Corruption Strategy, a midterm government policy, while the plan is updated every two years. The new strategy stipulated increased fines, greater public oversight of government budgets and sociological research.[95][96] According to Georgy Satarov, president of the Indem think tank, the latest decree "probably reflected Medvedev's frustration with the fact that the 2008 plan had yielded little result."[95]

In January 2011, President Medvedev admitted that the government had so far failed in its anti-corruption measures.[97]

On 4 May 2011, Medvedev signed the Federal Law On Amendments to the Criminal Code and the Code of Administrative Offences of the Russian Federation to Improve State Anti-Corruption Management.[98] The bill raised fines for corruption to up to 100 times the amount of the bribe given or received, with the maximum fine being 500 million rubles ($18.3 million).[99]

Education

President Medvedev initiated a new policy called "Our New School" and instructed the government to present a review on the implementation of the initiative every year.[100]

Development of the political system

Regional elections held on 1 March 2009 were followed by accusations of administrative resources being used in support of United Russia candidates, with the leader of A Just Russia, Sergey Mironov, being especially critical. Responding to this, Medvedev met with the chairman of the Central Election Commission of Russia, Vladimir Churov, and called for moderation in the use of administrative resources.[101] In August 2009, Medvedev promised to break the near-dominant position of United Russia party in national and regional legislatures, stating that "New democratic times are beginning".[102] The next regional elections were held on 11 October 2009 and won by United Russia with 66% of the vote. The elections were again harshly criticised for the use of administrative resources in favour of United Russia candidates. Communist, LDPR and A Just Russia parliamentary deputies staged an unprecedented walkout on 14–15 October 2009 as a result.[101] Although Medvedev often promised to stand up for more political pluralism, Professor Richard Sakwa observed, after the 2009 regional elections, a gulf formed between Medvedev's words and the worsening situation, with the question arising "whether Medvedev had the desire or ability to renew Russia's political system."[101]

On 26 October 2009, the First Deputy Chief of Staff, Vladislav Surkov, warned that democratic experiments could result in more instability and that more instability "could rip Russia apart".[103] On 6 November 2010, Medvedev vetoed a recently passed bill which restricted antigovernment demonstrations. The bill, passed on 22 October, prohibited anyone who had previously been convicted of organising an illegal mass rally from seeking permission to stage a demonstration.[104]

In late November 2010, Medvedev made a public statement about the damage being done to Russia's politics by the dominance of the United Russia party. He claimed that the country faced political stagnation if the ruling party would "degrade" if not challenged; "this stagnation is equally damaging to both the ruling party and the opposition forces." In the same speech, he said Russian democracy was "imperfect" but improving. BBC Russian correspondents reported that this came on the heels of discontent in political circles and opposition that the authorities, in their view, had too much control over the political process.[105]

In his first State of the Nation address to the Russian parliament on 5 November 2008,[106] Medvedev proposed to change the Constitution of Russia in order to increase the terms of the president and State Duma from four to six and five years respectively (see 2008 Amendments to the Constitution of Russia).

Medvedev on 8 May 2009, proposed to the legislature and on 2 June signed into law an amendment whereby the chairperson of the Constitutional Court and his deputies would be proposed to the parliament by the president rather than elected by the judges, as was the case before.[107]

In May 2009, Medvedev set up the Presidential Commission of the Russian Federation to Counter Attempts to Falsify History to the Detriment of Russia's Interests.[108] In August of the same year, he stated his opposition to the equating of Stalinism with Nazism. Medvedev denied the involvement of the Soviet Union in the Soviet invasion of Poland together with Nazi Germany. Arguments of the European Union and of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) were called a lie. Medvedev said it was Joseph Stalin who in fact "ultimately saved Europe".[109]

On 30 October 2009, due to the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Political Repressions, President Medvedev published a statement in his video blog. He stressed that the memory of national tragedies is as sacred as the memory of victory. Medvedev recalled that for twenty of the pre-war years entire layers and classes of the Russian people were destroyed (this period includes the Red Terror mainly under the lead of Felix Dzerzhinsky, the crimes of Joseph Stalin and other evil deeds of the Soviet Bolsheviks). Nothing can take precedence over the value of human life, said the president.[110]

In a speech on 15 September 2009, Medvedev stated that he approved of the abolition in 2004 of direct popular elections of regional leaders, effectively in favour of their appointment by the Kremlin, and added that he didn't see a possibility of a return to direct elections even in 100 years.[111][112]

Election law changes

In 2009, Medvedev proposed an amendment to the election law which would decrease the State Duma election threshold from 7% to 5%. The amendment was signed into law in Spring 2009. Parties receiving more than 5% but less than 6% of the votes would henceforward be guaranteed one seat, while parties receiving more than 6% but less than 7% will get two seats. These seats will be allocated before the seats for parties with over 7% support.[113]

Russian election law stipulates that parties with representatives in the State Duma are free to put forward a list of candidates for the Duma elections, while parties with no current representation need first to collect signatures. Under the 2009 amendments initiated by Medvedev, the number of signatures required was lowered from 200,000 to 150,000 for the 2011 Duma elections. In subsequent elections, only 120,000 signatures will be required.[113]

Foreign policy

In August, during the third month of Medvedev's presidency, Russia took part in the 2008 South Ossetia war with Georgia, which drove tension in Russia–United States relations to a post–Cold War high. On 26 August, following a unanimous vote of the Federal Assembly of Russia, Medvedev issued a presidential decree officially recognising Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states,[116] an action condemned by the G8.[117] On 31 August 2008, Medvedev shifted Russia's foreign policy under his government, built around five main principles:[118]

- Fundamental principles of international law are supreme.

- The world will be multipolar.

- Russia will not seek confrontation with other nations.

- Russia will protect its citizens wherever they are.

- Russia will develop ties in friendly regions.

.jpg.webp)

In his address to the parliament on 5 November 2008 he also promised to deploy the Iskander missile system and radar-jamming facilities in Kaliningrad Oblast to counter the U.S. missile defence system in Eastern Europe.[119] Following U.S. President Barack Obama's 17 September 2009 decision to not deploy missile-defense elements in the Czech Republic and Poland, Dmitry Medvedev said he decided against deploying Iskander missiles in Russia's Kaliningrad Oblast.[120]

On 21 November 2011, Medvedev claimed that the war on Georgia had prevented further NATO expansion.[121]

In 2011, during the performance at the Yaroslavl Global Policy Forum, President Medvedev has declared that the doctrine of Karl Marx on class struggle is extremist and dangerous. Progressive economic stratification which can be less evident in period of economic growth, leads to acute conflicts between rich and poor people in period of downturn. In such conditions, the doctrine on class struggle is being revived in many regions of the world, riots and terrorist attacks become reality, by opinion of Medvedev.[122]

In August 2014, President Barack Obama said: "We had a very productive relationship with President Medvedev. We got a lot of things done that we needed to get done."[123]

During the official visit to Armenia on 7 April 2016, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev visited the Tsitsernakaberd Memorial Complex to pay tribute to the victims of the Armenian genocide. Medvedev laid flowers at the Eternal Fire and honoured the memory of the victims with a minute of silence. Russia recognised the crime in 1995.[124]

Relationship with Putin

Although the Russian constitution clearly apportions the greater power in the state to the president, speculation arose over the question of whether it was Medvedev or Prime Minister Vladimir Putin who actually wielded the most power.[125] According to London Daily Telegraph, "Kremlin-watchers" note that Medvedev uses the more formal form of 'you' (Вы, 'vy') when addressing Putin, while Putin addresses Medvedev with the less formal 'ty' (ты).[125]

According to a poll conducted in September 2009 by the Levada Center in which 1,600 Russians took part, 13% believed Medvedev held the most power, 32% believed Putin held the most power, 48% believed that the two shared equal levels of influence, and 7% failed to answer.[126] However, Medvedev attempted to affirm his position by stating, "I am the leader of this state, I am the head of this state, and the division of power is based on this."[127]

2012 presidential elections

As both Putin and Medvedev could have run for president in the 2012 general elections, there was a view from some analysts that some of Medvedev's contemporaneous actions and comments at the time were designed to separate his image from Putin's. BBC News suggested these might include his dealings in late 2010 with NATO and the United States, possibly designed to show himself as being better able to deal with Western nations,[128] and comments in November about the need for a stronger opposition in Russian politics, to present himself as a moderniser. BBC News observed other analysts considered the split to be exaggerated, that Medvedev and Putin were "trying to maximise support for the authorities by appealing to different parts of society".[105] There was belief that the court verdict on former oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky and his partner Platon Lebedev, both of whom funded opposition parties before their arrests, would indicate whether or not Putin was "still calling all the shots".[129]

On 24 September 2011, while speaking at the United Russia party congress, Medvedev recommended Vladimir Putin as the party's presidential candidate and revealed that the two men had long ago cut a deal to allow Putin to return to the presidency in 2012 after he was forced to stand down in 2008 by term limits.[130] This switch was termed by many in the media as "rokirovka", the Russian term for the chess move "castling". Medvedev said he himself would be ready to perform "practical work in the government".[131] Putin accepted Medvedev's offer the same day, and backed him for the position of the prime minister of Russia in case the United Russia, whose list of candidates in the elections Medvedev agreed to head, were to win in the upcoming Russian legislative election.[132] The same day, the Russian Orthodox Church endorsed the proposal by President Medvedev to let Putin return to the post of president of Russia.[133]

On 22 December 2011, in his last state of the nation address in Moscow, Medvedev called for comprehensive reform of Russia's political system — including restoring the election of regional governors and allowing half the seats in the State Duma to be directly elected in the regions. "I want to say that I hear those who talk about the need for change, and understand them", Medvedev said in an address to the Duma. "We need to give all active citizens the legal chance to participate in political life." However, the opposition to the ruling United Russia party of Medvedev and Prime Minister Putin dismissed the proposals as political posturing that failed to adequately address protesters who claimed 4 December election was rigged.[134] On 7 May, on his last day in office, Medvedev signed the last documents as the head of state: in the sphere of civil society, protection of human rights and modernisation. He approved the list of instructions by the results of the meeting with the presidential council on civil society and human rights, which was held on 28 April. Medvedev also approved with his decree "Presidential programme for raising skills of engineers for 2012–2014" for modernisation and technological development of the Russian economy.[135]

Prime minister (2012–2020)

First term

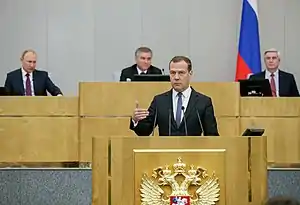

On 7 May 2012, the same day he ceased to be the president of Russia, Dmitry Medvedev was nominated by President Vladimir Putin to the office of prime minister.[136][137] On 8 May 2012, the State Duma of the Russian Federation voted on the nomination submitted by the new president, and confirmed the choice of Medvedev to the post. Putin's United Russia party, now led by Medvedev, secured a majority of the Duma's seats in the 2011 legislative election, winning 49% of the vote, and 238 of the 450 seats. Medvedev's nomination to the office of prime minister was approved by the State Duma in a 299–144 vote.[138]

First year

.jpg.webp)

Medvedev took office as prime minister of Russia also on 8 May 2012, after President Vladimir Putin signed the decree formalising his appointment to the office.[139]

On 19 May 2012, Dmitry Medvedev took part in the G-8 Summit at Camp David, in the United States, replacing President Putin, who decided not to represent Russia in the summit. Medvedev was the first prime minister to represent Russia at a G-8 meeting. On 21 May 2012, his Cabinet was appointed and approved by the president. On 26 May, he was approved and officially appointed as the chairman of United Russia, the ruling party. Earlier in the same week Medvedev was officially joined the party and thereby became Russia's first prime minister affiliated to a political party.[140]

Crimea

In the wake of the 2014 Ukrainian revolution, Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula. On 31 March 2014, Medvedev visited Crimea after the peninsula became part of Russia on 18 March. During his visit he announced the formation of the Federal Ministry for Crimea Affairs.[141]

Second term

On 7 May 2018, Dmitry Medvedev was nominated as prime minister by Vladimir Putin for another term.[142] On 8 May, Medvedev was confirmed by the State Duma as prime minister, with 374 votes in favour.[143] On 15 May, Putin approved the structure and on 18 May the composition of the Cabinet.[144][145]

In March 2017, discontentment was triggered through Medvedev's depiction in an investigative film by the Anti-Corruption Foundation titled He Is Not Dimon to You. This sparked demonstrations in central Moscow, with the crowd chanting "Medvedev, resign!" as well as "Putin is a thief!"[146] In the summer of 2018, country-wide protests took place against the retirement age hike introduced by Medvedev's government. The plan was unexpectedly announced by the government on 14 June, which coincided with the opening day of the 2018 FIFA World Cup hosted by Russia.[147] As a result of the demonstrations, the ratings of Medvedev as well as President Putin significantly declined. Following the 2019 Siberia wildfires, Medvedev proposed revising regulatory acts on extinguishing fires in regions, and instructed to consult with foreign experts in developing proposals to fight with wildfires.[148]

Resignation

Medvedev, along with his entire Cabinet resigned on 15 January 2020, after Putin delivered the Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly, in which he proposed several amendments to the constitution. Medvedev stated that he was resigning to allow President Putin to make the significant constitutional changes suggested by Putin regarding shifting power away from the presidency.[149] Medvedev said that the constitutional changes would "significantly change Russia's balance of power".[150][151] Putin accepted the resignation.[152]

Although Medvedev had ostensibly resigned voluntarily (part 1 of Article 117 of the constitution),[153][154] the Executive Order that was released stated that Putin had dismissed the cabinet as per Article 83 (c) and part 2 of Article 117 of the constitution.[155][156] Kommersant reported that the use of these sections revealed that it was Putin who had sacked Medvedev and that the resignation was not voluntary but forced, since these sections give power to the president to dissolve the government without explanation or motivation.[157]

Putin suggested that Medvedev take the post of deputy chairman of the Security Council.[151]

Deputy chairman of the Security Council (2020–present)

On 16 January 2020, Medvedev was appointed to the post of deputy chairman of the Security Council of Russia.[158] His salary was set at 618,713 rubles (8,723.85 USD).[159] In a July interview with Komsomolskaya Pravda, Medvedev said he retains "good friendly relations" with President Putin, which was in contrast with the opinion of many circles that his departure from the role of prime minister was a result of a rift in the domestic policies of both men.[160]

In February 2022, after Russia was suspended from the Council of Europe due to its invasion of Ukraine, and subsequently announced its intention to withdraw from the organization, Medvedev stated that while the decision to suspend Russia was "unfair", it was also a "good opportunity" to reinstate the death penalty in Russia.[161][162] He also stated that Russia didn't need diplomatic relations with the West and that the sanctions imposed on the country gave it good reason to pull out of dialogue on nuclear stability and potentially New START.[163]

In response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, on 6 April 2022 the Office of Foreign Assets Control of the United States Department of the Treasury added Medvedev to its list of persons sanctioned pursuant to Executive Order 14024.[164]

On 6 July 2022, Medvedev wrote on Telegram that it would be "crazy to create tribunals or courts for the so-called investigation of Russia’s actions", claiming the idea of "punishing a country that has one of the largest nuclear potentials" may potentially pose "a threat to the existence of humanity." Medvedev accused the United States of creating "chaos and devastation around the world under the guise of ‘true democracy’", concluding his message by saying "the US and its useless stooges should remember the words of the Bible: ‘Judge not, lest you be judged; so that one day the great day of His wrath will not come to their house, and who can stand?’"[165]

On 27 July 2022, Medvedev shared a map on Telegram, described as predictions of "Western analysts", showing Ukraine, including its occupied territories, mostly absorbed by Russia, as well as Poland, Romania and Hungary.[166][167]

Medvedev was interviewed at length by Darius Rochebin of French TV broadcaster La Chaîne Info on 27 August 2022.[168]

In late 2022 Medvedev said that any weapons in Russia's arsenal, including strategic nuclear weapons, could be used to protect territories annexed to Russia from Ukraine. He also said that referendums organized by Russia-installed and separatist authorities would take place in large swathes of Russian-occupied Ukrainian territory, and that there was "no turning back".[169][170]

Personal life

Medvedev is married and has a son named Ilya Dmitrevich Medvedev (born 1995). His wife, Svetlana Vladimirovna Medvedeva, was both his childhood friend and school sweetheart. They married several years after their graduation from secondary school in 1982.[171]

Medvedev is a fan of British hard rock, listing Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, Pink Floyd, and Deep Purple as his favourite bands. He is a collector of their original vinyl records and has previously said that he has collected all of the recordings of Deep Purple.[172][173] As a youth, he made copies of their records, even though these bands were then on the official state-issued blacklist.[174] In February 2008, Medvedev and Sergei Ivanov attended a Deep Purple concert in Moscow together.[175]

During a visit to Serbia, Medvedev received the highest award of the Serbian Orthodox Church, the Order of St. Sava, for "his contribution to the unity of the world Orthodoxy and his love to the Serbian people."[176]

Medvedev always reserves an hour each morning and again each evening to swim[173] and weight train. He swims 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) twice a day. He also jogs, plays chess, and practices yoga. Among his hobbies are reading the works of Mikhail Bulgakov and he is also a fan of the Harry Potter series after asking J. K. Rowling for her autograph when they met during the G-20 London Summit in April 2009.[177] He is also a fan of football and follows his hometown professional football team, FC Zenit Saint Petersburg.[178]

Medvedev is an avid amateur photographer. In January 2010, one of his photographs was sold at a charity auction for 51 million rubles (US$1,750,000), making it one of the most expensive ever sold.[179] The photo was purchased by Mikhail Zingarevich, a co-founder and member of the board of directors of the Ilim Group at which Medvedev worked as a lawyer in the 90s.[180]

Medvedev's reported 2007 annual income was $80,000, and he reported approximately the same amount as bank savings. Medvedev's wife reported no savings or income. They live in an upscale apartment house "Zolotye Klyuchi" in Moscow.[181] Despite this supposedly modest income, a video by anti-corruption activist Alexei Navalny[182] purports to show "the vast trove of mansions, villas and vineyards accumulated" by Medvedev.[183]

On the Russian-language Internet, Medvedev is sometimes associated with the Medved meme, linked to padonki slang, which resulted in many ironic and satirical writings and cartoons that blend Medvedev with a bear. (The word medved means "bear" in Russian and the surname "Medvedev" is a patronymic which means "of the bears".) Medvedev is familiar with this phenomenon and takes no offence, stating that the web meme has the right to exist.[184][185][186][187]

Medvedev speaks English, in addition to his native Russian,[188] but during interviews he speaks only Russian.[189]

Corruption allegations

_12.jpg.webp)

In September 2016, opposition leader Alexei Navalny published a report with information about Dmitry Medvedev's alleged summer residence ("dacha") – an 80 hectare estate with plethora of houses, a ski run, a cascading swimming pool, three helipads and purpose-built communications towers. The estate even includes a house for ducks, which received public ridicule and led to ducks becoming a protest symbol in Russia a year later.[190] The area is surrounded by a six-foot (1.82 meter) fence and is allegedly 30 times the size of Red Square, the iconic square in Moscow.[191] This summer residence is an expensively renovated 18th century manor called Milovka Estate and located in Plyos on the shore of Volga River.[192]

In March 2017, Navalny and the Anti-Corruption Foundation published another in-depth investigation of properties and residences used by Medvedev and his family. A report called He Is Not Dimon To You shows how Medvedev allegedly owns and controls large areas of land, villas, palaces, yachts, expensive apartments, wineries and estates through complicated ownership structures involving shell companies and foundations.[193] Their total value is estimated at around US$1.2 billion. The report states that the original source of wealth is gifts by Russian oligarchs and loans from state owned banks. An hour long YouTube video in Russian was released together with the report. A month after release, the video had more than 24 million views.[194] Medvedev dismissed the allegations, calling them "nonsense".[195] These revelations have resulted in large protests throughout Russia. Russian authorities responded by arresting protesters in unauthorised protests—hundreds were arrested including Alexei Navalny, which the government called "an illegal provocation".[196] An April 2017 Levada poll found that 45% of surveyed Russians supported the resignation of Medvedev.[197]

Publications

Medvedev wrote two short articles on the subject of his doctoral dissertation in Russian law journals. He is also one of the authors of a textbook on civil law for universities first published in 1991 (the 6th edition of Civil Law. In 3 Volumes. was published in 2007). He is the author of a university textbook, Questions of Russia's National Development, first published in 2007, concerning the role of the Russian state in social policy and economic development. He is also the lead co-author of a book of legal commentary entitled, A Commentary on the Federal Law "On the State Civil Service of the Russian Federation". This work considers the Russian Federal law on the civil service,[198] which went into effect on 27 July 2004, from multiple perspectives — scholarly, jurisprudential, practical, enforcement- and implementation-related.[199]

In October 2008, President Medvedev delivered the first podcast at the presidential website.[200] His videoblog posts have also been posted in the official LiveJournal community blog_medvedev[201]

On 23 June 2011, Medvedev participated in launching of the "Eternal Values" project of RIA Novosti state-operated news agency together with Russian chapter of Wikimedia Foundation. RIA Novosti granted free Creative Commons licences to one hundred of its images, while Medvedev registered as Dmitry Medvedev for RIAN and personally uploaded one of those photographs to Wikimedia Commons.[202][203]

On 13 April 2009, Medvedev gave a major interview to the Novaya Gazeta newspaper. The interview was the first one he had ever given to a Russian print publication and covered such issues as civil society and the social contract, transparency of public officials and Internet development.[204][205]

- Medvedev, Dmitry (2012). President Dmitry Medvedev. Photo book.

Electoral history

Presidential election

| 2008 presidential election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidates | Party | Votes | % | |

| Dmitry Medvedev | United Russia | 52,530,712 | 71.2 | |

| Gennady Zyuganov | Communist Party | 13,243,550 | 18.0 | |

| Vladimir Zhirinovsky | Liberal Democratic Party | 6,988,510 | 9.5 | |

| Andrei Bogdanov | Democratic Party | 968,344 | 1.3 | |

| Source: Результаты выборов | ||||

Prime minister nominations

| 2012 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For | Against | Abstaining | Did not vote | ||||

| 299 | 66.4% | 144 | 32.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 7 | 1.6% |

| Source: Справка о результатах голосования | |||||||

| 2018 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For | Against | Abstaining | Did not vote | ||||

| 374 | 83.9% | 56 | 12.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 16 | 1.6% |

| Source: Справка о результатах голосования | |||||||

References

- First Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev Endorsed for the Next President's Post , Voice of Ruddia, 10 December 2007.

- "Security Council structure". en.kremlin.ru/. Archived from the original on 18 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- "Medvedev Announces Russian Government's Resignation". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Archived from the original on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- "Подписан Указ о Заместителе Председателя Совета Безопасности Российской Федерации: Владимир Путин подписал Указ "О Заместителе Председателя Совета Безопасности Российской Федерации"". kremlin.ru. 16 January 2020. Archived from the original on 17 January 2020. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- The Guardian

- Reuters

- RFE/RL

- Медведев Дмитрий Анатольевич Archived 9 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine Viperson.ru

- Потомок пахарей и хлеборобов Archived 12 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine Ekspress Gazeta 4 April 2008

- "Transcript interview, First Deputy Chairman of the Government of the Russian Federation Dmitry Medvedev" (in Russian). Government of the Russian Federation. 24 January 2008. Archived from the original on 6 July 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2008.

- "Dmitry Medvedev: Biography". Kremlin.ru. 2008. Archived from the original on 25 March 2011.

- Treisman, Daniel (2011). The Return: Russia's Journey from Gorbachev to Medvedev. Free Press. pp. 123–163. ISBN 978-1-4165-6071-5.

- "Дмитрий Медведев – личный сайт". medvedev.kremlin.ru. 3 September 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- Andreyev, Sergey. "Почему Медведев?". Archived from the original on 11 August 2010.

- "Спортивная биография Дмитрия Медведева: гребля, йога и штанга". NEWSru.com (in Russian). 20 December 2007. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- "FACTBOX: Key facts on Russia's Dmitry Medvedev". Reuters. 24 February 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- Umland, Andreas (11 December 2007). "The Democratic Roots of Putin's Choice". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2008.

- Levy, Clifford J.; p. A18

- "О присвоении квалификационного разряда федеральным государственным служащим Администрации Президента Российской Федерации". Decree No. 59 of 17 January 2000 (in Russian). President of Russia.

- Goldmann, Marshall (2008). Petrostate: Putin, Power and the New Russia. Oxford University Press. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-0-19-534073-0.

- "Zubkov replaces Medvedev as Gazprom chairman". The New York Times. 27 June 2008. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- Willerton, John (2010). "Semi-presidentialism and the evolving executive". In White, Stephen (ed.). Developments in Russian Politics. Vol. 7. Duke University Press. ISBN 9780230224490.

- "Shares". Gazprom. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- Russia: President's Potential Successor Debuts At Davos Archived 9 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine. 31 January 2007.

- Дмитрий Медведев выдвинут в президенты России. Lenta.Ru (in Russian). 10 December 2007. Archived from the original on 25 December 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- Treisman, Daniel (2011). The Return: Russia's Journey from Gorbachev to Medvedev. Free Press. pp. 240–261. ISBN 978-1-4165-6071-5.

- Sakwa, Richard (2011). The Crisis of Russian Democracy: Dual State, Factionalism and the Medvedev Succession. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-14522-0.

- United Russia endorses D Medvedev as candidate for presidency Archived 4 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine ITAR-TASS, 17 December 2007.

- Medvedev Registers for Russian Presidency, Will Leave Gazprom, Bloomberg, 20 December 2007.

- (in Russian) О регистрации Дмитрия Анатольевича Медведева кандидатом на должность Президента Российской Федерации Archived 5 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Decision No. 88/688-5 of the Central Election Commission of the Russian Federation, 21 January 2008.

- Yuri Levada Archived 9 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine, The Times, 21 November 2006.

- 27.12.2007. Последние президентские рейтинги 2007 года Archived 16 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine, The Levada Center, 27 December 2007. (In the same poll, when presented with the question of who they would vote for without a list of potential candidates, only 55% of those polled volunteered that they would vote for Medvedev, but another 24% said that they would vote for Putin. Putin is constitutionally ineligible for a consecutive presidential term.)

- Poll says Putin's protégé more popular than president Archived 9 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Russian News & Information Agency, 27 December 2007.

- Putin's Chosen Successor, Medevedev, Starts Campaign (Update2) Archived 16 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Bloomberg.com, 11 January 2008.

- Sakwa 2011, p.282

- Последние президентские рейтинги 2007 года Archived 16 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine Ledada Center, 27 December 2007

- Medvedev's Strength Is Putin: Poll Archived 5 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine The Moscow Times, 16 January 2008.

- Sakwa 2011, p. 275

- Speech by Dmitry A. Medvedev Archived 24 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 11 December 2007

- Drive Starts to Make Putin 'National Leader' Archived 22 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine The Moscow Times, 8 November 2007

- Putin seeks prime minister's post Associated Press, 17 December 2007.

- "Moscow Times". webcache.googleusercontent.com. Archived from the original on 13 August 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- "World | Europe | Profile: Dmitry Medvedev". BBC News. 7 May 2008. Archived from the original on 23 May 2009. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- "New Russian president: I will work with Putin=CNN". Archived from the original on 5 March 2008. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- Sakwa 2011, pp.282–283

- Putin's successor dismisses fears of state "grab" Archived 21 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, 17 January 2008.

- Sakwa 2011, p.287

- "Foreign investors expect reforms from Russia's Medvedev".

- Flintoff, Corey (4 March 2008). "Focus Shifts to How Medvedev Will Run Russia". NPR. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- Sakwa 2011, pp.284–275

- "Europe Offers Congratulations and Criticism to Medvedev". Deutsche Welle. 3 March 2008. Archived from the original on 27 May 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2009.

- Dmitri Medvedev votes were rigged, says computer boffin Archived 3 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine The Times 18 April 2008

- "ABC Live". Abclive.in. Archived from the original on 27 May 2009. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- Stott, Michael (7 May 2008). "www.reuters.com, Russia's Medvedev takes power, pledges freedom". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 May 2009. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- "Medvedev decrees to provide housing to war veterans" Archived 22 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine – ITAR-TASS, 7 May 2008, 15.27

- "Prime Minister Putin appoints new government – 2". RIA Novosti. 12 May 2008. Archived from the original on 9 August 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- "All the Next President's Men". Russia Profile. 19 December 2007. Archived from the original on 4 August 2011.

- "EU report, volume II" (PDF). Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on the Conflict in Georgia. 30 September 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- Nicoll, Alexander; Sarah Johnstone (September 2008). "Russia's rapid reaction". International Institute for Strategic Studies. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- China still on-side with Russia Asia Times, 6 September 2008

- Lavrov, Anton (2010). Ruslan Pukhov (ed.). The Tanks of August. Centre for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies. p. 49. ISBN 978-5-9902320-1-3.

- Statement on the Situation in South Ossetia Archived 16 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine Website of the President of Russia, 8 August 2008.

- Treisman, p.153

- Treisman, p.154

- Treisman, p.259

- Sakwa 2011, p.343

- "Georgia 'started unjustified war'". BBC News. 30 September 2009. Archived from the original on 20 April 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- "EU Report: Independent Experts Blame Georgia for South Ossetia War". Der Spiegel. 21 September 2009. Archived from the original on 2 September 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- Guriev, Sergei; Tsyvinski, Aleh (2010). "Challenges Facing the Russian Economy after the Crisis". In Anders Åslund; Sergei Guriev; Andrew C. Kuchins (eds.). Russia After the Global Economic Crisis. Peterson Institute for International Economics; Centre for Strategic and International Studies; New Economic School. pp. 9–39. ISBN 978-0-88132-497-6.

- Treisman, p.149

- "President's performance in office — Trends". Levada Center. May 2011. Archived from the original on 11 March 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- Treisman, Daniel (2010). "Russian Politics in a Time of Turmoil". In Anders Åslund; Sergei Guriev; Andrew C. Kuchins (eds.). Russia After the Global Economic Crisis. Peterson Institute for International Economics; Centre for Strategic and International Studies; New Economic School. pp. 39–59. ISBN 978-0-88132-497-6.

- Treisman, p.155

- "Dmitry Medvedev's three years in office: achievements, results and influence". RIA Novosti. 11 May 2011. Archived from the original on 9 August 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- "Russia Profile Weekly Experts Panel: 2009 – Russia's Year in Review". Russia Profile. 31 December 2009. Archived from the original on 19 January 2011.

- Presidential Commission on the modernisation and technological development of the Russian economy Archived 11 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine Official site. (in Russian)

- Dyomkin, Denis (2010). "Russia tells regions to join privatization drive". Reuters.

- "Privatization in regions to yield tens of billions of rbls-Kremlin". Itar-tass.com. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- "Russia Profile Weekly Experts Panel: Medvedev's Quest for Innovation". Russia Profile. 5 June 2009. Archived from the original on 11 August 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- "Medvedev says giant state corporations to go private". RIA Novosti. 5 June 2009. Archived from the original on 9 August 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- "Ъ-Online – Генпрокуратура приступила к проверке госкорпораций". Kommersant.ru. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- "Medvedev orders look at activity of Russian state-run businesses | Russia | RIA Novosti". En.rian.ru. 7 August 2009. Archived from the original on 9 August 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- "Dmitry Medvedev visits Twitter HQ and tweets" Archived 19 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Telegraph. 24 June 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2011

- "Russia Profile Weekly Experts Panel: Will Police Reform Result in Name Change Only?". Russia Profile. 27 August 2010. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011.

- "Medvedev submits draft police law to Russian lower house". RIA Novosti. 27 October 2010. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011.

- "Medvedev signs police reform bill into law". RIA Novosti. 7 February 2011. Archived from the original on 9 August 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- "Will Russian police reforms be more than a name change?". RIA Novosti. 18 March 2011. Archived from the original on 9 August 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- "Russia to spend around $7 billion on police reform in 2012–2013". RIA Novosti. 9 September 2010. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011.

- Medvedev signs decree on measures to counter corruption Archived 9 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine RIA Novosti 19 May 2008

- Sakwa 2011, p.329

- Medvedev's Anti-Corruption Crusade Archived 12 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine Russia Profile, 8 July 2008

- National Anti-Corruption Plan Archived 16 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine Website of the President of Russia, 31 July 2008.

- The Russian Federation Federal Law On Corruption Counteraction, 25 December 2008, N 273-FZ Archived 16 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine Website of President Of Russia

- Grafting the Future Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine Russia Profile, 29 November 2009

- Nikolaus von Twickel (16 April 2010). "Medvedev Redefines Anti-Corruption Drive". The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- National Anti-Corruption Strategy (Approved by Decree of the President of the Russian Federation №460 of 13 April 2010) Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine Website of the President of Russia.

- Russian president admits failure in fighting corruption Archived 22 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine Xianhuanet 13 January 2011

- Amendments to bolster anti-corruption legislation Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine Website of the President of Russia

- Medvedev signs landmark anti-corruption law Archived 9 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine RIA Novosti 3 May 2011

- Itar Tass, "Pres to launch education modernization project in few days"

- Sakwa 2011, p.327

- Polls show Russians back crisis plan: Putin's party Archived 1 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine Reuters, 12 October 2009

- Kremlin warns against wrecking Russia with democracy Archived 30 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Kyiv Post (26 October 2009)

- "Medvedev vetoes law restricting protests: Kremlin | Russian News | Expatica Moscow". www.expatica.com. 6 November 2010. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- Steve Rosenberg (24 November 2010). "Medvedev warns of political 'stagnation' in Russia". BBC. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- "Full text in English". Kremlin.ru. Archived from the original on 31 August 2009. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- "Itar-Tass". Itar-Tass. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- Andrew Osborn. Medvedev Creates History Commission Archived 23 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Wall Street Journal, 21 May 2009.

- The war? Nothing to do with Stalin, says Russia's president, Dmitry Medvedev Archived 17 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine (30 August 2009)

- Д. Медведев: Нельзя оправдывать тех, кто уничтожал свой народ Archived 27 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine (30 окт, 2009)

- "St. Petersburg Times". Times.spb.ru. 18 September 2009. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- "No change to method of appointing regional governors – Medvedev | Valdai Club | RIA Novosti". En.rian.ru. 15 September 2009. Archived from the original on 9 August 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- "How the Duma electoral system works". Levada Center. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- "Burger Time for President's Obama and Medvedev". YouTube.com. Associated Press, USA. 25 June 2010. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- "The Obamas and The Medvedevs Dine Together". YouTube.com. WestEndNews. 13 November 2012. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- Russia recognises Georgian rebels Archived 17 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, 26 August 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- Russia faces fresh condemnation Archived 28 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, 27 August 2008. Retrieved 29 August 2008.

- "Medvedev outlines five main points of future foreign policy". En.rian.ru. 31 August 2008. Archived from the original on 12 September 2008. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- Steve Gutterman and Vladimir Isachenkov. Medvedev: Russia to deploy missiles near Poland, Associated Press, 5 November 2008.

- Russia never placed Iskander missiles in Kaliningrad – Navy chief Archived 19 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, RIA Novosti, 1 October 2009.

- "Russia's 2008 war with Georgia prevented NATO growth – Medvedev." Archived 18 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine RIA Novosti, 21 November 2011.

- Д. Медведев назвал учение Маркса экстремистским (08.09.2011)

- "The president on dealing with Russia". The Economist. 2 August 2014. Archived from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- "RF Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev Pays Tribute to Armenian Genocide Victims" Archived 21 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine (Thursday, 7 April 2016)

- Osborn, Andrew (7 March 2010). "Dmitry Medvedev's Russia still feels the cold hand of Vladimir Putin, Telegraph". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- Poll: Medvedev and Putin: who holds the power? Archived 16 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Levada Center Retrieved on 12 March 2010

- "Medvedev insists he's the boss". Television New Zealand. 30 March 2009. Archived from the original on 19 September 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Russia 'to work with Nato on missile defence shield'". BBC News. 20 November 2010. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- Ostalski, Andrei (15 December 2010). "Russia's most important court trial". BBC News. Archived from the original on 4 December 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- Osborn, Andrew (24 September 2011). "Vladimir Putin on course to be Russia's next president as Dmitry Medvedev steps aside". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- "Medvedev backs Putin for Russian president". RIA Novosti. 24 September 2011. Archived from the original on 9 August 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- "Russia's Putin set to return as president in 2012". BBC News. 24 September 2011. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- "Церковь одобрила решение Путина вернуться на пост президента России". Gazeta.ru. 24 September 2011. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- "Russia's Medvedev tries to appease protesters". Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- (in Russian) "Putin signs first decree as president", Itar Tass, 7 May 2012 Archived 14 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Itar-tass.com. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- Putin returns as Russia's president amid protests – CNN.com Archived 22 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Edition.cnn.com (7 May 2012). Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- Putin Proposes Medvedev As Russian Prime Minister Archived 30 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Rttnews.com (7 May 2012). Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- Putin hands Medvedev prime minister role amidst sustained unrest Archived 22 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The Globe and Mail (8 May 2012). Retrieved 10 May 2012.