Doom (1993 video game)

Doom is a 1993 first-person shooter (FPS) game developed by id Software for MS-DOS. Players assume the role of a space marine, popularly known as Doomguy, fighting their way through hordes of invading demons from hell. Id began developing Doom after the release of their previous FPS, Wolfenstein 3D (1992). It emerged from a 3D game engine developed by John Carmack, who wanted to create a science fiction game inspired by Dungeons & Dragons and the films Evil Dead II and Aliens. The first episode, comprising nine levels, was distributed freely as shareware; the full game, with two further episodes, was sold via mail order. An updated version with an additional episode and more difficult levels, The Ultimate Doom, was released in 1995 and sold at retail.

| Doom | |

|---|---|

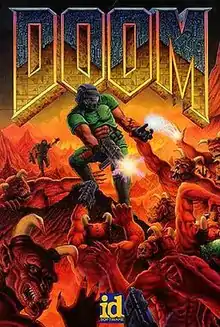

Cover art by Don Ivan Punchatz showing the Doomguy killing a horde of Demons | |

| Developer(s) | id Software |

| Publisher(s) | id Software |

| Designer(s) |

|

| Programmer(s) |

|

| Artist(s) |

|

| Composer(s) | Robert Prince |

| Series | Doom |

| Engine | Doom engine[lower-alpha 1] |

| Platform(s) |

|

| Release | December 10, 1993

|

| Genre(s) | First-person shooter |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

Doom is one of the most significant games in video game history, frequently cited as one of the greatest games ever made. It sold an estimated 3.5 million copies by 1999; between 10 and 20 million people are estimated to have played it within two years of launch, and in late 1995, it was estimated to be installed on more computers worldwide than Microsoft's new operating system, Windows 95. Along with Wolfenstein 3D, Doom helped define the FPS genre and inspired numerous similar games, often called Doom clones. It pioneered online distribution and technologies including 3D graphics, networked multiplayer gaming, and support for custom modifications via packaged WAD files. Its graphic violence and supposed hellish imagery drew controversy.

Doom has been ported to numerous platforms. The Doom franchise continued with Doom II: Hell on Earth (1994) and expansion packs including Master Levels for Doom II (1995). The source code was released in 1997 under a proprietary license, and then later in 1999 under the GNU General Public License v2.0 or later. Doom 3, a horror game built with the id Tech 4 engine, was released in 2004, followed by a 2005 Doom film. id returned to the fast-paced action of the classic games with the 2016 game Doom and the 2020 sequel Doom Eternal.

Gameplay

Doom is a first-person shooter presented with early 3D graphics. The player controls an unnamed space marine—later termed "Doomguy"—through a series of levels set in military bases on the moons of Mars and in hell. To finish a level, the player must traverse through the area to reach a marked exit room. Levels are grouped together into named episodes, with the final level focusing on a boss fight with a particularly difficult enemy. While the environment is presented in a 3D perspective, the enemies and objects are instead 2D sprites presented from several preset viewing angles, a technique sometimes referred to as 2.5D graphics with its technical name called ray casting. Levels are often labyrinthine, and a full screen automap is available which shows the areas explored to that point.

While traversing the levels, the player must fight a variety of enemies, including demons and possessed undead humans, while managing supplies of ammunition, health, and armor. Enemies often appear in large groups, and the game features five difficulty levels which increase the quantity and damage done by enemies, with enemies respawning upon death and moving faster than normal on the hardest difficulty setting. The monsters have very simple behavior, consisting of either moving toward their opponent, or attacking by throwing fireballs, biting, using magic abilities and clawing. They will reactively fight each other if one monster inadvertently harms another, though most monsters are immune to attacks from their own kind. The environment can include pits of toxic waste, ceilings that lower and crush objects, and locked doors requiring a keycard or a remote switch. The player can find weapons and ammunition throughout the levels or can collect them from dead enemies, including a pistol, a chainsaw, a plasma rifle, and the BFG 9000. Power-ups include health or armor points, a mapping computer, partial invisibility, a safety suit against toxic waste, invulnerability, or a super-strong melee berserker status.

The main campaign mode is single-player mode, in an episodic succession of missions. Two multiplayer modes are playable over a network: cooperative, in which two to four players team up to complete the main campaign,[5] and deathmatch, in which two to four players compete. Four-player online multiplayer mode via dialup was made available one year after launch through the DWANGO service.[6] Cheat codes give the player instant super powers including invulnerability, all weapons, and walking through walls.[7][8][9][10]

Plot

Doom is divided into three episodes: "Knee-Deep in the Dead", "The Shores of Hell", and "Inferno". A fourth episode, "Thy Flesh Consumed", was added in an expanded version of the game, The Ultimate Doom, released on April 30, 1995, two years after Doom and one year after Doom II. The campaign contains very few plot elements, with the minimal story instead given in the instruction manual and in short text segues between episodes.

In the future, an unnamed marine (known as the "Doom marine" or "Doom guy") is posted to a dead-end assignment on Mars after assaulting a superior officer who ordered his unit to fire on civilians. The Union Aerospace Corporation, which operates radioactive waste facilities there, allows the military to conduct secret teleportation experiments that go terribly wrong. A base on Phobos urgently requests military support, while Deimos disappears entirely, and the marine joins a combat force to secure Phobos. He waits at the perimeter as ordered while the entire assault team is wiped out. With no way off the moon, and armed with only a pistol, he enters the base intent on revenge.[11]

In "Knee-Deep in the Dead", the marine fights demons and possessed humans in the military and waste processing facilities on Phobos. The episode ends with the marine defeating two powerful Barons of Hell guarding a teleporter to the Deimos base. Emerging from the teleporter, he is overwhelmed and comes to with only a pistol again. In "The Shores of Hell", he fights on through Deimos research facilities that are corrupted with satanic architecture and kills a gigantic cyberdemon. From an overlook he discovers that the moon is floating above hell and rappels down to the surface. In "Inferno", the marine takes on hell itself and destroys a cybernetic spider-demon that masterminded the invasion of the moons. A portal to Earth opens and he steps through, only to find that Earth has also been invaded. "Thy Flesh Consumed" follows the marine's initial assault on the Earth invasion force, setting the stage for Doom II: Hell on Earth.

Development

Concept

In May 1992, id Software released Wolfenstein 3D, later called the "grandfather of 3D shooters",[12][13] specifically first-person shooters, because it established the fast-paced action and technical prowess commonly expected in the genre and greatly increased the genre's popularity.[12][14][15][16] Immediately following its release most of the id Software team began work on a set of episodes for the game, titled Spear of Destiny, while id co-founder and lead programmer John Carmack instead focused on technology research for the company's next game. Following the release of Spear of Destiny in September 1992, the team began to plan their next game. They wanted to create another 3D game using a new engine Carmack was developing, but were largely tired of Wolfenstein. They initially considered making another game in the Commander Keen series, as proposed by co-founder and lead designer Tom Hall, but decided that the platforming gameplay of the series was a poor fit for Carmack's fast-paced 3D engines. Additionally, the other two co-founders of id, designer John Romero and lead artist Adrian Carmack, wanted to create something in a darker style than the Keen games. John Carmack then came up with his own concept: a game about using technology to fight demons, inspired by the Dungeons & Dragons campaigns the team played, combining the styles of Evil Dead II and Aliens.[17][18] The concept originally had a working title of Green and Pissed, but Carmack soon renamed it Doom after a line in the 1986 film The Color of Money: "'What you got in there?' / 'In here? Doom.'"[17][19]

The team agreed to pursue the Doom concept, and development began in November 1992.[18] The initial development team was composed of five people: programmers John Carmack and Romero, artists Adrian Carmack and Kevin Cloud, and designer Hall.[20] They moved offices to a dark office building, which they named "Suite 666", and drew inspiration from the noises coming from the dentist's office next door. They also decided to cut ties with Apogee Software, their previous publisher, and self-publish Doom.[21]

Design

Early in development, rifts in the team began to appear. At the end of November, Hall delivered a design document, which he named the Doom Bible, that described the plot, backstory, and design goals for the project.[18] His design was a science fiction horror concept wherein scientists on the Moon open a portal from which aliens emerge. Over a series of levels, the player discovers that the aliens are demons while hell steadily infects the level design over the course of the game.[22] John Carmack not only disliked the idea but dismissed the idea of having a story at all: "Story in a game is like story in a porn movie; it's expected to be there, but it's not that important." Rather than a deep story, he wanted to focus on the technological innovations of the game, dropping the levels and episodes of Wolfenstein in favor of a fast, continuous world. Hall disliked the idea, but the rest of the team sided with Carmack.[22] Hall spent the next few weeks reworking the Doom Bible to work with Carmack's technological ideas.[18] Hall was forced to rework it again in December, however, after the team decided that they were unable to create a single, seamless world with the hardware limitations of the time, which contradicted much of the document.[18]

At the start of 1993, id put out a press release, touting Hall's story about fighting off demons while "knee-deep in the dead". The press release proclaimed the new game features that John Carmack had created, as well as other features, including multiplayer gaming features, that had not yet even been designed.[22] Early versions of the game were built to match the Doom Bible; a "pre-alpha" version of the first level includes Hall's introductory base scene.[23] Initial versions of the game also retain "arcade" elements present in Wolfenstein 3D, like score points and score items, but those were removed early in development as they were out of tone.[20] Other elements, such as a complex user interface, an inventory system, a secondary shield protection, and lives were modified and slowly removed over the course of development.[18][24]

Soon, however, the Doom Bible as a whole was rejected. Romero wanted a game even "more brutal and fast" than Wolfenstein, which did not leave room for the character-driven plot Hall had created. Additionally, the team believed it emphasized realism over entertaining gameplay, and they did not see the need for a design document at all.[22] Some ideas were retained, but the story was dropped and most of the game design was removed.[25] By early 1993, levels were being created for the game and a demo was produced. John Carmack and Romero, however, disliked Hall's military base-inspired level design. Romero especially believed that the boxy, flat level designs were uninspiring, too similar to Wolfenstein, and did not show off the engine's capabilities. He began to create his own, more abstract levels for the game, which the rest of the team saw as a great improvement.[22][26]

Hall was upset with the reception to his designs and how little impact he was having as the lead designer.[22][23] He was also upset with how much he was having to fight with John Carmack in order to get what he saw as obvious gameplay improvements, such as flying enemies, and began to spend less time at work.[18] In July the other founders of id fired Hall, who went to work for Apogee.[22] He was replaced in September, ten weeks before the game was released, by game designer Sandy Petersen, who was laid off from MicroProse 5 months prior.[27][28] In 2020, Petersen recalled that Carmack and Romero wanted to hire other artists, but Cloud and Adrian disagreed, saying that a designer was required to help build a cohesive gameplay experience. They relented and Petersen was immediately hired. He redesigned 20 of the 27 levels and they were well received by the team.[29]

The team also added a third programmer, Dave Taylor.[30] Petersen and Romero designed the rest of Doom's levels with different aims: the team believed that Petersen's designs were more technically interesting and varied, while Romero's were more aesthetically interesting.[28] In late 1993, after the multiplayer component was coded, the development team began playing four-player multiplayer games matches, which Romero termed "deathmatch".[31] According to Romero, the game's deathmatch mode was inspired by fighting games such as Street Fighter II, Fatal Fury, and Art of Fighting.[32]

Engine

Doom was programmed largely in the ANSI C programming language, with a few elements in assembly language, targeting the IBM PC and MS-DOS platform by compiling with Watcom C/C++ and using the included royalty-free 80386 DOS-extender.[33] id developed on NeXT computers running the NeXTSTEP operating system.[34] The data used by the game engine, including level designs and graphics files, are stored in WAD files, short for "Where's All the Data?". This allows for any part of the design to be changed without needing to adjust the engine code. Carmack designed this system so fans could easily modify the game; he had been impressed by the modifications made by fans of Wolfenstein 3D, and wanted to support that with an easily swappable file structure along with releasing the map editor online.[35]

Unlike Wolfenstein, which had flat levels with walls at right angles, the Doom engine allows for walls and floors at any angle or height, though two traversable areas cannot be on top of each other. The lighting system was based on adjusting the color palette of surfaces directly: rather than calculating how light traveled from light sources to surfaces using ray tracing, the game calculates the light level of a small area based on its distance from light sources. It then modifies the color palette of that section's surface textures to mimic how dark it would look.[34] This same system is used to cause far away surfaces to look darker than close ones.[22] Romero came up with new ways to use Carmack's lighting engine such as strobe lights.[22] He programmed engine features such as switches and movable stairs and platforms.[18][20] After Romero's complex level designs started to cause problems with the engine, Carmack began to use binary space partitioning to quickly select the reduced portion of a level that the player could see at a given time.[18][28][36] Taylor programmed other features into the game, added cheat codes; some, such as idspispopd, were based on ideas their fans had submitted online while eagerly awaiting the game.[20]

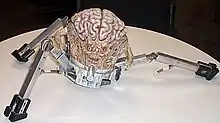

Adrian Carmack was the lead artist for Doom, with Kevin Cloud as an additional artist. They designed the monsters to be "nightmarish", with graphics that are realistic and dark instead of staged or rendered, so a mixed media approach was taken.[37] The artists sculpted models of some of the enemies, and took pictures of them in stop motion from five to eight different angles so that they could be rotated realistically in-game. The images were then digitized and converted to 2D characters with a program written by John Carmack.[22] Adrian Carmack made clay models for a few demons, and had Gregor Punchatz build latex and metal sculptures of the others.[18][20] The weapons were made from combined parts of children's toys.[18] The developers scanned themselves as well, using Cloud's arm for the marine's arm holding a gun, and Adrian's snakeskin boots and wounded knee for textures.[22]

Audio

As with Wolfenstein 3D, id hired composer Bobby Prince to create the music and sound effects. Romero directed Prince to make the music in techno and metal styles. Many tracks were directly inspired by songs by metal bands such as Alice in Chains and Pantera.[28][38] Prince believed that ambient music would be more appropriate, and produced numerous tracks in both styles in hope of convincing the team, and Romero incorporated both.[39] Prince did not make music for specific levels, as they were composed before the levels were completed; instead, Romero assigned each track to each level late in development. Prince created the sound effects based on short descriptions or concept art of a monster or weapon, and adjusted them to match the completed animations.[40] The monster sounds were created from animal noises, and Prince designed all the sounds to be distinct on the limited sound hardware of the time, even when many sounds were playing at once.[28][39] He also designed the sound effects to play on different frequencies from those used for the MIDI music, so they would clearly cut through the music.[41]

Mods

The ability for user-generated content to provide custom levels and other game modifications using WAD files became a popular aspect of Doom. Gaining the first large mod-making community, Doom affected the culture surrounding first-person shooters, and also the industry. Several future professional game designers started their careers making Doom WADs as a hobby, such as Tim Willits, who later became the lead designer at id Software.

The first level editors appeared in early 1994, and additional tools have been created that allow most aspects of the game to be edited. Although the majority of WADs contain one or several custom levels mostly in the style of the original game, others implement new monsters and other resources, and heavily alter the gameplay. Several popular movies, television series, other video games and other brands from popular culture have been turned into Doom WADs by fans, including Aliens, Star Wars, The Simpsons, South Park, Sailor Moon, Dragon Ball Z, Pokémon, Beavis and Butt-head, Batman, and Sonic the Hedgehog.[42] Some works, like the Theme Doom Patch, combined enemies from several films, such as Aliens, Predator, and The Terminator. Some add-on files were also made that changed the sounds made by the various characters and weapons.

From 1994 to 1995, WADs were primarily distributed online over bulletin board systems or sold in collections on compact discs in computer shops, sometimes bundled with editing guide books. FTP servers became the primary method in later years. A few WADs have been released commercially, including the Master Levels for Doom II, which was released in 1995 along with Maximum Doom, a CD containing 1,830 WADs that had been downloaded from the Internet. The idgames FTP archive contains more than 18,000 files,[43] and this represents only a fraction of the complete output of Doom fans. Third-party programs were also written to handle the loading of various WADs, since all commands must be entered on the DOS command line to run. A typical launcher would allow the player to select which files to load from a menu, making it much easier to start. In 1995, WizardWorks released the D!Zone pack featuring hundreds of levels for Doom and Doom II.[44] D!Zone was reviewed in Dragon by Jay & Dee; Jay gave the pack 1 out of 5 stars, and Dee gave the pack 1½ stars.[44]

In 2016, Romero published two new Doom levels: E1M4b ("Phobos Mission Control") and E1M8b ("Tech Gone Bad").[45][46] In 2018, for the 25th anniversary of Doom, Romero announced Sigil, an unofficial Episode Five consisting of 9 missions.[47] It was released on May 22, 2019, with a soundtrack by Buckethead. It was then released for free on May 31, with a MIDI soundtrack by James Paddock.[48]

Release

With plans to self-publish, the team had to set up the systems to sell Doom as it neared completion. Jay Wilbur, who had been hired as CEO and sole member of the business team, planned the marketing and distribution of Doom. He believed that the mainstream press was uninterested in the game, and as id would make the most money off of copies they sold directly to customers—up to 85 percent of the planned US$40 price—he decided to leverage the shareware market as much as possible, buying only a single ad in any gaming magazine. Instead, he reached out directly to software retailers, offering them copies of the first Doom episode for free, allowing them to charge any price for it, in order to spur customer interest in buying the full game directly from id.[28]

Doom's original release date was the third quarter of 1993, which the team did not meet. By December 1993, the team was working non-stop on the game, with several employees sleeping at the office. Programmer Dave Taylor claimed that working on the game gave him such a rush that he would pass out from the intensity. Id began receiving calls from people interested in the game or angry that it had missed its planned release date, as hype for the game had been building online. At midnight on December 10, 1993, after working for 30 straight hours, the development team at id uploaded the first episode of the game to the Internet, letting interested players distribute it for them. So many users were connected to the first FTP server that they planned to upload the game to, at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, that even after the network administrator increased the number of connections while on the phone with Wilbur, id was unable to connect, forcing them to kick all other users off to allow id to upload the game. When the upload finished thirty minutes later, 10,000 people attempted to download the game at once, crashing the university's network.[31]

Within hours of Doom's release, university networks were banning Doom multiplayer games, as a rush of players overwhelmed their systems.[31] After being alerted by network administrators the morning after release that the game's deathmatch network connection setup was crippling some computer networks, John Carmack quickly released a patch to change it, though many administrators had to implement Doom-specific rules to keep their networks from crashing due to the overwhelming traffic.[49] In 1995, an expanded version of Doom developed for the retail market,[6] The Ultimate Doom, was released by GT Interactive, and contained a fourth episode.[50]

In late 1995, Doom was estimated to be installed on more computers worldwide than Microsoft's new operating system, Windows 95.[1] According to Windows producer Gabe Newell, who later founded the game company Valve,[1] "[id] ... didn't even distribute through retail, it distributed through bulletin boards and other pre-internet mechanisms. To me, that was a lightning bolt. Microsoft was hiring 500-people sales teams and this entire company was 12 people, yet it had created the most widely distributed software in the world. There was a sea change coming."[51] He said that Doom "made me rethink everything I thought about games — control systems, design, rendering. It convinced me that games were the future of entertainment."[52]

Ports

Microsoft hired id Software to port Doom to Windows with the WinG API,[53] and Microsoft CEO Bill Gates briefly considered buying the company.[6] Newell led development of a Windows 95 port of Doom to promote Windows as a gaming platform.[1] One promotional video for Windows 95 had Gates digitally superimposed into the game.[54]

An unofficial port of Doom to Linux was released by id programmer Dave Taylor in 1994; it was hosted by id but not supported or made official.[55] Official ports were released for Sega 32X, Atari Jaguar, and Mac OS in 1994, SNES and PlayStation in 1995, 3DO in 1996, Sega Saturn in 1997, Acorn Risc PC in 1998, Game Boy Advance in 2001, Xbox 360 in 2006, iOS in 2009, and Nintendo Switch in 2019. Notable exceptions in the list of official ports, as well as Linux, are AmigaOS and Symbian.[56][57][58] Some of these were bestsellers even many years after the initial release.[59] Doom has also been ported unofficially to numerous platforms; so many ports exist, including for esoteric devices such as smart thermostats and oscilloscopes, that variations on "It runs Doom" or "Can it run Doom?" are long-running memes.[60][61][62]

Reception

| Aggregator | Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atari Jaguar | GBA | iOS | PC | PS | SNES | Xbox 360 | |

| GameRankings | 80%[63] | 83%[64] | 84%[65] | 54%[66] | 80%[67] | ||

| Metacritic | 81/100[68] | 84/100[69] | 82/100[70] | ||||

| Publication | Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atari Jaguar | GBA | iOS | PC | PS | SNES | Xbox 360 | |

| AllGame | |||||||

| CVG | 93%[74] | 91%[75] | 92%[75] | ||||

| Dragon | |||||||

| Edge | 7/10[77] | ||||||

| GamesMaster | 90%[78] | ||||||

| GameSpot | 9/10[79] | ||||||

| Next Generation | |||||||

| Total! | 93%[81] | ||||||

| TouchArcade | |||||||

| Publication | Award |

|---|---|

| Computer Gaming World | 1994 Game of the Year[83] #5, 150 Best Games of All Time[84] #3, 15 Most Innovative Computer Games[85] |

| GameSpy | #1, Top 50 Games of All Time[86] |

| IGN | #44, Top 100 Games of All Time (2003)[87] #39, Top 100 Games (2005)[88] #2, Top 100 Shooters[89] |

| Retro Gamer | #9, Top Retro Games |

| Library of Congress | Game canon[90] |

| GameTrailers | #1, Top Ten Breakthrough PC Games[91] |

| Game Informer | #7, Top 200 Games of All Time[92] |

| Time | All-Time 100 Video Games[93] |

| GameSpot | The Greatest Games of All Time[94] |

| PC Gamer UK | #3, Top 50 Games of All Time[95] |

Contemporary reviews

Although Petersen said Doom was "nothing more than the computer equivalent of Whack-A-Mole",[96] Doom received critical acclaim and was widely praised in the gaming press, broadly considered to be one of the most important and influential titles in gaming history. Upon release, GamesMaster gave it a 90% rating.[78] Dragon gave it five stars, praising the improvements over Wolfenstein 3D, the "fast-moving arcade shoot 'em up" gameplay, and network play.[76] Computer and Video Games gave the game a 93% rating, praising its atmosphere and stating that "the level of texture-mapped detail and the sense of scale is awe inspiring", but criticized the occasionally repetitive gameplay and considered the violence excessive.[74] A common criticism of Doom was that it was not a true 3D game, since the game engine did not allow corridors and rooms to be stacked on top of one another (room-over-room), and instead relied on graphical trickery to make it appear that the player character and enemies were moving along differing elevations.[97]

Computer Gaming World stated in February 1994 that Wolfenstein 3D fans should "look forward to a delight of insomnia", and "Since networking is supported, bring along a friend to share in the visceral delights".[98] A longer review in March 1994 said that Doom "was worth the wait ... a wonderfully involved and engaging game", and its technology "a new benchmark" for the gaming industry. The reviewer praised the "simply dazzling" graphics", and reported that "DeathMatches may be the most intense gaming experience available today". While criticizing the "ho-hum endgame" with a too-easy end boss, he concluded that Doom "is a virtuoso performance".[99]

Edge praised the graphics and levels but criticized the "simple 3D perspective maze adventure/shoot 'em up" gameplay. The review concluded: "You’ll be longing for something new in this game. If only you could talk to these creatures, then perhaps you could try and make friends with them, form alliances... Now, that would be interesting."[77] Decades later, the review attracted mockery, and "if only you could talk to these creatures" became a running joke in video game culture. A 2016 piece in the International Business Times defended the sentiment, saying it anticipated the dialogue systems of games such as The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, Mass Effect and Undertale.[100]

In 1994, PC Gamer UK named Doom the third-best computer game of all time. The editors wrote: "Although it's only been around for a couple of months, Doom has already done more to establish the PC's arcade clout than any other title in gaming history."[95] In 1994 Computer Gaming World named Doom Game of the Year.[83] The various Doom console ports have received generally favorable reviews.[101][65][63]

Retrospective reception

In 1995, Next Generation said it was "The most talked about PC game ever – and with good reason. Running on a 486 machine (essential for maximum effect), Doom took PC graphics to a totally new level of speed, detail, and realism, and provided a genuinely scary degree of immersion in the gameworld."[102] In the same year, Flux magazine ranked the pc version 3rd on their "Top 100 Video Games."[103] In 1996, Computer Gaming World named it the fifth best video game of all time,[84] and the third most-innovative game.[85] In 1996, GamesMaster rated the SNES version 7th on their "The Gamesmaster SNES Top 10."[104] In 1998, PC Gamer declared it the 34th-best computer game ever released, and the editors called it "Probably the most imitated game of all time, Doom continued what Wolfenstein 3D began and elevated the fledgling 3D-shooter genre to blockbuster status".[105]

In 2001, Doom was voted the number one game of all time in a poll among over 100 game developers and journalists conducted by GameSpy.[86] In 2003, IGN ranked it as the 44th top video game of all time and also called it "the breakthrough game of 1993", adding: "Its arsenal of powerful guns (namely the shotgun and BFG), intense level of gore and perfect balance of adrenaline-soaked action and exploration kept this gamer riveted for years."[87] PC Gamer proclaimed Doom the most influential game of all time in its ten-year anniversary issue in April 2004.

In 2004, readers of Retro Gamer voted Doom as the ninth top retro game, with the editors commenting: "Only a handful of games can claim that they've changed the gaming world, and Doom is perhaps the most qualified of them all."[106] In 2005, IGN ranked it as the 39th top game.[88] On March 12, 2007, The New York Times reported that Doom was named to a list of the ten most important video games of all time, the so-called game canon.[107] The Library of Congress took up this video game preservation proposal and began with the games from this list.[90][108]

In 2009, GameTrailers ranked Doom as the number one "breakthrough PC game".[91] That year Game Informer put Doom sixth on the magazine's list of the top 200 games of all time, stating that it gave "the genre the kick start it needed to rule the gaming landscape two decades later".[92] Game Informer staff also put it sixth on their 2001 list of the 100 best games ever.[109] IGN included Doom at 2nd place in the Top 100 Video Game Shooters of all Time, just behind Half-Life, citing the game's "feel of running and gunning", memorable weapons and enemies, pure and simple fun, and its spreading on nearly every gaming platform in existence.[89]

In 2012, Time named it one of the 100 greatest video games of all time as "it established the look and feel of later shooters as surely as Xerox PARC established the rules of the virtual desktop", adding that "its impact also owes a lot to the gonzo horror sensibility of its designers, including John Romero, who showed a bracing lack of restraint in their deployment of gore and Satanic iconography".[93] Including Doom on the list of the greatest games of all time, GameSpot wrote that "despite its numerous appearances in other formats and on other media, longtime fans will forever remember the original 1993 release of Doom as the beginning of a true revolution in action gaming".[94] In 2015, The Strong National Museum of Play inducted Doom to its World Video Game Hall of Fame.[110] In 2018, Complex listed the game #47 in their "The Best Super Nintendo Games of All Time."[111]

In 2021, Kotaku listed Doom as the third best game in the series, behind Doom II and Doom (2016). They said that the gameplay "still holds up", but argued it was inferior to Doom II due to the latter's improved enemy variety.[112]

Sales

With the release of Doom, millions of users installed the Shareware version on their computer and id Software quickly began making $100,000 daily (for $9 per copy).[113][114] Sandy Petersen later remarked that the game "sold a couple of hundred thousand copies during its first year or so", as piracy kept its initial sales from rising higher, and Wilbur in 1995 estimated first-year sales as 140,000.[115][116] id sold 3.5 million physical copies from its release through 1999.[117] According to PC Data, which tracked sales in the United States, by April 1998 Doom's shareware edition had yielded 1.36 million units sold and $8.74 million in revenue in the United States. This led PC Data to declare it the country's fourth-best-selling computer game for the period between January 1993 and April 1998.[118] The Ultimate Doom SKU reached sales of 787,397 units by September 1999. At the time, PC Data ranked them as the country's eighth- and 20th-best-selling computer games since January 1993.[119] In addition to its sales, the game's status as shareware dramatically increased its market penetration. PC Zone's David McCandless wrote that the game was played by "an estimated six million people across the globe",[115] and other sources estimate that 10–20 million people played Doom within 24 months of its launch.[120]

Doom became a problem at workplaces, both occupying the time of employees and clogging computer networks. Intel,[121] Lotus Development, and Carnegie Mellon University were among many organizations reported to form policies specifically disallowing Doom-playing during work hours. At the Microsoft campus, Doom was by one account equal to a "religious phenomenon".[6] Doom was #1 on Computer Gaming World's "Playing Lately?" survey for February 1994. One reader said that "No other game even compares to the addictiveness of NetDoom with four devious players! ... The only game I've stayed up 72+ straight hours to play", and another reported that "Linking four people together for a game of Doom is the quickest way to destroy a productive, boring evening of work".[122]

Controversies

Doom was notorious for its high levels of graphic violence[123] and satanic imagery, which generated controversy from a broad range of groups. Doom for the 32X was one of the first video games to be given an M for Mature rating from the Entertainment Software Rating Board due to its violent gore and nature.[124] Yahoo! Games listed it as one of the top ten most controversial games of all time.[125] It was criticized by religious organizations for its diabolic undertones and was dubbed a "mass murder simulator" by critic and Killology Research Group founder David Grossman.[126] Doom prompted fears that the then-emerging virtual reality technology could be used to simulate extremely realistic killing.

The game again sparked controversy in the United States when it was found that Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, who committed the Columbine High School massacre on April 20, 1999, were avid players of the game. While planning for the massacre, Harris said in his journal that the killing would be "like playing Doom", and "it'll be like the LA riots, the Oklahoma bombing, World War II, Vietnam, Duke Nukem and Doom all mixed together", and that his shotgun was "straight out of the game".[127] A rumor spread afterwards that Harris had designed a Doom level that looked like the high school, populated with representations of Harris's classmates and teachers, and that he practiced for the shootings by playing the level repeatedly. Although Harris did design custom Doom levels (which later became known as the "Harris levels"), none have been found to be based on Columbine High School.[128]

In the earliest release versions, the level E1M4: Command Control contains a swastika-shaped structure, which was put in as a homage to Wolfenstein 3D. The swastika was removed in later versions; according to Romero, the change was done out of respect after id Software received a complaint from a military veteran.[20]

Legacy

Doom franchise

Doom has appeared in several forms in addition to video games, including a Doom comic book, four novels by Dafydd Ab Hugh and Brad Linaweaver (loosely based on events and locations in the games), a Doom board game and a live-action film starring Karl Urban and The Rock released in 2005. The game's development and impact on popular culture is the subject of the book Masters of Doom: How Two Guys Created an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture by David Kushner.

The Doom series remained dormant between 1997 and 2000, when Doom 3 was finally announced. A retelling of the original Doom using entirely new graphics technology and a slower paced survival horror approach, Doom 3 was hyped to provide as large a leap in realism and interactivity as the original game and helped renew interest in the franchise when it was released in 2004, under the id Tech 4 game engine.

The series again remained dormant for 10 years until a reboot, simply titled Doom and running on the new id Tech 6, was announced with a beta access to players that had pre-ordered Wolfenstein: The New Order. The game held its closed alpha multiplayer testing in October 2015, as closed and open beta access ran during March to April 2016. Returning to the series' roots in fast-paced action and minimal storytelling, the full game eventually released worldwide on May 13, 2016. The project initially started as Doom 4 in May 2008, set to be a remake of Doom II: Hell on Earth and ditching the survival horror aspect of Doom 3. Development completely restarted as id's Tim Willits remarked that Doom 4 was "lacking the personality of the long-running shooter franchise".[129]

Clones

Doom was influential and dozens of new first-person shooter games appeared following Doom's release, often referred to as "Doom clones".[112] The term was initially popular, and after 1996, gradually replaced by "first-person shooter", which had firmly superseded around 1998. Some of these were cheap clones, hastily assembled and quickly forgotten, and others explored new grounds of the genre with high acclaim. Many of Doom's closely imitated features include the selection of weapons and cheat codes. Some successors include Apogee's Rise of the Triad (based on the Wolfenstein 3D engine) and Looking Glass Studios's System Shock. The popularity of Star Wars-themed WADs is rumored to have been the factor that prompted LucasArts to create their first-person shooter Dark Forces.[130]

The Doom engine was licensed by id Software to several other companies, who released their own games using the technology, including Heretic, Hexen: Beyond Heretic, Strife: Quest for the Sigil, and Hacx: Twitch 'n Kill. A Doom-based game called Chex Quest was released in 1996 by Ralston Foods as a promotion to increase cereal sales,[131] and the United States Marine Corps produced Marine Doom as a training tool, later released to the public.

When 3D Realms released Duke Nukem 3D in 1996, a tongue-in-cheek science fiction shooter based on Ken Silverman's technologically similar Build engine, id Software had nearly finished developing Quake, its next-generation game, which mirrored Doom's success for much of the remainder of the 1990s and reduced interest in its predecessor (Wolfenstein 3D).

Community

In addition to the thrilling nature of the single-player game, the deathmatch mode was an important factor in the game's popularity. Doom was not the first first-person shooter with a deathmatch mode; Maze War, an FPS released in 1974, was running multiplayer deathmatch over ethernet on Xerox computers by 1977. The widespread distribution of PC systems and the violence in Doom made deathmatching particularly attractive. Two-player multiplayer was possible over a phone line by using a modem, or by linking two PCs with a null-modem cable. Because of its widespread distribution, Doom hence became the game that introduced deathmatching to a large audience and was also the first game to use the term "deathmatch".[132]

Although the popularity of the Doom games dropped with the release of more modern first-person shooters, the game still retains a strong fan base that continues to this day by playing competitively and creating WADs, and Doom-related news is still tracked at multiple websites such as Doomworld. Interest in Doom was renewed in 1997, when the source code for the Doom engine was released (it was also placed under the GNU GPL-2.0-or-later on October 3, 1999). Fans then began porting the game to various operating systems, even to previously unsupported platforms such as the Dreamcast. As for the PC, over 50 different Doom source ports have been developed. New features such as OpenGL rendering and scripting allow WADs to alter the gameplay more radically.

Devoted players have spent years creating speedruns for Doom, competing for the quickest completion times of individual levels and the whole game and sharing knowledge about routes through the levels and how to exploit bugs in the Doom engine for shortcuts. Doom was one of the first games to have a speedrunning community, which has remained active up until the present day. A record speedrun on E1M1, the first level in the game, was achieved in September 1998, and took 20 years and "tens of thousands of futile attempts" in order to be surpassed.[133][134] Achievements include the completion of both Doom and Doom II on the "Ultra-Violence" difficulty setting in less than 30 minutes each. In addition, a few players have also managed to complete Doom II in a single run on the difficulty setting "Nightmare!", on which monsters are more aggressive, launch faster projectiles (or, in the case of the Pinky Demon, simply move faster), and respawn roughly 30 seconds after they have been killed (level designer John Romero characterized the idea of such a run as "[just having to be] impossible").[135] Movies of most of these runs are available from the COMPET-N website.[136]

One notable fan of Doom is Christoph Schneider from the German rock band Rammstein; he uses the stage name "Doom" which was inspired by the video game. Schneider needed a stage name for the German copyright agency, but found there were too many Christoph Schneiders in the entertainment industry. Schneider's band mate Paul Landers suggested the name "Doom" because they liked the game. Schneider has said that had he known that name would be on every Rammstein record he played on, he would have chosen a different one.

Notes

- The 2019 release uses Unity.

- Consalvo, Mia (2016). Atari to Zelda: Japan's Videogames in Global Contexts. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03439-5.

- Pinchbeck, Dan (2013). Doom: Scarydarkfast. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-05191-5.

- Kushner, David (2004). Masters of Doom: How Two Guys Created an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture. Random House. ISBN 978-0-8129-7215-3.

- Mendoza, Jonathan (1994). The Official DOOM Survivor's Strategies and Secrets. Sybex. ISBN 978-0-7821-1546-8.

- Slaven, Andy (2002). Video Game Bible, 1985-2002. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55369-731-2.

References

- Sebastian Anthony (September 24, 2013). "Gabe Newell Made Windows a Viable Gaming Platform, and Linux Is Next". ExtremeTech. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- Gach, Ethan (July 26, 2019). "Looks Like The Original Doom Games Are Coming To Switch As Soon As Today [Update]". Kotaku.

- Craddock, Ryan (July 26, 2019). "The Original DOOM, DOOM II And DOOM 3 Have All Surprise Launched On Nintendo Switch". Nintendo Life. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- "GBA Top 10 Games - 2001". GameShark. No. Holiday. December 2001. p. 69.

- Keizer, Gregg (April 1994). "Virtual Worlds - Doom". Electronic Entertainment. No. 4. IDG. p. 94.

- Kushner, David (2003). Masters of Doom: How Two Guys Created an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-375-50524-9.

- "The 10 Greatest Cheat Codes in Gaming HistoryDoom: God Mode". Complex Networks. Archived from the original on July 17, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

- "DOOM PS4 Trophies List Revealed". Game Rant. May 3, 2016. Archived from the original on October 22, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

- "Doom, the original and best first-person shooter, is 20 years old today - ExtremeTech". Archived from the original on October 22, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

- "The Page of Doom: The Cheats". Archived from the original on September 11, 2016. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

- Transcripts from printed manuals by Ledmeister. "DOOMTEXT.HTM: Storylines for Doom, Doom II, Final Doom, Doom 64". Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- Computer Gaming World. "CGW's Hall of Fame". 1UP.com. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on July 27, 2016. Retrieved July 27, 2016.

- Video Game Bible, 1985-2002, p. 53

- Williamson, Colin. "Wolfenstein 3D DOS Review". AllGame. All Media Network. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved July 27, 2016.

- "IGN's Top 100 Games (2003)". IGN. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on April 19, 2016. Retrieved July 27, 2016.

- Shachtman, Noah (May 8, 2008). "May 5, 1992: Wolfenstein 3-D Shoots the First-Person Shooter Into Stardom". Wired. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on October 25, 2011. Retrieved July 27, 2016.

- Masters of Doom, pp. 118–121

- Romero, John; Hall, Tom (2011). Classic Game Postmortem – Doom (Video). Game Developers Conference. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- Antoniades, Alexander (August 22, 2013). "Monsters from the Id: The Making of Doom". Gamasutra. UBM. Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- "We Play Doom with John Romero". IGN. Ziff Davis. December 10, 2013. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- Masters of Doom, pp. 122–123

- Masters of Doom, pp. 124–131

- Batchelor, James (January 26, 2015). "Video: John Romero reveals level design secrets while playing Doom". MCV. NewBay Media. Archived from the original on February 2, 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- "On the Horizon". Game Players PC Entertainment. Vol. 6, no. 3. GP Publications. May 1993. p. 8.

- The Official DOOM Survivor's Strategies and Secrets, pp. 249–250

- Romero, John; Barton, Matt (March 13, 2010). Matt Chat 53: Doom with John Romero (Video). Matt Barton. Archived from the original on November 24, 2016. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- Bub, Andrew S. (July 10, 2002). "Sandy Petersen Speaks". GameSpy. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on March 22, 2005. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- Masters of Doom, pp. 132–147

- Petersen, Sandy. "Tales from the Dark Days of Id Software". YouTube. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- Romero, John (2016). The Early Days of id Software (Video). Game Developers Conference. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- Masters of Doom, pp. 148–153

- Atari to Zelda, pp. 201–203

- "» the Shareware Scene, Part 4: DOOM the Digital Antiquarian".

- Schuytema, Paul C. (August 1994). "The Lighter Side of Doom". Computer Gaming World. No. 121. pp. 140–142. ISSN 0744-6667. Archived from the original on January 2, 2018. Retrieved January 1, 2018.

- Masters of Doom, p. 166

- Hutchison, Andrew (2008). "Making the water move: techno-historic limits in the game aesthetics of Myst and Doom". Game Studies. 8 (1).

- The Official DOOM Survivor's Strategies and Secrets, p. 247

- Romero, John (April 19, 2005). "Influences on Doom Music". rome.ro. Archived from the original on September 1, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- Doom: Scarydarkfast, pp. 52–55

- Prince, Bobby (December 29, 2010). "Deciding Where To Place Music/Sound Effects In A Game". Bobby Prince Music. Archived from the original on August 12, 2011. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- Composers Play - "Doom" Coop with Bobby Prince! - Part 4 on YouTube

- Sonic Retro (2013). "Sonic Doom II – Bots on Mobious". Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- Doomworld. "/idgames database". Archived from the original on May 28, 2014. Retrieved September 3, 2005.

- Jay & Dee (May 1995). "Eye of the Monitor". Dragon (217): 65–74.

- "John Romero's new Doom level is a tease for his next project". Polygon. April 26, 2016. Archived from the original on July 4, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- "You can download John Romero's first new Doom level in 21 years right now". Polygon. January 15, 2016. Archived from the original on October 14, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- "Download SIGIL". Romero Games. May 31, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- Wales, Matt (May 31, 2019). "John Romero's free, unofficial fifth Doom episode Sigil is finally here". Eurogamer.

- Totilo, Steven (December 10, 2013). "Memories Of Doom, By John Romero & John Carmack". Kotaku. Univision Communications. Archived from the original on October 15, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- "The Ultimate Doom: Thy Flesh Consumed" (in French). Jeuxvideo.com. Archived from the original on November 4, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Narcisse, Evan (May 1, 2012). "Seems like Doom might have inspired Valve to build Steam". Kotaku Australia. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

- Ingham, Tim (April 4, 2011). "Gabe Newell: My 3 favourite games". Computer and Video Games. Future plc. Archived from the original on February 11, 2015. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- Wilson, Johnny L.; Brown, Ken; Lombardi, Chris; Weksler, Mike; Coleman, Terry (July 1994). "The Designer's Dilemma: The Eighth Computer Game Developers Conference". Computer Gaming World. pp. 26–31. Archived from the original on November 16, 2017. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- Lombardo, Mike. "Bonus movie: Bill Gates "DOOM" video". Reel Splatter. Archived from the original on October 2, 2009. Retrieved November 15, 2005.

- Taylor, Dave (September 9, 1994). "Linux DOOM for X released". Newsgroup: comp.os.linux.announce. Usenet: ann-13210.779119772@cs.cornell.edu. Archived from the original on March 28, 2017.

- "Doom (1993) – PC". IGN. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on April 30, 2017. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- Hawken, Kieren (September 2, 2017). "Doom". The A-Z of Atari Jaguar Games – Volume 1. Andrews UK. ISBN 978-1-78538-734-0.

- Cobbett, Richard (August 3, 2012). "Doom 3 shines flashlight on The Lost Mission (And doesn't even need to put down its gun!)". PC Gamer. Future. Archived from the original on February 25, 2015. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Gallup UK PlayStation sales chart, April 1996, published in Official UK PlayStation Magazine issue 5

- "But Can It Run Doom?". Wired. Condé Nast. January 1, 2003. Archived from the original on April 29, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Hurley, Leon (May 15, 2017). "Watch Doom running on an ATM, a printer... and 10 other weird, non-gaming machines". GamesRadar+. Future. Archived from the original on July 18, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Petitte, Omri (February 2, 2016). "Pianos, printers, and other surprising things you can play Doom on". PC Gamer. Future. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- "Doom for Game Boy Advance". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on July 18, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- "Doom Classic for iOS (iPhone/iPad)". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on August 12, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- "Doom for PlayStation". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on July 18, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- "Doom for Super Nintendo". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on August 12, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- "Doom for Xbox 360". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on August 13, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- "Doom for Game Boy Advance Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- "Doom Classic for iPhone/iPad Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on July 17, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- "Doom for Xbox 360 Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on July 3, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- "Doom (GBA) Review". Archived from the original on November 14, 2014.

- Mauser, Evan A. "Doom – Review". Allgame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- "Doom (PS) Review". Archived from the original on November 14, 2014.

- "Reviews: DOOM". Computer and Video Games. No. 148. March 1994. pp. 72–73. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- "The Computer and Video Games Christmas Buyers Guide". Computer and Video Games. No. 170 (January 1996). EMAP. December 10, 1995. pp. 8–9.

- Kaufman, Doug (March 1994). "Eye of the Monitor: DOOM" (PDF). Dragon. No. 203. TSR, Inc. pp. 59–62. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- "Doom Review". Edge. No. 7 (April 1994). March 3, 1994. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012.

- "Doom (1993) for PC". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on August 29, 2014. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- Scisco, Peter (May 1, 1996). "The Ultimate Doom Review (GameSpot)". GameSpot. Archived from the original on September 7, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- "Finals". Next Generation. No. 1. Imagine Media. January 1995. p. 92.

- Danny (October 1995). "Doom". Total! (46): 24–27. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- Kim, Arnold (October 31, 2009). "'Doom Classic' Gameplay Video and Early Impressions". TouchArcade. Archived from the original on August 13, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- "Announcing The New Premier Awards". Computer Gaming World. June 1994. pp. 51–58. Archived from the original on July 3, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- "150 Best Games of All Time". Computer Gaming World. November 1996. pp. 64–80. Archived from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- "The 15 Most Innovative Computer Games". Computer Gaming World. November 1996. p. 102. Archived from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- GameSpy (2001). "GameSpy's Top 50 Games of All Time". GameSpy. Archived from the original on July 10, 2010. Retrieved November 15, 2005.

- "IGN's Top 100 Games of All Time". Uk.top100.ign.com. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- "IGN's Top 100 Games". Uk.top100.ign.com. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- "Doom". IGN. Archived from the original on July 14, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- Ransom-Wiley, James. "10 most important video games of all time, as judged by 2 designers, 2 academics, and 1 lowly blogger". Joystiq. Archived from the original on April 22, 2014.

- "GT Top Ten Breakthrough PC Games". GameTrailers.com. July 28, 2009. Archived from the original on January 7, 2012. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- The Game Informer staff (December 2009). "The Top 200 Games of All Time". Game Informer. No. 200. pp. 44–79. ISSN 1067-6392. OCLC 27315596.

- "All-Time 100 Video Games". Time. Time Inc. November 15, 2012. Archived from the original on November 16, 2012. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- Shoemaker, Brad (January 31, 2006). "The Greatest Games of All Time: Doom". GameSpot.com. Archived from the original on May 28, 2013. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- Staff (April 1994). "The PC Gamer Top 50 PC Games of All Time". PC Gamer UK. No. 5. pp. 43–56.

- Schuytema, Paul C. (August 1994). "The Lighter Side Of Doom". Computer Gaming World. pp. 140, 142. Archived from the original on January 2, 2018. Retrieved January 1, 2018.

- "The First Pictures". Maximum: The Video Game Magazine. Emap International Limited (1): 134–5. October 1995.

Doom was criticised for not being a true 3D product – in fact, it's best described as 2.5D (if you will) because although each level could be staged at various heights, it was impossible to stack two corridors on top of one another in any given stage.

- "Taking A Peek". Computer Gaming World. February 1994. pp. 212–220. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- Walker, Bryan (March 1994). "Hell's Bells And Whistles". Computer Gaming World. pp. 38–39. Archived from the original on November 10, 2017. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- "Doom: Infamous \'talk to the monsters\' review was on the right side of history". International Business Times UK. May 13, 2016. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- "Doom for Jaguar". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- "The Games". Next Generation. Imagine Media (4): 53. April 1995.

- "Top 100 Video Games". Flux. Harris Publications (4): 25. April 1995.

- "The GamesMaster SNES Top 10" (PDF). GamesMaster (44): 75. July 1996.

- The PC Gamer (October 1998). "The 50 Best Games Ever". PC Gamer US. 5 (10): 86, 87, 89, 90, 92, 98, 101, 102, 109, 110, 113, 114, 117, 118, 125, 126, 129, 130.

- Retro Gamer 9, page 60.

- Chaplin, Heather (March 12, 2007). "Is That Just Some Game? No, It's a Cultural Artifact". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- Owens, Trevor (September 26, 2012). "Yes, The Library of Congress Has Video Games: An Interview with David Gibson". blogs.loc.gov. Archived from the original on December 5, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- Cork, Jeff (November 16, 2009). "Game Informer's Top 100 Games of All Time (Circa Issue 100)". Game Informer. Archived from the original on November 11, 2013. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- "DOOM". The Strong National Museum of Play. The Strong. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- "The Best Super Nintendo Games of All Time". Complex. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- "Let's Rank All The Doom Games, From Worst To Best". Kotaku. April 24, 2021. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- "'Doom' Turns 20: We Take A Look at the Game's History". International Business Times. December 12, 2013. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- Coldewey, David (December 10, 2013). "Knee deep in history: 20 years of "Doom"". NBC News. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- McCandless, David (June 12, 2002). "Games That Changed The World: Doom". PC Zone. Archived from the original on July 9, 2007. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- "Games". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. October 29, 1995. p. 93. Retrieved January 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Clark, Stuart (February 20, 1999). "Denting the ego of Id". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 209. Retrieved September 7, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Player Stats: Top 10 Best-Selling Games, 1993 – Present". Computer Gaming World. No. 170. September 1998. p. 52. ISSN 0744-6667.

- IGN Staff (November 1, 1999). "PC Data Top Games of All Time". IGN. Archived from the original on March 2, 2000. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- Dunnigan, James F. (January 3, 2000). Wargames Handbook, Third Edition: How to Play and Design Commercial and Professional Wargames. Writers Club Press. pp. 14–17.

- "Intel Bans Doom!". Computer Gaming World. March 1994. p. 14. Archived from the original on November 10, 2017. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- "What You've Been Playing Lately". What's Hot. Computer Gaming World. April 1994. p. 184. Archived from the original on November 11, 2017. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- Entertainment Software Rating Board. "Game ratings". Archived from the original on February 16, 2006. Retrieved December 4, 2004.

- "The ESRB is Turning 20 – IGN". IGN. September 16, 2014. Archived from the original on February 16, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- Ben Silverman (September 17, 2007). "Controversial Games". Yahoo! Games. Archived from the original on April 29, 2009. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

- Irvine, Reed; Kincaid, Cliff (1999). "Video Games Can Kill". Accuracy in Media. Archived from the original on October 5, 2007. Retrieved November 15, 2005.

- 4–20: a Columbine site. "Basement Tapes: quotes and transcripts from Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold's video tapes". Archived from the original on February 23, 2006. Retrieved November 15, 2005.

- Mikkelson, Barbara (January 1, 2005). "Columbine Doom Levels". Snopes. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- "id Software and Bethesda's Cancelled 'Doom 4' Just Wasn't 'Doom' Enough". Multiplayerblog.mtv.com. August 5, 2013. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- Turner, Benjamin; Bowen, Kevin (2003). "Bringin' in the DOOM Clones". GameSpy. Archived from the original on January 27, 2012. Retrieved November 15, 2005.

- House, Michael L. "Chex Quest – Overview". allgame. Archived from the original on November 17, 2014. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- Gestalt (December 29, 1999). "Games of the Millennium". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- Martin, Alan (April 12, 2019). "21 years after being set, the world record for speedrunning Doom's first level has been bested". Trusted Reviews.

- Walker, Alex (April 8, 2019). "Insanely Difficult DOOM Record Beaten After 20 Years". Kotaku Australia.

- Hegyi, Adam (1992). "Player profile for Thomas "Panter" Pilger". Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 15, 2005.

- "C O M P E T – N". Doom.com.hr. Archived from the original on May 19, 2014. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

External links

- Doom at MobyGames

- Richard H. "Hank" Leukart, III (1994). "The "Official" Doom FAQ". Archived from the original on July 31, 2013. Retrieved November 15, 2005.