Eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

| Part of a series on |

| Organised labour |

|---|

|

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the 16th century Spain,[1] but the modern movement dates back to the Industrial Revolution in Britain, where industrial production in large factories transformed working life. At that time, the working day could range from 10 to 16 hours, the work week was typically six days a week and the use of child labour was common.[2][3] The first country that introduced the 8-hour work day by law for factory and fortification workers was Spain in 1593.[1] In contemporary era, it was established for all professions by the Soviet Union in 1917.[4]

History

Sixteenth century

In 1594, Philip II of Spain established an eight-hour work day by a royal edict known as Ordenanzas de Felipe II, or Ordinances of Philip II. This established:

Ley VI Que los obreros trabajen 8 horas al día repartidas como convenga.

Todos los obreros trabajaran ocho horas al día, cuatro á la mañana, y cuatro á la tarde en fortificaciones y fábricas, que se hicieren, repartidas á los tiempos más convenientes para librarse del rigor del sol, más o menos lo que á los ingenieros pareciere, de forma que no faltando un punto de lo posible, también se atienda à procurar su salud y conservación.

Law VI That the workers work eight hours a day distributed as appropriate.

All the workers will work eight hours a day, four in the morning, and four in the afternoon in fortifications and factories, which [The hours] are to be made, distributed at the most convenient times to get rid of the rigor of the sun, [and] more or less what seems to [be right to] the engineers, so that not missing a point of the possible [work], it is also attended to ensure their health and conservation.

— Recopilación de leyes de los reinos de las indias. Mandadas a Imprimir y Publicar por la majestad católica del rey Don Carlos II, nuestro señor. Libro Tercero.[5]

An exception was applied to mine workers, whose work day was limited to seven hours. These working conditions were also applied to natives in the Spanish America, who also kept their own legislation organized in "Indian republics" where they elected their own mayors.[1]

Industrial revolution

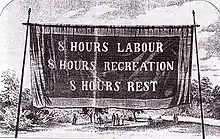

In the early 19th century, Robert Owen raised the demand for a ten-hour day in 1810, and instituted it in his "socialist" enterprise at New Lanark. By 1817 he had formulated the goal of the eight-hour day and coined the slogan: "Eight hours' labour, Eight hours' recreation, Eight hours' rest". Women and children in England were granted the ten-hour day in 1847. French workers won the 12-hour day after the February Revolution of 1848.[6]

A shorter working day and improved working conditions were part of the general protests and agitation for Chartist reforms and the early organisation of trade unions. There were initial successes in achieving an eight-hour day in New Zealand and by the Australian labour movement for skilled workers in the 1840s and 1850s, though most employed people had to wait to the early and mid twentieth century for the condition to be widely achieved through the industrialised world through legislative action.

The International Workingmen's Association took up the demand for an eight-hour day at its Congress in Geneva in 1866, declaring "The legal limitation of the working day is a preliminary condition without which all further attempts at improvements and emancipation of the working class must prove abortive", and "The Congress proposes eight hours as the legal limit of the working day." Karl Marx saw it as of vital importance to the workers' health, writing in Das Kapital (1867): "By extending the working day, therefore, capitalist production...not only produces a deterioration of human labour power by robbing it of its normal moral and physical conditions of development and activity, but also produces the premature exhaustion and death of this labour power itself."[7][8]

On 17 November 1915 Uruguay adopted an eight-hour working day, under the government of José Batlle y Ordóñez.[9] Nevertheless, the law was not effective on all type of works. On 3 April 1919, Spain introduced a universal law effective on all type of works, restricting the workday to a maximum of eight hours. The "Real decreto de 3 de abril de 1919" was signed by the prime minister, Álvaro de Figueroa, 1st Count of Romanones. The first international treaty to mention it was the Treaty of Versailles in the annex of its thirteenth part establishing the International Labour Office, now the International Labour Organization.[10]

The eight-hour day was the first topic discussed by the International Labour Organization which resulted in the Hours of Work (Industry) Convention, 1919 ratified by 52 countries as of 2016. The eight-hour day movement forms part of the early history for the celebration of May Day, and Labour Day in some countries.

Asia

Iran

In Iran in 1918, the work of reorganizing the trade unions began in earnest in Tehran during the closure of the Iranian constitutional parliament Majles. The printers' union, established in 1906 by Mohammad Parvaneh as the first trade union, in the Koucheki print shop on Nasserieh Avenue in Tehran, reorganized their union under leadership of Russian-educated Seyed Mohammad Dehgan, a newspaper editor and an avowed Communist. In 1918, the newly organised union staged a 14-day strike and succeeded in reaching a collective agreement with employers to institute the eight-hours day, overtime pay, and medical care. The success of the printers' union encouraged other trades to organize. In 1919 the bakers and textile-shop clerks formed their own trade unions.

However the eight-hours day only became as code by a limited governor's decree on 1923 by the governor of Kerman, Sistan and Balochistan, which controlled the working conditions and working hours for workers of carpet workshops in the province. In 1946 the council of ministers issued the first labor law for Iran, which recognized the eight-hour day.

Japan

The first company to introduce an eight-hour working day in Japan was the Kawasaki Dockyards in Kobe (now the Kawasaki Shipbuilding Corporation). An eight-hour day was one of the demands presented by the workers during pay negotiations in September 1919. After the company resisted the demands, a slowdown campaign was commenced by the workers on 18 September. After ten days of industrial action, company president Kōjirō Matsukata agreed to the eight-hour day and wage increases on 27 September, which became effective from October. The effects of the action were felt nationwide and inspired further industrial action at the Kawasaki and Mitsubishi shipyards in 1921.[11]

The eight-hour day did not become law in Japan until the passing of the Labor Standards Act in April 1947. Article 32 (1) of the Act specifies a 40-hour week and paragraph (2) specifies an eight-hour day, excluding rest periods.[12]

Indonesia

In Indonesia, the first policy regarding working time regulated in Law No. 13 of 2003 about employment. In the law, it stated that a worker should work for 7 hours a day for 6 days a week or 8 hours a day for 5 days a week, excluding rest periods.[13]

China

In China, the first company to introduce the eight-hour working day was the Baocheng Cotton Mill in the port city of Tianjin (Chinese: 天津市寶成紗廠). Its manager Wu Jingyi (Chinese: 吳鏡儀) announced on 16 February 1930 through Ta Kung Pao that his factory starting the new 8-hour work schedule immediately. The workers were elated. The union representative Liu Dongjiang (Chinese: 劉東江) stated "Under the spirit of cooperation, laborers and factory owners work together to advance the business, and in turn to contribute to our nation’s development." A celebration was held on the same day in the courtyard of the factory.

The new schedule was called "3–8 schedule". The first shift worked 6 am – 2 pm; the 2nd shift 2 pm – 10 pm; the 3rd shift 10 pm – 6 am. Manager Wu Jingyi reasoned: “All of the factories now have a 12-hour work schedule. Workers are all exhausted and do not have time to take care of their families. In case of workers getting sick, the business also suffers. Therefore we decided to start trying the eight-hour working day”.

The Beiyang government in Beijing had issued a decree “Provisional Regulations for factories” as early as in 1923, stating “Child-laborers shall not work more than 8 hours per day and shall have 3 days of rest per week; while adult laborers shall not work more than 10 hours per day and shall have 2 days of rest per week.” After the successful Northern Expedition, the new Nanking government established the Bureau of Labor in 1928, followed by issuing the “Factory Law” in 1929 to set legal framework for the eight-hour working day. Yet, no business actually implemented this until 1930 by Baocheng Cotton Mill.[14][15]

Europe

Belgium

The eight-hour work day was introduced in Belgium on 9 September 1924.

Denmark

The eight-hour work day was introduced by law in Denmark on 17 May 1919, after a year-long campaign by workers.[16]

Czechoslovakia

As a result of large-scale demonstrations and strikes in the late 19th and early 20th century, the former Czechoslovakia, now Czechia and Slovakia, introduced the eight-hour workday on 19 December 1918.[17]

Finland

The eight-hour work day was first introduced in Finland in 1923. Within the next few decades, the 8-hour system spread gradually across technically all branches of work. A worker receives 150% payment from the first two extra hours, and 200% salary if the work day exceeds 10 hours.

France

The eight-hour day was enacted in France by Georges Clemenceau, as a way to avoid unemployment and diminish communist support. It was succeeded by a strong French support of it during the writing of the International Labour Organization Convention of 1919.[18]

Germany

The first German company to introduce the eight-hour day was Degussa in 1884. The eight-hour day was signed into law during the German Revolution of 1918 by the new Social Democratic government. The eight-hour day was a concession to the workers' and soldiers' soviets, and was unpopular among industrialists. A 12-hour day was reintroduced by a right-wing government during the occupation of the Ruhr and subsequent hyperinflation crisis in 1923. The Labour Ministry eventually shortened wages in the late 1920s.[19]

Hungary

In Hungary, the eight-hour work day was introduced on 14 April 1919 by decree of the Revolutionary Governing Council.[20]

Italy

The eight-hour work day was introduced by law in Italy on 17 April 1925.

Poland

In Poland, the eight-hour day was introduced 23 November 1918 by decree of the cabinet of the Prime Minister Jędrzej Moraczewski.[21]

Portugal

In Portugal a vast wave of strikes occurred in 1919, supported by the National Workers' Union, the biggest labour union organisation at the time. The workers achieved important objectives, including the historic victory of an eight-hour day.

USSR (Soviet Union)

In the Soviet Union, the eight-hour day was introduced four days after the October Revolution, by a Decree of the Soviet government in 1917[4] and later in 1928[22] and 1940–1957 (World War II).[23]

Spain

In the region of Alcoy, a workers strike in 1873 for the eight-hour day followed much agitation from the anarchists. In 1919 in Barcelona, after a 44-day general strike with over 100,000 participants had effectively crippled the Catalan economy, the Government settled the strike by granting all the striking workers demands that included an eight-hour day, union recognition, and the rehiring of fired workers. Therefore, Spain became on 3 April 1919 the first country in the world to introduce a universal law effective on all type of works, restricting the workday to a maximum of eight hours: "Real decreto de 3 de abril de 1919", signed by the prime minister, Álvaro de Figueroa, 1st Count of Romanones.

Sweden

The eight-hour work day was introduced in Sweden on 4 August 1919. At the time, the work week was 48-hour since Saturday was a workday. The year before, 1918, the builders’ union had pushed through a 51-hour work week.[24]

United Kingdom

Procrustes. "Now then, you fellows; I mean to fit you all to my little bed!"

Chorus. "Oh lor-r!!"

"It is impossible to establish universal uniformity of hours without inflicting very serious injury to workers." – Motion at the recent Trades' Congress.

Cartoon from Punch, Vol 101, 19 September 1891

The Factory Act of 1833 limited the work day for children in factories. Those aged 9–13 could work only eight hours, 14–18 12 hours. Children under 9 were required to attend school.

In 1884, Tom Mann joined the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) and published a pamphlet calling for the working day to be limited to eight hours. Mann formed an organisation, the Eight Hour League, which successfully pressured the Trades Union Congress to adopt the eight-hour day as a key goal. The British Fabian socialist economist Sidney Webb and the scholar Harold Cox co-wrote a book supporting the "Eight Hours Movement" in Britain.[25]

The first group of Workers to achieve the 8-hour day were the Beckton [East London] Gas workers after the strike under the leadership of Will Thorne, a member of the Social Democratic Federation. The strike action was initiated on 31 March 1889 after the introduction of compulsory 18-hour shifts, up from the previous 12 hours. Under the slogan of "shorten our hours to prolong our lives" the strike spread to other gas works. He petitioned the bosses and after a strike of some weeks, the bosses capitulated and three shifts of 8 hours replaced two shifts of 12 hours. Will Thorne founded the Gas Workers and General Labourers Union, which evolved into the modern GMB union.

Working hours in the UK are currently not limited by day, but by week, as first set by the Working Time Regulations 1998,[26] which introduced a limit of 40 hours per week for workers under 18, and 48 hours per week for over 18s. This was in line with the European Commission Working Time Directive of 1993. UK regulations now follow the EC Working Time Directive of 2003, but workers can voluntarily opt out[27] of the 48 hour limit. A general 8 hour limit to the working day has never been achieved in the UK. By the end of the 20th century, many people considered themselves to be "money-rich, time-poor".

North America

Canada

The labour movement in Canada tracked progress in the US and UK. In 1890, the Federation of Labour took up this issue, hoping to organise participation in May Day.[28] In the 1960s, Canada adopted the 40-hour work week.[29]

Mexico

The Mexican Revolution of 1910—1920 produced the Constitution of 1917, which contained Article 123 that gave workers the right to organise labour unions and to strike. It also provided protection for women and children, the eight-hour day, and a living wage. See Mexican labor law.

United States

In the United States, Philadelphia carpenters went on strike in 1791 for the ten-hour day. By the 1830s, this had become a general demand. In 1835, workers in Philadelphia organised the first general strike in North America, led by Irish coal heavers. Their banners read, From 6 to 6, ten hours work and two hours for meals.[30] Labor movement publications called for an eight-hour day as early as 1836. Boston ship carpenters, although not unionized, achieved an eight-hour day in 1842.

In 1864, the eight-hour day quickly became a central demand of the Chicago labor movement. The Illinois General Assembly passed a law in early 1867 granting an eight-hour day but it had so many loopholes that it was largely ineffective. A citywide strike that began on 1 May 1867 shut down the city's economy for a week before collapsing.

In August 1866, the National Labor Union at Baltimore passed a resolution that said, "The first and great necessity of the present to free labor of this country from capitalist slavery, is the passing of a law by which eight hours shall be the normal working day in all States of the American Union. We are resolved to put forth all our strength until this glorious result is achieved."

On 25 June 1868, Congress passed an eight-hour law for federal employees[31][32] which was also of limited effectiveness. It established an eight-hour workday for laborers and mechanics employed by the Federal Government. President Andrew Johnson had vetoed the act but it was passed over his veto. Johnson told a Workingmen's Party delegation that he couldn't directly commit himself to an eight-hour day, he nevertheless told the same delegation that he greatly favored the "shortest number of hours consistent with the interests of all." According to Richard F. Selcer, however, the intentions behind the law were "immediately frustrated" as wages were cut by 20%.[33]

On 19 May 1869, President Ulysses S. Grant issued a National Eight Hour Law Proclamation.[34]

During the 1870s, eight hours became a central demand, especially among labor organizers, with a network of Eight-Hour Leagues which held rallies and parades. A hundred thousand workers in New York City struck and won the eight-hour day in 1872, mostly for building trades workers. In Chicago, Albert Parsons became recording secretary of the Chicago Eight-Hour League in 1878, and was appointed a member of a national eight-hour committee in 1880.

At its convention in Chicago in 1884, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions resolved that "eight hours shall constitute a legal day's labor from and after May 1, 1886, and that we recommend to labour organizations throughout this jurisdiction that they so direct their laws as to conform to this resolution by the time named."

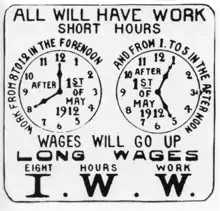

The leadership of the Knights of Labor, under Terence V. Powderly, rejected appeals to join the movement as a whole, but many local Knights assemblies joined the strike call including Chicago, Cincinnati and Milwaukee. On 1 May 1886 Albert Parsons, head of the Chicago Knights of Labor, led 80,000 people down Michigan Avenue in Chicago in what is regarded as the first modern May Day Parade, with the cry, "Eight-hour day with no cut in pay." In the next few days they were joined nationwide by 350,000 workers who went on strike at 1,200 factories, including 70,000 in Chicago, 45,000 in New York, 32,000 in Cincinnati, and additional thousands in other cities. Some workers gained shorter hours (eight or nine) with no reduction in pay; others accepted pay cuts with the reduction in hours.

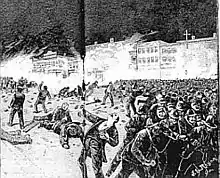

On 3 May 1886 August Spies, editor of the Arbeiter-Zeitung (Workers Newspaper), spoke at a meeting of 6,000 workers, and afterwards many of them moved down the street to harass strikebreakers at the McCormick plant in Chicago. The police arrived, opened fire, and killed four people, wounding many more. At a subsequent rally on 4 May to protest this violence, a bomb exploded at the Haymarket Square. Hundreds of labor activists were rounded up and the prominent labor leaders arrested, tried, convicted, and executed giving the movement its first martyrs. On 26 June 1893 Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld set the remaining leader free, and granted full pardons to all those tried claiming they were innocent of the crime for which they had been tried and the hanged men had been the victims of "hysteria, packed juries and a biased judge".

The American Federation of Labor, meeting in St Louis in December 1888, set 1 May 1890 as the day that American workers should work no more than eight hours. The International Workingmen's Association (Second International), meeting in Paris in 1889, endorsed the date for international demonstrations, thus starting the international tradition of May Day.

The United Mine Workers won an eight-hour day in 1898.

The Building Trades Council (BTC) of San Francisco, under the leadership of P. H. McCarthy, won the eight-hour day in 1900 when the BTC unilaterally declared that its members would work only eight hours a day for $3 a day (adjusted for inflation: $97.97 as of 2021). When the mill resisted, the BTC began organising mill workers; the employers responded by locking out 8,000 employees throughout the Bay Area. The BTC, in return, established a union planing mill from which construction employers could obtain supplies – or face boycotts and sympathy strikes if they did not. The mill owners went to arbitration, where the union won the eight-hour day, a closed shop for all skilled workers, and an arbitration panel to resolve future disputes. In return, the union agreed to refuse to work with material produced by non-union planing mills or those that paid less than the Bay Area employers.

By 1905, the eight-hour day was widely installed in the printing trades – see International Typographical Union § Fight for better working conditions – but the vast majority of Americans worked 12- to 14-hour days.

In the 1912 Presidential Election Teddy Roosevelt's Progressive Party campaign platform included the eight-hour work day.

On 5 January 1914 the Ford Motor Company took the radical step of doubling pay to $5 a day (adjusted for inflation: $129.55 as of 2020) and cut shifts from nine hours to eight, moves that were not popular with rival companies, although seeing the increase in Ford's productivity, and a significant increase in profit margin (from $30 million to $60 million in two years), most soon followed suit.[35][36][37]

In the summer of 1915, amid increased labor demand for World War I, a series of strikes demanding the eight-hour day began in Bridgeport, Connecticut. They were so successful that they spread throughout the Northeast.[38]

The United States Adamson Act in 1916 established an eight-hour day, with additional pay for overtime, for railroad workers. This was the first federal law that regulated the hours of workers in private companies. The United States Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Act in Wilson v. New, 243 U.S. 332 (1917).

The eight-hour day might have been realized for many working people in the US in 1937, when what became the Fair Labor Standards Act (29 U.S. Code Chapter 8) was first proposed under the New Deal. As enacted, the act applied to industries whose combined employment represented about twenty percent of the US labor force. In those industries, it set the maximum workweek at 40 hours,[39] but provided that employees working beyond 40 hours a week would receive additional overtime bonus salaries.[40]

Puerto Rico

In Puerto Rico in May 1899, while under US administration, General George W. Davis acceded to Island demands and decreed freedom of assembly, speech, press, religion and an eight-hour day for government employees.

Australia and New Zealand

Australia

The Australian gold rushes attracted many skilled tradesmen to Australia. Some of them had been active in the Chartist movement in Britain, and subsequently became prominent in the campaign for better working conditions in the Australian colonies. Workers began winning an eight-hour day in various companies and industries in the 1850s.

The Stonemasons' Society in Sydney issued an ultimatum to employers on 18 August 1855 saying that after six months masons would work only an eight-hour day. Due to the rapid increase in population caused by the gold rushes, many buildings were being constructed, so skilled labour was scarce. Stonemasons working on the Holy Trinity Church and the Mariners' Church (an evangelical mission to seafarers), decided not to wait and pre-emptively went on strike, thus winning the eight-hour day. They celebrated with a victory dinner on 1 October 1855 which to this day is celebrated as a Labour Day holiday in the state of New South Wales. When the six-month ultimatum expired in February 1856, stonemasons generally agitated for a reduction of hours. Although opposed by employers, a two-week strike on the construction of Tooth's Brewery on Parramatta Road proved effective, and stonemasons won an eight-hour day by early March 1856, but with a reduction in wages to match.[41]

Agitation was also occurring in Melbourne where the craft unions were more militant. Stonemasons working on Melbourne University organised to down tools on 21 April 1856 and march to Parliament House with other members of the building trade. The movement in Melbourne was led by veteran Chartists, and masons James Stephens, T.W. Vine and James Galloway. The government agreed that workers employed on public works should enjoy an eight-hour day with no loss of pay and stonemasons celebrated with a holiday and procession on Monday 12 May 1856, when about 700 people marched with 19 trades involved. By 1858, the eight-hour day was firmly established in the building industry and by 1860, the eight-hour day was fairly widely worked in Victoria. From 1879, the eight-hour day was a public holiday in Victoria. The initial success in Melbourne led to the decision to organise a movement, to actively spread the eight-hour idea, and secure the condition generally.

In 1903, veteran socialist Tom Mann spoke to a crowd of a thousand people at the unveiling of the Eight Hour Day monument, funded by public subscription, on the south side of Parliament House on Spring St. It was relocated in 1923 to the corner of Victoria and Russell Streets outside Melbourne Trades Hall.

It took further campaigning and struggles by trade unions to extend the reduction in hours to all workers in Australia. In 1916 the Victoria Eight Hours Act was passed granting the eight-hour day to all workers in the state. The eight-hour day was not achieved nationally until the 1920s. The Commonwealth Arbitration Court gave approval of the 40-hour five-day working week nationally beginning on 1 January 1948. The achievement of the eight-hour day has been described by historian Rowan Cahill as "one of the great successes of the Australian working class during the nineteenth century, demonstrating to Australian workers that it was possible to successfully organise, mobilise, agitate, and exercise significant control over working conditions and quality of life. The Australian trade union movement grew out of eight-hour campaigning and the movement that developed to promote the principle."

The intertwined numbers 888 soon adorned the pediment of many union buildings around Australia. The Eight Hour March, which began on 21 April 1856, continued each year until 1951 in Melbourne, when the conservative Victorian Trades Hall Council decided to forgo the tradition for the Moomba festival on the Labour Day weekend. In capital cities and towns across Australia, Eight Hour day marches became a regular social event each year, with early marches often restricted to those workers who had won an eight-hour day.

New Zealand

Promoted by Samuel Duncan Parnell as early as 1840, when carpenter Samuel Parnell refused to work more than eight hours a day when erecting a store for merchant George Hunter. He successfully negotiated this working condition and campaigned for its extension in the infant Wellington community. A meeting of Wellington carpenters in October 1840 pledged "to maintain the eight-hour working day, and that anyone offending should be ducked into the harbour".

Parnell is reported to have said: "There are twenty-four hours per day given us; eight of these should be for work, eight for sleep, and the remaining eight for recreation and in which for men to do what little things they want for themselves." With tradesmen in short supply the employer was forced to accept Parnell's terms. Parnell later wrote, "the first strike for eight hours a day the world has ever seen, was settled on the spot".[42][43]

Emigrants to the new settlement of Dunedin, Otago, while on board ship decided on a reduction of working hours. When the resident agent of the New Zealand Company, Captain Cargill, attempted to enforce a ten-hour day in January 1849 in Dunedin, he was unable to overcome the resistance of trades people under the leadership of house painter and plumber, Samuel Shaw. Building trades in Auckland achieved the eight-hour day on 1 September 1857 after agitation led by Chartist painter, William Griffin. For many years the eight-hour day was confined to craft tradesmen and unionised workers. Labour Day, which commemorates the introduction of the eight-hour day, became a national public holiday in 1899.

South America

A strike for the eight-hour day was held in May 1919 in Peru. In Uruguay, the eight-hour day was put in place in 1915 of several reforms implemented during the second term of president José Batlle y Ordóñez. It was introduced in Chile on 8 September 1924 at the demand of then-general Luis Altamirano as part of the Ruido de sables that culminated in the September Junta.

See also

- 996 working hour system

- Effects of overtime

- Flextime

- Four-day workweek

- Haymarket riot

- Right to rest and leisure

- Right to work

- Six-hour day

- Work–life interface

- Working time

References

- Boix Blay, Ignacio (1841) [1573]. Ignacio Boix Blay (ed.). Recopilación de leyes de los reinos de las indias. Mandadas a Imprimir y Publicar por la majestad católica del rey Don Carlos II, nuestro señor. Libro Tercero [Compilation of laws of the kingdoms of the Indians. Sent to Print and Publish by the Catholic Majesty of King Carlos II, our Lord. Third Book.] (Google Books) (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

References

- Cervera, César (8 May 2019). "La jornada de ocho horas: ¿un invento "sindicalista" del Rey Felipe II?" [The eight-hour day: a "unionist" invention of King Philip II?]. www.abc.es (in Spanish). ABC. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- Chase, Eric. "The Brief Origins of May Day". Industrial Workers of the World. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- "The Haymarket Martyrs". The Illinois Labor History Society. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- "Decree on the Hours of Labor". www.marxists.org.

- Boix Blay 1841, p. 37.

- Marx, Karl (1915). Capital: The process of capitalist production. Translated by Samuel Moore, Edward Bibbins Aveling, and Ernest Untermann. C. H. Kerr. p. 328.

- Marx, Karl (1867). Das Kapital. p. 376.

- Neocleous, Mark. "The Political Economy of the Dead: Marx's Vampires" (PDF). Brunel University. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- "Imágenes del Diario Oficial". www.impo.com.uy.

- s: Constitution of the International Labour Office

- "8時間労働発祥の地神戸" [Kobe: Birthplace of the Eight-Hour Day] (in Japanese). City of Kobe. 6 April 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- "Labor Standards Act". Ministry of Justice (Japan). 11 December 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- "UNDANG-UNDANG REPUBLIK INDONESIA NOMOR 13 TAHUN 2003 TENTANG KETENAGAKERJAAN" (PDF).

- "个人择业与社会责任:武进吴氏昆季生平事迹考述-常州大学学报(社会科学版)". xuebaoskb.cczu.edu.cn.

- "纱厂工人先受益 一天只干八小时". 记者 孙薇/城市快报.

- "17. Maj 1919 - Otte timers arbejdsdag | Arbejderen". Archived from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- "Osmihodinovou pracovní dobu přijalo Československo před sto lety". Radio Prague International (in Czech). 18 December 2018. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- "La loi des huit heures : Un projet d'Europe sociale ? (1918-1932)". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- Weitz, Eric D. (1 September 2007), "Weimar Germany and the Dilemmas of Liberty", The Routledge History of the Holocaust, Routledge, doi:10.4324/9780203837443.ch5, ISBN 978-0-203-83744-3, retrieved 5 November 2021

- "Az ipari munkások munkabérének ideiglenes megállapítása. A Forradalmi Kormányzótanács LXIV. számú rendelete" [Temporary determination of the industrial workers' wages. Decree No. 64 of the Revolutionary Governing Council.]. A Forradalmi Kormányzótanács és a népbiztosságok rendeletei [Decrees of the Revolutionary Governing Council and the people's commissariats] (in Hungarian). Szocialista-Kommunista Munkások Magyarországi Pártja. 2: 32–33. 1919.

- "Dekret o 8-mio godzinnym dniu pracy - Wikiźródła, wolna biblioteka". pl.wikisource.org.

- "Постановление СНК СССР от 17 января 1928 года «О подготовке введения 7-часового рабочего дня» — Викитека". ru.wikisource.org.

- "Указ Президиума ВС СССР от 26.06.1940 о переходе на восьмичасовой рабочий день, на семидневную рабочую неделю …/Исходная редакция — Викитека". ru.wikisource.org.

- Åmark, Klas (1989). Maktkamp i byggbransch : avtalsrörelser och konflikter i byggbranschen 1914–1920. Lund. ISBN 91-7924-048-8.

- Sidney Webb. The eight hours day. Open Library. OL 25072899M.

- "The Working Time Regulations 1998".

- "Maximum weekly working hours". GOV.UK.

- "The New Canadian Ship Railway". Hardware. 10 January 1890. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- "Hours of labour". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 1, From Colonial Times to the Founding of The American Federation of Labor, International Publishers, 1975, pages 116–118

- "United States v. Martin – 94 U.S. 400 (1876) :: Justia US Supreme Court Center". Supreme.justia.com. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- "336 U.S. 281". Ftp.resource.org. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- Richard F. Selcer (2006). Civil War America, 1850 To 1875. Infobase Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 9781438107974.

- "The Lines are Drawn". Chicagohistory.org. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- New York Times "[Ford] Gives $10,000,000 To 26,000 Employees", The New York Times, 5 January 1914, accessed 23 April 2011.

- Ford Motor Company "Henry Ford's $5-a-Day Revolution" Archived 6 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Ford, 5 January 1914, accessed 23 April 2011.

- Byron Preiss Visual Publications, Inc. "Ford: Doubling the profit from 1914–1916", Hispanic Pundit, 1996, accessed 24 April 2011.

- Philip Sheldon Foner (1982). History of the Labor Movement in the United States: 1915–1916, on the Eve of America's Entrance into World War I, Vol. 6. International Publishers Company, Incorporated. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-7178-0595-2.

[A] ten-hour center like Bridgeport was converted overnight into an eight-hour community, a result that ten years of agitation under normal conditions might not have accomplished.

- Jonathan Grossman (June 1978). "Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938: Maximum Struggle for a Minimum Wage". Monthly Labor Review. US Department of Labor. Archived from the original on 15 August 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- "National Fair Labor Standards Act". Chron. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- Cahill, Rowan. "The Eight Hour Day and the Holy Spirit". Workers Online. Labor Council of N.S.W. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- Roth, Bert. "Samuel Duncan Parnell". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- Bert Roth (1966). "Eight-Hour-Day Movement (in New Zealand)". Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

Further reading

- John Child, Unionism and the Labor Movement. 1971.

- Bob James, Anarchism and State Violence in Sydney and Melbourne 1886–1896. 1986.

- Habib Ladjevardim, Labor Unions and Autocracy in Iran, 1985.

- Andy McInerney, May Day, The Workers' Day, Born in the Struggle for the Eight-hour Day, Liberation & Marxism, no. 27 (Spring 1996).

- Brian McKinley (ed), A Documentary History of the Australian Labor Movement 1850 – 1975. 1979.

- William A. Mirola, Redeeming Time: Protestantism and Chicago's Eight-Hour Movement, 1866–1912. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2015.

- Mayday: A Short History of 100 Years of May Day, 1890–1990 Melbourne May Day Committee, 1990.

- David R. Roediger & Philip S. Foner “Our Own Time: A History of American Labor and the Working Day,” Verso Books, New York, 1989.

External links

- The Eight Hour Day and the Holy Spirit by Rowan Cahill

- Eight Hour Day in Australia Union Songs site

- Eight hour day medals from Museum Victoria

- 150th anniversary commemorative website

New Zealand

- Eight-hour-day Movement in New Zealand Encyclopedia of New Zealand (1966)

- Origins of Labour Day in New Zealand

United States

- Early IWW struggles

- Eight-Hour Movement Encyclopedia of Chicago

- Oastler's Letter Shocked England