Emo

Emo /ˈiːmoʊ/ is a rock music genre characterized by emotional, often confessional lyrics. It emerged as a style of post-hardcore and hardcore punk from the mid-1980s Washington D.C. hardcore punk scene, where it was known as emotional hardcore or emocore and pioneered by bands such as Rites of Spring and Embrace. In the early–mid 1990s, emo was adopted and reinvented by alternative rock, indie rock and/or punk rock bands such as Sunny Day Real Estate, Jawbreaker, Weezer, Cap'n Jazz, and Jimmy Eat World. By the mid-1990s, bands such as Braid, the Promise Ring, and the Get Up Kids emerged from the burgeoning Midwest emo scene, and several independent record labels began to specialize in the genre. Meanwhile, screamo, a more aggressive style of emo using screamed vocals, also emerged, pioneered by the San Diego bands Heroin and Antioch Arrow. Screamo achieved mainstream success in the 2000s with bands like Hawthorne Heights, Silverstein, Story of the Year, Thursday, the Used, and Underoath.

| Emo | |

|---|---|

| Other names |

|

| Stylistic origins |

|

| Cultural origins |

|

| Subgenres | |

| |

| Fusion genres | |

| |

| Regional scenes | |

| |

| Other topics | |

| Scene | |

Often seen as a subculture, emo also signifies a specific relationship between fans and artists and certain aspects of fashion, culture and behavior. Emo fashion has been associated with skinny jeans, black eyeliner, tight t-shirts with band names, studded belts, and flat, straight, jet-black hair with long bangs. Since the early to mid 2000s, fans of emo music who dress like this are referred to as "emo kids" or "emos" and known for listening to bands like My Chemical Romance, Fall Out Boy, Hawthorne Heights, The Used, and AFI. The emo subculture was stereotypically associated with social alienation, sensitivity, misanthropy, introversion and angst. Purported links to depression, self-harm and suicide, combined with its rise in popularity in the early 2000s, inspired a backlash against emo, with bands such as My Chemical Romance and Panic! at the Disco rejecting the emo label because of the social stigma and controversy surrounding it.

Emo and its subgenre emo pop entered mainstream culture in the early 2000s with the success of Jimmy Eat World and Dashboard Confessional and many artists signed to major record labels. Bands such as My Chemical Romance, AFI, Fall Out Boy and the Red Jumpsuit Apparatus continued the genre's popularity during the rest of the decade. By the early 2010s, emo's popularity had declined, with some groups changing their sound and others disbanding. Meanwhile, however, a mainly underground emo revival emerged, with bands such as The World Is a Beautiful Place & I Am No Longer Afraid to Die and Modern Baseball, some drawing on the sound and aesthetic of 1990s emo. During the late 2010s, a fusion genre called emo rap was mainstream, with some of emo rap's most famous artists including Lil Peep, XXXTentacion and Juice Wrld.

Characteristics

Emo originated in hardcore punk[1][2] and is considered a form of post-hardcore.[3] Nonetheless, emo has also been considered a genre of alternative rock,[4] indie rock,[5] punk rock[6] and pop punk.[7][8] Emo uses the guitar dynamics that use both the softness and loudness of punk rock music.[9] Some emo leans uses characteristics of progressive music with the genre's use of complex guitar work, unorthodox song structures, and extreme dynamic shifts.[1]

Lyrics, a focus in emo music, are typically emotional and often personal or confessional,[9] dealing with topics such as failed romance,[10] self-loathing, pain, insecurity, suicidal thoughts, love, and relationships.[9] AllMusic described emo lyrics as "usually either free-associative poetry or intimate confessionals".[1] Early emo bands were hardcore punk bands that used melody and emotional or introspective lyrics and that were less structured than regular hardcore punk, making early emo bands different from the aggression, anger, and verse-chorus-verse structures of regular hardcore punk.[11]

According to AllMusic, most 1990s emo bands "borrowed from some combination of Fugazi, Sunny Day Real Estate, and Weezer".[1] The New York Times described emo as "emotional punk or post-hardcore or pop-punk. That is, punk that wears its heart on its sleeve and tries a little tenderness to leaven its sonic attack. If it helps, imagine Ricky Nelson singing in the Sex Pistols."[12] Author Matt Diehl called emo a "more sensitive interpolation of punk's mission".[10] According to Merriam-Webster, emo is "a style of rock music influenced by punk rock and featuring introspective and emotionally fraught lyrics".[13]

History

Predecessors

Pet Sounds, the Beach Boys' 1966 album, is sometimes considered the first emo album. According to music writer Luke Britton, such assertions are perhaps stated "wryly", and wrote that "it’s generally accepted that the genre's pioneers" came later in the 1980s.[14] During the decade, many hardcore punk and post-hardcore bands formed in Washington, D.C. Post-hardcore, an experimental offshoot of hardcore punk, was inspired by post-punk.[15] Hardcore punk bands and post-hardcore bands who influenced early emo bands include Minor Threat,[16] Black Flag and Hüsker Dü.[17]

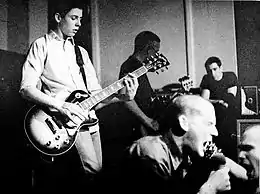

1984–1991: Origins

Emo, which began as a post-hardcore subgenre,[3] was part of the 1980s hardcore punk[1] scene in Washington, D.C. as something different from the violent part of the Washington, D.C. hardcore scene.[11][18][19] Minor Threat fan Guy Picciotto formed Rites of Spring in 1984, using the musical style of hardcore punk and combining the musical style with melodic guitars, varied rhythms, and personal, emotional lyrics.[16] Many of the band's themes, including nostalgia, romantic bitterness and poetic desperation, became familiar tropes of later emo music.[20] Its performances were public, emotional purges where audience members sometimes wept.[21] Ian MacKaye of Minor Threat became a Rites of Spring fan (recording their only album and being their roadie) and formed the emo band Embrace, which explored similar themes of self-searching and emotional release.[22] Similar bands followed in connection with the "Revolution Summer” of 1985, an attempt by members of the Washington scene to break from the usual characteristics of hardcore punk to a hardcore punk style with different characteristics.[19] Bands such as Gray Matter, Beefeater, Fire Party, Dag Nasty, and Soulside were associated with the movement.[22][19]

Although the origins of the word "emo" are uncertain, evidence shows that the word "emo" was coined in the mid-1980s, specifically 1985. According to Andy Greenwald, author of Nothing Feels Good: Punk Rock, Teenagers, and Emo, "The origins of the term 'emo' are shrouded in mystery ... but it first came into common practice in 1985. If Minor Threat was hardcore, then Rites of Spring, with its altered focus, was emotional hardcore or emocore."[22] Michael Azerrad, author of Our Band Could Be Your Life, also traces the word's origins to the mid-1980s: "The style was soon dubbed 'emo-core,' a term everyone involved bitterly detested".[23] MacKaye traces it to 1985, attributing it to an article in Thrasher magazine referring to Embrace and other Washington, D.C. bands as "emo-core" (which he called "the stupidest fucking thing I've ever heard in my entire life").[24] Other accounts attribute the word to an audience member at an Embrace show, who shouted as an insult that the band was "emocore".[25][26] Others have said that MacKaye coined the word when he used it self-mockingly in a magazine, or that it originated with Rites of Spring.[26] The "emocore" label quickly spread through the DC punk scene, and was associated with many bands associated with Ian MacKaye's Dischord Records.[25] Although many of the bands rejected the term, it stayed. Jenny Toomey recalled, "The only people who used it at first were the ones that were jealous over how big and fanatical a scene it was. [Rites of Spring] existed well before the term did and they hated it. But there was this weird moment, like when people started calling music 'grunge,' where you were using the term even though you hated it."[27] The Washington, D.C. emo scene lasted only a few years, and by 1986, most of emo's major bands (including Rites of Spring, Embrace, Gray Matter and Beefeater) had broken up.[28] However, its ideas and aesthetics spread quickly across the country through a network of homemade zines, vinyl records and hearsay.[29] According to Greenwald, the Washington, D.C. scene laid the groundwork for emo's subsequent incarnations:

What had happened in D.C. in the mid-eighties—the shift from anger to action, from extroverted rage to internal turmoil, from an individualized mass to a mass of individuals—was in many ways a test case for the transformation of the national punk scene over the next two decades. The imagery, the power of the music, the way people responded to it, and the way the bands burned out instead of fading away—all have their origins in those first few performances by Rites of Spring. The roots of emo were laid, however unintentionally, by fifty or so people in the nation's capital. And in some ways, it was never as good and surely never as pure again. Certainly, the Washington scene was the only time "emocore" had any consensus definition as a genre.[30]

1991–1994: Reinvention

As the Washington, D.C. emo movement spread across the United States, local bands began to emulate its style.[31] Emo combined the fatalism, theatricality and isolation of The Smiths with hardcore punk's uncompromising, dramatic worldview.[31] Despite the number of bands and the variety of locales, emocore's late-1980s aesthetics remained more-or-less the same: "over-the-top lyrics about feelings wedded to dramatic but decidedly punk music."[31] During the early–mid 1990s, several new bands reinvented emo,[32] making emo expand by becoming a subgenre of genres like indie rock and pop punk.[1] Chief among them were Jawbreaker and Sunny Day Real Estate, who inspired cult followings, redefined emo and brought it a step closer to the mainstream.[32] In the wake of the 1991 success of Nirvana's Nevermind, underground music and subcultures were widely noticed in the United States. New distribution networks emerged, touring routes were codified, and regional and independent acts accessed the national stage.[32] Young people across the country became fans of independent music, and punk culture became mainstream.[32]

Emerging from the late 1980s and early 1990s San Francisco punk rock scene and forming in New York City, Jawbreaker combined pop punk with emotional and personal lyrics.[34][35][36] Singer-guitarist Blake Schwarzenbach focused his lyrics on personal, immediate topics often taken from his journal.[34] Often obscure and cloaked in metaphors, their relationship to Schwarzenbach's concerns gave his words a bitterness and frustration which made them universal and attractive to audiences.[37] Schwarzenbach became emo's first idol, as listeners related to the singer even more than to his songs.[37] Jawbreaker's 1994 album, 24 Hour Revenge Therapy, was popular with fans and is a touchstone of mid-1990s emo.[38] Although Jawbreaker signed with Geffen Records and toured with mainstream bands Nirvana and Green Day, Jawbreaker's 1995 album Dear You did not achieve mainstream success. Jawbreaker broke up soon afterwards, with Schwarzenbach forming emo band Jets to Brazil.[39]

Sunny Day Real Estate formed in Seattle at the height of the early-1990s grunge boom.[40] The music video for "Seven", lead track of the band's debut album Diary (1994), was played on MTV, giving the band more attention.[41] Another emo band which emerged at the same time was California's Weezer, which also released its self-titled debut album in 1994.[42] Also known as the Blue Album, Weezer's self-titled album was certified 2× platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) on August 8, 1995, and was certified 3× platinum by the RIAA on November 13, 1998. As of August 2009, Weezer's self-titled album sold at least 3,300,000 copies in the United States.[43] According to NME, Weezer's debut album "pretty much invented emo's melodic wing".[44] Jimmy Eat World, an Arizona emo band, also emerged at this time. Influenced by pop punk bands such as the Mr. T Experience and Horace Pinker,[45] Jimmy Eat World released its self-titled debut album in 1994.[46]

1994–1997: Underground popularity

The American punk and indie rock movements, which had been largely underground since the early 1980s, became part of mainstream culture during the mid-1990s. With Nirvana's success, major record labels capitalized on the popularity of alternative rock and other underground music by signing and promoting independent bands.[47] In 1994, the same year that Jawbreaker's 24 Hour Revenge Therapy and Sunny Day Real Estate's Diary were released, punk rock bands Green Day and the Offspring broke into the mainstream with diamond album Dookie[48] and 6× platinum album Smash,[49] respectively. After underground music went mainstream, emo retreated and reformed as a national subculture over the next few years.[47] Inspired by Jawbreaker, Drive Like Jehu and Fugazi, the new emo was a mixture of hardcore punk passion and indie-rock intelligence, with punk rock's anthemic power and do-it-yourself work ethic but smoother songs, sloppier melodies and yearning vocals.[50]

Many new emo bands, such as Cap'n Jazz, Braid, Christie Front Drive, Mineral, Jimmy Eat World, the Get Up Kids and the Promise Ring, originated in the central U.S.[51] Many of the bands had a distinct vocal style and guitar melodies, which was later called Midwest emo.[52] According to Andy Greenwald, "this was the period when emo earned many, if not all, of the stereotypes that have lasted to this day: boy-driven, glasses-wearing, overly sensitive, overly brainy, chiming-guitar-driven college music."[50] Emo band Texas Is the Reason bridged the gap between indie rock and emo in their three-year lifespan on the East Coast, melding Sunny Day Real Estate's melodies and punk musicianship and singing directly to the listener.[53] In New Jersey, the band Lifetime played shows in fans' basements.[54] Lifetime's 1995 album, Hello Bastards on Jade Tree Records, fused hardcore punk with emo and eschewed cynicism and irony in favor of love songs.[54] The album sold tens of thousands of copies,[55] and Lifetime paved the way for New Jersey and Long Island emo bands Brand New, Midtown,[56] The Movielife, My Chemical Romance,[56] Saves the Day,[56][57] Senses Fail,[56] Taking Back Sunday[55][56] and Thursday.[56][58]

The Promise Ring's music took a slower, smoother, pop punk approach to riffs, blending them with singer Davey von Bohlen's imagist lyrics delivered in a froggy croon and pronounced lisp and playing shows in basements and VFW halls.[60] Jade Tree released their debut album, 30° Everywhere, in 1996; it sold tens of thousands of copies and was successful by independent standards.[61] Greenwald describes the album as "like being hit in the head with cotton candy."[62] Other bands, such as Karate, the Van Pelt, Joan of Arc and the Shyness Clinic, played emo music with post-rock and noise rock influences.[63] Their common lyrical thread was "applying big questions to small scenarios."[63] A cornerstone of mid-1990s emo was Weezer's 1996 album, Pinkerton.[64] After the mainstream success of Weezer's self-titled debut album, Pinkerton showed a more dark and abrasive style.[65][66] Frontman Rivers Cuomo's songs focused on messy, manipulative sex and his insecurity about dealing with celebrity.[66] A critical and commercial failure,[66][67] Rolling Stone called it the second-worst album of the year.[68] Cuomo retreated from the public eye,[66] later referring to the album as "hideous" and "a hugely painful mistake".[69] However, Pinkerton found enduring appeal with young people who were discovering alternative rock and identified with its confessional lyrics and theme of rejection.[59] Sales grew steadily due to word of mouth, online message boards and Napster.[59] "Although no one was paying attention", writes Greenwald, "perhaps because no one was paying attention—Pinkerton became the most important emo album of the decade."[59] In 2004, James Montgomery of MTV described Weezer as "the most important band of the last 10 years".[70] Pinkerton's success grew very gradually, being certified gold by the RIAA in July 2001 and eventually being certified platinum by the RIAA in September 2016.[71]

Mid-1990s emo was embodied by Mineral, whose The Power of Failing (1997) and EndSerenading (1998) encapsulated emo tropes: somber music, accompanied by a shy narrator singing seriously about mundane problems.[72] Greenwald calls "If I Could" "the ultimate expression" of 1990s emo, writing that "the song's short synopsis—she is beautiful, I am weak, dumb, and shy; I am alone but am surprisingly poetic when left alone—sums up everything that emo's adherents admired and its detractors detested."[72] Another significant band was Braid, whose 1998 album Frame and Canvas and B-side song "Forever Got Shorter" blurred the line between band and listener; the group mirrored their audience in passion and sentiment, and sang in their fans' voice.[73]

Although mid-1990s emo had thousands of young fans, it did not enter the national consciousness.[75] A few bands were offered contracts with major record labels, but most broke up before they could capitalize on the opportunity.[76] Jimmy Eat World signed to Capitol Records in 1995 and developed a following with their album, Static Prevails, but did not break into the mainstream yet.[77] The Promise Ring were the most commercially successful emo band of the time, with sales of their 1997 album Nothing Feels Good reaching the mid-five figures.[75] Greenwald calls the album "the pinnacle of its generation of emo: a convergence of pop and punk, of resignation and celebration, of the lure of girlfriends and the pull of friends, bandmates, and the road";[78] mid-1990s emo was "the last subculture made of vinyl and paper instead of plastic and megabytes."[79]

1997–2002: Increased popularity

Emo's popularity grew during the late 1990s, laying the foundation for mainstream success. Deep Elm Records released a series of eleven compilation albums, The Emo Diaries, from 1997 to 2007.[80] Emphasizing unreleased music from many bands, the series included Jimmy Eat World, Further Seems Forever, Samiam and the Movielife.[80] Jimmy Eat World's 1999 album, Clarity, was a touchstone for later emo bands.[81] In 2003, Andy Greenwald called Clarity "one of the most fiercely beloved rock 'n' roll records of the last decade."[81] Despite a warm critical reception and the promotion of "Lucky Denver Mint" in the Drew Barrymore comedy Never Been Kissed, Clarity was commercially unsuccessful.[82] Nevertheless, the album had steady word-of-mouth popularity and eventually sold over 70,000 copies.[83] Jimmy Eat World self-financed their next album, Bleed American (2001), before signing with DreamWorks Records. The album sold 30,000 copies in its first week, went gold shortly afterwards and went platinum in 2002, making emo become mainstream.[84] Drive-Thru Records developed a roster of primarily pop punk bands with emo characteristics, including Midtown, the Starting Line, the Movielife and Something Corporate.[85] Drive-Thru's partnership with MCA Records enabled its brand of emo-inflected pop to reach a wider audience.[86] Drive-Thru's unabashedly populist, capitalist approach to music allowed its bands' albums and merchandise to sell in stores such as Hot Topic.[87]

.jpg.webp)

Independent label Vagrant Records signed several successful late-1990s and early-2000s emo bands. The Get Up Kids had sold over 15,000 copies of their debut album, Four Minute Mile (1997), before signing with Vagrant. The label promoted them aggressively, sending them on tours opening for Green Day and Weezer.[88] Their 1999 album, Something to Write Home About, reaching number 31 on Billboard's Top Heatseekers chart.[89] Vagrant signed and recorded a number of other emo-related bands over the next two years, including the Anniversary, Reggie and the Full Effect, the New Amsterdams, Alkaline Trio, Saves the Day, Dashboard Confessional, Hey Mercedes and Hot Rod Circuit.[90] Saves the Day had developed a substantial East Coast following and sold almost 50,000 copies of their second album, Through Being Cool (1999),[57] before signing with Vagrant and releasing Stay What You Are (2001). Stay What You Are sold 15,000 copies in its first week,[91] reached number 100 on the Billboard 200[92] and sold at least 120,000 copies in the United States.[93] The band Blink-182's song "Adam's Song" is considered an emo song.[94] The song, which is from Blink-182's 1999 5× platinum[95] album Enema of the State, peaked at number two on the Alternative Songs chart on April 29, 2000.[96] Vagrant organized a national tour with every band on its label, sponsored by corporations including Microsoft and Coca-Cola, during the summer of 2001. Its populist approach and use of the internet as a marketing tool made it one of the country's most-successful independent labels and helped popularize the word "emo".[97] According to Greenwald, "More than any other event, it was Vagrant America that defined emo to masses—mainly because it had the gumption to hit the road and bring it to them."[91] Weezer returned in the early 2000s with a pop music-influenced sound.[98] Cuomo refused to play songs from Pinkerton, calling it "ugly" and "embarrassing".[99] Weezer released their Green Album in 2001. The Green Album was described as emo pop by AllMusic[98] and the album was certified platinum by the RIAA on September 13, 2001.[100] As of August 2009, Weezer's Green Album has sold 1,600,000 copies.[43]

2002–2010: Mainstream

Emo broke into the mainstream media during the summer of 2002.[101] During this time, many fans of emo music had an appearance of short, dyed black hair with bangs cut high on the forehead, glasses with thick and black frames, and thrift store clothes. This fashion then became a huge part of emo's identity.[104] Jimmy Eat World's Bleed American album went platinum on the strength of "The Middle", which topped Billboard's Alternative Songs chart.[101][102][105] The mainstream success achieved by Jimmy Eat World paved the way for emo pop music that would appear during the rest of the 2000s,[98] with emo pop becoming a very common style of emo music during the 2000s.[106] The band Dashboard Confessional broke into the mainstream. Started by the band's guitarist and lead vocalist Chris Carrabba, Dashboard Confessional are known for sometimes creating acoustic songs.[107] Dashboard Confessional originally was a side project, as Carrabba was also a member of the emo band Further Seems Forever,[107] and Vacant Andys, a punk rock band Carraba helped start in 1995.[108] Dashboard Confessional's album The Places You Have Come to Fear the Most peaked at number 5 on the Independent Albums chart.[103] Dashboard Confessional was the first non-platinum-selling artist to record an episode of MTV Unplugged.[101] The 2002 resulting live album and video long-form was certified platinum by the RIAA on May 22, 2003, topped the Independent Albums chart, and, as of October 19, 2007, sold 316,000 copies.[103][107][109] With Dashboard Confessional's mainstream success, Carrabba appeared on a cover of the magazine Spin and according to Jim DeRogatis, "has become the 'face of emo' the way that Moby was deemed the prime exponent of techno or Kurt Cobain became the unwilling crown prince of grunge."[110] Three of Dashboard Confessional's studio albums, The Places You Have Come to Fear the Most (2001), A Mark, a Mission, a Brand, a Scar (2003), and Dusk and Summer (2006), all were certified gold by the RIAA during the mid-2000s.[109] As of October 19, 2007, The Places You Have Come to Fear the Most has sold 599,000 copies.[111] As of October 19, 2007, Dusk and Summer and A Mark, a Mission, a Brand, a Scar have sold 512,000 copies and 901,000 copies in the United States, respectively.[111] As of October 19, 2007, Dashboard Confessional's 2000 debut album The Swiss Army Romance sold 338,000 copies.[111] On August 10, 2003, The New York Times reported how, "from the three-chord laments of Alkaline Trio to the folky rants of Bright Eyes, from the erudite pop-punk of Brand New" to the entropic anthems of Thursday, much of the most exciting rock music" was appearing from the emo genre.[112]

Saves the Day toured with Green Day, Blink-182 and Weezer, playing in large arenas such as Madison Square Garden.[113] Saves the Day performed on Late Night with Conan O'Brien, appeared on the cover of Alternative Press and had music videos for "At Your Funeral" and "Freakish" in rotation on MTV2.[91][114] Taking Back Sunday released their debut album, Tell All Your Friends, on Victory Records in 2002. The album gave the band a taste of success in the emo scene with singles such as "Cute Without the 'E' (Cut from the Team)" and "You're So Last Summer". Tell All Your Friends was eventually certified gold by the RIAA in 2005[115] and is considered one of emo's most-influential albums. As of May 8, 2009, Tell All Your Friends sold 790,000 copies.[116] Articles on Vagrant Records appeared in Time and Newsweek,[117] and the word "emo" became a catchall term for non-mainstream pop music.[118]

In the wake of this success, many emo bands were signed to major record labels and the genre became marketable.[119] According to DreamWorks Records senior A&R representative Luke Wood, "The industry really does look at emo as the new rap rock, or the new grunge. I don't think that anyone is listening to the music that's being made—they're thinking of how they're going to take advantage of the sound's popularity at retail."[120] Emo's apolitical nature, catchy music and accessible themes had broad appeal for a young, mainstream audience. Emo bands that emerged or broke into the mainstream during this time were rejected by many fans of older emo music.[106] As emo continued to be mainstream, it became quite common for emo bands to have black hair and wear eyeliner.[106] Taking Back Sunday had continued success in the next few years, with their 2004 album Where You Want To Be both reaching number three on the Billboard 200 and being certified gold by the RIAA in July 2005.[121] The album, as of February 17, 2006, sold more than 700,000 copies in the United States, according to Nielsen SoundScan.[122] The band's 2006 album, Louder Now, reached number two on the Billboard 200, was certified gold by the RIAA a little less than two months after its release date,[123] and, as of May 8, 2009, sold 674,000 copies.[116]

A darker, more aggressive style of emo was also becoming popular. New Jersey–based Thursday signed a multimillion-dollar, multi-album contract with Island Def Jam after their 2001 album, Full Collapse, reached umber 178 on the Billboard 200.[124] Their music was more political and lacked pop hooks and anthems, influenced instead by the Smiths, Joy Division, and The Cure However, the band's accessibility, basement-show roots and touring with Saves the Day made them part of the emo movement.[125] Thursday's 2003 album, War All the Time, reached number seven on the Billboard 200.[126] Hawthorne Heights, Story of the Year, Underoath, and Alexisonfire, four bands frequently featured on MTV, have popularized screamo.[127] Other screamo bands include Silverstein,[128] Senses Fail[129][130] and Vendetta Red.[127] Underoath's albums They're Only Chasing Safety (2004)[131] and Define the Great Line (2006)[132] both were certified gold by the RIAA. The Used's self-titled album (2002) was certified gold by the RIAA on July 21, 2003.[133] The Used's self-titled album, as of August 22, 2009, has sold 841,000 copies.[134] The Used's album In Love and Death (2004) was certified gold by the RIAA on March 21, 2005.[135] In Love and Death, as of January 2, 2007, sold 689,000 copies in the United States, according to Nielsen SoundScan.[136] Four Alexisonfire albums were certified gold or platinum in Canada.[137][138][139][140]

Emo pop, a pop punk-oriented subgenre of emo with pop-influenced hooks, became the main emo style during the mid-late 2000s, with many of these bands being signed by Fueled by Ramen Records and some adopting a goth-inspired look.[98] My Chemical Romance broke into the mainstream with their 2004 album Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge. My Chemical Romance is known for their goth-influenced emo appearance and creation of concept albums and rock operas.[141][142] Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge was certified platinum by the RIAA in 2005.[143] The band's success continued with its third album, The Black Parade, which sold 240,000 copies in its first week of release[144] and was certified platinum by the RIAA in less than a year.[145] Fall Out Boy's album, From Under the Cork Tree, sold 2,700,000 copies in the United States.[146] The band's album, Infinity on High, topped the Billboard 200, sold 260,000 copies in its first week of release[147] and sold 1,400,000 copies in the United States.[146] Multiple Fall Out Boy songs reached the top ten of the Billboard Hot 100.[148] Panic! at the Disco's album, A Fever You Can't Sweat Out, was certified double platinum by the RIAA[149] and its single, "I Write Sins Not Tragedies", reached number seven on the Billboard Hot 100.[150] Panic! at the Disco are known for combining emo with electronics[151] and their album A Fever You Can't Sweat Out is an emo album[152] with elements of dance-punk[153] and baroque pop.[154] The Red Jumpsuit Apparatus' "Face Down" peaked at number 24 on the Billboard Hot 100[155] and its album, Don't You Fake It, sold 852,000 copies in the United States.[156] AFI's albums Sing the Sorrow and Decemberunderground both were certified platinum by the RIAA,[157][158] with Decemberunderground peaking at number 1 on the Billboard 200.[159] Paramore's 2007 album Riot! was certified double platinum by the RIAA[160] and several Paramore songs appeared on the Billboard Hot 100 in the late 2000s, including "Misery Business", "Decode", "Crushcrushcrush", "That's What You Get", and "Ignorance".[161] Emo band Boys Like Girls achieved mainstream success in the late 2000s with their songs experiencing Billboard Hot 100 success.[162]

2010s–present: Decline and revival

During the mid-2010s, emo's popularity began to wane. Some bands broke up or moved away from their emo roots;[163] According to an article from Vice Media, emo kids now grew up to be K-pop fans.[164] My Chemical Romance's album, Danger Days: The True Lives of the Fabulous Killjoys, had its traditional pop punk style.[165] Paramore and Fall Out Boy both abandoned the emo genre with their 2013 albums, Paramore and Save Rock and Roll, respectively.[166][167][168] Paramore moved to a new wave-influenced style.[169] Panic! at the Disco moved away from their emo pop roots to a synth-pop style on Too Weird to Live, Too Rare to Die!.[170] Many bands (including My Chemical Romance,[171] Alexisonfire,[172] and Thursday)[173] broke up, raising concerns about the genre's viability.[174]

Meanwhile, by the 2010s, a mainly underground emo revival emerged,[175][176][177] drawing on the sound and aesthetic of 1990s emo. Artists associated with this movement include Modern Baseball,[178] The World Is a Beautiful Place & I Am No Longer Afraid to Die,[175][177][179] A Great Big Pile of Leaves,[175] Pianos Become the Teeth,[177] Empire! Empire! (I Was a Lonely Estate),[175] Touché Amoré,[175][179] Into It. Over It.,[175][179] and the Hotelier.[180] While many 2010s emo bands draw on the sound and aesthetic of 1990s emo, hardcore punk elements are consistently used by 2010s emo bands such as Title Fight[181] and Small Brown Bike.[182]

By 2020, emo's impact on mainstream music of the 2010s, and a revival of the genre itself, was noted in some media outlets.[183][184] The BBC observed in 2018 "beyond guitar-based bands, the influence of emo can be seen in much of modern music, both in style and lyrical content, from genre-blurring artists like Post Malone, Princess Nokia and the late Lil Peep to emotive songwriters like James Blake and even Adele" and "addressing mental health issues has become increasingly more common in pop".[14]

Subgenres and fusion genres

Screamo

The term "screamo" was initially applied to an aggressive offshoot of emo which developed in San Diego in 1991 and used short songs grafting "spastic intensity to willfully experimental dissonance and dynamics."[185] Screamo is a dissonant form of emo influenced by hardcore punk,[127] with typical rock instrumentation and noted for short songs, chaotic execution and screaming vocals.

The genre is "generally based in the aggressive side of the overarching punk-revival scene."[127] It began at the Ché Café[187] with groups such as Heroin, Antioch Arrow,[188] Angel Hair, Mohinder, Swing Kids, and Portraits of Past.[189] They were influenced by Washington, D.C. post-hardcore (particularly Fugazi and Nation of Ulysses),[185] straight edge, the Chicago group Articles of Faith, the hardcore-punk band Die Kreuzen[190] and the post-punk and gothic rock bands like Bauhaus.[185] I Hate Myself is a band described as "a cornerstone of the 'screamo' genre" by author Matt Walker:[191] "Musically, I Hate Myself relied on being very slow and deliberate, with sharp contrasts between quiet, almost meditative segments that rip into loud and heavy portions driven by Jim Marburger's tidal wave scream."[192] Other early screamo bands include Pg. 99, Saetia, and Orchid.[193]

The Used, Thursday, Thrice and Hawthorne Heights, who all formed in the United States during the late 1990s and early 2000s and remained active throughout the 2000s, helped popularize screamo.[127] Post-hardcore bands such as Refused and At the Drive-In paved the way for these bands.[127] Screamo bands from the Canadian emo scene such as Silverstein[194] and Alexisonfire[195] also emerged at this time. By the mid-2000s, the saturation of the screamo scene caused many bands to expand beyond the genre and incorporate more-experimental elements. Non-screamo bands used the genre's characteristic guttural vocal style.[127] Some screamo bands during this time period were inspired by genres like pop punk and heavy metal.[127]

Jeff Mitchell of the Iowa State Daily wrote, "There is no set definition of what screamo sounds like but screaming over once deafeningly loud rocking noise and suddenly quiet, melodic guitar lines is a theme commonly affiliated with the genre."[196]

Sass

Sass (also known as sassy screamo, sasscore, white belt hardcore,[197] white belt, sassgrind or dancey screamo)[198] is a style that emerged from the late-1990s and early-2000s screamo scene.[199] The genre incorporates elements of post-punk, new wave, disco, electronic, dance-punk,[199] grindcore, noise rock, metalcore, mathcore and beatdown hardcore. The genre is characterized by often incorporating overtly flamboyant mannerisms, erotic lyrical content, synthesizers, dance beats and a lisping vocal style.[200] Sass bands include the Blood Brothers, An Albatross, The Number Twelve Looks Like You, the Plot to Blow Up the Eiffel Tower, Daughters's early music, Orchid's later music[201][202] and SeeYouSpaceCowboy.[203]

Emo pop

Emo pop (or emo pop punk) is a subgenre of emo known for its pop music influences, more concise songs and hook-filled choruses.[98] AllMusic describes emo pop as blending "youthful angst" with "slick production" and mainstream appeal, using "high-pitched melodies, rhythmic guitars, and lyrics concerning adolescence, relationships, and heartbreak."[98] The Guardian described emo pop as a cross between "saccharine boy-band pop" and emo.[204]

Emo pop developed during the 1990s. Bands like Jawbreaker and Samiam are known for formulating the emo pop punk style.[205] According to Nicole Keiper of CMJ New Music Monthly, Sense Field's Building (1996) pushed the band "into the emo-pop camp with the likes of the Get Up Kids and Jejune".[206] As emo became commercially successful in the early 2000s, emo pop became popular with Jimmy Eat World's 2001 album Bleed American and the success of its single "The Middle".[98] Jimmy Eat World,[98] the Get Up Kids[207] and the Promise Ring[208] also are early emo pop bands. The emo pop style of Jimmy Eat World's album, Clarity[209] influenced later emo.[210] The emo band Braid's 1998 album Frame & Canvas has been described as emo pop by Blake Butler of AllMusic, who gave the Braid album four out of five stars and wrote that Frame & Canvas "proves to be one of Braid's best efforts".[211] Emo pop became successful during the late 1990s, with its popularity increasing in the early 2000s. The Get Up Kids sold over 15,000 copies of their debut album, Four Minute Mile (1997), before signing with Vagrant Records. The label promoted them, sending them on tours to open for Green Day and Weezer.[88] Their 1999 album, Something to Write Home About, reached number 31 on Billboard's Top Heatseekers chart.[89] As of May 2, 2002, Something to Write Home About sold 134,000 copies in the United States, according to Nielsen SoundScan.

As emo pop coalesced, the Fueled by Ramen label became a center of the movement and signed Fall Out Boy, Panic! at the Disco, and Paramore (all of whom had been successful).[98] Two regional scenes developed. The Florida scene was created by Fueled by Ramen; midwest emo-pop was promoted by Pete Wentz, whose Fall Out Boy rose to the forefront of the style during the mid-2000s.[98][212][213] Cash Cash released Take It to the Floor (2008); according to AllMusic, it could be "the definitive statement of airheaded, glittery, and content-free emo-pop[214] ... the transformation of emo from the expression of intensely felt, ripped-from-the-throat feelings played by bands directly influenced by post-punk and hardcore to mall-friendly Day-Glo pop played by kids who look about as authentic as the "punks" on an old episode of Quincy did back in the '70s was made pretty much complete".[214] You Me at Six released their 2008 debut album, Take Off Your Colours, described by AllMusic's Jon O'Brien as "follow[ing] the 'emo-pop for dummies' handbook word-for-word."[215] The album was certified gold in the UK.[216]

.jpg.webp)

Emo rap

Emo rap is a genre that combines emo music with hip hop music.[218] The genre began in the mid–late 2010s.[218] Although emo rap typically uses regular instruments and sampling is often kept to a bare minimum, some artists sample 2000s pop punk and emo songs, a fusion first popularized by MC Lars in 2004.[219][220] A lot of the sampling is due to the artists who inspired the genre, such as Underoath and Brand New,[221] and is usually accompanied by original instruments. Prominent artists of emo hip hop include Lil Peep,[222] XXXTentacion,[218] and Nothing,Nowhere.[223][224]

In the mid-to-late 2010s, emo rap broke into the mainstream. Deceased rapper XXXTentacion's song "Sad!" peaked at number 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 on June 30, 2018. XXXTentacion also had other mainstream songs. His song "Moonlight" peaked at number 13 on the Billboard Hot 100 on July 7, 2018, his song "Changes" peaked at number 18 on the Billboard Hot 100 on June 30, 2018, and his song "Jocelyn Flores" peaked at number 19 on June 30, 2018.[225] Emo rap musician Lil Uzi Vert's song "XO Tour Llif3" peaked at number 7 on the Billboard Hot 100[226] and the song was certified 6× platinum by the RIAA.[227] Although emo rap experienced much mainstream popularity during the mid-to-late 2010s, emo rap musicians Lil Peep and XXXTentacion both died in November 2017 and June 2018, respectively. In November 2017, Lil Peep died of a Fentanyl and Xanax overdose.[228] In June 2018, XXXTentacion was shot and killed in Florida.[229]

Fashion and subculture

Origins (mid-late 1990s and early 2000s)

Emo as a subculture of people began in the mid-late 1990s. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, emo fashion was clean-cut and tended towards geek chic,[230] with clothing items like thick-rimmed glasses resembling 1950s musician Buddy Holly, button-down shirts, t-shirts, sweater vests, tight jeans, converse shoes, and cardigans being common.[9] In January 2002, the Honolulu Advertiser described emo people as "intentionally unshowy": "these guys often ride bicycles, keep diaries, write poetry and hang out at coffee shops. They prefer art films to Hollywood blockbusters and frequent independent music stores. They are usually shy and introspective."[230] Some emo bands at the turn of the 21st century, such as The Promise Ring, adopted a geek chic look.[9]

Change to a different style (early-mid 2000s)

Althoguh originally more geek chic-influenced, emo fashion began to change to its more famous, goth-influenced look that appeared in the 2000s. A lot of the change came from the hardcore punk, screamo and metalcore bands in the mid-late 1990s and early 2000s. The first origins date back to the mid-1990s San Diego screamo scene. The scene's bands, such as Heroin, Antioch Arrow and Swing Kids, and participants in this scene were often called "spock rock", in reference to their black-dyed hair with straight fringes.[197] As the vocalist of Swing Kids, Justin Pearson had choppy spikes protruding from the back of his head alongside straight fringes, which was a prototype for the emo haircut. After the 1998 release of the music video for "New Noise" by Swedish hardcore punk band Refused, straight, black hair with long, swooped bangs spread as a common fashion in hardcore punk. Refused adopted this haircut alongside black clothing and nail polish at a time when emo fashion was more geek chic-oriented.[197] Metalcore band Eighteen Visions was the band that expanded the prototype of later emo fashion. As many hardcore bands in the 1990s had a hypermasculine image characterized by shaved heads, baseball caps and tattoos, Eighteen Visions wanted to rebel against this image. Inspired by the look of bands like Orgy and Unbroken, Eighteen Visions dressed in effeminate fashion, including skinny jeans, straightened hair, swooped bangs, black clothes and eyeliner. Emphasizing their fashion of their music, they were labeled "fashioncore".[197][231] Fashioncore became a popular trend in hardcore and metalcore in the early 2000s, and other bands labeled as fashioncore included Avenged Sevenfold, Bleeding Through and Atreyu.[232][233][234] Influenced by the members of Eighteen Visions, emos in the early 2000s became increasingly experimental with their hair, making use of layers, asymmetrical fringes and cutting hair using razorblades. Haircuts such as the Bob and the A-Line cut were also popular.[197] Moreover, early-mid 2000s emo and pop punk bands like My Chemical Romance, AFI, and Good Charlotte wore black clothes and eyeliner.[235][236][237] These bands were often inspired by other bands that adopted a goth look, such as the Misfits and The Cure.[238][236][239]

Mainstream prevalence (mid-late 2000s)

Emo fashion in the mid-to-late 2000s included skinny jeans, tight T-shirts (usually short-sleeved, and often with the names of emo bands), studded belts, Converse sneakers, Vans and black wristbands.[240][241] Thick, horn-rimmed glasses remained in style to an extent,[240] and eye liner and black fingernails became common during the mid-2000s.[242][243] The best-known facet of emo fashion is its hairstyle: flat, straight, usually jet-black hair with long bangs covering much of the face,[241] which has been called a fad.[241] Emo fashion has been confused with goth[244] and scene fashion.[245]

As emo became a subculture, people who dressed in emo fashion and associated themselves with its music were known as "emo kids" or "emos".[241] My Chemical Romance,[241][243] Hawthorne Heights,[241] AFI,[241] Dashboard Confessional,[246] Taking Back Sunday,[247] Good Charlotte,[248] Brand New, From First to Last,[249] Bullet for My Valentine,[250] Story of the Year,[251] Funeral for a Friend,[252] Silverstein,[253] Simple Plan,[254] Aiden,[242] Fall Out Boy,[241][255] The Used,[242] Finch,[242] Panic! at the Disco,[254] Paramore,[254] The Red Jumpsuit Apparatus[256] and The All-American Rejects[257] all are bands that emos are known for listening to.

Controversy and backlash

Stereotypes

Emo has been associated with a stereotype of emotion, sensitivity, shyness, introversion or angst.[12][258][259] More controversially, stereotypes surrounding the genre included depression, self-harm and suicide,[241][260] in part stoked by depictions of emo fans as a "cult" by British tabloid Daily Mail.[261] Emos and goths were often distinguished by the stereotype that "emos hate themselves, while goths hate everyone."[262] In 2020, The Independent wrote on such stereotypes, that "emo was singled out for the destructive behaviour of teenagers who’d found a home in a subculture that offered them community and a vehicle for self-expression."[183]

Suicide and self harm

In 2008, emo music was blamed for the suicide by hanging of British teenager Hannah Bond by the coroner at her inquest and her mother, Heather Bond, who suggested that the music and fandom glamorised suicide. They suggested Hannah's apparent obsession with My Chemical Romance was linked to her death. It was said at the inquest that she was part of an Internet "emo cult", and an image of an emo girl with bloody wrists was on her Bebo page.[263] Hannah reportedly told her parents that her self-harm was an "emo initiation ceremony".[263] Heather Bond criticised emo culture: "There are 'emo' websites that show pink teddies hanging themselves."[263] The coroner's statements were featured in a series of articles in the Daily Mail.[261] After they were reported in NME, fans of emo music contacted the magazine to deny that it promoted self-harm and suicide.[264] My Chemical Romance reacted online: "We have recently learned of the suicide and tragic loss of Hannah Bond. We'd like to send our condolences to her family during this time of mourning. Our hearts and thoughts are with them".[265] The band also posted that they "are and always have been vocally anti-violence and anti-suicide".[265]

The Guardian later described the purported link and subsequent backlash against emo in the 2000s as a "moral panic",[266] while Kerrang! compared it to historic controversies involving Judas Priest and Ozzy Osbourne, unduly demonising the subculture, and poorly examining mental health issues of young people.[261]

Backlash

Emo received a lot of backlash during the 2000s. Warped Tour founder Kevin Lyman said that there was a "real backlash" by bands on the tour against emo groups, but he dismissed the hostility as "juvenile".[267] The backlash intensified, with anti-emo groups attacking teenagers in Mexico City, Querétaro, and Tijuana in 2008.[268][269] Legislation was proposed in Russia's Duma regulating emo websites and banning emo attire in schools and government buildings, with the subculture perceived as a "dangerous teen trend" promoting anti-social behaviour, depression, social withdrawal and suicide.[270][271] The BBC reported that in March 2012, Shia militias in Iraq shot or beat to death as many as 58 young Iraqi emos.[272] Metalheads and punks often were known for hating emos and criticizing the emo subculture.[273]

Terminology

The term "emo" has been the subject of controversy amongst artists, critics, and fans alike. Some find the label to be loosely defined[274] with the term at times being used to describe any music that expresses emotion.[184] The mainstream success of emo and its related subculture caused the term to be conflated with other genres.[275]

Many bands labeled as emo rejected the emo label. My Chemical Romance singer Gerard Way said in 2007 that emo is "a pile of shit":

"I think there are bands that we get lumped in with that are considered emo and, by default, that starts to make us emo. All I can say is that anyone actually listening to the records, putting the records next to each other and listening to them, [would know there are] actually no similarities."[276]

Brendon Urie of Panic! at the Disco said : "It's ignorant! The stereotype is guys that are weak and have failing relationships write about how sad they are. If you listen to our songs, not one of them has that tone."[277] Adam Lazzara of Taking Back Sunday said he always considered his band rock and roll instead of emo.[278] Guitarist of the Get Up Kids, Jim Suptic, noted the differences between the 2000s mainstream acts when compared to the emo bands of the 1990s, saying, “The punk scene we came out of and the punk scene now are completely different. It's like glam rock now. We played the Bamboozle fests this year and we felt really out of place... If this is the world we helped create, then I apologise.”[279] Vocalist of AFI, Davey Havok, described emo as “such a strange and meaningless word.”[280] Early emo musicians also have rejected the label. Guy Picciotto, the vocalist of Rites of Spring, said he considers the emo label "retarded" and always considered Rites of Spring a punk rock band: "The reason I think it's so stupid is that - what, like the Bad Brains weren't emotional? What - they were robots or something? It just doesn't make any sense to me."[281] Sunny Day Real Estate's members said they consider themselves simply a rock band, and said that back in the early days, the word "emocore" was an insult: "While I don't disrespect anyone for using the term emo-core, or rock, or anything, but back in the day, emo-core was just about the worst dis that you could throw on a band."[282]

The term “mall emo” has been used to separate mainstream bands like Paramore, Hawthorne Heights, My Chemical Romance, Panic! at the Disco, and Fall Out Boy from the less commercially viable bands that proceeded and succeeded them.[283][284][285] The term "mall emo" dates back to around 2002, when many emo fans did not like the change emo was going through at the time when the genre became mainstream.[104]

See also

- List of emo artists

- Scene

References

Citations

- "Emo". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Bryant 2014, p. 134.

- Cooper, Ryan. "Post-Hardcore – A Definition". About.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

all emo is post-hardcore, but not all post-hardcore is emo.

- Hansen 2009.

- Shuker 2017.

- "Emo Music Guide: A Look at the Bands and Sounds of the Genre - 2021 - MasterClass". Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- Green, Stuart (January 1, 2006). "The Get Up Kids...It's A Whole New Emo". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on July 21, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- Crane, Matt (April 17, 2014). "The 5 great eras of pop-punk, from the '70s to today". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on May 21, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- Kuipers, Dean (July 7, 2002). "Oh the Angst. Oh the Sales". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2017. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Diehl 2013, p. 82.

- Cooper, Ryan. "The Subgenres of Punk Rock". ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- La Gorce, Tammy (August 14, 2007). "Finding Emo". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 3, 2015. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- "Emo". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on March 23, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- Britton, Luke Morgan (May 30, 2018). "Emo never dies: How the genre influenced an entire new generation". BBC Online. Archived from the original on August 13, 2018. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- "Post-Hardcore". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 12.

- "Rites of Spring | Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 9–11.

- Blush 2001, p. 157.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 12–13.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 13.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 14.

- Azerrad 2001, p. 380.

- Khanna, Vish (February 2007). "Timeline: Ian MacKaye – Out of Step". Exclaim.ca. Archived from the original on January 10, 2013. Retrieved April 19, 2009.

- DePasquale, Ron. "Embrace: Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- Popkin, Helen (March 26, 2006). "What Exactly Is 'Emo,' Anyway?". Today.com. Today.com. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 14–15.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 15.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 15–17.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 15–16.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 18.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 19.

- Etc (CD booklet). Jawbreaker. San Francisco: Blackball Records. 2002. BB-003-CD.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - Greenwald 2003, p. 21.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 20.

- Monger, James Christopher. "Jawbreaker | Biography & History". AllMusic. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 21–22.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 24–25.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 25–26.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 28.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 29–31.

- Smith, Rich (June 1, 2016). "A Grown-Up Emo Kid Braces for the Coming Wave of Emo Nostalgia". The Stranger. Archived from the original on July 21, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- Ayers, Michael D. (August 21, 2009). "Weezer Filled With 'Raditude' This Fall". Billboard. Archived from the original on September 20, 2014. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Mackay, Emily (November 2, 2009). "Album review: Weezer – 'Raditude'". NME. Archived from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Book Your Own Fuckin' Life #3: Do-It-Yourself Resource Guide. San Francisco, CA: Maximum Rocknroll, 1994; pg. 3.

- Leahey, Andrew. "Jimmy Eat World | Biography & History". AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 12, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 33.

- "American album certifications – Green Day – Dookie". Recording Industry Association of America.

- "American album certifications – Offspring – Smash". Recording Industry Association of America.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 34–35.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 34.

- Galil, Leor (August 5, 2013). "Midwestern emo catches its second wind". The Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 38–39.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 121–122.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 122.

- Rashbaum, Alyssa (March 24, 2006). "A Lifetime of Rock". Spin. Archived from the original on August 11, 2018. Retrieved March 28, 2009.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 80.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 152.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 51.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 35–36.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 36.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 37.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 40.

- Edwards, Gavin (December 9, 2001). "Review: Pinkerton". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 5, 2006. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- Erlewine, Stephen. "Allmusic: Pinkerton: Overview". AllMusic. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 50.

- Luerssen 2004, p. 206.

- Luerrsen 2004, p. 137.

- Luerrsen 2004, p. 348.

- Montgomery, James (October 25, 2004). "The Argument: Weezer Are the Most Important Band of the Last 10 Years". MTV. Archived from the original on February 3, 2006. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- "American album certifications – Weezer – Pinkerton". Recording Industry Association of America.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 41.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 46–48.

- Greenwald, pp. 42–44.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 42.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 45–46.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 99–101.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 44.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 48.

- "The Emo Diaries". Deep Elm Records. Archived from the original on February 6, 2009. Retrieved March 27, 2009.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 101.

- Vanderhoff, Mark. "Clarity – Jimmy Eat World". AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 102–205.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 104–108.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 126–132.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 127.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 127–129.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 77–78.

- "Heatseekers: Something to Write Home About". Billboard charts. Archived from the original on June 10, 2009. Retrieved March 25, 2009.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 79.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 81.

- "Artist Chart History – Saves the Day". Billboard charts. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

- Sheffield, Rob (March 28, 2002). "Punk From the Heart". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 5, 2004. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

- Bein, Kat (July 12, 2016). "Blink-182 Songs: List of the 7 Best Remixes". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- "American album certifications – Blink-182 – Enema of the State". Recording Industry Association of America.

- "blink-182 Chart History (Alternative Songs)". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 81–88.

- "Emo-Pop". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 5, 2012. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 52.

- "American album certifications – Weezer – Weezer (2001)". Recording Industry Association of America.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 68.

- "Jimmy Eat World singles chart history". Billboard charts. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- "Dashboard Confessional albums chart history". Billboard charts. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- "Emo-esque, huh?". News24. July 26, 2002. Archived from the original on August 12, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 94.

- Connick, Tom (April 30, 2018). "The beginner's guide to the evolution of emo". NME. Archived from the original on August 13, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- Leahey, Andrew. "Dashboard Confessional | Biography & History". AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 21, 2017. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 196.

- "Gold & Platinum (Dashboard Confessional)". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on July 30, 2020. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- DeRogatis, Jim (October 3, 2003). "True Confessional?". Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- Caulfield, Keith (October 19, 2007). "Ask Billboard". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 12, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- Sanneh, Kelefa (August 10, 2003). "Music; Sweet, Sentimental and Punk". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 13, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 67.

- Wilson, MacKenzie. "Saves the Day Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

- "American album certifications – Taking Back Sunday – Tell All Your Friends". Recording Industry Association of America.

- Wood, Mikael (May 8, 2009). "Exclusive Video: Taking Back Sunday's Latest Epic". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 9, 2017. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 88.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 68–69.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 140–141.

- Greenwald 2003, p. 142.

- "American album certifications – Taking Back Sunday – Where You Want To Be". Recording Industry Association of America.

- "Taking Back Sunday Plans Spring U.S. Tour". Billboard. February 17, 2006. Archived from the original on August 12, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- "American album certifications – Taking Back Sunday – Louder Now". Recording Industry Association of America.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 149–150.

- Greenwald 2003, pp. 153–155.

- "Artist Chart History – Thursday – Albums" Billboard.

- Explore style: Screamo Archived July 28, 2018, at the Wayback Machine at AllMusic Music Guide

- Lake, Dave (December 2, 2015). "Senses Fail Singer Buddy Nielsen Blames Apathy for Breeding "Garbage Like Donald Trump"". New Times Broward-Palm Beach. Archived from the original on July 22, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- Alex Henderson. "Let It Enfold You". AllMusic. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- Andrew Leahey. "Life Is Not a Waiting Room". AllMusic. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- "American album certifications – Underoath – They're Only Chasing Safety". Recording Industry Association of America.

- "American album certifications – Underoath – Define the Great Line". Recording Industry Association of America.

- "American album certifications – The Used – The Used". Recording Industry Association of America.

- Leebove, Laura (August 22, 2009). "Guitar Heroes". Billboard. Vol. 121, no. 33. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. p. 31. ISSN 0006-2510.

- "American album certifications – The Used – In Love and Death". Recording Industry Association of America.

- Cohen, Jonathan (January 2, 2007). "Live CD/DVD To Precede New Used Album". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 9, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- "Canadian album certifications – Alexisonfire – Alexisonfire". Music Canada.

- "Canadian album certifications – Alexisonfire – Watch Out!". Music Canada.

- "Canadian album certifications – Alexisonfire – Crisis". Music Canada.

- "Canadian album certifications – Alexisonfire – Old Crows / Young Cardinals". Music Canada.

- Spanos, Brittany (July 21, 2016). "My Chemical Romance Plots 'Black Parade' Reissue for 10th Anniversary". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 13, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- Leahey, Andrew. "My Chemical Romance | Biography & History". AllMusic. Archived from the original on July 18, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- "American album certifications – My Chemical Romance – Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge". Recording Industry Association of America.

- Harris, Chris (November 1, 2006). "Hannah Montana Rains On My Chemical Romance's Parade". MTV. Archived from the original on February 20, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- "American album certifications – My Chemical Romance – The Black Parade". Recording Industry Association of America.

- "Fall Out Boy to 'Save Rock and Roll' in May". Billboard. February 4, 2013. Archived from the original on September 7, 2014. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Hasty, Katie (February 14, 2007). "Fall Out Boy Hits 'High' Note With No. 1 Debut". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 5, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- "Fall Out Boy – Chart History". Billboard.

- "American album certifications – Panic! at the Disco – A Fever You Can't Sweat Out". Recording Industry Association of America.

- "Panic! at the Disco – Chart History". Billboard.

- Galil, Leor (July 14, 2009). "Scrunk happens". The Phoenix. Archived from the original on August 19, 2009. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- Bayer, Jonah; Burgess, Aaron; Exposito, Suzy; Galil, Leor; Montgomery, James; Spanos, Brittany (March 1, 2016). "40 Greatest Emo Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 30, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- Zemler, Emily (October 3, 2005). "Panic! at the Disco". Spin. Archived from the original on October 2, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- Story, Hannah (January 11, 2016). "Panic! At The Disco – Death Of A Bachelor". The Music. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- "The Red Jumpsuit Apparatus | Awards". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 21, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Cohen, Jonathan (August 18, 2008). "Red Jumpsuit Apparatus Recording New Album". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- "American album certifications – AFI – Sing the Sorrow". Recording Industry Association of America.

- "American album certifications – AFI – Decemberunderground". Recording Industry Association of America.

- "AFI Burns Brightly With No. 1 Debut". Billboard. June 14, 2006. Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- "American album certifications – Paramore – Riot!". Recording Industry Association of America.

- "Paramore – Chart history". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- "Boys Like Girls Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- "My Chemical Romance Shed Their Emo Roots". Dallas Observer. May 19, 2011.

- "Why So Many Former Emos Are Now K-Pop Fans". Vice. July 29, 2019. Archived from the original on August 24, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- "My Chemical Romance: Danger Days: The True Lives of the Fabulous Killjoys – review". The Guardian. November 18, 2010. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- Rolli, Bryan (January 22, 2018). "Fall Out Boy's 'MANIA' Proves The Value Of Authenticity". Forbes. Archived from the original on August 27, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- Anderson, Kyle (April 10, 2013). "Paramore". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- Ben Rayner (April 8, 2013). "Paramore's glossy a bid for superstardom: album review | Toronto Star". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- Collar, Matt. "After Laughter – Paramore". AllMusic. Archived from the original on July 22, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- "Too Weird to Live, Too Rare to Die! – Panic! at the Disco". AllMusic. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Kerrang! MCR Split: Gerard Way Confirms Break Up Archived March 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Kerrang.com. Retrieved on 2013-12-12.

- Murphy, Sarah (August 9, 2012). "Alexisonfire Reveal 10 Year Anniversary Farewell Tour". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on August 11, 2012. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- Rosenbaum, Jason (December 2, 2011). "A Hole in the World: Thursday Calls it Quits". Riverfront Times. Archived from the original on July 21, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- "What Happened to Emo?". MTV Hive. April 24, 2013. Archived from the original on September 5, 2013. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- DeVille, Chris (October 2013). "12 Bands To Know From The Emo Revival". Stereogum. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

- Ducker, Eric (November 18, 2013). "A Rational Conversation: Is Emo Back?". NPR. Archived from the original on November 27, 2013. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

- Cohen, Ian. "Your New Favorite Emo Bands: The Best of Topshelf Records' 2013 Sampler". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

- Sharp, Tyler (January 7, 2015). "Modern Baseball keep the emo revival alive with "Alpha Kappa Fall Of Troy The Movie Part Deax"". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- Gormelly, Ian. "Handicapping the Emo Revival: Who's Most Likely to Pierce the Stigma?". Chart Attack. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

- Chatterjee, Kika (July 29, 2017). "18 bands leading the emo revival". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- Heaney, Gregory. "Title Fight". AllMusic. Archived from the original on September 7, 2013. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- Zac Johnson. "The River Bed – Small Brown Bike – Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards – AllMusic". AllMusic. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- "How the emo genre bounced back from the brink". The Independent. March 20, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- "In its fourth wave, emo is revived and thriving". August 15, 2018. Archived from the original on October 31, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- Heller, Jason (June 20, 2002). "Feast of Reason". Westword. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 15, 2008.

- Brownlee, Bill (August 31, 2016). "Screamo band the Used salvages an affecting debut album on first of two nights at the Midland". The Kansas City Star. Archived from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "A Day with the Locust", L.A. Weekly, September 18, 2003 "Brassland | Home". Archived from the original on March 5, 2009. Retrieved September 14, 2011. Access date: June 19, 2008

- Local Cut, Q&A with Aaron Montaigne. "Q&A: Aaron Montaigne (Of Antioch Arrow, Magick Daggers, etc.)-- local Cut". Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved June 10, 2011. May 14, 2008. Access date: June 11, 2008.

- Ebullition Catalog, Portraits of Past discography. Archived July 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Access date: August 9, 2008.

- "Blood Runs Deep: 23 A hat". Alternative Press. July 7, 2008. p. 126.

- Walker 2016, pp. 102–103.

- Walker 2016, p. 102.

- Ozzi, Dan (August 1, 2018). "The Spirit of Screamo Is Alive and Well". Vice. Archived from the original on May 8, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- Adams, Gregory (January 23, 2008). "Silverstein sacrifices for screamo's sake". The Georgia Straight. Archived from the original on December 8, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- Usinger, Mike (February 10, 2010). "Punk classics helped reignite Alexisonfire". The Georgia Straight. Archived from the original on December 8, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- Mitchell, Jeff (July 26, 2001). "A Screamin' Scene". Iowa State Daily. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- Stewart, Ethan (May 25, 2021). "From Hardcore to Harajuku: the Origins of Scene Subculture". PopMatters. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- PREIRA, MATT. "Ten Best Screamo Bands From Florida". New Times Broward-Palm Beach. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- Warwick, Kevin (June 22, 2016). "All that sass: The albums that define the '00s dance-punk era". The A.V. Club. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ROA, RAY. "WTF is sasscore, and why is SeeYouSpaceCowboy bringing it to St. Petersburg's Lucky You Tattoo?". Creative Loafing. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- Stewart, Ethan (May 25, 2021). "From Hardcore to Harajuku: the Origins of Scene Subculture". PopMatters. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- "What is Sasscore? • DIY Conspiracy". April 9, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- Adams, Gregory (August 14, 2018). "SeeYouSpaceCowboy: Meet "Sasscore" Band Rallying Marginalized People to "Bite Back"". Revolver. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- Lester, Paul (December 8, 2008). "New band of the day – No 445: Metro Station". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 26, 2017. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

They peddle "emo-pop", a sort of cross between saccharine boy-band pop and whatever it is that bands like Panic! at the Disco and Fall Out Boy do – emo, let's be frank.

- Catucci, Nick (September 26, 2000). "Emotional Rescue". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on December 8, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- Kieper, Nicole (October 2001). "Sense Field: Tonight and Forever – Nettwerk America". CMJ New Music Monthly. CMJ Network. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- "The Get Up Kids Prep Vinyl Reissues of 'Eudora' and 'On a Wire'".

- "Promise Ring swears by bouncy, power pop". The Michigan Daily. April 12, 2001. Archived from the original on December 30, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- "Jimmy Eat World – Clarity – Review". Stylus Magazine. Archived from the original on May 3, 2010.

- Merwin, Charles (August 9, 2007). "Jimmy Eat World > Clarity > Capitol". Stylus. Archived from the original on May 3, 2010. Retrieved May 16, 2010.

- Butler, Brian. "Frame & Canvas – Braid". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- Loftus, Johnny. "Fall Out Boy". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 27, 2011. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- Futterman, Erica. "Fall Out Boy Biography". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- Sendra, Tim. "Take It to the Floor". AllMusic. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- O'Brien, Jon. "Take Off Your Colours – You Me at Six | Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- "Certified Awards". Archived from the original on June 25, 2014. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- "XXXTentacion's 2017 XXL Freshman Freestyle and Interview". XXL. June 30, 2017. Archived from the original on July 21, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- Zoladz, Lindsay (August 30, 2017). "XXXTentacion, Lil Peep, and the Future of Emo". The Ringer. Archived from the original on March 15, 2018. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- Vincent, Brittany (October 9, 2017). "Lil Aaron revives meme-tastic dancing goth clip with 'Hot Topic' video". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on October 17, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- "MC Lars Sends Up Emo On New Single, Which Stars Fake Band Hearts That Hate". MTV. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- Angus Harrison (April 21, 2017). "Lil Peep: the YouTube rapper who's taking back emo". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- Hockley-Smith, Sam (August 18, 2017). "The Unappealing World of Lil Peep, Explained". Vulture. Vulture.com. Archived from the original on September 25, 2017. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Caramanica, Jon (October 20, 2017). "nothing,nowhere. Blends Hip-Hop and Emo to Make Tomorrow's Pop". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 26, 2018. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- Reeves, Mosi (October 31, 2017). "Review: Nothing,Nowhere.'s Tormented Emo-Rap Shows Hip-Hop's Post-Modern Evolution". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- "XXXTentacion Chart History". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- "Lil Uzi Vert Chart History". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 30, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- "American single certifications – Lil Uzi Vert – XO Tour Llif3". Recording Industry Association of America.

- Britton, Luke Morgan (December 11, 2017). "Lil Peep's cause of death revealed". NME. Archived from the original on December 9, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- Snapes, Laura (July 20, 2018). "XXXTentacion: four men charged with rapper's murder". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 20, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- Rath, Paula (January 8, 2002). "Geek chic look is clean cut". The Honolulu Advertiser. Archived from the original on April 11, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- Wiederhorn, Jon; Turman, Katherine (July 17, 2013). "How Eighteen Visions Became The OC Metal Band Known For Inventing "Fashioncore"". OC Weekly. Archived from the original on June 4, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- Richman, Jesse (January 24, 2018). "What is Emo, Anyway? We Look at History to Define a Genre". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on June 8, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- Deneau, Max (December 1, 2005). "Bleeding Through Wolves Among Sheep". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on June 8, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- "Easy, Breezy, Brutal: Three Major Movements in Heavy Metal Makeup". Cjlo. February 10, 2014. Archived from the original on June 8, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- Leahey, Andrew. "My Chemical Romance". AllMusic. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- Krovatin, Chris (October 16, 2019). "Horror punk: 19 songs you need to know". Kerrang!. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- De Blase, Frank (May 18, 2005). "Good Charlotte is just a rock band". Rochester City Newspaper. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- Nichols, Natalie (June 5, 2003). "The people's punks". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- "Gerard Way tells about My Chemical Romance's influences". MTV. September 14, 2006. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- Adler & Adler 2011, p. 171.

- Poretta, JP (March 3, 2007). "Cheer up Emo Kid, It's a Brand New Day". The Fairfield Mirror. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007. Retrieved March 8, 2007.

- Shuster, Yelena (July 17, 2008). "Black Bangs, Piercings Raise Eyebrows in Duma". The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017.

- Thomas-Handsard, Artemis (December 6, 2016). "10 Emo Songs for People Who Don't Know Shit About "Emotional Hardcore"". L.A. Weekly. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- "How are goths and emos defined?". BBC News. April 4, 2013. Archived from the original on January 3, 2018. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- Caroline Marcus "Inside the clash of the teen subcultures" Archived July 5, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Sydney Morning Herald March 30, 2008

- Mehta, Raghav (January 24, 2017). "A reformed emo kid revisits Dashboard Confessional". City Pages. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- Gassman, Ian (September 15, 2016). "Taking Back Sunday a far cry from emo roots on "Tidal Wave"". The Denver Post. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- Sherman, Maria (December 17, 2015). "The Emo Revival: Why Mall Punk Nostalgia Isn't Fading Away". Fuse.tv. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- Sudakov, Dmitry (December 19, 2006). "Moscow teens develop their own emo-culture, worshipping depression and sadness". Pravda Report. Archived from the original on August 4, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- Jaffer, Dave (March 30, 2006). "Bullet For My Valentine – The Poison". Hour Community. Archived from the original on August 4, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- Gracie, Bianca (September 27, 2016). "Story of the Year Plans to Drop New Music Next Year". Fuse. Archived from the original on September 28, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- "Albums of the week". Metro. May 17, 2007. Archived from the original on August 4, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- James, Amber (July 5, 2016). "Fest Review: Amnesia Rockfest Day 1 in Montebello, Quebec". New Noise. Archived from the original on August 4, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2018.