Enter the Dragon

Enter the Dragon (Chinese: 龍爭虎鬥) is a 1973 martial arts film directed by Robert Clouse and written by Michael Allin. The film stars Bruce Lee, John Saxon and Jim Kelly. It was Lee's final completed film appearance before his death on 20 July 1973 at the age of 32. An American and Hong Kong co-production, it premiered in Los Angeles on 19 August 1973, one month after Lee's death. The film is estimated to have grossed over US$400 million worldwide (estimated to be the equivalent of over $2 billion adjusted for inflation as of 2022), against a budget of $850,000. Having earned more than 400 times its budget, it is one of the most profitable films of all time as well as the most successful martial arts film.

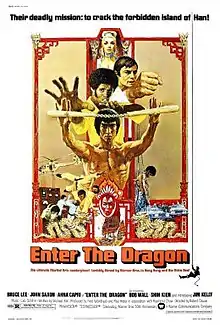

| Enter the Dragon | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Bob Peak | |

| Traditional | 龍爭虎鬥 |

| Simplified | 龙争虎斗 |

| Mandarin | Lóng Zhēng Hǔ Dòu |

| Cantonese | Lung4 Zang1 Fu2 Dau3 |

| Directed by | Robert Clouse |

| Written by | Michael Allin |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Gilbert Hubbs |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Lalo Schifrin |

Production company | Concord Production Inc. |

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 102 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $850,000 |

| Box office | $400 million |

Enter the Dragon is widely regarded as one of the greatest martial arts films of all time.[2] In 2004, it was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[3][4][5] Among the first films to combine martial arts action with spy film elements and the emerging blaxploitation genre, its success led to a series of similar productions combining the martial arts and blaxploitation genres.[6] Its themes generated scholarly debate about the changes taking place within post-colonial Asian societies following the end of World War II.[7] Enter the Dragon is also considered one of the most influential action films of all time, with its success contributing to mainstream worldwide interest in the martial arts as well as inspiring numerous fictional works, including action films, television shows, action games, comic books, manga and anime.

Plot

Lee, a highly proficient martial artist and instructor from Hong Kong, is approached by Braithwaite, a British intelligence agent investigating a suspected crime lord named Han. Lee is persuaded to attend a high-profile martial arts tournament on Han's private island to gather evidence that will prove Han's involvement in drug trafficking and prostitution. Shortly before his departure, Lee also learns that the man responsible for his sister's death, O'Hara, is working as Han's bodyguard on the island. Also fighting in the competition are Roper, an indebted gambling addict, and fellow Vietnam War veteran Williams. At the end of the first day, Han gives strict orders to the competitors not to leave their rooms. Lee makes contact with covert operative Mei Ling and sneaks into Han's underground compound, looking for evidence. He is discovered by several guards, but manages to escape.

The next morning, Han orders his giant enforcer Bolo to kill the guards in public for failing in their duties. After the execution, the competition resumes with Lee facing O'Hara. Lee beats O'Hara in humiliating fashion, then kills him after he attacks Lee with a pair of broken bottles. Han abruptly ends the day's competition after stating that O'Hara's treachery has disgraced them. Han confronts Williams, who had also left his room the previous night to exercise. Han believes Williams to have knowledge of the intruder and after a destructive brawl, beats Williams to death with his iron prosthetic hand. Han then reveals his drug operation to Roper, hoping that he will join his organisation. Han also implicitly threatens to imprison Roper, along with all the other martial artists who joined Han's tournaments in the past, if Roper will not join his operation. Despite being initially intrigued, Roper refuses after learning of Williams's fate.

Lee sneaks out again that night and manages to send a message to Braithwaite, but he is captured after a prolonged battle with the guards. The next morning, Han arranges for Roper to fight Lee, but Roper refuses. As a punishment, Roper has to fight Bolo instead, whom he manages to overpower and beat after a grueling battle. Enraged by the unexpected failure, Han commands his remaining men to kill Lee and Roper. Facing insurmountable odds, they are soon aided by the island's prisoners and the other invited martial artists, who had been freed by Mei Ling. Han escapes and is pursued by Lee, who finally corners him in his museum. After a brutal fight, Han runs away into a hidden mirror room. The mirrors initially give Han an advantage, but Lee smashes all the room's mirrors to reveal Han's location and eventually kills him. Lee returns outside to the main battle, which is now over. Bruised and bloodied, Lee and Roper exchange a weary thumbs-up as the military finally arrives to take control of the island.

Cast

- Bruce Lee as Lee, a martial artist who instructs pupils at the Shaolin Temple. He is given an assignment to infiltrate Han's island.

- John Saxon as Roper, a martial artist and gambling addict who is invited to Han's island.

- Jim Kelly as Williams, a martial artist who is invited to Han's island. He and Roper were fellow veterans that served in the Vietnam War. This was Kelly's breakout role.[8][9]

- Ahna Capri as Tania, Han's secretary who coordinates the ladies on Han's island.[10]

- Shih Kien as Han (voice dubbed by Keye Luke),[11] a crime lord and renegade Shaolin monk who organizes a martial arts tournament with hopes of recruiting talent to his underground drug operations. He has an artificial left hand that he can attach various weapons, including a claw and a set of blades.

- Bob Wall as O'Hara,[12] Han's bodyguard, noted for a facial scar over his left eye. He was responsible for the attack on Lee's family and sister. Wall previously appeared as a different character in Way of the Dragon and would later appear as a third character in Game of Death.[13]

- Angela Mao Ying as Su Lin, Lee's sister.

- Betty Chung as Mei Ling, an operative who is working undercover as one of Han's ladies.

- Geoffrey Weeks as Braithwaite, a British Intelligence agent who briefs Lee on the mission.

- Yang Sze as Bolo, Han's enforcer.

- Peter Archer as Parsons, an arrogant New Zealand martial artist who is invited to Han's island.

- Jackie Chan (uncredited) as a minor henchman.

Production

Due to the success of his earlier films, Warner Bros began helping Bruce Lee with the film in 1972. They brought in producers Fred Weintraub and Paul Heller.[14] The film was produced on a tight production budget of $850,000.[15] Fighting sequences were staged by Bruce Lee.[16]

Writing

The screenplay title was originally named Blood and Steel. The story features Asian, White and Black heroic protagonists because the producers wanted a film that would appeal to the widest possible international audiences.[17] The scene in which Lee states that his style is "Fighting Without Fighting" is based upon a famous anecdote involving the 16th century samurai Tsukahara Bokuden.[18][19]

Casting

Rod Taylor was first choice for playing the down-on-his-luck martial artist Roper. Director Robert Clouse had already worked with Taylor in the 1970 film Darker than Amber. However, Taylor was dropped after Bruce Lee deemed him to be too tall for the role.[20][21] John Saxon, who was a black belt in Judo and Shotokan Karate (he studied under grandmaster Hidetaka Nishiyama for three years),[22] became the preferred choice.[23] During contractual negotiations, Saxon's agent told the film's producers that if they wanted him they would have to change the plot so that the character of Williams is killed instead of Roper. They agreed and the script was changed.[24] In a six decade career, the character would become one of Saxon's best known roles.[25]

Rockne Tarkington was originally cast in the role of Williams. However, he unexpectedly dropped out days before the production was about to begin in Hong Kong. Producer Fred Weintraub knew that karate world champion Jim Kelly had a training dojo in Crenshaw, Los Angeles, so he hastily arranged a meeting. Weintraub was immediately impressed, and Kelly was cast in the film.[8] The success of Kelly's appearance launched his career as a star: after Enter the Dragon, he signed a three-film deal with Warner Bros[26] and went on to make several martial arts-themed blaxploitation films in the 1970s.[27]

Jackie Chan has uncredited roles as various guards during the fights with Lee. However, Yuen Wah was Lee's main stunt double for the film, responsible for the gymnastics stunts such as the cartwheels and jumping back flip in the opening fight.[28]

Sammo Hung also has an uncredited role in the opening fight scene against Lee at the start of the film.[29]

A rumor surrounding the making of Enter The Dragon claims that actor Bob Wall did not like Bruce Lee and that their fight scenes were not choreographed. However, Wall has denied this, stating he and Lee were good friends.[13]

Filming

The film was shot on location in Hong Kong. In keeping with local film-making practices, scenes were filmed without sound: dialogue and sound effects were added or dubbed in during post-production. Bruce Lee, after he had been goaded or challenged, fought several real fights with the film's extras and some set intruders during filming.[30] The scenes on Han's Island were filmed at a residence known as Palm Villa near the coastal town of Stanley.[31] The villa is now demolished and the area heavily redeveloped around Tai Tam Bay where the martial artists were filmed coming ashore.[32][33]

Soundtrack

Argentinian musician Lalo Schifrin composed the film's musical score. While Schifrin was widely known at the time for his jazz scores, he also incorporated funk and traditional film score elements into the film's soundtrack.[34] He composed the score by sampling sounds from China, Korea, and Japan. The soundtrack has sold over 500,000 copies, earning a gold record.[6]

Release

Marketing

Enter the Dragon was heavily advertised in the United States before its release. The budget for advertising was over US$1 million. It was unlike any promotional campaign that had been seen before, and was extremely comprehensive. To advertise the film, the studio offered free Karate classes, produced thousands of illustrated flip books, comic books, posters, photographs, and organised dozens of news releases, interviews, and public appearances for the stars. Esquire, The Wall Street Journal, Time, and Newsweek all wrote stories on the film.[35]

Box office

Enter the Dragon was one of the most successful films of 1973.[35] Upon release in Hong Kong, the film grossed HK$3,307,536,[36] which was huge business for the time, but less than Lee's previous 1972 films Fist of Fury and The Way of the Dragon.

In North America, the film was receiving offers of US$500,000 (equivalent to $3,100,000 in 2021) from American distributors by April 1973 for the distribution rights, several months before release.[37] Upon its limited release in August 1973 in four theaters in New York, the film entered the weekly box office charts at number 17 with a gross of $140,010 (equivalent to $850,000 in 2021) in 3 days.[38][39] Upon its expansion the following week, it topped the charts for two weeks.[40] Over the next four weeks, it remained in the top 10 while competing with other kung fu films, including Lady Kung Fu, The Shanghai Killers and Deadly China Doll which held the top spot for one week each.[41] In October, Enter the Dragon regained the top spot in its eighth week.[41] It sold 14.1 million tickets[42] and grossed $25,000,000 (equivalent to $150,000,000 in 2021) from its initial US release, making it the year's fourth highest-grossing film in the market.[43] It was repeatedly re-released throughout the 1970s, with each re-release entering the top five in the box office charts.[44] The film's US gross had increased to $100 million by 1982,[45][46] and more than $120 million (equivalent to $620 million adjusted for inflation) by 1998.[47]

In Europe, the film initially monopolized several London West End cinemas for five weeks, before becoming a sellout success across Britain and the rest of Europe.[48] In Spain, it was the seventh top-grossing film of 1973,[49] selling 2,462,489 tickets.[50] In France, it was one of the top five highest-grossing films of 1974 (above two other Lee films, Way of the Dragon at number 8 and Fist of Fury at number 12), with 4,444,582 ticket sales.[51] In Germany, it was one of the top 10 highest-grossing films of 1974, with 1.7 million ticket sales.[52] In Greece, the film earned $1,000,000 (equivalent to $6,100,000 in 2021) in its first year of release.[53]

In Japan, it was the second highest-grossing film of 1974 with distributor rental earnings of ¥1,642,000,000 (equivalent to ¥3,445,000,000 in 2019).[54] In South Korea, the film sold 229,681 tickets in the capital city of Seoul.[55] In India, the movie was released in 1975 and opened to full houses; in one Bombay theater, New Excelsior, it had a packed 32-week run.[56] The film was also a success in Iran, where there was a theater which played it daily up until the 1979 Iranian Revolution.[44]

Against a tight budget of $850,000,[15] the film grossed US$100,000,000 (equivalent to $610,000,000 in 2021) upon its initial 1973 worldwide release,[57][58][59] making it one of the world's highest-grossing films of all time up until then.[58] The film went on to have multiple re-releases around the world over the next several decades, significantly increasing its worldwide gross.[15] The film went on to gross over $220 million internationally by 1981, making it the highest-grossing martial arts film of all time.[60] It was reportedly still among the top 50 all-time highest-grossing films in 1990.[61] By 1998, it had grossed more than $300 million worldwide.[62] As of 2001, it has grossed an estimated total of over $400 million worldwide,[63] having earned more than 400 times its original budget.[15] The film's cost-to-profit ratio makes it one of the most commercially successful and profitable films of all time.[48][64] Adjusted for inflation, the film's worldwide gross is estimated to be the equivalent of over $2 billion as of 2022.[65][66]

Critical reception

Upon release, the film initially received mixed reviews from several critics,[41] including a favorable review from Variety magazine.[67] The film eventually went on to be well-received by most critics, and it is widely regarded as one of the best films of 1973.[68][69][70] Critics have referred to Enter the Dragon as "a low-rent James Bond thriller",[71][72] a "remake of Dr. No" with elements of Fu Manchu.[73] J.C. Maçek III of PopMatters wrote, "Of course the real showcase here is the obvious star here, Bruce Lee, whose performance as an actor and a fighter are the most enhanced by the perfect sound and video transfer. While Kelly was a famous martial artist and a surprisingly good actor and Saxon was a famous actor and a surprisingly good martial artist, Lee proves to be a master of both fields."[74]

Many acclaimed newspapers and magazines reviewed the film. Variety described it as "rich in the atmosphere", the music score as "a strong asset" and the photography as "interesting".[75] The New York Times gave the film a rave review: "The picture is expertly made and well-meshed; it moves like lightning and brims with color. It is also the most savagely murderous and numbing hand-hacker (not a gun in it) you will ever see anywhere."[76]

The film holds a 95% approval rating on the review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes based on 55 reviews, with an average rating of 7.80/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "Badass to the max, Enter the Dragon is the ultimate kung-fu movie and fitting (if untimely) Bruce Lee swan song."[77] On Metacritic it has a weighted average score of 83% based on reviews from 16 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[78] In 2004, the film was deemed "culturally significant" by the Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.[79]

Enter the Dragon was selected as the best martial arts film of all time, in a 2013 poll of The Guardian and The Observer critics.[2] The film also ranks No. 474 on Empire magazine's 2008 list of The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time.[80]

Home video

Enter the Dragon has remained one of the most popular martial arts films since its premiere and has been released numerous times worldwide on multiple home video formats. For almost three decades, many theatrical and home video versions were censored for violence, especially in the West. In the U.K. alone, at least four different versions have been released. Since 2001, the film has been released uncut in the U.K. and most other territories.[81][82][83] Most DVDs and Blu-rays come with a wide range of extra features in the form of documentaries, interviews, etc. In 2013, a second, remastered HD transfer appeared on Blu-ray, billed as the "40th Anniversary Edition".[84][85] In 2020, new 2K digital restorations of the theatrical cut and special edition were included as part of the Bruce Lee: His Greatest Hits box set by The Criterion Collection (under licensed from Warner Bros. Home Entertainment through the physical home media joint venture in US and Canada named Studio Distribution Services, LLC. and Fortune Star Media Limited), which featured all of Lee's films, as well as Game of Death II.[86]

Legacy

The film has been parodied and referenced in places such as the 1976 film The Pink Panther Strikes Again, the satirical publication The Onion,[87] the Japanese game-show Takeshi's Castle, and the 1977 John Landis comedy anthology film Kentucky Fried Movie (in its lengthy "A Fistful of Yen" sequence, basically a comedic, note for note remake of Dragon) and also in the film Balls of Fury. It was also parodied on television in That '70s Show during the episode "Jackie Moves On" with regular character Fez taking on the Bruce Lee role. Several clips from the film are comically used during the theatre scene in The Last Dragon.

Lee's martial arts films were broadly lampooned in the recurring Almost Live! sketch Mind Your Manners with Billy Quan.

In August 2007, the now-defunct Warner Independent Pictures announced that television producer Kurt Sutter would be remaking the film as a noir-style thriller entitled Awaken the Dragon with Korean singer-actor Rain starring.[88][89][90] It was announced in September 2014 that Spike Lee would work on the remake. In March 2015, Brett Ratner revealed that he wanted to make the remake.[91][92] In July 2018, David Leitch is in early talks to direct the remake.[93]

Cultural impact

Enter the Dragon has been cited as one of the most influential action films of all time. Sascha Matuszak of Vice called it the most influential kung fu film and said it "is referenced in all manner of media, the plot line and characters continue to influence storytellers today, and the impact was particularly felt in the revolutionizing way the film portrayed African-Americans, Asians and traditional martial arts."[94] Joel Stice of Uproxx called it "arguably the most influential Kung Fu movie of all time."[95] Kuan-Hsing Chen and Beng Huat Chua cited its fight scenes as influential as well as its "hybrid form and its mode of address" which pitches "an elemental story of good against evil in such a spectacle-saturated way".[96] Hollywood filmmaker Quentin Tarantino cited Enter the Dragon as a formative influence on his career.[97]

According to Scott Mendelson of Forbes, Enter the Dragon contains spy film elements similar to the James Bond franchise. Enter the Dragon was the most successful action-spy film to not be part of the James Bond franchise; Enter the Dragon had an initial global box office comparable to the James Bond films of that era, and a lifetime gross surpassing every James Bond film up until GoldenEye (1995). Mendelson argues that, had Lee lived after Enter the Dragon was released, the film had the potential to launch an action-spy film franchise starring Lee that could have rivalled the success of the James Bond franchise.[98]

The film had an impact on mixed martial arts (MMA). In the opening fight sequence, where Lee fights Sammo Hung, Lee demonstrated elements of what would later become known as MMA. Both fighters wore what would later become common mixed martial arts clothing items, including kempo gloves and small shorts, and the fight ends with Lee utilizing an armbar (then used in judo and jiu jitsu) to submit Hung. According to UFC Hall of Fame fighter Urijah Faber, "that was the moment" that MMA was born.[99][100]

The Dragon Ball manga and anime franchise, debuted in 1984, was inspired by Enter the Dragon, which Dragon Ball creator Akira Toriyama was a fan of.[101][102] The title Dragon Ball was also inspired by Enter the Dragon,[101] and the piercing eyes of Goku's Super Saiyan transformation was based on Bruce Lee's paralysing glare.[103]

Enter the Dragon inspired early beat 'em up brawler games. It was cited by game designer Yoshihisa Kishimoto as a key inspiration behind Technōs Japan's brawler Nekketsu Kōha Kunio-kun (1986), released as Renegade in the West.[104][105] Its spiritual successor Double Dragon (1987) also drew inspiration from Enter the Dragon, with the game's title being a homage to the film.[104] Double Dragon also features two enemies named Roper and Williams, a reference to the two characters Roper and Williams from Enter the Dragon. The sequel Double Dragon II: The Revenge (1988) includes opponents named Bolo and Oharra.

Enter the Dragon was the foundation for fighting games.[106][107] The film's tournament plot inspired numerous fighting games.[108] The Street Fighter video game franchise, debuted in 1987, was inspired by Enter the Dragon, with the gameplay centered around an international fighting tournament, and each character having a unique combination of ethnicity, nationality and fighting style. Street Fighter went on to set the template for all fighting games that followed.[109] The little-known 1985 Nintendo arcade game Arm Wrestling contains voice leftovers from the film, as well as their original counterparts. The popular fighting game Mortal Kombat borrows multiple plot elements from Enter the Dragon, as does its movie adaptation.

See also

- Bruce Lee filmography

Notes

References

- "Enter the Dragon". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "Top 10 martial arts movies". The Guardian. 6 December 2013. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- FLANIGAN, b. p. (1 January 1974). "KUNG FU KRAZY: or The Invasion of the 'Chop Suey Easterns'". Cinéaste. 6 (3): 8–11. JSTOR 42683410.

- "Librarian of Congress Adds 25 Films to National Film Registry". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Fu, Poshek. "UI Press | Edited by Poshek Fu | China Forever: The Shaw Brothers and Diasporic Cinema". www.press.uillinois.edu. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- Kato, M. T. (1 January 2005). "Burning Asia: Bruce Lee's Kinetic Narrative of Decolonization". Modern Chinese Literature and Culture. 17 (1): 62–99. JSTOR 41490933.

- Horn, John (1 July 2013), "Jim Kelly, 'Enter the Dragon' star, dies at 67", Los Angeles Times, archived from the original on 22 April 2014, retrieved 19 August 2015

- Ryfle, Steve (10 January 2010). "DVD set is devoted to '70s martial arts star Jim Kelly". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- Cater, Dave. "Car Accident Claims Ahna Capri". Inside Kung Fu. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- "Lee's Dragon co-star dies at 96". BBC. 5 June 2009. Archived from the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- "Bob Wall Interview: "Pulling No Punches"". Black Belt. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- Bona, JJ (10 January 2011). "Bob Wall Interview". Cityonfire. cityonfire.com. Archived from the original on 22 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- Kim, Hyung-chan (1999). Distinguished Asian Americans: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 179. ISBN 9780313289026.

- Polly, Matthew (2019). Bruce Lee: A Life. Simon and Schuster. p. 478. ISBN 978-1-5011-8763-6. Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

Enter the Dragon struck a responsive chord across the globe. Made for a minuscule $850,000, it would gross $90 million worldwide in 1973 and go on to earn an estimated $350 million over the next forty-five years.

- Enter the dragon. WorldCat. OCLC 39222462. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- Locke, Brian (2009). Racial Stigma on the Hollywood Screen from World War II to the Present: The Orientalist Buddy Film. Springer. p. 71. ISBN 9780230101678.

- Brockett, Kip (12 August 2007). "Bruce Lee Said What? 'Finding the Truth in Bruce Lee's Writings'". Martialdirect.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2017.

- "Bully Busters Art of Fighting without Fighting". Nineblue.com. 12 August 2007. Archived from the original on 11 January 2008.

- "John Saxon, 'Enter the Dragon' Star, Dies At 83". www.wingchunnews.ca. 26 July 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- "City On Fire (audio commentatary)". Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- "New Bruce Lee Film on its way to American movie theatres". Black Belt magazine. 11 (4): 11–12. April 1973. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- Inc, Active Interest Media (1 August 1973). "Black Belt". Active Interest Media, Inc. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2018 – via Google Books.

- Walker, David , Andrew J. Rausch, Chris Watson (2009). Reflections on Blaxploitation: Actors and Directors Speak. Scarecrow Press. p. 112. ISBN 9780810867062.

- "John Saxon, best known for his roles in Enter the Dragon, A Nightmare on Elm Street, dies at 83". www.firstpost.com. 27 July 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- Clary, David (May 1992). Black Belt Magazine. Active Interest Media, Inc. pp. 18–21. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- Reflections on Blaxploitation: Actors and Directors Speak, 2009. pps.129–130 Archived 7 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Boutwell, Malcolm (7 July 2015). "Those Amazing Bruce Lee Film Stunts". ringtalk.com. Archived from the original on 30 November 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- "Bruce Lee Movies: Enter the Dragon, Seen Through the Eyes of a Martial Arts Movies Expert". 13 May 2013. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- Thomas, Bruce (2008). Bruce Lee: Fighting Spirit. Pan Macmillan. p. 300. ISBN 9780283070662.

- "Enter the Dragon Movie Shooting Locations". filmapia.com. Archived from the original on 25 March 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- "Enter The Dragon / 龍爭虎鬥 (1973 / Dir: Robert Clouse)". www.hkcinemagic.com. 18 September 2011. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- Guarisco, Donald. "Lalo Schifrin: Enter the Dragon [Music from the Motion Picture] – Review". All Music Guide. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- Peirano, Pierre-François (22 April 2013). "The Multiple Facets of Enter the Dragon (Robert Clouse, 1973)". InMedia. The French Journal of Media and Media Representations in the English-Speaking World (3). doi:10.4000/inmedia.613. ISSN 2259-4728. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- "Enter The Dragon (1973)". IMDb. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- Lewis, Dan (22 April 1973). "Newest Movie Craze: Chinese Agents". Lima News. p. 30. Retrieved 15 April 2022 – via NewspaperArchive.

Warner Brothers has just released one called "The Five Fingers of Death" and, with Fred Weintraub as producer, is now involved in the first American-Chinese production of a martial-science picture, a film that stars Bruce (Kato) Lee (...) "Enter the Dragon," is budgeted at $1 million. The first two pictures grossed more than $5 million in Southeast Asia alone, according to Weintraub. He also said American distributors are offering as much as $500,000 in advance for distribution rights.

- "50 Top-Grossing Films". Variety. 29 August 1973. p. 9.

- "3 Days, 4 Sites, 'Dragon', $140,010". Variety. 22 August 1973. p. 8.

- "50 Top-Grossing Films". Variety. 12 September 1973. p. 13.

- Desser, David (2002). "The Kung Fu Craze: Hong Kong Cinema's First American Reception". In Fu, Poshek; Desser, David (eds.). The Cinema of Hong Kong: History, Arts, Identity. Cambridge University Press. pp. 19–43 (34). ISBN 978-0-521-77602-8. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- "«Выход Дракона» (Enter the Dragon, 1973) - Dates". Kinopoisk (in Russian). Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- Eliot, Marc (2011). Steve McQueen: A Biography. Aurum Press. pp. 237, 242. ISBN 978-1-84513-744-1. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

Papillon earned nearly $55 million in its initial domestic release, making it the third-highest-grossing film of the year. (...) Robert Clouse's Enter the Dragon, starring the late Bruce Lee, came in fourth, with $25 million.

- Polly, Matthew (2019). Bruce Lee: A Life. Simon and Schuster. p. 479. ISBN 978-1-5011-8763-6. Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Lent, John A. (1990). The Asian Film Industry. Helm. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-7470-2000-4. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

The Lee film, Enter the Dragon, was made with Warner; it grossed US $100 million in the United States alone (Sun 1982: 40).

- Mennel, Barbara (2008). Cities and Cinema. Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-134-21984-1. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

Golden Harvest took on Bruce Lee and began co-producing with Hollywood companies, leading to its kung-fu action films, including the Bruce Lee vehicle Enter the Dragon (dir. Robert Clouse, 1973), which “grossed US $100 million in the United States alone” (Lent 100; also Sun 1982:40).

- Gaul, Lou (20 July 1998). "Actor Bruce Lee's life celebrated in special video edition". Doylestown Intelligencer. p. 28. Retrieved 15 April 2022 – via NewspaperArchive.

The $550,000 picture – a modest budget even by 1973 standards – has grossed more than $120 million during its initial run and re-release engagements in America and has never aired on network television.

- Thomas, Bruce (1994). Bruce Lee, Fighting Spirit: A Biography. Berkeley, California: Frog Books. p. 247. ISBN 9781883319250.

A month after Bruce's death, Enter the Dragon was released. During its first seven weeks in the United States it grossed $3 million. In London it monopolized three West End cinemas for five weeks before becoming a sellout throughout Britain and the rest of Europe. The film went on to gross over $200 million, the ratio of cost to profit making it perhaps the most commercially successful film ever made.

- Soyer, Renaud (22 April 2014). "Box Office International 1973". Box Office Story (in French). Archived from the original on 29 June 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Soyer, Renaud (28 January 2013). "Bruce Lee Box Office". Box Office Story (in French). Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- "Charts – LES ENTREES EN FRANCE". JP's Box-Office (in French). 1974. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- "Charts – LES ENTREES EN ALLEMAGNE". JP's Box-Office (in French). 1974. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- Tan, George (November 1990). "Behind The Scenes With Bruce Lee: An Inside Look at "The Dragon's" Films". Black Belt. Vol. 28, no. 11. Active Interest Media. pp. 24–29 (29). Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "キネマ旬報ベスト・テン85回全史 1924–2011". Kinema Junpo (in Japanese). 2012. p. 322.

- "영화정보". KOFIC. Korean Film Council. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- Mohamed, Khalid (15 September 1979). "Bruce Lee storms Bombay once again with Return of the Dragon". India Today. Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- Gross, Edward (1990). Bruce Lee: Fists of Fury. Pioneer Books. p. 137. ISBN 9781556982330. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

In 1973, his third (sic) Enter the Dragon, grossed $100 million world-wide and firmly established young Lee as an international star whose films were almost guaranteed to be successful.

- Waugh, Darin, ed. (1978). "British Newspaper Clippings – Showtalk: The King Lives". Bruce Lee Eve: The Robert Blakeman Bruce Lee Memorabilia Collection Logbook, and Associates of Bruce Lee Eve Newsletters. Kiazen Publications. ISBN 978-1-4583-1893-0. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

Lee first found success in The Big Boss and followed that with Fist of Fury and Enter the Dragon which grossed an outstanding 100,000,000 dollars and firmly established itself as one of the world's all-time top films in commercial terms. Lee went on to top this with The Way of the Dragon and the cameras had barely stopped rolling when he began what was to be his final film Game of Death. (...) Now director Robert Clouse has completed Game of Death.

- Hoffmann, Frank W.; Bailey, William G.; Ramirez, Beulah B. (1990). Arts & Entertainment Fads. Psychology Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-86656-881-4. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

American moviemakers already knew the potential of the martial arts film; in 1973 “Enter the Dragon,” starring Bruce Lee, earned Fred Weintraub and Raymond Chow $100,000,000 worldwide. Of that amount $11,000,000 came from U.S. sales, indicating the market was really overseas.

- Hamberger, Mitchell G. (1 December 1981). "Bruce Lee remembered". York Daily Record. p. 6. Retrieved 16 April 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

His biggest and best film Enter the Dragon, grossed over $220 million internationally. That's more than any martial arts film has ever grossed.

- "The Turtles Take Hollywood". Asiaweek. Asiaweek Limited. 16. May 1990. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

Lee's 1973 film Enter the Dragon is said to be one of the 50 top-grossing films of all time.

- "Immortal Kombat". Vibe. Vibe Media Group. 6 (8): 90–94 (94). August 1998. ISSN 1070-4701. Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

Bruce's own production company, Concord, was a full partner with Warner Bros, in his final, and greatest film, Enter the Dragon. Made for just $600,000, it has since grossed more than $300 million.

- Wilson, Wayne (2001). Bruce Lee. Mitchell Lane Publishers. pp. 30–1. ISBN 978-1-58415-066-4.

After its release, Enter the Dragon became Warner Brothers' highest grossing movie of 1973. It has earned well over $400 million

- Bishop, James (1999). Remembering Bruce: The Enduring Legend of the Martial Arts Superstar. Cyclone Books. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-890723-21-7. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

Three weeks after Bruce Lee died Enter the Dragon was released in the United States and became an instant hit. The movie, made for around $800,000, made $3 million in its first seven weeks. Its success spread to Europe and then worldwide. It would eventually make over $200 million, making it one of the most profitable movies of all time.

- Risen, Clay (11 February 2022). "Bob Wall, Martial Arts Master Who Sparred With Bruce Lee, Dies at 82". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- Chachowski, Richard (21 March 2022). "The Best Kung Fu Movies Of All Time Ranked". Looper.com. Static Media. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- Variety Staff (31 July 1973). "Review: 'Enter the Dragon'". Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- "The Greatest Films of 1973". AMC Filmsite.org. Archived from the original on 10 February 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- "The Best Movies of 1973 by Rank". Films101.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- "Most Popular Feature Films Released in 1973". IMDb. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- Enter the Dragon, TV Guide Movie Review. Archived 4 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine TV Guide. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- The Fourth Virgin Film Guide by James Pallot and the editors of Cinebooks, published by Virgin Books, 1995

- Hong Kong Action Cinema by Bey Logan, published by Titan Books, 1995

- Maçek III, J.C. (21 June 2013). "Tournament of Death, Tour de Force: 'Enter the Dragon: 40th Anniversary Edition Blu-Ray'". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 30 June 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- "Review: 'Enter the Dragon'". Variety. 31 July 1973. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- Thompson, Howard (18 August 1973). "Movie Review - - 'Enter Dragon,' Hollywood Style:The Cast". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- "Enter the Dragon". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 15 July 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- "Enter the Dragon". Metacritic. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- "Enter the Dragon: Award Wins and Nominations". IMDb. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- "Empire's The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire magazine. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- "BBFC Case Studies: Enter the Dragon (1973)". bbfc.co.uk. British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on 16 December 2018. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- "Enter the Dragon: Bruce Lee vs the BBFC". Melonfarmers.co.uk. MelonFarmers. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- Cutting Edge: Episode 46 - Enter The Dragon. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- "Enter the Dragon (1973) DVD comparison". DVDCompare. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- "Enter the Dragon (1973) Blu-ray comparison". DVDCompare. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- Lattanzio, Ryan (13 April 2020). "Bruce Lee Will Make His Criterion Collection Debut This Summer with Greatest Hits Set". IndieWire. Archived from the original on 16 May 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "Rumsfeld Hosts No-Holds-Barred Martial Arts Tournament at Remote Island Fortress". The Onion. 17 March 2004. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 15 August 2007.

- Fleming, Michael (9 August 2007). "Warners to remake 'Enter the Dragon'". Variety. Archived from the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- CS (5 August 2009). "Will Rain Awaken the Dragon ?". ComingSoon.net. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Rich, Kathy (13 November 2009). "Exclusive: Rain Confirms He's Still Considering Enter The Dragon Remake". Cinema Blend. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Sternberger, Chad (16 September 2014). "SPIKE LEE TO REMAKE ENTER THE DRAGON". The Studio Exec. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- mrbeaks (21 March 2015). "Brett Ratner Is Trying To Remake ENTER THE DRAGON". Ain't It Cool News. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Mike Fleming, Jr (23 July 2018). "Remake Of Bruce Lee's 'Enter The Dragon' Has 'Deadpool 2's David Leitch in Talks". Deadline. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- Matuszak, Sascha (1 July 2015). "Bruce Lee's Last Words: Enter the Dragon and the Martial Arts Explosion". Vice. Archived from the original on 2 January 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Stice, Joel (27 November 2015). "Bruce Lee Was Bitten By A Cobra And 5 Other Surprising 'Enter The Dragon' Facts". Uproxx. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Chen, Kuan-Hsing; Chua, Beng Huat (2015). The Inter-Asia Cultural Studies Reader. Routledge. p. 489. ISBN 978-1-134-08396-1. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Fitzmaurice, Larry (28 August 2015). "Quentin Tarantino: The Complete Syllabus of His Influences and References". Vulture.com. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Mendelson, Scott (15 September 2020). "How Bruce Lee's Death Impacted The James Bond Movies". Forbes. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Scott, Mathew (21 May 2019). "Bruce Lee and his starring role in the birth of modern mixed martial arts". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- Robles, Pablo; Wong, Dennis; Scott, Mathew (21 May 2019). "How Bruce Lee and street fighting in Hong Kong helped create MMA". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- "Akira Toriyama × Katsuyoshi Nakatsuru". TV Anime Guide: Dragon Ball Z Son Goku Densetsu. Shueisha. 2003. ISBN 4088735463. Archived from the original on 3 September 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- The Dragon Ball Z Legend: The Quest Continues. DH Publishing Inc. 2004. p. 7. ISBN 9780972312493.

- "Comic Legends: Why Did Goku's Hair Turn Blonde?". Comic Book Resources. 1 January 2018. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Leone, Matt (12 October 2012). "The man who created Double Dragon". Polygon. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- Williams, Andrew (16 March 2017). History of Digital Games: Developments in Art, Design and Interaction. CRC Press. pp. 143–6. ISBN 978-1-317-50381-1.

- Kapell, Matthew Wilhelm (2015). The Play Versus Story Divide in Game Studies: Critical Essays. McFarland & Company. p. 166. ISBN 978-1-4766-2309-2. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Stuart, Keith (9 April 2014). "Bruce Lee, UFC and why the martial arts star is a video game hero". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Gill, Patrick (24 September 2020). "Street Fighter and basically every fighting game exist because of Bruce Lee". Polygon. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- Thrasher, Christopher David (2015). Fight Sports and American Masculinity: Salvation in Violence from 1607 to the Present. McFarland. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-4766-1823-4. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

External links

- Enter the Dragon essay by Michael Sragow at National Film Registry

- Enter the Dragon essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 694-696

- Enter the Dragon at IMDb

- Enter the Dragon at the Hong Kong Movie DataBase

- Enter the Dragon at AllMovie

- Enter the Dragon at Box Office Mojo