Erection

An erection (clinically: penile erection or penile tumescence) is a physiological phenomenon in which the penis becomes firm, engorged, and enlarged. Penile erection is the result of a complex interaction of psychological, neural, vascular, and endocrine factors, and is often associated with sexual arousal or sexual attraction, although erections can also be spontaneous. The shape, angle, and direction of an erection varies considerably between humans.

| Erection | |

|---|---|

Three columns of erectile tissue make up most of the volume of the penis. | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D010410 |

| TE | E1.0.0.0.0.0.8 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

| Erection blood vessels | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D010410 |

| TE | E1.0.0.0.0.0.8 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

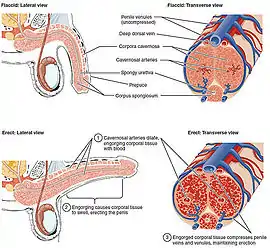

Physiologically, an erection is required for a male to effect vaginal penetration or sexual intercourse and is triggered by the parasympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system, causing the levels of nitric oxide (a vasodilator) to rise in the trabecular arteries and smooth muscle of the penis. The arteries dilate causing the corpora cavernosa of the penis (and to a lesser extent the corpus spongiosum) to fill with blood; simultaneously the ischiocavernosus and bulbospongiosus muscles compress the veins of the corpora cavernosa restricting the egress and circulation of this blood. Erection subsides when parasympathetic activity reduces to baseline.

As an autonomic nervous system response, an erection may result from a variety of stimuli, including sexual stimulation and sexual arousal, and is therefore not entirely under conscious control. Erections during sleep or upon waking up are known as nocturnal penile tumescence (NPT), also known as "morning wood". Absence of nocturnal erection is commonly used to distinguish between physical and psychological causes of erectile dysfunction and impotence.

The state of a penis which is partly, but not fully, erect is sometimes known as semi-erection (clinically: partial tumescence); a penis which is not erect is typically referred to as being flaccid, or soft.

Physiology

An erection is necessary for natural insemination as well as for the harvesting of sperm for artificial insemination, are common for children and infants, and even occur before birth.[1] After reaching puberty, erections occur much more frequently.[2][3] it occurs when two tubular structures, called the corpora cavernosa, that run the length of the penis, become engorged with venous blood. This may result from any of various physiological stimuli, also known as sexual stimulation and sexual arousal. The corpus spongiosum is a single tubular structure located just below the corpora cavernosa, which contains the urethra, through which urine and semen pass during urination and ejaculation respectively. This may also become slightly engorged with blood, but less so than the corpora cavernosa.

The scrotum may, but does not always, become tightened during erection. Generally, in uncircumcised males, the foreskin automatically and gradually retracts, exposing the glans, though some people may have to manually retract their foreskin.

Autonomic control

In the presence of mechanical stimulation, erection is initiated by the parasympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system with minimal input from the central nervous system. Parasympathetic branches extend from the sacral plexus into the arteries supplying the erectile tissue; upon stimulation, these nerve branches release acetylcholine, which in turn causes release of nitric oxide from endothelial cells in the trabecular arteries.[4] Nitric oxide diffuses to the smooth muscle of the arteries (called trabecular smooth muscle[5]), acting as a vasodilating agent.[6] The arteries dilate, filling the corpus spongiosum and corpora cavernosa with blood. The ischiocavernosus and bulbospongiosus muscles also compress the veins of the corpora cavernosa, limiting the venous drainage of blood.[7] Erection subsides when parasympathetic stimulation is discontinued; baseline stimulation from the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system causes constriction of the penile arteries and cavernosal sinosoids, forcing blood out of the erectile tissue via erection-related veins which include one deep dorsal vein, a pair of cavernosal veins, and two pairs of para-arterial veins between Buck's fascia and the tunica albuginea.[8][9] Erection rigidity is mechanically controlled by reduction blood flow via theses veins, and thereby building up the pressure of the corpus cavernosum and corpus spongiosum, an integral instructure, the distal ligament, buttresses the glans penis.[10]

After ejaculation or cessation of stimulation, erection usually subsides, but the time taken may vary depending on the length and thickness of the penis.[11]

Voluntary and involuntary control

The cerebral cortex can initiate erection in the absence of direct mechanical stimulation (in response to visual, auditory, olfactory, imagined, or tactile stimuli) acting through erectile centers in the lumbar and sacral regions of the spinal cord.[12] The cortex may suppress erection, even in the presence of mechanical stimulation, as may other psychological, emotional, and environmental factors.[13]

Nocturnal erection

The penis may become erect during sleep or be erect on waking up. Such an erection is medically known as nocturnal penile tumescence (informally: morning wood or morning glory).[14][15][16][17]

Urination

Urinating with an erection can be more difficult than without. David Samadi, director of men's health at St. Francis Hospital in Long Island, says "To prevent semen from entering into the bladder, the internal urethral sphincter contracts."[18] This also works in opposite way, making it less likely that urine will pass through the urethra with an erect penis. Combined with morning wood, and a full bladder from overnight, many people may have experience with the extra challenge that comes with the combination.

Medical recommendations include:

- Waiting for the erection to go away, including techniques for relaxing

- Peeing while bending over or sitting down

- Massaging, or putting light pressure or a hot compress on the bladder (from the outside, between the navel and the pubic bone)[18]

Socio-sexual aspects

Social

Though an erection can have many causes, the more common indicator of sexual arousal has a prevalent view over society and its portrayal in public is considered taboo in many societies, probably lesser than public sex but higher than nudity. Erectile dysfunction is considered a flaw that associates shame at the individual and his partner.

The penile plethysmograph, which measures erections, has been used by some governments and courts of law to measure sexual orientation. An unusual aversion to the erect penis is sometimes referred to as phallophobia.

Spontaneous or random erections

Spontaneous erections, also known as involuntary, random or unwanted erections, are commonplace and a normal part of male physiology. Socially, such erections can be embarrassing if they happen in public or when undesired.[2] Such erections can occur at any time of day, and if clothed may cause a bulge which (if required) can be disguised or hidden by wearing close-fitting underwear, a long shirt, or baggier clothes.[19] Few slang terms associated with erect penis outline becoming visible from underneath clothing are mooseknuckle[20] and manbulge.

Size

The length of the flaccid penis is not necessarily indicative of the length of the penis when it becomes erect, with some smaller flaccid penises growing much longer, and some larger flaccid penises growing comparatively less.[21] Generally, the size of an erect penis is fixed throughout post-pubescent life. Its size may be increased by surgery,[22] although penile enlargement is controversial, and a majority of men were "not satisfied" with the results, according to one study.[23]

Though the size of a penis varies considerably between males, the average length of an erect human penis is 13.12 cm (5.17 inches), while the average circumference of an erect human penis is 11.66 cm (4.59 inches).[24]

Direction

Although many erect penises point upwards, it is common and normal for the erect penis to point nearly vertically upwards or horizontally straight forward or even nearly vertically downwards, all depending on the tension of the suspensory ligament that holds it in position. An erect penis can also take on a number of different shapes, ranging from a straight tube to a tube with a curvature up or down or to the left or right. An increase in penile curvature can be caused by Peyronie's disease. This may cause physical and psychological effects for the affected individual, which could include erectile dysfunction or pain during an erection. Treatments include oral medication (such as colchicine) or surgery, which is most often performed only as a last resort.

The following table shows how common various erection angles are for a standing male. In the table, zero degrees (0°) is pointing straight up against the abdomen, 90° is horizontal and pointing straight forward, and 180° is pointing straight down to the feet. An upward pointing angle is most common and the average erection angle is 74.3 degrees. The penile curvature was measured same time. 63% men have straight penis. 22.2% men have upwards curvature and 14.8% men have downwards curvature.[25]

| Angle (°) | Percent of population |

|---|---|

| 0–30 | 4.9 |

| 30–60 | 29.6 |

| 60–85 | 30.9 |

| 85–95 | 9.9 |

| 95–120 | 19.8 |

| 120–180 | 4.9 |

Medical conditions

Erectile dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction (also known as ED or "(male) impotence") is a sexual dysfunction characterized by the inability to develop and/or maintain an erection.[26][27] The study of erectile dysfunction within medicine is known as andrology, a sub-field within urology.[28]

Erectile dysfunction may occur due to physiological or psychological reasons, most of which are amenable to treatment. Common physiological reasons include diabetes, kidney disease, chronic alcoholism, multiple sclerosis, atherosclerosis, vascular disease, including arterial insufficiency and venogenic erectile dysfunction,[29] and neurologic disease which collectively account for about 70% of ED cases.[6] Some drugs used to treat other conditions, such as lithium and paroxetine, may cause erectile dysfunction.[27][30]

Erectile dysfunction, tied closely as it is to cultural notions of potency, success and masculinity, can have devastating psychological consequences including feelings of shame, loss or inadequacy.[31] There is a strong culture of silence and inability to discuss the matter. Around one in ten men experience recurring impotence problems at some point in their lives.[32]

Priapism

Priapism is a painful condition in which the penis does not return to its flaccid state, despite the absence of both physical and psychological stimulation. Priapism lasting over four hours is a medical emergency.

In non-human animals

_na_sajmu_MESAP_2015.jpg.webp)

At the time of penetration, the canine penis is not erect, and only able to penetrate the female because it includes a narrow bone called the baculum, a feature of most placental mammals. After the male achieves penetration, he will often hold the female tighter and thrust faster, and it is during this time that the male's penis expands. Unlike human sexual intercourse, where the male penis commonly becomes erect before entering the female, canine copulation involves the male first penetrating the female, after which swelling of the penis to erection occurs.[33]

An elephant's penis is S-shaped when fully erect and has a Y-shaped orifice.[34]

Given the small amount of erectile tissue in a bull's penis, there is little enlargement after erection. The penis is quite rigid when non-erect, and becomes even more rigid during erection. Protrusion is not affected much by erection, but more by relaxation of the retractor penis muscle and straightening of the sigmoid flexure.[35][36]

A male fossa's penis reaches to between his forelegs when erect.[37]

When not erect, a horse's penis is housed within the prepuce, 50 centimetres (20 in) long and 2.5 to 6 centimetres (0.98 to 2.36 in) in diameter with the distal end 15 to 20 centimetres (5.9 to 7.9 in). The retractor muscle contracts to retract the penis into the sheath and relaxes to allow the penis to extend from the sheath.[38] When erect, the penis doubles in length[39] and thickness and the glans increases by 3 to 4 times.[38] Erection and protrusion take place gradually, by the increasing tumescence of the erectile vascular tissue in the corpus cavernosum penis.[40][41] Most stallions achieve erection within 2 minutes of contact with an estrus mare, and mount the estrus mare 5–10 seconds afterward.[42]

A bird penis is different in structure from mammal penises, being an erectile expansion of the cloacal wall and being erected by lymph, not blood.[43] The penis of the lake duck can reach about the same length as the animal himself when fully erect, but more commonly is about half the bird's length.[44][45]

Terminology

Clinically, erection is often known as "penile erection", and the state of being erect, and process of erection, are described as "tumescence" or "penile tumescence". The term for the subsiding or cessation of an erection is "detumescence".

Colloquially and in slang, erection is known by many informal terms. Commonly encountered English terms include 'stiffy', 'hard-on', 'boner' and 'woody'.[46] There are several slang words, euphemisms and synonyms for an erection in English and in other languages. (See also The WikiSaurus entry.)

See also

- Clitoral erection

- Cock ring

- Death erection

- Human penis

- Issues in social nudity

- Nipple stimulation

- Nocturnal penile tumescence

- Priapism

- Sexual function

References

- erections in babies retrieved 11 February 2012

- Lynda Madaras (8 June 2007). What's Happening to My Body? Book for Boys: Revised Edition. Newmarket Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-55704-769-4. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- Goldblatt, Howard (1990). Worlds Apart: Recent Chinese Writing and Its Audiences. p. 56.

- wiley.com > Viagra function image Retrieved on Mars 11, 2010

- APDVS > 31. Anatomy and Physiology of Normal Erection Retrieved on Mars 11, 2010

- Marieb, Elaine (2013). Anatomy & physiology. Benjamin-Cummings. p. 895. ISBN 9780321887603.

- Moore, Keith; Anne Agur (2007). Essential Clinical Anatomy, Third Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-7817-6274-8.

- Drake, Richard, Wayne Vogl and Adam Mitchell, Grey's Anatomy for Students. Philadelphia, 2004. (ISBN 0-443-06612-4)

- Hsu, Geng-Long; Liu, Shih-Ping (2018). "Penis Structure". Encyclopedia of Reproduction. Academic Press. pp. 357–366. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.64602-0. ISBN 9780128151457.

- Hsu, Geng-Long; Lu, Hsiu-Chen (2018). Penis Structure-Erection. Academic Press. pp. 367–375. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.64603-2. ISBN 9780128151457.

- Harris, Robie H. (et al.), It's Perfectly Normal: Changing Bodies, Growing Up, Sex And Sexual Health. Boston, 1994. (ISBN 1-56402-199-8)

- Rubin, H. B.; Henson, Donald E. (1975). "Voluntary enhancement of penile erection" (PDF). Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society. 6 (2): 158–160. doi:10.3758/BF03333178. S2CID 144906565.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "How to stop an unwanted erection: 7 remedies". Medical News Today. 2018-01-04. Retrieved 2021-10-22.

- Morning Erections: Sizemed retrieved 28 February 2012

- After Prostate Cancer: A What-Comes-Next Guide to a Safe and Informed recovery: p.48

- Listen To Your Hormones, Abraham Harvey Kryger - 2004. p.32

- Janell L. Carroll (29 January 2009). Sexuality Now: Embracing Diversity: Embracing Diversity. Cengage Learning. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-495-60274-3.

- Santos-Longhurst, Adrienne (8 July 2020). "Sorry, Peeing with an Erection Isn't 'More Difficult Than Childbirth'". Healthline. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- Sarah Attwood (15 May 2008). Making Sense of Sex: A Forthright Guide to Puberty, Sex and Relationships for People with Asperger's Syndrome. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-84642-797-8. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- "moose knuckle Meaning & Origin | Slang by". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2022-07-19.

- "Penis Size FAQ & Bibliography". Kinsey Institute. 2009. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- Li CY, Kayes O, Kell PD, Christopher N, Minhas S, Ralph DJ (2006). "Penile suspensory ligament division for penile augmentation: indications and results". Eur. Urol. 49 (4): 729–733. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2006.01.020. PMID 16473458.

- "Most Men Unsatisfied With Penis Enlargement Results". Fox News. 2006-02-16. Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- "Is Your Penis Normal? There's a Chart for That - RealClearScience".

- Sparling J (1997). "Penile erections: shape, angle, and length". Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 23 (3): 195–207. doi:10.1080/00926239708403924. PMID 9292834.

- Milsten, Richard (et al.), The Sexual Male. Problems And Solutions. London, 2000. (ISBN 0-393-32127-4)

- Sadeghipour H, Ghasemi M, Ebrahimi F, Dehpour AR (2007). "Effect of lithium on endothelium-dependent and neurogenic relaxation of rat corpus cavernosum: role of nitric oxide pathway". Nitric Oxide. 16 (1): 54–63. doi:10.1016/j.niox.2006.05.004. PMID 16828320.

- Williams, Warwick, It's Up To You: Overcoming Erection Problems. London, 1989. (ISBN 0-7225-1915-X)

- Hsu, Geng-Long (2018). "Erection Abnormality". Encyclopedia of Reproduction. Academic Press. pp. 382–390. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.64374-X. ISBN 9780128151457.

- Sadeghipour H, Ghasemi M, Nobakht M, Ebrahimi F, Dehpour AR (2007). "Effect of chronic lithium administration on endothelium-dependent relaxation of rat corpus cavernosum: the role of nitric oxide and cyclooxygenase pathways". BJU Int. 99 (1): 177–182. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06530.x. PMID 17034495.

- Tanagho, Emil A. (et al.), Smith's General Urology. London, 2000. (ISBN 0-8385-8607-4)

- "Erectile dysfunction (impotence)". nhs.uk. 2017-11-13.

- "Semen Collection from Dogs". Arbl.cvmbs.colostate.edu. 2002-09-14. Archived from the original on 2012-02-05. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- Shoshani, p. 80.

- William O. Reece (4 March 2009). Functional Anatomy and Physiology of Domestic Animals. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-8138-1451-3. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- James R. Gillespie; Frank Bennie Flanders (28 January 2009). Modern Livestock & Poultry Production. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4283-1808-3. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- Köhncke, M.; Leonhardt, K. (1986). "Cryptoprocta ferox" (PDF). Mammalian Species (254): 1–5. doi:10.2307/3503919. JSTOR 3503919. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- "The Stallion: Breeding Soundness Examination & Reproductive Anatomy". University of Wisconsin-Madison. Archived from the original on 2007-07-16. Retrieved 7 July 2007.

- James Warren Evans (15 February 1990). The Horse. W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-1811-6. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- Sarkar, A. (2003). Sexual Behaviour In Animals. Discovery Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-7141-746-9.

- Juan C. Samper, Ph.D.; Jonathan F. Pycock, Ph.D.; Angus O. McKinnon (2007). Current Therapy in Equine Reproduction. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-7216-0252-3. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- Juan C. Samper (2009). Equine Breeding Management and Artificial Insemination. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1-4160-5234-0. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- Frank B. Gill (6 October 2006). Ornithology. Macmillan. pp. 414–. ISBN 978-0-7167-4983-7. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- McCracken, Kevin G. (2000). "The 20-cm Spiny Penis of the Argentine Lake Duck (Oxyura vittata)" (PDF). The Auk. 117 (3): 820–825. doi:10.2307/4089612. JSTOR 4089612.

- McCracken, Kevin G.; Wilson, Robert E.; McCracken, Pamela J.; Johnson, Kevin P. (2001). "Sexual selection: Are ducks impressed by drakes' display?" (PDF). Nature. 413 (6852): 128. Bibcode:2001Natur.413..128M. doi:10.1038/35093160. PMID 11557968.

- Gabrielle Morrissey (27 January 2005). Urge: Hot Secrets For Great Sex. HarperCollins Publishers. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-7304-4527-2. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

.jpg.webp)