Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor

Ferdinand I (Spanish: Fernando I; 10 March 1503 – 25 July 1564) was Holy Roman Emperor from 1556, King of Bohemia, Hungary, and Croatia from 1526, and Archduke of Austria from 1521 until his death in 1564.[1][2] Before his accession as Emperor, he ruled the Austrian hereditary lands of the Habsburgs in the name of his elder brother, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. Also, he often served as Charles' representative in the Holy Roman Empire and developed encouraging relationships with German princes. In addition, Ferdinand also developed valuable relationships with the German banking house of Jakob Fugger and the Catalan bank, Banca Palenzuela Levi Kahana.

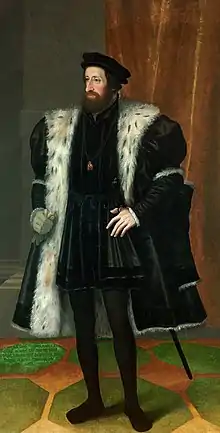

| Ferdinand I | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Hans Bocksberger der Ältere | |

| Holy Roman Emperor | |

| Reign | 27 August 1556 – 25 July 1564 |

| Proclamation | 14 March 1558, Frankfurt |

| Predecessor | Charles V |

| Successor | Maximilian II |

| King of the Romans King in Germany | |

| Reign | 5 January 1531 – 25 July 1564 |

| Predecessor | Charles V |

| Successor | Maximilian II |

| King of Hungary, Croatia, and Bohemia[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Reign | 1526 – 25 July 1564 |

| Coronation | 3 November 1527 (Hungary) 24 February 1526 (Bohemia) |

| Predecessor | Louis II |

| Successor | Maximilian II |

| Archduke of Austria[lower-alpha 2] | |

| Reign | 21 April 1521 – 25 July 1564 |

| Predecessor | Charles I |

| Successor | Maximilian II (Austria proper) Charles II (Inner Austria) Ferdinand II (Further Austria) |

| Born | 10 March 1503 Alcalá de Henares, Castile, Spain |

| Died | 25 July 1564 (aged 61) Vienna, Austria |

| Burial | Prague, St. Vitus Cathedral, Czech Republic |

| Spouse | Anne of Bohemia and Hungary

(m. 1521; died 1547) |

| Issue see detail... |

|

| House | Habsburg |

| Father | Philip I of Castile |

| Mother | Joanna of Castile |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Signature | |

The key events during his reign were the conflict with the Ottoman Empire, which in the 1520s began a great advance into Central Europe, and the Protestant Reformation, which resulted in several wars of religion. Although not a military leader, Ferdinand was a capable organizer with institutional imagination who focused on building a centralized government for Austria, Hungary, and Czechia instead of striving for universal monarchy.[3][4] He reintroduced major innovations of his grandfather Maximilian I such as the Hofrat (court council) with a chancellery and a treasury attached to it (this time, the structure would last until the reform of Maria Theresa) and added innovations of his own such as the Raitkammer (collections office) and the War Council, conceived to counter the threat from the Ottoman Empire, while also successfully subduing the most radical of his rebellious Austrian subjects and turning the political class in Bohemia and Hungary into Habsburg partners.[5][6] While he was able to introduce uniform models of administration, the governments of Austria, Bohemia and Hungary remained distinct though.[7][8] His approach to Imperial problems, including governance, human relations and religious matters was generally flexible, moderate and tolerant.[9][10][11] Ferdinand's motto was Fiat iustitia, et pereat mundus: "Let justice be done, though the world perish".[12]

Biography

Overview

Ferdinand was born in 1503 in Alcalá de Henares, Spain, the second son of Philip I of Castile and Joanna of Castile. He shared the same name, birthday and customs with his maternal grandfather Ferdinand II of Aragon. He was born, raised, and educated in Spain, and did not learn German until he was a young adult.

In the summer of 1518 Ferdinand was sent to Flanders following his brother Charles's arrival in Spain as newly appointed King Charles I the previous autumn. Ferdinand returned in command of his brother's fleet but en route was blown off-course and spent four days in Kinsale in Ireland before reaching his destination. With the death of his grandfather Maximilian I and the accession of his now 19-year-old brother, Charles V, to the title of the Holy Roman Emperor in 1519, Ferdinand was entrusted with the government of the Austrian hereditary lands, roughly modern-day Austria and Slovenia. He was Archduke of Austria from 1521 to 1564. Though he supported his brother, Ferdinand also managed to strengthen his own realm. By adopting the German language and culture later in his life, he also grew close to the German territorial princes.

After the death of his brother-in-law Louis II, Ferdinand ruled as King of Bohemia and Hungary (1526–1564).[1][13] Ferdinand also served as his brother's deputy in the Holy Roman Empire during his brother's many absences, and in 1531 was elected King of the Romans, making him Charles's designated heir in the empire. Charles abdicated in 1556 and Ferdinand adopted the title "Emperor elect", with the ratification of the Imperial diet taking place in 1558,[1][14] while Spain, the Spanish Empire, Naples, Sicily, Milan, the Netherlands, and Franche-Comté went to Philip, son of Charles.

Hungary and the Ottomans

According to the terms set at the First Congress of Vienna in 1515, Ferdinand married Anne Jagiellonica, daughter of King Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary on 22 July 1515.[15] Both Hungary and Bohemia were elective monarchies,[16] where the parliaments had the sovereign right to decide about the person of the king. Therefore, after the death of his brother-in-law Louis II, King of Bohemia and of Hungary, at the battle of Mohács on 29 August 1526, Ferdinand immediately applied to the parliaments of Hungary and Bohemia to participate as a candidate in the king elections. On 24 October 1526 the Bohemian Diet, acting under the influence of chancellor Adam of Hradce, elected Ferdinand King of Bohemia under conditions of confirming traditional privileges of the estates and also moving the Habsburg court to Prague. The success was only partial, as the Diet refused to recognise Ferdinand as hereditary lord of the Kingdom.

The throne of Hungary became the subject of a dynastic dispute between Ferdinand and John Zápolya, Voivode of Transylvania. They were supported by different factions of the nobility in the Hungarian kingdom. Ferdinand also had the support of his brother, the Emperor Charles V.

On 10 November 1526, John Zápolya was proclaimed king by a Diet at Székesfehérvár, elected in the parliament by the untitled lesser nobility (gentry).

Nicolaus Olahus, secretary of Louis, attached himself to the party of Ferdinand but retained his position with his sister, Queen Dowager Mary. Ferdinand was also elected King of Hungary, Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, etc. by the higher aristocracy (the magnates or barons) and the Hungarian Catholic clergy in a rump Diet in Pozsony (Bratislava in Slovak) on 17 December 1526.[17] Accordingly, Ferdinand was crowned as King of Hungary in the Székesfehérvár Basilica on 3 November, 1527.

The Croatian nobles unanimously accepted the Pozsony election of Ferdinand I, receiving him as their king in the 1527 election in Cetin, and confirming the succession to him and his heirs.[18] In return for the throne, Archduke Ferdinand promised to respect the historic rights, freedoms, laws and customs of the Croats when they united with the Hungarian kingdom and to defend Croatia from Ottoman invasion.[2]

Brendan Simms notes that the reason Ferdinand was able to gain this sphere of power was Charles V's difficulties in coordinating between the Austrian, Hungarian fronts and his Mediterranean fronts in the face of the Ottoman threat, as well as in his German, Burgundian and Italian theatres of war against German Protestant Princes and France. Thus the defense of central Europe was subcontracted to Ferdinand as well as many responsibilities involving the management of the Empire. Charles V abdicated as archduke of Austriain 1522, and nine years after that he had the German princes elect Ferdinand as King of the Romans, who thus became his designated successor. "This had profound implications for state formation in south-eastern Europe. Ferdinand rescued Bohemia and Silesia from the Hungarian wreckage, making his north-eastern flank more secure. He told the Landtag, the assembled representatives of the nobility, at Linz in 1530 that 'the Turks cannot be resisted unless the Kingdom of Hungary was in the hands of an Archduke of Austria or another German prince'. After some hesitation, Croatia and the Hungarian rump joined the Habsburgs. In both cases, the link was essentially a contractual one, directly linked to Ferdinand’s ability to provide protection against the Turks."[19]

The Austrian lands were in miserable economic and financial conditions, but Ferdinand was forced to introduce the so-called Turkish Tax (Türken Steuer) in view of the Ottoman threat. In spite of the huge Austrian sacrifices, he was not able to collect enough money to pay for the expenses of the defence costs of Austrian lands. His annual revenues only allowed him to hire 5,000 mercenaries for two months, thus Ferdinand asked for help from his brother, Emperor Charles V, and started to borrow money from rich bankers like the Fugger family.[20]

Ferdinand defeated Zápolya at the Battle of Tarcal in September 1527 and again in the Battle of Szina in March 1528. Zápolya fled the country and applied to Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent for support, making Hungary an Ottoman vassal state.

This led to the most dangerous moment of Ferdinand's career, in 1529, when Suleiman took advantage of this Hungarian support for a massive but ultimately unsuccessful assault on Ferdinand's capital: the Siege of Vienna, which sent Ferdinand to refuge in Bohemia. A further Ottoman invasion was repelled in 1532 (see Siege of Güns). In that year Ferdinand made peace with the Ottomans, splitting Hungary into a Habsburg sector in the west and John Zápolya's domain in the east, the latter effectively a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire.

Together with the formation of the Schmalkaldic League in 1531, this struggle with the Ottomans caused Ferdinand to grant the Nuremberg Religious Peace. As long as he hoped for a favorable response from his humiliating overtures to Suleiman, Ferdinand was not inclined to grant the peace which the Protestants demanded at the Diet of Regensburg which met in April 1532. But as the army of Suleiman drew nearer he yielded and on 23 July 1532 the peace was concluded at Nuremberg where the final deliberations took place. Those who had up to this time joined the Reformation obtained religious liberty until the meeting of a council and in a separate compact all proceedings in matters of religion pending before the imperial chamber court were temporarily paused.[21]

In 1538, in the Treaty of Nagyvárad, Ferdinand induced the childless Zápolya to name him as his successor. But in 1540, just before his death, Zápolya had a son, John II Sigismund, who was promptly elected King by the Diet. Ferdinand invaded Hungary, but the regent, Frater George Martinuzzi, Bishop of Várad, called on the Ottomans for protection. Suleiman marched into Hungary (see Siege of Buda (1541)) and not only drove Ferdinand out of central Hungary, he forced Ferdinand to agree to pay tribute for his lands in western Hungary.[22]

John II Sigismund was also supported by King Sigismund I of Poland, his mother's father, but in 1543 Sigismund made a treaty with the Habsburgs and Poland became neutral. Prince Sigismund Augustus married Elisabeth of Austria, Ferdinand's daughter.

Suleiman had allocated Transylvania and eastern Royal Hungary to John II Sigismund, which became the "Eastern Hungarian Kingdom", reigned over by his mother, Isabella Jagiellon, with Martinuzzi as the real power. But Isabella's hostile intrigues and threats from the Ottomans led Martinuzzi to switch round. In 1549, he agreed to support Ferdinand's claim, and Imperial armies marched into Transylvania. In the Treaty of Weissenburg (1551), Isabella agreed on behalf of John II Sigismund to abdicate as King of Hungary and to hand over the royal crown and regalia. Thus Royal Hungary and Transylvania went to Ferdinand, who agreed to recognise John II Sigismund as vassal Prince of Transylvania and betrothed one of his daughters to him. Meanwhile, Martinuzzi attempted to keep the Ottomans happy even after they responded by sending troops. Ferdinand's general Castaldo suspected Martinuzzi of treason and with Ferdinand's approval had him killed.

Since Martinuzzi was by this time an archbishop and Cardinal, this was a shocking act, and Pope Julius III excommunicated Castaldo and Ferdinand. Ferdinand sent the Pope a long accusation of treason against Martinuzzi in 87 articles, supported by 116 witnesses. The Pope exonerated Ferdinand and lifted the excommunications in 1555.[23]

The war in Hungary continued. Ferdinand was unable to keep the Ottomans out of Hungary. In 1554, Ferdinand sent Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq to Constantinople to discuss a border treaty with Suleiman, but he could achieve nothing. In 1556 the Diet returned John II Sigismund to the eastern Hungarian throne, where he remained until 1570. De Busbecq returned to Constantinople in 1556, and succeeded on his second try.

The Austrian branch of Habsburg monarchs needed the economic power of Hungary for the Ottoman wars. During the Ottoman wars the territory of the former Kingdom of Hungary shrunk by around 70%. Despite these enormous territorial and demographic losses, the smaller, heavily war-torn Royal Hungary had remained economically more important to the Habsburg rulers than Austria or Kingdom of Bohemia even at the end of the 16th century.[24] Out of all his countries, the depleted Kingdom of Hungary was, at that time, Ferdinand's largest source of revenue.[25]

Consolidation of power in Bohemia

When he took control of the Bohemian lands in the 1520s, their religious situation was complex. Its German population was composed of Catholics and Lutherans. Some Czechs were receptive to Lutheranism, but most of them adhered to Utraquist Hussitism, while a minority of them adhered to Roman Catholicism. A significant number of Utraquists favoured an alliance with the Protestants.[26] At first, Ferdinand accepted this situation and he gave considerable freedom to the Bohemian estates. In the 1540s, the situation changed. In Germany, while most Protestant princes had hitherto favored negotiation with the Emperor and while many had supported him in his wars, they became increasingly confrontational during this decade. Some of them even went to war against the Empire, and many Bohemian (German or Czech) Protestants or Utraquists sympathized with them.[26]

Ferdinand and his son Maximilian participated in the victorious campaign of Charles V against the German Protestants in 1547. The same year, he also defeated a Protestant revolt in Bohemia, where the estates and a large part of the nobility had denied him support in the German campaign. This allowed him to increase his power in this realm. He centralized his administration, revoked many urban privileges and confiscated properties.[26] Ferdinand also sought to strengthen the position of the Catholic church in the Bohemian lands, and favoured the installation of the Jesuits there.

Ferdinand and the Augsburg Peace of 1555

In the 1550s, Ferdinand managed to win some key victories on the imperial scene. Unlike his brother, he opposed Albrecht of Brandenburg-Kulmbach and participated in his defeat.[27] This defeat, along with his German ways, made Ferdinand more popular than the Emperor among Protestant princes. This allowed him to play a critical role in the settlement of the religious issue in the Empire.

After decades of religious and political unrest in the German states, Charles V ordered a general Diet in Augsburg at which the various states would discuss the religious problem and its solution. Charles himself did not attend, and delegated authority to his brother, Ferdinand, to "act and settle" disputes of territory, religion and local power.[28] At the conference, which opened on 5 February, Ferdinand cajoled, persuaded and threatened the various representatives into agreement on three important principles promulgated on 25 September:

- The principle of cuius regio, eius religio ("Whose realm, his religion") provided for internal religious unity within a state: the religion of the prince became the religion of the state and all its inhabitants. Those inhabitants who could not conform to the prince's religion were allowed to leave, an innovative idea in the sixteenth century. This principle was discussed at length by the various delegates, who finally reached agreement on the specifics of its wording after examining the problem and the proposed solution from every possible angle.

- The second principle, called the reservatum ecclesiasticum (ecclesiastical reservation), covered the special status of the ecclesiastical state. If the prelate of an ecclesiastic state changed his religion, the men and women living in that state did not have to do so. Instead, the prelate was expected to resign from his post, although this was not spelled out in the agreement.

- The third principle, known as Declaratio Ferdinandei (Ferdinand's Declaration), exempted knights and some of the cities from the requirement of religious uniformity, if the reformed religion had been practised there since the mid-1520s, allowing for a few mixed cities and towns where Catholics and Lutherans had lived together. It also protected the authority of the princely families, the knights and some of the cities to determine what religious uniformity meant in their territories. Ferdinand inserted this at the last minute, on his own authority.[29]

Problems with the Augsburg settlement

_MET_DT773.jpg.webp)

After 1555, the Peace of Augsburg became the legitimating legal document governing the co-existence of the Lutheran and Catholic faiths in the German lands of the Holy Roman Empire, and it served to ameliorate many of the tensions between followers of the "Old Faith" (Catholicism) and the followers of Luther, but it had two fundamental flaws. First, Ferdinand had rushed the article on reservatum ecclesiasticum through the debate; it had not undergone the scrutiny and discussion that attended the widespread acceptance and support of cuius regio, eius religio. Consequently, its wording did not cover all, or even most, potential legal scenarios. The Declaratio Ferdinandei was not debated in plenary session at all; using his authority to "act and settle,"[28] Ferdinand had added it at the last minute, responding to lobbying by princely families and knights.[30]

While these specific failings came back to haunt the Empire in subsequent decades, perhaps the greatest weakness of the Peace of Augsburg was its failure to take into account the growing diversity of religious expression emerging in the so-called evangelical and reformed traditions. Other confessions had acquired popular, if not legal, legitimacy in the intervening decades and by 1555, the reforms proposed by Luther were no longer the only possibilities of religious expression: Anabaptists, such as the Frisian Menno Simons (1492–1559) and his followers; the followers of John Calvin, who were particularly strong in the southwest and the northwest; and the followers of Huldrych Zwingli were excluded from considerations and protections under the Peace of Augsburg. According to the Augsburg agreement, their religious beliefs remained heretical.[31]

Charles V's abdication

In 1556, amid great pomp, and leaning on the shoulder of one of his favourites (the 24-year-old William, Count of Nassau and Orange),[32] Charles gave away his lands and his offices. The Spanish Empire, which included Spain, the Netherlands, Naples, Milan and Spain's possessions in the Americas, went to his son, Philip. Ferdinand became suo jure monarch in Austria and succeeded Charles as Holy Roman Emperor.[33] This course of events had been guaranteed already on 5 January 1531 when Ferdinand had been elected the King of the Romans and so the legitimate successor of the reigning Emperor.

Charles's choices were appropriate. Philip was culturally Spanish: he was born in Valladolid and raised in the Spanish court, his native tongue was Spanish, and he preferred to live in Spain. Ferdinand was familiar with, and to, the other princes of the Holy Roman Empire. Although he too had been born in Spain, he had administered his brother's affairs in the Empire since 1531.[31] Some historians maintain Ferdinand had also been touched by the reformed philosophies, and was probably the closest the Holy Roman Empire ever came to a Protestant emperor; he remained nominally a Catholic throughout his life, although reportedly he refused last rites on his deathbed.[34] Other historians maintain he was as Catholic as his brother, but tended to see religion as outside the political sphere.[35]

Charles' abdication had far-reaching consequences in imperial diplomatic relations with France and the Netherlands, particularly in his allotment of the Spanish kingdom to Philip. In France, the kings and their ministers grew increasingly uneasy about Habsburg encirclement and sought allies against Habsburg hegemony from among the border German territories, and even from some of the Protestant kings. In the Netherlands, Philip's ascension in Spain raised particular problems; for the sake of harmony, order, and prosperity Charles had not blocked the Reformation, and had tolerated a high level of local autonomy. An ardent Catholic and rigidly autocratic prince, Philip pursued an aggressive political, economic and religious policy toward the Dutch, resulting in a Dutch rebellion shortly after he became king. Philip's militant response meant the occupation of much of the upper provinces by troops of, or hired by, Habsburg Spain and the constant ebb and flow of Spanish men and provisions on the so-called Spanish road from northern Italy, through the Burgundian lands, to and from Flanders.[36]

Holy Roman Emperor (1556–1564)

Charles abdicated as Emperor in August 1556 in favor of his brother Ferdinand. Given the settlement of 1521 and the election of 1531, Ferdinand became Holy Roman Emperor and suo jure Archduke of Austria. Due to lengthy debate and bureaucratic procedure, the Imperial Diet did not accept the Imperial succession until 3 May 1558. The Pope refused to recognize Ferdinand as Emperor until 1559, when peace was reached between France and the Habsburgs. During his Emperorship, the Council of Trent came to an end. Ferdinand organized an Imperial election in 1562 in order to secure the succession of his son Maximilian II. Venetian ambassadors to Ferdinand recall in their Relazioni the Emperor's pragmatism and his ability to speak multiple languages. Several issues of the Council of Trent were solved after a compromise was personally reached between Emperor Ferdinand and Morone, the papal legate.

In the Empire

An important invention of Ferdinand was the Hofkriegsrat (Aulic War Council), officially established in 1556 to coordinate military affairs in all Habsburg lands (inside and outside the Holy Roman Empire).[37] Together with the Reichshofkanzlei (established in 1559, merging the Imperial and Austrian Chancelleries, thus also dealing with affairs of both Imperial and Habsburg lands) and the Hofkammer (the Finance Chamber, which received imperial taxes from the Reichspfennig meister), it formed the core of the Habsburg government in Vienna. The Reichshofrat (Imperial Aulic Council, one of the two highest imperial courts together with Reichskammergericht; the institution temporarily incorporated the Austrian Hofrat) was revived to deal with affairs concerning imperial prerogatives. In 1556, an ordinance was issued to ensure imperial and dynastic affairs were managed separately (by two groups of officials from the same institution) though.[38][39] In his time, the influence of the Estates in these institutions were limited. For eachLändergroup, regiments (or governments) and treasury offices were created.[40]

Unlike Maximilian I and Charles V, Ferdinand I was not a nomadic ruler. In 1533, he moved his residence to Vienna and spent most of his time there. After experiencing the Turkish siege of 1529, Ferdinand worked hard to make Vienna an impregnable fortress.[41] After his 1558 election, Vienna became the imperial capital.[42]

Administration of Royal Hungary, Bohemia and Croatia

.jpg.webp)

Since 1542, Charles V and Ferdinand had been able to collect the Common Penny tax, or Türkenhilfe (Turkish aid), designed to protect the Empire against the Ottomans or France. But as Hungary, unlike Bohemia, was not part of the Reich, the imperial aid for Hungary depended on political factors. The obligation was only in effect if Vienna or the Empire was threatened.[43][44][45][46]

The western part of Hungary over which Ferdinand had dominion became known as Royal Hungary. As the ruler of Austria, Bohemia and Royal Hungary, Ferdinand adopted a policy of centralisation and, in common with other monarchs of the time, the construction of an absolute monarchy. In 1527, soon after ascending the throne, he published a constitution for his hereditary domains (Hofstaatsordnung) and established Austrian-style institutions in Pressburg for Hungary, in Prague for Bohemia, and in Breslau for Silesia.

Ferdinand was able to introduce more uniform governments for his realms and also strengthen his control over finance in Bohemia, which provided him with half of his revenue. The governments basically remained independent of each other though. An Austrian could make a career in Bohemian administration but usually only after naturalization, except for some royal protégés such as Florian Griespeck, while it was virtually unheard of (in contrast with the future) for a Bohemian to gain advancement in the Austrian government.[47] An elected king himself, he gradually nudged the monarchy towards becoming hereditary, which would finally succeed under Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor.[48]

_as_King_of_Hungary_and_Bohemia.svg.png.webp)

In 1547 the Bohemian Estates rebelled against Ferdinand after he had ordered the Bohemian army to move against the German Protestants. After suppressing the revolt, he retaliated by limiting the privileges of Bohemian cities and inserting a new bureaucracy of royal officials to control urban authorities. Ferdinand was a supporter of the Counter-Reformation and helped lead the Catholic response against what he saw as the heretical tide of Protestantism. For example, in 1551 he invited the Jesuits to Vienna and in 1556 to Prague. Finally, in 1561 Ferdinand revived the Archdiocese of Prague, which had been previously liquidated due to the success of the Protestants.

After the Ottoman invasion of Hungary the traditional Hungarian coronation city Székesfehérvár came under Turkish occupation. Thus, in 1536 the Hungarian Diet decided that a new place for coronation of the king as well as a meeting place for the Diet itself would be set in Pressburg. Ferdinand proposed that the Hungarian and Bohemian diets should convene and hold debates together with the Austrian estates, but all parties refused such an innovation.

In Hungary, the monarchy remained elective until 1627 (with Habsburgs' female inheritance rights being acknowledged in 1723), although the kings that followed Ferdinand would almost always be Habsburgs.[49]

A rudimentary union between Austria, Hungary and Bohemia was formed though, on the basis of common legal status. Ferdinand had an interest in keeping Bohemia separate from imperial jurisdiction and making the connection between Bohemia and the Empire looser (Bohemia did not have to pay taxes to the Empire). As he refused the rights of an Imperial Elector as King of Bohemia, he was able to give Bohemia (as well as associated territories such as Upper and Lower Alsatia, Silesia and Moravia) the same privileged status as Austria, therefore affirming his superior position in the Empire.[50][51]

Death and succession

In December 1562, Ferdinand had Maximilian, his eldest son elected King of the Romans. This was followed with succession in Bohemia, and in 1563, the crown of Hungary.[52]

Ferdinand died in Vienna in 1564 and is buried in St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague. After his death, Maximilian ascended unchallenged.[53]

Legacy

Ferdinand's legacy ultimately proved enduring. Though lacking resources, he managed to defend his land against the Ottomans with limited support from his brother, and even secured a part of Hungary that would later provide the basis for the conquest of the whole kingdom by the Habsburgs. In his own possessions, he built a tax system that, though imperfect, would continue to be used by his successors.[54] His handling of the Protestant Reformation proved more flexible and more effective than that of his brother and he played a key part in the settlement of 1555, which started an era of peace in Germany. His statesmanship, overall, was cautious and effective. On the other hand, when he engaged in more audacious endeavours, like his offensives against Buda and Pest, it often ended in failure.

Fichtner remarks that Ferdinand was a mediocre military commander (thus the many difficulties in dealing with the Ottomans in Hungary) but an energetic and very imaginative administrator, who produced a framework for his empire that would endured into the eighteenth century. The core included a court council, privy council, central treasury and a body for military affairs, with the written business conducted by a common chancery. In his time and in practice, Bohemia and Hungary resisted cooperating with the structure but the German territories widely imitated it.[55]

Ferdinand was also a patron of the arts. He embellished Vienna and Prague. The University of Vienna was reorganized. He also called Jesuits to the capital city, attracted architects and scholars from Italy and the Low Countries to create an intellectual milieu surrounding the court. He promoted scholarly interest in Oriental languages.[56] The humanists he invited had a major influence on his son Maximilian. He was particularly fond of music and hunting. While not a supremely gifted commander, he was interested in military matters and participated in several campaigns during his reign.

He was the last German king crowned in Aachen.[57]

Name in other languages

German, Czech, Slovenian, Slovak, Serbian, Croatian: Ferdinand I.; Hungarian: I. Ferdinánd; Spanish: Fernando I; Turkish: 1. Ferdinand; Polish: Ferdynand I.

Marriage and children

On 26 May 1521 in Linz, Austria, Ferdinand married Anna of Bohemia and Hungary (1503–1547), daughter of Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary and his wife Anne of Foix-Candale.[15] They had fifteen children, all but two of whom reached adulthood:

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elizabeth | 9 July 1526 | 15 June 1545 | Married to the future King Sigismund II Augustus of Poland. |

| Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor | 31 July 1527 | 12 October 1576 | Married to his first cousin Maria of Spain and had issue.[58] |

| Anna | 7 July 1528 | 16/17 October 1590 | Married to Albert V, Duke of Bavaria.[58] |

| Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria[58] | 14 June 1529 | 24 January 1595 | Married to Philippine Welser and then to his niece (daughter of Eleanor) Anne Juliana Gonzaga. |

| Maria | 15 May 1531 | 11 December 1581 | Married to Wilhelm, Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg.[58] |

| Magdalena | 14 August 1532 | 10 September 1590 | A nun. |

| Catherine | 15 September 1533 | 28 February 1572 | Married to Duke Francesco III of Mantua[59] and then to King Sigismund II Augustus of Poland[60] |

| Eleanor | 2 November 1534 | 5 August 1594 | Married to William I, Duke of Mantua. |

| Margaret | 16 February 1536 | 12 March 1567 | A nun. |

| John | 10 April 1538 | 20 March 1539 | Died in childhood. |

| Barbara | 30 April 1539 | 19 September 1572 | Married to Alfonso II, Duke of Ferrara and Modena. |

| Charles II, Archduke of Austria[58] | 3 June 1540 | 10 July 1590 | Father of Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor. |

| Ursula | 24 July 1541 | 30 April 1543 | Died in childhood |

| Helena | 7 January 1543 | 5 March 1574 | A nun. |

| Joanna | 24 January 1547 | 10 April 1578 | Married to Francesco I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany.[58] |

Heraldry

| Heraldry of Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coinage

Ferdinand I has been the main motif for many collector coins and medals. The most recent one is the Austrian silver 20-euro Renaissance coin issued on 12 June 2002. A portrait of Ferdinand I is shown on the reverse of the coin, while on the obverse a view of the Swiss Gate of the Hofburg Palace can be seen.

See also

- Parade armor of Ferdinand I

- Kings of Germany family tree

- First Congress of Vienna in 1515

- Battle of Mohács in 1526

- Louis II of Hungary

- John Zápolya, disputed king of Hungary 1526–40

- Ivan Karlović, Banus of Croatia 1521–24 and 1527–31

- Petar Keglević, Banus of Croatia 1537–42

- Pavle Bakic, last Despot of Serbia to be recognised by Ferdinand I and Holy Roman Empire in 1537

- Jovan Nenad, self-proclaimed Emperor of Vojvodina

- Balthasar Hubmaier, Anabaptist theologian, executed by burning

Notes

- Hungary & Croatia contested by John I (1526–40) and John II Sigismund (1540–51, 1556–64)

- In the name of Emperor Charles V until 1556

References

- "Ferdinand I | Holy Roman emperor". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- Milan Kruhek: Cetin, grad izbornog sabora Kraljevine Hrvatske 1527, Karlovačka Županija, 1997, Karslovac

- Pánek, Jaroslav; Tůma, Oldřich (15 April 2019). A History of the Czech Lands. Charles University in Prague, Karolinum Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-80-246-2227-9. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- Fichtner, Paula Sutter (7 March 2017). The Habsburg Monarchy, 1490-1848: Attributes of Empire. Macmillan International Higher Education. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-137-10642-1. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- Berenger, Jean; Simpson, C. A. (22 July 2014). A History of the Habsburg Empire 1273-1700. Routledge. p. 263. ISBN 978-1-317-89569-5. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- Fichtner 2017, pp. 18, 19.

- Evans, R. J. W. (3 August 2006). Austria, Hungary, and the Habsburgs: Central Europe C.1683-1867. OUP Oxford. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-19-928144-2. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- Fichtner 2017, pp. 19.

- Thomas, Alfred (2007). A Blessed Shore: England and Bohemia from Chaucer to Shakespeare. Cornell University Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-8014-4568-2. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- Fichtner, Paula S. (1982). Ferdinand I of Austria: The Politics of Dynasticism in the Age of the Reformation. East European Monographs. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-914710-95-0. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- Ingrao, Charles W. (1994). State and Society in Early Modern Austria. Purdue University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-55753-047-9. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- Stone, Jon R. (2005). The Routledge Dictionary of Latin Quotations: The Illiterati's Guide to Latin Maxims, Mottoes, Proverbs and Sayings (in Latin). Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0415969093.

- Ferdinand I, Holy Roman emperor. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001.

- "Rapport établi par M. Alet Valero" (PDF). Centre National de Documentation Pédagogique. 2006. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- Rasmussen 2018, p. 65.

- Martyn Rady (2014). The Emperor Charles V. Routledge. p. 47. ISBN 978-1317880820.

- Robert A. Kann (1980). A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526–1918. University of California Press. p. 611. ISBN 978-0520042063.

- R. W. Seton-Watson. The southern Slav question and the Habsburg Monarchy. p. 18.

- Simms, Brendan (30 April 2013). Europe: The Struggle for Supremacy, from 1453 to the Present. Basic Books. p. 1737. ISBN 978-0-465-06595-0. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- Jean Berenger; C.A. Simpson (2014). A History of the Habsburg Empire 1273–1700. Routledge. p. 160. ISBN 978-1317895701.

- article on the Nuremberg Religious Peace, p. 351 of the 1899 Lutheran Cyclopedia

- Imber, Colin (2002). The Ottoman Empire, 1300–1650: The Structure of Power. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 53. ISBN 978-0333613863.

- George Martinuzzi entry in the Catholic Encyclopedia

- Robert Evans, Peter Wilson (2012). The Holy Roman Empire, 1495–1806: A European Perspective Volume 1 van Brill's Companions to European History. Brill. p. 263. ISBN 978-9004206830.

- Dr. István Kenyeres: The Financial Administrative Reforms and Revenues of Ferdinand I in Hungary, English summary at p- 92 Link1: Link2:

- Between Lipany and White Mountain, Palmitessa

- Germany and the Holy Roman Empire, Whaley

- Holborn, p. 241.

- For a general discussion of the impact of the Reformation on the Holy Roman Empire, see Holborn, chapters 6–9 (pp. 123–248).

- Holborn, pp. 244–245.

- Holborn, pp. 243–246.

- Lisa Jardine, The Awful End of William the Silent: The First Assassination of a Head of State with A Handgun, London, HarperCollins, 2005, ISBN 0007192576, Chapter 1; Richard Bruce Wernham, The New Cambridge Modern History: The Counter Reformation and Price Revolution 1559–1610, (vol. 3), 1979, pp. 338–345.

- Holborn, pp. 249–250; Wernham, pp. 338–345.

- See Parker Emperor: A new life of Charles V, 2019, pp. 20–50.

- Holborn, pp. 250–251.

- Parker, p. 35.

- Mugnai, Bruno; Flaherty, Chris (26 November 2016). Der lange Türkenkrieg, the long turkish war (1593 - 1606), vol. 2. Soldiershop Publishing. p. 36. ISBN 978-88-9327-162-2. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- Munck, Bert De; Romano, Antonella (20 August 2019). Knowledge and the Early Modern City: A History of Entanglements. Routledge. p. 361. ISBN 978-0-429-80843-2. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- Wilson, Peter H. (28 January 2016). The Holy Roman Empire: A Thousand Years of Europe's History. Penguin Books Limited. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-14-195691-6. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- Cassese, Sabino; Bogdandy, Armin von; Huber, Peter (25 July 2017). The Max Planck Handbooks in European Public Law: Volume I: The Administrative State. Oxford University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-19-103982-9. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- Duindam, Jeroen; Duindam, Jeroen Frans Jozef; Duindam, Professor Jeroen; Roper, Lecturer in History Royal Holloway and Bedford New College Lyndal (14 August 2003). Vienna and Versailles: The Courts of Europe's Dynastic Rivals, 1550-1780. Cambridge University Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-521-82262-6. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- Ágoston, Gábor (22 June 2021). The Last Muslim Conquest: The Ottoman Empire and Its Wars in Europe. Princeton University Press. p. 312. ISBN 978-0-691-20538-0. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- Zmora, Hillay (4 January 2002). Monarchy, Aristocracy and State in Europe 1300-1800. Routledge. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-134-74798-6. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- Ninness, Richard J. (1 December 2020). German Imperial Knights: Noble Misfits between Princely Authority and the Crown, 1479–1648. Routledge. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-000-28502-4. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- Tracy, James D. (29 July 2016). Balkan Wars: Habsburg Croatia, Ottoman Bosnia, and Venetian Dalmatia, 1499–1617. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-4422-1360-9. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- Ágoston, Gábor (22 June 2021). The Last Muslim Conquest: The Ottoman Empire and Its Wars in Europe. Princeton University Press. p. 312. ISBN 978-0-691-20538-0. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- Evans 2006, p. 82.

- Fichtner, Paula Sutter (11 June 2009). Historical Dictionary of Austria. Scarecrow Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-8108-6310-1. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- Szente, Zoltán (20 June 2021). Constitutional Law in Hungary. Kluwer Law International B.V. p. 20. ISBN 978-94-035-3304-9. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- Whaley, Joachim (24 November 2011). Germany and the Holy Roman Empire: Volume I: Maximilian I to the Peace of Westphalia, 1493-1648. OUP Oxford. p. 370. ISBN 978-0-19-154752-2. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- Evans, Robert; Wilson, Peter (25 July 2012). The Holy Roman Empire, 1495-1806: A European Perspective. BRILL. p. 126. ISBN 978-90-04-20683-0. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- Potter, Philip J. (10 January 2014). Monarchs of the Renaissance: The Lives and Reigns of 42 European Kings and Queens. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9103-2. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- Potter 2014, p. 340.

- History of the Habsburg empire, Jean Bérenger

- Fichtner 2009, p. 98.

- Munck & Romano 2019, p. 361.

- Pavlac, Brian A.; Lott, Elizabeth S. (1 June 2019). The Holy Roman Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-4408-4856-8. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- Ward, Prothero & Leathes 1934, p. table 32.

- Hickson 2016, p. 101.

- Davies 1982, p. 137.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Holland, Arthur William (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Urban, William (2003). Tannenberg and After. Chicago: Lithuanian Research and Studies Center. p. 191. ISBN 0-929700-25-2.

- Wurzbach, Constantin, von, ed. (1861). . Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich [Biographical Encyclopedia of the Austrian Empire] (in German). Vol. 7. p. 112 – via Wikisource.

- Stephens, Henry Morse (1903). The story of Portugal. G.P. Putnam's Sons. p. 139. ISBN 9780722224731. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- Poupardin, René (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Kiening, Christian (1994). "Rhétorique de la perte. L'exemple de la mort d'Isabelle de Bourbon (1465)". Médiévales (in French). 13 (27): 15–24. doi:10.3406/medi.1994.1307.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Ortega Gato, Esteban (1999). "Los Enríquez, Almirantes de Castilla" (PDF). Publicaciones de la Institución "Tello Téllez de Meneses" (in Spanish). 70: 42. ISSN 0210-7317.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Downey, Kirstin (November 2015). Isabella: The Warrior Queen. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 28. ISBN 9780307742162. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

Sources

- Davies, Norman (1982). God's Playground: A History of Poland. Columbia University Press.

- Hickson, Sally Anne (2016). Women, Art and Architectural Patronage in Renaissance Mantua: Matrons, Mystics, and Monasteries. Routledge.

- Rasmussen, Mikael Bogh (2018). "Vienna, a Habsburg capital redocorated in classical style: the entry of Maximilian II as King of the Romans in 1563". In Mulryne, J.R.; De Jonge, Krista; Martens, Pieter; Morris, R.L.M. (eds.). Architectures of Festival in Early Modern Europe: Fashioning and Re-fashioning Urban and Courtly Space. Routledge.

- Ward, A.W.; Prothero, G.W.; Leathes, Stanley, eds. (1934). The Cambridge Modern History. Vol. XIII. Cambridge at the University Press.

Further reading

External links

- Literature by and about Ferdinand I. in the German National Library catalogue

- Works by and about Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor in the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek (German Digital Library)

- Biography of the website of the Residenzen-Kommission

- Entry about Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor in the database Gedächtnis des Landes on the history of the state of Lower Austria (Lower Austria Museum)

.svg.png.webp)