Santa Fe, New Mexico

Santa Fe (/ˌsæntə ˈfeɪ, ˈsæntə feɪ/ SAN-tə FAY, - fay; Spanish: [santaˈfe], Spanish for 'Holy Faith'; Tewa: Oghá P'o'oge; Northern Tiwa: Hulp'ó'ona; Navajo: Yootó) is the capital of the U.S. state of New Mexico. The name “Santa Fe” means 'Holy Faith' in Spanish, and the city's full name as founded remains La Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asís ('The Royal Town of the Holy Faith of Saint Francis of Assisi').[4][5]

Santa Fe

Ogha P'o'ogeh | |

|---|---|

State capital | |

| La Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asís, New Mexico | |

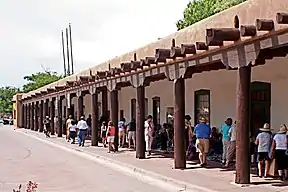

Santa Fe's downtown area | |

Coat of arms | |

| Etymology: Founded as Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asís (Spanish) | |

| Nickname: The City Different | |

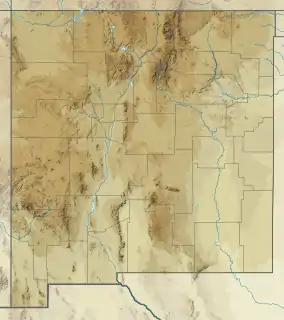

Location in Santa Fe County, New Mexico | |

Santa Fe Location within New Mexico  Santa Fe Location within the United States | |

| Coordinates: 35°40′2″N 105°57′52″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New Mexico |

| County | Santa Fe |

| Founded | 1610 |

| Founded by | Pedro de Peralta |

| Named for | St. Francis of Assisi |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Alan Webber (D) |

| • City Council | Councilors |

| Area | |

| • City | 52.34 sq mi (135.57 km2) |

| • Land | 52.23 sq mi (135.28 km2) |

| • Water | 0.11 sq mi (0.29 km2) |

| Elevation | 7,199[2] ft (2,194 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 87,505 |

| • Density | 1,675.28/sq mi (646.83/km2) |

| • Metro | 154,823 (Santa Fe MSA) 1,162,523 (Albuquerque-Santa Fe-Las Vegas CSA) |

| Demonym(s) | Santa Fean; Santafesino, -na |

| Time zone | UTC−7 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−6 (MDT) |

| ZIP codes | 87500-87599 |

| Area code | 505 |

| FIPS code | 35-70500 |

| GNIS feature ID | 936823 |

| Primary airport | Albuquerque International Sunport ABQ (Major/International) |

| Secondary airport | Santa Fe Regional Airport- KSAF (Public) |

| Website | santafenm |

With a population of 87,505 at the 2020 census, it is the fourth-largest city in New Mexico.[6] It is also the county seat of Santa Fe County. Its metropolitan area is part of the Albuquerque–Santa Fe–Las Vegas combined statistical area, which had a population of 1,162,523 in 2020. The city was founded in 1610 as the capital of Nuevo México, replacing the previous capital, San Juan de los Caballeros (near modern Española) at San Gabriel de Yungue-Ouinge,[7] which makes it the oldest state capital in the United States. It is also at the highest altitude of any of the U.S. state capitals, with an elevation of 7,199 feet (2,194 m).[8]

Santa Fe is widely considered one of the world's great art cities,[9][10] due to its many art galleries and installations, and it is recognized by UNESCO's Creative Cities Network. Its cultural highlights include Santa Fe Plaza, the Palace of the Governors, the Fiesta de Santa Fe, numerous restaurants featuring distinctive New Mexican cuisine, and performances of New Mexico music. Among its many art galleries and installations are the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, a gallery by cartoonist Chuck Jones, and newer art collectives such as Meow Wolf. The cityscape is known for its adobe Pueblo Revival and Territorial Revival architecture.[11]

The area around Santa Fe was occupied for thousands of years by indigenous people who built villages several hundred years ago on the current site of the city. It was known by the Tewa inhabitants as Ogha Po'oge ('white shell water place').[12]

Etymology

Before European colonization of the Americas, the area Santa Fe occupied between 900 CE and the 1500s was known to the Tewa peoples as Oghá P'o'oge ('white shell water place') and by the Navajo people as Yootó ('bead' + 'water place').[13][14] In 1610, Juan de Oñate established the area as Santa Fe de Nuevo México, a province of New Spain.[14] Formal Spanish settlements were developed leading the colonial governor Pedro de Peralta to rename the area La Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asís ('the Royal Town of the Holy Faith of Saint Francis of Assisi').[14] The Spanish phrase Santa Fe is translated as 'holy faith' in English. Although more commonly known as Santa Fe, the city's full, legal name remains to this day as La Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asís.[14] The full name of the city is in both the seal and the flag of the city, although, as pointed out by Associated Press in 2020, Assisi in Spanish is misspelled, reading Aśis instead of Asís.[15]

The standard Spanish pronunciation of the city's name is SAHN-tah-FEH, as contextualized within the city's full Spanish name La Villa Real de la Santa Fé de San Francisco de Asís.[16][17] However, due to the large amounts of tourism and immigration into Santa Fe, an English pronunciation of SAN-tuh-FAY is also commonly used.[16]

History

Spanish Empire 1610–1821

Mexico 1821–1846

United States 1846–present

Spain and Mexico

The area of Santa Fe was originally occupied by indigenous Tanoan peoples, who lived in numerous Pueblo villages along the Rio Grande. One of the earliest known settlements in what today is downtown Santa Fe came sometime after 900 CE. A group of native Tewa built a cluster of homes that centered around the site of today's Plaza and spread for half a mile to the south and west; the village was called Oghá P'o'oge in Tewa.[18] The Tanoans and other Pueblo peoples settled along the Santa Fe River for its water and transportation.

The river had a year-round flow until the 1700s. By the 20th century the Santa Fe River was a seasonal waterway.[19] As of 2007, the river was recognized as the most endangered river in the United States, according to the conservation group American Rivers.[20]

Don Juan de Oñate led the first Spanish effort to colonize the region in 1598, establishing Santa Fe de Nuevo México as a province of New Spain. Under Juan de Oñate and his son, the capital of the province was the settlement of San Juan de los Caballeros north of Santa Fe near modern Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo. Juan de Oñate was banished and exiled from New Mexico by the Spanish, after his rule was deemed cruel towards the indigenous population. New Mexico's second Spanish governor, Don Pedro de Peralta, however, founded a new city at the foot of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in 1607, which he called La Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asís, the Royal Town of the Holy Faith of Saint Francis of Assisi. In 1610, he designated it as the capital of the province, which it has almost constantly remained,[21] making it the oldest state capital in the United States.

Lack of Native American representation within the province of Santa Fe de Nuevo México, New Spain (current New Mexico's early government) led to the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, when groups of different Native Pueblo peoples were successful in driving the Spaniards out of New Mexico to El Paso, the Pueblo continued running New Mexico proper from the Palace of the Governors in Santa Fe from 1680 to 1692. The territory was reconquered in 1692 by Don Diego de Vargas through the war campaign called the "Bloodless Reconquest" which was criticized as violent even at the time, it was actually the following governor Francisco Cuervo y Valdez that truly started to broker peace, such as the founding of Albuquerque, to guarantee better representation and trade access for Pueblos in New Mexico's government. Other governors of New Mexico, such as Tomás Vélez Cachupin, continued to be better known for their more forward thinking work with the indigenous population of New Mexico. Santa Fe was Spain's provincial seat at outbreak of the Mexican War of Independence in 1810. It was considered important to fur traders based in present-day Saint Louis, Missouri. When the area was still under Spanish rule, the Chouteau brothers of Saint Louis gained a monopoly on the fur trade, before the United States acquired Missouri under the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. The fur trade contributed to the wealth of Saint Louis. The city's status as the capital of the Mexican territory of Santa Fe de Nuevo México was formalized in the 1824 Constitution after Mexico achieved independence from Spain.

When the Republic of Texas seceded from Mexico in 1836, it attempted to claim Santa Fe and other parts of Nuevo México as part of the western portion of Texas along the Río Grande. In 1841, a small military and trading expedition set out from Austin, intending to take control of the Santa Fe Trail. Known as the Texan Santa Fe Expedition, the force was poorly prepared and was easily captured by the New Mexican military.

United States

In 1846, the United States declared war on Mexico. Brigadier General Stephen W. Kearny led the main body of his Army of the West of some 1,700 soldiers into Santa Fe to claim it and the whole New Mexico Territory for the United States. By 1848 the U.S. officially gained New Mexico through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

Colonel Alexander William Doniphan, under the command of Kearny, recovered ammunition from Santa Fe labeled "Spain 1776" showing both the lack of communications and quality of military support New Mexico received under Mexican rule.[22]

After its annexation, Texas claimed Santa Fe along with other territory in eastern New Mexico. Texas Governor Peter H. Bell sent a letter to President Zachary Taylor, who died before he could read it, demanding that the U.S. Army stop defending New Mexico. In response, Taylor's successor Millard Fillmore stationed additional troops to the area to halt any incursion by the Texas Militia.[23] The territorial dispute was finally resolved by the Compromise of 1850, which designated the 103rd meridian west as Texas's western border.

Some American visitors at first saw little promise in the remote town. One traveller in 1849 wrote:

I can hardly imagine how Santa Fe is supported. The country around it is barren. At the North stands a snow-capped mountain while the valley in which the town is situated is drab and sandy. The streets are narrow ... A Mexican will walk about town all day to sell a bundle of grass worth about a dime. They are the poorest looking people I ever saw. They subsist principally on mutton, onions and red pepper.[24]

In 1851, Jean Baptiste Lamy arrived, becoming bishop of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Colorado in 1853. During his leadership, he traveled to France, Rome, Tucson, Los Angeles, St. Louis, New Orleans, and Mexico City. He built the Santa Fe Saint Francis Cathedral and shaped Catholicism in the region until his death in 1888.[25]

As part of the New Mexico Campaign of the Civil War, General Henry Sibley occupied the city, flying the Confederate flag over Santa Fe for a few days in March 1862. Sibley was forced to withdraw after Union troops destroyed his logistical trains following the Battle of Glorieta Pass. The Santa Fe National Cemetery was created by the federal government after the war in 1870 to inter the Union soldiers who died fighting there.

.png.webp)

On October 21, 1887, Anton Docher, "The Padre of Isleta", went to New Mexico where he was ordained as a priest in the St Francis Cathedral of Santa Fe by Bishop Jean-Baptiste Salpointe. After a few years serving in Santa Fe,[26] Bernalillo and Taos,[27] he moved to Isleta on December 28, 1891. He wrote an ethnological article published in The Santa Fé Magazine in June 1913, in which he describes early 20th century life in the Pueblos.[28]

As railroads were extended into the West, Santa Fe was originally envisioned as an important stop on the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. But as the tracks were constructed into New Mexico, the civil engineers decided that it was more practical to go through Lamy, a town in Santa Fe County to the south of Santa Fe. A branch line was completed from Lamy to Santa Fe in 1880.[29] The Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad extended the narrow gauge Chili Line from the nearby city of Española to Santa Fe in 1886.[30]

.jpg.webp)

Neither was sufficient to offset the negative effects of Santa Fe's having been bypassed by the main railroad route. It suffered gradual economic decline into the early 20th century. Activists created a number of resources for the arts and archaeology, notably the School of American Research, created in 1907 under the leadership of the prominent archaeologist Edgar Lee Hewett. In the early 20th century, Santa Fe became a base for numerous writers and artists. The first airplane to fly over Santa Fe was piloted by Rose Dugan, carrying Vera von Blumenthal as passenger. Together the two women started the development of the Pueblo Indian pottery industry, helping native women to market their wares. They contributed to the founding of the annual Santa Fe Indian Market.

In 1912, New Mexico was admitted as the United States of America's 47th state, with Santa Fe as its capital.

1912 plan

In 1912, when the town's population was approximately 5,000 people, the city's civic leaders designed and enacted a sophisticated city plan that incorporated elements of the contemporary City Beautiful movement, city planning, and historic preservation. The latter was particularly influenced by similar movements in Germany. The plan anticipated limited future growth, considered the scarcity of water, and recognized the future prospects of suburban development on the outskirts. The planners foresaw that its development must be in harmony with the city's character.[31]

Artists and tourists

After the mainline of the railroad bypassed Santa Fe, it lost population. However, artists and writers, as well as retirees, were attracted to the cultural richness of the area, the beauty of the landscapes, and its dry climate. Local leaders began promoting the city as a tourist attraction. The city sponsored architectural restoration projects and erected new buildings according to traditional techniques and styles, thus creating the Santa Fe Style.

Edgar L. Hewett, founder and first director of the School of American Research and the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe, was a leading promoter. He began the Santa Fe Fiesta in 1919 and the Southwest Indian Fair in 1922 (now known as the Indian Market). When Hewett tried to attract a summer program for Texas women, many artists rebelled, saying the city should not promote artificial tourism at the expense of its artistic culture. The writers and artists formed the Old Santa Fe Association and defeated the plan.[32]

Japanese-American internment camp

New Mexico voted against interring any of its citizens of Japanese heritage, so none of the Japanese New Mexicans were interred during World War II.[33] During World War II, the federal government ordered a Japanese-American internment camp to be established. Beginning in June 1942, the Department of Justice arrested 826 Japanese-American men after the attack on Pearl Harbor; they held them near Santa Fe, in a former Civilian Conservation Corps site that had been acquired and expanded for the purpose. Although there was a lack of evidence and no due process, the men were held on suspicion of fifth column activity. Security at Santa Fe was similar to a military prison, with twelve-foot barbed wire fences, guard towers equipped with searchlights, and guards carrying rifles, side arms and tear gas.[34] By September, the internees had been transferred to other facilities—523 to War Relocation Authority concentration camps in the interior of the West, and 302 to Army internment camps.

The Santa Fe site was used next to hold German and Italian nationals, who were considered enemy aliens after the outbreak of war.[35] In February 1943, these civilian detainees were transferred to Department of Justice custody.

The camp was expanded at that time to take in 2,100 men segregated from the general population of Japanese-American inmates. These were mostly Nisei and Kibei who renounced their U.S. citizenship rather than sign an oath to "give up loyalty to the Japanese emperor" (offending them, since they had no identification with the emperor & were being asked to enlist in fighting him while their Japanese-born parents were interned) and other "troublemakers" from the Tule Lake Segregation Center.[34] In 1945, four internees were seriously injured when violence broke out between the internees and guards in an event known as the Santa Fe Riot. The camp remained open past the end of the war; the last detainees were released in mid 1946. The facility was closed and sold as surplus soon after.[35] The camp was located in what is now the Casa Solana neighborhood.[36]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 37.4 sq mi (96.9 km2), of which 37.3 sq mi (96.7 km2) are land and 0.077 sq mi (0.2 km2) (0.21%) is covered by water.

Santa Fe is located at 7,199 feet (2,194 m) above sea level, making it the highest state capital in the United States.[2]

The Santa Fe River and the arroyos of Santa Fe drain the region to the Rio Grande.

Climate

Santa Fe's climate is characterized by cool, dry winters, hot summers, and relatively low precipitation. According to the Köppen climate classification, depending on which variant of the system is used, the city has either a subtropical highland climate (Cwb) or a warm-summer humid continental climate (Dfb), somewhat unusual at 35°N. With low precipitation, though, it is more similar to the climates of Turkey that fall into this category.[37][38] The 24-hour average temperature in the city ranges from 30.3 °F (−0.9 °C) in December to 70.1 °F (21.2 °C) in July. Due to the relative aridity and elevation, average diurnal temperature variation exceeds 25 °F (14 °C) in every month, and 30 °F (17 °C) much of the year. The city usually receives six to eight snowfalls a year between November and April. The heaviest rainfall occurs in July and August, with the arrival of the North American Monsoon.

| Climate data for Santa Fe, New Mexico (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1972–present), elevation 7,198 ft (2,194 m) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 65 (18) |

73 (23) |

77 (25) |

84 (29) |

96 (36) |

99 (37) |

99 (37) |

96 (36) |

94 (34) |

87 (31) |

75 (24) |

65 (18) |

99 (37) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 56.3 (13.5) |

61.5 (16.4) |

70.9 (21.6) |

77.7 (25.4) |

86.1 (30.1) |

94.6 (34.8) |

94.8 (34.9) |

91.7 (33.2) |

87.4 (30.8) |

79.7 (26.5) |

67.3 (19.6) |

56.3 (13.5) |

96.1 (35.6) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 43.0 (6.1) |

48.0 (8.9) |

56.6 (13.7) |

64.3 (17.9) |

73.7 (23.2) |

84.1 (28.9) |

85.8 (29.9) |

83.4 (28.6) |

77.5 (25.3) |

66.3 (19.1) |

53.0 (11.7) |

42.6 (5.9) |

64.9 (18.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 30.4 (−0.9) |

34.7 (1.5) |

41.5 (5.3) |

48.3 (9.1) |

57.3 (14.1) |

67.1 (19.5) |

70.5 (21.4) |

68.6 (20.3) |

62.1 (16.7) |

50.8 (10.4) |

38.7 (3.7) |

30.1 (−1.1) |

50.0 (10.0) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 17.9 (−7.8) |

21.3 (−5.9) |

26.4 (−3.1) |

32.4 (0.2) |

40.8 (4.9) |

50.1 (10.1) |

55.1 (12.8) |

53.7 (12.1) |

46.8 (8.2) |

35.4 (1.9) |

24.4 (−4.2) |

17.6 (−8.0) |

35.2 (1.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 1.9 (−16.7) |

5.7 (−14.6) |

10.7 (−11.8) |

19.1 (−7.2) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

37.8 (3.2) |

46.6 (8.1) |

45.3 (7.4) |

34.3 (1.3) |

20.3 (−6.5) |

8.3 (−13.2) |

−0.1 (−17.8) |

−4.1 (−20.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −14 (−26) |

−24 (−31) |

−6 (−21) |

10 (−12) |

19 (−7) |

28 (−2) |

37 (3) |

36 (2) |

26 (−3) |

5 (−15) |

−12 (−24) |

−17 (−27) |

−24 (−31) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.55 (14) |

0.49 (12) |

0.74 (19) |

0.60 (15) |

0.89 (23) |

0.87 (22) |

2.26 (57) |

2.04 (52) |

1.39 (35) |

1.34 (34) |

0.79 (20) |

0.83 (21) |

12.79 (325) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 3.7 (9.4) |

2.4 (6.1) |

3.9 (9.9) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1.3 (3.3) |

1.7 (4.3) |

6.8 (17) |

20.2 (51) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 3.4 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 9.9 | 10.1 | 6.1 | 4.8 | 3.7 | 4.3 | 63.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 7.5 |

| Source: NOAA[39][40] | |||||||||||||

Spanish and Pueblo influences

The Spanish laid out the city according to the "Laws of the Indies", town planning rules and ordinances which had been established in 1573 by King Philip II. The fundamental principle was that the town be laid out around a central plaza. On its north side was the Palace of the Governors, while on the east was the church that later became the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi.

An important style implemented in planning the city was the radiating grid of streets centered on the central Plaza. Many were narrow and included small alley-ways, but each gradually merged into the more casual byways of the agricultural perimeter areas. As the city grew throughout the 19th century, the building styles evolved too, so that by statehood in 1912, the eclectic nature of the buildings caused it to look like "Anywhere USA".[41] The city government realized that the economic decline, which had started more than twenty years before with the railway moving west and the federal government closing down Fort Marcy, might be reversed by the promotion of tourism.

To achieve that goal, the city created the idea of imposing a unified building style – the Spanish Pueblo Revival look, which was based on work done restoring the Palace of the Governors. The sources for this style came from the many defining features of local architecture: vigas (rough, exposed beams that extrude through supporting walls, and are thus visible outside as well as inside the building) and canales (rain spouts cut into short parapet walls around flat roofs), features borrowed from many old adobe homes and churches built many years before and found in the Pueblos, along with the earth-toned look (reproduced in stucco) of the old adobe exteriors.

After 1912 this style became official: all buildings were to be built using these elements. By 1930 there was a broadening to include the "Territorial", a style of the pre-statehood period which included the addition of portales (large, covered porches) and white-painted window and door pediments (and also sometimes terra cotta tiles on sloped roofs, but with flat roofs still dominating). The city had become "different". However, "in the rush to pueblofy"[42] Santa Fe, the city lost a great deal of its architectural history and eclecticism. Among the architects most closely associated with this new style are T. Charles Gaastra and John Gaw Meem.

By an ordinance passed in 1957, new and rebuilt buildings, especially those in designated historic districts, must exhibit a Spanish Territorial or Pueblo style of architecture, with flat roofs and other features suggestive of the area's traditional adobe construction. However, many contemporary houses in the city are built from lumber, concrete blocks, and other common building materials, but with stucco surfaces (sometimes referred to as "faux-dobe", pronounced as one word: "foe-dough-bee") reflecting the historic style.

In a September 2003 report by Angelou Economics, it was determined that Santa Fe should focus its economic development efforts in the following seven industries: Arts and Culture, Design, Hospitality, Conservation Technologies, Software Development, Publishing and New Media, and Outdoor Gear and Apparel. Three secondary targeted industries for Santa Fe to focus development in are health care, retiree services, and food & beverage. Angelou Economics recognized three economic signs that Santa Fe's economy was at risk of long-term deterioration. These signs were; a lack of business diversity which tied the city too closely to fluctuations in tourism and the government sector; the beginnings of urban sprawl, as a result of Santa Fe County growing faster than the city, meaning people will move farther outside the city to find land and lower costs for housing; and an aging population coupled with a rapidly shrinking population of individuals under 45 years old, making Santa Fe less attractive to business recruits. The seven industries recommended by the report "represent a good mix for short-, mid-, and long-term economic cultivation."[43]

Architectural highlights

- New Mexico State Capitol

- Cathedral Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi, the mother church of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Santa Fe

- Loretto Chapel

- Palace of the Governors

- San Miguel Mission and the rest of the Barrio De Analco Historic District

- Santuario de Guadalupe

- De Vargas Street House

- New Mexico Governor's Mansion

Districts

- Barrio De Analco Historic District

- Don Gaspar Historic District

- Santa Fe Historic District

- Santa Fe Railyard arts district

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 4,846 | — | |

| 1860 | 4,635 | −4.4% | |

| 1870 | 4,756 | 2.6% | |

| 1880 | 6,635 | 39.5% | |

| 1890 | 6,185 | −6.8% | |

| 1900 | 5,603 | −9.4% | |

| 1910 | 5,073 | −9.5% | |

| 1920 | 7,326 | 44.4% | |

| 1930 | 11,176 | 52.6% | |

| 1940 | 20,325 | 81.9% | |

| 1950 | 27,998 | 37.8% | |

| 1960 | 34,394 | 22.8% | |

| 1970 | 41,167 | 19.7% | |

| 1980 | 48,053 | 16.7% | |

| 1990 | 52,303 | 8.8% | |

| 2000 | 61,109 | 16.8% | |

| 2010 | 67,947 | 11.2% | |

| 2020 | 87,505 | 28.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[45][3] | |||

As of the 2020 census, there were 87,505 people living in the city, up from 67,947 in 2010, equating to an annual growth of close to 3%. As per the 2010 census, the racial makeup of the city residents was 78.9% White, 2.1% Native American; 1.4% Black, 1.4% Asian; and 3.7% from two or more races. A total of 48.7% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. Non-Hispanic Whites were 46.2% of the population.[46]

As of the census[47] of 2000, there were 62,203 people, 27,569 households, and 14,969 families living in the city. The population density was 1,666.1 people per square mile (643.4/km2). There were 30,533 housing units at an average density of 817.8 per square mile (315.8/km2). According to the Census Bureau's 2006 American Community Survey, the racial makeup of the city was 75% White, 2.5% Native American, 1.9% Asian, 0.4% African American, 0.3% Pacific Islander, 16.9% from other races, and 3.1% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 44.5% of the population.

There were 27,569 households, out of which 24.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.6% were married couples living together, 12.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 45.7% were non-families. 36.4% of all households were made up of individuals living alone, and 10.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.20 and the average family size was 2.90.

The age distribution was 20.3% under 18, 8.9% from 18 to 24, 29.0% from 25 to 44, 28.0% from 45 to 64, and 13.9% who were 65 or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.7 males. For every 100 women age 18 and over, there were 89.0 men.

The median income for a household in the city was $40,392, and the median income for a family was $49,705. Men had a median income of $32,373 versus $27,431 for women. The per capita income for the city was $25,454. About 9.5% of families and 12.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 17.2% of those under age 18 and 9.2% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and culture

.jpg.webp)

The city is well known as a center for arts that reflect the multicultural character of the city; it has been designated as a UNESCO Creative City in Design, Crafts and Folk Art.[48]

In 2012, the city was listed among the 10 best places to retire in the U.S. by CBS MoneyWatch and U.S. News & World Report.[49][50]

Visual arts

Canyon Road, east of the Plaza, has the highest concentration of art galleries in the city, and is a major destination for international collectors, tourists and locals. The Canyon Road galleries showcase a wide array of contemporary, Southwestern, indigenous American, and experimental art, in addition to Russian, Taos Masters, and Native American pieces.

Since its opening in 1995, SITE Santa Fe has been committed to supporting new developments in contemporary art, encouraging artistic exploration, and expanding traditional museum experiences. Launched in 1995 to organize the only international biennial of contemporary art in the United States, SITE Santa Fe has drawn global attention. The biennials are on par with such renowned exhibitions as the Whitney Biennial and the Venice Biennale.[51]

Santa Fe contains a lively contemporary art scene, with Meow Wolf as its main art collective. Backed by author George R. R. Martin,[52] Meow Wolf opened an elaborate art installation space, called House of Eternal Return, in 2016.[53]

There are many outdoor sculptures, including many statues of Francis of Assisi, and several other holy figures, such as Kateri Tekakwitha. The styles run the whole spectrum from Baroque to Post-modern.

Literature

Numerous authors followed the influx of specialists in the visual arts. Well-known writers like D. H. Lawrence, Cormac McCarthy, Michael Tobias, Kate Braverman, Douglas Adams, Tony Hillerman, Roger Zelazny, Alice Corbin Henderson, Mary Austin, Witter Bynner, Dan Flores, Paul Horgan, Rudolfo Anaya, George R. R. Martin, Mitch Cullin, David Morrell, Evan S. Connell, Richard Bradford, John Masters, Jack Schaefer, Hampton Sides, Ariel Gore and Michael McGarrity are or were residents of Santa Fe. Walker Percy lived on a dude ranch outside of Santa Fe before returning to Louisiana to begin his literary career.[54]

Media

Santa Fe's daily newspaper is the Santa Fe New Mexican and each Friday, it publishes Pasatiempo, its long-running calendar and commentary on arts and events. The Magazine has been the arts magazine of Santa Fe since its founding by Guy Cross in 1992. It publishes critical reviews and profiles New Mexico based artists monthly. Each Wednesday the alternative weekly newspaper, the Santa Fe Reporter, publishes information on the arts and culture of Santa Fe.

Video games

The 2006 racing video game Need For Speed: Carbon has an unused part of its Palmont City setting called San Juan, which you briefly play in, in the tutorial for the game's career mode. The San Juan setting is very loosely based on Santa Fe. It has New Mexico flags all over the roads.

- The Crew

- The Crew 2

Music, dance, and opera

Performance Santa Fe, formerly the Santa Fe Concert Association, is the oldest presenting organization in Santa Fe. Founded in 1937, Performance Santa Fe brings celebrated and legendary musicians as well as some of the world's greatest dancers and actors to the city year-round.[55] The Santa Fe Opera stages its productions between late June and late August each year. The city also hosts the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival which is held at about the same time, mostly in the St. Francis Auditorium and in the Lensic Theater. Also in July and August, the Santa Fe Desert Chorale holds its summer festival. Santa Fe has its own professional ballet company, Aspen Santa Fe Ballet, which performs in both cities and tours nationally and internationally. Santa Fe is also home to internationally acclaimed Flamenco dancer's María Benítez Institute for Spanish Arts which offers programs and performance in Flamenco, Spanish Guitar and similar arts year round. Other notable local figures include the National Dance Institute of New Mexico and German New Age musician Deuter.

Museums

Santa Fe has many museums located near the downtown Plaza:

- New Mexico Museum of Art – collections of modern and contemporary Southwestern art

- Museum of Contemporary Native Arts – contemporary Native American arts with political aspects

- Georgia O'Keeffe Museum – devoted to the work of O'Keeffe and others whom she influenced

- New Mexico History Museum – located behind the Palace of the Governors

- Site Santa Fe – a contemporary art space

Several other museums are located in the area known as Museum Hill:[56]

- Museum of International Folk Art – folk art from around the world

- Museum of Indian Arts and Culture – Native American arts

- Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian – Native American art and history

- Museum of Spanish Colonial Art – Tradition arts from the Spanish-colonial era to contemporary times.[57]

Sports

The New Mexico Style were an American Basketball Association franchise founded in 2005, but reformed in Texas for the 2007–08 season as the El Paso S'ol (which folded without playing an ABA game in their new city). The Santa Fe Roadrunners were a North American Hockey League team, but moved to Kansas to become the Topeka Roadrunners. Santa Fe's rodeo, the Rodeo De Santa Fe, is held annually the last week of June.[58] In May 2012, Santa Fe became the home of the Santa Fe Fuego of the Pecos League of Professional Baseball Clubs. They play their home games at Fort Marcy Ballfield. Horse racing events were held at The Downs at Santa Fe from 1971 until 1997.

Government

| City of Santa Fe Executive Branch[59] | |

| Mayor | Alan Webber |

| Mayor Pro-Tem | Peter Ives |

| City manager | Brian Snyder |

| City attorney | Kelley Brennan (interim)[60] |

| City clerk | Yolanda Y. Vigil, CMC |

| Municipal judge | Ann Yalman |

| Chief of police | Patrick Gallagher[61] |

| Fire chief | Erik Litzenberg |

| City councilors | Signe Lindel, Renee Villareal, Peter Ives, Joseph Maestas, Carmichael Domiguez, Christopher Rivera, Ronald S. Trujillo, Michael Harris |

The city of Santa Fe is a charter city.[62] It is governed by a mayor-council system. The city is divided into four electoral districts, each represented by two councilors. Councilors are elected to staggered four-year terms and one councilor from each district is elected every two years.[62]: Article VI

The municipal judgeship is an elected position and a requirement of the holder is that they be a member of the state bar. The judge is elected to four-year terms.[62]: Article VII

The mayor is the chief executive officer of the city and is a member of the governing body. The mayor has numerous powers and duties, and while previously the mayor could only vote when there was a tie among the city council, the city charter was amended by referendum in 2014 to allow the mayor to vote on all matters in front of the council. Starting in 2018, the position of mayor will be a full-time professional paid position within city government.[62]: Article V Day-to-day operations of the municipality are undertaken by the city manager's office.[62]: Article VIII

Federal operations

The Joseph M. Montoya Federal Building and Post Office serves as an office for U.S. federal government operations. It also contains the primary United States Postal Service post office in the city.[63] Other post offices in the Santa Fe city limits include Coronado,[64] De Vargas Mall,[65] and Santa Fe Place Mall.[66] The U.S. Courthouse building, constructed in 1889, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.[67]

Tourism

Touch the country [of New Mexico] and you will never be the same again.

— D. H. Lawrence, c. 1917.[68]

Tourism is a major element of the Santa Fe economy, with visitors attracted year-round by the climate and related outdoor activities (such as skiing in years of adequate snowfall; hiking in other seasons) plus cultural activities of the city and the region. Tourism information is provided by the convention and visitor bureau[69] and the chamber of commerce.[70]

Most tourist activity takes place in the historic downtown, especially on and around the Plaza, a one-block square adjacent to the Palace of the Governors, the original seat of New Mexico's territorial government since the time of Spanish colonization. Other areas include "Museum Hill", the site of the major art museums of the city as well as the Santa Fe International Folk Art Market, which takes place each year during the second full weekend of July. The Canyon Road arts area with its galleries is also a major attraction for locals and visitors alike.

Some visitors find Santa Fe particularly attractive around the second week of September when the aspens in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains turn yellow and the skies are clear and blue. This is also the time of the annual Fiestas de Santa Fe, celebrating the "reconquering" of Santa Fe by Don Diego de Vargas, a highlight of which is the burning Zozobra ("Old Man Gloom"), a 50-foot (15 m) marionette.

Popular day trips in the Santa Fe area include locations such as the town of Taos, about 70 mi (113 km) north of Santa Fe. The historic Bandelier National Monument and the Valles Caldera can be found about 30 mi (48 km) away. Santa Fe's ski resort, Ski Santa Fe, is about 16 mi (26 km) northeast of the city. Chimayo is also nearby and many locals complete the annual pilgrimage to the Santuario de Chimayo.

Science and technology

Santa Fe has had an association with science and technology since 1943 when the town served as the gateway to Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), a 45-minute drive from the city. In 1984, the Santa Fe Institute (SFI) was founded to research complex systems in the physical, biological, economic, and political sciences. It has hosted such Nobel laureates as Murray Gell-Mann (physics), Philip Warren Anderson (physics), and Kenneth Arrow (economics). The National Center for Genome Resources (NCGR)[71] was founded in 1994 to focus on research at the intersection among bioscience, computing, and mathematics. In the 1990s and 2000s several technology companies formed to commercialize technologies from LANL, SFI and NCGR.

Due to the presence of Los Alamos National Laboratory, Sandia National Laboratories and the Santa Fe Institute, and because of its attractiveness for visitors and an established tourist industry, Santa Fe routinely serves as a host to a variety of scientific meetings, summer schools, and public lectures, such as International q-bio Conference on Cellular Information Processing, Santa Fe Institute's Complex Systems Summer School,[72] and LANL's Center For Nonlinear Studies[73] Annual Conference.

Education

Santa Fe has three public high schools:

- Santa Fe High School (1,500 students)

- Capital High School (1,300 students)

- New Mexico School for the Arts (200 students)

Public schools in Santa Fe are operated by Santa Fe Public Schools, with the exception of the New Mexico School for the Arts, which is a public/private partnership comprising the NMSA-Art Institute, a nonprofit art educational institution, and NMSA-Charter School, an accredited New Mexico state charter high school.

The city's institutions of higher education include St. John's College, a liberal arts college; the Institute of American Indian Arts, a tribal college for Native American arts; Southwestern College, a graduate school for counseling and art therapy; and Santa Fe Community College.

The city has six private college preparatory high schools: Santa Fe Waldorf School,[74] St. Michael's High School, Desert Academy,[75] New Mexico School for the Deaf, Santa Fe Secondary School, Santa Fe Preparatory School, and the Mandela International Magnet School. The Santa Fe Indian School is an off-reservation school for Native Americans. Santa Fe is also the location of the New Mexico School for the Arts, a public-private partnership, arts-focused high school. The city has many private elementary schools as well, including Little Earth School,[76] Santa Fe International Elementary School,[77] Rio Grande School, Desert Montessori School,[78] La Mariposa Montessori, The Tara School, Fayette Street Academy, The Santa Fe Girls' School, The Academy for the Love of Learning, and Santa Fe School for the Arts and Sciences.

Transportation

Air

Santa Fe is served by the Santa Fe Municipal Airport. American Airlines provides regional jet service to Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport and Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport. United Airlines has regional jet service to Denver International Airport.

Road

Santa Fe is located on I-25. In addition, U.S. Routes 84 and 285 pass through the city, along St. Francis Drive. NM-599 forms a limited-access road bypass around the northwestern part of the city.

In its earliest alignment (1926–1937), U.S. Route 66 ran through Santa Fe.[79]

Public transportation

Santa Fe Trails, run by the city, operates a number of bus routes within the city during business hours and also provides connections to regional transit.

The New Mexico Rail Runner Express is a commuter rail service operating in Valencia, Bernalillo (including Albuquerque), Sandoval, and Santa Fe Counties. In Santa Fe County, the service uses 18 miles (29 km) of new right-of-way connecting the BNSF Railway's old transcontinental mainline to existing right-of-way in Santa Fe used by the Santa Fe Southern Railway. Santa Fe is currently served by four stations, Santa Fe Depot, South Capitol, Zia Road, and Santa Fe County/NM 599.

New Mexico Park and Ride, a division of the New Mexico Department of Transportation, and the North Central Regional Transit District operate primarily weekday commuter coach/bus service to Santa Fe from Torrance, Rio Arriba, Taos, San Miguel and Los Alamos Counties in addition to shuttle services within Santa Fe connecting major government activity centers.[80][81] Prior to the Rail Runner's extension to Santa Fe, Park and Ride operated commuter coach service between Albuquerque and Santa Fe.

Greyhound Lines serves Santa Fe on its route from Denver to El Paso, Texas. Groome Transportation provides shuttles between Santa Fe and the Albuquerque International Sunport.[82]

Rail

Along with the New Mexico Rail Runner Express, a commuter rail line serving the metropolitan areas of Albuquerque and Santa Fe, the city or its environs are served by two other railroads. The Santa Fe Southern Railway, now mostly a tourist rail experience but also carrying freight, operates excursion services out of Santa Fe as far as Lamy, 15 miles (24 km) to the southeast. The Santa Fe Southern line is one of the United States' few rails with trails. Lamy is also served by Amtrak's daily Southwest Chief for train service to Chicago, Los Angeles, and intermediate points. Passengers transiting Lamy may use a special connecting coach/van service to reach Santa Fe.

Trails

Multi-use bicycle, pedestrian, and equestrian trails are increasingly popular in Santa Fe, for both recreation and commuting. These include the Dale Ball Trails, a 24.4-mile (39.3 km) network starting within two miles (3.2 km) of the Santa Fe Plaza; the long Santa Fe Rail Trail to Lamy; the Atalaya Trail up Atalaya Mountain; and the Santa Fe River Trail. Santa Fe is the terminus of three National Historic Trails: El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail, the Old Spanish National Historic Trail, and the Santa Fe National Historic Trail.

Sister cities and twin towns

Santa Fe's sister cities are:[83]

Bukhara, Bukhara Region, Uzbekistan (1988)

Bukhara, Bukhara Region, Uzbekistan (1988) Hidalgo del Parral, Chihuahua, Mexico (1984)

Hidalgo del Parral, Chihuahua, Mexico (1984) Holguín, Holguín Province, Cuba (2001)

Holguín, Holguín Province, Cuba (2001) Icheon, Gyeonggi-do, South Korea (2013)

Icheon, Gyeonggi-do, South Korea (2013) Livingstone, Southern Province, Zambia (2012)

Livingstone, Southern Province, Zambia (2012) San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato, Mexico (1992)

San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato, Mexico (1992) Santa Fe, Granada Province, Spain (1983)

Santa Fe, Granada Province, Spain (1983) Sorrento, Campania, Italy (1995)

Sorrento, Campania, Italy (1995) Tsuyama, Okayama, Japan (1992)

Tsuyama, Okayama, Japan (1992) Zhangjiajie, Hunan, China (2009)

Zhangjiajie, Hunan, China (2009)

Notable people

- David W. Alexander (1812–1886), Los Angeles politician and sheriff

- Antonio Armijo (1804–1850), explorer and merchant who led the first commercial caravan between Santa Fe, Nuevo México and Los Angeles, Alta California in 1829–1830

- Mary Hunter Austin (1868–1934), writer

- Gustave Baumann (1881–1971), print-maker, marionette-maker and painter; resident artist for more than fifty years; died in Santa Fe

- William Berra (born 1952), painter

- Florence Birdwell (1924–2021), musician, teacher

- Merrill Brockway (1923–2013), Emmy Award-winning producer, director

- Dana Tai Soon Burgess (born 1968), dancer, choreographer

- Paul Burlin (1886–1969), modern and abstract expressionist painter

- Witter Bynner (1881–1968), poet

- Julia Cameron (1948), author of The Artist's Way

- Dana B. Chase (1848–1897), photographer

- Zach Condon (born 1986), lead singer and songwriter of band Beirut

- Bronson M. Cutting (1888–1935), politician, newspaper publisher and military attaché

- Chris Eyre (born 1968), actor, director

- Jane Fonda (born 1937), actress; owner of Forked Lightning Ranch[84]

- Tom Ford (born 1961), fashion designer[85]

.jpg.webp)

- Garance Franke-Ruta (born 1972), journalist

- T. Charles Gaastra (1879–1947), architect in the Pueblo Revival Style

- Greer Garson (1904–1996), actress and philanthropist

- Laura Gilpin, (1891–1979), photographer and author

- John Grubesic (born 1965), New Mexico State Senator, representing the 25th District as a Democrat

- Anna Gunn (born 1968), Emmy-winning actress

- Gene Hackman (born 1930), Oscar-winning actor

- Edgar Lee Hewett (1865–1946), archaeologist and anthropologist[86]

- Dorothy B. Hughes (1904–1993), novelist and literary critic

- John Brinckerhoff Jackson (1909–1996), landscape architect

- Jeffe Kennedy, author

- Matt King, artist, co-founder of Meow Wolf[87]

- Jean Kraft (1927–2021), operatic singer (mezzo-soprano)

- Oliver La Farge (1901–1963), writer

- Jean Baptiste LeLande (1778–1821), merchant

- Jean-Baptiste Lamy (1814–1888), first Archbishop of Santa Fe

- Marjorie Herrera Lewis (born 1957), author

- Ali MacGraw (born 1939), actress

- Shirley MacLaine (born 1934), actress[88]

- George R. R. Martin (born 1948), author and screenwriter, Game of Thrones

- Cormac McCarthy (born 1933), author, winner of Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

- Christine McHorse (1948–2021), ceramic artist

- Dorothy McKibbin (1897–1985), gatekeeper and point-of-contact for personnel at the Manhattan Project

- John Gaw Meem (1894–1983) Architect who popularized the Pueblo Revival style

- Sylvanus Morley (1883–1948), archaeologist and Mayanist

- John Nieto (1936–2018), contemporary artist

- Jesse L. Nusbaum (1887–1975), archaeologist, anthropologist, photographer and National Park Service Superintendent

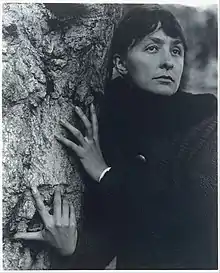

- Georgia O'Keeffe (1887–1986), artist, winner of National Medal of Arts

- Elliot Porter (1901–1990), photographer

- Robert Redford (born 1936), actor, director[89]

- Wendy Rule (born 1966) Australian-born musician

- Hib Sabin (born 1935), indigenous-style sculptor

- Manuel de Sandoval, colonial governor of Texas. He was the only native of New Mexico that governed Spanish Texas

- Brad Sherwood (born 1964), actor and comedian

- Wes Studi (born 1947), actor and musician

- Teal Swan (born 1984), spiritual guru and author

- Sheri S. Tepper (1929–2016), writer[90]

- Charlene Teters (born 1952), artist, activist

- Michael Charles Tobias (born 1951), author and global ecologist

- Stanislaw Ulam (1909–1984), mathematician associated with the Manhattan Project

- Jeremy Ray Valdez (born 1980), actor

- Lew Wallace (1827–1905), territorial governor 1878–1881, and author of Ben-Hur

- Tuesday Weld (born 1943), actress[91]

- Josh West (born 1977), Olympic medalist rower and Earth Sciences professor

- Roger Zelazny (1937–1995), writer

- Pinchas Zukerman (born 1948), violinist, conductor[91]

See also

- Homewise, founded in 1986

- National Old Trails Road

- Santa Fe Trail

References

- "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- United States Geological Survey

- "Census Population API". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved Oct 12, 2022.

- "Santa Fe (New Mexico, United States)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on May 12, 2011. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- "The Story Behind 54 American Cities Named After Catholic Saints". 7 July 2016. Archived from the original on 2018-02-11. Retrieved 2018-02-11.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "American Latino Heritage: San Gabriel de Yunque-Ouinge; San Juan Pueblo, New Mexico". National Park Service. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- McMullen, Matt (December 6, 2004). "What state's capital city is at the highest elevation?". CNET.

- McClure, Rosemary (5 October 2015). "Shop for world-class art in a laid-back setting in Santa Fe, N.M." Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- Tutelian, Louise (8 January 2009). "The Thrifty Wintry Charms of Santa Fe, New Mexico". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- Gleye, Paul (1994). "SANTA FE WITHOUT ADOBE: LESSONS FOR THE IDENTITY OF PLACE". Journal of Architectural and Planning Research. Locke Science Publishing Company, Inc. 11 (3): 181–196. ISSN 0738-0895. JSTOR 43029123. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- Sanchez, F. Richard (2010). White Shell Water Place, An Anthology of Native American Reflections on the 400th Anniversary of the Founding of Santa Fe, New Mexico. Santa Fe. ISBN 978-0865347861.

- "Yootó – Wiktionary". en.wiktionary.org.

- "Tourism: Santa Fe History". santafe.org. Archived from the original on October 20, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- "Ay no! Accent mark in official Santa Fe seal in wrong spot". Associated Press. March 4, 2020. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- Cross, Mark (November 11, 2011). "How to pronounce Santa Fe". Encyclopedia of Santa Fe and Northern New Mexico. Archived from the original on May 27, 2016. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- The town's name originally had an accent on Fé, but it is no longer needed in Spanish due to a spelling reform which removed it because there was no other word *fe that it would have clashed with (as with ti).

- Hazen-Hammond, Susan (1988). A Short History of Santa Fe. San Francisco: Lexikos. p. 132. ISBN 0938530399.

- Hazen-Hammond, Susan (1988). A Short History of Santa Fe. San Francisco: Lexikos. p. 132. ISBN 0938530399.

- Handwerk, Brian. "Santa Fe Tops 2007 List of Most Endangered Rivers". National Geographic. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

- "Santa Fe – A Rich History". City of Santa Fe. Archived from the original on December 14, 2012. Retrieved October 12, 2008.

- Garrard, Lewis H. (1955) [1850]. Wah-to-yah and the Taos Trail. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Cohen, Jared (2019). Accidental presidents: eight men who changed America (1st Simon & Schuster hardcover ed.). New York. ISBN 978-1501109829. OCLC 1039375326.

- Letter in The Arkansas Banner, 8-31-1849 in Marta Weigle; Kyle Fiore (2008). Santa Fe and Taos: The Writer's Era, 1916–1941. Sunstone Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0865346505. Archived from the original on 2016-01-25. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

- Paul Horgan (1975). Lamy of Santa Fe; A Biography.

- The Indian Sentinel, Volumes 7-10-Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions, 1927

- Leo Crane (1972). Desert drums: The Pueblo Indians of New Mexico, 1540–1928. Rio Grande Press.

- Anton Docher (1913). "The Quaint Indian Pueblo of Isleta". The Santa Fé Magazine. 7 (7): 29–32.

- "Santa Fe Southern Railway, Santa Fe, NM". Sfsr.com. Archived from the original on 2015-05-06.

- "Santa Fe, NM". Ghostdepot.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-06.

- Harry Moul; Linda Tigges (Spring 1996). "The Santa Fe 1912 City Plan: A 'City Beautiful' and City Planning Document". New Mexico Historical Review. 71 (2): 135–155.

- Carter Jones Meyer (September 2006). "The Battle between 'Art' and 'Progress': Edgar L. Hewett and the Politics of Region in the Early-Twentieth-Century Southwest". Montana: The Magazine of Western History. 56 (3): 47–61.

- Russell, Andrew B. (April 30, 2008). "The Nikkei in New Mexico". Discover Nikkei. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- "Santa Fe (detention facility)". Densho Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2015-02-23. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- Jeffrey Burton; Mary Farrell; Florence Lord; Richard Lord (2000). "Department of Justice Internment Camps: Santa Fe, New Mexico". Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2016-03-25. Retrieved 17 Jan 2017.

- "New Mexico Office of the State Historian : Japanese-American Internment Camps". Archived from the original on 2013-04-15. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- "Interactive United States Koppen–Geiger Climate Classification Map". www.plantmaps.com. Archived from the original on 2018-10-11. Retrieved 2018-10-21.

- "Updated Köppen-Geiger climate map of the world". University of Melbourne. Retrieved 2018-10-21.

- "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on January 19, 2015. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991-2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- Hammett, p.14

- Hammett, p.15: "They ripped off the cast-iron storefronts, tore down the gingerbread trim, took off the Victorian brackets and dentils ..."

- "Cultivating Santa Fe's Future Economy: Target Industry Report". Angelou Economics. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2012. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

- "Santuario de Guadalupe, Santa Fe, New Mexico". Waymarking.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-07. Retrieved 2012-05-16.

- "Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "State & County QuickFacts: Santa Fe (city), New Mexico". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Santa Fe, United States UNESCO City of Design, Crafts and Folk Art". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 2017-01-18. Retrieved 2017-01-18.

- Smith, Nancy F. (March 8, 2012). "The 10 Best Places to Retire". CBS MoneyWatch. Archived from the original on December 12, 2018. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- Brandon, Emily (October 20, 2012). "The 10 Best Places to Retire in 2012". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015.

- "Organizational History". SITE Santa Fe.

- Monroe, Rachel (February 11, 2015). "How George RR Martin is helping stem Santa Fe's youth exodus". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on October 17, 2018. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- Davis, Ben (July 14, 2016). "Is This Art Space Backed by Game of Thrones Author George R. R. Martin a Force of Good or Evil?". Artnet News. Archived from the original on 15 July 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- Harrelson, Barbara (February 2, 2013). "Walks in Literary Santa Fe". CSPAN. Archived from the original on April 6, 2019. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- "Performance Santa Fe". performancesantafe.org. Archived from the original on October 20, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "Museum Hill homepage". Archived from the original on August 12, 2006.

- "Spanish Colonial Arts Society | Santa Fe, New MexicoSpanish Colonial Arts Society | Non-Profit, Preservation, Collection". www.spanishcolonial.org. Archived from the original on October 5, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "Santa Fe Rodeo". Archived from the original on 2008-05-16. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- "Elected Officials". City of Santa Fe. Archived from the original on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- "City Attorney". City of Santa Fe. Archived from the original on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- "Contact Police & Emergency Numbers". Archived from the original on 2017-02-28. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- "Santa Fe Municipal Charter" (PDF). City of Santa Fe. March 4, 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 14, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- "Post Office Location – Santa Fe main". United States Postal Service. Archived from the original on July 23, 2012. Retrieved July 5, 2009.

- "Post Office Location – Coronado". United States Postal Service. Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- "Post Office Location – De Vargas Mall". United States Postal Service. Archived from the original on February 9, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- "Post Office Location – Santa Fe Place Mall". United States Postal Service. Archived from the original on July 20, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- Shukman, Henry (February 7, 2010). "Santa Fe, N.M., and How It Came to Be as It is". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 9, 2010. Retrieved February 7, 2010.

- "Visit Santa Fe, New Mexico – The City Different". Santa Fe.org. February 3, 2011. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- "Santa Fe Chamber of Commerce Home". Santafechamber.com. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- "National Center for Genome Resources". Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- "Complex Systems Summer School". Santa Fe Institute. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- "Center For Nonlinear Studies". Archived from the original on 2008-10-06. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- "Welcome". Santa Fe Waldorf School. Archived from the original on October 20, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "Home". Desert Academy – International Baccalaureate (IB) World School. Archived from the original on October 20, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "Little Earth School". littleearthschool.org. Archived from the original on September 3, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "Santa Fe International Elementary School K–8". Archived from the original on February 8, 2011. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "Home | Desert Montessori School". Desert Montessori School. Archived from the original on January 18, 2010. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "Description and Historic Context for Pre-1937 Highway Alignments". Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "New Mexico Park and Ride Schedule" (PDF). New Mexico Department of Transportation. December 22, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2009. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- "NCRTD Bus Routes Overview". North Central Regional Transit District. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- "Santa Fe Shuttle – Groome Transportation".

- "Sister Cities". City of Santa Fe. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- Annette Tapert (February 28, 2014). "Jane Fonda's New Mexico Ranch". Architectural Digest.

- Bear, Rob (December 12, 2013). "The Homes of Fashion Designer and Film Director Tom Ford". Curbed. Archived from the original on October 1, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "Dr. Edgar L. Hewett Dies in Albuquerque". Santa Fe New Mexican. December 31, 1946. Retrieved May 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Adams, Abagail (12 July 2022). "Matt King, Co-Founder of Popular Art Experience Meow Wolf, Dies at 37: 'Community Is Devastated'". People Magazine. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- Taylor, Candace (November 18, 2014). "Shirley MacLaine Ignores Psychics, Lists New Mexico Ranch for $18 Million". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on October 20, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- Taylor, Candace (September 14, 2018). "The not-quite retiring Robert Redford". CNBC News. Archived from the original on October 10, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "About Ms. Tepper – Sheri S. Tepper". January 21, 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-01-21. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- Stephen Wigler (July 7, 1996). "Leading The Way Music". The Baltimore Sun.

Further reading

- Dick, Robert H. (2006). My Time There: The Art Colonies of Santa Fe and Taos, New Mexico 1956–2006. St. Louis Mercantile Library, University of Missouri. ISBN 978-0963980489.

- Hammett, Kingsley (2004). Santa Fe: A Walk Through Time. Layton, Utah: Gibbs Smith. ISBN 1586851020.

- La Farge, John Pen (2006). Turn Left at the Sleeping Dog: Scripting the Santa Fe Legend, 1920–1955. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0826320155.

- Lovato, Andrew Leo (2006). Santa Fe Hispanic Culture: Preserving Identity in a Tourist Town. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0826332264.

- Noble, David Grant (2008). Santa Fe: History of an Ancient City (2nd ed.). School for Advanced Research Press. ISBN 978-1934691045.

- Wilson, Chris (1997). The Myth of Santa Fe: Creating a Modern Regional Tradition. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0826317464.