Texas annexation

The Texas annexation was the 1845 annexation of the Republic of Texas into the United States. Texas was admitted to the Union as the 28th state on December 29, 1845.

The Republic of Texas declared independence from the Republic of Mexico on March 2, 1836. It applied for annexation to the United States the same year, but was rejected by the Secretary of State. At the time, the vast majority of the Texian population favored the annexation of the Republic by the United States. The leadership of both major U.S. political parties, the Democrats and the Whigs, opposed the introduction of Texas, a vast slave-holding region, into the volatile political climate of the pro- and anti-slavery sectional controversies in Congress. Moreover, they wished to avoid a war with Mexico, whose government had outlawed slavery and refused to acknowledge the sovereignty of its rebellious northern province. With Texas's economic fortunes declining by the early 1840s, the President of the Texas Republic, Sam Houston, arranged talks with Mexico to explore the possibility of securing official recognition of independence, with the United Kingdom mediating.

In 1843, U.S. President John Tyler, then unaligned with any political party, decided independently to pursue the annexation of Texas in a bid to gain a base of support for another four years in office. His official motivation was to outmaneuver suspected diplomatic efforts by the British government for the emancipation of slaves in Texas, which would undermine slavery in the United States. Through secret negotiations with the Houston administration, Tyler secured a treaty of annexation in April 1844. When the documents were submitted to the U.S. Senate for ratification, the details of the terms of annexation became public and the question of acquiring Texas took center stage in the presidential election of 1844. Pro-Texas-annexation southern Democratic delegates denied their anti-annexation leader Martin Van Buren the nomination at their party's convention in May 1844. In alliance with pro-expansion northern Democratic colleagues, they secured the nomination of James K. Polk, who ran on a pro-Texas Manifest Destiny platform.

In June 1844, the Senate, with its Whig majority, soundly rejected the Tyler–Texas treaty. The pro-annexation Democrat Polk narrowly defeated anti-annexation Whig Henry Clay in the 1844 presidential election. In December 1844, lame-duck President Tyler called on Congress to pass his treaty by simple majorities in each house. The Democratic-dominated House of Representatives complied with his request by passing an amended bill expanding on the pro-slavery provisions of the Tyler treaty. The Senate narrowly passed a compromise version of the House bill (by the vote of the minority Democrats and several southern Whigs), designed to provide President-elect Polk the options of immediate annexation of Texas or new talks to revise the annexation terms of the House-amended bill.

On March 1, 1845, President Tyler signed the annexation bill, and on March 3 (his last full day in office), he forwarded the House version to Texas, offering immediate annexation (which preempted Polk). When Polk took office at noon EST the next day, he encouraged Texas to accept the Tyler offer. Texas ratified the agreement with popular approval from Texans. The bill was signed by President Polk on December 29, 1845, accepting Texas as the 28th state of the Union. Texas formally joined the union on February 19, 1846. Following the annexation, relations between the United States and Mexico deteriorated because of an unresolved dispute over the border between Texas and Mexico, and the Mexican–American War broke out only a few months later.

| History of Texas | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Background information

U.S. territorial expansion and Texas

First mapped by Spain in 1519, Texas was part of the vast Spanish empire seized by the Spanish Conquistadors from its indigenous people for over 300 years.[1] When the Louisiana territory was acquired by the United States from France in 1803, many in the U.S. believed the new territory included parts or all of present-day Texas.[2] The US-Spain border along the northern frontier of Texas took shape in the 1817–1819 negotiations between Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and the Spanish ambassador to the United States, Luis de Onís y González-Vara.[3] The boundaries of Texas were determined within the larger geostrategic struggle to demark the limits of the United States' extensive western lands and of Spain's vast possessions in North America.[4] The Florida Treaty of February 22, 1819[5][6] emerged as a compromise that excluded Spain from the lower Columbia River watershed, but established southern boundaries at the Sabine and Red Rivers, "legally extinguish[ing]" any American claims to Texas.[7][8] Nonetheless, Texas remained an object of fervent interest to American expansionists, among them Thomas Jefferson, who anticipated the eventual acquisition of its fertile lands.[9]

The Missouri crisis of 1819–1821 sharpened commitments to expansionism among the country's slaveholding interests, when the so-called Thomas proviso established the 36°30' parallel, imposing free-soil and slave-soil futures in the Louisiana Purchase lands.[10] While a majority of southern congressmen acquiesced to the exclusion of slavery from the bulk of the Louisiana Purchase, a significant minority objected.[11][12] Virginian editor Thomas Ritchie of the Richmond Enquirer predicted that with the proviso restrictions, the South would ultimately require Texas: "If we are cooped up on the north, we must have elbow room to the west."[13][14] Representative John Floyd of Virginia in 1824 accused Secretary of State Adams of conceding Texas to Spain in 1819 in the interests of Northern anti-slavery advocates, and so depriving the South of additional slave states.[15] Then-Representative John Tyler of Virginia invoked the Jeffersonian precepts of territorial and commercial growth as a national goal to counter the rise of sectional differences over slavery. His "diffusion" theory declared that with Missouri open to slavery, the new state would encourage the transfer of underutilized slaves westward, emptying the eastern states of bondsmen and making emancipation feasible in the old South.[16] This doctrine would be revived during the Texas annexation controversy.[17][18]

When Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821,[19] the United States did not contest the new republic's claims to Texas, and both presidents John Quincy Adams (1825–1829) and Andrew Jackson (1829–1837) persistently sought, through official and unofficial channels, to procure all or portions of provincial Texas from the Mexican government, without success.[20]

Texas settlement and independence

Spanish and Indigenous immigrants, primarily from northeastern provinces of New Spain, began to settle Texas in the late 17th century. The Spanish constructed chains of missions and presidios in what is today Louisiana, east Texas, and south Texas. The first chain of missions was designed for the Tejas Indians, near Los Adaes. Soon thereafter, the San Antonio Missions were founded along the San Antonio River. The City of San Antonio, then known as San Fernando de Bexar, was founded in 1718. In the early 1760s, José de Escandón created five settlements along the Rio Grande River, including Laredo.

Anglo-American immigrants, primarily from the Southern United States, began emigrating to Mexican Texas in the early 1820s at the invitation of the Texas faction of the Coahuila Texas state government, which sought to populate the sparsely inhabited lands of its northern frontier for cotton production.[21][22] Colonizing empresario Stephen F. Austin managed the regional affairs of the mostly American-born population – 20% of them slaves[23] – under the terms of the generous government land grants.[24] Mexican authorities were initially content to govern the remote province through salutary neglect, "permitting slavery under the legal fiction of 'permanent indentured servitude', similar to Mexico's peonage system.[25]

A general lawlessness prevailed in the vast Texas frontier, and Mexico's civic laws went largely unenforced among the Anglo-American settlers. In particular, the prohibitions against slavery and forced labor were ignored. The requirement that all settlers be Catholic or convert to Catholicism was also subverted.[26][27] Mexican authorities, perceiving that they were losing control over Texas and alarmed by the unsuccessful Fredonian Rebellion of 1826, abandoned the policy of benign rule. New restrictions were imposed in 1829–1830, outlawing slavery throughout the nation and terminating further American immigration to Texas.[28][29] Military occupation followed, sparking local uprisings and a civil war. Texas conventions in 1832 and 1833 submitted petitions for redress of grievances to overturn the restrictions, with limited success.[30] In 1835, an army under Mexican President Santa Anna entered its territory of Texas and abolished self-government. Texans responded by declaring their independence from Mexico on March 2, 1836. On April 20–21, rebel forces under Texas General Sam Houston defeated the Mexican army at the Battle of San Jacinto.[31][32] In June 1836 while held prisoner by the Texans, Santa Anna signed an agreement for Texas independence, but the Mexican government refused to ratify the agreement made under duress.[33] Texans, now de facto independent, recognized that their security and prosperity could never be achieved while Mexico denied the legitimacy of their revolution.[34]

In the years following independence, the migration of white settlers and importation of black slave labor into the vast republic was deterred by Texas's unresolved international status and the threat of renewed warfare with Mexico.[35] American citizens who considered migrating to the new republic perceived that "life and property were safer within the United States" than in an independent Texas.[36] In the 1840s, global oversupply had also caused a crash in the price of cotton, the country's main export commodity.[37] The situation led to labor shortages, reduced tax revenue, large national debts and a diminished Texas militia.[38][39]

Jackson and Van Buren administrations

The Anglo-American immigrants residing in newly independent Texas overwhelmingly desired immediate annexation by the United States.[40] But, despite his strong support for Texas independence from Mexico,[41] then-President Andrew Jackson delayed recognizing the new republic until the last day of his presidency to avoid raising the issue during the 1836 general election.[42][43] Jackson's political caution was dictated by northern concerns that Texas could potentially form several new slave states and undermine the North-South balance in Congress.[44]

Jackson's successor, President Martin Van Buren, viewed Texas annexation as an immense political liability that would empower the anti-slavery northern Whig opposition – especially if annexation provoked a war with Mexico.[45] Presented with a formal annexation proposal from Texas minister Memucan Hunt, Jr. in August 1837, Van Buren summarily rejected it.[46] Annexation resolutions presented separately in each house of Congress were either soundly defeated or tabled through filibuster. After the election of 1838, new Texas president Mirabeau B. Lamar withdrew his republic's offer of annexation over these failures.[47] Texans were at an annexation impasse when John Tyler entered the White House in 1841.[48]

Tyler administration

William Henry Harrison, Whig Party presidential nominee, defeated US President Martin Van Buren in the 1840 general election. Upon Harrison's death shortly after his inauguration, Vice-President John Tyler assumed the presidency.[49] President Tyler was expelled from the Whig party in 1841 for repeatedly vetoing their domestic finance legislation. Tyler, isolated and outside the two-party mainstream, turned to foreign affairs to salvage his presidency, aligning himself with a southern states' rights faction that shared his fervent slavery expansionist views.[50]

In his first address to Congress in special session on June 1, 1841, Tyler set the stage for Texas annexation by announcing his intention to pursue an expansionist agenda so as to preserve the balance between state and national authority and to protect American institutions, including slavery, so as to avoid sectional conflict.[51] Tyler's closest advisors counseled him that obtaining Texas would assure him a second term in the White House,[52] and it became a deeply personal obsession for the president, who viewed the acquisition of Texas as the "primary objective of his administration".[53] Tyler delayed direct action on Texas to work closely with his Secretary of State Daniel Webster on other pressing diplomatic initiatives.[54]

With the Webster-Ashburton Treaty ratified in 1843, Tyler was ready to make the annexation of Texas his "top priority".[55] Representative Thomas W. Gilmer of Virginia was authorized by the administration to make the case for annexation to the American electorate. In a widely circulated open letter, understood as an announcement of the executive branch's designs for Texas, Gilmer described Texas as a panacea for North-South conflict and an economic boon to all commercial interests. The slavery issue, however divisive, would be left for the states to decide as per the US Constitution. Domestic tranquility and national security, Tyler argued, would result from an annexed Texas; a Texas left outside American jurisdiction would imperil the Union.[56] Tyler adroitly arranged the resignation of his anti-annexation Secretary of State Daniel Webster, and on June 23, 1843 appointed Abel P. Upshur, a Virginia states' rights champion and ardent proponent of Texas annexation. This cabinet shift signaled Tyler's intent to pursue Texas annexation aggressively.[57]

Tyler–Upshur–Calhoun campaign for Texas

In late September 1843, in an effort to cultivate public support for Texas, Secretary Upshur dispatched a letter to the US Minister to Great Britain, Edward Everett, conveying his displeasure with Britain's global anti-slavery posture, and warning their government that forays into Texas's affairs would be regarded as "tantamount to direct interference 'with the established institutions of the United States'".[58] In a breach of diplomatic norms, Upshur leaked the communique to the press to inflame popular Anglophobic sentiments among American citizens.[59]

In the spring of 1843, the Tyler administration had sent executive agent Duff Green to Europe to gather intelligence and arrange territorial treaty talks with Great Britain regarding Oregon; he also worked with American minister to France, Lewis Cass, to thwart efforts by major European powers to suppress the maritime slave trade.[60] Green reported to Secretary Upshur in July 1843 that he had discovered a "loan plot" by American abolitionists, in league with Lord Aberdeen, British Foreign Secretary, to provide funds to the Texans in exchange for the emancipation of its slaves.[61] Minister Everett was charged with determining the substance of these confidential reports alleging a Texas plot. His investigations, including personal interviews with Lord Aberdeen, concluded that British interest in abolitionist intrigues was weak, contradicting Secretary of State Upshur's conviction that Great Britain was manipulating Texas.[62] Though unsubstantiated, Green's unofficial intelligence so alarmed Tyler that he requested verification from the US minister to Mexico, Waddy Thompson.[63]

John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, a pro-slavery extremist,[64] counseled Secretary Upshur that British designs on American slavery were real and required immediate action to preempt a takeover of Texas by the United Kingdom. When Tyler confirmed in September that the British Foreign Secretary Aberdeen had encouraged détente between Mexico and Texas, allegedly pressing Mexico to maneuver Texas towards emancipation of its slaves, Tyler acted at once.[65][66] On September 18, 1843, in consultation with Secretary Upshur, he ordered secret talks opened with Texas Minister to the United States Isaac Van Zandt to negotiate the annexation of Texas.[67] Face-to-face negotiations commenced on October 16, 1843.[68]

Texas–Mexico–United Kingdom negotiations

By the summer of 1843 Sam Houston's Texas administration had returned to negotiations with the Mexican government to consider a rapprochement that would permit Texas self-governance, possibly as a state of Mexico, with Great Britain acting as mediator.[69][70] Texas officials felt compelled by the fact that the Tyler administration appeared unequipped to mount an effective campaign for Texas annexation.[71] With the 1844 general election in the United States approaching, the leadership in both the Democratic and Whig parties remained unequivocally anti-Texas.[72] Texas-Mexico treaty options under consideration included an autonomous Texas within Mexico's borders, or an independent republic with the provision that Texas should emancipate its slaves upon recognition.[73]

Van Zandt, though he personally favored annexation by the United States, was not authorized to entertain any overtures from the US government on the subject. Texas officials were at the moment deeply engaged in exploring settlements with Mexican diplomats, facilitated by Great Britain. Texas's predominant concern was not British interference with the institution of slavery – English diplomats had not alluded to the issue – but the avoidance of any resumption of hostilities with Mexico.[74] Still, US Secretary of State Upshur vigorously courted Texas diplomats to begin annexation talks, finally dispatching an appeal to President Sam Houston in January 1844. In it, he assured Houston that, in contrast to previous attempts, the political climate in the United States, including sections of the North, was amenable to Texas statehood, and that a two-thirds majority in Senate could be obtained to ratify a Texas treaty.[75]

Texans were hesitant to pursue a US-Texas treaty without a written commitment of military defense from America, since a full-scale military attack by Mexico seemed likely when the negotiations became public. If ratification of the annexation measure stalled in the US Senate, Texas could face a war alone against Mexico.[76] Because only Congress could declare war, the Tyler administration lacked the constitutional authority to commit the US to support of Texas. But when Secretary Upshur provided a verbal assurance of military defense, President Houston, responding to urgent calls for annexation from the Texas Congress of December 1843, authorized the reopening of annexation negotiations.[77]

The US–Texas treaty negotiations

As Secretary Upshur accelerated the secret treaty discussions, Mexican diplomats learned that US-Texas talks were taking place. Mexican minister to the U.S. Juan Almonte confronted Upshur with these reports, warning him that if Congress sanctioned a treaty of annexation, Mexico would break diplomatic ties and immediately declare war.[78] Secretary Upshur evaded and dismissed the charges, and pressed forward with the negotiations.[79] In tandem with moving forward with Texas diplomats, Upshur was secretly lobbying US Senators to support annexation, providing lawmakers with persuasive arguments linking Texas acquisition to national security and domestic peace. By early 1844, Upshur was able to assure Texas officials that 40 of the 52 members of the Senate were pledged to ratify the Tyler-Texas treaty, more than the two-thirds majority required for passage.[80] Tyler, in his annual address to Congress in December 1843, maintained his silence on the secret treaty, so as not to damage relations with the wary Texas diplomats.[81] Throughout, Tyler did his utmost to keep the negotiations secret, making no public reference to his administration's single-minded quest for Texas.[82]

The Tyler-Texas treaty was in its final stages when its chief architects, Secretary Upshur and Secretary of the Navy Thomas W. Gilmer, died in an accident aboard USS Princeton on February 28, 1844, just a day after achieving a preliminary treaty draft agreement with the Texas Republic.[83] The Princeton disaster proved a major setback for Texas annexation, in that Tyler expected Secretary Upshur to elicit critical support from Whig and Democratic Senators during the upcoming treaty ratification process.[84] Tyler selected John C. Calhoun to replace Upshur as Secretary of State and to finalize the treaty with Texas. The choice of Calhoun, a highly regarded but controversial American statesman,[85] risked introducing a politically polarizing element into the Texas debates, but Tyler prized him as a strong advocate of annexation.[86][87]

Robert J. Walker and the "safety-valve"

With the Tyler-Upshur secret annexation negotiations with Texas near consummation, Senator Robert J. Walker of Mississippi, a key Tyler ally, issued a widely distributed and highly influential letter, reproduced as a pamphlet, making the case for immediate annexation.[88] In it, Walker argued that Texas could be acquired by Congress in a number of ways – all constitutional – and that the moral authority to do so was based on the precepts for territorial expansion established by Jefferson and Madison, and promulgated as doctrine by Monroe in 1823.[89] Senator Walker's polemic offered analysis on the significance of Texas with respect to slavery and race. He envisioned Texas as a corridor through which both free and enslaved African-Americans could be "diffused" southward in a gradual exodus that would ultimately supply labor to the Central American tropics, and in time, empty the United States of its slave population.[90]

This "safety-valve" theory "appealed to the racial fears of northern whites" who dreaded the prospect of absorbing emancipated slaves into their communities if the institution of slavery collapsed in the South.[91] This scheme for racial cleansing was consistent, on a pragmatic level, with proposals for overseas colonization of blacks, which were pursued by a number of American presidents, from Jefferson to Lincoln.[92] Walker bolstered his position by raising national security concerns, warning that in the event annexation failed, Great Britain would maneuver the Republic of Texas into emancipating its slaves, forecasting a dangerous destabilizing influence on southwestern slaveholding states. The pamphlet characterized abolitionists as traitors who conspired with the British to overthrow the United States.[93][94]

A variation of the Tyler's "diffusion" theory, it played on economic fears in a period when slave-based staple crop markets had not yet recovered from the Panic of 1837. The Texas "escape route" conceived by Walker promised to increase demand for slaves in fertile cotton-growing regions of Texas, as well as the monetary value of slaves. Cash-poor plantation owners in the older eastern South were promised a market for surplus slaves at a profit.[95] Texas annexation, wrote Walker, would eliminate all these dangers and "fortify the whole Union."[96]

Walker's pamphlet brought forth strident demands for Texas from pro-slavery expansionists in the South; in the North, it allowed anti-slavery expansionists to embrace Texas without appearing to be aligned with pro-slavery extremists.[97] His assumptions and analysis "shaped and framed the debates on annexation but his premises went largely unchallenged among the press and public.[98]

Tyler-Texas treaty and the election of 1844

| Treaty of annexation concluded between the United States of America and the Republic of Texas | |

|---|---|

| Drafted | February 27, 1844 |

| Signed | April 12, 1844 |

| Location | Washington |

| Effective | Not ratified |

| Signatories | |

| Consent refused by the U.S. Senate (Senate Journal, June 8, 1844, volume 430, pp. 436–438). | |

The Tyler-Texas treaty, signed on April 12, 1844, was framed to induct Texas into the Union as a territory, following constitutional protocols. To wit, Texas would cede all its public lands to the United States, and the federal government would assume all its bonded debt, up to $10 million. The boundaries of the Texas territory were left unspecified.[99] Four new states could ultimately be carved from the former republic – three of them likely to become slave states.[100] Any allusion to slavery was omitted from the document so as not to antagonize anti-slavery sentiments during Senate debates, but it provided for the "preservation of all [Texas] property as secured in our domestic institutions."[101]

Upon the signing of the treaty, Tyler complied with the Texans' demand for military and naval protection, deploying troops to Fort Jesup in Louisiana and a fleet of warships to the Gulf of Mexico.[102] In case the Senate failed to pass the treaty, Tyler promised the Texas diplomats that he would officially exhort both houses of Congress to establish Texas as a state of the Union upon provisions authorized in the Constitution.[103] Tyler's cabinet was split on the administration's handling of the Texas agreement. Secretary of War William Wilkins praised the terms of annexation publicly, touting the economic and geostrategic benefits with relation to Great Britain.[104] Secretary of the Treasury John C. Spencer was alarmed at the constitutional implications of Tyler's application of military force without congressional approval, a violation of the separation of powers. Refusing to transfer contingency funds for the naval mobilization, he resigned.[105]

Tyler submitted his treaty for annexation to the Senate, delivered April 22, 1844, where a two-thirds majority was required for ratification.[106][107] Secretary of State Calhoun (assuming his post March 29, 1844)[108] had sent a letter to British minister Richard Packenham denouncing British anti-slavery interference in Texas. He included the Packenham Letter with the Tyler bill, intending to create a sense of crisis in Southern Democrats.[109] In it, he characterized slavery as a social blessing and the acquisition of Texas as an emergency measure necessary to safeguard the "peculiar institution" in the United States.[110] In doing so, Tyler and Calhoun sought to unite the South in a crusade that would present the North with an ultimatum: support Texas annexation or lose the South.[111]

Tyler and the Polk presidential nomination

President Tyler expected that his treaty would be debated secretly in Senate executive session.[112] However, less than a week after debates opened, the treaty, its associated internal correspondence, and the Packenham letter were leaked to the public. The nature of the Tyler-Texas negotiations caused a national outcry, in that "the documents appeared to verify that the sole objective of Texas annexation was the preservation of slavery."[113] A mobilization of anti-annexation forces in the North strengthened both major parties' hostility toward Tyler's agenda. The leading presidential hopefuls of both parties, Democrat Martin Van Buren and Whig Henry Clay, publicly denounced the treaty.[114] Texas annexation and the reoccupation of Oregon territory emerged as the central issues in the 1844 general election.[115]

In response, Tyler, already ejected from the Whig party, quickly began to organize a third party in hopes of inducing the Democrats to embrace a pro-expansionist platform.[116] By running as a third-party candidate, Tyler threatened to siphon off pro-annexation Democratic voters; Democratic party disunity would mean the election of Henry Clay, a staunchly anti-Texas Whig.[117] Pro-annexation delegates among southern Democrats, with assistance from a number of northern delegates, blocked anti-expansion candidate Martin Van Buren at the convention, which instead nominated the pro-expansion champion of Manifest Destiny, James K. Polk of Tennessee. Polk unified his party under the banner of Texas and Oregon acquisition.[118]

In August 1844, in the midst of the campaign, Tyler withdrew from the race. The Democratic Party was by then unequivocally committed to Texas annexation, and Tyler, assured by Polk's envoys that as president he would effect Texas annexation, urged his supporters to vote Democratic.[119] Polk narrowly defeated Whig Henry Clay in the November election.[120] The victorious Democrats were poised to acquire Texas under President-elect Polk's doctrine of Manifest Destiny,[121] rather than on the pro-slavery agenda of Tyler and Calhoun.[122]

Congressional debate over annexation

Tyler-Texas Treaty defeat in the Senate

As a treaty document with a foreign nation, the Tyler-Texas annexation treaty required the support of a two-thirds majority in the Senate for passage. But in fact, when the Senate voted on the measure on June 8, 1844, fully two-thirds voted against the treaty (16–35).[123] The vote went largely along party lines: Whigs had opposed it almost unanimously (1–27), while Democrats split, but voted overwhelmingly in favor (15–8).[124] The election campaign had hardened partisan positions on Texas among Democrats.[125] Tyler had anticipated that the measure would fail, largely because of the divisive effects of Secretary Calhoun's Packenham letter.[126] Undeterred, he formally asked the House of Representatives to consider other constitutional means to authorize passage of the treaty. Congress adjourned before debating the matter.[127]

Reintroduction as a joint resolution

The same Senate that had rejected the Tyler–Calhoun treaty by a margin of 2:1 in June 1844[128] reassembled in December 1844 in a short lame-duck session.[129] (Though pro-annexation Democrats had made gains in the fall elections, those legislators – the 29th Congress – would not assume office until March 1845.)[130] Lame-duck President Tyler, still trying to annex Texas in the final months of his administration, wished to avoid another overwhelming Senate rejection of his treaty.[131] In his annual address to Congress on December 4, he declared the Polk victory a mandate for Texas annexation[132] and proposed that Congress adopt a joint resolution procedure by which simple majorities in each house could secure ratification for the Tyler treaty.[133] This method would avoid the constitutional requirement of a two-thirds majority in the Senate.[134] Bringing the House of Representatives into the equation boded well for Texas annexation, as the pro-annexation Democratic Party possessed nearly a 2:1 majority in that chamber.[135][136]

By resubmitting the discredited treaty through a House-sponsored bill, the Tyler administration reignited sectional hostilities over Texas admission.[137] Both northern Democratic and southern Whig Congressmen had been bewildered by local political agitation in their home states during the 1844 presidential campaigns.[138] Now, northern Democrats found themselves vulnerable to charges of appeasement of their southern wing if they capitulated to Tyler's slavery expansion provisions. On the other hand, Manifest Destiny enthusiasm in the north placed politicians under pressure to admit Texas immediately to the Union.[139]

Constitutional objections were raised in House debates as to whether both houses of Congress could constitutionally authorize admission of territories, rather than states. Moreover, if the Republic of Texas, a nation in its own right, were admitted as a state, its territorial boundaries, property relations (including slave property), debts and public lands would require a Senate-ratified treaty.[140] Democrats were particularly uneasy about burdening the United States with $10 million in Texas debt, resenting the deluge of speculators, who had bought Texas bonds cheap and now lobbied Congress for the Texas House bill.[141] House Democrats, at an impasse, relinquished the legislative initiative to the southern Whigs.[142]

Brown–Foster House amendment

Anti-Texas Whig legislators had lost more than the White House in the general election of 1844. In the southern states of Tennessee and Georgia, Whig strongholds in the 1840 general election, voter support dropped precipitously over the pro-annexation excitement in the Deep South—and Clay lost every Deep South state to Polk.[143] Northern Whigs' uncompromising hostility to slavery expansion increasingly characterized the party, and southern members, by association, had suffered from charges of being "soft on Texas, therefore soft on slavery" by Southern Democrats.[144] Facing congressional and gubernatorial races in 1845 in their home states, a number of Southern Whigs sought to erase that impression with respect to the Tyler-Texas bill.[145][146]

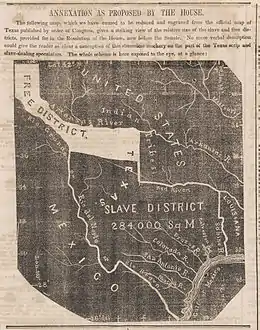

Southern Whigs in the Congress, including Representative Milton Brown and Senator Ephraim Foster, both of Tennessee, and Representative Alexander Stephens of Georgia[147] collaborated to introduce a House amendment on January 13, 1845,[148] that was designed to enhance slaveowner gains in Texas beyond those offered by the Democratic-sponsored Tyler-Calhoun treaty bill.[149] The legislation proposed to recognize Texas as a slave state which would retain all its vast public lands, as well as its bonded debt accrued since 1836. Furthermore, the Brown amendment would delegate to the U.S. government responsibility for negotiating the disputed Texas-Mexico boundary. The issue was a critical one, as the size of Texas would be immensely increased if the international border were set at the Rio Grande River, with its headwaters in the Rocky Mountains, rather than the traditionally recognized boundary at the Nueces River, 100 miles to the north.[150] While the Tyler-Calhoun treaty provided for the organization of a total of four states from the Texas lands – three likely to qualify as slave states – Brown's plan would permit Texas state lawmakers to configure a total of five states from its western region, with those south of the 36°30’ Missouri Compromise line pre-authorized to permit slavery upon statehood, if Texas designated them as such.[151]

Politically, the Brown amendment was designed to portray Southern Whigs as "even more ardent champions of slavery and the South, than southern Democrats."[152] The bill also served to distinguish them from their northern Whig colleagues who cast the controversy, as Calhoun did, in strictly pro- versus anti-slavery terms.[153] While almost all Northern Whigs spurned Brown's amendment, the Democrats quickly co-opted the legislation, providing the votes necessary to attach the proviso to Tyler's joint resolution, by a 118–101 vote.[154] Southern Democrats supported the bill almost unanimously (59–1), while Northern Democrats split strongly in favor (50–30). Eight of eighteen Southern Whigs cast their votes in favor. Northern Whigs unanimously rejected it.[155] The House proceeded to approve the amended Texas treaty 120–98 on January 25, 1845.[156] The vote in the House had been one in which party affiliation prevailed over sectional allegiance.[157] The bill was forwarded the same day to the Senate for debate.

Benton Senate compromise

By early February 1845, when the Senate began to debate the Brown-amended Tyler treaty, its passage seemed unlikely, as support was "perishing".[158] The partisan alignments in the Senate were near parity, 28–24, slightly in favor of the Whigs.[159] The Senate Democrats would require undivided support among their colleagues, and three or more Whigs who would be willing to cross party lines to pass the House-amended treaty. The fact that Senator Foster had drafted the House amendment under consideration improved prospects of Senate passage.[160]

Anti-annexation Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri had been the only Southern Democrat to vote against the Tyler-Texas measure in June 1844.[161][162] His original proposal for an annexed Texas had embodied a national compromise, whereby Texas would be divided in two, half slave-soil and half free-soil.[163] As pro-annexation sentiment grew in his home state, Benton retreated from this compromise offer.[164] By February 5, 1845, in the early debates on the Brown-amended House bill, he advanced an alternative resolution that, unlike the Brown scenario, made no reference whatsoever to the ultimate free-slave apportionment of an annexed Texas and simply called for five bipartisan commissioners to resolve border disputes with Texas and Mexico and set conditions for the Lone Star Republic's acquisition by the United States.[165]

The Benton proposal was intended to calm northern anti-slavery Democrats (who wished to eliminate the Tyler-Calhoun treaty altogether, as it had been negotiated on behalf of the slavery expansionists), and allow the decision to devolve upon the soon-to-be-inaugurated Democratic President-elect James K. Polk.[166] President-elect Polk had expressed his ardent wish that Texas annexation should be accomplished before he entered Washington in advance of his inauguration on March 4, 1845, the same day Congress would end its session.[167] With his arrival in the capital, he discovered the Benton and Brown factions in the Senate "paralyzed" over the Texas annexation legislation.[168] On the advice of his soon-to-be Secretary of the Treasury Robert J. Walker, Polk urged Senate Democrats to unite under a dual resolution that would include both the Benton and Brown versions of annexation, leaving enactment of the legislation to Polk's discretion when he took office.[169] In private and separate talks with supporters of both the Brown and Benton plans, Polk left each side with the "impression he would administer their [respective] policy. Polk meant what he said to Southerners and meant to appear friendly to the Van Burenite faction."[170] Polk's handling of the matter had the effect of uniting Senate northern Democrats in favor of the dual alternative treaty bill.[171]

On February 27, 1845, less than a week before Polk's inauguration, the Senate voted 27–25 to admit Texas, based on the Tyler protocols of simple majority passage. All twenty-four Democrats voted for the measure, joined by three southern Whigs.[172] Benton and his allies were assured that Polk would act to establish the eastern portion of Texas as a slave state; the western section was to remain unorganized territory, not committed to slavery. On this understanding, the northern Democrats had conceded their votes for the dichotomous bill.[173] The next day, in an almost strict party line vote, the Benton-Milton measure was passed in the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives.[174] President Tyler signed the bill the following day, March 1, 1845 (Joint Resolution for annexing Texas to the United States, J.Res. 8, enacted March 1, 1845, 5 Stat. 797).[175]

Annexation and admittance

Senate and House legislators who had favored Benton's renegotiated version of the Texas annexation bill had been assured that President Tyler would sign the joint house measure, but leave its implementation to the incoming Polk administration.[176] But, during his last full day in office, President Tyler, with the urging of his Secretary of State Calhoun,[177] decided to act decisively to improve the odds for the immediate annexation of Texas. On March 3, 1845, with his cabinet's assent, he dispatched an offer of annexation to the Republic of Texas by courier, exclusively under the terms of the Brown–Foster option of the joint house measure.[178] Secretary Calhoun apprised President-elect Polk of the action, who demurred without comment.[179][180] Tyler justified his preemptive move on the grounds that Polk was likely to come under pressure to abandon immediate annexation and reopen negotiations under the Benton alternative.[181]

When President Polk took office on (at noon EST) March 4, he was in a position to recall Tyler's dispatch to Texas and reverse his decision. On March 10, after conferring with his cabinet, Polk upheld Tyler's action and allowed the courier to proceed to Texas with the offer of immediate annexation.[182] The only modification was to exhort Texans to accept the annexation terms unconditionally.[183] Polk's decision was based on his concern that a protracted negotiation by US commissioners would expose annexation efforts to foreign intrigue and interference.[184] While Polk kept his annexation endeavors confidential, Senators passed a resolution requesting formal disclosure of the administration's Texas policy. Polk stalled, and when the Senate special session had adjourned on March 20, 1845, no names for US commissioners to Texas had been submitted by him. Polk denied charges from Senator Benton that he had misled Benton on his intention to support the new negotiations option, declaring "if any such pledges were made, it was in a total misconception of what I said or meant."[185]

On May 5, 1845, Texas President Jones called for a convention on July 4, 1845, to consider the annexation and a constitution.[186] On June 23, the Texan Congress accepted the US Congress's joint resolution of March 1, 1845, annexing Texas to the United States, and consented to the convention.[187] On July 4, the Texas convention debated the annexation offer and almost unanimously passed an ordinance assenting to it.[188] The convention remained in session through August 28, and adopted the Constitution of Texas on August 27, 1845.[189] The citizens of Texas approved the annexation ordinance and new constitution on October 13, 1845.

President Polk signed the legislation making the former Lone Star Republic a state of the Union on December 29, 1845 (Joint Resolution for the admission of the state of Texas into the Union, J.Res. 1, enacted December 29, 1845, 9 Stat. 108).[190] Texas symbolically relinquished its sovereignty to the United States at the inauguration of Governor James Henderson on February 19, 1846.[191]

Border disputes

Neither the joint resolution nor the ordinance of annexation contain language specifying the boundaries of Texas, and only refer in general terms to "the territory properly included within, and rightfully belonging to the Republic of Texas", and state that the new State of Texas is to be formed "subject to the adjustment by this [U.S.] government of all questions of boundary that may arise with other governments." According to George Lockhart Rives, "That treaty had been expressly so framed as to leave the boundaries of Texas undefined, and the joint resolution of the following winter was drawn in the same manner. It was hoped that this might open the way to a negotiation, in the course of which the whole subject of the boundaries of Mexico, from the Gulf to the Pacific, might be reconsidered, but these hopes came to nothing."[192]

There was an ongoing border dispute between the Republic of Texas and Mexico prior to annexation. Texas claimed the Rio Grande as its border based on the Treaties of Velasco, while Mexico maintained that it was the Nueces River and did not recognize Texan independence. In November 1845, President James K. Polk sent John Slidell, a secret representative, to Mexico City with a monetary offer to the Mexican government for the disputed land and other Mexican territories. Mexico was not inclined nor able to negotiate because of instability in its government[193] and popular nationalistic sentiment against such a sale.[194] Slidell returned to the United States, and Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to garrison the southern border of Texas, as defined by the former Republic, in 1846. Taylor moved into Texas, ignoring Mexican demands to withdraw, and marched as far south as the Rio Grande, where he began to build a fort near the river's mouth on the Gulf of Mexico. The Mexican government regarded this action as a violation of its sovereignty, and immediately prepared for war. Following a United States victory and the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico ceded its claims to Texas and the Rio Grande border was accepted by both nations.

Joint resolution precedent and legacy: Hawaii

.jpg.webp)

The formal controversy over the legality of the annexation of Texas stems from the fact that Congress approved the annexation of Texas as a state, rather than a territory, with simple majorities in each house, instead of annexing the land by Senate treaty, as was done with Native American lands. Tyler's extralegal joint resolution maneuver in 1844 exceeded strict constructionist precepts, but was passed by Congress in 1845 as part of a compromise bill. The success of the joint house Texas annexation set a precedent that would be applied to Hawaii's annexation in 1897.[195]

Republican President Benjamin Harrison (1889–1893) attempted, in 1893, to annex Hawaii through a Senate treaty. When this failed, he was asked to consider the Tyler joint house precedent; he declined. Democratic President Grover Cleveland (1893–1897) did not pursue the annexation of Hawaii. When President William McKinley took office in 1897, he quickly revived expectations among territorial expansionists when he resubmitted legislation to acquire Hawaii. When the two-thirds Senate support was not forthcoming, committees in the House and Senate explicitly invoked the Tyler precedent for the joint house resolution, which was successfully applied to approve the annexation of Hawaii in July 1898.[196]

Notes

- Meacham, 2008, p. 315

- Merry, 2009, pp. 69–70: The Texas annexation issue "emerged atop a history stretching back to 1803 and the Thomas Jefferson's celebrated purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France. One problem was that the precise boundaries of the vast lands were unknown."

Crapol, 2006, p. 176: "... many people thought that all or at least part of Texas was included in the bargain."

Remini, 2002, p. 55: "When the French sold Louisiana to the United States the western and northern boundaries were not defined and some Americans claimed that Texas was included in the purchase and they wanted it occupied." - Dangerfield, 1952, p. 129: "... Adams took up the [Louisiana] negotiations in December 1817."

- Merry, 2009, p. 70: "Spain and the United States found themselves in the dispute over Louisiana's western border and the extent to which Jefferson's purchase included the portion of Texas." And "[I]n 1819, the matter was incorporated into the two countries' efforts to settle the status of Florida."

Dangerfield, 1952, pp. 128–129: "The cession of Florida was, of course, not the only bargaining point at the disposal of [Onis] in his attempt to prevent the United States from recognizing ... Spanish revolutionaries in South America. He was also ready to discuss the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase in their relation to the Empire of Spain. - Crapol, 2006, p. 176: "... the Adams-Onis Treaty ... also known as the Florida treaty ..."

- Dangerfield, 1952, p. 152: "On February 22 [1819], the great Transcontinental Treaty was signed and sealed."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 176: "... the Sabine River ... today is the boundary between [the states of] Louisiana and Texas." P. 176: The US claim to Texas" was legally extinguished ..."

- Dangerfield, 1952, p. 156:"It was by no means a perfect Treaty – by excluding Texas [from US possession], it bequeathed to the United States a legacy of trouble and war – but was certainly a great Treaty."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 176: "Among diehard expansionists unwilling to give up hope of getting Texas at a future date was Thomas Jefferson. He assured his friend President James Monroe that, when acquired, Texas would become "the richest State of our Union, without any exception."

Merry, 2009, p. 70: "[E]stablishing [Texas] west of the Sabine ... enraged many US expansionists" and "[a]nger over the treaty would linger for decades." - Brown, 1966, p.24: The "architects of Southern power [objected to] the so-called Thomas Proviso, amending the Missouri bill to draw the ill-fated 36°30' line across the Louisiana Purchase, prohibiting slavery in the territory to the north, giving up the lion's share to freedom."

- Holt, 2004, p. 6: "In short, in 1820, a majority of southern congressmen accepted congressional prohibition of slavery from almost all of the western territories."

- Brown, 1966, pp. 25–26: "In fact, the vote on the [Thomas] Proviso illuminated an important division in Southern sentiment. Thirty-seven slave state congressmen opposed it, white thirty-nine voted for it ..." a harbinger that the opposition would "in due time rectify the Thomas Proviso."

- Brown, 1966, p. 25: "As the [Missouri] debates thundered to their climax, Ritchie in two separate editorials predicted the if the Proviso passed, the South must in due time have Texas".

- Freehling, 1991, p. 152: "The Thomas plan angered some Southerners. They denounced the unequal division of turf and constitutional precedent."

- Brown, 1966, p. 28: "In 1823–1824 some Southerners suspected that an attempt by Secretary of State Adams to conclude a slave trade convention with Great Britain was an attempt to reap the benefit of Northern anti-slavery sentiments; and some, notably John Floyd of Virginia, sought to turn the tables on Adams by attacking him for allegedly ceding Texas to Spain in the Florida treaty, thus ceding what Floyd called "two slaveholding states" and costing "the Southern interest" four Senators."

- Crapol, 2006, pp. 37–38: Tyler "believed in a theory of'diffusion' as a way to end slavery gradually and peacefully ... so as to "thin out and diffuse the slave population and, with fewer blacks in some of the older slave states of the upper South, it might become politically feasible to abolish slavery in states like Virginia" ... and "Tyler voted against proposals that restricted slavery in Missouri or any other portion of the remaining territory of the Louisiana Purchase."

- Freehling, 1991, p. 151: "The Southerner [John Tyler] who best defended diffusion during the Missouri Crisis would become a key actor in the Texas [annexation] epic.", p. 195: "... the diffusion argument had emerged in the Missouri Controversy of the 1820s and would remain in the Texas Controversy of the 1840s."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 206: Pro-Texas arguments made by Senator Walker in 1843 were "remarkably similar to [Tyler's] diffusion theory he earlier had formulated at the time of the Missouri controversy."

- Freehling, 1991, p. 365

- Crapol, 2006, p. 176: "In fact, Mexican sovereignty [over Texas] was openly acknowledged" by the Adams and Jackson administrations, both of whom "tried to purchase all or part of Texas from the Mexicans."

Merk, 1978, p. 270: "Mexican fears were ... aroused because of the persistence with which the United States government tried to buy Texas."

Merry, 2009, p. "Jackson ... had sought to purchase the province from Mexico before Texas independence." - Crapol, 2006, p. 176:"... Texans, mostly Americans who had emigrated to the province ..."

- Merk, 1978, p. 270: "The Anglo-Americans who went to Texas were attracted by the prospect of beautiful agricultural lands virtually free.", Meacham, 2008, p. 315, Ray Allen Billington,The Far Western Frontier, 1830–1860 (New York: Harper & Row, 1956), p. 116.

- Freehling, 1991, pp. 368–369

Merry, 2009, p. 70: "Stephen [Austin] arrived in 1821 and established sway over 100,000 acres of [Mexican land grants] with the assistance of Tejano elites who sought to partner in his enterprise." - Malone, 1960, p. 543: "Stephen F. Austin ... the chief promoter of colonization [in Texas]" and "... the basic reason for the migration of Americans" was the "liberal colonization law under which a league [7 square miles] of land was made available to each married settler ... for less than $200."

- Freehling, 1991, p. 365: "The Mexican government ... considered southwestern [US] entrepreneurs the most likely migrants" and invited them "to bring along their despotic alternative to Mexican economic peonage, black slavery ..."

- Malone, 1960, p. 543: "The vast distances in Texas, the premium that space paid to the individualism" contributed to "the disrespect of settlers for Mexican authority" and "Private violence was common ... and public violence was endemic."

- Merk, 1978, p. 270: "The Texan revolt was the result primarily of the initial Mexican error of admitting into the rich prairies of Texas a race of aggressive and unruly American frontiersmen who were contemptuous of Mexico and Mexican authority."

- Merk, 1978, p. 270: Mexican authorities feared that "... Texas was developing into an American state ...", Malone, 1960, p. 544: "... the Colonization Law of 1830 ... forbade further American migration to Texas."

- Freehling, 1991, p.545: "Neglected sovereign power [in Texas] was creating a vacuum" and Mexico "accordingly emancipated slaves" nationwide on "September 15, 1829"

- Varon, 2008, p. 127: "Texans had earned the reputation as defenders of slavery – they had vehemently protested efforts by successive Mexican administrations to restrict and gradually dismantle the institution, winning concessions such as the 1828 decree that allowed Texans to register their slaves, in name only, as 'indentured servants'".

Malone, 1960, p. 544 - Freehling, 1991, p. 365: "... On April 21, 1836, General Sam Houston ambushed Santa Anna at San Jacinto ..."

- Malone, 1960, p. 544: "... the Texas Declaration of Independence of March 2, 1836 ..."

- Freehling, 1991, p. 365, Merk, 1978, pp. 275–276

- Freehling, 1991, p. 365

- Merry, 2009, p.71: "... an official state of war existed between the two entities, although it never erupted into full scale fighting."

- Freehling, 1991, p. 365: "... prospective American settlers [did not] have to be told that life and property were safer in the United States than in Texas ..." and slave-owners "considered slave property particularly unsafe across the border."

- Andrew J. Torget (2015). Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800–1850. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1469624242.

- Freehling, 1991, p. 365: "Imminent war hung heavily over the Texas Republic's prospects": though "Few Texans feared that Mexico might win such a war," it would disrupt Texas's economy and society, making "slave property particularly unsafe." P. 367: "Texas's population shortage victimized more than the economy. Slim populations made for low tax revenue, a large national debt, and an undermanned army."

- Finkelman, 2011, pp. 29–30: "As long as Texas remained an independent republic, the Mexican government had no strong incentive to actively assert its claim of ownership. In the years since declaring independence, Texas had hardly prospered; its government was weak, its treasury was empty, and its debt was mounting every year. Mexico knew that eventually the independent government would fail."

- Malone, 1960, p. 545: Texans "avidly desired annexation by the United States.", Crapol, 2006, p. 176: Texans "overwhelmingly supported immediate annexation by the United States."

- Freehling, 1991, p. 367: "President Jackson was indeed a partisan of Texas annexation ... He recognized the independence of Texas ... on the last day of his administration ..." and "later claimed his greatest mistake was in failing to celebrate annexation as well as recognition."

- Freehling, 1991, p. 367: "On the last day of his administration ... he recognized the independence of Texas."

- Malone, 1960, p. 545: Jackson maintained "correct neutrality" towards Texas independence., Crapol, 2006, p. 53: "Unwilling to jeopardize the election of Van Buren ... Jackson had not sought immediate annexation ... although recognition was granted in early 1837 after Van Buren was safely elected ..." Merk, 1978, p. 279

- Crapol, 2006, p. 53: "... a widespread northern uneasiness that taking Texas would add a number of slave states and upset the congressional balance between North and South." Malone, 1960, p. 545: "... the American Anti-Slavery Society" charged that "Texas would make half a dozen [slave] states ... and annexation would give the South dominance in the Union." Merk, 1978, p. 279: "... it would precipitate a clash over the extension of slavery in the United States."

- Merry, 2009, p. 71: Van Buren "particularly feared any sectional flare-ups over slavery that would ensue from an annexation effort."

- Freehling, 1991, pp. 367–368: Van Buren "considered Texas potentially poisonous to American Union", and Whigs "could generate mammoth political capital out of any war with Mexico which was fought to gain a huge slaveholding republic and still more land for the Slavepower." "Van Buren would not even allow the Texas [minister to the US] to present an annexation proposal ... until months after his inauguration, then swiftly turned it down."

Crapol, 2006, p. 177: "... in August 1837, the Texans officially requested annexation, but Van Buren, fearing an anti-slavery backlash and domestic turmoil, rebuffed them.", Malone, 1960, p. 545: Van Buren "facing a financial crisis [Panic of 1837] ... did not want to add to his diplomatic and political difficulties, rebuffed it." Merk, 1978, pp. 279–280 - Richard Bruce Winders, Crisis in the Southwest: The United States, Mexico, and the Struggle over Texas (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002), p. 41.

Malone, 1960, p. 545: "In 1838, an annexation resolution that was presented in the Senate by a South Carolinian was voted down, while another that had been similarly introduced in the House was smothered by three-weeks filibustering speech by John Quincy Adams ... soon after the Texans withdrew their offer and turned their eyes toward Great Britain."

Crapol, 2006, p. 177: "Texas withdrew their [annexation] offer in October 1838." - Crapol, 2006, p. 177: "[A series of failures to annex Texas] was more of less where matters [on annexation] stood when John Tyler entered the White House."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 10: "Three days after taking the symbolic oath-taking [April 6, 1841], John Tyler issued an inaugural address to further buttress the legitimacy of his presidency."

- Freehling, 1991, p. 364: "Tyler vetoed [the Whigs] banking bill" and "again ... vetoed [it]." The Whigs congressional caucus "... excommunicated the President from the party ..." Tyler recruited "extreme States' Rights Whigs" to fill cabinet posts ..." p. 357: As the "first and last States' Rights Whig President" he would form a "coalition uncompromisingly for states' rights.", Merk, 1978, p. 280: Tyler ..."a president without a party ... turned to foreign affairs, where executive authority was greater ..."

- Merk, 1978, pp. 280–281: "... opportunities were open in foreign affairs – the annexation of Texas and a settlement of the Oregon dispute with England. The acquisition of Texas also beckoned.", Crapol, 2006, pp. 24–25: "John Tyler recognized, as his fellow Virginians Jefferson and Monroe ... that expansion was the republican key to preserving the delicate balance between national and state power" and"... bringing Texas into the Union headed Tyler's acquisitive agenda." P. 177: Tyler's "Madisonian formula, [where] empire and liberty became inseparable in order to sustain the incongruity of a slaveholding republic."

- Merk, 1978, p. 281: "The temper of the period was expansionist and its tide might carry the statesman [Tyler] riding it into a term of his own in the White House."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 177

- Crapol, 2006, p. 178:"Despite being preoccupied by these more urgent diplomatic initiatives, the president kept Texas uppermost on his long-term expansionist agenda."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 180

- Merk, 1978, p. 281: "The letter was recognized at once as a major pronouncement on the Texas issue." "And [Gilmer] was a believer in the new creed of the beneficence of slavery and also in the doctrine of Manifest Destiny.", Crapol, 2006, pp. 180–181

- Merk, 1978, p. 281: "[Daniel Webster's] presence in the Cabinet had become an embarrassment to Tyler as the annexation issue emerged." And "[Upshur] ... a devotee of strict construction and ... the beneficence of Negro slavery." And "[Upshur's] appointment was an omen of the coming drive for the annexation of Texas."

Crapol, 2006, p. 194: Upshur agreed with Tyler "that bringing the Lone Star Republic in the Union as a slave state should be the administration's number one diplomatic priority."

Freehling, 1991, p. 364: "... his Secretary of State [Upshur] could suggest a foreign policy [on Texas] fit to reassert executive authority and build a presidential party." - Crapol, 2006, p. 197: Upshur's letter was an "effort to rally the American public in opposition to British machinations in Texas ..."

Freehling, 1991, pp. 399–400: "... American Ambassador to London Edward Everett told Aberdeen of the Tyler-Upshur fury about English 'earnest pressing'... [encouraging] a Texas-Mexico emancipation rapprochement." - Crapol, 2006, p. 197: Upshur's letter "a breach of diplomatic protocol ..."

- Varon, 2008, p. 166: "In 1841, Tyler had dispatched Green as an emissary to London, to move stealthily in diplomatic circles in search of 'proof' that England had designs on Texas

Merk, 1978, p. 281–282: "The subjects of negotiation" included "adjustments of territorial issues ... of the Oregon dispute ..." and p. 282: "Green busied himself, in collaboration with ... Lewis Cass ... to defeat ratification of the ... Quintuple Treaty to suppress the maritime slave trade" which France approved. - Merk, 1978, p. 282: "... the discovery of a British 'plot' to abolitionize Texas ... promised a government guarantee of interest on a loan to Texas ... devoted to abolitionizing Texas."

- Merk, 1978, p. 284: "Everett's report ... constituted a negation of the Duff Green letter and the charges Upshur wished to fasten to the British ministry ..." and expressed the opinion that Britain "was less committed to antislavery causes than had been its predecessor, or the British public."

Merry, 2009, p. 74: "The British minister to Mexico ... Charles Elliot, had actually formulated a plan for extensive British loans to Texas in exchange for abolition and a free trade policy between the two countries. His clear aim was to detach Texas completely from United States influence ... Lord Aberdeen, British foreign secretary, on three occasions sought to assure America that Britain harbored no such ambitions ... But ... Duff Green, Tyler's man in London, chose to ignore Aberdeen's assurances. His motive is discernible in his private warnings to his friend Calhoun that, without the Texas issue, the Calhoun forces would be over whelmed by the presidential momentum of their rival Van Buren." - Merry, 2009, p. 72: Duff Green's claims of a British loan plot, "though false ... was highly incendiary throughout the South – and also in the White House, occupied by a Virginia slaveholder and longtime Calhoun confidant."

- Merk, 1978, p. 282: "... the tidings from Green ... also went to Calhoun ... the mentor of southern extremists." And "[Calhoun] ... believed the "British were determined to abolish slavery ... throughout the continent ... a disaster," and he would "lead a campaign of propaganda on behalf of annexation."

- Merk, 1978, pp. 282–283: "On August 18, 1843 ... Lord Aberdeen was questioned in the House of Lords as to what the [British] government was doing regarding the trade in slaves to Texas and ... war between Mexico and Texas" he said that "an armistice had been arranged ..." and that "the British government hoped to see slavery abolished in Texas and everywhere else in the world" and to see "peace between Mexico and Texas."

- Freehling, 1991, p. 382

- Crapol, 2006, p. 195

Merk, 1991, p. 283: "Prompt action was necessary to meet the threat. Tyler at once authorized Upshur to open negotiations with the Texas government ... on September 18, 1843 ..." and "word passed to Isaac Van Zandt ..." - Wilentz, 2008, p. 561

- Finkelman, 2011, p. 30: "By 1843, the government in Austin [Texas] was negotiating with Great Britain to intercede with Mexico to recognize Texas independence."

Freehling, 1991, pp. 370–371 - Finkelman, 2011, p. 30: "It is hard to imagine that the slaveholding republic would have actually consented to any significant British influence in Texas because Britain was deeply hostile to slavery and had abolished it everywhere in its empire."

Malone, 1960, p. 545: "Things were not going well in Texas ... in 1843 ... and [Sam Houston] had little choice but to flirt with the British for their backing." - Freehling, 1991, p. 369

- Freehling, 1991, p. 369: "An American presidential election loomed ... [both parties] were determined to keep annexation out of the canvass."

- Freehling, 1991, p. 396: "... Texas could govern themselves if they conceded Mexicans' theoretical sovereignty" or Britain's minister to Mexico Doyle "[could] suggest that Mexico grant Texas independence if Texas should make [its] blacks independent."

- Merk, 1978, p. 284: "Van Zandt ... favored annexation ..." but had been instructed "to take no action on the matter ... and declined Upshur's invitation to enter" into talks. "The Texas government had no fear of British interference with its form of labor ... never so much as alluded to by British representatives in Texas." "What Texans really feared was reopening by Mexico of hostilities in the event of attempted annexation to the United States and a resulting withdrawal of [Britain]" as mediator.

- Merk, 1978, p. 285: Upshur wrote Houston "earlier American failures ... had been due to a misunderstanding of the issue." "Annexation was now favored even in the North to a great extent ..." and it would be feasible to win "a clear constitutional majority" in "the Senate for ratification."

- Merk, 1978, p. 285: "The question [of American military commitment] went to the heart of Texan hesitation about entering into American negotiation, and also at the heart of the American constitutional principle of separation of powers."

- Merk, 1978, p. 285: "Houston ... reversed his stand ... and recommended to [Texas] Congress the opening of an annexation negotiation."

Crapol, 2006, p. 196: "After five months of hard bargaining, [Upshur] convinced enough members of Sam Houston's government of the sincerity of the Tyler administration's overtures and cajoled them into accepting American guarantees of protection and quick action." - Crapol, 2006, p. 198: "... Almonte bluntly warned [Upshur], Mexico would sever diplomatic relations and immediately declare war."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 199: Uphsur denied "any knowledge of US-Texas negotiations to Minister Almonte ..."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 203: "... Upshur ... inform[ed] Texas officials that at least forty of fifty-two senators were solid for ratification ..."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 199: "It was the prudent thing to do if he hoped to retain the trust of the Texans and keep them at the negotiating table."

- Crapol, 2006, pp. 200–201

- Crapol, 2006, p. 207

- Crapol, 2006, p. 209: "The deaths of Upshur and Gilmer deprived [Tyler] of two of his best people and the most important architects of the administration's annexation policy ... the political landscape had been rocked."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 211: Calhoun "ranked with Daniel Webster and Henry Clay as America's leading political icons of the early republic."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 211: "... Tyler momentarily balked at the idea of appointing Calhoun as secretary of state because the South Carolinian might adversely polarize public opinion on the Texas question ... It was a decision he later came to regret."

- Merk, 1978, pp. 285–286: Calhoun "was known to be eager for Texas ... [and] had been Upshur's counselor on the issue."

Merry, 2009, p. 67: Calhoun's appointment as Secretary of State was "guaranteed to generate controversy and disruption" on the Texas issue. - Freehling, 1991, p. 418: "Once [Sam] Houston agreed to negotiate with Upshur, Walker authored an enormously influential pro-Texas pamphlet."

Crapol, 2006, p. 204: "... Senator Walker published a lengthy pro-annexation letter" in a leading newspaper, "... a message to the American people outlining the manifold reasons why the United States should annex Texas," and "millions of copies were circulated" in pamphlet form.

Merry, 2009, p. 85: Walker "had published a long pro-annexation treatise that had helped galvanize the issue and get [Texas annexation] into the public consciousness." - Crapol, 2006, p. 22: "... the Monroe Doctrine [was] a restatement of the Madisonian/Jeffersonian faith in territorial expansion ..." also see p. 205.

- Freehling, 1991, p. 418: Walker asserted that "an annexed Texas, instead of helping to perpetuate slavery, would beneficially diffuse blacks away, first from the oldest [US] South, eventually from an emancipated North America." And pp. 419–420: The country would be emptied of blacks, 'not by abolition ... but slowly and gradually ...'

Wilentz, 2008, p. 563: Walker "argued that annexation would lead to a dispersal of slave populations through the West and into Latin America, hasten slavery's demise" and create "an all-white United States – a rehashing of the old Jeffersonian 'diffusion' idea." - Crapol, 2006, p. 205: "... in an appeal to the racial fears of northern whites ..." Walker warned that "the only safety-valve for the whole Union, and the only practicable outlet for the African population is through Texas, into Mexico and Central and South America".

- Crapol, 2006, p. 206: "The idea of shipping blacks to Africa ... was a solution Jefferson, Madison and John Tyler had embraced, and later pursued by Abraham Lincoln during the first year of the Civil War when he attempted to launch a Haitian colonization scheme."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 206: Walker warned of "the ever-threatening British who were intent on preventing annexation ... as part of their overall plan to undercut American national destiny."

- Freehling, 1991, p. 418: Failure to annex Texas, according to Walker "would lead to British-induced emancipation in Texas, then to Yankee-induced emancipation in the South, then to freed slaves swarming northwards towards their liberators."

- Freehling, 1991, p. 423: "Nowhere was the economic tremor of the 1840s more evident than in the older eastern South" where poor cotton yields "intensified the search for a way out." and "... in Texas, went the dream ... demand for slaves might increase slave prices, bailing out the less prosperous southeast. But close the safety valve, heap up redundant slaves back on the decaying older South, and black hands would be increasingly idle." And p. 424: "... the claustrophobia of the Southeast, pent up with too many increasingly dispensable" slaves.

- Crapol, 2006, p. 206: "Senator Walker ... once again proposed the all-purpose remedy of annexation [which would] 'strengthen and fortify the whole Union.'"

- Freehling, 1991, p. 418: "The Walker thesis transformed sorely pressed Northern Democrats from traitors who knuckled under to the Slavepower into heroes who would diffuse blacks further from the North."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 207: In the weeks and months following its publication, his letter "shaped and framed" the public debate.

Freehling, 1991, p. 422: "No one called Walker's [analysis] 'untrue'." - Merk, 1978, p. 286: "Texas ... admitted as a territory subject to the same constitutional provisions as other territories ..."

- Holt, 2005, p. 13: "Under the original terms of the Democratic resolution, Texas would be admitted to the Union as a territory, not as a state; furthermore, in return for paying off the bonded debt Texas had accrued since 1836, the United States would own all the unsold public land in the huge republic.

Freehling, 1991, p. 440 - Crapol, 2006, p. 213

Merk, 1978, p. 286: "What the Senate would ratify was kept constantly in mind" during the Tyler-Texas negotiation. - Crapol, 2006, p. 213: "This garrison ... named the Army of Observation" and "... a powerful naval force to the Gulf of Mexico."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 213: "Tyler was true to his word."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 217: Cabinet members "were split on the wisdom of [Tyler's] Texas machinations ... Wilkins, a Democrat, was solidly behind Tyler on Texas ..." and "stressed the economic benefits for [his home state Pennsylvania] ..." and the need to prevent Texas from "becoming a commercial dependency of Great Britain."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 217: "Spencer thought Tyler's directive [to supply funds without Congressional sanction] was illegal ... After twice refusing to execute the president's order, Secretary Spencer resigned his cabinet post on May 2, 1844."

- Freehling, 1991, p. 408: "On April 22, 1844, the Senate received the pre-treaty correspondence [and] the [Tyler] treaty ..."

- Finkelman, 2011, p. 29: "A treaty required a two-thirds majority [in the Senate] for ratification."

- Freehling, 1991, p. 407: "The new Secretary of State [Calhoun] reached Washington March 29, 1844."

- Freehling, 1991, p. 415: "... Calhoun could only begin to provoke a 'sense of crisis' with southern Democrats.", and "The Packenham Letter could rally southern Democrats against the party's northern establishment ..."

May, 2008, p. 113: "The Packenham Letter proved the claims of anti-annexationists and abolitionists that the Texas question was only about slavery – its expansion and preservation – despite Tyler's protestations to the contrary."

Varon, 2008, p. 167: Calhoun "unabashedly cast Texas as a stronghold for slavery." - Freehling, 1991, p. 408: The Packenham Letter "declared the national [Texas] treaty a sectional weapon, designed to protect slavery's blessings from England's documented interference" and "aimed at driving southerners to see England's soft threat in a hard-headed way."

May 2008, pp. 112–113: "Calhoun ... insisted that the 'peculiar institution' was, in fact, 'a political institution necessary to peace, safety and prosperity." - Merry, 2009, pp. 67–68: Calhoun "wanted to expand the country's slave territory and thus retain the South's numerical and political advantage in regional disputes. He also wanted to force a slave issue confrontation within the country ... if that confrontation should split the Union, Texas would add luster and power to an independent South."

Freehling, 2008, pp. 409–410: "Nothing would have made Northern Whigs tolerate the [Packenham] document, and Northern Democrats would have to be forced to swallow their distaste for the accord. Calhoun's scenario of rallying enough slaveholders to push enough Northern Democrats to stop evading the issue was exactly the way the election of 1844 and annexation aftermath transpired." - Crapol, 2006, p. 216: "... the Tyler administration assumed that the Senate would consider annexation in executive session ... which meant the text of the treaty and accompanying documents would not be made public until after the vote on ratification."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 214

- Crapol, 2006, pp. 216–217: "As opposition to the Texas treaty mounted, the two leading candidates for the Whig and Democratic presidential nominations came out against immediate annexation."

- Merk, 1978, p. 288: Tyler moved the annexation issue "into the presidential campaign of 1844, which was underway."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 218: "In an attempt to salvage his presidential candidacy and to gain approval of his Texas annexation treaty ... Tyler sanctioned a third-party movement ... [A] band of Tyler followers, many of them postmasters and other recipients of his executive patronage ..." and "... a tactical maneuver [to] pressure Democrats to adopt an expansionist platform favoring the annexation of Texas."

- Crapol, 2006, p. 218: "Tyler explained ... that the third-party ploy worked because it made Democrats realize that a '[Pro-]Texas man or defeat was the only choice.'"

May, 2008, p. 114: "If Tyler stayed in the race, he threatened to draw enough votes from Polk to elect Clay, which handed Tyler an opportunity to secure his [Texas] legacy." - Finkelman, 2011, p. 27: "This was a superb strategy, because while Polk was much more interested in Texas, asserting expansive claims in the Pacific Northwest made him palatable to many northerners."

Crapol, 2006, p. 218: "After bitter wrangling they denied Martin Van Buren the nomination and chose ... James K. Polk ... an outspoken expansionist, and his campaign platform called for the reannexation of Texas and the reoccupation of Oregon." - May, 2008, p. 119: "If Polk or his representative could give Tyler that guarantee [to annex Texas], he promised to 'withdraw' and support Polk enthusiastically." and p. 120: "Tyler's supporters easily switched their allegiance to Polk [because] 'Polk would be the advocate of most of [his] measures.'"

- Crapol, 2006, p. 219: "In November Polk narrowly defeated Henry Clay in the popular vote by just over 38,000 out of 2.7 million votes cast ..."

- Holt, 2005, p. 12: "The Democrats' triumph in the 1844 elections [the Polk victory] increased the odds of Texas annexation ... [and with] their heavy majority in the House, Democrats could easily pass the resolution containing the same terms as Tyler's rejected treaty."

- Sellers, 1966, p. 168: "Even Benton's allies of the Wright-Van Buren persuasion had argued during the campaign for annexation in the proper manner, objecting only to [the Tyler-Calhoun treaty, with emphasis on slavery expansion]" and p. 168: Pro-annexation Northern Democrats "came to Washington [D.C.] 'prepared to vote for admission [of Texas] as a state ... saying nothing about slavery."

- Senate Journal, June 8, 1844, volume 430, pp. 436–438

- May, 2008, pp. 114–115

Freehling, 1991, p. 443 - Sellers, 1966, p. 168: "The chain of events running back through the Baltimore convention to Calhoun's Packenham letter had finally polarized the Democrats along North-South lines."

- Merry, 2009, pp. 72–73: Calhoun's "letter to British minister Richard Packenham ... contained language so incendiary and politically audacious that it would render Senate ratification nearly impossible ..."

- Crapol, 2006, pp. 218–219: "Untroubled by the initial failure, Tyler had carefully prepared for just such a contingency ... recommending [Congress] consider another path to annexation."

- Holt, 2005, pp. 10–11

- Freehling, 1991, p. 440: "... the lame-duck Congress returned to Washington in December 1844 ..." and p. 443: "The previous June, this same Senate had scuttled Tyler's treaty of annexation, 35–16."

Holt, 2005, p. 12 - Wilentz, 2008, p. 575

- Wilentz, 2008, p. 575