Flight recorder

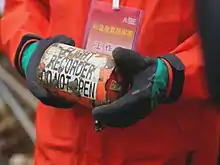

A flight recorder is an electronic recording device placed in an aircraft for the purpose of facilitating the investigation of aviation accidents and incidents. The device may often be referred to as a "black box", an outdated name which has become a misnomer—they are now required to be painted bright orange, to aid in their recovery after accidents.

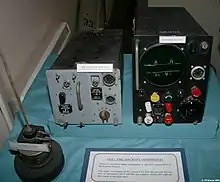

There are two types of flight recording devices: the flight data recorder (FDR) preserves the recent history of the flight through the recording of dozens of parameters collected several times per second; the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) preserves the recent history of the sounds in the cockpit, including the conversation of the pilots. The two devices may be combined into a single unit. Together, the FDR and CVR objectively document the aircraft's flight history, which may assist in any later investigation.

The two flight recorders are required by international regulation, overseen by the International Civil Aviation Organization, to be capable of surviving the conditions likely to be encountered in a severe aircraft accident. For this reason, they are typically specified to withstand an impact of 3400 g and temperatures of over 1,000 °C (1,830 °F), as required by EUROCAE ED-112. They have been a mandatory requirement in commercial aircraft in the United States since 1967. After the unexplained disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 in 2014, commentators have called for live streaming of data to the ground, as well as extending the battery life of the underwater locator beacons.

History

Early designs

One of the earliest and proven attempts was made by François Hussenot and Paul Beaudouin in 1939 at the Marignane flight test center, France, with their "type HB" flight recorder; they were essentially photograph-based flight recorders, because the record was made on a scrolling photographic film 8 metres (8.7 yd) long by 88 millimetres (3.5 in) wide. The latent image was made by a thin ray of light deviated by a mirror tilted according to the magnitude of the data to be recorded (altitude, speed, etc.).[1] A pre-production run of 25 "HB" recorders was ordered in 1941 and HB recorders remained in use in French flight test centers well into the 1970s.[2][3]

In 1947, Hussenot founded the Société Française des Instruments de Mesure with Beaudouin and another associate, so as to market his invention, which was also known as the "hussenograph". This company went on to become a major supplier of data recorders, used not only aboard aircraft but also trains and other vehicles. SFIM is today part of the Safran group and is still present in the flight recorder market. The advantage of the film technology was that it could be easily developed afterwards and provides a durable, visual feedback of the flight parameters without needing any playback device. On the other hand, unlike magnetic tapes or later flash memory-based technology, a photographic film cannot be erased and reused, and so must be changed periodically. The technology was reserved for one-shot uses, mostly during planned test flights: it was not mounted aboard civilian aircraft during routine commercial flights. Also, cockpit conversation was not recorded.

Another form of flight data recorder was developed in the UK during World War II. Len Harrison and Vic Husband developed a unit that could withstand a crash and fire to keep the flight data intact. The unit was the forerunner of today's recorders, in being able to withstand conditions that aircrew could not. It used copper foil as the recording medium, with various styli, corresponding to various instruments or aircraft controls, indenting the foil. The foil was periodically advanced at set time intervals, giving a history of the aircraft's instrument readings and control settings. The unit was developed at Farnborough for the Ministry of Aircraft Production. At the war's end the Ministry got Harrison and Husband to sign over their invention to it and the Ministry patented it under British patent 19330/45.

The first modern flight data recorder, called "Mata Hari", was created in 1942 by Finnish aviation engineer Veijo Hietala. This black high-tech mechanical box was able to record all important details during test flights of fighter aircraft that the Finnish army repaired or built in its main aviation factory in Tampere, Finland.[4]

During World War II both British and American air forces successfully experimented with aircraft voice recorders.[5] In August 1943 the USAAF conducted an experiment with a magnetic wire recorder to capture the inter-phone conversations of a B-17 bomber flight crew on a combat mission over Nazi-occupied France.[6] The recording was broadcast back to the United States by radio two days afterwards.

Australian designs

In 1953, while working at the Aeronautical Research Laboratories (ARL) of the Defence Science and Technology Organisation, in Melbourne,[7] Australian research scientist David Warren conceived a device that would record not only the instrument readings, but also the voices in the cockpit.[8] In 1954 he published a report entitled "A Device for Assisting Investigation into Aircraft Accidents".[9]

Warren built a prototype FDR called "The ARL Flight Memory Unit" in 1956,[9] and in 1958 he built the first combined FDR/CVR prototype.[8][10] It was designed with civilian aircraft in mind, explicitly for post-crash examination purposes.[11] Aviation authorities from around the world were largely uninterested at first, but this changed in 1958 when Sir Robert Hardingham, the secretary of the British Air Registration Board, visited the ARL and was introduced to David Warren.[7] Hardingham realized the significance of the invention and arranged for Warren to demonstrate the prototype in the UK.[9]

The ARL assigned an engineering team to help Warren develop the prototype to airborne stage. The team, consisting of electronics engineers Lane Sear, Wally Boswell and Ken Fraser, developed a working design that incorporated a fire-resistant and shockproof case, a reliable system for encoding and recording aircraft instrument readings and voice on one wire, and a ground-based decoding device. The ARL system, made by the British firm of S. Davall & Sons Ltd, in Middlesex, was named the "Red Egg" because of its shape and bright red color.[9]

The units were redesigned in 1965 and relocated at the rear of aircraft to increase the probability of successful data retrieval after a crash.[12]

Carriage of data recording equipment became mandatory in UK-registered aircraft in two phases, the first for new turbine-engined public transport category aircraft over 12,000 lb (5,400 kg) in weight was mandated in 1965, with a further requirement in 1966 for piston-engined transports over 60,000 lb (27,000 kg), with the earlier requirement further extended to all jet transports. One of the first UK uses of the data recovered from an aircraft accident was that recovered from the Royston "Midas" data recorder that was onboard the British Midland Argonaut involved in the Stockport Air Disaster in 1967.[13]

US designs

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The flight recorder was invented and patented in the United States by Professor James J. "Crash" Ryan, a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Minnesota from 1931 to 1963. Ryan's "Flight Recorder" patent was filed in August 1953 and approved on November 8, 1960, as US Patent 2,959,459.[14] A second patent by Ryan for a "Coding Apparatus For Flight Recorders and the Like" is US Patent 3,075,192[15] dated January 22, 1963. An early prototype of the Ryan Flight Data Recorder is described in the January 2013 Aviation History article "Father of the Black Box" by Scott M. Fisher.[16]

Ryan, also the inventor of the retractable safety seat belt now required in automobiles, began working on the idea of a flight recorder in 1946, and invented the device in response to a 1948 request from the Civil Aeronautics Board aimed at establishing operating procedures to reduce air mishaps. The requirement was for a means of accumulating flight data. The original device was known as the "General Mills Flight Recorder".

The benefits of the flight recorder and the coding apparatus for flight recorders were outlined by Ryan in his study entitled "Economies in Airline Operation with Flight Recorders" which was entered into the Congressional Record in 1956. Ryan's flight recorder maintained a continuing recording of aircraft flight data such as engine exhaust temperature, fuel flow, aircraft velocity, altitude, control surfaces positions, and rate of descent.

A "Cockpit Sound Recorder" (CSR) was independently invented and patented by Edmund A. Boniface Jr., an aeronautical engineer at Lockheed Aircraft Corporation.[17][18][19] He originally filed with the US Patent Office on February 2, 1961, as an "Aircraft Cockpit Sound Recorder".[20] The 1961 invention was viewed by some as an "invasion of privacy". Subsequently Boniface filed again on February 4, 1963, for a "Cockpit Sound Recorder" (US Patent 3,327,067)[17] with the addition of a spring-loaded switch which allowed the pilot to erase the audio/sound tape recording at the conclusion of a safe flight and landing.

Boniface's participation in aircraft crash investigations in the 1940s[21] and in the accident investigations of the loss of one of the wings at cruise altitude on each of two Lockheed Electra turboprop powered aircraft (Flight 542 operated by Braniff Airlines in 1959 and Flight 710 operated by Northwest Orient Airlines in 1961) led to his wondering what the pilots may have said just prior to the wing loss and during the descent as well as the type and nature of any sounds or explosions that may have preceded or occurred during the wing loss.[22]

His patent was for a device for recording audio of pilot remarks and engine or other sounds to be "contained with the in-flight recorder within a sealed container that is shock mounted, fireproofed and made watertight" and "sealed in such a manner as to be capable of withstanding extreme temperatures during a crash fire". The CSR was an analog device which provided a continuous erasing/recording loop (lasting 30 or more minutes) of all sounds (explosion, voice, and the noise of any aircraft structural components undergoing serious fracture and breakage) which could be overheard in the cockpit.[22]

Terminology

The term "black box" was a World War II British phrase, originating with the development of radio, radar, and electronic navigational aids in British and Allied combat aircraft. These often-secret electronic devices were literally encased in non-reflective black boxes or housings. The earliest identified reference to "black boxes" occurs in a May 1945 Flight article, "Radar for Airlines", describing the application of wartime RAF radar and navigational aids to civilian aircraft: "The stowage of the 'black boxes' and, even more important, the detrimental effect on performance of external aerials, still remain as a radio and radar problem."[23] (The term "black box" is used with a different meaning in science and engineering, describing a system exclusively by its inputs and outputs, with no information whatsoever about its inner workings.)

Magnetic tape and wire voice recorders had been tested on RAF and USAAF bombers by 1943 thus adding to the assemblage of fielded and experimental electronic devices employed on Allied aircraft. As early as 1944 aviation writers envisioned use of these recording devices on commercial aircraft to aid incident investigations.[24] When modern flight recorders were proposed to the British Aeronautical Research Council in 1958, the term "black box" was in colloquial use by experts.[25]

By 1967 when flight recorders were mandated by leading aviation countries, the expression had found its way into general use: "These so-called 'black boxes' are, in fact, of fluorescent flame-orange in colour."[26] The formal names of the devices are flight data recorder and cockpit voice recorder. The recorders must be housed in boxes that are bright orange in color to make them more visually conspicuous in the debris after an accident.[27]

Components

Flight data recorder

A flight data recorder (FDR; also ADR, for accident data recorder) is an electronic device employed to record instructions sent to any electronic systems on an aircraft.

The data recorded by the FDR are used for accident and incident investigation. Due to their importance in investigating accidents, these ICAO-regulated devices are carefully engineered and constructed to withstand the force of a high speed impact and the heat of an intense fire. Contrary to the popular term "black box", the exterior of the FDR is coated with heat-resistant bright orange paint for high visibility in wreckage, and the unit is usually mounted in the aircraft's tail section, where it is more likely to survive a crash. Following an accident, the recovery of the FDR is usually a high priority for the investigating body, as analysis of the recorded parameters can often detect and identify causes or contributing factors.[28]

Modern day FDRs receive inputs via specific data frames from the flight-data acquisition units. They record significant flight parameters, including the control and actuator positions, engine information and time of day. There are 88 parameters required as a minimum under current US federal regulations (only 29 were required until 2002), but some systems monitor many more variables. Generally each parameter is recorded a few times per second, though some units store "bursts" of data at a much higher frequency if the data begin to change quickly. Most FDRs record approximately 17–25 hours of data in a continuous loop. It is required by regulations that an FDR verification check (readout) is performed annually in order to verify that all mandatory parameters are recorded. Many aircraft today are equipped with an "event" button in the cockpit that could be activated by the crew if an abnormality occurs in flight. Pushing the button places a signal on the recording, marking the time of the event.[29]

Modern FDRs are typically double wrapped in strong corrosion-resistant stainless steel or titanium, with high-temperature insulation inside. Modern FDRs are accompanied by an underwater locator beacon that emits an ultrasonic "ping" to aid in detection when submerged. These beacons operate for up to 30 days and are able to operate while immersed to a depth of up to 6,000 meters (20,000 ft).[30][31]

Cockpit voice recorder

A cockpit voice recorder (CVR) is a flight recorder used to record the audio environment in the flight deck of an aircraft for the purpose of investigation of accidents and incidents. This is typically achieved by recording the signals of the microphones and earphones of the pilots' headsets and of an area microphone in the roof of the cockpit. The current applicable FAA TSO is C123b titled Cockpit Voice Recorder Equipment.[32]

Where an aircraft is required to carry a CVR and uses digital communications the CVR is required to record such communications with air traffic control unless this is recorded elsewhere. As of 2008 it is an FAA requirement that the recording duration is a minimum of two hours.[33]

A standard CVR is capable of recording four channels of audio data for a period of two hours. The original requirement was for a CVR to record for 30 minutes, but this has been found to be insufficient in many cases because significant parts of the audio data needed for a subsequent investigation occurred more than 30 minutes before the end of the recording.[34]

The earliest CVRs used analog wire recording, later replaced by analog magnetic tape. Some of the tape units used two reels, with the tape automatically reversing at each end. The original was the ARL Flight Memory Unit produced in 1957 by Australian David Warren and instrument maker Tych Mirfield.[35][36]

Other units used a single reel, with the tape spliced into a continuous loop, much as in an 8-track cartridge. The tape would circulate and old audio information would be overwritten every 30 minutes. Recovery of sound from magnetic tape often proves difficult if the recorder is recovered from water and its housing has been breached. Thus, the latest designs employ solid-state memory and use digital recording techniques, making them much more resistant to shock, vibration and moisture. With the reduced power requirements of solid-state recorders, it is now practical to incorporate a battery in the units, so that recording can continue until flight termination, even if the aircraft electrical system fails.

Like the FDR, the CVR is typically mounted in the rear of the airplane fuselage to maximize the likelihood of its survival in a crash.[37]

Combined units

With the advent of digital recorders, the FDR and CVR can be manufactured in one fireproof, shock proof, and waterproof container as a combined digital cockpit voice and data recorder (CVDR). Currently, CVDRs are manufactured by L3Harris Technologies[38] and Hensoldt[39] among others.

Solid state recorders became commercially practical in 1990, having the advantage of not requiring scheduled maintenance and making the data easier to retrieve. This was extended to the two-hour voice recording in 1995.[40]

Additional equipment

Since the 1970s, most large civil jet transports have been additionally equipped with a "quick access recorder" (QAR). This records data on a removable storage medium. Access to the FDR and CVR is necessarily difficult because they must be fitted where they are most likely to survive an accident; they also require specialized equipment to read the recording. The QAR recording medium is readily removable and is designed to be read by equipment attached to a standard desktop computer. In many airlines, the quick access recordings are scanned for "events", an event being a significant deviation from normal operational parameters. This allows operational problems to be detected and eliminated before an accident or incident results.

Many modern aircraft systems are digital or digitally controlled. Very often, the digital system will include built-in test equipment which records information about the operation of the system. This information may also be accessed to assist with the investigation of an accident or incident.

Specifications

The design of today's FDR is governed by the internationally recognized standards and recommended practices relating to flight recorders which are contained in ICAO Annex 6 which makes reference to industry crashworthiness and fire protection specifications such as those to be found in the European Organisation for Civil Aviation Equipment[41] documents EUROCAE ED55, ED56 Fiken A and ED112 (Minimum Operational Performance Specification for Crash Protected Airborne Recorder Systems). In the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulates all aspects of US aviation, and cites design requirements in their Technical Standard Order,[42] based on the EUROCAE documents (as do the aviation authorities of many other countries).

Currently, EUROCAE specifies that a recorder must be able to withstand an acceleration of 3400 g (33 km/s2) for 6.5 milliseconds. This is roughly equivalent to an impact velocity of 270 knots (310 mph; 500 km/h) and a deceleration or crushing distance of 45 cm (18 in).[43] Additionally, there are requirements for penetration resistance, static crush, high and low temperature fires, deep sea pressure, sea water immersion, and fluid immersion.

EUROCAE ED-112 (Minimum Operational Performance Specification for Crash Protected Airborne Recorder Systems) defines the minimum specification to be met for all aircraft requiring flight recorders for recording of flight data, cockpit audio, images and CNS / ATM digital messages and used for investigations of accidents or incidents.[44] When issued in March 2003 ED-112 superseded previous ED-55 and ED-56A that were separate specifications for FDR and CVR. FAA TSOs for FDR and CVR reference ED-112 for characteristics common to both types.

In order to facilitate recovery of the recorder from an aircraft accident site they are required to be coloured bright yellow or orange with reflective surfaces. All are lettered "Flight recorder do not open" on one side in English and "Enregistreur de vol ne pas ouvrir" in French on the other side. To assist recovery from submerged sites they must be equipped with an underwater locator beacon which is automatically activated in the event of an accident.

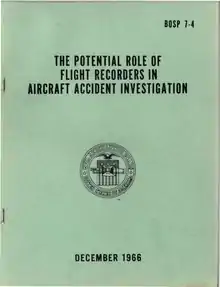

Accident investigation

On November 1, 1966, Bobbie R. Allen - director of Bureau of Safety, Civil Aeronautics Board and John S. Leak - chief of Technical Services Section, presented "The Potential Role of Flight Recorders in Aircraft Accident Investigation" at the AIAA/CASI Joint Meeting on Aviation Safety, Toronto, Canada.[45] The vision of these professionals contributed greatly to improvements in the technology and accident investigation.

Regulation

In the investigation of the 1960 crash of Trans Australia Airlines Flight 538 at Mackay, Queensland, the inquiry judge strongly recommended that flight recorders be installed in all Australian airliners. Australia became the first country in the world to make cockpit-voice recording compulsory.[46][47]

The United States' first CVR rules were passed in 1964, requiring all turbine and piston aircraft with four or more engines to have CVRs by March 1, 1967.[48] As of 2008 it is an FAA requirement that the CVR recording duration is a minimum of two hours,[33] following the NTSB recommendation that it should be increased from its previously-mandated 30-minute duration.[49] From 2014 the United States requires flight data recorders and cockpit voice recorders on aircraft that have 20 or more passenger seats, or those that have six or more passenger seats, are turbine-powered, and require two pilots.[50]

For US air carriers and manufacturers, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) is responsible for investigating accidents and safety-related incidents. The NTSB also serves in an advisory role for many international investigations not under its formal jurisdiction. The NTSB does not have regulatory authority, but must depend on legislation and other government agencies to act on its safety recommendations.[51] In addition, 49 USC Section 1114(c) prohibits the NTSB from making the audio recordings public except by written transcript.[52]

The ARINC Standards are prepared by the Airlines Electronic Engineering Committee (AEEC). The 700 Series of standards describe the form, fit, and function of avionics equipment installed predominately on transport category aircraft. The FDR is defined by ARINC Characteristic 747. The CVR is defined by ARINC Characteristic 757.[53]

Deployable recorders

The NTSB recommended in 1999 that operators be required to install two sets of CVDR systems, with the second CVDR set being "deployable or ejectable". The "deployable" recorder combines the cockpit voice/flight data recorders and an emergency locator transmitter (ELT) in a single unit. The "deployable" unit would depart the aircraft before impact, activated by sensors. The unit is designed to "eject" and "fly" away from the crash site, to survive the terminal velocity of fall, to float on water indefinitely, and would be equipped with satellite technology for immediate location of crash impact site. The "deployable" CVDR technology has been used by the US Navy since 1993.[54] While the recommendations would involve a massive, expensive retrofit program, government funding would meet cost objections from manufacturers and airlines. Operators would get both sets of recorders (including the currently-used fixed recorder) free of charge. The cost of the second "deployable/ejectable CVDR" (or "black box") was estimated at US$30 million for installation in 500 new aircraft (about $60,000 per new commercial plane).

In the United States, the proposed SAFE Act calls for implementing the NTSB 1999 recommendations. However, so far the SAFE Act legislation has failed to pass Congress, having been introduced in 2003 (H.R. 2632), in 2005 (H.R. 3336), and in 2007 (H.R. 4336).[55] Originally the "Safe Aviation Flight Enhancement (SAFE) Act of 2003"[56] was introduced on June 26, 2003, by Congressman David Price (D-NC) and Congressman John Duncan (R-Tenn.) in a bipartisan effort to ensure investigators have access to information immediately following commercial accidents.[54]

On July 19, 2005, a revised SAFE Act was introduced and referred to the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure of the US House of Representatives. The bill was referred to the House Subcommittee on Aviation during the 108th, 109th, and 110th Congresses.[57][58][59]

After Malaysia Airlines Flight 370

In the United States, on March 12, 2014, in response to the missing Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, David Price re-introduced the SAFE Act in the US House of Representatives.[60]

The disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 demonstrated the limits of the contemporary flight recorder technology, namely how physical possession of the flight recorder device is necessary to help investigate the cause of an aircraft incident. Considering the advances of modern communication, technology commentators called for flight recorders to be supplemented or replaced by a system that provides "live streaming" of data from the aircraft to the ground.[61][62][63] Furthermore, commentators called for the underwater locator beacon's range and battery life to be extended, as well as the outfitting of civil aircraft with the deployable flight recorders typically used in military aircraft. Previous to MH370, the investigators of 2009 Air France Flight 447 urged that the battery life be extended as "rapidly as possible" after the crash's flight recorders went unrecovered for over a year.[64]

After Indonesia AirAsia Flight 8501

On December 28, 2014, Indonesia AirAsia Flight 8501, en route from Surabaya, Indonesia, to Singapore, crashed in bad weather, killing all 155 passengers and seven crew on board.[65]

On January 8, 2015, before the recovery of the flight recorders, an anonymous ICAO representative said: "The time has come that deployable recorders are going to get a serious look."[66] A second ICAO official said that public attention had "galvanized momentum in favour of ejectable recorders on commercial aircraft".[66]

Boeing 737 MAX

Live flight data streaming as on the Boeing 777F EcoDemonstrator, plus 20 minutes of data before and after a triggering event, could have removed the uncertainty before the Boeing 737 MAX groundings following the March 2019 Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 crash.[67]

Image recorders

The NTSB has asked for the installation of cockpit image recorders in large transport aircraft to provide information that would supplement existing CVR and FDR data in accident investigations. They have recommended that image recorders be placed into smaller aircraft that are not required to have a CVR or FDR.[68] The rationale is that what is seen on an instrument by the pilots of an aircraft is not necessarily the same as the data sent to the display device. This is particularly true of aircraft equipped with electronic displays (CRT or LCD). A mechanical instrument panel is likely to preserve its last indications, but this is not the case with an electronic display. Such systems, estimated to cost less than $8,000 installed, typically consist of a camera and microphone located in the cockpit to continuously record cockpit instrumentation, the outside viewing area, engine sounds, radio communications, and ambient cockpit sounds. As with conventional CVRs and FDRs, data from such a system is stored in a crash-protected unit to ensure survivability.[68] Since the recorders can sometimes be crushed into unreadable pieces, or even located in deep water, some modern units are self-ejecting (taking advantage of kinetic energy at impact to separate themselves from the aircraft) and also equipped with radio emergency locator transmitters and sonar underwater locator beacons to aid in their location.[69]

Cultural references

The artwork for the band Rammstein's album Reise, Reise is made to look like a CVR; it also includes a recording from a crash. The recording is from the last 1–2 minutes of the CVR of Japan Airlines Flight 123, which crashed on August 12, 1985, killing 520 people; JAL123 is the deadliest single-aircraft disaster in history.

Members of the performing arts collective Collective:Unconscious made a theatrical presentation[70] of a play called Charlie Victor Romeo with a script based on transcripts from CVR voice recordings of nine aircraft emergencies. The play features the famous United Airlines Flight 232 that crash-landed in a cornfield near Sioux City, Iowa, after suffering a catastrophic failure of one engine and most flight controls.

Survivor, a novel by Chuck Palahniuk, is about a cult member who dictates his life story to a flight recorder before the plane runs out of fuel and crashes.

See also

- Acronyms and abbreviations in avionics

- Data logger

- Emergency locator beacon

- Emergency position-indicating radiobeacon station

- Event data recorder

- Flight operations quality assurance

- Korean Air Lines Flight 007

- List of unrecovered flight recorders

- Quick access recorder

- Software flight recorder

- Train event recorder

- Voyage data recorder

References

- Jean-Claude Fayer, Vols d'essais: Le Centre d'Essais en Vol de 1945 à 1960, published by E.T.A.I. (Paris), 2001, 384 pages, ISBN 2-7268-8534-9

- Page 206 and 209 of Beaudouin & Beaudouin

- Black Box History, May 22, 2020, archived from the original on January 25, 2022, retrieved May 22, 2020

- "Mata-Hari or Black Box". Museums of Tampere (in Finnish). 1946. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- Chuck Owl (February 4, 2015), Audio From the Past [E01] - WW2 - Avro Lancaster Crew Radio, archived from the original on November 16, 2018, retrieved February 13, 2019

- Porter, Kenneth (January 1944). "Radio News, 'Radio - On a Flying Fortress'" (PDF). www.americanradiohistory.com. p. 21. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- "Dave Warren – Inventor of the black box flight recorder". Defence Science and Technology Organisation. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011.

- "Australia invented the Black Box voice and instrument recorder". apc-online.com. February 9, 2000. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- Marcus Williamson (July 31, 2010). "David Warren: Inventor and developer of the 'black box' flight data recorder". The Independent. Archived from the original on May 30, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- "A Brief History of Black Boxes". Time. July 20, 2009. p. 22.

- "A Brief History of Black Boxes". Time. July 20, 2009. p. 22. Archived from the original on February 3, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- Tony Bailey (January 2006). "Flight Data Recorders – Built to Survive" (PDF). aea.net. Avionics News. p. 38. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- "1967 | 1315 | Flight Archive". Archived from the original on February 14, 2019.

- "US Patent 2,959,459 for Flight Recorder by James J. Ryan". Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- "US Patent 3,075,192 for Coding Apparatus for Flight Recorders by James J. Ryan". Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- Fisher, Scott M. (January 2013). "Father of the Black Box". Aviation History. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- "Cockpit Sound Recorder". Google Patents. Google Inc. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- "Airplane 'Black Box' Flight Recorder Technology, How it Works" Archived October 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Slyck News, March 13, 2014

- " Why Are Cockpit Voice Recorders Painted Orange and Called a Black Box?" Archived September 17, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Guardian Liberty Voice, By Jerry Nelson on March 8, 2014

- "AAHS Journal Vol 59 Nos 3-4 - Fall / Win". www.aahs-online.org. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- "The Flight Data Recorder" Archived October 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Aviation Digest, May 11, 2015, page 58.

- US Patent 3,327,067 for Cockpit Sound Recorder by Edmund A. Boniface, Jr. Archived July 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine;

- "Flight, 'Radar for Airlines'". Flight. May 2, 1945. p. 434. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- Corddry, Charles Jr. (August 1944). Flying, 'Aerial Eavesdropper'. p. 150. Archived from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- Archived January 24, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Scott, Geoffrey (December 14, 1967). "Flight, 'Saving the Record'". www.flightglobal.com. p. 1002. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- "France to resume 'black box' hunt". BBC News. December 13, 2009. Archived from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- "Flight Data Recorder Systems" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. April 10, 2007. Section 3 Point B. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 13, 2009. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- "Aircraft Electronics + Electrical Systems: Flight data and cockpit voice recorders". industrial-electronics.com. A Measurement-Testing network. Archived from the original on November 11, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- "FLIGHT DATA RECORDER OSA - TM-1-1510-225-10_280". aviationandaccessories.tpub.com. Archived from the original on December 10, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- "SSFDR Solid State Flight Data Recorder, ARINC 747 - TSO C 124 - ED 55" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 8, 2012.

- "Cockpit Voice Recorder Equipment" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. June 1, 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- "Federal Aviation Regulation Sec. 121.359(h)(i)(2), amendment 338 and greater – Cockpit voice recorders". Risingup.com. Archived from the original on February 6, 2012. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- Tracy Connor (October 28, 1999). "Learjet probe focuses on value replaced 2 days before crash". The New York Post. p. 18.

The record works on a half hour loop, so it has no information about the crucial first hour

- "ARL Flight Memory Recorder". Museums Victoria Collections. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- Mirfield, Theon Neuma (May 1964). "Miniature wire recording desks with limited memory". The Australian Journal of Instrument Technology. May: 94–100. Archived from the original on October 20, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- "Federal Aviation Regulation Sec. 23.1457 – Cockpit voice recorders". Risingup.com. Archived from the original on February 10, 2012. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- "L-3 Aviation Recorders". l-3ar.com. Archived from the original on July 27, 2014. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- "Flight and mission data recording & management - SferiRec". Hensoldt. 2019. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- "History of Flight Recorders". L3 Flight Recorders. Archived from the original on December 11, 2013.

- Luftfahrt. "European Organisation for Civil Aviation Equipment". Eurocae.net. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- "TSO-C124a FAA Regs". Airweb.faa.gov. May 23, 2006. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- "Black box flight recorders". ATSB. April 1, 2014. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- Archived August 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Allen, B. R.; Leak, John S. (1966), "The potential role of flight recorders in aircraft accident investigation", Aviation Safety Meeting, BOSP 7-4, U.S. Civil Aeronautics Board, doi:10.2514/6.1966-810

- "Dave Warren - Inventor of the black box flight recorder". Defence Science and Technology Organisation. March 29, 2005. Archived from the original on May 22, 2010. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- Campbell, Neil. "The Evolution of Flight Data Analysis" (PDF). Proc. Australian Society of Air Safety Investigators conference, 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 4, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- Nick Komos (August 1989). "Air Progress": 76.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "2011 Most Wanted List Page. Recorders". NTSB Archived August 4, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- U.S. Code of Federal Regulations (April 25, 2010). "14 CFR 91.609". Legal Information Institute. Cornell Law School. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- "History of the NTSB". NTSB Official Site. Archived from the original on May 12, 2016. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- "CVR Handbook" (PDF). www.ntsb.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 3, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- "ARINC Store, 700 series". Archived from the original on August 14, 2011. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- "Aviation Today". aviationtoday.com. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014.

- "Safe Aviation and Flight Enhancement Act of 2005 (2005; 109th Congress H.R. 3336) - GovTrack.us". GovTrack.us. Archived from the original on March 22, 2014. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- "Text of the Safe Aviation and Flight Enhancement Act-((SAFE) Act of 2003)". Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved August 2, 2015 – via govtrack.us.

- "Bill Text - 108th Congress (2003-2004) - THOMAS (Library of Congress)". Thomas.loc.gov. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- "Bill Text - 109th Congress (2005-2006) - THOMAS (Library of Congress)". Thomas.loc.gov. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- "Bill Text - 110th Congress (2007-2008) - THOMAS (Library of Congress)". Thomas.loc.gov. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- Jansen, Bart. "Lawmaker urges 'black boxes' that eject from planes". USA Today. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- "Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 makes it clear: we need to rethink black boxes | Stephen Trimble | Comment is free". theguardian.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- "Malaysia Airlines MH370: Why airlines don't live-stream black box data". Technology & Science. CBC News. August 4, 2005. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- Yu, Yijun. "If we'd used the cloud, we might know where MH370 is now" Archived July 24, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, The Conversation, London, March 18, 2014. Retrieved on August 21, 2014.

- "MH370: Expert demands better black box technology". The Sydney Morning Herald. April 28, 2014. Archived from the original on April 28, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- "AirAsia QZ8501: More bad weather hits AirAsia search". BBC News. January 1, 2015. Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- Lampert, Allison Martell, Allison (January 8, 2015). "AirAsia crash makes case for ejectable black boxes". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 12, 2019. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- "Opinion: The Time Is Ripe for Live Flight Data Streaming". Aviation Week & Space Technology. March 22, 2019. Archived from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- "NTSB — Most Wanted". Ntsb.gov. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- "These Black Boxes Are Designed to Eject Themselves in a Plane Crash". Travel + Leisure. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- "Collective: Unconscious". Charlievictorromeo.com. July 3, 2012. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

Further reading

- American Aviation Historical Society, Volume 59, Fall-Winter 2014, "Edmund A. Boniface, Jr.: Inventing the Cockpit Sound Recorder"

- (Extraordinary), "Extraordinary Inventor", U of A Engineer Magazine, Winter 2005

- (Survivors), "Saving Survivors by Finding Fallen Aircrafts (sic)", NRC, 2008-03-05

- Jeremy Sear, "The ARL 'Black Box' Flight Recorder", University of Melbourne, October 2001

- Siegel, Greg (2014). "Chapter 3. Black Boxes". Forensic Media: Reconstructing Accidents in Accelerated Modernity. Duke University Press. pp. 89–142. ISBN 978-0-8223-7623-1.

- Wyatt, David; Mike Tooley (2009). "Chapter 18. Flight data and cockpit voice recorders". Aircraft Electrical and Electronic Systems. Routledge. p. 321. ISBN 978-1-136-44435-7.

- Ben Hargreaves (April 13, 2017). "Flight Data Recorder Evolution: Where Next?". MRO-network. Aviation Week. Could flight data recorders evolve to be useful in preventative maintenance as well?.

External links

![]() Media related to Flight data recorders at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Flight data recorders at Wikimedia Commons

- Cockpit Voice Recorder Database

- 'The ARL 'Black Box' Flight Recorder': Melbourne University history honors thesis on the development of the first cockpit voice recorder by David Warren

- Finnish Mata-Hari Flight Recorder in Museums of Tampere City

- "Beyond the Black Box: Instead of storing flight data on board, aircraft could easily send the information in real time to the ground", by Krishna M. Kavi, IEEE Spectrum, August 2010

- "A crash course in transportation safety". Archived from the original on February 11, 2009. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- David Warren interview transcript 2002, ABC TV (Australia)

- David Warren interview transcript 2003, ABC TV (Australia)

- etep, Flight Recorder designer

- Heavy Vehicle EDR information site for black box technology

- How Black Boxes Work at HowStuffWorks

- IRIG 106 Chapter 10: Flight data recorder digital recorder standard

- Public domain photos of recorders

- Popular Mechanics, March 19, 2008

- "His Crashes Helped Make Ours Less Dangerous"

- US 3075192 James J. Ryan: "Coding Apparatus for Flight Recorders and the Like"

- First modern flight recorder "Mata Hari" at display in Tampere Vapriikki Museum Centre.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Transportation Safety Board.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Transportation Safety Board.