Frankenstein

Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus is an 1818 novel written by English author Mary Shelley. Frankenstein tells the story of Victor Frankenstein, a young scientist who creates a sapient creature in an unorthodox scientific experiment. Shelley started writing the story when she was 18, and the first edition was published anonymously in London on 1 January 1818, when she was 20. Her name first appeared in the second edition, which was published in Paris in 1821.

Volume I, first edition | |

| Author | Mary Shelley |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Gothic novel, literary fiction, horror fiction, science fiction[1] |

| Set in | England, Ireland, Italy, France, Scotland, Switzerland, Russia, Germany; late 18th century |

| Published | 1 January 1818 |

| Publisher | Lackington, Hughes, Harding, Mavor & Jones |

| Pages | 280 |

| 823.7 | |

| LC Class | PR5397 .F7 |

| Text | Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus at Wikisource |

Shelley travelled through Europe in 1815, moving along the river Rhine in Germany, and stopping in Gernsheim, 17 kilometres (11 mi) away from Frankenstein Castle, where, two centuries before, an alchemist had engaged in experiments.[2][3][4][note 1] She then journeyed to the region of Geneva, Switzerland, where much of the story takes place. Galvanism and occult ideas were topics of conversation for her companions, particularly for her lover and future husband Percy B. Shelley. In 1816 Mary, Percy and Lord Byron had a competition to see who could write the best horror story.[5] After thinking for days, Shelley was inspired to write Frankenstein after imagining a scientist who created life and was horrified by what he had made.[6]

Though Frankenstein is infused with elements of the Gothic novel and the Romantic movement, Brian Aldiss has argued for regarding it as the first true science-fiction story. In contrast to previous stories with fantastical elements resembling those of later science fiction, Aldiss states, the central character "makes a deliberate decision" and "turns to modern experiments in the laboratory" to achieve fantastic results.[7] The novel has had a considerable influence on literature and on popular culture; it has spawned a complete genre of horror stories, films, and plays.

Since the publication of the novel, the name "Frankenstein" has often been used, erroneously, to refer to the monster, rather than to his creator/father.[8][9][10]

Summary

Captain Walton's introductory narrative

Frankenstein is a frame story written in epistolary form. It documents a fictional correspondence between Captain Robert Walton and his sister, Margaret Walton Saville. The story takes place in the eighteenth century (the letters are dated as "17-"). Robert Walton is a failed writer who sets out to explore the North Pole in hopes of expanding scientific knowledge. During the voyage, the crew spots a dog sled driven by a gigantic figure. A few hours later, the crew rescues a nearly frozen and emaciated man named Victor Frankenstein. Frankenstein has been in pursuit of the gigantic man observed by Walton's crew. Frankenstein starts to recover from his exertion; he sees in Walton the same obsession that has destroyed him and recounts a story of his life's miseries to Walton as a warning. The recounted story serves as the frame for Frankenstein's narrative.

Victor Frankenstein's narrative

Victor begins by telling of his childhood. Born in Naples, Italy, into a wealthy Genevan family, Victor and his younger brothers, Ernest and William, are sons of Alphonse Frankenstein and the former Caroline Beaufort. From a young age, Victor has a strong desire to understand the world. He is obsessed with studying theories of alchemists, though when he is older he realizes that such theories are considerably outdated. When Victor is five years old, his parents adopt Elizabeth Lavenza (the orphaned daughter of an expropriated Italian nobleman) whom Victor later marries. Victor's parents later take in another child, Justine Moritz, who becomes William's nanny.

Weeks before he leaves for the University of Ingolstadt in Germany, his mother dies of scarlet fever; Victor buries himself in his experiments to deal with the grief. At the university, he excels at chemistry and other sciences, soon developing a secret technique to impart life to non-living matter. He undertakes the creation of a humanoid, but due to the difficulty in replicating the minute parts of the human body, Victor makes the Creature tall, about 8 feet (2.4 m) in height, and proportionally large. Despite Victor's selecting its features to be beautiful, upon animation the Creature is instead hideous, with watery white eyes and yellow skin that barely conceals the muscles and blood vessels underneath. Repulsed by his work, Victor flees. While wandering the streets the next day, he meets his childhood friend, Henry Clerval, and takes Clerval back to his apartment, fearful of Clerval's reaction if he sees the monster. However, when Victor returns to his laboratory, the Creature is gone.

Victor falls ill from the experience and is nursed back to health by Clerval. After a four-month recovery, he receives a letter from his father notifying him of the murder of his brother William. Upon arriving in Geneva, Victor sees the Creature near the crime scene and becomes convinced that his creation is responsible. Justine Moritz, William's nanny, is convicted of the crime after William's locket, which contained a miniature portrait of Caroline, is found in her pocket. Victor knows that no one will believe him if he tries to clear Justine's name, and she is hanged. Ravaged by grief and guilt, Victor retreats into the mountains. While he hikes through Mont Blanc's Mer de Glace, he is suddenly approached by the Creature, who pleads for Victor to hear his tale.

The Creature's narrative

Intelligent and articulate, the Creature relates his first days of life, living alone in the wilderness. He found that people were afraid of him and hated him due to his appearance, which led him to fear and hide from them. While living in an abandoned structure connected to a cottage, he grew fond of the poor family living there and discreetly collected firewood for them, cleared snow away from their path, and performed other tasks to help them. Secretly living next to the cottage for months, the Creature learned to speak by listening to them and taught himself to read after discovering a lost satchel of books in the woods. When he saw his reflection in a pool, he realized his appearance was hideous, and it horrified him as much as it horrified normal humans. As he continued to learn of the family's plight, he grew increasingly attached to them, and eventually he approached the family in hopes of becoming their friend, entering the house while only the blind father was present. The two conversed, but on the return of the others, the rest of them were frightened. The blind man's son attacked him and the Creature fled the house. The next day, the family left their home out of fear that he would return. The Creature was enraged by the way he was treated and gave up hope of ever being accepted by humans. Although he hated his creator for abandoning him, he decided to travel to Geneva to find him because he believed that Victor was the only person with a responsibility to help him. On the journey, he rescued a child who had fallen into a river, but her father, believing that the Creature intended to harm them, shot him in the shoulder. The Creature then swore revenge against all humans. He travelled to Geneva using details from Victor's journal, murdered William, and framed Justine for the crime.

The Creature demands that Victor create a female companion like himself. He argues that as a living being, he has a right to happiness. The Creature promises that he and his mate will vanish into the South American wilderness, never to reappear, if Victor grants his request. Should Victor refuse, the Creature threatens to kill Victor's remaining friends and loved ones and not stop until he completely ruins him. Fearing for his family, Victor reluctantly agrees. The Creature says he will watch over Victor's progress.

Victor Frankenstein's narrative resumes

Clerval accompanies Victor to England, but they separate, at Victor's insistence, at Perth, Scotland. Victor suspects that the Creature is following him. Working on the female creature on Orkney, he is plagued by premonitions of disaster. He fears that the female will hate the Creature or become more evil than he is. Even more worrying to him is the idea that creating the second creature might lead to the breeding of a race that could plague humankind. He tears apart the unfinished female creature after he sees the Creature, who had indeed followed Victor, watching through a window. The Creature immediately bursts through the door to confront Victor and tries to threaten him into working again, but Victor is convinced that since the Creature is evil, his mate would be evil as well, and that the pair would threaten all of humanity by giving rise to a new race just like them. The Creature leaves, but gives a final threat: "I will be with you on your wedding night." Victor interprets this as a threat upon his life, believing that the Creature will kill him after he finally becomes happy. Victor sails out to sea to dispose of his instruments, falls asleep in the boat, is unable to return to shore because of changes in the winds, and ends up being blown to the Irish coast. When Victor lands in Ireland, he is arrested for Clerval's murder, as the Creature had strangled Clerval and left the corpse to be found where his creator had arrived. Victor suffers another mental breakdown and wakes to find himself in prison. However, he is shown to be innocent, and after being released, he returns home with his father, who has restored to Elizabeth some of her father's fortune.

In Geneva, Victor is about to marry Elizabeth and prepares to fight the Creature to the death, arming himself with pistols and a dagger. The night following their wedding, Victor asks Elizabeth to stay in her room while he looks for "the fiend". While Victor searches the house and grounds, the Creature strangles Elizabeth. From the window, Victor sees the Creature, who tauntingly points at Elizabeth's corpse; Victor tries to shoot him, but the Creature escapes. Victor's father, weakened by age and by the death of Elizabeth, dies a few days later. Seeking revenge, Victor pursues the Creature through Europe, then north into Russia, with his adversary staying ahead of him every step of the way. Eventually, the chase leads to the Arctic Ocean and then on towards the North Pole, and Victor reaches a point where he is within a mile of the Creature, but he collapses from exhaustion and hypothermia before he can find his quarry, allowing the Creature to escape. Eventually the ice around Victor's sledge breaks apart, and the resultant ice floe comes within range of Walton's ship.

Captain Walton's conclusion

At the end of Victor's narrative, Captain Walton resumes telling the story. A few days after the Creature vanishes, the ship becomes trapped in pack ice, and several crewmen die in the cold before the rest of Walton's crew insists on returning south once it is freed. Upon hearing the crew's demands, Victor is angered and, despite his condition, gives a powerful speech to them. He reminds them of why they chose to join the expedition and that it is hardship and danger, not comfort, that defines a glorious undertaking such as theirs. He urges them to be men, not cowards. However, although the speech makes an impression on the crew, it is not enough to change their minds and when the ship is freed, Walton regretfully decides to return south. Victor, even though he is in a very weak condition, states that he will go on by himself. He is adamant that the Creature must die.

Victor dies shortly thereafter, telling Walton, in his last words, to seek "happiness in tranquility and avoid ambition." Walton discovers the Creature on his ship, mourning over Victor's body. The Creature tells Walton that Victor's death has not brought him peace; rather, his crimes have made him even more miserable than Victor ever was. The Creature vows to kill himself so that no one else will ever know of his existence and Walton watches as the Creature drifts away on an ice raft, never to be seen again.

Author's background

Mary Shelley's mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, died from infection eleven days after giving birth to her. Shelley grew close to her father, William Godwin, having never known her mother. Godwin hired a nurse, who briefly cared for her and her half sister, before marrying second wife Mary Jane Clairmont, who did not like the close bond between Shelley and her father. The resulting friction caused Godwin to favour his other children.

Shelley's father was a famous author of the time, and her education was of great importance to him, although it was not formal. Shelley grew up surrounded by her father's friends, writers, and persons of political importance, who often gathered at the family home. This inspired her authorship at an early age. Mary met Percy Bysshe Shelley, who later became her husband, at the age of sixteen while he was visiting her father. Godwin did not approve of the relationship between his daughter and an older, married man, so they fled to France along with her stepsister, Claire Clairmont. It was during their trip to France that Percy probably had an affair with Mary's stepsister, Claire.[11] On 22 February 1815, Shelley gave birth prematurely to her first child, Clara who then died two weeks later. Over eight years, she endured a similar pattern of pregnancy and loss, one haemorrhage occurring until Percy placed her upon ice to cease the bleeding.[12]

In the summer of 1816, Mary, Percy, and Claire took a trip to visit Claire's lover, Lord Byron, in Geneva. During the visit, Byron suggested that he, Mary, Percy, and Byron's physician, John Polidori, have a competition to write the best ghost story to pass time stuck indoors.[13] Historians suggest that an affair occurred too, even that the father of one of Shelley's children may have been Byron.[12] Mary was just eighteen years old when she won the contest with her creation of Frankenstein.[14][15]

Literary influences

Shelley's work was heavily influenced by that of her parents. Her father was famous for Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and her mother famous for A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Her father's novels also influenced her writing of Frankenstein. These novels included Things as They Are; or, The Adventures of Caleb Williams, St. Leon, and Fleetwood. All of these books were set in Switzerland, similar to the setting in Frankenstein. Some major themes of social affections and the renewal of life that appear in Shelley's novel stem from these works she had in her possession. Other literary influences that appear in Frankenstein are Pygmalion et Galatée by Mme de Genlis, and Ovid, with the use of individuals identifying the problems with society.[16] Ovid also inspires the use of Prometheus in Shelley's title.[17]

The influence of John Milton's Paradise Lost and Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner are clearly evident in the novel. In The Frankenstein of the French Revolution, author Julia Douthwaite posits that Shelley probably acquired some ideas for Frankenstein's character from Humphry Davy's book Elements of Chemical Philosophy, in which he had written that "science has ... bestowed upon man powers which may be called creative; which have enabled him to change and modify the beings around him ...". References to the French Revolution run through the novel; a possible source may lie in François-Félix Nogaret's Le Miroir des événemens actuels, ou la Belle au plus offrant (1790), a political parable about scientific progress featuring an inventor named Frankésteïn, who creates a life-sized automaton.[18]

Both Frankenstein and the monster quote passages from Percy Shelley's 1816 poem, "Mutability", and its theme of the role of the subconscious is discussed in prose. Percy Shelley's name never appeared as the author of the poem, although the novel credits other quoted poets by name. Samuel Taylor Coleridge's poem "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner" (1798) is associated with the theme of guilt and William Wordsworth's "Tintern Abbey" (1798) with that of innocence.

Many writers and historians have attempted to associate several then popular natural philosophers (now called physical scientists) with Shelley's work because of several notable similarities. Two of the most noted natural philosophers among Shelley's contemporaries were Giovanni Aldini, who made many public attempts at human reanimation through bio-electric Galvanism in London,[19] and Johann Konrad Dippel, who was supposed to have developed chemical means to extend the life span of humans. While Shelley was aware of both of these men and their activities, she makes no mention of or reference to them or their experiments in any of her published or released notes.

Ideas about life and death discussed by Percy and Byron were of great interest to scientists of that time. They discussed ideas from Erasmus Darwin and the experiments of Luigi Galvani as well as James Lind.[20] Mary joined these conversations and the ideas of Darwin, Galvani and perhaps Lind were present in her novel.

Shelley's personal experiences also influenced the themes within Frankenstein. The themes of loss, guilt, and the consequences of defying nature present in the novel all developed from Mary Shelley's own life. The loss of her mother, the relationship with her father, and the death of her first child are thought to have inspired the monster and his separation from parental guidance. In a 1965 issue of The Journal of Religion and Health a psychologist proposed that the theme of guilt stemmed from her not feeling good enough for Percy because of the loss of their child.[15]

Composition

During the rainy summer of 1816, the "Year Without a Summer", the world was locked in a long, cold volcanic winter caused by the eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815.[21][22] Mary Shelley, aged 18, and her lover (and future husband), Percy Bysshe Shelley, visited Lord Byron at the Villa Diodati by Lake Geneva in Switzerland. The weather was too cold and dreary that summer to enjoy the outdoor holiday activities they had planned, so the group retired indoors until dawn.

Sitting around a log fire at Byron's villa, the company amused themselves by reading German ghost stories translated into French from the book Fantasmagoriana.[23] Byron proposed that they "each write a ghost story."[24] Unable to think of a story, Mary Shelley became anxious. She recalled being asked "Have you thought of a story?" each morning, and every time being "forced to reply with a mortifying negative."[25] During one evening in the middle of summer, the discussions turned to the nature of the principle of life. "Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated," Mary noted, "galvanism had given token of such things".[26] It was after midnight before they retired and, unable to sleep, she became possessed by her imagination as she beheld the "grim terrors" of her "waking dream".[6]

I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world.[27]

In September 2011, astronomer Donald Olson, after a visit to the Lake Geneva villa the previous year and inspecting data about the motion of the moon and stars, concluded that her "waking dream" took place between 2 a.m. and 3 a.m. on 16 June 1816, several days after the initial idea by Lord Byron that they each write a ghost story.[28]

Mary Shelley began writing what she assumed would be a short story, but with Percy Shelley's encouragement, she expanded the tale into a fully-fledged novel.[29] She later described that summer in Switzerland as the moment "when I first stepped out from childhood into life."[30] Shelley wrote the first four chapters in the weeks following the suicide of her half-sister Fanny.[31] This was one of many personal tragedies that impacted Shelley's work. Shelley's first child died in infancy, and when she began composing Frankenstein in 1816, she was probably nursing her second child, who was also dead by the time of Frankenstein's publication.[32] Shelley wrote much of the book while residing in a lodging house in the centre of Bath in 1816.[33]

Byron managed to write just a fragment based on the vampire legends he heard while travelling the Balkans, and from this John Polidori created The Vampyre (1819), the progenitor of the romantic vampire literary genre. Thus two seminal horror tales originated from the conclave.

The group talked about Enlightenment and Counter-Enlightenment ideas as well. Mary Shelley believed the Enlightenment idea that society could progress and grow if political leaders used their powers responsibly; however, she also believed the Romantic ideal that misused power could destroy society.[34]

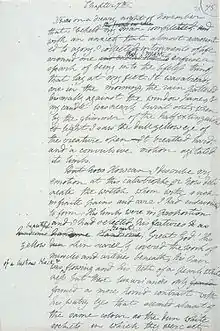

Shelley's manuscripts for the first three-volume edition in 1818 (written 1816–1817), as well as the fair copy for her publisher, are now housed in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. The Bodleian acquired the papers in 2004, and they belong now to the Abinger Collection.[35][36] In 2008, the Bodleian published a new edition of Frankenstein, edited by Charles E. Robinson, that contains comparisons of Mary Shelley's original text with Percy Shelley's additions and interventions alongside.[37]

Frankenstein and the Monster

The Creature

_Irish_Frankenstein_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Although the Creature was described in later works as a composite of whole body parts grafted together from cadavers and reanimated by the use of electricity, this description is not consistent with Shelley's work; both the use of electricity and the cobbled-together image of Frankenstein's monster were more the result of James Whale's popular 1931 film adaptation of the story and other early motion-picture works based on the creature. In Shelley's original work, Victor Frankenstein discovers a previously unknown but elemental principle of life, and that insight allows him to develop a method to imbue vitality into inanimate matter, though the exact nature of the process is left ambiguous. After a great deal of hesitation in exercising this power, Frankenstein spends two years painstakingly constructing the Creature's body (one anatomical feature at a time, from raw materials supplied by "the dissecting room and the slaughter-house"), which he then brings to life using his unspecified process.

Part of Frankenstein's rejection of his creation is the fact that he does not give him a name. Instead, Frankenstein's creation is referred to by words such as "wretch", "monster", "creature", "demon", "devil", "fiend", and "it". When Frankenstein converses with the creature, he addresses him as "vile insect", "abhorred monster", "fiend", "wretched devil", and "abhorred devil". John C. Engleworth, a Victorian literature professor at Cornell University,[36] posits that the creature was inspired by a man Shelley met in her time in Geneva with Lord Byron. The man was a beggar and geometer by the name of Noah Burdick, whom Shelley described in her travel diary as "sickly, gaunt, abysmally tall and lacking any human emotion, morality, or sensibilities".[35] Jackson Blackwell, a literary historian, corroborates this viewpoint.[39]

In the novel, the creature is compared to Adam,[39] the first man in the Garden of Eden. The monster also compares himself with the "fallen" angel. Speaking to Frankenstein, the monster says "I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel". That angel would be Lucifer (meaning "light-bringer") in Milton's Paradise Lost, which the monster has read. Adam is also referred to in the epigraph of the 1818 edition:[40]

- Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay

- To mould Me man? Did I solicit thee

- From darkness to promote me?[41]

The Creature has often been mistakenly called Frankenstein. In 1908, one author said "It is strange to note how well-nigh universally the term "Frankenstein" is misused, even by intelligent people, as describing some hideous monster."[42] Edith Wharton's The Reef (1916) describes an unruly child as an "infant Frankenstein."[43] David Lindsay's "The Bridal Ornament", published in The Rover, 12 June 1844, mentioned "the maker of poor Frankenstein". After the release of Whale's cinematic Frankenstein, the public at large began speaking of the Creature itself as "Frankenstein". This misnomer continued with the successful sequel Bride of Frankenstein (1935), as well as in film titles such as Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein.

Origin of Victor Frankenstein's name

Mary Shelley maintained that she derived the name Frankenstein from a dream-vision. This claim has since been disputed and debated by scholars that have suggested alternative sources for Shelley's inspiration.[45] The German name Frankenstein means "stone of the Franks," and is associated with various places in Germany, including Frankenstein Castle (Burg Frankenstein) in Darmstadt, Hesse, and Frankenstein Castle in Frankenstein, a town in the Palatinate. There is also a castle called Frankenstein in Bad Salzungen, Thuringia, and a municipality called Frankenstein in Saxony. Until 1945, Ząbkowice Śląskie, now a city in Lower Silesian Voivodeship, Poland, was mainly populated by Germans and was the site of a scandal involving gravediggers in 1606, which has been suggested as an inspiration to the author.[46] Finally, the name is borne by the aristocratic House of Franckenstein from Franconia.

Radu Florescu argued that Mary and Percy Shelley visited Frankenstein Castle near Darmstadt in 1814, where alchemist Johann Konrad Dippel had experimented with human bodies, and reasoned that Mary suppressed mention of her visit in order to maintain her public claim of originality.[47] A literary essay by A. J. Day supports Florescu's position that Mary Shelley knew of and visited Frankenstein Castle before writing her debut novel.[48] Day includes details of an alleged description of the Frankenstein castle in Mary Shelley's "lost journals." However, according to Jörg Heléne, Day's and Florescu's claims cannot be verified.[49]

A possible interpretation of the name "Victor" is derived from Paradise Lost by John Milton, a great influence on Shelley (a quotation from Paradise Lost is on the opening page of Frankenstein and Shelley writes that the monster reads it in the novel).[50][51] Milton frequently refers to God as "the victor" in Paradise Lost, and Victor's creation of life in the novel is compared to God's creation of life in Paradise Lost. In addition, Shelley's portrayal of the monster owes much to the character of Satan in Paradise Lost; and, the monster says in the story, after reading the epic poem, that he empathizes with Satan's role.

Parallels between Victor Frankenstein and Mary's husband, Percy Shelley, have also been drawn. Percy Shelley was the first-born son of a wealthy country squire with strong political connections and a descendant of Sir Bysshe Shelley, 1st Baronet of Castle Goring, and Richard Fitzalan, 10th Earl of Arundel.[52] Similarly, Victor's family is one of the most distinguished of that republic and his ancestors were counsellors and syndics. Percy's sister and Victor's adopted sister were both named Elizabeth. There are many other similarities, from Percy's usage of "Victor" as a pen name for Original Poetry by Victor and Cazire, a collection of poetry he wrote with Elizabeth,[53] to Percy's days at Eton, where he had "experimented with electricity and magnetism as well as with gunpowder and numerous chemical reactions," and the way in which Percy's rooms at Oxford were filled with scientific equipment.[54][55]

Modern Prometheus

The Modern Prometheus is the novel's subtitle (though modern editions now drop it, only mentioning it in introduction).[56] Prometheus, in versions of Greek mythology, was the Titan who created humans in the image of the gods so that they could have a spirit breathed into them at the behest of Zeus.[57] Prometheus then taught humans to hunt, but after he tricked Zeus into accepting "poor-quality offerings" from humans, Zeus kept fire from humankind. Prometheus took back the fire from Zeus to give to humanity. When Zeus discovered this, he sentenced Prometheus to be eternally punished by fixing him to a rock of Caucasus, where each day an eagle pecked out his liver, only for the liver to regrow the next day because of his immortality as a god.

As a Pythagorean, or believer in An Essay on Abstinence from Animal Food, as a Moral Duty by Joseph Ritson,[58] Mary Shelley saw Prometheus not as a hero but rather as something of a devil, and blamed him for bringing fire to humanity and thereby seducing the human race to the vice of eating meat.[59] Percy wrote several essays on what became known as vegetarianism including A Vindication of Natural Diet.[58]

Byron was particularly attached to the play Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus, and Percy Shelley soon wrote his own Prometheus Unbound (1820). The term "Modern Prometheus" was derived from Immanuel Kant who described Benjamin Franklin as the "Prometheus of modern times" in reference to his experiments with electricity.[60]

Publication

Shelley completed her writing in April/May 1817, and Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus was published on 1 January 1818[61] by the small London publishing house Lackington, Hughes, Harding, Mavor, & Jones.[62][63] It was issued anonymously, with a preface written for Mary by Percy Bysshe Shelley and with a dedication to philosopher William Godwin, her father. It was published in an edition of just 500 copies in three volumes, the standard "triple-decker" format for 19th-century first editions.

A French translation (Frankenstein: ou le Prométhée Moderne, translated by Jules Saladin) appeared as early as 1821. The second English edition of Frankenstein was published on 11 August 1823 in two volumes (by G. and W. B. Whittaker) following the success of the stage play Presumption; or, the Fate of Frankenstein by Richard Brinsley Peake.[64] This edition credited Mary Shelley as the book's author on its title page.

On 31 October 1831, the first "popular" edition in one volume appeared, published by Henry Colburn & Richard Bentley.[65] This edition was heavily revised by Mary Shelley, partially to make the story less radical. It included a lengthy new preface by the author, presenting a somewhat embellished version of the genesis of the story. This edition is the one most widely published and read now, although a few editions follow the 1818 text.[66] Some scholars prefer the original version, arguing that it preserves the spirit of Mary Shelley's vision (see Anne K. Mellor's "Choosing a Text of Frankenstein to Teach" in the W. W. Norton Critical edition).

Reception

Frankenstein has been both well received and disregarded since its anonymous publication in 1818. Critical reviews of that time demonstrate these two views, along with confused speculation as to the identity of the author. Walter Scott, writing in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, praises the novel as an "extraordinary tale, in which the author seems to us to disclose uncommon powers of poetic imagination," although he was less convinced about the way in which the monster gains knowledge about the world and language.[67] La Belle Assemblée described the novel as "very bold fiction"[68] and the Edinburgh Magazine and Literary Miscellany hoped to see "more productions ... from this author".[69] On the other hand, John Wilson Croker, writing anonymously in the Quarterly Review, although conceding that "the author has powers, both of conception and language," described the book as "a tissue of horrible and disgusting absurdity."[70]

In two other reviews where the author is known as the daughter of William Godwin, the criticism of the novel makes reference to the feminine nature of Mary Shelley. The British Critic attacks the novel's flaws as the fault of the author: "The writer of it is, we understand, a female; this is an aggravation of that which is the prevailing fault of the novel; but if our authoress can forget the gentleness of her sex, it is no reason why we should; and we shall therefore dismiss the novel without further comment".[71] The Literary Panorama and National Register attacks the novel as a "feeble imitation of Mr. Godwin's novels" produced by the "daughter of a celebrated living novelist."[72] Despite these reviews, Frankenstein achieved an almost immediate popular success. It became widely known, especially through melodramatic theatrical adaptations—Mary Shelley saw a production of Presumption; or The Fate of Frankenstein, a play by Richard Brinsley Peake, in 1823.

Critical reception of Frankenstein has been largely positive since the mid-20th century.[73] Major critics such as M. A. Goldberg and Harold Bloom have praised the "aesthetic and moral" relevance of the novel,[74] although there have also been critics, such as Germaine Greer, who criticized the novel for technical and narrative defects (who claimed it has three narrators who speak in the same way).[75] In more recent years the novel has become a popular subject for psychoanalytic and feminist criticism: Lawrence Lipking states: "[E]ven the Lacanian subgroup of psychoanalytic criticism, for instance, has produced at least half a dozen discrete readings of the novel".[76] Frankenstein has frequently been recommended on Five Books, with literary scholars, psychologists, novelists, and historians citing it as an influential text.[77] Today, the novel is generally considered to be a landmark work as one of the greatest Romantic and Gothic novels, as well as one of the first science fiction novels.[78]

Film director Guillermo del Toro describes Frankenstein as "the quintessential teenage book", noting that the feelings that "You don't belong. You were brought to this world by people that don't care for you and you are thrown into a world of pain and suffering, and tears and hunger" are an important part of the story. He adds that "it's an amazing book written by a teenage girl. It's mind-blowing."[79] Professor of philosophy Patricia MacCormack says that the Creature addresses the most fundamental human questions: "It's the idea of asking your maker what your purpose is. Why are we here, what can we do?"[79]

On 5 November 2019, BBC News listed Frankenstein on its list of the 100 most influential novels.[80] In 2021, it was one of six classic science fiction novels by British authors selected by Royal Mail to feature on a series of UK postage stamps.[81]

Films, plays, and television

The 1931 film Frankenstein is considered one of the most prominent cinematic portrayals of Frankenstein with Boris Karloff playing the lead character.[82]

See also

- Frankenstein authorship question

- Frankenstein argument

- Frankenstein complex

- Frankenstein in Baghdad

- Frankenstein in popular culture

- John Murray Spear

- Golem

- Homunculus

- List of dreams

Notes

- This seems to mean Johann Konrad Dippel (1673–1734), one century before (not two). For Dippel's experiments and the possibility of connection to Frankenstein see the Dippel article.

References

- Stableford, Brian (1995). "Frankenstein and the Origins of Science Fiction". In Seed, David (ed.). Anticipations: Essays on Early Science Fiction and its Precursors. Syracuse University Press. pp. 47–49. ISBN 978-0815626404. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- Hobbler, Dorthy and Thomas. The Monsters: Mary Shelley and the Curse of Frankenstein. Back Bay Books; 20 August 2007.

- Garrett, Martin. Mary Shelley. Oxford University Press, 2002

- Seymour, Miranda. Mary Shelley. Atlanta, GA: Grove Press, 2002. pp. 110–11

- McGasko, Joe. "Her 'Midnight Pillow': Mary Shelley and the Creation of Frankenstein". Biography. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- Shelley, Mary. Paragraphs 11–13, "Introduction" Frankenstein (1831 edition) Archived 2014-01-06 at the Wayback Machine Gutenberg

- The Detached Retina: Aspects of SF and Fantasy by Brian Aldiss (1995), p. 78.

- Bergen Evans, Comfortable Words, New York: Random House, 1957

- Bryan Garner, A Dictionary of Modern American Usage, New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of American English, Merriam-Webster: 2002.

- "Journal 6 December—Very Unwell. Shelley & Clary walk out, as usual, to heaps of places ... A letter from Hookham to say that Harriet has been brought to bed of a son and heir. Shelley writes a number of circular letters on this event, which ought to be ushered in with ringing of bells, etc., for it is the son of his wife." Quoted in Spark, 39.

- Lepore, Jill (5 February 2018). "The Strange and Twisted Life of "Frankenstein"". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- History.com editors. "Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein" is published". History.com. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

{{cite web}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - "Frankenstein: Penetrating the Secrets of Nature: The Birth of Frankenstein". www.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Badalamenti, Anthony (Fall 2006). "Why did Mary Shelley Write Frankenstein". Journal of Religion and Health. 45 (3): 419–39. doi:10.1007/s10943-006-9030-0. JSTOR 27512949. S2CID 37615140.

- "Pollin, "Philosophical and Literary Sources"". knarf.english.upenn.edu. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- Pollin, Burton (Spring 1965). "Philosophical and Literary Sources of Frankenstein". Comparative Literature. 17 (2): 97–108. doi:10.2307/1769997. JSTOR 1769997.

- Douthwaite, "The Frankenstein of the French Revolution" chapter 2 of The Frankenstein of 1790 and other Lost Chapters from Revolutionary France (Frankenstein of 1790 and other Lost Chapters from Revolutionary France Archived 16 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 2012).

- Ruston, Sharon (25 November 2015). "The Science of Life and Death in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein". The Public Domain Review. Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- "Lind, James (1736-1812) on JSTOR". plants.jstor.org. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Marshall, Alan (January 2020). "Did a Volcanic Eruption in Indonesia Really Lead to the Creation of Frankenstein?". The Conversation.

- Sunstein, 118.

- Dr. John Polidori, "The Vampyre" 1819, The New Monthly Magazine and Universal Register; London: H. Colburn, 1814–1820. Vol. 1, No. 63.

- paragraph 7, Introduction, Frankenstein 1831 edition

- paragraph 8, Introduction, Frankenstein 1831 edition

- paragraph 10, Introduction, Frankenstein 1831 edition

- Quoted in Spark, 157, from Mary Shelley's introduction to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein.

- Radford, Tim, Frankenstein's hour of creation identified by astronomers Archived 2 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, Sunday 25 September 2011 (retrieved 5 January 2014)

- Bennett, An Introduction, 30–31; Sunstein, 124.

- Sunstein, 117.

- Hay, 103.

- Lepore, Jill (5 February 2018). "The Strange and Twisted Life of 'Frankenstein'". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- Kennedy, Mave (26 February 2018). "'A 200-year-old secret': plaque to mark Bath's hidden role in Frankenstein". theguardian.com. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Bennett, Betty T. Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley: An Introduction, pp. 36–42. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

- "OX.ac.uk". Bodley.ox.ac.uk. 15 December 2009. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- "Shelley's Ghost – Reshaping the image of a literary family". shelleysghost.bodleian.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- Mary Shelley, with Percy Shelley (2008). Charles E. Robinson (ed.). The Original Frankenstein. Oxford: Bodleian Library. ISBN 978-1-851-24396-9. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

- Frankenstein:Celluloid Monster Archived 15 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine at the National Library of Medicine website of the (U.S.) National Institutes of Health

- "Frankenstein: Penetrating the Secrets of Nature / Exhibit Text" (PDF). National Library of Medicine and ALA Public Programs Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 December 2006. Retrieved 31 December 2007. from the travelling exhibition Frankenstein: Penetrating the Secrets of Nature Archived 9 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Shelley, Mary (1818). Frankenstein (1 ed.).

- John Milton, Paradise Lost (X. 743–45)

- Author's Digest: The World's Great Stories in Brief, by Rossiter Johnson, 1908

- The Reef, p. 96.

- This illustration is reprinted in the frontispiece to the 2008 edition of Frankenstein Archived 7 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Gray, Paul (23 July 1979). "Books: The Man-Made Monster". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- zapomniana, Historia (24 January 2016). "Afera grabarzy z Frankenstein". Archived from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- Florescu 1996, pp. 48–92.

- Day, A.J. (2005). Fantasmagoriana (Tales of the Dead). Fantasmagoriana Press. pp. 149–51. ISBN 978-1-4116-5291-0.

- Heléne, Jörg (12 September 2016). "Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, Castle Frankenstein and the alchemist Johann Conrad Dippel". Darmstadt. Archived from the original on 7 October 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- "Wade, Phillip. "Shelley and the Miltonic Element in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein." Milton and the Romantics, 2 (December, 1976), 23–25". Archived from the original on 14 April 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- Jones 1952, pp. 496–97.

- Percy Shelley#Ancestry

- Sandy, Mark (20 September 2002). "Original Poetry by Victor and Cazire". The Literary Encyclopedia. The Literary Dictionary Company. Archived from the original on 8 November 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- "Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822)". Romantic Natural History. Department of English, Dickinson College. Archived from the original on 16 August 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- Goulding, Christopher (2002). "The real Doctor Frankenstein?". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 95 (5): 257–259. doi:10.1177/014107680209500514. ISSN 0141-0768. PMC 1279684. PMID 11983772.

- For example, the Longman study edition published in India in 2007 by Pearson Education

- In the best-known versions of the Prometheus story, by Hesiod and Aeschylus, Prometheus merely brings fire to humankind, but in other versions, such as several of Aesop's fables (See in particular Fable 516), Sappho (Fragment 207), and Ovid's Metamorphoses, Prometheus is the actual creator of humanity.

- Morton, Timothy (21 September 2006). The Cambridge Companion to Shelley. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139827072.

- (Leonard Wolf, p. 20).

- RoyalSoc.ac.uk Archived 12 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine "Benjamin Franklin in London." The Royal Society. Retrieved 8 August 2007.

- Robinson, Charles (1996). The Frankenstein Notebooks: A Facsimile Edition. Vol. 1. Garland Publishing, Inc. p. xxv. Archived from the original on 16 March 2017. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

She began that novel as Mary Godwin in June 1816 when she was eighteen years old, she finished it as Mary Shelley in April/May 1817 when she was nineteen . . . and she published it anonymously on 1 January 1818 when she was twenty.

- Bennett, Betty T. Mary Wollstonecraft. Shelley: An Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998

- D. L. Macdonald and Kathleen Scherf, "A Note on the Text", Frankenstein, 2nd ed., Peterborough: Broadview Press, 1999.

- Wollstonecraft Shelley, Mary (2000). Frankenstein. Bedford Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 978-0312227623.

- See forward to Barnes and Noble classic edition.

- The edition published by Forgotten Books is the original text, as is the "Ignatius Critical Edition". Vintage Books has an edition presenting both versions.

- Scott, Walter (March 1818). "Remarks on Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus; A Novel". Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine: 613–620. Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. 3 vols. 12mo. Lackington and Co". La Belle Assemblée. New Series. 1 February 1818. pp. 139–142. Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "Review – Frankenstein". The Edinburgh Magazine and Literary Miscellany. New Series. March 1818. pp. 249–253.

- "Review of Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus". The Quarterly Review. 18: 379–85. January 1818. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- "Art. XII. Frankenstein: or the Modern Prometheus. 3 vols. 12mo. 16s. 6d. Lackington and Co. 1818". The British Critic. New Series. 9: 432–438. April 1818. Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "Frankenstein; or, the modern Prometheus. 3 vols. Lackington and Co. 1818". The Literary Panorama and National Register. New Series. 8: 411–414. June 1818. Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "Enotes.com". Enotes.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- "KCTCS.edu". Octc.kctcs.edu. Archived from the original on 15 November 2004. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- Germaine Greer (9 April 2007). "Yes, Frankenstein really was written by Mary Shelley. It's obvious – because the book is so bad". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- L. Lipking. Frankenstein the True Story; or Rousseau Judges Jean-Jacques. (Published in the Norton critical edition. 1996)

- Five Books. "Frankenstein by Mary Shelley | Five Books Expert Reviews". Five Books. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- UTM.edu Archived 3 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine Lynn Alexander, Department of English, University of Tennessee at Martin. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- "Frankenstein: Behind the monster smash". BBC. 1 January 2018. Archived from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- "100 'most inspiring' novels revealed by BBC Arts". BBC News. 5 November 2019. Archived from the original on 8 November 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

The reveal kickstarts the BBC's year-long celebration of literature.

- "Stamps to feature original artworks celebrating classic science fiction novels". Yorkpress.co.uk. 9 April 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- Anderson, John (25 January 2022). "'Boris Karloff: The Man Behind the Monster' Review: A Very Different Creature". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

Sources

- Aldiss, Brian W. "On the Origin of Species: Mary Shelley". Speculations on Speculation: Theories of Science Fiction. Eds. James Gunn and Matthew Candelaria. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow, 2005.

- Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Bann, Stephen, ed. "Frankenstein": Creation and Monstrosity. London: Reaktion, 1994.

- Behrendt, Stephen C., ed. Approaches to Teaching Shelley's "Frankenstein". New York: MLA, 1990.

- Bennett, Betty T. and Stuart Curran, eds. Mary Shelley in Her Times. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

- Bennett, Betty T. Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley: An Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8018-5976-X.

- Bohls, Elizabeth A. "Standards of Taste, Discourses of 'Race', and the Aesthetic Education of a Monster: Critique of Empire in Frankenstein". Eighteenth-Century Life 18.3 (1994): 23–36.

- Botting, Fred. Making Monstrous: "Frankenstein", Criticism, Theory. New York: St. Martin's, 1991.

- Chapman, D. That Not Impossible She: A study of gender construction and Individualism in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, UK: Concept, 2011. ISBN 978-1480047617

- Clery, E. J. Women's Gothic: From Clara Reeve to Mary Shelley. Plymouth: Northcote House, 2000.

- Conger, Syndy M., Frederick S. Frank, and Gregory O'Dea, eds. Iconoclastic Departures: Mary Shelley after "Frankenstein": Essays in Honor of the Bicentenary of Mary Shelley's Birth. Madison, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1997.

- Donawerth, Jane. Frankenstein's Daughters: Women Writing Science Fiction. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1997.

- Douthwaite, Julia V. "The Frankenstein of the French Revolution," chapter two of The Frankenstein of 1790 and other Lost Chapters from Revolutionary France Archived 16 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

- Dunn, Richard J. "Narrative Distance in Frankenstein". Studies in the Novel 6 (1974): 408–17.

- Eberle-Sinatra, Michael, ed. Mary Shelley's Fictions: From "Frankenstein" to "Falkner". New York: St. Martin's Press, 2000.

- Ellis, Kate Ferguson. The Contested Castle: Gothic Novels and the Subversion of Domestic Ideology. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989.

- Florescu, Radu (1996). In Search of Frankenstein: Exploring the Myths Behind Mary Shelley's Monster (2nd ed.). London: Robson Books. ISBN 978-1-861-05033-5.

- Forry, Steven Earl. Hideous Progenies: Dramatizations of "Frankenstein" from Mary Shelley to the Present. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990.

- Freedman, Carl. "Hail Mary: On the Author of Frankenstein and the Origins of Science Fiction". Science Fiction Studies 29.2 (2002): 253–64.

- Gigante, Denise. "Facing the Ugly: The Case of Frankenstein". ELH 67.2 (2000): 565–87.

- Gilbert, Sandra and Susan Gubar. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979.

- Hay, Daisy "Young Romantics" (2010): 103.

- Heffernan, James A. W. "Looking at the Monster: Frankenstein and Film". Critical Inquiry 24.1 (1997): 133–58.

- Hodges, Devon. "Frankenstein and the Feminine Subversion of the Novel". Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature 2.2 (1983): 155–64.

- Hoeveler, Diane Long. Gothic Feminism: The Professionalization of Gender from Charlotte Smith to the Brontës. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1998.

- Holmes, Richard. Shelley: The Pursuit. 1974. London: Harper Perennial, 2003. ISBN 0-00-720458-2.

- Jones, Frederick L. (1952). "Shelley and Milton". Studies in Philology. 49 (3): 488–519. JSTOR 4173024.

- Knoepflmacher, U. C. and George Levine, eds. The Endurance of "Frankenstein": Essays on Mary Shelley's Novel. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979.

- Lew, Joseph W. "The Deceptive Other: Mary Shelley's Critique of Orientalism in Frankenstein". Studies in Romanticism 30.2 (1991): 255–83.

- London, Bette. "Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, and the Spectacle of Masculinity". PMLA 108.2 (1993): 256–67.

- Mellor, Anne K. Mary Shelley: Her Life, Her Fiction, Her Monsters. New York: Methuen, 1988.

- Michaud, Nicolas, Frankenstein and Philosophy: The Shocking Truth, Chicago: Open Court, 2013.

- Miles, Robert. Gothic Writing 1750–1820: A Genealogy. London: Routledge, 1993.

- Milner, Andrew. Literature, Culture and Society. London: Routledge, 2005, ch.5.

- O'Flinn, Paul. "Production and Reproduction: The Case of Frankenstein". Literature and History 9.2 (1983): 194–213.

- Poovey, Mary. The Proper Lady and the Woman Writer: Ideology as Style in the Works of Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Shelley, and Jane Austen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

- Rauch, Alan. "The Monstrous Body of Knowledge in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein". Studies in Romanticism 34.2 (1995): 227–53.

- Selbanev, Xtopher. "Natural Philosophy of the Soul", Western Press, 1999.

- Schor, Esther, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Mary Shelley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Scott, Grant F. (April–June 2012). "Victor's Secret: Queer Gothic in Lynd Ward's Illustrations to Frankenstein (1934)". Word & Image. 28 (2): 206–32. doi:10.1080/02666286.2012.687545. S2CID 154238300.

- Smith, Johanna M., ed. Frankenstein. Case Studies in Contemporary Criticism. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 1992.

- Spark, Muriel. Mary Shelley. London: Cardinal, 1987. ISBN 0-7474-0318-X.

- Stableford, Brian. "Frankenstein and the Origins of Science Fiction". Anticipations: Essays on Early Science Fiction and Its Precursors. Ed. David Seed. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1995.

- Sunstein, Emily W. Mary Shelley: Romance and Reality. 1989. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-8018-4218-2.

- Tropp, Martin. Mary Shelley's Monster. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1976.

- Veeder, William. Mary Shelley & Frankenstein: The Fate of Androgyny. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986.

- Williams, Anne. The Art of Darkness: A Poetics of Gothic. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Further reading

- Richard Holmes, "Out of Control" (review of Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, Or, The Modern Prometheus: Annotated for Scientists, Engineers, and Creators of All Kinds, edited by David H. Guston, Ed Finn, and Jason Scott Robert, MIT Press, 277 pp.; and Mary Shelley, The New Annotated Frankenstein, edited and with a foreword and notes by Leslie S. Klinger, Liveright, 352 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXIV, no. 20 (21 December 2017), pp. 38, 40–41.

1818 text

- Shelley, Mary Frankenstein: 1818 text (Oxford University Press, 2009). Edited with an introduction and notes by Marilyn Butler.

1831 text

- Fairclough, Peter (ed.) Three Gothic Novels: Walpole / Castle of Otranto, Beckford / Vathek, Mary Shelley / Frankenstein (Penguin English Library, 1968). With an introductory essay by Mario Praz.

- Shelley, Mary Frankenstein (Oxford University Press, 2008). Edited with an introduction and notes by M. K. Joseph.

Differences between 1818 and 1831 text

Shelley made several alterations in the 1831 edition including:

- The epigraph from Milton's Paradise Lost found in the 1818 original has been removed.

- Chapter one is expanded and split into two chapters.

- Elizabeth's origin is changed from Victor's cousin to being an orphan.

- Victor is portrayed more sympathetically in the original text. In the 1831 edition however, Shelley is critical of his decisions and actions.

- Shelley removed many references to scientific ideas which were popular around the time she wrote the 1818 edition of the book.

- Characters in the 1831 version have some dialogue removed entirely while others receive new dialogue.

External links

- Frankenstein at Standard Ebooks

- Frankenstein 1831 edition at Project Gutenberg

- Frankenstein 1818 edition at Project Gutenberg

Frankenstein public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Frankenstein public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley Chronology and Resource Site

- "On Frankenstein", review by Percy Bysshe Shelley

- Volume one and Volume two of Shelley's notebooks with her handwritten draft of Frankenstein