Hesse

Hesse (/hɛs/,[4] US also /ˈhɛsə, ˈhɛsi/,[5] Hessian dialect: [ˈhɛzə]) or Hessia (UK: /ˈhɛsiə/, US: /ˈhɛʃə/; German: Hessen [ˈhɛsn̩] (![]() listen)), officially the State of Hessen (German: Land Hessen), is a state in Germany. Its capital city is Wiesbaden, and the largest urban area is Frankfurt. Two other major historic cities are Darmstadt and Kassel. With an area of 21,114.73 square kilometers and a population of just over six million, it ranks seventh and fifth, respectively, among the sixteen German states. Frankfurt Rhine-Main, Germany's second-largest metropolitan area (after Rhine-Ruhr), is mainly located in Hesse.

listen)), officially the State of Hessen (German: Land Hessen), is a state in Germany. Its capital city is Wiesbaden, and the largest urban area is Frankfurt. Two other major historic cities are Darmstadt and Kassel. With an area of 21,114.73 square kilometers and a population of just over six million, it ranks seventh and fifth, respectively, among the sixteen German states. Frankfurt Rhine-Main, Germany's second-largest metropolitan area (after Rhine-Ruhr), is mainly located in Hesse.

State of Hessen

Land Hessen | |

|---|---|

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Anthem: Hessenlied (German) "Song of Hesse" | |

| |

| Coordinates: 50°36′29″N 9°01′42″E | |

| Country | Germany |

| Capital | Wiesbaden |

| Largest city | Frankfurt |

| Government | |

| • Body | Landtag of Hesse |

| • Minister-President | Boris Rhein (CDU) |

| • Governing parties | CDU / Greens |

| • Bundesrat votes | 5 (of 69) |

| • Bundestag seats | 50 (of 736) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 21,114.73 km2 (8,152.44 sq mi) |

| Population (2017-12-31)[1] | |

| • Total | 6,243,262 |

| • Density | 300/km2 (770/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Hessian |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | DE-HE |

| GRP (nominal) | €294 billion (2019)[2] |

| GRP per capita | €47,000 (2019) |

| NUTS Region | DE7 |

| HDI (2018) | 0.955[3] very high · 6th of 16 |

| Website | www.hessen.de |

As a cultural region, Hesse also includes the area known as Rhenish Hesse (Rheinhessen) in the neighbouring state of Rhineland-Palatinate.[6]

Name

The German name Hessen, like the names of other German regions (Schwaben "Swabia", Franken "Franconia", Bayern "Bavaria", Sachsen "Saxony"), derives from the dative plural form of the name of the inhabitants or eponymous tribe, the Hessians (Hessen, singular Hesse). The geographical name represents a short equivalent of the older compound name Hessenland ("land of the Hessians"). The Old High German form of the name is recorded as Hessun (dative plural of Hessi); in Middle Latin it appears as Hassia, Hessia, Hassonia. The name of the Hessians ultimately continues the tribal name of the Chatti.[7] The ancient name Chatti by the 7th century is recorded as Chassi, and from the 8th century as Hassi or Hessi.[8]

An inhabitant of Hesse is called a "Hessian" (German: Hesse (masculine), plural Hessen, or Hessin (feminine), plural Hessinnen). The American English term "Hessian" for 18th-century British auxiliary troops originates with Landgrave Frederick II of Hesse-Kassel hiring out regular army units to the government of Great Britain to fight in the American Revolutionary War.

The English form Hesse was in common use by the 18th century, first in the hyphenated names of the states of Hesse-Cassel and Hesse-Darmstadt, but the latinate form Hessia remained in common English usage well into the 19th century.[9][10][11]

The European Commission uses the German form Hessen, even in English-language contexts, due to the policy of leaving regional names untranslated.[12]

The synthetic element hassium, number 108 on the periodic table, was named after the state of Hesse in 1997, following a proposal of 1992.[13]

History

The territory of Hesse was delineated only in 1945, as Greater Hesse, under American occupation. It corresponds only loosely to the medieval Landgraviate of Hesse. In the 19th century, prior to the unification of Germany, the territory of what is now Hesse comprised the territories of Grand Duchy of Hesse, the Duchy of Nassau, the free city of Frankfurt and the Electorate of Hesse (also known as Hesse-Cassel).

Early history

The Central Hessian region was inhabited in the Upper Paleolithic. Finds of tools in southern Hesse in Rüsselsheim suggest the presence of Pleistocene hunters about 13,000 years ago. A fossil hominid skull that was found in northern Hesse, just outside the village of Rhünda, has been dated at 12,000 years ago. The Züschen tomb (German: Steinkammergrab von Züschen, sometimes also Lohne-Züschen) is a prehistoric burial monument, located between Lohne and Züschen, near Fritzlar, Hesse, Germany. Classified as a gallery grave or a Hessian-Westphalian stone cist (hessisch-westfälische Steinkiste), it is one of the most important megalithic monuments in Central Europe. Dating to c. 3000 BC, it belongs to the Late Neolithic Wartberg culture.

An early Celtic presence in what is now Hesse is indicated by a mid-5th-century BC La Tène-style burial uncovered at Glauberg. The region was later settled by the Germanic Chatti tribe around the 1st century BC, and the name Hesse is a continuation of that tribal name.

The ancient Romans had a military camp in Dorlar, and in Waldgirmes directly on the eastern outskirts of Wetzlar was a civil settlement under construction. Presumably, the provincial government for the occupied territories of the right bank of Germania was planned at this location. The governor of Germania, at least temporarily, likely had resided here. The settlement appears to have been abandoned by the Romans after the devastating Battle of the Teutoburg Forest failed in the year AD 9. The Chatti were also involved in the Revolt of the Batavi in AD 69.

Hessia, from the early 7th century on, served as a buffer between areas dominated by the Saxons (to the north) and the Franks, who brought the area to the south under their control in the early sixth century and occupied Thuringia (to the east) in 531.[14] Hessia occupies the northwestern part of the modern German state of Hesse; its borders were not clearly delineated. Its geographic center is Fritzlar; it extends in the southeast to Hersfeld on the river Fulda, in the north to past Kassel and up to the rivers Diemel and Weser. To the west, it occupies the valleys of the rivers Eder and Lahn (the latter until it turns south). It measured roughly 90 kilometers north–south, and 80 north-west.[15]

The area around Fritzlar shows evidence of significant pagan belief from the 1st century on. Geismar was a particular focus of such activity; it was continuously occupied from the Roman period on, with a settlement from the Roman period, which itself had a predecessor from the 5th century BC. Excavations have produced a horse burial and bronze artifacts. A possible religious cult may have centered on a natural spring in Geismar, called Heilgenbron; the name "Geismar" (possibly "energetic pool") itself may be derived from that spring. The village of Maden, Gudensberg, now a part of Gudensberg near Fritzlar and less than ten miles from Geismar, was likely an ancient religious center; the basaltic outcrop of Gudensberg is named after Wodan, and a two-meter tall quartzite megalith called the Wotanstein is at the center of the village.[16]

By the mid-7th century, the Franks had established themselves as overlords, which is suggested by archeological evidence of burials, and they built fortifications in various places, including Christenberg.[17] By 690, they took direct control over Hessia, apparently to counteract expansion by the Saxons, who built fortifications in Gaulskopf and Eresburg across the river Diemel, the northern boundary of Hessia. The Büraburg (which already had a Frankish settlement in the sixth century[18]) was one of the places the Franks fortified to resist the Saxon pressure, and according to John-Henry Clay, the Büraburg was "probably the largest man-made construction seen in Hessia for at least seven hundred years". Walls and trenches totaling one kilometer in length were made, and they enclosed "8 hectares of a spur that offered a commanding view over Fritzlar and the densely-populated heart of Hessia".[19]

Following Saxon incursions into Chattish territory in the 7th century, two gaue had been established; a Frankish one, comprising an area around Fritzlar and Kassel, and a Saxonian one. In the 9th century, the Saxon Hessengau also came under the rule of the Franconians.

Holy Roman Empire

From 962 the land which would become Hesse was part of the Holy Roman Empire. In the 10th and 11th centuries it was mostly encompassed by the Western or Rhenish part of the stem duchy of Franconia.

In the 12th century, Hessengau passed to the Landgraviate of Thuringia. As a result of the War of the Thuringian Succession (1247–1264) the former Thuringian lands were partitioned between the Wettin Margraviate of Meissen, which gained Thuringia proper, and the new Landgraviate of Hesse, which remained with the Ludovingians. From that point on the Ludovingian coat of arms came to represent both Thuringia and Hesse.

It rose to prominence under Landgrave Philip the Magnanimous, who was one of the leaders of German Protestantism. After Philip's death in 1567, the territory was divided among his four sons from his first marriage (Philip was a bigamist) into four lines: Hesse-Kassel (or Hesse-Cassel), Hesse-Darmstadt, Hesse-Rheinfels, and the also previously existing Hesse-Marburg. As the latter two lines died out quite quickly (1583 and 1605, respectively), Hesse-Kassel and Hesse-Darmstadt were the two core states within the Hessian lands. Several collateral lines split off during the centuries, such as in 1622, when Hesse-Homburg split off from Hesse-Darmstadt, and in 1760 when Hesse-Hanau split off from Hesse-Kassel. In the late 16th century, Kassel adopted Calvinism, while Darmstadt remained Lutheran and consequently the two lines often found themselves on opposing sides of conflicts, most notably in the disputes over Hesse-Marburg and in the Thirty Years' War, when Darmstadt fought on the side of the Emperor, while Kassel sided with Sweden and France.

The Landgrave Frederick II (1720–1785) ruled Hesse-Kassel as a benevolent despot, from 1760 to 1785. He combined Enlightenment ideas with Christian values, cameralist plans for central control of the economy, and a militaristic approach toward diplomacy.[20] He funded the depleted treasury of the poor government by loaning 19,000 soldiers in complete military formations to Great Britain to fight in North America during the American Revolutionary War, 1776–1783. These soldiers, commonly known as Hessians, fought under the British flag. The British used the Hessians in several conflicts, including in the Irish Rebellion of 1798. For further revenue, the soldiers were loaned to other places as well. Most were conscripted, with their pay going to the Landgrave.

Modern history

French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars

In 1789 the French Revolution began and in 1794, during the War of the First Coalition, the French Republic occupied the Left Bank of the Rhine, including part of Lower Katzenelnbogen (Niedergrafschaft Katzenelnbogen, Hesse-Kassel's part of the former County of Katzenelnbogen which was held by the appanage Hesse-Rotenburg). Emperor Francis II formally recognised the annexation of the Left Bank in the 1801 Treaty of Lunéville. This led in 1803 to the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss, a substantial reorganisation (mediatisation) of the states and territories of the Empire. Several exclaves of Mainz were mediatised to Hesse-Kassel and Hesse-Darmstadt, and Hesse-Darmstadt also gained the Duchy of Westphalia from Cologne, the parts of Worms on the right-bank of the Rhine, and the former Free City of Friedberg. Nassau-Weilburg gained the right-bank territories of Trier among other territories. Orange-Nassau gained the Prince-Bishopric of Fulda (as the Principality of Nassau-Orange-Fulda). The Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel was also elevated to the status of Prince-Elector (Kurfürst), with his state thereby becoming the Electorate of Hesse or Electoral Hesse (German: Kurhessen, Kur being the German-language term for the Empire's College of Electors).

In July 1806 Hesse-Darmstadt, Nassau-Weilburg, Nassau-Usingen, and the newly-merged Principality of Isenburg became founding members of Napoleon's Confederation of the Rhine. Hesse-Darmstadt expanded further in the resulting mediatisation, absorbing numerous small states (including Hesse-Homburg and much of the territory of the Houses of Solms, Erbach and Sayn-Wittgenstein). It was also elevated by Napoleon to the status of Grand Duchy, becoming the Grand Duchy of Hesse. Orange-Nassau, which refused to join the Confederation, lost Siegen, Dillenburg, Hadamar and Beilstein to Berg and Fulda to the Prince-Primate of the Confederation (and former Elector of Mainz) Karl Theodor von Dalberg; the remainder of its territory was merged with that of Nassau-Usingen and Nassau-Weilburg in August 1806 to form the Duchy of Nassau. Waldeck also joined the Confederation in 1807.

The Holy Roman Empire was dissolved in August 1806, rendering Hesse-Kassel's electoral privilege meaningless. Hesse-Kassel was occupied by the French in October 1806 and the remainder of Lower Katzenelnbogen was annexed to the French Empire as Pays réservé de Catzenellenbogen. The rest of its territory was annexed to the Kingdom of Westphalia in 1807; Hesse-Hanau (a secundogeniture of Hesse-Kassel) was annexed to the Grand Duchy of Frankfurt in 1810 along with the other territories held by the Prince-primate: Frankfurt, Fulda, Aschaffenburg and Wetzlar.

As a result of the German campaign of 1813 the Kingdom of Westphalia and the Grand Duchy of Frankfurt were dissolved and Hesse-Kassel and Hesse-Hanau were restored; Orange-Nassau was also restored in its territories previously lost to Berg.

As a result of the 1815 Congress of Vienna Hesse-Kassel gained Fulda (roughly the western third of the former Prince-Bishopric, the rest of which went to Bavaria and Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach) from Frankfurt and part of Isenburg, while several of its small northern exclaves were absorbed into Hanover, some small eastern areas were ceded to Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach and Lower Katzenelnbogen was ceded to Nassau. Hesse-Darmstadt lost the Duchy of Westphalia and the Sayn-Wittgensteiner lands to the Prussian Province of Westphalia but gained territory on the left bank of the Rhine centred on Mainz, which became known as Rhenish Hesse (Rheinhessen), and the remainder of Isenburg. Orange-Nassau, whose ruler was now also King William I of the Netherlands and Grand Duke of Luxembourg, was ceded to Prussia but most of its territory aside from Siegen was then ceded on to Nassau. Hesse-Homburg and the Free City of Frankfurt were also restored.

While the other former Electors had gained other titles, becoming either Kings or Grand Dukes, the Elector of Hesse-Kassel alone retained the anachronistic title of Prince-Elector; a request to be recognised as "King of the Chatti" (König der Katten) was rejected by the Congress.

Following the mediatisations and the Congress of Vienna significantly fewer states remained in the region that is now Hesse: the Hessian states, Nassau, Waldeck and Frankfurt. The Kingdoms of Prussia and Bavaria also held some territory in the region. The Congress also established the German Confederation, of which they all became members. Hesse-Hanau was (re-)absorbed into Hesse-Kassel in 1821.

German Empire

In the 1866 Austro-Prussian War the states of the region allied with Austria were defeated during the Campaign of the Main. Following Prussia's victory and dissolution of the German Confederation, Prussia annexed Electoral Hesse, Frankfurt, Hesse-Homburg, Nassau and small parts of Bavaria and the Grand Duchy of Hesse, which were then combined into the Province of Hesse-Nassau. The name Kurhessen survived, denoting the region around Kassel. The Grand Duchy of Hesse retained its autonomy in defeat because a greater part of the country was situated south of the river Main and it was feared that Prussian expansion beyond the Main might provoke France. However, Upper Hesse (German: Oberhessen: the parts of Hesse-Darmstadt north of the Main around the town of Gießen) was incorporated into the North German Confederation (Norddeutscher Bund), a tight federation of German states established by Prussia in 1867, while also remaining part of the Grand Duchy. In 1871, after France's defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, the whole of the Grand Duchy joined the German Empire.

Around the turn of the 20th century, Darmstadt was one of the centres of the Jugendstil. Until 1907, the Grand Duchy of Hesse used the Hessian red and white lion barry as its coat-of-arms.

Weimar and Nazi periods

The revolution of 1918 following the German defeat in WWI transformed Hesse-Darmstadt from a monarchy to a republic, which officially renamed itself the People's State of Hesse (Volksstaat Hessen). The parts of Hesse-Darmstadt on the left bank of the Rhine (Rhenish Hesse), as well as those right-bank areas of Hesse-Darmstadt and Hesse-Nassau within 30 km (19 mi) of Koblenz or Mainz were occupied by French troops until 1930 under the terms of the Versailles peace treaty that officially ended World War I in 1919. The Kingdom of Prussia became the Free State of Prussia, of which Hesse-Nassau remained a province.

In 1929 the Free State of Waldeck was dissolved and incorporated into Hesse-Nassau. In 1932 Wetzlar (Landkreis Wetzlar), formerly an exclave of the Prussian Rhine Province situated between Hesse-Nassau and the Grand Duchy's Upper Hesse, was transferred to Hesse-Nassau. The former Hessian exclave of Rinteln (Kreis Rinteln, the Hessian part of the former County of Schaumburg) was also detached and transferred to the Province of Hanover.

On 1 July 1944 the Prussian Province of Hesse-Nassau was formally divided into the provinces of Kurhessen and Nassau. At the same time the former Hessian Schmalkalden exclaves (Landkreis Herrschaft Schmalkalden), together with the Regierungsbezirk Erfurt of the Province of Saxony, were transferred to Thuringia. The territories of the new provinces did not directly correspond with their pre-1866 namesakes but rather with the associated NSDAP Gaue: Gau Electoral Hesse and Gau Hesse-Nassau (excluding the areas which were part of the People's State of Hesse).

Post-World War II

After World War II, the Hessian territory west of the Rhine was again occupied by France, while the rest of the region was part of the US occupation zone. On 17 September 1945 the Wanfried agreement adjusted the border between American-occupied Kurhessen and Soviet-occupied Thuringia. The United States proclaimed the state of Greater Hesse (Groß-Hessen) on 19 September 1945, out of the People's State of Hesse and most of what had been the Prussian Provinces of Kurhessen and Nassau. The French incorporated their parts of Hesse (Rhenish Hesse) and Nassau (as Regierungsbezirk Montabaur) into the newly founded state of Rhineland-Palatinate (Rheinland-Pfalz) on 30 August 1946.

On 4 December 1946, Greater Hesse was officially renamed Hessen.[21] Hesse in the 1940s received more than a million displaced ethnic Germans.

Due to its proximity to the Inner German border, Hesse became an important location of NATO installations in the 1950s, especially military bases of the US V Corps and United States Army Europe.

The first elected minister president of Hesse was Christian Stock, followed by Georg-August Zinn (both Social Democrats). The German Social Democrats gained an absolute majority in 1962 and pursued progressive policies with the so-called Großer Hessenplan. The CDU gained a relative majority in the 1974 elections, but the Social Democrats continued to govern in a coalition with the FDP. Hesse was first governed by the CDU under Walter Wallmann during 1987–1991, replaced by a SPD-Greens coalition under Hans Eichel during 1991–1999. From 1999, Hesse was governed by the CDU under Roland Koch (retired 2010) and Volker Bouffier (incumbent as of 2020). Frankfurt during the 1960s to 1990s developed into one of the major cities of West Germany. As of 2016, 12% of the total population of Hesse lived in the city of Frankfurt.

Geography

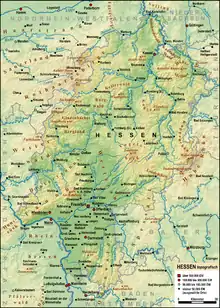

Situated in west-central Germany, the state of Hesse borders the German states of Lower Saxony, Thuringia, Bavaria, Baden-Württemberg, Rhineland-Palatinate, and North Rhine-Westphalia (starting in the north and proceeding clockwise).

Most of the population of Hesse lives in the southern part, in the Rhine Main Area. The principal cities of the area include Frankfurt am Main, Wiesbaden, Darmstadt, Offenbach, Hanau, Giessen, Wetzlar, and Limburg. Other major towns in Hesse are Fulda in the east, and Kassel and Marburg an der Lahn in the north. The densely populated Rhine-Main region is much better developed than the rural areas in the middle and northern parts of Hesse.

The most important rivers in Hesse are the Fulda and Eder in the north, the Lahn in the central part of Hesse, and the Main and Rhine in the south. The countryside is hilly and the numerous mountain ranges include the Rhön, the Westerwald, the Taunus, the Vogelsberg, the Knüll and the Spessart.

The Rhine borders Hesse on the southwest without running through the state. Only one oxbow lake—the so-called Stockstadt-Erfelder Altrhein—runs through Hesse. The mountain range between the rivers Main and the Neckar is called the Odenwald. The plain between the rivers Main, Rhine, and Neckar, and the Odenwald Mountains is called the Ried.

Hesse is the greenest state in Germany, as forest covers 42% of the state.[22]

Administration

Hesse is a unitary state governed directly by the Hessian government in the capital city Wiesbaden, partially through regional vicarious authorities called Regierungspräsidien. Municipal parliaments are, however, elected independently from the state government by the Hessian people. Local municipalities enjoy a considerable degree of home rule.

Districts

The state is divided into three administrative provinces (Regierungsbezirke): Kassel in the north and east, Gießen in the centre, and Darmstadt in the south, the latter being the most populous region with the Frankfurt Rhine-Main agglomeration in its central area. The administrative regions have no legislature of their own, but are executive agencies of the state government.

.svg.png.webp)

Hesse is divided into 21 districts (Kreise) and five independent cities, each with their own local governments. They are, shown with abbreviations as used on vehicle number plates:

- Bergstraße (Heppenheim) (HP)

- Darmstadt-Dieburg (Darmstadt) (DA, DI)

- Groß-Gerau (Groß-Gerau) (GG)

- Hochtaunuskreis (Bad Homburg) (HG, USI)

- Main-Kinzig-Kreis (Gelnhausen) (MKK, GN, HU, SLÜ)

- Main-Taunus-Kreis (Hofheim am Taunus) (MTK)

- Odenwaldkreis (Erbach) (ERB)

- Offenbach (Dietzenbach) (OF)

- Rheingau-Taunus-Kreis (Bad Schwalbach) (RÜD, SWA)

- Wetteraukreis (Friedberg) (FB, BÜD)

- Gießen (Gießen) (GI)

- Lahn-Dill-Kreis (Wetzlar) (LDK, DIL, WZ)

- Limburg-Weilburg (Limburg) (LM, WEL)

- Marburg-Biedenkopf (Marburg) (MR, BID)

- Vogelsbergkreis (Lauterbach) (VB)

- Fulda (Fulda) (FD)

- Hersfeld-Rotenburg (Bad Hersfeld) (HEF, ROF)

- Kassel (Kassel) (KS, HOG, WOH)

- Schwalm-Eder-Kreis (Homberg (Efze)) (HR, ZIG, FZ)

- Werra-Meißner-Kreis (Eschwege) (ESW, WIZ)

- Waldeck-Frankenberg (Korbach) (KB, FKB, WA)

Independent cities:

- Darmstadt (DA)

- Frankfurt am Main (F)

- Kassel (KS)

- Offenbach am Main (OF)

- Wiesbaden (WI)

Rhenish Hesse

The term "Rhenish Hesse" (German: Rheinhessen) refers to the part of the former Grand Duchy of Hesse-Darmstadt located west of the Rhine. It has not been part of the State of Hesse since 1946 due to divisions in the aftermath of World War II. This province is now part of the State of Rhineland-Palatinate. It is a hilly countryside largely devoted to vineyards; therefore, it is also called the "land of the thousand hills". Its larger towns include Mainz, Worms, Bingen, Alzey, Nieder-Olm, and Ingelheim. Many inhabitants commute to work in Mainz, Wiesbaden, or Frankfurt.

State symbols and politics

Hesse has been a parliamentary republic since 1918, except during Nazi rule (1933–1945). The German federal system has elements of exclusive federal competences, shared competences, and exclusive competences of the states. Hesse is famous for having a rather brisk style in its politics with the ruling parties being either the center-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) or the center-left Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). Due to the Hessian electoral laws, the biggest party normally needs a smaller coalition partner.

Head of state

As Hesse is a partly sovereign federated state, its constitution combines the offices of the head of state and head of government in one office called the Minister-President (German: Ministerpräsident) which is comparable to the office of a prime minister.

Most recent state election

In the 2018 state elections the two leading parties, CDU and SPD, lost 11.3% (7 seats) and 10.9% (8 seats) of the vote respectively. The Green party, a member of Hesse's previous governing coalition with CDU, gained 8.7% (16 seats). The largest gains during the election were made by Alternative for Germany (AfD) at 13.1%. As AfD had not passed the 5% threshold in the 2013 state election, this marked its first entry into the Hessian parliament (Hessischer Landtag). The two other parties also made gains. The major losses of the two leading parties (whose coalition made up the federal cabinet during the election) closely mirrors the results of the 2018 state elections in Bavaria. In the current parliament the conservative CDU holds 40 seats, the centre-left SPD and the leftist Green party each hold 29 seats, the right-wing AfD holds 19 seats, the liberal FDP party holds 11 seats and the socialist party Die Linke holds 9 seats.

Foreign affairs

As a member state of the German federation, Hesse does not have a diplomatic service of its own. However, Hesse operates representation offices in such foreign countries as the United States, China, Hungary, Cuba, Russia, Poland, and Iran. These offices are mostly used to represent Hessian interests in cultural and economic affairs. Hesse has also permanent representation offices in Berlin at the federal government of Germany and in Brussels at the institutions of the European Union.[23]

Flag and anthem

The flag colors of Hesse are red and white, which are printed on a Hessian sack. The Hessian coat of arms shows a lion rampant striped with red and white. The official anthem of Hesse is called "Hessenlied" ("Song of Hesse") and was written by Albrecht Brede (music) and Carl Preser (lyrics).[24]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 4,343,720 | — |

| 1955 | 4,577,198 | +1.05% |

| 1960 | 4,783,352 | +0.88% |

| 1965 | 5,170,449 | +1.57% |

| 1970 | 5,424,529 | +0.96% |

| 1975 | 5,549,823 | +0.46% |

| 1980 | 5,601,031 | +0.18% |

| 1985 | 5,529,413 | −0.26% |

| 1990 | 5,763,310 | +0.83% |

| 1995 | 6,009,913 | +0.84% |

| 2000 | 6,068,129 | +0.19% |

| 2005 | 6,092,354 | +0.08% |

| 2010 | 6,067,021 | −0.08% |

| 2015 | 6,176,172 | +0.36% |

| 2018 | 6,265,809 | +0.48% |

| source:[25] | ||

| Significant foreign resident populations[26] | |

| Nationality | Population (31 December 2020) |

|---|---|

| 155,250 | |

| 81,760 | |

| 75,525 | |

| 74,955 | |

| 56,840 | |

| 55,365 | |

| 50,300 | |

| 39,650 | |

| 36,655 | |

| 29,865 | |

Hesse has a population of over 6 million,[27] nearly 4 million of which is concentrated in the Rhein-Main region (German: Rhein-Main Gebiet) in the south of the state, an area that includes the most populous city, Frankfurt am Main, the capital Wiesbaden, and Darmstadt and Offenbach.[28] The population of Hesse is predicted to shrink by 4.3% by 2030, with the biggest falls in the north of the state, especially in the area around the city of Kassel. Frankfurt is the fastest growing city with a predicted rise in population of 4.8% by 2030.[29] Frankfurt's growth is driven by its importance as a financial centre and it receives immigrants from all over the world: in 2015 over half of the city's population had an immigrant background.[30]

Vital statistics

Source:[31]

- Births January–March 2017 =

14,537

14,537 - Births January–March 2018 =

14,202

14,202 - Deaths January–March 2017 =

19,289

19,289 - Deaths January–March 2018 =

18,831

18,831 - Natural growth January–March 2017 =

−4,752

−4,752 - Natural growth January–March 2018 =

−4,629

−4,629

Language

Three different languages or dialect groups are spoken in Hesse: The Far North is part of the Low Saxon language area, divided into a tiny Eastphalian and a larger Westphalian dialect area. Most of Hesse belongs to the West Middle German dialect zone. There is some disagreement as to whether all Hessian dialects south of the Benrath line may be subsumed under one dialect group: Rhine Franconian, or whether most dialects should be regarded as a dialect group of its own: Hessian, whereas only South Hessian is part of Rhine Franconian. Hessian proper can be split into Lower Hessian in the north, East Hessian in the East around Fulda and Central Hessian, which covers the largest area of all dialects in Hesse. In the extreme Northeast, the Thuringian dialect zone extends into Hesse, whereas in the Southeast, the state border to Bavaria is not fully identical to the dialect border between East Franconian and East Hessian.

Since approximately World War II, a spoken variety of Standard German with dialect substrate has been superseding the tradition dialects mentioned so far. This development knows a north-to-south movement, the north being early to supplant the traditional language, whereas in the south, there is still a considerable part of the population that communicates in South Hessian. In most of the areas, however, the traditional language is close to extinction, whereas until the first half of the 20th century, almost the entire population spoke dialect in almost all situations. The Upper Class started to speak Standard German already in the late 19th century, so for decades, the traditional language served as a sociolect.

The prominent written language in Hesse has been Standard German since the 16th century. Before, the Low Saxon part used Middle Low German, the rest of the Land Early Modern German as prominent written languages. These had supplanted Latin in the High Middle Ages.

Religion

In 2016 Christianity was the most widespread religion in the state (63%).[32] 40% of Hessians belonged to the Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau or Evangelical Church of Hesse Electorate-Waldeck (members of the Evangelical Church in Germany), 25% adhered to the Roman Catholic Church, while other Christians constituted some 3%, the third most common religion of the Hessian population is Islam with 7% of the population.[33]

Education and Research

Higher education

The Hessian government has overall responsibility for the education within the state. Hesse has follow universities:

- Goethe University Frankfurt (43,972 students; Budget: € 666,4 Mio.)

- Technical University of Darmstadt (25,355 students; Budget: € 482,8 Mio.)

- Justus Liebig University Giessen (28,480 students; Budget: € 425,4 Mio.)

- Philipps University of Marburg (24,394 students; Budget: € 374,3 Mio.)

- University of Kassel (25,103 students; Budget: € 291,5 Mio.) [34]

No any Hesse's university belongs to German Excellence Universities.

Goethe University Frankfurt, Campus Westend

Goethe University Frankfurt, Campus Westend Technical University of Darmstadt, Main Entrance

Technical University of Darmstadt, Main Entrance Justus Liebig University Giessen

Justus Liebig University Giessen Philipps University of Marburg, Biomedical Research Center

Philipps University of Marburg, Biomedical Research Center University of Kassel, Entrance Holländischer Platz

University of Kassel, Entrance Holländischer Platz

There are many international schools in Hesse, primarily centred in and around Frankfurt.[35]

Hesse is the only state in Germany where students have to study all three stanzas of the Das Deutschlandlied.[36]

Big Science

A single existing big science facility in Hesse is GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research in Darmstadt-Wixhausen with 1,520 employees. The second one Facility for Antiproton and Ion Research is in construction till 2025.

In space research there are 2 European organization European Space Operations Center and European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites in Darmstadt.

Health & Medicine

- Max Planck Institue for Heart and Lung Research, Bad Nauheim

- Max Planck Institute for Brain Research, Frankfurt-am-Main

- Max Planck Institute of Biophysics, Frankfurt-am-Main

- Max Planck Research Center for Neurogenetics, Frankfurt-am-Main

- Fraunhofer Institute for Translational Medicine and Pharmacology, Frankfurt-am-Main

- Paul Ehrlich Institute (vaccines), Langen

- Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology, Marburg

- Institute of Virology (Marburg)(researh of Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus; Parasitology) with BSL4-Labor, Marburg

- Center for undiagnosed and rare diseases, Marburg

- Marburg Heavy Ion Beam Therapy Center, Marburg

- Sigmund Freud Institute (psychoanalysis), Frankfurt-am-Main

Informatics & Software

- Hessian Centre for Artificial Intelligence, HQ in Darmstadt, more locations in Hesse

- German Research Centre for Artificial Intelligence, Darmstadt

- Center for Advanced Security Research Darmstadt, Darmstadt

- Fraunhofer Institute for Secure Information Technology, Darmstadt

- Fraunhofer Institute for Graphic Data Processing, Darmstadt

Others

- Fraunhofer Institute for Structural Durability and System Reliability, Darmstadt

- Fraunhofer Institute for Energy Economics and Energy System Technology, HQ in Kassel, other location in Rothwesten and Bad Hersfeld

- Fraunhofer Facility for Material Cycles and Resource Strategy, Hanau

- Max-Planck-Institut für europäische Rechtsgeschichte, Frankfurt-am-Main

- Institut für Sozialforschung at Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt-am-Main

- Leibniz-Institut für Bildungsforschung und Bildungsinformation, Frankfurt-am-Main

- Forschungsinstitut für Deutsche Sprache – Deutscher Sprachatlas – at Philipps-Universität Marburg

- Paul-Ehrlich-Institut, * Forschungsinstitut und Naturmuseum Senckenberg, Frankfurt am Main

- Peace Research Institute Frankfurt, Frankfurt-am-Main

- Institut für sozial-ökologische Forschung, Frankfurt-am-Main

- Athene (research center), Darmstadt

Culture

Hesse has a rich and varied cultural history, with many important cultural and historical centres and several UNESCO world-heritage sites.

Architecture, art, literature and music

Darmstadt has a rich cultural heritage as the former seat of the Landgraves and Grand Dukes of Hesse. It is known as centre of the art nouveau Jugendstil and modern architecture and there are also several important examples of 19th century architecture influenced by British and Russian imperial architecture due to close family ties of the Grand Duke's family to the reigning dynasties in London and Saint Petersburg in the Grand Duchy period. Darmstadt is an important centre for music, home of the Darmstädter Ferienkurse for contemporary music[37] and the Jazz Institute Darmstadt, Europe's largest public jazz archive.[38]

Frankfurt am Main is a major international cultural centre. Over 2 million people visit the city's approximately 60 exhibition centres every year.[39] Amongst its most famous art galleries are the Schirn Kunsthalle, a major centre for international modern art,[40] and the Städel, whose large collections include over 3000 paintings, 4000 photographs, and 100,000 drawings including works by Picasso, Monet, Rembrandt and Dürer.[41] Goethe was born in Frankfurt and there is a museum in his birthplace. Frankfurt has many music venues, including an award-winning opera house, the Alte Oper, and the Jahrhunderthalle. Its several theatres include the English Theatre, the largest English-speaking theatre on the European continent.[42]

Kassel has many palaces and parks, including Bergpark Wilhelmshöhe, a Baroque landscape park and UNESCO World Heritage site.[43] The Brothers Grimm lived and worked in Kassel for 30 years and the recently opened Grimmwelt museum explores their lives, works and influence and features their personal copies of the Children's and Household Tales, which are on the UNESCO World Heritage "Memory of the World" Document register.[44] The Fridericianum, built in 1779, is one of the oldest public museums in Europe.[45] Kassel is also home to the documenta, a large modern art exhibition that has taken place every five years since the 1950s.[46]

The Hessian Ministry of the Arts supports numerous independent cultural initiatives, organisations, and associations as well as artists from many fields including music, literature, theatre and dance, cinema and the new media, graphic art, and exhibitions. International cultural projects aim to further relations with European partners.[47]

UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Hesse has several UNESCO World Heritage sites.[48] These include:

- Bergpark Wilhelmshöhe in Kassel[49]

- Kellerwald-Edersee National Park in North Hesse[50]

- Lorsch Abbey[51]

- The Messel Fossil Pit.[52] Exhibits from the Messel Pit can be seen in Messel town museum,[53] the Museum of Hessen in Darmstadt,[54] and the Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt.[55]

- The Saalburg, part of the Roman Limes.[56]

- Darmstadt Artists' Colony[57]

Sports

Frankfurt hosts the following professional sports teams or clubs:

- 1. FFC Frankfurt (1998–2020), football (women)

- Eintracht Frankfurt, football (men, women)

- FSV Frankfurt, football (men)

- Rot-Weiss Frankfurt, football

- Frankfurter FC Germania 1894, football

- Skyliners Frankfurt, basketball

- Frankfurt Galaxy (1991–2007), American football

- Frankfurt Universe (2007–present), American football

- Frankfurter Löwen (1979–1984), American football

- Frankfurt Sarsfields GAA, Gaelic football

- Frankfurt Lions (until 2010), ice hockey

- Löwen Frankfurt (since 2010), ice hockey

- SC 1880 Frankfurt, rugby union

Frankfurt is host to the classic cycle race Eschborn-Frankfurt City Loop (known as Rund um den Henninger-Turm from 1961 to 2008). The city hosts also the annual Frankfurt Marathon and the Ironman Germany.

Outside Frankfurt, notable professional sports teams include Kickers Offenbach, SV Darmstadt 98, Marburg Mercenaries, Gießen 46ers, MT Melsungen, VfB Friedberg, and the Kassel Huskies.

TV and radio stations

The Hessian state broadcasting corporation is called HR (Hessischer Rundfunk). HR is a member of the federal ARD broadcasting association. HR provides a statewide TV channel as well as a range of regional radio stations (HR 1, HR 2, HR 3, HR 4, you fm and HR info). Besides the state run HR, privately run TV stations exist and are an important line of commerce. Among the commercial radio stations that are active in Hesse, Hit Radio FFH, Planet Radio, Harmony FM, Radio BOB and Antenne Frankfurt are the most popular.

Economy

Financial

With Hesse's largest city Frankfurt am Main being home of the European Central Bank (ECB), the German Bundesbank and the Frankfurt Stock Exchange, Hesse is home to the financial capital of mainland Europe. Furthermore, Hesse has always been one of the largest and healthiest economies in Germany. Its GDP in 2013 exceeded €236 billion (about US$316 billion).[58] This makes Hesse itself one of the largest economies in Europe and the 38th largest in the world.[59] According to GDP-per-capita figures, Hesse is the wealthiest state (after the city-states Hamburg and Bremen) in Germany with approx. US$52,500.

Frankfurt is crucial as a financial center, with both the European Central Bank and the Deutsche Bundesbank's headquarters located there. Numerous smaller banks and Deutsche Bank, DZ Bank, KfW Bank, Commerzbank are also headquartered in Frankfurt, with the offices of several international banks also being housed there. Frankfurt is also the location of the most important German stock exchange, the Frankfurt Stock Exchange. Insurance companies have settled mostly in Wiesbaden. The city's largest private employer is the R+V Versicherung, with about 3,900 employees, other major employers are DBV-Winterthur, the SV SparkassenVersicherung and the Delta Lloyd Group.

Chemical & Pharma

The Rhine-Main Region has the second largest industrial density in Germany after the Ruhr area. The main economic fields of importance are the chemical and pharmaceutical industries with Sanofi, Merck, Heraeus, Stada, Messer Griesheim, Bayer Crop Science, SGL Carbon, Celanese, Cabot, Clariant, Akzo Nobel, Kuraray, Ineos, LyondellBasell, Allessa and Evonik Industries. But also other consumer goods are produced by Procter & Gamble, Coty and Colgate Palmolive. The Rhine-Main Region is not restricted only to Hesse, smaller part is in Rhineland-Palatinate. There situated 2 important pharma companies: BioNTech(HQ), which found the first mRNA vaccine against COVID-19 in the world (licensed to Pfizer), and Boehringer Ingelheim, close to Hesse's border in Mainz and Ingelheim respectively. It supports from Max Planck Institue for Heart and Lung Research, Max Planck Institute for Brain Research and Paul Ehrlich Institute.

Also in other part of Hesse there is important pharma and medical manufacturers, especially in Marburg where there is industry park based on ex-Behring Werke: BioNTech (mRNA vaccines), CSL Behring, Temmler and Melsungen with B. Braun. Pharma activity in Marburg is also supported from research facilities: Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology, Center for undiagnosed and rare diseases, Institute of Virology (Marburg)(researh of Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus; Parasitology) with BSL4-Labor, Marburg Heavy Ion Beam Therapy Center.

Merck controls ca. 60% of world's liquid crystal market.

Heraeus, Umicore and Evonik Industries manufacture different type of catalysts from Platinum metals, Vanadium, Neodymium, Manganese, Copper and etc.

In east Fulda there is the tire plant (Fulda Reifen). 2 other tire plants are in Korbach from Continental and Hanau from Goodyear.

Metallurgy & Nuclear

Very seldom special industry is metallurgy of platinum metals by Heraeus and Umicore and magnet materials by Vacuumschmelze in Hanau. Also in Hanau was located a plant to produce nuclear fuel (classical uranium, but also MOX fuel), now the production is stopped and it is in conservation. Heraeus manufactures an irradiation sources from Cobalt and Iridium, not activated.

Engineering

In the mechanical and automotive engineering field Opel in Rüsselsheim is worth mentioning. After acquisition Opel by Stellantis, it is in rapid decline of production and employment. Which has also negative effect on automotive parts supplier, Continental will close a plant in Karben and cut jobs at other location in Hesse. In northern Hesse, in Baunatal, Volkswagen AG has a large factory that manufactures spare parts, not far-away from it there is also a Daimler Truck plant, which produces an axes.

Alstom, after takeover of Bombardier, has a large plant that manufactures Traxx locomotives in Kassel. Industrial printers (Manroland, Gallus Holding), x-ray airport check equipment (Smiths), handling and loading equipment (Dematic), chemical equipment (Air Liquide Global E&C Solutions), vacuum pumps (Pfeiffer Vacuum), vacuum industrial furnace (ALD Vacuum Technologies), textile machines (Karl Mayer), shavers (Braun), medical (Fresenius, Sirona) and industrial (Schenck Process, Samson) apparatuses are produced in Rhine-Main Region.

Manufacturing of heating boilers and heat pumps are typical for Hesse and represented with Bosch Thermotechnik and Viessmann.

Vistec produces electron-beam lithography systems for semiconductor industry in Weilburg, also there is manufacturing of inspection, testing and measurement equipment for semiconductor fabrication process from KLA-Tencor. Leica Microsystems manufactures different types of microscopes, inclusive they with special light microscopic optics, which are used in wafer and photo mask testing. PVA TePla from Wettenberg is specialist for crystal growing process (Si, Ge, GaAs, GaP, InP) with Czochralski Process, Float-Zone Process, High-Temperature Chemical Vapor Deposition, Vertical Gradient Freeze equipment, quality inspection apparatus, plasma and vacuum machine. ABB Robotics is in Friedberg. Satisloh is a machine manufacturer in Wetzlar for the production of lenses and components for the optical industry.

Aerospace

The company operating Frankfurt Airport is one of the largest employers in Hesse with nearly 22,000 employees.[60] Aerospace cluster contains also Rolls-Royce's aviation engine work in Oberursel and APU manufacturing plant and service center of Honeywell in Raunheim.

Optics & Electronics

Companies with an international reputation are located outside the Rhine-Main region in Wetzlar. There is the center of the optical, electrical and precision engineering industries, Leitz, Leica, Minox, Hensoldt (Zeiss) and Brita with several plants in central Hesse.

Oculus Optikgeräte manufactures Scheimpflug tomographs for examining the anterior segment of the eye, topographers for measuring the anterior surface of the cornea, tonometers for assessing the biomechanical properties of the cornea, a wide-angle observation system for vitreous body surgery, universal trial goggles for subjective refraction, various perimeters for visual field testing and vision testing devices for testing eyesight.

Electrical transformers are produced by Hitachi ABB Power Grids in Hanau and Siemens Energy in Frankfurt-am-Main. SMA Solar Technology manufactures an inverters for photovoltaic systems. Rittal is specialized on electrical enclosure situated in Herborn and Eschenburg. Power semiconductors from IXYS in Lampertheim and UV and infrared lamps from Heraeus.

IT & Telecom

Many IT and telecommunications companies are located in Hesse, many of them in Frankfurt and Darmstadt, like Software AG (Darmstadt), T-Systems (Frankfurt and Darmstadt), Deutsche Telekom (laboratories in Darmstadt), DB Systel (Frankfurt), Lufthansa Systems (Raunheim near Frankfurt) and DE-CIX (Frankfurt).

Food & Beverage

Sweet making is typical, there are 2 big factories: Ferrero, Stadtallendorf and Baronie (Sarotti), Hattersheim am Main. Frankfurter Sausage is famous, but there is also other sorts like Frankfurter Rindswurst, Ahle Wurst.

Beverage industry is well-developed and manufactures sparkling wine (Sekt), white wine (Riesling), mineral waters (Selters), beers (Radeberger) and cider.

Green Sauce Monument

Green Sauce Monument

In Frankfurt-Oberrad exists growing of wild herbs for green sauce and monument.

Defunct Industries

The leather industry was predominantly based in Offenbach, but is now extinct, existing only in museums. The same happened with Frankfurt's fur industry and Hanau's jewelry industry.

Typical Hesse's Products

Unemployment

The Hochtaunuskreis has the lowest unemployment rate at 3.8% while the independent city of Kassel has the highest rate nationally at 12.1%.[61] In October 2018 the unemployment rate stood at 4.4% and was lower than the national average.[62]

| Year[63] | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployment rate in % | 7.3 | 6.6 | 7.0 | 7.9 | 8.2 | 9.7 | 9.2 | 7.5 | 6.5 | 6.8 | 6.4 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 3.1 | 4.1 | 3.8 |

Traffic and public transportation

Road transport

Hesse has a dense highway network with a total of 24 motorways. The internationally important motorway routes through Hesse are the A3, A5, and A7. Close to Frankfurt Airport is the Frankfurter Kreuz, Germany's busiest and one of Europe's busiest motorway junctions, where the motorways A3 (Arnhem-Cologne-Frankfurt-Nuremberg-Passau) and A5 (Hattenbach-Frankfurt-Karlsruhe-Basel) intersect. The A5 becomes as wide as four lanes in each direction near the city of Frankfurt am Main, and during the rush-hour, it is possible to use the emergency lanes on the A3 and A5 motorway in the Rhine-Main Region, adding additional lanes. Other major leading Hesse highways are the A4, the A44, the A45, the Federal Highway A66 and the A67. There are also a number of smaller motorways and major trunk roads, some of which are dual carriageways.

Railway transport

Hesse is accessed by many major rail lines, including the high-speed lines Cologne–Frankfurt(op.speed 300 km/h) and Hanover–Würzburg. Other north-south connections traverse major east–west routes from Wiesbaden and Mainz to Frankfurt and from Hanau and Aschaffenburg to Fulda and Kassel. The Frankfurt Central Station is the most important hub for German trains, with over 1,100 trains per day.[64]

The region around Frankfurt has an extensive S-Bahn network, the S-Bahn Rhein-Main, which is complemented by many regional train connections. In the rest of the country, the rail network is less extensive. Since 2007, the region around Kassel has been served by the RegioTram, a tram-train-concept similar to the Karlsruhe model.

Air transport

Frankfurt Airport is by far the largest airport in Germany with more than 57 million passengers each year, is and among the world's ten largest. Frankfurt Egelsbach Airport lies to the south, and is frequented by general aviation and private planes. Kassel Airport offers a few flights to holiday destinations, but has struggled to compete. There are also a number of sports airfields. Low-cost airlines, especially Ryanair, use Frankfurt-Hahn Airport as a major base, although the airport is actually located about 100 km from Frankfurt in the neighbouring state of Rhineland-Palatinate. The DFS (German air traffic control) has its headquarters in Langen.

References

Notes

- "Bevölkerung der hessischen Gemeinden". Hessisches Statistisches Landesamt (in German). September 2018.

- Baden-Württemberg, Statistisches Landesamt. "Bruttoinlandsprodukt – in jeweiligen Preisen – in Deutschland 1991 bis 2019 nach Bundesländern (WZ 2008) – VGR dL". www.vgrdl.de. Archived from the original on 2020-06-25. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 2018-09-13.

- "Hesse". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22.

- "Hesse". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- "Geschichte. Kurz und knapp – Geschichte – Identität – Region – Rheinhessen". Rheinhessen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- Gudmund Schütte, Our forefathers : The Gothonic nations : A manual of the ethnography of the Gothic, German, Dutch, Anglo-Saxon, Frisian and Scandinavian peoples, vol. 2 (1933), p. 191.

- Christian Presche, Kassel im Mittelalter: Zur Stadtentwicklung bis 1367 vol. 1 (2013), p. 41.

- "The Hessians, called, in the early history of Germany, Catti, lived in the present Hessia". The Popular Encyclopedia: Or, Conversations Lexicon vol. 3 (1862), p. 720. Occasional English use of Hessia is found until the present day, e.g. P.J.J. Welfens, Stabilizing and Integrating the Balkans, Springer Science & Business Media (2001), p. 119.

- "Chart of usage frequency: Hessia, Hesse". Google Books Ngram Viewer.

- ilpert, Joseph Leonhard (1857). A Dictionary of the English and German and the German and English Language. B. Hermann.

- "European Commission English Style Guide" (PDF). paragraphs 1.31 and 1.35. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 5, 2010.

- "Names and symbols of transfermium elements (IUPAC Recommendations 1997)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 69.12 (1997), p. 2471. doi:10.1351/pac199769122471.

- Clay 125-27, 137–39.

- Clay 120.

- Clay 132–137.

- Clay 143–155.

- Rau 141.

- Clay 157–158.

- Charles W. Ingrao, The Hessian Mercenary State: Ideas, Institutions, and Reform under Frederick II, 1760–1785 (2003)

- "Hessen – 60 stolze Jahre – Zeittafel 1945/1946". Archived from the original on 2006-10-17. Retrieved 2006-12-01.

- "Our State". State of Hesse. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- State of Hesse. Foreign representation offices. Archived 2014-08-23 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved June 30, 2014

- ""Ich kenne ein Land" | Informationsportal Hessen". www.hessen.de (in German). Archived from the original on 2018-05-13. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- "Tabellen Bevölkerung". Statistik.Hessen. September 18, 2017.

- Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine 31 December 2014 German Statistical Office. Zensus 2014: Bevölkerung am 31. Dezember 2014 Archived 2016-11-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Baden-Württemberg, Statistisches Landesamt. "Gemeinsames Datenangebot der Statistischen Ämter des Bundes und der Länder". www.statistik-bw.de (in German). Archived from the original on 2007-06-12. Retrieved 2018-05-12.

- "Tabellen Bevölkerung". Statistik.Hessen (in German). 2017-09-18. Retrieved 2018-05-12.

- "Bevölkerung in Hessen 2060 – Regionalisierte Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung für Hessen bis 2030 Basisjahr: 31.12.2014". www.statistik-hessen.de. Archived from the original on 2016-05-06. Retrieved 2018-05-12.

- "Frankfurt Population 2018 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs)". worldpopulationreview.com. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- "Bevölkerung". Statistische Ämter des Bundes Und der Länder. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- "Eine Umfrage zu Religiosität, religionsbezogener Toleranz und der Rolle der Religion in Hessen 2017" (PDF). soziales.hessen.de (in German). Hessisches Ministerium für Soziales und Integration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- "Religionszugehörigkeit nach Bundesländern in Deutschland". Statista.

- "Study in Hessen". www.study-in-hessen.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- "Newcomers Network – Your Guide to Expatriate Life in Germany". www.newcomers-network.de. Archived from the original on 2018-05-13. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- Geisler 2005, p. 72. – https://books.google.com/books?id=CLVaSxt-sV0C&pg=PA72

- "Darmstädter Ferienkurse – Internationales Musikinstitut Darmstadt". Internationales Musikinstitut Darmstadt. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- "Jazzinstitut Darmstadt". www.jazzinstitut.de. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- "Frankfurt am Main: Museums". www.frankfurt.de. Archived from the original on 2017-08-18. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- FRANKFURT, SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE (2016-04-28). "About us". SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- "About the Städel Museum". Städel Museum. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- "Frankfurt am Main: English Theatre". www.frankfurt.de. Archived from the original on 2018-05-13. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- "UNESCO world heritage site of bergpark wilhelmshöhe | Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel". museum-kassel.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- "Welcome to the GRIMM WORLD Kassel: GRIMMWELT". www.grimmwelt.de. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- Kassel, Stadt. "Stadtportal – Fridericianum". www.kassel.de (in German). Archived from the original on 2018-05-13. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- "documenta". www.documenta.de. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- State of Hesse Website – Art and Culture Archived 2017-07-04 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved July 21, 2015

- "UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Hessen". Hessen Tourismus. Archived from the original on 2018-05-13.

- "Bergpark Wilhelmshöhe". Hessen Tourismus. Archived from the original on 2018-05-14. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- "Germany's Ancient Beech Forests | Hessen Tourismus". www.languages.hessen-tourismus.de. Archived from the original on 2018-05-13. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- "Lorsch – Benedictine Abbey and Altenmünster | Hessen Tourismus". www.languages.hessen-tourismus.de. Archived from the original on 2018-05-13. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- "Messel Pit Fossil Site | Hessen Tourismus". www.languages.hessen-tourismus.de. Archived from the original on 2018-05-14. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- "Home". www.grube-messel.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- "Messel Pit – Hessisches Landesmuseum". www.hlmd.de. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- "SENCKENBERG world of biodiversity | Museums | Museum Frankfurt | The Museum | Exhibitions | World natural heritage "." www.senckenberg.de. Archived from the original on 2017-09-24. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- "Roman Limes | Hessen Tourismus". www.languages.hessen-tourismus.de. Archived from the original on 2018-05-13. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- "Mathildenhöhe Darmstadt von UNESCO ausgezeichnet". Deutsche UNESCO-Kommission (in German). 24 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- "Bruttoinlandsprodukt". Volkswirtschaftliche Gesamtrechnungen (in German). Hessisches Statistisches Landesamt. 2012. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- See the list of countries by GDP (nominal).

- "Annual Report 2018" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-04-01.

- "EURES – Labour market information – Hessen – European Commission". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- "Arbeitslosenquote nach Bundesländern in Deutschland 2018 | Statista". Statista (in German). Retrieved 2018-11-13.

- (Destatis), © Statistisches Bundesamt (2018-11-13). "Federal Statistical Office Germany – GENESIS-Online". www-genesis.destatis.de. Retrieved 2018-11-13.

- "Bahn". Frankfurt am Main. Archived from the original on 5 September 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

Bibliography

- Ingrao, Charles W. The Hessian mercenary state: ideas, institutions, and reform under Frederick II, 1760–1785 (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

- Ingrao, Charles. "" Barbarous Strangers": Hessian State and Society during the American Revolution." American Historical Review 87.4 (1982): 954–976. online

- Wegert, Karl H. "Contention with Civility: The State and Social Control in the German Southwest, 1760–1850." Historical Journal 34.2 (1991): 349–369. online

- Wilder, Colin F. "" THE RIGOR OF THE LAW OF EXCHANGE": How People Changed Commercial Law and Commercial Law Changed People (Hesse-Cassel, 1654–1776)." Zeitschrift für Historische Forschung (2015): 629–659. online

- Clay, John-Henry (2010). In the Shadow of Death: Saint Boniface and the Conversion of Hessia, 721-54. Brepols. ISBN 978-2-503-53161-8.

- Rau, Reinhold (1968). Briefe des Bonifatius, Willibalds Leben des Bonifatius; Nebst Einigen Zeitgenössischen Dokumenten. Ausgewählte Quellen zur Deutschen Geschichte des Mittelalters (in German). Vol. IVb. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

External links

- Official government portal (English version) Archived 2015-08-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Wiki about Hesse in Hessian language

- "Hesse". Catholic Encyclopedia.

Geographic data related to Hesse at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Hesse at OpenStreetMap

.jpg.webp)