Fuzuli (writer)

Mahammad bin Suleyman (Classical Azerbaijani: محمد سليمان اوغلی Məhəmməd Süleyman oğlu), better known by his pen name Fuzuli (Azerbaijani: فضولی Füzuli;[lower-alpha 1] c. 1494 – 1556), was a 16th century poet, writer and thinker, who wrote in his native Azerbaijani, as well as Arabic and Persian languages.[1] Considered one of the greatest contributors to the divan tradition of Azerbaijani literature, Fuzuli in fact wrote his collected poems (divan) in all three languages. He is also regarded as one of the greatest Ottoman lyrical poets[2] with knowledge of both the Ottoman and Chagatai Turkic literary traditions, as well as mathematics and astronomy.[3]

Fuzuli | |

|---|---|

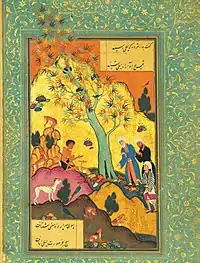

Miniature of Fuzuli in 16th century Meşâirü'ş-şuarâ | |

| Born | Mahammad Suleyman oghlu c. 1494 Karbala, Aq Qoyunlu confederation (now Iraq) |

| Died | 1556 Karbala, Ottoman Empire (now Iraq) |

| Genre | Azerbaijani, Arabic and Persian epic poetry, wisdom literature |

| Notable works | The Epic of Layla and Majnun (Leyli və Məcnun) |

Life

Fuzûlî is generally believed to have been born around 1480 in what is now Iraq, when the area was under Ak Koyunlu Turkmen rule; he was probably born in either Karbalā’ or an-Najaf.[3] He was an Azerbaijani[4][5][6][7] descended from the Turkic Oghuz Bayat tribe, who were scattered throughout the Middle East, Anatolia, and the Caucasus at the time.[8][9][10][11] Though Fuzûlî's ancestors had been of nomadic origin, the family had long since settled in towns.

Fuzûlî appears to have received a good education, first under his father—who was a mufti in the city of Al Hillah—and then under a teacher named Rahmetullah.[12] It was during this time that he learned the Persian and Arabic languages in addition to his native Azerbaijani. Fuzûlî showed poetic promise early in life, composing sometime around his twentieth year the important masnavi entitled Beng ü Bâde (بنگ و باده; "Hashish and Wine"), in which he compared the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II to hashish and the Safavid shah Ismail I to wine, much to the advantage of the latter.

One of the few things that is known of Fuzûlî's life during this time is how he arrived at his pen name. In the introduction to his collected Persian poems, he says: "In the early days when I was just beginning to write poetry, every few days I would set my heart on a particular pen name and then after a time change it for another because someone showed up who shared the same name".[13] Eventually, he decided upon the Arabic word fuzûlî—which literally means "impertinent, improper, unnecessary"—because he "knew that this title would not be acceptable to anyone else".[14] Despite the name's pejorative meaning, however, it contains a double meaning—what is called tevriyye (توريه) in Ottoman Divan poetry—as Fuzûlî himself explains: "I was possessed of all the arts and sciences and found a pen name that also implies this sense since in the dictionary fuzûl (ﻓﻀﻮل) is given as a plural of fazl (ﻓﻀﻞ; 'learning') and has the same rhythm as ‘ulûm (ﻋﻠﻮم; 'sciences') and fünûn (ﻓﻨﻮن; 'arts')".[14]

In 1534, the Ottoman sultan Süleymân I conquered the region of Baghdad, where Fuzûlî lived, from the Safavid Empire. Fuzûlî now had the chance to become a court poet under the Ottoman patronage system, and he composed a number of kasîdes, or panegyric poems, in praise of the sultan and members of his retinue, and as a result, he was granted a stipend. However, owing to the complexities of the Ottoman bureaucracy, this stipend never materialized. In one of his best-known works, the letter Şikâyetnâme (شکايت نامه; "Complaint"), Fuzûlî spoke out against such bureaucracy and its attendant corruption:

- سلام وردم رشوت دگلدر ديو آلمادىلر

- Selâm verdim rüşvet değildir deyü almadılar.[15]

- I gave my greetings but they didn't receive it as it wasn't a bribe.

Though his poetry flourished during his time among the Ottomans, the loss of his stipend meant that, materially speaking, Fuzûlî never became secure. In fact, most of his life was spent attending upon the Tomb of `Alî in the city of an-Najaf, south of Baghdad.[16] He died during a plague outbreak in 1556, in Karbalā’, either of the plague itself or of cholera.

Works

یا رب بلای عشق ايله قيل آشنا منى

بیر دم بلای عشقدن ایتمه جدا منى

آز ايلمه عنایتونى اهل دردن

يعنى كی چوخ بلالره قيل مبتلا منى

Yâ Rabb belâ-yı ‘aşk ile kıl âşinâ meni

Bir dem belâ-yı ‘aşkdan etme cüdâ meni

Az eyleme ‘inâyetüni ehl-i derdden

Ya‘ni ki çoh belâlara kıl mübtelâ meni[17]

Oh God, make me acquainted with the affliction of love!

For one moment make me not separated from the affliction of love!

Do not lessen your solicitude from the people of pain,

But rather, make afflicted me one more of them!

—Excerpt from Dâstân-ı Leylî vü Mecnun.

_of_Fuzuli_-_Muhammad_bin_Sulayman_known_as_Fuzuli.jpg.webp)

Fuzûlî has always been known, first and foremost, as a poet of love. It was, in fact, a characterization that he seems to have agreed with:

- مندن فضولی ايستمه اشعار مدح و ذم

- من عاشقام هميشه سوزوم عاشقانه دیر

- Menden Fuzûlî isteme eş'âr-ı medh ü zem

- Men âşıkam hemîşe sözüm âşıkânedür[18]

- Don't ask Fuzûlî for poems of praise or rebuke

- I am a lover and speak only of love

Fuzûlî's notion of love, however, has more in common with the Sufi idea of love as a projection of the essence of God—though Fuzûlî himself seems to have belonged to no particular Sufi order—than it does with the Western idea of romantic love. This can be seen in the following lines from another poem:

- عاشق ايمش هر ن وار ﻋﺎﻝﻢ

- ﻋلم بر قيل و قال ايمش آنجق

- ‘Âşık imiş her ne var ‘âlem

- ‘İlm bir kîl ü kâl imiş ancak[19]

- All that is in the world is love

- And knowledge is nothing but gossip

The first of these lines, especially, relates to the idea of wahdat al-wujūd (وحدة الوجود), or "unity of being", which was first formulated by Ibn al-‘Arabī and which states that nothing apart from various manifestations of God exists. Here, Fuzûlî uses the word "love" (عشق ‘aşk) rather than God in the formula, but the effect is the same.

Fuzûlî's most extended treatment of this idea of love is in the long poem Dâstân-ı Leylî vü Mecnun (داستان ليلى و مجنون), a mesnevî which takes as its subject the classical Arabian love story of Layla and Majnun. In his version of the story, Fuzûlî concentrates upon the pain of the mad lover Majnun's separation from his beloved Layla, and comes to see this pain as being of the essence of love.

The ultimate value of the suffering of love, in Fuzûlî's work, lies in that it helps one to approach closer to "the Real" (al-Haqq الحق), which is one of the 99 names of God in Islamic tradition.

Selected bibliography

Works in Azerbaijani Turkic

- Dîvân ("Collected Poems")

- Beng ü Bâde (بنگ و باده; "Hashish and Wine")

- Hadîkat üs-Süedâ (حديقت السعداء; "Garden of Pleasures")

- Dâstân-ı Leylî vü Mecnûn (داستان ليلى و مجنون; "The Epic of Layla and Majnun")

- Risâle-i Muammeyât (رسال ﻤﻌﻤيات; "Treatise on Riddles")

- Şikâyetnâme (شکايت نامه; "Complaint")

Works in Persian

- Dîvân ("Collected Poems")

- Anîs ol-qalb (انیس القلب; "Friend of the Heart")

- Haft Jâm (هفت جام; "Seven Goblets")

- Rend va Zâhed (رند و زاهد; "Hedonist and Ascetic")

- Resâle-e Muammeyât (رسال ﻤﻌﻤيات; "Treatise on Riddles")

- Sehhat o Ma'ruz (صحت و معروض; "Health and Sickness")

Works in Arabic

- Dīwān ("Collected Poems")

- Maṭla‘ ul-I‘tiqādi (مطلع الاﻋﺘﻘﺎد; "The Birth of Faith")

Translations into English

- Fuzuli. Leyla and Mejnun. Translated by Sofi Huri. Introduction and notes by Alessio Bombaci. London: George Allen & Unwin, Ltd., 1970.

Legacy

According to the Encyclopædia Iranica:

Fuzuli is credited with some fifteen works in Arabic, Persian, and Turkic, both in verse and prose. Although his greatest significance is undoubtedly as a Turkic poet, he is also of importance to Persian literature thanks to his original works in that language (indeed, Persian was the language he preferred for his Shi'ite religious poetry); his Turkic adaptations or translations of Persian works; and the inspiration he derived from Persian models for his Turkic works.

...

The fundamental gesture of Fuzûlî's poetry is inclusiveness. It links Azeri, Turkmen and Ottoman (Rumi) poetry, east and west; it also bridges the religious divide between Shiism and Sunnism. Generations of Ottoman poets admired and wrote responses to his poetry; no contemporary canon can bypass him.

In April 1959, in honour of his 400th death anniversary, Karyagin district and the Fuzuli (city) were renamed to Fuzuli.[20] A street and a square are named after him in the center of Baku, as well as streets in many other cities of Azerbaijan. Several Azerbaijani institutions are named after him, including the Institute of Manuscripts in Baku.

In 1996 the National Bank of Azerbaijan minted a golden 100 manat and a silver 50 manat commemorative coins dedicated to the 500th anniversary of Fuzûlî's life and activities.[21]

Notes

- His name has also been translated as:

- Arabic: محمد بن سليمان الفضولي Muḥammad bin Sulaymān al-Fuḍūlī;

- Ottoman Turkish: محمد بن سلیمان فضولی Mehmed bin Süleymân Fuzûlî;

- Persian: محمد بن سلیمان فضولی Moḥammad ben Soleymân Fożuli.

References

- Gutsche, George J.; Weber, Harry Butler; Rollberg, Peter (1987). The Modern Encyclopedia of Russian and Soviet Literatures: Including Non-Russian and Emigre Literatures. Forest spirit-Gorenshtein, Fridrikh Naumovich. Academic International Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-87569-038-4.

In Mesopotamia Fuzuli was in intimate contact with three cultures — Turkic, Arabic, and Persian. Besides his native Azeri, he learned Arabic and Persian at an early age and acquired a through command of the literatures in all three languages, an accomplishment in which the cosmopolitan literary and scholarly circles of Hilla played an important role.

- Somel, Selcuk Aksin (13 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of the Ottoman Empire. Scarecrow Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-8108-6606-5.

Fuzuli is regarded as one of the greatest Ottoman lyric poets.

- "FOŻŪLĪ, MOḤAMMAD". Encyclopaedia Iranica. 2000. pp. 121–122.

- Savory, Roger (1976). Introduction to Islamic Civilization | Middle East history. Cambridge University Press. p. 82.

Fuzuli (d. 1556) was not in fact a typical Ottoman. He was born into an Azerbaijani family in Iraq, where he seems to have spent his entire life.

- Doerfer, Gerhard (1988). "AZERBAIJAN viii. Azeri Turkish". Encyclopaedia Iranica. pp. 245–248.

Other important Azeri authors were Shah Esmāʿīl Ṣafawī “Ḵatāʾī” (1487-1524), and Fożūlī (about 1494-1556), an outstanding Azeri poet.

- Green, Nile (2019). The Persianate World: The Frontiers of a Eurasian Lingua Franca (1 ed.). University of California Press. p. 30.

As with multilingual poets such as the Azerbaijani Muhammad bin Sulayman, called Fuzuli (1494–1556)...

- Sultan-Qurraie, Hadi (2003). Modern Azeri Literature: Identity, Gender and Politics in the Poetry of Moj́uz. Indiana University Turkish Studies. p. 3.

Fuzuli of Baghdad, also called Suleyman Oghlu, was one of the most gifted Azeri poets of this period.

- Abbas, Hassan (2021). The Prophet's Heir: The Life of Ali Ibn Abi Talib. Yale University Press. p. 10.

Fuzuli, an Azerbaijani hailing from a Turkic Oghuz tribe Bayat, was a poet and an intellectual.

- "MUHAMMED FUZULI (1498-1556)". turkishculture.org. Turkish Cultural Foundation.

He belonged to the Turkic tribe of Bayat, one of the Turcoman tribes that was scattered in all over the Middle East, Anatolia and the Caucasus from the 10th to 11th century and which has roots connected to the Azerbaijanian people.

- "Mehmed bin Süleyman Fuzuli". brittanica.org. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Kathleen R. F. Burrill (1 January 1972). The Quatrains of Nesimi, Fourteenth-century Turkic Hurufi. De Gruyter Mouton. ISBN 978-90-279-2328-8.

- Şentürk 281

- Quoted in Andrews, 236.

- Ibid.

- Kudret 189

- Andrews 237

- Leylâ ve Mecnun 216

- Tarlan 47

- Kudret 20

- Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Azerbaijan SSR, (1961), Azerbaijan SSR, Administrative-territorial division on January 1, 1961, p. 9

- Central Bank of Azerbaijan. Commemorative coins. Coins produced within 1992-2010 Archived January 19, 2010, at the Wayback Machine: Gold and silver coins dedicated to memory of Mahammad Fuzuli. – Retrieved on 25 February 2010.

Sources

Primary

- Fuzulî. Fuzulî Divanı: Gazel, Musammat, Mukatta' ve Ruba'î kısmı. Ed. Ali Nihad Tarlan. İstanbul: Üçler Basımevi, 1950.

- Fuzulî. Leylâ ve Mecnun. Ed. Muhammet Nur Doğan. ISBN 978-975-08-0198-3.

Secondary

- Andrews, Walter G. "Fuzûlî" in Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology. pp. 235–237. ISBN 978-0-292-70472-5.

- "Fozuli, Mohammad b. Solayman". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 25 August 2006.

- "Fuzuli, Mehmed bin Süleyman." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service. 23 Aug. 2006 <>.

- Kudret, Cevdet. Fuzuli. ISBN 978-975-10-2016-1.

- Şentürk, Ahmet Atillâ. "Fuzûlî" in Osmanlı Şiiri Antolojisi. pp. 280–324. ISBN 978-975-08-0163-1.

- The investigation of the mystical similarities and differences of Fozoli's Persian and Turkish Divans against Hafez's Divan (Thesis for M.A degree Islamic Azad University of Tabriz, Iran ) By: Gholamreza Ziyaee Prof.: Ph.D: Aiyoub Koushan

- A comparative adaptation of Peer in Khajeh Hafez's divan with Hakim Fozooli's Persian and Turkish divans,Article 7, Volume 6, Number 21, Autumn 2012, Page 159-188

Document Type: Research Paper Authors: 1Aiyoub Koushan; 2Gholamreza Zyaee 1Faculty member, Department of Persian Literature, Tabriz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tabriz, Iran 2Student, Department of Persian Literature, Tabriz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tabriz, Iran.

External links

- Fuzûlî, on archive.org

- Muhammed Fuzuli—a website with a brief biography and translated selections from Leyla and Mecnun

- FUZULİ

- Fuzûlî in Stanford J. Shaw's History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey