Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland (Irish: Tuaisceart Éireann [ˈt̪ˠuəʃcəɾˠt̪ˠ ˈeːɾʲən̪ˠ] (![]() listen);[6] Ulster-Scots: Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region.[2][7][8][9][10] Northern Ireland shares a border to the south and west with the Republic of Ireland. In 2021, its population was 1,903,100,[11] making up about 27% of Ireland's population and about 3% of the UK's population. The Northern Ireland Assembly (colloquially referred to as Stormont after its location), established by the Northern Ireland Act 1998, holds responsibility for a range of devolved policy matters, while other areas are reserved for the UK Government. Northern Ireland cooperates with the Republic of Ireland in several areas.[12]

listen);[6] Ulster-Scots: Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region.[2][7][8][9][10] Northern Ireland shares a border to the south and west with the Republic of Ireland. In 2021, its population was 1,903,100,[11] making up about 27% of Ireland's population and about 3% of the UK's population. The Northern Ireland Assembly (colloquially referred to as Stormont after its location), established by the Northern Ireland Act 1998, holds responsibility for a range of devolved policy matters, while other areas are reserved for the UK Government. Northern Ireland cooperates with the Republic of Ireland in several areas.[12]

Northern Ireland

| |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Various | |

Location of Northern Ireland (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| Status | Country (constituent unit) |

| Capital and largest city | Belfast 54°36′N 5°55′W |

| Recognised languages[b] | |

| Ethnic groups (2021) |

|

| Religion (2021) |

|

|

|

| Government | Consociational devolved legislature within unitary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Charles III |

| Vacant | |

| Vacant | |

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | |

| • Secretary of State | Chris Heaton-Harris |

| • House of Commons | 18 MPs (of 650) |

| Legislature | Northern Ireland Assembly |

| Devolution | |

| 3 May 1921 | |

• Constitution Act | 18 July 1973 |

• Northern Ireland Act | 17 July 1974 |

• Northern Ireland Act | 19 November 1998 |

| Area | |

• Total | 14,130 km2 (5,460 sq mi)[2] |

| Population | |

• 2021 census | 1,903,100 |

• Density | 135/km2 (349.6/sq mi) |

| GVA | 2020 estimate |

| • Total | £43.664 billion[3] |

| • Per capita | £23,035 |

| HDI (2019) | 0.899[4] very high |

| Currency | Pound sterling (GBP; £) |

| Time zone | UTC (Greenwich Mean Time) |

| UTC+1 (British Summer Time) | |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (AD) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +44[c] |

| ISO 3166 code | GB-NIR |

| |

Northern Ireland was created in 1921, when Ireland was partitioned by the Government of Ireland Act 1920, creating a devolved government for the six northeastern counties. As was intended, Northern Ireland had a unionist majority, who wanted to remain in the United Kingdom;[13] they were generally the Protestant descendants of colonists from Britain. Meanwhile, the majority in Southern Ireland (which became the Irish Free State in 1922), and a significant minority in Northern Ireland, were Irish nationalists and Catholics who wanted a united independent Ireland.[14] Today, the former generally see themselves as British and the latter generally see themselves as Irish, while a Northern Irish or Ulster identity is claimed by a significant minority from all backgrounds.[15]

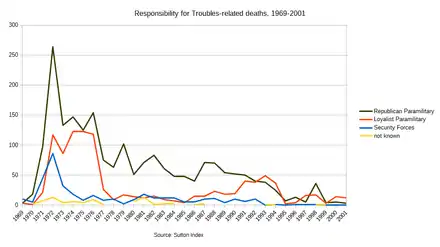

The creation of Northern Ireland was accompanied by violence both in defence of and against partition. During the conflict of 1920–22, the capital Belfast saw major communal violence, mainly between Protestant unionist and Catholic nationalist civilians.[16] More than 500 were killed[17] and more than 10,000 became refugees, mostly Catholics.[18] For the next fifty years, Northern Ireland had an unbroken series of Unionist Party governments.[19] There was informal mutual segregation by both communities,[20] and the Unionist governments were accused of discrimination against the Irish nationalist and Catholic minority.[21] In the late 1960s, a campaign to end discrimination against Catholics and nationalists was opposed by loyalists, who saw it as a republican front.[22] This unrest sparked the Troubles, a thirty-year conflict involving republican and loyalist paramilitaries and state forces, which claimed over 3,500 lives and injured 50,000 others.[23][24] The 1998 Good Friday Agreement was a major step in the peace process, including paramilitary disarmament and security normalisation, although sectarianism and segregation remain major social problems, and sporadic violence has continued.[25]

The economy of Northern Ireland was the most industrialised in Ireland at the time of Partition of Ireland, but declined, a decline exacerbated by the political and social turmoil of the Troubles.[26] Its economy has grown significantly since the late 1990s. The initial growth came from the "peace dividend" and increased trade with the Republic of Ireland, continuing with a significant increase in tourism, investment, and business from around the world. Unemployment in Northern Ireland peaked at 17.2% in 1986, dropping to 6.1% for June–August 2014 and down by 1.2 percentage points over the year,[27] similar to the UK figure of 6.2%.[28]

Cultural links between Northern Ireland, the rest of Ireland, and the rest of the UK are complex, with Northern Ireland sharing both the culture of Ireland and the culture of the United Kingdom. In many sports, the island of Ireland fields a single team, with the Northern Ireland national football team being an exception to this. Northern Ireland competes separately at the Commonwealth Games, and people from Northern Ireland may compete for either Great Britain or Ireland at the Olympic Games.

History

The region that is now Northern Ireland was long inhabited by native Gaels who were Irish-speaking and predominantly Catholic.[29] It was made up of several Gaelic kingdoms and territories and was part of the province of Ulster. In 1169, Ireland was invaded by a coalition of forces under the command of the English crown that quickly overran and occupied most of the island, beginning 800 years of foreign central authority. Attempts at resistance were swiftly crushed everywhere outside of Ulster. Unlike in the rest of the country, where Gaelic authority continued only in scattered, remote pockets, the major kingdoms of Ulster would mostly remain intact with English authority in the province contained to areas on the eastern coast closest to Great Britain. English power gradually eroded in the face of stubborn Irish resistance in the centuries that followed; eventually being reduced to only the city of Dublin and its suburbs. When Henry VIII launched the 16th century Tudor re-conquest of Ireland, Ulster once resisted most effectively. In the Nine Years' War (1594–1603), an alliance of Gaelic chieftains led by the two most powerful Ulster lords, Hugh Roe O'Donnell and the Earl of Tyrone fought against the English government in Ireland. The Ulster-dominated alliance represented the first Irish united front (prior resistance had always been localized). Despite being able to cement an alliance with Spain and major victories early on, inevitable defeat was virtually guaranteed following England's victory at the Siege of Kinsale. In 1607, the rebellion's leaders fled to mainland Europe alongside much of Ulster's Gaelic nobility. Their lands were confiscated by the Crown and colonized with English-speaking Protestant settlers from Britain, in the Plantation of Ulster. This led to the founding of many of Ulster's towns and created a lasting Ulster Protestant community with ties to Britain. The Irish Rebellion of 1641 began in Ulster. The rebels wanted an end to anti-Catholic discrimination, greater Irish self-governance, and to roll back the Plantation. It developed into an ethnic conflict between Irish Catholics and British Protestant settlers and became part of the wider Wars of the Three Kingdoms (1639–53), which ended with the English Parliamentarian conquest. Further Protestant victories in the Williamite-Jacobite War (1688–91) solidified Anglican Protestant rule in the Kingdom of Ireland. The Williamite victories of the Siege of Derry (1689) and Battle of the Boyne (1690) are still celebrated by some Protestants in Northern Ireland.[30] Many more Scots Protestants migrated to Ulster during the Scottish famine of the 1690s.

Following the Williamite victory, and contrary to the Treaty of Limerick (1691), a series of Penal Laws were passed by the Anglican Protestant ruling class in Ireland. The intention was to disadvantage Catholics and, to a lesser extent, Presbyterians. Some 250,000 Ulster Presbyterians emigrated to the British North American colonies between 1717 and 1775.[31] It is estimated that there are more than 27 million Scotch-Irish Americans now living in the United States,[32] along with many Scotch-Irish Canadians in Canada. In the context of institutional discrimination, the 18th century saw secret, militant societies develop in Ulster and act on sectarian tensions in violent attacks. This escalated at the end of the century, especially during the County Armagh disturbances, where the Protestant Peep o'Day Boys fought the Catholic Defenders. This led to the founding of the Protestant Orange Order. The Irish Rebellion of 1798 was led by the United Irishmen; a cross-community Irish republican group founded by Belfast Presbyterians, which sought Irish independence. Following this, the government of the Kingdom of Great Britain pushed for the two kingdoms to be merged, in an attempt to quell sectarianism, remove discriminatory laws, and prevent the spread of French-style republicanism. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was formed in 1801 and governed from London. During the 19th century, legal reforms known as the Catholic emancipation continued to remove discrimination against Catholics, and progressive programs enabled tenant farmers to buy land from landlords.

Home Rule Crisis

By the late 19th century, a large and disciplined cohort of Irish Nationalist MPs at Westminster committed the Liberal Party to "Irish Home Rule"—self-government for Ireland, within the United Kingdom. This was bitterly opposed by Irish Unionists, most of whom were Protestants, who feared an Irish devolved government dominated by Irish nationalists and Catholics. The Government of Ireland Bill 1886 and Government of Ireland Bill 1893 were defeated. However, Home Rule became a near-certainty in 1912 after the Government of Ireland Act 1914 was introduced. The Liberal government was dependent on Nationalist support, and the Parliament Act 1911 prevented the House of Lords from blocking the bill indefinitely.[33]

In response, unionists vowed to prevent Irish Home Rule, from Conservative and Unionist Party leaders such as Bonar Law and Dublin-based barrister Edward Carson to militant working class unionists in Ireland. This sparked the Home Rule Crisis. In September 1912, more than 500,000 Unionists signed the Ulster Covenant, pledging to oppose Home Rule by any means and to defy any Irish government.[34] In 1914, unionists smuggled thousands of rifles and rounds of ammunition from Imperial Germany for use by the Ulster Volunteers (UVF), a paramilitary organisation formed to oppose Home Rule. Irish nationalists had also formed a paramilitary organisation, the Irish Volunteers. It sought to ensure Home Rule was implemented, and it smuggled its own weapons into Ireland a few months after the Ulster Volunteers.[35] Ireland seemed to be on the brink of civil war.[36]

Unionists were in a minority in Ireland as a whole, but a majority in the province of Ulster, especially the counties Antrim, Down, Armagh and Londonderry.[37] Unionists argued that if Home Rule could not be stopped then all or part of Ulster should be excluded from it.[38] In May 1914, the UK Government introduced an Amending Bill to allow for 'Ulster' to be excluded from Home Rule. There was then debate over how much of Ulster should be excluded and for how long. Some Ulster unionists were willing to tolerate the 'loss' of some mainly-Catholic areas of the province.[39] The crisis was interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, and Ireland's involvement in it. The UK Government abandoned the Amending Bill, and instead rushed through a new bill, the Suspensory Act 1914, suspending Home Rule for the duration of the war,[40] with the exclusion of Ulster still to be decided.[41]

Partition of Ireland

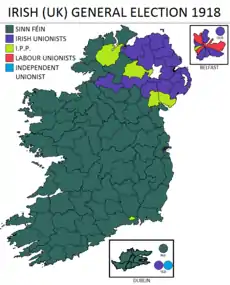

By the end of the war (during which the 1916 Easter Rising had taken place), most Irish nationalists now wanted full independence rather than home rule. In September 1919, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George tasked a committee with planning another home rule bill. Headed by English unionist politician Walter Long, it was known as the 'Long Committee'. It decided that two devolved governments should be established—one for the nine counties of Ulster and one for the rest of Ireland—together with a Council of Ireland for the "encouragement of Irish unity".[42] Most Ulster unionists wanted the territory of the Ulster government to be reduced to six counties so that it would have a larger Protestant unionist majority. They feared that the territory would not last if it included too many Catholics and Irish nationalists. The six counties of Antrim, Down, Armagh, Londonderry, Tyrone and Fermanagh comprised the maximum area unionists believed they could dominate.[43] The area that was to become Northern Ireland amounted to six of the nine counties of Ulster, in spite of the fact that in the last all Ireland election (1918 Irish general election) counties Fermanagh and Tyrone had Sinn Fein/Nationalist Party (Irish Parliamentary Party) majorities.[44]

Events overtook the government. In the 1918 Irish general election, the pro-independence Sinn Féin party won the overwhelming majority of Irish seats. Sinn Féin's elected members boycotted the British parliament and founded a separate Irish parliament (Dáil Éireann), declaring the independent Irish Republic covering the whole island. Many Irish republicans blamed the British establishment for the sectarian divisions in Ireland, and believed that Ulster Unionist defiance would fade once British rule was ended.[45] The British authorities outlawed the Dáil in September 1919,[46] and a guerrilla conflict developed as the Irish Republican Army (IRA) began attacking British forces. This became known as the Irish War of Independence.[47]

.jpg.webp)

Meanwhile, the Government of Ireland Act 1920 passed through the British parliament in 1920. It would divide Ireland into two self-governing UK territories: the six northeastern counties (Northern Ireland) being ruled from Belfast, and the other twenty-six counties (Southern Ireland) being ruled from Dublin. Both would have a shared Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, who would appoint both governments and a Council of Ireland, which the UK Government intended to evolve into an all-Ireland parliament.[48] The Act received royal assent that December, becoming the Government of Ireland Act 1920. It came into force on 3 May 1921,[49][50] partitioning Ireland and creating Northern Ireland. Elections to the Northern parliament were held on 24 May, in which Unionists won most seats. Its parliament first met on 7 June and formed its first devolved government, headed by Unionist Party leader James Craig. Republican and nationalist members refused to attend. King George V addressed the ceremonial opening of the Northern parliament on 22 June.[49]

During 1920–22, in what became Northern Ireland, partition was accompanied by violence "in defence or opposition to the new settlement"[16] – see The Troubles in Northern Ireland (1920–1922). The IRA carried out attacks on British forces in the north-east but was less active than in the south of Ireland. Protestant loyalists attacked the Catholic community in reprisal for IRA actions. In the summer of 1920, sectarian violence erupted in Belfast and Derry, and there were mass burnings of Catholic property in Lisburn and Banbridge.[51]Conflict continued intermittently for two years, mostly in Belfast, which saw "savage and unprecedented" communal violence between Protestant and Catholic civilians. There was rioting, gun battles, and bombings. Homes, businesses, and churches were attacked and people were expelled from workplaces and mixed neighbourhoods.[16] More than 500 were killed[17] and more than 10,000 became refugees, most of them Catholics.[52] The British Army was deployed and the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC) was formed to help the regular police. The USC was almost wholly Protestant and some of its members carried out reprisal attacks on Catholics.[53] A truce between British forces and the IRA was established on 11 July 1921, ending the fighting in most of Ireland. However, communal violence continued in Belfast, and in 1922 the IRA launched a guerrilla offensive in border areas of Northern Ireland.[54]

The Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed between representatives of the UK Government and the Irish Republic on 6 December 1921. This created the Irish Free State. Under the terms of the treaty, Northern Ireland would become part of the Free State unless the government opted out by presenting an address to the king, although in practice partition remained in place.[55]

As expected, the Parliament of Northern Ireland resolved on 7 December 1922 (the day after the establishment of the Irish Free State) to exercise its right to opt out of the Free State by making an address to King George V.[56] The text of the address was:

Most Gracious Sovereign, We, your Majesty's most dutiful and loyal subjects, the Senators and Commons of Northern Ireland in Parliament assembled, having learnt of the passing of the Irish Free State Constitution Act 1922, being the Act of Parliament for the ratification of the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, do, by this humble Address, pray your Majesty that the powers of the Parliament and Government of the Irish Free State shall no longer extend to Northern Ireland.[57]

Shortly afterwards, the Irish Boundary Commission was established to decide on the border between the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland. Owing to the outbreak of the Irish Civil War, the work of the commission was delayed until 1925. The Free State government and Irish nationalists hoped for a large transfer of territory to the Free State, as many border areas had nationalist majorities, leaving the remaining Northern Ireland too small to be viable.[58] However, the commission's final report recommended only small transfers of territory, and in both directions. The Free State, Northern Ireland, and UK governments agreed to suppress the report and accept the status quo, while the UK Government agreed that the Free State would no longer have to pay its share of the UK national debt.[59]

1925–1965

Northern Ireland's border was drawn to give it "a decisive Protestant majority". At the time of its creation, Northern Ireland's population was two-thirds Protestant and one-third Catholic.[13] Most Protestants were unionists/loyalists who sought to maintain Northern Ireland as a part of the United Kingdom, while most Catholics were Irish nationalists/republicans who sought an independent United Ireland. There was mutual self-imposed segregation in Northern Ireland between Protestants and Catholics such as in education, housing, and often employment.[60]

For its first fifty years, Northern Ireland had an unbroken series of Unionist Party governments.[61] Almost every minister of these governments were members of the Protestant Orange Order.[62] Almost all judges and magistrates were Protestant, many of them closely associated with the Unionist Party. Northern Ireland's new police force was the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), which succeeded the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). It too was almost wholly Protestant and lacked operational independence, responding to directions from government ministers. The RUC and the reserve Ulster Special Constabulary (USC) were militarized police forces due to the threat from the IRA. They "had at their disposal the Special Powers Act, a sweeping piece of legislation which allowed arrests without warrant, internment without trial, unlimited search powers, and bans on meetings and publications".[63]

The Nationalist Party was the main political party in opposition to the Unionist governments. However, its elected members often protested by abstaining from the Northern Ireland parliament, and many nationalists did not vote in parliamentary elections.[60] Other early nationalist groups which campaigned against partition included the National League of the North (formed in 1928), the Northern Council for Unity (formed in 1937) and the Irish Anti-Partition League (formed in 1945).[64]

The Unionist governments, and some unionist-dominated local authorities, were accused of discriminating against the Catholic and Irish nationalist minority; especially over gerrymandering of electoral boundaries, the allocation of public housing, public sector employment, and policing. While some individual accusations were unfounded or exaggerated, there are enough proven cases to show "a consistent and irrefutable pattern of deliberate discrimination against Catholics".[65] Decades later, Unionist First Minister of Northern Ireland, David Trimble, said it had been a "cold house" for Catholics.[66]

In June 1940, to encourage the neutral Irish state to join with the Allies of World War II, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill indicated to the Taoiseach Éamon de Valera that the United Kingdom would push for Irish unity, but believing that Churchill could not deliver, de Valera declined the offer.[67] The British did not inform the Government of Northern Ireland that they had made the offer to the Dublin government, and de Valera's rejection was not publicised until 1970.

The Ireland Act 1949 gave the first legal guarantee that the region would not cease to be part of the United Kingdom without the consent of the Parliament of Northern Ireland.

From 1956 to 1962, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) carried out a limited guerrilla campaign in border areas of Northern Ireland, called the Border Campaign. It aimed to destabilize Northern Ireland and bring about an end to partition but failed.[68]

In 1965, Northern Ireland's Prime Minister Terence O'Neill met the Taoiseach, Seán Lemass. It was the first meeting between the two heads of government since partition.[69]

The Troubles

The Troubles, which started in the late 1960s, consisted of about 30 years of recurring acts of intense violence during which 3,254 people were killed[70] with over 50,000 casualties.[71] From 1969 to 2003 there were over 36,900 shooting incidents and over 16,200 bombings or attempted bombings associated with The Troubles.[24] The conflict was caused by the disputed status of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom and the discrimination against the Irish nationalist minority by the dominant unionist majority.[72] From 1967 to 1972 the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), which modelled itself on the US civil rights movement, led a campaign of civil resistance to anti-Catholic discrimination in housing, employment, policing, and electoral procedures. The franchise for local government elections included only rate-payers and their spouses, and so excluded over a quarter of the electorate. While the majority of disenfranchised electors were Protestant, Catholics were over-represented since they were poorer and had more adults still living in the family home.[73]

NICRA's campaign, seen by many unionists as an Irish republican front, and the violent reaction to it proved to be a precursor to a more violent period.[74] As early as 1969, armed campaigns of paramilitary groups began, including the Provisional IRA campaign of 1969–1997 which was aimed at the end of British rule in Northern Ireland and the creation of a United Ireland, and the Ulster Volunteer Force, formed in 1966 in response to the perceived erosion of both the British character and unionist domination of Northern Ireland. The state security forces – the British Army and the police (the Royal Ulster Constabulary) – were also involved in the violence. The UK Government's position is that its forces were neutral in the conflict, trying to uphold law and order in Northern Ireland and the right of the people of Northern Ireland to democratic self-determination. Republicans regarded the state forces as combatants in the conflict, pointing to the collusion between the state forces and the loyalist paramilitaries as proof of this. The "Ballast" investigation by the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland has confirmed that British forces, and in particular the RUC, did collude with loyalist paramilitaries, were involved in murder, and did obstruct the course of justice when such claims had been investigated,[75] although the extent to which such collusion occurred is still disputed.

As a consequence of the worsening security situation, the autonomous regional government for Northern Ireland was suspended in 1972. Alongside the violence, there was a political deadlock between the major political parties in Northern Ireland, including those who condemned the violence, over the future status of Northern Ireland and the form of government there should be within Northern Ireland. In 1973, Northern Ireland held a referendum to determine if it should remain in the United Kingdom, or be part of a united Ireland. The vote went heavily in favour (98.9%) of maintaining the status quo. Approximately 57.5% of the total electorate voted in support, but only 1% of Catholics voted following a boycott organised by the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP).[76]

Peace process

The Troubles were brought to an uneasy end by a peace process that included the declaration of ceasefires by most paramilitary organisations and the complete decommissioning of their weapons, the reform of the police, and the corresponding withdrawal of army troops from the streets and sensitive border areas such as South Armagh and Fermanagh, as agreed by the signatories to the Belfast Agreement (commonly known as the "Good Friday Agreement"). This reiterated the long-held British position, which had never before been fully acknowledged by successive Irish governments, that Northern Ireland will remain within the United Kingdom until a majority of voters in Northern Ireland decides otherwise. The Constitution of Ireland was amended in 1999 to remove a claim of the "Irish nation" to sovereignty over the entire island (in Article 2).[77]

The new Articles 2 and 3, added to the Constitution to replace the earlier articles, implicitly acknowledge that the status of Northern Ireland, and its relationships within the rest of the United Kingdom and with the Republic of Ireland, would only be changed with the agreement of a majority of voters in each jurisdiction. This aspect was also central to the Belfast Agreement which was signed in 1998 and ratified by referendums held simultaneously in both Northern Ireland and the Republic. At the same time, the UK Government recognised for the first time, as part of the prospective, the so-called "Irish dimension": the principle that the people of the island of Ireland as a whole have the right, without any outside interference, to solve the issues between North and South by mutual consent.[78] The latter statement was key to winning support for the agreement from nationalists. It established a devolved power-sharing government, the Northern Ireland Assembly, located on the Stormont Estate, which must consist of both unionist and nationalist parties. These institutions were suspended by the UK Government in 2002 after Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) allegations of spying by people working for Sinn Féin at the Assembly (Stormontgate). The resulting case against the accused Sinn Féin member collapsed.[79]

On 28 July 2005, the Provisional IRA declared an end to its campaign and has since decommissioned what is thought to be all of its arsenal. This final act of decommissioning was performed under the watch of the Independent International Commission on Decommissioning (IICD) and two external church witnesses. Many unionists, however, remained skeptical. The IICD later confirmed that the main loyalist paramilitary groups, the Ulster Defence Association, UVF, and the Red Hand Commando, had decommissioned what is thought to be all of their arsenals, witnessed by former archbishop Robin Eames and a former top civil servant.[80]

Politicians elected to the Assembly at the 2003 Assembly election were called together on 15 May 2006 under the Northern Ireland Act 2006[81] to elect a First Minister and deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland and choose the members of an Executive (before 25 November 2006) as a preliminary step to the restoration of devolved government.

Following the election on 7 March 2007, the devolved government returned on 8 May 2007 with Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) leader Ian Paisley and Sinn Féin deputy leader Martin McGuinness taking office as First Minister and deputy First Minister, respectively.[82] In its white paper on Brexit the United Kingdom government reiterated its commitment to the Belfast Agreement. Concerning Northern Ireland's status, it said that the UK Government's "clearly-stated preference is to retain Northern Ireland's current constitutional position: as part of the UK, but with strong links to Ireland".[83]

Politics

Background

The main political divide in Northern Ireland is between unionists, who wish to see Northern Ireland continue as part of the United Kingdom, and nationalists, who wish to see Northern Ireland unified with the Republic of Ireland, independent from the United Kingdom. These two opposing views are linked to deeper cultural divisions. Unionists are predominantly Ulster Protestant, descendants of mainly Scottish, English, and Huguenot settlers as well as Gaels who converted to one of the Protestant denominations. Nationalists are overwhelmingly Catholic and descend from the population predating the settlement, with a minority from the Scottish Highlands as well as some converts from Protestantism. Discrimination against nationalists under the Stormont government (1921–1972) gave rise to the civil rights movement in the 1960s.[84]

While some unionists argue that discrimination was not just due to religious or political bigotry, but also the result of more complex socio-economic, socio-political and geographical factors,[85] its existence, and the manner in which nationalist anger at it was handled, were a major contributing factor to the Troubles. The political unrest went through its most violent phase between 1968 and 1994.[86]

In 2007, 36% of the population defined themselves as unionist, 24% as nationalist, and 40% defined themselves as neither.[87] According to a 2015 opinion poll, 70% express a long-term preference of the maintenance of Northern Ireland's membership of the United Kingdom (either directly ruled or with devolved government), while 14% express a preference for membership of a united Ireland.[88] This discrepancy can be explained by the overwhelming preference among Protestants to remain a part of the UK (93%), while Catholic preferences are spread across several solutions to the constitutional question including remaining a part of the UK (47%), a united Ireland (32%), Northern Ireland becoming an independent state (4%), and those who "don't know" (16%).[89]

Official voting figures, which reflect views on the "national question" along with issues of the candidate, geography, personal loyalty, and historic voting patterns, show 54% of Northern Ireland voters vote for unionist parties, 42% vote for nationalist parties, and 4% vote "other". Opinion polls consistently show that the election results are not necessarily an indication of the electorate's stance regarding the constitutional status of Northern Ireland. Most of the population of Northern Ireland are at least nominally Christian, mostly Roman Catholic and Protestant denominations. Many voters (regardless of religious affiliation) are attracted to unionism's conservative policies, while other voters are instead attracted to the traditionally leftist Sinn Féin and SDLP and their respective party platforms for democratic socialism and social democracy.[90]

For the most part, Protestants feel a strong connection with Great Britain and wish for Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom. Many Catholics however, generally aspire to a United Ireland or are less certain about how to solve the constitutional question. Protestants have a slight majority in Northern Ireland, according to the latest Northern Ireland Census. The make-up of the Northern Ireland Assembly reflects the appeals of the various parties within the population. Of the 90 Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs), 37 are unionists and 35 are nationalists (the remaining 18 are classified as "other").[91]

Governance

Since 1998, Northern Ireland has had devolved government within the United Kingdom, presided over by the Northern Ireland Assembly and a cross-community government (the Northern Ireland Executive). The UK Government and UK Parliament are responsible for reserved and excepted matters. Reserved matters comprise listed policy areas (such as civil aviation, units of measurement, and human genetics) that Parliament may devolve to the Assembly some time in the future. Excepted matters (such as international relations, taxation and elections) are never expected to be considered for devolution. On all other governmental matters, the Executive together with the 90-member Assembly may legislate for and govern Northern Ireland. Devolution in Northern Ireland is dependent upon participation by members of the Northern Ireland executive in the North/South Ministerial Council, which coordinates areas of cooperation (such as agriculture, education, and health) between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Additionally, "in recognition of the Irish Government's special interest in Northern Ireland", the Government of Ireland and Government of the United Kingdom co-operate closely on non-devolved matters through the British-Irish Intergovernmental Conference.

Elections to the Northern Ireland Assembly are by single transferable vote with five Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) elected from each of 18 parliamentary constituencies. In addition, eighteen representatives (Members of Parliament, MPs) are elected to the lower house of the UK parliament from the same constituencies using the first-past-the-post system. However, not all of those elected take their seats. Sinn Féin MPs, currently seven, refuse to take the oath to serve the King that is required before MPs are allowed to take their seats. In addition, the upper house of the UK parliament, the House of Lords, currently has some 25 appointed members from Northern Ireland.

The Northern Ireland Office represents the UK Government in Northern Ireland on reserved matters and represents Northern Ireland's interests within the UK Government. Additionally, the Republic's government also has the right to "put forward views and proposals" on non-devolved matters about Northern Ireland. The Northern Ireland Office is led by the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, who sits in the Cabinet of the United Kingdom.

Northern Ireland is a distinct legal jurisdiction, separate from the two other jurisdictions in the United Kingdom (England and Wales, and Scotland). Northern Ireland law developed from Irish law that existed before the partition of Ireland in 1921. Northern Ireland is a common law jurisdiction and its common law is similar to that in England and Wales. However, there are important differences in law and procedure between Northern Ireland and England and Wales. The body of statute law affecting Northern Ireland reflects the history of Northern Ireland, including Acts of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, the Northern Ireland Assembly, the former Parliament of Northern Ireland and the Parliament of Ireland, along with some Acts of the Parliament of England and of the Parliament of Great Britain that were extended to Ireland under Poynings' Law between 1494 and 1782.

Descriptions

There is no generally accepted term to describe what Northern Ireland is: province, region, country or something else.[8][9][10] The choice of term can be controversial and can reveal the writer's political preferences.[9] This has been noted as a problem by several writers on Northern Ireland, with no generally recommended solution.[8][9][10]

Owing in part to how the United Kingdom, and Northern Ireland, came into being, there is no legally defined term to describe what Northern Ireland 'is'. There is also no uniform or guiding way to refer to Northern Ireland amongst the agencies of the UK Government. For example, the websites of the Office of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom[92] and the UK Statistics Authority describe the United Kingdom as being made up of four countries, one of these being Northern Ireland.[93] Other pages on the same websites refer to Northern Ireland specifically as a "province" as do publications of the UK Statistics Authority.[94][95] The website of the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency also refers to Northern Ireland as being a province[96] as does the website of the Office of Public Sector Information[97] and other agencies within Northern Ireland.[98] Publications of HM Treasury[99] and the Department of Finance and Personnel of the Northern Ireland Executive,[100] on the other hand, describe Northern Ireland as being a "region of the UK". The UK's submission to the 2007 United Nations Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names defines the UK as being made up of two countries (England and Scotland), one principality (Wales) and one province (Northern Ireland).[101]

Unlike England, Scotland, and Wales, Northern Ireland has no history of being an independent country or of being a nation in its own right.[102] Some writers describe the United Kingdom as being made up of three countries and one province[103] or point out the difficulties with calling Northern Ireland a country.[104] Authors writing specifically about Northern Ireland dismiss the idea that Northern Ireland is a "country" in general terms,[8][10][105] and draw contrasts in this respect with England, Scotland and Wales.[106] Even for the period covering the first 50 years of Northern Ireland's existence, the term country is considered inappropriate by some political scientists on the basis that many decisions were still made in London.[102] The absence of a distinct nation of Northern Ireland, separate within the island of Ireland, is also pointed out as being a problem with using the term[10][107][108] and is in contrast to England, Scotland, and Wales.[109]

Many commentators prefer to use the term "province", although that is also not without problems. It can arouse irritation, particularly among nationalists, for whom the title province is properly reserved for the traditional province of Ulster, of which Northern Ireland comprises six out of nine counties.[9][104] The BBC style guide is to refer to Northern Ireland as a province, and use of the term is common in literature and newspaper reports on Northern Ireland and the United Kingdom. Some authors have described the meaning of this term as being equivocal: referring to Northern Ireland as being a province both of the United Kingdom and the traditional country of Ireland.[107]

"Region" is used by several UK government agencies and the European Union. Some authors choose this word but note that it is "unsatisfactory".[9][10] Northern Ireland can also be simply described as "part of the UK", including by the UK government offices.[92]

Alternative names

Many people inside and outside Northern Ireland use other names for Northern Ireland, depending on their point of view. Disagreement on names, and the reading of political symbolism into the use or non-use of a word, also attaches itself to some urban centres. The most notable example is whether Northern Ireland's second-largest city should be called "Derry" or "Londonderry".

Choice of language and nomenclature in Northern Ireland often reveals the cultural, ethnic, and religious identity of the speaker. Those who do not belong to any group but lean towards one side often tend to use the language of that group. Supporters of unionism in the British media (notably The Daily Telegraph and the Daily Express) regularly call Northern Ireland "Ulster".[110] Many media outlets in the Republic use "North of Ireland" (or simply "the North"),[111][112][113][114][115] as well as the "Six Counties".[116] The New York Times has also used "the North".[117]

Government and cultural organisations in Northern Ireland often use the word "Ulster" in their title; for example, the University of Ulster, the Ulster Museum, the Ulster Orchestra, and BBC Radio Ulster.

Although some news bulletins since the 1990s have opted to avoid all contentious terms and use the official name, Northern Ireland, the term "the North" remains commonly used by broadcast media in the Republic.[111][112][113]

Unionist

- Ulster, strictly speaking, refers to the province of Ulster, of which six of nine historical counties are in Northern Ireland. The term "Ulster" is widely used by unionists and the British press as shorthand for Northern Ireland, and is also favoured by Ulster nationalists.[118] In the past, calls have been made for Northern Ireland's name to be changed to Ulster. This proposal was formally considered by the Government of Northern Ireland in 1937 and by the UK Government in 1949 but no change was made.[119]

- The Province refers to the historic Irish province of Ulster but today is used by some as shorthand for Northern Ireland. The BBC, in its editorial guidance for Reporting the United Kingdom, states that "the Province" is an appropriate secondary synonym for Northern Ireland, while "Ulster" is not. It also suggests that "people of Northern Ireland" is preferred to "British" or "Irish", and the term "mainland" should be avoided in reporting about Great Britain and Northern Ireland.[120]

Nationalist

- North of Ireland – used to avoid using the name given by the British-enacted Government of Ireland Act 1920.

- The Six Counties (na Sé Chontae) – the Republic of Ireland is similarly described as the Twenty-Six Counties.[121] Some of the users of these terms contend that using the official name of the region would imply acceptance of the legitimacy of the Government of Ireland Act.

- The Occupied Six Counties – used by some republicans.[122] The Republic, whose legitimacy is similarly not recognised by republicans opposed to the Belfast Agreement, is described as the "Free State", referring to the Irish Free State, which gained independence (as a Dominion) in 1922.[123]

- British-Occupied Ireland – Similar in tone to the Occupied Six Counties,[124] this term is used by more dogmatic republicans, such as Republican Sinn Féin,[125] who still hold that the Second Dáil was the last legitimate government of Ireland and that all governments since have been foreign-imposed usurpations of Irish national self-determination.[126]

Other

- Norn Iron or "Norniron" – is an informal and affectionate[127] local nickname used to refer to Northern Ireland, derived from the pronunciation of the words "Northern Ireland" in an exaggerated Ulster accent (particularly one from the greater Belfast area). The phrase is seen as a lighthearted way to refer to Northern Ireland, based as it is on regional pronunciation. It often refers to the Northern Ireland national football team.[128]

Geography and climate

Northern Ireland was covered by an ice sheet for most of the last ice age and on numerous previous occasions, the legacy of which can be seen in the extensive coverage of drumlins in Counties Fermanagh, Armagh, Antrim and particularly Down.

The centrepiece of Northern Ireland's geography is Lough Neagh, at 151 square miles (391 km2) the largest freshwater lake both on the island of Ireland and in the British Isles. A second extensive lake system is centred on Lower and Upper Lough Erne in Fermanagh. The largest island of Northern Ireland is Rathlin, off the north Antrim coast. Strangford Lough is the largest inlet in the British Isles, covering 150 km2 (58 sq mi).

There are substantial uplands in the Sperrin Mountains (an extension of the Caledonian mountain belt) with extensive gold deposits, granite Mourne Mountains and basalt Antrim Plateau, as well as smaller ranges in South Armagh and along the Fermanagh–Tyrone border. None of the hills are especially high, with Slieve Donard in the dramatic Mournes reaching 850 metres (2,789 ft), Northern Ireland's highest point. Belfast's most prominent peak is Cavehill.

The volcanic activity which created the Antrim Plateau also formed the geometric pillars of the Giant's Causeway on the north Antrim coast. Also in north Antrim are the Carrick-a-Rede Rope Bridge, Mussenden Temple and the Glens of Antrim.

The Lower and Upper River Bann, River Foyle and River Blackwater form extensive fertile lowlands, with excellent arable land also found in North and East Down, although much of the hill country is marginal and suitable largely for animal husbandry.

The valley of the River Lagan is dominated by Belfast, whose metropolitan area includes over a third of the population of Northern Ireland, with heavy urbanisation and industrialisation along the Lagan Valley and both shores of Belfast Lough.

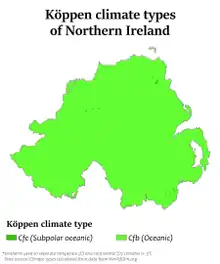

The vast majority of Northern Ireland has a temperate maritime climate, (Cfb in the Köppen climate classification) rather wetter in the west than the east, although cloud cover is very common across the region. The weather is unpredictable at all times of the year, and although the seasons are distinct, they are considerably less pronounced than in interior Europe or the eastern seaboard of North America. Average daytime maximums in Belfast are 6.5 °C (43.7 °F) in January and 17.5 °C (63.5 °F) in July. The highest maximum temperature recorded was 31.4 °C (88.5 °F), registered in July 2021 at Armagh Observatory's weather station.[129] The lowest minimum temperature recorded was −18.7 °C (−1.7 °F) at Castlederg, County Tyrone on 23 December 2010.[130]

Northern Ireland is the least forested part of the United Kingdom and Ireland, and one of the least forested countries in Europe.[131] Until the end of the Middle Ages, the land was heavily forested. Native species include deciduous trees such as oak, ash, hazel, birch, alder, willow, aspen, elm, rowan and hawthorn, as well as evergreen trees such Scots pine, yew and holly.[132] Today, only 8% of Northern Ireland is woodland, and most of this is non-native conifer plantations.[133]

Counties

Northern Ireland consists of six historic counties: County Antrim, County Armagh, County Down, County Fermanagh, County Londonderry,[134] and County Tyrone.

These counties are no longer used for local government purposes; instead, there are eleven districts of Northern Ireland which have different geographical extents. These were created in 2015, replacing the twenty-six districts which previously existed.[135]

Although counties are no longer used for local governmental purposes, they remain a popular means of describing where places are. They are officially used while applying for an Irish passport, which requires one to state one's county of birth. The name of that county then appears in both Irish and English on the passport's information page, as opposed to the town or city of birth on the United Kingdom passport. The Gaelic Athletic Association still uses the counties as its primary means of organisation and fields representative teams of each GAA county. The original system of car registration numbers largely based on counties remains in use. In 2000, the telephone numbering system was restructured into an 8-digit scheme with (except for Belfast) the first digit approximately reflecting the county.

The county boundaries still appear on Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland Maps and the Philip's Street Atlases, among others. With their decline in official use, there is often confusion surrounding towns and cities which lie near county boundaries, such as Belfast and Lisburn, which are split between counties Down and Antrim (the majorities of both cities, however, are in Antrim).

In March 2018, The Sunday Times published its list of Best Places to Live in Britain, including the following places in Northern Ireland: Ballyhackamore near Belfast (overall best for Northern Ireland), Holywood, County Down, Newcastle, County Down, Portrush, County Antrim, Strangford, County Down.[136]

Cities and major towns

| Cities and towns by population[137] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Settlement | Population | Metro population |

| ||

| 1 | Belfast | 334,420 | 671,559 | |||

| 2 | Derry | 84,750 | 237,000 | |||

| 3 | Lisburn [138] | 71,403 | ||||

| 4 | Greater Craigavon | 68,890 | ||||

| 5 | Newtownabbey [138] | 66,120 | ||||

| 6 | Bangor [138] | 62,650 | ||||

| 7 | Ballymena | 30,590 | ||||

| 8 | Newtownards | 28,860 | ||||

| 9 | Newry | 28,080 | ||||

| 10 | Carrickfergus [138] | 27,640 | ||||

Economy

Northern Ireland has traditionally had an industrial economy, most notably in shipbuilding, rope manufacture, and textiles, but the heaviest industry has since been replaced by services, primarily the public sector.

Seventy percent of the economy's revenue comes from the service sector. Apart from the public sector, another important service sector is tourism, which rose to account for over 1% of the economy's revenue in 2004. Tourism has been a major growth area since the end of the Troubles. Key tourism attractions include the historic cities of Derry, Belfast, and Armagh and the many castles in Northern Ireland.

The local economy has seen contraction during the Great Recession. The Executive wishes to gain taxation powers from London, to align Northern Ireland's corporation tax rate with that of the Republic of Ireland.

As in all of the UK, the economy of Northern Ireland was negatively impacted by the lockdowns and travel restrictions necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The tourism and hospitality industry was particularly hard hit. These sectors "have been mandated to close since 26 December 2020, with a very limited number of exceptions" and many restrictions were continuing into April 2021.[139] Hotels and other accommodations, for example, "closed apart from only for work-related stays".[140] Some restrictions were expected to be loosened in mid April but tourism was expected to remain very limited.[141]

Transport

Northern Ireland has underdeveloped transport infrastructure, with most infrastructure concentrated around Greater Belfast, Greater Derry, and Craigavon. Northern Ireland is served by three airports – Belfast International near Antrim, George Best Belfast City integrated into the railway network at Sydenham in East Belfast, and City of Derry in County Londonderry.

Major seaports at Larne and Belfast carry passengers and freight between Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Passenger railways are operated by Northern Ireland Railways. With Iarnród Éireann (Irish Rail), Northern Ireland Railways co-operates in providing the joint Enterprise service between Dublin Connolly and Lanyon Place. The whole of Ireland has a mainline railway network with a gauge of 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm), which is unique in Europe and has resulted in distinct rolling stock designs. The only preserved line of this gauge on the island is the Downpatrick and County Down Railway, which operates heritage steam and diesel locomotives. Main railway lines linking to and from Belfast Great Victoria Street railway station and Lanyon Place railway station are:

- The Derry Line and the Portrush Branch.

- The Larne Line

- The Bangor Line

- The Portadown Line

Main motorways are:

- M1 connecting Belfast to the south and west, ending in Dungannon

- M2 connecting Belfast to the north. An unconnected section of the M2 also by-passes Ballymena

Additional short motorway spurs include:

- M12 connecting the M1 to Portadown

- M22 connecting the M2 to near Randalstown

- M3 connecting the M1 (via the A12) and M2 in Belfast with the A2 dual carriageway to Bangor

- M5 connecting Belfast to Newtownabbey

The cross-border road connecting the ports of Larne in Northern Ireland and Rosslare Harbour in the Republic of Ireland is being upgraded as part of an EU-funded scheme. European route E01 runs from Larne through the island of Ireland, Spain, and Portugal to Seville.

Demographics

.png.webp)

The population of Northern Ireland has risen yearly since 1978. The population at the time of the 2021 census was 1.9 million, having grown 5% over the previous decade.[142] The population in 2011 was 1.8 million, a rise of 7.5% over the previous decade.[143] The current population makes up 2.8% of the UK's population (67 million) and 27% of the island of Ireland's population (7.03 million). The population density is 135 inhabitants / km2.

As of the 2021 census, the population of Northern Ireland is almost entirely white (96.6%).[144] In 2021, 86.5% of the population were born in Northern Ireland, with 4.8% born in Great Britain, 2.1% born in the Republic of Ireland, and 6.5% born elsewhere (more than half of them in another European country).[145] In 2021 the largest non-white ethnic groups were black (0.6%), Indian (0.5%), and Chinese (0.5%).[144] In 2011, 88.8% of the population were born in Northern Ireland, 4.5% in Great Britain, and 2.9% in the Republic of Ireland. 4.3% were born elsewhere; triple the amount there were in 2001.[146]

Religion

At the 2021 census, 42.3% of the population identified as Roman Catholic, 37.3% as Protestant/other Christian, 1.3% as other religions, while 17.4% identified with no religion or did not state one.[147] The biggest of the Protestant/other Christian denominations were the Presbyterian Church (16.6%), the Church of Ireland (11.5%) and the Methodist Church (2.3%).[147] At the 2011 census, 41.5% of the population identified as Protestant/other Christian, 41% as Roman Catholic, 0.8% as other religions, while 17% identified with no religion or did not state one.[148] In terms of background (i.e. religion or religion brought up in), at the 2021 census 45.7% of the population came from a Catholic background, 43.5% from a Protestant background, 1.5% from other religious backgrounds, and 5.6% from non-religious backgrounds.[147] This was the first time since Northern Ireland's creation that there were more people from a Catholic background than Protestant.[149] At the 2011 census, 48% came from a Protestant background, 45% from a Catholic background, 0.9% from other religious backgrounds, and 5.6% from non-religious backgrounds.[148]

In recent censuses, respondents gave their religious identity or religious upbringing as follows:[150][151][147]

| Religion or religious background of Northern Ireland residents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religion / religion of upbringing | 2001 | 2011 | 2021 | |

| Catholic | 43.8% | 45.1% | 45.7% | |

| Protestant and other Christian | 53.1% | 48.4% | 43.5% | |

| Other religions | 0.4% | 0.9% | 1.5% | |

| No religion nor religious upbringing | 2.7% | 5.6% | 9.3% | |

Identity and citizenship

In Northern Ireland censuses, respondents can choose more than one national identity. In 2021:[152]

- 42.8% identified as British, solely or along with other national identities

- 33.3% identified as Irish, solely or along with other national identities

- 31.5% identified as Northern Irish, solely or along with other national identities

The main national identities given in recent censuses were:

| National identity of Northern Ireland residents[151][152] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Identity | 2011 | 2021 | |

| British only | 39.9% | 31.9% | |

| Irish only | 25.3% | 29.1% | |

| Northern Irish only | 20.9% | 19.8% | |

| British & Northern Irish | 6.2% | 8.0% | |

| Irish & Northern Irish | 1.1% | 1.8% | |

| British, Irish & Northern Irish | 1.0% | 1.5% | |

| British & Irish | 0.7% | 0.6% | |

| English, Scottish, or Welsh | 1.6% | 1.5% | |

| All other | 3.4% | 6.0% | |

Several studies and surveys carried out between 1971 and 2006 have indicated that, in general, most Protestants in Northern Ireland see themselves primarily as British, whereas most Catholics see themselves primarily as Irish.[153][154][155][156][157][158][159][160] This does not, however, account for the complex identities within Northern Ireland, given that many of the population regard themselves as "Ulster" or "Northern Irish", either as a primary or secondary identity.

A 2008 survey found that 57% of Protestants described themselves as British, while 32% identified as Northern Irish, 6% as Ulster, and 4% as Irish. Compared to a similar survey in 1998, this shows a fall in the percentage of Protestants identifying as British and Ulster and a rise in those identifying as Northern Irish. The 2008 survey found that 61% of Catholics described themselves as Irish, with 25% identifying as Northern Irish, 8% as British, and 1% as Ulster. These figures were largely unchanged from the 1998 results.[161][162]

People born in Northern Ireland are, with some exceptions, deemed by UK law to be citizens of the United Kingdom. They are also, with similar exceptions, entitled to be citizens of Ireland. This entitlement was reaffirmed in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement between the British and Irish governments, which provides that:

...it is the birthright of all the people of Northern Ireland to identify themselves and be accepted as Irish or British, or both, as they may so choose, and accordingly [the two governments] confirm that their right to hold both British and Irish citizenship is accepted by both Governments and would not be affected by any future change in the status of Northern Ireland.

As a result of the Agreement, the Constitution of the Republic of Ireland was amended. The current wording provides that people born in Northern Ireland are entitled to be Irish citizens on the same basis as people from any other part of the island.[163]

Neither government, however, extends its citizenship to all persons born in Northern Ireland. Both governments exclude some people born in Northern Ireland, in particular persons born without one parent who is a British or Irish citizen. The Irish restriction was given effect by the twenty-seventh amendment to the Irish Constitution in 2004. The position in UK nationality law is that most of those born in Northern Ireland are UK nationals, whether or not they so choose. Renunciation of British citizenship requires the payment of a fee, currently £372.[164]

In recent censuses, residents said they held the following passports:[151][165]

| Passports held by Northern Ireland residents | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Passport | 2011 | 2021 | |

| United Kingdom | 59.1% | 52.6% | |

| Ireland | 20.8% | 32.3% | |

| European countries | 2.2% | 3.9% | |

| Other countries in world | 1.1% | 1.6% | |

| No passport | 18.9% | 15.9% | |

Languages

English is spoken as a first language by 95.4% of the Northern Ireland population.[166] It is the de facto official language and the Administration of Justice (Language) Act (Ireland) 1737 prohibits the use of languages other than English in legal proceedings.

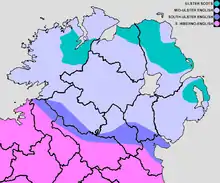

Under the Good Friday Agreement, Irish and Ulster Scots (an Ulster dialect of the Scots language, sometimes known as Ullans), are recognised as "part of the cultural wealth of Northern Ireland".[167] Two all-island bodies for the promotion of these were created under the Agreement: Foras na Gaeilge, which promotes the Irish language, and the Ulster Scots Agency, which promotes the Ulster-Scots dialect and culture. These operate separately under the aegis of the North/South Language Body, which reports to the North/South Ministerial Council.

The UK Government in 2001 ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Irish (in Northern Ireland) was specified under Part III of the Charter, with a range of specific undertakings about education, translation of statutes, interaction with public authorities, the use of placenames, media access, support for cultural activities, and other matters. A lower level of recognition was accorded to Ulster-Scots, under Part II of the Charter.[168]

English

The dialect of English spoken in Northern Ireland shows influence from the lowland Scots language.[169] There are supposedly some minute differences in pronunciation between Protestants and Catholics, for instance; the name of the letter h, which Protestants tend to pronounce as "aitch", as in British English, and Catholics tend to pronounce as "haitch", as in Hiberno-English. However, geography is a much more important determinant of dialect than religious background.

Irish

The Irish language (Irish: an Ghaeilge), or Gaelic, is the second most spoken language in Northern Ireland and is a native language of Ireland.[170] It was spoken predominantly throughout what is now Northern Ireland before the Ulster Plantations in the 17th century and most place names in Northern Ireland are anglicised versions of a Gaelic name. Today, the language is often associated with Irish nationalism (and thus with Catholics). However, in the 19th century, the language was seen as a common heritage, with Ulster Protestants playing a leading role in the Gaelic revival.[171]

In the 2021 census, 12.4% (compared with 10.7% in 2011) of the population of Northern Ireland claimed "some knowledge of Irish" and 3.9% (compared with 3.7% in 2011) reported being able to "speak, read, write and understand" Irish.[143][166] In another survey, from 1999, 1% of respondents said they spoke it as their main language at home.[172]

The dialect spoken in Northern Ireland, Ulster Irish, has two main types, East Ulster Irish and Donegal Irish (or West Ulster Irish),[173] is the one closest to Scottish Gaelic (which developed into a separate language from Irish Gaelic in the 17th century). Some words and phrases are shared with Scots Gaelic, and the dialects of east Ulster – those of Rathlin Island and the Glens of Antrim – were very similar to the dialect of Argyll, the part of Scotland nearest to Ireland. And those dialects of Armagh and Down were also very similar to the dialects of Galloway.

The use of the Irish language in Northern Ireland today is politically sensitive. The erection by some district councils of bilingual street names in both English and Irish,[174] invariably in predominantly nationalist districts, is resisted by unionists who claim that it creates a "chill factor" and thus harms community relationships. Efforts by members of the Northern Ireland Assembly to legislate for some official uses of the language have failed to achieve the required cross-community support. In May 2022, the UK Government proposed a bill in the House of Lords to make Irish an official language (and support Ulster Scots) in Northern Ireland and to create an Irish Language Commissioner.[175][176] There has recently been an increase in interest in the language among unionists in East Belfast.[177]

Ulster Scots

Ulster Scots comprises varieties of the Scots language spoken in Northern Ireland. For a native English speaker, "[Ulster Scots] is comparatively accessible, and even at its most intense can be understood fairly easily with the help of a glossary."[178]

Along with the Irish language, the Good Friday Agreement recognised the dialect as part of Northern Ireland's unique culture and the St Andrews Agreement recognised the need to "enhance and develop the Ulster Scots language, heritage and culture".[179]

At the time of the 2021 census, approximately 1.1% (compared to 0.9% in 2011) of the population claimed to be able to speak, read, write and understand Ulster-Scots, while 10.4% (compared to 8.1% in 2011) professed to have "some ability".[143][166][172]

Sign languages

The most common sign language in Northern Ireland is Northern Ireland Sign Language (NISL). However, because in the past Catholic families tended to send their deaf children to schools in Dublin where Irish Sign Language (ISL) is commonly used, ISL is still common among many older deaf people from Catholic families.

Irish Sign Language (ISL) has some influence from the French family of sign language, which includes American Sign Language (ASL). NISL takes a large component from the British family of sign language (which also includes Auslan) with many borrowings from ASL. It is described as being related to Irish Sign Language at the syntactic level while much of the lexicon is based on British Sign Language (BSL).[180]

As of March 2004 the UK Government recognises only British Sign Language and Irish Sign Language as the official sign languages used in Northern Ireland.[181][182]

Culture

.JPG.webp)

Northern Ireland shares both the culture of Ireland and the culture of the United Kingdom.

Parades are a prominent feature of Northern Ireland society,[183] more so than in the rest of Ireland or the United Kingdom. Most are held by Protestant fraternities such as the Orange Order, and Ulster loyalist marching bands. Each summer, during the "marching season", these groups have hundreds of parades, deck streets with British flags, bunting and specially-made arches, and light large towering bonfires in the "Eleventh Night" celebrations.[184] The biggest parades are held on 12 July (The Twelfth). There is often tension when these activities take place near Catholic neighbourhoods, which sometimes leads to violence.[185]

Since the end of the Troubles, Northern Ireland has witnessed rising numbers of tourists. Attractions include cultural festivals, musical and artistic traditions, countryside and geographical sites of interest, public houses, welcoming hospitality, and sports (especially golf and fishing). Since 1987 public houses have been allowed to open on Sundays, despite some opposition.

The Ulster Cycle is a large body of prose and verse centring on the traditional heroes of the Ulaid in what is now eastern Ulster. This is one of the four major cycles of Irish mythology. The cycle centres on the reign of Conchobar mac Nessa, who is said to have been the king of Ulster around the 1st century. He ruled from Emain Macha (now Navan Fort near Armagh), and had a fierce rivalry with queen Medb and king Ailill of Connacht and their ally, Fergus mac Róich, former king of Ulster. The foremost hero of the cycle is Conchobar's nephew Cúchulainn, who features in the epic prose/poem An Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley, a casus belli between Ulster and Connaught).

Symbols

.svg.png.webp)

.JPG.webp)

Northern Ireland comprises a patchwork of communities whose national loyalties are represented in some areas by flags flown from flagpoles or lamp posts. The Union Jack and the former Northern Ireland flag are flown in many loyalist areas, and the Tricolour, adopted by republicans as the flag of Ireland in 1916,[187] is flown in some republican areas. Even kerbstones in some areas are painted red-white-blue or green-white-orange, depending on whether local people express unionist/loyalist or nationalist/republican sympathies.[188]

The official flag is that of the state having sovereignty over the territory, i.e. the Union Flag.[189] The former Northern Ireland flag, also known as the "Ulster Banner" or "Red Hand Flag", is a banner derived from the coat of arms of the Government of Northern Ireland until 1972. Since 1972, it has had no official status. The Union Flag and the Ulster Banner are used exclusively by unionists. The UK flags policy states that in Northern Ireland, "The Ulster flag and the Cross of St Patrick have no official status and, under the Flags Regulations, are not permitted to be flown from Government Buildings."[190][191]

The Irish Rugby Football Union and the Church of Ireland have used the Saint Patrick's Saltire or "Cross of St Patrick". This red saltire on a white field was used to represent Ireland in the flag of the United Kingdom. It is still used by some British army regiments. Foreign flags are also found, such as the Palestinian flags in some nationalist areas and Israeli flags in some unionist areas.[192]

The United Kingdom national anthem of "God Save the King" is often played at state events in Northern Ireland. At the Commonwealth Games and some other sporting events, the Northern Ireland team uses the Ulster Banner as its flag—notwithstanding its lack of official status—and the Londonderry Air (usually set to lyrics as Danny Boy), which also has no official status, as its national anthem.[193][194] The Northern Ireland national football team also uses the Ulster Banner as its flag but uses "God Save The King" as its anthem.[195] Major Gaelic Athletic Association matches are opened by the national anthem of the Republic of Ireland, "Amhrán na bhFiann (The Soldier's Song)", which is also used by most other all-Ireland sporting organisations.[196] Since 1995, the Ireland rugby union team has used a specially commissioned song, "Ireland's Call" as the team's anthem. The Irish national anthem is also played at Dublin home matches, being the anthem of the host country.[197]

Northern Irish murals have become well-known features of Northern Ireland, depicting past and present events and documenting peace and cultural diversity. Almost 2,000 murals have been documented in Northern Ireland since the 1970s.

Sport

In Northern Ireland, sport is popular and important in the lives of many people. Sports tend to be organised on an all-Ireland basis, with a single team for the whole island.[198] The most notable exception is association football, which has separate governing bodies for each jurisdiction.[198]

Association football

The Irish Football Association (IFA) serves as the organising body for association football in Northern Ireland, with the Northern Ireland Football League (NIFL) responsible for the independent administration of the three divisions of national domestic football, as well as the Northern Ireland Football League Cup.

The highest level of competition within Northern Ireland are the NIFL Premiership and the NIFL Championship. However, many players from Northern Ireland compete with clubs in England and Scotland.

NIFL clubs are semi-professional or Intermediate.NIFL Premiership clubs are also eligible to compete in the UEFA Champions League and UEFA Europa League with the league champions entering the Champions league second qualifying round and the 2nd placed league finisher, the European play-off winners and the Irish Cup winners entering the Europa League second qualifying round. No clubs have ever reached the group stage.

Despite Northern Ireland's small population, the Northern Ireland national football team qualified for the 1958 FIFA World Cup, 1982 FIFA World Cup and 1986 FIFA World Cup, making it to the quarter-finals in 1958 and 1982 and made it the first knockout round in the European Championships in 2016.

Rugby union

The six counties of Northern Ireland are among the nine governed by the Ulster branch of the Irish Rugby Football Union, the governing body of rugby union in Ireland. Ulster is one of the four professional provincial teams in Ireland and competes in the United Rugby Championship and European Cup. It won the European Cup in 1999.

In international competitions, the Ireland national rugby union team's recent successes include four Triple Crowns between 2004 and 2009 and a Grand Slam in 2009 in the Six Nations Championship.

Cricket

The Ireland cricket team represents both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. It is a full member of the International Cricket Council, having been granted Test status and full membership by the ICC in June 2017. The side competes in Test cricket, the highest level of competitive cricket in the international arena, and is one of the 12 full-member countries of the ICC.

Ireland men's side has played in the Cricket World Cup and T20 World Cup and has won the ICC Intercontinental Cup four times. The women's side has played in the Women's World Cup. One of the men's side's regular international venues is Stormont in Belfast.

Gaelic games

Gaelic games include Gaelic football, hurling (and camogie), Gaelic handball and rounders. Of the four, football is the most popular in Northern Ireland. Players play for local clubs with the best being selected for their county teams. The Ulster GAA is the branch of the Gaelic Athletic Association that is responsible for the nine counties of Ulster, which include the six of Northern Ireland.

These nine county teams participate in the Ulster Senior Football Championship, Ulster Senior Hurling Championship, All-Ireland Senior Football Championship and All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship.

Recent successes for Northern Ireland teams include Armagh's 2002 All-Ireland Senior Football Championship win and Tyrone GAA's wins in 2003, 2005, 2008, and 2021.

Golf

.jpg.webp)

Perhaps Northern Ireland's most notable successes in professional sport have come in golf. Northern Ireland has contributed more major champions in the modern era than any other European country, with three in the space of just 14 months from the U.S. Open in 2010 to The Open Championship in 2011. Notable golfers include Fred Daly (winner of The Open in 1947), Ryder Cup players Ronan Rafferty and David Feherty, leading European Tour professionals David Jones, Michael Hoey (a five-time winner on the tour) and Gareth Maybin, as well as three recent major winners Graeme McDowell (winner of the U.S. Open in 2010, the first European to do so since 1970), Rory McIlroy (winner of four majors) and Darren Clarke (winner of The Open in 2011).[199][200] Northern Ireland has also contributed several players to the Great Britain and Ireland Walker Cup team, including Alan Dunbar and Paul Cutler who played on the victorious 2011 team in Scotland. Dunbar also won The Amateur Championship in 2012, at Royal Troon.

The Golfing Union of Ireland, the governing body for men's and boy's amateur golf throughout Ireland and the oldest golfing union in the world, was founded in Belfast in 1891. Northern Ireland's golf courses include the Royal Belfast Golf Club (the earliest, formed in 1881), Royal Portrush Golf Club, which is the only course outside Great Britain to have hosted The Open Championship, and Royal County Down Golf Club (Golf Digest magazine's top-rated course outside the United States).[201][202]

Snooker

Northern Ireland has produced two world snooker champions; Alex Higgins, who won the title in 1972 and 1982, and Dennis Taylor, who won in 1985. The highest-ranked Northern Ireland professional on the world circuit presently is Mark Allen from County Antrim. The sport is governed locally by the Northern Ireland Billiards and Snooker Association who run regular ranking tournaments and competitions.

Motorcycle racing

Motorcycle racing is a particularly popular sport during the summer months, with the main meetings of the season attracting some of the largest crowds to any outdoor sporting event in the whole of Ireland.[203] Two of the three major international road race meetings are held in Northern Ireland, these being the North West 200[204] and the Ulster Grand Prix. In addition racing on purpose built circuits take place at Kirkistown and Bishop's Court,[205] whilst smaller road race meetings are held such as the Cookstown 100, the Armoy Road Races[206] and the Tandragee 100[207] all of which form part of the Irish National Road Race Championships[208] and which have produced some of the greatest motorcycle racers in the history of the sport, notably Joey Dunlop.

Motor racing

Although Northern Ireland lacks an international automobile racecourse, two Northern Irish drivers have finished inside the top two of Formula One, with John Watson achieving the feat in the 1982 Formula One season and Eddie Irvine doing the same in 1999 Formula One season. The largest course and the only Motor Sports Association-licensed track for UK-wide competition is Kirkistown Circuit.[209]

Rugby league

The Ireland national rugby league team has participated in the Emerging Nations Tournament (1995), the Super League World Nines (1996), the World Cup (2000, 2008, 2013, 2017, 2021), European Nations Cup (since 2003) and Victory Cup (2004).

The Ireland A rugby league team competes annually in the Amateur Four Nations competition (since 2002) and the St Patrick's Day Challenge (since 1995).

Ice hockey

The Belfast Giants have competed in the Elite Ice Hockey League since the 2000–01 season and are the sole Northern Irish team in the league. The team's roster has featured Northern Irish-born players such as Mark Morrison, Graeme Walton and Gareth Roberts among others.[210]

Geraldine Heaney, an Olympic gold medalist and one of the first women inducted into the IIHF Hall of Fame, competed internationally for Canada but was born in Northern Ireland.[211]

Owen Nolan, (born 12 February 1972) is a Canadian former professional ice hockey player born in Northern Ireland. He was drafted 1st overall in the 1990 NHL Draft by the Quebec Nordiques.[212]

Professional wrestling

In 2007, after the closure of UCW (Ulster Championship Wrestling) which was a wrestling promotion, PWU formed, standing for Pro Wrestling Ulster. The wrestling promotion features championships, former WWE superstars and local independent wrestlers. Events and IPPV's throughout Northern Ireland.[213]

Education

Unlike most areas of the United Kingdom, in the last year of primary school, many children sit entrance examinations for grammar schools.