Global financial system

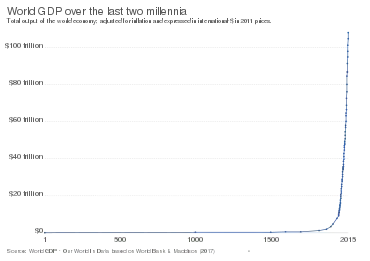

The global financial system is the worldwide framework of legal agreements, institutions, and both formal and informal economic actors that together facilitate international flows of financial capital for purposes of investment and trade financing. Since emerging in the late 19th century during the first modern wave of economic globalization, its evolution is marked by the establishment of central banks, multilateral treaties, and intergovernmental organizations aimed at improving the transparency, regulation, and effectiveness of international markets.[1][2]: 74 [3]: 1 In the late 1800s, world migration and communication technology facilitated unprecedented growth in international trade and investment. At the onset of World War I, trade contracted as foreign exchange markets became paralyzed by money market illiquidity. Countries sought to defend against external shocks with protectionist policies and trade virtually halted by 1933, worsening the effects of the global Great Depression until a series of reciprocal trade agreements slowly reduced tariffs worldwide. Efforts to revamp the international monetary system after World War II improved exchange rate stability, fostering record growth in global finance.

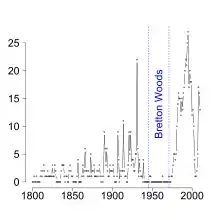

A series of currency devaluations and oil crises in the 1970s led most countries to float their currencies. The world economy became increasingly financially integrated in the 1980s and 1990s due to capital account liberalization and financial deregulation. A series of financial crises in Europe, Asia, and Latin America followed with contagious effects due to greater exposure to volatile capital flows. The global financial crisis, which originated in the United States in 2007, quickly propagated among other nations and is recognized as the catalyst for the worldwide Great Recession. A market adjustment to Greece's noncompliance with its monetary union in 2009 ignited a sovereign debt crisis among European nations known as the Eurozone crisis. The history of international finance shows a U-shaped pattern in international capital flows: high prior to 1914 after 1989, but lower in between.[4] The volatility of capital flows has been greater since the 1970s than in previous periods.[4]

A country's decision to operate an open economy and globalize its financial capital carries monetary implications captured by the balance of payments. It also renders exposure to risks in international finance, such as political deterioration, regulatory changes, foreign exchange controls, and legal uncertainties for property rights and investments. Both individuals and groups may participate in the global financial system. Consumers and international businesses undertake consumption, production, and investment. Governments and intergovernmental bodies act as purveyors of international trade, economic development, and crisis management. Regulatory bodies establish financial regulations and legal procedures, while independent bodies facilitate industry supervision. Research institutes and other associations analyze data, publish reports and policy briefs, and host public discourse on global financial affairs.

While the global financial system is edging toward greater stability, governments must deal with differing regional or national needs. Some nations are trying to systematically discontinue unconventional monetary policies installed to cultivate recovery, while others are expanding their scope and scale. Emerging market policymakers face a challenge of precision as they must carefully institute sustainable macroeconomic policies during extraordinary market sensitivity without provoking investors to retreat their capital to stronger markets. Nations' inability to align interests and achieve international consensus on matters such as banking regulation has perpetuated the risk of future global financial catastrophes. Thereby, necessitating initiative like the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 10 aimed at improving regulation and monitoring of global financial systems.[5]

History of international financial architecture

Emergence of financial globalization: 1870–1914

The world experienced substantial changes in the late 19th century which created an environment favorable to an increase in and development of international financial centers. Principal among such changes were unprecedented growth in capital flows and the resulting rapid financial center integration, as well as faster communication. Before 1870, London and Paris existed as the world's only prominent financial centers.[6]: 1 Soon after, Berlin and New York grew to become major centres providing financial services for their national economies. An array of smaller international financial centers became important as they found market niches, such as Amsterdam, Brussels, Zurich, and Geneva. London remained the leading international financial center in the four decades leading up to World War I.[2]: 74–75 [7]: 12–15

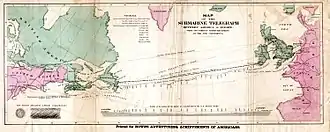

The first modern wave of economic globalization began during the period of 1870–1914, marked by transportation expansion, record levels of migration, enhanced communications, trade expansion, and growth in capital transfers.[2]: 75 During the mid-nineteenth century, the passport system in Europe dissolved as rail transport expanded rapidly. Most countries issuing passports did not require their carry, thus people could travel freely without them.[8] The standardization of international passports would not arise until 1980 under the guidance of the United Nations' International Civil Aviation Organization.[9] From 1870 to 1915, 36 million Europeans migrated away from Europe. Approximately 25 million (or 70%) of these travelers migrated to the United States, while most of the rest reached Canada, Australia and Brazil. Europe itself experienced an influx of foreigners from 1860 to 1910, growing from 0.7% of the population to 1.8%. While the absence of meaningful passport requirements allowed for free travel, migration on such an enormous scale would have been prohibitively difficult if not for technological advances in transportation, particularly the expansion of railway travel and the dominance of steam-powered boats over traditional sailing ships. World railway mileage grew from 205,000 kilometers in 1870 to 925,000 kilometers in 1906, while steamboat cargo tonnage surpassed that of sailboats in the 1890s. Advancements such as the telephone and wireless telegraphy (the precursor to radio) revolutionized telecommunication by providing instantaneous communication. In 1866, the first transatlantic cable was laid beneath the ocean to connect London and New York, while Europe and Asia became connected through new landlines.[2]: 75–76 [10]: 5

Economic globalization grew under free trade, starting in 1860 when the United Kingdom entered into a free trade agreement with France known as the Cobden–Chevalier Treaty. However, the golden age of this wave of globalization endured a return to protectionism between 1880 and 1914. In 1879, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck introduced protective tariffs on agricultural and manufacturing goods, making Germany the first nation to institute new protective trade policies. In 1892, France introduced the Méline tariff, greatly raising customs duties on both agricultural and manufacturing goods. The United States maintained strong protectionism during most of the nineteenth century, imposing customs duties between 40 and 50% on imported goods. Despite these measures, international trade continued to grow without slowing. Paradoxically, foreign trade grew at a much faster rate during the protectionist phase of the first wave of globalization than during the free trade phase sparked by the United Kingdom.[2]: 76–77

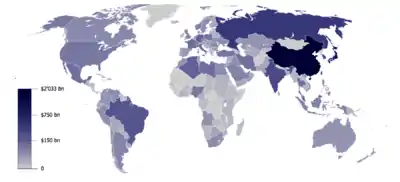

Unprecedented growth in foreign investment from the 1880s to the 1900s served as the core driver of financial globalization. The worldwide total of capital invested abroad amounted to US$44 billion in 1913 ($1.02 trillion in 2012 dollars[11]), with the greatest share of foreign assets held by the United Kingdom (42%), France (20%), Germany (13%), and the United States (8%). The Netherlands, Belgium, and Switzerland together held foreign investments on par with Germany at around 12%.[2]: 77–78

Panic of 1907

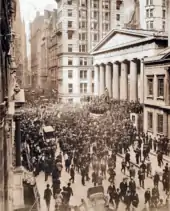

In October 1907, the United States experienced a bank run on the Knickerbocker Trust Company, forcing the trust to close on October 23, 1907, provoking further reactions. The panic was alleviated when U.S. Secretary of the Treasury George B. Cortelyou and John Pierpont "J.P." Morgan deposited $25 million and $35 million, respectively, into the reserve banks of New York City, enabling withdrawals to be fully covered. The bank run in New York led to a money market crunch which occurred simultaneously as demands for credit heightened from cereal and grain exporters. Since these demands could only be serviced through the purchase of substantial quantities of gold in London, the international markets became exposed to the crisis. The Bank of England had to sustain an artificially high discount lending rate until 1908. To service the flow of gold to the United States, the Bank of England organized a pool from among twenty-four nations, for which the Banque de France temporarily lent £3 million (GBP, 305.6 million in 2012 GBP[12]) in gold.[2]: 123–124

Birth of the U.S. Federal Reserve System: 1913

The United States Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act in 1913, giving rise to the Federal Reserve System. Its inception drew influence from the Panic of 1907, underpinning legislators' hesitance in trusting individual investors, such as John Pierpont Morgan, to serve again as a lender of last resort. The system's design also considered the findings of the Pujo Committee's investigation of the possibility of a money trust in which Wall Street's concentration of influence over national financial matters was questioned and in which investment bankers were suspected of unusually deep involvement in the directorates of manufacturing corporations. Although the committee's findings were inconclusive, the very possibility was enough to motivate support for the long-resisted notion of establishing a central bank. The Federal Reserve's overarching aim was to become the sole lender of last resort and to resolve the inelasticity of the United States' money supply during significant shifts in money demand. In addition to addressing the underlying issues that precipitated the international ramifications of the 1907 money market crunch, New York's banks were liberated from the need to maintain their own reserves and began undertaking greater risks. New access to rediscount facilities enabled them to launch foreign branches, bolstering New York's rivalry with London's competitive discount market.[2]: 123–124 [7]: 53 [13]: 18 [14]

Interwar period: 1915–1944

Economists have referred to the onset of World War I as the end of an age of innocence for foreign exchange markets, as it was the first geopolitical conflict to have a destabilizing and paralyzing impact. The United Kingdom declared war on Germany on August 4, 1914 following Germany's invasion of France and Belgium. In the weeks prior, the foreign exchange market in London was the first to exhibit distress. European tensions and increasing political uncertainty motivated investors to chase liquidity, prompting commercial banks to borrow heavily from London's discount market. As the money market tightened, discount lenders began rediscounting their reserves at the Bank of England rather than discounting new pounds sterling. The Bank of England was forced to raise discount rates daily for three days from 3% on July 30 to 10% by August 1. As foreign investors resorted to buying pounds for remittance to London just to pay off their newly maturing securities, the sudden demand for pounds led the pound to appreciate beyond its gold value against most major currencies, yet sharply depreciate against the French franc after French banks began liquidating their London accounts. Remittance to London became increasingly difficult and culminated in a record exchange rate of US$6.50/GBP. Emergency measures were introduced in the form of moratoria and extended bank holidays, but to no effect as financial contracts became informally unable to be negotiated and export embargoes thwarted gold shipments. A week later, the Bank of England began to address the deadlock in the foreign exchange markets by establishing a new channel for transatlantic payments whereby participants could make remittance payments to the U.K. by depositing gold designated for a Bank of England account with Canada's Minister of Finance, and in exchange receive pounds sterling at an exchange rate of $4.90. Approximately US$104 million in remittances flowed through this channel in the next two months. However, pound sterling liquidity ultimately did not improve due to inadequate relief for merchant banks receiving sterling bills. As the pound sterling was the world's reserve currency and leading vehicle currency, market illiquidity and merchant banks' hesitance to accept sterling bills left currency markets paralyzed.[13]: 23–24

The U.K. government attempted several measures to revive the London foreign exchange market, the most notable of which were implemented on September 5 to extend the previous moratorium through October and allow the Bank of England to temporarily loan funds to be paid back upon the end of the war in an effort to settle outstanding or unpaid acceptances for currency transactions. By mid-October, the London market began functioning properly as a result of the September measures. The war continued to present unfavorable circumstances for the foreign exchange market, such as the London Stock Exchange's prolonged closure, the redirection of economic resources to support a transition from producing exports to producing military armaments, and myriad disruptions of freight and mail. The pound sterling enjoyed general stability throughout World War I, in large part due to various steps taken by the U.K. government to influence the pound's value in ways that yet provided individuals with the freedom to continue trading currencies. Such measures included open market interventions on foreign exchange, borrowing in foreign currencies rather than in pounds sterling to finance war activities, outbound capital controls, and limited import restrictions.[13]: 25–27

In 1930, the Allied powers established the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). The principal purposes of the BIS were to manage the scheduled payment of Germany's reparations imposed by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, and to function as a bank for central banks around the world. Nations may hold a portion of their reserves as deposits with the institution. It also serves as a forum for central bank cooperation and research on international monetary and financial matters. The BIS also operates as a general trustee and facilitator of financial settlements between nations.[2]: 182 [15]: 531–532 [16]: 56–57 [17]: 269

Smoot–Hawley tariff of 1930

U.S. President Herbert Hoover signed the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act into law on June 17, 1930. The tariff's aim was to protect agriculture in the United States, but congressional representatives ultimately raised tariffs on a host of manufactured goods resulting in average duties as high as 53% on over a thousand various goods. Twenty-five trading partners responded in kind by introducing new tariffs on a wide range of U.S. goods. Hoover was pressured and compelled to adhere to the Republican Party's 1928 platform, which sought protective tariffs to alleviate market pressures on the nation's struggling agribusinesses and reduce the domestic unemployment rate. The culmination of the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression heightened fears, further pressuring Hoover to act on protective policies against the advice of Henry Ford and over 1,000 economists who protested by calling for a veto of the act.[10]: 175–176 [17]: 186–187 [18]: 43–44 Exports from the United States plummeted 60% from 1930 to 1933.[10]: 118 Worldwide international trade virtually ground to a halt.[19]: 125–126 The international ramifications of the Smoot-Hawley tariff, comprising protectionist and discriminatory trade policies and bouts of economic nationalism, are credited by economists with prolongment and worldwide propagation of the Great Depression.[3]: 2 [19]: 108 [20]: 33

Formal abandonment of the Gold Standard

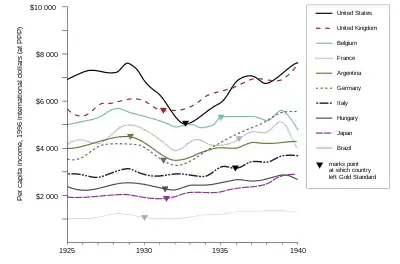

The classical gold standard was established in 1821 by the United Kingdom as the Bank of England enabled redemption of its banknotes for gold bullion. France, Germany, the United States, Russia, and Japan each embraced the standard one by one from 1878 to 1897, marking its international acceptance. The first departure from the standard occurred in August 1914 when these nations erected trade embargoes on gold exports and suspended redemption of gold for banknotes. Following the end of World War I on November 11, 1918, Austria, Hungary, Germany, Russia, and Poland began experiencing hyperinflation. Having informally departed from the standard, most currencies were freed from exchange rate fixing and allowed to float. Most countries throughout this period sought to gain national advantages and bolster exports by depreciating their currency values to predatory levels. A number of countries, including the United States, made unenthusiastic and uncoordinated attempts to restore the former gold standard. The early years of the Great Depression brought about bank runs in the United States, Austria, and Germany, which placed pressures on gold reserves in the United Kingdom to such a degree that the gold standard became unsustainable. Germany became the first nation to formally abandon the post-World War I gold standard when the Dresdner Bank implemented foreign exchange controls and announced bankruptcy on July 15, 1931. In September 1931, the United Kingdom allowed the pound sterling to float freely. By the end of 1931, a host of countries including Austria, Canada, Japan, and Sweden abandoned gold. Following widespread bank failures and a hemorrhaging of gold reserves, the United States broke free of the gold standard in April 1933. France would not follow suit until 1936 as investors fled from the franc due to political concerns over Prime Minister Léon Blum's government.[13]: 58 [19]: 414 [20]: 32–33

Trade liberalization in the United States

The disastrous effects of the Smoot–Hawley tariff proved difficult for Herbert Hoover's 1932 re-election campaign. Franklin D. Roosevelt became the 32nd U.S. president and the Democratic Party worked to reverse trade protectionism in favor of trade liberalization. As an alternative to cutting tariffs across all imports, Democrats advocated for trade reciprocity. The U.S. Congress passed the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act in 1934, aimed at restoring global trade and reducing unemployment. The legislation expressly authorized President Roosevelt to negotiate bilateral trade agreements and reduce tariffs considerably. If a country agreed to cut tariffs on certain commodities, the U.S. would institute corresponding cuts to promote trade between the two nations. Between 1934 and 1947, the U.S. negotiated 29 such agreements and the average tariff rate decreased by approximately one third during this same period. The legislation contained an important most-favored-nation clause, through which tariffs were equalized to all countries, such that trade agreements would not result in preferential or discriminatory tariff rates with certain countries on any particular import, due to the difficulties and inefficiencies associated with differential tariff rates. The clause effectively generalized tariff reductions from bilateral trade agreements, ultimately reducing worldwide tariff rates.[10]: 176–177 [17]: 186–187 [19]: 108

Rise of the Bretton Woods financial order: 1945

As the inception of the United Nations as an intergovernmental entity slowly began formalizing in 1944, delegates from 44 of its early member states met at a hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire for the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, now commonly referred to as the Bretton Woods conference. Delegates remained cognizant of the effects of the Great Depression, struggles to sustain the international gold standard during the 1930s, and related market instabilities. Whereas previous discourse on the international monetary system focused on fixed versus floating exchange rates, Bretton Woods delegates favored pegged exchange rates for their flexibility. Under this system, nations would peg their exchange rates to the U.S. dollar, which would be convertible to gold at US$35 per ounce.[10]: 448 [21]: 34 [22]: 3 [23]: 6 This arrangement is commonly referred to as the Bretton Woods system. Rather than maintaining fixed rates, nations would peg their currencies to the U.S. dollar and allow their exchange rates to fluctuate within a 1% band of the agreed-upon parity. To meet this requirement, central banks would intervene via sales or purchases of their currencies against the dollar.[15]: 491–493 [17]: 296 [24]: 21

Members could adjust their pegs in response to long-run fundamental disequilibria in the balance of payments, but were responsible for correcting imbalances via fiscal and monetary policy tools before resorting to repegging strategies.[10]: 448 [25]: 22 The adjustable pegging enabled greater exchange rate stability for commercial and financial transactions which fostered unprecedented growth in international trade and foreign investment. This feature grew from delegates' experiences in the 1930s when excessively volatile exchange rates and the reactive protectionist exchange controls that followed proved destructive to trade and prolonged the deflationary effects of the Great Depression. Capital mobility faced de facto limits under the system as governments instituted restrictions on capital flows and aligned their monetary policy to support their pegs.[10]: 448 [26]: 38 [27]: 91 [28]: 30

An important component of the Bretton Woods agreements was the creation of two new international financial institutions, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD). Collectively referred to as the Bretton Woods institutions, they became operational in 1947 and 1946 respectively. The IMF was established to support the monetary system by facilitating cooperation on international monetary issues, providing advisory and technical assistance to members, and offering emergency lending to nations experiencing repeated difficulties restoring the balance of payments equilibrium. Members would contribute funds to a pool according to their share of gross world product, from which emergency loans could be issued.[24]: 21 [29]: 9–10 [30]: 20–22

Member states were authorized and encouraged to employ capital controls as necessary to manage payments imbalances and meet pegging targets, but prohibited from relying on IMF financing to cover particularly short-term capital hemorrhages.[26]: 38 While the IMF was instituted to guide members and provide a short-term financing window for recurrent balance of payments deficits, the IBRD was established to serve as a type of financial intermediary for channeling global capital toward long-term investment opportunities and postwar reconstruction projects.[31]: 22 The creation of these organizations was a crucial milestone in the evolution of the international financial architecture, and some economists consider it the most significant achievement of multilateral cooperation following World War II.[26]: 39 [32]: 1–3 Since the establishment of the International Development Association (IDA) in 1960, the IBRD and IDA are together known as the World Bank. While the IBRD lends to middle-income developing countries, the IDA extends the Bank's lending program by offering concessional loans and grants to the world's poorest nations.[33]

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade: 1947

In 1947, 23 countries concluded the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) at a UN conference in Geneva. Delegates intended the agreement to suffice while member states would negotiate creation of a UN body to be known as the International Trade Organization (ITO). As the ITO never became ratified, GATT became the de facto framework for later multilateral trade negotiations. Members emphasized trade reprocity as an approach to lowering barriers in pursuit of mutual gains.[18]: 46 The agreement's structure enabled its signatories to codify and enforce regulations for trading of goods and services.[34]: 11 GATT was centered on two precepts: trade relations needed to be equitable and nondiscriminatory, and subsidizing non-agricultural exports needed to be prohibited. As such, the agreement's most favored nation clause prohibited members from offering preferential tariff rates to any nation that it would not otherwise offer to fellow GATT members. In the event of any discovery of non-agricultural subsidies, members were authorized to offset such policies by enacting countervailing tariffs.[15]: 460 The agreement provided governments with a transparent structure for managing trade relations and avoiding protectionist pressures.[19]: 108 However, GATT's principles did not extend to financial activity, consistent with the era's rigid discouragement of capital movements.[35]: 70–71 The agreement's initial round achieved only limited success in reducing tariffs. While the U.S. reduced its tariffs by one third, other signatories offered much smaller trade concessions.[27]: 99

Flexible exchange rate regimes: 1973–present

Although the exchange rate stability sustained by the Bretton Woods system facilitated expanding international trade, this early success masked its underlying design flaw, wherein there existed no mechanism for increasing the supply of international reserves to support continued growth in trade.[24]: 22 The system began experiencing insurmountable market pressures and deteriorating cohesion among its key participants in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Central banks needed more U.S. dollars to hold as reserves, but were unable to expand their money supplies if doing so meant exceeding their dollar reserves and threatening their exchange rate pegs. To accommodate these needs, the Bretton Woods system depended on the United States to run dollar deficits. As a consequence, the dollar's value began exceeding its gold backing. During the early 1960s, investors could sell gold for a greater dollar exchange rate in London than in the United States, signaling to market participants that the dollar was overvalued. Belgian-American economist Robert Triffin defined this problem now known as the Triffin dilemma, in which a country's national economic interests conflict with its international objectives as the custodian of the world's reserve currency.[21]: 34–35

France voiced concerns over the artificially low price of gold in 1968 and called for returns to the former gold standard. Meanwhile, excess dollars flowed into international markets as the United States expanded its money supply to accommodate the costs of its military campaign in the Vietnam War. Its gold reserves were assaulted by speculative investors following its first current account deficit since the 19th century. In August 1971, President Richard Nixon suspended the exchange of U.S. dollars for gold as part of the Nixon Shock. The closure of the gold window effectively shifted the adjustment burdens of a devalued dollar to other nations. Speculative traders chased other currencies and began selling dollars in anticipation of these currencies being revalued against the dollar. These influxes of capital presented difficulties to foreign central banks, which then faced choosing among inflationary money supplies, largely ineffective capital controls, or floating exchange rates.[21]: 34–35 [36]: 14–15 Following these woes surrounding the U.S. dollar, the dollar price of gold was raised to US$38 per ounce and the Bretton Woods system was modified to allow fluctuations within an augmented band of 2.25% as part of the Smithsonian Agreement signed by the G-10 members in December 1971. The agreement delayed the system's demise for a further two years.[23]: 6–7 The system's erosion was expedited not only by the dollar devaluations that occurred, but also by the oil crises of the 1970s which emphasized the importance of international financial markets in petrodollar recycling and balance of payments financing. Once the world's reserve currency began to float, other nations began adopting floating exchange rate regimes.[16]: 5–7

Post-Bretton Woods financial order: 1976

.jpg.webp)

As part of the first amendment to its articles of agreement in 1969, the IMF developed a new reserve instrument called special drawing rights (SDRs), which could be held by central banks and exchanged among themselves and the Fund as an alternative to gold. SDRs entered service in 1970 originally as units of a market basket of sixteen major vehicle currencies of countries whose share of total world exports exceeded 1%. The basket's composition changed over time and presently consists of the U.S. dollar, euro, Japanese yen, Chinese yuan, and British pound. Beyond holding them as reserves, nations can denominate transactions among themselves and the Fund in SDRs, although the instrument is not a vehicle for trade. In international transactions, the currency basket's portfolio characteristic affords greater stability against the uncertainties inherent with free floating exchange rates.[20]: 34–35 [26]: 50–51 [27]: 117 [29]: 10 Special drawing rights were originally equivalent to a specified amount of gold, but were not directly redeemable for gold and instead served as a surrogate in obtaining other currencies that could be exchanged for gold. The Fund initially issued 9.5 billion XDR from 1970 to 1972.[31]: 182–183

IMF members signed the Jamaica Agreement in January 1976, which ratified the end of the Bretton Woods system and reoriented the Fund's role in supporting the international monetary system. The agreement officially embraced the flexible exchange rate regimes that emerged after the failure of the Smithsonian Agreement measures. In tandem with floating exchange rates, the agreement endorsed central bank interventions aimed at clearing excessive volatility. The agreement retroactively formalized the abandonment of gold as a reserve instrument and the Fund subsequently demonetized its gold reserves, returning gold to members or selling it to provide poorer nations with relief funding. Developing countries and countries not endowed with oil export resources enjoyed greater access to IMF lending programs as a result. The Fund continued assisting nations experiencing balance of payments deficits and currency crises, but began imposing conditionality on its funding that required countries to adopt policies aimed at reducing deficits through spending cuts and tax increases, reducing protective trade barriers, and contractionary monetary policy.[20]: 36 [30]: 47–48 [37]: 12–13

The second amendment to the articles of agreement was signed in 1978. It legally formalized the free-floating acceptance and gold demonetization achieved by the Jamaica Agreement, and required members to support stable exchange rates through macroeconomic policy. The post-Bretton Woods system was decentralized in that member states retained autonomy in selecting an exchange rate regime. The amendment also expanded the institution's capacity for oversight and charged members with supporting monetary sustainability by cooperating with the Fund on regime implementation.[26]: 62–63 [27]: 138 This role is called IMF surveillance and is recognized as a pivotal point in the evolution of the Fund's mandate, which was extended beyond balance of payments issues to broader concern with internal and external stresses on countries' overall economic policies.[27]: 148 [32]: 10–11

Under the dominance of flexible exchange rate regimes, the foreign exchange markets became significantly more volatile. In 1980, newly elected U.S. President Ronald Reagan's administration brought about increasing balance of payments deficits and budget deficits. To finance these deficits, the United States offered artificially high real interest rates to attract large inflows of foreign capital. As foreign investors' demand for U.S. dollars grew, the dollar's value appreciated substantially until reaching its peak in February 1985. The U.S. trade deficit grew to $160 billion in 1985 ($341 billion in 2012 dollars[11]) as a result of the dollar's strong appreciation. The G5 met in September 1985 at the Plaza Hotel in New York City and agreed that the dollar should depreciate against the major currencies to resolve the United States' trade deficit and pledged to support this goal with concerted foreign exchange market interventions, in what became known as the Plaza Accord. The U.S. dollar continued to depreciate, but industrialized nations became increasingly concerned that it would decline too heavily and that exchange rate volatility would increase. To address these concerns, the G7 (now G8) held a summit in Paris in 1987, where they agreed to pursue improved exchange rate stability and better coordinate their macroeconomic policies, in what became known as the Louvre Accord. This accord became the provenance of the managed float regime by which central banks jointly intervene to resolve under- and overvaluations in the foreign exchange market to stabilize otherwise freely floating currencies. Exchange rates stabilized following the embrace of managed floating during the 1990s, with a strong U.S. economic performance from 1997 to 2000 during the Dot-com bubble. After the 2000 stock market correction of the Dot-com bubble the country's trade deficit grew, the September 11 attacks increased political uncertainties, and the dollar began to depreciate in 2001.[16]: 175 [20]: 36–37 [21]: 37 [27]: 147 [38]: 16–17

European Monetary System: 1979

Following the Smithsonian Agreement, member states of the European Economic Community adopted a narrower currency band of 1.125% for exchange rates among their own currencies, creating a smaller scale fixed exchange rate system known as the snake in the tunnel. The snake proved unsustainable as it did not compel EEC countries to coordinate macroeconomic policies. In 1979, the European Monetary System (EMS) phased out the currency snake. The EMS featured two key components: the European Currency Unit (ECU), an artificial weighted average market basket of European Union members' currencies, and the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), a procedure for managing exchange rate fluctuations in keeping with a calculated parity grid of currencies' par values.[13]: 130 [20]: 42–44 [39]: 185

The parity grid was derived from parities each participating country established for its currency with all other currencies in the system, denominated in terms of ECUs. The weights within the ECU changed in response to variances in the values of each currency in its basket. Under the ERM, if an exchange rate reached its upper or lower limit (within a 2.25% band), both nations in that currency pair were obligated to intervene collectively in the foreign exchange market and buy or sell the under- or overvalued currency as necessary to return the exchange rate to its par value according to the parity matrix. The requirement of cooperative market intervention marked a key difference from the Bretton Woods system. Similarly to Bretton Woods however, EMS members could impose capital controls and other monetary policy shifts on countries responsible for exchange rates approaching their bounds, as identified by a divergence indicator which measured deviations from the ECU's value.[15]: 496–497 [24]: 29–30 The central exchange rates of the parity grid could be adjusted in exceptional circumstances, and were modified every eight months on average during the systems' initial four years of operation.[27]: 160 During its twenty-year lifespan, these central rates were adjusted over 50 times.[23]: 7

Birth of the World Trade Organization: 1994

The Uruguay Round of GATT multilateral trade negotiations took place from 1986 to 1994, with 123 nations becoming party to agreements achieved throughout the negotiations. Among the achievements were trade liberalization in agricultural goods and textiles, the General Agreement on Trade in Services, and agreements on intellectual property rights issues. The key manifestation of this round was the Marrakech Agreement signed in April 1994, which established the World Trade Organization (WTO). The WTO is a chartered multilateral trade organization, charged with continuing the GATT mandate to promote trade, govern trade relations, and prevent damaging trade practices or policies. It became operational in January 1995. Compared with its GATT secretariat predecessor, the WTO features an improved mechanism for settling trade disputes since the organization is membership-based and not dependent on consensus as in traditional trade negotiations. This function was designed to address prior weaknesses, whereby parties in dispute would invoke delays, obstruct negotiations, or fall back on weak enforcement.[10]: 181 [15]: 459–460 [18]: 47 In 1997, WTO members reached an agreement which committed to softer restrictions on commercial financial services, including banking services, securities trading, and insurance services. These commitments entered into force in March 1999, consisting of 70 governments accounting for approximately 95% of worldwide financial services.[41]

Financial integration and systemic crises: 1980–present

Financial integration among industrialized nations grew substantially during the 1980s and 1990s, as did liberalization of their capital accounts.[26]: 15 Integration among financial markets and banks rendered benefits such as greater productivity and the broad sharing of risk in the macroeconomy. The resulting interdependence also carried a substantive cost in terms of shared vulnerabilities and increased exposure to systemic risks.[43]: 440–441 Accompanying financial integration in recent decades was a succession of deregulation, in which countries increasingly abandoned regulations over the behavior of financial intermediaries and simplified requirements of disclosure to the public and to regulatory authorities.[16]: 36–37 As economies became more open, nations became increasingly exposed to external shocks. Economists have argued greater worldwide financial integration has resulted in more volatile capital flows, thereby increasing the potential for financial market turbulence. Given greater integration among nations, a systemic crisis in one can easily infect others.[34]: 136–137

The 1980s and 1990s saw a wave of currency crises and sovereign defaults, including the 1987 Black Monday stock market crashes, 1992 European Monetary System crisis, 1994 Mexican peso crisis, 1997 Asian currency crisis, 1998 Russian financial crisis, and the 1998–2002 Argentine peso crisis.[2]: 254 [15]: 498 [20]: 50–58 [44]: 6–7 [45]: 26–28 These crises differed in terms of their breadth, causes, and aggravations, among which were capital flights brought about by speculative attacks on fixed exchange rate currencies perceived to be mispriced given a nation's fiscal policy,[16]: 83 self-fulfilling speculative attacks by investors expecting other investors to follow suit given doubts about a nation's currency peg,[44]: 7 lack of access to developed and functioning domestic capital markets in emerging market countries,[32]: 87 and current account reversals during conditions of limited capital mobility and dysfunctional banking systems.[35]: 99

Following research of systemic crises that plagued developing countries throughout the 1990s, economists have reached a consensus that liberalization of capital flows carries important prerequisites if these countries are to observe the benefits offered by financial globalization. Such conditions include stable macroeconomic policies, healthy fiscal policy, robust bank regulations, and strong legal protection of property rights. Economists largely favor adherence to an organized sequence of encouraging foreign direct investment, liberalizing domestic equity capital, and embracing capital outflows and short-term capital mobility only once the country has achieved functioning domestic capital markets and established a sound regulatory framework.[16]: 25 [26]: 113 An emerging market economy must develop a credible currency in the eyes of both domestic and international investors to realize benefits of globalization such as greater liquidity, greater savings at higher interest rates, and accelerated economic growth. If a country embraces unrestrained access to foreign capital markets without maintaining a credible currency, it becomes vulnerable to speculative capital flights and sudden stops, which carry serious economic and social costs.[36]: xii

Countries sought to improve the sustainability and transparency of the global financial system in response to crises in the 1980s and 1990s. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision was formed in 1974 by the G-10 members' central bank governors to facilitate cooperation on the supervision and regulation of banking practices. It is headquartered at the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland. The committee has held several rounds of deliberation known collectively as the Basel Accords. The first of these accords, known as Basel I, took place in 1988 and emphasized credit risk and the assessment of different asset classes. Basel I was motivated by concerns over whether large multinational banks were appropriately regulated, stemming from observations during the 1980s Latin American debt crisis. Following Basel I, the committee published recommendations on new capital requirements for banks, which the G-10 nations implemented four years later. In 1999, the G-10 established the Financial Stability Forum (reconstituted by the G-20 in 2009 as the Financial Stability Board) to facilitate cooperation among regulatory agencies and promote stability in the global financial system. The Forum was charged with developing and codifying twelve international standards and implementation thereof.[26]: 222–223 [32]: 12

The Basel II accord was set in 2004 and again emphasized capital requirements as a safeguard against systemic risk as well as the need for global consistency in banking regulations so as not to competitively disadvantage banks operating internationally. It was motivated by what were seen as inadequacies of the first accord such as insufficient public disclosure of banks' risk profiles and oversight by regulatory bodies. Members were slow to implement it, with major efforts by the European Union and United States taking place as late as 2007 and 2008.[16]: 153 [17]: 486–488 [26]: 160–162 In 2010, the Basel Committee revised the capital requirements in a set of enhancements to Basel II known as Basel III, which centered on a leverage ratio requirement aimed at restricting excessive leveraging by banks. In addition to strengthening the ratio, Basel III modified the formulas used to weight risk and compute the capital thresholds necessary to mitigate the risks of bank holdings, concluding the capital threshold should be set at 7% of the value of a bank's risk-weighted assets.[20]: 274 [46]

Birth of the European Economic and Monetary Union 1992

In February 1992, European Union countries signed the Maastricht Treaty which outlined a three-stage plan to accelerate progress toward an Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). The first stage centered on liberalizing capital mobility and aligning macroeconomic policies between countries. The second stage established the European Monetary Institute which was ultimately dissolved in tandem with the establishment in 1998 of the European Central Bank (ECB) and European System of Central Banks. Key to the Maastricht Treaty was the outlining of convergence criteria that EU members would need to satisfy before being permitted to proceed. The third and final stage introduced a common currency for circulation known as the Euro, adopted by eleven of then-fifteen members of the European Union in January 1999. In doing so, they disaggregated their sovereignty in matters of monetary policy. These countries continued to circulate their national legal tenders, exchangeable for euros at fixed rates, until 2002 when the ECB began issuing official Euro coins and notes. As of 2011, the EMU comprises 17 nations which have issued the Euro, and 11 non-Euro states.[17]: 473–474 [20]: 45–4 [23]: 7 [39]: 185–186

Global financial crisis

Following the market turbulence of the 1990s financial crises and September 11 attacks on the U.S. in 2001, financial integration intensified among developed nations and emerging markets, with substantial growth in capital flows among banks and in the trading of financial derivatives and structured finance products. Worldwide international capital flows grew from $3 trillion to $11 trillion U.S. dollars from 2002 to 2007, primarily in the form of short-term money market instruments. The United States experienced growth in the size and complexity of firms engaged in a broad range of financial services across borders in the wake of the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act of 1999 which repealed the Glass–Steagall Act of 1933, ending limitations on commercial banks' investment banking activity. Industrialized nations began relying more on foreign capital to finance domestic investment opportunities, resulting in unprecedented capital flows to advanced economies from developing countries, as reflected by global imbalances which grew to 6% of gross world product in 2007 from 3% in 2001.[20]: 19 [26]: 129–130

The global financial crisis precipitated in 2007 and 2008 shared some of the key features exhibited by the wave of international financial crises in the 1990s, including accelerated capital influxes, weak regulatory frameworks, relaxed monetary policies, herd behavior during investment bubbles, collapsing asset prices, and massive deleveraging. The systemic problems originated in the United States and other advanced nations.[26]: 133–134 Similarly to the 1997 Asian crisis, the global crisis entailed broad lending by banks undertaking unproductive real estate investments as well as poor standards of corporate governance within financial intermediaries. Particularly in the United States, the crisis was characterized by growing securitization of non-performing assets, large fiscal deficits, and excessive financing in the housing sector.[20]: 18–20 [35]: 21–22 While the real estate bubble in the U.S. triggered the financial crisis, the bubble was financed by foreign capital flowing from many countries. As its contagious effects began infecting other nations, the crisis became a precursor for the global economic downturn now referred to as the Great Recession. In the wake of the crisis, total volume of world trade in goods and services fell 10% from 2008 to 2009 and did not recover until 2011, with an increased concentration in emerging market countries. The global financial crisis demonstrated the negative effects of worldwide financial integration, sparking discourse on how and whether some countries should decouple themselves from the system altogether.[47][48]: 3

Eurozone crisis

In 2009, a newly elected government in Greece revealed the falsification of its national budget data, and that its fiscal deficit for the year was 12.7% of GDP as opposed to the 3.7% espoused by the previous administration. This news alerted markets to the fact that Greece's deficit exceeded the eurozone's maximum of 3% outlined in the Economic and Monetary Union's Stability and Growth Pact. Investors concerned about a possible sovereign default rapidly sold Greek bonds. Given Greece's prior decision to embrace the euro as its currency, it no longer held monetary policy autonomy and could not intervene to depreciate a national currency to absorb the shock and boost competitiveness, as was the traditional solution to sudden capital flight. The crisis proved contagious when it spread to Portugal, Italy, and Spain (together with Greece these are collectively referred to as the PIGS). Ratings agencies downgraded these countries' debt instruments in 2010 which further increased the costliness of refinancing or repaying their national debts. The crisis continued to spread and soon grew into a European sovereign debt crisis which threatened economic recovery in the wake of the Great Recession. In tandem with the IMF, the European Union members assembled a €750 billion bailout for Greece and other afflicted nations. Additionally, the ECB pledged to purchase bonds from troubled eurozone nations in an effort to mitigate the risk of a banking system panic. The crisis is recognized by economists as highlighting the depth of financial integration in Europe, contrasted with the lack of fiscal integration and political unification necessary to prevent or decisively respond to crises. During the initial waves of the crisis, the public speculated that the turmoil could result in a disintegration of the eurozone and an abandonment of the euro. German Federal Minister of Finance Wolfgang Schäuble called for the expulsion of offending countries from the eurozone. Now commonly referred to as the Eurozone crisis, it has been ongoing since 2009 and most recently began encompassing the 2012–2013 Cypriot financial crisis.[20]: 12–14 [49]: 579–581

Implications of globalized capital

Balance of payments

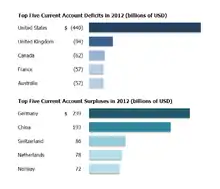

The balance of payments accounts summarize payments made to or received from foreign countries. Receipts are considered credit transactions while payments are considered debit transactions. The balance of payments is a function of three components: transactions involving export or import of goods and services form the current account, transactions involving purchase or sale of financial assets form the financial account, and transactions involving unconventional transfers of wealth form the capital account.[49]: 306–307 The current account summarizes three variables: the trade balance, net factor income from abroad, and net unilateral transfers. The financial account summarizes the value of exports versus imports of assets, and the capital account summarizes the value of asset transfers received net of transfers given. The capital account also includes the official reserve account, which summarizes central banks' purchases and sales of domestic currency, foreign exchange, gold, and SDRs for purposes of maintaining or utilizing bank reserves.[20]: 66–71 [50]: 169–172 [51]: 32–35

Because the balance of payments sums to zero, a current account surplus indicates a deficit in the asset accounts and vice versa. A current account surplus or deficit indicates the extent to which a country is relying on foreign capital to finance its consumption and investments, and whether it is living beyond its means. For example, assuming a capital account balance of zero (thus no asset transfers available for financing), a current account deficit of £1 billion implies a financial account surplus (or net asset exports) of £1 billion. A net exporter of financial assets is known as a borrower, exchanging future payments for current consumption. Further, a net export of financial assets indicates growth in a country's debt. From this perspective, the balance of payments links a nation's income to its spending by indicating the degree to which current account imbalances are financed with domestic or foreign financial capital, which illuminates how a nation's wealth is shaped over time.[20]: 73 [49]: 308–313 [50]: 203 A healthy balance of payments position is important for economic growth. If countries experiencing a growth in demand have trouble sustaining a healthy balance of payments, demand can slow, leading to: unused or excess supply, discouraged foreign investment, and less attractive exports which can further reinforce a negative cycle that intensifies payments imbalances.[52]: 21–22

A country's external wealth is measured by the value of its foreign assets net of its foreign liabilities. A current account surplus (and corresponding financial account deficit) indicates an increase in external wealth while a deficit indicates a decrease. Aside from current account indications of whether a country is a net buyer or net seller of assets, shifts in a nation's external wealth are influenced by capital gains and capital losses on foreign investments. Having positive external wealth means a country is a net lender (or creditor) in the world economy, while negative external wealth indicates a net borrower (or debtor).[50]: 13, 210

Unique financial risks

Nations and international businesses face an array of financial risks unique to foreign investment activity. Political risk is the potential for losses from a foreign country's political instability or otherwise unfavorable developments, which manifests in different forms. Transfer risk emphasizes uncertainties surrounding a country's capital controls and balance of payments. Operational risk characterizes concerns over a country's regulatory policies and their impact on normal business operations. Control risk is born from uncertainties surrounding property and decision rights in the local operation of foreign direct investments.[20]: 422 Credit risk implies lenders may face an absent or unfavorable regulatory framework that affords little or no legal protection of foreign investments. For example, foreign governments may commit to a sovereign default or otherwise repudiate their debt obligations to international investors without any legal consequence or recourse. Governments may decide to expropriate or nationalize foreign-held assets or enact contrived policy changes following an investor's decision to acquire assets in the host country.[50]: 14–17 Country risk encompasses both political risk and credit risk, and represents the potential for unanticipated developments in a host country to threaten its capacity for debt repayment and repatriation of gains from interest and dividends.[20]: 425, 526 [53]: 216

Participants

Economic actors

Each of the core economic functions, consumption, production, and investment, have become highly globalized in recent decades. While consumers increasingly import foreign goods or purchase domestic goods produced with foreign inputs, businesses continue to expand production internationally to meet an increasingly globalized consumption in the world economy. International financial integration among nations has afforded investors the opportunity to diversify their asset portfolios by investing abroad.[20]: 4–5 Consumers, multinational corporations, individual and institutional investors, and financial intermediaries (such as banks) are the key economic actors within the global financial system. Central banks (such as the European Central Bank or the U.S. Federal Reserve System) undertake open market operations in their efforts to realize monetary policy goals.[22]: 13–15 [24]: 11–13, 76 International financial institutions such as the Bretton Woods institutions, multilateral development banks and other development finance institutions provide emergency financing to countries in crisis, provide risk mitigation tools to prospective foreign investors, and assemble capital for development finance and poverty reduction initiatives.[26]: 243 Trade organizations such as the World Trade Organization, Institute of International Finance, and the World Federation of Exchanges attempt to ease trade, facilitate trade disputes and address economic affairs, promote standards, and sponsor research and statistics publications.[54][55][56]

Regulatory bodies

Explicit goals of financial regulation include countries' pursuits of financial stability and the safeguarding of unsophisticated market players from fraudulent activity, while implicit goals include offering viable and competitive financial environments to world investors.[36]: 57 A single nation with functioning governance, financial regulations, deposit insurance, emergency financing through discount windows, standard accounting practices, and established legal and disclosure procedures, can itself develop and grow a healthy domestic financial system. In a global context however, no central political authority exists which can extend these arrangements globally. Rather, governments have cooperated to establish a host of institutions and practices that have evolved over time and are referred to collectively as the international financial architecture.[16]: xviii [26]: 2 Within this architecture, regulatory authorities such as national governments and intergovernmental organizations have the capacity to influence international financial markets. National governments may employ their finance ministries, treasuries, and regulatory agencies to impose tariffs and foreign capital controls or may use their central banks to execute a desired intervention in the open markets.[50]: 17–21

Some degree of self-regulation occurs whereby banks and other financial institutions attempt to operate within guidelines set and published by multilateral organizations such as the International Monetary Fund or the Bank for International Settlements (particularly the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and the Committee on the Global Financial System[57]).[29]: 33–34 Further examples of international regulatory bodies are: the Financial Stability Board (FSB) established to coordinate information and activities among developed countries; the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) which coordinates the regulation of financial securities; the International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) which promotes consistent insurance industry supervision; the Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering which facilitates collaboration in battling money laundering and terrorism financing; and the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) which publishes accounting and auditing standards. Public and private arrangements exist to assist and guide countries struggling with sovereign debt payments, such as the Paris Club and London Club.[26]: 22 [32]: 10–11 National securities commissions and independent financial regulators maintain oversight of their industries' foreign exchange market activities.[21]: 61–64 Two examples of supranational financial regulators in Europe are the European Banking Authority (EBA) which identifies systemic risks and institutional weaknesses and may overrule national regulators, and the European Shadow Financial Regulatory Committee (ESFRC) which reviews financial regulatory issues and publishes policy recommendations.[58][59]

Research organizations and other fora

Research and academic institutions, professional associations, and think-tanks aim to observe, model, understand, and publish recommendations to improve the transparency and effectiveness of the global financial system. For example, the independent non-partisan World Economic Forum facilitates the Global Agenda Council on the Global Financial System and Global Agenda Council on the International Monetary System, which report on systemic risks and assemble policy recommendations.[60][61] The Global Financial Markets Association facilitates discussion of global financial issues among members of various professional associations around the world.[62] The Group of Thirty (G30) formed in 1978 as a private, international group of consultants, researchers, and representatives committed to advancing understanding of international economics and global finance.[63]

Future of the global financial system

The IMF has reported that the global financial system is on a path to improved financial stability, but faces a host of transitional challenges borne out by regional vulnerabilities and policy regimes. One challenge is managing the United States' disengagement from its accommodative monetary policy. Doing so in an elegant, orderly manner could be difficult as markets adjust to reflect investors' expectations of a new monetary regime with higher interest rates. Interest rates could rise too sharply if exacerbated by a structural decline in market liquidity from higher interest rates and greater volatility, or by structural deleveraging in short-term securities and in the shadow banking system (particularly the mortgage market and real estate investment trusts). Other central banks are contemplating ways to exit unconventional monetary policies employed in recent years. Some nations however, such as Japan, are attempting stimulus programs at larger scales to combat deflationary pressures. The Eurozone's nations implemented myriad national reforms aimed at strengthening the monetary union and alleviating stress on banks and governments. Yet some European nations such as Portugal, Italy, and Spain continue to struggle with heavily leveraged corporate sectors and fragmented financial markets in which investors face pricing inefficiency and difficulty identifying quality assets. Banks operating in such environments may need stronger provisions in place to withstand corresponding market adjustments and absorb potential losses. Emerging market economies face challenges to greater stability as bond markets indicate heightened sensitivity to monetary easing from external investors flooding into domestic markets, rendering exposure to potential capital flights brought on by heavy corporate leveraging in expansionary credit environments. Policymakers in these economies are tasked with transitioning to more sustainable and balanced financial sectors while still fostering market growth so as not to provoke investor withdrawal.[64]: xi–xiii

The global financial crisis and Great Recession prompted renewed discourse on the architecture of the global financial system. These events called to attention financial integration, inadequacies of global governance, and the emergent systemic risks of financial globalization.[65]: 2–9 Since the establishment in 1945 of a formal international monetary system with the IMF empowered as its guardian, the world has undergone extensive changes politically and economically. This has fundamentally altered the paradigm in which international financial institutions operate, increasing the complexities of the IMF and World Bank's mandates.[32]: 1–2 The lack of adherence to a formal monetary system has created a void of global constraints on national macroeconomic policies and a deficit of rule-based governance of financial activities.[66]: 4 French economist and Executive Director of the World Economic Forum's Reinventing Bretton Woods Committee, Marc Uzan, has pointed out that some radical proposals such as a "global central bank or a world financial authority" have been deemed impractical, leading to further consideration of medium-term efforts to improve transparency and disclosure, strengthen emerging market financial climates, bolster prudential regulatory environments in advanced nations, and better moderate capital account liberalization and exchange rate regime selection in emerging markets. He has also drawn attention to calls for increased participation from the private sector in the management of financial crises and the augmenting of multilateral institutions' resources.[32]: 1–2

The Council on Foreign Relations' assessment of global finance notes that excessive institutions with overlapping directives and limited scopes of authority, coupled with difficulty aligning national interests with international reforms, are the two key weaknesses inhibiting global financial reform. Nations do not presently enjoy a comprehensive structure for macroeconomic policy coordination, and global savings imbalances have abounded before and after the global financial crisis to the extent that the United States' status as the steward of the world's reserve currency was called into question. Post-crisis efforts to pursue macroeconomic policies aimed at stabilizing foreign exchange markets have yet to be institutionalized. The lack of international consensus on how best to monitor and govern banking and investment activity threatens the world's ability to prevent future global financial crises. The slow and often delayed implementation of banking regulations that meet Basel III criteria means most of the standards will not take effect until 2019, rendering continued exposure of global finance to unregulated systemic risks. Despite Basel III and other efforts by the G20 to bolster the Financial Stability Board's capacity to facilitate cooperation and stabilizing regulatory changes, regulation exists predominantly at the national and regional levels.[67]

Reform efforts

Former World Bank Chief Economist and former Chairman of the U.S. Council of Economic Advisers Joseph E. Stiglitz referred in the late 1990s to a growing consensus that something is wrong with a system having the capacity to impose high costs on a great number of people who are hardly even participants in international financial markets, neither speculating on international investments nor borrowing in foreign currencies. He argued that foreign crises have strong worldwide repercussions due in part to the phenomenon of moral hazard, particularly when many multinational firms deliberately invest in highly risky government bonds in anticipation of a national or international bailout. Although crises can be overcome by emergency financing, employing bailouts places a heavy burden on taxpayers living in the afflicted countries, and the high costs damage standards of living. Stiglitz has advocated finding means of stabilizing short-term international capital flows without adversely affecting long-term foreign direct investment which usually carries new knowledge spillover and technological advancements into economies.[68]

American economist and former Chairman of the Federal Reserve Paul Volcker has argued that the lack of global consensus on key issues threatens efforts to reform the global financial system. He has argued that quite possibly the most important issue is a unified approach to addressing failures of systemically important financial institutions, noting public taxpayers and government officials have grown disillusioned with deploying tax revenues to bail out creditors for the sake of stopping contagion and mitigating economic disaster. Volcker has expressed an array of potential coordinated measures: increased policy surveillance by the IMF and commitment from nations to adopt agreed-upon best practices, mandatory consultation from multilateral bodies leading to more direct policy recommendations, stricter controls on national qualification for emergency financing facilities (such as those offered by the IMF or by central banks), and improved incentive structures with financial penalties.[69]

Governor of the Bank of England and former Governor of the Bank of Canada Mark Carney has described two approaches to global financial reform: shielding financial institutions from cyclic economic effects by strengthening banks individually, and defending economic cycles from banks by improving systemic resiliency. Strengthening financial institutions necessitates stronger capital requirements and liquidity provisions, as well as better measurement and management of risks. The G-20 agreed to new standards presented by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision at its 2009 summit in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The standards included leverage ratio targets to supplement other capital adequacy requirements established by Basel II. Improving the resiliency of the global financial system requires protections that enable the system to withstand singular institutional and market failures. Carney has argued that policymakers have converged on the view that institutions must bear the burden of financial losses during future financial crises, and such occurrences should be well-defined and pre-planned. He suggested other national regulators follow Canada in establishing staged intervention procedures and require banks to commit to what he termed "living wills" which would detail plans for an orderly institutional failure.[70]

At its 2010 summit in Seoul, South Korea, the G-20 collectively endorsed a new collection of capital adequacy and liquidity standards for banks recommended by Basel III. Andreas Dombret of the Executive Board of Deutsche Bundesbank has noted a difficulty in identifying institutions that constitute systemic importance via their size, complexity, and degree of interconnectivity within the global financial system, and that efforts should be made to identify a group of 25 to 30 indisputable globally systemic institutions. He has suggested they be held to standards higher than those mandated by Basel III, and that despite the inevitability of institutional failures, such failures should not drag with them the financial systems in which they participate. Dombret has advocated for regulatory reform that extends beyond banking regulations and has argued in favor of greater transparency through increased public disclosure and increased regulation of the shadow banking system.[71]

President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and Vice Chairman of the Federal Open Market Committee William C. Dudley has argued that a global financial system regulated on a largely national basis is untenable for supporting a world economy with global financial firms. In 2011, he advocated five pathways to improving the safety and security of the global financial system: a special capital requirement for financial institutions deemed systemically important; a level playing field which discourages exploitation of disparate regulatory environments and beggar thy neighbour policies that serve "national constituencies at the expense of global financial stability"; superior cooperation among regional and national regulatory regimes with broader protocols for sharing information such as records for the trade of over-the-counter financial derivatives; improved delineation of "the responsibilities of the home versus the host country" when banks encounter trouble; and well-defined procedures for managing emergency liquidity solutions across borders including which parties are responsible for the risk, terms, and funding of such measures.[72]

See also

- Outline of finance

References

- James, Paul W.; Patomäki, Heikki (2007). Globalization and Economy, Vol. 2: Globalizing Finance and the New Economy. London, UK: Sage Publications. ISBN 978-1-4129-1952-4.

- Cassis, Youssef (2006). Capitals of Capital: A History of International Financial Centres, 1780–2005. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-33522-8.

- Flandreau, Marc; Holtfrerich, Carl-Ludwig; James, Harold (2003). International Financial History in the Twentieth Century: System and Anarchy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-07011-2.

- Eichengreen, Barry; Esteves, Rui Pedro (2021), Fukao, Kyoji; Broadberry, Stephen (eds.), "International Finance", The Cambridge Economic History of the Modern World: Volume 2: 1870 to the Present, Cambridge University Press, vol. 2, pp. 501–525, ISBN 978-1-107-15948-8

- "Goal 10 targets". UNDP. Archived from the original on 2020-11-27. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- London and Paris as International Financial Centres in the Twentieth Century. Oxford: OUP Oxford. 2005. ISBN 9780191533471.

- Cameron, Rondo; Bovykin, V.I., eds. (1991). International Banking: 1870–1914. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506271-7.

- Benedictus, Leo (2006-11-16). "A brief history of the passport". The Guardian. Retrieved 2013-07-04.

- "International Civil Aviation Organization: A trusted international authority". Passport Canada. Archived from the original on 2013-05-22. Retrieved 2013-07-04.

- Carbaugh, Robert J. (2005). International Economics, 10th Edition. Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western. ISBN 978-0-324-52724-7.

- "CPI Inflation Calculator". U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- "Inflation Calculator". Bank of England. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- Atkin, John (2005). The Foreign Exchange Market of London: Development Since 1900. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-32269-7.

- Kennedy, Simon (2013-05-09). "Fed in 2008 Showed Panic of 1907 Was Excessive: Cutting Research". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2013-07-09.

- Levi, Maurice D. (2005). International Finance, 4th Edition. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-30900-4.

- Saccomanni, Fabrizio (2008). Managing International Financial Instability: National Tamers versus Global Tigers. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-84542-142-7.

- Dunn, Robert M. Jr.; Mutti, John H. (2004). International Economics, 6th Edition. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-31154-0.

- Bagwell, Kyle; Staiger, Robert W. (2004). The Economics of the World Trading System. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-52434-6.

- Thompson, Henry (2006). International Economics: Global Markets and Competition, 2nd Edition. Toh Tuck Link, Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-256-346-0.

- Eun, Cheol S.; Resnick, Bruce G. (2011). International Financial Management, 6th Edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. ISBN 978-0-07-803465-7.

- Rosenstreich, Peter (2005). Forex Revolution: An Insider's Guide to the Real World of Foreign Exchange Trading. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Financial Times–Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-148690-4.

- Chen, James (2009). Essentials of Foreign Exchange Trading. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-39086-3.

- DeRosa, David F. (2011). Options on Foreign Exchange, 3rd Edition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-09821-9.

- Buckley, Adrian (2004). Multinational Finance. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Limited. ISBN 978-0-273-68209-7.

- Wang, Peijie (2005). The Economics of Foreign Exchange and Global Finance. Berlin, Germany: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-21237-9.

- Elson, Anthony (2011). Governing Global Finance: The Evolution and Reform of the International Financial Architecture. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-10378-8.

- Eichengreen, Barry (2008). Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System, 2nd Edition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13937-1.

- Bordo, Michael D. (2000). The Globalization of International Financial Markets: What Can History Teach Us? (PDF). International Financial Markets: The Challenge of Globalization. March 31, 2000. Texas A&M University, College Station, TX. pp. 1–67. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- Shamah, Shani (2003). A Foreign Exchange Primer. Chichester, West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-85162-3.

- Thirkell-White, Ben (2005). The IMF and the Politics of Financial Globalization: From the Asian Crisis to a New International Financial Architecture?. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-2078-2.

- Endres, Anthony M. (2005). Great Architects of International Finance. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-32412-0.

- Uzan, Marc, ed. (2005). The Future of the International Monetary System. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-84376-805-0.

- International Development Association. "What is IDA?". World Bank Group. Archived from the original on 2010-04-09. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- Bryant, Ralph C. (2004). Crisis Prevention and Prosperity Management for the World Economy. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-8157-0867-4.

- Makin, Anthony J. (2009). Global Imbalances, Exchange Rates and Stabilization Policy. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-57685-8.

- Yadav, Vikash (2008). Risk in International Finance. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-77519-9.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2003). Globalization and Its Discontents. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-32439-6.

- Reszat, Beate (2003). The Japanese Foreign Exchange Market. New Fetter Lane, London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-22254-6.

- Steiner, Bob (2002). Foreign Exchange and Money Markets: Theory, Practice and Risk Management. Woburn, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-5025-0.

- "Fourth Global Review of Aid for Trade: "Connecting to value chains"". World Trade Organization. 8–10 July 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- World Trade Organization (1999-02-15). "The WTO's financial services commitments will enter into force as scheduled" (Press release). WTO News. Retrieved 2013-08-24.

- Rogoff, Kenneth; Reinhart, Carmen (2009). This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14216-6.

- Wong, Alfred Y-T.; Fong, Tom Pak Wing (2011). "Analysing interconnectivity among countries". Emerging Markets Review. 12 (4): 432–442. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.667.5601. doi:10.1016/j.ememar.2011.06.004.

- Hansanti, Songporn; Islam, Sardar M. N.; Sheehan, Peter (2008). International Finance in Emerging Markets. Heidelberg, Germany: Physica-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7908-2555-8.

- Homaifar, Ghassem A. (2004). Managing Global Financial and Foreign Exchange Risk. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-28115-3.

- Hamilton, Jesse; Onaran, Yalman (2013-07-09). "U.S. Boosts Bank Capital Demands Above Global Standards". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2013-09-07.

- Arndt, Sven W.; Crowley, Patrick M.; Mayes, David G. (2009). "The implications of integration for globalization". North American Journal of Economics and Finance. 20 (2): 83–90. doi:10.1016/j.najef.2009.08.001.

- Lawrence, Robert Z.; Hanouz, Margareta Drzeniek; Doherty, Sean (2012). The Global Enabling Trade Report 2012: Reducing Supply Chain Barriers (PDF) (Report). World Economic Forum. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- Krugman, Paul R.; Obstfeld, Maurice; Melitz, Marc J. (2012). International Economics: Theory & Policy, 9th Edition. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-13-214665-4.

- Feenstra, Robert C.; Taylor, Alan M. (2008). International Macroeconomics. New York, NY: Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4292-0691-4.

- Madura, Jeff (2007). International Financial Management: Abridged 8th Edition. Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western. ISBN 978-0-324-36563-4.

- Thirlwall, A.P. (2004). "The balance of payments constraint as an explanation of international growth rate differences". In McCombie, J.S.L.; Thirlwall, A.P. (eds.). Essays on Balance of Payments Constrained Growth: Theory and Evidence. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-49536-0.

- Melvin, Michael; Norrbin, Stefan C. (2013). International Money and Finance, 8th Edition. Waltham, MA: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-385247-2.

- "What we do". World Trade Organization. Retrieved 2013-12-03.

- "About IIF". Institute of International Finance. Archived from the original on 2013-12-23. Retrieved 2013-11-29.