Goldsmith

A goldsmith is a metalworker who specializes in working with gold and other precious metals. Nowadays they mainly specialize in jewelry-making but historically, goldsmiths have also made silverware, platters, goblets, decorative and serviceable utensils, and ceremonial or religious items.

Goldsmiths must be skilled in forming metal through filing, soldering, sawing, forging, casting, and polishing. The trade has very often included jewelry-making skills, as well as the very similar skills of the silversmith. Traditionally, these skills had been passed along through apprenticeships; however, more recently jewelry arts schools, specializing in teaching goldsmithing and a multitude of skills falling under the jewelry arts umbrella, are available. Many universities and junior colleges also offer goldsmithing, silversmithing, and metal arts fabrication as a part of their fine arts curriculum.

Gold

Compared to other metals, gold is malleable, ductile, rare, and it is the only solid metallic element with a yellow color. It may easily be melted, fused, and cast without the problems of oxides and gas that are problematic with other metals such as bronzes, for example. It is fairly easy to "pressure weld", wherein, similarly to clay, two small pieces may be pounded together to make one larger piece. Gold is classified as a noble metal—because it does not react with most elements. It usually is found in its native form, lasting indefinitely without oxidization and tarnishing.

History

Gold has been worked by humans in all cultures where the metal is available, either indigenously or imported, and the history of these activities is extensive. Superbly made objects from the ancient cultures of Africa, Asia, Europe, India, North America, Mesoamerica, and South America grace museums and collections throughout the world. The Copper Age Varna culture (Bulgaria) from the 5th millennium BC is credited with inventing goldsmith (gold metallurgy).[1][2] The associated Varna Necropolis treasure contains the oldest golden jewellery in the world with an approximate age of over 6,000 years.[3][4]

Some pieces date back thousands of years and were made using many techniques that still are used by modern goldsmiths. Techniques developed by some of those goldsmiths achieved a skill level that was lost and remained beyond the skills of those who followed, even to modern times.[5] Researchers attempting to uncover the chemical techniques used by ancient artisans have remarked that their findings confirm that "the high level of competence reached by the artists and craftsmen of these ancient periods who produced objects of an artistic quality that could not be bettered in ancient times and has not yet been reached in modern ones."[6]

In medieval Europe goldsmiths were organized into guilds and usually were one of the most important and wealthiest of the guilds in a city. The guild kept records of members and the marks they used on their products. These records, when they survive, are very useful to historians. Goldsmiths often acted as bankers, since they dealt in gold and had sufficient security for the safe storage of valuable items, though they were usually restrained from lending at interest, which was regarded as usury. In the Middle Ages, goldsmithing normally included silversmithing as well, but the brass workers and workers in other base metals normally were members of a separate guild, since the trades were not allowed to overlap. Many jewelers also were goldsmiths.

The Sunar caste is one of the oldest communities in goldsmithing in India, whose superb gold artworks were displayed at The Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. In India, 'Daivadnya Brahmins',Vishwakarma (Viswabrahmins,Acharis)'Sunar' are the goldsmith castes.

The printmaking technique of engraving developed among goldsmiths in Germany around 1430, who had long used the technique on their metal pieces. The notable engravers of the fifteenth century were either goldsmiths, such as Master E. S., or the sons of goldsmiths, such as Martin Schongauer and Albrecht Dürer.

Contemporary goldsmithing

A goldsmith might have a wide array of skills and knowledge at their disposal. Gold, being the most malleable metal of all, offers unique opportunities for the worker. In today's world a wide variety of other metals, especially platinum alloys, also may be used frequently. 24 karat is pure gold and historically, was known as fine gold.[7]

Because it is so soft, however, 24 karat gold is rarely used. It is usually alloyed to make it stronger and to create different colors. Depending on the metals used to create the alloy, the color can change.

The goldsmith will use a variety of tools and machinery, including the rolling mill, the drawplate, and perhaps, swage blocks and other forming tools to make the metal into shapes needed to build the intended piece. Then parts are fabricated through a wide variety of processes and assembled by soldering. It is a testament to the history and evolution of the trade that those skills have reached an extremely high level of attainment and skill over time. A fine goldsmith can and will work to a tolerance approaching that of precision machinery, but largely using only his eyes and hand tools. Quite often the goldsmith's job involves the making of mountings for gemstones, in which case they often are referred to as jewelers.

'Jeweller', however, is a term mostly reserved for a person who deals in jewellery (buys and sells) and not to be confused with a goldsmith, silversmith, gemologist, diamond cutter, and diamond setters. A 'jobbing jeweller' is the term for a jeweller who undertakes a small basic amount of jewellery repair and alteration.

Notable goldsmiths

Historical

- Kalogjera family[8]

- Benvenuto Cellini

- House of Fabergé

- Lorenzo Ghiberti

- Johannes Gutenberg

- George Heriot

- Gaspard van der Heyden

- Paul de Lamerie

- Arnold Lulls

- Jean-Valentin Morel

- Paul Storr

- Adrien Vachette

Contemporary

- Lois Betteridge

- Jocelyn Burton

- Andrea Cagnetti – Akelo

- Cartier

- William Claude Harper

- Mary Lee Hu

- Linda MacNeil

- Mazlo

- John Paul Miller (1918–2013)

- Gary Noffke

- Christoph Steidl Porenta

Gallery

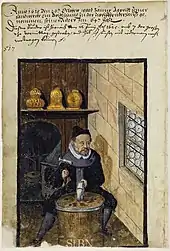

Renaissance goldsmith shop

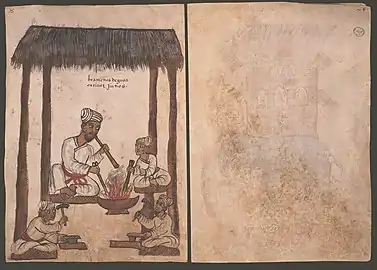

Renaissance goldsmith shop A Brahmin goldsmith from Goa, India, 16th century

A Brahmin goldsmith from Goa, India, 16th century Goldsmith's workshop in Museum of Arts and Popular Customs of Seville

Goldsmith's workshop in Museum of Arts and Popular Customs of Seville A Karo people (Indonesia) goldsmith in Sumatra (circa 1918)

A Karo people (Indonesia) goldsmith in Sumatra (circa 1918)

See also

- Bench jeweler

- Jewelers' Row

- Old master print, engraving, and niello – goldsmith's techniques or related trades in the Middle Ages

- Persian-Sassanide art patterns

- Household silver

- Sunar

- Toreutics

References

- Roberts, Benjamin W.; Thornton, Christopher P. (2009). "Development of metallurgy in Eurasia". Antiquity. Department of Prehistory and Europe, British Museum. 83 (322): 1015. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00099312. S2CID 163062746. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

In contrast, the earliest exploitation and working of gold occurs in the Balkans during the mid-fifth millennium BC, several centuries after the earliest known copper smelting. This is demonstrated most spectacularly in the various objects adorning the burials at Varna, Bulgaria (Renfrew 1986; Highamet al. 2007). In contrast, the earliest gold objects found in Southwest Asia date only to the beginning of the fourth millennium BC as at Nahal Qanah in Israel (Golden 2009), suggesting that gold exploitation may have been a Southeast European invention, albeit a short-lived one.

- de Laet, Sigfried J. (1996). History of Humanity: From the Third Millennium to the Seventh Century BC. UNESCO / Routledge. p. 99. ISBN 978-92-3-102811-3.

The first major gold-working centre was situated at the mouth of the Danube, on the shores of the Black Sea in Bulgaria

- Grande, Lance (2009). Gems and Gemstones: Timeless Natural Beauty of the Mineral World. University of Chicago Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-226-30511-0.

The oldest known gold jewelry in the world is from an archaeological site in Varna Necropolis, Bulgaria, and is over 6,000 years old (radiocarbon dated between 4,600 BC and 4,200 BC).

- Anthony, David W.; Chi, Jennifer, eds. (2010). The Lost World of Old Europe: The Danube Valley, 5000–3500 BC. Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. pp. 39, 201. ISBN 978-0-691-14388-0.

grave 43 at the Varna cemetery, the richest single grave from Old Europe, dated about 4600–4500 BC.

- American Chemical Society, Ancient technology for metal coatings 2,000 years ago can't be matched even today, ScienceDaily, ScienceDaily, July 24, 2013,

- Gabriel Maria Ingo, Giuseppe Guida, Emma Angelini, Gabriella Di Carlo, Alessio Mezzi, Giuseppina Padeletti, Ancient Mercury-Based Plating Methods: Combined Use of Surface Analytical Techniques for the Study of Manufacturing Process and Degradation Phenomena, Accounts of Chemical Research, 2013; 130705111206005 DOI: 10.1021/ar300232e

- McQuhae, William (17 December 2008). McQuhae's Practical Technical Instructor (3rd ed.). Lightning Source Incorporated. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-4437-8201-2.

- Vinicije B. Lupis, Zlatarska bilježnica obitelji Kalogjera iz Blata na otoku Korčuli (Goldsmith's Book of the Kalogjera Family from Blato on the Island of Korčula) in Peristil : zbornik radova za povijest umjetnosti, Vol. 52, No. 1, translated from Croatian, Institut društvenih znanosti "Ivo Pilar", Područni centar Dubrovnik, 2009.

External links

Media related to Goldsmiths at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Goldsmiths at Wikimedia Commons