Grand Rapids, Michigan

Grand Rapids is a city and county seat of Kent County in the U.S. state of Michigan.[4] At the 2020 census, the city had a population of 198,917[5] which ranks it as the second most-populated city in the state after Detroit. Grand Rapids is the central city of the Grand Rapids metropolitan area, which has a population of 1,087,592 and a combined statistical area population of 1,383,918.[2]

Grand Rapids | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Grand Rapids | |

Images from top to bottom, left to right: downtown cityscape, Meyer May House, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum, La Grande Vitesse, pedestrian bridge over the Grand River, Van Andel Arena, Van Andel Institute on the Medical Mile | |

|

Flag  Seal  Logo | |

| Nicknames: GR, River City, Beer City, Furniture City | |

| Motto(s): | |

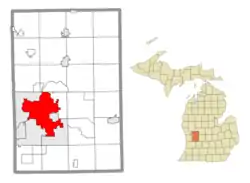

Location within Kent County | |

Grand Rapids Location within the state of Michigan  Grand Rapids Location within the United States | |

| Coordinates: 42°57′40″N 85°39′20″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Michigan |

| County | Kent |

| Founded | 1826 |

| Incorporation | 1850 |

| Government | |

| • Type | City commission |

| • Mayor | Rosalynn Bliss (D) |

| • Manager | Mark Washington |

| • Clerk | Joel Hondorp |

| Area | |

| • City | 45.63 sq mi (118.19 km2) |

| • Land | 44.78 sq mi (115.97 km2) |

| • Water | 0.86 sq mi (2.22 km2) 1.92% |

| Elevation | 640 ft (200 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 198,917 |

| • Rank | US: 115th MI: 2nd |

| • Density | 4,442.49/sq mi (1,715.26/km2) |

| • Urban (2010) | 569,935 (US: 70th) |

| • Metro | 1,077,370[2] (US: 52nd) |

| • CSA | 1,412,470[2] (US: 42nd) |

| Demonym | Grand Rapidian |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 49501–49508, 49510, 49514–49516, 49518, 49523, 49525, 49534, 49546, 49548, 49555, 49560, 49588, 49594 |

| Area code | 616 |

| FIPS code | 26-34000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0627105[3] |

| Website | GrandRapidsMI.gov |

Situated along the Grand River approximately 25 miles (40 km) east of Lake Michigan, it is the economic and cultural hub of West Michigan, as well as one of the fastest-growing cities in the Midwest.[6] A historic furniture manufacturing center, Grand Rapids is home to five of the world's leading office furniture companies and is nicknamed "Furniture City". Other nicknames include "River City" and more recently, "Beer City" (the latter given by USA Today[7] and adopted by the city as a brand).[8] The city and surrounding communities are economically diverse, based in the health care, information technology, automotive, aviation, and consumer goods manufacturing industries, among others.

Grand Rapids was the childhood home of U.S. President Gerald Ford, who is buried with his wife Betty on the grounds of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum in the city.[9] The city's Gerald R. Ford International Airport and Gerald R. Ford Freeway are named after him.

History

Native American settlement

For thousands of years, succeeding cultures of indigenous peoples occupied the area. Over 2000 years ago, people associated with the Hopewell culture occupied the Grand River Valley.[10] Later, a tribe from the Ottawa River traveled to the Grand River valley, fighting three battles with the Prairie Indians who were established in the area.[11] The tribe later split, with the Chippewas settling in the northern lower peninsula, the Pottawatomies staying south of the Kalamazoo River and the Odawa staying in central Michigan.[11]

By the late 1600s, the Odawa, who occupied territory around the Great Lakes and spoke one of the numerous Algonquian languages, moved into the Grand Rapids area and founded several villages along the Grand River.[10][12] The Odawa established on the river, which they called O-wash-ta-nong, or far-away-water due to the river's length, where they "raised corn, melons, pumpkins and beans, to which they added game of the woods and the fish from the streams".[11]

In 1740, an Odawa man who would later be known as Chief Noonday or Nowaquakezick and become the future chief of the Odawa, was born.[13][14] Between 1761 and 1763, Chief Pontiac visited the area annually, gathering over 3,000 natives and asking them to volunteer to lay siege to the British fort in Detroit, which would culminate into Pontiac's War.[11] By the end of the 1700s, there were an estimated 1,000 Odawa in the Kent County area.[11]

Trading post

After the French established territories in Michigan, Jesuit missionaries and traders traveled down Lake Michigan and its tributaries.[11] At the start of the 19th century, European fur traders (mostly French Canadian and Métis) and missionaries established posts in the area among the Odawa. They generally lived in peace, trading European metal and textile goods for fur pelts.

In 1806, Joseph and his wife Madeline La Framboise, who was Métis, traveled by canoe from Mackinac and established the first trading post in West Michigan in present-day Grand Rapids on the banks of the Grand River, near what is now Ada Township, the junction of the Grand and Thornapple Rivers. They were French-speaking and Roman Catholic. They likely both spoke Odawa, Madeline's maternal ancestral language. In the fall of 1806, Joseph was fatally stabbed by a member of the Potawatomi tribe named Nequat. Joseph had been with his family and an entourage of voyageurs traveling between Grand River and Grand Rapids. The Indian had insisted that Joseph trade liquor with him. When Joseph refused, the Indian left only to return at dusk when Joseph, who faithfully performed the ritual of Angelus every day at that time, was in prayer. The Indian stabbed the trader, fatally wounding him, leaving Magdelaine suddenly a widow at age twenty-four.[15]

The next spring, a delegation from the Potawatomi tribe brought the offending Indian, Nequat, before Magdelaine for her sentence upon him for the death of her husband. It was their tradition for the victim’s family to avenge deaths within that tribe. Magdeliane, true to her Roman Catholic beliefs, refused to sentence him and in an act of forgiveness told the astonished Potawatomi tribe members to let him go and that God would be his judge. Though she had forgiven him, the tribe had not and Nequat’s body was found stabbed with its own knife the next season.[16]

After the murder of her husband in 1806 while en route to Grand Rapids, Madeline La Framboise carried on the trade business, expanding fur trading posts to the west and north, creating a good reputation among the American Fur Company. La Framboise, whose mother was Odawa and father French, later merged her successful operations with the American Fur Company.[11]

By 1810, Chief Noonday established the village of Bock-a-tinck on the northwest side of present-day Grand Rapids near Bridge Street with about 500 Odawa, though the population would grow to over 1,000 on occasion.[13][14] During the War of 1812, Noonday was allied with Tecumseh during the Battle of the Thames. Tecumseh was killed in this battle, and Noonday inherited his tomahawk and hat.[17] A second village existed lower down the river with its center located at the intersection of what is now Watson Street and National Avenue, with Chief Black Skin – known by his native name as Muck-i-ta-oska or Mukatasha and was son of Chief Noonday – leading the village.[14]

European settlement

In 1820, General Lewis Cass, who was on his way to negotiate the first Treaty of Chicago with a group of 42 men, commissioned Charles Christopher Trowbridge to establish missions for Native Americans in the Grand River Valley to evangelize Native Americans.[18][14] In 1821, the Council of Three Fires signed the first Treaty of Chicago, ceding to the United States all lands in Michigan Territory south of the Grand River, except for several small reservations, and required a native to prepare land in the area to establish a mission.[14][19] The treaty also included "One hundred thousand dollars to satisfy sundry individuals, in behalf of whom reservations were asked, which the Commissioners refused to grant" of which Joseph La Framboise received 1,000 dollars immediately and 200 dollars a year, for life.[19] Madeline La Framboise retired the trading post to Rix Robinson in 1821 and returned to Mackinac.[11] That year, Grand Rapids was described as being the home of an Odawa village of about 50 to 60 huts on the north side of the river near the 5th Ward, with Kewkishkam being the village chief and Chief Noonday being the chief of the Odawa.[18]

The first permanent European-American settler in the Grand Rapids area was Isaac McCoy, a Baptist minister.[18] In 1823, McCoy, Paget, a Frenchman who brought along a Native American pupil, and a government worker traveled to Grand Rapids from Carey Mission near present-day Niles, Michigan to arrange a mission they called the "Thomas Mission", though negotiations fell through with the group returning to the Carey Mission for the Potawatomi on the St. Joseph River.[18][14] The government worker stayed into 1824 to establish a blacksmith shop, though the shop was burned down by the Odawa.[14] Later in May 1824, Baptist missionary Reverend Leonard Slater traveled with two settlers to Grand Rapids to perform missionary work, though the group began to return to the Carey Mission after only three days due to threats.[18][14] While the group was returning, they encountered Chief Noonday who asked for the group to stay and establish a mission, believing that the Odawa adapting to European customs was the only chance for them to stay in the area.[14] The winter of 1824 was difficult, with Slater's group having to resupply and return before the spring.[14][18] Chief Noonday, deciding to be an example for the Odawa, chose to be baptized by Slater in the Grand River, though some of his followers believed that this was a wrestling match between the two that Slater won.[14] Slater then erected the first settler structures in Grand Rapids, a log cabin for himself and a log schoolhouse.[18] In 1825, McCoy returned and established a missionary station.[20] He represented the settlers who began arriving from Ohio, New York and New England, the Yankee states of the Northern Tier.

Shortly after, Detroit-born Louis Campau, known as the official founder of Grand Rapids, was convinced by fur trader William Brewster, who was in a rivalry with the American Fur Company, to travel to Grand Rapids and establish trade there.[18] In 1826, Campau built his cabin, trading post, and blacksmith shop on the south bank of the Grand River near the rapids, stating the Native Americans in the area were "friendly and peaceable".[18] Campau returned to Detroit, then returned a year later with his wife and $5,000 of trade goods to trade with the Odawa and Ojibwa, with the only currency being fur.[18] Campau's younger brother Touissant would often assist him with trade and other tasks at hand.[18]

Lucius Lyon, a Yankee Protestant who would later become a rival to Campau, was contracted by the federal government to survey the Grand River Valley in the fall of 1830 and in the first quarter of 1831, the federal survey of the Northwest Territory reached the Grand River, with Lyon using a surveyor's compass and chain to set the boundaries for Kent County, named after prominent New York jurist James Kent.[18][14] In 1833, a land office was established in White Pigeon, Michigan, with Campau and fellow settler Luther Lincoln seeking land in the Grand River valley.[18] Lincoln purchased land in what is now known as Grandville, while Campau became perhaps the most important settler when he bought 72 acres (291,000 m2) from the federal government for $90 and named his tract Grand Rapids. Over time, it developed as today's main downtown business district.[10] In the spring of 1833, Campau sold to Joel Guild, who traveled from New York, a plot of land for $25.00, with Guild building the first frame structure in Grand Rapids, which is now where McKay Tower stands.[18][21] Guild later became the postmaster, with mail at the time being delivered monthly from the Gull Lake, Michigan to Grand Rapids.[18] Grand Rapids in 1833 was only a few acres of land cleared on each side of the Grand River, with oak trees planted in light, sandy soil standing between what is now Lyon Street and Fulton Street.[18]

By 1834, the settlement had become more organized. Rev. Turner had established a school on the east side of the river, with children on the west side of the river being brought to school every morning by a Native American on a canoe who would shuttle them across the river. Multiple events happened at Guild's frame structure, including the first marriage in the city, one that involved his daughter Harriet Guild and Barney Burton, as well as the first town meeting that had nine voters. It was also this year Campau began constructing his own frame building—the largest at the time—near present-day Rosa Parks Circle.[18]

In 1835, many settlers arrived in the area with the population growing to about 50 people, including its first doctor, Dr. Wilson, who was supplied with equipment from Campau.[18] Lucius Lyon, using his knowledge from surveying the area, returned to Grand Rapids to purchase the rest of the prime land and called his plot the Village of Kent.[18][14] When Lyon and his partner N. O. Sergeant returned after their purchase, they arrived along with a posse of men carrying shovels and picks, intending to build a mill race. The group arrived to the music of a bugle which startled the settlement, with Chief Noonday offering Campau assistance to drive back Lyon's posse believing they were invaders. Also that year, Rev. Andrew Vizoisky, a Hungarian native educated in Catholic institutions in Austria, arrived, presiding over the Catholic mission in the area until his death in 1852.[18]

That year, Campau, Rix Robinson, Rev. Slater, and the husband of Chief Noonday's daughter, Meccissininni, traveled to Washington, D.C. to speak about the purchase of Odawa land on the west side of the river with President Andrew Jackson.[13] Jackson was originally unimpressed with Meccissininni, though Meccissininni, who often acquired white customs, asked Jackson for a similar suit to the one the president was wearing. While later wearing his suit that was made similar to Jackson's, Meccissininni also unknowingly imitated Jackson's hat, placing a piece of weed in it, which impressed Jackson since it symbolized mourning the death of his wife.[13]

John Ball, representing a group of New York land speculators, bypassed Detroit for a better deal in Grand Rapids traveling to the settlement in 1836. Ball declared the Grand River valley "the promised land, or at least the most promising one for my operations".[22] That year, the first steamboat was constructed on the Grand River named the Gov. Mason, though the ship wrecked two years later in Muskegon.[18] Yankee migrants (primarily English-speaking settlers) and others began migrating from New York and New England through the 1830s. Ancestors of these people included not only English colonists but people of mixed ethnic Dutch, Mohawk, French Canadian, and French Huguenot descent from the colonial period in New York. However, after 1837, the area saw poor times, with many of the French returning to their places of origin, with poverty hitting the area for the next few years.[18]

The first Grand Rapids newspaper, The Grand River Times, was printed on April 18, 1837, describing the village's attributes, stating:[18]

Though young in its improvements, the site of this village has long been known and esteemed for its natural advantages. It was here that the Indian traders long since made their great depot.

The Grand River Times continued, saying the village had grown quickly from a few French families to about 1,200 residents, the Grand River was "one of the most important and delightful to be found in the country," and described the changing Native American culture in the area.[18]

Incorporation and cityhood

By 1838, the settlement incorporated as a village, and encompassed approximately .75 square miles (1.9 km2).[23]

An outcropping of gypsum, where Plaster Creek enters the Grand River, was known to the Native American inhabitants of the area. Pioneer geologist Douglass Houghton commented on this find in 1838.[24][25] Settlers began to mine this outcrop in 1841, initially in open cast mines, but later underground mines as well. Gypsum was ground locally for use as a soil amendment known as "land plaster."

The first formal census in 1845 recorded a population of 1,510[26] and an area of 4 square miles (10 km2).[26] The city of Grand Rapids was incorporated April 2, 1850.[27] It was officially established on May 2, 1850, when the village of Grand Rapids voted to accept the proposed city charter. The population at the time was 2,686. By 1857, the city of Grand Rapids' area totaled 10.5 square miles (27 km2).[23] Through the 1850s, the land containing forty-six Indian mounds located on the west side between Bridge Street and the Grand River to the south were sold by the United States government, with the mounds being destroyed to fill low-lying land in the area while the Native American artifacts contained within were taken or sold to museums, including the Grand Rapids Public Museum.[28] In October 1870, Grand Rapids became a desired location for immigrants, with about 120 Swedes arriving in the United States to travel and create a "colony" in the area in one week.[29]

During the second half of the nineteenth century, the city became a major lumbering center, processing timber harvested in the region. Logs were floated down the Grand River to be milled in the city and shipped via the Great Lakes. The city became a center of fine wood products as well. By the end of the century, it was established as the premier furniture-manufacturing city of the United States.[30] It was the Centennial Exposition of 1876 in Philadelphia that brought attention to Grand Rapids' furniture on the national stage, providing a new growing industry to help the city recover from the Panic of 1873.[31][32] In 1880, the country's first hydro-electric generator was put to use on the city's west side.[33]

Twentieth century: Furniture City

Due to its flourishing furniture industry, Grand Rapids began being recognized as "Furniture City". Grand Rapids was also an early center for the automobile industry, as the Austin Automobile Company operated there from 1901 until 1921.

Furniture companies included the William A. Berkey Company and its successors, Baker Furniture Company, Williams-Kimp, and Widdicomb Furniture Company.[34] The furniture industry began to grow significantly into the twentieth century; in 1870 there were eight factories employing 280 workers and by 1911, Old National Bank wrote that about 8,500 were employed by forty-seven factories.[31][35] At least a third of the workers in Grand Rapids were employed by furniture companies.[31] The Grand Rapids Furniture Record was the trade paper for the city's industry. Its industries provided jobs for many new immigrants from Europe in the late 19th and early 20th century, and a Polish neighborhood developed on the west side of the city.

Strike of 1911

By the early twentieth century, the quality of furniture produced in Grand Rapids was renowned throughout furniture industry, mainly due to the skill of its workers.[35] Government reports in 1907 revealed that while Grand Rapids lead the industry in product output, though its furniture workers were paid lower wages than in other areas.[35] After a minor dispute, workers were inspired to form labor unions; workers requested furniture companies to increase wages, less working hours, the creation of collective bargaining and the institution of a minimum wage to replace piece work.[31][35] The furniture businesses refused to respond with unions as they believed that any meeting represented recognition of unions.[31][35]

Workers in Grand Rapids then began a four month long general strike on April 19, 1911.[31][36] Much of the public, the mayor, the press and the Catholic diocese supported the strike, believing that the unwillingness of business leaders to negotiate was unjust. Skilled and unskilled factory labor was mainly Dutch (60 percent) and Polish (25 percent), primarily immigrants. According to the 1911 Immigration Commission report, the Dutch had an average of 8 percent higher wages than the Poles even when they did the same work. The pay difference was based on seniority and not ethnicity, but given that the Dutch had arrived earlier, seniority was linked to ethnicity.[31][35] Ultimately, the Christian Reformed Church – where the majority of Dutch striking workers congregated – and the Fountain Street Church – led opposition to the strike, which resulted in its end on August 19, 1911.[31][36]

The strike resulted with substantial changes to the governmental and labor structure of the city.[36] With businesses upset with Mayor Ellis for supporting the strike lobbied for the city to change from a twelve-ward government – which more accurately represented the city's ethnic groups – to a smaller three ward system that placed more power into the demands of Dutch citizens, the city's largest demographic.[37][36] Some workers who participated in the strike were blacklisted by companies and thousands of dissatisfied furniture workers emigrated to higher paying regions.[31][35]

Move to retail and suburbanization

Shifting from its furniture-centric industry, downtown Grand Rapids temporarily became a retail destination for the region, hosting four department stores: Herpolsheimer's (Lazarus), Jacobson's, Steketee's (founded in 1862), and Wurzburg's. In 1945, Grand Rapids became the first city in the United States to add fluoride to its drinking water. National home furnishing conferences were held in Grand Rapids for about seventy-five years, concluding in the 1960s. By that time, the furniture-making industry had largely shifted to North Carolina.[38]

As with many older cities in the United States, retail in the city suffered as the population moved to suburbs in the postwar era with federal subsidization of highway construction. The Grand Rapids suburb Wyoming began to develop rapidly in the 1950s and 1960s following the opening of retail outlets such as Rogers Plaza and Wyoming Village Mall on 28th Street, with developments built so quickly that they were finished without utilities.[39] Consolidation of department stores occurred in Grand Rapids and nationally in the 1980s and 1990s.

Geography

Neighborhoods

- Heritage Hill

- Creston

- Eastown

- Ottawa Hills

- Alger Heights

- Belknap Lookout

- Heartside

Topography

Grand Rapids developed on the banks of the Grand River, where there was once a set of rapids, at an altitude of 610 feet (186 m) above sea level. Ships could navigate on the river up to this fall line, stopping because of the rapids. The river valley is flat and narrow, surrounded by steep hills and bluffs. The terrain becomes more rolling hills away from the river. The countryside surrounding the metropolitan area consists of mixed forest and farmland, with large areas of orchards to the northwest. It is approximately 25 mi (40 km) east of Lake Michigan. The state capital of Lansing lies about 60 mi (97 km) to the east-by-southeast, and Kalamazoo is about 50 mi (80 km) to the south.

Grand Rapids is divided into four quadrants, which form a part of mailing addresses in Kent County. The quadrants are NE (northeast), NW (northwest), SE (southeast), and SW (southwest). Fulton Street serves as the north–south dividing line, while Division Avenue serves as the east–west dividing line separating these quadrants.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 45.27 square miles (117.25 km2), of which, 44.40 square miles (115.00 km2) of it is land and 0.87 square miles (2.25 km2) is water.[40]

Climate

| Grand Rapids | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Grand Rapids has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa),[42] with very warm and humid summers, cold and snowy winters, and short and mild springs and autumns.

Even though it is in the middle of the continent, the city experiences some maritime effects due to its location east of Lake Michigan, including a high number of cloudy days during the late fall and winter, delayed heating in the spring, delayed cooling in fall, somewhat moderated temperatures during winter and lake effect snow. The city averages 75.6 in (192 cm) of snow a year, making it one of the snowiest major cities in the United States.[43] The area often receives quick and sudden lake effect snowstorms, producing significant amounts of snowfall.

The months of March, April, October and November are transitional months and the weather can vary. March has experienced a record high of 87 °F (31 °C) and record low of −13 °F (−25 °C). The average last frost date in spring is May 1, and the average first frost in fall is October 11, giving the area a growing season of 162 days.[44] The city is in plant hardiness zone 6a, while outlying areas are 5b. Some far western suburbs closer to the insulating effect of Lake Michigan are in zone 6b.[45] Summers are warm or hot, and heat waves and severe weather outbreaks are common during a typical summer.

The average temperature of the area is 49 °F (9 °C). The highest temperature in the area was recorded on July 13, 1936, at 108 °F (42 °C), and the lowest was recorded on February 13–14, 1899, at −24 °F (−31 °C).[46] During an average year, sunshine occurs in 46% of the daylight hours. On 138 nights, the temperature dips to below 32 °F (0 °C). On average, 9.2 days a year have temperatures that meet or exceed the 90 °F (32 °C) mark, and 5.6 days a year have lows that are 0 °F (−18 °C) or colder.

The coldest maximum temperature on record was −6 °F (−21 °C) in 1899, whereas the most recent subzero Fahrenheit daily maximum was −2 °F (−19 °C) in 1994.[47] During the reference period of 1991 to 2020, the coldest daily maximum on average was 11 °F (−12 °C).[47] Summer nights influenced by the lake can be hot and muggy on occasion. The warmest night on record was 82 °F (28 °C) in 1902 and lows above 72 °F (22 °C) have been measured in every month between April and October.[47] On average, the warmest low of the year stood at 74 °F (23 °C) for the 1991–2020 normals.[47]

In April 1956, the western and northern portions of the city and its suburbs were hit by a violent tornado which locally produced F5 damage and killed 18 people.[48]

With the Grand River flowing through the center of Grand Rapids, the city has been prone to floods. From March 25 to 29, 1904, more than one-half of the entire populated portion of the city lying on the west side of the river was completely underwater, over twenty-five hundred houses, affecting fourteen thousand persons, being completely surrounded. On March 28, the river registered at 19.6 feet (6.0 m), more than two feet (0.61 m) above its highest previous mark.[49]

More than one-hundred years later, the 2013 Grand Rapids flood occurred from April 12 to 25, 2013, with the river cresting at 21.85 feet (6.66 m) on the 21st, causing thousands of residents to evacuate their homes and over $10 million in damage.[50]

| Climate data for Grand Rapids, Michigan (Gerald Ford Int'l), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1892−present[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 68 (20) |

69 (21) |

87 (31) |

90 (32) |

95 (35) |

102 (39) |

108 (42) |

102 (39) |

98 (37) |

89 (32) |

81 (27) |

69 (21) |

108 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 51 (11) |

52 (11) |

68 (20) |

79 (26) |

86 (30) |

92 (33) |

92 (33) |

91 (33) |

88 (31) |

79 (26) |

65 (18) |

54 (12) |

94 (34) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 31.0 (−0.6) |

33.7 (0.9) |

44.5 (6.9) |

57.8 (14.3) |

69.8 (21.0) |

79.4 (26.3) |

83.1 (28.4) |

80.9 (27.2) |

73.9 (23.3) |

60.7 (15.9) |

47.2 (8.4) |

36.1 (2.3) |

58.2 (14.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 24.8 (−4.0) |

26.6 (−3.0) |

35.7 (2.1) |

47.6 (8.7) |

59.2 (15.1) |

68.9 (20.5) |

72.8 (22.7) |

71.1 (21.7) |

63.5 (17.5) |

51.5 (10.8) |

40.0 (4.4) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

49.3 (9.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 18.6 (−7.4) |

19.5 (−6.9) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

37.3 (2.9) |

48.6 (9.2) |

58.3 (14.6) |

62.5 (16.9) |

61.2 (16.2) |

53.1 (11.7) |

42.2 (5.7) |

32.8 (0.4) |

24.7 (−4.1) |

40.5 (4.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −3 (−19) |

0 (−18) |

8 (−13) |

23 (−5) |

33 (1) |

44 (7) |

51 (11) |

49 (9) |

39 (4) |

29 (−2) |

16 (−9) |

6 (−14) |

−6 (−21) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −22 (−30) |

−24 (−31) |

−13 (−25) |

3 (−16) |

21 (−6) |

32 (0) |

41 (5) |

39 (4) |

27 (−3) |

18 (−8) |

−10 (−23) |

−18 (−28) |

−24 (−31) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.52 (64) |

2.12 (54) |

2.39 (61) |

3.99 (101) |

4.00 (102) |

3.94 (100) |

3.86 (98) |

3.55 (90) |

3.43 (87) |

4.02 (102) |

3.10 (79) |

2.48 (63) |

39.40 (1,001) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 22.6 (57) |

17.2 (44) |

7.6 (19) |

2.0 (5.1) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

7.1 (18) |

20.8 (53) |

77.6 (197) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 9 (23) |

9 (23) |

6 (15) |

1 (2.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2 (5.1) |

6 (15) |

12 (30) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 16.8 | 13.1 | 11.8 | 12.8 | 12.5 | 10.7 | 10.0 | 9.9 | 10.2 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 15.5 | 148.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 14.9 | 11.2 | 5.9 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 4.5 | 11.9 | 50.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 77.2 | 74.2 | 71.1 | 66.8 | 65.4 | 68.1 | 69.6 | 73.3 | 76.1 | 74.6 | 76.9 | 79.5 | 72.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 88.3 | 116.0 | 168.2 | 210.2 | 255.9 | 286.8 | 296.5 | 264.2 | 206.0 | 152.4 | 82.0 | 62.1 | 2,188.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 30 | 39 | 45 | 52 | 56 | 62 | 64 | 61 | 55 | 45 | 28 | 22 | 49 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961−1990)[47][52][53] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

The city skyline shows the Amway Grand Plaza Hotel, formerly the Pantlind, which reopened in 1981 after extensive renovations by Marvin DeWinter & Associates. This work included the addition of a 29–story glass tower offering panoramic views of the city, river and surrounding area. The Pantlind Hotel's original architects, Warren & Wetmore, were inspired by the work of the Scottish neoclassical architect Robert Adam. In its prime, the hotel was rated as one of the top ten hotels in the US. The hotel features several restaurants well known in Grand Rapids. The hotel is owned by Amway Hotel Collection, a subsidiary of Amway's holding company Alticor.[54]

Other prominent large buildings include the JW Marriott Grand Rapids, the first JW Marriott Hotel in the Midwest. It is themed from cityscapes of Grand Rapids' sister cities: Omihachiman, Japan; Bielsko-Biała, Poland; Perugia, Italy; Ga District, Ghana; and Zapopan, Mexico. When the hotel opened, Amway Hotel corporation hired photographer Dan Watts to travel to each of the sister cities and photograph them for the property. Each floor of the hotel features photography from one of the cities, which is unique to that floor. Cityscapes of these five cities are alternated in order, up the 23 floors.

The city's tallest building is the River House Condominiums, a 34-story (123.8 m) condominium tower completed in 2008 that stands as the tallest all-residential building in the state of Michigan.[55]

Grand Rapids is also home to two large urban nature centers. The Calvin Ecosystem Preserve and Native Gardens, operated by Calvin University on the city's southeast side, is 104 acres (42 ha). It is home to over 44 acres (18 ha) of public-access nature trails, a 60-acre (24 ha), restricted-access wildlife preserve, as well as the Bunker Interpretive Center, which hosts university classes and educational programs for the wider community.[56] The Blandford Nature Center, located on the city's northwest side, opened in 1968 and contains extensive nature trails, an animal hospital, and a "heritage village" made up of several well-preserved 19th-century buildings, including a log cabin, schoolhouse, and barn.[57] The nature center is also home to Blandford School, a highly selective environmental education program for sixth graders from the metropolitan region, which is run by Grand Rapids Public Schools and serves as a feeder school for City High-Middle School. At 264 acres (107 ha), Blandford is one of the largest urban nature centers in the United States.[58]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 2,686 | — | |

| 1860 | 8,085 | 201.0% | |

| 1870 | 16,507 | 104.2% | |

| 1880 | 32,016 | 94.0% | |

| 1890 | 60,278 | 88.3% | |

| 1900 | 87,565 | 45.3% | |

| 1910 | 112,571 | 28.6% | |

| 1920 | 137,634 | 22.3% | |

| 1930 | 168,592 | 22.5% | |

| 1940 | 164,292 | −2.6% | |

| 1950 | 176,515 | 7.4% | |

| 1960 | 177,313 | 0.5% | |

| 1970 | 197,649 | 11.5% | |

| 1980 | 181,843 | −8.0% | |

| 1990 | 189,126 | 4.0% | |

| 2000 | 197,800 | 4.6% | |

| 2010 | 188,036 | −4.9% | |

| 2020 | 198,917 | 5.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[59] 2010[60] 2020[61] | |||

2020 census

| Race / Ethnicity | Pop 2010[60] | Pop 2020[61] | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 110,890 | 114,290 | 58.97% | 57.46% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 37,890 | 36,493 | 20.15% | 18.35% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 788 | 659 | 0.42% | 0.33% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 3,445 | 4,483 | 1.83% | 2.25% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 58 | 70 | 0.03% | 0.04% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 287 | 916 | 0.15% | 0.46% |

| Mixed Race/Multi-Racial (NH) | 5,421 | 9,209 | 2.88% | 4.63% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 29,261 | 32,797 | 15.56% | 16.49% |

| Total | 188,040 | 198,917 | 100.00% | 100.00% |

Note: The US Census treats Hispanic/Latino as an ethnic category. This table excludes Latinos from the racial categories and assigns them to a separate category. Hispanics/Latinos can be of any race.

2010 census

As of the 2010 census,[62] there were 188,036 people, 72,126 households, and 41,015 families residing in the city. The population density was 4,235.1 inhabitants per square mile (1,635.2/km2). There were 80,619 housing units at an average density of 1,815.7 per square mile (701.0/km2). The city's racial makeup was 64.6% White (59.0% Non-Hispanic White[63]), 20.9% African American, 0.7% Native American, 1.9% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 7.7% from other races, and 4.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino residents of any race were 15.6% of the population.[64]

Of the 72,126 households, 31.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.5% were married couples living together, 16.4% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.0% had a male householder with no wife present, and 43.1% were non-families. 32.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.49 and the average family size was 3.20.

The median age in the city was 30.8 years. 24.7% of residents were under the age of 18; 14.5% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 28.6% were from 25 to 44; 21.2% were from 45 to 64; and 11.1% were 65 years of age or older. The city's gender makeup was 48.7% male and 51.3% female.

2000 census

There were 73,217 households, of which 32.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.3% were married couples living together, 15.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.4% were non-families. 30.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.57 and the average family size was 3.24.

In the city, the age distribution shows 27.0% under the age of 18, 13.1% from 18 to 24, 31.5% from 25 to 44, 16.7% from 45 to 64, and 11.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 30 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 92.5 males.

The city's median household income was $37,224, and the median family income was $44,224. Males had a median income of $33,050 versus $26,382 for females. The city's per capita income was $17,661. 15.7% of the population and 11.9% of families were below the poverty line. Out of the total people living in poverty, 19.4% are under the age of 18 and 10.4% are 65 or older.

Ethnicity

According to a 2007 American Community Survey, the largest ancestry groups in Grand Rapids reported (not including "American") were those of German (23.4% of the population), Dutch (21.2%), Irish (11.4%), English (10.8%), Polish (6.5%), and French (4.1%) heritage.[65]

In recent decades, Grand Rapids and its suburban areas have seen their Latino communities grow. Between 2000 and 2010 the Latino population in Grand Rapids grew from 25,818 to 29,261, increasing over 13% in a decade.[66]

Into the 21st century, the African American population of Grand Rapids continually declined.[67] In 2015, Grand Rapids was rated as the second-worst city for African Americans, behind only Milwaukee to succeed economically based on disparities in employment, income, and home ownership levels.[68] In 2022, The Grand Rapids Press reported that the population of African Americans in the city declined 4% over the decade, with the newspaper writing that gentrification, increasing rent, urban sprawl into the neighboring cities of Kentwood and Wyoming—which experienced increased African American population growth—and New Great Migration trends contributed to the loss of black residents.[67][69] The decline of African American residents occurred primarily in the northeast and southeast areas of the city.[70]

Religion

Grand Rapids has a significant Dutch Reformed population. The Christian Reformed Church in North America (CRCNA) has a large following in Grand Rapids; its denominational offices are on the city's southeast side. The CRCNA has over 230 congregations and almost 100,000 members in Michigan as of 2010.[71] The denomination is concentrated in the western part of the state, where a substantial number of immigrants from the Netherlands settled; most were followers of the Reformed faith who took part in the Secession of 1834.[72] As of 2012, the Christian Reformed Church in North America has nearly 1,100 congregations and over 250,000 members nationwide.[73] The Grand Rapids-Wyoming Metropolitan Area has 149 Christian Reformed Churches with 77,389 members.[74]

The Reform Judaism congregation of Temple Emanuel was founded in 1857 and the fifth oldest Reform congregation in the United States.[75] The congregation built its first synagogue in 1882 on the corner of Fountain and Ransom Streets. The current location was constructed in 1952.[76]

Grand Rapids is home to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Grand Rapids, which was created on May 19, 1882, by Pope Leo XIII. The Diocese comprises 176,098 Catholics in West Michigan, 102 parishes, and five high schools: Catholic Central High School, Grand Rapids; Muskegon Catholic Central High School, Muskegon; St. Patrick High School, Portland; Sacred Heart Academy, Grand Rapids; and West Catholic High School, Grand Rapids.[77] David John Walkowiak is the Bishop of Grand Rapids.

The Reformed Church in America (RCA) has about 154 congregations and 76,000 members mainly in Western Michigan,[78] heavily concentrated in the cities in Grand Rapids, Holland, and Zeeland. The denomination's main office is also in Grand Rapids.[79] The Grand Rapids-Wyoming metropolitan area has 86 congregations with almost 49,000 members. The Protestant Reformed Churches in America (PRCA) traces its roots to the First Protestant Reformed Church (Grand Rapids, Michigan) whose pastor was Herman Hoeksema, the founder of the church.[80] A majority of the PRCA's Classis East churches, about 13 congregations, are around Grand Rapids.[74][81][82]

.jpg.webp)

The United Reformed Churches in North America has 12 congregations in Grand Rapids area; these congregations form the Classis of Michigan.[83] The Heritage Reformed Congregations' flagship and largest church is in Grand Rapids. The Netherlands Reformed Congregations in North America has 2 churches.[84] The PC(USA) had 12 congregations and 7,000 members in the Grand Rapids-Wyoming Metropolitan statistical area, the United Church of Christ had also 14 congregations and 5,400 members.[74]

The offices of the West Michigan Annual Conference of the United Methodist Church are in the East Hills Neighborhood of Grand Rapids. The West Michigan Annual Conference represents more than 400 local United Methodist churches in the western half of the lower peninsula with approximately 65,000 members in total.[85] Grand Rapids is also home to the United Methodist Community House, whose mission is to increase the ability of children, youth, adults and families to succeed in a diverse community.[86] In 2010, The United Methodist Church had 61 congregations and 21,450 members in the Grand Rapids Metropolitan area.[74]

Economy

| Top Employers in Grand Rapids Metro (2019)

Source: The Right Place | |||||

| Rank | Company/Organization | # | |||

| 1 | Spectrum Health | 25,000 | |||

| 2 | Meijer | 10,340 | |||

| 3 | Mercy Health | 8,500 | |||

| 4 | Gentex | 5,800 | |||

| 5 | Gordon Food Service | 5,000 | |||

| 6 | Amway Corporation | 3,791 | |||

| 7 | Herman Miller | 3,621 | |||

| 8 | Perrigo Company | 3,500 | |||

| 9 | Steelcase Inc. | 3,500 | |||

| 10 | Farmers Insurance Group | 3,500 | |||

| 11 | Grand Valley State University | 3,306 | |||

| 12 | Lacks Enterprises | 3,000 | |||

| 13 | Grand Rapids Public Schools | 2,800 | |||

| 14 | Arconic | 2,350 | |||

| 15 | Hope Network | 2,162 | |||

| 16 | Metro Health Hospital | 2,100 | |||

| 17 | Roskam Baking Co. | 2,090 | |||

| 18 | Fifth Third Bank | 2,280 | |||

| 19 | Haworth | 2,000 | |||

| 20 | SpartanNash | 2,000 | |||

.svg.png.webp)

Headquartered in Grand Rapids, Spectrum Health is West Michigan's largest employer, with 25,600 staff and 1,700 physicians in 2017.[87] Spectrum Health's Meijer Heart Center, Lemmen-Holton Cancer Pavilion, and Butterworth Hospital, a level I trauma center, are on the Grand Rapids Medical Mile, which has world-class facilities that focus on the health sciences. They include the Van Andel Research Institute, Grand Valley State University's Cook-DeVos Center for Health Sciences, and the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine medical school's Secchia Center, along with Ferris State University's College of Pharmacy. Nearly a billion dollars has been invested in the Spectrum Health Cancer Pavilion, the Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children's Hospital, and the expansion to the Van Andel Institute. These facilities have attracted many health science businesses to the area.

Grand Rapids has long been a center for manufacturing, dating back to its original roots in furniture manufacturing. Office furniture manufacturers such as American Seating, Steelcase (and its subsidiaries Coalesse and Turnstone), Haworth, and Herman Miller are based in and around the Grand Rapids area.[88][89][90][91][92][93] In 1881, the Furniture Manufacturers Association (FMA) was organized in Grand Rapids; making it the country's first furniture manufacturing advocacy group.[94] The Kindel Furniture Company[95] and the Hekman Furniture Company[96] have been designing and manufacturing furniture in Grand Rapids since 1912 and 1922 respectively.

The Grand Rapids area is also known for its automobile and aviation manufacturing industries, with GE Aviation Systems having a location in the city.[97]

The Grand Rapids area is home to a number of well-known companies including Alticor/Amway (a multi-level marketing company), Bissell (a privately owned vacuum cleaner and floor care product manufacturer), SpartanNash (a food distributor and grocery store chain), Foremost Insurance Company (a specialty lines insurance company), Meijer (a regional supercenter chain), GE Aviation (formerly Smiths Industries, an aerospace products company), Wolverine World Wide (a designer and manufacturer of shoes, boots and clothing), Universal Forest Products (a building materials company), and Schuler Books & Music, one of the country's largest independent bookstores.

The city is known as a center of Christian publishing, home to Zondervan, Kregel Publications, Eerdmans Publishing and Our Daily Bread Ministries.

The city and its surrounding region house a successful food processing and agribusiness industry, which has experienced a 10-year job growth rate of 45% from 2009-2019. With Michigan being the second most agriculturally diverse state in the nation, the Greater Grand Rapids region is well-known for its fruit production. Due to its proximity to Lake Michigan, the climate is considered especially prime for apple, peach, and blueberry farming. Greater Grand Rapids produces 1/3 of Michigan's total agricultural sales.

In 2010 Grand Rapids was named the "most sustainable midsize city in the U.S." by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Civic Leadership Center and Siemens Corp. Grand Rapids was chosen over finalist cities Davenport, Iowa and Hoover, Alabama.[98] The city has also been named in several other notable rankings since, including:

- No. 1 Cities with the Most Manufacturing Jobs: Grand Rapids/Kentwood (Smartest Dollar, 2020)[99]

- No. 1 Mid-Sized Metro for Economic Growth Potential: Grand Rapids (Business Facilities, 2019)[100]

- No. 1 Top Metro for Sustainable Development: Grand Rapids (Site Selection Magazine, 2019)[101]

- Top 20 Cities for 7-Year Job Growth: Grand Rapids (Reuters, 2019)[102]

Education

K–12 public education is provided by the Grand Rapids Public Schools (GRPS) as well as a number of charter schools. City High-Middle School, a magnet school for academically talented students in the metropolitan region operated by GRPS, is habitually ranked among the nation's top high schools.[103] Grand Rapids is also home to the oldest co-educational Catholic high school in the United States, Catholic Central High School.[104] National Heritage Academies, which operates charter schools across several states, has its headquarters in Grand Rapids.[105]

Grand Rapids is home to several colleges and universities. The private, religious schools: Aquinas College, Calvin University, Cornerstone University, Grace Christian University, and Kuyper College, each have a campus within the city. The seminaries Calvin Theological Seminary, Grand Rapids Theological Seminary, and Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary are in Grand Rapids. Thomas M. Cooley Law School, a private institution, also has a campus in Grand Rapids. Northwood University, a private university with its main campus in Midland, Michigan, has a satellite campus downtown near the "medical mile." Davenport University, a private, non-profit, multi-location university with 14 campuses statewide, has its main campus just outside Grand Rapids.

As for public tertiary institutions, Grand Rapids Community College (GRCC) maintains a campus downtown and facilities in other parts of the city and surrounding region.

Grand Valley State University, with its main campus in nearby Allendale, continues to develop its presence downtown by expanding its Pew Campus, begun in the 1980s on the west bank of the Grand River.[106] This downtown campus comprises 67 acres (27 ha) in two locations and is home to 12 buildings and three leased spaces.[107] Into the 2000s, Grand Valley State University expanded its medical education programs into Medical Mile, constructing various facilities such as the Cook-DeVos Center for Health Sciences in 2003.[108] The university expanded across I-196 from the Medical Mile into the Belknap Lookout neighborhood in the 2010s, constructing the Raleigh Finkelstein Hall to assist with medical and nursing studies.[109]

Ferris State University has a growing campus downtown, including the Applied Technology Center (operated with GRCC) and the Kendall College of Art and Design, a formerly private institution that now is part of Ferris. Ferris State also has a branch of the College of Pharmacy downtown on the medical mile. Western Michigan University has a long-standing graduate program in the city, with facilities downtown, and in the southeast. The Van Andel Institute, a cancer research institute established in 1996, also resides on the medical mile; the institute established a graduate school in 2005 to train Ph.D. students in cellular, genetic, and molecular biology.

Grand Rapids is home to the Secchia Center medical education building, a $90 million, seven-story, 180,000-square-foot (17,000 m2) facility, at Michigan Street and Division Avenue, part of the Grand Rapids Medical Mile. The building is home to the Grand Rapids Campus of the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine. This campus trains medical students through all four years of their medical education. The state-of-the-art facility includes clinical examination rooms, simulation suites, classrooms, offices, and student areas.[110]

Culture

In 1969, Alexander Calder's abstract sculpture, La Grande Vitesse, which translates from French as "the great swiftness" or more loosely as "grand rapids," was installed downtown on Vandenberg Plaza, the redesigned setting of Grand Rapids City Hall.[111] It was the first work of public art in the United States funded by the National Endowment for the Arts.[112] The sculpture is informally known as "the Calder", and since its installation the city has hosted an annual Festival of the Arts in the area surrounding the sculpture, now known informally as "Calder Plaza".[111][113] During the first weekend in June, several blocks of downtown surrounding the Calder stabile in Vandenberg Plaza are closed to traffic. The festival features several stages with free live performances, food booths selling a variety of ethnic cuisine, art demonstrations and sales, and other arts-related activities. Organizers bill it as the largest all-volunteer arts festival in the United States. Vandenberg Plaza also hosts various ethnic festivals throughout the summer season.

Each October, the city celebrates Polish culture, historically based on the West side of town, with Pulaski Days.

In 1973, Grand Rapids hosted Sculpture off the Pedestal, an outdoor exhibition of public sculpture, which assembled works by 13 world-renowned artists, including Mark di Suvero, John Henry, Kenneth Snelson, Robert Morris, John Mason, Lyman Kipp, and Stephen Antonakos, in a single, citywide celebration. Sculpture off the Pedestal was a public/private partnership, including financial support by the National Endowment for the Arts, educational support from the Michigan Council for the Arts, and in-kind contributions from individuals, business, and industry. Fund-raising events, volunteers, and locals housing artists contributed to the public character of the event.

From 1980 to 2015, Celebration on the Grand was held the weekend after Labor Day, featuring free concerts, fireworks display and food booths. 'Celebration on the Grand' is an event that celebrates life in the Grand River valley.

On November 10, 2004, the grand premiere of the film The Polar Express was held in Grand Rapids. It was adapted from the children's book by author and illustrator Chris Van Allsburg, who lives in the city. His main character in the book (and movie) also lives in Grand Rapids, and the movie was set in the city. The Meijer Gardens created a Polar Express display as part of their larger Christmas Around the World exhibit.

In mid-2004, the Grand Rapids Art Museum (GRAM) began construction of a new, larger building for its collection; it opened in October 2007 at 101 Monroe Center NW. The new building site faces the sculpture Ecliptic, by Maya Lin, at Rosa Parks Circle. The museum was completed in 2007. It was the first new art museum to achieve gold-level LEED certification by the U.S. Green Building Council.

ArtPrize, the world's largest annual art competition determined by public voting, first took place in Grand Rapids from September 23 through October 10, 2009. This event was founded by Rick DeVos, grandson of Amway Corp. co-founder Richard DeVos, who offered $449,000 in cash prizes. A total of 1,262 artists exhibited their work for two weeks, and a total of 334,219 votes were cast. First prize, including a $250,000 cash prize, went to Brooklyn painter Ran Ortner.[114] ArtPrize 2010 was held September 22 through October 10, 2010, with work by 1,713 artists on display. The first prize was awarded to Grand Rapids artist Chris LaPorte.[115] The twelfth annual ArtPrize will be held from September 16 to October 3, 2021.

In 2012, Grand Rapids tied with Asheville, North Carolina for "Beer City USA." The competition was held by casting votes online for cities around the United States. Prominent breweries in the area such as B.O.B's Brewery, Brewery Vivant, Founders Brewing Company, Grand Rapids Brewing Co., Harmony Brewing, HopCat and Schmohz have created the culture necessary to win the award.[116] In 2013, Grand Rapids was the sole winner of "Beer City USA", taking the prize with more votes than those combined for the second-place Kalamazoo, Michigan, and the third-place Asheville, North Carolina.[117]

Tourism

Grand Rapids is the home of John Ball Zoological Garden, Belknap Hill, and the Gerald R. Ford Museum. He and former First Lady Betty Ford were buried on the site. Significant buildings in the downtown include the DeVos Place Convention Center, Van Andel Arena, the Amway Grand Plaza Hotel, and the JW Marriott Hotel. The Urban Institute for Contemporary Arts is downtown, and houses art exhibits, a movie theater, and the urban clay studio.[118]

Along the Grand River are reconstructed earthwork burial mounds, which were constructed by the prehistoric Hopewell tribe; a fish ladder, and a riverwalk.

Grand Rapids is home to the Van Andel Museum Center. Founded in 1854, it is among the oldest history museums in the United States. The museum's sites include its main building, constructed in 1994 on the west bank of the Grand River (home to the Roger B. Chaffee Planetarium); the Voigt House Victorian Museum, and the City Archives and Records Center. The latter held the museum and planetarium before 1994. Since the late 20th century, the museum has hosted notable exhibitions, including one on the Dead Sea Scrolls, and The Quest for Immortality: the Treasures of Ancient Egypt. A non-profit institution, it is owned and managed by the Public Museum of Grand Rapids Foundation.

Heritage Hill, a neighborhood directly east of downtown, is one of the largest urban historic districts in the country. The first "neighborhood" of Grand Rapids, its 1,300 homes date from 1848 and represent more than 60 architectural styles. Of particular significance is the Meyer May House, a Prairie-style home Frank Lloyd Wright designed in 1908.[119] It was commissioned by local merchant Meyer May, who operated a men's clothing store (May's of Michigan).

The house is now owned and operated by Steelcase Corporation. Steelcase manufactured the furniture for the Johnson Wax Building in Racine, Wisconsin, which was also designed by Wright and is recognized as a landmark building. Because of those ties, Steelcase purchased and restored the property in the 1980s. The restoration has been heralded as one of the most accurate and complete of any Wright restoration. The home is used by Steelcase for special events and is open to the public for tours.

Grand Rapids is home to many theaters and stages, including the newly reconstructed Civic Theatre (also known as the Meijer Majestic), the city's largest theater; DeVos Hall, and the convertible Van Andel Arena. Further east of downtown is the historic Wealthy Theatre. Studio 28, the first megaplex in the United States, is in Grand Rapids; it reopened in 1988 with a seating capacity of 6,000.[120] The megaplex ceased operations on November 23, 2008.[121][122] The Grand Rapids company also owns many theaters around West Michigan.

In Grand Rapids Township, the Frederik Meijer Gardens and Sculpture Park combine 125 acres (1 km2) of world-class botanical gardens and artwork from such American sculptors as Mark di Suvero and Alexander Calder, and French artists Edgar Degas and Auguste Rodin. The Gardens' amphitheater plays host to numerous concerts each summer, featuring such acts as Jonny Lang, The Pointer Sisters, Lyle Lovett, Cowboy Junkies, and B.B. King. The Gardens were mentioned in Patricia Schultz's book 1,000 Places to See Before You Die.[123]

In 2014, Grand Rapids was named the No. 1 U.S. travel destination by Lonely Planet.[124] In 2016, The New York Times ranked Grand Rapids 20th on the 52 Places to Go in 2016 list.[125]

Grand Rapids' prominent craft beer culture has continued to garner the city national and international recognition in recent years, making it a destination for increasing numbers of tourists. In 2019, CNN Travel named Grand Rapids one of the world's "15 Best Beer Cities." The article made special mention of Founders Brewing Company, Brewery Vivant, and The Mitten Brewing Company on the city's West Side.[126]

Entertainment and performing arts

Grand Rapids has several popular concert venues in which numerous bands have performed, including 20 Monroe Live, the DAAC, the Intersection, DeVos Performance Hall, Van Andel Arena, Royce Auditorium in St. Cecilia Music Center, Forest Hills Fine Arts Center, The Pyramid Scheme, and the Deltaplex.

The Schubert Male Chorus of Grand Rapids was founded by Henry C. Post on November 19, 1883; the chorus continues to perform a variety of music.

The Grand Rapids Symphony, founded in 1930, is the largest performing arts organization in Grand Rapids with a roster of about 50 full-time and 30 part-time musicians. In addition to its own concert series, the orchestra under music director Marcelo Lehninger accompanies productions by Grand Rapids Ballet and Opera Grand Rapids, presenting more than 400 performances a year.[127]

The Grand Rapids Barbershop Chapter Great Lakes Chorus is an all-male a cappella barbershop harmony chorus, including quartets. It is one of the oldest chapters in the Barbershop Harmony Society (formally known as the Society for the Preservation and Encouragement of Barber Shop Quartet Singing in America, or SPEBSQSA). The Grand Rapids chapter organized on November 1, 1939, for quartet singers; it is credited for holding the first society-sanctioned quartet contest in the "Michigan District" (now Pioneer District) in March 1941. In 1944 the Grand Rapids Chapter is credited with having the first International Quartet champions, "The Harmony Halls." In 1947 the Great Lakes Chorus (then called the Grand Rapids Chorus) was founded. In 1953 the first International Chorus Competition was held, and the Great Lakes Chorus took First Place, the first "International Convention Championship Chorus," under the direction of Robert Weaver.[128] The chorus is still very active as a non-profit singing for community, competition, and contracted performances.

Grand Rapids Ballet Company was founded in 1971 and is one of Michigan's few professional ballet companies.[129] The ballet company is on Ellsworth Avenue in the Heartside neighborhood, where it moved in 2000. In 2007, it expanded its facility by adding the LEED-certified Peter Wege Theater.[129]

Opera Grand Rapids, founded in 1966, is the state's longest-running professional company.[130] In February 2010, the opera moved into a new facility in the Fulton Heights neighborhood.[131]

A January 21, 2011 Newsweek article listed Grand Rapids as a "dying city" because of its drop in population from 2000 to 2009.[132] Director Rob Bliss and producer Scott Seven filmed a vigorous, 5,000-person community response titled The Grand Rapids LipDub, released May 26, which was the first-ever citywide lip dub video; film critic Roger Ebert described it as "the greatest music video ever made".[133] The video held the world record for largest lip dub for two years and has amassed over 5 million views on YouTube; PRNewswire awarded its producers the "Earnie Award" for Best Use of Video in Social Media.[134]

Grand Rapids is also home to Art Prize, the largest art exposition in the U.S. Art Prize began in 2009 with the over 200,000 visitors and has since doubled the number of visitors it receives each year. Artprize receives many international visitors each year and is still growing with over 1,500 entries from 48 countries across 200+ venues in 2015.[135][136]

Sports

.jpg.webp)

Grand Rapids is home to several professional and semi-professional sports teams. The West Michigan Whitecaps of the Midwest League play at LMCU Ballpark and won the Championship Series six times (1996, 1998, 2004, 2006, 2007, 2015) and had the best regular-season record six times (1997, 1998, 2000, 2006, 2007, 2017). The Whitecaps are the Class High A affiliate of the Detroit Tigers. The Grand Rapids Griffins, an ice hockey team of the American Hockey League, play at the Van Andel Arena and won the IHL Fred A. Huber Trophy in 2001, and were AHL Calder Cup Champions in the 2012–2013 and 2016–2017 seasons. The Griffins are the AHL affiliate of the Detroit Red Wings. Grand Rapids Gold is an NBA G League basketball team that plays at the Van Andel Arena, with the team being an affiliate of the Denver Nuggets. Midwest United FC is a United Women's Soccer soccer club that plays at Aquinas College and won a national championship in the 2017 season.

Former professional sports teams include the Grand Rapids Danger, Grand Rapids Dragonfish, Grand Rapids Cyclones, Grand Rapids Rampage, Grand Rapids Hoops (Grand Rapids Mackers), Grand Rapids Flight, Grand Rapids Owls (1977–80), Grand Rapids Rockets, and Grand Rapids Chicks, Grand Rapids Blazers and the Grand Rapids Shamrocks. The Grand Rapids Blazers won the United Football League Championship in 1961.

Each year the Amway River Bank Run is held in downtown Grand Rapids. It draws participants from around the world; in 2010 there were over 22,000 participants. The Grand Rapids Marathon is held in downtown Grand Rapids in mid-October, usually on the same weekend as the Detroit Marathon. Special Olympics Michigan launched a campaign in 2021 to build a publicly-funded $20 million facility called the Unified Sports and Inclusion Center that is destined to be the largest Special Olympics facility in the world.[137]

Amateur sporting organizations in the area include Grand Raggidy Roller Derby WFTDA league, Grand Rapids Rowing Association,[138] Grand Rapids Rugby Club,[139] and the West Michigan Wheelchair Sports Association.[140] The West Michigan Sports Commission was the host organizing committee for the inaugural State Games of Michigan, held in Grand Rapids from June 25 to 27, 2010.[141][142]

Media

The Grand Rapids Press is a daily newspaper, while Advance Newspapers publishes a group of weekly papers that provide community-based news. Gemini Media is a niche, regional publishing company that produces the weekly newspaper Grand Rapids Business Journal; the magazines Grand Rapids Magazine, Grand Rapids Family and Michigan Blue; and several other quarterly and annual business-to-business publications. Two free monthly entertainment guides are distributed: REVUE,[143] which covers music and the arts, and RECOIL, which covers music and offers Onion-style satire. The Rapidian is an online-based citizen journalism project funded by grants from the Knight Foundation and local community foundations.[144] It is reprinted or cited by other local media outlets.[145]

Grand Rapids, combined with nearby Kalamazoo and Battle Creek, was ranked in 2019 as the 45th-largest television market in the U.S. by Nielsen Media Research.[146] The market is served by stations affiliated with major American networks including: WLLA (channel 64, Independent), WOOD-TV (channel 8, NBC), WOTV (channel 41, ABC), WZZM-TV (channel 13, ABC), WXMI (channel 17, Fox), WXSP-CD (channel 15, MyNetworkTV) and Kalamazoo-based WWMT (channel 3, CBS), along with surrounding stations based from Muskegon and Battle Creek. WGVU-TV is the area's PBS member station.

The Grand Rapids area is served by 16 AM radio stations and 28 FM stations.[147]

Public safety

Law enforcement

The Grand Rapids Police Department is tasked with law enforcement in Grand Rapids and has been serving the city since 1871.[148] Since 2001, the police department has been located at a renovated Herpolsheimer's department store at 1 Monroe Center NW.[149][150] In 2011, the Kent County Dispatch Authority consolidated the dispatch operations of the Grand Rapids Police Department and the Wyoming Police Department, the public safety department of Grand Rapids' suburb, Wyoming.[151]

On April 4, 2022, Officer Christopher Schurr of the Grand Rapids Police Department killed a 26-year-old black man, Patrick Lyoya, during a traffic stop.[152] The department later released footage of the killing on April 13, spawning a demonstration with hundreds of protestors demonstrating throughout the city.[153] Lyoya was a refugee from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, who had arrived in Michigan with his family in 2014.[154]

Crime

The homicide rate in Grand Rapids was at its highest in the early 1990s, with the highest number of homicides being 34 in 1993.[155][156] The average annual number of homicides in Grand Rapids between 2010 and 2020 was 12.4.[157] In 2014, Grand Rapids experienced the lowest homicide rate in fifty years, with six murders occurring that year.[158] By the end of the 2010s, the number of homicides began to increase, with a total of 17 occurring in 2019.[157]

In 2020 Grand Rapids had 38 homicides. This is the highest number ever recorded in Grand Rapids.[159] In recent years, Grand Rapids has seen an increase in auto thefts; in both 2020 and 2021 there were over 800 cars stolen in Grand Rapids.[160]

Government and politics

Under Michigan law, Grand Rapids is a home rule city and adopted a city charter in 1916 providing for the council-manager form of municipal government.[161][162] Under this system, the political responsibilities are divided between an elected City Commission, an elected City Comptroller and a hired full-time City Manager. Two part-time Commissioners are elected to four-year terms from each of three wards, with half of these seats up for election every two years. The races—held in odd-numbered years—are formally non-partisan, although the party and other political affiliations of candidates do sometimes come up during the campaign period. The Commission sets policy for the city, and is responsible for hiring the City Manager and other appointed officials. The elected City Comptroller verifies financial policies and budgets are followed and prepares the annual financial report.[161] The city levies an income tax of 1.5 percent on residents and 0.75 percent on nonresidents.[163]

Mayor

The part-time mayor is elected every four years by the city at large and serves as chair of the commission, with a vote equal to a commissioner.[161] The mayor, although a weak mayor per the system of government, spends approximately 20 hours per week on mayoral activities from serving on various oversight boards and attending conferences.[162]

Three-term mayor John H. Logie declined to run for re-election in 2003. Logie felt the position should be made full-time, but to avoid the question becoming a referendum on whether he should hold the job full-time, he announced he would not run for re-election.[164] The voters kept the position part-time, and George Heartwell succeeded him in January 2004.[165] In 2014 a narrowly-approved ballot initiative imposed a limit of two terms on the mayor and city commissioners, preventing Heartwell from seeking a fourth term.[166] Commissioner Rosalynn Bliss, also unable to run for another term in that position, was then elected mayor, receiving a clear majority in the August 2015 primary.

Politics

The city proper and inner-suburbs favor the Democratic Party, while outer-suburbs of Grand Rapids tend to support the Republican Party.[167][168]

Traditionally, Grand Rapids supported the Republican Party.[167][168] The city is the center of the 3rd Congressional District, represented by Republican Peter Meijer.[169] Former President Gerald Ford represented the district (then numbered as the 5th) from 1949 to 1973 and is buried on the grounds of his Presidential Museum in Grand Rapids. The city and its suburbs are home to several major donors to the national Republican Party, including the DeVos family and Peter Secchia, former Ambassador to Italy.

Both representatives in the Michigan State House of Representatives are Democrats, and the city's State Senate seat was taken by a Democrat in 2018. In the eight most recent presidential elections, Democratic candidates Bill Clinton, Al Gore, John Kerry, Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Joe Biden won a majority or plurality of votes in the city of Grand Rapids. The last Republican candidate for president to carry the city was George H. W. Bush in 1988.[170]

Transportation

Roadways

The first improved road into the city was completed in 1855. This road was a private, toll plank road built from Kalamazoo through Wayland. It was a primary route for freight and passengers until about 1868. This road connected to other regions via the Michigan Central Railroad at Kalamazoo.

Railroad

The Detroit and Milwaukee Railroad, which began service in 1858, was the first railroad into the city. In 1869, the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway connected to the city. The Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad began passenger and freight service to Cedar Springs, Michigan, on December 25, 1867, and to Fort Wayne, Indiana, in 1870. This railroad expanded service to Muskegon in 1886. The Grand Rapids, Newaygo and Lake Shore Railroad completed a line to White Cloud in 1875. In 1888 the Detroit, Lansing and Northern Railroad connected with Grand Rapids. Until the mid-1950s Grand Rapids Union Station was a hub for passenger trains from different directions in Michigan and beyond.

Street railways

Early railway transportation in Grand Rapids began in 1865, to connect with the Detroit–Milwaukee train station. Over time, several independent lines were opened and operated as well. The railways were combined into one company, Street and Railway Company, in 1883. Competition within the city soon sprang up. In February 1885, the Valley City Street and Cable Company was formalized and became operational in 1888. Valley City Street and Cable Company brought the first cable cars to Grand Rapids in order to bring transportation service to Michigan and Lyon street hills. The lack of a connection between the two companies caused confusion among riders. This led to the unifying of the two companies in 1890 under the name Consolidated Street Railway Company.

Under the Consolidated Street Railway Company, new electric lines were introduced. After struggling for ten years, Consolidated Street Railway Company was bought out in 1900 by E. W. Clark Company of Philadelphia and was renamed the Grand Rapids Railway Company. The change brought many improvements to the railway service, including heavier tracks, double cars and expanded service which bolstered a healthy ridership that would last for many years. In 1925, the Grand Rapids Railway Company suffered a serious setback when a fire destroyed 57 streetcars. The process of rebuilding brought to light a lack of streetcar improvements within the industry. With Grand Rapids at the forefront, industry-wide improvements were made to streetcar design and the new modern streetcars were introduced into the city in 1927.

The onset of the Great Depression in 1929 crippled the streetcar industry in Grand Rapids. Streetcars were phased out in favor of buses. The process was hastened by a city-wide street widening, which would have required a resetting of the tracks. By 1934 buses had taken over all of the systems, and in 1935 the last streetcar in Grand Rapids made its final run. The Grand Rapids Railway Company sold its assets and re-consolidated as Grand Rapids Motor Coach Company in 1937 after declaring bankruptcy. It retained some interest in Ramona Park until their closure in 1950.[171][172][173][174][175]

Air transportation

Grand Rapids was home to one of the first regularly scheduled passenger airlines in the United States when Stout Air Services began flights from the old Grand Rapids airport to Detroit (Ford Airport in Dearborn, Michigan), on July 31, 1926.[176]

Major highways

![]() I-96 runs along the northern and northeastern sides of the city, linking with Muskegon to the west and Lansing and Detroit, Michigan, to the east

I-96 runs along the northern and northeastern sides of the city, linking with Muskegon to the west and Lansing and Detroit, Michigan, to the east

![]() I-196, also named the Gerald R. Ford Freeway, runs east–west through the city, connecting to I-96 just east of Grand Rapids and I-94 in Benton Township

I-196, also named the Gerald R. Ford Freeway, runs east–west through the city, connecting to I-96 just east of Grand Rapids and I-94 in Benton Township

![]() I-296, an unsigned route running concurrently with US 131 between I-96 and I-196

I-296, an unsigned route running concurrently with US 131 between I-96 and I-196

![]() US 131 runs north–south through the city, linking with Kalamazoo to the south and Cadillac to the north

US 131 runs north–south through the city, linking with Kalamazoo to the south and Cadillac to the north

![]() M-6 is the Paul B. Henry Freeway running along the south side connecting I-96 and I-196

M-6 is the Paul B. Henry Freeway running along the south side connecting I-96 and I-196

![]() M-11 runs along Ironwood/Remembrance Road, Wilson Avenue, and 28th Street

M-11 runs along Ironwood/Remembrance Road, Wilson Avenue, and 28th Street

![]() M-21 is Fulton Street to the east

M-21 is Fulton Street to the east

![]() M-37 follows Alpine Avenue to the north, I-96, East Beltline Avenue and Broadmoor Avenue to the south

M-37 follows Alpine Avenue to the north, I-96, East Beltline Avenue and Broadmoor Avenue to the south

![]() M-44 is East Beltline north of I-96

M-44 is East Beltline north of I-96

![]()

![]() Conn. M-44 runs along Plainfield Avenue

Conn. M-44 runs along Plainfield Avenue

![]() M-45 follows Lake Michigan Drive west toward Allendale and Lake Michigan

M-45 follows Lake Michigan Drive west toward Allendale and Lake Michigan

![]() A-45 is Old US 131 south of 28th Street

A-45 is Old US 131 south of 28th Street

Bus

- The Interurban Transit Partnership, which brands itself as The Rapid, provides public bus transportation. Transportation is also provided by the DASH buses: the "Downtown Area Shuttle." These provide transportation to and from the parking lots in the city of Grand Rapids to designated loading and unloading spots around the city. The area's Greyhound Bus terminal is integrated into the Central Station of the Rapid, simplifying transfers between Greyhound and local buses. In August 2014, the SilverLine opened, Michigan's first bus rapid transit line, an express bus line designed to function like a light rail system.[177] There are plans in the works to add more express routes, secondary stations, a streetcar and dedicated (exclusive) highway lanes.[178]

- Indian Trails provides daily intercity bus service of varying frequencies between Grand Rapids and Petoskey, Michigan,[179] between Grand Rapids and Benton Harbor, Michigan,[180] and between Grand Rapids and Kalamazoo, Michigan[181] with intermediate stops.

Air

Commercial air service to Grand Rapids is provided by Gerald R. Ford International Airport (GRR). Eight passenger airlines and two cargo airlines operate over 150 daily flights to 34 nonstop destinations across the United States. International service was formerly operated to Toronto, Canada by Air Canada Express. The airport was formerly named Kent County International Airport before gaining its present name in 1999.

The first regularly scheduled air service in the United States was between Grand Rapids and Detroit (actually Dearborn's Ford Airport) on a Ford-Stout monoplane named Miss Grand Rapids, which began on July 26, 1926. Delta Air Lines continues to operate this route today to their hub at Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport (DTW).

Sister cities

Grand Rapids' sister cities are:[184]

Bielsko-Biała, Poland

Bielsko-Biała, Poland Ga East District, Ghana

Ga East District, Ghana Ga West District, Ghana

Ga West District, Ghana Gangnam (Seoul), South Korea

Gangnam (Seoul), South Korea Ōmihachiman, Japan