Gray whale

The gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus),[1] also known as the grey whale,[5] gray back whale, Pacific gray whale, Korean gray whale, or California gray whale,[6] is a baleen whale that migrates between feeding and breeding grounds yearly. It reaches a length of 14.9 meters (49 ft), a weight of up to 41 tonnes (90,000 lb) and lives between 55 and 70 years, although one female was estimated to be 75–80 years of age.[7][8] The common name of the whale comes from the gray patches and white mottling on its dark skin.[9] Gray whales were once called devil fish because of their fighting behavior when hunted.[10] The gray whale is the sole living species in the genus Eschrichtius. It was formerly thought to be the sole living genus in the family Eschrichtiidae, but more recent evidence classifies members of that family in the family Balaenopteridae. This mammal is descended from filter-feeding whales that appeared during the Neogene.

| Gray whale[1] Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Gray whale spy-hopping next to calf | |

| |

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Balaenopteridae |

| Genus: | Eschrichtius |

| Species: | E. robustus |

| Binomial name | |

| Eschrichtius robustus Lilljeborg, 1861 | |

| |

| Gray whale range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The gray whale is distributed in an eastern North Pacific (North American), and an endangered western North Pacific (Asian), population. North Atlantic populations were extirpated (perhaps by whaling) on the European coast before 500 CE, and on the American coast around the late 17th to early 18th centuries.[11] However, in the 2010s there have been a number of sightings of gray whales in the Mediterranean Sea and even off Southern hemisphere Atlantic coasts.

Taxonomy

The gray whale is traditionally placed as the only living species in its genus and family, Eschrichtius and Eschrichtiidae,[12] but an extinct species was discovered and placed in the genus in 2017, the Akishima whale (E. akishimaensis).[13] Some recent studies place gray whales as being outside the rorqual clade, but as the closest relatives to the rorquals.[14] But other recent DNA analyses have suggested that certain rorquals of the family Balaenopteridae, such as the humpback whale, Megaptera novaeangliae, and fin whale, Balaenoptera physalus, are more closely related to the gray whale than they are to some other rorquals, such as the minke whales.[15][16][17][18] The American Society of Mammalogists has followed this classification.[19]

John Edward Gray placed it in its own genus in 1865, naming it in honour of physician and zoologist Daniel Frederik Eschricht.[20] The common name of the whale comes from its coloration. The subfossil remains of now extinct gray whales from the Atlantic coasts of England and Sweden were used by Gray to make the first scientific description of a species then surviving only in Pacific waters.[21] The living Pacific species was described by Cope as Rhachianectes glaucus in 1869.[22] Skeletal comparisons showed the Pacific species to be identical to the Atlantic remains in the 1930s, and Gray's naming has been generally accepted since.[23][24] Although identity between the Atlantic and Pacific populations cannot be proven by anatomical data, its skeleton is distinctive and easy to distinguish from that of all other living whales.[25]

Many other names have been ascribed to the gray whale, including desert whale,[26] devilfish, gray back, mussel digger and rip sack.[27] The name Eschrichtius gibbosus is sometimes seen; this is dependent on the acceptance of a 1777 description by Erxleben.[28]

Taxonomic history

A number of 18th century authors[29] described the gray whale as Balaena gibbosa, the "whale with six bosses", apparently based on a brief note by Dudley 1725:[30]

The Scrag Whale is near a kin to the Fin-back, but instead of a Fin upon his Back, the Ridge of the Afterpart of his Back is cragged with half a Dozen Knobs or Nuckles; he is nearest the right Whale in Figure and for Quantity of Oil; his Bone is white, but won't split.[31]

The gray whale was first described as a distinct species by Lilljeborg 1861 based on a subfossil found in the brackish Baltic Sea, apparently a specimen from the now extinct north Atlantic population. Lilljeborg, however, identified it as "Balaenoptera robusta", a species of rorqual.[32] Gray 1864 realized that the rib and scapula of the specimen was different from those of any known rorquals, and therefore erected a new genus for it, Eschrichtius.[33] Van Beneden & Gervais 1868 were convinced that the bones described by Lilljeborg could not belong to a living species but that they were similar to fossils that Van Beneden had described from the harbour of Antwerp (most of his named species are now considered nomina dubia) and therefore named the gray whale Plesiocetus robustus, reducing Lilljeborg's and Gray's names to synonyms.[34]

Scammon 1869 produced one of the earliest descriptions of living Pacific gray whales, and notwithstanding that he was among the whalers who nearly drove them to extinction in the lagoons of the Baja California Peninsula, they were and still are associated with him and his description of the species.[35] At this time, however, the extinct Atlantic population was considered a separate species (Eschrischtius robustus) from the living Pacific population (Rhachianectes glaucus).[36]

Things got increasingly confused as 19th century scientists introduced new species at an alarming rate (e.g. Eschrichtius pusillus, E. expansus, E. priscus, E. mysticetoides), often based on fragmentary specimens, and taxonomists started to use several generic and specific names interchangeably and not always correctly (e.g. Agalephus gobbosus, Balaenoptera robustus, Agalephus gibbosus). Things got even worse in the 1930s when it was finally realised that the extinct Atlantic population was the same species as the extant Pacific population, and the new combination Eschrichtius gibbosus was proposed.[30]

Description

The gray whale has a dark slate-gray color and is covered by characteristic gray-white patterns, scars left by parasites which drop off in its cold feeding grounds. Individual whales are typically identified using photographs of their dorsal surface and matching the scars and patches associated with parasites that have fallen off the whale or are still attached. They have two blowholes on top of their head, which can create a distinctive heart-shaped blow[37] at the surface in calm wind conditions.

Gray whales measure from 4.9 m (16 ft) in length for newborns to 13–15 m (43–49 ft) for adults (females tend to be slightly larger than adult males). Newborns are a darker gray to black in color. A mature gray whale can reach 40 t (44 short tons), with a typical range of 15–33 t (17–36 short tons), making them the ninth largest sized species of cetacean.[38]

Notable features that distinguish the gray whale from other mysticetes include its baleen that is variously described as cream, off-white, or blond in color and is unusually short. Small depressions on the upper jaw each contain a lone stiff hair, but are only visible on close inspection. Its head's ventral surface lacks the numerous prominent furrows of the related rorquals, instead bearing two to five shallow furrows on the throat's underside. The gray whale also lacks a dorsal fin, instead bearing 6 to 12 dorsal crenulations ("knuckles"), which are raised bumps on the midline of its rear quarter, leading to the flukes. This is known as the dorsal ridge. The tail itself is 3–3.5 m (10–11 ft) across and deeply notched at the center while its edges taper to a point.

Pacific groups

The two populations of Pacific gray whales (east and west) are morphologically and phylogenically different. Other than DNA structures, differences in proportions of several body parts and body colors including skeletal features, and length ratios of flippers and baleen plates have been confirmed between Eastern and Western populations, and some claims that the original eastern and western groups could have been much more distinct than previously thought, enough to be counted as subspecies.[39][40] Since the original Asian and Atlantic populations have become extinct, it is difficult to determine the unique features among whales in these stocks. However, there have been observations of some whales showing distinctive, blackish body colors in recent years.[41] This corresponds with the DNA analysis of last recorded stranding in China.[42] Differences were also observed between Korean and Chinese specimens.[40]

Populations

North Pacific

.jpg.webp)

Two Pacific Ocean populations are known to exist: one population that is very low, whose migratory route is presumed to be between the Sea of Okhotsk and southern Korea, and a larger one with a population of about 27,000 individuals in the eastern Pacific traveling between the waters off northernmost Alaska and Baja California Sur.[43] Mothers make this journey accompanied by their calves, usually hugging the shore in shallow kelp beds, and fight viciously to protect their young if they are attacked, earning gray whales the moniker, devil fish.[44]

The western population has had a very slow growth rate despite heavy conservation action over the years, likely due to their very slow reproduction rate.[45] The state of the population hit an all-time low in 2010, when no new reproductive females were recorded, resulting in a minimum of 26 reproductive females being observed since 1995.[46] Even a very small number of additional annual female deaths will cause the subpopulation to decline.[47] However, as of 2018, evidence has indicated that the western population is markedly increasing in number, especially off Sakhalin Island. Following this, the IUCN downlisted the population's conservation status from critically endangered to endangered.[48][45]

North Atlantic

The gray whale became extinct in the North Atlantic in the 18th century.[49] Other than speculations, large portions of historical characteristic of migration and distribution are unclear such as locations of calving grounds and existences of resident groups.

They had been seasonal migrants to coastal waters of both sides of Atlantic, including the Baltic Sea,[50][51] Wadden Sea, the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the Bay of Fundy, Hudson Bay (possibly),[52] and Pamlico Sound.[53] Radiocarbon dating of subfossil or fossil European (Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom) coastal remains confirms this, with whaling the possible cause.[25] Remains dating from the Roman epoch were found in the Mediterranean during excavation of the antique harbor of Lattara near Montpellier, France, in 1997, raising the question of whether Atlantic gray whales migrated up and down the coast of Europe from Wadden Sea to calve in the Mediterranean.[54][55] A 2018 study utilizing ancient DNA barcoding and collagen peptide matrix fingerprinting confirmed that Roman era whale bones east of the Strait of Gibraltar were gray whales (and North Atlantic right whales), confirming that gray whales once ranged into the Mediterranean.[56] Similarly, radiocarbon dating of American east coastal subfossil remains confirm that gray whales existed there at least through the 17th century. This population ranged at least from Southampton, New York, to Jupiter Island, Florida, the latest from 1675.[24] In his 1835 history of Nantucket Island, Obed Macy wrote that in the early pre-1672 colony a whale of the kind called "scragg" entered the harbor and was pursued and killed by the settlers.[57] A. B. Van Deinse points out that the "scrag whale", described by P. Dudley in 1725 as one of the species hunted by the early New England whalers, was almost certainly the gray whale.[58][59]

During the 2010s there have been rare sightings of gray whales in the North Atlantic Ocean or the connecting Mediterranean Sea, including one off the coast of Israel and one off the coast of Namibia.[60][61] These apparently were migrants from the North Pacific population through the Arctic Ocean.[60][61] A 2015 study of DNA from subfossil gray whales indicated that this may not be a historically unique event.[60][61][62] That study suggested that over the past 100,000 years there have been several migrations of gray whales between the Pacific and Atlantic, with the most recent large scale migration of this sort occurring about 5000 years ago.[60][61][62] These migrations corresponded to times of relatively high temperatures in the Arctic Ocean.[60][61][62] In 2021, one individual was seen at Rabat, Morocco,[63] followed by sightings at Algeria[64] and Italy.[65]

Prewhaling abundance

Researchers[66] used a genetic approach to estimate pre-whaling abundance based on samples from 42 California gray whales, and reported DNA variability at 10 genetic loci consistent with a population size of 76,000–118,000 individuals, three to five times larger than the average census size as measured through 2007. NOAA has collected surveys of gray whale population since at least the 1960s.[67] They state that "the most recent population estimate [from 2007] was approximately 19,000 whales, with a high probability (88%) that the population is at 'optimum sustainable population' size, as defined by the Marine Mammal Protection Act. They speculate that the ocean ecosystem has likely changed since the prewhaling era, making a return to prewhaling numbers infeasible.[68] Factors limiting or threatening current population levels include ship strikes, entanglement in fishing gear, and changes in sea-ice coverage associated with climate change.[69]

Integration and recolonization

Several whales seen off Sakhalin and on Kamchatka Peninsula are confirmed to migrate towards eastern side of Pacific and join the larger eastern population. In January 2011, a gray whale that had been tagged in the western population was tracked as far east as the eastern population range off the coast of British Columbia.[70] Recent findings from either stranded or entangled specimens indicate that the original western population have become functionally extinct and possibly all the whales appeared on Japanese and Chinese coasts in modern times are vagrants or re-colonizers from the eastern population.[39][42]

In mid-1980, there were three gray whale sightings in the eastern Beaufort Sea, placing them 585 kilometers (364 mi) further east than their known range at the time.[71] Recent increases in sightings are confirmed in Arctic areas of the historic range for Atlantic stocks, most notably on several locations in the Laptev Sea including the New Siberian Islands in the East Siberian Sea,[72] and around the marine mammal sanctuary[73] of the Franz Josef Land,[74] indicating possible earlier pioneers of re-colonizations. These whales were darker in body color than those whales seen in Sea of Okhotsk.[41] In May 2010, a gray whale was sighted off the Mediterranean shore of Israel.[75] It has been speculated that this whale crossed from the Pacific to the Atlantic via the Northwest Passage, since an alternative route around Cape Horn would not be contiguous to the whale's established territory. There has been gradual melting and recession of Arctic sea ice with extreme loss in 2007 rendering the Northwest Passage "fully navigable".[76] The same whale was sighted again on May 30, 2010, off the coast of Barcelona, Spain.[77]

In May 2013, a gray whale was sighted off Walvis Bay, Namibia. Scientists from the Namibian Dolphin Project confirmed the whale's identity and thus provides the only sighting of this species in the Southern Hemisphere. Photographic identification suggests that this is a different individual than the one spotted in the Mediterranean in 2010. As of July 2013, the Namibian whale was still being seen regularly.[78]

In March 2021, a gray whale was sighted near Rabat, the capital of Morocco.[63] In April, additional sightings were made off Algeria[64] and Italy.[65]

Genetic analysis of fossil and prefossil gray whale remains in the Atlantic Ocean suggests several waves of dispersal from the Pacific to the Atlantic related to successive periods of climactic warming – during the Pleistocene before the last glacial period and the early Holocene immediately following the opening of the Bering Strait. This information and the recent sightings of Pacific gray whales in the Atlantic, suggest that another range expansion to the Atlantic may be starting.[79]

Life history

Reproduction

_and_outline_of_head_showing_spouthole_in_1874_detail%252C_from-_The_marine_mammals_of_the_north-western_coast_of_North_America_(Plate_III)_BHL16226079_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Breeding behavior is complex and often involves three or more animals. Both male and female whales reach puberty between the ages of 6 and 12 with an average of eight to nine years.[80] Females show highly synchronized reproduction, undergoing oestrus in late November to early December.[81] During the breeding season, it is common for females to have several mates.[82] This single ovulation event is believed to coincide with the species' annual migration patterns, when births can occur in warmer waters.[82] Most females show biennial reproduction, although annual births have been reported.[81] Males also show seasonal changes, experiencing an increase in testes mass that correlates with the time females undergo oestrus.[82] Currently there are no accounts of twin births, although an instance of twins in utero has been reported.[81]

The gestation period for gray whales is approximately 13 1⁄2 months, with females giving birth every one to three years.[80][83] In the latter half of the pregnancy, the fetus experiences a rapid growth in length and mass. Similar to the narrow breeding season, most calves are born within a six-week time period in mid January.[80] The calf is born tail first, and measures about 14–16 ft in length, and a weight of 2,000 lbs.[8] Females lactate for approximately seven months following birth, at which point calves are weaned and maternal care begins to decrease.[80] The shallow lagoon waters in which gray whales reproduce are believed to protect the newborn from sharks and orcas.[84][44]

On 7 January 2014, a pair of newborn or aborted conjoined twin gray whale calves were found dead in the Laguna Ojo de Liebre (Scammon's Lagoon), off the west coast of Mexico. They were joined by their bellies.[85]

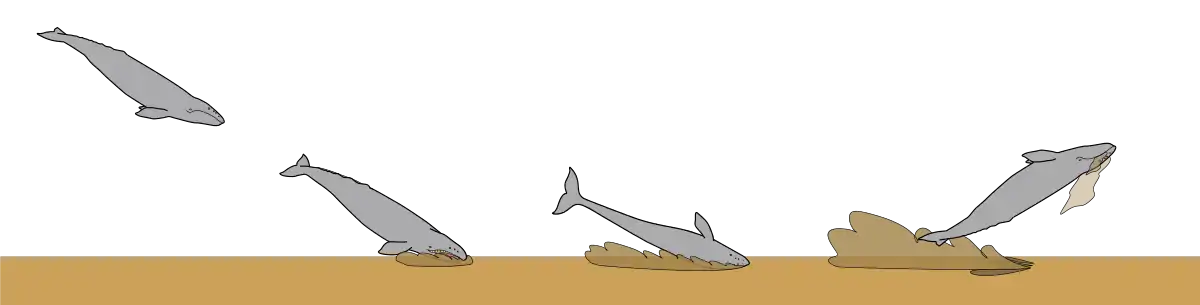

Feeding

The whale feeds mainly on benthic crustaceans, which it eats by turning on its side and scooping up sediments from the sea floor. This unique feeding selection makes gray whales one of the most strongly reliant on coastal waters among baleen whales. It is classified as a baleen whale and has baleen, or whalebone, which acts like a sieve, to capture small sea animals, including amphipods taken in along with sand, water and other material. Off Vancouver Island, gray whales commonly feed on shrimp-like mysids. When mysids are abundant gray whales are present in fairly large numbers. Despite mysids being a prey of choice, gray whales are opportunistic feeders and can easily switch from feeding planktonically to benthically. When gray whales feed planktonically, they roll onto their right side while their fluke remains above the surface, or they apply the skimming method seen in other baleen whales (skimming the surface with their mouth open). This skimming behavior mainly seems to be used when gray whales are feeding on crab larvae. Gray whales feed benthically, by diving to the ocean floor and rolling on to their side, (gray whales, like blue whales seem to favor rolling onto their right side) and suck up prey from the sea floor.[86] Gray whales seem to favor feeding planktonically in their feeding grounds, but benthically along their migration route in shallower water.[87] Mostly, the animal feeds in the northern waters during the summer; and opportunistically feeds during its migration, depending primarily on its extensive fat reserves. Another reason for this opportunistic feeding may be the result of population increases, resulting in the whales taking advantage of whatever prey is available, due to increased competition.[88] Feeding areas during migration seem to include the Gulf of California, Monterey Bay and Baja California Sur.[89] Calf gray whales drink 50–80 lb (23–36 kg) of their mothers' 53% fat milk per day.[90]

The main feeding habitat of the western Pacific subpopulation is the shallow (5–15 m (16–49 ft) depth) shelf off northeastern Sakhalin Island, particularly off the southern portion of Piltun Lagoon, where the main prey species appear to be amphipods and isopods.[91] In some years, the whales have also used an offshore feeding ground in 30–35 m (98–115 ft) depth southeast of Chayvo Bay, where benthic amphipods and cumaceans are the main prey species.[92] Some gray whales have also been seen off western Kamchatka, but to date all whales photographed there are also known from the Piltun area.[47][93]

Diagram of the gray whale seafloor feeding strategy

Migration

Predicted distribution models indicate that overall range in the last glacial period was broader or more southerly distributed, and inhabitations in waters where species presences lack in present situation, such as in southern hemisphere and south Asian waters and northern Indian Ocean were possible due to feasibility of the environment on those days.[79] Range expansions due to recoveries and re-colonization in the future is likely to be happen and the predicted range covers wider than that of today. The gray whale undergoes the longest migration of any mammal.[94]

Eastern Pacific population

Each October, as the northern ice pushes southward, small groups of eastern gray whales in the eastern Pacific start a two- to three-month, 8,000–11,000 km (5,000–6,800 mi) trip south. Beginning in the Bering and Chukchi seas and ending in the warm-water lagoons of Mexico's Baja California Peninsula and the southern Gulf of California, they travel along the west coast of Canada, the United States and Mexico.[95]

Traveling night and day, the gray whale averages approximately 120 km (75 mi) per day at an average speed of 8 km/h (5 mph). This round trip of 16,000–22,000 km (9,900–13,700 mi) is believed to be the longest annual migration of any mammal.[96] By mid-December to early January, the majority are usually found between Monterey and San Diego such as at Morro bay, often visible from shore.[94] The whale watching industry provides ecotourists and marine mammal enthusiasts the opportunity to see groups of gray whales as they migrate.

By late December to early January, eastern grays begin to arrive in the calving lagoons and bays on the west coast of Baja California Sur. The three most popular are San Ignacio, Magdalena Bay to the south, and, to the north, Laguna Ojo de Liebre (formerly known in English as Scammon's Lagoon after whaleman Charles Melville Scammon, who discovered the lagoons in the 1850s and hunted the grays).[97][98]

Gray whales once ranged into Sea of Cortez and Pacific coasts of continental Mexico south to the Islas Marías, Bahía de Banderas, and Nayarit/Jalisco, and there were two modern calving grounds in Sonora (Tojahui or Yavaros) and Sinaloa (Bahia Santa Maria, Bahia Navachiste, La Reforma, Bahia Altata) until being abandoned in 1980s.[99][100]

These first whales to arrive are usually pregnant mothers looking for the protection of the lagoons to bear their calves, along with single females seeking mates. By mid-February to mid-March, the bulk of the population has arrived in the lagoons, filling them with nursing, calving and mating gray whales.

Throughout February and March, the first to leave the lagoons are males and females without new calves. Pregnant females and nursing mothers with their newborns are the last to depart, leaving only when their calves are ready for the journey, which is usually from late March to mid-April. Often, a few mothers linger with their young calves well into May. Whale watching in Baja's lagoons is particularly popular because the whales often come close enough to boats for tourists to pet them.[101]

By late March or early April, the returning animals can be seen from Puget Sound to Canada.

Resident groups

A population of about 200 gray whales stay along the eastern Pacific coast from Canada to California throughout the summer, not making the farther trip to Alaskan waters. This summer resident group is known as the Pacific Coast feeding group.[102]

Any historical or current presence of similar groups of residents among the western population is currently unknown, however, whalers' logbooks and scientific observations indicate that possible year-round occurrences in Chinese waters and Yellow and Bohai basins were likely to be summering grounds.[103][104] Some of the better documented historical catches show that it was common for whales to stay for months in enclosed waters elsewhere, with known records in the Seto Inland Sea[105] and the Gulf of Tosa. Former feeding areas were once spread over large portions on mid-Honshu to northern Hokkaido, and at least whales were recorded for majority of annual seasons including wintering periods at least along east coasts of Korean Peninsula and Yamaguchi Prefecture.[104] Some recent observations indicate that historic presences of resident whales are possible: a group of two or three were observed feeding in Izu Ōshima in 1994 for almost a month,[106] two single individuals stayed in Ise Bay for almost two months in the 1980s and in 2012, the first confirmed living individuals in Japanese EEZ in the Sea of Japan and the first of living cow-calf pairs since the end of whaling stayed for about three weeks on the coastline of Teradomari in 2014.[107][108] One of the pair returned to the same coasts at the same time of the year in 2015 again.[109] Reviewing on other cases on different locations among Japanese coasts and islands observed during 2015 indicate that spatial or seasonal residencies regardless of being temporal or permanental staying once occurred throughout many parts of Japan or on other coastal Asia.[110]

Western population

The current western gray whale population summers in the Sea of Okhotsk, mainly off Piltun Bay region at the northeastern coast of Sakhalin Island (Russian Federation). There are also occasional sightings off the eastern coast of Kamchatka (Russian Federation) and in other coastal waters of the northern Okhotsk Sea.[91][111] Its migration routes and wintering grounds are poorly known, the only recent information being from occasional records on both the eastern and western coasts of Japan[112] and along the Chinese coast.[113] Gray whale had not been observed on Commander Islands until 2016.[114] The northwestern pacific population consists of approximately 300 individuals, based on photo identification collected off of Sakhalin Island and Kamchatka.[8]

The Sea of Japan was once thought not to have been a migration route, until several entanglements were recorded.[115] Any records of the species had not been confirmed since after 1921 on Kyushu.[104] However, there were numerous records of whales along the Genkai Sea off Yamaguchi Prefecture,[116] in Ine Bay in the Gulf of Wakasa, and in Tsushima. Gray whales, along with other species such as right whales and Baird's beaked whales, were common features off the north eastern coast of Hokkaido near Teshio, Ishikari Bay near Otaru, the Shakotan Peninsula, and islands in the La Pérouse Strait such as Rebun Island and Rishiri Island. These areas may also have included feeding grounds.[104] There are shallow, muddy areas favorable for feeding whales off Shiretoko, such as at Shibetsu, the Notsuke Peninsula, Cape Ochiishi on Nemuro Peninsula, Mutsu Bay,[117] along the Tottori Sand Dunes, in the Suou-nada Sea, and Ōmura Bay.

The historical calving grounds were unknown but might have been along southern Chinese coasts from Zhejiang and Fujian Province to Guangdong, especially south of Hailing Island[103] and to near Hong Kong. Possibilities include Daya Bay, Wailou Harbour on Leizhou Peninsula, and possibly as far south as Hainan Province and Guangxi, particularly around Hainan Island. These areas are at the southwestern end of the known range.[47][118] It is unknown whether the whales' normal range once reached further south, to the Gulf of Tonkin. In addition, the existence of historical calving ground on Taiwan and Penghu Islands (with some fossil records[119] and captures[120]), and any presence in other areas outside of the known ranges off Babuyan Islands in Philippines and coastal Vietnamese waters in Gulf of Tonkin are unknown. There is only one confirmed record of accidentally killing of the species in Vietnam, at Ngoc Vung Island off Ha Long Bay in 1994 and the skeleton is on exhibition at the Quang Ninh Provincial Historical Museum.[121][122] Gray whales are known to occur in Taiwan Strait even in recent years.[123]

It is also unknown whether any winter breeding grounds ever existed beyond Chinese coasts. For example, it is not known if the whales visited the southern coasts of the Korean Peninsula, adjacent to the Island of Jeju), Haiyang Island, the Gulf of Shanghai, or the Zhoushan Archipelago.[124] There is no evidence of historical presence in Japan south of Ōsumi Peninsula;[125] only one skeleton has been discovered in Miyazaki Prefecture.[126] Hideo Omura once considered the Seto Inland Sea to be a historical breeding ground, but only a handful of capture records support this idea, although migrations into the sea have been confirmed. Recent studies using genetics and acoustics, suggest that there are several wintering sites for western gray whales such as Mexico and the East China sea. However, their wintering ground habits in the western North Pacific are still poorly understood and additional research is needed.[105]

Recent migration in Asian waters

Even though South Korea put the most effort into conservation of the species among the Asian nations, there are no confirmed sightings along the Korean Peninsula or even in the Sea of Japan in recent years.

The last confirmed record in Korean waters was the sighting of a pair off Bangeojin, Ulsan in 1977.[127] Prior to this, the last was of catches of 5 animals[128] off Ulsan in 1966.[103] There was a possible sighting of a whale within the port of Samcheok in 2015.[129]

There had been 24 records along Chinese coasts including sighting, stranding, intended hunts, and bycatches since 1933.[42] The last report of occurrence of the species in Chinese waters was of a stranded semi adult female in the Bohai Sea in 1996,[103] and the only record in Chinese waters in the 21st century was of a fully-grown female being killed by entanglement in Pingtan, China in November, 2007.[123] DNA studies indicated that this individual might have originated from the eastern population rather than the western.[42]

Most notable observations of living whales after the 1980s were of 17 or 18 whales along Primorsky Krai in late October, 1989 (prior to this, a pair was reported swimming in the area in 1987), followed by the record of 14 whales in La Pérouse Strait on 13th, June in 1982 (in this strait, there was another sighting of a pair in October, 1987).[104] In 2011, presences of gray whales were acoustically detected among pelagic waters in East China Sea between Chinese and Japanese waters.[130]

Since the mid 1990s, almost all the confirmed records of living animals in Asian waters were from Japanese coasts.[131] There have been eight to fifteen sightings and stray records including unconfirmed sightings and re-sightings of the same individual, and one later killed by net-entanglement. The most notable of these observations are listed below:

- The feeding activities of a group of two or three whales that stayed around Izu Ōshima in 1994 for almost a month were recorded underwater[106] by several researchers and whale photographers.[132]

- A pair of thin juveniles were sighted off Kuroshio, Kōchi, a renowned town for whale-watching tourism of resident and sub-resident populations of Bryde's whales, in 1997.[133] This sighting was unusual because of the location on mid-latitude in summer time.

- Another pair of sub-adults were confirmed swimming near the mouth of Otani River in Suruga Bay in May, 2003.[117]

- A sub-adult whale that stayed in the Ise and Mikawa Bay for nearly two months in 2012[134][135][136] was later confirmed to be the same individual as the small whale observed off Tahara near Cape Irago in 2010,[137] making it the first confirmed constant migration out of Russian waters. The juvenile observed off Owase in Kumanonada Sea in 2009 might or might not be the same individual. The Ise and Mikawa Bay region is the only location along Japanese coasts that has several records since the 1980s (a mortal entanglement in 1968, above mentioned short-stay in 1982, self-freeing entanglement in 2005),[105][133] and is also the location where the first commercial whaling started. Other areas with several sighting or stranding records in recent years are off the Kumanonada Sea in Wakayama, off Oshika Peninsula in Tōhoku, and on coastlines close to Tomakomai, Hokkaido.

- Possibly the first confirmed record of living animals in Japanese waters in the Sea of Japan since the end of whaling occurred on 3 April 2014 at Nodumi Beach, Teradomari, Niigata.[138][139][140] Two individuals, measuring ten and five metres respectively, stayed near the mouth of Shinano River for three weeks.[39] It is unknown whether this was a cow-calf pair, which would have been a first record in Asia. All of the previous modern records in the Sea of Japan were of by-catches.[115]

- One of the above pair returned on the same beaches at the same time of a year in 2015.[109][141]

- A juvenile or possibly or not with another larger individual remained in Japanese waters between January or March and May 2015.[142] It was first confirmed occurrences of the species on remote, oceanic islands in Japan. One or more visited waters firstly on Kōzu-shima and Nii-Jima for weeks then adjacent to Miho no Matsubara and behind the Tokai University campus for several weeks.[143] Possibly the same individual was seen off Futo as well.[144] This later was identified as the same individual previously recorded on Sakhalin in 2014, the first re-recording one individual at different Asian locations.[110]

- A young whale was observed by land-based fishermen at Cape Irago in March, 2015.[145]

- One of the above pair appeared in 2015 off southeastern Japan and then reappeared off Tateyama in January, 2016.[146] The identity of this whale was confirmed by Nana Takanawa who photographed the same whale on Niijima in 2015.[147] Likely the same individual was sighted off Futo[144] and half an hour later off Akazawa beach in Itō, Shizuoka on the 14th.[148][149][150] The whale then stayed next to a pier on Miyake-jima and later at Habushi beach on Niijima, the same beach the same individual stayed near on the previous year.

- One whale of 9 metres (30 ft) was beached nearby Wadaura on March 4, 2016.[151] Investigations on the corpse indicate that this was likely a different individual from the above animal.

- A 7 metres (23 ft) carcass of young female was firstly reported floating along Atami on 4 April then was washed ashore on Ito on the 6th.[152]

- As of April 20, 2017, one or more whale(s) have been staying within Tokyo Bay since February although at one point another whale if or if not the same individual sighted off Hayama, Kanagawa.[153][154] It is unclear the exact number of whales included in these sightings; two whales reported by fishermen and Japanese coastal guard reported three whales on 20th or 21st.[155]

Whaling

North Pacific

Eastern population

Humans and orcas are the adult gray whale's only predators, although orcas are the more prominent predator.[156] Aboriginal hunters, including those on Vancouver Island and the Makah in Washington, have hunted gray whales.

Commercial whaling by Europeans of the species in the North Pacific began in the winter of 1845–46, when two United States ships, the Hibernia and the United States, under Captains Smith and Stevens, caught 32 in Magdalena Bay. More ships followed in the two following winters, after which gray whaling in the bay was nearly abandoned because "of the inferior quality and low price of the dark-colored gray whale oil, the low quality and quantity of whalebone from the gray, and the dangers of lagoon whaling."[157]

Gray whaling in Magdalena Bay was revived in the winter of 1855–56 by several vessels, mainly from San Francisco, including the ship Leonore, under Captain Charles Melville Scammon. This was the first of 11 winters from 1855 through 1865 known as the "bonanza period", during which gray whaling along the coast of Baja California reached its peak. Not only were the whales taken in Magdalena Bay, but also by ships anchored along the coast from San Diego south to Cabo San Lucas and from whaling stations from Crescent City in northern California south to San Ignacio Lagoon. During the same period, vessels targeting right and bowhead whales in the Gulf of Alaska, Sea of Okhotsk, and the Western Arctic would take the odd gray whale if neither of the more desirable two species were in sight.[157]

In December 1857, Charles Scammon, in the brig Boston, along with his schooner-tender Marin, entered Laguna Ojo de Liebre (Jack-Rabbit Spring Lagoon) or later known as Scammon's Lagoon (by 1860) and found one of the gray's last refuges. He caught 20 whales.[157] He returned the following winter (1858–59) with the bark Ocean Bird and schooner tenders A.M. Simpson and Kate. In three months, he caught 47 cows, yielding 1,700 barrels (270 m3) of oil.[158] In the winter of 1859–60, Scammon, again in the bark Ocean Bird, along with several other vessels, entered San Ignacio Lagoon to the south where he discovered the last breeding lagoon. Within only a couple of seasons, the lagoon was nearly devoid of whales.[157]

Between 1846 and 1874, an estimated 8,000 gray whales were killed by American and European whalemen, with over half having been killed in the Magdalena Bay complex (Estero Santo Domingo, Magdalena Bay itself, and Almejas Bay) and by shore whalemen in California and Baja California.[157]

A second, shorter, and less intensive hunt occurred for gray whales in the eastern North Pacific. Only a few were caught from two whaling stations on the coast of California from 1919 to 1926, and a single station in Washington (1911–21) accounted for the capture of another. For the entire west coast of North America for the years 1919 to 1929, 234 gray whales were caught. Only a dozen or so were taken by British Columbian stations, nearly all of them in 1953 at Coal Harbour.[159] A whaling station in Richmond, California, caught 311 gray whales for "scientific purposes" between 1964 and 1969. From 1961 to 1972, the Soviet Union caught 138 gray whales (they originally reported not having taken any). The only other significant catch was made in two seasons by the steam-schooner California off Malibu, California. In the winters of 1934–35 and 1935–36, the California anchored off Point Dume in Paradise Cove, processing gray whales. In 1936, gray whales became protected in the United States.[160]

Western population

The Japanese began to catch gray whales beginning in the 1570s. At Kawajiri, Nagato, 169 gray whales were caught between 1698 and 1889. At Tsuro, Shikoku, 201 were taken between 1849 and 1896.[161] Several hundred more were probably caught by American and European whalemen in the Sea of Okhotsk from the 1840s to the early 20th century.[162] Whalemen caught 44 with nets in Japan during the 1890s. The real damage was done between 1911 and 1933, when Japanese whalemen killed 1,449 after Japanese companies established several whaling stations on Korean Peninsula and on Chinese coast such as near the Daya bay and on Hainan Island. By 1934, the western gray whale was near extinction. From 1891 to 1966, an estimated 1,800–2,000 gray whales were caught, with peak catches of between 100 and 200 annually occurring in the 1910s.[162]

As of 2001, the Californian gray whale population had grown to about 26,000. As of 2016, the population of western Pacific (seas near Korea, Japan, and Kamchatka) gray whales was an estimated 200.[43]

North Atlantic

The North Atlantic population may have been hunted to extinction in the 18th century. Circumstantial evidence indicates whaling could have contributed to this population's decline, as the increase in whaling activity in the 17th and 18th centuries coincided with the population's disappearance.[24] A. B. Van Deinse points out the "scrag whale", described by P. Dudley in 1725, as one target of early New England whalers, was almost certainly the gray whale.[58][59] In his 1835 history of Nantucket Island, Obed Macy wrote that in the early pre-1672 colony, a whale of the kind called "scragg" entered the harbor and was pursued and killed by the settlers.[57] Gray whales (Icelandic sandlægja) were described in Iceland in the early 17th century.[163] Formations of commercial whaling among the Mediterranean basin(s) have been considered to be feasible as well.[55]

Conservation

Gray whales have been granted protection from commercial hunting by the International Whaling Commission (IWC) since 1949, and are no longer hunted on a large scale.

Limited hunting of gray whales has continued since that time, however, primarily in the Chukotka region of northeastern Russia, where large numbers of gray whales spend the summer months. This hunt has been allowed under an "aboriginal/subsistence whaling" exception to the commercial-hunting ban. Anti-whaling groups have protested the hunt, saying the meat from the whales is not for traditional native consumption, but is used instead to feed animals in government-run fur farms; they cite annual catch numbers that rose dramatically during the 1940s, at the time when state-run fur farms were being established in the region. Although the Soviet government denied these charges as recently as 1987, in recent years the Russian government has acknowledged the practice. The Russian IWC delegation has said that the hunt is justified under the aboriginal/subsistence exemption, since the fur farms provide a necessary economic base for the region's native population.[164]

Currently, the annual quota for the gray whale catch in the region is 140 per year. Pursuant to an agreement between the United States and Russia, the Makah tribe of Washington claimed four whales from the IWC quota established at the 1997 meeting. With the exception of a single gray whale killed in 1999, the Makah people have been prevented from hunting by a series of legal challenges, culminating in a United States federal appeals court decision in December 2002 that required the National Marine Fisheries Service to prepare an Environmental Impact Statement. On September 8, 2007, five members of the Makah tribe shot a gray whale using high-powered rifles in spite of the decision. The whale died within 12 hours, sinking while heading out to sea.[165]

As of 2018, the IUCN regards the gray whale as being of least concern from a conservation perspective. However, the specific subpopulation in the northwest Pacific is regarded as being critically endangered.[3] The northwest Pacific population is also listed as endangered by the U.S. government's National Marine Fisheries Service under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. The IWC Bowhead, Right and Gray Whale subcommittee in 2011 reiterated the conservation risk to western gray whales is large because of the small size of the population and the potential anthropogenic impacts.[46]

Gray whale migrations off of the Pacific Coast were observed, initially, by Marineland of the Pacific in Palos Verdes, California. The Gray Whale Census, an official gray whale migration census that has been recording data on the migration of the Pacific gray whale has been keeping track of the population of the Pacific gray whale since 1985. This census is the longest running census of the Pacific gray whale. Census keepers volunteer from December 1 through May, from sun up to sun down, seven days a week, keeping track of the amount of gray whales migrating through the area off of Los Angeles. Information from this census is listed through the American Cetacean Society of Los Angeles (ACSLA).

South Korea and China list gray whales as protected species of high concern. In South Korea, the Gray Whale Migration Site[166] was registered as the 126th national monument in 1962,[167] although illegal hunts have taken place thereafter,[128] and there have been no recent sightings of the species in Korean waters.

Rewilding proposal

In 2005, two conservation biologists proposed a plan to airlift 50 gray whales from the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic Ocean. They reasoned that, as Californian gray whales had replenished to a suitable population, surplus whales could be transported to repopulate the extinct British population.[168][169] As of 2017 this plan has not been undertaken.[170]

Threats

According to the Government of Canada's Management Plan for gray whales, threats to the eastern North Pacific population of gray whales include:[171] increased human activities in their breeding lagoons in Mexico, climate change, acute noise, toxic spills, aboriginal whaling, entanglement with fishing gear, boat collisions, and possible impacts from fossil fuel exploration and extraction.

Western gray whales are facing, the large-scale offshore oil and gas development programs near their summer feeding ground, as well as fatal net entrapments off Japan during migration, which pose significant threats to the future survival of the population.[46] The substantial nearshore industrialization and shipping congestion throughout the migratory corridors of the western gray whale population represent potential threats by increasing the likelihood of exposure to ship strikes, chemical pollution, and general disturbance.[47][162]

Offshore gas and oil development in the Okhotsk Sea within 20 km (12 mi) of the primary feeding ground off northeast Sakhalin Island is of particular concern. Activities related to oil and gas exploration, including geophysical seismic surveying, pipelaying and drilling operations, increased vessel traffic, and oil spills, all pose potential threats to western gray whales. Disturbance from underwater industrial noise may displace whales from critical feeding habitat. Physical habitat damage from drilling and dredging operations, combined with possible impacts of oil and chemical spills on benthic prey communities also warrants concern. The western gray whale population is considered to be endangered according to IUCN standards.[47][93]

Along Japanese coasts, four females including a cow-calf pair were trapped and killed in nets in the 2000s. There had been a record of dead whale thought to be harpooned by dolphin-hunters found on Hokkaido in the 1990s.[47][172] Meats for sale were also discovered in Japanese markets as well.[173]

2019 has had a record number of gray whale strandings and deaths, with their being 122 strandings in United States waters and 214 in Canadian waters. The cause of death in some specimens appears to be related to poor nutritional condition.[174] It is hypothesized that some of these strandings are related to changes in prey abundance or quality in the Arctic feeding grounds, resulting in poor feeding. Some scientists suggest that the lack of sea ice has been preventing the fertilization of amphipods, a main source of food for gray whales, so that they have been hunting krill instead, which is far less nutritious. More research needs to be conducted to understand this issue.[175]

A recent study provides some evidence that solar activity is correlated to gray whale strandings. When there was a high prevalence of sunspots, gray whales were five times more likely to strand. A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that solar storms release a large amount of electromagnetic radiation, which disrupts earth's magnetic field and/or the whale's ability to analyze it.[176] This may apply to the other species of cetaceans, such as sperm whales.[177] However, there is not enough evidence to suggest that whales navigate through the use of magnetoreception (an organisms' ability to sense a magnetic field).

Orcas are "a prime predator of gray whale calves."[44] Typically three to four orcas ram a calf from beneath in order to separate it from its mother, who defends it. Humpback whales have been observed defending gray whale calves from orcas.[44] Orcas will often arrive in Monterey Bay to intercept gray whales during their northbound migration, targeting females migrating with newborn calves. They will separate the calf from the mother and hold the calf under water to drown it. The tactic of holding whales under water to drown them is certainly used by orcas on adult gray whales as well.[178] It is roughly estimated that 33% of the gray whales born in a given year might be killed by predation.[179]

Captivity

Because of their size and need to migrate, gray whales have rarely been held in captivity, and then only for brief periods of time. The first captive gray whale, who was captured in Scammon's Lagoon, Baja California in 1965, was named Gigi and died two months later from an infection.[180] The second gray whale, who was captured in 1972 from the same lagoon, was named Gigi II and was released a year later after becoming too large for the facilities.[181] The third gray whale, J.J., first beached herself in Marina del Rey, California where she was rushed to SeaWorld San Diego. After 14 months, she was released because she also grew too large to be cared for in the existing facilities. At 19,200 pounds (8,700 kg) and 31 feet (9.4 m) when she was released, J.J. was the largest marine mammal ever to be kept in captivity.[182]

See also

- Gray Whale Cove State Beach

- Gray Whale Ranch

- List of cetaceans

References

- Mead, J. G.; Brownell, R. L. Jr. (2005). "Order Cetacea". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 723–743. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Boessenecker, Robert (2007). "New records of fossil fur seals and walruses (Carnivora: Pinnipedia) from the late Neogene of Northern California". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27: 50A.

- Cooke, J.G. (2018). "Eschrichtius robustus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T8097A50353881. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T8097A50353881.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- Britannica Micro.: v. IV, p. 693.

- Nowak, Ronald M. (7 April 1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. JHU Press. p. 1132. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- Recovery Strategy for the Grey Whale (Eschrichtius robustus), Atlantic Population, in Canada. Dsp-psd.pwgsc.gc.ca (2012-07-31). Retrieved on 2012-12-20.

- Fisheries, NOAA (2020-06-25). "Gray Whale | NOAA Fisheries". NOAA. Retrieved 2020-06-29.

- Gray Whale Eschrichtius robustus. American Cetacean Society

- Gray Whale. Worldwildlife.org. Retrieved on 2012-12-20.

- Perrin, William F.; Würsig, Bernd G.; Thewissen, J. G. M. (2009). Encyclopedia of marine mammals. Academic Press. p. 404. ISBN 978-0-12-373553-9.

- The Paleobiology Database Eschrichtiidae entry accessed on 26 December 2010

- Kimura, T.; Hasegawa, Y.; Kohno, N. (2017). "A new species of the genus Eschrichtius (Cetacea: Mysticeti) from the Early Pleistocene of Japan". Paleontological Research. 22 (1): 1–19. doi:10.2517/2017PR007. S2CID 134494152.

- Seeman, Mette E.; et al. (December 2009). "Radiation of extant cetaceans driven by restructuring of the ocean". Systematic Biology. 58 (6): 573–585. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syp060. JSTOR 25677547. PMC 2777972. PMID 20525610.

- Arnason, U.; Gullberg A. & Widegren, B. (1993). "Cetacean mitochondrial DNA control region: sequences of all extant baleen whales and two sperm whale species". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 10 (5): 960–970. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040061. PMID 8412655.

- Sasaki, T.; Nikaido, Masato; Hamilton, Healy; Goto, Mutsuo; Kato, Hidehiro; Kanda, Naohisa; Pastene, Luis; Cao, Ying; et al. (2005). "Mitochondrial phylogenetics and evolution of mysticete whales". Systematic Biology. 54 (1): 77–90. doi:10.1080/10635150590905939. PMID 15805012.

- McGowen, Michael R; Tsagkogeorga, Georgia; Álvarez-Carretero, Sandra; dos Reis, Mario; Struebig, Monika; Deaville, Robert; Jepson, Paul D; Jarman, Simon; Polanowski, Andrea; Morin, Phillip A; Rossiter, Stephen J (2019-10-21). "Phylogenomic Resolution of the Cetacean Tree of Life Using Target Sequence Capture". Systematic Biology. 69 (3): 479–501. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syz068. ISSN 1063-5157. PMC 7164366. PMID 31633766.

- Árnason, Úlfur; Lammers, Fritjof; Kumar, Vikas; Nilsson, Maria A.; Janke, Axel (2018). "Whole-genome sequencing of the blue whale and other rorquals finds signatures for introgressive gene flow". Science Advances. 4 (4): eaap9873. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.9873A. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aap9873. PMC 5884691. PMID 29632892.

- "Explore the Database". www.mammaldiversity.org. Retrieved 2021-08-20.

- Gray (1864). "Eschrichtius". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 3 (14): 350.

- Pyenson, Nicholas D.; Lindberg, David R. (2011). Goswami, Anjali (ed.). "What happened to gray whales during the Pleistocene? The ecological impact of sea-level change on benthic feeding areas in the North Pacific Ocean". PLOS ONE. 6 (7): e21295. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621295P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021295. PMC 3130736. PMID 21754984.

- Cope (1869). "Rhachianectes". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 21: 15.

- Cederlund, BA (1938). "A subfossil gray whale discovered in Sweden in 1859". Zoologiska Bidrag från Uppsala. 18: 269–286.

- Mead JG, Mitchell ED (1984). "Atlantic gray whales". In Jones ML, Swartz SL, Leatherwood S (eds.). The Gray Whale. London: Academic Press. pp. 33–53.

- Bryant, PJ (1995). "Dating remains of gray whales from the eastern North Atlantic". Journal of Mammalogy. 76 (3): 857–861. doi:10.2307/1382754. JSTOR 1382754.

- Waser, Katherine (1998). "Ecotourism and the desert whale: An interview with Dr. Emily Young". Arid Lands Newsletter.

- "Eschrichtius robustus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved March 18, 2006.

- Erxleben 1777, p. 610 (Balaena gibbosa)

- E.g. Erxleben 1777, pp. 610–611; Anderson 1746, p. 201; Brisson 1762, p. 221

- Barnes & McLeod 1984, pp. 4–5

- Dudley 1725, p. 258

- Lilljeborg 1861, p. 39

- Gray 1864, p. 351

- Van Beneden & Gervais 1868, pp. 290–291

- Scammon 1874, The marine mammals of the north-western coast of North America

- Bryant 1995, pp. 857–859

- "How to Spot Whales from Shore | the whale trail". thewhaletrail.org. 13 February 2011. Retrieved 2017-02-13.

- Burnie D. and Wilson D.E. (eds.) (2005) Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife. DK Adult, ISBN 0789477645

- Kato H.; Kishiro T.; Nishiwaki S.; Nakamura G.; Bando T.; Yasunaga G.; Sakamoto T.; Miyashita T. (2014). "Status Report of Conservation and Researches on the Western North Pacific Gray Whales in Japan, May 2013 – April 2014 [document SC/65b/BRG12]". Retrieved 2021-08-21.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Nakamura G.; Kato H. (2014). "日本沿岸域に近年(1990–2005 年)出現したコククジラEschrichtius robustus の骨学的特徴,特に頭骨形状から見た北太平洋西部系群と東部系群交流の可能性" (PDF). 哺乳類科学. The Mammal Society of Japan, Cetacean Research Laboratory in Marine environmental section in the Graduate School of Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, J-STAGE. 54 (1): 73–88. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- Shpak O. (2011). Observation of the gray whale in the Laptev Sea. Standing expedition of IEE Russian Academy of Sciences.

- Xianyan, Wang; Min, Xu; Fuxing, Wu; Weller, David W.; Xing, Miao; Lang, Aimee R.; Qian, Zhu (2015). "Short Note: Insights from a Gray Whale (Eschrichtius robustus) Bycaught in the Taiwan Strait Off China in 2011". Aquatic Mammals. 41 (3): 327. doi:10.1578/AM.41.3.2015.327.

- Noaa. (n.d.). Gray Whale. Retrieved February 21, 2020, from https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/gray-whale

- Andrew Lachman (May 8, 2018). "Unusual Number of Killer Whales Sighted". San Jose Mercury-News. Bay Area News Group. p. B1.

- "Whale Conservation Success Highlighted in IUCN Red List Update". The Maritime Executive. Retrieved 2018-11-25.

- "Report of the Scientific Committee, Tromsø, Norway, 30 May to 11 June 2011 Annex F: Sub-Committee on Bowhead, Right and Gray Whale" (PDF). IWC Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2011.

- Cooke, J.G.; Taylor, B.L.; Reeves, R. & Brownell Jr., R.L. (2018). "Eschrichtius robustus (western subpopulation)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T8099A50345475. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- "Fin whale, mountain gorilla populations rise amid conservation action". Retrieved 2018-11-25.

- Rice DW (1998). Marine Mammals of the World. Systematics and Distribution. Special Publication Number 4. Lawrence, Kansas: The Society for Marine Mammalogy.

- Jones L.M..Swartz L.S.. Leatherwood S.. The Gray Whale: Eschrichtius Robustus. "Eastern Atlantic Specimens". pp 41–44. Academic Press. Retrieved on September 5, 2017

- Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Occurrence Detail 1322462463. Retrieved on September 21, 2017

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2016. Grey Whale (Atlantic population) Eschrichtius robustus. Retrieved on August 15, 2017

- "Regional Species Extinctions – Examples of regional species extinctions over the last 1000 years and more" (PDF). Census of Marine Life. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-04-25. Retrieved 2014-07-05.

- Macé M. (2003). "Did the Gray Whale calve in the Mediterranean?". Lattara. 16: 153–164.

- The MORSE Project – Ancient whale exploitation in the Mediterranean: species matters Archived 2016-12-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Ana S. L. Rodrigues; Anne Charpentier; Darío Bernal-Casasola; Armelle Gardeisen; Carlos Nores; José Antonio Pis Millán; Krista McGrath; Camilla F. Speller (July 11, 2018). "Forgotten Mediterranean calving grounds of grey and North Atlantic right whales: evidence from Roman archaeological records". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 285 (1882). doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.0961. PMC 6053924. PMID 30051821.

- Macy O (1835). The History of Nantucket:being a compendious account of the first settlement of the island by the English:together with the rise and progress of the whale fishery, and other historical facts relative to said island and its inhabitants:in two parts. Boston: Hilliard, Gray & Co. ISBN 1-4374-0223-2.

- Van Deinse, AB (1937). "Recent and older finds of the gray whale in the Atlantic". Temminckia. 2: 161–188.

- Dudley, P (1725). "An essay upon the natural history of whales". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 33 (381–391): 256–259. Bibcode:1724RSPT...33..256D. doi:10.1098/rstl.1724.0053. JSTOR 103782. S2CID 186208376.

- Hamilton, Alex (October 8, 2015). "The Gray Whale Sneaks Back into the Atlantic, Two Centuries Later". WNYC. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- Schiffman, Richard (February 25, 2016). "Why Are Gray Whales Moving to the Ocean Next Door?". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- Alter, S. Elizabeth; Hofreiter, Michael; et al. (March 9, 2015). "Climate impacts on transocean dispersal and habitat in gray whales from the Pleistocene to 2100". Molecular Ecology. 24 (7): 1510–1522. doi:10.1111/mec.13121. PMID 25753251. S2CID 17313811.

- SOS Dolfijn, 2021, Grijze walvis gemeld bij Marokko

- Observation.org, 2021-04-04, Archive – Yasutaka Imai

- "Ponza, a gray whale sighted for the first time in Italy". Italy24 News English. April 15, 2021.

- Alter, SE; Newsome, SD; Palumbi, SR (May 2012). "Pre-Whaling Genetic Diversity and Population Ecology in Eastern Pacific Gray Whales: Insights from Ancient DNA and Stable Isotopes". PLOS ONE. 7 (5): e35039. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...735039A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035039. PMC 3348926. PMID 22590499.

- Alter, S. E.; Rynes, E.; Palumbi, S. R. (11 September 2007). "DNA evidence for historic population size and past ecosystem impacts of gray whales". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (38): 15162–15167. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10415162A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0706056104. PMC 1975855. PMID 17848511.

- "Gray Whale Population Studies". NOAA, National Marine Fisheries Service, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, Protected Resource Division. 2010. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- "Automatic Whale Detector". NOAA, National Marine Fisheries Service, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, Protected Resource Division. 2015. Archived from the original on 2016-02-23. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- "Western Pacific Gray Whale, Sakhalin Island 2010". Oregon State University, Marine Mammal Institute. February 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- Rugh, David J.; Fraker, Mark A. (June 1981). "Gray Whale (Eschrichtius robustus) Sightings in Eastern Beaufort Sea" (PDF). Arctic. 34 (2). doi:10.14430/arctic2521. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

- Shpak V.O.; Kuznetsova M.D.; Rozhnov V.V. (2013). "Observation of the Gray Whale (Eschrichtius robustus) in the Laptev Sea". Biology Bulletin. 40 (9): 797–800. doi:10.1134/S1062359013090100. S2CID 18169458.

- Nefedova T., Gavrilo M., Gorshkov S. (2013). Летом в Арктике стало меньше льда Archived 2014-05-24 at the Wayback Machine. Russian Geographical Society. retrieved on 24-05-2014

- Elwen H.S., Gridley T. (2013). Gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) sighting in Namibia (SE Atlantic) – first record for Southern Hemisphere. Mammal Research Institute, the University of Pretoria and the Namibian Dolphin Project. retrieved on 18-05-2014

- צפריר רינת 08.05.2010 16:47 עודכן ב: 16:50. "לווייתן אפור נצפה בפעם הראשונה מול חופי ישראל – מדע וסביבה – הארץ". Haaretz.co.il. Archived from the original on 2010-05-11. Retrieved 2012-06-26.

- "Satellites witness lowest Arctic ice coverage in history". European Space Agency. Retrieved 2007-09-14.

- Walker, Matt (30 May 2010). "Mystery gray whale sighted again off Spain coast". BBC News. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- Namibian Dolphin Project: A rare and mysterious visitor in Walvis Bay. Namibiandolphinproject.blogspot.ch (2013-05-14). Retrieved on 2013-07-28.

- Alter, S. Elizabeth; Meyer, Matthias; Post, Klaas; Czechowski, Paul; Gravlund, Peter; Gaines, Cork; Rosenbaum, Howard C.; Kaschner, Kristin; Turvey, Samuel T.; Van Der Plicht, Johannes; Shapiro, Beth; Hofreiter, Michael (2015). "Climate impacts on transocean dispersal and habitat in gray whales from the Pleistocene to 2100". Molecular Ecology. 24 (7): 1510–1522. doi:10.1111/mec.13121. PMID 25753251. S2CID 17313811.

- Rice, D.; Wolman, A. & Braham, H. (1984). "The Gray Whale, Eschrichtius robustus" (PDF). Marine Fisheries Review. 46 (4): 7–14.

- Jones, Mary Lou. "The Reproductive Cycle in Gray Whales Based on Photographic Resightings of Females on the Breeding Grounds from 1977–82" (PDF). Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. (t2): 177. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-26.

- Swartz, Steven L.; Taylor, Barbara L.; Rugh, David J. (2006). "Gray whale Eschrichtius robustus population and stock identity" (PDF). Mammal Review. 36 (1): 66–84. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2006.00082.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-26.

- The Marine Mammal Center. (n.d.). Retrieved February 21, 2020, from https://www.marinemammalcenter.org/education/marine-mammal-information/cetaceans/gray-whale.html Archived 2020-02-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Solutions, Gray Whale Foundation | Rosodigital Creative. "The Gray Whale Foundation". www.graywhalefoundation.org. Archived from the original on 2018-02-03. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- "Conjoined gray whale calves discovered in Mexican lagoon could be". The Independent. January 8, 2014.

- Oliver, J. S., Slattery, P. N., Silberstein, M. A., & O'Connor, E. F. (1981). A Comparison of Gray Whale, Eschrichtius robustus, Feeding in the Bering Sea and Baja California . Fishery Bulletin, 81(3), 513–522.

- Newell, Carrie L.; Cowles, Timothy J. (30 November 2006). "Unusual gray whale Eschrichtius robustus feeding in the summer of 2005 off the central Oregon Coast". Geophysical Research Letters. 33 (22): L22S11. Bibcode:2006GeoRL..3322S11N. doi:10.1029/2006GL027189.

- Dunham, J. S., & Duffus, D. A. (2001). Foraging patterns of gray whales in central Clayoquot Sound, British Columbia, Canada. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 223, 299–310.

- Moore, Sue E.; Wynne, Kate M.; Kinney, Jaclyn Clement; Grebmeier, Jacqueline M. (April 2007). "Gray Whale Occurrence and Forage Southeast of Kodiak, Island, Alaska". Marine Mammal Science. 23 (2): 419–428. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2007.00102.x.

- "GRAY WHALE: ZoomWhales.com". Enchantedlearning.com. Retrieved 2012-06-26.

- Weller, D.W.; Wursig, B.; Bradford, A.L.; Burdin, A.M.; Blokhin, S.A.; inakuchi, H. & Brownell, R.L. Jr. (1999). "Gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) off Sakhalin Island, Russia: seasonal and annual patterns of occurrence". Mar. Mammal Sci. 15 (4): 1208–27. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00886.x.

- Fadeev V.I. (2003). Benthos and prey studies in feeding grounds of the Okhotsk-Korean population of gray whales Archived 2017-01-06 at the Wayback Machine. Final report on materials from field studies on the research vessel Nevelskoy in 2002. Marine Biology Institute, Vladivostok.

- Reeves, R.R., Brownell Jr., R.L., Burdin, A., Cooke, J.G., Darling, J.D., Donovan, G.P., Gulland, F.M.D., Moore, S.E., Nowacek, D.P., Ragen, T.J., Steiner, R.G., Van Blaricom, G.R., Vedenev, A. and Yablokov, A.V. (2005). Report of the Independent Scientific review Panel on the Impacts of Sakhalin II Phase 2 on Western Pacific Gray Whales and Related Biodiversity. IUCN, Gland Switzerland, and Cambridge, U.K.

- Swartz, Steven L. (2018). "Gray Whale". Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. pp. 422–428. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-804327-1.00140-0. ISBN 9780128043271.

- Pike, Gordon C. (1 May 1962). "Migration and Feeding of the Gray Whale (Eschrichtius gibbosus)". Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. 19 (5): 815–838. doi:10.1139/f62-051.

- Map of the Gray Whale Migration. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.bajaecotours.com/gray-whale-migration-map.php

- Davis, T.N. (1979-09-06). "Recovery of the Gray Whale". Alaska Science Forum. Archived from the original on 2009-02-12. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- Niemann, G. (2002). Baja Legends. Sunbelt Publications. pp. 171–173. ISBN 0-932653-47-2.

- Findley, T.L.; Vidal, O. (2002). "Gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) at calving sites in the Gulf of California, México". Journal of Cetacean Research and Management. 4 (1): 27–40.

- Mark Carwardine, 2019, Bloomsbury Publishing, Handbook of Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises, p.80

- Koontz, K. (n.d.). Close Encounters With Bajas Gray Whales. Retrieved February 21, 2020, from https://www.oceanicsociety.org/blog/1569/close-encounters-with-bajas-gray-whales Archived 2020-02-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Lang, A. (January 19, 2011). "Demographic distinctness of the Pacific Coast Feeding Group of Gray Whales (Eschrictius robustus)". NOAA Fisheries Service, Protected Resource Division, Southwest Fisheries Science Center. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- "A Gray Area: On the Matter of Gray Whales in the Western North Pacific". 2015-05-07. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- Nambu, Hisao; Ishikawa, Hajime & Yamada, Tadasu K. (2010). "Records of the western gray whale, Eschrichtius robustus: its distribution and migration" (PDF). Japan Cetology. 20 (20): 21–29. doi:10.5181/cetology.0.20_21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-10-15.

- "連鎖の崩壊 第3部 命のふるさと 2−四国新聞社". Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- Suitube (2012). "中村宏治 コククジラ撮影秘話!". Japan Underwater Films. p. YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-11-18. Retrieved 2015-01-07.

- "コククジラが三河湾を回遊/絶滅恐れ、3月に1頭". 四国新聞社. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- "サービス終了のお知らせ". Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- "Nearly extinct western gray whale sighted again in coastal waters off Niigata". Asahi. 2015. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- Weller, D. W.; Takanawa, N.; Ohizumi, H.; Funahashi, N.; Sychenko, O. A.; Burdin, A. M.; Lang, A. R.; Brownell Jr., R. L. (2015). "Photographic match of a western gray whale between Sakhalin Island, Russia, and the Pacific Coast of Japan. Paper SC/66a/BRG/17". International Whaling Commission, Scientific Committee (SC66a meeting). San Diego, USA.

- Vladimirov, V.L. (1994). "Recent distribution and abundance level of whales in Russian Far-Eastern seas". Russian J. Mar. Biol. 20: l–9.

- Kato, H., Ishikawa, H., Bando, T., Mogoe, T. and Moronuki, H. (2006). Status Report of Conservation and Researches on the Western Gray Whales in Japan, June 2005 – May 2006. Paper SC/58/O14 presented to the IWC Scientific Committee, June 2006

- Zhu, Q. (1998). "Strandings and sightings of the western Pacific stock of the gray whale Eschrichtius robustus in Chinese coastal waters. Paper SC/50lAS5 presented to the IWC Scientific Committee, April 1998, Oman

- Краснокнижный серый кит приплыл под окна офиса заповедника «Командорский» Archived 2017-03-12 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on March 09, 2017

- Nambu, Hisao; Minowa, Kazuhiro; Tokutake, Kouji & Yamada, Tadasu K. (2014). "New observations on Gray whales, Eschrichtius robustus, from Central Japan, Sea of Japan". Japan Cetology. 24 (24): 11–14. doi:10.5181/cetology.0.24_11.

- Uni Y. (2004) 西部系群コククジラ Eschrictius robustus の記録集成と通過海峡 Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine. dion.ne.jp

- "珍客コククジラ 静岡沖で潮吹き". geocities.jp. Archived from the original on 2014-05-12. Retrieved 2014-05-09.

- Brownell, R.L. Jr.; Chun, C. (1977). "Probable existence of the Korean stock of the gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus)". J. Mammal. 58 (2): 237–9. doi:10.2307/1379584. JSTOR 1379584.

- Tsai, Cheng-Hsiu; Fordyce, R. Ewan; Chang, Chun-Hsiang; Lin, Liang-Kong (2014). "Quaternary Fossil Gray Whales from Taiwan". Paleontological Research. 18 (2): 82. doi:10.2517/2014PR009. S2CID 131250469.

- Brownell, R.L., Donovan, G.P., Kato, H., Larsen, F., Mattila, D., Reeves, R.R., Rock, Y., Vladimirov, V., Weller, D. & Zhu, Q. (2010) Conservation Plan for Western North Pacific Gray Whales (Eschrichtius robustus). IUCN

- 2014. Chuẩn hóa lại tên cá voi xám trong bộ sưu tập mẫu vật của bảo tàng lịch sử tỉnh Quảng Ninh Archived 2017-03-12 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on March 09, 2017

- 2012. Bí ẩn những con cá khổng lồ dạt vào biển Việt Nam Archived 2017-03-12 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on March 09, 2017

- What's on Xiamen.Tags > Pingtan gray whale Archived 2017-06-25 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on November 24. 2014

- "濒危物种数据库 – 灰鲸 Eschrichtius robustus (Lilljeborg, 1861)". 中华人民共和国濒危物种科学委员会. p. the CITES. Archived from the original on 2014-12-25. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- Uni Y., 2010, 『コククジラは大隅海峡を通るのか?』, Japan Cetology Research Group News Letter 25, retrieved on 11-05-2014

- "海棲哺乳類情報データベース". Archived from the original on 3 September 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- Kim W.H., Sohn H.; An Y-R.; Park J.K.; Kim N.D.; Doo Hae An H.D. (2013). "Report of Gray Whale Sighting Survey off Korean waters from 2003 to 2011". Cetacean Research Institute, National Fisheries Research & Development Institute. Retrieved 2014-05-18.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Disappearing Whales: Korea's Inconvenient Truth Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine. Greenpeace (2012)

- Hyun Woo Kim, Hawsun Sohn, Yasutaka Imai, 2018, Possible occurrence of a Gray Whale off Korea in 2015, International Whaling Commission, SC/67B/CMP/11 Rev1

- Gagnon, Chuck (November 2016) Western gray whale activity in the East China Sea from acoustic data: Memorandum for Dr. Brandon Southall Archived 2016-12-24 at the Wayback Machine. iucn.org

- Kato H.; Kishiro T.; Bando T.; Ohizumi H.; Nakamura G.; Okazoe N.; Yoshida H.; Mogoe T.; Miyashita T. (2015), "Status Report of Conservation and Researches on the Western North Pacific Gray Whales in Japan, May 2014 – April 2015", SC/66a/BRG, retrieved 2016-02-23

- "Japan Underwater Films". Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- Marine Mammals Stranding DataBase. kahaku.go.jp

- "footage". Beachland.jp. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- 2012 年に漂着した海棲哺乳類につい. .beachland.jp

- "伊勢湾でクジラ発見!!". Beachland.jp. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- ""プリン展"から"コククジラ展"へ". www.beachland.jp. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- Birdnetmaster (2015). "2014年 日本海に出現したコククジラ / Grey whale 2014 Sea of Japan". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-11-18. Retrieved 2015-10-14.

- Aoyagi A.; Okuda J.; Nambu H.; Honma Y.; Yamada K. T.; Satou T.; Ohta M.; Ohara J.; Imamura M. (2014). "2014年春に新潟県信濃川大河津分水路河口付近に出現したコククジラの観察". Japan Cetology. 24: 15–22. doi:10.5181/cetology.0.24_15.

- "寺泊沖にクジラ現る・長岡 「生きたまま初めて見た」地元驚き". The 47NEWS. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- Itou K. (2015). "絶滅危惧のコククジラ、2年連続で現れた 新潟・長岡". The Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 2015-10-13.

- Takanawa N. (2015). "【フォトギャラリー】伊豆諸島で見つかった希少なコククジラ". Japanese office of the National Geographic. Retrieved 2015-10-14.

- "コククジラ in 日本(超貴重)Western Gray Whale sightings (Extremely Rare!)". YouTube. 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-14.

- "ダイビング中にコククジラと遭遇のミラクル! ~房総半島・西川名と伊豆半島・赤沢で相次ぐ~ | オーシャナ". Oceana.ne.jp. 2016-01-19. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- "Ryo Okamoto – 伊良湖岬で釣りしてたら、クジラ出現。..." Facebook. 2015-03-23. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- "今日のコククジラ 館山 西川名 201601f". YouTube. 2016-01-09. Archived from the original on 2021-11-18. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- Braulik, Gill (2015-04-16) Young Gray Whale Sighted near Tokyo Islands. IUCN SSC – Cetacean Specialist Group

- "赤沢 コククジラ 2016.1.14". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-11-18. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- "伊豆のダイビングサービス | ダイビングサービス mieux -みう- | クジラが~!!". Ds-mieux.com. 14 January 2016. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- "動画っす(`_´)ゞ – ダイビングサービス mieux – みう". Facebook. 2016-01-13. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- 絶滅心配 コククジラの死骸 千葉・南房総で見つかる. nhk.or.jp (2015-05-03)

- "伊豆新聞デジタル – IZU SHIMBUN DIGITAL --". 伊豆新聞デジタル. Archived from the original on April 20, 2016.

- 東京湾でクジラの目撃相次ぐ. Retrieved on April 21, 2017

- 鎌倉ゴムボートコング山田肇. 2017.「https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9v7b02cCsP0 ゴムボート東京湾ホエールウォッチング❗ 」. YouTube. Retrieved on April 21, 2017

- みんなのニュース. 2017. 撮影成功! 姿現した「東京湾クジラ」 Archived 2017-04-22 at the Wayback Machine. The Fuji News Network Retrieved on April 22, 2017

- "Gray Whales, Eschrichtius robustus". MarineBio.org. Archived from the original on 2018-12-15. Retrieved 2018-12-13.

- Henderson, David A. (1972). Men & Whales at Scammon's Lagoon. Los Angeles: Dawson's Book Shop.

- Scammon, Charles Melville; David A. Henderson (1972). Journal aboard the bark Ocean Bird on a whaling voyage to Scammon's Lagoon, winter of 1858–59. Los Angeles: Dawson's Book Shop.

- Tønnessen, Johan; Arne Odd Johnsen (1982). The History of Modern Whaling. University of California Press, Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-03973-4.

- Brownell Jr., R. L. and Swartz, S. L. 2006. The floating factory ship California operations in Californian waters, 1932–1937. International Whaling Commission, Scientific Committee.

- Kasuya, T. (2002). "Japanese whaling", in Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. W. F. Perrin, B. Wursig, and J.G.M. Thewissen, eds. San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 655–662, ISBN 978-0-12-373553-9.

- David W. Weller; Alexander M. Burdin; Bernd Würsig; Barbara L. Taylor; Robert L. Brownell Jr; et al. (2002). "The western gray whale: a review of past exploitation, current status and potential threats". Journal of Cetacean Research and Management. 4 (1): 7–12 – via University of Nebraska - Lincoln.

- Jón Guðmundsson lærði (1966). Ein stutt udirrietting um Íslands adskiljanlegu náttúrur. ed. Halldór Hermannsson, Cornell University Library, Ithaca, New York.

- Russian Federation. (n.d.). Retrieved February 11, 2020, from https://iwc.int/russian-federation

- Mapes, Lynda V.; Ervin, Keith (2007-09-09). "Gray whale shot, killed in rogue tribal hunt". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 2011-11-25.

- "- 문화재검색결과 상세보기 – 문화재검색". Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- "Gray Whale Migration Site (울산 귀신고래 회유해면)". Official Korea Tourism Organization.

- Hooper, Rowan (23 July 2005). "Moving Whales Across the World". New Scientist. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- Hooper, Rowan (18 July 2005). "US whales may be brought to UK". BBC News. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- Monbiot, George (2013). Feral: Searching for Enchantment on the Frontiers of Rewilding. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-1-846-14748-7.

- The Grey Whale (Eastern North Pacific Population) Archived January 14, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Species at Risk. dfo-mpo.gc.ca

- Yamada T.; Watanabe Y. "Marine Mammals Stranding DataBase – Gray Whale". The National Museum of Nature and Science. Archived from the original on 2014-05-12. Retrieved 2015-01-13.

- Baker, C. S.; Dalebout, M. L.; Lento, G. M.; Funahashi, Naoko (2002). "Gray Whale Products Sold in Commercial Markets Along the Pacific Coast of Japan". Marine Mammal Science. 18: 295. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2002.tb01036.x.

- Noaa. (2020, January 17). 2019 Gray Whale Unusual Mortality Event along the West Coast. Retrieved February 11, 2020, from https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/marine-life-distress/2019-gray-whale-unusual-mortality-event-along-west-coast

- Daley, J. (2019, June 3). NOAA Is Investigating 70 Gray Whale Deaths Along the West Coast. Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/noaa-investigating-dozens-gray-whale-deaths-along-west-coast-180972333/

- Solar Storms Might Be Causing Gray Whales to Get Lost. (n.d.). Retrieved February 11, 2020, from https://www.livescience.com/solar-storms-and-gray-whale-strandings.html

- Vanselow, Klaus Heinrich; Jacobsen, Sven; Hall, Chris; Garthe, Stefan (15 August 2017). "Solar storms may trigger sperm whale strandings: explanation approaches for multiple strandings in the North Sea in 2016". International Journal of Astrobiology. 17 (4): 336–344. doi:10.1017/s147355041700026x.

- "Deadly Killer Whale Moments (BBC Earth)". YouTube.