Hadrian's Wall

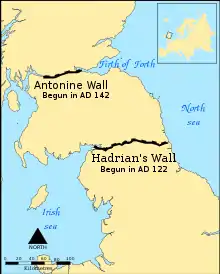

Hadrian's Wall (Latin: Vallum Aelium), also known as the Roman Wall, Picts' Wall, or Vallum Hadriani in Latin, is a former defensive fortification of the Roman province of Britannia, begun in AD 122 in the reign of the emperor Hadrian.[1] Running "from Wallsend on the River Tyne in the east to Bowness-on-Solway in the west", the wall covered the whole width of the island.[2] In addition to the wall's defensive military role, its gates may have been customs posts.[3]

| Hadrian's Wall | |

|---|---|

The location of Hadrian's Wall in what is now northern England, and the later Antonine Wall in what is now the Central Belt of Scotland | |

| Location | Northern England |

| Coordinates | 55°01′27″N 2°17′33″W |

| Area | 73 miles (117 km) |

| Built | 122 AD |

| Built for | Hadrian |

| Visitors | 100,000+ annually |

| Governing body | Historic England |

| Owner | Various private and public ownerships |

| Criteria | ii, iii, iv |

| Designated | 1987 (11th session) |

| Part of | Frontiers of the Roman Empire |

| Reference no. | 430 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Military of ancient Rome |

|---|

|

|

A significant portion of the wall still stands and can be followed on foot along the adjoining Hadrian's Wall Path. The largest Roman archaeological feature in Britain, it runs a total of 73 miles (117.5 kilometres) in northern England.[4] Regarded as a British cultural icon, Hadrian's Wall is one of Britain's major ancient tourist attractions.[5] It was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987.[6] The Antonine Wall, thought by some to be based on Hadrian's wall,[7] was declared a World Heritage site in 2008.[8][9]

Hadrian's Wall marked the boundary between Roman Britannia and unconquered Caledonia to the north.[lower-alpha 1] The wall lies entirely within England and has never formed the Anglo-Scottish border.[10][11][12]

Dimensions

The length of the wall was 80 Roman miles (a unit of length equivalent to about 1,620 yards or 1,480 metres), or 73 modern miles (117 kilometres).[13] This covered the entire width of the island, from Wallsend on the River Tyne in the east to Bowness-on-Solway in the west.[2]

Not long after construction began on the wall, its width was reduced from the originally planned 10 feet (3.0 m) to about 8 feet (2.4 m), or even less depending on the terrain.[2] As some areas were constructed of turf and timber, it would take decades for certain areas to be modified and replaced by stone.[2]

Bede, a medieval historian, wrote that the wall stood 12 feet (4 metres) high, with evidence suggesting it could have been a few feet higher at its formation.[2]

R. S. O. Tomlin argues that along the miles-long wall there would have been a tower every third of a mile, adding more to the dimensions of the structure, as evident by the plentiful remains of the turrets.[14]

Route

Hadrian's Wall extended west from Segedunum at Wallsend on the River Tyne, via Carlisle and Kirkandrews-on-Eden, to the shore of the Solway Firth, ending a short but unknown distance west of the village of Bowness-on-Solway.[15] The A69 and B6318 roads follow the course of the wall from Newcastle upon Tyne to Carlisle, then along the northern coast of Cumbria (south shore of the Solway Firth). The route was slightly north of Stanegate, an important Roman road built several decades earlier to link two forts that guarded important river crossings: Corstopitum (Corbridge) on the River Tyne and Luguvalium (Carlisle) on the River Eden.

Although the curtain wall ends near Bowness-on-Solway, this does not mark the end of the line of defensive structures. The system of milecastles and turrets is known to have continued along the Cumbria coast as far as Risehow, south of Maryport.[16] For classification purposes, the milecastles west of Bowness-on-Solway are referred to as Milefortlets.

Purpose of construction

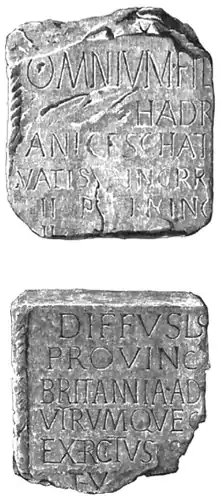

Hadrian's Wall was probably planned before Hadrian's visit to Britain in 122. According to restored sandstone fragments found in Jarrow which date from 118 or 119, it was Hadrian's wish to keep "intact the empire", which had been imposed on him via "divine instruction".[17]

One comment on the military purpose of the wall was that, "if there are troublesome tribes to the north, and you want to keep them out, you build a strong defensive wall".[2] The Historia Augusta also states that Hadrian was the first to build a wall 80 miles (130 km) from sea to sea to separate the barbarians from the Romans.[2] However, this reasoning may not entirely explain all the various motivations Hadrian could have had in mind when commissioning the wall's construction.[2]

On Hadrian's accession to the imperial throne in 117, there was unrest and rebellion in Roman Britain and from the peoples of various conquered lands across the Empire, including Egypt, Judea, Libya and Mauretania.[17] These troubles may have influenced his plan to construct the wall, as well as his construction of frontier boundaries now known as limes in other areas of the Empire, such as the Limes Germanicus in modern-day Germany. Scholars disagree over how much of a threat the inhabitants of northern Britain really presented to the Romans, and whether there was any economic advantage in defending and garrisoning a fixed line of defences like the wall, rather than conquering and annexing what has become Northumberland and the Scottish Lowlands and then defending the territory with a looser arrangement of forts.[17]

Besides a defensive structure made to keep people out, the wall also kept people within the Roman province.[2] Since the Romans had control over who was allowed in and out of the empire, the wall was invaluable in controlling trading and the economy.[2] The wall also had a psychological impact:

For nearly three centuries, until the end of Roman rule in Britain in 410 AD, Hadrian's Wall was the clearest statement of the might, resourcefulness, and determination of an individual emperor and of his empire.[2]

The Wall also provided years of work for thousands of soldiers who were responsible for building and maintaining the structure, which gave the further benefit of preventing any boredom for the soldiers.[2]

It would appear that the wall's primary purpose was as a physical barrier to slow the crossing of raiders and people intent on getting into the empire for destructive or plundering purposes.[2]

"And so, having reformed the army quite in the manner of a monarch, he set out for Britain, and there he corrected many abuses and was the first to construct a wall, eighty miles in length, which was to separate the barbarians from the Romans." Historia Augusta, Life of Hadrian 11.2.

Hadrian's Wall was not only a defensive structure but also a symbolic statement of Rome's imperial power marking the border between the so called civilized world and the unconquered barbarian wilderness. As the British archaeologist Neil Faulkner explains, "the wall, like other great Roman frontier monuments was as much a propaganda statement as a functional facility".[18]

It may be that it was not a last-stand type of defensive line, but, instead, an observation point that could alert Romans of an incoming attack and act as a deterrent to slow down enemy forces so that additional troops could arrive for support.[2] This view is supported by another defensive measure frequently found on the berm or flat area in front of the wall: pits or holes known as cippi pits[19] which held branches or small tree trunks entangled with sharpened branches (these were the 'cippi').[2] The use of such thorns and sharpened stakes was clearly an anti-personnel measure, and might be thought of as the Roman equivalent of barbed wire.

Once its construction was finished, there is some evidence that Hadrian's Wall was covered in plaster and then whitewashed: its shining surface would have reflected the sunlight and been visible for miles around.[17]

Construction

Hadrian ended his predecessor Trajan's policy of expanding the empire and instead focused on defending the current borders, namely at the time Britain.[2] Like Augustus, Hadrian believed in exploiting natural boundaries such as rivers for the borders of the empire, for example the Euphrates, Rhine and Danube.[2] Britain, however, did not have any natural boundaries that could serve this purpose – to divide the province controlled by the Romans from the Celtic tribes in the north.[2]

With construction starting in 122,[20] the entire length of the wall was built with an alternating series of forts, each housing 600 men, and manned milecastles, operated by "between 12 and 20 men".[2]

It took six years to build most of Hadrian's Wall with the work coming from three Roman legions – the Legio II Augusta, Legio VI Victrix, and Legio XX Valeria Victrix, totalling 15,000 soldiers, plus some members of the Roman fleet.[2] The building of the wall was not out of the area of expertise for the soldiers; some would have trained to be surveyors, engineers, masons, and carpenters.[2]

"Broad Wall" and "Narrow Wall"

R. G. Collingwood cited evidence for the existence of a broad section of the wall and conversely a narrow section.[21] He argued that plans changed during construction of the wall and its overall width was reduced.[21]

Broad sections of the wall are around nine and a half feet (2.9 metres) wide with the narrow sections two feet (60 centimetres) thinner, around seven and a half feet (2.3 metres) wide.[21] The narrow sections were found to be built upon broad foundations.[21] Based on this evidence, Collingwood concluded that the wall was originally due to be built between present-day Newcastle and Bowness, with a uniform width of ten Roman feet, all in stone.[21] In the end, only three-fifths of it was built from stone and the remaining part in the west was a turf wall, later rebuilt in stone.[21] Plans possibly changed due to a lack of resources.[21]

In an effort to preserve resources further, the eastern half's width was therefore reduced from the original ten Roman feet to eight, with the remaining stones from the eastern half used for around 5 miles (8 kilometres) of the turf wall in the west.[21][14] This reduction from the original ten Roman feet to eight, created the so-called "Narrow Wall".[14]

The Vallum

Just south of the wall there is a ten-foot (3-metre) deep, ditch-like construction with two parallel mounds running north and south of it, known as the Vallum.[21] The Vallum and the wall run more or less in parallel for almost the entire length of the wall, except between the forts of Newcastle and Wallsend at the east end, where the Vallum may have been considered superfluous as a barrier on account of the close proximity of the River Tyne. The twin track of the wall and Vallum led many 19th-century thinkers to note and ponder their relation to one another.[21]

Some evidence appears to shows that the route of the wall was shifted to avoid the Vallum, possibly pointing to the Vallum being an older construction.[21] R. G. Collingwood therefore asserted in 1930 that the Vallum was built before the wall in its final form.[21] Collingwood also questioned whether the Vallum was an original border built before the wall.[21] Based on this, the wall could be viewed as a new, replacement border, built to strengthen the Romans' definition of their territory.[21]

In 1936, further research suggested that the Vallum could not have been built before the wall because the Vallum avoided one of the Wall's milecastles.[21] This new discovery was continually supported by more evidence, strengthening the idea that there was a simultaneous construction of the Vallum and the wall.[21]

Other evidence still pointed in other, slightly different directions. Evidence shows that the Vallum preceded sections of the Narrow Wall specifically; to account for this discrepancy, Couse suggests that either construction of the Vallum began with the Broad Wall, or it began when the Narrow Wall succeeded the Broad Wall but proceeded more quickly than that of the Narrow Wall.[21]

Turf wall

From Milecastle 49 to the western terminus of the wall at Bowness-on-Solway, the curtain wall was originally constructed from turf, possibly due to the absence of limestone for the manufacture of mortar.[22] Subsequently, the Turf Wall was demolished and replaced with a stone wall. This took place in two phases; the first (from the River Irthing to a point west of Milecastle 54), during the reign of Hadrian, and the second following the reoccupation of Hadrian's Wall after the abandonment of the Antonine Wall (though it has also been suggested that this second phase took place during the reign of Septimius Severus). The line of the new stone wall follows the line of the turf wall, apart from the stretch between Milecastle 49 and Milecastle 51, where the line of the stone wall is slightly further to the north.[22]

In the stretch around Milecastle 50TW, it was built on a flat base with three to four courses of turf blocks.[23] A basal layer of cobbles was used westwards from Milecastle 72 (at Burgh-by-Sands) and possibly at Milecastle 53.[24] Where the underlying ground was boggy, wooden piles were used.[22]

At its base, the now-demolished turf wall was 6 metres (20 feet) wide, and built in courses of turf blocks measuring 46 cm (18 inches) long by 30 cm (12 inches) deep by 15 cm (6 inches) high, to a height estimated at around 3.66 metres (12.0 feet). The north face is thought to have had a slope of 75%, whereas the south face is thought to have started vertical above the foundation, quickly becoming much shallower.[22]

Standards

Above the stone curtain wall's foundations, one or more footing courses were laid. Offsets were introduced above these footing courses (on both the north and south faces), which reduced the wall's width. Where the width of the curtain wall is stated, it is in reference to the width above the offset. Two standards of offset have been identified: Standard A, where the offset occurs above the first footing course, and Standard B, where the offset occurs after the third (or sometimes fourth) footing course.[25]

Garrison

It is thought that following construction, and when fully manned, almost 10,000 soldiers were stationed on Hadrian's Wall, made up not of the legions who built it but by regiments of auxiliary infantry and cavalry drawn from the provinces.[2]

Following from this, David Breeze laid out the two basic functions for soldiers on or around Hadrian's Wall.[26] Breeze says that soldiers who were stationed in the forts around the wall had the primary duty of defence; at the same time, the troops in the milecastles and turrets had the responsibility of frontier control.[26] Evidence, as Breeze says, for soldiers stationed in forts is far more pronounced than the ones in the milecastles and turrets.[26]

Breeze discusses three theories about the soldiers on Hadrian's Wall. One, these soldiers who manned the milecastles and turrets on the wall came from the forts near it; two, regiments from auxiliaries were specifically chosen for this role; or three, "a special force" was formed to man these stations.[26]

Breeze comes to the conclusion that through all the inscriptions gathered there were soldiers from three, or even four, auxiliary units at milecastles on the wall.[26] These units were "cohors I Batavorum, cohors I Vardullorum, an un-numbered Pannonian cohort, and a duplicarius from Upper Germany".[26] Breeze adds that there appears to have been some legionaries as well at these milecastles.[26]

Breeze also continues saying that evidence is "still open on whether" soldiers who manned the milecastles were from nearby forts or were specifically chosen for this task, and further adds that "the balance [of evidence] perhaps lies towards the latter".[26] A surprise for Breeze is that "soldiers from the three British legions" outnumbered the auxiliaries, which goes against the assertion "that legionaries would not be used on such detached duties".[26]

Further information on the garrisoning of the wall has been provided by the discovery of the Vindolanda tablets just to the south of Hadrian's Wall, such as the record of an inspection on 18 May 92 or 97, when only 456 of the full quota of 756 Belgae troops were present, the rest being sick or otherwise absent.[27]

After Hadrian

After Hadrian's death in 138, the new emperor, Antoninus Pius, left the wall occupied in a support role, essentially abandoning it. He began building the Antonine Wall about 160 kilometres (100 mi) north, across the isthmus running west-south-west to east-north-east. This turf wall ran 40 Roman miles, or about 60.8 km (37.8 mi), and had more forts than Hadrian's Wall. This area later became known as the Scottish Lowlands, sometimes referred to as the Central Belt or Central Lowlands.

Antoninus was unable to conquer the northern tribes, so when Marcus Aurelius became emperor, he abandoned the Antonine Wall and reoccupied Hadrian's Wall as the main defensive barrier in 164. In 208–211, the Emperor Septimius Severus again tried to conquer Caledonia and temporarily reoccupied the Antonine Wall. The campaign ended inconclusively and the Romans eventually withdrew to Hadrian's Wall. The early historian Bede (AD 672/73–735), following Gildas, wrote (circa AD 730):

[the departing Romans] thinking that it might be some help to the allies [Britons], whom they were forced to abandon, constructed a strong stone wall from sea to sea, in a straight line between the towns that had been there built for fear of the enemy, where Severus also had formerly built a rampart.

— Bede, Historia Ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, Book I Chapter 12

Bede obviously identified Gildas's stone wall as Hadrian's Wall (built in the 120s) and he would appear to have believed that the ditch-and-mound barrier known as the Vallum (just to the south of, and contemporary with, Hadrian's Wall) was the rampart constructed by Severus. Many centuries would pass before just who built what became apparent.[29]

In the same passage, Bede describes Hadrian's Wall as follows: "It is eight feet in breadth, and twelve in height; and, as can be clearly seen to this day, ran straight from east to west." Bede by his own account[30] lived his whole life at Jarrow, just across the River Tyne from the eastern end of the Wall at Wallsend, so as he indicates, he would have been very familiar with the Wall. What he does not say is whether there was a walkway along the top of the wall. It might be thought likely that there was, but if so it no longer exists.

In the late 4th century, barbarian invasions, economic decline and military coups loosened the Empire's hold on Britain. By 410, the estimated end of Roman rule in Britain, the Roman administration and its legions were gone and Britain was left to look to its own defences and government. Archaeologists have revealed that some parts of the wall remained occupied well into the 5th century. It has been suggested that some forts continued to be garrisoned by local Britons under the control of a Coel Hen figure and former dux. Hadrian's Wall fell into ruin and over the centuries the stone was reused in other local buildings. Enough survived in the 7th century for spolia from Hadrian's Wall (illustrated at right) to find its way into the construction of St Paul's Church in Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Abbey, where Bede was a monk. It was presumably incorporated before the setting of the church's dedication stone, still to be seen in the church, dated 23 April 685.[31]

The wall fascinated John Speed, who published a set of maps of England and Wales by county at the start of the 17th century. He described it as "the Picts Wall" (or "Pictes"; he uses both spellings). A map of Newecastle (sic), drawn in 1610 by William Matthew, described it as "Severus' Wall", mistakenly giving it the name ascribed by Bede to the Vallum. The maps for Cumberland and Northumberland not only show the wall as a major feature, but are ornamented with drawings of Roman finds, together with, in the case of the Cumberland map, a cartouche in which he sets out a description of the wall itself.

Preservation by John Clayton

Much of the wall has now disappeared. Long sections of it were used for roadbuilding in the 18th century,[32] especially by General Wade to build a military road (most of which lies beneath the present day B6318 "Military Road") to move troops to crush the Jacobite rising of 1745. The preservation of much of what remains can be credited to the antiquarian John Clayton. He trained as a lawyer and became town clerk of Newcastle in the 1830s. He became enthusiastic about preserving the wall after a visit to Chesters. To prevent farmers taking stones from the wall, he began buying some of the land on which the wall stood. In 1834, he started purchasing property around Steel Rigg near Crag Lough. Eventually, he controlled land from Brunton to Cawfields. This stretch included the sites of Chesters, Carrawburgh, Housesteads, and Vindolanda. Clayton carried out excavation at the fort at Cilurnum and at Housesteads, and he excavated some milecastles.

Clayton managed the farms he had acquired and succeeded in improving both the land and the livestock. He used the profits from his farms for restoration work. Workmen were employed to restore sections of the wall, generally up to a height of seven courses. The best example of the Clayton Wall is at Housesteads. After Clayton's death, the estate passed to relatives and was soon lost to gambling. Eventually, the National Trust began acquiring the land on which the wall stands. At Wallington Hall, near Morpeth, there is a painting by William Bell Scott, which shows a centurion supervising the building of the wall. The centurion has been given the face of John Clayton (above right).

Later discoveries

In 2021 workers for Northumbrian Water found a previously undiscovered 3 metres (9.8 ft) section of the wall while repairing a water main in central Newcastle upon Tyne. The company announced that the pipe would be "angled to leave a buffer around the excavated trench".[33][34]

World Heritage Site

Hadrian's Wall was declared a World Heritage Site in 1987, and in 2005 it became part of the transnational "Frontiers of the Roman Empire" World Heritage Site, which also includes sites in Germany.[35]

Tourism

Although Hadrian's Wall was declared a World Heritage Site in 1987, it remains unguarded, enabling visitors to climb and stand on the wall, although this is not encouraged, as it could damage the historic structure. On 13 March 2010, a public event Illuminating Hadrian's Wall took place, which saw the route of the wall lit with 500 beacons. On 31 August and 2 September 2012, there was a second illumination of the wall as a digital art installation called "Connecting Light", which was part of the London 2012 Festival. In 2018, the organisations which manage the Great Wall of China and Hadrian's Wall signed an agreement to collaborate for the growth of tourism and for historical and cultural understanding of the monuments.[36]

Roman-period names

Hadrian's Wall was known in the Roman period as the vallum (wall) and the discovery of the Staffordshire Moorlands Pan in Staffordshire in 2003 has thrown further light on its name. This copper alloy pan (trulla) from the 2nd century, is inscribed with a series of names of Roman forts along the western sector of the wall: MAIS [Bowness-on-Solway] COGGABATA [Drumburgh] VXELODVNVM [Stanwix] CAMBOGLANNA [Castlesteads]. This is followed by RIGORE VALI AELI DRACONIS. Hadrian's family name was Aelius, and the most likely reading of the inscription is Valli Aelii (genitive), Hadrian's Wall, suggesting that the wall was called by the same name by contemporaries. However, another possibility is that it refers to the personal name Aelius Draco.[39][40]

Forts

| Hadrian's Wall Route | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sources[41] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Latin and Romano-Celtic names of all of the Hadrian's Wall forts are known, from the Notitia Dignitatum and other evidence such as inscriptions:

- Segedunum (Wallsend)

- Pons Aelius (Newcastle upon Tyne)

- Condercum (Benwell Hill)

- Vindobala (Rudchester)[42]

- Hunnum (Halton Chesters)[42]

- Cilurnum (Chesters aka Walwick Chesters)[42]

- Procolita (Carrowburgh)

- Vercovicium (Housesteads)

- Aesica (Great Chesters)[42]

- Magnis (Carvoran)

- Banna (Birdoswald)

- Camboglanna (Castlesteads)

- Uxelodunum (Stanwix. Also known as Petriana)

- Aballava (Burgh-by-Sands)

- Coggabata (Drumburgh)

- Mais (Bowness-on-Solway)

Turrets on the wall include:

- Leahill Turret

- Denton Hall Turret

Outpost forts beyond the wall include:

- Habitancum (Risingham)

- Bremenium (High Rochester)[42]

- Fanum Cocidi (Bewcastle) (north of Birdoswald)

- Ad Fines (Chew Green)[43]

Supply forts behind the wall include:

- Alauna (Maryport)

- Arbeia (South Shields)

- Coria (Corbridge)

- Epiacum (Whitley Castle near Alston)

- Vindolanda (Little Chesters or Chesterholm)[42]

- Vindomora (Ebchester)[42]

In popular culture

Books

- The Eagle of the Ninth is a celebrated children's novel by Rosemary Sutcliff, published in 1954. It tells the story of a young Roman officer venturing north beyond Hadrian's Wall in search of the missing Eagle standard of the lost Ninth Legion. It was inspired by the bronze Silchester eagle found in 1866. The book itself inspired the 2011 film The Eagle.

- The Jim Shepard short story collection Like You'd Understand Anyway (2007) includes a story titled "Hadrian's Wall" which is an imagined account of a clerk living and working during the wall's construction.[44]

- Nobel Prize-winning English author Rudyard Kipling contributed to the popular image of the "Great Pict Wall" in his short stories about Parnesius, a Roman legionary who defended the wall against the Picts. These stories are part of the Puck of Pook's Hill anthology, published in 1906.[45]

- American author George R. R. Martin has acknowledged that Hadrian's Wall was the inspiration for the Wall in his best-selling series A Song of Ice and Fire, dramatised in the fantasy TV series Game of Thrones, in which the wall is also in the north of its country and stretches from coast to coast.[46]

- In M. J. Trow's fictional Britannia series, Hadrian's Wall is the central location, and Coel Hen and Padarn Beisrudd are portrayed as limitanei (frontier soldiers).[47]

- Hadrian's Wall by Adrian Goldsworthy is a short history of the wall.[48]

Films

- The 1991 American romantic action adventure film Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves uses Sycamore Gap as a location.[49]

- The 2011 action drama film The Eagle tells the story of a young Roman officer setting out across Hadrian's Wall into the uncharted highlands of Caledonia to recover the lost Roman eagle standard of the Ninth Legion. The 2010 film Centurion tells a similar story.

- The wall has also been featured as a major focal point of the 2004 King Arthur in which one of the primary gates is opened for the first time since its construction to allow Arthur and his knights passage into the north for their quest. The climactic Battle of Badon between the Britons led by Arthur and his knights, and the Saxons led by Cerdic and his son Cynric are set just inside the wall.

Music

- The opening track from Maxim's first solo album Hell's Kitchen is named "Hadrian's Wall".[50]

Television

Poetry

- The English poet W. H. Auden wrote a script for a BBC radio documentary called Hadrian's Wall, which was broadcast on the BBC's north-eastern Regional Programme in 1937. Auden later published a poem from the script, "Roman Wall Blues", in his book Another Time. The poem is a brief monologue spoken in the voice of a lonely Roman soldier stationed at the wall.[52]

Video games

- Hadrian's Wall appears in Assassin's Creed Valhalla. The site can be visited by protagonist Eivor of the Raven Clan during the 870s.[53]

Gallery

Poltross Burn, Milecastle 48, which was built on a steep slope

Poltross Burn, Milecastle 48, which was built on a steep slope Sycamore Gap (the "Robin Hood Tree", so called because it appears in the film Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves)[56]

Sycamore Gap (the "Robin Hood Tree", so called because it appears in the film Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves)[56] Hadrian's Wall with sheep

Hadrian's Wall with sheep Hadrian's Wall near Birdoswald Fort, known to the Romans as Banna, with a man spraying weedkiller to reduce biological weathering to the stones

Hadrian's Wall near Birdoswald Fort, known to the Romans as Banna, with a man spraying weedkiller to reduce biological weathering to the stones The Staffordshire Moorlands Pan, which may provide the ancient name of Hadrian's Wall (it reads in part VALI AELI, ie. the Wall of Hadrian, using his family name of Aelius)

The Staffordshire Moorlands Pan, which may provide the ancient name of Hadrian's Wall (it reads in part VALI AELI, ie. the Wall of Hadrian, using his family name of Aelius) The remains of Castle Nick, Milecastle 39, near Steel Rigg, between Housesteads and The Sill Visitor Centre for the Northumberland National Park at Once Brewed

The remains of Castle Nick, Milecastle 39, near Steel Rigg, between Housesteads and The Sill Visitor Centre for the Northumberland National Park at Once Brewed The remains of the southern granary at Housesteads, showing under-floor pillars to assist ventilation

The remains of the southern granary at Housesteads, showing under-floor pillars to assist ventilation

See also

- Danevirke

- English Heritage properties

- Gask Ridge

- Hadrianic Society

- History of Cumbria

- History of Northumberland

- History of Scotland

- List of walls

- Offa's Dyke

- Scots' Dike

- Via Hadriana

References

- "Hadrian's Wall: The Facts". Visit Hadrian's Wall. 8 March 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- Lobell, Jarrett A (2017). "The Wall at the End of the Empire". Archaeology. 70 (3): 26–35.

- "Obituary: Brian Dobson". The Daily Telegraph. London. 21 September 2012. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- "Hadrian's Wall: A horde of ancient treasures make for a compelling new Cumbrian exhibition". The Independent. 8 November 2016.

- "More than 25,000 people see Hadrian's Wall lit up". BBC. 8 November 2016.

- "Hadrian's Wall". English Heritage. 22 July 2004. Archived from the original on 22 July 2004.

- Rohl, Darrell, Jesse. "More than a Roman Monument: A Place-centred Approach to the Long-term History and Archaeology of the Antonine Wall" (PDF). Durham Theses. Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online ref: 9458. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- "Wall gains World Heritage status" BBC News. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- "Frontiers of the Roman Empire". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- English Heritage. 30 Surprising Facts About Hadrian's Wall Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- Financial Times. Borders held dear to English and Scots Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- History.com. Hadrian's Wall. Retrieved 27 August 2020

- "Definition of Roman mile in American English". Collins Dictionary. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- Tomlin, R. S. O. (2018). Britannia Romana: Roman Inscriptions & Roman Britain. Oxford: Oxbow Books. pp. 100–102.

- Breeze, David J (November 2006). Handbook to the Roman Wall (14th – November 2006 ed.). Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne (1934). ISBN 978-0-901082-65-7.

- Breeze, D.J. (2004). "Roman military sites on the Cumbrian coast". In R.J.A. Wilson; I.D Caruana (eds.). Romans on the Solway : essays in honour of Richard Bellhouse. CWAAS Extra Series. Vol. 31. Kendal: Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society on behalf of the Trustees of the Senhouse Roman Museum, Maryport. pp. 66–94. ISBN 978-1873124390.

- Anthony Everitt, Hadrian and the Triumph of Rome (2009), Random House, Inc, 448 pages; ISBN 0-8129-7814-5.

- Faulkner, Neil (17 February 2011). "The Official Truth: Propaganda in the Roman Empire". BBC.

- Julius Caesar gives a detailed description of the making of cippi pits in Book VII, Chapter 73 of his Commentarii de Bello Gallico, as part of his account of his siege of Vercingetorix in Alesia.

- Breeze, D.J.; Dobson, B. (2000). Hadrian's Wall (4 ed.). London: Penguin Books. p. 86. ISBN 978-0140271829.

- Couse, G.S. (December 1990). "Collingwood's Detective Image of the Historian and the Study of Hadrian's Wall". History and Theory. 29 (4): 57–77. doi:10.2307/2505164. JSTOR 2505164.

- Breeze, David J (1934). Handbook to the Roman Wall (14th – November 2006 ed.). Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne. pp. 55–62. ISBN 978-0-901082-65-7.

- Simpson, F G; Richmond, I A; St Joseph, K (1935), "Report of the Cumberland Excavation Committee for 1934", Transactions of the Cumberland & Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society, new series, 35: 220–32

- Simpson, F G; MacIntyre, J (1933), "Report of the Cumberland Excavation Committee for 1932", Transactions of the Cumberland & Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society, new series, 33: 262–70

- Breeze, David J. (November 2006) [1934]. Handbook to the Roman Wall (14th ed.). Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-901082-65-7.

- Breeze, David J. (2003). "Auxiliaries, Legionaries, and the Operation of Hadrian's Wall". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. Supplement. 46 (81): 147–151. doi:10.1111/j.2041-5370.2003.tb01980.x.

- Simon Schama (2000). A History of Britain. BBC Worldwide Ltd. pp. 34–37. ISBN 978-0-563-38497-7.

- RIB 1051. Imperial dedication, romaninscriptionsofbritain.org

- "Wall of Severus". Dot-domesday.me.uk. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- Bede, Historia Ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, Book 5 Chapter 24, "I have spent all the remainder of my life in this monastery."

- The Buildings of England: County Durham by Nikolaus Pevsner and Elizabeth Williamson (1985 edition), p.338. The inscription reads: DEDICATIO BASILICAE SCI PAVLI VIIII KL MAI ANNO XV ECFRIDI REG CEOLFRIDI ABB EIVSDEMQ Q ECCLES DO AVCTORE CONDITORIS ANNO IIII. This translates as "The dedication of the church of St Paul on the ninth before the kalends of May [23 April] in the fifteenth year of King Ecgfrith and the fourth year of Ceolfrith, abbot, and with God's help the founder of this church". (St Paul's Church Jarrow, undated guidebook by Peter Hiscock, p.4.)

- "Hadrian's Wall". English-lakes.com. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- "Hadrian's Wall section found under Newcastle street". BBC News. 11 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- "Hadrian's Wall discovered underneath one of Newcastle's busiest streets". Northumbrian Water Group. 10 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Frontiers of the Roman Empire". Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- "Two historic structures in wall-to-wall collaboration". The Telegraph. 24 January 2018. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019.

- "Hadrian's Wall Path". National Trails. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- "Every Footstep Counts – The Trail's Country Code". Hadrians Wall Path National Trail. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- "The Staffordshire Moorlands Pan". British Museum. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- Hodgson, Hadrian's Wall, p. 23

- "The Notitia Dignitatum in Britain" (PDF). Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- The suffix "chester" reflects the presence of a Roman castra.

- "GENUKI: The National Gazetteer of Great Britain and Ireland (1868) – Northumberland". Genuki.bpears.org.uk. 3 August 2010. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- "Like You'd Understand, Anyway (review)". Kirkus Reviews. 25 September 2007. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- Mackenzie, Donald (2 August 2005). "On the Great Wall". Kipling Society. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- Martin, George R. R. "A Conversation With George R. R. Martin". The SF Site. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- Trow, M. J. (2014). "The Wall (Britannia #1)". Good Reads. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- Hadrian's Wall, Adrian Goldsworthy (2018) – Google Books

- "Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991) Filming & Production". IMDb. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- "MAXIM : HELLS KITCHEN - the album, scans and info". Nekozine.co.uk. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- "Modern Marvels (1993-) Hadrian's Wall". IMDb. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- "Roman Wall Blues". Kids of the Wild. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- "Assassins Creed Valhalla: Is There Anybody Out There trophy – how to unlock?". Game Pressure. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- "Be a Roman General in Hadrian's Wall". GeekTyrant. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- "2022 American Tabletop Award Winners". The American Tabletop Awards. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- Sycamore Gap, a section of the wall between two crests just east of Milecastle 39, is locally known as the "Robin Hood Tree" for its use in the 1991 film Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991).

Sources

- Birley, A.R. (1963). Hadrians Wall Illustrated Guide. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office (HMSO).

- Burton, Anthony. Hadrian's Wall Path. 2004. Aurum Press Ltd. ISBN 1-85410-893-X.

- Chaichian, Mohammad. 2014. "Hadrian's Wall: An Ill-Fated strategy for Tribal Management in Roman Britain", in Empires and Walls: Globalization, Migration, and Colonial Domination (Brill, pp. 23–52). https://www.amazon.com/Empires-Walls-Globalization-Migration-Domination/dp/1608464229.

- Davies, Hunter. A Walk along the Wall, 1974. Weidenfeld & Nicolson: London ISBN 0 297 76710 0.

- de la Bédoyère, Guy. Hadrian's Wall: A History and Guide. Stroud: Tempus, 1998. ISBN 0-7524-1407-0.

- England's Roman Frontier: Discovering Carlisle and Hadrian's Wall Country. Hadrian's Wall Heritage Ltd and Carlisle Tourism Partnership. 2010.

- Forde-Johnston, James L. Hadrian's Wall. London: Michael Joseph, 1978. ISBN 0-7181-1652-6.

- Hadrian's Wall Path (map). Harvey, 12–22 Main Street, Doune, Perthshire FK16 6BJ. harveymaps.co.uk

- Higgins, Charlotte (2014). "Chapter Seven: Hadrian's Wall". Under Another Sky: Journeys in Roman Britain. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-099552-09-3.

- Hodgson, Nick (2017). Hadrian's Wall. Marlborough, UK: Robert Hale. ISBN 978-0-7198-1815-8.

- Moffat, Alistair, The Wall. 2008. Birlinn Limited Press. ISBN 1-84158-675-7.

- Shanks, Michael (2012). "'Let me tell you about Hadrian's Wall ...' Heritage, Performance, Design".

- Speed, John – A set of Speed's maps were issued bound in a single volume in 1988 in association with the British Library and with an introduction by Nigel Nicolson as The Counties of Britain: A Tudor Atlas by John Speed.

- Tomlin, R. S. O., "Inscriptions" in Britannia (2004), vol. xxxv, pp. 344–5 (the Staffordshire Moorlands cup naming the Wall).

- Wilson, Roger J. A., A Guide to the Roman Remains in Britain. London: Constable & Company, 1980; ISBN 0-09-463260-X.

External links

- In Our Time Radio series with Greg Woolf, Professor of Ancient History at the University of St Andrews, David Breeze, Former Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments for Scotland and Visiting Professor of Archaeology at the University of Durham and Lindsay Allason-Jones OBE, FSA, FSA Scot, Former Reader in Roman Material Culture at the University of Newcastle

- Hadrian's Wall on the Official Northumberland Visitor website

- Hadrian's Wall Discussion Forum

- UNESCO Frontiers of the Roman Empire

- News on the Wall path

- English Lakes article

- iRomans—website with interactive map of Cumbrian section of Hadrian Wall

- Well illustrated account of sites along Hadrian's Wall