Haitian Vodou

Haitian Vodou[lower-alpha 1] is an African diasporic religion that developed in Haiti between the 16th and 19th centuries. It arose through a process of syncretism between several traditional religions of West and Central Africa and Roman Catholicism. There is no central authority in control of the religion and much diversity exists among practitioners, who are known as Vodouists, Vodouisants, or Serviteurs.

Vodou revolves around spirits known as lwa. Typically deriving their names and attributes from traditional West and Central African divinities, they are equated with Roman Catholic saints. The lwa divide up into different groups, the nanchon ("nations"), most notably the Rada and the Petwo. Various myths and stories are told about these lwa, which are regarded as subservient to a transcendent creator deity, Bondye. This theology has been labelled both monotheistic and polytheistic. An initiatory tradition, Vodouists usually meet to venerate the lwa in an ounfò (temple), run by an oungan (priest) or manbo (priestess). A central ritual involves practitioners drumming, singing, and dancing to encourage a lwa to possess one of their members and thus communicate with them. Offerings to the lwa include fruit, liquor, and sacrificed animals. Offerings are also given to the spirits of the dead. Several forms of divination are utilized to decipher messages from the lwa. Healing rituals and the preparation of herbal remedies and talismans also play a prominent role.

Vodou developed among Afro-Haitian communities amid the Atlantic slave trade of the 16th to 19th centuries. Its structure arose from the blending of the traditional religions of those enslaved West and Central Africans, among them Yoruba, Fon, and Kongo, who had been brought to the island of Hispaniola. There, it absorbed influences from the culture of the French colonialists who controlled the colony of Saint-Domingue, most notably Roman Catholicism but also Freemasonry. Many Vodouists were involved in the Haitian Revolution of 1791 to 1801 which overthrew the French colonial government, abolished slavery, and transformed Saint-Domingue into the republic of Haiti. The Roman Catholic Church left for several decades following the Revolution, allowing Vodou to become Haiti's dominant religion. In the 20th century, growing emigration spread Vodou abroad. The late 20th century saw growing links between Vodou and related traditions in West Africa and the Americas, such as Cuban Santería and Brazilian Candomblé, while some practitioners influenced by the Négritude movement have sought to remove Roman Catholic influences.

Most Haitians practice both Vodou and Roman Catholicism, seeing no contradiction in pursuing the two different systems simultaneously. Smaller Vodouist communities exist elsewhere, especially among the Haitian diaspora in the United States. Both in Haiti and abroad Vodou has spread beyond its Afro-Haitian origins and is practiced by individuals of various ethnicities. Vodou has faced much criticism through its history, having repeatedly been described as one of the world's most misunderstood religions.

Definitions and terminology

Vodou is a religion.[6] More specifically it has been characterised as Haiti's "national religion"[7] and as an Afro-Haitian religion,[8] as well as a "traditional religion"[9] and a "folk religion."[10] Its main structure derives from the African traditional religions of West and Central Africa which were brought to Haiti by enslaved Africans between the 16th and 19th centuries.[11] On the island, these African religions mixed with the iconography of European-derived traditions such as Roman Catholicism and Freemasonry,[12] taking the form of Vodou around the mid-18th century.[13] In combining varied influences, Vodou has often been described as syncretic,[14] or a "symbiosis",[15] a religion exhibiting diverse cultural influences.[16]

Despite its older influences, Vodou represented "a new religion",[17] "a creolized New World system",[18] one that differs in many ways from African traditional religions.[19] One of the most complex of the African diasporic traditions,[20] the scholar Leslie Desmangles called it an "African-derived tradition",[21] Ina J. Fandrich termed it a "neo-African religion",[22] and Markel Thylefors called it an "Afro-Latin American religion".[23] Owing to their shared origins in West African traditional religion, Vodou has been characterized as a "sister religion" of Cuban Santería and Brazilian Candomblé.[24]

In English, Vodou's practitioners are termed Vodouists,[25] or—in French and Haitian Creole—Vodouisants[26] or Vodouyizan.[27] Another term for adherents is sèvitè (serviteurs, "devotees"),[28] reflecting their self-description as people who sèvi lwa ("serve the lwa"), the supernatural beings that play a central role in Vodou.[29] Lacking any central institutional authority,[30] Vodou has no single leader.[31] It thus has no orthodoxy,[32] no central liturgy,[33] nor a formal creed.[34] Developing over the course of several centuries,[35] it has changed over time.[36] It displays variation at both the regional and local level[37]—including variation between Haiti and the Haitian diaspora[38]—as well as among different congregations.[39] It is practiced domestically, by families on their land, but also by congregations meeting communally,[40] with the latter termed "temple Vodou".[41]

.jpg.webp)

In Haitian culture, religions are not generally deemed totally autonomous, with many Haitians practicing both Vodou and Roman Catholicism.[42] Vodouists usually regard themselves as Roman Catholics.[43] In Haiti, Vodouists have also practiced Mormonism[44] and Freemasonry,[45] while abroad they have involved themselves in Santería[46] and modern Paganism.[47] Vodou has also absorbed elements from other contexts; in Cuba, some Vodouists have adopted elements from Spiritism.[48] Influenced by the Négritude movement, other Vodouists have sought to remove Roman Catholic and other European influences from their practice of Vodou.[49]

The ritual language used in Vodou is termed langaj.[50] Many of these terms—including the word Vodou itself[11]—derive from the Fon language of West Africa.[51] First recorded in the 1658 Doctrina Christiana,[52] the Fon word Vôdoun was used in the West African kingdom of Dahomey to signify a spirit or deity.[53] In Haitian Creole, Vodou came to designate a specific style of dance and drumming,[54] before outsiders to the religion adopted it as a generic term for much Afro-Haitian religion.[55] The word Vodou now encompasses "a variety of Haiti's African-derived religious traditions and practices",[56] incorporating "a bundle of practices that practitioners themselves do not aggregate".[57] Vodou is thus a term primarily used by scholars and outsiders to the religion;[57] many practitioners describe their belief system with the term Ginen, which especially denotes a moral philosophy and ethical code regarding how to live and to serve the spirits.[38]

Vodou is the common spelling for the religion among scholars, in official Haitian Creole orthography, and by the United States Library of Congress.[58][59] Some scholars use the spellings Vodoun or Vodun,[60] while in French the spellings vaudou[61] or vaudoux also appear.[62] The spelling Voodoo, once common, is now generally avoided by practitioners and scholars when referring to the Haitian religion.[63] This is both to avoid confusion with Louisiana Voodoo, a related but distinct tradition,[64] and to distinguish it from the negative connotations that the term Voodoo has in Western popular culture.[65]

Beliefs

Bondye and the lwa

Teaching the existence of single supreme God,[66] Vodou has been described as monotheistic.[67] Believed to have created the universe,[68] this entity is called Bondye or Bonié,[69] a term deriving from the French Bon Dieu ("Good God").[70] Another term used is the Gran Mèt,[71] which derives from Freemasonry.[45] For Vodouists, Bondye is seen as the ultimate source of power,[72] deemed responsible for maintaining universal order.[73] Bondye is also regarded as remote and transcendent,[74] not involving itself in human affairs;[75] there is thus little point in approaching it directly.[76] Haitians will frequently use the phrase si Bondye vle ("if Bondye wishes"), suggesting a belief that all things occur in accordance with this divinity's will.[77] While Vodouists often equate Bondye with the Christian God,[78] Vodou does not incorporate belief in a powerful antagonist that opposes the supreme being akin to the Christian notion of Satan.[79]

Vodou has also been characterized as polytheistic.[76] It teaches the existence of beings known as the lwa (or loa),[80] a term varyingly translated into English as "spirits", "gods", or "geniuses".[81] These lwa are also known as the mystères, anges, saints, and les invisibles,[28] and are sometimes equated with the angels of Christian cosmology.[78] Vodou teaches that there are over a thousand lwa.[82] The lwa can offer help, protection, and counsel to humans, in return for ritual service.[83] They are regarded as the intermediaries of Bondye,[84] and as having wisdom that is useful for humans,[85] although they are not seen as moral exemplars which practitioners should imitate.[86] Each lwa has its own personality,[28] and is associated with specific colors,[87] days of the week,[88] and objects.[28] The lwa can be either loyal or capricious in their dealings with their devotees;[28] Vodouists believe that the lwa are easily offended, for instance if offered food that they dislike.[89] When angered, the lwa are believed to remove their protection from their devotees, or to inflict misfortune, illness, or madness on an individual.[90]

Although there are exceptions, most lwa names derive from the Fon and Yoruba languages.[91] New lwa are nevertheless added;[81] practitioners believe that some Vodou priests and priestesses became lwa after death, or that certain talismans become lwa.[92] Vodouists often refer to the lwa residing in "Guinea", but this is not intended as a precise geographical location,[93] but a generalized understanding of Africa as the ancestral land.[94] Many lwa are also understood to live under the water, at the bottom of the sea or in rivers.[88] Vodouists believe that the lwa communicate with humans through dreams and through the possession of human beings.[95]

The nanchon

The lwa are divided into nanchon or "nations".[96] This classificatory system derives from the way in which enslaved West Africans were divided into "nations" upon their arrival in Haiti, usually based on their African port of departure rather than their ethno-cultural identity.[28] The term fanmi (family) is sometimes used synonymously with "nation" or alternatively as a sub-division of the latter category.[97] It is often claimed that there are 17 nanchon,[98] of which the Rada and the Petwo are the largest and most dominant.[99] The Rada derive their name from Arada, a city in the Dahomey kingdom of West Africa.[100] The Rada lwa are usually regarded as dous or doux, meaning that they are sweet-tempered.[101] The Petwo lwa are conversely seen as lwa chaud (lwa cho), indicating that they can be forceful or violent and are associated with fire;[101] they are generally regarded as being socially transgressive and subversive.[102] The Rada lwa are seen as being 'cool'; the Petwo lwa as 'hot'.[103] The Rada lwa are generally regarded as righteous, whereas their Petwo counterparts are thought of as being more morally ambiguous, associated with issues like money.[104] The Petwo lwa derive from various backgrounds, including Creole, Kongo, and Dahomeyan.[105] Many lwa exist andezo or en deux eaux, meaning that they are "in two waters" and are served in both Rada and Petwo rituals.[101]

Papa Legba, also known as Legba, is the first lwa saluted during ceremonies.[106] He is depicted as a feeble old man wearing rags and using a crutch.[107] Papa Legba is regarded as the protector of gates and fences and thus of the home, as well as of roads, paths, and crossroads.[106] The second lwa that are usually greeted are the Marasa or sacred twins.[108] In Vodou, every nation has its own Marasa,[109] reflecting a belief that twins have special powers.[110] Agwe, also known as Agwe-taroyo, is associated with aquatic life, and protector of ships and fishermen.[111] Agwe is believed to rule the sea with his consort, La Sirène.[112] She is a mermaid or siren, and is sometimes described as Èzili of the Waters because she is believed to bring good luck and wealth from the sea.[113] Èzili Freda or Erzuli Freda is the lwa of love and luxury, personifying feminine beauty and grace.[114] Ezili Dantor is a lwa who takes the form of a peasant woman.[115]

Zaka (or Azaka) is the lwa of crops and agriculture,[116] usually addressed as "Papa" or "Cousin".[117] His consort is the female lwa Kouzinn.[118] Loco is the lwa of vegetation, and because he is seen to give healing properties to various plant species is considered the lwa of healing too.[119] Ogou is a warrior lwa,[120] associated with weapons.[121] Sogbo is a lwa associated with lightning,[122] while his companion, Bade, is associated with the wind.[123] Danbala (or Damballa) is a serpent lwa and is associated with water, being believed to frequent rivers, springs, and marshes;[124] he is one of the most popular deities within the pantheon.[125] Danbala and his consort Ayida-Weddo (or Ayida Wedo) are often depicted as a pair of intertwining snakes.[124] The Simbi are understood as the guardians of fountains and marshes.[126]

Usually seen as a fanmi rather than a nanchon,[127] the gede (also ghede or guédé) are associated with the realm of the dead.[128] The head of the family is Baron Samedi ("Baron Saturday").[129] His consort is Gran Brigit;[130] she has authority over cemeteries and is regarded as the mother of many of the other gede.[131] When the gede are believed to have arrived at a Vodou ceremony they are usually greeted with joy because they bring merriment.[128] Those possessed by the gede at these ceremonies are known for making sexual innuendos;[132] the gede's symbol is an erect penis,[133] while the banda dance associated with them involves sexual-style thrusting.[134]

Most lwa are associated with specific Roman Catholic saints.[135] For instance, Azaka, the lwa of agriculture, is associated with Saint Isidore the farmer.[136] Similarly, because he is understood as the "key" to the spirit world, Papa Legba is typically associated with Saint Peter, who is visually depicted holding keys in traditional Roman Catholic imagery.[137] The lwa of love and luxury, Èzili Freda, is associated with Mater Dolorosa.[138] Danbala, who is a serpent, is often equated with Saint Patrick, who is traditionally depicted in a scene with snakes; alternatively he is often associated with Moses, whose staff turned into snakes.[139] The Marasa, or sacred twins, are typically equated with the twin saints Cosmos and Damian.[140] Scholars like Leslie Desmangles have argued that Vodouists originally adopted the Roman Catholic saints to conceal lwa worship when the latter was illegal during the colonial period.[141] Observing Vodou in the latter part of the 20th century, Donald J. Cosentino argued that it was no longer the case that the use of the Roman Catholic saints was merely a ruse, but rather reflected the genuine devotional expression of many Vodouists.[142] Chromolithographic prints of the saints have been popular among Vodouists since being invented in the mid-19th century,[142] while images of the saints are commonly applied to the drapo flags used in Vodou ritual,[143] and are also commonly painted on the walls of temples in Port-au-Prince.[144]

Soul

Vodou holds that Bondye created humanity in his image, fashioning humans out of water and clay.[145] It teaches the existence of a spirit or soul, the espri,[146] which is divided in two parts.[147] One of these is the ti bonnanj (ti bon ange or "little good angel"), and it is understood as the conscience that allows an individual to engage in self-reflection and self-criticism. The other part is the gwo bonnanj (gros bon ange or "big good angel") and this constitutes the psyche, source of memory, intelligence, and personhood.[148] These are both believed to reside within an individual's head.[149] Vodouists believe that the gwo bonnanj can leave the head and go travelling while a person is sleeping.[150]

Vodouists believe that every individual is intrinsically connected to a specific lwa. This lwa is their mèt tèt (master of the head).[151] They believe that this lwa informs the individual's personality.[152] Vodou holds that the identity of a person's tutelary lwa can be identified through divination or through consulting lwa when they possess other humans.[153] Some of the religion's priests and priestesses are deemed to have "the gift of eyes", in that they can directly see what an individual's tutelary lwa is.[154]

At bodily death, the gwo bonnanj join the Ginen, or ancestral spirits, while the ti bonnanj proceeds to the afterlife to face judgement before Bondye.[155] This idea of judgement before Bondye is more common in urban areas, having been influenced by Roman Catholicism, while in the Haitian mountains it is more common for Vodouists to believe that the ti bonnanj dissolves into the navel of the earth nine days after death.[156] It is believed that the gwo bonnanj stays in Ginen for a year and a day before being absorbed into the family of the Gede.[157] Ginen is often identified as being located beneath the sea, under the earth, or above the sky.[158]

Vodouists hold that the spirits of dead humans are different from the gede, who are regarded as lwa.[159] Vodouists believe that the dead continue to participate in human affairs,[160] requiring sacrifices.[76] It does not teach the existence of any afterlife realm akin to the Christian ideas of heaven and hell.[161] Rather, in Vodou the spirits of the dead are believed to often complain that their own realm is cold and damp and that they suffer from hunger.[162]

Morality, ethics, and gender roles

Vodou permeates every aspect of its adherent's lives.[163] The ethical standards it promotes correspond to its sense of the cosmological order.[73] A belief in the interdependence of things plays a role in Vodou approaches to ethical issues.[164] Serving the lwa is central to Vodou and its moral codes reflect the reciprocal relationship that practitioners have with these spirits,[165] with a responsible relationship with the lwa ensuring that virtue is maintained.[86] Vodou also reinforces family ties;[166] respect for the elderly is a key value,[167] with the extended family being of importance in Haitian society.[168]

Vodou does not promote a dualistic belief in a firm division between good and evil.[169] It offers no prescriptive code of ethics;[170] rather than being rule-based, Vodou morality is deemed contextual to the situation.[171] Vodou reflects people's everyday concerns, focusing on techniques for mitigating illness and misfortune;[172] doing what one needs to in order to survive is considered a high ethic.[173] Among Vodouists, a moral person is regarded as someone who lives in tune with their character and that of their tutelary lwa.[171] In general, acts that reinforce Bondye's power are deemed good; those that undermine it are seen as bad.[73] Maji, meaning the use of supernatural powers for self-serving and malevolent ends, are usually regarded as being bad.[174] The term is quite flexible; it is usually used to denigrate other Vodouists, although some practitioners have used it as a self-descriptor in reference to petwo rites.[175]

Vodou promotes a belief in destiny, although individuals are still deemed to have freedom of choice.[176] This view of destiny has been interpreted as encouraging a fatalistic outlook among practitioners,[177] something that the religion's critics, especially from Christian backgrounds, have argued has discouraged Vodouists from improving their society.[178] This has been extended into an argument that Vodou is responsible for Haiti's poverty,[179] an argument that in turn has been accused of being rooted in European colonial prejudices towards Africans and overlooking the complex historical and environmental factors impacting Haiti.[180]

Vodou has been described as reflecting misogynistic elements of Haitian culture while at the same time empowering women to a greater extent than in many religions by allowing them to become priestesses.[181] As social and spiritual leaders, women can also lay claim to moral authority in Vodou.[182] Some practitioners state that the lwa determined their sexual orientation, turning them homosexual;[183] various priests are homosexual,[184] and the lwa Èzili is seen as the patron of masisi (gay men).[185]

Practices

Mostly revolving around interactions with the lwa,[186] Vodou ceremonies make use of song, drumming, dance, prayer, possession, and animal sacrifice.[187] Practitioners gather together for sèvices (services) in which they commune with the lwa.[188] Ceremonies for a particular lwa often coincide with the feast day of the Roman Catholic saint that that lwa is associated with.[189] The mastery of ritual forms is considered imperative in Vodou.[190] The purpose of ritual is to echofe (heat things up), thus bringing about change whether that be to remove barriers or to facilitate healing.[191]

Secrecy is important in Vodou.[192] It is an initiatory tradition,[193] operating through a system of graded induction or initiation.[104] When an individual agrees to serve a lwa, it is deemed a lifelong commitment.[194] Vodou has a strong oral culture, and its teachings are primarily disseminated through oral transmission.[195] Texts began appearing in the mid-twentieth century, at which point they were utilised by Vodouists.[196] Métraux described Vodou as "a practical and utilitarian religion".[88]

Oungan and Manbo

Male priests are referred to as an oungan, alternatively spelled houngan or hungan,[197] or a prèt Vodou ("Vodou priest").[198] Priestesses are termed manbo, alternatively spelled mambo.[199] Oungan numerically dominate in rural Haiti, while there is a more equitable balance of priests and priestesses in urban areas.[200] The oungan and manbo are tasked with organising liturgies, preparing initiations, offering consultations with clients using divination, and preparing remedies for the sick.[201] There is no priestly hierarchy, with oungan and manbo being largely self-sufficient.[201] In many cases, the role is hereditary.[202] Historical evidence suggests that the role of the oungan and manbo intensified over the course of the 20th century.[203] As a result, "temple Vodou" is now more common in rural areas of Haiti than it was in historical periods.[204]

Vodou teaches that the lwa call an individual to become an oungan or manbo,[205] and if the latter refuses then misfortune may befall them.[206] A prospective oungan or manbo must normally rise through the other roles in a Vodou congregation before undergoing an apprenticeship with a pre-existing oungan or manbo lasting several months or years.[207] After this apprenticeship, they undergo an initiation ceremony, the details of which are kept secret from non-initiates.[208] Other oungan and manbo do not undergo any apprenticeship, but claim that they have gained their training directly from the lwa.[209] Their authenticity is often challenged, and they are referred to as hungan-macoutte, a term bearing some disparaging connotations.[207] Becoming an oungan or manbo is expensive, often requiring the purchase of ritual paraphernalia and land on which to build a temple.[210] To finance this, many save up for a long time.[210]

Vodouists believe that the oungan's role is modelled on the lwa Loco;[211] in Vodou mythology, he was the first oungan and his consort Ayizan the first manbo.[212] The oungan and manbo are expected to display the power of second sight,[213] something that is regarded as a gift from the creator deity that can be revealed to the individual through visions or dreams.[214] Many priests and priestesses are often attributed fantastical powers in stories told about them, such as that they could spend several days underwater.[215] Priests and priestess also bolster their status with claims that they have received spiritual revelations from the lwa, sometimes via visits to the lwa's own abode.[216]

There is often bitter competition between different oungan and manbo.[217] Their main income derives from healing the sick, supplemented with payments received for overseeing initiations and selling talismans and amulets.[218] In many cases, these oungan and manbo become wealthier than their clients.[219] Oungan and manbo are generally powerful and well-respected members of Haitian society.[220] Being an oungan or manbo provides an individual with both social status and material profit,[184] although the fame and reputation of individual priests and priestesses can vary widely.[221] Respected Vodou priests and priestesses are often literate in a society where semi-literacy and illiteracy are common.[222] They can recite from printed sacred texts and write letters for illiterate members of their community.[222] Owing to their prominence in a community, the oungan and manbo can effectively become political leaders,[214] or otherwise exert an influence on local politics.[184] Some oungan and manbo have linked themselves closely with professional politicians, for instance during the reign of the Duvaliers.[214]

The Ounfò

A Vodou temple is called an ounfò,[223] varyingly spelled hounfò,[224] hounfort,[20] or humfo.[40] An alternative term is gangan, although the connotations of this term vary regionally in Haiti.[225] Most communal Vodou activities center around this ounfò,[212] forming what is called "temple Vodou".[41] The size and shape of ounfòs vary, from basic shacks to more lavish structures, the latter being more common in Port-au-Prince than elsewhere in Haiti;[212] their designs are dependent on the resources and tastes of the oungan or manbo running them.[226] Each ounfò being autonomous,[227] they have their own unique customs.[228]

The main ceremonial room within the ounfò is the peristil or peristyle,[229] understood as a microcosmic representation of the cosmos.[230] In the peristil, brightly painted posts hold up the roof;[231] the central post is the poto mitan or poteau mitan,[232] which is used as a pivot during ritual dances and serves as the "passage of the spirits" by which the lwa enter the room during ceremonies.[231] It is around this central post that offerings, including both vèvè and animal sacrifices, are made.[186] However, in the Haitian diaspora many Vodouists perform their rites in basements, where no poto mitan are available.[233] The peristil typically has an earthen floor, allowing libations to the lwa to drain directly into the soil,[234] although where this is not possible, libations are instead poured into an enamel basin.[235] Some peristil include seating around the walls.[236]

Adjacent rooms in the ounfò include the caye-mystéres, which is also known as the bagi, badji, or sobadji.[237] This is where stonework altars, known as pè, stand against the wall or are arranged in tiers.[237] The caye-mystéres is also used to store clothing associated with the possessing lwa that is placed onto the individual experiencing possession during the rituals in the peristil.[238] Many pè also have a sink sacred to the lwa Danbala-Wedo.[239] If space is available, the ounfò may also have a room set aside for the patron lwa of that temple.[240] Many ounfòs have a room known as the djévo in which the initiate is confined during their initiatory ceremony.[241] Every ounfò usually has a room or corner of a room devoted to Erzuli Freda.[242] Some ounfò will also have additional rooms in which the oungan or manbo lives.[240]

The area around the ounfò often contains sacred objects, such as a pool of water for Danbala, a black cross for Baron Samedi, and a pince (iron bar) embedded in a brazier for Criminel.[243] Sacred trees, known as arbres-reposoirs, sometimes mark the external boundary of the ounfò, and are encircled by stone-work edging.[244] Hanging from these trees can be found macounte straw sacks, strips of material, and animal skulls.[244] Various animals, particularly birds but also some mammal species such as goats, are sometimes kept within the perimeter of the ounfò for use as sacrifices.[244]

The congregation

Forming a spiritual community of practitioners,[186] those who congregate at the ounfò are known as the pititt-caye (children of the house).[245] They worship under the authority of an oungan or manbo,[40] below whom is ranked the ounsi, individuals who make a lifetime commitment to serving the lwa.[246] Members of either sex can join the ounsi, although the majority are female.[247] The ounsi have many duties, such as cleaning the peristil, sacrificing animals, and taking part in the dances at which they must be prepared to be possessed by a lwa.[248] The oungan and manbo oversee initiatory ceremonies whereby people become ounsi,[214] oversee their training,[212] and act as their counsellor, healer, and protector.[249] In turn, the ounsi are expected to be obedient to their oungan or manbo.[248]

One of the ounsi becomes the hungenikon or reine-chanterelle, the mistress of the choir. This individual is responsible for overseeing the liturgical singing and shaking the chacha rattle which is used to control the rhythm during ceremonies.[250] They are aided by the hungenikon-la-place, commandant general de la place, or quartermaster, who is charged with overseeing offerings and keeping order during the ceremonies.[212] Another figure is le confiance (the confidant), the ounsi who oversees the ounfò's administrative functions.[251] The initiates of a particular priest/priestess form "families."[196] A priest becomes the papa ("father") while the priestess becomes the manman ("mother") to the initiate;[252] the initiate becomes their initiator's pitit (spiritual child).[196] Those who share an initiator refer to themselves as "brother" and "sister."[207]

In rural areas especially, a congregation may consist of an extended family.[201] In other examples, particularly in urban areas, an ounfò can act as an initiatory family.[253] Individuals may join a particular ounfò because it exists in their locality or because their family are already members. Alternatively, it may be that the ounfò places particular focus on a lwa whom they are devoted to, or that they are impressed by the oungan or manbo who runs the ounfò in question, perhaps having been treated by them.[248]

Congregants often form a sosyete soutyen (société soutien, support society), through which subscriptions are paid to help maintain the ounfò and organize the major religious feasts.[254] In rural Haiti, it is often the patriarch of an extended family who serves as the priest for said family.[255] Families, particularly in rural areas, often believe that through their zansèt (ancestors) they are tied to a premye mèt bitasyon (original founder); their descent from this figure is seen as giving them their inheritance both of the land and of familial spirits.[38]

Initiation

Vodou is hierarchical and includes a series of initiations.[196] There are typically four levels of initiation,[256] the fourth of which makes someone an Houngan or mambo.[257] The initial initiation rite is known as the kanzo;[258] this term also describes the initiate themselves.[259] There is much variation in what these initiation ceremonies entail,[109] and the details are kept secret.[260] Vodou entails practitioners being encouraged to undertake stages of initiation into a state of mind called konesans (conaissance or knowledge).[214] Successive initiations are required to move through the various konesans,[214] and it is in these konesans that priestly power is believed to reside.[261] Initiation is generally expensive,[262] complex,[257] and requires significant preparation.[109] Prospective initiates are for instance required to memorise many songs and learn the characteristics of various lwa.[109] Vodouists believe the lwa may encourage an individual towards initiation, bringing misfortune upon them if they refuse.[263]

Initiation will often be preceded by bathing in special preparations.[264] The first part of the initiation rite is known as the kouche, coucher, or huño, and is marked by salutations and offerings to the lwa.[265] It begins with the chire ayizan, a ceremony in which palm leaves are frayed and then worn by the initiate.[109] Sometimes the bat ge or batter guerre ("beating war") is performed instead, designed to beat away the old.[109] During the rite, the initiate comes to be regarded as the child of a particular lwa, their mèt tèt.[109]

This is followed by a period of seclusion within the djèvo known as the kouche.[109] A deliberately uncomfortable experience,[149] it involves the initiate sleeping on a mat on the floor, often with a stone for a pillow.[266] They wear a white tunic,[267] and a specific salt-free diet is followed.[268] It includes a lav tèt or lave tèt ("head washing") to prepare the initiate for having the lwa enter and reside in their head.[269] Voudoists believe that one of the two parts of the human soul, the gwo bonnanj, is removed from the initiate's head, thus making space for the lwa to enter and reside there.[149]

The initiation ceremony requires the preparation of pot tèts (head pots), usually white porcelain cups with a lid in which a range of items are placed, including hair, food, herbs, and oils. These are then regarded as a home for the spirits.[270] After the period of seclusion in the djèvo, the new initiate is brought out and presented to the congregation; they are now referred to as ounsi lave tèt.[109] When the new initiate is presented to the rest of the community, they carry their pot tèt on their head, before placing it on the altar.[149] The final stage of the process involves the initiate being given an ason rattle.[271] The initiation process is seen to have ended when the new initiate is first possessed by a lwa.[149] Initiation is seen as creating a bond between a devotee and their tutelary lwa,[272] and the former will often take on a new name that alludes to the name of their lwa.[273]

Shrines and altars

The creation of sacred works is important in Vodou.[190] Votive objects used in Haiti are typically made from industrial materials, including iron, plastic, sequins, china, tinsel, and plaster.[36] An altar, or pè, will often contain images (typically lithographs) of Roman Catholic saints.[274] Since developing in the mid-nineteenth century, chromolithography has also had an impact on Vodou imagery, facilitating the widespread availability of images of the Roman Catholic saints who are equated with the lwa.[275] Various Vodouists have made use of varied available materials in constructing their shrines. Cosentino encountered a shrine in Port-au-Prince where Baron Samedi was represented by a plastic statue of Santa Claus wearing a black sombrero,[276] and in another by a statue of Star Wars-character Darth Vader.[277] In Port-au-Prince, it is common for Vodouists to include human skulls on their altar for the gedes.[198] Many practitioners will also have an altar devoted to their ancestors in their home, to which they direct offerings.[278]

Various spaces other than the temple are used for Vodou ritual.[279] Cemeteries are seen as places where spirits reside, making them suitable for certain rituals,[279] especially to approach the spirits of the dead.[280] In rural Haiti, cemeteries are often family owned and play a key role in family rituals.[281] Crossroads are also ritual locations, selected as they are believed to be points of access to the spirit world.[279] Other spaces used for Vodou rituals include Christian churches, rivers, the sea, fields, and markets.[279]

Certain trees are regarded as having spirits resident in them and are used as natural altars.[222] Different species of tree are associated with different lwa; Oyu is for linked with mango trees, and Danbala with bougainvillea.[88] Selected trees in Haiti have had metal items affixed to them, serving as shrines to Ogou, who is associated with both iron and the roads.[282] Spaces for ritual also appear in the homes of many Vodouists.[283] These may vary from complex altars to more simple variants including only images of saints alongside candles and a rosary.[41]

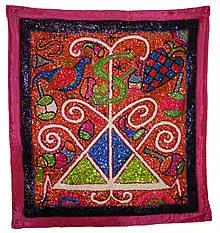

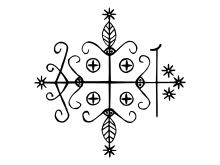

Drawings known as vèvè are sketched onto the floor of the peristil using cornmeal, ash, coffee grounds, or powdered eggshells;[284] these are central to Vodou ritual.[230] Usually arranged symmetrically around the poteau-mitan,[285] these designs sometimes incorporate letters;[222] their purpose is to summon lwa.[285] Inside the peristil, practitioners also unfurl ceremonial flags known as drapo (flags) at the start of a ceremony.[286] Often made of silk or velvet and decorated with shiny objects such as sequins,[287] the drapo often feature either the vèvè of specific lwa they are dedicated to or depictions of the associated Roman Catholic saint.[143] These drapo are understood as points of entry through which the lwa can enter the peristil.[288]

A batèms (baptism) is a ritual used to make an object a vessel for the lwa.[289] Objects consecrated for ritual use are believed to contain a spiritual essence or power called nanm.[290] The ason (also written as asson) is a sacred rattle used in summoning the lwa.[291] It consists of an empty, dried gourd covered in beads and snake vertebra.[292] Prior to being used in ritual it requires consecration.[293] It is a symbol of the priesthood;[293] assuming the duties of a manbo or oungan is referred to as "taking the ason."[294] Another type of sacred object are the "thunder stones", often prehistoric axe-heads, which are associated with specific lwa and kept in oil to preserve their power.[295]

Offerings and animal sacrifice

Feeding the lwa is of great importance in Vodou,[296] with rites often termed manje lwa ("feeding the lwa").[297] Offering food and drink to the lwa is the most common ritual within the religion, conducted both communally and in the home.[296] An oungan or manbo will also organize an annual feast for their congregation in which animal sacrifices to various lwa will be made.[165] The choice of food and drink offered varies depending on the lwa in question, with different lwa believed to favour different foodstuffs.[298] Danbala for instance requires white foods, especially eggs.[299] Foods offered to Legba, whether meat, tubers, or vegetables, need to be grilled on a fire.[296] The lwa of the Ogu and Nago nations prefer raw rum or clairin as an offering.[296]

A manje sèk (dry meal) is an offering of grains, fruit, and vegetables that often precedes a simple ceremony; it takes its name from the absence of blood.[300] Species used for sacrifice include chickens, goats, and bulls, with pigs often favored for petwo lwa.[297] The animal may be washed, dressed in the color of the specific lwa, and marked with food or water.[301] Often, the animal's throat will be cut and the blood collected in a calabash.[302] Chickens are often killed by the pulling off of their heads; their limbs may be broken beforehand.[303] The organs are removed and placed on the altar or vèvè.[303] The flesh will be cooked and placed on the altar, subsequently often being buried.[302] Maya Deren wrote that: "The intent and emphasis of sacrifice is not upon the death of the animal, it is upon the transfusion of its life to the lwa; for the understanding is that flesh and blood are of the essence of life and vigor, and these will restore the divine energy of the god."[304] Because Agwé is believed to reside in the sea, rituals devoted to him often take place beside a large body of water such as a lake, river, or sea.[305] His devotees sometimes sail out to Trois Ilets, drumming and singing, where they throw a white sheep overboard as a sacrifice to him.[306]

The food is typically offered when it is cool; it remains there for a while before humans can then eat it.[307] The food is often placed within a kwi, a calabash shell bowl.[307] Once selected, the food is placed on special calabashes known as assiettes de Guinée which are located on the altar.[165] Offerings not consumed by the celebrants are then often buried or left at a crossroads.[308] Libations might be poured into the ground.[165] Vodouists believe that the lwa then consume the essence of the food.[165] Certain foods are also offered in the belief that they are intrinsically virtuous, such as grilled maize, peanuts, and cassava. These are sometimes sprinkled over animals that are about to be sacrificed or piled upon the vèvè designs on the floor of the peristil.[165]

The Dans

Vodou's nocturnal gatherings are often referred to as the dans ("dance"), reflecting the prominent role that dancing has in such ceremonies.[233] Their purpose is to invite a lwa to enter the ritual space and possess one of the worshippers, through whom they can communicate with the congregation.[309] The success of this procedure is predicated on mastering the different ritual actions and on getting the aesthetic right to please the lwa.[309] The proceedings can last for the entirety of the night.[233] The dancing takes place counterclockwise around the poto mitan.[310]

On arriving, the congregation typically disperse along the perimeter of the peristil.[233] The ritual often begins with Roman Catholic prayers and hymns;[311] these are often led by a figure known as the prèt savann, although not all ounfò have anyone in this role.[312] This is followed by the shaking of the ason rattle to summon the lwa.[313] Two Haitian Creole songs, the Priyè Deyò ("Outside Prayers"), may then be sung, lasting from 45 minutes to an hour.[314] The main lwa are then saluted, individually, in a specific order.[314] Legba always comes first, as he is believed to open the way for the others.[314] Each lwa may be offered either three or seven songs, which are specific to them.[315]

The rites employed to call down the lwa vary depending on the nation in question.[316] During large-scale ceremonies, the lwa are invited to appear through the drawing of patterns, known as vèvè, on the ground using cornmeal.[204] Also used to call down the spirits is a process of drumming, singing, prayers, and dances.[204] Libations and offerings of food are made to the lwa, which includes animal sacrifices.[204] The order and protocol for welcoming the lwa is referred to as regleman.[317]

.jpg.webp)

A symbol of the religion,[318] the drum is perhaps the most sacred item in Vodou.[319] Vodouists believe that ritual drums contain an etheric force, the nanm,[320] and a spirit called ountò.[321] Specific ceremonies accompany the construction of a drum so that it is considered suitable for use in Vodou ritual.[322] In the bay manje tanbou ("feeding of the drum") ritual, offerings are given to the drum itself.[320] Reflecting its status, when Vodouists enter the peristil they customarily bow before the drums.[323] Different types of drum are used, sometimes reserved for rituals devoted to specific lwa; petwo rites for instance involve two types of drum, whereas rada rituals require three.[324] In Vodou ritual, drummers are called tanbouryes (tambouriers),[325] and becoming one requires a lengthy apprenticeship.[326] The drumming style, choice of rhythm, and composition of the orchestra differs depending on which nation of lwa are being invoked.[327] The drum rhythms typically generate a kase ("break"), which the master drummer will initiate to oppose the main rhythm being played by the rest of the drummers. This is seen as having a destabilizing effect on the dancers and helping to facilitate their possession.[328]

The drumming is typically accompanied by singing,[323] usually in Haitian Creole.[329] These songs are often structured around a call and response, with a soloist singing a line and the chorus responding with either the same line or an abbreviated version.[329] The soloist is the oundjenikon, who maintains the rhythm with a rattle.[330] Lyrically simple and repetitive, these songs are invocations to summon a lwa.[323] As well as drumming, dancing plays a major role in ritual,[331] with the drumming providing the rhythm for the dance.[329] The dances are simple, lacking complex choreography, and usually involve the dancers moving counterclockwise around the poto mitan.[332] Specific dance movements can indicate the lwa or their nation being summoned;[333] dances for Agwe for instance imitate swimming motions.[334] Vodouists believe that the lwa renew themselves through the vitality of the dancers.[335]

Spirit possession

Spirit possession constitutes an important element of Vodou,[336] being at the heart of many of its rituals.[86] The person being possessed is referred to as the chwal (horse);[337] the act of possession is called "mounting a horse".[338] Vodou teaches that a lwa can possess an individual regardless of gender; both male and female lwa can possess either men or women.[339] Although children are often present at these ceremonies,[340] they are rarely possessed as it is considered too dangerous.[341] While the specific drums and songs used are designed to encourage a specific lwa to possess someone, sometimes an unexpected lwa appears and takes possession instead.[342] In some instances a succession of lwa possess the same individual, one after the other.[343]

The trance of possession is known as the kriz lwa.[326] Vodouists believe that during this process, the lwa enters the head of the chwal and displaces their gwo bon anj.[344] This displacement is believed to cause the chwal to tremble and convulse;[345] Maya Deren described a look of "anguish, ordeal and blind terror" on the faces of those as they became possessed.[335] Because their consciousness has been removed from their head during the possession, Vodouists believe that the chwal will have no memory of what occurs during the incident.[346] The length of the possession varies, often lasting a few hours but sometimes several days.[347] It may end with the chwal collapsing in a semi-conscious state;[348] they are typically left physically exhausted.[335] Some individuals attending the dance will put a certain item, often wax, in their hair or headgear to prevent possession.[349]

Once the lwa possesses an individual, the congregation greet it with a burst of song and dance.[335] The chwal will typically bow before the officiating priest or priestess and prostrate before the poto mitan.[350] The chwal is often escorted into an adjacent room where they are dressed in clothing associated with the possessing lwa. Alternatively, the clothes are brought out and they are dressed in the peristil itself.[339] Once the chwal has been dressed, congregants kiss the floor before them.[339] These costumes and props help the chwal take on the appearance of the lwa.[329] Many ounfò have a large wooden phallus on hand which is used by those possessed by Ghede lwa during their dances.[351]

The chwal takes on the behavior and expressions of the possessing lwa;[352] their performance can be very theatrical.[342] Those believing themselves possessed by the serpent Danbala, for instance, often slither on the floor, dart out their tongue, and climb the posts of the peristil.[124] Those possessed by Zaka, lwa of agriculture, will dress as a peasant in a straw hat with a clay pipe and will often speak in a rustic accent.[353] The chwal will often then join in with the dances, dancing with anyone whom they wish to,[335] or sometimes eating and drinking.[329] Sometimes the lwa, through the chwal, will engage in financial transactions with members of the congregation, for instance by selling them food that has been given as an offering or lending them money.[354]

Possession facilitates direct communication between the lwa and its followers;[335] through the chwal, the lwa communicates with their devotees, offering counsel, chastisement, blessings, warnings about the future, and healing.[355] Lwa possession has a healing function, with the possessed individual expected to reveal possible cures to the ailments of those assembled.[335] Clothing that the chwal touches is regarded as bringing luck.[356] The lwa may also offer advice to the individual they are possessing; because the latter is not believed to retain any memory of the events, it is expected that other members of the congregation will pass along the lwa's message.[356] In some instances, practitioners have reported being possessed at other times of ordinary life, such as when someone is in the middle of the market,[357] or when they are asleep.[358]

Divination

A common form of divination employed by oungan and manbo is to invoke a lwa into a pitcher, where it will then be asked questions.[359] The casting of shells is also used in some ounfo.[359] A form of divination associated especially with Petwo lwa is the use of a gembo shell, sometimes with a mirror attached to one side and affixed at both ends to string. The string is twirled and the directions of the shell used to interpret the responses of the lwa.[359] Playing cards will also often be used for divination.[360] Other types of divination used by Vodouists include studying leaves, coffee grounds or cinders in a glass, or looking into a candle flame.[361]

Healing and harming

.jpg.webp)

Healing plays an important role in Vodou.[362] A client will approach the manbo or oungan complaining of illness or misfortune and the latter will use divination to determine the cause and select a remedy.[363] Manbo and oungan typically have a wide knowledge of plants and their uses in healing.[175] To heal, they often prescribe baths, water infused with various ingredients.[364] In Haiti, there are also "herb doctors" who offer herbal remedies for various ailments; separate from the oungan and manbo, they have a more limited range in the problems that they deal with.[218] Manbo and oungan often provide talismans,[365] called pwen (points)[366] or travay (work).[367] Certain talismans, appearing as wrapped bundles, are called pakèt or pakèt kongo.[368] They may also produce powders for a specific purpose, such as to attract good luck or aid seduction.[369]

In Haiti, oungan or manbo may advise their clients to seek assistance from medical professionals, while the latter may also send their patients to see an oungan or manbo.[219] Amid the spread of the HIV/AIDS virus in Haiti during the late twentieth century, health care professionals raised concerns that Vodou was contributing to the spread of the disease, both by sanctioning sexual activity among a range of partners and by having individuals consult oungan and manbo for medical advice rather than doctors.[370] By the early 21st century, various NGOs and other groups were working on bringing Vodou officiants into the broader campaign against HIV/AIDS.[371]

Vodou teaches that supernatural factors cause or exacerbate many problems.[372] It holds that humans can cause supernatural harm to others, either unintentionally or deliberately,[373] in the latter case exerting power over a person through possession of hair or nail clippings belonging to them.[374] Vodouists also often believe that supernatural harm can be caused by other entities. The lougawou (werewolf) is a human, usually female, who transforms into an animals and drains blood from sleeping victims,[375] while members of the Bizango secret society are feared for their reputed ability to transform into dogs, in which form they walk the streets at night.[376]

An individual who turns to the lwa to harm others is a choché,[169] or a bòkò or bokor,[377] although this latter term can also refer to an oungan generally.[169] They are described as someone who sert des deux mains ("serves with both hands"),[378] or is travaillant des deux mains ("working with both hands").[205] These practitioners employ baka, malevolent spirits sometimes in animal form.[379] Bòko are also believed to work with lwa achte ("bought lwa"), because the good lwa have rejected them as unworthy.[380] Their rituals are often linked with petwo rites,[381] and are similar to Jamaican obeah.[381] According to Haitian popular belief, these bòkò engage in anvwamò or expeditions, setting the dead against an individual to cause the latter's the sudden illness and death.[382] In Haitian religion, it is commonly believed that an object can be imbued with supernatural qualities, making it a wanga, which then generates misfortune and illness.[383] In Haiti, there is much suspicion and censure toward those suspected of being bòkò,[205] as well as fears regarding groups of these sorcerers.[384] The curses of the bòkò are believed to be countered by the actions of the oungan and manbo, who can revert the curse through an exorcism that incorporates invocations of protective lwa, massages, and baths.[381] In Haiti, some oungan and manbo have been accused of actively working with bòkò, organizing for the latter to curse individuals so that they can financially profit from removing these curses.[205]

Funerals and the dead

.jpg.webp)

Vodou features complex funerary customs.[386] Following an individual's death, the desounen ritual frees the gwo bonnanj from their body and disconnects them from their tutelary lwa.[387] The corpse is then bathed in a herbal infusion by an individual termed the benyè, who gives the dead person messages to take with them.[388] A wake, the veye, follows.[389] The body is then buried in the cemetery,[390] often according to Roman Catholic custom.[391] Haitian cemeteries are often marked by large crosses, symbols of Baron Samedi.[392] In northern Haiti, an additional rite takes place at the ounfò on the day of the funeral, the kase kanari (breaking of the clay pot). In this, a jar is washed in substances including kleren, placed within a trench dug into the peristil floor, and then smashed. The trench is then refilled.[393] The night after the funeral, the novena takes place at the home of the deceased, involving Roman Catholic prayers;[394] a mass for them is held a year after death.[395]

Vodouists believe that the practitioner's spirit dwells at the bottom of a lake or river for a year and a day.[396] A year and a day after death, the wete mò nan dlo ("extracting the dead from the waters of the abyss") ritual may take place, in which the deceased's gwo bonnanj is reclaimed from the realm of the dead and placed into a clay jar or bottle called the govi. Now ensconced in the world of the living, the gwo bonnanj of this ancestor is deemed capable of assisting its descendants and guiding them with its wisdom.[397] Practitioners sometimes believe that failing to conduct this ritual can result in misfortune, illness, and death for the family of the deceased.[398] Offering then given to this dead spirit are termed manje mò.[399]

Vodouists fear the dead's ability to harm the living;[400] it is believed that the deceased may for instance punish their living relatives if the latter fail to mourn them appropriately.[401] Another belief about the dead is one of the most sensationalized aspects of Haitian religion, belief in zombis.[402] Many Vodouists believe that a bòkò can cause a person's death and then seize their ti bon ange, leaving the victim pliant and willing to obey their commands.[403] Most commonly, it is thought the spirit becomes a zombi,[404] in other cases it is thought the body does.[405] Haitians generally do not fear zombis, but rather fear becoming one themselves.[403]

Festival and Pilgrimage

On the saints' days of the Roman Catholic calendar, Vodouists often hold "birthday parties" for the lwa associated with the saint whose day it is.[406] During these, special altars for the lwa being celebrated may be made,[407] and their preferred food will be prepared.[408] Devotions to the gede are particularly common around the days of the dead, All Saints (1 November) and All Souls (2 November).[409] Honoring the dead, these celebrations largely take place in the cemeteries of Port-au-Prince.[410] At this festival, those devoted to the Gede spirits dress in a manner linking in with the Gede's associations with death. This includes wearing black and purple clothing, funeral frock coats, black veils, top hats, and sunglasses.[411]

Pilgrimage is a part of Haitian religious culture.[412] In late July, Vodouist pilgrims visit Plaine du Nord near Bwa Caiman, where according to legend the Haitian Revolution began. There, sacrifices are made and pilgrims immerse themselves in the twou (mud pits).[413] The pilgrims often mass before the Church of Saint Jacques, with Saint Jacques perceived as being the lwa Ogou.[414] Another pilgrimage site is Saint d'Eau, a mountain associated with the lwa Èzili Dantò.[415] Pilgrims visit a site outside the town of Ville-Bonheur where Èzili is claimed to have once appeared; there, they bathe under waterfalls.[416] Haitian pilgrims commonly wear coloured ropes around their head or waist while undertaking their pilgrimage.[412] The scholars of religion Terry Rey and Karen Richman argued that this may derive from a Congolese custom, kanga ("to tie"), during which sacred objects were ritually bound with rope.[417]

History

Before the Revolution

In 1492, Christopher Columbus' Spanish expedition established the first European colony on Hispaniola.[418] A growing European presence decimated the island's indigenous population, which was probably Taíno, both through introduced diseases and exploitation as laborers.[419] The European colonists then turned to imported West African slaves as a new source of labor; Africans first arrived on Hispaniola circa 1512.[420] Most of the enslaved were prisoners of war.[421] Some were probably priests of traditional religions, helping to transport their rites to the Americas.[421] Others may have practiced Abrahamic religions. Some were probably Muslim, although Islam exerted little influence on Vodou,[422] while others probably practiced traditional religions that had already absorbed Roman Catholic iconographic influences.[423]

By the late 16th century, French colonists were settling in western Hispaniola; Spain recognized French sovereignty over that part of the island, which became Saint-Domingue, in a series of treaties signed in 1697.[424] Moving away from its previous subsistence economy, in the 18th century Saint-Domingue refocused its economy around the mass export of indigo, coffee, sugar, and cocoa to Europe.[425] To work the plantations, the French colonists sought labor from various sources, including a renewed emphasis on importing enslaved Africans; whereas there were twice as many Africans as Europeans in the colony in 1681, by 1790 there were eleven times as many Africans as Europeans.[426] Ultimately, Saint-Domingue became the colony with the largest number of slaves in the Caribbean.[427]

The Code Noir issued by King Louis XIV in 1685 forbade the open practice of African religions on Saint-Domingue.[141] This Code compelled slave-owners to have their slaves baptised and instructed as Roman Catholics;[428] the fact that the process of enslavement led to these Africans becoming Christian was a key way in which the slave-owners sought to morally legitimate their actions.[429] However, many slave-owners took little interest in having their slaves instructed in Roman Catholic teaching;[429] they often did not want their slaves to spend time celebrating saints' days rather than laboring and were also concerned that black congregations could provide scope to foment revolt.[430]

Enslavement destroyed the social fabric of African traditional religions, which were typically rooted in ethnic and family membership.[431] Although certain cultural assumptions about the nature of the universe would have been widely shared among the enslaved Africans, they came from diverse linguistic and ethno-cultural backgrounds and had to forge common cultural practices on Hispaniola.[432] Gradually over the course of the 18th century, Vodou emerged as "a composite of various African ethnic traditions", merging diverse practices into a more cohesive form.[433] These African religions had to be practiced secretly, with Roman Catholic iconography and rituals probably adopted so as to conceal the true identity of the deities that enslaved Africans were serving.[141] This resulted in a system of correspondences between African spirits and Roman Catholic saints.[141] Afro-Haitians adopted other aspects of French colonial culture;[434] Vodou drew influence from European grimoires,[435] as well as European commedia performances.[436] Also an influence was Freemasonry, after Masonic lodges were established across Saint-Domingue in the 18th century.[437] Vodou rituals took place in secret, usually at night; one such rite was described during the 1790s by a white man, Médéric Louis Élie Moreau de Saint-Méry.[438] Some enslaved Afro-Haitians escaped to form Maroon groups, which often practiced Vodou in forms influenced by the ethno-cultural background of their leaders.[439]

The Haitian Revolution and the 19th century

While scholars debate Vodou's role in the Haitian Revolution,[440] in Haitian culture, the religion has long been presented as having had a vital role within it.[23] Two of the revolution's early leaders, Boukman and Francois Mackandal, were reputed to be powerful houngans.[441] According to legend, a Vodou ritual took place in Bois-Caïman on 14 August 1791 at which the participants swore to overthrow the slave owners. After this ritual they massacred whites living in the local area, sparking the Revolution.[442] Although a popular tale in Haitian folklore, it has no historical evidence to support it.[443] Amid growing rebellion, the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte ordered troops, led by Charles Leclerc, into the colony in 1801.[444] In 1803 the French military conceded defeat and the rebel leader Jean-Jacques Dessalines proclaimed Saint-Domingue to be a new republic named Haiti.[445] After Dessalines died in 1806, Haiti split into two countries before reuniting in 1822.[446]

The Revolution broke up the large land-ownings and created a society of small subsistence farmers.[447] Haitians largely began living in lakous, or extended family compounds, which enabled the preservation of African-derived Creole religions.[448] These lakous often had their own lwa rasin (root lwa),[449] being intertwined with concepts of land and kinship.[450] Many Roman Catholic missionaries had been killed during the Revolution,[451] and after its victory Dessalines declared himself head of the Church in Haiti.[451] In protest at these actions, the Roman Catholic Church cut ties with Haiti in 1805;[452] this allowed Vodou to predominate in the country.[453] Many churches left abandoned by Roman Catholic congregations were adopted for Vodou rites, continuing the syncretization between the different systems.[454] At this point, with no new arrivals from Africa, Vodou began to stabilise,[455] transforming from "a widely-scattered series of local cults" into "a religion".[456] The Roman Catholic Church re-established its formal presence in Haiti in 1860.[453]

Haiti's first three presidents sought to suppress Vodou, using police to break-up nocturnal rituals; they feared it as a source of rebellion.[457] In 1847, Faustin Soulouque became president; he was sympathetic to Vodou and allowed it to be practiced more openly.[458] In the Bizoton Affair of 1863, several Vodou practitioners were accused of ritually killing a child before eating it. Historical sources suggest that they may have been tortured prior to confessing to the crime, at which they were executed.[459] The affair received much attention.[459]

20th century to the present

The U.S. occupied Haiti between 1915 and 1934.[460] This encouraged international interest in Vodou,[461] catered for in the sensationalist writings of Faustin Wirkus, William Seabrook, and John Craige.[462] Some practitioners arranged shows based on Vodou rituals to entertain holidaymakers, especially in Port-au-Prince.[463] The period also saw growing rural to urban migration in Haiti,[464] and the increasing influence of the Roman Catholic Church.[464] During the first thirty years of the 20th century, thousands of Haitians migrated to Cuba to work in expanding sugar industry, settling primarily in eastern provinces.[465] There, Vodou spread from beyond the Haitiano-Cubanos and was adopted by other Cubans, including those who practiced Santería.[466]

1941 saw the launch of Operation Nettoyage (Operation Cleanup), a process backed by the Roman Catholic Church to expunge Vodou, resulting in the destruction of many ounfòs and Vodou paraphernalia.[467] Violent responses from Vodouists led President Élie Lescot to abandon the Operation.[468] Meanwhile, during the occupation, the indigenist movement among Haiti's middle classes encouraged a more positive assessment of Vodou and peasant culture, a trend supported by the appearance of professional ethnological research on the topic.[469]

The Church's influence in Haiti was curtailed by François Duvalier, the President of Haiti from 1957 to 1971.[470] Although he restored Roman Catholicism's role as the state religion, Duvalier was widely perceived as a champion of Vodou,[471] calling it "the supreme factor of Haitian unity".[472] He utilized it for his own purposes, encouraging rumors about his own powers of sorcery.[473] Under his government, regional networks of oungans doubled as the country's chefs-de-sections (rural section chiefs).[474] After his son, Jean-Claude Duvalier, was ousted from office in 1986, there were attacks on Vodouists perceived to have supported the Duvaliers, partly motivated by Protestant anti-Vodou campaigns; practitioners called this violence the "Dechoukaj" ('uprooting').[475] Two groups, the Zantray and Bode Nasyonal, were formed to defend the rights of Vodouists, holding rallies and demonstrations in Haiti.[476] Haiti's 1987 constitution enshrined freedom of religion,[477] after which President Jean-Bertrand Aristide granted Vodou official recognition in 2003,[478] thus allowing Vodouists to officiate at civil ceremonies such as weddings and funerals.[479]

Since the 1990s, evangelical Protestantism has grown in Haiti, generating tensions with Vodouists;[28] these Protestants regard Vodou as Satanic,[480] and unlike the Roman Catholic authorities have generally refused to compromise with Vodouists.[481] The 2010 Haiti earthquake fuelled conversion from Vodou to Protestantism,[482] with many Protestants, including the U.S. televangelist Pat Robertson, claiming that the earthquake was punishment for the sins of the Haitian population, including their practice of Vodou.[483] Mob attacks on Vodouists followed in the wake of the earthquake,[484] and again in the wake of the 2010 cholera outbreak.[485]

Haitian emigration began in 1957 as largely upper and middle-class Haitians fled Duvalier's government, and intensified after 1971 when many poorer Haitians also tried to escape abroad.[486] Many of these migrants took Vodou with them.[487] In the U.S., Vodou has attracted non-Haitians, especially African Americans and migrants from other parts of the Caribbean region.[381] There, Vodou has syncretized with other religious systems such as Santería and Espiritismo.[381] In the U.S., those seeking to revive Louisiana Voodoo during the latter part of the 20th century initiated practices that brought the religion closer to Haitian Vodou or Santería that Louisiana Voodoo appears to have been early in that century.[488]

Demographics

It is difficult to determine how many Haitians practice Vodou, largely because the country has never had an accurate census and many Vodouists will not openly admit they practice the religion.[489] It is nevertheless the majority religion of Haiti,[490] for most Haitians practice both Vodou and Roman Catholicism.[28] An often used joke about Haiti holds that the island's population is 85% Roman Catholic, 15% Protestant, and 100% Vodou.[491] Even some of those who reject Vodou acknowledge its close associations with Haitian identity.[23] In the mid-20th century Métraux noted that Vodou was practiced by the majority of peasants and urban proletariat in Haiti.[492] An estimated 80% of Haitians practice Vodou;[493] in 1992, Desmangles put the number of Haitian practitioners at six million.[494] Not all take part in the religion at all times, but many will turn to the assistance of Vodou priests and priestesses when in times of need.[495]

Individuals learn about the religion through their involvement in its rituals, either domestically or at the temple, rather than through special classes.[496] Children learn how to take part in the religion largely from observing adults.[257] Vodou does not focus on proselytizing;[497] according to Brown, it has "no pretensions to the universal."[490] It has nevertheless spread beyond Haiti, including to other Caribbean islands such as the Dominican Republic, Cuba, and Puerto Rico, but also to France and to the United States.[498] Major ounfòs exist in U.S. cities such as Miami, New York City, Washington, DC, Boston, and Oakland, California.[499]

Reception

Various scholars describe Vodou as one of the world's most maligned and misunderstood religions.[500] Its reputation is notorious;[501] in broader Anglophone and Francophone society, it has been widely associated with sorcery, witchcraft, and black magic.[502] In U.S. popular culture, for instance, Haitian Vodou is usually portrayed as destructive and malevolent,[503] attitudes often linked with anti-black racism.[78] Non-practitioners have often depicted Vodou in literature, theater, and film;[504] in many cases, such as the films White Zombie (1932) and London Voodoo (2004), these promote sensationalist views of the religion.[505] The lack of any central Vodou authority has hindered efforts to combat these negative representations.[506]

Humanity's relationship with the lwa has been a recurring theme in Haitian art,[309] and the Vodou pantheon was a major topic for the mid-20th century artists of the "Haitian Renaissance."[507] Art collectors began to take an interest in Vodou ritual paraphernalia in the late 1950s, and by the 1970s an established market for this material had emerged,[508] with some material being commodified for sale abroad.[509] Exhibits of Vodou ritual material have been displayed abroad; the Fowler Museum's exhibit on "Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou" for instance traveled the U.S. for three years in the 1990s.[510] Vodou has appeared in Haitian literature,[511] and has also influenced Haitian music, as with the rock band Boukman Eksperyans,[512] while theatre troupes have performed simulated Vodou rituals for audiences outside Haiti.[513] Documentaries focusing on Vodou have appeared[514]—such as Maya Deren's 1985 film Divine Horsemen[515][516] or Anne Lescot and Laurence Magloire's 2002 work Of Men and Gods[517]—which have in turn encouraged some viewers to take a practical interest in the religion.[518]

See also

- Haitian mythology

- Haitian Vodou art

- Voodoo in popular culture

References

Notes

Citations

- Beauvoir-Dominique 1995, p. 153.

- Métraux 1972.

- Michel 1996, p. 280.

- Courlander 1988, p. 88.

- Corbett, Bob (16 July 1995). "Yet more on the spelling of Voodoo". www.hartford-hwp.com. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- Desmangles 1992, p. 2; Desmangles 2012, p. 27; Thylefors 2009, p. 74.

- Cosentino 1996, p. 1; Michel 1996, p. 293.

- Germain 2011, p. 254.

- Desmangles 1992, p. 93.

- Desmangles 1992, pp. xi, 1.

- Cosentino 1995a, p. 29.

- Cosentino 1995a, p. 26; Derby 2015, p. 396.

- Derby 2015, p. 397.

- Desmangles 1990, p. 476; Desmangles 1992, p. 7; Hammond 2012, p. 64; Derby 2015, p. 396.

- Desmangles 1990, p. 476; Desmangles 1992, p. 8.

- Mintz & Trouillot 1995, p. 123.

- Mintz & Trouillot 1995, p. 128.

- McAlister 1995, p. 308.

- Blier 1995, p. 84.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 117.

- Desmangles 1992, p. 172.

- Fandrich 2007, p. 782.

- Thylefors 2009, p. 74.

- Johnson 2002, p. 9.

- Cosentino 1995a, p. 26; Thompson 1995, p. 92.

- Desmangles 1990, p. 480; Desmangles 1992, p. xii; Thylefors 2009, p. 74; Derby 2015, p. 399.

- McAlister 1995, p. 319.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 120.

- Brown 1991, p. 49; Ramsey 2011, p. 6; Hebblethwaite 2015, p. 5.

- Mintz & Trouillot 1995, p. 123; Boutros 2011, p. 1984.

- Desmangles 1990, p. 480; Brown 1991, p. 221.

- Desmangles 1990, p. 480; Desmangles 1992, p. 63.

- Boutros 2011, p. 1984; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 118.

- Brown 1991, p. 221; Desmangles 1992, p. 4.

- Desmangles 1990, p. 480; Mintz & Trouillot 1995, p. 123.

- Cosentino 1995a, p. 53.

- Métraux 1972, pp. 19–20; Desmangles 1992, pp. 4, 36; Cosentino 1995a, p. 53; Mintz & Trouillot 1995, pp. 123–124; Ramsey 2011, p. 7.

- Ramsey 2011, p. 7.

- Desmangles 1992, p. 63; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 119.

- Métraux 1972, p. 61.

- Michel 1996, p. 285.

- Michel 1996, p. 285; Basquiat 2004, p. 1; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 154.

- Brown 1991, pp. 111, 241; Cosentino 1995a, p. 36; Cosentino 1995b, pp. 253, 260.

- Basquiat 2004, pp. 25–26.

- Cosentino 1995a, p. 44.

- Hagedorn 2001, p. 133; Viddal 2012, p. 231.

- Emore 2021, p. 59.

- Viddal 2012, p. 226.

- Cosentino 1995a, p. 43.

- Cosentino 1995a, p. 32.

- Blier 1995, p. 86; Cosentino 1995a, p. 30.

- Blier 1995, p. 61.

- Desmangles 1992, p. xi; Ramsey 2011, pp. 6–7.

- Ramsey 2011, p. 7; Derby 2015, p. 407.

- Brown 1995, p. 205; Derby 2015, p. 407.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 116.

- Derby 2015, p. 407.

- Desmangles 1992, pp. xi–xii; Ramsey 2011, p. 6.

- Ramsey 2012.

- Desmangles 1992, p. xi; Ramsey 2011, p. 258.

- Desmangles 1992, p. xii.

- Ramsey 2011, p. 10; Derby 2015, p. 407.

- Desmangles 1992, p. xi.

- Long 2002, p. 87; Fandrich 2007, pp. 779, 780.

- Desmangles 2012, pp. 26, 27.

- Brown 1991, p. 111; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 120; Hebblethwaite 2015, p. 5.

- Michel 1996, p. 288; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 120.

- Desmangles 1992, p. 159.

- Ramsey 2011, p. 7; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 120.

- Desmangles 1992, p. 168; Ramsey 2011, p. 7.

- Desmangles 1992, p. 160; Ramsey 2011, p. 7; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 120.

- Desmangles 1992, p. 97.

- Desmangles 1992, p. 96.

- Desmangles 1992, pp. 4, 162; Ramsey 2011, p. 7.

- Brown 1991, p. 6; Desmangles 1992, p. 168.

- Métraux 1972, p. 82.

- Desmangles 1992, p. 161; Ramsey 2011, p. 7.

- Brown 1991, p. 111.

- Hebblethwaite 2015, p. 5.

- Desmangles 1992, p. 3; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, pp. 117, 120.

- Métraux 1972, p. 84.

- Desmangles 1992, p. 98.

- Métraux 1972, pp. 95, 96; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 117.

- Brown 1991, p. 4; Michel 1996, p. 288; Ramsey 2011, p. 7.

- Desmangles 1992, p. 81.

- Brown 1991, p. 6.

- Métraux 1972, p. 92; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 120.

- Métraux 1972, p. 92.

- Métraux 1972, p. 97.

- Métraux 1972, p. 99.

- Métraux 1972, p. 28.

- Métraux 1972, pp. 84–85.

- Métraux 1972, p. 91.

- Houlberg 1995, pp. 267–268.

- Métraux 1972, pp. 66, 120.

- Métraux 1972, p. 87; Brown 1991, p. 100; Desmangles 1992, p. 94; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 120.

- Métraux 1972, p. 87.

- Desmangles 1992, p. 94; Houlberg 1995, p. 279.

- Métraux 1972, pp. 39, 86; Brown 1991, p. 100; Apter 2002, p. 238; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 121.

- Métraux 1972, p. 39; Desmangles 1992, p. 95.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 125.

- Apter 2002, p. 240.

- Apter 2002, p. 238.

- Apter 2002, p. 239.

- Apter 2002, p. 248.

- Métraux 1972, p. 101; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 125.

- Métraux 1972, p. 102; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 125.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 132.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 133.

- Métraux 1972, pp. 146–149; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 132.

- Métraux 1972, p. 102; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 126.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 126.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, pp. 126–127.

- Métraux 1972, p. 110; Brown 1991, p. 220; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 129.

- Brown 1991, p. 220; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 131.

- Métraux 1972, p. 108; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 127.

- Brown 1991, p. 36; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 127.

- Brown 1991, p. 156.

- Métraux 1972, pp. 107–108.

- Brown 1991, p. 95; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 131.

- Métraux 1972, p. 109; Brown 1991, p. 101.

- Métraux 1972, p. 106.

- Métraux 1972, pp. 106–107.

- Métraux 1972, p. 105; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 127.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 127.

- Métraux 1972, p. 105.

- Cosentino 1995c, pp. 405–406.

- Métraux 1972, p. 112; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 128.

- Brown 1991, p. 198; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 128.

- Brown 1991, p. 380; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 128.

- Métraux 1972, p. 114.

- Métraux 1972, p. 113; Brown 1991, pp. 357–358.

- Beasley 2010, p. 43.

- Métraux 1972, p. 113; Cosentino 1995a, p. 52; Cosentino 1995c, p. 403.

- Brendbekken 2002, p. 42; Ramsey 2011, p. 8.

- Brown 1991, p. 61; Ramsey 2011, p. 8.

- Métraux 1972, p. 101; Desmangles 1992, p. 11.

- Cosentino 1995a, p. 35; Ramsey 2011, p. 8; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, pp. 130–131.

- Brown 1991, p. 275; Desmangles 1992, pp. 10–11, 130; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, pp. 127–128.

- Métraux 1972, p. 146; Houlberg 1995, p. 271; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 133.

- Desmangles 1990, p. 475.

- Cosentino 1995b, p. 253.

- Polk 1995, pp. 326–327.

- Brown 1995, p. 215.

- Desmangles 1992, p. 64.

- Desmangles 1992, p. 66.