Siren (mythology)

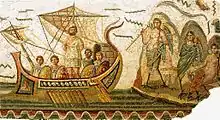

In Greek mythology, the sirens (Ancient Greek: singular: Σειρήν, Seirḗn; plural: Σειρῆνες, Seirênes) were humanlike beings with alluring voices; they appear in a scene in the Odyssey in which Odysseus saves his crew's lives.[1] Roman poets placed them on some small islands called Sirenum scopuli. In some later, rationalized traditions, the literal geography of the "flowery" island of Anthemoessa, or Anthemusa,[2] is fixed: sometimes on Cape Pelorum and at others in the islands known as the Sirenuse, near Paestum, or in Capreae.[3] All such locations were surrounded by cliffs and rocks.

Sirens continued to be used as a symbol for the dangerous temptation embodied by women regularly throughout Christian art of the medieval era.

Nomenclature

The etymology of the name is contested. Robert S. P. Beekes has suggested a Pre-Greek origin.[4] Others connect the name to σειρά (seirá, "rope, cord") and εἴρω (eírō, "to tie, join, fasten"), resulting in the meaning "binder, entangler",[5] i.e. one who binds or entangles through magic song. This could be connected to the famous scene of Odysseus being bound to the mast of his ship, in order to resist their song.[6]

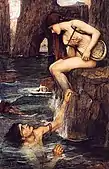

Sirens were later often used as a synonym for mermaids, and portrayed with upper human bodies and fish tails. This combination became iconic in the medieval period.[7][8] The circumstances leading to the commingling involve the treatment of sirens in the medieval Physiologus and bestiaries, both iconographically,[9] as well as textually in translations from Latin to vulgar languages,[lower-alpha 1][10] as described below.

Iconography

Classical iconography

.jpg.webp)

The sirens of Greek mythology first appeared in Homer's Odyssey, where Homer did not provide any physical descriptions, and their visual appearance was left to the readers' imagination. It was Apollonius of Rhodes in Argonautica (3rd century BC) who described the sirens in writing as part woman and part bird.[lower-alpha 2][11][12] By the 7th century BC, sirens were regularly depicted in art as human-headed birds.[13] They may have been influenced by the ba-bird of Egyptian religion. In early Greek art, the sirens were generally represented as large birds with women's heads, bird feathers and scaly feet. Later depictions shifted to show sirens with human upper bodies and bird legs, with or without wings. They were often shown playing a variety of musical instruments, especially the lyre, kithara, and aulos.[14]

The tenth-century Byzantine dictionary Suda stated that sirens (Greek: Σειρῆνας)[lower-alpha 3] had the form of sparrows from their chests up, and below they were women or, alternatively, that they were little birds with women's faces.[15]

Originally, sirens were shown as male or female, but the male siren disappeared from art around the fifth century BC.[16]

Early siren-mermaids

Some surviving Classical period examples had already depicted the siren as mermaid-like.[7] The sirens are depicted as mermaids or "tritonesses" in examples dating to the 3rd century BC, including an earthenware bowl found in Athens[19][21] and a terracotta oil lamp possibly from the Roman period.[7]

%252C_f.47v_-_BL_Harley_MS_4751.jpg.webp)

The first known literary attestation of siren as a "mermaid" appeared in the Anglo-Latin catalogue Liber Monstrorum (early 8th century AD), where it says that sirens were "sea-girls... with the body of a maiden, but have scaly fishes' tails".[22][23]

Medieval Iconography

As will be explained below, the siren appeared in a number of illustrated manuscripts of the Physiologus and its successors called the bestiaries. The siren was depicted as a half-woman and half-fish mermaid in the 9th century Berne Physiologus,[24] as an early example, but continued to be illustrated with both bird-like parts (wings, clawed feet) and fish-like tail.[25]

Modern paintings

Classical literature

Family tree

Although a Sophocles fragment makes Phorcys their father,[26] when sirens are named, they are usually as daughters of the river god Achelous,[27] either by the Muse Terpsichore,[28] Melpomene[29] or Calliope[30] or lastly by Sterope, daughter of King Porthaon of Calydon.[31]

In Euripides's play Helen (167), Helen in her anguish calls upon "Winged maidens, daughters of the Earth (Chthon)." Although they lured mariners, the Greeks portrayed the sirens in their "meadow starred with flowers" and not as sea deities. Epimenides claimed that the sirens were children of Oceanus and Ge.[32] Sirens are found in many Greek stories, notably in Homer's Odyssey.

List of sirens

Their number is variously reported as from two to eight.[33] In the Odyssey, Homer says nothing of their origin or names, but gives the number of the sirens as two.[34] Later writers mention both their names and number: some state that there were three, Peisinoe, Aglaope and Thelxiepeia[35] or Aglaonoe, Aglaopheme and Thelxiepeia;[36] Parthenope, Ligeia, and Leucosia;[37] Apollonius followed Hesiod gives their names as Thelxinoe, Molpe, and Aglaophonos;[38] Suidas gives their names as Thelxiepeia, Peisinoe, and Ligeia;[39] Hyginus gives the number of the sirens as four: Teles, Raidne, Molpe, and Thelxiope;[40] Eustathius states that they were two, Aglaopheme and Thelxiepeia;[41] an ancient vase painting attests the two names as Himerope and Thelxiepeia.

Their individual names are variously rendered in the later sources as Thelxiepeia/Thelxiope/Thelxinoe, Molpe, Himerope, Aglaophonos/Aglaope/Aglaopheme, Pisinoe/Peisinoë/Peisithoe, Parthenope, Ligeia, Leucosia, Raidne, and Teles.[42][43][44][45]

- Molpe (Μολπή)

- Thelxiepeia (Θελξιέπεια) or Thelxiope (Θελξιόπη) "eye pleasing")

| Relation | Names | Sources | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parentage | Oceanus and Gaea | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Chthon | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Achelous and Terpsichore | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Achelous and Melpomene | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Achelous and Sterope | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Achelous and Calliope | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Phorcys | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Number | 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 4 | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Individual name | Thelxinoe or Thelxiope | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Thelxiepe | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Thelxiep(e)ia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Aglaophonus | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Aglaope | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Aglaopheme | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Aglaonoe | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Molpe | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Peisinoe or Pisinoe | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Parthenope | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Leucosia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Raidne | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Teles | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ligeia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Himerope | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

Demeter

_01.jpg.webp)

According to Ovid (43 BC–17 AD), the sirens were the companions of young Persephone.[46] Demeter gave them wings to search for Persephone when she was abducted by Hades. However, the Fabulae of Hyginus (64 BC–17 AD) has Demeter cursing the sirens for failing to intervene in the abduction of Persephone. According to Hyginus, Sirens were fated to live only until the mortals who heard their songs were able to pass by them.[47]

The Muses

One legend says that Hera, queen of the gods, persuaded the sirens to enter a singing contest with the Muses. The Muses won the competition and then plucked out all of the sirens' feathers and made crowns out of them.[48] Out of their anguish from losing the competition, writes Stephanus of Byzantium, the sirens turned white and fell into the sea at Aptera ("featherless"), where they formed the islands in the bay that were called Leukai ("the white ones", modern Souda).[49]

Argonautica

In the Argonautica (third century BC), Jason had been warned by Chiron that Orpheus would be necessary in his journey. When Orpheus heard their voices, he drew out his lyre and played his music more beautifully than they, drowning out their voices. One of the crew, however, the sharp-eared hero Butes, heard the song and leapt into the sea, but he was caught up and carried safely away by the goddess Aphrodite.[11]

Odyssey

Odysseus was curious as to what the sirens sang to him, and so, on the advice of Circe, he had all of his sailors plug their ears with beeswax and tie him to the mast. He ordered his men to leave him tied tightly to the mast, no matter how much he might beg. When he heard their beautiful song, he ordered the sailors to untie him but they bound him tighter. When they had passed out of earshot, Odysseus demonstrated with his frowns to be released.[50] Some post-Homeric authors state that the sirens were fated to die if someone heard their singing and escaped them, and that after Odysseus passed by they therefore flung themselves into the water and perished.[51]

Pliny

The first-century Roman historian Pliny the Elder discounted sirens as a pure fable, "although Dinon, the father of Clearchus, a celebrated writer, asserts that they exist in India, and that they charm men by their song, and, having first lulled them to sleep, tear them to pieces."[52]

Sirens and death

Statues of sirens in a funerary context are attested since the classical era, in mainland Greece, as well as Asia Minor and Magna Graecia. The so-called "Siren of Canosa"—Canosa di Puglia is a site in Apulia that was part of Magna Graecia—was said to accompany the dead among grave goods in a burial. She appeared to have some psychopomp characteristics, guiding the dead on the afterlife journey. The cast terracotta figure bears traces of its original white pigment. The woman bears the feet, wings and tail of a bird. The sculpture is conserved in the National Archaeological Museum of Spain, in Madrid. The sirens were called the Muses of the lower world. Classical scholar Walter Copland Perry (1814–1911) observed: "Their song, though irresistibly sweet, was no less sad than sweet, and lapped both body and soul in a fatal lethargy, the forerunner of death and corruption."[53] Their song is continually calling on Persephone.

The term "siren song" refers to an appeal that is hard to resist but that, if heeded, will lead to a bad conclusion. Later writers have implied that the sirens were cannibals, based on Circe's description of them "lolling there in their meadow, round them heaps of corpses rotting away, rags of skin shriveling on their bones."[54] As linguist Jane Ellen Harrison (1850–1928) notes of "The Ker as siren": "It is strange and beautiful that Homer should make the sirens appeal to the spirit, not to the flesh."[55] The siren song is a promise to Odysseus of mantic truths; with a false promise that he will live to tell them, they sing,

Once he hears to his heart's content, sails on, a wiser man.

We know all the pains that the Greeks and Trojans once endured

on the spreading plain of Troy when the gods willed it so—

all that comes to pass on the fertile earth, we know it all![56]

"They are mantic creatures like the Sphinx with whom they have much in common, knowing both the past and the future", Harrison observed. "Their song takes effect at midday, in a windless calm. The end of that song is death."[57] That the sailors' flesh is rotting away, suggests it has not been eaten. It has been suggested that, with their feathers stolen, their divine nature kept them alive, but unable to provide food for their visitors, who starved to death by refusing to leave.[58]

Early Christian to Medieval

Late antiquity

By the fourth century, when pagan beliefs were overtaken by Christianity, the belief in literal sirens was discouraged

Saint Jerome, who produced the Latin Vulgate version of the bible, used the word sirens to translate Hebrew tannīm ("jackals") in the Book of Isaiah 13:22, and also to translate a word for "owls" in the Book of Jeremiah 50:39.

The siren is allegorically described as a beautiful courtesan or prostitute, who sings pleasant melody to men, and is symbolic vice of Pleasure in the preaching of Clement of Alexandria (2nd century).[59] Later writers such as Ambrose (4th century) reiterated the notion that the siren stood as symbol or allegory for worldly temptations.[60] and not an endorsement of the Greek myth.

Isidorus

The early Christian euhemerist interpretation of mythologized human beings received a long-lasting boost from the Etymologiae by Isidore of Seville (c. 560–636):

They [the Greeks] imagine that "there were three sirens, part virgins, part birds," with wings and claws. "One of them sang, another played the flute, the third the lyre. They drew sailors, decoyed by song, to shipwreck. According to the truth, however, they were prostitutes who led travelers down to poverty and were said to impose shipwreck on them." They had wings and claws because Love flies and wounds. They are said to have stayed in the waves because a wave created Venus.[61]

The allegorical texts

The siren and the onocentaur, two hybrid creatures, appear as the subject of a single chapter in the Physiologus,[62] owing to the fact that they appear together in the Septuagint translation of the aforementioned Isaiah 13:21–22, and 34:14.[63][lower-alpha 4] They also appear together in some Latin bestiaries of the First Family subgroup called B-Isidore ("B-Is").[66][62]

The miniatures

The siren's bird-like description from classical sources was retained in the Latin version of the Physiologus (6th century) and a number of subsequent bestiaries into the 13th century,[71][65] but at some time during the interim, the mermaid shape was introduced to this body of works.[72]

- (As woman-fish or mermaid)

The siren was illustrated as a woman-fish (mermaid) in the Bern Physiologus dated to the mid 9th century, even though this contradicted the accompanying text which described it as avian.[24] An English-made Latin bestiary dated 1220–1250 also depicted a group of sirens as mermaids with fishtails swimming in the sea, even though the text stated they resembled winged fowl (volatilis habet figuram) down to their feet.[78][lower-alpha 5]

Illustrating the siren as a pure mermaid became commonplace in the "second family" bestiaries, and she was shown holding a musical instrument in the classical tradition, but also sometimes holding apparently an eel-fish.[80] An example of the siren-mermaid holding such a fish is found in one of the earlier codices in this group, dated the late 12th century.[lower-alpha 6][69]

- (As bird-like)

A counterexample is also given where the illustrated sirens (group of three) are bird-like, conforming to the text.[84]

- (As hybrid)

The siren was sometimes drawn as a hybrid with a human torso, a fish-like lower body, and bird-like wings and feet.[85][86] While in the Harley 3244 (cf. fig. top right) the wings sprout from around the shoulders, in other hybrid types, the style places the siren's wings "hanging at the waist".[88][91]

- (Comb and mirror)

Also, a siren may be holding a comb,[62][92] or a mirror.[94]

Thus the comb and mirror, which are now emblematic of mermaids across Europe, derive from the bestiaries that describe the siren as a vain creature requiring those accoutrements.[95][96]

Verse bestiaries

Later, bestiary texts appeared which were modified to accommodate the artistic conventions.[97]

It is explained that the siren's "other part" may be "like fish or like bird" in Guillaume le clerc's Old French verse bestiary (1210 or 1211),[100][95] as well as Philippe de Thaun's Anglo-Norman verse bestiary (c. 1121–1139).[101][97]

Derivative literature

There also appeared medieval works that conflated sirens with mermaids while citing Physiologus as their source.[102][103]

Italian poet Dante Alighieri depicts a siren in Canto 19 of Purgatorio, the second canticle of the Divine Comedy. Here, the pilgrim dreams of a female that is described as "stuttering, cross-eyed, and crooked on her feet, with stunted hands, and pallid in color."[104] It is not until the pilgrim "gazes" upon her that she is turned desirable and is revealed by herself to be a siren.[104] This siren then claims that she "turned Ulysses from his course, desirous of my / song, and whoever becomes used to me rarely / leaves me, so wholly do I satisfy him!"[104] Given that Dante did not have access to the Odyssey, the siren's claim that she turned Ulysses from his course is inherently false because the sirens in the Odyssey do not manage to turn Ulysses from his path.[105] Ulysses and his men were warned by Circe and prepared for their encounter by stuffing their ears full of wax,[105][106] except for Ulysses, who wishes to be bound to the ship's mast as he wants to hear the siren's song.[106] Scholars claim that Dante may have "misinterpreted" the siren's claim from an episode in Cicero's De finibus.[105] The pilgrim's dream comes to an end when a lady "holy and quick"[104] who had not yet been present before suddenly appears and says, "O Virgil, Virgil, who is this?"[104] Virgil, the pilgrim's guide, then steps forward and tears the clothes from the siren's belly which, "awakened me [the pilgrim] with the stench that issued from it."[104] This marks ending the encounter between the pilgrim and the siren.

In Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae (c. 1136), Brutus of Troy encounters sirens at the Pillars of Hercules on his way to Britain to fulfil a prophecy that he will establish an empire there. The sirens surround and nearly overturn his ships, until Brutus escapes to the Tyrrhenian Sea.[107]

Renaissance

By the time of the Renaissance, female court musicians known as courtesans filled the role of an unmarried companion, and musical performances by unmarried women could be seen as immoral. Seen as a creature who could control a man's reason, female singers became associated with the mythological figure of the siren, who usually took a half-human, half-animal form somewhere on the cusp between nature and culture.[108]

Leonardo da Vinci wrote of them in his notebooks, stating "The siren sings so sweetly that she lulls the mariners to sleep; then she climbs upon the ships and kills the sleeping mariners."

Age of Exploration

however, in the 17th century, some Jesuit writers began to assert their actual existence, including Cornelius a Lapide, who said of woman, "her glance is that of the fabled basilisk, her voice a siren's voice—with her voice she enchants, with her beauty she deprives of reason—voice and sight alike deal destruction and death."[109] Antonio de Lorea also argued for their existence, and Athanasius Kircher argued that compartments must have been built for them aboard Noah's Ark.[110]

Late Modernity (1801-1900)

Charles Burney expounded c. 1789, in A General History of Music: "The name, according to Bochart, who derives it from the Phoenician, implies a songstress. Hence it is probable, that in ancient times there may have been excellent singers, but of corrupt morals, on the coast of Sicily, who by seducing voyagers, gave rise to this fable."[111]

John Lemprière in his Classical Dictionary (1827) wrote, "Some suppose that the sirens were a number of lascivious women in Sicily, who prostituted themselves to strangers, and made them forget their pursuits while drowned in unlawful pleasures. The etymology of Bochart, who deduces the name from a Phoenician term denoting a songstress, favors the explanation given of the fable by Damm.[112] This distinguished critic makes the sirens to have been excellent singers, and divesting the fables respecting them of all their terrific features, he supposes that by the charms of music and song they detained travellers, and made them altogether forgetful of their native land."[113]

In fine art

English artist William Etty portrayed the sirens as young women in fully human form in his 1837 painting The Sirens and Ulysses, a practice copied by future artists.[114]

Odysseus and the Sirens (1867) by Léon Belly

Odysseus and the Sirens (1867) by Léon Belly The Siren (1888) by Edward Armitage

The Siren (1888) by Edward Armitage.jpg.webp) Ulysses and the Sirens (1891) by John William Waterhouse

Ulysses and the Sirens (1891) by John William Waterhouse The Siren (c. 1900) by John William Waterhouse

The Siren (c. 1900) by John William Waterhouse Ulysses and the Sirens (c. 1909) by Herbert James Draper

Ulysses and the Sirens (c. 1909) by Herbert James Draper

See also

- Alkonost

- Banshee

- Circe

- Enchanted Moura

- Harpy

- Heloi

- Hulder

- Iara

- Kelpie

- Les Démoniaques

- Lorelei

- Lilith

- Melusine

- Mermaid

- Merman

- Merrow

- Morgen

- Naiad

- Nix

- Nymph

- Ondine

- Pincoya

- Rusalka

- Selkie

- Seraphim

- Sihuanaba

- Sirin

- Slavic fairies

- Song to the Siren

- Succubus

- Syrenka

- Trauco

- Ubume

- Uchek Langmeidong

- Undine

- Water sprite

- List of avian humanoids

Explanatory notes

- Old High German meremanniu in the OHG Physiologus, and Middle English merman 'mermaid', in the ME bestiary.

- Argonautica 3.891ff. Seaton tr. (1912): "and at that time they were fashioned in part like birds and in part like maidens to behold"

- The headword is accusative plural (Commentary to the Sudas entry).

- The sirens (seirenes) do figure in the earliest surviving versions (version G, Μ Γ and others).[64] But the siren apparently did not figure in the earlier Greek version of the Physiologos (4th century, preserved by Epiphanius) nor the Armenian translation from Greek originals.[65]

- There is another entry for "siren", as a winged white serpent of Arabia.[79]

- Brit. Lib. Add. 11283, late 12c., Clark (2006), p. 21, fol. 20v[81][82]

References

- Scholiast on Homer, Odyssey 12.168 with Hesiod as the authority, translated by Evelyn-White

- "We must steer clear of the sirens, their enchanting song, their meadow starred with flowers" is Robert Fagles's rendering of Odyssey 12.158–9.

- Strabo i. 22; Eustathius of Thessalonica's Homeric commentaries §1709; Servius I.e.

- Robert S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 1316 f.

- Cf. the entry in Wiktionary and the entry in the Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Homer, Odyssey, book 12.

- Harrison, Jane Ellen (1882). Myths of the Odyssey in Art and Literature. London: Rivingtons. pp. 169–170, Plate 47a.

- Mittman, Asa Simon; Dendle, Peter J (2016). The Ashgate research companion to monsters and the monstrous. London: Routledge. p. 352. ISBN 9781351894326. OCLC 1021205658.

- Holford-Strevens (2006), pp. 31–34.

- Pakis (2010), pp. 126–127.

- Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica IV, 891–919. Seaton, R. C. ed., tr. (2012), p. 354ff.

- Knight, Virginia (1995). The Renewal of Epic: Responses to Homer in the Argonautica of Apollonius. E. J. Brill. p. 201. ISBN 9789004329775.

- Holford-Strevens (2006), pp. 17–18.

- Tsiafakis, Despoina (2003). "Pelora: Fabulous Creatures and/or Demons of Death?". The Centaur's Smile: The Human Animal in Early Greek Art: 73–104.

- "Suda on-line". Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2010-01-30.

- "CU Classics – Greek Vase Exhibit – Essays – Sirens". www.colorado.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-06-25. Retrieved 2017-10-20.

- Rotroff, Susan I. (1982). Hellenistic Painted Potter: Athenian and Imported Moldmade Bowls, The Athenian Agora 22. American School of Classical Studies at Athens. p. 67, #190; Plates 35, 80. ISBN 978-0876612224.

- Thompson, Homer A. (July–September 1948). "The Excavation of the Athenian Agora Twelfth Season" (PDF). Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. 17 (3, The Thirty-Fifth Report of the American Excavation in the Athenian Agora): 161–162 and Fig. 5. doi:10.2307/146874. JSTOR 146874.

- A moldmade Megarian bowl excavated in the Ancient Agora of Athens, catalogued P 18,640. Rotroff (1982), p. 67[17] apud Holford-Strevens (2006), p. 29; Thompson (1948), pp. 161–162 and Fig. 5[18]

- Waugh, Arthur (1960). "The Folklore of the Merfolk". Folklore. 71 (2): 78–79. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1960.9717221. JSTOR 1258382.

- A terracotta piece of a "mourning siren", 250 BC, according to Waugh.[20]

- Holford-Strevens (2006), p. 29, quoting Orchard (1995)'s translation.

- Orchard, Andy. "Etext: Liber monstrorum (fr the Beowulf Manuscript)". members.shaw.ca. Archived from the original on 2005-01-18.

- Berne, Bürgerbibliotek Cod. 318. fol. 13v. Rubric: "De natura serena et honocentauri".[73]

- Holford-Strevens (2006), pp. 3134.

- Sophocles, fragment 861; Fowler, p. 31; Plutarch, Quaestiones Convivales – Symposiacs, Moralia 9.14.6

- Ovid XIV, 88.

- Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica 4.892; Nonnus, Dionysiaca 13.309; Tzetzes, Chiliades, 1.14, line 338 & 348

- Apollodorus, Epitome 7.18; Hyginus, Fabulae Preface, 125 & 141; Tzetzes, Chiliades, 1.14, line 339 & 348

- Servius, Commentary on Virgil's Aeneid 5.864

- Apollodorus, 1.7.10

- Epimenides, fr. 8, suppl = Fowler, p. 13 (2013)

- Page, Michael; Ingpen, Robert (1987). Encyclopedia of Things That Never Were. New York: Viking Penguin Inc. p. 211. ISBN 0-670-81607-8.

- Homer, Odyssey 12.52

- Apollodorus, Epitome 7.18; Tzetzes on Lycophron, 7l2

- Tzetzes, Chiliades 6.40

- Eustathius, l.c. cit.; Servius on Virgil, Georgics 4.562; Strabo, 5.246, 252; Lycophron, 720-726; Tzetzes, Chiliades 1.14, line 337 & 6.40

- Scholia on Apollonius, 4.892 = Hesiod, Ehoiai fr. 47

- Suda s.v. Seirenas

- Apollodorus, Epitome 7.18; Hyginus, Fabulae Preface p. 30, ed. Bunte

- Eustathius on Homer 1709

- Linda Phyllis Austern, Inna Naroditskaya, Music of the Sirens, Indiana University Press, 2006, p.18

- William Hansen, William F. Hansen, Classical Mythology: A Guide to the Mythical World of the Greeks and Romans, Oxford University Press, 2005, p.307

- Ken Dowden, Niall Livingstone, A Companion to Greek Mythology, Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, p.353

- Mike Dixon-Kennedy, Encyclopedia of Greco-Roman Mythology, ABC-Clio, 1998, p.281

- Ovid, Metamorphoses V, 551.

- Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 141 (trans. Grant).

- Lemprière 768.

- Caroline M. Galt, "A marble fragment at Mount Holyoke College from the Cretan city of Aptera", Art and Archaeology 6 (1920:150).

- Odyssey XII, 39.

- Hyginus, Fabulae 141; Lycophron, Alexandra 712 ff.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History X, 70.

- Perry, "The sirens in ancient literature and art", in The Nineteenth Century, reprinted in Choice Literature: a monthly magazine (New York) 2 (September–December 1883:163).

- Odyssey 12.45–6, Fagles' translation.

- Harrison 198

- Odyssey 12.188–91, Fagles' translation.

- Harrison, 199.

- Liner notes to Fresh Aire VI by Jim Shey, Classics Department, University of Wisconsin

- Clement. Protrepticus. quoted in Druce (1915), p. 170

- Ambrose, Exposition of the Christian Faith, Book 3, chap. 1, 4.

- Grant, Robert McQueen (1999). Early Christians and Animals. London: Routledge, 120. Translation of Isidore, Etymologiae (c. 600–636 AD), Book 11, chap. 3 ("Portents"), 30.

- George & Yapp (1991), p. 99.

- Pakis (2010), p. 118.

- Pakis (2010), pp. 120–121.

- Mustard, Wilfred P. (1908). "Mermaid—Siren". Modern Language Notes. 23: 22. doi:10.2307/2916861. JSTOR 2916861.

- Pakis (2010), pp. 125–126.

- "Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms. Latin 6838 B". Mandragore. Retrieved 2022-09-10.

- "Workshop Bestiary MS M.81, fols. 16v–17r". Morgan Library and Museum. 27 February 2018. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- Druce (1915), pp. 174–175, Pl. X, No. 2.

- "British Library Sloane MS 278". British Library. Retrieved 2022-09-19., fol. 47r.

- Physiologus "B" text and its derivative. Holford-Strevens (2006), p. 29 et sqq.

- Holford-Strevens (2006), p. 31: There were "those who introduced the mermaid into the Latin Physiologus and the bestiaries thence derived".

- Leclercq, Jacqueline (February 1989). "De l'art antique à l'art médièval. A propos des sources du bestiaire carolingien et de se survivances à l'époque romane" [From ancient to mediaeval Art. On the sources of Carolingian bestiaries and their survival in the romance period]. Gazette des Beaux-Arts. 113: 88. doi:10.2307/596378. JSTOR 596378.

The chapter devoted to the Siren and the Centaur is an excellent example of this because the Siren is represented as a woman-fish whereas she is described in the form of a woman-bird..

(in French) (summary in English); Leclercq-Marx, Jacqueline (1997). "La sirène dans la pensée et dans l'art de l'Antiquité et du Moyen Âge: du mythe païen au symbole chrétien". Publication de la Classe des Beaux-Arts. Collection In-4O. Classe des beaux-arts, Académie royale de Belgique: 62ff. ISSN 0775-3276. - "Bodleian Library MS. Bodl. 764". Oxford University, the Bodleian Libraries. Retrieved 2022-09-09., fol. 074v.

- Hardwick (2011), p. 92.

- Holford-Strevens (2006), pp. 31–32, Fig. 1.4

- Barber, Richard, ed. (1993). "Sirens". Bestiary: Being an English Version of the Bodleian Library, Oxford M.S. Bodley 764 : with All the Original Miniatures Reproduced in Facsimile. Boydell Press. p. 1150. ISBN 9780851157535.

- Oxford, MS Bodley 764, fol. 74v.[74][75][76][77]

- Barber tr. (1993), p. 150.

- Clark (2006), p. 57 and n50.

- Clark (2006), p. 52 and Fig. 20.

- "British Library Add MS 11283". British Library. Retrieved 2022-09-06.

- Holford-Strevens (2006), pp. 31–32, Fig. 1.3

- Oxford, MS Bodley 602, fol. 10r. 12th century.[83]

- Harley 3244, and others MSS.; Clark (2006), p. 21

- Cambridge University Library, MS Ii. 4. 26, fol. 39r. Holford-Strevens (2006), pp. 33–34

- Holford-Strevens (2006), p. 33, Fig. 1.5

- Cambridge University Library Ii.4.26, fol. 39v.[87]

- "Ms. 100 (2007.16), fol. 14. Sirens. about 1250–1260". Getty Museum. Retrieved 2022-09-10.. "serene" fol. 20v

- Tandjung, Beverly (11 May 2018). "The Enchantress of the Medieval Bestiary". Getty Museum. Retrieved 2022-09-06.

- Compare Nothumberland bestiary (Getty MS 100)[89] (olim Alnwick bestiary, Alnwick Castle MS 447). Comment of "webbed feet" in the two examples[62] seems false for the CUL ms., while "webbed feet of an aquatic animal" is corroborated for the Northumberland bestiary.[90]

- Or there may be three sirens drawn, two holding fish and third a mirror, as in Getty MS. 100 (olim Alnwick ms.)[89][62] A similar composition occurs on the Morgan M.81,[68] cf. fig. right.

- "Detailed record for Royal 2 B VII (Queen Mary Psalter)". British Library. Retrieved 2022-09-06., fol. 96v

- British Library Ms. Royal 2.B.Vii, fol. 96v.[62][93]

- Waugh (1960), p. 77.

- Chunko-Dominguez, Betsy (2017). English Gothic Misericord Carvings: History from the Bottom Up. BRILL. pp. 82–84. ISBN 9789004341203.

- Holford-Strevens (2006), p. 34.

- Muratova, Xénia; Poirion, Daniel, eds. (1988). Le bestiaire. Translated by Marie-France Dupuis; George E. J. Powell. Philippe Lebaud. p. 33. ISBN 9782865940400.

- Schafer, Edward H. (September 1930). "The Physiologus of Bern: A Survival of Alexandrian Style in a Ninth Century". The Art Bulletin. 12 (3). Fig. 22 and p. 249. JSTOR 3050780.

- "l'altre partie est figuree / Come peisson ou con oisel" (vv. 1058–1059).[98][99]

- Philippe de Thaun (1841). Wright, Thomas (ed.). The Bestiary of Philipee de Thaun. Popular Treatises on Science Written During the Middle Ages: In Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Norman and English. London: Historical Society of Science. p. 98., fol. 59r, Cotton MS Nero A V digitized @ British Library.

- Bartholomew Anglicus, De proprietatibus rerum XCVII, c.1240, "And Physiologus saith it is a beast of the sea, wonderly shapen as a maid from the navel upward and a fish from the navel downward"; quoted in translation by Mustard (1908), p. 22

- Hugh of St. Victor (d.1240), De bestiis et aliis rebus XCVII, quoted in Latin by Mustard (1908), p. 23, and in translation by Holford-Strevens (2006), p. 32: "sirens.., as the Physiologus describes them have a woman's form above down to the navel, but their lower part down to the feet has the shape of a fish". The work continues "excerpts from Servius and Isidore" to say: "three Sirens, part maids, part fish, of whom one sang,..etc.". But despite attribution to Hugh, this work had so heavily interpolated that it has been actually a 16th century compilation, and dubbed a "problematic" bestiary. Cf. Clark (2006), pp. 10–11: Chapter 1: The Problematic De bestiis et aliis rebus.

- Dante Alighieri (1996–2013). The divine comedy of Dante Alighieri. Robert M. Durling, Ronald L. Martinez. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-508740-6. OCLC 32430822.

- Lectura Dantis: Purgatorio. Allen Mandelbaum, Anthony Oldcorn, Charles Ross. Berkeley: University of California Press. 2008. ISBN 978-0-520-94052-9. OCLC 193827830.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Homero, s. IX a. C. (2004). Odisea. Carlos García Gual, John Flaxman. Madrid: Alianza. ISBN 84-206-7750-7. OCLC 57058042.

- Geoffrey of Monmouth. . Historia Regum Britanniae. Chapter 12 – via Wikisource.

- Dunbar, Julie C. (2011). Women, Music, Culture. Routledge. p. 70. ISBN 978-1351857451. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- Longworth, T. Clifton, and Paul Tice (2003). A Survey of Sex & Celibracy in Religion. San Diego: The Book Tree, 61. Originally published as The Devil a Monk Would Be: A Survey of Sex & Celibacy in Religion (1945).

- Carlson, Patricia Ann (ed.) (1986). Literature and Lore of the Sea. Amsterdam: Editions Rodopi, 270.

- Austern, Linda Phyllis, and Inna Naroditskaya (eds.) (2006). Music of the Sirens. Bloomington, IN: University of Indiana Press, 72.

- Damm, perhaps Mythologie der Griechen und Römer (ed. Leveiow). Berlin, 1820.

- Lemprière 768. Brackets in the original.

- Robinson, Leonard (2007). William Etty: The Life and Art. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 9780786425310. OCLC 751047871.

Bibliography

- Clark, Willene B. (2006). A Medieval Book of Beasts: The Second-family Bestiary: Commentary, Art, Text and Translation. Boydell Press. ISBN 9780851156828.

- Druce, G. C. (1915), "Some Abnormal and Composite Human Forms in English Church Architecture", The Archaeological Journal, 72, The Bird-siren, 169–172; The Fish-siren, pp. 172–177, doi:10.1080/00665983.1915.10853279

- Fowler, R. L. (2013), Early Greek Mythography: Volume 2: Commentary, Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0198147411.

- George, Wilma B.; Yapp, William Brunsdon (1991). The Naming of the Beasts: Natural History in the Medieval Bestiary. Duckworth. pp. 99–100. ISBN 9780715622384.

- Hardwick, Paul (2011), English Medieval Misericords: The Margins of Meaning, Boydell Press, ISBN 9781843836599

- Harrison, Jane Ellen (1922) (3rd ed.) Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion. London: C.J. Clay and Sons.

- Holford-Strevens, Leofranc (2006), "1. Sirens in Antiquity and the Middle Ages", in Austern, Linda Phyllis; Naroditskaya, Inna (eds.), Music of the Siren, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 16–50, ISBN 9780253112071

- Homer, The Odyssey

- Lemprière, John (1827) (6th ed.). A Classical Dictionary;.... New York: Evert Duyckinck, Collins & Co., Collins & Hannay, G. & C. Carvill, and O. A. Roorbach.as mentioned in the scriptures

- Pakis, Valentine A. (2010). "Contextual Duplicity and Textual Variation: The Siren and Onocentaur in the Physiologus Tradition". Mediaevistik. 23: 115–185. doi:10.3726/83014_115. JSTOR 42587769.

- Sophocles, Fragments, Edited and translated by Hugh Lloyd-Jones, Loeb Classical Library No. 483. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-674-99532-1. Online version at Harvard University Press.

Further reading

- Siegfried de Rachewiltz, De Sirenibus: An Inquiry into Sirens from Homer to Shakespeare, 1987: chs: "Some notes on posthomeric sirens; Christian sirens; Boccaccio's siren and her legacy; The Sirens' mirror; The siren as emblem the emblem as siren; Shakespeare's siren tears; brief survey of siren scholarship; the siren in folklore; bibliography"

- "Siren's Lament", a story based around one writer's perception of sirens. Though most lore in the story does not match up with lore we associate with the wide onlook of sirens, it does contain useful information.